Abstract

The Escherichia coli heat-labile enterotoxin (LT) is an exceptionally effective mucosal immunogen and mucosal immunoadjuvant towards coadministered antigens. Although, in general, the molecular basis of these properties is poorly understood, both the toxic ADP-ribosylation activity of the LTA subunit and the cellular toxin receptor, ganglioside, GM1-binding properties of the LTB-pentamer have been suggested to be involved. In recent studies we found that GM1-binding is not essential for the adjuvanticity of LT, suggesting an important role for the LTA subunit in immune stimulation. We now describe the immunomodulatory properties of recombinant LTA molecules with or without ADP-ribosylation activity, LTA(His)10 and LTA-E112K(His)10, respectively. These molecules were expressed as fusion proteins with an N-terminal His-tag to allow simple purification on nickel-chelate columns. Their immunogenic and immunoadjuvant properties were assessed upon intranasal administration to mice, and antigen-specific serum immunoglobulin-isotype and -subtype responses and mucosal secretory immunoglobulin A (IgA) responses were monitored using enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay. With respect to immunogenicity, both LTA(His)10 and LTA-E112K(His)10 failed to induce antibody responses. On the other hand, immunization with both LT and the non-toxic LT-E112K mutant not only induced brisk LTB-specific, but also LTA-specific serum and mucosal antibody responses. Therefore, we conclude that linkage of LTA to the LTB pentamer is essential for the induction of LTA-specific responses. With respect to adjuvanticity, both LTA(His)10 and LTA-E112K(His)10 were found to stimulate serum and mucosal antibody responses towards coadministered influenza subunit antigen. Remarkably, responses obtained with LTA(His)10 were comparable in both magnitude and serum immunoglobulin isotype and subtype distributions to those observed after coimmunization with LT, LT-E112K, or recombinant LTB. We conclude that LTA, by itself, can act as a potent adjuvant for intranasally administered antigens in a fashion independent of ADP-ribosylation activity and association with the LTB pentamer.

INTRODUCTION

The Escherichia coli heat-labile enterotoxin (LT) and its close homologue from Vibrio cholerae, cholera toxin (CT), are well-known powerful mucosal immunogens and adjuvants. Both toxins have proven to be valuable tools for unravelling mechanisms of induction of mucosal immune responses, and have become standard adjuvants for experimental mucosal vaccines.1–3 However, the intrinsic toxicity of these molecules has precluded their use in human vaccination procedures. LT and CT consist of a single A subunit and an oligomer of five identical B subunits. The A subunit carries the toxic ADP-ribosylation activity of the toxin, while the B-pentamer has high affinity for the cellular toxin receptor, ganglioside GM1. Intoxication of intestinal epithelial cells with LT or CT results in persistent synthesis of cAMP and concomitant excessive electrolyte and fluid secretion to the intestinal lumen (for reviews see refs. 4,5).

Over the last 10 years, several strategies have been developed in order to investigate whether the toxic properties of LT/CT can be dissociated from their immunogenic and adjuvant properties. These involve the use of the non-toxic LTB/CTB subunit alone,6–11 antigen–adjuvant conjugates (for a review see ref. 12), and non-toxic LT/CT mutants.9,10,13–20 Thus far, with these strategies highly variable results have been obtained. For example, Lycke et al.13 showed that both recombinant CTB and an LT mutant, LT-E112K (Glu112→Lys), devoid of ADP-ribosylation activity, failed to stimulate antibody responses towards coadministered keyhole limpet haemocyanin (KLH). Furthermore, LT-E112K was found to lack the capacity to induce antitoxin antibodies.12 On the other hand, we and others have shown that LT mutants, including LT-E112K and CT-E112K, retain the immunogenic and adjuvant properties of the wild-type toxin.9,10,14–18,20 Moreover, we recently showed that recombinant LTB retains mucosal adjuvant activity towards a variety of protein antigens.9,10,25 It would appear that much of the controversy with respect to the adjuvant properties of non-toxic LT/CT variants is based on a fundamental lack of knowledge on the exact mechanisms of induction of mucosal immune responses by LT/CT in general, and the functional role of the A and B subunits in these mechanisms in particular.

In a recent study, we investigated the role of the GM1-binding affinity in the immunogenic and adjuvant properties of LTB and LT.26 It was found that an LTB mutant, LTB-G33D (Gly33→Asp), which lacks GM1-binding affinity, lost the immunogenic properties of LTB. LTB-G33D also failed to stimulate antibody responses towards coadministered influenza subunit antigen. On the other hand, the corresponding LT mutant without GM1-binding affinity (LT-G33D), did retain some immunogenicity and retained full adjuvanticity towards influenza subunit antigen. Moreover, an LT double mutant (LT-E112K/G33D), lacking both ADP-ribosylation activity and GM1-binding activity, also retained adjuvant activity towards influenza subunit antigen. Interestingly, the above molecules had identical stimulatory capacities towards intranasally administered KLH, indicating that the role of the antigen in the induction of these responses is limited.25 We concluded therefore, that GM1-binding plays a key role in the induction of antitoxin antibodies, and that GM1-binding is essential for the adjuvant properties of LTB. However, for LT, GM1-binding affinity appears to be non-essential for adjuvant activity, which, in combination with the lack of adjuvant activity of LTB-G33D, suggests a critical involvement of the A subunit in the adjuvanticity of LT. Recently, we briefly reported on direct adjuvanticity of LTA, utilizing recombinant His-tagged forms of LTA, LTA(His)10 and LTA-E112K(His)10. Both molecules were found to retain adjuvant activity towards coadministered KLH.25

