Abstract

Previous studies in this laboratory have shown that mice with a gene disruption to the intracellular adhesion molecule-1 (ICAM-K/O) express normal cell-mediated immunity but cannot mount delayed-type hypersensitivity reactions following Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection. However, even in the absence of any appreciable granuloma formation, these mice control bacterial growth for at least 90 days. While not required to control the infection initially, we hypothesized that granuloma formation was required to control chronic infection, acting by surrounding infected cells to prevent bacterial dissemination. To test this, ICAM-1 knockout mice were infected with a low dose aerosol of M. tuberculosis Erdman and were found to succumb to infection 136±30 days later, displaying highly elevated bacterial loads compared to wild-type mice. Lung tissue from ICAM-K/O mice displayed extensive cellular infiltration and widespread tissue necrosis, but no organized granulomatous lesions were evident, whereas the control mice displayed organized compact granulomas. These data demonstrate that while a granulomatous response is not required initially to control M. tuberculosis infection, absence of granulomas during chronic infection leads to increased bacterial growth and host death. Thus these data support the hypothesis that granuloma formation is required to control chronic infection, acting by surrounding and walling off sites of infection to prevent bacterial dissemination and maintain a state of chronic infection.

INTRODUCTION

Immunity to Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection involves the induction of a cell-mediated immune response, whereby interferon-γ (IFN-γ) -producing T cells activate the anti-bacterial defence mechanisms of infected macrophages to destroy, or at least contain, mycobacterial growth.1–4 Arising concurrently with this cell-mediated immune response is the development of a delayed-type hypersensitivity (DTH) reaction, which leads to the influx of blood-borne monocytes into the infected tissue and subsequent granuloma formation.5–7

The C57BL/6 inbred mouse strain is resistant to M. tuberculosis infection and survives for much of its median lifespan after noculation.8,9 Following low-dose aerosol infection these mice generate both a strong T helper type 1 (Th-1) cell-mediated immune response and a strong DTH response.10 A chronic disease state ensues, with extensive granuloma formation in the lungs, although bacterial load remains constant for over 200 days. As the mice age however, disease severity increases, characterized by an increase in bacterial load and progressive degeneration of infected tissue, leading to the death of the host at about 300–350 days post-infection.8

Similarly, intracellular adhesion molecule-1 exon 5 gene-disrupted (ICAM-K/O) mice,11 back-crossed on to the resistant C57BL/6 background, also generate a strong Th-1 type cell-mediated immune response to M. tuberculosis infection.12 These mice demonstrate normal control of bacterial growth during the first 90 days of infection, producing equivalent levels of interleukin-12 (IL-12) and IFN-γ as the wild-type controls.

While both control and ICAM-K/O mice at first exhibit some degree of interstitial pnuemonitis, the extensive influx of mononuclear cells that occurs over the first 60 days or so of the infection in control mice, leading to formation of organized granulomas, is not observed in the gene-disrupted mice, even though over this period of time there is clearly adequate control of the bacterial infection.12

As a result of this information, we have hypothesized12 that protective immunity and the DTH response which leads to granuloma formation are separate components of the overall cell-mediated response, with the latter not essential for adequate control and containment of the infection.

What remains unclear however, is whether granuloma formation during the chronic phase of the pulmonary infection is needed to keep the bacterial load stable and to prevent late-term bacillus growth. To test this, we followed the course of infection during the chronic phase of the disease after a low-dose aerosol exposure with virulent M. tuberculosis. The results reveal that gene-disrupted mice undergo a surge in bacterial numbers 100–130 days post-exposure, leading to lung tissue destruction and death. These data support the hypothesis that while the DTH component of the cell-mediated immune response to M. tuberculosis is not essential to the expression of initial protective immunity, walling off bacteria during the chronic phase of the disease is required to prevent increased bacterial growth and subsequent lung damage.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Mice and bacterial infection

