Abstract

In this study we aimed to elucidate the physiological role of γδ intraepithelial lymphocytes (IEL) in the mouse intestine. For this purpose, we used T-cell receptor (TCR) Vγ4/Vδ5 transgenic mice (KN 6 Tg: BALB/c background, H-2d), and compared the immunological and physiological characteristics of the intestinal tracts of KN 6 Tg and non-transgenic (non-Tg) littermates. In KN 6 Tg littermates, ≈95% of small intestinal (SI) and large intestinal (LI) IEL expressed γδ TCR, and their TCR was replaced by Tg γδ TCR. In these mice, class II major histocompatibility complex (MHC) expression was up-regulated in the SI epithelium, compared with the non-Tg littermates, under specific pathogen-free (SPF) conditions. Competitive reverse transcription–polmerase chain reaction (RT–PCR) analysis showed that the mRNAs of the I-Eα chain on the SI epithelial cells was higher in KN 6 Tg than in non-Tg littermates. However, in the LI, class II MHC molecules were not expressed in either KN 6 Tg or non-Tg littermates. The epithelial cell mitotic index in the SI, but not in the LI, was higher in KN 6 Tg than in non-Tg littermates under SPF conditions. However, differentiation markers for SI epithelial cells, such as alkaline phosphatase and disaccharidase (lactase, maltase and sucrase) activities, were similar in KN 6 Tg and non-Tg littermates. MHC class II molecule expression on the SI epithelium was absent in germ-free (GF) Tg mice, but was induced under SPF conditions, coinciding with the increase of interferon-γ (IFN-γ) mRNA in γδ TCR SI-IEL. These findings suggest that γδ TCR IEL regulate epithelial cell regeneration and class II MHC expression, but not cell differentiation in the SI. However, these functions were not observed in the γδ TCR IEL in the LI. In addition, the activation step in the γδ TCR SI-IEL is dependent on the presence of gut microflora.

INTRODUCTION

Two distinct T-lymphocyte subsets, expressing the αβ and γδ T-cell receptors (TCR), exist in the intraepithelial space in various organs. In particular, the existence of the γδ TCR subsets is mainly restricted to the intraepithelial space, such as in the small and large intestine, epidermis and urogenital tract.1,2 The origins, fates or functions of these intraepithelial lymphocytes (IEL) remain unknown. In the case of αβ TCR-expressing small intestinal (SI)-IEL, the number and redirected cytolytic activity (CTL) are low in the germ-free (GF) state, and these phenotypes of αβ TCR SI-IEL gradually increase after inoculation of faecal microorganisms derived from SPF mice into GF mice (conventionalization).3,4 This suggested that the proliferation and activation of αβ TCR SI-IEL is dependent on the gut flora. In contrast to the αβ TCR SI-IEL, the number of γδ TCR SI-IEL did not change during the conventionalization of GF mice.5 Thus, the proliferation of γδ TCR SI-IEL is independent of the gut microflora. However, we recently found that γδ TCR-expressing SI-IEL regulate class II major histocompatibility complex (MHC) molecule expression during the conventionalization of GF mice.5 Therefore, the proliferation or activation of γδ TCR SI-IEL may be regulated in a distinct manner.

KN 6 TCR (Vγ4/Vδ5) transgenic mice (KN 6 Tg mice) have been established by Professor S. Tonegawa.6,7 The KN 6 γδ TCR has been reported to recognize a novel MHC TL region gene (TL22b) product.8 These genes are widely distributed in various strains of mice (e.g. C57BL/6), but are lacking in BALB/c and B10 mice.8 In this study, we compared the immunological and physiological characteristics of SI and large intestinal (LI) epithelial cells from KN 6 Tg mice with those from non-Tg littermates. In addition, we examined the effects of enteric bacteria on the immunological and physiological characteristics of these transgenic mice.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals

TCR Vγ4/Vδ5 transgenic mice (KN 6 Tg: BALB/c background, H-2d) were kindly provided by Professor S. Tonegawa (Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Boston, MA). The mice were bred under specific pathogen-free (SPF) conditions in the animal facilities of our institute. The GF KN 6 mice were made by our institute and colonies of the GF KN 6 Tg strain were maintained in a sterile vinyl-isolator. The GF state was checked monthly by a previously recommended method.9

Flow cytometric analysis of intestinal MHC antigens

The cell-surface expression of MHC molecules on SI epithelial cells was examined by the method described previously.5 Briefly, segments of small intestine were incubated in Hanks’ balanced saline solution (HBSS; Gibco, Grand Island, NY) containing 0.45 mm dithiothreitol, 0.25 mm EDTA and 0.1 m HEPES, pH 7.0, three times, for 15 min each, at 37°. The released cells were collected by centrifugation. The pellets were resuspended in HBSS, containing 1% fetal calf serum (FCS), and then passed through a cotton column (60 mg/tube). The cells were stored at 4° before staining. Biotinylated mouse monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) AMS-32.1, AMS-16 (PharMingen, San Diego, CA) and 050-16B (Meiji Institute of Health Science, Tokyo, Japan), specific for mouse H-2 products I-Ad, I-Ed,k,p,r and TL antigen (TLA)a,c,d, respectively, were used in this experiment. Cells (2.0×105) were incubated with each mAb for 20 min at 4° and then washed with HBSS. The cells were then incubated with avidin– phycoerythrin (Becton-Dickinson, Mountain View, CA) for 20 min at 4°. The cells were washed with HBSS and then analysed with an Epics Elite flow cytometer (Coulter Electronics Co., Hialeah, FL). Epithelial cell populations were separated by ‘gating’ using forward scatter and right scatter, as previously described.9,10

