Abstract

Studies were carried out to characterize the cellular and humoral immune responses evoked by intramuscular DNA vaccination with the major outer membrane protein (MOMP) gene of Chlamydia trachomatis mouse pneumonitis strain. The data demonstrate that DNA vaccinated mice develop antigen-specific delayed-type hypersensitivity, lymphocyte proliferation and interferon-γ (IFN-γ) production. Serum antibody responses (mainly immunoglobulin G2a; IgG2a) were evoked in two-thirds of the mice. We conclude that intramuscular DNA immunization with the MOMP gene evokes cellular and humoral immune responses suggestive of a T helper 1 (Th1) bias.

INTRODUCTION

Even with the availability of antibiotics, Chlamydia trachomatis remains an important cause of human infectious disease for which a safe and effective vaccine has been a long-sought goal.1 Despite decades of effort, this goal has not yet been achieved with the impediments to developing a chlamydial vaccine seemingly substantial.2 However, vaccine development for prevention of C. trachomatis infection remains a feasible goal for researchers resolute to the challenge.3 Natural infection appears to result in partial resistance to same strain reinfection.2,4,5 Early human vaccination trials with whole inactivated bacteria demonstrated that immunity to recurrent chlamydial disease could be induced although vaccine efficacy was incomplete and short lived.6,7 Vaccine trials in primates suggested that a subunit design would be necessary since breakthrough infections in previously vaccinated animals were associated with worse inflammatory disease.6,8 Human vaccination trials also suggested this potential adverse effect of immunization.9 These observations were interpreted to suggest that the chlamydial cell contains both immunoprotective and immunopathological antigens and that a subunit design for a chlamydia vaccine needs to contain only the protective antigen.10

As the dominant serovariant surface protein of C. trachomatis, the major outer membrane protein (MOMP) appears to be the principal target for protective immune responses and considerable effort has been devoted to developing a vaccine based on the MOMP. Native MOMP,11–16 recombinant MOMP,17 synthetic MOMP peptides18 and live recombinant poliovirus19,20 or salmonella21 vectors containing MOMP sequences from either C. trachomatis or C. psittaci strains have been evaluated in primate, mice, sheep and guinea-pig models of infection. While some of the protein-based vaccines, especially those approaches which attempted to preserve the conformational structure of the MOMP, generated limited protective immunity in experimental animals, most trials were not successful.

Several potential reasons as to why MOMP-based vaccines failed to induce protective immunity can be considered and include failure of the vaccine to induce the protective effector mechanisms at the mucosal sites of challenge infection. Current knowledge suggests that immunity to C. trachomatis is in large part caused by CD4 T lymphocytes that are polarized to express T helper 1 (Th1)-type cytokines such as interferon-γ (IFN-γ).22 In fact, immunoepidemiological studies suggest that predominant expression of Th2 cytokines such as interleukin-4 (IL-4) and IL-10 is associated with persistent infection and immunopathology.23,24 Thus, delivery of a MOMP immunogen in a manner that elicits Th1-type immune responses may be essential for a protective C. trachomatis vaccine and may not have occured with the various vaccine forms of MOMP exploited to date.

We recently reported that delivery of MOMP as a DNA construct using a eucaryotic expression plasmid generated significant although not complete protective immunity in a lung challenge model with the mouse pneumonitis (MoPn) strain of C. trachomatis.25 We report here that the DNA vaccine induces polarized Th1 immune responses, a desirable property for a chlamydial vaccine.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animal and organism

Female BALB/c mice (4–5-week-old) were purchased from Charles River Canada (Saint Constant, PQ, Canada). All animals were maintained and used in strict accordance with the guideline issued by the Canadian Council on Animal Care.

The C. trachomatis mouse pneumonitis (MoPn) isolate was grown in HeLa cells and elementary bodies (EBs) were purified by step gradient density centrifugation as previously described.26

DNA vaccine and immunization

The MOMP expression vector (pMOMP) was made as described.25 In brief, the MOMP gene was amplified from MoPn genomic DNA by the polymerase chain reaction (PCR) with a 5′ primer which included a Bam H1 site and an initiation codon and the N-terminal sequence of the mature MOMP and a 3′ primer which included the C-terminal sequence of the MoPn MOMP, two stop codons and an Xho l site. The PCR product was cloned into Bam H1- and Xho I-restricted pcDNA3 with transcription under the control of the human cytomegalovirus major immediate early gene promoter enhancer region. The MOMP gene-encoding plasmid was transferred by electroporation into Escherichia coli DH5α which was grown in Luria–Bertani (LB) broth containing ampicillin. The plasmid was extracted by a DNA purification system (Wizardä Plus Maxiprep, Promega, Madison, WI) and the sequence of the recombinant MOMP DNA sequence was verified by PCR direct sequencing. Purified plasmid DNA was dissolved in saline at a concentration of 1 mg/ml.

Mice were intramuscularly immunized with plasmid DNA on four occasions at 0, 3, 6 and 8 weeks. For each injection, a total of 200 μl of plasmid DNA (200 μg) was injected into both quadriceps muscles (100 μg DNA per injection site) using a 27-guage needle. Negative control mice were injected intramuscularly with saline or with the blank plasmid vector (pcDNA3) lacking the inserted chlamydial gene. As a positive control group, mice were immunized intramuscularly with 5×106 inclusion forming units (IFUs) of MoPn heat-treated (100° for 10 min) EBs in sucrose–phosphate–glutamate (SPG) buffer25 according to the above schedule.

