Abstract

Occupancy of CTLA‐4 (cytotoxic T‐lymphocyte antigen‐4 or CD152) negatively regulates the activation of mouse T lymphocytes, as indicated by the fate of CTLA‐4‐deficient mice, by the impact of anti‐CTLA‐4 monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) on mouse T‐cell activation in vitro and by the impact of CTLA‐4 blockade on the course of experimental tumoral, autoimmune, alloimmune or infectious disease in this animal. The function of human CTLA‐4, however, remains less clear. The expression and function of human CTLA‐4 were further explored. CTLA‐4 was expressed under mitogenic conditions only, its expression being, at least partially, dependent on the secretion of interleukin‐2. Memory T cells expressed CTLA‐4 with faster kinetics than naive T cells. The functional role of human CTLA‐4 was assessed utilizing a panel of four anti‐CTLA‐4 mAbs that blocked the interaction between CTLA‐4 and its ligands. These mAbs, in immobilized form, profoundly inhibited the activation of T cells by immobilized anti‐CD3 mAb in the absence of anti‐CD28 mAb, but co‐stimulated T‐cell activation in the presence of anti‐CD28 mAb. Finally, and importantly, blockade of the interaction of CTLA‐4 with its ligands using soluble anti‐CTLA‐4 mAbs, in intact form or as Fab fragments, enhanced T‐cell activation in several polyclonal or alloantigen‐specific CD80‐ or CD80/CD86‐dependent assays, as measured by cytokine production, cellular proliferation or cytotoxic responses. It is concluded that interaction of CTLA‐4 with its functional ligands, CD80 or CD86, can down‐regulate human T‐cell responses, probably by intracellular signalling events and independent of CD28 occupancy.

Introduction

CTLA‐4 (cytotoxic T lymphocyte antigen‐4 or CD152), originally discovered in a cDNA library derived from activated T cells, displays important sequence and structure homology with CD28. CD28 and CTLA‐4 also share CD80 and CD86 as their natural ligands. While CD28 is a co‐stimulatory T‐cell receptor of critical importance in the induction of interleukin (IL)‐2 secretion and in the prevention of anergy, the role of CTLA‐4 in the mouse appears to be a negative regulator of T‐cell activation.1,2 Most strikingly, CTLA‐4‐deficient mice develop a massive and rapidly lethal T‐lymphoproliferative disease with splenomegaly, lymphadenopathy and multiorgan T‐lymphocytic infiltration, resulting from excessive proliferation of T cells following recognition of antigen (Ag) and unopposed or uncompeted co‐stimulatory interactions between CD80/CD86 and CD28.3,4 In addition, multivalent ligation of CTLA‐4 on wild‐type mouse T cells strongly inhibits their proliferation, IL‐2 production and cell cycle progression.5–7 Primed T cells, from mice given tolerogenic doses of Ag, show strong proliferative responses in vitro if an anti‐CTLA‐4 monoclonal antibody (mAb) is administered in vivo, which further suggests a role for CTLA‐4 in the induction of T‐cell anergy.8 Finally, selective disruption of interactions of CTLA‐4 with CD80 or CD86 promotes alloantigen‐induced proliferation of mouse T lymphocytes in vitro,9 exacerbates experimental allergic encephalomyelitis in vivo,10,11 promotes antitumour immunity in a colonic tumour model12 and confers protective immunity to nematode infection.13 Yet, a few studies presented conflicting evidence in that, under some conditions, CTLA‐4 can apparently also transmit co‐stimulatory signals in mouse T cells.14

The function of CTLA‐4 in human T‐cell activation remains incompletely resolved. For instance, it was originally reported that immobilized anti‐CTLA‐4 mAb 11D4 and anti‐CD28 mAb 9.3 synergistically co‐stimulate primed CD4+ T lymphocytes.15 However, other mAbs from a panel of four non‐blocking anti‐CTLA‐4 mAbs that were used in soluble form inhibited responses of preactivated T‐cell clones following Ag rechallenge, and of phytohaemagglutinin (PHA) blasts following rechallenge with anti‐CD3 mAbs, an effect that was accompanied by decreased IL‐2 production and increased apoptosis.16 A more detailed analysis of the functional effects of two other non‐blocking anti‐CTLA‐4 mAbs from this same panel was published recently. One of these, in immobilized form, strongly inhibited responses of CD4+ T cells following activation with immobilized anti‐CD3 and anti‐CD28 mAbs, while expression of bcl‐xL was maintained and increased apoptosis could not be demonstrated.17

We have studied the expression of CTLA‐4 following the activation of human T lymphocytes in vitro. Taking advantage of the blocking properties of a recently developed panel of antihuman CTLA‐4 mAbs,18 the functional role of CTLA‐4 in human T‐cell activation was further addressed, using these mAbs in immobilized form to mimic CTLA‐4 occupancy. These mAbs were also used in soluble form in CD80‐ or CD86‐dependent T‐cell activation assays to block interaction of CTLA‐4 with its physiological ligands.

Materials and methods

Cell isolation and culture

Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) and T lymphocytes were isolated as described previously.19 CD4+ and CD8+ or CD45RA+ and CD45RO+ T lymphocytes were fractionated by negative magnetic immunoselection using magnetic cell sorting (MACS) beads (Miltenyi Biotec, Auburn, CA) or Dynalbeads (Dynal, Oslo, Norway).

