Abstract

Dendritic cells (DC) have an increasingly important role in vaccination therapy; therefore, this study sought to determine the migratory capacity and immunogenic function of murine bone-marrow (BM)-derived DC following subcutaneous (s.c.) and intravenous (i.v.) injection in vivo. DC were enriched from BM cultures using metrizamide. Following centrifugation, the low-buoyant density cells, referred to throughout as DC, were CD11chigh, Iab high, B7-1high and B7-2high and potently activated alloreactive T cells in mixed lymphocyte reactions (MLR). In contrast, the high-density cells expressed low levels of the above markers, comprised mostly of granulocytes based on GR1 expression, and were poor stimulators in MLR. Following s.c. injection of fluorescently labelled cells into syngeneic recipient mice, DC but not granulocytes migrated to the T-dependent areas of draining lymph nodes (LN). DC numbers in LN were quantified by flow-cytometric analysis, on 1, 2, 3, 5 and 7 days following DC transfer. Peak numbers of around 90 DC per draining LN were found at 2 days. There was very little migration of DC to non-draining LN, thymus or spleen at any of the time-points studied. In contrast, following i.v. injection, DC accumulated mainly in the spleen, liver and lungs of recipient mice but were largely absent from peripheral LN and thymus. The ability of DC to induce T-cell-mediated immune responses was examined using trinitrobenzenesulphate (TNBS)-derivatized DC (TNBS-DC) to sensitize for contact hypersensitivity responses (CHS) in naive syngeneic recipients. Following s.c. injection, as few as 105 TNBS-DC, but not TNBS-granulocytes, sensitized for CHS responses. However, the same number of TNBS-DC failed to induce CHS following i.v. injection. In summary, this study provides new and quantitative data on the organ specific migration of murine BM-derived DC following s.c. and i.v. injection. The demonstration that the route of DC administration determines the potency of CHS induction, strongly suggests that the route of immunization should be considered in the design of vaccine protocols using DC.

INTRODUCTION

The induction of primary immune responses requires the presentation of antigen by dendritic cells (DC) in specialized lymphoid tissue. DC in peripheral organs, the most studied being epidermal Langerhans cells (LC), are specialized for the uptake and presentation of antigen,1–3 but lack the high-level expression of surface molecules required for the interaction with, and activation of naive T lymphocytes.1,3,4 Antigen exposure induces changes in the epidermal microenvironment, leading to the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines and the associated changes in surface molecule expression on LC,5–7 which are important in the migration of LC from the skin to the T-lymphocyte-dependent areas of the draining lymph nodes (LN).8,9 During this migration, LC up-regulate the expression of a variety of surface molecules,1,10,11 which allows them to interact with and activate naive antigen-specific T lymphocytes.12

The description of techniques to generate large numbers of DC from human13,14 and murine15,16 precursors in vitro, has made the use of DC in vaccine therapies more practical. In mice, DC immunization therapies have demonstrated protection against tumours,17–19 viruses20 and bacteria.21 In the tumour models, peptide-pulsed murine bone-marrow (BM)-derived DC induced specific cytotoxic T lymphocyte (CTL) activity in vivo,17 protected against subsequent tumour challenge17,18 and in some studies could induce regression in established tumours.17 The induction of immunity following immunization with DC is likely to depend on a number of variables, including the route of administration, the homing pattern of the injected cells, the choice of antigen, and the maturation state of the DC. Indeed, the ability of antigen-pulsed BM-derived DC to induce antigen-specific tolerance,22,23 suggests a regulatory role for DC, about which more needs to be understood.

Though antigen-pulsed DC have been successfully used in animal models, and human trials are presently underway, much is still to be learned about the behaviour of BM-derived DC in vivo. In this study, the accumulation of DC in lymphoid and non-lymphoid organs was quantified, following their injection into syngeneic recipient mice by subcutaneous (s.c.) or intravenous (i.v.) injection. Immunization via these routes resulted in the migration of DC to draining LN following s.c. injection and to the spleen, liver, lungs following i.v. injection. To determine whether these divergent migration patterns would affect the induction of contact hypersensitivity (CHS) responses, hapten-derivatized DC were injected by both routes. While low numbers of derivatized DC potently sensitized for CHS following s.c. injection, they failed to do so after i.v. injection, suggesting that the targeting of DC to peripheral LN is the most efficient way of sensitizing for CHS. Hence, the route of DC administration should be considered as an important variable in the design of vaccine therapies.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Mice

Female C57BL/6 and BALB/c mice aged 4–5 weeks were purchased (Charles River, Sulzburg, Germany) and housed in the specific pathogen-free animal facility of the Max Planck Institute, Freiburg. All of the experimental procedures carried out were in accordance with the Max Planck Institute and the University of Freiburg guidelines on animal welfare.

