Abstract

A newly generated monoclonal antibody (mAb C9.1) described in this study identifies a surface membrane molecule that is involved in the lytic programme of activated natural killer (NK) cells. This conclusion is based on the facts that, first, this antigen was expressed on the vast majority of surface immunoglobulin (sIg)− CD3− CD4− CD8− spleen lymphocytes, albeit it was also present on minor subsets of sIg+ B (≈7%) and CD3+ T (≈2%) lymphocytes; second, that all splenic NK activity was contained within the C9.1+ cell population, and was almost totally abolished by treatment of spleen cells with mAb C9.1 and complement; third, that mAb C9.1 was capable of increasing interleukin-2-cultured and in vivo polyinosinic:polycytidylic acid-activated, NK cell-mediated, antibody-redirected lysis, but not freshly isolated NK cell-mediated killing. Furthermore, the strain distribution of the C9.1 antigen was shown to be antithetical to that of the 2B4 antigen already described as a molecule associated with major histocompatibility complex-unrestricted killing mediated by activated NK cells. The gene encoding C9.1 antigen was linked to the Akp1 isozyme locus on chromosome 1 close to the 2B4 gene. Although C9.1 and 2B4 were monomeric glycoproteins of 78 000 MW and 66 000 MW, respectively, removal of N-linked sugars from both antigens by endoglycosidase F yielded identical protein backbones of 38 000 MW. Thus, all of these results suggest that mAb C9.1 recognizes an allelic form of the 2B4 antigen. However, the detection of mAb C9.1-reactive antigen on a minor subset of B cells may suggest a possible reactivity of mAb C9.1 with some product of other members of the 2B4 family genes.

INTRODUCTION

Natural killer (NK) cells comprise a population of large granular lymphocytes that can mediate ex vivo lysis of a variety of target cells, including virus-infected cells and tumour cells, without prior sensitization and that can secrete cytokines such as interferon-γ, tumour necrosis factor and granulocyte–macrophage colony-stimulating factor upon activation.1 They are thought to play an important role both in natural immunity against viral and bacterial infections and in tumour surveillance.1–3 NK cells also mediate the rejection of bone marrow allografts.4

Recent cumulative data support the notion that the NK-cell functions are regulated by a balance between positive and negative signalling mediated by two sets of receptors, i.e. inhibitory receptors, and activation receptors.5,6 The inhibitory receptors include members of the Ly-49 gene family in mice and the killer cell inhibitory receptor gene family in humans. Engagement of the inhibitory receptors with major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class I antigen, the ligand of these receptors, on target cells transmits negative signals preventing cytolysis of the target cells. On the other hand, a variety of different molecules have been reported to be involved in NK-cell activation pathways;7–14 some of those putative activation molecules are expressed at the cell surface only after cell activation by cytokines.12–14 Thus, NK cells can probably interact with target cells by a variety of different cell surface ligands, depending on the nature of the target cells and the cytokines available in the milieu of the surrounding tissues.15,16

In mice the NK1.1 (NKR-P1C)8,17 and the 2B49,18,19 represent candidate activation receptors. The 2B4 molecule is a 66 000 MW membrane glycoprotein of the immunoglobulin gene superfamily encoded by a member of the 2B4 family genes on chromosome 1 in close proximity to the Fcgr3 gene, and its expression is restricted to cells that can mediate MHC-unrestricted killing.9,19 Despite the fact that 2B4 mRNA is detected in many mouse strains, the available anti-2B4 monoclonal antibody (mAb) binds to NK cells from C57BL/6 mice but not NK cells from other strains, which suggests that the anti-2B4 mAb recognizes the allotypic determinant of the 2B4 gene product that is expressed in all of the mouse strains.18 Antibody detecting the relevant allelic gene product has not been produced so far.

Our attempts to produce mAb specific for our recently established MHC-unrestricted killer hybridomas20 have led us to the isolation of several mAb reactive with surface membrane molecules involved in MHC-unrestricted cytotoxicity.21 In the present study we focused on the characterization of one of those mAb, termed mAb C9.1, and we found that mAb C9.1 identifies an allelic form of the 2B4 antigen.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell lines and mice

MHC-unrestricted killer hybridomas were produced in our laboratory.20 Daudi, Burkitt’s lymphoma cell line, was obtained from Human Science Research Resources Bank (Osaka, Japan) and was maintained in RPMI-1640 medium containing 20% fetal calf serum (FCS). Sp2/O, YACUT, EL4, BW5147 and L5178Y cells were maintained in RPMI-1640 medium supplemented with 10% FCS. C3H/He, BALB/c, DBA/2, AKR/N, A/J, CBA/N, C57BL/6 and NZB/N mice were purchased from Japan SLC (Shizuoka, Japan). C58/J, SJL/J and 129/Svj mice were obtained from the National Institute of Genetics, Mishima, Japan. A new inbred mouse strain, tentatively designated as YNA, was established from a subline of Slc:ddY mice at the Central Institute for Experimental Animals (Kawasaki, Japan). LEW rats were purchased from the Nippon Bio-Supp. Centre (Tokyo, Japan).