Preparation and flow cytometric analysis of SI- and LI-IEL

SI- and LI-IEL were isolated as described elsewhere.4 The collected SI- and LI-IEL were stained with the following mAbs: anti-γδ TCR-fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC) (GL3), anti-Vγ4-biotin (UC3-10A6), anti-αβ TCR-biotin (H57-597), anti-L3T4-biotin (GK1.5), anti-Lyt2-phycoerythrin (53-6.7) and anti-Lyt3-FITC (53-5.8) (all purchased from PharMingen). The stained cells were analysed with an Epics Elite flow cytometer (Coulter Electronics Co.).

Magnetic-activated-cell-sorting (MACS) separation of γδ TCR SI-IEL

SI-IEL were isolated from GF and SPF KN 6 Tg mice (n = 3–4). Pooled SI-IEL (5–8 × 106) were stained with biotinylated anti-γδ TCR mAb (GL3) for 15 min at 4°. Then the cells were incubated with avidin-magnetic-microbeads and avidin-cychrome (PharMingen) for 15 min at 4°. Finally, the cells were applied to a MACS separation column (Miltenyi Biotec, Bergisch Gladbach, Germany). After several washes of the column with ice-cold HBSS, the column was removed from the magnetic field and the positive fraction collected. The purity of the γδ TCR-positive SI-IEL was >95%.

lmmunohistochemistry

Freshly isolated distal parts of SI or LI segments were mounted in Tissue Mount (Shiraimatsu Kikai Co., Ltd, Saitama, Japan) at −80° and stored at −80° until analysis. They were then sectioned using a cryostat (Bright Co., Ltd, Cambridgeshire, UK). Immunohristochemical staining of MHC molecules was carried out as described previously.11 In brief, tissue sections were fixed with ice-cold acetone at −20° for 10 min. After several washes with 10 mm phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), 5 mg/ml biotinylated mAb against murine 1-Ad: AMS-32.1 was applied at room temperature for 90 min. After several washes with 10 mm PBS, horseradish peroxidase-conjugated streptavidin was applied to the slides, followed by colour development using 3,3-diamino-benzidine tetrahydrochloride (Sigma, Co., St. Louis, MO).

Competitive reverse transcriptase–polymerase chain reaction (RT–PCR) analysis by non-homologous internal standard (MIMIC) cDNA constructs

Quantitative RT–PCR analysis for I-Eα chain mRNA was performed by competitive PCR by using stepwise dilutions of non-homologous internal standard MIMICs (PCR MIMIC Construction Kit: Clontech, Palo Alto, CA). To construct the PCR MIMIC, two rounds of PCR amplification were performed. The first PCR primers were as follows. Sense primer: 5′-GGC TCC TTG TCG GCG TTC TAA TTT GAT TCT GGA CCA TGG C-3′ and antisense primer: 5′-CCA GAA GTC ATG GGC TAT CAC AAG TTT CGT GAG CTG ATT G-3′. Each primer had the target I-Eα gene primer sequence attached to a 20-nucleotide sequence designed to hybridize to opposite strands of a MIMIC DNA fragment. A dilution of the first PCR products was then amplified with I-Eα gene-specific gene primers as described previously.12 The PCR MIMIC construct was purified by passage through CHORMA SPIN + TE-100 (Clontech). PCR MIMIC was then diluted to 100 attomol/μl. cDNA derived from 1 μg total RNA isolated from the SI epithelial cell fractions of either KN 6 Tg-or non-Tg mice was amplified in the presence of twofold serial dilutions of the I-Eα MIMIC. I-Eα-specific PCR products were quantified using the BIO-PROFIL image analyser (Vilber Loumat Co., Ltd, Marne La Vallée, France) by comparison with PCR products obtained from MIMIC.

Evaluation of the activities of disaccharidases and alkaline phosphatase

SI epithelial cells released following EDTA treatment were washed twice with ice-cold saline and then homogenized for use as the enzyme source. The activities of lactase, maltase, sucrase and alkaline phosphatase (AP), in the epithelial cell homogenate derived from KN 6 Tg or non-Tg mice, were determined as described previously.13,14 Enzyme activity was expressed as μmol hydrolyzed/mg protein/min.

Determination of mitotic activity (MA)

Epithelial MA was determined by the metaphase-arrest method.15 Vincristine sulphate (1 mg/kg: Sigma) was injected intraperitoneally 90 min or 180 min before the mice were killed. Segments of the SI (jejunum) and LI (distal colon) were washed with ice-cold 10 mm PBS and then fixed with Carnoy fixative. After several washes with ice-cold 10 mm PBS, the intestinal segments were stained according to the Feulgen reaction. Microdissection of the intestinal crypts was performed under a stereomicroscope and the number of metaphase nuclei was determined in 50 dissected crypts. MA was expressed as the cell number in the metaphase per crypt.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis of the results of each experiment was performed using the two-tailed Student’s t-test.