Media and chemicals

RPMI-1640 (Gibco, Eggenstein, Germany) was supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal calf serum (FCS) (Gibco), 2 mm l-glutamine (Gibco), 25 mm HEPES buffer (Gibco) and 50 mg/ml penicillin–streptomycin (Gibco) (cRPMI). Trinitrobenzenesulphonic acid (TNBS) and 4-ethoxymethylene-2-phenyl-2-oxazolin-5-one (oxazolone) were purchased from Sigma Immunochemicals (Deisenhofen, Germany). Trinitrochlorobenzene was a kind gift from the Chemistry Department, University of Freiburg.

DC cultures

DC were generated following Inaba et al.,15,16 with minor alterations. BM was harvested from the tibia and femur of C57BL/6 mice (n=3–4). The cells were resuspended at 1×106 cells/ml cRPMI-1640 (Gibco) with 40 ng/ml recombinant murine granulocyte–macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF) (PromoCell, Heidelberg, Germany) and 100 ng/ml recombinant murine interleukin-4 (IL-4) (PromoCell). Cells were cultured in 1-ml aliquots in 24-well culture plates (Greiner, Frickenhausen, Germany). Cells were fed on days 3 and 5 of culture, by replacing half the medium in each well with fresh cRPMI with GM-CSF and IL-4. On day 3, non-adherent cells were aspirated off following gentle swirling of the plate. Loosely adherent cells, including DC, were harvested by gentle pipetting on day 6 of culture. DC were washed once and resuspended at ≈5×105 cells/ml in cRPMI. Eight- millilitre volumes of the cell suspension were underlayed with 2 ml 14·5% metrizamide (Boehringer Ingelheim, Heidelberg, Germany) in a 14-ml conical-bottomed tube (Becton Dickinson, Heidelberg, Germany) and centrifuged at room temperature (22°) for 20 min at 600 g. Both the low buoyant density cells, and the denser cells which formed a pellet were collected separately, washed twice, and resuspended for use.

Monoclonal antibodies (mAb)

Fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-conjugated mouse anti-mouse Iab antibody (AF6–120·1), rat anti-mouse B7-1 (IG10), B7-2 (GL-1), GR-1 (RB6-8CS) and MAC-3 (M3/84) were purchased from Pharmingen, Hamburg, Germany. Secondary staining was performed with a phycoerythrin (PE)-conjugated hamster-anti-mouse CD11c monoclonal (Pharmingen). FITC conjugated mouse immunoglobulin G (IgG) control, Rat IgG2a and PE conjugated hamster IgG (all from Pharmingen) were also used to assess background staining. Biotinylated rat anti-mouse CD3 (Dianova, Hamburg, Germany) and Cy™3-conjugated streptavidin (Dianova) or PE-conjugated hamster-anti-mouse CD3 (145–2C11, Pharmingen) were used for immunofluorescent labelling of frozen sections.

Immunostaining and flow cytometry

DC were incubated for 20 min at 4° with one of the FITC-conjugated monoclonals or the appropriate isotype control. The cells were then washed once with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and incubated for 20 min with PE-labelled anti-mouse CD11c, or PE-labelled hamster IgG. Following a final wash the cells were analysed with a fluorescence-activated cell sorter (FACscan, applying Cellquest research software; Becton Dickinson). Dead cells were excluded by gating out 7-aminoactinomycin (7-AAD) (Sigma Immunochemicals)-positive cells and a total of 104 live cells were analysed.

Primary mixed lymphocyte responses

Single LNC suspensions were prepared by mechanical disaggregation of peripheral LN (auricular, brachial, inguinal, popliteal) from BALB/c mice (n=3–4). This population, which contained ≤80% CD3+ T cells, was plated at 105 cells/well in 96-well round-bottomed plates (Greiner). DC were enriched from C57BL/6-BM cultures on day 6 and used as stimulator cells at concentrations of 104, 1×103, 1×102 cells/well. Plates were cultured for 6 days at 37° in a humidified atmosphere containing 5% CO2, [3H]dThd (1 μCi) was added for the last 18 hr of culture. Plates were harvested with a Canberra Packard Filter Mate (Canberra Packard, Frankfurt, Germany) and incorporation of [3H]dThd was determined by liquid scintillation spectroscopy using a TopCount (Canberra Packard).

