Abstract

Prolactin (PRL) shares structural and functional features with haemopoietic factors and cytokine peptides. Dendritic cells (DC) are involved in both initiating the primary and boosting the secondary host immune response and can be differentiated in vitro from precursors under the effect of granulocyte–macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF) plus other factors. Because PRL has been shown to functionally interact with GM-CSF, we have addressed its role on GM-CSF-driven differentiation of DC. Monocytic DC precursors from peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) were enriched either by adhesion to a plastic surface or CD14-positive selection and cultured for 7 days in serum-free medium containing GM-CSF, interleukin (IL)-4 and PRL, alone or in combination. Cells with large, veiled cytoplasm, expressing major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class II and the costimulatory molecules CD80, CD86 and CD40 and lacking the monocyte marker CD14, were considered as having the phenotype of cytokine-generated DC. Functional maturation was assessed by proliferation and interferon-γ (IFN-γ) release of allogeneic T lymphocytes. Physiological (10–20 ng/ml) concentrations of PRL interacted synergistically with GM-CSF and the effect was similar to that induced by IL-4 on GM-CSF-driven DC maturation. When used alone, the physiological concentrations of PRL were inhibitory, whereas higher concentrations (80 ng/ml) were stimulatory. The synergistic effect of PRL may in part be caused by its ability to counteract the down-modulation of the GM-CSF receptor observed in serum-free conditions. These data provide further evidence of the significance of PRL in the process of T lymphocyte activation.

Introduction

Prolactin (PRL) is a member of the cytokine family.1 PRL receptor (R), a type I haematopoietin receptor,1,2 is widely distributed within the lymphohaemopoietic system3,4 and its triggering on T lymphocytes is coupled with early and late T-cell activatory events.2,4 PRL has been demonstrated to modulate the T-cell antigen receptor expression and phosphorylate the kinases activated by T-cell receptor (TCR) ligation.5,6 Activation of genes involved in T-cell clonal amplification (i.e. interleukin-2 (IL-2) and interferon-γ (IFN-γ)) has also been demonstrated.7–9 T-cell activation requires antigen presentation by professional antigen-presenting cells (APC). Dendritic cells (DC) are present in blood or can be readily differentiated by non-proliferating adherent monocytes.10–14 This in vitro generation is an important step towards understanding their physiology and potential use in immunotherapy. Granulocyte–macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF) appears to be a central factor for DC development.12–15 Following 7-day activation with GM-CSF and IL-4, in fact, monocytes lose the specific CD14 antigen and progressively increase the expression of molecules involved in antigen presentation (major histocompatibility complex (MHC) II) and the costimulatory molecules CD80 and CD86. They thus become active T-cell stimulators. Because PRL has been shown by our group to interact with GM-CSF,16,17 we have here addressed its possible involvement, alone or in combination with GM-CSF, in the process of DC maturation and antigen presentation.

Materials and methods

Cytokine factors and antibodies

Recombinant (r) GM-CSF and IL-4 were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich s.r.l (Gallarate, Milan, Italy). Human pituitary (h)PRL and rhPRL were generously donated by the NIDDK (Baltimore, MD) and Genzyme Corporation (Cambridge, MA), respectively. The IC-5 anti-hPRL blocking antiserum16 is a gift of Dr Parlow, Torrance, CA. The monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) to CD14, CD80, CD86, CD83, CD1a and CD40 were from Becton Dickinson (Mountain View, CA). Anti-Cdw116PE (clone SCO6) directed against the GM-CSF-R (Immunotech Marseille, France) was generously donated by Instrumentation Laboratory (Milan, Italy).

