Abstract

The C-terminal 19 000 MW fragment of merozoite surface protein-1 (MSP119) is one of the most promising candidate antigens for a malaria vaccine. Baculovirus recombinant Plasmodium falciparum MSP119 has been used to define conditions for the in vitro production of specific antibodies by purified human blood B cells in a culture system where T-cell signals were provided by the engagement of CD40 molecules and exogenous cytokines. MSP119 preferentially induced surface immunoglobulin G (IgG) -positive (sγ+) B lymphocytes from P. falciparum-immune donors to differentiate and produce antigen-specific IgG. In contrast, naïve B cells or cells from non-immune donors could not be induced to secrete parasite-specific IgG in vitro. Although IgG secretion was obtained in the absence of exogenous cytokines, it was dependent on B-cell-derived interleukin-10 (IL-10) and/or B-cell factor(s) under the control of IL-10, since IgG levels were significantly decreased in the presence of neutralizing anti-IL-10 antibodies. These results demonstrate at the cellular level that a single malaria vaccine candidate polypeptide can direct parasite-specific antibody production mediated by the secretion of potentiating factors.

INTRODUCTION

The C-terminal 19 000 MW fragment of merozoite surface protein 1 (MSP119) has been recognized as a target of protective immune effectors, and represents a prime candidate for a blood-stage vaccine to Plasmodium falciparum.1 Immunity to P. falciparum blood-stage antigens, and in particular to MSP1, has been correlated with the presence of immunoglobulin G (IgG) antibodies,2–4 whose specific production and regulation are poorly understood.

In a previous report, we showed that purified B lymphocytes from P. falciparum-immune non-human primates could secrete IgG antibodies in vitro upon restimulation with crude parasite extracts. This work described culture conditions favouring the production of IgG antibodies, which involved cognate T-cell interaction and the addition of certain exogenous cytokines.5

To examine the direct effect(s) of specific parasite antigens on B lymphocytes from human donors immune to P. falciparum, we developed an in vitro assay which is based on B-cell stimulation with baculovirus recombinant MSP119 antigen, anti-CD40 monoclonal antibody (mAb) and exogenous cytokines.6,7 The mechanisms which may play a role in antibody-based immunity involving this antigen have been investigated by comparing purified blood B-cell fractions from P. falciparum-immune and non-immune individuals and by determining the conditions necessary for terminal differentiation and secretion of antigen-specific IgG antibodies in vitro.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Blood sampling

Blood donors were adult Senegalese villagers over 25 years of age, living in malaria-endemic areas, who reported no symptoms of clinical malaria for at least six months preceding this study (despite active malaria transmission with 100–200 infective mosquito bites per individual per year8), and European expatriates with no history of malaria. Blood (30 ml) was collected during the dry season, when malaria transmission is low, with the informed consent of volunteer donors under the guidance of the ad hoc ethics committee. No Plasmodium spp. were detected in any individual tested by means of the Quantitative Buffy Coat® (QBC®) test (Becton Dickinson/H2F, Abijan, Ivory Coast).

Cell preparations

B cells were recovered from peripheral blood monocytes by means of positive selection with CD19 (clone AB1)-coated magnetic beads (Dynabeads®; Dynal, Lake Success, NY), as previously described.7 CD19+ B lymphocytes included predifferentiated B cells expressing surface IgG (sγ+ cells) and cells without surface IgG (sγ− cells) comprised mainly surface IgM+/IgD+ naïve B cells and rare surface IgA+, IgM+/IgD− or IgE+ B cells. Total CD19-selected B-cell populations are referred to as sγ+/sγ− B cells. The sγ− B cells were obtained by negative selection after incubation of the CD19+ B-cell population (106 cells/ml for 1 hr at 4°) with 5 μg/ml of mouse mAb anti-human IgG (Cappel/Organon Technica, Turnhout, Belgium) followed by two cycles of incubation with magnetic goat anti-mouse antibody-coated beads (Dynabeads®). Previous studies have shown that B cells are not activated by this procedure.9 Purification (>98%) was assessed by cytofluorometry using conjugated anti-CD19 (clone J4-119) mAb or relevant control antibodies (Immunotech, Marseille, France).

