Abstract

A baculovirus recombinant antigen corresponding to the C-terminal 19 000 MW fragment of Plasmodium falciparum merozoite surface protein 1 (MSP119), has been used to prime T cells from individuals with no previous exposure to malaria, to provide help for the induction of a parasite specific antibody response in vitro. Although MSP119 alone could induce a small but detectable T-cell response, which included interleukin-4 (IL-4) secretion, this response was significantly increased by the presence of IL-2. In addition, IL-4 was shown to synergize with IL-2 for the induction of antigen-specific T-cell responses. If interferon-γ (IFN-γ), IL-12, or neutralizing anti-IL-4 antibody was present at the time of priming, the T-cell responses were abolished. Parasite-specific immunoglobulin G (IgG) could be detected after secondary restimulation with MSP119, IL-10 and anti-CD40 monoclonal antibody in cultures containing MSP119 primed T cells, autologous B cells, IL-2 and IL-4. No antibody was secreted in the absence of primed T cells in this B-cell culture assay. These data show that recombinant MSP119, a leading malaria vaccine candidate, can prime non-immune human lymphocytes under defined in vitro experimental conditions, which include regulatory cytokines and/or other costimulatory molecules. This is a complementary approach for exploring immunogenic mechanisms of potential vaccine candidates such as P. falciparum antigens in humans.

INTRODUCTION

Plasmodium falciparum resistance to existing antimalarial drugs is increasing rapidly and an effective vaccine is urgently needed to combat the annual 300–500 million cases of clinical malaria, including 1–2 million deaths, mostly in African children.1 A number of antigens (Ag) expressed at various stages of the parasite life cycle have been characterized as potential candidates for a subunit vaccine. Many vaccines under current development are designed to boost immunity in partially immune individuals living in endemic regions. In contrast, little attention has been given to subunit vaccines capable of eliciting de novo a protective immunity in naïve individuals.2 Such an approach has been restricted to studies of immunogenicity, in particular in experimental monkey models.3

The merozoite surface protein 1 (MSP1) is one of the best characterized proteins in several Plasmodium ssp., and is considered a promising antigen for the development of a vaccine against the asexual bloodstage parasite (reviewed by Holder and Riley4). The 19 000 MW C-terminal fragment of MSP1 (MSP119) has been recognized as the target of immunoglobulin G (IgG)-based protective immunity.5 Indeed, recombinant analogues have shown protective efficacy in primate models against P. falciparum and P. cynomolgi, a close relative of P. vivax, which also infects humans6–7 (Longacre et al., unpublished).

Several laboratories6–10 have shown that recombinant MSP119 contains both T- and B-cell epitopes. We have developed an in vitro culture system permitting the secretion of parasite-specific IgG by purified B lymphocytes after stimulation with MSP119, anti-CD40 antibody (Ab) and interleukin-10 (IL-10), in the absence of cognate T-cell interaction. In this system, the responding B cells consisted primarily of cells already expressing surface immunoglobulin γ heavy chain; these cells are referred to as sγ+ B cells. In addition, only B cells from P. falciparum immune individuals could be driven to differentiate in vitro.11

This study examines in vitro priming of T cells from P. falciparum non-immune individuals by baculovirus recombinant MSP119 and the subsequent induction of specific IgG secretion by autologous B lymphocytes after MSP119 restimulation. This approach documents the immunological effects of an important vaccine candidate on T and B lymphocytes at the cellular level. In particular, it details the contributions of costimulatory molecules to T- and B-cell co-operation in MSP119-driven immune responses.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cellular preparations

Peripheral blood (30 ml) was obtained from volunteer staff donors recently arrived in Africa with no previous exposure to Plasmodium ssp. and no P. falciparum-specific or Plasmodium crossreactive Abs. For some control experiments, certain donors were bled two or more times at 1 month intervals. Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) were obtained by Ficoll diatrizoate gradient separation and were further depleted of CD56+ (natural killer, NK) cells by incubation with anti-CD56 monoclonal antibody (mAb) followed by a second incubation with goat-anti-mouse IgG-coated magnetic beads as described.12 The remaining PBMC were then fractionated. Small aliquots were cryopreserved for use as antigen-presenting cells (APC). The majority of NK− PBMC were then depleted of CD19+ B cells with goat anti-human CD19-coated magnetic beads. Reactive cells were recovered and cultured in complete medium for 24 hr to allow capping and shedding of membrane CD19/anti-CD19-coated bead complexes.12 They were then cryopreserved until use. CD56− CD19− cells were then depleted of CD14+ (monocytes) and CD1a+ and CD1c+ (mostly circulating dendritic cells) by magnetic bead selection, as described above. The remaining cells were predominantly CD3+ T cells, with purities ranging from 96 to 99%, as estimated by means of flow cytometry. In certain experiments, the CD3+ population was further depleted of CD8+ T cells by incubation with anti-CD8-coated Dynabeads® and therefore consisted of almost pure CD4+ T cells. MAb used for selection were purchased from Immunotech (Marseille, France); magnetic beads for direct (Dynabeads®) or indirect cell separation (using goat antimouse-coated beads) were obtained from Dynal (Oslo, Norway).

For control experiments, PBMC were obtained from P. falciparum-immune blood donors whose characteristics have been previously reported.11 Unseparated PBMC were processed for culture experiments as described previously.