In this paper, we present the construction, expression and purification of LTA(His)10 and LTA-E112K(His)10. The capacity of these molecules to induce serum and mucosal antibody responses against themselves as well as towards a coadministered unrelated antigen was investigated. The experimental approach involved intranasal (i.n.) immunization of mice with LTA(His)10 or LTA-E112K(His)10 alone or in conjunction with influenza subunit antigen. The results obtained demonstrate that immunogenicity of LTA is dependent on linkage to the LTB pentamer. By contrast, LTA-mediated adjuvanticity is demonstrated to be independent of linkage to the LTB pentamer or ADP-ribosylation activity.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cloning, expression, and purification of LTA(His)10 and LTA-E112K(His)10

LTA gene constructs were cloned using polymerase chain reaction (PCR)-primers with end-on restriction sites. Two Bam HI restriction sites were created directly in front of the amino acid 1 (Asn 1) of mature LTA and behind the stop codon of the LTA gene. As PCR templates we used either our pUC-LT or pUC-LT(E112K) plasmids,22 for construction of LTA(His)10 or LTA-E112K(His)10, respectively. PCR products were digested with Bam HI and then ligated in the Bam HI site of cloning vector pUC18, sequenced, and subsequently subcloned in expression vector pET-19b (Novagen, Madison, WI), resulting in pET-LTA and pET-LTA(E112K). Both vectors encode an LTA molecule with an N-terminal His-tag of 10 histidine residues. Escherichia coli strain BL21(DE3) was grown at 37° on LB medium containing ampicillin (50μg/ml), and was used as a host for pET-LTA and pET-LTA(E112K). Overexpression of recombinant proteins was obtained by addition of isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) to log-phase cultures of BL21(DE3) harbouring either of the above plasmids, to a final concentration of 10mm. After overnight incubation, cells were harvested by centrifugation (5min, 4000g). Bacteria were suspended in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and lysed by sonication for 5min, and overexpressed protein was retrieved in the pellet fraction after centrifugation 30min, 25 000g. Pellets were then resuspended in a solution containing 5mm imidazole, 0·5m NaCl, 20mm Tris–HCl pH7·9, and 6m urea, and again sonicated for 5min and centrifuged (30min, 25 000g). Denatured LTA(His)10 and LTA-E112K(His)10 were retrieved in the soluble fraction, and subsequently purified under denaturing conditions, using a nickel-chelate column (Novagen), which was used according to the instructions of the manufacturer. Fractions containing purified proteins were pooled and proteins were renatured by three sequential dialysis steps: overnight dialysis at 4° against 4m urea in PBS, 8hr dialysis against 2m urea in PBS, and finally overnight dialysis against PBS. Insoluble non-folded protein was removed by centrifugation for 30min, 25 000g. Refolded soluble LTA(His)10 and LTA-E112K(His)10 were recovered from the supernatant and stored at 4°. Protein concentrations were determined using the DC protein assay from BioRad (Richmond, VA). Bacterial endotoxin (lipopolysaccharide; LPS) content of protein pools was determined using a Limulus amoebocyte lysate assay kit (BioWhittaker, Walkersville, MD). LPS contamination of all protein pools was found to be less than 10ng/ml.

ADP-ribosylation assay

The ADP-ribosyltransferase activity of LTA(His)10 and LTA-E112K(His)10 was determined using diethylamino-benzylidine-aminoguanidine (DEABAG) as an artificial substrate, as previously described.22,27 The DEABAG substrate was a kind gift of Drs I. K. Feil and W. G. J. Hol (University of Washington, Seattle, WA). For determination of enzymatic activity routinely 750ng of protein was proteolytically activated with 5μg trypsin for 1hr at 37° in 50mm Tris, 20mm NaCl, 1mm ethylenediamine tetraacetic acid (EDTA), 3mm NaN3 in 200mm phosphate buffer, pH 7·5. Trypsinization was stopped by the addition of 10μg soybean trypsin inhibitor and subsequently 200μl of assay buffer [20mm dithiothreitol (DTT), 0·1mg/ml bovine serum albumin (BSA), 0·1% Triton X-100, and 2mm DEABAG in phosphate buffer] was added. The ADP-ribosylation reaction was started by the addition of 25μl 100mm NAD, and the reaction mixture was incubated for 2hr at 30°. The reaction was stopped by absorption of the unreacted DEABAG to a 1·7-ml volume of DOWEX-50W resin (BioRad) in phosphate buffer. The suspension was vortexed and centrifuged for 10min, 14 000g. The supernatant, containing the reacted DEABAG, was recovered and analysed for fluorescence in an Aminco-Bowman Series 2 fluorimeter (SLM/Aminco, Urbana), using an excitation wavelength of 361nm and recording the peak characteristic of the ADP-ribosylated product at 440nm. The amount of DEABAG converted was calculated from a standard curve. The enzymatic activity is expressed aspmol DEABAG converted pernmol protein. Wild-type LT, LT-E112K, and recombinant LTB were used as positive and negative controls, respectively. Experiments were performed in triplicate. Data are expressed as the mean±standard deviation.

Immunization and sampling procedures

Female BALB/c mice, aged 6–8 weeks, were used (Harlan, Zeist, the Netherlands). Groups consisted of four mice each. Mice were immunized i.n. without anaesthesia, by application of a 10-μl sample on the external nares. For the immunogenicity study, mice were immunized on day 0 with either 0·9μg LTA(His)10 or LTA-E112K(His)10, 2·9μg of LT (approximately equimolar amounts of LTA) or LT-E112K, 9μg LTA(His)10 or LTA-E112K(His)10, or 2μg LTB. Recombinant LTB, LT and LT mutant LT-E112K (LTA: Glu112→Lys) were cloned, expressed and purified as previously described.22 For determination of adjuvanticity, mice received either of the above in conjunction with 5μg of influenza subunit antigen, derived from influenza strain B/Harbin/7/94 (a gift from Solvay Pharmaceuticals B.V., Weesp, the Netherlands). Control animals were immunized with 5μg subunit antigen alone or were given PBS. On days 7 and 14, mice received booster immunizations of the same composition. On day 28, mice were killed and serum and mucosal samples were taken from the nasal cavity and vagina, as previously described.10 In short, animals were bled by severing the vena porta under pentobarbital anaesthesia. Individual serum samples were separated by centrifugation at 14 000g. Mucosal lavages of the nasal cavity were performed by flushing 500μl of PBS retrograde via the nasopharynx to the upper part of the trachea, flushing back, and collecting the lavage fluid at the nostrils. Vaginal lavages were collected by installing and reintroducing 150μl of PBS into the vagina with a pipettor tip. Thus, routinely 100μl of vaginal lavage fluid was obtained. Pending antibody assay sera and mucosal samples were stored at −80°.

