Abstract

The objective of this investigation was to determine the influence of distinct forms of acute weight loss on the expression of the quiescence marker, CD45RA, by T cells in several lymphoid compartments including the blood. Male and female weanling mice, CBA/J and C57BL/6J strains, were allocated to the following groups: ad libitum intake of a complete purified diet; restricted intake of the complete diet; and ad libitum intake of an isocaloric low-protein diet. The restricted intake protocol produced weight loss through energy deficiency (marasmic-type malnutrition), whereas the low-protein diet caused wasting through inadequate protein nitrogen and induced a condition mimicking incipient kwashiorkor. In one experiment, weanling mice of both strains were maintained for 14 days according to each of these dietary protocols and, in a supplementary study, C57BL/6J weanlings consumed either the complete diet or the low-protein diet ad libitum for 21 days. Zero-time control groups (19-days old and 23-days old in C57BL/6J and CBA/J strains, respectively) were included in the first experiment to control for ontogeny-related change. Expression of CD45RA was assessed by two-colour flow cytometry in CD4+ and CD8+ T cells from the spleen, mesenteric lymph nodes and blood. Within 14 days, energy-restricted mice exhibited a high percentage of CD4+ T cells expressing CD45RA in all three lymphoid compartments in both mouse strains (an average of 50% CD45RA+ versus 9% in well-nourished controls), and a similar outcome was apparent in the CD8+ subset (93% CD45RA+ versus 63%). Mice fed the low-protein diet required up to 21 days to exhibit the same imbalance within the CD4+ T-cell subset (33% CD45RA+ versus 4% in well-nourished controls). A shift toward a quiescent phenotype occurs throughout the peripheral T-cell system in acute wasting disease. Consequently, the quiescence-activation phenotype of blood T cells reflects the same index in secondary lymphoid organs in such pathologies. Naive-type quiescence among T cells is implicated as a component of depressed adaptive immunocompetence in the advanced stages of diverse forms of acute weight loss.

INTRODUCTION

Lymphoid involution is characteristic of wasting, prepubescent protein-energy malnutrition (PEM), and is generally considered to contribute to the depression in thymus-dependent immunocompetence that is a feature of this disease.1 At the same time, intervention studies using the hormone triiodothyronine have revealed that depression in thymus-dependent immunity can be prevented2–4 or even reversed5 despite unabated and profound lymphoid atrophy in which cellular losses exceed 90%. It is reasonable, therefore, to pursue other features of the immunobiology of PEM, whether deficiency of protein or of energy, that may prove more basic than lymphoid involution to depressed acquired immunity in wasting disease.

A widely accepted possibility is that imbalances among critical subsets of lymphocytes contribute to PEM-associated immunodepression.1 This idea has received support recently from the study of wasting protein and energy deficiencies in the weanling mouse. In these metabolically dissimilar pathologies, an overabundance of CD45RA+ T cells, both CD4+ and CD8+, is apparent within the involuted splenic lymphoid compartment.6 The CD45RA+CD4+ T cell is quiescent relative to its CD45RA− counterpart in terms of its proliferative and cytokine responses to stimulation through the T-cell receptor.7–10 Likewise, the CD45RA+CD8+ subset is weak in terms of cytokine production.11–13 Thus, T-cell subset imbalances that are consistent with depressed thymus-dependent immunocompetence are reported in the spleen of weanling mice subjected to PEM through either protein or energy deficit.

It is important to determine whether overabundance of CD45RA+ T cells in weanling PEM is a compartment-specific phenomenon confined to the spleen. The first objective of the present investigation was therefore to extend investigation of the expression of CD45RA in weanling PEM to T cells in the mesenteric lymph nodes and the blood. The mesenteric nodes constitute a large secondary lymphoid organ that, unlike the spleen, experiences constant high-level antigenic challenge.14 The blood is a small, labile and unique lymphoid compartment that cannot be presumed a priori to be representative of secondary lymphoid organs wherein responses to antigen are generated.15,16 At the same time, the blood is of particular interest as an accessible source of lymphocytes in the assessment of human subjects. A corollary objective was therefore to determine whether the blood reflects secondary lymphoid organs in relation to the expression of the marker, CD45RA, by T cells.

The experimental protocols used in this laboratory include a system in which a complete diet is fed in restricted daily quantities and a system in which ad libitum consumption is permitted of a low-protein diet.6,16 These protocols are designed for the study of PEM in its most debilitating forms and they mimic key immunological and other physiological features of the human conditions designated marasmus and (incipient) kwashiorkor, respectively.6,16–19 Thus, a key philosophy underlying the activities of this laboratory is to reproduce, in experimental animals, key features of human energy or protein deficiency pathologies rather than to duplicate the compositional details of diets consumed by humans exhibiting such pathologies. Although both experimental protocols induce an overabundance of CD45RA+ T cells in the spleen, the magnitude of the impact of the low-protein system on the CD4+ subset was equivocal.6 The second objective of the present investigation was therefore to determine whether this reflects a qualitative difference in immunological profile between metabolically distinct forms of experimental PEM, or whether it reflects simply the lesser degree of wasting (loss of carcass energy) that is reported in animals subjected to the low-protein protocol.16