Monoclonal antibodies and reagents

The mAb used were fluorescence isothiocyanate (FITC)-labelled anti-CD3 (145-2C11), FITC-labelled anti-T-cell receptor (TCR)αβ (H-57-597), FITC-labelled anti-TCRγδ (GL3), FITC-labelled anti-2B4, phycoerythrin (PE)-labelled anti-NK1.1 (PK136), PE-labelled anti-B220 (RA3-6B2), PE-labelled anti-CD4 (GK1.5) and PE-labelled anti-CD8 (53-6.7). They were all purchased from PharMingen (San Diego, CA). Hybridomas producing mAb FD441.8 [anti-lymphocyte function-associated antigen-1 (LFA-1); rat IgG2b] and GK1.5 (anti-CD4) were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC; Rockville, MD) and mAb were prepared in our laboratory. Biotinylated rabbit anti-mouse immunoglobulins and recombinant protein G–Sepharose 4B were purchased from Zymed Laboratories, Inc. (San Francisco, CA). Anti-Lyt2.1 (anti-CD8) mAb was purchased from the Meiji Institute of Health Science (Tokyo, Japan). Human recombinant interleukin-2 (rIL-2) was obtained from Shionogi Pharmaceutical (Osaka, Japan). Low-tox M rabbit C′ was purchased from Cedarlane (Westbury, NY). Anti-rat κ light-chain mAb (mouse IgG2a) was purchased from Harlan (Sussex, UK). The mAb H12 (rat IgG2b), reactive with some lymphomas such as BW5147 and EL4, was produced in our laboratory and was used as an isotype-matched control antibody. Endoglycosidase F/N-glycosidase F was purchased from Boehringer Mannheim (Mannheim, Germany).

Preparation of mAb C9.1

LEW rats were immunized intraperitoneally with 10×106 cells of the 7D4 killer hybridoma.21 After 3–4 weeks the rats were boosted by intraperitoneal injection of 10×106 7D4 cells and after 3 days the spleen was removed, and a spleen cell suspension was prepared and then fused with the BALB/c myeloma cell line Sp2/O. A hybridoma producing mAb, termed C9.1, which stained 7D4 killer hybridoma, but not several lymphoma cell lines, such as EL4, YACUT, L5178Y and BW5147, was isolated and subcloned twice by limiting dilution. The mAb was of the IgG2b (κ light-chain) isotype as determined by Ouchterlony immunoprecipitation. The C9.1 mAb was purified by diethylaminoethyl (DEAE)– cellulose chromatography. The purified antibodies were fluorescein or biotin conjugated according to the methods described elsewhere.22

Flow cytometric analysis of surface antigens

The surface phenotype of lymphocyte populations was determined by single- or two-colour immunofluorescence with mAb using a fluorescence-activated cell sorter (FACScan; Becton-Dickinson, Sunnyvale, CA). C9.1+ and C9.1− cells were sorted from C3H/He nylon wool non-adherent (NWNA) spleen cells (this treatment routinely resulted in >95% depletion of B cells as determined by flow cytometry analysis) using a FACStar Plus (Becton-Dickinson). The mAb were either biotinylated or directly conjugated to FITC or PE. Biotinylated reagents were detected with PE–Streptavidin.

Cytotoxic assay

This method has been described previously.20 Spleen cells from mice injected intraperitoneally with 100 μg of polyinosinic: polycytidylic acid (polyI:C) 16 hr before assay (polyI:C- activated NK cells) or C3H/He A-LAK cells or freshly isolated NK cells were used as effector cells for standard 4-hr 51Cr-release assays.

Depletion of NK activity by complement-dependent cytotoxicity

This was accomplished by incubation of 10×106 spleen cells from polyI:C-treated mice with 1 ml of C9.1 hybridoma tissue culture supernatants. After incubation at 4° for 1 hr, the cells were washed and further incubated with anti-rat κ light-chain mAb at 4° for 30 min. The cells were washed twice, suspended in 1 ml rabbit complement diluted 1/11 with RPMI-1640 medium containing 0·3% bovine serum albumin (BSA), and incubated at 37° for 1 hr. The cells were washed and resususpended to original volume with RPMI-1640 medium supplemented with 10% FCS and assayed against YAC-1 cells in 4-hr 51Cr-release assays at various effector:target ratios. Controls consisted of effector cells treated with anti-rat κ light-chain mAb and complement alone. Lysis was quantified as lytic units, where one lytic unit was defined as the number of cells necessary for lysis of 10% of 1×104 target cells during a 4-hr 51Cr-release assay.