Parasite and other antigens

Ags used in the present work were of P. falciparum origin (MSP119 and a crude parasitized, merozoite enriched, red-blood cell extract) and the keyhole limpet haemocyanin (KLH). KLH (Calbiochem, San Diego, CA) is a glycoprotein known to be immunogenic in humans14 and it was used as a control immunogen capable of sensitizing T cells in such a manner that they could help unprimed B cells to secrete KLH-specific IgG Abs in vitro, as previously demonstrated.15

MSP119 was produced in the baculovirus/insect cell expression system as described16 and subsequently purified by immunoaffinity chromatography using the G17 mAb (S. Longacre, I. Holm and F. Nato, unpublished data). The recent determination of the crystal structure of a similar baculovirus MSP119 preparation indicates that this antigen is highly purified and that its characteristic epidermal growth factor (EGF)-like domains are correctly folded (V. Chitarra, I. Holm, G. Bentley and S. Longacre, unpublished data). A mock baculovirus/insect cell culture was used to control for MSP119 specificity where relevant.

A crude P. falciparum merozoite extract was prepared as described.10 This parasite antigen preparation contains MSP119 derived peptides as it is recognized by anti-MSP119 polyclonal and monoclonal Abs. In addition, plasma from P. falciparum-immune individuals most generally contained Abs that reacted with both MSP119 and this crude P. falciparum merozoite extract11 (Perraut et al., manuscript in preparation).

Culture conditions

T cells were cultured in either RPMI-1640 medium (Gibco, Paisley, UK) or Iscove’s Dulbecco’s Modified Medium (IDMM; Gibco), plus 10% fetal calf serum (FCS; Hyclone, Logan, UT),13 in the presence or absence of 1 μg/ml MSP119, 100 IU/ml IL-2, 100 IU/ml IL-4, 50 IU/ml interferon-γ (IFN-γ), 50 IU/ml IL-12, 5 μg/ml neutralizing rabbit anti-IFN-γ or anti-IL-4 Ab. In a limited number of experiments, KLH (10 μg/ml) was used to prime unsensitized T cells under similar conditions except for the presence of anti-IFN-γ, as described previously.15 Recombinant human cytokines (except IL-2, a gift from Sanofi, Labège, France) and anti-cytokine Abs and rabbit control Ab (except anti-IFN-γ Ab, a gift from Dr T. Nutman, NIH, Bethesda, MD) were obtained from Peprotech (London, UK); recombinant cytokines were produced in baculovirus/insect cells. T cells (106/ml) were cultured in 1 ml in 24-well culture plates (Falcon®, Becton Dickinson, Franklin Lakes, NJ) for the primary stimulation, in the presence of 105 mitomycin-C-treated (Sigma, St Louis, MO) autologous PBMC.15 Cultures were restimulated three times at 1-week intervals with the same concentrations of reagents used initially and every week 50% of the culture supernatant was replaced with medium and 105 thawed, mitomycin-C-treated PBMC were added to each well. At the end of the culture period, floating and loosely adherent cells were recovered and layered on an equal volume of FCS, and centrifuged at room temperature (RT) for 10 min at 800 g. Pellets were then washed and resuspended in RPMI with 10% FCS and counted. Viable cells recovered from this procedure were examined and enumerated by means of conventional microscopy. T cells recovered from this procedure are referred to as ‘responding T cells’.

‘Responding T cells’ were allowed to rest for 24–48 hr in culture medium, washed, and resuspended at 106/ml in medium with 10% FCS. In some experiments, T cells (106/ml in RPMI) were then restimulated in 200 μl in 96-well round-bottomed culture plates (Falcon®) with or without 1 μg/ml MSP119 or 10 ng/ml phorbol myristate acetate (PMA; Sigma) for 48 hr. Culture supernatants were harvested and tested for the presence of IL-4. In other experiments, 5 × 104‘responding T cells’ and 5 × 103 cryopreserved autologous CD14+ monocytes/well were seeded in round-bottomed culture plates in 100 μl and exposed to 0·05 μg/well of MSP119, or mock baculovirus/insect cell supernatants, or 0·5 μg/well of tetanus toxoid antigen (a gift from Pasteur-Mérieux-Connaught, Marnes la Coquette, France); tritiated-thymidine incorporation was measured at day 6 as described.10 In most experiments, ‘responding T cells’ were resuspended in IDMM plus 10% FCS.

B cells were thawed, resuspended in IDMM with 10% FCS (which does not select for autonomous growth and differentiation of human B lymphocytes as shown previously13) and seeded at 106/ml in 100 μl in 96-well round-bottomed culture plates (Falcon®), with varying numbers of ‘responding T cells’, in the presence or absence of IL-2, IL-4 or IL-10 (50– 100 IU/ml), and 10 μg/ml anti-CD40 mAb ‘89’ (IL-10 and mAb ‘89’ were gifts from Schering-Plough, Dardilly, France). Culture supernatants were recovered after 10 days and tested for the presence of total and parasite-specific IgG.

In a limited number of control experiments, PBMC from P. falciparum-immune individuals (106/ml in IDMM plus 10% FCS) were cultured in 250 μl in 48-well culture plates (Falcon®) with or without 0·1 μg/ml MSP119 as predetermined. Culture supernatants were recovered after 10 days and tested for the presence of parasite-specific IgG.

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) analysis of cytokine production

IL-4 in T-cell cultures was measured by means of the Medgenix kit (Fleurus, Belgium), as specified by the manufacturer. Data are expressed as pg/ml.

ELISA analysis of total and antigen-specific IgG in culture supernatants

Total and parasite-specific IgG were measured by ELISA as described.9 Briefly, for total IgG detection, Immulon-4 plates (Dynatech, Springfield, VA) were coated with a mouse mAb to human IgG (1 μg/ml; Immunotech). Culture supernatants were diluted as appropriate, and incubated overnight (4°). Peroxidase-conjugated polyclonal goat antihuman IgG (1:10 000) was used as a secondary reagent and incubated for 1 hr at 37° (Cappel/Organon-Technica, Turnhout, Belgium). The peroxidase substrate was orthotolidine/H2O2 (Sigma).