In vivo migration

DC were enriched from BM cultures on day 6 by metrizamide centrifugation. Both DC and granulocytes were labelled with PKH2-GL (Sigma Immunochemicals) green fluorescent dye in accordance with the manufacturer’s instructions. Briefly, cells were washed twice in PBS, and resuspended in a 2×10−6 m solution of PKH2 for 5 min at room temperature. Following incubation, labeling was stopped by the addition of an equal volume of FCS for 1 min and then an equal volume of cRPMI was added prior to washing. Following a second wash in cRPMI, the cells were washed three times in serum free PBS and 20 μl containing 0·5–6×105 cells were injected s.c. into both the hind footpads of mice (n=5 per group). After 1–7 d the popliteal, inguinal and auricular LN (n=9) along with spleens and thymi (n=3) were removed. The viability of in vitro cultured PKH-2GL-labelled DC was similar to that of unlabelled DC throughout the course of the experiment (1–7 days) as determined by trypan blue exclusion and FACS analysis of propidium iodide staining. One popliteal, inguinal or auricular LN, plus the spleen, thymus, liver and rear footpad skin from each group were snap frozen and stored at −80° prior to cryosectioning for immunohistological analysis. To examine DC migration following i.v. injection, 106 labelled DC in 100 μl PBS were injected into the tail vein of mice (n=5), 24 and 48 hr later spleen, liver, lungs, peripheral LN and thymus were removed and pooled for each group. A single cell suspension from pooled organs was prepared by mechanical disaggregation, DC were enriched from these suspensions using metrizamide, and fluorescent cells were analysed using a FACScan (Becton Dickinson) as above. In some experiments spleen cell suspensions were prepared in accordance with Crowley et al.24 using collagenase type III (Sigma Immunochemicals). Data are expressed as total DC per million organ cells.

Induction of CHS responses

DC-enriched and depleted populations were prepared from day 6 BM cultures using metrizamide centrifugation. Cells were washed twice in serum-free PBS and incubated with 1 mm TNBS at 37° for 15 min. The cells were washed twice in cRPMI and twice with PBS alone. Cells were then resuspended in PBS and 20 μl containing 0·25–3×105 cells were injected s.c. into two sites on the shaved abdomen of C57BL/6 mice (n=5). For i.v. injections 105 cells were injected in 100 μl PBS into the tail vein. Positive and negative control mice (n=5) were painted on the abdomen with 100 μl of 7% TNCB or vehicle (4:1 acetone:olive oil), respectively. Five days later the ears of all mice were measured with an engineer’s micrometer (Mitutoya, Japan) prior to challenge on the dorsum of both ears with 1% TNCB in vehicle. The mean increase in ear thickness±SEM (n=10) 24 and 48 hr following challenge were measured.

Statistics

Differences in the mean values among treatment groups was determined using an unpaired Student’s t-test in Sigmastat 1.0 for the PC (SPSS Software, Munich, Germany).

RESULTS

Metrizamide density gradient centrifugation renders highly purified DC from BM-cultures

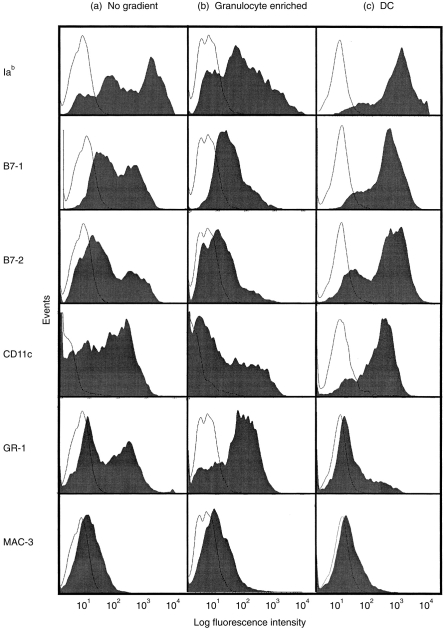

As reported previously15,16 the incubation of murine BM cells with GM-CSF and IL-4 results in the induction of cells with dendritic cell morphology and phenotype. Following culture of murine BM cells in GM-CSF and IL-4 a heterogeneous cell population was observed (Fig. 1a). Metrizamide density gradient centrifugation of these cells resulted in the separation of two distinct populations. The majority of cells in the denser population were granulocytes, with the phenotype Iab low, B7-1low, B7-2low, CD11clow, GR-1high and Mac-3low (Fig. 1b). In contrast, the low-buoyant density cell population were predominantly (routinely >80%) Iab high, B7-1high, B7-2high, CD11chigh, Gr-1low and Mac-3negative (Fig. 1c), and were designated DC. In order to further characterize the two populations, their MLR stimulatory capacity was compared (see Materials and Methods). Dendritic cells induced significantly (P=0·01) higher proliferative responses than granulocytes (data not shown). Thus, 25×104 c.p.m. were measured when 1×105 BALB/c lymph node cells were incubated with 1×104 C57BL/6 BM-DC whereas only 1·5×104 c.p.m. were measured when C57BL/6 granulocytes were used as antigen-presenting cells (APC) in an MLR.