Analysis of the allelic forms of AKP1 isozyme

This method has been described previously.23

Radioiodination, immunoprecipitation and sodium dodecylsulphate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS–PAGE)

These methods have been described previously.21 For endoglycosidase F digestion,24 immune complexes bound to protein G–Sepharose 4B were eluted in 100 μl of antigen elution buffer (100 mm Tris–HCl, pH 7·5, 1% SDS, 1% 2-mercaptoethanol), centrifuged, and the supernatant fluids were collected. One millilitre of endoglycosidase F buffer (0·1 m potassium phosphate, pH 6·1, 1% Triton-X-100, 0·1% SDS, 45 mm ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid, 1% 2-mercaptoethanol) containing 1 unit of endoglycosidase F/N-glycosidase F was added to the supernatant and the samples were incubated at 37° overnight. The protein was precipitated by adding 100 μl of 100% trichloroacetic acid (TCA) and washed three times with ice-cold acetone by centrifugation. The protein was dissolved in SDS–sample buffer (0·065 m Tris–HCl, pH 6·8, 2% SDS, 10% glycerol, 5% 2-mercaptoethanol) and analysed on 10% SDS–PAGE.

Preparation of adherent LAK (A-LAK) cells

This method has been described previously.21

Freshly isolated NK cell preparation

NWNA spleen cells were incubated on ice for 30 min with ascites preparations of anti-CD4 (GK1.1) and anti-Lyt2.1 mAb diluted 1/100 in RPMI-1640 medium containing 0·3% BSA. The cells were washed and resuspended at 10×106/ml in rabbit complement diluted 1/11 with RPMI-1640 medium containing 0·3% BSA. The cell suspension was incubated at 37° for 1 hr. The cells were layered on Ficoll Metrizoate (14% Ficoll 400, 32·8% sodium metrizoate) followed by centrifugation. Viable cells at the interface were collected and used as effector cells for 4-hr 51Cr-release assays.

RESULTS

Tissue distribution of C9.1 antigen

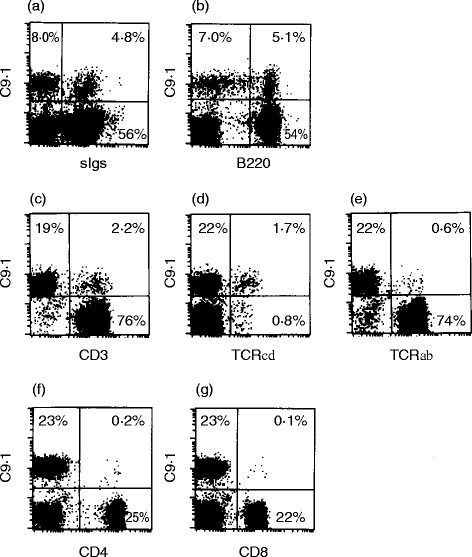

Table 1 shows the reactivity of mAb C9.1 with lymphocytes from various tissues of C3H/He mice. FITC-labelled mAb C9.1 stained ≈11% of spleen lymphocytes, ≈2% of lymph node lymphocytes and ≈20% of liver lymphocytes, but it hardly stained thymocytes. Two-colour immunofluorescence analyses were next performed on spleen lymphocytes from C3H/He mice and representative results are shown in Fig. 1. As shown in Fig. 1(a,b), ≈40% of C9.1+ spleen cells were sIg+ B220+ B cells25 and the rest were sIg−. To analyse mAb C9.1 reactivity with sIg− spleen cells, further analyses were performed on B-cell-depleted NWNA spleen lymphocytes. The majority of C9.1+ sIg− cells (≈90%) were CD3−, but 2% of CD3+ T cells also expressed C9.1 (Fig. 1c). As shown in Fig. 1(d,e), ≈75% of the C9.1+ CD3+ T cells were γδ T cells and the rest were αβ T cells. The vast majority of C9.1+ cells were CD4− and CD8− (Fig. 1f,g). Overall, these results indicate that about half of C9.1+ spleen cells display a sIg− CD3− CD4− CD8− phenotype and the rest are sIg+ B cells (≈40%) and CD3+ T cells (≈10%).

Table 1.

Tissue distribution of C9.1 antigen in C3H/He mice

*Number of mice tested in parentheses. †Lymphocytes from each tissue were stained with FITC-labelled mAb C9.1 and analysed on FACScan. ‡Liver lymphocytes were prepared as described elsewhere.28

Figure 1.

