Abstract

Immune responses to antigens injected into the anterior chamber of the eye are devoid of T helper 1 (Th1)‐type responses of the delayed hypersensitivity type, which has been termed anterior chamber‐associated immune deviation (ACAID). Recently, it has been found that peritoneal exudate cells (PEC) from normal mice can be made to acquire the capacity to induce ACAID in vivo when the cells are pulsed with antigen in vitro in the presence of transforming growth factor‐β2 (TGF‐β2), a major cytokine in the ocular microenvironment. We now report that when ovalbumin (OVA)‐specific T cells from DO11.10 transgenic mice, or from OVA‐primed normal mice, were activated in vitro by normal (untreated) PEC pulsed with OVA, the responding T cells were induced to undergo apoptosis. However, when PEC were first treated with TGF‐β2 and then used to stimulate DO11.10 T cells in the presence of OVA, T‐cell proliferation occurred without evidence of increased apoptosis. The ability of TGF‐β2 to rescue responding T cells from apoptosis rested with the capacity of this cytokine to inhibit interleukin‐12 (IL‐12) production by PEC. Untreated PEC produced large amounts of IL‐12 upon interaction with responding T cells. Under these conditions, tumour necrosis factor‐α (TNF‐α) production was up‐regulated, and this cytokine, in turn, triggered apoptosis among T cells stimulated with OVA‐pulsed PEC. From these results, we conclude that TGF‐β2‐treated APC promote ACAID by rescuing antigen‐activated T cells from apoptosis, and by conferring upon these cells the capacity to down‐regulate delayed hypersensitivity.

Introduction

Immune responses in the normal eye are blunted by several regulatory mechanisms that give rise to the state of immunological privilege.1 When foreign antigens are injected into the anterior chamber of the eye, they elicit a deviant systemic immune response (anterior chamber‐associated immune deviation – ACAID) which is selectively deficient in T cells that mediate delayed hypersensitivity and in B cells that secrete complement‐fixing antibodies.1–4 The ability of the eye to manipulate systemic immune responses in this manner has been traced to a unique local microenvironment that constitutively contains high levels of transforming growth factor‐β2 (TGF‐β2).5,6 In the presence of this cytokine, indigenous antigen‐presenting cells (APC) of the iris and ciliary body acquire novel, functional properties that enable them to capture, process and present antigens to T cells in a manner that creates ACAID.7–9 Wilbanks et al. have reported that APC obtained from conventional body sites, such as the peritoneal cavity, can be made to acquire ACAID‐inducing properties by pulsing the cells in vitro with antigen in the presence of TGF‐β.10,11 Adherent peritoneal exudate cells (PEC) treated in this manner induce antigen‐specific ACAID when injected intravenously into naive, syngeneic recipients.

We have been studying in detail the nature of the changes wrought among PEC by treatment in vitro with TGF‐β2. PEC that have been pulsed with ovalbumin (OVA) in the absence of exogenous TGF‐β readily stimulate DO11.10 T cells. DO11.10 T cells express a transgene that enables their T‐cell receptor (TCR) to recognize peptide 323–339 of OVA in the context of I‐Ad.12,13 DO11.10 T cells stimulated in this manner proliferate and secrete interleukin (IL)‐2 and interferon‐γ (IFN‐γ). Similarly, OVA‐pulsed PEC that have been treated with TGF‐β2 also stimulate DO11.10 T cells. While the responding T cells proliferate readily, they fail to secrete IFN‐γ, but secrete IL‐4 instead.14 We have interpreted these findings to mean that TGF‐β2 treatment of APC changes their functional programme of co‐stimulation such that they promote T helper (Th) cell differentiation toward the Th2, rather than the Th1, pathway. We now report that when T cells activated with antigen‐pulsed PEC were induced to undergo apoptotic cell death, this did not take place if the PEC were pulsed with OVA in the presence of TGF‐β2. Furthermore, antigen‐activated T‐cell death was triggered by tumour necrosis factor‐α (TNF‐α), promoted by PEC‐secreted IL‐12.

Materials and methods

Animals

Normal female BALB/c and C57BL/6 mice were purchased from Taconic Farms (Germantown, NY). Female (B6 × 129) F1 (P55–/–) mice were purchased from Jackson Laboratories (Bar Harbor, ME). DO11.10 TCR transgenic mice, whose TCR is specific for the peptide fragment of OVA, 323–339, in the context of I‐Ad,12,13 were maintained in our colony. All mice were used at 6–8 weeks of age.

Serum‐free medium

Serum‐free medium was used for the cultures. The medium comprised: RPMI‐1640, 10 mm HEPES, 0·1 mm non‐essential amino acids, 1 mm sodium pyruvate, 100 U/ml penicillin, 100 µg/ml streptomycin (all from Biowhitaker, Walksville, MD), 1 × 10–5 m 2‐mercaptoethanol (2‐ME; Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, MO), 0·1% bovine serum albumin (BSA; Sigma Chemical Co.) and ITS + culture supplement (1 µg/ml iron‐free transferrin, 10 ng/ml linoleic acid, 0·3 ng/ml Na2Se and 0·2 µg/ml Fe(NO3)3] (Collaborative Biomedical Products, Bedford, MA).