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals and feeding protocols

Mice from in-house breeding colonies (Department of Human Biology and Nutritional Sciences, University of Guelph, Guelph, Canada) of C57BL/6J and CBA/J strains were used. C57BL/6J mice were weaned at 18 days of age, acclimated for 1 day to a complete purified diet, and subsequently allocated to experimental groups. CBA/J animals were weaned at 21 days of age and acclimated for 2 days before being assigned to experimental groups. These strain-dependent procedural differences, together with the subsequent experimental feeding regimens and the details of the animal facility, duplicated established protocols shown in this laboratory to produce depression in T-dependent immune responses of C57BL/6J4,6,20 and CBA/J2,3,21 weanlings. Mice were housed individually in plastic cages.

Diets

The complete purified diet has been described in detail21 and meets, or exceeds, current standards for the laboratory mouse.22 The low-protein diet was formulated by replacement of most of the egg white protein source with an equal weight of corn starch. By this means, a similar proximate analysis to that of the complete diet is maintained, with the exception of crude protein which measures 0·6% rather than 18%.3,4 Coprophagy was permitted in the present investigation, as in previous studies of T cells and immune competence in the same experimental systems.2–6,16,20,21

Experiment 1

Following acclimation, four groups of mice were studied within each strain: a control group was studied without further treatment, thus serving as a baseline or zero-time control (B); a control group (C) was given free access to the complete diet for 14 days; a malnourished group (R) was fed the complete diet in restricted daily quantities for 14 days; and a second malnourished group (LP) was given free access to the low-protein diet for 14 days. The quantity of diet provided to each animal subjected to the restricted intake protocol was determined by means of equations derived in this laboratory23 relating ad libitum food intake (g food/g body weight) to chronological age in weanling mice. The percentage of predicted ad libitum intake provided to each mouse (generally between 40% and 60%) was determined daily on the basis of the unique rate of weight loss of the animal. This strategy permitted a high degree of uniformity among animals in achieving a loss of ≫ 1·5% of initial body weight per day. Because of low cell numbers, pooling was necessary in the case of groups B and LP (two mice per pooled sample) and group R (three mice per pooled sample). Sample sizes of eight and seven, respectively, were achieved for C57BL/6J and CBA/J mice (e.g. eight and seven pooled samples of three group R mice, respectively), except that 10 animals were included in group C in the case of the C57BL/6J strain. Males and females were used in equal numbers in the case of the C57BL/6J strain and in a ratio of 4:3 (females:males) in the case of the CBA/J strain. As for individual group C mice, each pooled sample required for groups B, LP and R comprised one gender only, and constituted a single degree of freedom for the purpose of statistical analysis.

Experiment 2

The results of the first experiment gave rise to a supplementary investigation with a feeding period of 21 days. This was conducted with C57BL/6J weanlings and addressed the hypothesis that, if sufficient wasting was imposed by means of the low-protein diet, this would produce the same outcome as the restricted intake protocol regarding expression of CD45RA by peripheral T cells. Eight mice were given free access to the complete diet for the 21-day period, whereas eight pooled samples of three mice each were given free access to the low-protein diet for the same period of time. As in the first experiment, each group included males and females in equal numbers, and each pooled sample was made using mice of only one gender and constituted a single degree of freedom.

Procedures to obtain blood samples, spleen and lymph nodes

On day 14 (exp. 1) or on day 21 (exp. 2) of the experimental periods, blood samples were taken from the orbital plexus of mice anaesthetized with Metofane (Pitman-Moore, Mississauga, Canada). Zero-time control animals (exp. 1) were sampled on day 0. Blood was collected into heparinized microcentrifuge tubes. Mice were then killed by cervical dislocation, and the spleen and mesenteric nodes were removed aseptically into RPMI-1640 medium (Flow Laboratories Inc., Mississauga, Canada) containing 5% heat-inactivated fetal calf serum (Sigma Chemical Co., St Louis, MO) and 1 mmol/l HEPES (ICN Biomedicals Canada, St Laurent, Canada).

Identification of cellular subsets by flow cytometry

Single-cell suspensions of mononuclear cells for analysis by flow cytometry were prepared from the spleen, mesenteric lymph nodes and blood as described previously.16 Viability before staining was determined by eosin Y exclusion and always exceeded 95%. Cellular subsets were identified by means of an Epics XL-MCL flow cytometer equipped with version 1.5 (1993) software. Staining reagents included phycoerythrin-R (PE)-conjugated anti-CD4 (YTS 191.1), biotin-conjugated anti-CD8 (YTS 169.4), PE-conjugated streptavidin, unconjugated anti-CD45RA (RA3-2C2/1) and fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-conjugated IgG F(ab)2 fragment of affinity-purified goat anti-rat μ heavy chain. Details pertaining to these reagents and their use are provided elsewhere, as are details of the reagents and procedures applied for the purpose of negative control staining and Fc receptor blockade.6,16 Each analysis, including those of negative control samples, was based on at least 104 events after dead cells and residual erythrocytes were eliminated by gating on the basis of forward angle light scatter.