Preparation of DC

PBMC were isolated from heparinized blood of normal healthy donors by standard Ficoll–Paque (Pharmacia, Uppsaala, Sweden) density gradient centrifugation. They were collected from the interface, washed three times in RPMI-1640 (Gibco BRL, Gaithersburg, MD) supplemented with 5 mm ethylenediamine tetra-acetic acid (EDTA) and 2% fetal calf serum (FCS) and then suspended at 5 × 106/ml in RPMI−10% FCS. Next, 3 ml were added to 25 cm2 flasks. After a 2-hr incubation at 37° in a humidified, 5% CO2 incubator, non-adherent cells were removed by two washings with prewarmed (37°) 10% FCS RPMI medium. Adherent cells were then resuspended in 2 ml serum-free RPMI medium added with bovine insulin (Na, Zn free, 5 µg/ml), human (holo) transferrin (5 µg/ml) and sodium selenite (5 ng/ml) (Redu-Ser™ UBI, Lake Placid, NY). GM-CSF (10 ng/ml), IL-4 (10 ng/ml), PRL (10–80 ng/ml, as indicated), alone or in combination, were added at the start and after 72 hr. In some experiments cultures were started with a purified (> 90%) population of CD14+ cells positively selected with magnetic microbeads on a magnetic antibody cell sorting (MACS) separation column (Miltenyl Biotec, Germany). Parallel cultures were set up in the presence of anti-hPRL antiserum IC-5 at the dilution of 1 : 250, previously reported to produce optimal and specific PRL neutralization in a GM-CSF colony-forming assay.16

Determination of cell morphology

On day 7, cells were harvested and centrifuged onto microscope slides with a Cytospin-2 centrifuge (Haereus, Milan, Italy), stained with May–Grunwald–Giemsa solution and analysed under a Leitz Wetzlar (Germany) microscope.

Immunofluorescence staining procedures

Cells (1 × 107/ml) were incubated for 20 min at 4° with fluoroscein isothiocyanate (FITC)- or phycoerythrin (PE)-conjugated mAbs and isotype controls. Fluorescence-activated cell sorting was performed using a FACScan flow cytometer (Becton Dickinson).

Proliferation assay (mixed lymphocyte reaction; MLR)

A constant number (5 × 105) of allogeneic highly purified T lymphocytes, obtained through gradient centrifugation of E-rosetted peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC), were incubated with fixed (5 × 104) or graded numbers of irradiated (3000 rad 137Cs source) cytokine-generated DC. Experiments were performed in 96-well cell culture plates in RPMI-1640 medium supplemented with 10% FCS. To test the extent of DNA synthesis, day 4 cultures were admixed 2 µCi/ml of [methyl-3H]-TdR (5 Ci/mm specific activity) (NEN-Dupont, Milan, Italy) 16 hr before harvesting onto glass fibre filters. 3H-TdR uptake was evaluated by β-scintillation counting and expressed as c.p.m./106 cells. Net c.p.m. was calculated as:

c.p.m. of cultures with factors -

c.p.m. of cultures without factors

GM-CSF-R quantification

Adherent PBMC were detached from the plastic flasks with a rubber scraper immediately after adherence (‘uncultured monocytes’) or after a 72-hr culture with or without PRL (10, 20, 40 and 80 ng/ml). A flow cytometry quantification analysis of GM-CSF-R was performed, as previously described,18 in the cells gated in the monocyte region (more than 90% of CD14+ cells). The average number of GM-CSF-R per cell was quantified with the Quantum TM 27 PE conjugated Kit (Flow Cytometry Standard Corporation, San Juan, Puerto Rico) (generously donated by Walter Occhiena, Turin, Italy). This contains a set of calibrated standards with four populations of microbeads displaying increasing and predetermined fluorescence intensity (expressed in terms of number of molecules of equivalent soluble fluorochrome, MESF) and one blank reference population. The relative channel number obtained by flow cytometry analysis of a cell population was directly transformed into the number of MESF and the linear the channel number with the specific MESF value was calculated using a specific software (Quickcal Flow Cytometry Corporation).

IFN-γ assay

Production of IFN-γ by T lymphocytes cultured with cytokine-driven allogeneic DC was assessed by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kits (Duoset, R & D, Minneapolis, MN).