Purification of T cells

Naive T cells that were specific for OVA peptide sequence 323–339 were obtained from spleens and lymph nodes of naive DO11.10 TCR transgenic mice. To generate OVA‐primed T cells, C57BL/6 mice were immunized with 100 µg/ml of OVA (Sigma Chemical Co.) and complete Freund's adjuvant (CFA) into their foot pads. After 10 days, draining lymph nodes were collected. These cells were pressed through nylon mesh to produce a single cell suspension. Red blood cells were lysed with Tris‐NH4Cl. The cells were washed three times with RPMI‐1640 and purified by passing through a T‐cell enrichment column (R & D Systems, Minneapolis, MN). The recovered cells were found by flow cytometry to be > 95% Thy‐1+ (data not shown).

Preparation of TGF‐β2‐treated PEC

PEC were obtained from normal BALB/c and C57BL/6 mice that had received, intraperitoneally (i.p.), 2 ml of thioglycolate (Sigma Chemical Co.) 3 days earlier. The PEC were washed and resuspended in serum‐free medium. Then, 1 × 106 PEC per well in a 24‐well culture plate were treated overnight with or without 5 ng/ml of porcine TGF‐β2 (R & D Systems) in serum‐free medium at 37° in an atmosphere of 5% CO2. The plates were then washed three times with culture medium to remove TGF‐β2 and non‐adherent cells. For experiments in which these cells were used to stimulate T cells, adherent cells were retained in the wells. More than 90% of these adherent cells were F4/80+ cells (data not shown). For experiments in which TGF‐β‐treated (or untreated) cells were assayed for apoptosis, the following procedure was followed. After overnight incubation at 37°, adherent PEC were cooled to 4° for 30 min, washed twice with ice‐cold medium, then dislodged from the wells with vigorous pipetting. Viability of the recovered cells was routinely > 90%, as judged by Trypan blue exclusion.

IFN‐γ and TNF assays

Purified DO11.10 T cells (2·5 × 104/well) were added to the wells of a 24‐well plate containing TGF‐β2‐treated or‐untreated PEC and various concentrations of OVA. Cells were cultured for 48 hr at 37° in an atmosphere of 5% CO2, then the supernatants were collected and assayed for IFN‐γ and TNF‐α by quantitative capture enzyme‐linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA), according to the manufacturer's instructions. In brief, purified rat monoclonal antibody (mAb) to mouse cytokine IFN‐γ (R4‐6A2) and TNF‐α (G281‐2626) were obtained from PharMingen (San Diego, CA) and used to coat ELISA plates (Falcon, Becton Dickinson & Co, Franklin Lakes, NJ). Recombinant mouse cytokines (IFN‐γ and TNF‐α; PharMingen) were used to construct standard curves, and biotinylated rat mAb to mouse cytokines IFN‐γ (XMG1.2) and TNF‐α (MP6‐XT3) (PharMingen) were used as the second antibody. Plates were read using an ELISA Microplate Reader (Molecular Devices, ThermoMax, Menlo Park, CA) at an absorbance (A) of 405 nm. Each experiment was repeated at least three times with similar results obtained on each occasion.

TUNEL assay

Naive DO11.10 T cells were cultured for 48 hr and primed B6 T cells were cultured for 72 hr with the indicated concentrations of OVA and TGF‐β2‐treated or untreated PEC. In some experiments, IL‐12 (1 ng/ml) and anti‐IL‐12 mAbs (C17.8, 1 µg/ml) were also added to the cultures. T cells were then collected by pipetting. DO11.10 T cells were stained with fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)‐conjugated anti‐DO11.10 TCR mAb (KJ‐126) and C57BL/6 T cells were stained with FITC‐conjugated anti‐CD4 mAb, for 30 min on ice. The cells were then washed twice with phosphate‐buffered saline (PBS) containing 2% fetal calf serum (FCS) and fixed with PBS containing 5% formalin for 30 min at room temperature. The cells were rewashed twice and incubated for 1 hr at 37° in a humidified chamber with 50 µl of a reaction mixture containing: 3 µl of rhodamine‐6‐dUTP 0·1 mm, 3 µl of 1 mm dATP, 2 µl of CoCl2 25 mm, 0·5 µl of 25 U TdT or water and 10 µl of 1 × TdT buffer. At completion of the incubation, the reaction was stopped with 2 µl of 0·5 m EDTA and the cells were washed twice with PBS containing 2% FCS. Stained cells were analysed on an EPICS XL flow cytometer. Each experiment was repeated at least three times with similar results obtained on each occasion.

Assay for FasL expression

Adherent cells (1× 106) collected from PEC treated with or without TGF‐β2 (5 ng/ml) were incubated with 1 µg/ml of rabbit anti‐Fas ligand (FasL) polyclonal antibodies (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA) for 1 hr and washed twice with PBS containing 2% FCS. The cells were then labelled with a secondary FITC‐conjugated goat anti‐rabbit immunoglobulin G (IgG) antibody (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) for 1 hr. As a negative control, cells were incubated with 1 µg/ml ofnon‐specific normal rabbit IgG (R & D Systems) and stained with the secondary antibody. Following incubation with the secondary antibody, the cells were washed twice with PBS containing 2% FCS. Stained cells were analysed on an EPICS XL flow cytometer. The results represent FITC‐positive cells on gated large cells. This experiment was conducted twice with similar results obtained on each occasion.