Dendritic cells were obtained by culturing peripheral blood monocytes for 7 days in complete medium (RPMI‐1640; Gibco Life Sciences, Paisley, Strathclyde, UK) containing 1 mm non‐essential amino acids, 2 mm l‐glutamine, 1 mm sodium pyruvate, 10 mg/l ofloxacin, 10% fetal calf serum (FCS; Gibco) and supplemented with granulocyte–macrophage colony‐stimulating factor (GM‐CSF; 1000 U/ml) (Schering‐Plough, Kenilworth, NJ) and recombinant interleukin‐4 (rIL‐4; 20 ng/ml) (PeproTech Inc., Rocky Hill, NJ).20

mAbs, cell lines and other reagents

The production and characterization of our panel of blocking mAbs against human CTLA‐4 has been described previously.18 The following anti‐CTLA mAbs were used: 1G3 (immunoglobulin [Ig]G2b), 2G12 (IgG2a), 4B10 (IgG2a) and 14D3 (IgG2a). Hybridomas producing UCHT1 (anti‐CD3, IgG1) and isotype‐control Abs S‐S.1 (anti‐sheep red blood cells [RBC], IgG2a) and N‐S.8.1 (anti‐sheep RBC, IgG2b), were from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC; Rockville, MD). mAbs were purified by affinity chromatography and Fab fragments were prepared using commercially available kits (Pierce, Rockford, IL). Purified anti‐CD28 mAb 9.3 (mouse IgG2a) was a gift from Dr C. June (Immune Cell Biology Program, NMRI, Bethesda, MD), and humanized anti‐Tac mAb (anti‐IL2Ra, IgG1) and humanized Mikβ1 (anti‐IL‐2Rb) were gifts from Dr J. Hakimi (Hoffman‐La‐Roche, Nutley, NJ). Biotinylated mouse anti‐TNP mAb (mouse IgG2a) and biotinylated anti‐human CTLA‐4 mAb (mouse IgG2a) were purchased from PharMingen (San Diego, CA). Anti‐CD3 mAb OKT3 (IgG2a) was from Orthobiotech Inc. (Raritan, NJ). Fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)‐conjugated anti‐CD5, phycoerythrin (PE)‐conjugated anti‐CD45RO (Leu‐45RO), FITC‐conjugated anti‐CD45RA (Leu‐18), anti‐CD4 (Leu‐3a) and anti‐CD8 (Leu‐2a) were obtained from Becton‐Dickinson (Erenbodegen, Belgium), rIL‐2 from Boehringer Mannheim (Mannheim, Germany), rIL‐10 from PeproTech Inc. and rIL‐12 from Genetics Institute (Cambridge, MA). A stable CD80 transfectant of the P815 mouse mastocytoma (mouse FcγRII [Fcγ receptor II] and FcγRIII positive) was a gift from Dr L. Lanier (DNAX Research Institute of Molecular and Cellular Biology, Palo Alto, CA) and the KM‐H2 cell line was a gift from Dr S. Fukuhara (Kyoto University, Kyoto, Japan). The Epstein–Barr virus (EBV)‐transformed B‐cell line RPMI 8866 (CD80 and CD86 positive) was obtained from the ATCC.

Polystyrene latex microspheres (4·5 µm in diameter) (Interfacial Dynamics Corporation Portland, OR) or tissue culture plates were coated with mAbs (10 µg/ml), as previously described.19

T‐cell activation assays

T cells (5 × 104 in 200 µl of complete medium with 10% FBS) were cultured in triplicate or quadruplicate in flat‐bottom 96‐well microtitre plates. For polyclonal stimulation, T cells were cultured with PHA (0·5 µg/ml) (Wellcome Diagnostics, Charlotte, NC) or with anti‐CD3 mAb immobilized onto the culture plate, onto microspheres or on irradiated human FcγRII‐ and FcγRIII‐bearing P815 cells, in the presence or absence of soluble anti‐CD28 mAb 9.3, as indicated. For primary mixed lymphocyte reaction (MLR), 50 × 103 T lymphocytes or 100 × 103 peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) (in complete medium, supplemented with 5% autologous serum) were cultured with the irradiated EBV‐transformed cell line RPMI 8866 in varying stimulator–responder ratios, or with irradiated PBMC in a 1 : 1 stimulator–responder ratio. For secondary MLR, T cells or PBMC were stimulated in primary MLR for 5 days, washed, rested for 2 days and rechallenged with fresh irradiated stimulator cells. After the indicated time, cultures were pulsed with 1 µCi of [3H]‐thymidine ([3H]Tdr) for 8 hr.

For cytokine production, 106 T cells were cultured in 1 ml of complete culture medium with 10% FBS in 24‐well microplates for 24–168 hr. Cultures were incubated in the presence of humanized anti‐Tac and humanized Mikβ1, as indicated, or with anti‐IL‐4 receptor (anti‐IL‐4; R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN), in order to minimize consumption of IL‐2 or IL‐4, respectively.21 The cytokine concentration in the culture supernatants was determined by sandwich enzyme‐linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) using pairs of capture and detection mAbs and a calibration curve with the recombinant cytokine. mAbs for the IL‐2 assay were purchased from Genzyme Diagnostics (Cambridge, MA); for the IL‐4 and interferon‐γ (IFN‐γ) assay from Biosource Europe (Fleurus, Belgium); and for the IL‐5 and IL‐10 assay from PharMingen. In this assay, the detection threshold for IL‐4 was 5 pg/ml, and 10 pg/ml for IL‐2, IL‐5, IL‐10 and IFN‐γ.

For flow cytometry, cells were immunostained with primary mAb for 20 min on ice, washed, stained with secondary reagents where required and fixed with 0·4% paraformaldehyde. Events were acquired on a fluorescence‐activated cell sorter (FACScan; Becton‐Dickinson) and analysed with the Cellquest program (Becton‐Dickinson).