Recombinant P. falciparum parasite protein

The recombinant P. falciparum protein used in this study was the C-terminal 19 000 MW fragment of the merozoite surface protein-1 (MSP119), obtained in the baculovirus/insect cell expression system as previously described,10,11 and purified by immunoaffinity chromatography using the G17 mAb (I. Holm, F. Nato and S. Longacre, unpublished data). The recent determination of the crystal structure of a similar baculovirus MSP119 preparation indicates that this antigen is highly purified and that its characteristic epidermal growth factor (EGF)-like domains are correctly folded (V. Chitarra, I. Holm, G. Bentley and S. Longacre, unpublished data). A mock baculovirus/insect cell culture was used to control for MSP119 specificity where relevant.

In vitro culture of B lymphocytes

CD19+ B cells were adjusted to 106 cells/ml, and cultured in 48-well plates (Falcon; Becton-Dickinson, Franklin Lakes, NJ), at a final volume of 0·5 ml of Iscove’s Dulbecco’s modified medium (Sigma, St Louis, MO) with 10% fetal calf serum (Hyclone, Logan, UT), and supplemented as previously described,7 with or without antigen, mitogenic anti-CD40 mAb (clone ‘89’; 10 μg/ml; a gift from Dr J. Banchereau, Schering-Plough, Dardilly, France), and human recombinant cytokines: interleukin-2 (IL-2; a gift from Sanofi, Labège, France); IL-10 (a gift from Dr F. Brière, Schering-Plough, Dardilly, France); IL-6 (a gift from Dr F. Montero-Julian, Immunotech, Marseille, France); IL-1β (Peprotech, London, UK); and IL-4, obtained from Chinese hamster ovary-transfected cell cultures (a gift from Dr T. B. Nutman, National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, Bethesda, MD). Some cultures were done in the presence of cholera toxin (CT; Sigma), or of neutralizing rabbit polyclonal antibodies to human IL-6, IL-10 and tumour necrosis factor-α (TNF-α; Peprotech). Cells were cultured at 37° in the presence of 5% CO2. Supernatants were collected at day 10 and were frozen until assayed for antibody production.

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) analysis of total and antigen-specific IgG

To determine total IgG, Immulon-4 plates (Dynatech, Springfield, VA) were coated with a mouse mAb to human IgG (1 μg/ml; Immunotech) as described.6 Culture supernatants were diluted as appropriate, and incubated overnight (4°). Peroxidase-conjugated, polyclonal goat anti-human IgG (1/10 000) was used as a secondary reagent and applied for 1 hr at 37° (Cappel). The peroxidase substrate was Orthotolidine/H2O2 (Sigma).

Parasite-specific IgG antibodies were detected in plasma from immune donors (diluted 1/200) and in culture supernatants of MSP119-stimulated B cells using either recombinant MSP119 or a crude preparation of P. falciparum-infected red blood cells enriched for merozoites prepared as described.12 These extracts are known to contain MSP119 since they react with anti-MSP119 polyclonal and monoclonal antibodies (R. Perraut et al. manuscript in preparation). A lysate of non-infected erythrocytes in culture medium was used as the control. MaxiSorp plates (Nunc, Roskilde, Denmark) were coated overnight at 4° with 2 μg/ml of merozoite extract or various concentrations of recombinant MSP119.13 Supernatants from each culture were incubated for 2 hr at 37° and then overnight at 4° and subsequent steps were performed as described above. Results are expressed as OD values, read at 450 nm in a Titertek Multiscan (Flow Laboratories, Asnières, France). Optical density (OD) ratios (from duplicate determinations) were calculated for each experimental culture versus appropriate control cultures.6

Statistical analysis

Data were expressed as means±SD. Statistical analysis was done by means of the Mann–Whitney test for non-normally distributed data.