Results

In the experiments described below, two types of OVA‐reactive T cells were used: naive T cells harvested from DO11.10 mice and lymph node T cells obtained from C57BL/6 mice immunized with OVA in CFA. Responding T cells were stimulated in vitro with adherent macrophages prepared from syngeneic PEC. The PEC were treated (or not) with TGF‐β2 and pulsed with OVA. Previous experiments have shown that DO11.10 T cells proliferate when stimulated with OVA‐pulsed PEC, whether or not the latter cells are pretreated with TGF‐β2.14

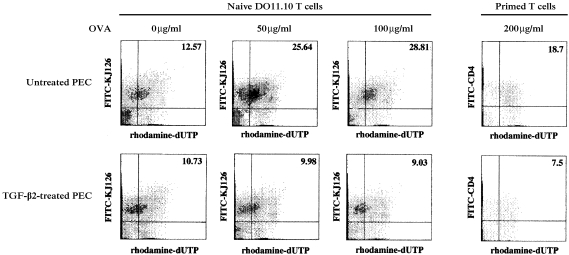

Effect of TGF‐β2 on incidence of apoptosis among T cells stimulated with antigen‐pulsed PEC

Apoptosis can be assessed among single cell suspensions via the TUNEL assay, which identifies cells with DNA breaks characteristic of programmed cell death. This method was used to determine the proportion of responding T cells that underwent apoptosis in cultures. DO11.10 T cells were stimulated in vitro with TGF‐β2‐treated or untreated BALB/c PEC in the presence of OVA at concentrations of 50 or 100 µg/ml. In companion cultures, T cells were harvested from OVA‐sensitized C57BL/6 mice. The cells were then stimulated with untreated, or TGF‐β2‐treated, C57BL/6 PEC in the presence of OVA (200 µg/ml). Control cultures contained responding T cells and PEC, but not OVA. After 48 or 72 hr, the T cells were harvested and the TUNEL assay was performed. The cells were analysed by flow cytometry, and cells undergoing programmed cell death were shown as dUTP‐positive cells. Results of a representative experiment are displayed in Fig. 1. In the absence of OVA (0 µg/ml), the number of apoptotic cells among DO11.10 T cells cultured with either untreated or TGF‐β2‐treated PEC was similar (12·57 and 10·73%, respectively). However, in the presence of OVA (50, 100, or 200 µg/ml), the number of apoptotic DO11.10 T cells (rhodamine‐dUTP positive) cultured with untreated PEC rose ≈ twofold (to 25·64, 28·81 and 18·7%, respectively). No similar increase in the number of apoptotic cells was observed in DO11.10 T‐cell cultures stimulated with TGF‐β2‐treated PEC. A similar pattern of apoptotic cell responses was observed in cultures containing OVA‐primed C57BL/6 T cells (9·98, 9·03 and 7·5%, respectively). Primed T cells stimulated with OVA (200 µg/ml) and untreated PEC displayed 18·7% apoptotic CD4+ T cells, while primed T cells stimulated with TGF‐β2‐treated PEC displayed 7·5%. These results indicate that OVA‐pulsed APC triggered DO11.10 T cells not only to become activated, but to undergo apoptosis. More importantly, these findings reveal that TGF‐β2‐treatment of APC permitted T‐cell activation by antigen, but prevented the cells from being triggered to undergo apoptosis.

Figure 1.

Detection of apoptotic cells among naive or primed T cells stimulated with ovalbumin (OVA)‐pulsed, transforming growth factor‐β2 (TGF‐β2)‐treated, or ‐untreated peritoneal exudate cells (PEC). Naive T cells obtained from DO11.10 T‐cell receptor (TCR) transgenic mice, or primed T cells obtained from C57BL/6 mice immunized with 100 µg/ml of OVA and complete Freund's adjuvant (CFA), were cultured with untreated or TGF‐β2‐treated PEC in the presence of the indicated concentrations of OVA. Cell cultures containing naive T cells were collected after 48 hr and stained with fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)‐conjugated anti DO11.10 TCR mAb (KJ‐126). Cell cultures containing primed T cells were collected after 72 hr, and stained with FITC‐conjugated anti‐CD4 monoclonal antibody (mAb). The cells were then fixed and permeabilized, and the TUNEL assay was performed. Labelled cells were analysed on an EPICS XL flow cytometer. The x‐axis represents rhodamine fluorescence and the y‐axis represents FITC fluorescence on gated small cells. Numbers indicate percentages within quadrants. Similar results were obtained in three additional experiments.

Role of IL‐12 in T‐cell apoptosis stimulated with antigen‐pulsed PEC

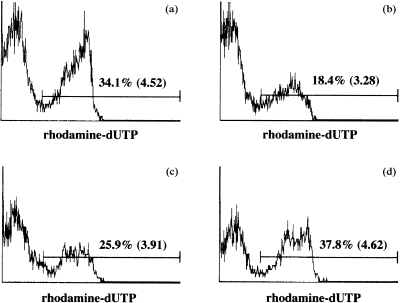

In a previous study, we reported that TGF‐β2‐treatment of PEC impaired the ability of the cells to secrete IL‐12.15 We therefore considered the possibility that IL‐12 is critical to antigen‐activated T‐cell apoptosis by PEC, and that TGF‐β2 prevents apoptosis by inhibiting IL‐12 production by PEC. In the following experiments, DO11.10 T cells were stimulated in vitro with OVA‐pulsed, untreated PEC in cultures to which 1 µg/ml of anti‐IL‐12 antibodies (C17.8) were added, or with OVA‐pulsed, TGF‐β2‐treated PEC in cultures to which 1 ng/ml of exogenous IL‐12 was added. Previous experiments indicated that PEC produce more than 500 pg/ml of IL‐12 in cultures with responding T cells, and that by measuring IFN‐γ production by DO11.10 T cells co‐cultured with OVA‐pulsed PEC, 1 µg/ml of anti‐IL‐12 antibodies (C17.8) was sufficient to neutralize IL‐12 produced by PEC.15 T cells were cultured for 48 hr, then assayed for percentage of apoptotic cells, as described above. The results of a representative experiment are presented in Fig. 2. The percentage of apoptotic DO11.10 T cells from cultures containing OVA‐pulsed, untreated PEC was 34·1% (Fig. 2a). This was reduced to 25·9% in the presence of anti‐IL‐12 antibodies (Fig. 2c). The percentage of DO11.10 T cells displaying apoptosis in cultures stimulated with OVA‐pulsed, TGF‐β2‐treated PEC was 18·4% (Fig. 2b), and this rose to 37·8% when exogenous IL‐12 was added to these cultures (Fig. 2d). In the aggregate, these results strongly indicate that IL‐12 plays a central role in antigen‐activated T‐cell apoptosis. We infer that the ability of TGF‐β2 to suppress PEC production of IL‐12 accounts for the low rate of T‐cell apoptosis observed in cultures containing OVA‐pulsed, TGF‐β2‐treated PEC.