Carcass analyses

Carcasses were stored at −20° for as long as 20 weeks before analysis. Dry matter, lipid and crude protein contents were determined as described elsewhere.4,6,16,19

Statistical analysis

Data were subjected either to two-tailed Student’s t-test or, for multiple comparisons, to anova followed (if justified by the resulting statistical probability value, i.e. P < 0·05) by Tukey’s Studentized Range procedure. The error term of some data sets of exp. 1 failed to exhibit normal distribution both before and after application of several transformation procedures. In such instances, the Kruskal–Wallis test (chi-square approximation) was applied to Wilcoxon rank sums and, where warranted by the resulting statistical probability value (i.e. P < 0·05), this analysis was followed by chi-square comparisons of Wilcoxon two-sample rank sums for each combination of treatment pairs. The predetermined upper limit of probability for statistical significance throughout this investigation was P < 0·05.

RESULTS

Experiment 1: growth indices and mononuclear cell counts

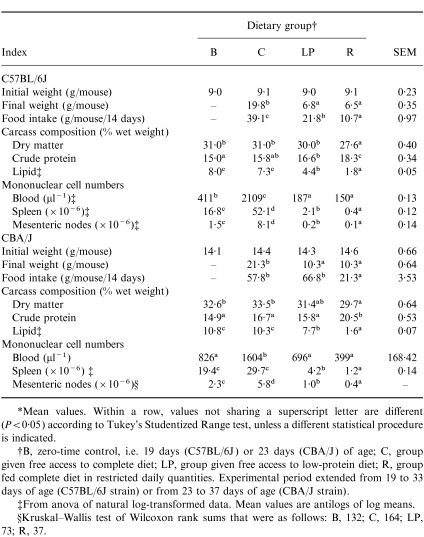

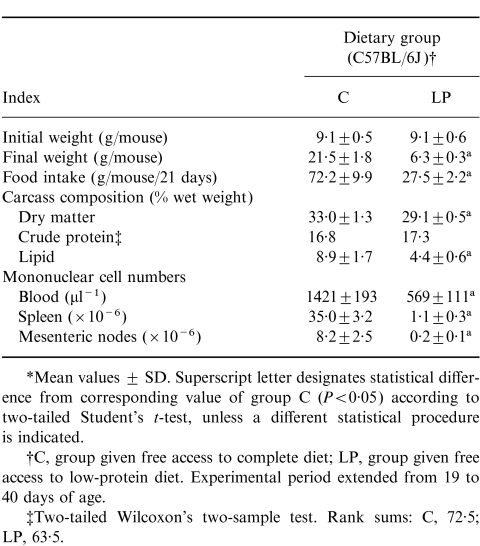

Both malnutrition protocols produced weight loss, altered carcass composition (in particular a low lipid content) and low mononuclear cell counts in each of the lymphoid compartments examined (Table 1). In addition, mice subjected to the restricted intake protocol exhibited a lower carcass lipid content than animals consuming the low-protein diet (Table 1). Cumulative food intakes were also low in the malnourished groups (Table 1), although the mice fed the low-protein diet exhibited food intakes that were either comparable (C57BL/6J) or high (CBA/J) relative to group C intakes when expressed on a body weight basis (results not shown). Collectively, the results in Table 1 illustrate that the wasting conditions produced in the present investigation were comparable to those reported previously in studies demonstrating depressed thymus-dependent immunocompetence in the same systems of experimental protein or energy deficiency.2–6,16,20

Table 1.

Experiment 1: initial and final body weights, food intakes, carcass compositions and numbers of viable mononuclear cells*

*Mean values. Within a row, values not sharing a superscript letter are different (P < 0·05) according to Tukey's Studentized Range test, unless a different statistical procedure is indicated.

†B, Zero-time control, i.e. 19 days (C57BL/6J) or 23 days (CBA/J) of age; C, group given free access to complete diet; LP, group given free access to low-protein diet; R, group fed complete diet in restricted daily quantities. Experimental period extended from 19 to 33 days of age (C57BL/6J strain) or from 23 to 37 days of age (CBA/J strain).

‡From anova of natural log-transformed data. Mean values are antilogs of log means.

§Krushal–Wallis test of Wilcoxon rank sums that were as follows: B, 132; C, 164; LP, 73; R, 37.