Results

Surface membrane characteristics

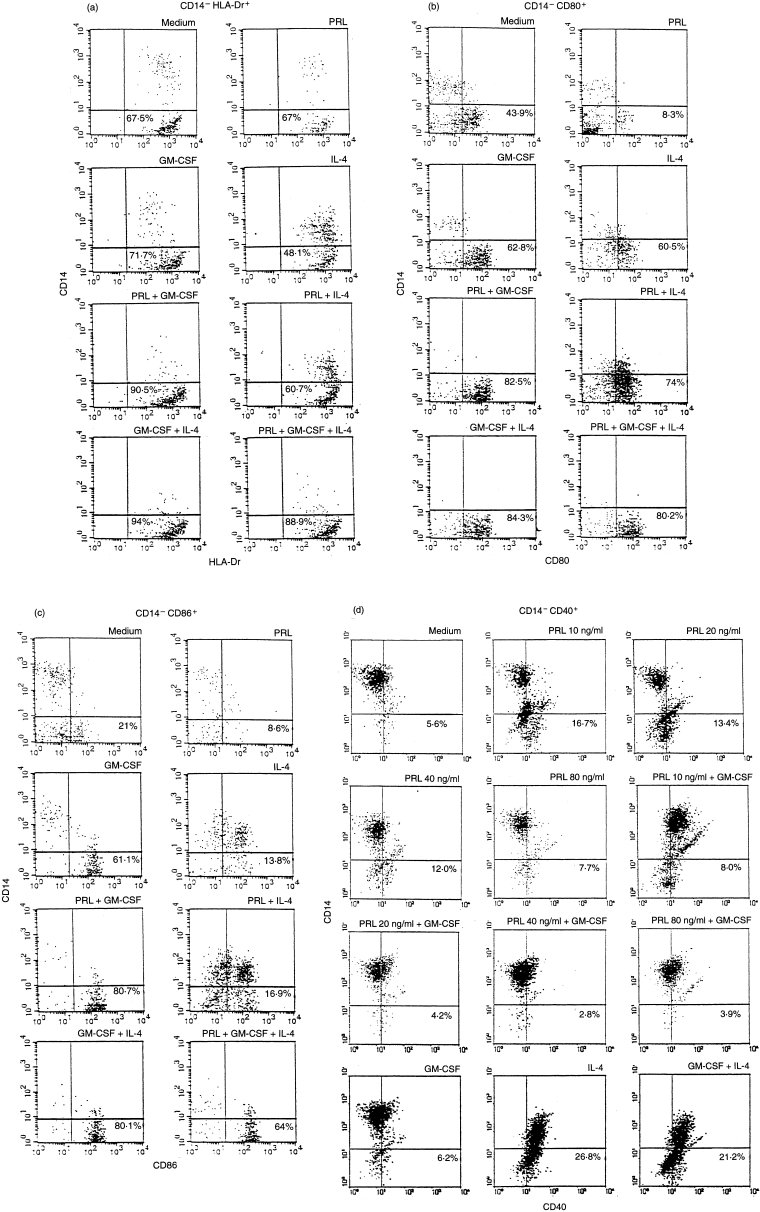

In a first series of experiments, adherent cells, cytokine-driven under serum-free conditions, were tested on day 7 for surface membrane markers. The 20 ng PRL concentration was chosen in the light of our previous findings.19–21 Cells which expressed MHC class II, CD80 (B7-1) and CD86 (B7-2) and which were negative for the monocyte marker CD14 were considered as having the phenotype of cytokine-generated DC. Results from one experiment representative of six are shown in Fig. 1(a, b, c). As expected, GM-CSF and IL-4 acted synergistically to induce a DC phenotype. PRL alone had no effect on MHC II molecule expression (67% versus 67·5% in control), but was highly synergistic (90·5% versus 71·7% P = 0·002) on GM-CSF-induced up-modulation (Fig. 1a). The expression of CD80 (Fig. 1b) and CD86 (Fig. 1c) was strongly decreased by PRL (43·9% versus 8·3% and 21% versus 8·6%) alone which, however, acted synergistically with GM-CSF to increase their expression (62·8 versus 82·5% P = 0·009 and 61·1% versus 80·7% P = 0·014). No change in CD1a expression was induced by PRL alone, nor did it have any effect on GM-CSF induced CD1a expression (54% GM-CSF versus 6% medium alone). By contrast, the association of GM-CSF with IL-4 strongly enhanced CD1a expression (90%) (not shown). The expression of CD40 (Fig. 1d) was unaffected by GM-CSF alone (6·2% versus 5·6% with medium alone), but was enhanced by IL-4 (26·8%). Neither IL-4 nor PRL synergized with GM-CSF (21·2% for IL-4 + GM-CSF and 4·2% for PRL + GM-CSF). However a clear increase (5·6% versus 13·4%) was induced by 20 ng/ml PRL alone. This effect peaked at physiological concentrations (10 ng/ml) and declined at the highest concentrations of the hormone, in accordance with the described bell-shaped pattern.3,4,9 The enhancing effect of PRL on DC40 expression was abrogated by GM-CSF. In line with data form other groups,13,14 CD83, a marker of GM-CSF, IL-4, tumour necrosis factor-α (TNF-α)-driven, mature DC14 was not detected in our cultures (data not shown). Together, this multiple phenotypic analysis shows a superimposable synergistic effect of PRL and IL-4 on GM-CSF-driven surface DC markers. Because hPRL and rhPRL gave superimposable results in this first series of experiments, no distinction is drawn between these two forms in the remainder of the text.

