Abstract

Virulent classical swine fever (CSF) represents an immunomodulatory viral infection that perturbs immune functions. Circulatory and immunopathological disorders include leukopenia, immunosuppression and haemorrhage. Monocytic cells – targets for CSF virus (CSFV) infection – could play critical roles in the immunopathology, owing to their production of immunomodulatory and vasoactive factors. Monocytes and macrophages (Mφ) are susceptible to virus infection, as a consequence of which prostaglandin E2 (PGE2) production is enhanced. The presence of PGE2 in serum from CSFV-infected pigs correlated with elevated PGE2 productivity by the peripheral blood mononuclear cells from these same animals. It was noted that these PGE2-containing preparations did not inhibit, but actually enhanced, lymphocyte proliferation. The proinflammatory cytokines tumour necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) and interleukin (IL)-6 were not involved, although elevated IL-1 production could relate to lymphocyte activation. Nevertheless, IL-1 was not the sole element: infected Mφ produced lympho-stimulatory activity but little IL-1. This release of immunomodulatory factors, following CSFV infection of monocytic cells, was compared with other characteristics of the disease. Therein, PGE2 and IL-1 production was noted to coincide with the onset of fever and the coagulation disorders typical of CSF. Consequently, these factors are of greater relevance to the haemorrhagic disturbances, such as petechia and infarction, rather than the leukopenia found in CSF.

INTRODUCTION

Monocytes and macrophages (Mφ) play essential roles in both innate immune defences and initiation of specific immune responses. Perturbation of these capacities can impede or even reverse the efficiency of such processes, as can be seen with immunmodulatory virus infections. One such infection is that caused by classical swine fever virus (CSFV), a member of the Flaviviridae, related to hepatitis C and dengue viruses. Pathognomonic alterations during CSF are dominated by the haemorrhagic syndrome and immunosuppression.1 The former includes petechial bleeding of the skin, mucosae and internal organs, as well as spleen infarction. Immunosuppression is characterized by lymphocyte depletion and depressed T-cell activity,1–4 as well as regressive changes in lymphoid organs2,5 and the bone marrow.6

CSFV is particularly useful for studying immunomodulatory infections owing to its non-cytopathic nature.7 It is the indirect induction of apoptosis in uninfected cells that has been identified as a mechanism behind the lymphopenia.4 The first and main targets for CSFV-infection are monocytic cells.1,2 These become widely dispersed,5 suggesting that they play an important role in CSF pathogenesis. Alteration of monocytic cell function through infection could influence both the vascular and immune systems, especially considering the association of apoptosis and lymphopenia with uninfected cells.4 Monocytes/Mφ are major sources of prostaglandin E2 (PGE2), an arachadonic acid metabolite with profound physiological effects at low concentrations.8 PGE2 participates in the mediation of inflammatory responses, production of pain and fever, induction of vascular dilatation and permeability, and initiation of blood clotting. With certain viruses, PGE2 induction has been associated with immunosuppression,9–11 although other cytokines released by monocytic cells have been implicated in inflammatory responses and immunomodulation.12

Consequently, in vitro infection of monocytic cells by CSFV was employed to investigate the characteristics of haemorrhage and immunosuppression development associated with infection with an immunomodulatory virus. The aim was to analyse how such an infection would be capable of modulating the target cells and interfering with their physiological function, with reference to the immunopathology of the disease.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Virus

CSFV strain Brescia (H. -J. Thiel, Giessen, Germany) was propagated in the porcine kidney cell line SK-6 (M. Pensaert, Gent, Belgium).13 Infection was at a multiplicity of infection (m.o.i.) of 0·001 tissue culture infective dose 50% (TCID50)/cell. After 72 hr, intracellular virus was released by sonication, the resulting lysate being clarified by centrifugation at 3000 g for 20 min. Mock controls were prepared in the same way, but without infection. UV-inactivated mock and virus controls were obtained by exposing the lysates to a 40-W UV lamp, at a distance of 5 cm, for 20 min. Inactivation was controlled by titration on SK-6 cells. Virus titres were also determined by end-point titration on SK-6 cells, infected cells being detected using monoclonal antibody (mAb) HC/TC26 (Dr Bommeli, AG, Berne, Switzerland) against CSFV glycoprotein (gp) E2,14 after fixing/permeabilizing the cells in ethanol for 10 min at −20°. The titres were calculated according to Kaerber.15

Leucocyte preparations

Citrated blood was obtained from specific pathogen-free (SPF) pigs. Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) were isolated over Ficoll–Paque (1·077 g/l; Pharmacia, Upsala, Sweden) density centrifugation.16 Monocytes were enriched by adherence (2 hr at 39°) in phenol red-free Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s minimal essential medium (DMEM) (Life Technologies, Basel, Switzerland) containing 10% (vol/vol) fetal calf serum (FCS) (Sigma, Buchs, Switzerland). Monocyte-derived Mφ (MDM) were generated by culture of monocytes in DMEM containing 30% (vol/vol) porcine plasma.17 Alveolar Mφ (alv-Mφ) were isolated by repeated lavage, at 4° with Ca2+/Mg2+-free phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), of lungs freshly obtained from slaughtered SPF pigs.17 Bone marrow-derived Mφ (BMDM) were generated by culturing bone marrow haematopoietic cells (BMHC) in DMEM containing 20% (vol/vol) porcine plasma and 20% (vol/vol) FCS, for 7 days at 39°. Following infection of monocytic cells, the culture medium was replaced with DMEM containing 10% (vol/vol) FCS.