Experiment 1: expression of surface markers by T cells of the blood, spleen and mesenteric nodes

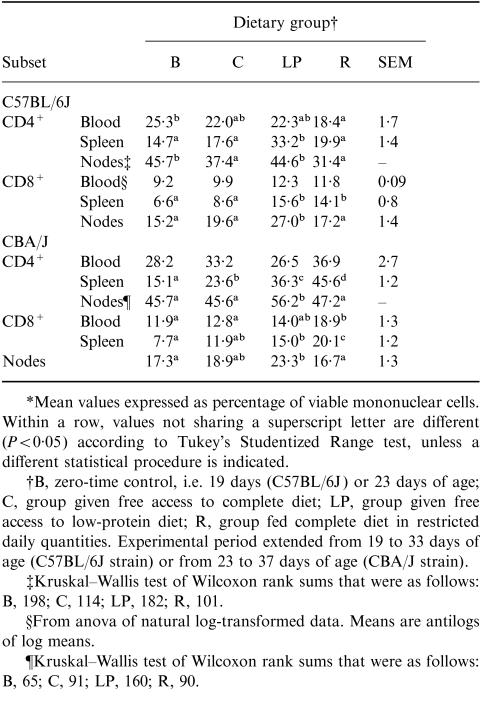

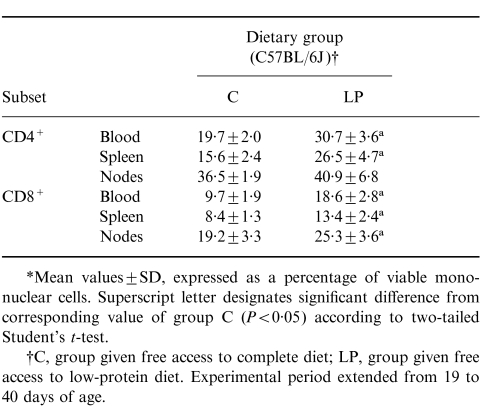

The percentages of mononuclear cells identified, within the blood, spleen and mesenteric lymph nodes, as either CD4+ or CD8+ T cells are shown in Table 2. The impact of the malnutrition protocols was variously to increase the proportion of mononuclear cells expressing these markers, or to produce no change. Likewise, no remarkable effect related to ontogeny was apparent by comparing the well-nourished and zero-time control groups. Thus, the results confirm previous reports pertaining to these indices in studies demonstrating immunodepression in the same experimental systems.6,16 It is important to emphasize that these results reflect a substantial involution on the part of both CD4+ and CD8+ T-cell populations in all three lymphoid sites. For example, the low-protein protocol induced loss of 72% and 48% of splenic CD4+ T cells (by comparison with the zero-time control group) in the C57BL/6J and CBA/J mice, respectively, whereas the corresponding losses induced by the restricted intake protocol were 96% and 81%.

Table 2.

Experiment 1: distribution of T cells between CD4+ and CD8+ subsets in blood, spleen and mesenteric nodes*

*Mean values expressed as percentage of viable mononuclear cells. Within a row, values not sharing a superscript letter are different (P < 0·05) according to Tukey's Studentized Range test, unless a different statistical procedure is indicated.

†B, Zero-time control, i.e. 19 days (C57BL/6J) or 23 days of age; C, group given free access to complete diet; LP, group given free access to low-protein diet; R, group fed complete diet in restricted daily quantities. Experimental period extended from 19 to 33 days of age (C57BL/6J strain) or from 23 to 37 days of age (CBA/J strain).

‡Kruskal–Wallis test of Wilcoxon rank sums that were as follows; B, 198; C, 114; LP, 182; R, 101.

§From anova of natural log-transformed data. Means are antilogs of log means.

¶Kruskal–Wallis test of Wilcoxon rank sums that as follows: B, 65; C, 91; LP, 160; R, 90.

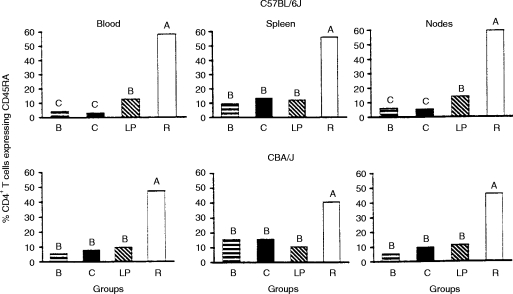

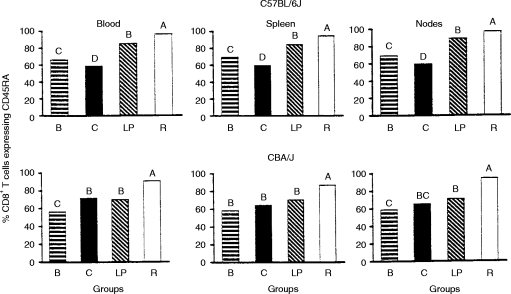

Representative flow cytometer histograms illustrating the expression of the surface marker CD45RA by CD4+ and CD8+ splenic T cells have been published previously for both C57BL/6J and CBA/J weanlings subjected to the same experimental protocols used in the present investigation.6 The percentages of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells exhibiting CD45RA+ phenotype are shown in Figs 1 and 2, respectively, for the blood, spleen and mesenteric lymph nodes of both strains of mice. In both strains, the group malnourished by restricted intake exhibited high proportions of CD45RA+ T cells relative to the two control groups. In contrast, the low-protein diet produced only small and inconsistent differences from the control groups in the proportion of T cells expressing CD45RA, except for an increase in the percentage of CD45RA+ cells within the CD8+ subset in mice of the C57BL/6J strain. Further, the impact of the two protocols of PEM on expression of CD45RA by T cells in the spleen and mesenteric lymph nodes was reflected with fidelity in the blood compartment.