Antibody assays

Antibody responses directed against LTA, LTB, or influenza subunit antigen were determined using an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) as described previously.10,22 Ninety-six-well ELISA plates (Greiner, Solingen, Germany) were coated overnight at 37° with either 100ng LTA(His)10, 50ng LTB, or 200ng influenza subunit antigen per well in coating buffer (0·05m sodium carbonate–bicarbonate, pH9·6). Plates were washed with coating buffer once, and then blocked with a 1% milk powder solution in coating buffer for 45min at 37°. Plates were then washed three times with PBS and stored at −80° until use. For determination of antigen-specific antibodies, appropriate dilutions of serum samples, 100μl of nasal lavage fluid or 25μl of vaginal lavage fluid of each individual mouse were transferred to the plates and serially diluted twofold in PBS/Tween (PBS containing 0·02% Tween-20). Plates were incubated for 1·5hr at 37°, and then washed three times with PBS/Tween. Next, plates were incubated with peroxidase-conjugated goat antibodies directed against either mouse immunoglobulin G (IgG), IgG1, IgG2a, IgG2b, IgG3, IgM (all 1:5000) or IgA (1:4000) (all from Southern Biotechnology Associates, Birmingham, AL). For determination of antigen-specific IgE responses, a peroxidase-conjugated mouse IgE-specific rat antibody (1:5000, Southern Biotechnology Associates) was used. As a positive control for the IgE determination, plates were coated with 100ng of a goat antibody directed against mouse IgE (Sigma, St Louis, MO), and subsequently incubated with mouse myeloma IgE (Sigma). After incubation of the plates with mouse immunoglobulin-specific conjugates for 1hr at 37°, plates were washed twice with PBS/Tween, and once with PBS. Antibodies were detected using a 0·05-m phosphate buffer pH5·6, containing 0·02%o-phenyldiamine-dihydrochloride (Eastman Kodak, Rochester, NY) and 0·006% H2O2. Colouring of plates was allowed to proceed for 30min, after which the reaction was stopped by addition of 50μl 2m H2SO4 per well, and absorbances were read at 492nm (A492) using a SPECTRA I ELISA reader (SLT, Salzburg, Austria). Titres are given as the reciprocal of the calculated sample dilution corresponding with an absorbance at 492nm (A492) of ≥0·2 after subtraction of background values of PBS-treated animals. Titres are expressed as geometric mean titres±standard deviation (GMT±SD). Comparisons between experimental groups were made using Student’s t-test. Probability (P) values <0·05 were considered significant. Presented data are representative of at least duplicate independent experiments.

RESULTS

Production and characterization of LTA(His)10 and LTA-E112K(His)10

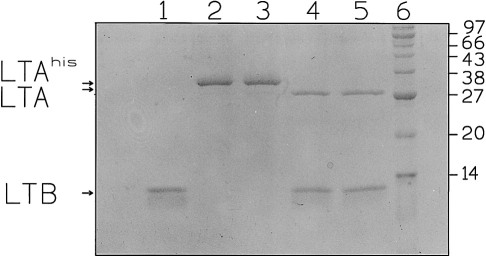

Induction of log-phase E. coli BL21(DE3) cells harbouring either the pET-LTA or the pET-LTA(E112K) plasmid resulted in efficient cytoplasmic expression of LTA(His)10 or LTA-E112K(His)10, respectively. After sonication of the bacterial cell pellet recombinant proteins were retrieved in the non-soluble protein fraction, solubilized using 6m urea, and subsequently purified under denaturing conditions using nickel-chelate affinity chromatography (Fig. 1). Recombinant purified and denatured proteins were allowed to three sequential dialysis steps as described in the Materials and Methods. Both LTA(His)10 and LTA-E112K(His)10 were recognized on Western blot by a mouse LT antiserum (not shown).

Figure 1.

Recombinant proteins used in this study. Sodium dodecyl sulphate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis analysis: lane 1, LTB; lane 2, LTA(His)10; lane 3, LTA-E112K(His)10; lane 4, LT-E112K; lane 5, wild-type LT; lane 6, molecular weight marker. Samples were boiled prior to application to the gel. Molecular weights (in thousands), LTA, LTB, and LTA(His)10 are indicated. For details see text.

The enzymatic activities of LTA(His)10 and LTA-E112K(His)10 were determined in an ADP-ribosylation assay using DEABAG as an artificial substrate. In this assay, wild-type LT was used as a positive control, and recombinant LTB and LT mutant LT-E112K (Glu112→Lys), which was previously shown to lack ADP-ribosylation activity,13,22 as negative controls. As expected, both LT-E112K and LTB gave no conversion of the DEABAG substrate (Table 1). While LTA(His)10 retained approximately 10% of the enzymatic activity of wild-type LT, LTA-E112K(His)10 completely lacked enzymatic activity.

Table 1.