Figure 1.

Metrizamide enriches DC from heterogeneous GM-CSF and IL-4-treated BM-cultures. Cells were harvested directly from day 6 BM-cultures (a), or were separated into high-density (b) or low-buoyant density (c) cell populations by metrizamide. The expression of Iab, B7-1, B7-2, CD11c, GR-1 and MAC-3 (filled symbols) along with the appropriate isotype control (open symbols) on each population was analysed by flow cytometry.

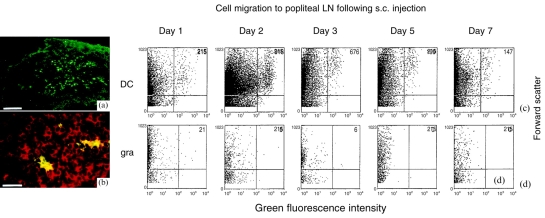

Following s.c. injection DC migrate to local LN

To compare their in vivo migration following adoptive transfer, DC and granulocytes were fluorescently labelled with a green dye (PKH2-GL, Sigma) prior to s.c. or i.v. injection. DC (green) were observed in frozen sections of draining (popliteal) LN removed 48 hr after s.c. injection of DC into the footpads of mice (Fig. 2a). Double labelling of the sections with a Cy™3-labelled anti-CD3 monoclonal antibody (red), confirmed that the DC migrate to the T-cell area of LN and showed that the DC were in close association with T cells (Fig. 2b).

Figure 2.

BM-DC migrate to the T-cell area of draining LN following s.c. injection into syngeneic recipients. DC and granulocytes were labelled with PKH2-GL green fluorescent dye (Sigma). Following extensive washing in RPMI and then PBS, 6×105 cells were injected s.c. into the hind footpads of syngeneic recipient mice (n=3). After 48 hr draining LN were removed, snap frozen and cryosectioned for immunohistochemical analysis. (a) A LN with fluorescently labelled DC, white bar=200 mm. (b) T lymphocytes were visualized using biotinylated rat-anti-mouse CD3 and Cy™3-conjugated streptavadin (red), white bar=50 mm. (c, d) After 1–7 days the popliteal LN (n=9) were removed. A single-cell suspension from pooled organs was prepared by mechanical dissaggregation, DC were enriched from these suspensions using metrizamide, and their fluorescence intensity (x-axis) and forward scatter (y-axis) was analysed. (c) The time-course of DC migration to draining LN following intradermal injection. (d) The migration of s.c. injected granulocytes to the draining LN.

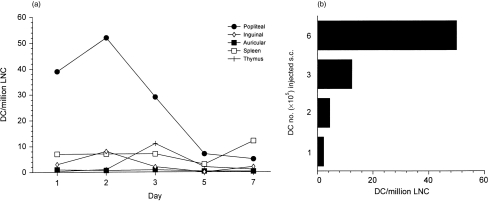

Flow-cytometry was used to quantify the migration. Because of the low numbers of labelled cells accumulating in LN, single cell suspensions from pooled lymph nodes were first enriched for DC using metrizamide. Fluorescently stained cells were limited to the low-buoyant density layer following this enrichment (data not shown). DC were observed in popliteal lymph nodes 24 hr (the earliest time-point examined) following s.c. injection into footpads, DC numbers peaked at 48 hr and rapidly declined to background levels by day 5 following transfer (Fig. 2c). In contrast, the granulocyte population did not migrate to LN at any time-point following s.c. injection (Fig. 2d). The number of DC in pooled organs was divided by the total cell number to give the number of DC/million cells (Fig. 3a). It can be seen that DC migrate specifically to draining LN, but were largely absent from distant non-draining (auricular and inguinal) LN, the spleen or thymus. The numbers of DC in draining LN peaked on day 2 following transfer at around 52 DC/million cells (Fig. 3a) which corresponds to around 90 labelled DC/LN. In two further experiments between 90 and 100 DC/LN were present on day 2 following DC injection (data not shown). The dose dependency of the system was analysed in order to determine whether migration was optimal. The 48 hr time-point after injection was examined as this is the time-point for peak DC numbers in LN. It can be seen that DC migration was fully dose dependent (Fig. 3b).

Figure 3.

DC home in a time-and dose-dependent manner to draining LN. In (a) 6×105 labelled DC were injected s.c. into the hind footpads of syngeneic recipient mice (n=5). After 1–7 days the popliteal, inguinal and auricular LN (n=9) along with spleens and thymi (n=3) were removed and a single-cell suspension was prepared from pooled organs by mechanical dissaggregation. DC were enriched from these suspensions using metrizamide, and the number of fluorescent cells was analysed. (a) The timecourse of DC migration, expressed as DC per million cells, to lymphoid organs following s.c. injection. (b) Labelled DC at the indicated concentration were injected s.c. into the hind footpads of syngeneic recipient mice (n=5 per group). After 48 hr, single cell suspensions from popliteal LN (n=10 per group) were prepared. DC numbers were analysed by flow cytometry and the results expressed as DC per million LNC.