Figure 1.

Percentage of CD4+ T cells exhibiting CD45RA+ surface phenotype in mononuclear cell suspensions from blood, spleen and mesenteric lymph nodes of C57BL/6J and CBA/J mice. Height of each bar represents the mean value and, in the case of blood cells from C57BL/6J mice, represents antilog of natural log-transformed data. Within each strain and lymphoid compartment, bars not sharing an upper case letter are different (P < 0·05) either according to Tukey’s Studentized Range test or according to the Kruskal–Wallis test followed by Wilcoxon two-sample rank sums tests. Pooled SEM = 0·13, 1·97, 1·47, 3·73 and 3·08, respectively, for blood, spleen and nodes of C57BL/6J mice and for blood and spleen of the CBA/J strain. In the case of the CBA/J lymph nodes, Kruskal–Wallis rank sums were 61·5, 90·0, 85·5 and 169·0, respectively, for groups B, C, LP and R. Sample sizes were eight and seven per group for C57BL/6J and CBA/J strains, respectively, except for group C of the C57BL/6J strain for which the sample size was 10. Males and females were used in approximately equal numbers. Mononuclear cells from two mice of groups B and LP, and from three mice of group R, were pooled (within genders) to produce each sample taken from these groups. B, zero-time control group, i.e. 19 days (C57BL/6J) and 23 days (CBA/J) of age; C, control group consuming the complete diet ad libitum; LP, group consuming the low-protein diet ad libitum; R, group consuming the complete diet in restricted daily quantities. The experimental period extended from 1 9 to 33 days of age (C57BL/6J strain) or from 23 to 37 days of age (CBA/J strain).

Figure 2.

Percentage of CD8+ T cells exhibiting CD45RA+ surface phenotype in mononuclear cell suspensions from blood, spleen and mesenteric lymph nodes of C57BL/6J and CBA/J mice. Procedural details and group designations are as for Figure 1. Height of each bar represents the mean value. Within each strain and lymphoid compartment, bars not sharing an upper case letter are different (P < 0·05) either according to Tukey’s Studentized Range test or according to the Kruskal–Wallis test followed by Wilcoxon two-sample tests. Pooled SEM =1·70, 1·59 and 2·27, respectively, for blood and spleen of C57BL/6J mice and for blood of the CBA/J strain. Kruskal–Wallis rank sums (listed, in each case for groups B, C, LP and R, respectively) were 109·0, 62·0, 180·0 and 244·0 for C57BL/6J lymph nodes, 51·5, 88·5, 103·0 and 163·0 for CBA/J spleen, and 46·0, 83·0, 102 ·0 and 175·0 for CBA/J lymph nodes.

Experiment 2: growth indices and mononuclear cell counts

Table 3 records the weight loss, low cumulative food intake, altered carcass composition and low mononuclear cell numbers found in C57BL/6J weanlings as a result of consumption of the low-protein diet for 21 days. Formal statistical comparison with the results of exp. 1 is inappropriate, but weight loss averaged 31% of initial body weight (compared with 24% in exp. 1) and the decrement in carcass fat content achieved sufficient magnitude to affect the percentage of dry matter.

Table 3.

Experiment 2: initial and final body weights, food intakes, carcass compositions and numbers of viable mononuclear cells*

*Mean values ± SD. Superscript letter designates statistical difference from corresponding value of group C (P < 0·05) according to two-tailed Students's t-test, unless a different statistical procedure is indicated.

†C, group given free access to complete diet; LP, group given free access to low-protein diet. Expeimental period extended from 19 to 40 days of age.

‡Two-tailed Wilcoxon's two-sample test. Rank sums: C, 72·5; LP, 63·5.

Experiment 2: expression of surface markers by T cells of the blood, spleen and mesenteric nodes

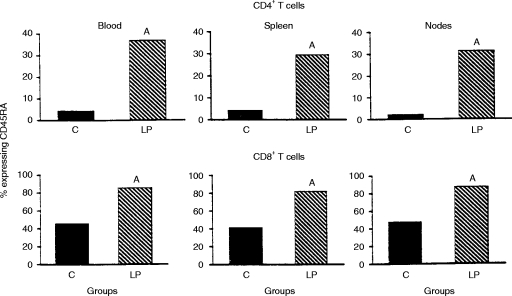

The percentages of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells within the mononuclear cell populations recovered from the blood, spleen and mesenteric lymph nodes of weanling C57BL/6J mice fed the complete diet or the low-protein diet for 21 days are shown in Table 4. For the most part, the low-protein group exhibited higher percentages of cells within both T-cell subsets than the well-nourished controls. In contrast to the outcome of the first experiment (Figs 1 and 2), the results in Fig. 3 demonstrate elevation in the percentage of T cells, both CD4+ and CD8+, expressing CD45RA in the three lymphoid compartments examined in the mice fed the low-protein diet. The influence of the low-protein diet on the percentage of T cells expressing CD45RA was closely similar in the blood and secondary lymphoid organs.

Table 4.