Figure 1.

Flow cytometric analysis of adherent PBMC cultured for 7 days with different GM-CSF/IL-4/PRL combinations. Percentage of cells lacking the monocyte CD14 marker and expressing the MHC II (a), CD80 (b), CD86 (c) and CD40 (d) molecules are shown. Results are from one experiment representative of six (a, b and c) and two (d) done with blood samples from different normal donors. hPRL and rhPRL gave superimposable results.

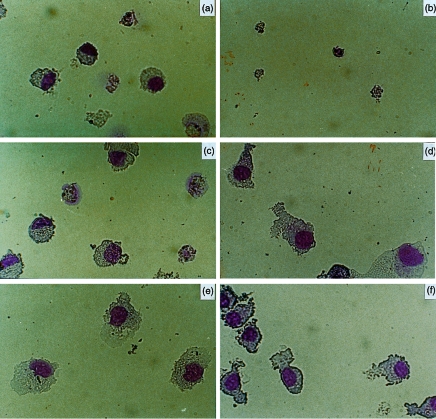

Morphology of cytokine-derived DC

Very low cellularity and absence of granulocyte/DC differentiation were observed in serum-free cultures containing PRL (Fig. 2a) or IL-4 alone (Fig. 2b), whereas GM-CSF was very effective at inducing macrophage-like cells (Fig. 2c). Cells with a typical DC morphology developed in sets stimulated with GM-CSF plus IL-4 (Fig. 2d) and with GM-CSF plus PRL (Fig. 2e). The combination of the three factors (Fig. 2f) induced homogeneous differentiation to DC-like cells, which showed widespread projections and were smaller than DCs of sets D and E.

Figure 2.

Morphological characteristics of cytokine-driven DC. Photographs of May–Grunwald–Giemsa-stained cytospin preparations of adherent monocytes cultured for 7 days with (a) PRL (20 ng), (b) IL-4 (10 ng), (c) GM-CSF (10 ng), (d) GM-CSF and IL-4, (e) GM-CSF and PRL, (f) GM-CSF, IL-4 and PRL. The pattern represented was observed in 10 experiments.

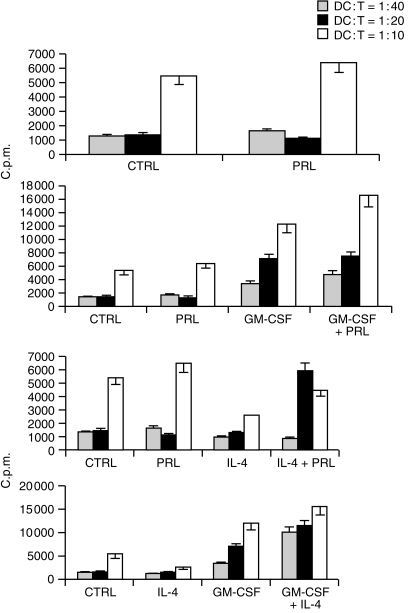

Alloantigen presentation (MLR)