Six- to eight-week-old female ICAM-1 gene knockout (ICAM-K/O) mice and their C57BL/6 wild-type controls were purchased from Jackson Laboratories, Bar Harbor, ME. Knockouts were generated by targeted gene disruption of exon 5 introduced into C57BL/6/129 blastocyts.11 Heterozygous mice (+/–) were then back-crossed to C57BL/6 for 10 generations. Mice were infected with ≈100 M. tuberculosis Erdman using a Middlebrook Airborne Infection apparatus (Middlebrook, Terre Haute, IN) as previously described.13 The numbers of viable bacteria in the lung, spleen and liver were determined at the time-points indicated by plating serial dilutions of organ homogenates on nutrient Middlebrook 7H11 agar and counting bacterial colonies after 21 days of incubation at 37°. The data are expressed as the log10 value of the mean number of bacteria recovered per organ (n=4 animals).

Histology

Tissues, from four mice per experimental group, were infused with fresh 10% formaldehyde in phosphate-buffered saline. Sections made from paraffin blocks were stained with haematoxylin and eosin. Consecutive sections were stained for acid-fast bacilli by the Kinyoun staining procedure. Sections were analysed by a veterinary pathologist without prior knowledge of the experimental groups.

RESULTS

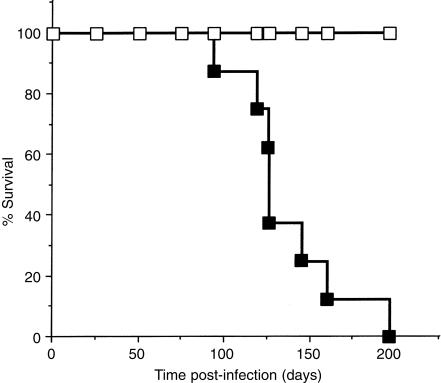

ICAM-K/O mice succumb to M. tuberculosis infection whereas wild-type mice survive

Wild-type and ICAM-K/O mice were infected via aerosol with ≈100 M. tuberculosis Erdman bacilli. At 30 days post-infection four mice per group were killed and bacterial load and lung histology were analyzed. As has been previously reported,12 bacterial numbers in the lungs of wild-type and K/O mice were equivalent (wild-type; 5·66±0·10, ICAM-K/O; 5·67±0·12). Histological examination of the lungs revealed a developing granulomatous response in the wild-type mice with epithelioid macrophages and lymphocytes forming compact granulomatous lesions. ICAM-K/O mice showed no evidence of macrophage influx with only limited lymphocyte perivascular cuffing (data not shown). The experiment was then extended to determine the effects of longer term chronic M. tuberculosis infection. Infected mice were examined daily for signs of deterioration. ICAM-K/O mice began to die after 94 days, with a mean survival time of 136±30 days (Fig. 1). All wild-type mice survived beyond 270 days post-infection.

Figure 1.

Survival of M. tuberculosis infected ICAM-K/O mice. Wild-type (□) and ICAM-K/O (▪) mice were infected with ≈100 bacilli via aerosol. Mice were monitored daily for signs of deterioration and moribund mice were killed. Data represent eight mice per group. Mean survival time for ICAM-K/O mice was 136 days and for wild-type mice >270 days.