ADP-ribosylation activity of LTB, LT, LT-E112K, LTA(His)10, and LTA-E112K(His)10 in DEABAG assay

Immunogenicity of LTA(His)10: induction of serum immunoglobulin and mucosal S-IgA antibodies

The immunogenic properties of LTA(His)10 and LTA-E112K(His)10 were investigated upon i.n. administration to mice. Also, the capacity of wild-type LT, LT-E112K, and recombinant LTB to induce LTA-and LTB-specific antibodies was investigated. In analogy with our previous studies,22 mice were immunized i.n. with either 2·9μg LT or LT-E112K, 2μg LTB (equimolar amounts of LTB), or 0·9μg LTA(His)10 or LTA-E112K(His)10 (approximately equimolar amounts of LTA). Separate groups were immunized with 9μg LTA(His)10 or LTA-E112K(His)10. After booster immunizations on days 7 and 14, the capacity of each molecule to induce LTA-or LTB-specific serum IgG1, IgG2a, IgG2b, IgG3, IgM, IgE or mucosal S-IgA antibodies was determined on day 28.

Both LTA(His)10 and LTA-E112K(His)10failed to induce a specific antibody response at the 0·9 or 9μg dose (Fig. 2, or data not shown). On the other hand, wild-type LT as well as LT-E112K induced strong LTA-specific serum immunoglobulin responses. As shown in Fig. 2, i.n. immunization with LT and LT-E112K resulted in high levels of LTA-specific IgG1, IgG2a, and IgG2b, indicative of a mixed T helper type 1 (Th1)/Th2-type response.28 In addition, the LTA-specific antibody titres induced by LT and LT-E112K were of the same magnitude, indicating that ADP-ribosylation is not critically involved in the induction of LTA-specific antibody responses. None of the above immunizations resulted in a detectable antigen-specific IgE response in serum (Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

Induction of LTA(His)10-specific serum immunoglobulin responses. Mice were immunized i.n. on days 0, 7 and 14 with either 2μg LTB, 2·9μg LT-E112K, 2·9μg LT, or 9μg LTA(His)10. Control animals were given PBS. Animals were killed on day 28, when serum and mucosal samples were collected. Antibody titres against LTA(His)10 were determined using ELISA. Titres are given as the reciprocal of the calculated sample dilution corresponding with an A492≥0·2 after subtraction of background values of PBS-treated animals, and are expressed as GMT±SD Mice receiving either LT or LT-E112K showed significantly enhanced LTA-specific antibody titres compared to control and LTA(His)10 immunized animals (P < 0·05).

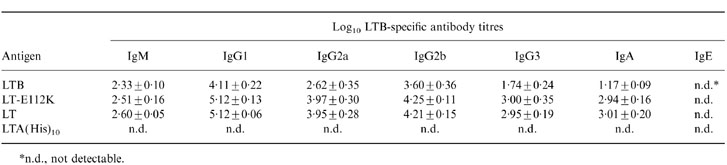

As expected, LTB was not capable of mounting an LTA-specific response (Fig. 2). However, in agreement with our previous observations, recombinant LTB, like LT and LT-E112K, induced a strong LTB-specific response (Table 2). Clearly, LT and LT-E112K were more potent immunogens than LTB. Compared to LTB, the IgG1/IgG2a ratio induced by LT and LT-E112K displayed a slight shift towards IgG2a (IgG1/IgG2a ratio 1·57 versus 1·29 and 1·30), indicating a more pronounced Th1-type immune response upon immunization with these molecules. Also, LT and LT-E112K were much more potent inducers of LTB-specific serum IgG3 and IgA. Interestingly, again all molecules failed to mount LTB-specific IgE responses in serum.

Table 2.

LTB-specific immunoglobulin isotype and subtype distribution in serum after intranasal immunization with LTB, LT-E112K, LT, or LTA(His)10

*n. d., not detectable.

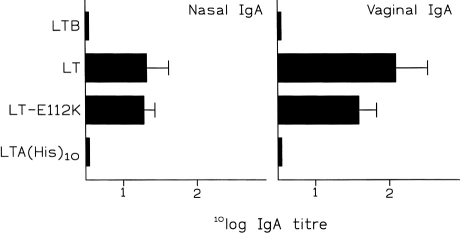

To investigate the capacity of LTA(His)10, LTA-E112K(His)10, LT, LTB and LT-E112K to stimulate local LTA-specific secretory IgA (S-IgA) antibodies, nasal and vaginal lavage fluids of the above mice were taken and analysed in an LTA(His)10-linked ELISA. Mice immunized with either LT holotoxin or LT-E112K had substantial LTA-specific S-IgA antibody levels in nasal and vaginal lavage fluids (Fig. 3). On the other hand, immunization with LTA(His)10 or LTA-E112K(His)10 failed to induce mucosal S-IgA (Fig. 3). In agreement with our previous work,9,22,26 LTB, LT-E112K and LT induced strong LTB-specific mucosal S-IgA responses in the nasal cavity and vagina (data not shown).

Figure 3.

Induction of LTA(His)10-specific mucosal S-IgA responses. Mice were immunized i.n. with either 2μg LTB, 2·9μg LT, 2·9μg LT-E112K, or 9μg LTA(His)10. Control animals were given PBS. For details see legend to Figure 2. Left-hand panel, nasal S-IgA; right-hand panel, vaginal S-IgA. Antibody titres observed in lavage fluids of LT and LT-E112K immunized animals were significantly enhanced compared to control and LTA(His)10 immunized animals (P < 0·05).

Thus, with respect to the immunogenicity of LTA upon i.n. administration to mice, we conclude that the complete AB5 complex is required for efficient induction of LTA-specific antibody responses. In addition, from the data obtained with LT and LT-E112K, we conclude that ADP-ribosylation activity does not appear to influence the magnitude of LTA-specific responses. Finally, based on the IgG subtype profile we conclude that LT, LT-E112K and LTB induced mixed Th1/Th2-type Th-cell responses.