To detect parasite specific IgG, a crude P. falciparum merozoite extract was used. A lysate of noninfected erythrocytes in culture medium was used as a control. MaxiSorp plates (Nunc, Roskilde, Denmark) were coated overnight at 4° with 2 μg/ml of a crude merozoite protein preparation. Supernatants from each culture were incubated for 2 hr at 37° and then overnight at 4°. Subsequent steps were performed as described above.

To detect MSP119 or KLH-specific IgG, Immulon-4® plates were coated with either 1 μg/ml of recombinant MSP119 or with 2 μg/ml of KLH and subsequent steps were performed as described.

OD values were read at 450 nm in a Titertek Multiscan (Flow Laboratories). Results are expressed as OD ratios calculated by dividing the OD values in antigen-stimulated plates (duplicates) by the value in the unstimulated plates (cells without antigen but cultured in the presence of additive cytokines as for antigen-stimulated plates).11–13,15

Statistical analysis

Comparison of values obtained in individual cultures was done using the Mann–Whitney test for non-normally distributed values. In these specific comparisons, the degree of freedom was usually 5. Comparisons for paired values were made by means of the Wilcoxon signed rank test.

RESULTS

T-cell responses after in vitro priming and subsequent restimulation with MSP119

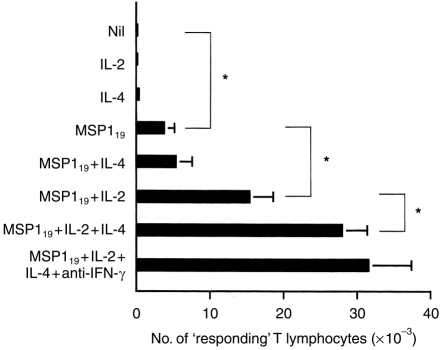

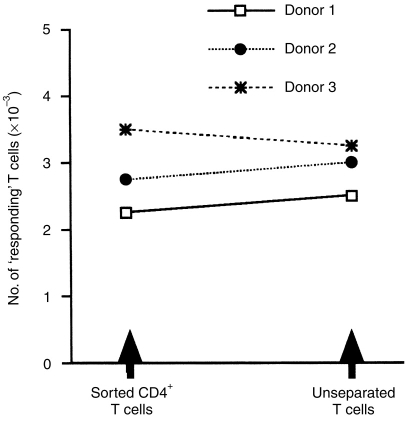

The effect of P. falciparum MSP119, on purified peripheral blood T lymphocytes from individuals not previously exposed to P. falciparum, was examined in the presence or absence of recombinant human cytokines and neutralizing Abs to these cytokines. The T cells were restimulated weekly with the same stimuli used in the initial cultures. At day 28, supernatants were discarded and after gentle washings in FCS, the number of T-cell blasts was determined using conventional microscopy. Figure 1 shows that after a 4-week stimulation with MSP119 in the absence of exogenous cytokines, ≈0·3% of the initial number of T lymphocytes was recovered (3·8±1·4 × 103 T-cell blasts versus 0; P = 0·02). No T cells were recovered in equivalent cultures without any stimulus and IL-2 or IL-4 alone could not promote the activation and/or survival of the cultured T cells (Fig. 1). Significantly, increased numbers of blast-shaped T cells were seen in cultures with MSP119+IL-2 (15·4±3·3 × 103 T-cell blasts versus 3·8±1·4; P = 0·02) or, to a lesser extent, MSP119+IL-4 (5·4±2·1 × 103 T-cell blasts versus 3·8±1·4; P = 0·02). IL-4 could synergize with IL-2 to promote T-cell blastogenesis (27·9±5·6 × 103 T-cell blasts versus 3·8±1·4; P = 0·04), a response which was not significantly enhanced by neutralizing anti-IFN-γ Ab (31·7± 5·6 × 103 T-cell blasts versus 27·9±5·6). The specificity of the T-cell responses was confirmed by measuring 3H-thymidine incorporation in T cells reexposed to MSP119 or a control antigen (Table 1). Figure 2 shows that there was no significant difference in the number of responding T cells after priming unseparated or CD8+-depleted T-cell populations from the same donors, suggesting that CD4+ cells are preferentially expanded under these culture conditions. This conclusion was supported by cytofluorimetry analysis (data not shown).

Figure 1.

T-cell responses after in vitro priming with MSP119 in the presence of various cytokines. Purified, naive T cells were exposed to weekly stimulation with antigen in the presence of various cytokines. After 28 days, blastic cells were recovered from individual cultures and counted by conventional microscopy. The geometric means±SD of six individual experiments are shown. Asterisks indicate statistical significance (P < 0·05).

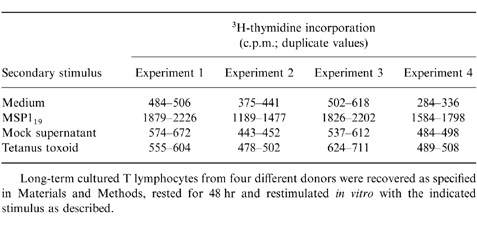

Table 1.

MSP119-primed T lymphocytes are reactive to the immunogen upon restimulation in vitro

Long-term cultured T lymphocytes from four different donors were recovered as specified in Materials and Methods, rested for 48 hr and restimulated in vitro with the indicated stimulus as described.

Figure 2.