Two-colour immunofluorescence (flow cytometry) analyses of surface expression of an antigen recognized by mAb C9.1 on C3H mouse spleen lymphocytes. Spleen lymphocytes (a and b) or B-cell-depleted NWNA spleen lymphocytes (c–g) were stained with FITC-labelled mAb C9.1 or biotinylated mAb C9.1 and simultaneously with biotinylated or FITC- or PE-conjugated anti-sIg (a), anti-CD45 (B220) (b), anti-CD3 (c), anti-TCRγδ (d), anti-TCRαβ (e), anti-CD4 (f), or anti-CD8 (g). Biotinylated antibodies were detected with PE– Streptavidin.

All NK activity is ascribed to C9.1+ cells

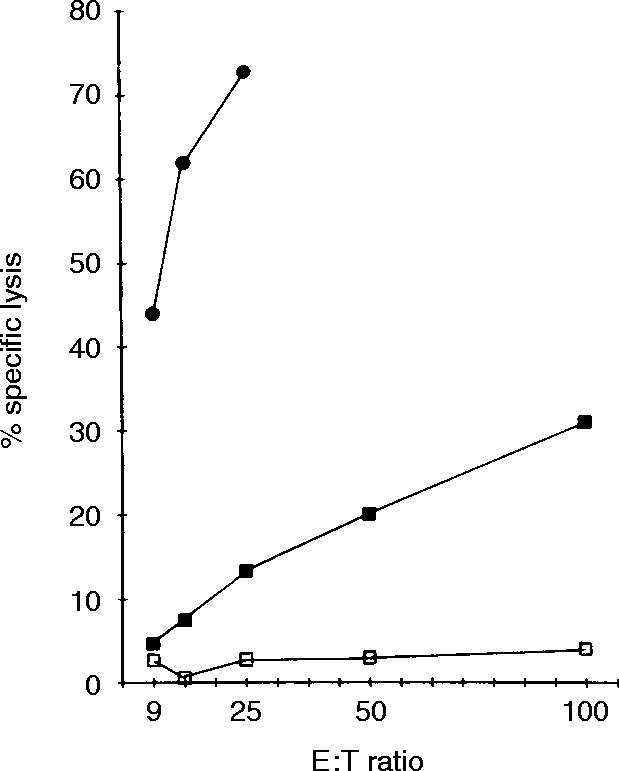

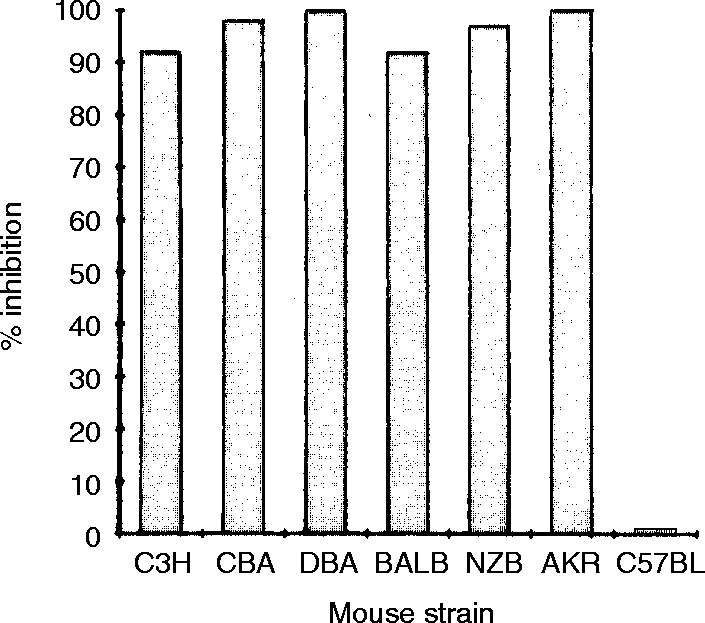

To determine whether sIg− CD3− C9.1+ cells are NK cells, C9.1+ cells were sorted from C3H/He NWNA spleen cells and assessed for their ability to lyse YAC-1 cells. As shown in Fig. 2, all of the lytic activity can be sorted in the C9.1+ cell population. Susceptibility of spleen cells to the complement-dependent NK-inhibitory activity of mAb C9.1 was next examined using various mouse strains (Fig. 3). In all of the strains examined, except for C57BL/6 mice, splenic NK activity was almost totally abolished by the treatment of spleen cells with mAb C9.1 and complement. These results indicate that C9.1 antigen is expressed by all NK cells in various mouse strains other than C57BL/6 mice.

Figure 2.

Lysis of YAC-1 cells by C9.1+ and C9.1− spleen cells. NWNA spleen cells prepared from C3H/He mice pretreated with polyI:C 16 hr before 51Cr-release assays were sorted into C9.1+(•) and C9.1− (□) cells and were used as effector cells; unsorted NWNA cells (▪).

Figure 3.