To confirm if the levels of DC migration observed in the LN reflected a failure of BM-DC to migrate out of the skin, samples were taken for cryosectioning, from sites of DC injection. Footpad skin from sites injected with green-labelled DC showed intense fluorescence (data not shown), suggesting that a large number of DC were trapped at the injection site.

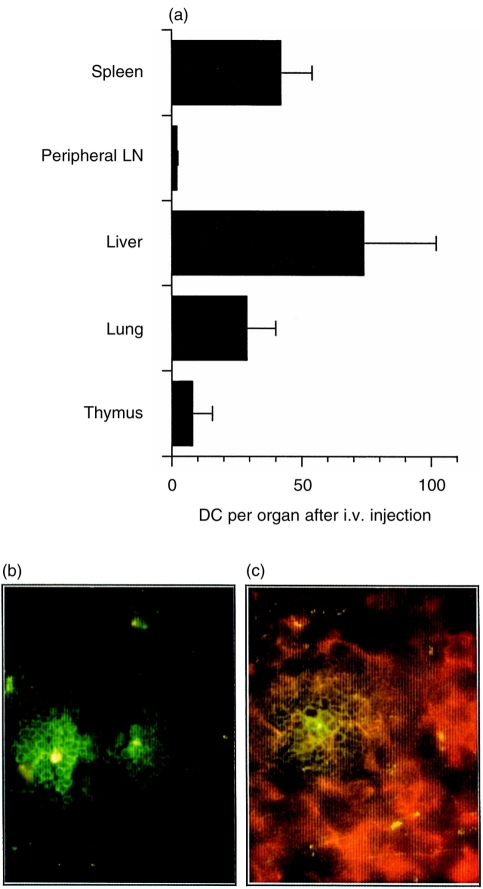

The homing of spleen DC to the spleen following i.v. injection has been described.25 It was therefore of interest to determine whether following i.v. injection BM-derived DC show the same tissue distribution. Therefore, labelled BM-DC were injected i.v. and organs taken 24, 48 and 72 hr later. Unlike the s.c. route, i.v. administration results in the migration of BM-DC to the spleen, liver and lungs, but not to peripheral LN or the thymus at the 24 hr time-point (Fig. 4a), or at the other time-points studied (data not shown). Similar numbers of labelled DC were isolated whether or not spleens were collagenase treated (data not shown). Immunohistological analysis revealed migration of the i.v. injected DC to spleen (Fig. 4b), lung and liver (data not shown) confirming the results of the flow cytometric analysis. No DC were detected in the thymus. As observed for s.c. injected DC (Fig. 2a,b), i.v. injected DC also homed to the T-cell areas in the spleen, as shown in Fig. 4(c).

Figure 4.

DC accumulate in the spleen, liver and lung following i.v. injection. (a) DC were labelled with PKH2-GL and 1×106 cells were injected i.v. into two mice. After 24 hr, spleens, peripheral LN (n=24), livers, lungs and thymi were pooled and a single-cell suspension produced. DC numbers were analysed by flow cytometry and the results expressed as DC per organ±SD from two separate experiments. (b, c) Spleen was snap-frozen 48 hr after i.v. injection of PKH2-GL labelled DC. Cryosections were left untreated (b) or stained with PE-conjugated anti-CD3 antibody (c). Staining specificity was confirmed with a PE-conjugated isoptype control antibody (not shown).