RESULTS

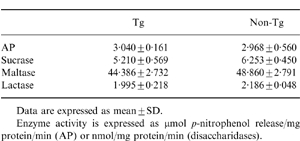

Flow cytometric analysis of SI-IEL in KN 6, Tg and non-Tg littermates

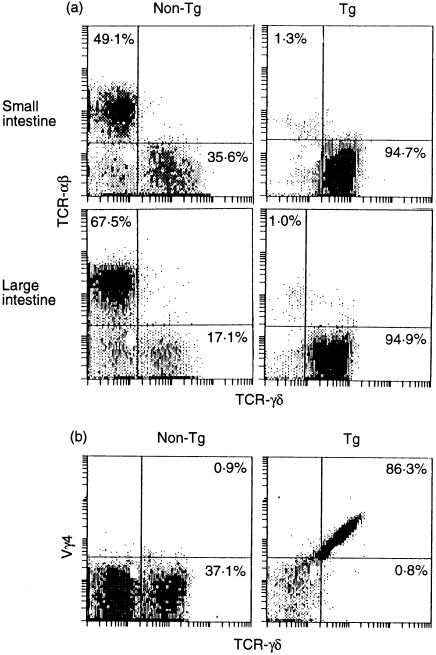

Approximately 95% of IEL in the SI and LI expressed γδ TCR in KN 6 Tg mice, and almost all expressed transgenic TCR (Fig. 1a, 1b).

Figure 1.

(a) Flow cytometric analysis of intraepithelial lymphocytes (IEL), in the small intestine (SI) and large intestine (LI), for T-cell receptors (TCR) γδ and αβ from KN 6 Tg and non-Tg littermates. (b) Transgenic TCR (Vy4) expression of SI-IEL in KN 6 Tg mice and non-Tg littermates.

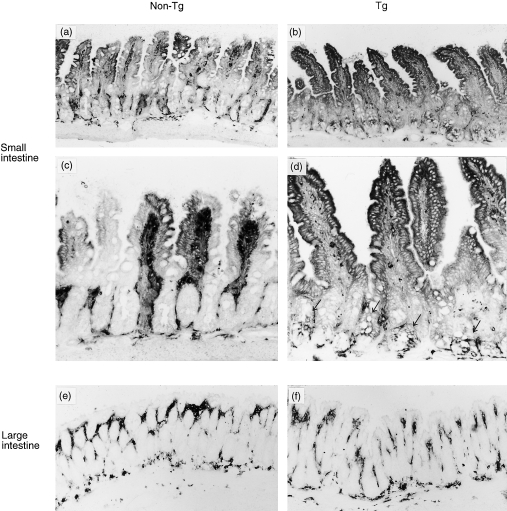

Class II MHC molecule expression in KN 6 Tg mice

Immunohistochernical analysis showed that the expression of class II MHC molecules in control non-Tg littermates was restricted to the upper villus epithelium, i.e. class II MHC molecules were not expressed in the crypt epithelial cells (Fig. 2b). In contrast to those of non-Tg littermates, both the villus and crypt epithelial cells expressed class II MHC, and the staining intensity was greater in KN 6 Tg mice than in non-Tg littermates (Fig. 2a). Class II MHC molecules were not expressed on the colonic epithelial cells in either KN 6 Tg mice or non-Tg littermates (Fig. 2c, 2d).

Figure 2.

lmmunohistological analysis of major histocompatibility complex (MHC) molecules on the intestinal epithelium of KN 6 Tg mice. Results are shown of immunohistochemical staining of class II MHC molecules on the small (a–d) and large (e and f) intestine in KN 6 Tg (b, d, f) and non-Tg (a, c, e) littermates. Snap-frozen sections were stained with monoclonal antibody (mAb) AMS-32.1 as described in the Materials and methods. Staining of class II MHC on small intestinal (SI) epithelial cells was greater in KN 6 Tg mice than in non-Tg littermates (a–d). In contrast to non-Tg mice, the expression of class II MHC was detected on the crypt epithelial cells in Tg littermates (d, arrow). No staining of the large intestinal (LI) epithelium was observed in either KN 6 Tg or non-Tg mice (c, d). Original magnification: ×100 (a, b, e, f), ×200 (c, d).

Next we quantified the cell-surface expression of class II MHC molecules on SI epithelial cells, derived from KN 6 Tg mice and non-Tg littermates, by flow cytometry. In the non-transgenic littermates, ≈50% of the epithelial cells carried positively stained class II MHC molecules (Fig. 3). However, the expression of class II MHC was high in KN 6 Tg mice (85%). The expression of TLA was similar in KN 6 Tg mice and non-Tg littermates (Fig. 3).

Figure 3.

Flow cytometric analysis of the epithelial major histocompatibility complex (MHC) antigen on small intestinal (SI) epithelial cells in KN 6 Tg and non-Tg mice. Isolated epithelial cells were stained with biotinylated anti-I-Ad monoclonal antibody (mAb) AMS 32.1 or anti-TLA mAb 050-16B. Controls were incubated with biotinylated non-immune mouse IgG.