Figure 2.

Effects of interleukin‐12 (IL‐12) on T‐cell apoptosis evoked by ovalbumin (OVA)‐pulsed peritoneal exudate cells (PEC). Naive T cells obtained from DO11.10 mice were cultured for 48 hr with OVA (100 µg/ml) and untreated PEC (a), transforming growth factor‐β2 (TGF‐β2)‐treated PEC (b), untreated PEC and anti‐IL‐12 monoclonal antibody (mAb) (1 µg/ml) (c), or TGF‐β2‐treated PEC + exogenous IL‐12 (1 ng/ml) (d). Thereafter, the cells were collected by pipetting and stained with fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)‐conjugated anti‐DO11.10 TCR mAb (KJ‐126). The cells were then fixed and permeabilized, the TUNEL assay was performed and then the cells were analysed on an EPICS XL flow cytometer. Numbers indicate percentages and mean intensities of dUTP‐positive cells among KJ‐126‐positive cells on gated small cells. Similar results were obtained in three additional experiments.

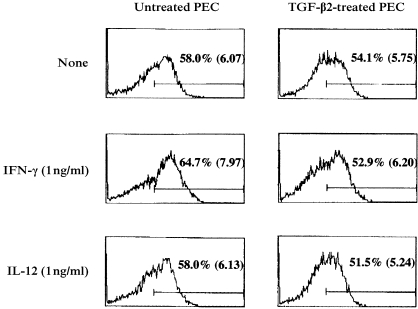

Role of Fas and FasL expression in the IL‐12‐mediated T‐cell apoptosis by antigen‐pulsed PEC

As the IL‐12 receptor does not possess a death domain, IL‐12 is unable to send a death signal directly. Although several different pathways can lead to apoptotic cell death, the interactions of Fas and FasL are often invoked to explain the regulation of T‐cell proliferation in response to antigen.16–19 We first examined the expression of FasL on PEC cultured in the presence or absence of TGF‐β2. In addition, we also evaluated the effects of IL‐12 and IFN‐γ on FasL expression of TGF‐β2‐treated and ‐untreated PEC. FasL expression was evaluated by flow cytometry using FITC‐labelled anti‐FasL antibodies. The results of a representative experiment are displayed in Fig. 3. Cell surface expression of FasL was up‐regulated on PEC cultured overnight under serum‐free conditions (data not shown). Similarly, FasL expression was observed on PEC cultured overnight in the presence of TGF‐β2. Moreover, PEC cultured overnight in the presence of IFN‐γ or IL‐12 expressed FasL to a degree similar to cells cultured in the absence of these cytokines. In fact, although the levels of expression on TGF‐β2‐treated PEC appeared to be slightly lower than those on untreated PEC (see Fig. 3), there was no apparent different between the cells in this series of experiments. Therefore, spontaneous expression of FasL occurred on cultured PEC, and the rate and degree of expression was not influenced by TGF‐β2.

Figure 3.

Fas ligand (FasL) expression on transforming growth factor‐β2 (TGF‐β2)‐treated or untreated peritoneal exudate cells (PEC). PEC collected from BALB/c mice were cultured overnight with or without 5 ng/ml of TGF‐β2 in the presence or absence of interferon‐γ (IFN‐γ; 1 ng/ml) or interleukin‐12 (IL‐12; 1 ng/ml). The cells were then washed, and incubated with rabbit anti‐FasL polyclonal antibodies. Fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)‐conjugated goat anti‐rabbit immunoglobulin G (IgG) antibody was used as a secondary regent. Labelled cells were analysed on an EPICS XL flow cytometer. Numbers indicate percentages and mean intensities of FITC‐positive cells on gated large cells. Similar results were obtained in one additional experiment.