Experiment 2: distribution of T cells between CD4+ and CD8+ subsets in blood, spleen and mesenteric nodes*

*Mean values±SD, expressed as a percentage of viable mono-nuclear cells. Superscript letter designates significant difference from corresponding value of group C (P < 0·05) according to two-tailed Student's t-test.

†C, group given free access to complete diet; LP, group given free access to low-protein diet. Experimental period extended from 19 to 40 days of age.

Figure 3.

Percentage of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells exhibiting CD45RA+ surface phenotype in mononuclear cell suspensions from blood, spleen and mesenteric lymph nodes of C57BL/6J mice. Height of each bar represents the mean value. In the case of nodal CD4+ T cells, the bars represent squares of square root-transformed means, and in the case of blood CD8+ T cells the bars represent antilogs of natural log-transformed means. Within each subset of T cells and lymphoid compartment, the upper case letter ‘A’ identifies statistical difference from group C according to two-tailed Student’s t-test (P < 0·05). SD (group C and group LP) =2·99 and 12·75, 3·41 and 9·82, and 0·63 and 1·05 for CD4+ T cells of blood, spleen and lymph nodes, respectively. Likewise, SD (group C and group LP) =0·19 and 0·10, 9·67 and 7·44, and 10·98 and 7·63 for CD8+ T cells of blood, spleen and lymph nodes, respectively. Sample sizes were eight per group, and males and females were used in equal numbers within each group. Three mice of the same gender were pooled to produce each sample tested from the low-protein group. C, group consuming the complete diet ad libitum; LP, group consuming the low-protein diet ad libitum. The experimental period extended from 19 to 40 days of age.

DISCUSSION

In mice and humans, peripheral T cells bearing the CD45RA+ surface phenotype are quiescent relative to CD45RA− T cells in the production of a variety of key cytokines.7–9,12,13 The importance of CD4+ T cells in cytokine production has been recognized for many years, whereas the role of peripheral CD8+ T cells in this capacity has come to light only recently.13 The present investigation identifies a shift towards quiescence within both major subpopulations of T cells as a characteristic of the advanced stages of both protein and energy deficiencies. Results previously confined to the spleen6 therefore apply more generally among lymphoid compartments in PEM. Moreover, inasmuch as the experimental systems used in this investigation produce immunodepression,2–6,20 the results point to naive-type T-cell quiescence as a component of the sequence of events leading to immune depression in metabolically dissimilar forms of PEM. Inclusion of a zero-time control group in the design of this investigation permits the conclusion that experimental PEM exerts a more fundamental influence on T-cell biology than simply an influence on immunological ontogeny. Moreover, use of the genetically disparate C57BL/6J and CBA/J strains,24 subjected to metabolically dissimilar forms of PEM, strengthens confidence in the basic import of the present results, although study of outbred animals would be a desirable extension of this investigation. The high degree of phylogenetic conservation of CD45,25 together with the close similarity between the mouse and the human regarding the significance of the CD45RA+ phenotype as an index of T-cell quiescence,9 render the results relevant to the pathophysiology of protein and energy deficiencies in humans.

It is instructive to consider the metabolic dissimilarity between the two malnutrition protocols of this investigation. As in previous investigations,16 the wasting disease of the low-protein groups resulted from dietary nitrogen deficiency in the presence of sufficient intake of energy and micronutrients. In contrast, the restricted intake protocol produces weight loss as a result of inadequate energy intake while protein and micronutrients are in sufficient supply.17 Both dietary protocols produce depression in the adaptive immunocompetence of the weanling mouse within less than 14 days.3,4,20 However, whereas the energy deficiency system produced a convincing influence on the quiescence-activation phenotype among T cells within this time-frame, the protein deficiency model required additional time. In this connection, the carcass lipid analyses confirmed previous results16 showing that the caloric deficiency model produces a more rapid loss of carcass energy than the low-protein protocol. Thus, a simple interpretation is that elevation in the CD45RA+/CD45RA− ratio among T cells develops when energy deficit is sufficiently advanced in acute wasting disease, and may reflect ongoing immunodepression without being involved in its initiation.

Characteristics of CD45RA+ T cells other than their quiescence are relevant to PEM-associated immunodepression. For example, the CD45RA+ subset of CD4+ T cells is reported to exhibit particular sensitivity to CD8+-dependent suppression.26 In addition, a numerical imbalance between CD45RA+ and CD45RA− cells will disturb the complementarity in cytokine production that regulates the proliferative capacity of T cells, at least within the CD4+ subpopulation.8 Through a variety of mechanisms, therefore, an elevated CD45RA+/CD45RA− ratio among T cells may contribute to immunodepression in advanced wasting disease both in a protein deficiency model that mimics incipient kwashiorkor17,18 and in an energy deficiency system that closely resembles human marasmus.6,16–19

Memory-phenotype T cells, although extremely heterogeneous in life span, collectively exhibit rapid turnover relative to naive-phenotype T cells.27,28 Thus, an elevated CD45RA+/CD45RA− ratio among T cells in PEM could reflect nothing more than disproportionately high losses of short-lived (CD45RA−) cells, i.e. a reduced capacity to support cellular turnover in wasting disease. In this context, however, CD45RBbright and CD45RBdim phenotypes identify long-lived and short-lived CD4+ T cells, respectively, in the mouse,28 but advanced weanling PEM fails to influence the relative numbers of cells expressing these phenotypes.6 Thus, even advanced weight loss pathologies do not appear to produce T-cell subset imbalances simply on the trivial basis of differing T-cell life spans.