CD4+ T cells can be primed in vitro by MSP119 in the presence of IL-2+IL-4. Purified CD4+ T cells and unseparated (CD4+ and CD8+) T cells were exposed to weekly stimulation with antigen in the presence of IL-2+IL-4, as described in Materials and Methods. After 28 days, blastic cells were recovered from three individual cultures and counted.

MSP119 and IL-2 prime T lymphocytes in vitro in an IL-4-dependent manner

Because IL-4 appeared to increase T-cell responses in the presence of MSP119 and IL-2, the effect of IL-4 was studied in more detail. Table 2 shows that the addition of neutralizing anti-IL-4, but not control, Abs completely abrogated T-cell responses to MSP119 in the presence of IL-4 (0 versus 6·25±1·9 × 103 T-cell blasts; P = 0·03) or IL-2+IL-4 (0 versus 27·5±4·1 × 103 T cell blasts; P = 0·03). IFN-γ and IL-12, which generally antagonize the biological effects of IL-4, also completely abolished T-cell responses to MSP119+IL-4 (0 versus 6·25±2 × 103 T-cell blasts; P = 0·03) and significantly diminished responses driven by MSP119 and IL-4+IL-2 (IL-12: 5·1±0·1 versus 27·9±3·4 × 103 T-cell blasts; P = 0·03). These data suggest that IL-2 sustains IL-4-mediated effects on T-cell survival in this culture system.

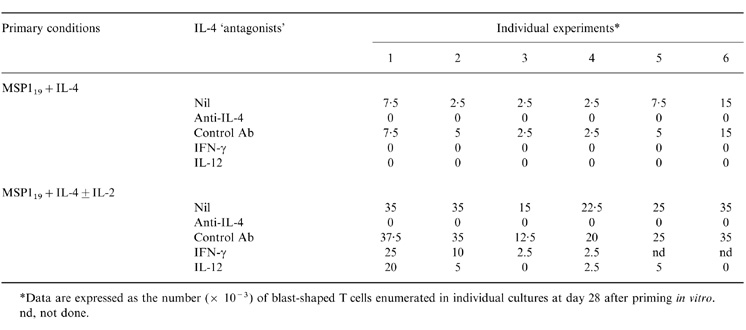

Table 2.

T-cell reactivity after priming with IL-4 ± IL-2, in the presence of absence of IL-4 ‘antagonists’

*Data are expressed as the number ( × 10−3) of blast-shaped T cells enumerated in individual cultures at day 28 after priming in vitro.

nd, not done.

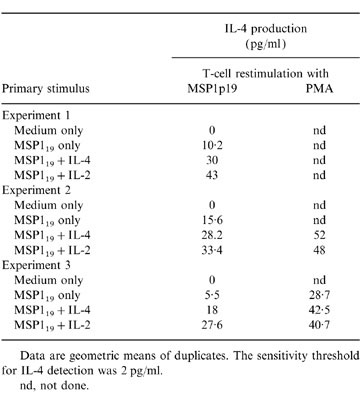

The capacity of MSP119 primed T cells to secrete IL-4 upon restimulation was determined by measuring IL-4 in cultures restimulated with either MSP119 or PMA (Table 3). In three experiments using lymphocytes from different donors, T cells initially primed with MSP119 could secrete IL-4 after restimulation with the same antigen. However, IL-4 production was consistently increased when IL-2 or IL-4 were also used for priming. PMA stimulation of MSP119-primed T cells also induced IL-4 secretion and somewhat increased quantities were observed with initial priming in the presence of either IL-4 or IL-2 (experiment 3/donor 3). The quantification of IL-4-secreting cells using a specific enzyme-linked immunospot (ELISPOT) assay support the results shown in Table 3 (not shown).

Table 3.

IL-4 production by primed T cells from three different donors upon restimulation in vitro

Data are geometric means of duplicates. The sensitivity threshold for IL-4 detection was 2 pg/ml.

nd, not done.

B cells from naïve individuals can be induced to secrete immunoglobulin in vitro in the presence of T cells primed with MSP119, IL-2 and/or IL-4

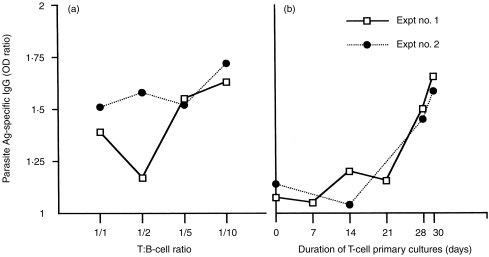

To determine whether MSP119-primed T lymphocytes could induce homologous P. falciparum naïve blood B lymphocytes to secrete IgG in vitro, they were cocultured with freshly isolated, cryopreserved B lymphocytes in the presence of MSP119 and exogenous cytokines, with or without anti-CD40 mAb. Because a 1:10 T:B ratio and 30-day T-cell priming were shown to be optimal (Fig. 3a, b), these conditions were chosen for the T–B coculture experiments.

Figure 3.

Optimization of T–B cell coculture conditions for maximum parasite specific IgG production after restimulation with MSP119. The T–B cocultures were carried out for 10 days, in the presence of IL-10 plus anti-CD40 mAb. Data are expressed as individual mean OD ratios (from duplicates) measured in different culture conditions in two individual experiments. The threshold for positivity is an OD ratio >1·5. Baseline values for actual ODs were ≈0·06. (a) T cells primed under conditions defined in the text were cocultured with autologous B cells at different T:B ratios. (b) T cells were cocultured with B cells for varying times following stimulation and/or restimulation with antigen as described in the text. The T:B cell ratio used was 1:10.