Challenge infection and quantification of MoPn in the lung

Mice were challenged intranasally with MoPn on day 66 as described.25 Briefly, following ether anaesthesia, 40 μl of SPG containing 5×103 IFU of MoPn was delivered onto the nostrils of mice with a micropipettor. The droplet was subsequently inhaled by the mice. Body weight was measured daily for 10 days following the challenge infection. The mice were killed and their lungs were aseptically isolated and homogenised with a cell grinder in SPG buffer on the 10th postinfection day. The tissue suspensions were centrifuged at 500 g for 10 min at 4° to remove coarse tissue and debris. The supernatants were frozen at −70°. For quantification of MoPn growth in the lung, HeLa-229 cells were grown to confluence in 96-well flat-bottom microtitre plates and were treated with 100 μl of Hank’s balanced salt solution (HBSS) containing 30 μg/ml of diethylaminoethyl (DEAE)–dextran for 15 min. The monolayers were then inoculated in triplicate with 50 μl of the serially diluted supernatants of lung tissues. After 2 hr incubation at 37° on a rocker platform, the plates were washed and 200 μl per well of Eagle’s minimal essential medium (MEM) containing 10% fetal calf serum (FCS), 1·5 μg/ml cycloheximide and 12 μg/ml of gentamicin. The plates were incubated for 48 hr at 37° in 5% CO2. The cell monolayers were fixed with absolute methanol. To identify inclusion-containing cells, the plates were incubated with a Chlamydia genus-specific murine monoclonal antibody and stained with goat antimouse immunoglobulin G (IgG) conjugate to horseradish peroxidase (HRP). The stained inclusions were developed by 4-chloro-1-naphthol (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) and H2O2. The number of inclusions was counted under a microscope and chlamydial infectivity in each lung was calculated based on the dilution titer of the original inoculum.

Measurement of cellular immunity

MoPn-specific delayed-type hypersensitivity (DTH)

DTH was evaluated two weeks after the fourth immunization as previously described.27 In brief, 25 μl of ultraviolet (UV)-killed MoPn EBs (2×105 IFU) in SPG buffer was injected into the right hind footpad of the mice and the same volume of SPG buffer was injected into the left hind footpad as a control. Footpad swelling was measured at 48 hr and 72 hr following the injection using a dial-gauge calliper (Walter Stern 601, Fisher Scientific, Ottawa, ON, Canada). The difference between the thickness of two foot pads was used as a measure of the DTH response.

Lymphocyte proliferation

Mice were killed 2 weeks after the fourth immunization. The spleens were removed and single-cell suspensions were prepared. 200 μl of the cell suspension (5×105 cells/well) in RPMI-1640 medium containing 10% heat-inactivated FCS, 1% l-glutamine and 5×10−5 m 2-mercaptoethanol (2ME) (Kodak, Rochester, NY) were incubated with 1×105 IFU/ml of MoPn in 96-well flat bottom plates in triplicate at 37° in 5% CO2 for 96 hr. Negative control wells contained spleen cells without antigen and positive control wells contained spleen cells with 0·25 μg/ml of concanavalin A. 0·25 μCi/well of tritiated (3H) thymidine (ICN, Irvine, CA) was added after 3 days of culture and 16 hr before harvest. The cells were harvested with a PHD cell harvester (Cambridge Technology Inc., Watertown, MA) after four days of culture and the 3H-thymidine uptake was counted in 2 ml of scintillation solution (Universal, ICN, Costa Mesa) using a Beckman LS5000 B-counter (Beckman Instruments, Palo Alto, CA).

Cytokine enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA)

IFN-γ and IL-10 production were analysed with MoPn EB antigen restimulation in vitro as previously described.27 Briefly, the single-cell suspension of spleen cells were cultured at 5×106/ml (2 ml/well) with UV-killed MoPn (2×105 IFU/ml) or alone in 24-well plates at 37° in RPMI-1640 medium containing 10% FCS, 1% l-glutamine and 5×10−5 m 2ME. Culture supernatants were harvested at 24, 48, 72 and 96 hr.

Murine IFN-γ and IL-10 in culture supernatants were detected by a two monoclonal antibody (mAb) sandwich ELISA purchased from PharMingen (San Diego, CA). For IFN-γ assay, mAb R4-GA2 was used for capture and XMG1.2 was used for detection. For IL-10 assay, mAb JES5-2A5 was used for capture and SXC-1 was used for detection. Ninety-six-well ELISA plates (Corning 25805, Corning Science Products, NY) were coated with 50 μl of anticytokine antibody diluted in coating buffer (0·1 m NaHCO3, pH 8·2) and incubated overnight at 4°. The wells were blocked with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) containing 1% bovine serum albumin (BSA) at room temperature for 2 hr. Serial twofold dilutions of culture supernatants and cytokine standards were added to duplicate wells. After incubation at room temperature for 4 hr, the plates were washed four times with PBS containing 0·05% Tween 20(PBS-T). Biotinylated anticytokine mAb diluted in PBS with 1% BSA was added and incubated overnight at 4°. The plates were subsequently washed with PBS-T four times and incubated with streptavidin–alkaline phosphatase (Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories, Inc. West Grove, PA) at 1:6000 dilution in PBS at 37° for 45 min. The plates were extensively washed with PBS-T and p-nitrophenyl phosphate (phosphatase substrate tablets, Sigma, St. Louis, MO), diluted in substrate buffer (0.5 m MgCl2, 10% diethanolamine, pH 9·8) was subsequently added. The plates were read with a microplate reader (Bio-Rad 3550, Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA) at 405 nm.