Immunophenotyping of leucocytes

This employed the following mAbs: anti-SWC1 [HB141, 76-6-7; American Type Culture Collection (ATCC), Rockville, MD], found on porcine monocytes;18 anti-SWC3 (DH59; VMRD, Pullman, WA) porcine pan-myeloid cell marker;18 anti-SWC9 (PM18-7, Dr Y. Kim, Finch University of Health Sciences, Chicago, IL), found on porcine Mφ but not monocytes;17 and mAb My4 (Coulter-Clone, Instrumenten-Gesellschaft AG, Schlieren, Switzerland) against human and porcine CD14.19 Incubations were performed for 20 min at 4° with the mAbs and for 15 min at 4° with phycoerythrin (PE)-conjugated antimouse immunoglobulin (DAKO, Glostrup, Denmark). Measurements were carried out using a fluorescence-activated cell sorter (FACScan; Becton Dickinson AG, Basel, Switzerland).

CSFV infection of monocytic cells

Infections were carried out for 1 hr at 39° using a m.o.i. of 0·1–10 TCID50/cell. The inoculum was removed and the cells were washed six times with PBS/2% (vol/vol) FCS (37°) before adding fresh medium. Monocytes/Mφ were activated with 10 μg/ml lipopolysaccharide (LPS; Sigma). The cyclo-oxygenase inhibitor indomethacin (Sigma)20 was employed at 10 μg/ml. Infected cells were detected using mAb against gpE214 or p125 (mAb C16; I. Greiser-Wilke, Hannover Veterinary School, Germany),21 as described above.

Infection of pigs with CSFV

Nine SPF pigs (Swiss Landrace, 3-months old) were oro-nasally infected with CSFV strain Brescia, 106 TCID50/animal. The animals were checked daily for clinical symptoms. On days 1, 3 and 5 postinfection (p.i.), three animals were killed for pathological examination and preparation of serum and PBMC. Three healthy non-infected SPF pigs of the same race and age were the source of control blood.

In a second experiment, two SPF pigs were infected as described above. Blood samples were collected daily, and the animals were killed at day 4 p.i. Three non-infected pigs of the same race and age, treated in the same way, were used as controls.

PGE2 immunoassay

Quantification of PGE2 employed an enzyme immunoassay (EIA) kit (Cayman Chemical Company, Ann Arbor, MI). The samples were assayed in triplicate and at two dilutions.

Lymphocyte proliferation assay

PBMC were cultured in round-bottom microtitre plates (Greiner, Nürtingen, Germany) at 2×105 cells/well in RPMI-1640 (Life Technologies) supplemented with 2 mm l-glutamine, 10 mm HEPES, 5×10−5 m 2-mercaptoethanol, 1% (vol/vol) non-essential amino acids and 10% (vol/vol) FCS. Cells were stimulated with a suboptimal concentration (0.5 μg/ml) of concanavalin A (Con A) (Pharmacia). Supernatants from mock- and CSFV-infected Mφ cultures were added at the different percentages (vol/vol) described in the Results section; the final volume, upon which this percentage (vol/vol) was calculated, was 200 μl/well. UV-inactivated supernatants were employed as non-infectious controls. Cell proliferation was measured after 72 hr by adding 1 μCi 3H-thymidine/well and continuing incubation for a further 18 hr. After harvesting, counts per minute (c.p.m.) were read with a Trace 96 counter (Inotech AG, Dottikon, Switzerland).

Cytokine assays

Interleukin (IL)-6 was quantified using the IL-6-dependent hybridoma B9 (ATCC).22 Tumour necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) was assayed with actinomycin D-treated PK15-15 cells (G. Bertoni, University of Berne, Berne, Switzerland).23 IL-1 was quantified using the IL-1-sensitive A375 melanoma cell line (ATCC).24

For IL-1β reverse transcription–polymerase chain reaction (RT–PCR), RNA was pelleted from 106 cells using Trizol (Life Technologies), resuspended in 10 μl of diethylpyrocarbonate (DEPC)-treated water, and stored at −70°. The RT–PCR used the Titan RT–PCR system (Boehringer-Mannheim, Mannheim, Germany), according to the manufacturer’s instructions, with 2 μl of RNA template plus 0·4 μm sense and antisense primers:25 IL-1β (5′-AAA GGG GAC TTG AAG AGA G-3′ and 5′-CTG CTT GAG AGG TGC TGA TGT-3′); porcine β-actin (5′-GGA CTT CGA GCA GGA GAT GG-3′ and 5′-GCA CCG TGT TGG CGT AGA GG-3′). The latter were the internal controls for comparable amounts of input RNA. Reactions were performed in an Omnigene Thermocycler (Hybaid, MWG Biotech, Ebersberg, Germany) as follows: reverse transcription at 50° for 30 min; cDNA amplification at 94° for 45 seconds, 35 cycles of 30 seconds at 94°, 30 seconds at 55°, 2 min at 68° and 5 min at 68°. PCR products were electrophoresed on 2% (wt/vol) agarose gels, with ethidium bromide.