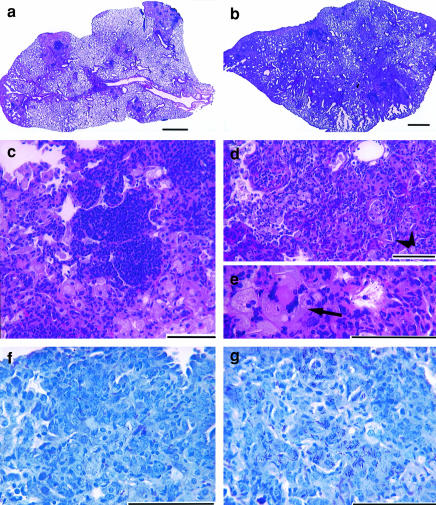

ICAM-K/O mice show cellular influx without defined granuloma formation

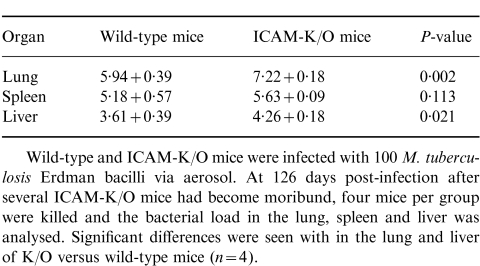

At 126 days post-infection, after three ICAM-K/O mice had died from M. tuberculosis infection, four of the remaining mice from each group were killed and analysed for bacterial load and lung histology. Examination of the lungs of the ICAM-K/O mice revealed extensive macrophage and neutrophil infiltration with no apparent granuloma formation (Fig. 2b,d,e). Widespread tissue necrosis was evident, large numbers of neutrophils were visible, airways were filled with cellular debris, large multinucleated giant cells were present (Fig. 2e), but only small pockets of lymphocytes were seen. Wild-type mice, in contrast, had developed compact discrete granulomas, usually with a central core of lymphocytes surrounded by epithelioid macrophages (Fig. 2a,c). Analysis of visible bacteria within the lungs revealed widely distributed acid-fast bacteria throughout the lungs of ICAM-K/O mice (Fig. 2g), in contrast wild-type mice showed only discrete pockets of bacilli within granuloma formations (Fig. 2f). As well as the significant differences seen in lung histology, analysis of the bacterial load in lung, spleen and liver of these mice revealed that ICAM-K/O mice showed increased bacterial growth in both the lungs and the liver compared to wild-type mice (Table 1).

Figure 2.

Representative photomicrographs from lungs of wild-type and ICAM-K/O mice infected for 126 days with M. tuberculosis Erdman. (a) Wild-type mice: note the multiple organized granulomatous lesions composed of a central core of lymphocytes surrounded by epithelioid macrophages, with few neutrophils present. Large sections of normal lung are still present. (b) ICAM-K/O mice: extensive cellular influx throughout the lung, no organized granulomatous structure is visible and very few areas of normal lung are left. (c) Magnification of a granulomatous lesion from the lungs of a wild-type mouse: note the central lymphocyte core surrounded by large epithelioid macrophages. (d) and (e) Magnification of a section of lung from an ICAM-K/O mouse: tissue shows evidence of extensive necrosis, large numbers of neutrophils and degenerative cells are present. Multinucleated giant cells are visible (arrow) as are several cholesterol clefts (arrowheads), only scattered pockets of lymphocytes are evident. (f) Wild-type mice:note the occasional acid-fast bacilli visible within the macrophages. (g) ICAM-K/O mice: note the multiple acid-fast bacilli visible within most macrophages. (a)–(e) were stained with haematoxylin and eosin staining; (f)and (g) were stained with Kinyoun’s stain. Bar equals 1 mm in (a) and (b) and 100 μm in (c)–(g).

Table 1.

Bacterial load (log10 bacilli/organ) at 126 days post-aerosol infection

|

DISCUSSION

It has been clearly demonstrated that a strong Th1 dominant cell-mediated immune response is essential to the expression of protective immunity against M. tuberculosis. Many studies using gene-disrupted mice have shown that, in the absence of a functional IFN-γ-producing immune response, mice cannot control a normally sublethal M. tuberculosis infection regardless of whether some degree of granuloma formation occurs.1,2,4,14,15 Cell-mediated immunity, even in the absence of granuloma formation, is however, capable of protecting mice in the early stages of M. tuberculosis infection as our previous work has demonstrated.12 Our current experiments expand our understanding of the function of the granulomatous response and demonstrate that an important facet of adequate granuloma formation is to protect M. tuberculosis-infected mice against significant bacillus growth late in the course of the infection.