The capacity of DC to induce CHS

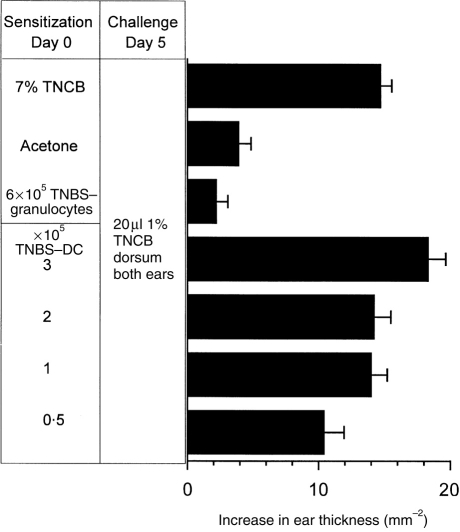

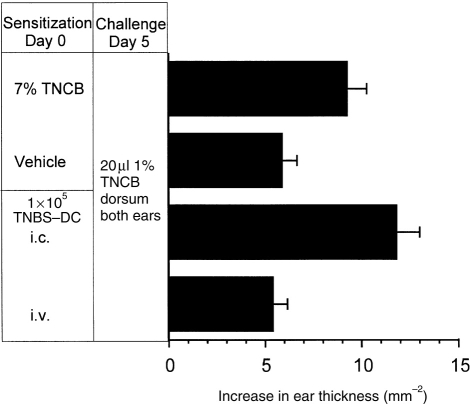

Having demonstrated the ability of BM-derived DC to migrate in vivo, it was of interest to determine whether these DC could sensitize T-cell-mediated immune responses. To do this BM-DC were incubated with TNBS, following which the hapten is present on the cell surface in an immunogenic form. Following s.c. injection TNBS-DC induce CHS responses to TNCB in naive syngeneic recipient mice (Fig. 5). The CHS sensitization by DC was of a similar magnitude to that induced by a standard skin sensitization protocol with TNCB (Fig. 5). Injection of unmodified DC did not sensitize for CHS (not shown). In addition, responses were antigen specific, as mice sensitized with 3×105 TNBS-derivatized DC, failed to respond to challenge with 1% oxazolone (data not shown). As few as 1×105 DC were able to induce CHS following s.c. injection (Fig. 5). By contrast, even 6×105 TNBS-granulocytes failed to induce CHS upon s.c. injection into syngeneic recipient mice (Fig. 5). To compare the importance of the route of immunization in the induction of CHS a limiting number (1×105 cells) of TNBS-DC were injected by the s.c. or i.v. routes, as in the previous figure (Fig. 5) the s.c. injection of 105 TNBS-DC induced CHS, however, the same number of TNBS-DC failed to do so when they were administered i.v (Fig. 6).

Figure 5.

TNBS derivatized BM-DC but not granulocytes induce CHS responses to naive syngeneic recipients. DC and granulocytes were incubated with 1 mm trinitrobenzenesulphate (TNBS) at 37° for 15 min. Following extensive washing with cRPMI and then PBS, cells were resuspended in PBS and various concentrations of cells were injected s.c. into the shaved abdomen of C57BL/6 mice (n=5). Positive and negative control mice (n=5) were painted on the abdomen with 100 ml of 7% Trinitrochlorobenzene (TNCB) or vehicle (4:1 acetone:olive oil), respectively. Five days later the ears of all mice were measured prior to challenge on the dorsum of both ears with 20 μl 1% TNCB in vehicle. The graph shows data for the 24 hr timepoint as the mean increase in ear thickness±standard error mean (SEM) (n=10).

Figure 6.

DC induce CHS following s.c. but not i.v. administration. DC were derivatized with TNBS, and following extensive washing, 105 cells were injected s.c. or i.v. into naive syngeneic C57BL/6 recipient mice (n=5). Positive and negative control mice (n=5) were painted on the abdomen with 100 μl of 7% TNCB or vehicle (4:1 acetone:olive oil), respectively. CHS responses were elicited on day 5, the mean increase in ear thickness±SEM for the 24 hr time-point are shown.

DISCUSSION

Murine BM-derived DC have been used successfully to immunize mice against tumours, viral antigens and bacterial infections.17–21 However, though the priming of immune responses requires antigen to be presented by DC to T lymphocytes within specialized lymphoid tissues, the migratory capacity of murine BM-derived DC in vivo has not been thoroughly investigated.

Following the culture of BM cells with GM-CSF and IL-4, first described in 15 and 16. Thirty to 50% of cells showed DC morphology and phenotype. In order to obtain a more homogeneous DC population, low buoyant density cells were enriched from these cultures using metrizamide centrifugation. Typically over 80% of the low buoyant density cell population were Iab high, B7-1high, B7-2high and CD11chigh, and potently stimulated MLR, thus resembling mature murine DC.1,4 In contrast, the DC-depleted high density population showed reduced levels of CD11c+ cells, and contained predominantly Iab low, B7-1low B7-2low and GR-1high granulocytes. The inability of this population to stimulate alloresponses confirms that DC contamination was low.