RESULTS

CSFV infection of porcine monocytes and Mφ

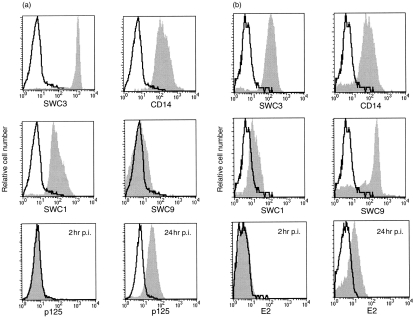

All sources of monocytic cells – monocytes, MDM, alv-Mφ and BMDM – were susceptible to virus infection. Up to 90% of cells expressed viral p125 (Fig. 1a) and E2 (Fig. 1b) 24 hr p.i. (m.o.i. 10 TCID50/cell). Monocytes (characterized as SWC1+SWC3highCD14+SWC9−; Fig. 1a) and MDM (SWC1dim/−SWC3+CD14+SWC9+; Fig. 1b) were both positive for p125 and E2. This was seen at 24 hr but not at 2 hr p.i., demonstrating that the detection of viral protein was not caused by phagocytosis of the input virus. Infection with CSFV did not alter the cell phenotype (data not shown), or increase the number of propidium iodide-positive cells, confirming the non-cytopathic nature of the infection (data not shown). The infection was productive. For example, at a m.o.i. of 0·1 TCID50/cell, extracellular virus titres ranged from 101·17 TCID50/ml (residual virus inoculum) at 0 hr p.i., to 102·83 TCID50/ml after 24 hr and a maximum of 105·8 TCID50/ml at 48 hr p.i.

Figure 1.

Phenotype of and classical swine fever virus (CSFV) infection in (a) monocytes and (b) monocyte-derived macrophage (MDM). Histograms SWC3, CD14, SWC1 and SWC9 show overlays of cells stained with the monoclonal antibody (mAb) against the respective cell-surface marker (solid histograms) over negative control cells stained with the conjugate alone (unfilled histograms). The histograms p125 (a) and E2 (b) show CSFV-infected cells stained with the mAb against viral p125 or E2 (solid histogram) over mock-infected control cells (unfilled histograms). Flow cytometric analysis of the infected cells was at 2 and 24 hr postinfection (p.i.) with a multiplicity of infection (m.o.i.) of 10 tissue culture infective dose 50% (TCID50)/cell.

PGE2 production by infected monocytic cells

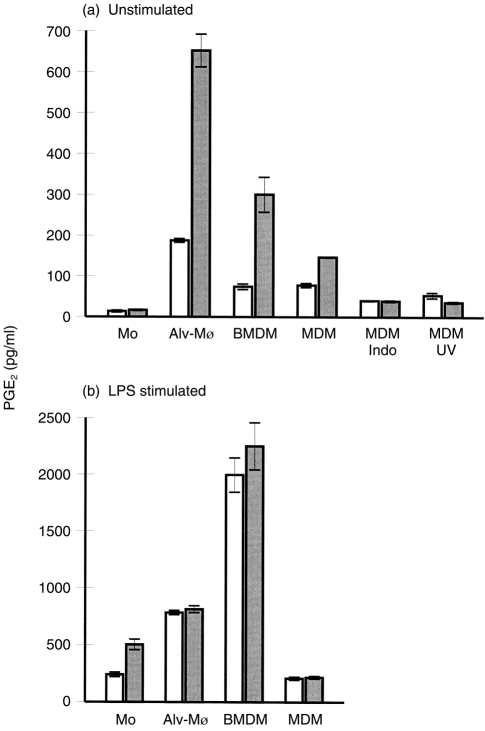

Infected monocytic cells, regardless of source and m.o.i., produced higher levels of PGE2 compared with uninfected cells. In the absence of stimulation, only the infected Mφ secreted PGE2 (Fig. 2a). With monocytes, LPS stimulation was required, but the infected cells were still more productive than their uninfected counterparts (Fig. 2b). In contrast,following LPS stimulation of Mφ, CSFV infection no longer enhanced the PGE2 induction (Fig. 2b).

Figure 2.