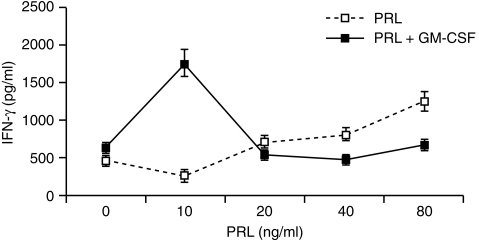

The function of DC is most commonly assessed by their ability to initiate a primary T-cell response. We therefore evaluated our cell populations in terms of their ability to activate highly purified allogeneic T lymphocytes. T-cell activation was assessed by proliferation and/or release of the T helper 1 (Th1)-type cytokine IFN-γ. In preliminary experiments the effect of 20 ng/ml PRL on alloantigen presentation was studied at different DC : T ratios. As shown by others12 DC generated in the absence of serum are low stimulators of MLR, even in standard conditions (i.e. GM-CSF + IL-4).12 Optimal synergistic effect of both PRL and IL-4 on GM-CSF-driven DC differentiation was in fact only observed at the higher DC:T ratio (1 : 10) (Fig. 3, representative of two experiments). Dose–dependence experiments showed inhibition of antigen presentation by DC cultured with 10 ng (P = 0·000) or 20 ng (P = 0·008) PRL alone and enhancement with 80 ng/ml (P = 0·000) (Fig. 4, mean ± SD of five experiments). The latter effect was sensitive to treatment with a 1 : 250 dilution of the IC-5 anti-hPRL serum (not shown). Thus, physiological (10–20 ng/ml) concentrations of PRL were inhibitory when used individually but induced high levels of DC maturation when combined with GM-CSF and the effect was synergistic (PRL 10, GM-CSF net c.p.m. versus GM-CSF net c.p.m. + PRL10 net c.p.m. P = 0·003 and PRL 20, GM-CSF net c.p.m. versus GM-CSF net c.p.m. + PRL 20 net c.p.m. P = 0·02). Superimposable results were obtained with the IFN-γ release from MLR started with CD14+-derived DC (Fig. 5, representative of two experiments).

Figure 3.

Concentration-dependent antigen presentation activity of cytokine-driven DC. Adherent PBMC were cultured for 7 days with PRL (20 ng/ml), GM-CSF (10 ng/ml) and IL-4 (10 ng/ml) or combinations of these factors as indicated and tested for the ability to stimulate allogeneic T lymphocytes at different DC : T ratios. Proliferative response (3H-TdR uptake) was tested on day 4. Results are the mean ± SD c.p.m. from quadruplicate determinations and refer to one experiment of two with similar results.

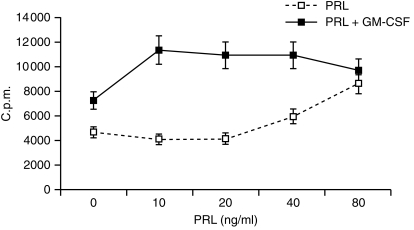

Figure 4.

Dose-specificity of the individual and cooperative effect of PRL. Adherent PBMC were cultured for 7 days with the indicated concentrations of PRL and 10 ng/ml GM-CSF, alone or in combination, and tested for their ability to stimulate allogeneic T lymphocytes at a 10 : 1 T : DC ratio. Proliferative response (3H-TdR uptake) was tested on day 4. Results are the mean ± SD c.p.m. of quadruplicate determinations from five experiments.

Figure 5.

Release of IFNγ in MLR started with CD14 + derived, cytokine-treated DC. CD14+ cells were positively selected with magnetic microbeads and cultured in the same conditions described for Fig. 4. Results (mean ± SD from quadruplicate determinations) refer to one experiment of two with similar results.