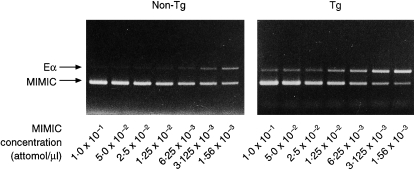

RT–PCR analysis of class II MHC-related mRNAs

Next we analysed mRNA expression of the I-Eα chain on SI epithelial cells derived from KN 6 Tg mice and non-Tg littermates by competitive RT–PCR, as described in the Materials and methods. A higher amount of the PCR products of the I-Eα chain was found in KN 6 Tg mice than in non-Tg littermates (Fig. 4). By estimation of the number of I-Eα mRNA molecules, the number of I-Eα chain mRNA molecules in the SI epithelial cells derived from KN 6 Tg and non-Tg mice were 2015±227 molecules/μg RNA and 894±231 molecules/μg RNA, respectively (P < 0.05). These results are comparable with those of the above immunohistological analysis of class II MHC expression.

Figure 4.

Competitive reverse transcription–polymerase chain reaction (RT–PCR) analysis of I-Eα chain mRNA expression in small intestinal (SI) epithelial cells derived from KN 6 Tg mice and non-Tg littermates was performed as described in the Materials and methods. An approximate twofold increase in I-Eα chain mRNA transcripts was detected in KN 6 Tg mice, as compared with those of non-Tg mice.

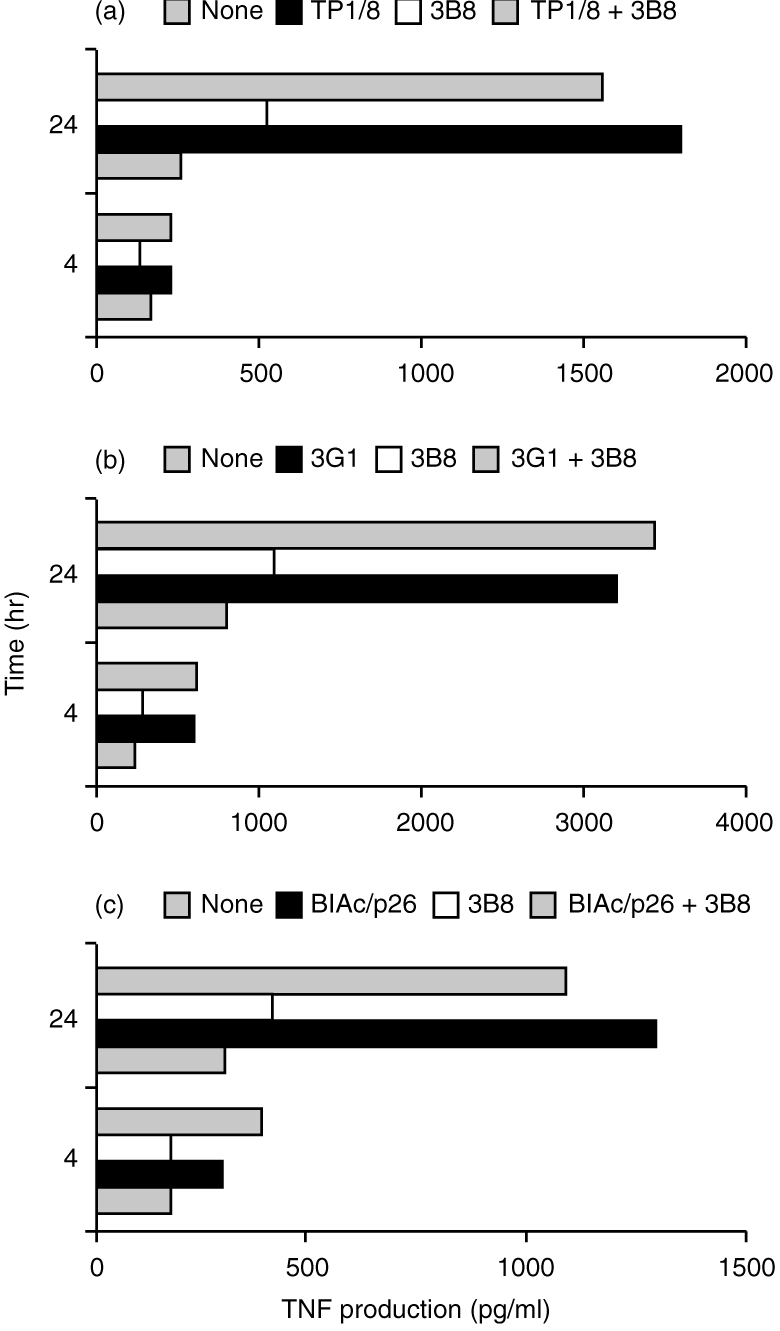

Determination of epithelial MA

The MA of intestinal crypt epithelial cells from the SI (jejunum) and LI (colon) was determined in both KN 6 Tg and non-Tg littermates by the metaphase-arrest technique. Epithelial MA was higher in the KN 6 Tg mice than in the non-Tg littermates in the SI, both at 90 and 180 min after injection of vincristine sulphate (Fig. 5). However, in the LI, MA was similar in KN 6 Tg mice and non-Tg littermates both at 90 and 180 min after the vincristine sulphate injection (Fig. 5).

Figure 5.