As priming of T lymphocytes in the presence of MSP119 alone did not generate sufficient numbers of activated T cells for coculture assays, T–B cocultures were done with T cells primed either in the presence of IL-2, IL-2+IL-4, or IL-2+IL-4+anti-IFN-γ. Under these conditions there was a significant production of total IgG (Fig. 4a,b, c). However, this result could be due in part to non-specific effects of cytokines and/or of activated T-cell membranes. Indeed, a non-specific production of total IgG was observed when B cells were cultured in the presence of T cells activated with a mitogenic-anti-CD3 mAb (IOT3; Immunotech, Marseille, France) coated on culture plates (data not shown). Importantly however, parasite-specific IgG could be detected in four of six cultures where T cells were primed in the presence of IL-2+IL-4 and the coculture was done in the presence of IL-10+anti-CD40 mAb (Fig. 4e). In addition, the mean level of specific IgG was significantly above control values (P = 0·03). In contrast, no specific Ab production was detected in six cultures using IL-2-primed T cells (Fig. 4d) or 12 cultures using T cells primed with IL-2+IL-4+ anti-IFN-γ (Fig. 4f). It should be noted that elevated levels of IgE were found in two separate T–B cell cocultures in the presence of anti-CD40 and IL-4, when T cells were primed with IL-2+IL-4+anti-IFN-γ (data not shown).

Figure 4.

T cells primed with MSP119 in the presence of IL-2+IL-4 provide help for parasite-specific IgG production in vitro. Purified, naive T cells were expanded with MSP119 in the presence of IL-2 (a,d), IL-2+IL-4 (b,e) or IL-2+IL-4+ neutralizing anti-IFN-γ Ab (c,f). The T–B coculture was performed for 10 days, under various culture conditions, either in the presence of IL-4 (left histograms), IL-2+IL-10 (centre histograms) or IL-10+anti-CD40 mAb (left histograms). (a–c) Total IgG production; (d–f) Parasite-specific IgG production. Data are expressed as geometric means±SD of OD ratios (from duplicates) in six (a,b,d,e) or 12 (c,f) individual experiments. The threshold for positivity is an OD ratio >1·5 (dotted line). The asterisk indicates statistical significance (P < 0·05). Baseline values for actual ODs were ≈0·09 for total IgG and 0·06 for parasite-specific IgG.

The specificity of activated T-cell help in these experiments was demonstrated by culturing purified B cells from the same and other donors (n = 7) with MSP119, anti-CD40 and IL-4 or IL-10 at different concentrations in the absence of T cells. No specific IgG production was found under these conditions (data not shown).

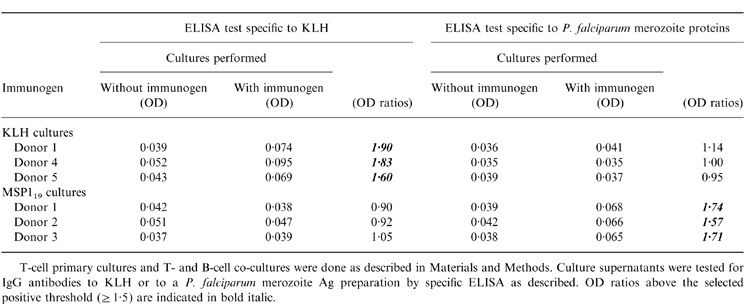

The specificity of Ab responses was tested on a crude merozoite extract of P. falciparum-infected red blood cells as described previously.11 IgG Abs, produced in cultures containing purified blood B cells from P. falciparum-immune individuals, MSP119, anti-CD40 Abs and IL-10, bound to the recombinant MSP119 with a weak affinity on ELISA plates. In addition, these Abs bound to crude merozoite antigen, unlike Abs from control cultures without MSP119 stimulation.11 To demonstrate that Abs generated in the culture system described in this study are specific to the immunogen used for in vitro priming, supernatants of three KLH-and three MSP119-primed cultures were tested in homologous and heterologous ELISAs and no signal was obtained in the heterologous culture system (Table 4).

Table 4.

Antibodies produced in cultures by unsensitized B cells in the presence of immunogen-sensitized T cells, anti-CD40 antibodies, IL-10 and antigen, are specific to the immunogen.

T-cell primary cultures and T- and B-cell co-cultures were done as described in Materials and Methods. Culture supernatants were tested for IgG antibodies to KLH or to a P. falciparum merozoite Ag preparation by specific ELISA as described. OD ratios above the selected positive threshold (≥ 1·5) are indicated in bold italic.

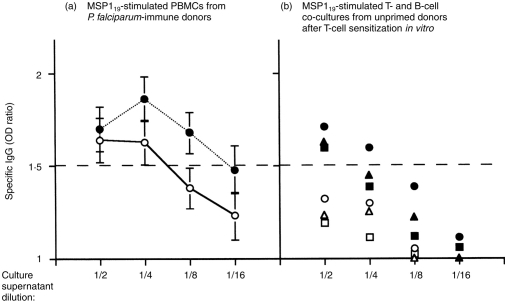

Abs generated by P. falciparum-MSP119 stimulation of unprimed B cells in the presence of MSP119 sensitized T cells appear parasite specific, as they bind to P. falciparum-merozoite antigens. To test for the relative Ab affinity and for the efficiency of the detection assay, culture supernatants were analysed for their reactivity to MSP119 and crude merozoite antigen and compared with MSP119 stimulated cultures of PBMC from P. falciparum-immune individuals where specific IgG were detected (Garraud et al. unpublished). Figure 5(a) shows that there is a good concordance between IgG reactive to MSP119 and to the crude merozoite antigen, which is reciprocal to the supernatant dilution. However, specific Abs above the positive threshold were no longer detected in 1/8 diluted supernatants when MSP119 was used to coat ELISA plates. Similarly, in T- and B-cell cocultures (Fig. 5b), specific Ab responses are reciprocal to the supernatant dilution, though generally below the positive threshold apart at the lowest dilution, particularly in recombinant antigen-coated plates. It is hypothesized that IgG Abs induced in such culture systems have a weak affinity for MSP119 bound to the plastic microtitre plates used for ELISA.