Numerous phenomena may conspire to yield an overabundance of naive-phenotype T cells in PEM. For example, activated/memory T cells revert to a naive phenotype if antigen presentation support is insufficient,10 and the capacity of splenic mononuclear cells to present antigen to activated/memory T cells is low in mice subjected to energy deficiency.29 As a second example, activated T cells appear to require stimulation through the gamma chain of the interleukin(IL)-2 receptor in order to escape apoptosis.30 Several cytokines interact with this component of the IL-2 receptor,30 and the capacity to produce at least two such cytokines, viz. IL-2 and IL-4, is reduced in weanling mice subjected to deficiency of either energy or protein.1,29 Thus, diverse phenomena may contribute to a shift towards quiescence within the involuted T-cell system in weanling protein and energy deficiencies. In this investigation, the CD8+ subpopulation of protein-deficient C57BL/6J mice was affected at an earlier stage of the wasting process than the CD4+ subset. This preliminary observation may be worthwhile to pursue in seeking mechanisms underlying the quiescence shift among T cells in acute weight loss.

The blood is the main source of lymphocytes for the clinical and experimental assessment of human subjects. Nevertheless, indices pertaining to blood T cells cannot be presumed ipso facto to reflect the T cells within secondary lymphoid organs wherein lymphocytes recognize and respond to antigen.15 The results of the present investigation, however, permit the conclusion that the blood can provide information as to the impact of acute wasting pathologies on the expression of CD45RA by T cells within the secondary lymphoid organs. More broadly, examination of the blood provides insight regarding the impact of acute weight loss on this quiescence-related characteristic of the recirculating surveillance pool of T cells. Moreover, it is reasonable to expect that the same principle will apply to T-cell subsets at other stages of the quiescence-activation spectrum as defined by isoforms of CD45 other than CD45RA. It has been reported recently that PEM produces a shift towards expression of CD45RA in blood T cells of elderly humans.31 The present results confirm this finding across species and at the other extreme of the life span spectrum, and illustrate the probable significance of this observation on human blood to the systemic immunopathology of PEM in humans.

The results of this investigation suggest a systemic impact on the expression of CD45 by T cells in the advanced stages of pathologies characterized by acute weight loss and depressed inflammatory response. Thus, naive-type quiescence among T cells is implicated as a component of depressed adaptive immune competence in pathological weight loss. This is an important new clue regarding the mechanism of immunodepression in acute wasting diseases.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants awarded to B. Woodward by the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada and by the Nutricia Research Foundation (Holland).

Glossary

Abbreviations

- group B

zero-time control mice

- group C

mice consuming complete diet ad libitum

- group LP

mice consuming low-protein diet ad libitum

- group R

mice fed complete diet in restricted daily quantities

- PEM

protein-energy malnutrition.