RESULTS

Human B lymphocytes from P. falciparum-immune individuals produce IgG in vitro upon restimulation with MSP119, anti-CD40 antibody and exogenous cytokines

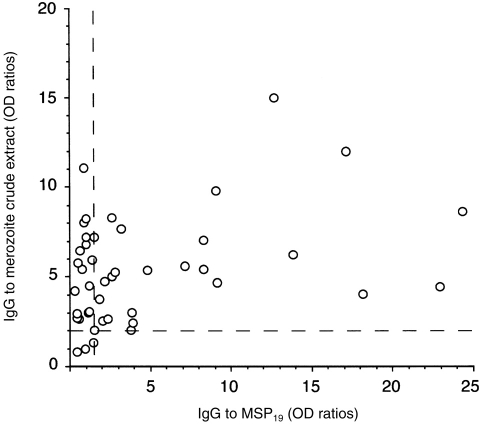

B lymphocytes obtained from P. falciparum-immune and non-immune donors were stimulated in the presence or absence of MSP119 with anti-CD40 mAb and various concentrations and combinations of IL-2, IL-4 and IL-10. Both total and parasite-specific IgG were optimally induced in the presence of either IL-4 (100 IU/ml) or IL-10 (100 IU/ml) and 0·1 μg/ml MSP119 (data not shown). Individual cultures were tested for total IgG, MSP119-specific IgG, and IgG reactive to a parasite extract enriched for merozoites. For reasons that may be related to the efficiency and steric properties of antigen binding to microtitre plates, antibody reactivity with the crude parasite extracts, but not recombinant MSP119, was consistently detected (data not shown). Thus, the parasite extract data were used to measure parasite-specific antibodies. Indeed, since serum antibodies from P. falciparum-immune individuals most frequently reacted with both MSP119 and the parasite extract (Fig. 1), the latter was used to detect anti-MSP119 antibody in B-cell culture supernatants.

Figure 1.

Antibodies from P. falciparum-immune plasma react both with recombinant MSP119 and crude parasite antigen. Plasma from 45 P. falciparum-immune individuals were screened for IgG antibodies to MSP119 (x axis) and a crude extract of P. falciparum segmented schizonts ( y axis). ELISA OD values were plotted for each individual. Dotted lines represent threshold for positivities as defined in ref. 13 (crude parasite extract, OD ratio ≥2; recombinant MSP1, OD ratio ≥1·5).