Cytotoxicity assay

Cytolytic assays were performed in quadruplicate by incubation of 5 × 103 51Cr‐labelled target cells for 4 hr with different ratios of effector cells. Forty microlitres of the supernatant of each well was transferred to a LumaPlate (Packard BioScience B.V., Groningen, the Netherlands) and counted in a γ‐counter. Results are expressed as specific 51Cr release (SR), using the following formula:

Maximum release was determined by adding Zapoglobin (Coulter Electronics Ltd, Luton, UK) to 5 × 103 51Cr‐labelled target cells in a final volume of 200 µl.22

Results

CTLA‐4 expression occurs transiently after T‐lymphocyte activation and is enhanced by CD28 co‐stimulation

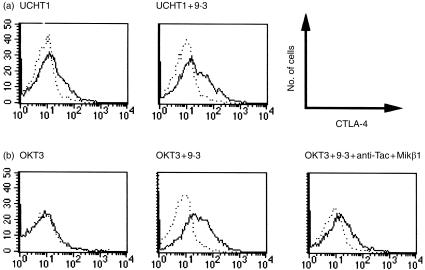

Purified T lymphocytes were stimulated with anti‐CD3 mAbs coated on beads (Fig. 1). While not detectable on resting or unstimulated T cells, membrane expression of CTLA‐4 became apparent after 3 days of stimulation with immobilized UCHT1 (Fig. 1a) and decreased after day 6 (not shown). Maximal induction of CTLA‐4 was reached at a ratio of one to two beads per T cell. Co‐stimulation with anti‐CD28 mAb 9.3, in particular at suboptimal anti‐CD3‐coated bead/T‐cell ratios, enhanced CTLA‐4 expression, with a larger percentage of anti‐CTLA‐4 reactive cells and an increased anti‐CTLA‐4 immunoreactivity on a per‐cell basis. Following stimulation with immobilized OKT3 mAb (a weaker anti‐CD3e mAb of which the T‐cell activating capacity is dependent on co‐stimulation via CD28), CTLA‐4 expression was observed only in the presence of anti‐CD28 mAb 9.3. Immobilized OKT3 also induced expression of CTLA‐4 on purified T cells in the presence of exogenous IL‐2 (10 U/ml, data not shown), while IL‐2 alone did not. Moreover, immobilized OKT3 and soluble anti‐CD28 mAb 9.3 induced much less CTLA‐4 on T cells in the presence of anti‐Tac and Mikβ1, mAbs that block the p55 and p75 subunits of the IL‐2 receptor, respectively (Fig. 1). Exogenous IL‐4, IL‐10 or IL‐12 did not substantially alter the expression of CTLA‐4 (data not shown).

Figure 1.

Cytotoxic T‐lymphocyte antigen‐4 (CTLA‐4) expression on activated human T lymphocytes is enhanced by CD28 co‐stimulation and is interleukin (IL)‐2 dependent. Purified T cells were activated for 4 days with anti‐CD3 monoclonal antibody (mAb) UCHT1 immobilized on latex beads (bead to cell ratio 1 : 2) (a), or by anti‐CD3 mAb OKT3 immobilized on 24‐well plates (b), in the presence or absence of soluble anti‐CD28 mAb 9.3 (500 ng/ml), or anti‐Tac (5 µg/ml) and Mikβ1 (5 µg/ml), as indicated. Cells were stained with fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)‐conjugated anti‐CD5 and with biotinylated anti‐CTLA‐4 mAb BNI3.1 (IgG2a) followed by streptavidin–phycoerythrin (PE) (solid line). Histograms of anti‐CTLA‐4 reactivity of CD5‐positive cells are shown. The results are representative of three experiments. The dotted line represents the biotinylated isotype control stained with streptavidin–PE.

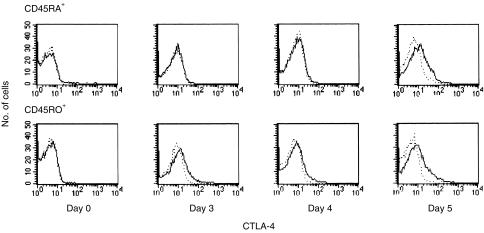

CTLA‐4 expression on activated T cells has a broad distribution (Fig. 1). Part of this has been accounted for by higher expression of CTLA‐4 on the larger blast cells.15 There were no obvious differences in CTLA‐4 expression in CD4+ versus CD8+ human T cells (data not shown). The expression of CTLA‐4 was also investigated in purified naive and memory T‐cell fractions. After stimulation with immobilized UCHT1 and soluble anti‐CD28 mAb, the expression of CTLA‐4 on purified CD45RO+ T cells became detectable more rapidly than on CD45RA+ T cells (Fig. 2). Thus, it can be concluded that naive and memory T cells exhibit differential kinetics of CTLA‐4 expression, which contributes to the broad distribution of CTLA‐4 expression in unfractionated T‐cell populations.

Figure 2.

Human memory T cells express cytotoxic T‐lymphocyte antigen‐4 (CTLA‐4) with more rapid kinetics than naive T cells. CD45RA+ and CD45RO+ T cells, isolated by negative immunomagnetic selection, were activated with anti‐CD3 monoclonal antibody (mAb) UCHT1 immobilized on beads. Anti‐CD28 mAb 9.3 was added to a final concentration of 100 ng/ml. After the indicated intervals, cells were stained with anti‐CD5–fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC) and biotinylated anti‐CTLA‐4 mAb BNI3.1, followed by streptavidin–phycoerythrin (PE) (solid line). Histograms of reactivity with anti‐CTLA‐4 mAb of CD5‐positive cells are shown (solid line), while the dotted line represents the isotype control. The results are representative of four experiments.

Multivalent ligation of CTLA‐4 inhibits polyclonal T‐cell activation in the absence, but not in the presence, of soluble anti‐CD28 mAbs