References

- 1.Woodward B. Protein, calories and immune defenses. Nutr Rev. 1998;56(Suppl. 1):S84. doi: 10.1111/j.1753-4887.1998.tb01649.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Filteau SM, Perry KJ, Woodward B. Triiodothyronine improves the primary antibody response to sheep red blood cells in severely undernourished weanling mice. Proc Soc Exp Biol Med. 1987;185:427. doi: 10.3181/00379727-185-42565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Perry KJ, Filteau SM, Woodward B. Dissociation of immune capacity from nutritional status by triiodothyronine supplements in severe protein deficiency. FASEB J. 1988;2:2609. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.2.10.3290026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Woods JW, Woodward BD. Enhancement of primary systemic acquired immunity by exogenous triiodothyronine in wasted, protein-energy malnourished weanling mice. J Nutr. 1991;121:1425. doi: 10.1093/jn/121.9.1425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Woods JW, Woodward B. Immunorestorative effect of triiodothyronine supplementation on the primary antibody response to sheep red blood cells following the development of immunodepression in protein-energy malnourished weanling mice. J Nutr Immunol. 1994;3:3. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Woodward BD, Bezanson KD, Hillyer LM, Lee W-H. The CD45RA+ (quiescent) cellular phenotype is overabundant relative to the CD45RA− phenotype within the involuted splenic T cell population of weanling mice subjected to wasting protein-energy malnutrition. J Nutr. 1995;125:2471. doi: 10.1093/jn/125.10.2471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Horgan KJ, van Seventer GA, Shimizu Y, Shaw S. Hyporesponsiveness of ‘naive’ (CD45RA+) human T cells to multiple receptor-mediated stimuli but augmentation of responses by co-stimuli. Eur J Immunol. 1990;20:1111. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830200525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lightstone E, Marvel J. CD45RA+ T cells: not simple virgins. Clin Sci. 1993;85:515. doi: 10.1042/cs0850515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lightstone E, Marvel J, Mitchison A. Hyper-reactivity of mouse CD45RA− T cells. Eur J Immunol. 1993;23:2383. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830230952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bell EB, Sparshott SM, Bunce C. CD4+ T cell memory, CD45R subsets and the persistence of antigen – a unifying concept. Immunol Today. 1998;19:60. doi: 10.1016/s0167-5699(97)01211-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hirohata S. T8 cell regulation of human B cell responsiveness: regulatory influences of CD45RA+ and CD45RA− T8 cell subsets. Cell Immunol. 1991;133:15. doi: 10.1016/0008-8749(91)90176-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Adamthwaite D, Cooley MA. CD8+ T-cell subsets defined by expression of CD45 isoforms differ in their capacity to produce IL-2, IFN-γ and TNF-β. Immunology. 1994;81:253. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Conlon K, Osborne J, Morimoto C, Ortaldo JR, Young HA. Comparison of lymphokine secretion and mRNA expression in CD45RA+ and CD45RO+ subsets of human peripheral blood CD4+ and CD8+ lymphocytes. Eur J Immunol. 1995;25:644. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830250303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kroese FGM, Ammerlaan WAM, Deenen GJ. Location and function of B-cell lineages. Ann NY Acad Sci. 1992;651:44. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1992.tb24592.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Westermann J, Pabst R. Distribution of lymphocytes and natural killer cells in the human body. Clin Invest. 1992;70:539. doi: 10.1007/BF00184787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lee W-H, Woodward BD. The CD4/CD8 ratio in the blood does not reflect the response of this index in secondary lymphoid organs of weanling mice in models of protein-energy malnutrition known to depress thymus-dependent immunity. J Nutr. 1996;126:849. doi: 10.1093/jn/126.4.849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mittal A, Woodward B. Ultrastructural and morphometric analysis of thymic epithelial secretory vacuoles in severely protein-energy malnourished weanling mice. Nutr Res. 1986;6:663. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Filteau SM, Woodward B. Influence of severe protein deficiency and of severe food intake restriction on serum levels of thyroid hormones in the weanling mouse. Nutr Res. 1987;7:101. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ha C-L, Woodward B. Reduction in the quantity of the polymeric immunoglobulin receptor is sufficient to account for the low concentration of intestinal secretory immunoglobulin A in a weanling mouse model of wasting protein-energy malnutrition. J Nutr. 1997;127:427. doi: 10.1093/jn/127.3.427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Woodward B, Miller RG. Depression of thymus-dependent immunity in wasting protein-energy malnutrition does not depend on an altered ratio of helper (CD4+) to suppressor (CD8+) T cells or on a disproportionately large atrophy of the T-cell relative to the B-cell pool. Am J Clin Nutr. 1991;53:1329. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/53.5.1329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Filteau SM, Woodward B. Relationship between serum zinc level and immunocompetence in protein-deficient and well-nourished weanling mice. Nutr Res. 1984;4:853. [Google Scholar]

- 22.National Research Council. Nutrient Requirements of Laboratory Animals. 4. Vol. 82. National Academy Press: Washington, DC; 1995. Nutrient requirements of the mouse. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mittal A, Woodward B. Thymic epithelial cells of severely undernourished mice: accumulation of cholesteryl esters and absence of cytoplasmic vacuoles. Proc Soc Exp Biol Med. 1985;178:385. doi: 10.3181/00379727-178-42021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Staats J. The laboratory mouse. In: Green EL, editor. Biology of the Laboratory Mouse. Vol. 1. McGraw-Hill: New York, NY; 1966. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Neel BG. Role of phosphatases in lymphocyte activation. Curr Opin Immunol. 1997;9:405. doi: 10.1016/s0952-7915(97)80088-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Freedman MS, Blain M, Antel JP. Differential responses of CD4+CD45RA+ and CD4+CD29+ subsets to activated CD8+ cells: enhanced stimulation of CD4+CD45RA+ subset by cells from patients with multiple sclerosis. Cell Immunol. 1991;133:306. doi: 10.1016/0008-8749(91)90106-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sprent J. Immunological memory. Curr Opin Immunol. 1997;9:371. doi: 10.1016/s0952-7915(97)80084-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tough DF, Sprent J. Turnover of naive-and memory-phenotype T cells. J Exp Med. 1994;179:1127. doi: 10.1084/jem.179.4.1127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shi HN, Scott ME, Stevenson MM, Koski KG. Energy restriction and zinc deficiency impair the functions of murine T cells and antigen-presenting cells during gastrointestinal nematode infection. J Nutr. 1998;128:20. doi: 10.1093/jn/128.1.20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Akbar AN, Salmon M. Cellular environments and apoptosis: tissue microenvironments control activated T-cell death. Immunol Today. 1997;18:72. doi: 10.1016/s0167-5699(97)01003-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lesourd BM. Nutrition and immunity in the elderly: modification of immune responses with nutritional treatments. Am J Clin Nutr. 1997;66:478S. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/66.2.478S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]