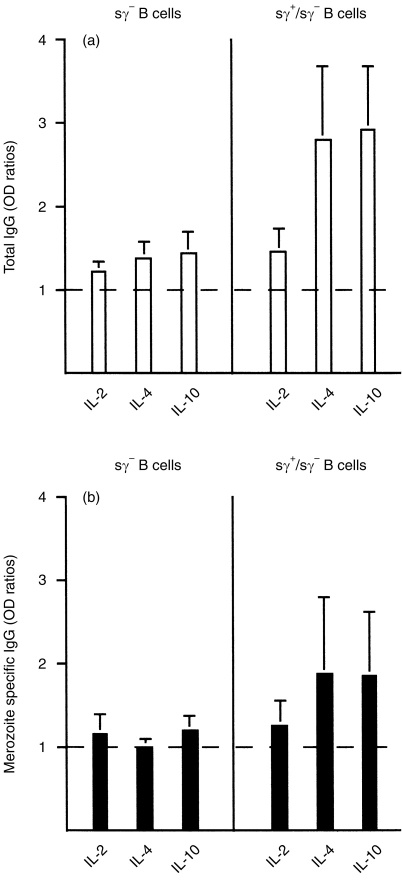

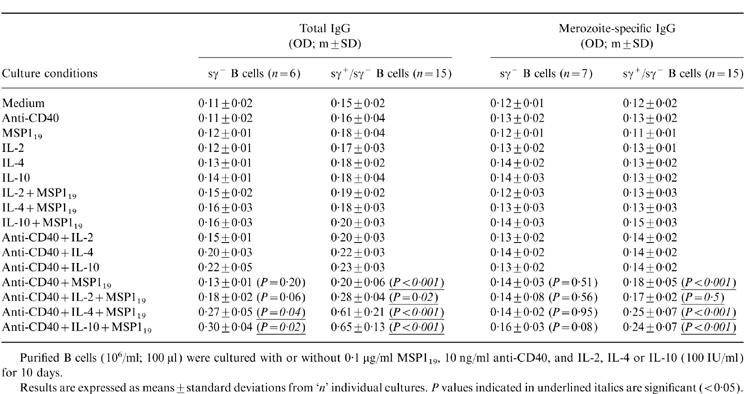

Table 1 shows that peripheral blood B cells (sγ+/sγ−) obtained from P. falciparum-immune individuals could produce limited amounts of total IgG, but not parasite-specific IgG, when stimulated with anti-CD40 and IL-4, IL-10, or IL-2 in the absence of antigen. Total IgG could also be produced in the presence of anti-CD40 and MSP119 in the absence of exogenous cytokines. However, the production of parasite-specific IgG required antigen costimulation in the presence of anti-CD40 and IL-4 or IL-10, but not IL-2, even at high concentrations (data not shown). Under these culture conditions, specific IgG could not be significantly enhanced by the addition of IL-6, IL-1β, or cholera toxin (data not shown).

Table 1.

The effect of MSP119 on peripheral B-cell populations from P. falciparum-immune individuals upon various conditions of costimulation in vitro

Purified B cells (106/ml; 100 μl) were cultured with or without 0·1 μg/ml MSPl19, 10 ng/ml anti-CD40, and IL-2, IL-4 or IL-10 (100 IU/ml) for 10 days.

Results are expressed as means ±standard deviations from 'n' individual cultures. P values indicated in underlined italics are significant (< 0·05).

To determine which B-cell population(s) were being differentiated to secrete IgG antibodies in response to MSP119 and anti-CD40 stimulation, we cultured both total (sγ+/sγ−) or sγ+-depleted (sγ−) B cells. Table 1 shows that sγ− B cells cultured in the presence of anti-CD40, IL-4, or IL-10, and MSP119 could produce modest, but statistically significant (P < 0·05), amounts of total IgG, but not parasite-specific IgG. Figure 2 gives a relatively quantitative indication of the effects observed and shows that IL-2 has only a modest effect on the total IgG production (Fig. 2a), in striking contrast to IL-4 and IL-10 (Fig. 2b).

Figure 2.

Cytokine-dependent in vitro secretion by immune blood B lymphocytes of total IgG (a) and parasite-specific IgG (b). The means±SD of ‘n’ (Table 1) individual cultures are shown. Both sγ+/sγ− and sγ− B-cell populations were cultured with or without MSP119 in the presence of anti-CD40 mAb and cytokines as indicated. Antibody levels are indicated as the ratios of OD values from a given set of culture conditions with or without MSP119 (see the Materials and Methods). The dotted line indicates negative or background values (OD ratio = 1).

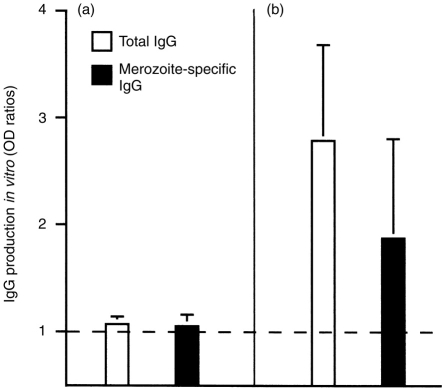

The effect of MSP119 on B lymphocytes from non-immune individuals was examined with total blood B cells stimulated with anti-CD40 mAb, MSP119 and IL-4 (Fig. 3a) or IL-10 (not shown). Under these conditions, no IgG production could be detected, in contrast to the cultures derived from immune individuals (Fig. 3b).

Figure 3.

MSP119 stimulates peripheral B lymphocytes only from P. falciparum-immune individuals to secrete IgG antibodies. (a) Non-immune donors, (b) P. falciparum-immune donors; the means±SD derived from six (a) or seven (b) different individuals are shown. Open histograms represent the total IgG production and filled histograms represent the parasite-specific IgG production. Antibody production levels are indicated as OD ratios. The dotted line indicates negative or background values (OD ratio = 1).