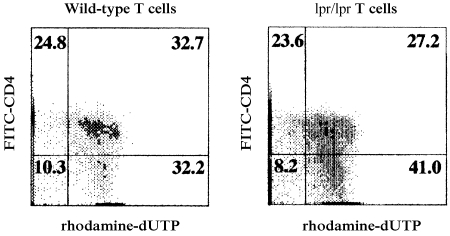

In an effort to gain insight into the functional role of FasL on IL‐12‐mediated T‐cell apoptosis by antigen‐pulsed PEC, we took advantage of Fas‐deficient C57BL/6 mice (lpr/lpr). Wild‐type C57BL/6 PEC can express FasL, but lpr/lpr T cells cannot express Fas. If Fas/FasL interactions are important in IL‐12‐mediated T‐cell apoptosis by antigen‐pulsed PEC, lpr/lpr T cells should be resistant to apoptotic cell death. To test this possibility, primed T cells were harvested from lpr/lpr mice immunized with OVA in CFA, and cultured with OVA‐pulsed PEC obtained from conventional C57BL/6 mice. The cell mixtures were cultured for 72 hr, then assayed for percentage of apoptotic cells, as described above. The results of a representative experiment are presented in Fig. 4. The rate of apoptotic cell death of CD4+ T cells observed in cultures containing OVA‐primed T cells from wild‐type mice (32·7%) was similar to that of CD4+ T cells harvested from cultures containing OVA‐primed lpr/lpr T cells (27·2%). This result indicates that T‐cell apoptosis stimulated with OVA‐pulsed PEC can occur in the absence of a Fas gene product. We conclude that the IL‐12‐mediated T‐cell apoptosis observed in cultures stimulated with antigen‐pulsed PEC is not dependent upon Fas/FasL interactions. If true, this would suggest that TGF‐β2 inhibits antigen‐activated apoptosis by a mechanism that does not involve Fas expression.

Figure 4.

Detection of apoptotic cells among ovalbumin (OVA)‐primed T cells from Fas‐deficient mice. Lymph node cells were obtained from C57BL/6 (+/+) or (lpr/lpr) mice 10 days after immunization with 100 µg/ml of OVA and complete Freund's adjuvant (CFA). Purified, OVA‐primed T cells from wild‐type mice or from lpr/lpr mice were cultured for 72 hr with untreated peritoneal exudate cells (PEC) in the presence of OVA (200 µg/ml). The cells were collected by pipetting, stained with fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)‐conjugated anti‐CD4 monoclonal antibody (mAb), then fixed and permeabilized, and subjected to the TUNEL assay. Labelled cells were analysed on an EPICS XL flow cytometer. The x‐axis represents rhodamine fluorescence and the y‐axis represents FITC fluorescence on gated small cells. Numbers indicate percentages within quadrants.

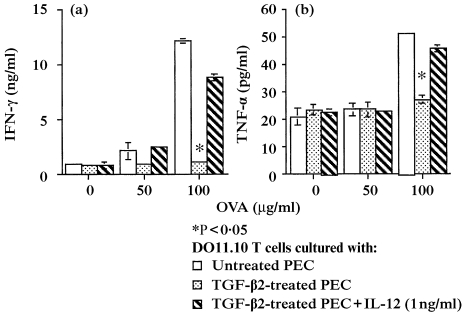

TNF‐α secretion in cultures of T cells stimulated by antigen‐pulsed, TGF‐β2‐treated PEC

TNF‐α‐mediated apoptotic cell death is also known to be induced in activated T cells, as well as the interaction of Fas and FasL.20–22 Therefore, we investigated whether TNF‐α might be acting as a possible mediator of T‐cell apoptosis via IL‐12. First, we examined whether IL‐12 altered TNF‐α production in cultures of DO11.10 T cells stimulated with OVA‐pulsed PEC. In this experiment, DO11.10 T cells were stimulated with different concentrations of OVA and untreated PEC, TGF‐β2‐treated PEC, or TGF‐β2‐treated PEC, in the presence of exogenous IL‐12 (1 ng/ml). The supernatants of these cultures were harvested after 48 hr of incubation and IFN‐γ and TNF‐α concentrations were analysed by ELISA. The results of one of four similar experiments are presented in Fig. 5. Whereas supernatants of cultures containing untreated, OVA‐pulsed PEC plus DO11.10 T cells displayed significant concentrations of TNF‐α and IFN‐γ at 100 µg/ml of OVA, supernatants of similar cultures containing TGF‐β2‐treated PEC, which produce only small amounts of IL‐12, contained little, if any, of these cytokines. However, when the latter cultures were supplemented with exogenous IL‐12, TNF‐α and IFN‐γ secretion was restored.

Figure 5.

(a) Interferon‐γ (IFN‐γ) and (b) tumour necrosis factor‐α (TNF‐α) production induced by stimulation with interleukin‐12 (IL‐12). DO11.10 T cells were cultured with the indicated concentrations of ovalbumin (OVA) and untreated peritoneal exudate cells (PEC) (open squares), transforming growth factor‐β2 (TGF‐β2)‐treated PEC (open circles), or TGF‐β2‐treated PEC + exogenous IL‐12 (1 µg/ml) (open triangles). After 48 hr, supernatants were collected and measured for IFN‐γ and TNF‐α concentrations using enzyme‐linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). Each data point represents the mean of duplicate cultures. *Indicates mean values significantly lower than untreated PEC controls (P < 0·05).