These data thus support the hypothesis that the influx of macrophages and subsequent granuloma formation is needed for long-term containment of mycobacterial infection and that the absence of this mechanism leads to breakdown of the chronic disease state, increased severity of infection and death of the animal. These data also suggest that in M. tuberculosis infection granulomatous lesions form to surround and envelop infected cells within a wall of epithelioid macrophages to contain and prevent bacterial spread. When infected cells begin to degenerate, the surrounding epithelioid macrophages phagocytose released bacilli, preventing secondary spread of the infection. ICAM-K/O mice have a conformational change in the Mac-1 binding site of the ICAM-1 molecule such that monocytes cannot bind this molecule to cross into infected tissue.11,16,17 Thus in ICAM-K/O mice infected with M. tuberculosis, blood-derived monocytes are unable to enter the infected tissue to surround and wall off infected resident tissue macrophages. Without the surrounding epithelioid macrophages to contain M. tuberculosis bacilli released from dying tissue macrophages, the bacteria rapidly disseminate throughout the lung (as illustrated in Fig. 2g) leading to increased tissue damage. We suspect that a further consequence of these events is that areas of damaged tissue provide an ICAM-1-independent path of entry to the lung for blood-derived monocytes and neutrophils. The increase in bacterial load and damaged tissue presumably stimulates a strong inflammatory cell influx which, at this late stage of infection, would cause further local tissue damage and contribute to host death.

As well as demonstrating a requirement for granuloma formation to maintain a chronic state of infection, these results offer additional evidence that during the chronic stage of disease bacilli are active and not in a latent or dormant state. C57BL/6 mice infected with M. tuberculosis enter a long chronic phase of infection where bacterial numbers remain constant for over 200 days.8 It has been suggested that during this time bacteria are in a latent or dormant phase and hence disease is inactive and bacteria are non-replicating.18–20 Previous studies in this laboratory have questioned this hypothesis as granulomatous lesions continue to develop during the infection, increasing in size and changing in composition and structure throughout the long chronic stage of disease.8 Thus while overall bacterial load may remain apparently unchanged, an active inflammatory cell influx clearly continues. We hypothesize that this occurs because, during the chronic phase of disease, bacterial regrowth occurs occasionally, with any bacteria potentially released from infected macrophages ingested by surrounding epithelioid macrophages thus preventing further bacterial growth and maintaining what appears to be a stable bacterial load. As a result we suspect that this occasional bacterial growth provides a continual stimulus to the immune response generating a sustained inflammatory cell influx that leads to continued granuloma formation and tissue consolidation. In ICAM-K/O mice the lack of epithelioid macrophages surrounding infected tissue macrophages implies that when this occasional bacterial growth does occur, bacilli released from these cells are not contained leading to increased dissemination and heightened bacterial load. One could further argue that, if bacteria in this chronic phase of infection were in a dormant, non-replicating state, this would not be expected to occur in the ICAM-K/O mice.

In conclusion these studies using ICAM-K/O mice show that, while granuloma formation is not required to control or contain the initial stages of M. tuberculosis infection, it is essential during the chronic stage of infection. Our work further strengthens the hypothesis that in the chronic phase of infection, bacteria are not in a dormant state, and rather that occasional bacterial growth occurs, and is contained by the presence of the granulomatous response. In the absence of this control mechanism mice are unable to contain late-term bacterial growth, leading to rapid bacterial dissemination, extensive tissue damage and host death.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by National Institute Health Grants AI-40488 and AI-44072.