Individuals from endemic areas have serum IgG antibodies directed against many blood-stage antigens, although these reactivities appear to be variable [ref. 12; R. Perraut et al. submitted]. Thus the stimulatory effect of MSP119 on B cells from a different cohort of P. falciparum-immune individuals, with or without detectable MSP119-specific IgG, was examined. There was no significant difference in the capacity of anti-CD40 and MSP119-stimulated B cells to produce parasite-specific IgG with either IL-4 (data not shown) or IL-10; in the presence of IL-10, IgG production (mean OD ratios±SD) by B cells from MSP1-seronegative (n = 6) and MSP1-seropositive individuals (n = 6) was 1·7±0·25 and 1·6±0·6, respectively. This suggests that the absence of specific plasma IgG to this antigen is not owing to B cells which are refractory to immune stimulation, at least in vitro.

Antigen-specific IgG production in vitro is differentially regulated by B-cell-derived and exogenous cytokines

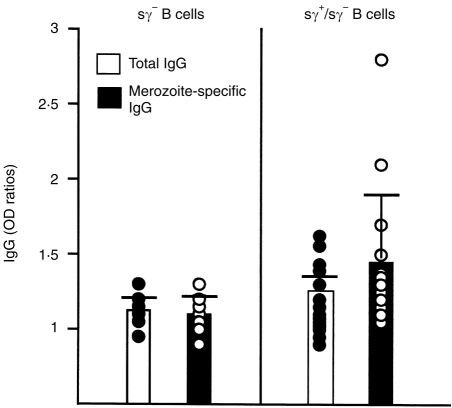

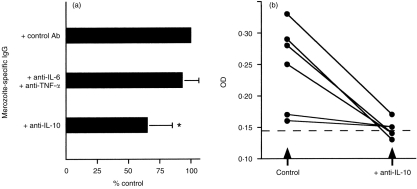

Anti-CD40 and MSP119-stimulated immune B lymphocytes could differentiate and produce total and parasite-specific IgG in the absence of exogenous cytokines (Table 1). Figure 4 shows that in this cohort, B cells from four of 15 individuals were driven to total and specific antibody production when stimulated with anti-CD40 and antigen alone. To determine if endogenous cytokines produced by MSP119-activated B cells could be at least partly responsible for such antibody production, total blood B cells from another cohort of six donors were cultured with antigen, anti-CD40 and IL-4, in the presence of neutralizing antibodies to known B-cell-derived cytokines such as IL-6, IL-10 and TNF-α known to affect antibody production in other related culture systems.7 The addition of neutralizing antibodies to IL-10 induced a significant (P = 0·007) reduction of parasite-specific IgG production (Fig. 5a). In contrast, neutralizing antibodies to IL-6 and TNF-α did not significantly reduce specific IgG production under similar culture conditions (Fig. 5a), or in the presence of IL-10 (data not shown). Indeed, as seen in Fig. 5(b), anti-IL-10 antibodies induced a dramatic decrease in parasite-specific IgG in the four individual cultures that produced significant amounts of antibodies.

Figure 4.

IgG secretion by total (sγ+/sγ−) blood B cells from P. falciparum-immune individuals is increased by exposition to MSP119 in the absence of exogenous cytokines. Histograms represent the means±SD of cultures derived from seven individuals (sγ− B cells) and 15 individuals (sγ+/sγ− B cells). Dots represent single cultures in each group. Open histograms and filled symbols represent total IgG production, and filled histograms and open symbols represent parasite-specific IgG. Antibody levels are indicated as OD ratios.

Figure 5.

Anti-IL-10 reduces parasite-specific IgG secretion by P. falciparum-immune B lymphocytes stimulated with MSP119 and IL-4. (a) Parasite-specific IgG secretion in cultures derived from five donors in the presence of 5 μg/ml of neutralizing IL-6 and TNF-α, or IL-10 antibodies is expressed as the mean percentage of rabbit control antibody (mean OD±SD). The asterisk indicates a statistically significant difference between cultures with and without neutralizing antibody. (b) Parasite-specific IgG, expressed as ELISA OD values, from cultures with neutralizing anti-IL-10 or control rabbit antibody.