Complement-dependent NK-inhibitory activity of mAb C9.1. PolyI:C-activated spleen lymphocytes from a variety of inbred mouse strains were incubated with mAb C9.1, washed once, and further incubated with anti-rat κ light-chain mAb, and then treated with rabbit complement as described in the Materials and Methods. Per cent inhibition was determined by the following formula [(lytic units of control assay – lytic units of test assay)/(lytic units of control assay)]×100.

Strain distribution of C9.1 antigen

NWNA spleen cells from various mouse strains were stained with FITC-labelled mAb C9.1 and assessed for the expression of NK1.1 and C9.1 antigens on FACScan. The 2B4 antigen which had been reported to have a strain distribution similar to NK1.1 was also included in this experiment. The results are summarized in Table 2. C9.1 antigen was expressed in all of the mice examined except for C57BL and C58 mice. NZB, SJL and YNA mice expressed both NK1.1 and C9.1 antigens but not 2B4. The 2B4 antigen was expressed only in C57BL/6 and C58 mice. Overall, it is evident from Table 2 that the strain distribution pattern of C9.1 antigen is antithetical to that of the 2B4 antigen.

Table 2.

Strain distribution of NK1.1, C9.1 and 2B4 antigens

*NWNA spleen cells from each strain of mice were stained with PE-labelled anti-NK1.1, FITC-labelled C9.1, or FITC-labelled 2B4.In some experiments staining with these mAb was performed on A-LAK cells as well.

C9.1 antigen is closely linked to the Akp1 isozyme locus on chromosome 1

The 2B4 gene is mapped on chromosome 1 close to the Fcγr3 gene for FcγRIII.18 To see whether the C9.1 gene is linked to 2B4, we next examined a correlation between C9.1 expression and AKP1 isozyme; the latter is encoded by a gene mapped on chromosome 1 close to the Fcγr3 gene (Table 3). Spleen cells from 50 individual F2 progenies of (C57BL/6×YNA) F1 mice were assessed for C9.1 expression by FACScan and for AKP1 isozyme by isoeletric focusing. This strain combination was chosen because C9.1− C57BL/6 mice carry the Akp1a allele and C9.1+ YNA mice carry the Akp1b allele. The results are summarized in Table 3. The Akp1 genotype of 13 C9.1− F2 progenies was a/a and that of 37 C9.1+ F2 progenies was a/b or b/b. No recombination between the Akp1 locus and the gene for C9.1 antigen was observed. This result indicates that the C9.1 gene was closely linked to the Akp1 locus. Because the Akp1 locus and the 2B4 gene are both mapped near the Fcγr3 gene, this result implies that the C9.1 gene is located on chromosome 1 near the 2B4 gene.

Table 3.

Correlation of C9.1 antigen expression and the Akp1 locus on chromosome 1*

*Spleen cells from individual 50 F2 progenies of (C57BL/6×YNA)F1 mice were assessed for the C9.1 expression on FACScan, and for AKP1 isozyme by isoelectric focusing. C9.1− C57BL/6 carries the Akp1a allele and C9.1+YNA carries the Akp1b allele.

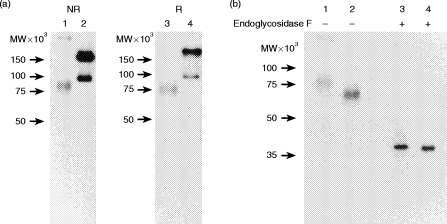

Biochemical characterization of C9.1 antigen

Membrane proteins of C3H/He A-LAK cells were radioiodinated, lysed in nonidet P-40 buffer, and subjected to immunoprecipitation with mAb C9.1 followed by SDS–PAGE analysis. A representative result of SDS–PAGE analyses of the immune complexes is presented in Fig. 4. As shown in Fig. 4(a) lanes 1 and 3, mAb C9.1 immunoprecipitated 78 000 MW molecules under both reducing and non-reducing conditions. Control immunoprecipitations using isotype-matched mAb against LFA-1 antigen were included on the same labelled membrane preparation (Fig. 4, lanes 2 and 4). Two bands corresponding to 180 000 and 95 000 MW were detected under both reducing and non-reducing conditions as had been expected. To compare with the 2B4 molecule, immunoprecipitation was also performed on radioiodinated A-LAK cells from (C57BL/6×C3H) F1 mice which expressed both C9.1 and 2B4. As shown in Fig. 4(b) lanes 1 and 2, mAb C9.1 and 2B4 immunoprecipitated different molecular masses of 78 000 and 66 000 MW, respectively. To determine whether carbohydrates are present on the antigens, the same labelled immune complexes were digested with endoglycosidase F and run on SDS–PAGE. It is evident from Fig. 4(b) lanes 3 and 4 that with removal of N-linked sugars both C9.1 and 2B4 molecules migrated as bands with an identical molecular weight 38 000. These results indicate that C9.1 is a 78 000 MW glycoprotein monomer and that the difference of molecular weights between C9.1 and 2B4 is due to differential glycosylation of the protein backbones with the same molecular weight.