Epithelial mitotic activity (MA) activity in KN 6 Tg mice. Epithelial MA of the small intestine (jejunum) or large intestine (distal colon) was determined by the method described in the Materials and methods. In the small intestine, the number of cells in metaphase was higher in KN 6 Tg mice than in non-Tg littermates at 90 min or 180 min after vincristine sulphate injection. However, in the large intestine, the numbers of these cells were comparable in KN 6 Tg mice and non-Tg littermates. There were three mice per group. The data are expressed as mean±SD. **Values are significantly (P <0.01) different from non-Tg littermates. The data represent the averages of three independent experiments.

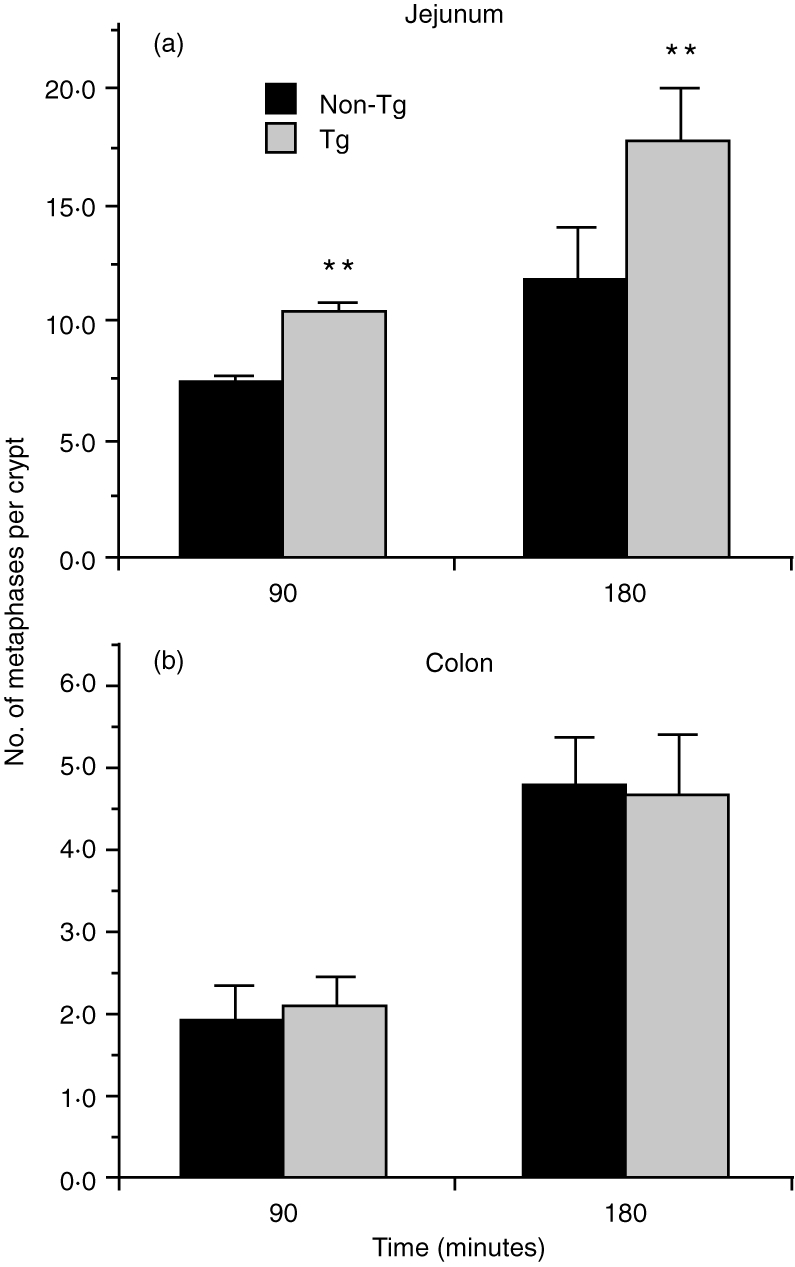

Analysis of disaccharidase and AP activities on SI epithelial cells

We then examined whether or not γδ TCR SI-IEL influences the differentiation of SI epithelial cells. Analysis of the enzyme activities of AP and disaccharidases (such as lactase, maltase and sucrase) was performed as these are well-known functional differentiation markers of SI epithelial cells. The enzyme activities of such differentiation markers were similar both in KN 6 Tg mice and non-Tg littermates (Table 1). On immunohistological analysis, the expression of these molecules on SI epithelial cells was comparable in KN 6 Tg mice and non-Tg littermates (data not shown).

Table 1.