Counteracting effect of PRL on down-modulation of the GM-CSF-R

Experiments were performed to assess the possible involvement of receptor cross-modulation in the synergistic effect of PRL on GM-CSF. As shown in Table 1, maximal down-regulation of GM-CSF-R was observed after 72 hr in both the absence of PRL (4807 ± 1005 MESF, P = 0·004) and the presence of its high concentrations (4192 ± 1083 MESF for 80 ng/ml, P = 0·003), but not in the presence of physiological PRL concentrations (means ± SD MESF with 10 and 20 ng/ml PRL were 28 248 ± 2220, P > 0·5. and 21 896 ± 2620, P > 0·5.). The effect of PRL was antagonized by IL-4, which was itself much less effective at counteracting the GM-CSF-R down-modulation.

Table 1.

Expression of GM-CSF-R on cytokine treated adherent PBMC

| Conditions | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| GM-CSF | PRL | IL-4 | MESF* |

| – | – | – | 6229 ± 1892 |

| 10† | – | – | 4807 ± 1005 |

| 10 | 10 | – | 28 248 ± 2220 |

| 10 | 20 | – | 21 896 ± 2620 |

| 10 | 40 | – | 4012 ± 1015 |

| 10 | 80 | – | 4192 ± 1083 |

| 10 | 10 | 10 | 11 490 ± 956 |

| 10 | 20 | 10 | 15 940 ± 1860 |

| 10 | 40 | 10 | 4820 ± 1021 |

| 10 | 80 | 10 | 4001 ± 998 |

| 10 | – | 10 | 14 150 ± 1500 |

Adherent PBMC were obtained immediately (‘uncultured monocytes’) or after a 72–h culture with GM-CSF, PRL or IL-4 alone or in combination, as indicated.

The average number of GM–CSF–R was evaluated by flow cytometry and expressed as MESF (number of molecules of equivalent Fluorochrome) as detailed in Materials and Methods.

ng/ml.

Discussion

PRL has been shown to either interact with lymphohaemopoietic cytokines or mimic their action. Its co-operation with IL-2 in development of lymphokine-activated killer (LAK) cells19–21 and with GM-CSF in maturation of CD34+ stem cells to erythropoietin (EPO)-responsive erythroid progenitors16,17 has been documented by our group. Here we show that physiological concentrations of PRL (10–20 ng/ml) co-operate with GM-CSF in inducing monocytes to differentiate into DC, as judged by their morphological changes, expression of antigen-presenting and costimulatory molecules MHC II, CD80 and CD86, and ability to present alloantigens to CD4 T lymphocytes.

Based on our previous studies,19–21 the concentration of 20 ng/ml PRL was chosen in the first series of experiments to address its role in GM-CSF- and/or IL-4-driven DC differentiation under serum-free conditions. It was found that this concentration synergized with GM-CSF, but not with IL-4, in inducing a DC membrane phenotype (Fig. 1). Expression of the costimulatory molecule CD40 was promoted by the same concentrations of PRL, but this enhancement only occurred in the absence of GM-CSF (Fig. 1d). PRL had no effect on the GM-CSF-induced expression of the non-MHC encoded class I-like molecule CD1a, which is primarily expressed on antigen-presenting cells,22 whereas IL-4 was highly synergistic with GM-CSF (not shown in Fig. 1). Addition of PRL to the combination of GM-CSF and IL-4 inhibited both the membrane phenotype (Fig. 1) and the function (not shown) of 7-day-cultured monocytes. Morphological analysis repeatedly showed a highly homogeneous population of intermediate macrophage–dendritic cells with cytoplasm projections and smaller than cells matured with GM-CSF + IL-4 or GM-CSF + PRL (Fig. 2). MLR experiments (Figs 3, 4 and 5) showed that physiological (but not pharmacological) concentrations of PRL act in concert with GM-CSF to increase the antigen-presenting activity of day 7 treated DC.

In line with the co-operative effect described here, physiological concentrations of PRL have been shown in previous reports19–21 to synergize with low, per se ineffective doses of IL-2 to induce optimal LAK maturation of natural killer (NK) cells in vitro.