Figure 4.

SDS–PAGE of 125I-labelled antigen recognized by mAb C9.1. (a) A-LAK cells derived from C3H/He mice were iodinated with Na125I by the lactoperoxidase method. 125I-labelled membrane proteins were incubated with mAb C9.1 (lanes 1 and 3) or mAb FD441.8 (anti-LFA-1) (lanes 2 and 4), followed by incubation with anti-rat IgG mAb-bound protein G–Sepharose 4B. The immune complexes were analysed under non-reducing (lanes 1 and 2) or reducing (lanes 3 and 4) conditions by SDS–PAGE on 7·5% gels and subjected to autoradiography. (b) A-LAK cells from (C57BL/6×C3H) F1 mice were radioiodinated and immunoprecipitated with mAb C9.1(lanes 1 and 3) or anti-2B4 mAb (lanes 2 and 4) as in (a). Immune complexes were treated with (lanes 3 and 4) or without (lanes 1 and 2) endoglycosidase F, analysed under reducing conditions by SDS–PAGE on 10% gels and subjected to autoradiography.

Effect of mAb C9.1 on NK-cell cytotoxic activity

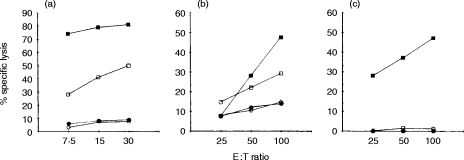

To determine whether the C9.1 molecule expressed on NK cells is functional, NK-cell-mediated antibody-redirected lysis against FcγR+ cells was examined (Fig. 5). We employed three different types of effector cells, i.e. A-LAK cells, polyI:C-activated NK cells and freshly isolated NK cells. These effector cells were cocultured for 4 hr with 51Cr-labelled FcγR+ Daudi cells in the presence of mAb C9.1 or an irrelevant isotype-matched control antibody H12, and specific killing was determined. As shown in Fig. 5(a,b), mAb C9.1 enhanced killing of FcγR+ Daudi cells by both A-LAK cells and polyI:C-activated NK cells. However, as shown in Fig. 5(c), mAb C9.1 failed to activate the lytic programme of freshly isolated NK cells. All of these effector cells efficiently killed NK-sensitive YAC-1 cells, and irrelevant isotype-matched control antibody H12 did not exert any effect on the killing of Daudi cells. Thus, the results indicate that C9.1 antigen is functionally active on in vitro IL-2-activated and in vivo polyI:C-activated NK cells but not on resting NK cells.

Figure 5.

mAb C9.1-induced, redirected cytotoxicity. A-LAK cells derived from C3H/He mice (a), spleen cells from C3H/He mice pretreated with polyI:C (polyI:C-activated NK cells) (b), or freshly isolated NK cells from normal C3H/He mice (c) were used as effector cells in standard 4-hr 51Cr-release assays against 51Cr-labelled FcγR+ Daudi target cells at the indicated ratios. Assays were performed in the presence of mAb C9.1 (□), or mAb H12 (◊), or in their absence (•). As a positive control, 51Cr-labelled YAC-1 cells were included in each assay as target cells (▪).

DISCUSSION

NK cells express on their surface neither the sIg receptor nor the TCR, but express a cluster of antigens such as NK1.1, Asialo-GM1, Qa antigens and 2B49,26. Of these, the NK1.1 antigen has been used as the most reliable NK cell surface marker among those surface antigens. However, its application remains limited due to the fact that the NK1.1 antigen, detected in C57BL/6 mice, are infrequently expressed among other inbred mouse strains.17,26 We have shown in this study that the antigen recognized by mAb C9.1 is expressed by all NK cells in most inbred mouse strains other than C57BL/6 and C58 mice. This finding may allow us to use C9.1 antigen as a useful cell surface marker for NK cells in NK1.1− mouse strains in combination with other cell surface markers.

In addition to NK1.1, C57BL NK cells express the 2B4 antigen that is associated with MHC-unrestricted cytotoxicity.9 It has been reported that the strain distribution of 2B4 antigen expression is similar to that of NK1.127. However, our data demonstrated that NZB, SJL and YNA mice express NK1.1 but not 2B4, indicating that the 2B4 antigen has not exactly the same strain distribution as that of NK1.1.