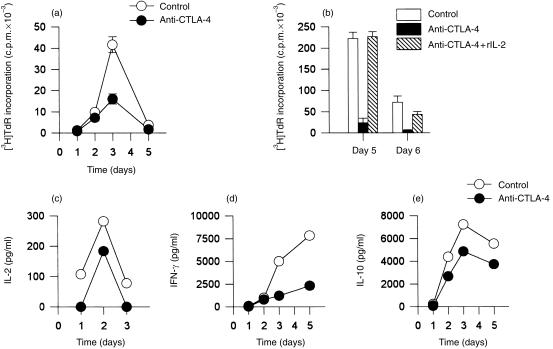

We stimulated highly purified T cells with the immobilized anti‐CD3 mAb UCHT1. This mAb, in immobilized form, can induce T cells to produce IL‐2 and to proliferate in the absence of antigen‐presenting cells (APC) or co‐stimulating mAbs. In these experiments, anti‐CTLA‐4 mAbs were co‐immobilized onto the same beads as UCHT1 in order to provide multivalent binding of CTLA‐4 and thus mimic the physiological effect of CTLA‐4 occupancy. As shown in Fig. 3, co‐immobilized anti‐CTLA‐4 mAbs specifically inhibited UCHT1‐induced T‐cell activation. In the experiment shown, maximal inhibition of cellular proliferation occurred on day 3, although the proliferation and inhibition kinetics varied between the several experiments (Fig. 3a, 3b). The decreased proliferation was not the result of a shift in proliferation kinetics (Fig. 3a). Co‐immobilization of the anti‐CD3 mAb UCHT1 and the anti‐CTLA‐4 mAb onto the same beads was required for this inhibition. In the presence of 10 U/ml of exogenous IL‐2, the inhibition of T‐cell proliferation was almost completely reversed, suggesting that diminished IL‐2 production is pivotal for the decreased T‐cell activation (Fig. 3b). Furthermore, the amounts of IL‐2, IFN‐γ and IL‐10 measured in T‐cell culture supernatants were consistently lower after stimulation with co‐immobilized UCHT1 and anti‐CTLA‐4 mAb compared with the control conditions (Fig. 3c, 3d, 3e). Of note, the production of IL‐2 was strongly inhibited as early as 24 hr following the initiation of cell cultures, i.e. before membrane expression of CTLA‐4 became detectable. Thus, strong multivalent ligation of the CTLA‐4 molecule reduces UCHT1‐induced activation of purified T cells.

Figure 3.

Polyclonal activation of human T cells with immobilized anti‐CD3 monoclonal antibody (mAb) is inhibited by co‐immobilized anticytotoxic T‐lymphocyte antigen‐4 (CTLA‐4) mAb. UCHT1 (anti‐CD3 mAb) and anti‐CTLA‐4 mAbs (a, 14D3; b, 1G3; c, d and e, 2G12) were co‐immobilized onto latex beads and added to cultures of purified T cells at a bead to T‐cell ratio of 2 : 1 (solid circles or bars). Beads with co‐immobilized UCHT1 and isotype‐control mAb were used as controls (open circles or bars). Where indicated, exogenous interleukin (IL)‐2 was added at time 0 to a final concentration of 10 U/ml (b, hatched bars). Cellular proliferation of quadruplicate cultures is shown as [3H]‐thymidine ([3H]TdR) incorporation ± SD (a) (b). The concentration of IL‐2 (c), interferon‐γ (IFN‐γ) (d) and IL‐10 (e) was measured by enzyme‐linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). The data in (a), (b), (c), (d) and (e) were obtained from independent experiments.

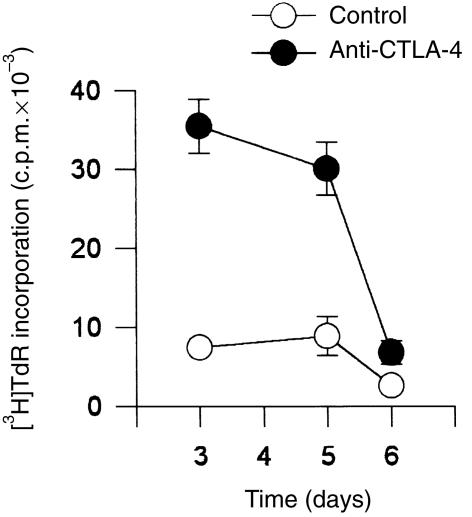

Co‐stimulation with the anti‐CD28 mAb 9.3 strongly induced CTLA‐4 expression on activated T cells (Fig. 1). Therefore, purified T cells or purified CD4+ or CD8+ fractions were stimulated with co‐immobilized OKT3 and anti‐CTLA‐4 mAbs in the presence of CD28 mAb co‐stimulation. In the presence of soluble anti‐CD28 mAb, higher proliferation rates were observed in response to beads coated with OKT3 and anti‐CTLA‐4 mAb than to beads coated with OKT3 and isotype‐control mAbs (Fig. 4). Following stimulation with immobilized UCHT1 at suboptimal levels, a similar positive co‐stimulatory effect of CTLA‐4 ligation was noted in the presence of soluble anti‐CD28 mAb. Similarly, the IL‐2 content in the supernatants of T cells stimulated with co‐immobilized anti‐CD3 and anti‐CTLA‐4 was unchanged or increased in the presence of soluble anti‐CD28 mAbs. This is in contrast to the situation in which T cells were stimulated with immobilized anti‐CD3 mAb and anti‐CTLA‐4 mAb in the absence of anti‐CD28 mAb. Together, these results indicate that multivalent ligation of CTLA‐4 with mAb can both co‐stimulate and inhibit T‐cell activation, depending on whether or not co‐stimulation is provided with the anti‐CD28 mAb 9.3.

Figure 4.

Co‐immobilized anti‐cytotoxic T‐lymphocyte antigen‐4 (CTLA‐4) monoclonal antibody (mAb) enhances polyclonal T‐cell proliferation in the presence of soluble anti‐CD28 mAb. T cells were stimulated with co‐immobilized anti‐CD3 mAb (OKT3) and anti‐CTLA‐4 mAb 14D3 in a bead to T‐cell ratio of 2 : 1 (solid circles) in the presence of soluble anti‐CD28 mAb 9.3 at a final concentration of 100 ng/ml. In control cultures cells were stimulated with beads coated with anti‐CD3 mAb (OKT3) and an isotype control antibody (open circles), in the presence of anti‐CD28 mAb 9.3 (100 ng/ml). [3H]‐Thymidine ([3H]TdR) incorporation is shown as means of quadruplicate cultures ± SD. The results are representative of three experiments.