Alkaline phosphatase (AP) and disaccharidase activities in KN 6 Tg mice

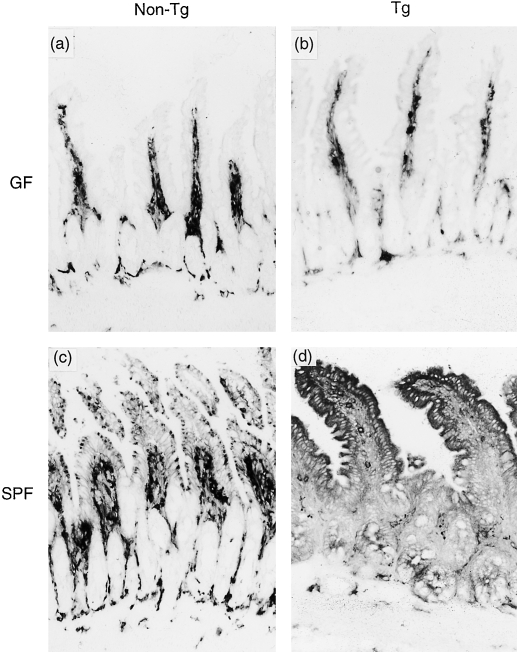

Class II MHC molecule expression in GF KN 6 Tg mice

We have already described that the expression of class II MHC on SI epithelial cells is dependent on microbial colonization of the gut.11 To address the effect of the gut flora on induction of class II MHC molecules in KN 6 Tg mice, we compared the expression of class II MHC, immunohistochemically, in the SI between GF and SPF KN 6 Tg mice. In control non-Tg littermates, class II MHC was absent in the GF state and induced on the SI epithelium under SPF conditions, as described in our previous study11 (Fig. 6b, 6d). Expression of class II MHC on the SI epithelium could not be detected in GF KN 6 Tg littermates, as also observed in GF non-Tg littermates, but was induced in the SI epithelium in SPF KN 6 Tg mice (Fig. 6a, 6c). There were many class II-positive cells in the lamina propria in both GF and SPF KN 6 Tg mice and non-Tg littermates (Fig. 6a–d).

Figure 6.

Class II major histocompatibility complex (MHC) molecule expression in germ-free (GF) KN 6 Tg mice. Expression of class II MHC on small intestinal (SI) epithelial cells in KN 6 Tg (b, d) and non-Tg littermates (a, c) reared under GF (a, b) or specific pathogen-free (SPF) (c, d) conditions. Ileal tissue sections were cut using a cryostat and stained with monoclonal antibody (mAb) AMS-32.1, as described in the Materials and methods. Original magnification: ×200.

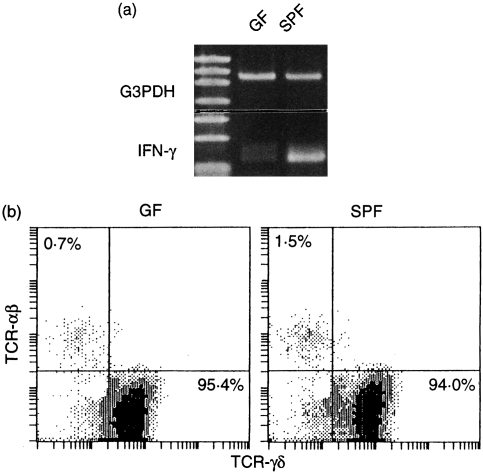

Expression of interferon-γ (IFN-γ) mRNA by γδ TCR SI-IEL in GF and SPF KN 6 Tg mice

RT–PCR analysis showed that the level of IFN-γ mRNA in MACS-separated γδ TCR SI-IEL in KN 6 Tg mice was very low in the GF state, but increased markedly under SPF conditions (Fig. 7a). However, the αβ/γδ TCR ratio in SI-IEL was comparable in GF and SPF KN 6 Tg mice (Fig. 7b). There was no significant difference in the total cell number of γδ TCR SI-IEL in either GF or SPF KN 6 Tg mice (data not shown).

Figure 7.

Reverse transcription–polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) analysis of interferon-γ (IFN-γ) mRNA in γδ T-cell receptor (TCR) small intestine-intraepithelial lymphocytes (SI-IEL) in germ-free (GF) and specific pathogen-free (SPF) KN 6 Tg mice. (a) The levels of IFN-γ mRNA in MACS-separated γδ TCR SI-IEL from GF and SPF KN 6 Tg mice were determined by RT–PCR analysis as described in the Materials and methods. (b) γδ/αβ TCR expression in SI-IEL isolated from GF or SPF KN 6 Tg mice. The isolated SI-IEL were stained with fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-conjugated GL3 and phycoerythrin (PE)-conjugated H57-597. Cytofluorescence analysis was performed with an Epics Elite cell analyser.

DISCUSSION

In this study, to determine the physiological role of γδ TCR IEL in the intestinal epithelium, we used TCR Vγ4/Vδ5 transgenic mice (KN 6 Tg, H-2d) and compared the immunological and physiological characteristics of the intestinal tracts of KN 6 Tg mice with those of non-Tg littermates. In KN 6 γδ TCR transgenic mice, the SI- and LI-IEL consisted of >95%γδ TCR (almost all were transgenic γδ TCR), which showed up-regulation of expression of class II MHC and MA in SI epithelial cells but not in LI epithelial cells under SPF conditions. It is well known that up-regulation of class II MHC expression and MA in intestinal epithelial cells appears at the onset of an intestinal inflammatory disease.16 However, in this study, the activities of marker enzymes for epithelial cell differentiation in the SI, such as disaccharidases and AP, were similar both in KN 6 Tg mice and non-Tg littermates. Moreover, the up-regulation of class II MHC expression and MA was not observed in colonic epithelial cells. Therefore, the changes in the epithelial cell characteristics in the SI in these transgenic mice are likely to be a physiological response, not an inflammatory or pathological response.