The 2B4 molecule is a 66 000 MW membrane glycoprotein of the immunoglobulin supergene family, encoded by a gene mapped on chromosome 1 in close proximity to the Fcγr3 gene for FcγRIII.18 The present results have shown that the strain distribution pattern of C9.1 expression on NK cells is antithetical to the strain distribution of the 2B4 antigen. Moreover, we have mapped the C9.1 gene on chromosome 1 close to the 2B4 gene on the basis of their close linkage to the Akp1 isozyme locus on chromosome 1. In addition, biochemical studies have revealed that the protein backbone encoded by the C9.1 gene has the same molecular weight as that of 2B4. Thus, we may conclude from these data that mAb C9.1 recognizes an allelic form of the 2B4 antigen. The fact that the anti-2B4 mAb27 was made by immunizing a C9.1+ 2B4− 129/Svj mouse strain with C9.1− 2B4+ C57BL/6 cells (Table 2) also supports this conclusion.

Our antibody-redirected assays have revealed that C9.1 antigen expressed on NK cells is not merely an allotypic marker but that it is functionally active on IL-2-cultured and in vivo polyI:C-activated NK cells. The fact that the C9.1 molecule did not function on freshly isolated NK cells indicates that the triggering function of the C9.1 molecule is associated only with activated NK cells. This observation is in agreement with the reported property of the 2B4 molecule, namely, that anti-2B4 mAb enhances killing only if the NK cells have been activated by IL-2.9 It has also been reported that anti-2B4 mAb enhances killing of FcγR− target cells as well.9 The mechanism underlying this FcγR-independent killing, however, is not known at present. We have observed in the present study that mAb C9.1 augments killing of FcγR− EL4 cells by A-LAK cells but not the killing by polyI:C-activated NK cells (data not shown). Accordingly, the antibody-mediated FcγR- independent killing appears to depend on the activation status of NK cells. Overall, these functional studies demonstrate that C9.1 antigen is functionally quite similar to the 2B4 antigen. This functional similarity corroborates our conclusion that C9.1 and 2B4 are allelic products of the same gene.

A new point that has emerged from our functional studies is that the triggering function of C9.1 is not limited to in vitro IL-2-activated NK cells but extends to in vivo polyI:C-activated NK cells. This finding for NK cells activated in vivo leads us to speculate that the C9.1 molecule may play an important physiological role after stimulation of the host innate immune system.

It should be noted, however, that there is a discrepancy between the tissue distributions of C9.1 and 2B4 antigens. Unlike 2B4, C9.1 is expressed on a minor subset of B cells and consequently the expression of the C9.1 antigen is not restricted to cells that can mediate MHC-unrestricted killing. The reason for this discrepancy is not readily elucidated at present. The key to this issue may lie in the fact that the 2B4 gene belongs to a family of closely related genes.18 Thus, mAb C9.1 may recognize not only an allelic form of the 2B4 antigen but also some product of the 2B4 family genes, the tissue distribution of which extends to a subset of B cells. Further molecular and functional studies of the C9.1 antigen expressed on a minor subset of B cells may shed light on the roles of the 2B4 family gene products in NK- and B-cell biology.