Classical swine fever virus (CSFV) induces prostaglandin E2 (PGE2) production by monocytes and macrophages (Mφ) of different sources. Blood monocytes (Mo), alveolar Mφ (alv-Mφ), bone marrow-derived Mφ (BMDM) and monocyte-derived Mφ (MDM) were mock infected (open bars) or infected with CSFV (filled bars). The results, expressed as pg/ml (5×105 cells), are shown for 48 hr postinfection (p.i.) with a multiplicity of infection (m.o.i.) of 0·1 tissue culture infective dose 50% (TCID50)/cell. (a) Unstimulated cultures; ‘Indo’, cultures treated with indomethacin (10 μg/ml); ‘UV’, mock and virus preparations were inactivated by UV treatment before attempted infection. (b) Lipopolysaccharide (LPS; 10 μg/ml)-stimulated cultures. Error bars shown are±SE of the mean of triplicate values within a typical experiment. The experiments were repeated three times with similar results obtained each time.

Virus replication was required for the up-regulation of PGE2 production, seen by the ineffectiveness of UV-inactivated virus (Fig. 2a, ‘UV’). Treatment with indomethacin, an inhibitor of PGE2 synthesis,20 demonstrated that the PGE2production was an active de novo process (Fig. 2a, ‘Indo’).

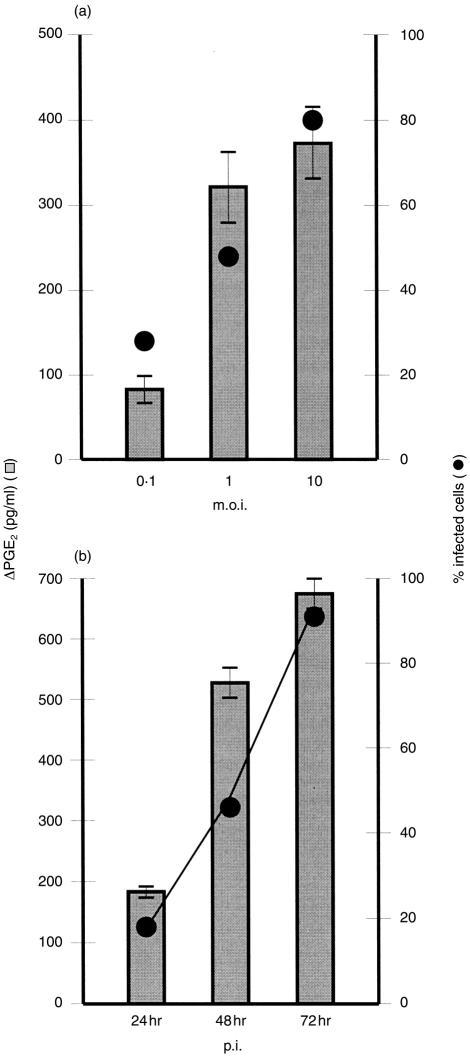

The induction of PGE2 was also analysed with respect to the percentage of infected cells. PGE2 production by infected cultures increased proportionately with the number of infected cells (Fig. 3). This was noted in terms of both the m.o.i. (Fig. 3a) and time p.i. (Fig. 3b).

Figure 3.

(a) Relationship between prostaglandin E2 (PGE2) production (histogram bars, left y-axis), multiplicity of infection (m.o.i.) (0·1, 1 and 10 tissue culture infective dose 50% (TCID50)/cell, x-axis) and the percentage of infected – PGE2 positive – alveolar macrophage (alv-Mφ) (line graph, right y-axis), 24 hr after infection with classical swine fever virus (CSFV) at a m.o.i. of 0·1, 1 and 10 TCID50/cell. (b) Relationship between PGE2 production (histogram bars, left y-axis) and the percentage of infected – PGE2 positive – alv-Mφ 24, 48 and 72 hr p.i. (m.o.i. of 0·1 TCID50/cell). The amount of PGE2 was calculated as: [PGE2]virus– [PGE2]mock (ΔPGE2), and expressed as pg/ml (5×105 cells). Error bars shown are±SE of the mean of triplicate values within a typical experiment. The experiments were repeated three times, with similar results and relationship obtained each time.

Co-stimulatory influence of CSFV-infected monocytes/Mφ

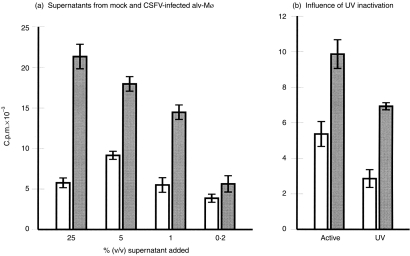

Owing to the known inhibitory effects of PGE2 on lymphocyte proliferation, the PGE2-containing supernatants from mock- and CSFV-infected monocytic cells were incubated with freshly isolated PBMC. Figure 4(a) shows a typical experiment. With supernatants from infected Mφ, enhanced proliferation of suboptimal Con A-stimulated PBMC was observed. The enhancement occurred in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 4a). Cultures in which Con A was omitted, or used at an optimal dose (10 μg/ml) also displayed such an enhancement (data not shown). UV-irradiated supernatant (‘UV’, Fig. 4b) from virus-infected cultures also increased the PBMC proliferation rate compared with supernatants from mock-infected cultures (Fig. 4b).

Figure 4.