Adjuvant activity of LTA(His)10: induction of influenza subunit antigen-specific serum immunoglobulin and mucosal S-IgA antibodies

Recently, we demonstrated that not only LT, but also recombinant LTB can act as a potent adjuvant towards intranasally administered protein antigens.9,10,25 Furthermore, using an LTB mutant lacking GM1-binding affinity, we found that GM1-binding activity is essential for the adjuvant properties of LTB.25,26 On the other hand, a non-GM1-binding LT mutant completely retained the adjuvant properties of LT holotoxin towards coadministered influenza subunit antigen, clearly suggesting that not only the LTB subunit, but also the LTA subunit has adjuvant activity.

We now investigated the adjuvant properties of LTA in a more direct manner, by immunizing mice i.n. with 9μg LTA(His)10 or LTA-E112K(His)10 in conjunction with influenza subunit antigen. As positive controls, mice were immunized with either LT, LT-E112K, or LTB and subunit antigen. Negative controls were immunized with subunit antigen alone or given PBS. After booster immunizations on days 7 and 14, antigen-specific serum immunoglobulin or mucosal S-IgA antibody responses were determined on day 28.

Figure 4 shows that immunization with subunit antigen alone resulted in poor systemic immunoglobulin responses. Surprisingly, both LTA(His)10 and LTA-E112K(His)10 strongly stimulated these responses. Especially responses observed after immunization with LTA(His)10 and subunit antigen were comparable in both magnitude and serum immunoglobulin isotype and IgG subtype distribution to those observed after immunization in the presence of LT, LT-E112K, or LTB with subunit antigen. On the other hand, LTA-E112K(His)10 clearly induced significantly lower responses, although still strong stimulation was evident. Compared to the immunogenicity study, the IgG1/IgG2a subtype ratio induced by all adjuvants showed an overall shift towards Th2, the IgG response being clearly dominated by IgG1. Neither of the adjuvants induced subunit antigen-specific serum IgA responses and, in agreement with the immunogenicity study, again no antigen-specific IgE was detected.

Figure 4.

Induction of influenza subunit antigen-specific serum immunoglobulin responses. Mice were immunized i.n. on days 0, 7 and 14 with 5μg subunit antigen alone, or in conjunction with either 2μg LTB, 2·9μg LT-E112K, 2·9μg LT, 9μg LTA(His)10, or 9μg LTA-E112K(His)10. Control animals were given PBS. Influenza subunit antigen was derived from influenza strain B/Harbin/7/94. Animals were killed on day 28, when serum and mucosal samples were collected. Antibody titres were determined using ELISA, and subunit antigen-specific titres are given as the reciprocal of the calculated sample dilution corresponding with an A492≥0·2 after subtraction of background values of PBS-treated animals. Titres are expressed as GMT±SD Mice receiving subunit antigen plus adjuvant showed significantly enhanced subunit antigen-specific antibody titres compared to animals receiving subunit antigen alone (P < 0·05). IgG1 responses observed in LTA(His)10 and LTA-E112K(His)10 treated animals were significantly lower than mice receiving LT, LT-E112K, or LTB as an adjuvant (P < 0·05).

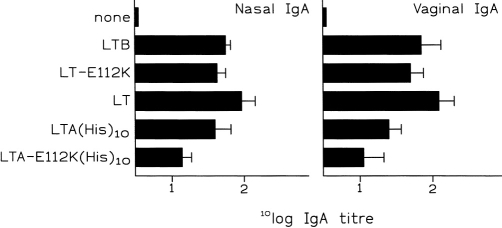

Next, we investigated the capacity of LTA(His)10 and LTA-E112K(His)10 to induce local antigen-specific S-IgA responses in mucosal secretions. Figure 5 shows that immunization with subunit antigen alone failed to induce S-IgA responses in mucosal lavage fluids. In the nasal cavity, coadministration of LTA(His)10 resulted in brisk subunit antigen-specific S-IgA responses, which were comparable in magnitude to responses observed after immunization with LT, LT-E112K, or LTB and subunit antigen. LTA(His)10 induced substantial antigen-specific S-IgA responses in vaginal lavage fluids as well (Fig. 5). LTA-E112K(His)10 stimulated subunit antigen-specific nasal and vaginal S-IgA responses as well, however, it was clearly the least efficient adjuvant, inducing significantly lower responses than LT, LT-E112K and LTB.

Figure 5.

Induction of influenza subunit antigen-specific mucosal S-IgA responses. Mice were immunized i.n. with subunit antigen alone, or in conjunction with either 2μg LTB, 2·9μg LT-E112K, 2·9μg LT, 9μg LTA(His)10, or 9μg LTA-E112K(His)10. Control animals were given PBS. For details see legend to Figure 4. Left-hand panel, nasal S-IgA; right-hand panel, vaginal S-IgA. All subunit antigen-specific S-IgA responses observed in lavage fluids of mice receiving subunit antigen plus an adjuvant were significantly different from mice receiving subunit antigen alone. Nasal subunit antigen-specific S-IgA titres in mice immunized with LTA-E112K(His)10, were significantly lower than those observed in mice given LTB, LT-E112K, LT, or LTA(His)10 plus subunit antigen (P < 0·05).

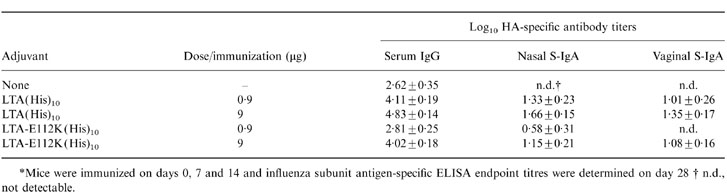

To demonstrate dose-dependency of the subunit antigen-specific responses induced by LTA(His)10 and LTA-E112K(His)10, separate groups of mice were immunized with 0·9 and 9μg of these proteins in conjunction with subunit antigen. Table 3 shows that especially LTA-E112K(His)10 was considerably less effective at the 0·9μg dose, the serum IgG response not being significantly different from the response induced by administration of subunit antigen alone. LTA(His)10 was also less effective at the 0·9μg than at the 9μg dose, however, strong stimulation of antigen-specific responses was still observed. This might indicate that ADP-ribosylation activity is involved in LTA-mediated adjuvanticity.