PRL alone inhibited the antigen-presenting activity of DC at physiological concentrations, but strongly increased this DC function at higher concentrations. The fact that different concentrations of PRL can activate distinct functions may reflect the existence of receptors with different binding affinities,4 coupled to distinct downstream activatory pathways. Differences in the response elicited by different concentrations of PRL may also be dictated by the cell type. A similar dose-specific effect of PRL has also been reported by us on NK cells.19 However, in that system stimulation peaked at physiological concentrations, very close to the Kd of the PRL receptor on T, B and NK cells,23,24 whereas high concentrations were inhibitory. It is worth noting that the same effect has been observed here on the expression of CD40.

Amplification of the GM-CSF action by PRL is in line with the existence of a cross-talk between haemopoietin/cytokine superfamily receptors. This may occur either at the level of post-receptor signalling, as it is the case for PRL and IL-2,25 or at the level of receptor expression. In a previous study, PRL was in fact shown to up-modulate the EPO-R on CD34+ haemopoietic progenitors.16 In the present study, protection from GM-CSF-R down modulation by PRL may have resulted in an increased response to GM-CSF added in culture on day 3. However, other mechanisms, such as protection from apoptosis,26 may also explain the PRL requirement for efficient generation of DC under serum-free conditions, as shown by Riedl et al.27 with transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β)-1. This possibility is being explored in our laboratory.

Redundancy is a common feature of lymphohaemopoietic cytokines. In the case of DC, this is exemplified by overlapping activities of IL-3 with GM-CSF28 and of IL-13 with IL-4.29 In the serum-free conditions employed in this study, PRL seems to substitute for IL-4 and the two factors display an apparent antagonism. The possibility that PRL is acting by up-modulating endogenous IL-4 synthesis or by using similar signalling pathways can be ruled out because: (i) IL-4 and PRL induce quite a different array of surface molecules (Fig. 1) and (ii) optimal synergistic effect of PRL on GM-CSF occurs at stringent (serum-free) conditions, whereas optimal IL-4–GM-CSF interaction requires the presence of serum.12

The co-operative action of physiological concentrations of PRL may perhaps be of biological significance during GM-CSF-driven maturation of DC from blood monocytes. However, previous data indicate a direct role for PRL during T-lymphocyte activation. Among the targets of PRL-R, in fact, are the T receptor kinases5,6 and, conversely, TCR triggering induces phosphorylation of the PRL-R (our unpublished data). TCR distal events, such as IL-2-induced T-cell proliferation, are also influenced by or dependent on PRL.30 The finding that PRL alone can only act on DC at pharmacological concentrations seems to indicate that it has no role in the whole process of antigen presentation. However, it must be stressed that the model exploited here, instrumental as it was in establishing co-operation with GM-CSF, did not address the role of PRL during the further stages relevant to T-cell activation: i.e. TNF-α/CD40L mediated progression to matured DC endowed with full antigen-presenting activity and T-cell activatory cytokine release.31,32 Studies in this direction are needed to precisely define the role of PRL in the immune response and hence in tumour/viral cell defence and autoimmune diseases.

Acknowledgments

We wish to acknowledge the generous gift of recombinant hPRL by Genzyme (Cambridge, MA), standard hPRL by the National Hormone and Pituitary Program of the NIDDK and anti-hPRL antiserum by Dr Parlow. We also want to thank Dr Martini (San Giovanni Battista Hospital, Turin, Italy) for CD1a flow cytometric analysis.

This work has been supported by the Italian Ministry of University and Technology Research (MURST).