Co-stimulatory activity of supernatants from classical swine fever virus (CSFV)-infected macrophage (Mφ) on lymphocytes. (a) Different concentrations of supernatants (x-axis; per cent vol/vol added) from mock-treated (open bars) and CSFV-infected (filled bars) alveolar Mφ (alv-Mφ) cultures were added to concanavalin A (Con A)-stimulated (0·5 μg/ml) peripheral blood mononuclear cells. (b) Comparison of supernatants (10 μl=5% vol/vol) containing live virus (active) with those in which the virus was UV inactivated (UV). Error bars shown are±SE of the mean of triplicate values within a typical experiment. The experiments were repeated four times with similar results and effects obtained each time.

Cytokine production by CSFV-infected monocytic cells

The above results demonstrated that supernatants from CSFV-infected monocytic cells contained lympho-stimulatory factors that dominated any immunosuppressive activity expected from the PGE2. Cytokines known to have such effects were therefore sought in supernatants from mock- and CSFV-infected cultures. Low levels of TNF-α and IL-6 (<3 pg/ml and <1 U/ml) were found, but no difference between mock and virus-infected cultures was noted (data not shown). After LPS stimulation, TNF-α and IL-6 production increased, but similarly with mock- and virus-infected cultures (data not shown). A role for TNF-α in the co-stimulatory activity was also excluded by addition of anti-TNF-α mAbs to the PBMC cultures. The antibody had no influence on the enhanced proliferation (data not shown).

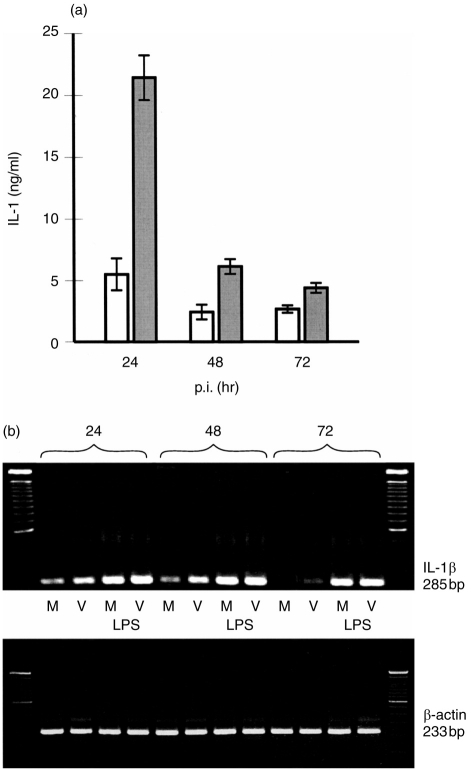

Low levels (<20 pg/ml) of IL-1 were also detectable in mock- and virus-infected Mφ (data not shown). However, IL-1 is a cytokine associated more with monocytes.26 Non-stimulated monocytes released between 1 and 10 pg/ml IL-1, with up to fivefold enhancement, after virus infection (data not shown). Elevated IL-1 mRNA activity was also detected (Fig. 5b). LPS stimulation increased IL-1 production, with the virus-infected monocytes still yielding higher levels compared with the mock controls (Fig. 5a). The virus infection-enhanced production of IL-1 occurred early, when the cells were monocytes. As they matured into Mφ, they lost this ability to synthesize IL-1, even after stimulation with LPS (Fig. 5a). This loss of IL-1 synthesis was also reflected in the IL-1 mRNA signal (Fig. 5b), except with the LPS-stimulated cells. Nevertheless, there was no correlation between IL-1 activity and the capacity of the supernatants to induce lymphoproliferation. Both infected monocytes and Mφ were lympho-stimulatory (data not shown).

Figure 5.

Classical swine fever virus (CSFV) induces interleukin (IL)-1 gene transcription and bioactivity in monocytic cells. (a) Monocytes were mock infected (open bars) or infected with CSFV (filled bars) at a multiplicity of infection (m.o.i.) of 1 tissue culture infective dose 50% (TCID50)/cell, stimulated with lipopolysaccharide (LPS) and supernatants tested for IL-1 bioactivity (ng/ml; 5×105 cells/ml) 24, 48 and 72 hr postinfection (p.i.). Error bars shown are±SE of the mean of triplicate values within a typical experiment. (b) Reverse transcription–polymerase chain reaction (RT–PCR) amplification products of IL-1β (upper gel) and β-actin (lower gel) mRNA transcripts isolated from mock-treated (‘M’) and CSFV-infected (‘V’) monocytes (m.o.i. 1 TCID50/ml). Where indicated, cultures were stimulated with LPS (10 μg/ml, ‘LPS’). Equal amounts of extracted RNA were employed in each lane, as indicated by the β-actin RT–PCR (lower gel). The experiment was repeated three times with similar results obtained each time.