Figure 5.

Relative affinity of specific IgG antibodies produced in vitro after restimulation with P. falciparum MSP119 recombinant protein. Culture supernatants of either PBMC cultures or blood T- and B-cell cocultures were tested for the presence of IgG specific to the MSP119 recombinant protein used for stimulation (open symbols) or to a crude antigenic preparation enriched for P. falciparum merozoite proteins (closed symbols). Twofold dilutions of each culture supernatant were tested (1/2 to 1/16). The dashed line indicates the threshold for positivity (OD ratio ≥1·5). (a) Specific Ab reactivity in cultures of PBMC from P. falciparum-immune individuals. The means±SD of five individual cultures in which Abs were detected are shown. (b) Specific Ab reactivity in T- and B-cell cocultures. The values obtained from three independent cultures ae designated with different symbols. Coculture supernatants diluted 1/16 were not tested against MSP119.

DISCUSSION

The response of circulating T and B lymphocytes from individuals with no previous exposure to the malaria parasite, Plasmodium ssp., is examined here after stimulation with MSP119, a leading vaccine candidate antigen.4 In particular, in vitro culture conditions are described for priming T cells which could specifically induce purified B cells to differentiate and secrete parasite-specific IgG after restimulation with antigen and appropriate cytokines. This culture system could be used to study T-cell-dependent IgG Ab responses to other parasite Ags of interest, including other vaccine candidates.

Because protection mediated by P. falciparum bloodstage antigens is thought to be dependent on specific cytophilic Abs of the IgG1 and/or IgG3 isotypes,17 it would be useful to identify procedures which bias heavy chain switching towards either γ1 or γ3·18 In the present study, IgG production was increased by exposure of T–B cultures to IL-10, a cytokine known to potentiate the production of IgG19 and to favour switching to IgG1 and IgG3 subclasses.20 In addition, recent data from our laboratory indicate that the production of IgG by purified B cells from P. falciparum-immune individuals restimulated in vitro with MSP119 and anti-CD40 was dependent on IL-10 or factors under the control of IL-10·11.

The present study shows that correctly folded, baculovirus recombinant P. falciparum MSP119 alone is capable of inducing T-cell responses in non-exposed individuals. Thus, it is likely that this antigen has properties which can polarize the T-cell response. It has been proposed that T cells from naïve healthy donors can respond to soluble protein antigens after priming in vitro21 and that the responder T cells belong to the naïve CD45RA+ subset which has different activation requirements than memory cells.21–24 Indeed, the antigen itself, depending on its nature, may play a role in T-cell polarization in humans.13,23,25–27 Antigens which polarize T-cell responses under neutral conditions generally skew responses towards the T helper 2 (Th2) type,28 correlating with the MSP119-induced IL-4 secretion after restimulation in vitro. This data thus supports a role for the MSP119 protein itself in favouring the development of IL-4-secreting T lymphocytes.

It is interesting to note that optimal T-cell help was obtained here when T lymphocytes were primed in the presence of IL-2, while IL-4 appeared to be critical for the induction of MSP119-driven T-cell responses. Previous15 and present results suggest that in this culture system, IL-2 may rescue T lymphocytes which would otherwise have undergone apoptosis and permits the secretion of autocrine IL-4 by antigen-activated T cells, as has been suggested by others.26–31 Indeed, assuming that the presence of IL-4 is required during priming for the development of Th2-type effector cells, it is of interest to determine the origin of the IL-4. Recent evidence indicates that the initial polarizing IL-4 could be derived from non-T cells, and that certain cytokines other than IL-4 can activate human naïve CD4+ T cells and prime for IL-4 production.

The potential production of IFN-γ was limited here by removing NK cells, which represent a major source of IFN-γ after stimulation by protozoa35 and, in some experiments, by the presence of neutralizing anti-IFN-γ Ab. The addition of anti-IFN-γ gave no significant increase in reactive T cells, confirming that CD4+ T-cell immunization is independent of accompanying IFN-γ-producing cells.36 Nevertheless, T-cell priming in the presence of anti-IFN-γ Ab did not generate specific IgG secretion in T–B cocultures, although preliminary data indicate that, under these conditions, efficient help is provided for the induction of IgE (in the presence of IL-4) as expected.

When T cells were primed under favourable conditions, B cells selected from the unsensitized repertoire could terminally differentiate in vitro and secrete parasite-specific IgG. Although stimulation with anti-CD40 mAb was also necessary, it was not sufficient as purified B cells in this culture system could not produce specific IgG when stimulated with MSP119, anti-CD40 and IL-10 in the absence of primed T cells. The prolonged stimulation of T cells primed with MSP119 probably selects T cells with high affinity T-cell receptor (TCR) for certain epitope(s) in the MSP119 antigen, an event which is required for efficient T-cell help.37

The outcome of vaccination procedures can be affected by the route and the site of immunization, the concentration of immunogen and the presence of carrier or adjuvant molecules.38 Cellular effectors which are capable of presenting antigens to T cells are assumed to play a pivotal role in the selection and intensity of specific immune responses.39 Some of these effects have been demonstrated in vitro or in vivo in experimental models. We have previously shown that APC such as monocytes, CD1c+ (mostly dentritic) cells and B cells differentially costimulated MSP119 reactive T-cell populations obtained from P. falciparum-immune individuals.40 In the present study, the APC in primary cultures consisted mainly of monocytes, which optimally costimulated T cells in the presence of MSP119 in the previous study.40 However, the APC functions of B cells and dendritic cells have not been examined in this culture system, essentially for technical reasons.