Table 3.

Dose–response adjuvant effect of LTA(His)10 and LTA-E112K(His)10 towards influenza subunit antigen*

*Mice were immunized on days 0, 7 and 14 and influenza subunit antigen-specific ELISA endpoint titres were determined on day 28 † n.d., not detectable.

From the above results we conclude that despite their low immunogenicity, both LTA(His)10 and LTA-E112K(His)10 have potent adjuvant activity. In addition, from the data obtained in the dose–response study, we conclude that ADP-ribosylation activity is non-essential, but involved, in adjuvanticity mediated by LTA(His)10. The data on the subunit-antigen-specific IgG subtypes induced by LT, LT-E112K, LTB, LTA(His)10 and LTA-E112K(His)10, clearly suggest that induction of Th2-type helper responses plays a critical role in the adjuvanticity of these molecules. Finally, we conclude that the adjuvant properties of LT reside on both the A and the B subunits.

DISCUSSION

The main conclusion from the results presented in this paper is that the isolated LTA subunit of LT can act as a potent adjuvant towards a nasally administered antigen, independent of ADP-ribosylation activity and association with the LTB pentamer. Analysis of IgG subtypes in serum revealed that LTA(His)10 and LTA-E112K(His)10 induced influenza subunit antigen-specific IgG1 and IgG2a antibodies, indicative of a mixed Th1/Th2 response. In contrast to their potent adjuvant properties, LTA(His)10 and LTA-E112K(His)10 were found to be poorly immunogenic. In combination with the observation that recombinant LTB also has potent adjuvant activity, we conclude that the adjuvant activity of LT holotoxin is based on the immunomodulatory properties of both the A and the B subunit.

The immunogenicity of LT, its close relative CT, and their subunits has been extensively investigated over the last two decades. The results from early studies suggested that all antitoxin antibodies and toxin-neutralizing antibodies are almost exclusively directed against the B subunit.29,30 Recently, it was shown that non-toxic LT mutants also induce toxin-neutralizing antibodies directed against the A subunit.23,24 Our current results corroborate the latter finding. LT-E112K stimulated an LTA-specific antibody response to the same extent as LT, indicating that upon nasal administration ADP-ribosylation is not critically involved in immune stimulation by LT. To our knowledge, the capacity of LTA alone to induce an antigen-specific mucosal S-IgA response has never been studied. It appeared that administration of either LTA(His)10 or LTA-E112K(His)10 failed to elicit antigen-specific responses. Thus, we conclude that for the induction of LTA-specific antibodies, LTA needs to be associated with the B pentamer. Alternatively, LTB may act as an adjuvant towards LTA.

We found LT, LT-E112K and LTB to induce strong LTA-and/or LTB-specific IgG1, IgG2a and IgG2b responses. While IgG1 is generally associated with Th2-type, IgG2a is mostly associated with Th1-type T-cell help.28 Thus, the IgG1/IgG2a ratio is a reflection of the relative contribution of each of the helper arms of T-cell-mediated immunity to the antigen-specific immunoglobulin response. Accordingly, our results are indicative of a mixed Th1/Th2 T-helper response upon immunization with LT and LT variants. These findings are consistent with studies showing that LT/CT and CTB/LTB are strong inducers of CD4+ T-cell responses, and mixed Th-cytokine profiles and IgG subtype responses.16,31–34 Importantly, neither of the above molecules was found to induce detectable amounts of IgE – characteristic of allergic responses – in serum.

The role of the A subunit in the adjuvant properties of LT and CT is a matter of considerable controversy. Early studies involving the use of commercially available CTB, contaminated with traces of CT holotoxin, have been misleading, in that they suggested that the B subunit is solely responsible for the adjuvant properties of the holotoxin. On the other hand, studies involving the adjuvant properties of recombinant LTB/CTB have been controversial as well. Whereas several investigators have found that these molecules do not have any adjuvant activity,7,11 recent studies by 9,10,25 and 35,36 have shown that recombinant CTB/LTB are indeed capable of stimulating antibody responses towards coadministered antigens, the adjuvant activity being mediated by the GM1-binding properties of these molecules.25,26

Recent observations have suggested an important role for the A subunit in adjuvanticity. Firstly, it was found that mutants with residual enzymatic activity are more potent immunogens and adjuvants than completely non-toxic mutants.16,19 Secondly, the outcome of immunization experiments with wild-type LT and non-toxic LT mutants was found to be dependent on the route of immunization, clearly demonstrating a difference in permissiveness between the nasal and oral routes.20 Accordingly, using the oral route, higher doses of the non-toxic mutants were required to achieve responses comparable to those obtained with wild-type toxin. Thirdly, we observed that an LT mutant which lacked GM1-binding activity, had excellent adjuvant properties, whereas the corresponding LTB mutant failed to function as an adjuvant.25,26 Finally,Ågren et al.37 demonstrated that a CTA1 fusion protein (CTA1-DD) retained adjuvanticity towards coadministered antigens, showing a direct adjuvant effect of the A subunit.