Cytokine ELISPOT

A cytokine ELISPOT assay was used for the quantification of murine IFN-γ- and IL-10-secreting cells in the murine spleen.28 For all assays 96-well nitrocellulose-based microtitre plates (Milititer Multisreen HA plates, Millipore Corp, Molshem, France) were coated overnight at 4° with 100 μl of the appropriate anticytokine mAb diluted in PBS. After removing the coating solution from the plates, wells were blocked for at least 1 hr with RPMI-1640 containing 10% FCS at 37° in 5% CO2. After rinsing the plates with PBS-T once, the testing cells were added into the wells.

For activation of antigen-specific IFN-γ and IL-10 secreting cells in immunized mice, single cells were adjusted to 5×106 cells/ml and cultured with 2×105 IFU/ml of UV-killed EB of MoPn in 24 well plates for 72 hr. After washing with RPMI-1640, cells were added onto the 96-well nitrocellulose-based microtitre plates which had been previously coated with anticytokine antibodies. The cells were added to individual wells (2×105 or 1×105/100 μl/well) and incubated for 24 hr at 37° in a CO2 incubator. Wells were rinsed extensively with PBS-T containing 1% BSA. Following rinsing with PBS-T three times (removing the supporting manifold and washing the back of the plate thoroughly with PBS-T), alkaline phosphatase conjugated streptavidin in PBS containing 1% BSA at 1:2000 was added and incubated at 37° in 5% CO2 for 45 min. After rinsing thoroughly, 100 μl/well of the colorimetric substrate [5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl phosphate (BICP)/nitro blue tetrazolium (NBT) at 0·16 mg/ml BICP and 1 mg/ml NBT in substrate buffer (0·1 m NaCl, 0·1 m Tris, pH 9·5, 0·05 m MgCl2)] was added and incubated at room temperature until spots were visualized. The reaction was stopped by the addition of water.

Measurement of humoral immunity

ELISA

Chlamydia-specific murine IgG2a, IgG1 and IgA antibody levels in serum were detected using an alkaline phosphatase-based ELISA.27 Briefly, mice were bled from the tail 2 weeks following the third immunization. ELISA plates (Corning 25805, Corning Science Products, NY) were coated with 50 μl of 1×105 IFU of MoPn EBs in bicarbonate buffer (0·05 m, pH 9·6) overnight at 4°. After blocking with 2% BSA dissolved in PBS for 2 hr at room temperature, the plates were incubated with serially diluted mouse sera for 4 hr at room temperature. After washing six times with PBS-T, biotinylated goat antimouse IgG2a, goat antimouse IgG1 (Southern Biotechnology Associates Inc., Birmingham, AL) or goat antimouse IgA (Caltag Laboratories, San Francisco, CA) were added to the wells and incubated overnight at 4°. Alkaline phosphatase conjugated streptavidin was then added for 45 min at 37°. After extensive washing, p-nitrophenyl phosphate was added to the plates as described previously in cytokine ELISA. The plates were read with a microplate reader at 405 nm.

Immunoblot

Western blot analysis was performed to identify anti-MOMP antibody in the sera of immunized mice.25,29 Briefly, purified MoPn EBs were lysed by boiling in sample buffer containing 2% sodium dodecyl sulphate (SDS) and 200 mm 2ME and subsequently electrophoresed in a 10% SDS–polyacrylamide gel (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA). The proteins were transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane. The membrane was blocked with 3% BSA–PBS overnight. After extensive washing, the membrane was cut into strips corresponding to each lane. The strips were mounted in a multiscreen incubation tray (Bio-Rad, Richmond, CA) and 1:100 dilution of sera from different mice were added to separate sections of the tray. After a 2-hr incubation at room temperature and subsequent washing with PBS containing 1% Tween 20 (pH 7·4), the membrane strips were incubated with HRP conjugated goat antimouse IgG at a dilution of 1:1000 in PBS-T containing 2% BSA for 1 hr. The bands were developed using the ECL system (Amersham International. Little Chalfont, UK) according to the manufacturer’s instruction.

Statistics

Data were analysed using Student’s t-test.

RESULTS

Protective efficacy induced by MOMP DNA immunization

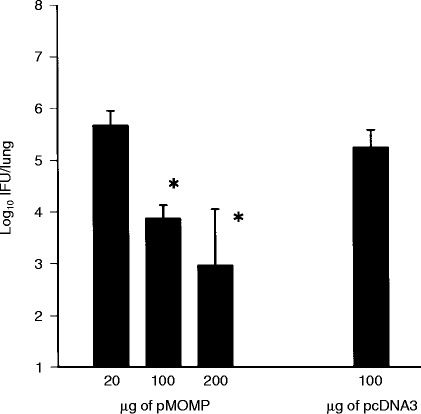

Prior to evaluating immune responses elicited by MOMP DNA vaccination, we determined the degree of protective immunity elicited by immunization of groups of mice with 20 μg, 100 μg, or 200 μg of DNA per vaccination session given at 0, 3, 6 and 8 weeks. Control mice received 100 μg of plasmid vector DNA without the MOMP gene insert. As shown in Fig. 1, increasing amounts of MOMP DNA produced an increasing measure of protective immunity. Because 200 μg of MOMP DNA vaccination produced the greatest degree of protective immunity among the doses tested (2·5 log10 reduction in peak organism growth compared to the control group), immune responses elicited by immunization with this amount of DNA were analysed in the following studies.