We have already described that class II MHC in SI epithelial cells is absent in GF BALB/c mice and is induced by the introduction of faecal bacteria derived fom SPF BALB/c mice.11 However, class I MHC molecules, such as H-2Kd and TLA products, were expressed in the SI in the GF state, and their expression was not affected by microbial colonization.11 Therefore, we analysed class II MHC molecule expression on SI epithelial cells, and IFN-γ mRNA expression in γδ TCR SI-IEL, in both GF and SPF KN 6 Tg littermates. The results were clear-cut. Expression of class II MHC on the SI epithelial cells was absent in GF KN 6 Tg mice and induced in SPF KN 6 Tg littermates. The level of IFN-γ mRNA in γδ TCR SI-IEL was very low in GF KN 6 Tg mice and high in SPF KN 6 Tg littermates. We have already reported that the induction of class II MHC at an early stage (≈7 days after conventionalization) of microbial colonization was inhibited by the repeated administration of a neutralizing mAb against IFN-γ or the depletion of γδ TCR SI-IEL.5 Cerf-Bensussan et al. suggested that culture supernatant from concanavalin A (Con A)- or phytohaemagglutinin (PHA)-stimulated rat IEL-induced Ia antigen on rat IEL-17 cell lines.17 Other work, and a study previously carried out by us, have both shown that the cytolytic activity and the absolute number of γδ TCR SI-IEL are similar in GF and SPF mice.3,4 In the case of αβ TCR SI-IEL, cellularity and cytolytic activity are very low in the GF state, but gradually increase after conventionalization.3 These results suggest that the maturation step differs between γδ TCR SI-IEL and αβ TCR SI-IEL. Moreover, the maturation step of γδ TCR SI-IEL does not depend on the presence of the gut flora; however, the activation step of γδ TCR SI-IEL does depend on the presence of the gut flora. To support this concept, we have revealed that the in vivo incorporation of BrdU in γδ TCR SI-IEL showed a marked increase during the conventionalization of GF BALB/c mice.18

It has been reported that the KN 6 γδ TCR recognizes the novel MHC TL-region gene (TL22b) product that is present in C57BL/6 (H-2b) mice. However, this gene product was absent in BALB/c (H-2d) mice.8 Therefore, KN 6 γδ TCR hybridomas proliferated well in response to antigen-presenting cells (APC) of C57BL/6 but not of BALB/c origin.8 However, we showed in this study that there was a marked difference in the levels of IFN-γ mRNA from γδ TCR SI-IEL between GF and SPF KN 6 Tg littermates. This suggests that γδ TCR SI-IEL in these Tg mice are activated independently of the TL22b gene product. If so, it would be of interest to determine the kind of stimuli, produced by bacterial colonization, that influence the activation of γδ TCR SI-IEL. Tsuji et al. showed that a murine γδ T-cell clone proliferated strongly in response to lipopolysaccharide (LPS), in the presence of irradiated spleen cells derived from the syngeneic or MHC mismatched strain.19 Moreover, several cytokines, such as interleukin (IL)-7 and IL-15, were shown to preferentially cause the proliferation and activation of γδ TCR SI-IEL.20*sref20* A separate study of ours indicated that the mRNA of IL-7 is low in the epithelial cells of GF mice, but gradually increases after conventionalization of the GF mice (S. Matsumoto, manuscript in preparation). It is possible that activation of γδ TCR SI-IEL may occur in a MHC non-restricted manner, and that certain factors, such as cytokines, of epithelial cell origin may activate γδ TCR SI-IEL through stimulation resulting from bacterial colonization.

It should also be of interest to identify the kind of intestinal bacteria that evoke this phenomenon. We have already described that activation of intestinal SI-IEL and induction of class II MHC occurred following oral contamination with indigenous, vegetative intestinal flora.15 In particular, monoassociation of segmented filamentous bacteria (SFB) in GF BALB/c mice modulated this phenomenon.21,22 They were localized in the lumen of the distal part of the SI and adhered strongly to the epithelial cells of the SI.23 Klassen et al. showed that monoassociation with SFB in GF mice increased the number of IgA-producing B cells in the small intestine.24 We have also reported that the cell surface glycolipid antigen on the small intestine changed markedly after colonization by SFBs.21 Taken together, it is likely that the factor responsible for the activation of γδ TCR SI-IEL may be induced on SI epithelial cells following colonization with SFB. Further analysis of SFB monoassociated KN 6 Tg mice is required to clarify this hypothesis. In conclusion, intraepithelial γδ SI-IEL regulate epithelial cell regeneration and class II MHC expression, but not epithelial cell differentiation, in the SI. However, these functions were not observed in the γδ TCR IEL in the LI. In addition, activation, but not proliferation, of the γδ TCR SI-IEL required the presence of gut microflora. KN 6 Tg mice should be a simple model for clarification of the mechanism underlying the activation of γδ TCR SI-IEL in the SI.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank Dr T. Osawa for critical reading of the manuscript, and Dr A. Imaoka (Yakult Central Institute) for advice on experimental procedures. The expert technical assistance of H. Setoyama is also gratefully acknowledged.