Anti‐CTLA‐4 mAbs enhance polyclonal CD80‐dependent immune responses of human T cells

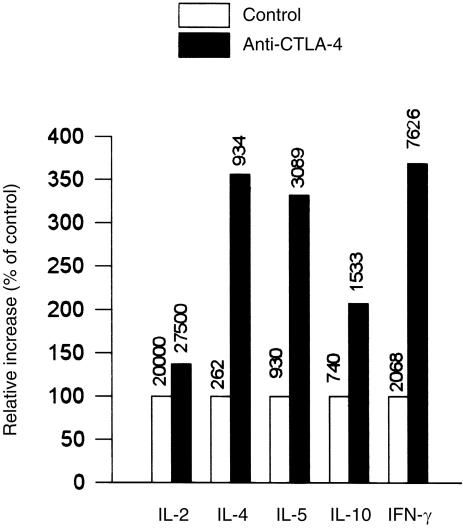

Exploiting the blocking properties of our anti‐CTLA‐4 mAbs, the functional role of CTLA‐4 in human T‐cell responses in vitro was further examined in various CD80/CD86‐dependent T‐cell stimulation assays. P815/CD80, a stable transfectant of the P815 mouse mastocytoma, can present anti‐CD3 mAbs by virtue of its FcγRII and FcγRIII, while fulfilling co‐stimulatory requirements through its expression of CD80. Purified T cells were stimulated with P815/CD80, and anti‐CD3ɛ mAb UCHT1 in the presence or absence of several blocking anti‐CTLA‐4 mAbs in soluble form (Table 1). The presence of soluble anti‐CTLA‐4 mAbs specifically increased T‐cell proliferation compared with isotype‐control mAbs, in particular at days 4–5 of culture. In addition, increased amounts of several cytokines, i.e. IL‐2, IL‐4, IL‐5, IL‐10 and IFN‐γ, were detected in the presence of soluble anti‐CTLA‐4 mAbs, the increase of IFN‐γ production being highest (Fig. 5). Furthermore, enhanced T‐cell proliferation was also noted in the presence of anti‐CTLA‐4 Fab fragments. Thus, in the presence of CD80+ cells, blockade of interactions between CD80 and CTLA‐4 enhances polyclonal T‐cell responses.

Table 1.

Polyclonal CD80‐dependent human T‐cell proliferation is increased in the presence of anti‐cytotoxic T‐lymphocyte antigen‐4 (CTLA‐4) monoclonal antibody (mAb)

| [3H]TdR incorporation (c.p.m. × 10–3 ± SD)* | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Exp. 1: intact mAb | Exp. 2: Fab fragments | |||

| Isotype control | Anti‐CTLA‐4 mAb | Isotype control | Anti‐CTLA‐4 | |

| Day 3 | 75·6 ± 6·0 | 84·7 ± 6·0 | ND | ND |

| Day 4 | 56·7 ± 5·8 | 81·7 ± 4·8 | 11·1 ± 0·8 | 16·8 ± 0·5 |

| Day 5 | 26·6 ± 6·5 | 51·3 ± 3·7 | 3·2 ± 0·1 | 5·8 ± 0·3 |

Human T cells (50 × 10) were cultured in the presence of 5 × 103 (exp. 1) or 10 × 103 (exp. 2) irradiated CD80‐transfected P815 cells. UCHT1 was added to a final concentration of 0·25 µg/ml. Anti‐CTLA‐4 mAb 1G3 or their isotype control (exp. 1) or anti‐CTLA‐4 2G12 Fab fragments or their isotype control (exp. 2) were added to a final concentration of 25 (exp. 1) or 16 (exp. 2) µg/ml. [3H]‐thymidine (TdR) incorporation after 3–5 days of culture is shown the mean± SD of quadruplicate cultures. The results are representative of six (exp. 1) and two (exp. 2) experiments.

c.p.m., counts per minute.

Figure 5.

Blocking anti‐cytotoxic T‐lymphocyte antigen‐4 (CTLA‐4) monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) increase cytokine production in a polyclonal CD80‐dependent T‐cell activation assay. Purified human T cells were stimulated with anti‐CD3 mAb (UCHT1, 1 µg/ml) in the presence of P815/CD80 cells in a stimulator–responder ratio of 2 : 1. Soluble anti‐CTLA‐4 mAb 2G12 was added at 5 µg/ml. Cytokine production was measured after 48 hr of culture (72 hr for interleukin [IL]‐2 production) and is presented as percentage of control. For measurement of IL‐2, humanized anti‐Tac and humanized Mikβ1 were added to block IL‐2 consumption. Anti‐IL‐4 receptor (IL‐4R) was added to block IL‐4 consumption. The absolute cytokine concentration in pg/ml is shown above the bar.

mAbs against human CTLA‐4 augment alloimmune responses and the development of cytotoxic activity in MLR

Next, intact anti‐CTLA‐4 mAbs were added to MLRs of purified T cells against irradiated RPMI 8866 cells, which express CD80 and CD86. While T‐cell proliferation in primary cultures was not consistently altered in the presence of soluble anti‐CTLA‐4 mAb, responses were significantly enhanced in secondary MLR in comparison with isotype‐control mAbs (Table 2). This enhancement was observed on the third and fourth day of culture, with several anti‐CTLA‐4 mAbs, and at several stimulator–responder ratios (1 : 20 and 1 : 50). This effect was specific because T cells, restimulated with KM‐H2, a CD80+ and CD86+ third‐party cell line, did not display an enhanced response. In addition, increased concentrations of IL‐2 and IFN‐γ, but not of IL‐5 or IL‐10, were found after 48–72 hr in the supernatants of secondary MLR against RPMI 8866 in the presence of anti‐CTLA‐4 mAb (data not shown).

Table 2.