Figure 1.

Protective immunity elicited by MOMP DNA (pMOMP) vaccination. BALB/c mice (4–5/group) were immunized with different amounts of the pMOMP DNA intramuscularly on four occasions at 0, 3, 6, 8 weeks. 100 μg of vector DNA (pcDNA3) was injected intramuscularly as a negative control on the same occasions. The mice were challenged with 5×103 IFU of MoPn EB intranasally and killed on the 10th day postinfection. The MoPn growth in the lung was analysed by quantitative tissue culture. The data represents mean +SEM of the log10 IFU per lung. *P < 0·05 when compared with pcDNA3 treated group.

Cellular immune responses

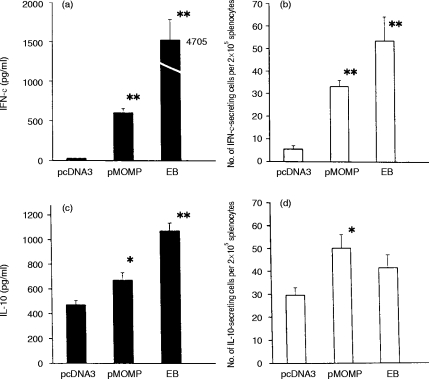

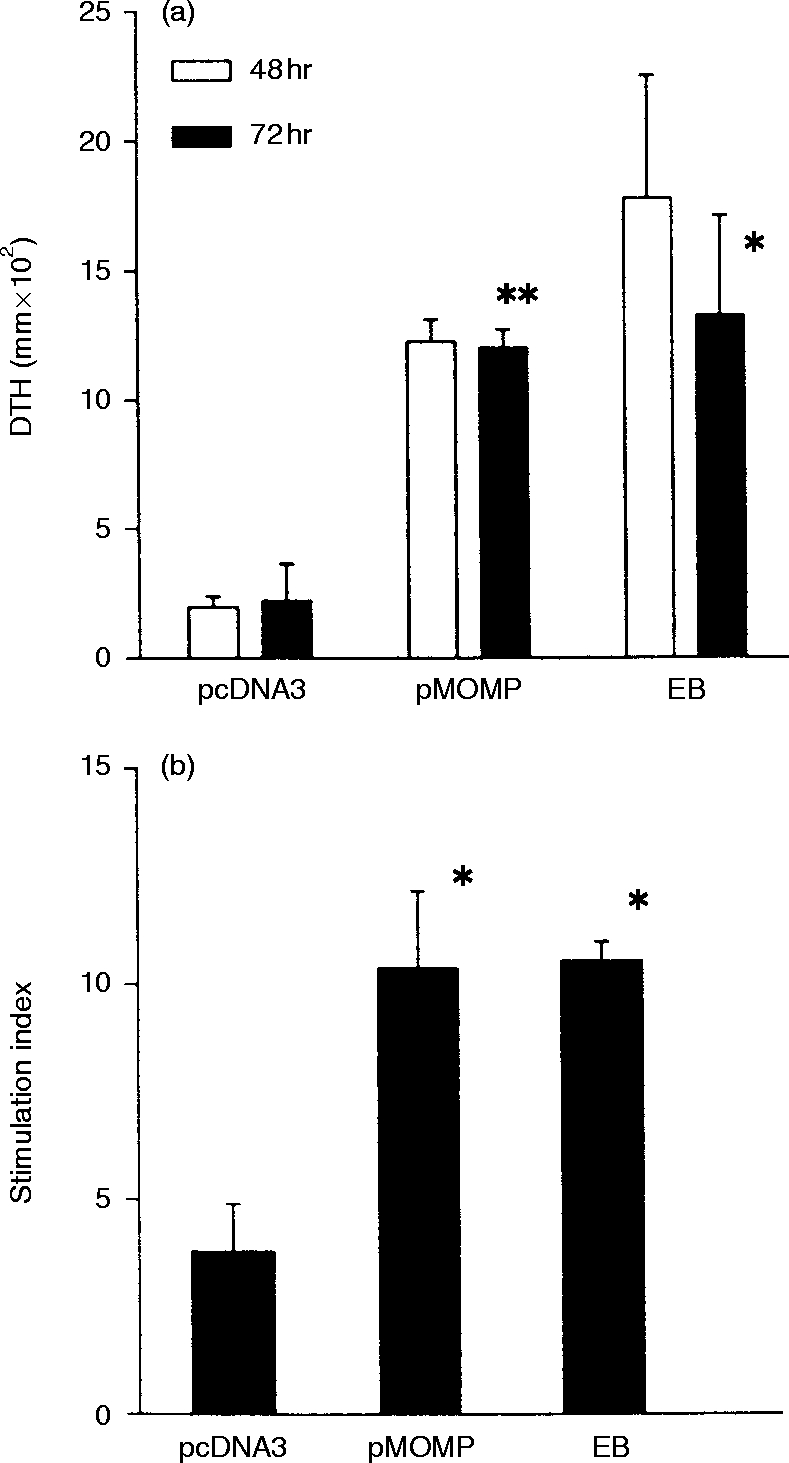

Consistent with our previous report,25 MOMP DNA immunization induced significant DTH reactions which were comparable in size to those elicited by immunization with whole MoPn EBs (Fig. 2a). Splenocytes collected at day 14 after the fourth immunization from groups of mice immunized with MOMP DNA (pMOMP) or with whole EBs proliferated to a similar extent (stimulation index 10) following chlamydia restimulation (Fig. 2b). Splenocytes collected from mice immunized with the blank vector showed a marginal level of proliferation (SI<5) which was significantly lower than that of MOMP DNA immunized mice (P < 0·05). These results show that MOMP DNA immunization elicits both DTH and lymphoproliferative responses that are capable of recall by whole MoPn EBs.