DISCUSSION

Protection against blood-stage malaria infection is associated with specific IgG antibodies which can bind cellular effectors capable of mediating parasite clearance.14 However, there is no experimental evidence that any given blood-stage P. falciparum antigen, including MSP119, can alone direct an antibody-based response.15,16

The present work examines in vitro the human B-cell response to this important P. falciparum candidate vaccine antigen.1 The system used here involves IgG secretion by purified blood B-lymphocyte subsets exposed to a well-defined baculovirus recombinant MSP119 and costimulated with anti-CD40 and exogenous cytokines to provide T-cell help.17 The effects of IL-4 and IL-10 were of particular interest since they have been shown to sustain a high rate of IgG production in the presence of anti-CD40 mAb, unlike IL-2.18,19 CD40 and IL-4 signalling induce B cells to secrete large amounts of IgG, IgM and IgE18 and are capable of inducing naïve B cells to undergo switching.20 IL-10 can also promote the expansion of naïve and preswitched B lymphocytes21 and it is hypothesized to induce sγ− B cells to undergo either μ to γ1 or μ to γ3 switching leading to the production of IgG1 or IgG3.22

We show here that anti-CD40 and exogenous IL-4 or IL-10 can stimulate the terminal differentiation of a fraction of sγ+ B lymphocytes from P. falciparum-immune donors leading to the production of both total and antigen-reactive IgG when B cells were cultured in the presence of MSP119. Interestingly, this process was not potentiated by cholera toxin, IL-2, or IL-6 plus IL-1β as might have been expected from other experimental data.5,23–25 MSP119 could also induce anti-CD40-stimulated naive sγ− B cells from immune donors to produce moderate levels of IgG in the presence of either IL-4, or IL-10. However, the specificity of these antibodies could not be determined, possibly due to the low amounts produced.

It was surprising that the IgG induced by MSP119 did not bind the recombinant MSP119 on ELISA plates, in contrast to crude parasite proteins. However, two observations suggest that the MSP119-stimulated antibody response is essentially specific. First, antibodies produced by B cells from P. falciparum-immune donors polyclonally stimulated with anti-μ-coated beads and IL-2, were consistently unable to bind parasite extracts, even though these blood donors very likely had circulating sγ+ memory B lymphocytes specific for blood-stage antigens.26 Secondly, B cells from non-immune donors were consistently unable to produce detectable anti-blood-stage antibodies (Fig. 3). Thus, MSP119 must have induced committed B lymphocytes from immune donors to produce specific IgG. While it is very likely that the recombinant MSP119 is properly folded (see the Materials and Methods), it is possible that the reactive MSP119 epitopes are not equally accessible when presented alone or in the context of the parasite extract on microtitre plates.

Recent reports have shown that memory, but not naïve, blood B lymphocytes can polyclonally differentiate into immunoglobulin-secreting cells after stimulation with CD40 or other signalling molecules in the presence of IL-4 and/or IL-10.27,28 In general, however, the specific selection of memory or naïve B cells is likely to be dependent on the nature of the costimulus, such as that provided by a defined antigen.7 We have shown here that sγ+ blood B cells from immune donors were preferentially activated compared to sγ− (naïve) cells, and that the specific production of IgG is attributable to such terminally differentiated cells. Thus MSP119 binding to surface IgG receptors must elicit activation signals which permit anti-CD40-stimulated B cells to secrete appropriate antibodies in the absence of exogenous cytokines. Endogenous cytokines originating from the activated B cells may provide the necessary complementary signals.29,30 The results presented here suggest that the endogenous secretion of IL-10 and/or molecules under the control of IL-10, was necessary for the optimal production of parasite-specific IgG. We have previously shown that certain parasite antigens could induce B lymphocytes to produce cytokines and other regulatory molecules which participate in terminal differentiation to immunoglobulin-secreting cells.7,19