Anti‐cytotoxic T‐lymphocyte antigen‐4 (CTLA‐4) monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) augment alloimmune response of human T cells in secondary mixed lymphocyte response (MLR)

| [3H]TdR incorporation (c.p.m. × 10–3 ± SD) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Day 3 | Day 4 | |||||

| Stimulator* | S : R | mAb | Isotype | Anti‐CTLA‐4 | Isotype | Anti‐CTLA‐4 |

| RPMI 8866 | 1 : 20 | IgG2a | 53·9 ± 2·4 | 17·7 ± 2·4 | ||

| 2G12 | 63·0 ± 4·4 | 21·8 ± 2·6 | ||||

| 4B10 | 64·1 ± 5·1 | 22·5 ± 2·6 | ||||

| IgG2b | 56·7 ± 1·6 | 15·9 ± 1·6 | ||||

| 1G3 | 67·3 ± 1·8 | 20·7 ± 3·2 | ||||

| 1 : 50 | IgG2a | 27·7 ± 1·0 | 7·8 ± 0·6 | |||

| 2G12 | 39·0 ± 1·9 | 9·8 ± 1·4 | ||||

| 4B10 | 34·4 ± 2·3 | 9·2 ± 2·0 | ||||

| IgG2b | 29·9 ± 2·6 | 8·7 ± 1·5 | ||||

| 1G3 | 37·1 ± 2·5 | 8·0 ± 2·5 | ||||

| KM‐H2 | 1 : 20 | IgG2a | 30·7 ± 2·4 | 26·7 ± 0·7 | ||

| 2G12 | 27·6 ± 3·7 | 29·0 ± 2·5 | ||||

| 4B10 | 31·5 ± 5·9 | 28·9 ± 4·5 | ||||

| IgG2b | 31·7 ± 2·2 | 25·5 ± 3·5 | ||||

| 1G3 | 34·8 ± 3·6 | 28·9 ± 2·1 | ||||

T cells were cultured for 5 days in primary mixed lymphocyte response (MLR) against irradiated RPMI 8866 cells in a stimulator–responder (S : R) ratio of 1 : 20. Subsequently they were washed and resuspended in complete medium. Forty‐eight hours later, they were restimulated with either RPMI 8866 or with a third‐party stimulator (KM‐H2) in the stimulator–responder ratio indicated, in the presence of either anti‐CTLA‐4 mAb or isotype control. [3H]‐Thymidine (TdR) incorporation on days 3 and 4 is shown as the mean± SD of quadruplicate or triplicate cultures.

Anti‐CTLA‐4 mAbs were also added to primary MLR of peripheral blood T lymphocytes against allogeneic monocyte‐derived dendritic cells, obtained by culture of purified peripheral blood monocytes with GM‐CSF and IL‐4 for 7 days. In these cultures, anti‐CTLA‐4 mAb again increased the T‐cell proliferative response over a range of stimulator–responder ratios from 1 : 4 to 1 : 40 (Fig. 6a).

Figure 6.

Blocking the cytotoxic T‐lymphocyte antigen‐4 (CTLA‐4)–CD80/CD86 interaction enhances T‐cell proliferation and cytotoxic responses in mixed lymphocyte response (MLR) (a) 50 × 103 purified T cells were stimulated with 7·5–10 × 103 allogeneic monocyte‐derived dendritic cells for 6 days. Anti‐CTLA‐4 mAb 2G12 was added to 10 µg/ml. [3H]‐Thymidine ([3H]TdR) incorporation is shown as means of quadruplicate cultures ± SD. The results are representative of three experiments. (b) Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) were stimulated with irradiated allogeneic PBMC in a primary mixed lymphocyte response (MLR) in the presence of Fab fragments of anti‐CTLA‐4 mAb 14D3 or isotype Fab fragments and [3H]TdR incorporation was measured after 6 days. PBMC were also stimulated with allogeneic PBMC and then restimulated in a secondary MLR. After the primary MLR (6 days), the cells were washed and rested in complete medium. After 2 days they were restimulated for 4 days with either freshly isolated PBMC from the same donor or with a third party stimulator, the B‐cell line RPMI 8866, in the presence of Fab fragments of anti‐CTLA‐4 mAb 14D3 or isotype Fab fragments, as indicated. (c) T cells were cultured for 5 days in a primary MLR against irradiated RPMI 8866 at a stimulator–reponder ratio of 1 : 20, and restimulated in a secondary MLR in the presence of either anti‐CTLA‐4 mAb 1G3 or 14D3 or control mouse IgG. After 3 days, specific cytotoxicity was measured. Means of quadruplicate samples are shown ± SD. E : T, ratio of effector cells : target cells.

In MLR of freshly isolated PBMC against irradiated allogeneic PBMC, intact anti‐CTLA‐4 mAb did not consistently enhance primary responses, while in secondary MLR a clear enhancement was found in the presence of intact anti‐CTLA‐4 mAb (data not shown). Anti‐CTLA‐4 Fab fragments enhanced proliferation in both primary and secondary MLR of PBMC against PBMC (Fig. 6b).

Finally, the role of CTLA‐4 was examined in the generation in vitro of alloreactive T‐cellular cytotoxicity. The presence of soluble anti‐CTLA‐4 mAb in secondary MLR of T cells against RPMI 8866 cells (Fig. 6c) or against allogeneic PBMC (data not shown) specifically enhanced the development of cytotoxicity. From these data, it is concluded that blocking anti‐CTLA‐4 mAbs can enhance Ag‐specific alloreactive T‐cell responses.

Discussion

In this study we have further explored the expression and function of human CTLA‐4 in T‐lymphocyte activation. Our studies provide new evidence for a negative regulatory role of CTLA‐4 in human T‐cell activation.

In our experimental system, membrane expression of CTLA‐4 could be found under mitogenic stimulation conditions only, e.g. following stimulation with immobilized UCHT1, with immobilized OKT3 in combination with soluble anti‐CD28 mAb or exogenous IL‐2, but not with immobilized OKT3 or with IL‐2 alone. CTLA‐4 expression is, at least partially, dependent on IL‐2. Consistent with observations by others, we could not demonstrate obvious differences in CTLA‐4 expression between CD4+ and CD8+ human T cells.15 Although considerable heterogeneity in CTLA‐4 expression remains among CD45RO+ versus CD45RA+ T‐cell fractions, CD45RO+ cells express CTLA‐4 with faster kinetics than CD45RA+ T cells.