Figure 2.

(a) The DTH reaction in mice elicited by immunization by MOMP DNA immunization. BALB/c mice (four/group) were immunized by 200 μg of MOMP DNA (pMOMP) or vector DNA (– pcDNA3) in both quadriceps muscles (100 μg DNA/100 μl/injection site) on four occasions at 0, 3, 6, 8 weeks. A group of mice were also immunized intramuscularly with 5×106 IFUs of UV-inactivated MoPn EBs on the same time schedule. DTH was evaluated 2 weeks after last immunization. UV-killed MoPn EB (25 μl; 2×105 IFU) in SPG buffer was injected into a hind footpad. SPG buffer (25 μl) was injected into the other hind footpads as control. Footpad swelling was measured at 48 hr and 72 hr following the injection. The difference in thickness between the two footpads was used as a measure of the DTH. (b) Lymphocyte proliferation of the mice immunized with pMOMP. BALB/c mice (four to six/group) were immunized with pMOMP, pcDNA3 or MoPn EBs as described in (a). Mice were killed 2 weeks after the last immunization. 5×105 cells/well of spleen cells in 200 μl of RPMI-1640 medium containing 10% FCS and 5×10−5 M 2ME were incubated with 1×105 IFU of UV killed MoPn in 5% CO2 at 37° for 96 hr. Negative control wells contained spleen cells without EB. 3H-Thymidine (0·25 μCi) was added 16 hr before harvest. The cells were harvested after incubation for 96 hr and 3H-thymidine uptake was counted in scintillation solution using a Beckman LS5000 B-counter. *P < 0·05, **P < 0·01, when compared with the pcDNA group.

Cytokine responses

Considerable data suggest that in the mouse model of MoPn infection, CD4 T lymphocytes that secrete IFN-γ are an important effector of acquired immunity. The induction of antigen-specific production of IFN-γ and IL-10 following MOMP DNA immunization was therefore examined. Cytokines were measured as protein secretion using ELISA assays and as cytokine secreting splenocytes using ELISPOT assays. As shown in Fig. 3, MOMP DNA immunization induced splenocytes that secreted IFN-γ in response to in vitro MoPn EB stimulation measured by both the ELISA and ELISPOT assays (Fig. 3a,b). Although IL-10 responses were elicited by MOMP DNA immunization (Fig. 3c,d), the magnitude of IL-10 secretion following MOMP-DNA immunization over blank vector immunization (1·46-fold) was much less than that observed for IFN-γ (24-fold) responses. The data suggest that MOMP DNA immunization predominantly induces Th1-like T-cell cytokine responses in vivo.

Figure 3.

Profile of IFN-γ and IL-10 production by spleen cells isolated from pMOMP-immunized mice. Mice (four to six) were immunized by pMOMP, pcDNA3 or MoPn EB as described in Fig. 2. Spleen cells were collected two weeks after the last immunization. Spleen cells (5×106 cells/ml) were incubated with 2×105 IFU of UV-killed MoPn EB for 96 hr. The amount of IFN-γ (a) and IL-10 (c) in the supernatant of the cell culture was measured by ELISA. The number of IFN-γ- (b) and IL-10- (d) producing cells per 2×105 spleen cells was tested by ELISPOT. *P < 0·05, **P < 0·01, when compared with pcDNA3-immunized control group.

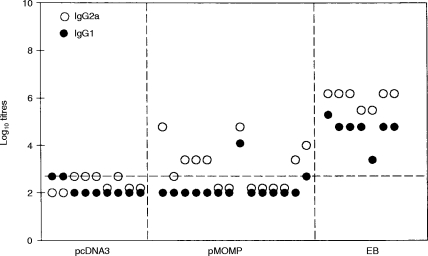

Humoral immune responses

Isotype specific (IgG1, IgG2a and IgA) serum antibodies to whole MoPn EBs was measured by ELISA and MOMP-specific antibodies were measured by an immunoblot assay. Results are shown for each individual mouse because of unexpected variation in humoral responses.

No serum IgA antibodies that reacted with whole MoPn EBs were detected following MOMP DNA intramuscular immunization. Serum IgG2a antibodies to MoPn EBs were observed in seven of 14 MOMP DNA immunized mice; one of 14 mice also had IgG1 antibodies (Fig. 4). The titers of serum antibodies were 10–1000-fold less in mice immunized with MOMP DNA than among mice immunized with whole EBs. Good correlation was observed between anti-MOMP antibodies in the immunoblot assay and anti-EB antibodies detectable in the ELISA assay (Fig. 5). Ten of 14 mice had anti-MOMP antibodies by immunoblot analysis following DNA immunization. Unlike MoPn EB immunization which elicits both IgG1 and IgG2a antibody, DNA immunization mainly elicits IgG2a antibody.