Glossary

- FcγR

receptors for Fc portion of IgG

- LAK

lymphokine-activated killer

- mAb

monoclonal antibody

- MHC

major histocompatibility complex

- NWNA

nylon wool non-adherent

- polyI:C

polyinosinic:polycytidylic acid

- sIg

surface immunoglobulin

- TCR

T-cell receptor

REFERENCES

- 1.Trinchieri G. Biology of natural killer cells. Adv Immunol. 1989;47:187. doi: 10.1016/S0065-2776(08)60664-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Biron CA. Activation and function of natural killer cell responses during viral infections. Curr Opin Immunol. 1997;9:24. doi: 10.1016/s0952-7915(97)80155-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bancroft GJ. The role of natural killer cells in innate resistance to infection. Curr Opin Immunol. 1993;5:503. doi: 10.1016/0952-7915(93)90030-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Murphy WJ, Kumar V, Bennet M. Rejection of bone marrow allografts by mice with severe combined immune deficiency (SCID). Evidence that natural killer cells can mediate the specificity of marrow graft rejection. J Exp Med. 1987;165:1212. doi: 10.1084/jem.165.4.1212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yokoyama WM, Seaman WE. The Ly-49 and NKR-P1 gene families encoding lectin-like receptors on natural killer cells. The NK gene complex. Annu Rev Immunol. 1993;11:613. doi: 10.1146/annurev.iy.11.040193.003145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Moretta A, Bottino C, Vitale M, et al. Receptors for HLA class-I molecules in human natural killer cells. Annu Rev Immunol. 1996;14:619. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.14.1.619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Siliciano RF, Pratt JC, Schmidt RE, Ritz J, Reinherz EL. Activation of cytolytic T lymphocyte and natural killer cell function through the T11 sheep erythrocyte binding protein. Nature. 1985;317:428. doi: 10.1038/317428a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Karhofer FM, Yokoyama WM. Stimulation of murine natural killer (NK) cells by a monoclonal antibody specific for the NK1.1 antigen. J Immunol. 1991;146:3662. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Garni-Wagner BA, Purohit A, Mathew PA, Bennett M, Kumar V. A novel function-associated molecule related to non-MHC-restricted cytotoxicity mediated by activated natural killer cells and T cells. J Immunol. 1993;151:60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Frey JL, Bino T, Kantor RR.S, et al. Mechanism of target cell recognition by natural killer cells: Characterization of a novel triggering molecule restricted to CD3− large granular lymphocytes. J Exp Med. 1991;174:1527. doi: 10.1084/jem.174.6.1527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sivori S, Vitale M, Morelli L, et al. p46, a novel natural killer-specific surface molecule that mediates cell activation. J Exp Med. 1997;186:1129. doi: 10.1084/jem.186.7.1129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Miyazaki T, Dierich A, Benoist C, Mathis D. Independent modes of natural killing distinguished in mice lacking Lag3. Science. 1996;272:405. doi: 10.1126/science.272.5260.405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Moretta A, Poggi A, Pende D, et al. CD69-mediated pathway of lymphocyte activation: anti-CD69 monoclonal antibodies trigger the cytolytic activity of different lymphoid effector cells with the exception of cytolytic T lymphocytes expressing T cell receptor α/β. J Exp Med. 1991;174:1393. doi: 10.1084/jem.174.6.1393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Carbone E, Ruggiero G, Terrazzano G, et al. A new mechanism of NK cell cytotoxicity activation: the CD40–CD40 ligand interaction. J Exp Med. 1997;185:2053. doi: 10.1084/jem.185.12.2053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hersey P, Bolhuis R. ‘Nonspecific’ MHC- unrestricted killer cells and their receptors. Immunol Today. 1987;8:233. doi: 10.1016/0167-5699(87)90173-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lanier LL, Corliss B, Phillips JH. Arousal and inhibition of human NK cells. Immunol Rev. 1997;155:145. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065x.1997.tb00947.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ryan JC, Truck J, Niemi EC, Yokoyama WM, Seaman WE. Molecular cloning of the NK1.1 antigen, a member of the NKR-P1 family of natural killer cell activation molecules. J Immunol. 1992;149:1631. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mathew PA, Garni-Wagner BA, Land K, et al. Cloning and characterization of the 2B4 gene encoding a molecule associated with non-MHC-restricted killing mediated by activated natural killer cells and T cells. J Immunol. 1993;151:5328. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schumachers G, Ariizumi K, Mathew PA, Bennett M, Kumar V, Takashima A. 2B4, a new member of the immunoglobulin gene superfamily, is expressed on murine dendritic epidermal T cells and plays a functional role in their killing of skin tumors. J Inv Dermatology. 1995;105:592. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12323533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kubota K, Nakazato K, Tamauchi H, Sasahara T, Katoh H. Generation of novel killer hybridomas derived from proliferation-suppressed hybrids between the YACUT T-cell lymphoma and normal lymphocytes activated in secondary mixed lymphocyte culture cells. J Immunol Methods. 1996;192:137. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(96)00030-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kubota K. A killer cell protective antigen expressed by MHC-unrestricted killer hybridomas. Cellular Immunol. 1997;181:50. doi: 10.1006/cimm.1997.1195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Holmes K, Fowlkes BJ, Schmid I, Giorgi JV. Preparation of cells and reagents for flow cytometry. In: Colligan JE, et al., editors. Current Protocols in Immunology. Vol. 1. New York: John Wiley & Sons; 1995. 5.3.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kubota K, Katoh H. Cessation of autonomous proliferation of mouse lymphoma EL4 by fusion with a T cell line. Int J Cancer. 1990;45:540. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910450328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Elder JH, Alexander S. endo-β-N-acetylglucosamidase F: endoglycosidase from Flavobacterium meningosepticum that cleaves both high-mannose and complex glycoproteins. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1982;79:4540. doi: 10.1073/pnas.79.15.4540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Coffman RL. Surface antigen expression and immunoglobulin gene rearrangement during mouse pre-B cell development. Immunol Rev. 1982;69:5. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065x.1983.tb00446.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Burton RC, Koo GC, Smart YC, Clark DA, Winn HJ. Surface antigens of murine natural killer cells. Int Rev Cytol. 1988;111:185. doi: 10.1016/s0074-7696(08)61734-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sentman CL, Hackett J, Moore TA, Tutt MM, Bennett M, Kumar V. Pan natural killer cell monoclonal antibodies and their relationship to the NK1.1 antigen. Hybridoma. 1989;8:605. doi: 10.1089/hyb.1989.8.605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ohteki T, MacDonald HR. Major histocompatibility complex class I related molecules control the development of CD4+8− and CD4− subsets of natural killer 1.1+ T cell receptor-α/β+ cells in the liver of mice. J Exp Med. 1994;180:699. doi: 10.1084/jem.180.2.699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]