The effect of interactions between CTLA‐4 and its physiological ligands was examined in several CD80‐ or CD80/CD86‐dependent T‐cell activation assays, taking advantage of the blocking activity of our anti‐CTLA‐4 mAbs. Thus, when T cells were stimulated with P815/CD80 and anti‐CD3 mAb, intact soluble anti‐CTLA‐4 mAb and anti‐CTLA‐4 Fab fragments enhanced the cellular proliferation as well as the production of IFN‐γ, IL‐2, IL‐4, IL‐5 and IL‐10 in comparison with isotype‐control antibodies. T‐cell proliferation, production of IL‐2 and IFN‐γ, and cytotoxicity were specifically enhanced in secondary MLR in the presence of intact soluble anti‐CTLA‐4 mAbs. In primary MLR of PBMC versus PBMC, intact anti‐CTLA‐4 mAb did not consistently affect T‐cell activation but enhanced responses were seen in the presence of Fab. This can be explained by the fact that Fab preparations contain, at most, only traces of intact mAb and behave almost exclusively as CTLA‐4‐blocking agents. Therefore, these blocking experiments provide new evidence that interaction of CTLA‐4 with its ligands negatively regulates T‐cell activation.

In principle, CTLA‐4 blockade can promote T‐cell activity by several mechanisms. First, blockade of their high‐affinity receptor could result directly in an enhanced availability for CD80/CD86 to interact with and provide agonistic co‐stimulatory signals to CD28. Second, blockade of the interactions of CTLA‐4 with CD80/CD86 could result in less negative signalling along a putative signal transduction pathway coupled to the CTLA‐4 receptor. Finally, both possibilities could apply. The marked reduction of cytokine production and of the proliferative response of purified T cells activated with immobilized anti‐CD3 mAb UCHT1 and co‐immobilized anti‐CTLA‐4 mAb, observed in the absence of soluble anti‐CD28 mAb, suggests that CTLA‐4‐coupled signal transduction mechanisms exist, which do not strictly depend on CD28 occupancy. In CD28‐deficient mice, it has indeed been shown that T cells exhibit a diminished proliferative response following engagement of CTLA‐4 by CD80,23 and that blocking anti‐CTLA‐4 mAbs led to accelerated rejection of cardiac allografts.24 This challenges earlier views of Walunas et al. who showed that optimally co‐stimulated mouse T cells are most sensitive to negative control by CTLA‐4, and therefore concluded that CTLA‐4 ligation blocks CD28‐dependent T‐cell activation.7

We failed to find any evidence of inhibition of T‐cell responses by co‐immobilized anti‐CTLA‐4 mAb in the presence of optimal amounts of soluble anti‐CD28 mAb 9.3, but observed co‐stimulatory effects in some experiments, as previously reported.15 This finding contrasts with the inhibition that is observed in the absence of soluble anti‐CD28 mAbs, and with the situation in the mouse, where CTLA‐4 cross‐linking is capable of inhibiting T‐cell activation under optimal conditions with anti‐CD3 and anti‐CD28 mAbs.5–7 However, it has generally been much more difficult in the human to demonstrate a negative regulatory role of CTLA‐4 in the presence of optimal co‐stimulation with anti‐CD28 mAb. Only Blair et al. were able to show such an effect in the presence of titred, suboptimal amounts of anti‐CD28 mAb.17 The enhanced response that we and others have observed in the presence of soluble anti‐CD28 mAb in optimal mitogenic concentrations suggests that the CTLA‐4 receptor may, under certain conditions, positively influence T‐cell activation. However, it can also be considered that the anti‐CD28 mAb constitutes a non‐physiological means of ligation of the co‐stimulatory CD28 receptor that is more difficult to counteract than physiological interactions. In the polyclonal anti‐CD3‐induced T‐cell activation assay with CD80‐transfected P815 cells, the co‐stimulatory CD28 receptor is ligated by one of its physiological ligands. In this co‐stimulatory setting, blocking anti‐CTLA‐4 mAbs were able to enhance T‐cell immune responses, apparently inhibiting an inhibitory signal resulting from interaction of CTLA‐4 with CD80. Therefore, in the presence of physiological co‐stimulatory interactions between CD28 and CD80, T‐cell activation is negatively regulated by the interaction between CTLA‐4 and CD80.

In summary, our blocking studies with anti‐CTLA‐4 mAb provide new evidence that interaction of human CTLA‐4 with its functional ligands, CD80 or CD86, down‐regulates the early stages of human T‐cell activation. In the absence of soluble anti‐CD28 mAb, T‐cell activation was inhibited by immobilized anti‐CTLA‐4 mAb, suggesting that the function of CTLA‐4 as a negative regulator extends beyond its ability to inhibit ligand binding, and that the receptor can function independently of CD28. Blockade of human CTLA‐4 can therefore be envisaged as a potentially new immunotherapeutic strategy in human cancer.

Acknowledgments

P. V. and S. W. V. G. are postdoctoral fellows of the Fonds voor Wetenschappelijk Onderzoek (FWO)‐Vlaanderen. This work was supported, in part, by a ‘Krediet aan navorsers’ and by grant G.0156.96 of FWO‐Vlaanderen to P. V. and grant OT 93/32 from the Research Council of the University of Leuven to J. L. C. The authors thank Dr K. Lorré (Innogenetics, Ghent, Belgium) for assistance with the anti‐CTLA‐4 mAbs, Dr C. H. June (Immune Cell Biology Program, NMRI, Bethesda, MD), Dr L. Lanier (DNAX Research Institute of Molecular and Cellular Biology, Palo Alto, Ca), Dr J. Hakimi (Hoffman‐LaRoche, Nutley, NJ) and Dr S. Fukuhara (Kyoto University, Kyoto, Japan) for generously providing reagents used in this study. The excellent assistance of A. Paesen, L. Coorevits and M. Adé is also acknowledged.