Figure 4.

The profile of IgG subclass of MoPn-specific Ab responses in serum of mice immunized with pMOMP. Balb/c mice were immunized by pMOMP or pcDNA3 or MoPn EB as described in Fig. 2. Sera were collected from the immunized mice 2 weeks after last immunization. MoPn-specific IgG1 and IgG2a Abs were tested by ELISA. The cutoff point was 0·5 on OD 405 nm.

Figure 5.

Detection of serum antibody against MoPn MOMP in pMOMP immunized mice by immunoblot. Balb/c mice were immunized with pMOMP (lane 1–12), or pcDNA3 (lane pc1 and pc2) or MoPn EB (lane EB) as described in Fig. 1(a). Lane N is the serum collected from a nonimmunized mouse. Sera collected from immunized mice at two weeks post last immunization were diluted at 1:100 and reacted with purified MoPn MOMP protein that had been separated in 10% SDS–polyacrylamide gel and transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane. The bands were developed by the ECL method.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we analysed protective immunity induced by DNA vaccination as measured by organism clearance following challenge infection. Although most vaccinated mice could still be infected by challenge infection, their chlamydial burden in the lung was significantly reduced. The data provide further evidence for the protective effects of DNA vaccination using the MOMP gene of C. trachomatis. The degree of protective immunity elicited by MOMP DNA was directly correlated with the amount of DNA injected and was significantly greater at higher amounts of DNA (100 and 200 μg) than at lower amounts (20 μg). The observation that relatively large amounts of immunizing DNA are required to induce protective immunity may suggest that the mechanisms by which ‘naked’ DNA is taken up, mRNA expressed and protein presented to the immune system are relatively inefficient. Additionally, the eucaryotic expression plasmid we chose for study (pcDNA3) may not be optimal and other plasmid constructs that permit greater antigen expression may result in enhanced immunogenicity.

Immunologic evaluation showed that both cellular and humoral immune responses were generated by MOMP DNA vaccination. All MOMP DNA immunized mice demonstrated DTH and lymphoproliferative responses which were as great in magnitude as those elicited by MoPn EB immunization. Antigen specific cytokine responses were also elicited by MOMP DNA immunization although the magnitude of IFN-γ production was eightfold less than that elicited by MoPn EB vaccination. This difference correlates with the greater degree of protective immunity engendered by EB immunization than by parenteral MOMP DNA immunization seen in this model system.25 Surprisingly, the ELISPOT assay showed that MOMP DNA and MoPn EB vaccination elicited a similar frequency of antigen-specific IFN-γ secreting cells. Associated with the larger amount of IFN-γ secreted by splenocytes from MoPn EB immunized mice was the observation that the intensity of blue staining around cells in the ELISPOT assay from EB-immunized mice was noticeably greater than from MOMP DNA-immunized mice (data not shown). This could suggest that each antigen-specific cell secreted greater amounts of IFN-γ from EB-immunized animals than from DNA-immunized animals. IL-10 secretion was also elicited by MOMP DNA immunization but the magnitude of increase over that seen following immunization with the blank vector was much less than that observed for IFN-γ. Notably, background IL-10 production and the number of IL-10 producing cells in mice without MOMP DNA or EB immunization (pcDNA3 group, Fig. 3) was relatively high. Induction of poor IL-10 responses by a MOMP vaccine may be a desirable property because IL-10 deactivates macrophages30 and prolongs chlamydial infection in the murine model.27

While all mice developed measurable cell-mediated immunity, only 50–70% developed measurable serum antibody responses. Isotype analysis showed that mainly Th1-dependent antibodies (that is IgG2a) were produced following DNA immunization whereas both Th1- and Th2-related antibodies (IgG2a and IgG1) were produced following MoPn EB immunization. The antibody titers were generally low for MOMP DNA immunization compared to whole EB immunization. Antibody responses were also more variable with DNA immunization than with EB immunization. The heterogeneity in B-cell responses was not solely related to producing antibody to non-native antigenic determinants on the MOMP following DNA immunization. This is because results in the ELISA assay using whole EBs were parallelled by results in the immunoblot assay using MOMP protein.

The reason for deficiency of MOMP DNA immnization in inducing antibody upon DNA immunization response is unclear from our studies. It may be that DNA immunization stimulates CD4 T cells and B cells through cross-priming, as has been recently established for CD8 T-cell responses induced by DNA immunization.31,32 Thus, one possible explanation for the poor induction of B-cell responses may be related to the fact that the MOMP DNA and plasmid vector carry multiple CpG immunostimulatory DNA sequences (ISSs) that function as Th1-promoting adjuvants.33–36 ISSs cause IFN-α and IFN-β production and these cytokines could inhibit antigen synthesis by plasmid transfected cells to a level below which B-cell responses are reliably evoked but above which T-cell responses can proceed. Nevertheless, the MOMP gene immunized mice that showed undetectable antibody responses were also protected by the vaccination, suggesting the importance of the T-cell response in protective immunity.