Previous studies have reported the ability of fluorescently labelled chimpanzee BM-derived DC26 and murine spleen-derived DC,27 to migrate to draining LN following cutaneous administration. In this study we were interested to expand the data for murine BM-derived DC, to examine the effect of route of administration on organ-specific migration and to determine whether the route of administration could affect the ability of DC to induce T-lymphocyte-mediated immunity in a CHS model. In addition, the previous studies were semiquantitative, in that DC numbers were counted on frozen sections, here in contrast the total labelled DC population from organs was analysed, providing truly quantitative data on the numbers and kinetics of DC migration. Following s.c. injection into the footpad, DC migrated specifically to the T-cell-dependent areas of draining LN. By contrast, after i.v. injection DC were observed in the spleen, liver and lungs but not in peripheral LN, possibly reflecting reticular endothelial trapping rather than active migration. The ability of DC but not of granulocytes to migrate to draining LN suggests that the migration is an active process specific to DC, rather than (i) the passive flow of labelled cells to the lymph node via the afferent lymph, (ii) the leakage of dye directly into the afferent lymph resulting in the labelling of resident cells in the LN; or (iii) the uptake of fluorescent fragments by host APC which subsequently migrate to draining LN. The time-course of migration in mice following s.c. injection is similar to that seen in chimpanzees, with peak numbers of DC in LN 48 hr following transfer,26 but contrasts with results seen with murine-spleen-derived DC, where peak DC numbers in lymph nodes were observed 24 hr after the transfer.27 The migration of BM-DC to the spleen following i.v. injection is in agreement with a previous study where murine splenic DC were used.25

To confirm that the DC migration observed in this study was functionally significant, the ability of haptenized DC and granulocytes to sensitize CHS responses in syngeneic recipient mice was examined. The administration of as few as 105 TNBS-DC by the s.c. route potently induced CHS, giving responses of a similar magnitude to those observed following skin painting with TNCB. The granulocyte population, which was not observed in LN following s.c. injection, failed to sensitize CHS responses, even following the injection of up to 6×105 TNBS-modified cells. In order to determine whether the route of DC administration was important in the induction of CHS, a limiting number of TNBS-DC (105 cells) were injected into the tail vein. In contrast to s.c. injection, 105 TNBS-DC given i.v. failed to induce CHS responses. This suggests that the migration of DC to skin-draining LN following s.c. injection is important in the induction of cutaneous immune responses.

The efficiency of CHS induction by the s.c. route, compared with the i.v. route, reflects the need for the expansion of antigen-specific T cells in skin-draining lymph nodes in cutaneous immune responses. In contrast, immunity against lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus (LCMV), measured by assaying viral titres in the spleen, is induced more efficiently by LCMV-peptide bearing GP33-DC injected i.v. rather than s.c.28 Indeed, the injection of just 102 GP33-DC directly into the spleen induced antiviral protection.28

As would be expected from their ability to vaccinate mice against a variety of antigens,17–21 murine BM-derived DC migrate to specialized lymphoid tissues on transfer into recipient mice. Here we provide evidence that the differential migration of BM-derived DC following their administration by either the s.c. or i.v. routes is reflected by their potency to induce CHS, a cutaneous T-cell-mediated immune response. Therefore, the route of DC administration should be considered an important variable when designing DC vaccination strategies.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Professors Hanspeter Pircher and Hans Ulrich Weltzien for critically reading the manuscript and Käthe Thoma for help with immunohistology. This work was supported by a grant from the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft

Abbreviations

- BM

bone marrow

- CHS

contact hypersensitivity

- DC

dendritic cell

- GM-CSF

granulocyte–macrophage colony-stimulating factor

- s.c.