In conclusion, the present study has described experimental procedures for naïve T-cell priming which polarize effector Th responses and modulate B-cell responses to a well-characterized protein antigen corresponding to a major malaria vaccine candidate. These procedures, however, do not elicit in vitro production of Abs with high affinity for the immunogen. Affinity maturation is indeed known to physiologically result from cellular and molecular events which take place in the anatomical sites of the immune responses such as germinal centres of secondary lymphoid organs.41 Meanwhile, a direct effect of this parasite protein on naïve T- and B-cell populations has been demonstrated in combination with exogenous cytokines known to be able to modify the immune response.42 This is a complementary approach for exploring immunogenic mechanisms of potential vaccine candidates such as P. falciparum Ags in humans. The validity of this approach will depend on demonstrating a protective function for the IgG Abs that are produced under such experimental conditions, when relevant Ab based in vitro correlates of protection are defined.43

Acknowledgments

The auther are indebted to staff members and visiting scientists at the Institut Pasteur de Dakar for blood donation. They acknowledge Drs. F. Brière and J. Branchereau, Schering-Plough for the gift of critical reagents. They thank the assistance of Dr A. Spiegel, Dr C. M. Nguer, Dr G. Raphenon, Mr B. Diouf (Institut Pasteur, Dakar) and Ms F. Nato (Institut Pasteur, Paris). They also gratefully acknowledge Drs T. B. Nutman (NIH, Bethesda), G. Milan (Institut Pasteur, Paris), M. Plebanski (NIMR, Oxford, UK), and J. Louis (WHO, Lausanne, Switzerland) for fruitful discussions, and T. B. Nutman for critical review of the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Engers HD, Godal T. Malaria vaccine development. Parasitol Today. 1998;14:56. doi: 10.1016/s0169-4758(97)01184-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Good MF, Kaslow DC, Miller LH. Pathways and strategies for developing a malaria blood-stage vaccine. Annu Rev Immunol. 1998;16:57. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.16.1.57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Perraut R, Garraud O. Essais vaccinaux et réponse immune contre Plasmodium falciparum chez le singe. Saimiri Méd Trop. 1998;58:76. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Holder AA, Riley EM. Human immune response to MSP-1. Parasitol Today. 1996;12:173. doi: 10.1016/0169-4758(96)20009-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Egan AF, Morris J, Barnish G, et al. Clinical immunity to Plasmodium falciparum malaria is associated with serum antibodies to three 19-kDa C-terminal fragment of the merozoite surface antigen, PfMSP-1. J Infect Dis. 1996;173:765. doi: 10.1093/infdis/173.3.765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kumar S, Yadava A, Keister DB, et al. Immunogenicity and in vivo efficacy of recombinant Plasmodium falciparum merozoite surface protein-1 in Aotus monkeys. Molec Med. 1995;1:325. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Perera KLRL, Handunnetti S, Holm I, Longacre S, Mendis K. Baculovirus merozoite surface protein 1 C-terminal recombinant antigens are highly protective in a natural primate model for human Plasmodium vivax malaria. Infect Immun. 1998;66:1500. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.4.1500-1506.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Burghaus PA, Wellde BT, Richards RL, et al. Immunization of Aotus nancymai with recombinant C terminus of Plasmodium falciparum merozoite surface 1 protein in liposomes and alum adjuvant does not induce protection against a challenge infection. Infect Immun. 1996;64:3614. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.9.3614-3619.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nguer CM, Diallo TO, Diouf A, et al. Plasmodium falciparum- and merozoite surface protein 1-specific antibody isotype balance in Senegalese immune adults. Infect Immun. 1997;65:4873. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.11.4873-4876.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dieye A, Heidrich HG, Rogier C, et al. Lymphocyte response in vitro to Plasmodium falciparum merozoite antigens in donors from a holoendemic area. Parasitol Res. 1993;79:629. doi: 10.1007/BF00932503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Garraud O, Diouf A, Holm I, Nguer CM, Spiegel A, Perraut A, Longacre S. Secretion of parasite-specific immunoglobulin G by purified blood B lymphocytes from immune individuals after In Vitro stimulation with recombinant Plasmodium Falciparum merozite surface protein-119 antigen. Immunology. 1999;97:204. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2567.1999.00763.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Garraud O, Nkenfou C, Bradley JE, Nutman TB. Differential regulation of antigen-specific IgG4 and IgE antibodies in response to recombinant filarial proteins. Int Immunol. 1996;8:1841. doi: 10.1093/intimm/8.12.1841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Garraud O, Nkenfou C, Bradley JE, Perler FB, Nutman TB. Identification of recombinant filarial proteins capable of inducing polyclonal and antigen-specific IgE and IgG4 antibodies. J Immunol. 1995;155:1316. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Curtis JE, Hersch EM, Butler WT, Rossen RD. Antigen dose in the human immune response: dose response relationship to the human immune response to keyhole limpet haemocyanin. J Lab Clin Med. 1971;75:61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Garraud O, Perler FB, Bradley JE, Nutman TB. Induction of parasite-specific antibody response in unsensitized human B cells is dependent on the presence of cytokines after T cell priming. J Immunol. 1997;159:4793. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Holm I, Nato F, Mendis KN, Longacre S. Characterization of C-terminal merozoite surface protein-1 baculovirus recombinant proteins from Plasmodium vivax and Plasmodium cynomolgi as recognized by the natural anti-parasite immune response. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1997;89:313. doi: 10.1016/s0166-6851(97)00128-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Druilhe P, Sabchaeron A, Bouharoun-Tayoun H, Oeuvray C, Perignon J-L. In vivo veritas: lessons from immunoglobulin-transfer experiments in malaria patients. Ann Trop Med Parasitol. 