It should be noted that, although the data show significant protection and immune responses induced by MOMP DNA vaccination, further studies are required to elucidate the mechanism by which vaccination mediates protection and to clarify and improve the efficacy and safety of this vaccine. In particular, the following aspects should be considered in future studies: (i) although organism clearance was accelerated by DNA vaccination, most vaccinated mice were still infected by challenge infection, indicating the requirement for improved efficacy; (ii) it is not clear whether MOMP DNA vaccination can induce mucosal IgA production; (iii) this study examined the effectiveness of vaccination using only a lung infection model. Because sexually transmitted diseases and trachoma represent the most common diseases caused by chlamydial infection, further study using genital tract and/or ocular infection models should be informative concerning vaccine usefulness in preventing/resolving these diseases; and (iv) the present study did not address the question of potential immunopathology induced by vaccination. In particular, although DTH response has been demonstrated to be protective against chlamydial infection, some studies also suggest that DTH may be responsible for tissue damage induced by infection.37,38 However, recent data show that IL-10 gene knockout mice mount significantly stronger DTH responses without exhibiting granuloma formation and fibrosis following MoPn lung infection that occurs among wild-type mice. This suggests an inhibitory effect of DTH on chlamydial immunopathology (Yang et al., unpublished data).

In conclusion, parenteral immunization with MOMP DNA generates both cellular and humoral immune responses. The cellular immune assays, cytokine assays and antibody isotype analysis suggest that MOMP DNA immunization generates a polarized Th1 immune response.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from the Medical Research Council of Canada (GR13301), the Canadian Bacterial Diseases Network Centers of Excellence and Pasteur Mérieux Connaught, Canada.