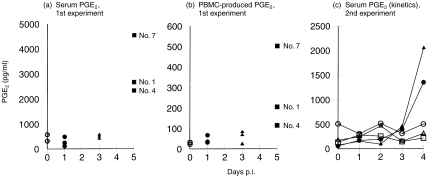

PGE2 and IL-1 production in vivo following CSFV infection of pigs

The in vivo relevance of the above results was tested by infection of pigs with the same CSFV as had been employed with the in vitro infections. Uninfected animals yielded serum PGE2 levels <600 pg/ml (Fig. 6a, 6c). Infected pigs – killed at days 1 and 3 p.i. for pathological examination – yielded serum PGE2 levels similar to the controls. At day 5 p.i., elevated (5–20 times) serum PGE2 production was evident (Fig. 6a). When infected pigs were serially bled, a 2·5–4-fold increase in serum PGE2 was noted at day 4 p.i. (Fig. 6c).

Figure 6.

Prostaglandin E2(PGE2) (pg/ml) detected in (a) the sera and (b) culture supernatants of peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) (5×105cells/ml) obtained from uninfected control pigs (day 0) and from pigs infected with classical swine fever virus (CSFV) strain Brescia at an infectious dose of 106 tissue culture infective dose 50% (TCID50)/animal. The results are shown for different animals killed at different times postinfection (p.i.). Each symbol represents a different animal, the same type of symbol being used for animals killed at a particular time-point p.i. Numbers (No.) indicate the identification number of the corresponding pigs producing detectable elevated levels of PGE2 in their serum and/or their PBMC in culture. (c) Time course of PGE2 found in sera from non-infected control pigs (open symbols) and from pigs infected with CSFV strain Brescia at an infectious dose of 106 TCID50/animal (filled symbols). The animals were bled daily until day 4 p.i.

Cultured PBMC from infected pigs also yielded elevated PGE2 production at day 5 p.i. (Fig. 6b). The relative increase in PGE2 production by the PBMC from each pig at day 5 p.i. correlated with the different levels of PGE2 found in the serum of those same animals.

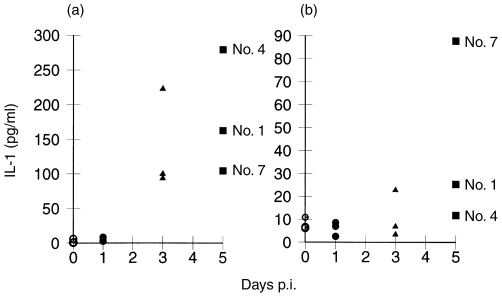

Elevated IL-1 production was also found in the sera of pigs at days 3 and 5 p.i., but not at day 1 p.i. (Fig. 7a). PBMCs from the infected animals displayed enhanced IL-1 production, again at days 3 and 5 p.i. Unlike PGE2, the elevated IL-1 levels from PBMC showed no correlation with those found in the sera (Fig. 7b).

Figure 7.

Interleukin (IL)-1 (pg/ml) detected in (a) the sera and (b) peripheral blood mononuclear cell (PBMC) cultures (5×105cells/ml) obtained from uninfected control pigs (day 0) and from pigs infected with classical swine fever virus (CSFV) strain Brescia at an infectious dose of 106 tissue culture infective dose 50% (TCID50)/animal. Each symbol represents a different animal, the same type of symbol being used for animals killed at a particular time-point postinfection (p.i.). Numbers (No.) indicate individual pigs at day 5 p.i.

Pathological characteristics of CSFV-infected pigs

After infection, all animals had elevated body temperatures (greater than 39·8°) by day 3 p.i., reaching maximum levels at 4 days p.i. (data not shown). Lymphopenia was evident from 24 to 48 hr p.i. Peripheral blood lymphocyte (PBL) counts were 2200–6400 cells/μl by day 4 p.i., compared with 13 100 (±2400) leucocytes/μl from 24 gender- and age-matched control pigs (data not shown). The infected animals showed typical clinical signs of CSF at days 4 and 5 p.i. Petechial haemorrhages were noted in the kidneys, lymph nodes, urinary bladder and liver (data not shown). Pathognomonic infarction of the spleen was clearly identifiable at this stage. This contrasted with the lymphopenia – already evident within 24–48 hr after infection.

DISCUSSION

The centrally important role that monocytic cells play in innate and adaptive immune responses renders them a critical element with respect to immunomodulatory virus infections. In order to combat such infections, it is necessary to understand more about how the immunomodulations are effected. One particularly useful model in this context is CSF, wherein monocytes and Mφ come to dominate in blood and lymphoid tissues.4,5 While porcine buffy coat27 and monocytic cell cultures,7,28 are susceptible to virus infection, it is the myeloid cells that are amongst the first leucocyte targets for the virus.1,3,4 Monocytes and Mφ from different sites of the body were indeed all susceptible to a productive non-cytopathic infection by CSFV. This non-cytopathic characteristic, wherein neither morphology nor viability of infected cells is altered, is important. It permits the study of infected monocytic cells and their immunomodulatory potential without interference from direct virus cytopathogenicity. Owing to this, it was possible to determine that the cells uninfected during CSF were being killed in the leukopenia.4 Consequently, virus-induced alterations in monocytic cell secretory properties would be of importance in the promotion of disease pathology. The characteristics of monocyte/Mφ traffic in the body would also exacerbate the pathological scenario.