The results described in this paper show that recombinant LTA fusion proteins, with, or devoid of, ADP-ribosylation activity, can act as potent adjuvants towards coadministered influenza subunit antigen. Since we found LTA(His)10 to be a more potent adjuvant than LTA-E112K(His)10, ADP-ribosylation activity is likely to be involved. Judging from the subunit antigen-specific IgG subtype profiles induced by LT, LT-E112K, LTB, LTA(His)10, and LTA-E112K(His)10, all molecules induce mixed Th1/Th2-type responses. However, compared to the IgG subtype responses observed in the immunogenicity study, the response is clearly shifted towards IgG1, characteristic of Th2-type responses. This is in agreement with the studies of other workers showing that the mucosal immunoadjuvant effect of CT and LT is dependent on priming of CD4+ Tcells and production of Th2-type cytokine profiles,31,32,34,38 but independent of ADP-ribosylation activity.18

The exact mechanism by which the LTA variants presented in this paper induce mucosal immune responses remains obscure. Effects of LT/CT on isotype switching of B cells, antigen presentation by macrophages, up-regulation of costimulatory molecules on macrophages, uptake of luminal antigens, and induction of Th2-type responses have been described,2,3 and may also account for the adjuvant properties of these LT variants. From this study, it is clear that the adjuvant activity of LT resides on both the A and B subunits. It is likely that the exact mode of induction of mucosal immune responses by LTB and LTA is different. In this respect, it would be of interest to investigate more closely if these molecules induce different T-helper responses and/or cytokine profiles. Irrespective of the mechanisms involved, the current observation that LTA has potent adjuvant activity, has important implications for the use of LT and LT variants as adjuvants for locally administered vaccines.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank Drs W. G. J. Hol and I. K. Feil for stimulating discussions, and ample supply of the DEABAG substrate. We thank Dr R. Brands from Solvay Pharmaceuticals Inc., Weesp, the Netherlands for supplying us with influenza subunit material. This study was financially supported by Solvay Pharmaceuticals Inc. (sup-porting W.R.V.).