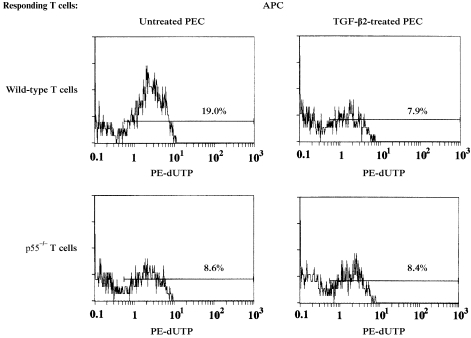

Role of TNF‐α in the IL‐12‐mediated T‐cell apoptosis by antigen‐pulsed PEC

TNF receptor 1 (TNF‐R1; p55) is expressed on lymphohaematopoietic cells, and possesses an intracytoplasmic death domain similar to Fas.23,24 When engaged with TNF‐α, TNF‐R1‐bearing cells undergo programmed cell death. We used T cells from TNF‐R1‐deficient mice to confirm whether TNF‐α was critical for IL‐12‐mediated T‐cell apoptosis by antigen‐pulsed PEC. TNF‐R1‐deficient C57BL/6 mice (p55–/–) as well as wild‐type C57BL/6 mice were immunized with OVA in CFA. Thereafter, primed T cells were harvested from these mice and placed in cultures containing OVA‐pulsed, untreated or TGF‐β2‐treated PEC. After 48 hr of culture, the T cells were harvested and assayed for percentage of apoptotic cells. The results of one such experiment are displayed in Fig. 6. Among OVA‐primed T cells from wild‐type C57BL/6 mice, the percentage of apoptotic CD4+ T cells in cultures stimulated with TGF‐β2‐treated PEC was only 7·9%, whereas the percentage of apoptotic cells from cultures containing untreated PEC was 19%. However, among primed T cells from TNF‐R1‐deficient mice, the percentage of apoptotic CD4+ T cells stimulated with OVA‐pulsed, untreated PEC was less than 10%, which was similar to that of CD4+ T cells stimulated with OVA‐pulsed, TGF‐β2‐treated PEC. Thus, IL‐12‐mediated T‐cell apoptosis, triggered by stimulation with antigen‐pulsed PEC, was strongly suppressed in primed T cells from TNF‐R1‐deficient mice. As TNF‐α production by T cells from TNF‐R1‐deficient mice stimulated with OVA‐pulsed PEC was not altered (data not shown), the suppression of the activated T cells can be ascribed to the inability of TNF‐α to trigger cell death via TNF‐R1.

Figure 6.

Detection of apoptotic cells among ovalbumin (OVA)‐primed T cells obtained from tumour necrosis factor receptor 1 (TNF‐R1)‐deficient mice. Lymph node cells were obtained from C57BL/6 (wild type) or (p55–/–) mice 10 days after immunization with 100 µg/ml of OVA and complete Freund's adjuvant (CFA). Purified, OVA‐primed T cells from wild‐type mice or p55–/– mice were cultured with TGF‐β2‐treated peritoneal exudate cells (PEC) or untreated PEC in the presence of 200 µg/ml of OVA for 72 hr, then collected by pipetting, and stained with FITC‐conjugated anti‐CD4 monoclonal antibody (mAb). The cells were then fixed and permeabilized for the TUNEL assay, and analysed on an EPICS XL flow cytometer. Numbers indicate dUTP‐positive cells among CD4‐positive cells on gated small cells. APC, antigen‐presenting cells; PE, phycoerythrin.

These findings support the conclusion that OVA‐pulsed PEC triggered T‐cell apoptosis via TNF‐α and that TGF‐β2 pretreatment of the PEC robbed them of this capacity, perhaps by reducing their production of IL‐12.

Discussion

Antigens injected into the anterior chamber of the eye elicit a systemic immune response in which precursors of primed CD8+ cytotoxic T cells and B cells that secrete non‐complement fixing (IgG1) antibodies are generated.11,25–27 At the same time, CD4+ T cells that mediate delayed hypersensitivity cannot be identified, and the ability of mice with ACAID to express delayed hypersensitivity is actively down‐regulated. When ACAID is induced in immunologically naive mice, an antigen‐specific signal is prepared within the eye itself and takes the form of bone marrow‐derived dendritic cells/macrophages that bear the marker molecule, F4/80.7,8 Cells of this type normally reside in the stroma of intraocular tissues (iris, ciliary body, trabecular meshwork), and upon introduction of antigen into the eye, these cells capture antigen and migrate across the trabecular meshwork into the blood.7–9,11 Eventually, they reach the spleen where the unique spectrum of antigen‐specific T and B cells of ACAID are first identified. The fact that F4/80+ cells harvested from extraocular body sites (peritoneal cavity, blood, spleen) can be endowed with ACAID‐inducing properties by exposing the cells to antigen plus TGF‐β2 in vitro has enabled us to study, in a rather direct manner, certain cellular and molecular aspects of ACAID induction.28 The results that form the basis of this work help to reveal important aspects of T‐cell activation in ACAID.

We have previously reported that OVA‐pulsed APC induce antigen‐specific T‐cell proliferation in vitro, whether the stimulating cells are untreated, or are first exposed to TGF‐β2.14 Our present findings indicate the following. First, unprimed OVA‐specific DO11.10 T cells and in vivo‐primed OVA‐specific T cells undergo apoptosis when stimulated in vitro with adherent syngeneic APC pulsed with OVA in the absence of TGF‐β; and second, OVA‐specific T cells are rescued from antigen‐activated apoptosis if the APC are first exposed to TGF‐β2. Thus, TGF‐β2 alters the properties of APC in a manner that protects T cells from antigen‐activated programmed cell death.

Our previous studies of this in vitro model system have shown that PEC treated with TGF‐β2 acquire novel properties. First, the cells produce increased amounts of their own TGF‐β, and much of the protein is secreted in its mature form.14 Second, TGF‐β2‐treated APC secrete significantly less IL‐12 than their untreated counterparts, and as a consequence the APC express only low levels of CD40.15 Nonetheless, these altered properties still enable the APC to process and present OVA to DO11.10 T cells, but the responding cells produce IL‐4 rather than IFN‐γ. That is, TGF‐β2‐treated APC cause naive transgenic T cells to differentiate down the Th2 pathway, rather than the Th1 pathway.14 The results reported here indicate an additional antigen‐presenting function of TGF‐β2‐treated APC with ACAID‐inducing properties. The inability of TGF‐β2‐treated PEC to produce IL‐12 permits efficient activation of responding T cells by preventing the T cells from undergoing activation‐induced apoptotic cell death. In the absence of exogenous TGF‐β, PEC interacting with responding T cells secrete large amounts of IL‐12, and this cytokine induces responding T cells and/or PEC to produce TNF‐α. We provide circumstantial evidence that TNF‐α, acting through TNF‐R1 on responding T cells, triggers programmed cell death. By virtue of its ability to reduce IL‐12 production, and perhaps to enhance endogenous TGF‐β production, exogenous TGF‐β2 prevents responding T cells from undergoing apoptotic cell death.