When monocytes or Mφ were infected with CSFV in vitro, PGE2 secretion increased, and this increase was dependent on virus infection of the cells. Prostaglandins of the E series are involved in down-regulation of a variety of immune functions.11 Immunosuppression by certain viruses, which infect monocytes/Mφ, also involves PGE2,9–10 including infections by the flavivirus dengue virus29 and the pestivirus BVDV.30 However, CSFV infection of monocytic cells induced enhanced lymphocyte proliferation, despite the elevated PGE2. Thus, PGE2 induction by virus infection of monocytic cells does not guarantee a suppressive immunomodulation. On the contrary, an infection of monocytes/Mφ, such as that by CSFV, will induce lympho-stimulatory factors that dominate the suppressive capacity of PGE2. Lympho-stimulatory activity has been associated with factors such as TNF-α, granulocyte–macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF), IL-1, IL-6 and IL-12.12 Analysis of CSFV-infected monocytic cells excluded an involvement for IL-6 and TNF-α. In contrast, IL-1 was inducible by CSFV infection, but was primarily a monocyte characteristic; the lympho-stimulatory activity was associated with both infected monocytes and Mφ.

A co-stimulatory activity of CSFV-infected Mφ seems contradictory to the immunosuppressive characteristics of the disease.3,4 Recent evidence has demonstrated that the lymphopenia, characteristic of CSF, actually could relate to activation-induced apoptosis of T lymphocytes.4 Although the IL-1 induced during the disease would be an obvious candidate, it was detectable after the onset of leukopenia – PGE2 induction was even later than IL-1.

Consequently, CSFV infection of monocytes/Mφ is responsible for the PGE2, and at least in part the IL-1, found in sera from animals suffering from the disease. The lack of correlation between serum IL-1 levels and production by PBMC from the same infected animals suggests an involvement of other cells – perhaps endothelial cells. Onset of the haemorrhagic disorders in CSF relate to the elevated PGE2 levels. The enhanced IL-1 production later during infection would exacerbate the PGE2 effects, including the induction of procoagulant activity in vascular endothelial cells.31 In contrast, neither IL-1 nor PGE2 relate directly to the early leukopenia in the disease. Furthermore, infected Mφ are poor IL-1 producers, but will generate lympho-stimulatory factors. Yet, IL-1 production by the few infected monocytic cells in the tonsils early after infection (A. Summerfield, unpublished results) could activate local lymphocytes. This IL-1 would not be detectable, but traffic of the activated lymphocytes could become apparent. Certainly, the apoptosis associated with the characteristic lymphopenia has been related to activation phenomena.4 This aspect of a local role during the early stages of the disease requires closer investigation, particularly of the tonsils wherein the first infected cells are found.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Swiss Federal Veterinary Office. We thank S. Basta for critical discussions, H. Gerber and Dr C. Moser for the mAbs, D. Brechbühl, R. Michel and P. Zulliger for care of the animals and blood collection, and Dr C. Griot for reviewing the manuscript. The animal experiments were performed under the authorization of the Animal Experiment Licences nos 46/96, 110/97 and 111/97, issued to the institute by the Kantonaler Veterinärdienst of the Canton of Berne, Switzerland.

REFERENCES

- 1.Trautwein G, Liess B, editors. Classical Swine Fever and Related Infections. Boston: Martinus Nijhoff Publishing; 1988. Pathology and pathogenesis of the disease; p. 27. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Susa M, Koenig M, Saalmueller A, Reddehase MJ, Thiel H-J. Pathogenesis of classical swine fever: B-lymphocyte deficiency caused by hog cholera virus. J Virol. 1992;66:1171. doi: 10.1128/jvi.66.2.1171-1175.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pauly T, Koenig M, Thiel H-J, Saalmueller A. Infection with classical swine fever: effects on phenotype and immune responsiveness of porcine T lymphocytes. J Gen Virol. 1998;79:31. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-79-1-31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Summerfield A, Knoetig SM, Mccullough KC. Lymphocyte apoptosis during classical swine fever: implication of activation-induced cell death. J Virol. 1998;72:1853. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.3.1853-1861.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ressang AA. Studies on the pathogenesis of hog cholera. II: virus distribution in tissue and morphology of the immune response. Zbl Vet Med B. 1973;20:272. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hoffmann R, Hoffmann-Fezer G, Weiss E. Knochenmarksveränderungen bei akuter Schweinepest mit besonderer Berücksichtigung der thrombopoetischen Zellen. Berl Münch Tierärztl Wschr. 1971;84:301. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Korn G, Zoeth B. The reproduction of swine fever virus in a lymphocytic-phyto-cell-line and a line of monocytic cells. Zentralbl Bakteriol [Orig A] 1971;218:407. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Voet D, Voet JG, editors. Biochemistry. New York: John Wiley & Sons; 1990. Arachidonate metabolism: prostaglandins, prostacyclins, thromboxanes, and leukotrienes; p. 658. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Foley P, Kazazi F, Biti R, Sorrell TC, Cunningham AL. HIV infection of monocytes inhibits the T-lymphocyte proliferative response to recall antigens, via production of eicosanoids. Immunology. 1992;75:391. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Krakowka S, Ringler SS, Lewis M, Olsen RG, Axtheim MK. Immunosuppression by canine distemper virus: modulation of in vitro immunoglobulin synthesis, interleukin release and prostaglandin E2 production. Vet Immunol Immunopathol. 1987;15:181. doi: 10.1016/0165-2427(87)90082-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Goodwin JS, Webb DR. Regulation of the immune response by prostaglandins. Clin Immunol Immunopathol. 1980;15:106. doi: 10.1016/0090-1229(80)90024-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Aggarwal BB, Gutterman JU, editors. Human Cytokines. Boston: Blackwell Scientific Publications; 1992. p. 46.p. 143.p. 238.p. 270.p. 418. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kasza L, Shadduck JA, Christofinis GJ. Establishment, viral susceptibility and biological characteristics of a swine kidney cell line SK-6. Res Vet Science. 1972;13:46. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Greiser-Wilke I, Moennig V, Coulibaly J, Dahle J, Leder L, Liess B. Identification of conserved epitopes on a hog cholera virus protein. Arch Virol. 1990;111:213. doi: 10.1007/BF01311055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kaerber G. Beitrag zur kollektiven Behandlung pharmakologischer Reihenversuche. Arch Exp Pathol Pharmakol. 1931;162:480. [Google Scholar]