subcutaneous

- LC

Langerhans cell

- LN

lymph node

- LNC

lymph node cell

- MFI

mean fluorescence intensity

References

- 1.Schuler G, Steinman RM. Murine epidermal Langerhans cells mature into potent immunostimulatory dendritic cells in vitro. J Exp Med. 1988;161:526. doi: 10.1084/jem.161.3.526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Romani N, Koide S, Crowley M, et al. Presentation of exogenous protein antigens by dendritic cells to T cell clones. Intact protein is presented best by immature, epidermal Langerhans’ cells. J Exp Med. 1989;169:1169. doi: 10.1084/jem.169.3.1169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cella M, Salusto F, Lanzavecchia A. Origin, maturation and antigen presenting function of dendritic cells. Curr Op Immunol. 1997;9:10. doi: 10.1016/s0952-7915(97)80153-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Streilein JW, Grammer SF. In vitro evidence that Langerhans’ cells can adopt two functionally distinct forms capable of antigen presentation to T lymphocytes. J Immunol. 1989;143:3925. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cumberbatch M, Dearman RJ, Kimber I. Langerhans’ cells require signals from both tumour necrosis factor-α and interleukin-1 for migration. Adv Exp Med Biol. 1997;417:125. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4757-9966-8_21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Weiss JM, Sleeman J, Renkl AC, et al. An essential role for CD44 varient isoforms in epidermal Langerhans’ cell and blood dendritic cell function. J Cell Biol. 1997;137:1137. doi: 10.1083/jcb.137.5.1137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Price AA, Cumberbatch M, Kimber I, Ager A. α6 integrins are required for Langerhans’ cell migration from the epidermis. J Exp Med. 1997;186:1725. doi: 10.1084/jem.186.10.1725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Larsen CP, Steinman RM, Witmer-Pack MD, Hankins DF, Morris PJ, Austyn JM. Migration and maturation of Langerhans’ cells in skin transplants and explants. J Exp Med. 1990;172:1483. doi: 10.1084/jem.172.5.1483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fossum S. Lymph-borne dendritic leukocytes do not recirculate but enter the lymph node paracortex to become interdigitating cells. Scand J Immunol. 1988;27:97. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3083.1988.tb02326.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Romani N, Lenz A, Glassel H, et al. Cultured human Langerhans’ cells resemble lymphoid dendritic cells in phenotype and function. J Invest Dermatol. 1989;93:600. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12319727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cumberbatch M, Gould SJ, Peters SW, Kimber I. MHC class II expression by Langerhans’ cells and lymph node dendritic cells: possible evidence for maturation of Langerhans’ cells following contact sensitivity. Immunology. 1991;74:414. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Steinman RM. The dendritic cell system and its role in immunogenicity. Ann Rev Immunol. 1991;9:271. doi: 10.1146/annurev.iy.09.040191.001415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Caux C, Dezutter-Dambuyant C, Schmitt D, Banchereau J. GM-CSF and TNF-α co-operate in the generation of dendritic Langerhans’ cells. Nature. 1992;360:258. doi: 10.1038/360258a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Santiago-Schwarz F, Divaris N, Kay C, Carsons SE. Mechanisms of tumor necrosis factor-granulocyte–macrophage colony-stimulating factor-induced dendritic cell development. Blood. 1993;82:3019. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Inaba K, Inaba M, Romani N, et al. Generation of large numbers of dendritic cells from mouse bone marrow cultures supplemented with GM-CSF. J Exp Med. 1993;176:1693. doi: 10.1084/jem.176.6.1693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Inaba K, Inaba M, Hagi K, et al. Granulocytes, macrophages and dendritic cells arise from a common major histocompatability complex class II-negative progenitor in mouse bone marrow. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:3038. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.7.3038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mayordomo JI, Zorina T, Storkus WJ, et al. Bone marrow-derived dendritic cells pulsed with syngeneic tumour peptides elicit protective and therapeutic antitumour immunity. Nature Med. 1996;1:1297. doi: 10.1038/nm1295-1297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Porgador A, Snyder D, Gilboa E. Induction of antitumour immunity using bone marrow-generated dendritic cells. J Immunol. 1996;156:2918. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.De Tuting T, Leo AB, Lotze MT, Storkus WJ. Genetically modified bone marrow-derived DC expressing tumor-associated viral or ‘self’ antigens induce antitumor immunity in vivo. Eur J Immunol. 1997;27:2702. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830271033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.De Bruijn MLH, Schuurhuis DH, Vierboom MPM, et al. Immunization with human papillomavirus type 16 (HPV16) oncoprotein-loaded dendritic cells as well as protein in adjuvant induces MHC class I-restricted protection to HPV16-induced tumor cells. Cancer Res. 1998;58:724. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mbow ML, Zeidner N, Panella N, Titus RG, Piesman J. Borellia burgdorferi-pulsed dendritic cells induce a protective immune response against tick-transmitted spirochetes. Infect Immun. 1997;65:3386. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.8.3386-3390.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Finkleman FD, Lees A, Birnbaum R, Gause WC, Morris SC. Dendritic cells can present antigen in vivo in a tolerogenic or immunogenic fashion. J Immunol. 1996;157:1406. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Steptoe RJ, Thompson AW. Dendritic cells and tolerance induction. Clin Exp Immunol. 1996;105:397. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2249.1996.d01-779.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Crowley M, Inaba K, Witmer-Pack M, Steinman RM. The cell surface of mouse dendritic cells from different organs including thymus. Cell Immunol. 1989;118:108. doi: 10.1016/0008-8749(89)90361-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Austyn JM, Kupiec-Weglinski JW, Hankins DF, Morris PJ. Migration patterns of dendritic cells in the mouse: Homing to T cell dependent areas of spleen and binding in marginal zone. J Exp Med. 1988;167:646. doi: 10.1084/jem.167.2.646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Barrat-Boyes SM, Watkins SC, Finn OJ. In vivo migration of dendritic cells differentiated in vitro. A chimpanzee model. J Immunol. 1997;158:4543. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ingulli EA, Mondino A, Khoruts., Jenkins MK. In vivo detection of dendritic cell antigen presentation to CD4+ T cells. J Exp Med. 1997;185:2133. doi: 10.1084/jem.185.12.2133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ludewig B, Ehl S, Karrer U, Odermatt B, Hengartner H, Zinkernagel RM. Dendritic cells induce protective antiviral immunity. J Virol. 1998;72:3812. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.5.3812-3818.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]