REFERENCES

- 1.McGhee JR, Mestecky J, Dertzbaugh MT, Eldridge JH, Hirasawa M, Kiyono H. The mucosal immune system: From fundamental concepts to vaccine development. Vaccine. 1992;10:75. doi: 10.1016/0264-410x(92)90021-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Snider DP. The mucosal adjuvant activities of ADP-ribosylating bacterial enterotoxins. Crit Rev Immunol. 1995;15:317. doi: 10.1615/critrevimmunol.v15.i3-4.70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.De Haan L, Verweij WR, Agsteribbe E, Wilschut J. The role of ADP-ribosylation and GM1-binding activity in the mucosal immunogenicity and adjuvanticity of the Escherichia coli heat-labile enterotoxin and Vibrio cholerae cholera toxin. Immunol Cell Biol. 1998;76:270. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1711.1998.00745.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Spangler BD. Structure and function of cholera toxin and the related Escherichia coli heat-labile enterotoxin. Microbiol Rev. 1992;56:622. doi: 10.1128/mr.56.4.622-647.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sears CL, Kaper JB. Enteric bacterial toxins: Mechanisms of action and linkage to intestinal secretion. Microbiol Rev. 1996;60:167. doi: 10.1128/mr.60.1.167-215.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hazama M, Mayumi-Aono A, Miyazaki T, Hinuma S, Fujisawa Y. Intranasal immunisation against herpes simplex virus infection by using a recombinant glycoprotein D fused with immunomodulating proteins, the B subunit of Escherichia coli heat-labile enterotoxin and interleukin-2. Immunology. 1993;78:643. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tamura S-I, Yamanaka A, Shimohara M, et al. Synergistic action of cholera toxin B subunit (and Escherichia coli heat-labile toxin B subunit) and a trace amount of cholera whole toxin as an adjuvant for nasal influenza vaccine. Vaccine. 1994;12:419. doi: 10.1016/0264-410x(94)90118-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Russell MW, Moldoveanu Z, White PL, Sibert GJ, Mestecky J, Michalek SM. Salivary, nasal, genital, and systemic antibody responses in monkeys immunized intranasally with a bacterial protein antigen and the cholera toxin B subunit. Infect Immun. 1996;64:1272. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.4.1272-1283.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.De Haan L, Verweij WR, Feil IK, et al. Non-toxic variants of the Escherichia coli heat-labile enterotoxin as mucosal immunogens and adjuvants. STP Pharma Sciences. 1998;8:75. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Verweij WR, De Haan L, Holtrop M, et al. Mucosal immunoadjuvant activity of the recombinant Escherichia coli heat-labile enterotoxin and its B subunit: Induction of systemic IgG and secretory IgA responses in mice by intranasal immunization with influenza surface antigen. Vaccine. 1998;20:2069. doi: 10.1016/s0264-410x(98)00076-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Blanchard TG, Lycke N, Czinn SJ, Nedrud JG. Recombinant cholera toxin B subunit is not an effective mucosal adjuvant for oral immunization of mice against Helicobacter felis. Immunology. 1998;93:22. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2567.1998.00482.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Holmgren J, Lycke N, Czerkinsky C. Cholera toxin and cholera toxin B subunit as oral-mucosal adjuvant and antigen vector systems. Vaccine. 1993;11:1179. doi: 10.1016/0264-410x(93)90039-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lycke N, Tsuji T, Holmgren J. The adjuvant effect of Vibrio cholerae and Escherichia coli heat-labile enterotoxins is linked to their ADP-ribosyltransferase activity. Eur J Immunol. 1992;22:2277. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830220915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Douce G, Turcotte C, Cropley I, et al. Mutants of Escherichia coli heat-labile toxin lacking ADP-ribosyltransferase activity act as nontoxic, mucosal adjuvants. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:1644. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.5.1644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dickinson BL, Clements JD. Dissociation of Escherichia coli heat-labile enterotoxin adjuvanticity from ADP-ribosyltransferase activity. Infect Immun. 1995;63:1617. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.5.1617-1623.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Douce G, Fontana M, Pizza M, Rappuoli R, Dougan G. Intranasal immunogenicity and adjuvanticity of site-directed mutant derivatives of cholera toxin. Infect Immun. 1997;65:2821. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.7.2821-2828.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yamamoto S, Takeda Y, Yamamoto M, et al. Mutants in the ADP-ribosyltransferase cleft of cholera toxin lack diarrheagenicity but retain adjuvanticity. J Exp Med. 1997;185:1203. doi: 10.1084/jem.185.7.1203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yamamoto S, Kiyono H, Yamamoto M, et al. A nontoxic mutant of cholera toxin elicits Th2-type responses for enhanced mucosal immunity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:5267. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.10.5267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Giuliani MM, Del Giudice G, Giannelli V, et al. Mucosal adjuvanticity and immunogenicity of LTR72, a novel mutant of Escherichia coli heat-labile enterotoxin with partial knockout of ADP-ribosyltransferase activity. J Exp Med. 1998;187:1123. doi: 10.1084/jem.187.7.1123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Douce G, Giuliani MM, Giannelli V, Pizza MG, Rappuoli R, Dougan G. Mucosal immunogenicity of genetically detoxified derivatives of heat-labile toxin from Escherichia coli. Vaccine. 1998;16:1065. doi: 10.1016/s0264-410x(98)80100-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Di Tommaso A, Saletti G, Pizza M, et al. Induction of antigen-specific antibodies in vaginal secretions by using a nontoxic mutant of heat-labile enterotoxin as a mucosal adjuvant. Infect Immun. 1996;64:974. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.3.974-979.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.De Haan L, Verweij WR, Feil IK, et al. Mutants of the Escherichia coli heat-labile enterotoxin with reduced ADP-ribosylation activity or no activity retain the immunogenic properties of the native holotoxin. Infect Immun. 1996;64:5413. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.12.5413-5416.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fontana MR, Manetti R, Giannelli V, et al. Construction of nontoxic derivatives of cholera toxin and characterization of the immunological response against the A subunit. Infect Immun. 1995;63:2356. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.6.2356-2360.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pizza M, Fontana MR, Giuliani MM, et al. A genetically detoxified derivative of heat-labile Escherichia coli enterotoxin induces neutralizing antibodies against the A subunit. J Exp Med. 1994;180:2147. doi: 10.1084/jem.180.6.2147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.De Haan L, Feil IK, Verweij WR, et al. Mutational analysis of the role of ADP-ribosylation activity and GM1-binding activity in the adjuvant properties of the Escherichia coli heat-labile enterotoxin towards intranasally administered keyhole limpet hemocyanin. Eur J Immunol. 1998;28:1243. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-4141(199804)28:04<1243::AID-IMMU1243>3.0.CO;2-E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.De Haan L, Verweij WR, Feil IK, et al. Role of GM1-binding in the mucosal immunogenicity and adjuvant activity of the Escherichia coli heat-labile enterotoxin and its B subunit. Immunology. 1998;94:424. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2567.1998.00535.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Feil IK, Reddy R, De Haan L, et al. Protein engineering studies of A-chain loop 47 of Escherichia coli heat-labile enterotoxin point to a prominent role of this loop for cytotoxicity. Mol Microbiol. 1996;20:823. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1996.tb02520.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mosmann TR, Coffman RL. Th1 and Th2 cells: Different patterns of lymphokine secretion lead to different functional properties. Annu Rev Immunol. 1989;7:145. doi: 10.1146/annurev.iy.07.040189.001045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lindholm L, Holmgren J, Wikstrom M, Karlsson U, Andersson K, Lycke N. Monoclonal antibodies to cholera toxin with special reference to cross-reactions with Escherichia coli heat-labile enterotoxin. Infect Immun. 1983;40:570. doi: 10.1128/iai.40.2.570-576.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Peterson JW, Hejtmancik KE, Markel DE, Craig JP, Kurosky A. Antigenic specificity of neutralizing antibody to cholera toxin. Infect Immun. 1979;23:774. doi: 10.1128/iai.24.3.774-779.1979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wilson AD, Bailey M, Williams NA, Stokes CR. The in vitro production of cytokines by mucosal lymphocytes immunized by oral administration of keyhole limpet hemocyanin using cholera toxin as an adjuvant. Eur J Immunol. 1991;21:2333. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830211007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hörnquist E, Lycke N. Cholera toxin adjuvant greatly promotes antigen priming of Tcells. Eur J Immunol. 1993;23:2136. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830230914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Takahashi I, Marinaro M, Kiyono H, et al. Mechanisms for mucosal immunogenicity and adjuvancy of Escherichia coli labile enterotoxin. J Infect Dis. 1996;173:627. doi: 10.1093/infdis/173.3.627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Okahashi N, Yamamoto M, Vancott JL, et al. Oral immunization of interleukin-4 (IL-4) knockout mice with a recombinant Salmonella strain or cholera toxin reveals that CD4 (+) Th2 cells producing IL-6 and IL-10 are associated with mucosal immunoglobulin A responses. Infect Immun. 1996;64:1516. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.5.1516-1525.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wu HY, Russell MW. Induction of mucosal and systemic immune responses by intranasal immunization using recombinant cholera toxin B subunit as an adjuvant. Vaccine. 1998;16:286. doi: 10.1016/s0264-410x(97)00168-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tochikubo K, Isaka M, Yasuda Y, et al. Recombinant cholera toxin B subunit acts as an adjuvant for the mucosal and systemic responses of mice to mucosally co-administered bovine serum albumin. Vaccine. 1998;16:150. doi: 10.1016/s0264-410x(97)00194-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ågren LC, Ekman L, Löwenadler B, Lycke NY. Genetically engineered nontoxic vaccine adjuvant that combines B cell targeting with immunomodulation by cholera toxin A1 subunit. J Immunol. 1997;158:3936. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Xu-Amano J, Aicher WK, Taguchi T, Kiyono H, McGhee JR. Selective induction of Th2 cells in murine Peyer’s patches by oral immunization. Int Immunol. 1992;4:433. doi: 10.1093/intimm/4.4.433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]