These results demonstrate for the first time that a single P. falciparum merozoite surface protein can promote a B-cell response at the cellular level, leading to parasite-specific antibody production and the probable secretion of factors which potentiate such antibody production. It is likely that the stimulatory activity of recombinant MSP119 in this context is related to immunological memory of this parasite protein rather than to an intrinsic effect, for example, its EGF domains. It will be of interest to determine if other P. falciparum blood-stage antigens can stimulate the production of antibodies by sensitized B lymphocytes in vitro using these or similar culture conditions. In particular, it would be important to determine if the antibodies produced under these conditions are functional, an issue to be tested if and when in vitro assays of protective efficacy become commonly available.30

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs A. Tall, J. F. Trape, C. Rogier, A. Ly, F. Diene Sarr (Institut Pasteur and ORSTOM, Dakar) for providing us with blood samples and relevant information; Drs T. O. Diallo and I. Dramé for serological data; Drs G. Milon, J. C. Mazié (Institut Pasteur, Paris); S. Mahanty (CDC, Atlanta); and T. B. Nutman (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD), for useful suggestions and critical reading of the manuscript. The technical help of G. Aribot, MM. J. Faye, M. Fall, A. Thiam and B. Diouf is also gratefully acknowledged.

REFERENCES

- 1.Holder AA, Riley EM. Human immune responses to MSP1. Parasitol Today. 1996;12:173. doi: 10.1016/0169-4758(96)20009-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Egan AF, Morris J, Barnish G, et al. Clinical immunity to Plasmodium falciparum malaria is associated with serum antibodies to three 19 kDa-terminal fragment of the merozoite surface antigen, PfMSP-1. J Infect Dis. 1996;173:765. doi: 10.1093/infdis/173.3.765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Al-Yaman F, Genton B, Kramer KJ, et al. Assessment of the role of naturally acquired antibody levels to Plasmodium falciparum merozoite surface protein-1 in protecting Papua New Guinean children from malaria morbidity. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1996;54:443. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1996.54.443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Guevara Patiño JA, Holder AA, McBride JS, Blackman MJ. Antibodies that inhibit malaria merozoite surface protein-1 processing and erythrocyte invasion are blocked by naturally acquired human antibodies. J Exp Med. 1997;186:1689. doi: 10.1084/jem.186.10.1689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Garraud O, Perraut R, Blanchard D, et al. Squirrel monkey (Saimiri sciureus) B lymphocytes: secretion of IgG directed to Plasmodium falciparum antigen, by primed blood B lymphocytes restimulated in vitro with parasitized red blood cells. Res Immunol. 1993;144:407. doi: 10.1016/0923-2494(93)80124-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Garraud O, Nkenfou C, Bradley JE, Perler FB, Nutman TB. Identification of recombinant filarial proteins capable of inducing polyclonal and antigen-specific IgE and IgG4 antibodies. J Immunol. 1995;155:1316. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Garraud O, Nkenfou C, Bradley JE, Nutman TB. Differential regulation of antigen-specific IgG4 and IgE antibodies in response to recombinant filarial proteins. Int Immunol. 1996;8:1841. doi: 10.1093/intimm/8.12.1841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Trape J-F, Rogier C, Konate L, et al. The Dielmo project: a longitudinal study of natural malaria infection and the mechanisms of protective immunity in a community living in a holoendemic area of Senegal. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1994;51:123. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1994.51.123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Funderund S, Erikstein B, Asheim HC, et al. Functional properties of CD19+ B lymphocytes positively selected from buffy coats by immunomagnetic separation. Eur J Immunol. 1990;20:201. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830200129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Longacre S, Mendis K, David PH. Plasmodium vivax merozoite surface protein-1 C-terminal recombinant proteins in baculovirus. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1994;64:191. doi: 10.1016/0166-6851(94)00002-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Holm I, Nato F, Mendis KN, Longacre S. Characterization of C-terminal merozoite surface protein-1 baculovirus recombinant proteins from Plasmodium vivax and Plasmodium cynomolgi as recognized by the natural anti-parasite immune response. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1997;89:313. doi: 10.1016/s0166-6851(97)00128-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dieye A, Heidrich HG, Rogier C, et al. Lymphocyte response in vitro to Plasmodium falciparum merozoite antigens in donors from a holoendemic area. Parasitol Res. 1993;79:629. doi: 10.1007/BF00932503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nguer CM, Diallo TO, Diouf A, et al. Plasmodium falciparum- and merozoite surface protein 1-specific antibody isotype balance in Senegalese immune adults. Infect Immun. 1997;65:3271. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.11.4873-4876.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Druilhe P, Sabchaeron A, Bouharoun-Tayoun H, Oeuvray C, Perignon J-L. In vivo veritas: lessons from immunoglobulin-transfer experiments in malaria patients. Ann Trop Med Parasitol. 1997;91:S37. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Allen JE, Maizels RM. Th1-Th2: reliable paradigm or dangerous dogma? Immunol Today. 1997;18:387. doi: 10.1016/s0167-5699(97)01102-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ferrante A, Rzepczyk CM. Atypical IgG antibody response to Plasmodium falciparum asexual stage antigens. Parasitol Today. 1997;13:145. doi: 10.1016/s0169-4758(97)89812-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Banchereau J, Rousset F. Growing human B lymphocytes in the CD40 system. Nature. 1991;353:678. doi: 10.1038/353678a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Banchereau J, Rousset F. Human B lymphocytes: phenotype, proliferation, and differentiation. Adv Immunol. 1992;52:125. doi: 10.1016/s0065-2776(08)60876-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Garraud O, Nutman TB. The role of cytokines in human B-cell differentiation into immunoglobulin secreting cells. Bull Inst Pasteur. 1996;94:285. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rothman P. Interleukin 4 targeting of immunoglobulin heavy chain class-switch recombination. Res Immunol. 1993;144:579. doi: 10.1016/s0923-2494(05)80006-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rousset F, Garcia E, Defrance T, et al. IL-10 is a potent growth and differentiation factor for activated B lymphocytes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:1890. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.5.1890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Brière F, Servet-Delprat C, Bridon J-M, Saint-Rémy J-M, Banchereau J. Human interleukin-10 induced naive surface immunoglobulin D+ (sIgD) B cells to secrete IgG1 and IgG3. J Exp Med. 1994;179:757. doi: 10.1084/jem.179.2.757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fluckiger A-C, Garronne P, Durand I, Galizzi JP, Banchereau J. IL-10 upregulates functional high affinity IL-2 receptors on normal and leukaemic blood B cells. J Exp Med. 1993;178:1473. doi: 10.1084/jem.178.5.1473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lycke NY. Cholera toxin promotes B cell isotype switching by two different mechanisms. J Immunol. 1993;150:4810. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Burdin N, Van Kooten C, Galibert L, et al. Endogenous IL-6 and IL-10 contribute to the differentiation of CD40-activated human B lymphocytes. J Immunol. 1995;154:2533. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Migot F, Chougnet C, Henzel D, et al. Anti-malaria antibody-producing B cell frequencies in adults after a Plasmodium falciparum outbreak in Madagascar. Clin Exp Immunol. 1995;102:529. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.1995.tb03848.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kindler V, Zubler RH. Memory, but not naive, peripheral blood B lymphocytes differentiate into Ig-secreting cells after CD40 ligation and costimulation with IL-4 and the differentiation factors IL-2, IL-10, and IL-3. J Immunol. 1997;159:2085. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Agematsu K, Nagumo H, Oguchi Y, et al. Generation of plasma cells from peripheral blood memory B cells: synergistic effect of interleukin-10 and CD27/CD70 interaction. Blood. 1998;91:173. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Abbas AK, Burstein HJ, Bogen SA. Determinants of helper T cell-dependent antibody production. Sem Immunol. 1993;5:441. doi: 10.1006/smim.1993.1050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Miller LH, Good MF, Kaslow DC. The need for assays predictive of protection in the development of malaria blood stage vaccine. Parasitol Today. 1997;13:46. doi: 10.1016/s0169-4758(96)20063-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]