REFERENCES

- 1.Koning F, Stingl G, Yokoyama WM, et al. Identification of a T3-associated γδ T-cell receptor on Thy-1+ dendric epidermal cell lines. Science. 1987;236:834. doi: 10.1126/science.2883729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Itohara S, Nakanishi N, Kanagawa O, Kubo R, Tonegawa S. Monoclonal antibodies specific to native murine T-cell receptor γδ: analysis of γδ T cells in thymic ontogeny and in peripheral lymphoid organ. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1989;86:5094. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.13.5094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kawaguchi M, Nanno M, Umesaki Y, et al. Cytolytic activity of intestinal intraepithelial lymphocytes in germ-free mice is strain dependent and determined by T cells expressing γδ T-cell antigen receptors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:8591. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.18.8591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Umesaki Y, Setoyama H, Matsumoto S, Okada Y. Expansion of αβ T-cell receptor intestinal intraepithelial lymphocytes after microbial colonization in germ-free mice and its independence from thymus. Immunology. 1993;79:32. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Matsumoto S, Setoyama H, Imaoka A, et al. γδ TCR-bearing intraepithelial lymphocytes regulate class II major histocompatibility complex molecule expression on mouse small intestinal epithelium. Epithel Cell Biol. 1995;4:163. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bonneville M, Janeway CA, Jr, Ito K, et al. Intestinal intraepithelial lymphocytes are a distinct set of γδ T cells. Nature. 1988;336:479. doi: 10.1038/336479a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Itohara S, Farr AG, Lafaille JJ, et al. Homing of a γδ thymocyte subset with homogeneous T-cell receptors to mucosal epithelia. Nature. 1990;343:754. doi: 10.1038/343754a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ito K, Kear LV, Bonneville M, Hsu S, Murphy DB, Tonegawa S. Recognition of the product of a novel MHC TL region gene (27b) by mouse γδ T cell receptor. Cell. 1990;62:549. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90019-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Japan Experimental Animal Research Association. Recommended requirement for sterility test of germfree animals, provisional. Exp Anim. 1972;21:35. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hershberg R, Eghtesady P, Sydora B, et al. Expression of the thymus leukemia antigen in mouse intestinal epithelium. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1990;87:9727. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.24.9727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Matsumoto S, Setoyama H, Umesaki Y. Differential induction of major histocompatibility complex molecules on mouse intestine by bacterial colonization. Gastroenterology. 1992;103:1777. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(92)91434-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chang CH, Fontes JD, Perterlin M, Flavell RA. Class II transactivator (CIITA) is sufficient for the inducible expression of major histocompatibility complex class II gene. J Immunol. 1994;132:2244. doi: 10.1084/jem.180.4.1367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Umesaki Y, Tohyama K, Mutai M. Biosynthesis of microvillus membrane-associated glycoproteins of the small intestinal epithelial cells in germ-free and conventionalized mice. J Biochem. 1982;92:373. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a133943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Umesaki Y. lmmunohistochemical and biochemical demonstration of the change in glycolipid composition of the intestinal epithelial cell surface in mice in relation to epithelial cell differentiation and bacterial association. J Histochem Cytochem. 1984;32:299. doi: 10.1177/32.3.6693758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Okada Y, Setoyama H, Matsumoto S, et al. Effects of fecal microorganisms and their chloroform-resistant variants derived from mice, rats, and humans on immunological and physiological characteristics of the intestines of ex germfree mice. Infect Immun. 1994;62:5442. doi: 10.1128/iai.62.12.5442-5446.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sadlack B, Merz H, Schorle H, Schimpi A, Feller AC, Horak I. Ulcerative colitis-like disease in mice with a disrupted interleukin-2 gene. Cell. 1993;75:253. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)80067-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cerf-Bensussan N, Quaroni A, Kurnick JT, Bhan AK. Intraepithelial lymphocytes modulate Ia expression by intestinal epithelial cells. J Immunol. 1984;132:2244. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Imaoka A, Matsumoto S, Setoyama H, Okada Y, Umesaki Y. Proliferative recruitment of intestinal intraepithelial lymphocytes after microbial colonization of germ-free mice. Eur J Immunol. 1996;26:945. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830260434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tsuji M, Eyster CL, O’Brien RL, et al. Phenotypic and functional properties of murine γδ T cell clones derived from malaria immunized, αβ T cell-deficient mice. Int Immumol. 8:359. doi: 10.1093/intimm/8.3.359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Inagaki-Ohara K, Nishimura H, Mitani A, Yoshikai Y. Interleukin-15 preferentially promotes the growth of intestinal intraepithelial lymphocytes bearing γδ T cell receptor in mice. Eur J Immunol. 1997;27:2885. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830271121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Umesaki Y, Okada Y, Matsumoto S, Imaoka A, Setoyama H. Segmented filamentous bacteria that activate intraepithelial lymphocytes and induce MHC class II molecules and fucosyl asialo GM1 glycolipids on the small intestinal epithelial cells in the ex-germ-free mouse. Microbiol Immunol. 1995;39:555. doi: 10.1111/j.1348-0421.1995.tb02242.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Umesaki Y, Okada Y, Imaoka A, Setoyama H, Matsumoto S. Interactions between epithelial cells and bacteria, normal and pathogenic. Science. 1997;276:946. doi: 10.1126/science.276.5314.964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Klaasen HL.B.M, Koopman JP, Poelma FG.J, Beynen AC. Intestinal, segmented, filamentous bacteria. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 1992;88:165. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1992.tb04986.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Klaasen HL.B.M, Van der Heijden PJ, Stock W, et al. Apathogenic, intestinal, segmented, filamentous bacteria stimulate the mucosal immune system of mice. Infect Immun. 1993;61:303. doi: 10.1128/iai.61.1.303-306.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]