These results indicate that TGF‐β2 rescued responding T cells from apoptosis by a TNF‐α‐dependent, rather than a Fas‐dependent, pathway. First, whether treated with TGF‐β2 or not, PEC up‐regulated FasL comparably when cultured overnight in vitro. Second, T cells from C57BL/6 lpr/lpr mice that had been primed by OVA in vivo underwent apoptotic cell death when cultured with OVA‐pulsed PEC. Abbas et al. have reported that activation‐induced cell death is associated with Fas–FasL interactions.29,30 However, it is probable that Fas–FasL interactions play only a minor role in the IL‐12‐mediated apoptosis among T cells activated by antigen‐pulsed PEC. This discrepancy may relate to experimental systems, antigens, and the types of APC and responding T cells.

In this series of experiments, PEC pulsed with 50 µg/ml of OVA induced activation‐induced T‐cell apoptosis, but there was little difference in the amounts of TNF‐α produced by untreated PEC and TGF‐β2‐treated PEC at that concentration of OVA (Fig. 1 and Fig. 5). It is known that proteolysis of cell surface membrane‐bound TNF‐α (which is mediated by a membrane metalloproteinase) is required to produce soluble TNF‐α.31,32. Moreover, membrane‐bound TNF‐α is more active than soluble TNF‐α.32 Therefore, it is possible that the amounts of soluble TNF‐α in supernatants may not correlate with the magnitude of apoptotic cell death mediated by TNF‐α, especially if the production of soluble TNF‐α is low.

We were not able to identify precisely the cellular source of TNF‐α found in the culture system studied. As the levels of TNF‐α found in cultures of DO11.10 T cells stimulated with OVA‐pulsed PEC increased in an antigen dose‐dependent fashion, we suspect that antigen‐activated T cells contributed to the increased levels of TNF‐α found in cultures. Moreover, we found that enhanced TNF‐α production (as well as enhanced T‐cell apoptosis) correlated with the presence of IL‐12 in the cultures. As T cells are known to respond to IL‐12 signals, these findings support the view that T‐cell‐derived TNF‐α is responsible for the increased apoptosis observed in our cultures. However, macrophages harvested from the peritoneal cavity of thioglycollate‐treated mice constitutively produce low levels of TNF‐α, and this level was reduced in the presence of TGF‐β2 (data not shown). In addition, it is conceivable that IL‐12 enhances the ability of PEC to produce TNF‐α indirectly, via IFN‐γ production by responding T cells.

This apoptotic process may reflect a physiological mechanism for regulation of T cells, especially Th1 cells. If so, then intraocular TGF‐β2 has the interesting effect of equipping eye‐derived APC with a co‐stimulatory repertoire that sustains, rather than curtails, T‐cell proliferation. As these TGF‐β2‐treated APC also promote regulatory T cells, including cells of the Th2‐type, the eye, and the phenomenon of immune privilege, may benefit from sustained T‐cell responses that generate T cells which suppress immunogenic inflammation in an antigen‐specific manner.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr Jacqueline Doherty and Ms Marie Ortega for outstanding managerial and technical support. This work was supported by USPHS grant EY 05678.