References

- 1.Brunham RC. Vaccine design for the prevention of Chlamydia trachomatis infection. In: Orfila J, Byme G I, Chernesky M A, editors. Chlamydial Infections Proceedings of the Eighth International Symposium on Human Chlamydial Infections (Chantilly, France) Bologna, Italy: Società Editrice Esculapio; 1994. p. 73. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brunham RC, Peeling RW. Chlamydia trachomatis antigens: role in immunity and pathogenesis. Infectious Agents and Disease. 1994;3:218. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stephens RS. Challenge of Chlamydia research. Infectious Agents and Disease. 1993;1:279. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brunham RC, Kimani J, Bwayo J, et al. The epidemiology of Chlamydia trachomatis within a sexually transmitted diseases core group. J Infect Dis. 1996;173:950. doi: 10.1093/infdis/173.4.950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jawetz E, Rose L, Hanna L, Thygeson P. Experimental inclusion conjunctivitis in man. JAMA. 1965;194:620. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Grayston JT, Wang S-P. The potential for vaccine against infection of the genital tract with Chlamydia trachomatis. Sex Trans Dis. 1978;5:73. doi: 10.1097/00007435-197804000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sowa S, Sowa J, Collier LH, Blyth WA. Trachoma vaccine field trials in The Gambia. J Hyg Camb. 1969;67:699. doi: 10.1017/s0022172400042157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Collier LH. Experiments with trachoma vaccines: Experimental system using inclusion blennorrhoea virus. Lancet. 1961;1:795. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(61)90119-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Woolridge RL, Grayston JT, Chang IH, Cheng KH, Yang CY, Neave C. Field trial of a monovalent and of a bivalent mineral oil adjuvant trachoma vaccine in Taiwan school children. Am J Ophthalmol. 1967;63:1645. doi: 10.1016/0002-9394(67)94158-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Morrison RP, Manning DS, Caldwell HD. Immunology of Chlamydia trachomatis infections: Immunoprotective and immunopathogenetic responses. In: Gallin J I, Fauci A S, editors. Advances in Host Defense Mechanisms: Sexually Transmitted Diseases. Vol. 8. New York: Raven Press; 1992. p. 57. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Batteiger BE, Rank RG, Bavoil PM, Soderberg LSF. Partial protection against genital reinfection by immunization of guinea-pigs with isolated outer-membrane proteins of the chlamydial agent of guinea-pig inclusion conjunctivitis. J Gen Microbiol. 1993;139:2965. doi: 10.1099/00221287-139-12-2965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Campos M, Pal S, O’Brien TP, Taylor HR, Prendergast RA, Whittum-Hudson JA. A chlamydial major outer membrane protein extract as a trachoma vaccine candidate. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1995;36:1477. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jones GE, Jones KA, Machell J, Brebner J, Anderson IE, How S. Efficacy trials with tissue-culture grown, inactivated vaccines against chlamydial abortion in sheep. Vaccine. 1995;13:715. doi: 10.1016/0264-410x(94)00068-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pal S, Theodor I, de Peterson EM, la Maza LM. Immunization with an acellular vaccine consisting of the outer membrane complex of Chlamydia trachomatis induces protection against a genital challenge. Infect Immun. 1997;65:3361. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.8.3361-3369.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tan T-W, Herring AJ, Anderson IE, Jones GE. Protection of sheep against Chlamydia psittaci infection with a subcellular vaccine containing the major outer membrane protein. Infect Immun. 1990;58:3101. doi: 10.1128/iai.58.9.3101-3108.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Taylor HR, Whittum-Hudson J, Schachter J, Caldwell HD, Prendergast RA. Oral immunization with chlamydial major outer membrane protein (MOMP) Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1988;29:1847. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tuffrey M, Alexander F, Conlan W, Woods C, Ward M. Heterotypic protection of mice against chlamydial salpingitis and colonization of the lower genital tract with a human serovar F isolate of Chlamydia trachomatis by prior immunization with recombinant serovar L1 major outer-membrane protein. J Gen Microbiol. 1992;138:1707. doi: 10.1099/00221287-138-8-1707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Su H, Parnell M, Caldwell HD. Protective efficacy of a parenterally administered MOMP-derived synthetic oligopeptide vaccine in a murine model of Chlamydia trachomatis genital tract infection: Serum neutralizing IgG antibodies do not protect against chlamydial genital tract infection. Vaccine. 1995;13:1023. doi: 10.1016/0264-410x(95)00017-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Murdin AD, Su H, Klein MH, Caldwell HD. Poliovirus hybrids exprressing neutralization epitopes from variable domains I and IV of the major outer membrane protein of Chlamydia trachomatis elicit broadly cross-reactive C. trachomatis-neutralizing antibodies. Infect Immun. 1995;63:1116. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.3.1116-1121.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Murdin AD, Su H, Manning DS, Klein MH, Parnell MJ, Caldwell HD. A poliovirus hybrid expressing a neutralization epitope from the major outer membrane protein of Chlamydia trachomatis is highly immunogenic. Infect Immun. 1993;61:4406. doi: 10.1128/iai.61.10.4406-4414.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hayes LJ, Conlan JW, Everson JS, Ward ME, Clarke IN. Chlamydia trachomatis major outer membrane protein epitopes expressed as fusions with LamB in an attenuated aroA strain of Salmonella typhimurium; their application as potential immunogens. J Gen Microbiol. 1991;137:1557. doi: 10.1099/00221287-137-7-1557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yang X, Brunham RC. T-lymphocyte immunity in host defence against Chlamydia trachomatis and its implications for vaccine development. Can J Infect Dis. 1998;9:99. doi: 10.1155/1998/395297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Holland MJ, Bailey RL, Conway DJ, et al. T helper type-1 (Th1) /Th2 profiles of peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC); responses to antigens of Chlamydia trachomatis in subjects with severe trachomatous scarring. Clin Exp Immunol. 1996;105:429. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2249.1996.d01-792.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mabey D, Bailey R. Immunity to Chlamydia trachomatis: Lessons from a Gambian village. J Med Microbiol. 1996;45:1. doi: 10.1099/00222615-45-1-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhang D-J, Yang X, Berry J, Shen C, McClarty G, Brunham RC. DNA vaccination with the major outer-membrane protein gene induces acquired immunity to Chlamydia trachomatis (mouse pneumonitis) infection. J Infect Dis. 1997;176:1035. doi: 10.1086/516545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Peeling RW, Maclean IW, Brunham RC. In vitro neutralization of Chlamydia trachomatis with monoclonal antibody to an epitope on the major outer membrane protein. Infect Immun. 1984;46:484. doi: 10.1128/iai.46.2.484-488.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yang X, Hayglass KT, Brunham RC. Genetically determined differences in IL-10 and IFN-γ responses correlate with clearance of Chlamydia trachomatis mouse pneumonitis infection. J Immunol. 1996;156:4338. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Vancott JL, Staats HF, Pascual DW, et al. Regulation of mucosal and systemic antibody responses by T helper cell subsets, macrophages, and derived cytokines following oral immunization with live recombinant salmonella. J Immunol. 1996;156:1504. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Maclean I, Peeling RW, Brunham RC. Characterization of Chlamydia trachomatis antigens with monoclonal and polyclonal antibodies. Can J Microbiol. 1988;34:141. doi: 10.1139/m88-028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mosmann TR. Properties and functions of interleukin 10. Adv Immunol. 1994;56:1. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Donnelly JJ, Ulmer JB, Shiver JW, Liu MA. DNA vaccines. In: Paul WE, Fathman CG, Metzger H, editors. Annual Review of Immunology. Vol. 15. California: Annual Reviews Inc.; 1997. p. 617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fu T-M, Ulmer JB, Caulfield MJ, et al. Priming of cytotoxic T lymphocytes by DNA vaccines: Requirement for professional antigen presenting cells and evidence for antigen transfer from myocytes. Molec Med. 1997;3:362. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Klinman DM, Yi A-K, Beaucage SL, Conover J, Krieg AM. CpG motifs present in bacterial DNA rapidly induce lymphocytes to secrete interleukin 6, interleukin 12, and interferon γ. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:2879. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.7.2879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Krieg AM, Yi A-K, Matson S, et al. CpG motifs in bacterial DNA trigger direct B-cell activation. Nature. 1995;374:546. doi: 10.1038/374546a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sato Y, Roman M, Tighe H, et al. Immunostimulatory DNA sequences necessary for effective intradermal gene immunization. Science. 1996;273:352. doi: 10.1126/science.273.5273.352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schwartz DA, Quinn TJ, Thorne PS, Sayeed S, Yi A-K, Krieg AM. CpG motifs in bacterial DNA cause inflammation in the lower respiratory tract. J Clin Invest. 1997;100:68. doi: 10.1172/JCI119523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Watkins NGWJ, Hadlow AB, Moos, Caldwell HD. Ocular delayed hypersensitivity: a pathogenetic mechanism of chlamyial conjuctivitis in guinea pigs. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1986;83:7480. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.19.7480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Taylor HR, Johnson SL, Schachter J, Caldwell HD, Prendergast RA. Pathogenesis of trachoma: the stimulus for inflammation. J Immunol. 1987;138:3023. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]