References

- 1.Cooper AM, Dalton DK, Stewart TA, Griffin JP, Russell DG, Orme IM. Disseminated tuberculosis in interferon gamma gene-disrupted mice. J Exp Med. 1993;178:2243. doi: 10.1084/jem.178.6.2243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Flynn JL, Chan J, Triebold KJ, Dalton DK, Stewart TA, Bloom BR. An essential role for interferon gamma in resistance to Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection. J Exp Med. 1993;178:2249. doi: 10.1084/jem.178.6.2249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Orme IM, Roberts AD, Griffin JP, Abrams JS. Cytokine secretion by CD4 T lymphocytes acquired in response to Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection. J Immunol. 1993;151:518. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cooper AM, Magram J, Ferrante J, Orme IM. Interleukin 12 (IL-12) is crucial to the development of protective immunity in mice intravenously infected with Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J Exp Med. 1997;186:39. doi: 10.1084/jem.186.1.39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.North RJ. The relative importance of blood monocytes and fixed macrophages to the expression of cell-mediated immunity to infection. J Exp Med. 1970;132:521. doi: 10.1084/jem.132.3.521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Collins FM, Mackaness GB. The relationship of delayed type hypersensitivity to acquired antituberculosis immunity. 1. Tuberculin sensitivity and resistance to reinfection in BCG-vaccinated mice. Cell Immunol. 1970;1:253. doi: 10.1016/0008-8749(70)90047-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Orme IM, Andersen P, Boom WH. T cell response to Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J Infect Dis. 1993;167:1481. doi: 10.1093/infdis/167.6.1481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rhoades ER, Frank AA, Orme IM. Progression of chronic pulmonary tuberculosis in mice aerogenically infected with virulent Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Tuber Lung Dis. 1997;78:57. doi: 10.1016/s0962-8479(97)90016-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Medina E, North RJ. Resistance ranking of some common inbred mouse strains to Mycobacterium tuberculosis and relationship to major histocompatibility complex haplotype and Nramp1 genotype. Immunology. 1998;93:270. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2567.1998.00419.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Orme IM. The kinetics of emergence and loss of mediator T lymphocytes acquired in response to infection with Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J Immunol. 1987;138:293. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sligh J.E. Jr, Ballantyne CM, Rich SS, et al. Inflammatory and immune responses are impaired in mice deficient in intercellular adhesion molecule 1. Proc Nat Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:8529. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.18.8529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Johnson CM, Cooper AM, Frank AA, Orme IM. Adequate expression of protective immunity in the absence of granuloma formation in Mycobacterium tuberculosis-infected mice with a disruption in the intracellular adhesion molecule 1 gene. Infect Immun. 1998;66:1666. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.4.1666-1670.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Orme IM. A mouse model of the recrudescence of latent tuberculosis in the elderly. Am Rev Resp Dis. 1988;137:716. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/137.3.716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Flynn JL, Goldstein MM, Chan J, et al. Tumor necrosis factor-alpha is required in the protective immune response against Mycobacterium tuberculosis in mice. Immunity. 1995;2:561. doi: 10.1016/1074-7613(95)90001-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ladel CH, Blum C, Dreher A, Reifenberg K, Kaufmann SH. Protective role of gamma/delta T cells and alpha/beta T cells in tuberculosis [published erratum appears in Eur J Immunol 1995; 25(12), 3525] Eur J Immunol. 1995;25:2877. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830251025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Springer TA. Traffic signals for lymphocyte recirculation and leukocyte emigration: the multistep paradigm. Cell. 1994;76:301. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90337-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.King PD, Sandberg ET, Selvakumar A, Fang P, Beaudet AL, Dupont B. Novel isoforms of murine intracellular adhesion molecule-1 generated by alternative RNA splicing. J Immunol. 1995;154:6080. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Brown DH, Miles BA, Zwilling BS. Growth of Mycobacterium tuberculosis in BCG-resistant and -susceptible mice: establishment of latency and reactivation. Infect Immun. 1995;63:2243. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.6.2243-2247.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Howard AD, Trask OJ, Weisbrode SE, Zwilling BS. Phenotypic changes in T cell populations during the reactivation of tuberculosis in mice. Clin Exp Immunol. 1998;111:309. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2249.1998.00489.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Phyu S, Mustafa T, Hofstad T, Nilsen R, Fosse R, Bjune G. A mouse model for latent tuberculosis. Scand J Infect Dis. 1998;30:59. doi: 10.1080/003655498750002321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]