Glossary

Abbreviations

- ACAID

anterior chamber‐associated immune deviation

- APC

antigen‐presenting cells

- CFA

complete Freunds' adjuvant

- OVA

ovalbumin

- PEC

peritoneal exudate cells

References

- 1.Streilein JW. Immune privilege as the result of local tissue barriers and immunosuppressive microenvironments [Review] Curr Opin Immunol. 1993;5:428. doi: 10.1016/0952-7915(93)90064-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Streilein JW. Immune regulation and the eye: a dangerous compromise [Review] FASEB J. 1987;1:199. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Niederkorn JY. Immune privilege and immune regulation in the eye [Review] Adv Immunol. 1990;48:191. doi: 10.1016/s0065-2776(08)60755-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Streilein JW, Niederkorn JY, Shadduck JA. Systemic immune unresponsiveness induced in adult mice by anterior chamber presentation of minor histocompatibility antigens. J Exp Med. 1980;152:1121. doi: 10.1084/jem.152.4.1121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cousins SW, McCabe MM, Danielpour D, Streilein JW. Identification of transforming growth factor‐beta as an immunosuppressive factor in aqueous humor. Invest Ophthal Vis Sci. 1991;32:2201. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Granstein RD, Staszewski R, Knisely TL, et al. Aqueous humor contains transforming growth factor‐beta and a small (less than 3500 daltons) inhibitor of thymocyte proliferation [published erratum appears in J Immunol 1991 May 15; 146 (10): 3687] J Immunol. 1990;144:3021. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wilbanks GA, Streilein JW. Studies on the induction of anterior chamber‐associated immune deviation (ACAID). 1. Evidence that an antigen‐specific, ACAID‐inducing, cell‐associated signal exists in the peripheral blood. J Immunol. 1991;146:2610. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wilbanks GA, Mammolenti M, Streilein JW. Studies on the induction of anterior chamber‐associated immune deviation (ACAID). II. Eye‐derived cells participate in generating blood‐borne signals that induce ACAID. J Immunol. 1991;146:3018. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Williamson JS, Bradley D, Streilein JW. Immunoregulatory properties of bone marrow‐derived cells in the iris and ciliary body. Immunology. 1989;67:96. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wilbanks GA, Mammolenti M, Streilein JW. Studies on the induction of anterior chamber‐associated immune deviation (ACAID). III. Induction of ACAID depends upon intraocular transforming growth factor‐beta. Eur J Immunol. 1992;22:165. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830220125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wilbanks GA, Streilein JW. Macrophages capable of inducing anterior chamber associated immune deviation demonstrate spleen‐seeking migratory properties. Reg Immunol. 1992;4:130. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hsieh C‐S, Heimberger AB, Gold JS, O'garra A, Murphy KM. Differential regulation of T helper phenotype development by IL‐4 and IL‐10 in an αβ‐TCR transgenic system. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:6065. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.13.6065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wang R, Murphy KM, Loh DY, Weaver C, Russell JH. Differential activation of antigen‐stimulated suicide and cytokine production pathways in CD4+ T cells is regulated by the antigen‐presenting cell. J Immunol. 1993;150:3832. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Takeuchi M, Kosiewicz MM, Alard P, Streilein JW. On the mechanisms by which TGFβ‐2 alters antigen presenting abilities of macrophages on T cell activation. Eur J Immunol. 1997;27:1648. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830270709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Takeuchi M, Alard P, Streilein JW. TGFβ promotes immune deviation by altering accessory signals of antigen presenting cells. J Immunol. 1998;160:1589. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dhein J, Walczak H, Baumler C, Debatin K, Krammer PH. Autocrine T‐cell suicide mediated by APO‐1/ (Fas/CD95) Nature. 1995;373:438. doi: 10.1038/373438a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Brunner T, Mogil RJ, Laface D, et al. Cell‐autonomous Fas (CD95)/Fas‐ligand interaction mediates activation‐induced apoptosis in T‐cell hybridomas. Nature. 1995;373:441. doi: 10.1038/373441a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ju S, Panka DJ, Cui H, et al. Fas (CD95)/FasL interactions required for programmed cell death after T‐cell activation. Nature. 1995;373:444. doi: 10.1038/373444a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Crispe IN. Fatal interactions: Fas‐induced apoptosis of mature T cells. Immunity. 1994;1:347. doi: 10.1016/1074-7613(94)90064-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sytwu HK, Liblau RS, McDevitt HO. The roles of Fas/APO‐1 (CD95) and TNF in antigen‐induced programmed cell death in T cell receptor transgenic mice. Immunity. 1996;5:17. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80306-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zheng L, Fisher G, Miller RE, Peschon J, Lynch DH, Lenardo MJ. Induction of apoptosis in mature T cells by tumor necrosis factor. Nature. 1995;377:348. doi: 10.1038/377348a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sarin A, Conari‐cibotti M, Henkart PA. Cytotoxic effect of TNF and lymphotoxin on T lymphoblasts. J Immunol. 1995;155:3716. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kitson J, Raven T, Jiang YP, et al. A death‐domain‐containing receptor that mediates apoptosis. Nature. 1996;384:372. doi: 10.1038/384372a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Weiss T, Grell M, Hessabi B, et al. Enhancement of TNF receptor p60‐mediated cytotoxicity by TNF receptor p80: requirement of the TNF receptor‐associated factor‐2 binding site. J Immunol. 1997;158:2398. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wilbanks GA, Streilein JW. Characterization of suppressor cells in anterior chamber‐associated immune deviation (ACAID) induced by soluble antigen. Evidence of two functionally and phenotypically distinct T‐suppressor cell populations. Immunology. 1990;71:383. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wilbanks GA, Streilein JW. Distinctive humoral immune responses following anterior chamber and intravenous administration of soluble antigen. Evidence for active suppression of IgG2‐secreting B lymphocytes. Immunology. 1990;71:566. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Streilein JW, Niederkorn JY. Characterization of the suppressor cell(s) responsible for anterior chamber‐associated immune deviation (ACAID) induced in BALB/c mice by P815 cells. J Immunol. 1985;134:1381. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wilbanks GA, Streilein JW. Fluids from immune privileged sites endow macrophages with the capacity to induce antigen‐specific immune deviation via a mechanism involving transforming growth factor‐beta. Eur J Immunol. 1992;22:1031. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830220423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Van Parijs L, Biuckians A, Ibragimov A, Xxxxxx AFW, Willerford DM, Abbas AK. Functional responses and apoptosis of CD25 (IL‐2R alpha)‐deficient T cells expressing a transgenic antigen receptor. J Immunol. 1997;158:3738. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Singer GG, Abbas AK. The Fas antigen is involved in peripheral but not thymic deletion of T lymphocytes in T cell receptor transgenic mice. Immunity. 1994;1:365. doi: 10.1016/1074-7613(94)90067-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gearing AJH, Beckett P, Christodoulou M, et al. Processing of tumor necrosis factor‐a precursor by metalloproteinases. Nature. 1994;370:555. doi: 10.1038/370555a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Grell M, Douni E, Wajant H, et al. The transmembrane form of the tumor necrosis factor is the prime activating ligand of the 80 kDa tumor necrosis factor receptor. Cell. 1995;83:793. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90192-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]