1997;91:S37. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Garraud O, Nutman TB. The role of cytokines in human B-cell differentiation into immunoglobulin-secreting cells. Bull Inst Pasteur. 1996;94:285. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Banchereau JTB, Rousset F. Human B lymphocytes: phenotype, proliferation, and differentiation. Adv Immunol. 1992;52:125. doi: 10.1016/s0065-2776(08)60876-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Brière F, Servet-Delprat C, Bridon J-M, Saint-Rémy J-M, Banchereau J. Human interleukin-10 induced naive surface immunoglobulin D+ (sIgD) B cells to secrete IgG1 and IgG3. J Exp Med. 1994;179:757. doi: 10.1084/jem.179.2.757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Plebanski M, Burtles SS. In vitro primary responses of human T cells to soluble protein antigens. J Immunol Methods. 1992;170:15. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(94)90241-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Plebanski M, Saunders M, Burtles SS, Crowe S, Hooper DC. Primary and secondary human in vitro T-cell responses to soluble antigens are mediated by subsets bearing different CD45 isoforms. Immunology. 1992;75:86. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Steel C, Nutman TB. Helminth antigens selectively differentiate unsensitized CD45RA+ CD4+ human T cells in vitro. J Immunol. 1998;160:351. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gupta M, Satyaraj E, Durdik JM, Rath S, Bal V. Differential regulation of T cell activation for primary versus secondary proliferative responses. J Immunol. 1997;158:4113. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wierenga EA, Snoek M, de Groot C, et al. Evidence for compartmentalization of functional subsets of CD4+ T cells in atopic patients. J Immunol. 1990;144:4651. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Parronchi P, Macchia D, Piccini M-P, et al. Allergen- and bacterial antigen-specific T cell clones established from atopic donors show a different profile of cytokine production. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88:4538. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.10.4538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mahanty S, King CL, Kumaraswami V, et al. IL-4 and IL-5 secreting lymphocyte populations are preferentially induced by parasite-derived antigens in human tissue invasive nematode infections. J Immunol. 1993;151:3704. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.O’garra A. Cytokines induce the development of functionally heterogeneous T helper cell subsets. Immunity. 1998;8:275. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80533-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ben-Sasson SZ, Le Gros G, Conrad DH, Finkelman FD, Paul WE. IL-4 production by T cells from naive donors: IL-2 is required for IL-4 production. J Immunol. 1990;145:1127. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhang XL, Giangreco L, Broome HE, Dargan CM, Swain SL. Control of CD4 effector fate: transforming growth factor β1 and interleukin-2 synergize to prevent apoptosis and promote effector expansion. J Exp Med. 1995;182:699. doi: 10.1084/jem.182.3.699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Swain SL. CD4 T cell development and cytokine polarization: an overview. J Leukocyte Biol. 1995;57:795. doi: 10.1002/jlb.57.5.795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Coffmann RL, von der Weid T. Multiple pathways for the initiation of T helper 2 (Th2) responses. J Exp Med. 1997;185:373. doi: 10.1084/jem.185.3.373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Webb LMC, Foxwell BM, Feldmann M. Interleukin-7 activates human naive CD4+ cells and primes for interleukin-4 production. Eur J Immunol. 1997;27:633. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830270309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rincòn M, Anguita J, Nakamura T, Fikrig E, Flavell RA. Interleukin (IL) -6 directs the differentiation of IL-4 producing CD4+ T cells. J Exp Med. 1997;185:4641. doi: 10.1084/jem.185.3.461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sharton-Kersten TM, Sher A. Role of natural killer cells in innate resistance to protozoan infections. Curr Opin Immunol. 1997;9:44. doi: 10.1016/s0952-7915(97)80157-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Doyle AG, Ramm L, Kelso A. The CD4+ T-cell response to protein immunisation is independent of accompanying IFN-γ-producing CD8+ T cells. Immunology. 1998;93:341. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2567.1998.00404.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dozmorov IM, Miller RA. ÷ Generation of antigen-specific Th2 cells from unprimed mice in vitro: Effects of dexamethasone and anti-IL-10 antibody. J Immunol. 1998;160:2700. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ada G. In: Vaccines in Fundamental Immunology. 3. Paul W E, editor. New York: Raven Press; 1993. p. 1309. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lanzavecchia A. Mechanisms of antigen uptake for presentation. Curr Opin Immunol. 1996;8:348. doi: 10.1016/s0952-7915(96)80124-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Garraud O, Diouf A, Nguer CM, et al. Different Plasmodium falciparum Recombinant MSP119 Antigens Differ in Their Capacities to Stimulate In Vitro Peripheral Blood T lymphocytes in Individuals from Various Endemic Areas. Scand J Immunol. 1999;49:431. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3083.1999.00511.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nossal GJV. The molecular and cellular basis of affinity maturation in the antibody response. Cell. 1992;68:1. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90198-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Taylor CE. Cytokines as adjuvants for vaccines: antigen-specific responses differ from polyclonal responses. Infect Immun. 1995;63:3241. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.9.3241-3244.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Miller LH, Good MF, Kaslow DC. The need for assays predictive of protection in the development of malaria blood stage vaccine. Parasitol Today. 1997;13:46. doi: 10.1016/s0169-4758(96)20063-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]