- 16.McCullough KC, Schaffner R, Fraefel W, Kihm U. The relative density of CD44-positive monocytic cell populations varies between isolations and upon culture and influences the susceptibility to infection by African swine fever virus. Immunol Lett. 1993;37:83. doi: 10.1016/0165-2478(93)90136-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McCullough KC, Schaffner R, Natale V, Kim YB, Summerfield A. Phenotype of porcine cells: modulation of surface molecule expression upon monocyte differentiation into macrophages. Vet Immunol Immunopathol. 1997;58:265. doi: 10.1016/s0165-2427(97)00045-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lunney JK. Characterization of swine leukocyte differentiation antigens. Immunol Today. 1993;14:147. doi: 10.1016/0167-5699(93)90227-C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ziegler-Heitrock HWI, Appl B, et al. The antibody MY14 recognizes CD14 on porcine monocytes and macrophages. Scand J Immunol. 1994;40:509. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3083.1994.tb03497.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Smith WL, Dewitt DL. Biochemistry of prostaglandin endoperoxide H synthase-1 and synthase-2 and their differential susceptibility to nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. Semin Nephrol. 1995;15:179. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Greiser-Wilke I, Dittmar KE, Liess B, Moennig V. Heterogenous expression of the non-structural protein p80/p125 in cells infected with different pestiviruses. J Gen Virol. 1992;73:47. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-73-1-47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Aarden LA, De Groot ER, Schaap OL, Landsorp PM. Production of hybridoma growth factor by human monocytes. Eur J Immunol. 1987;17:1411. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830171004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bertoni GP, Kuhnert P, Peterhans E, Pauli U. Improved bioassay for the detection of tumour necrosis factors using a homologous cell line-PK (15) J Immunol Methods. 1993;160:267. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(93)90187-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nakai S, Mizuno K, Kaneta M, Hirai Y. A simple, sensitive bioassay for the detection of interleukin-1 using human melanoma A375 cell line. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1988;154:1189. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(88)90266-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dozois CM, Oswald E, Gautier N, Serthelon J-P, Fairbrother JM, Oswald IP. A reverse transcription–polymerase chain reaction method to analyze porcine cytokine gene expression. Vet Immunol Immunopathol. 1997;58:287. doi: 10.1016/s0165-2427(97)00039-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mayernik DG, Haq A, Rinehart JJ. Interleukin 1 secretion by human monocytes and macrophages. J Leukoc Biol. 1984;36:551. doi: 10.1002/jlb.36.4.551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dunne HW, Luedke AJ, Reich CV, Hokanson JF. The in vitro growth of hog cholera virus in cells of peripheral blood. Am J Vet Res. 1957;18:502. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nakamura S, Sasahara J, Shimizu M, Shimizu Y. replication of hog cholera virus in porcine alveolar macrophage cultures. Nat Inst Anim Health Q (Jpn) 1983;23:101. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shukla M, Chaturvedi UC. Dengue virus-induced suppressor factor stimulates production of prostaglandin to mediate suppression. J Gen Virol. 1981;56:241. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-56-2-241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Welsh MD, Adair B, Schwyzer M, Ackermann M, editors. Immunobiology of Viral Infections. Lyon: Fondation Marcel Merieux; 1995. Prostaglandin E2 production by bovine virus diarrhoea virus infected cell culture and monocytes; p. 63. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bevilacqua MP, Pober JS, Majeau GR, Cotran RS, Gimbrone MA., Jr Interleukin 1 (IL-1) induces biosynthesis and cell surface expression of procoagulant activity in human vascular endothelial cells. J Exp Med. 1984;160:618. doi: 10.1084/jem.160.2.618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]