Glossary

Abbreviations

- Tdr

thymidine

- EBV

Epstein–Barr virus

- FcγR

Fcγ receptor

References

- 1.June CH, Bluestone JA, Nadler LM, Thompson CB. The B7 and CD28 receptor families. Immunol Today. 1994;15:321. doi: 10.1016/0167-5699(94)90080-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Linsley PS, Greene JL, Brady W, Bajorath J, Ledbetter JA, Peach R. Human B7 (CD80) and B7 (CD86) bind with similar avidities but distinct kinetics to CD28 and CTLA‐4 receptors. Immunity. 1994;1:793. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(94)80021-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tivol EA, Borriello F, Schweitzer AN, Lynch WP, Bluestone JA, Sharpe AH. Loss of CTLA‐4 leads to massive lymphoproliferation and fatal multiorgan tissue destruction, revealing a critical negative regulatory role of CTLA‐4. Immunity. 1995;3:541. doi: 10.1016/1074-7613(95)90125-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Waterhouse P, Penninger JM, Timms E, et al. Lymphoproliferative disorders with early lethality in mice deficient in Ctla‐4. Science. 1995;270:985. doi: 10.1126/science.270.5238.985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Krummel MF, Allison JP. CD28 and CTLA‐4 have opposing effects on the response of T cells to stimulation. J Exp Med. 1995;182:459. doi: 10.1084/jem.182.2.459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Krummel MF, Allison JP. CTLA‐4 engagement inhibits IL‐2 accumulation and cell cycle progression upon activation of resting T cells. J Exp Med. 1996;183:2533. doi: 10.1084/jem.183.6.2533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Walunas TL, Bakker CY, Bluestone JA. CTLA‐4 ligation blocks CD28‐dependent T cell activation. J Exp Med. 1996;183:2541. doi: 10.1084/jem.183.6.2541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Perez VL, Van Parijs L, Biuckians A, Zheng XX, Strom TB, Abbas AK. Induction of peripheral T cell tolerance in vivo requires CTLA‐4 engagement. Immunity. 1996;6:411. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80284-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Walunas TL, Lenschow DJ, Bakker CY, et al. CTLA‐4 can function as a negative regulator of T cell activation. Immunity. 1994;1:405. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Karandikar NJ, Vanderlugt CL, Walunas TL, Miller SD, Bluestone JA. CTLA‐4: a negative regulator of autoimmune disease. J Exp Med. 1996;184:783. doi: 10.1084/jem.184.2.783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Perrin PJ, Maldonado JH, Davis TA, June CH, Racke MK. CTLA‐4 blockade enhances clinical disease and cytokine production during experimental allergic encephalomyelitis. J Immunol. 1996;157:1333. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Leach DR, Krummel MF, Allison JP. Enhancement of antitumor immunity by CTLA‐4 blockade. Science. 1996;271:1734. doi: 10.1126/science.271.5256.1734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McCoy K, Camberis M, Gros GL. Protective immunity to nematode infection is induced by CTLA‐4 blockade. J Exp Med. 1996;186:183. doi: 10.1084/jem.186.2.183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wu Y, Guo Y, Huang A, Zheng P, Liu Y. CTLA‐4–B7 interaction is sufficient to costimulate T cell clonal expansion. J Exp Med. 1997;185:1327. doi: 10.1084/jem.185.7.1327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Linsley PS, Greene JL, Tan P, et al. Coexpression and functional cooperation of CTLA‐4 and CD28 on activated T lymphocytes. J Exp Med. 1992;176:1595. doi: 10.1084/jem.176.6.1595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gribben JG, Freeman GJ, Boussiotis VA, et al. CTLA4 mediates antigen‐specific apoptosis of human T cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:811. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.3.811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Blair PJ, Riley JL, Levine BL, et al. CTLA‐4 ligation delivers a unique signal to resting human CD4 T cells that inhibits interleukin‐2 secretion but allows Bcl‐X‐L induction. J Immunol. 1998;160:12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vandenborre K, Delabie J, Boogaerts MA, et al. Human CTLA‐4 is expressed in situ on T lymphocytes in germinal centers, in cutaneous graft‐ versus‐host disease and in Hodgkin’s disease. Am J Pathol. 1998;152:963. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vandenberghe P, Ceuppens JL. Immobilized anti‐CD5 together with prolonged activation of protein kinase C induce interleukin 2‐dependent T cell growth: evidence for signal transduction through CD5. Eur J Immunol. 1991;21:251. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830210203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Romani N, Reider D, Heuer M, et al. Generation of mature dendritic cells from human blood. An improved method with special regard to clinical applicability. J Immunol Methods. 1996;196:137. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(96)00078-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bullens DMA, Kasran A, Peng X, Lorre K, Ceuppens JL. Effects of anti‐IL‐4 receptor monoclonal antibody on in vitro T cell cytokine levels: IL‐4 production by T cells from non‐atopic donors. Clin Exp Immunol. 1998;113:320. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2249.1998.00646.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Van Gool SW, Ceuppens JL, Walter H, de Boer M. Synergy between cyclosporin A and a monoclonal antibody to B7 in blocking alloantigen‐induced T‐cell activation. Blood. 1994;83:176. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fallarino F, Fields PE, Gajewski TF. B7 engagement of cytotoxic T lymphocyte antigen 4 inhibits T cell activation in the absence of CD28. J Exp Med. 1998;188:205. doi: 10.1084/jem.188.1.205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lin H, Rathmell JC, Gray GS, Thompson CB, Leiden JM, Alegre ML. Cytotoxic T lymphocyte antigen 4 (CTLA4) blockade accelerates the acute rejection of cardiac allografts in CD28‐deficient mice: CTLA4 can function independently of CD28. J Exp Med. 1998;188:199. doi: 10.1084/jem.188.1.199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]