References

- 1.Horseman ND, Yu-lee LY. Transcriptional regulation by the helix bundle peptide hormones: growth hormone, prolactin, and hemopoietic cytokines. Endocrine Rev. 1994;15:627. doi: 10.1210/edrv-15-5-627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yu-lee LY. Molecular actions of prolactin in the immune system. Proc Soc Exp Biol Med. 1997;215:35. doi: 10.3181/00379727-215-44111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gala RR. Prolactin and growth hormone in the regulation of the immune system. Proc Soc Exp Biol Med. 1991;198:513. doi: 10.3181/00379727-198-43286b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Matera L. Endocrine, paracrine and autocrine actions of prolactin on immune cells. Life Sci. 1996;59:599. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(96)00225-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Montgomery DW, Krumenacker SJ, Buckley AR. Prolactin stimulates phosphorylation of the human T-cell antigen receptor complex and ZAP-70 tyrosine kinase: a potential mechanism for its immunomodulation. Endocrinology. 1998;139:811. doi: 10.1210/endo.139.2.5913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Krumenacker JS, Montgomery DW, Buckley DJ, Gout PW, Buckley AR. Prolactin receptor signaling: shared components with the T-cell antigen receptor in Nb2 lymphoma cells. Endocrine. 1998;9:313. doi: 10.1385/ENDO:9:3:313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Viselli SM, Stanek EM, Mukherjee P, Hymer WC, Mastro AM. Prolactin-induced mitogenesis of lymphocytes from ovariectomized rats. Endocrinology. 1991;129:983. doi: 10.1210/endo-129-2-983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cesario TC, Yousefi S, Carandag G, Sadati N, Le J, Vaziri N. Enhanced yield of gamma interferon in prolactin-treated human peripheral blood mononuclear cells. Proc Soc Exp Biol Med. 1994;205:89. doi: 10.3181/00379727-205-43683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Matera L, Contarini M, Bellone G, Forno B, Biglino A. Up-modulation of interferon-γ mediates the enhancement of spontaneous cytotoxicity in prolactin-activated natural killer cells. Immunology. 1999;98:1. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2567.1999.00893.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Steinman RM. The dendritic cell system and its role in immunogenicity. Ann Rev Immunol. 1991;9:271. doi: 10.1146/annurev.iy.09.040191.001415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sallusto F, Lanzavecchia A. Efficient presentation of soluble antigen by cultured human dendritic cells is maintained by granulocyte–macrophage colony stimulating factor plus interleukin 4 and downregulated by tumor necrosis factor alpha. J Exp Med. 1994;179:1109. doi: 10.1084/jem.179.4.1109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kiertscher SM, Roith MD. Human CD14+ leukocytes acquire the phenotype and function of antigen-presenting dendritic cells when cultured in GM-CSF and IL-4. J Leukocyte Biol. 1996;59:208. doi: 10.1002/jlb.59.2.208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pickl WF, Majdic O, Kohl P, et al. Molecular and functional characteristics of dendritic cells generated from highly purified CD14+ peripheral blood monocytes. J Immunol. 1996;157:3850. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhou LJ, Tedder TF. CD14+ blood monocytes can differentiate into functionally mature CD83+ dendritic cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:2588. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.6.2588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Romani N, Reider D, Heuer M, Ener S, Eibl B, Schuler G. Generation of mature dendritic cells from human blood: an improved method with special regard to clinical applicability. J Immunol Methods. 1996;196:137. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(96)00078-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bellone G, Geuna M, Carbone A, et al. Regulatory action of prolactin on the in vitro growth of CD34+ve human hemopoietic progenitor cells. J Cell Physiol. 1995;163:221. doi: 10.1002/jcp.1041630202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bellone G, Astarita P, Artusio A, et al. Bone marrow stroma-derived prolactin is involved in basal and platelet activating factor-stimulated in vitro erythropoiesis. Blood. 1997;90:21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stacchini A, Fubini L, Aglietta M. Flow cytometric detection and quantitative analysis of the GM-CSF receptor in human granulocyte and comparison with the radioligand assay. Cytometry. 1996;24:374. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0320(19960801)24:4<374::AID-CYTO9>3.0.CO;2-F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cesano A, Oberholtzer E, Contarini M, Geuna M, Bellone G, Matera L. Independent and synergistic effect of interleukin-2 and prolactin on development of T- and NK-derived LAK effectors. Immunopharmacology. 1994;28:67. doi: 10.1016/0162-3109(94)90040-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gaidano G, Contarini M, Pastore C, Saglio G, Matera L. AIDS-related Burkitt's-type lymphomas are a target for lymphokine-activated killers induced by interleukin-2 and prolactin. Proc Soc Exp Biol Med. 1996;213:196. doi: 10.3181/00379727-213-44051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Matera L, Bellone G, Lebrun J, et al. Role of prolactin in the in vitro development of interleukin-2-driven anti-tumoral lymphokine-activated killer cells. Immunology. 1996;89:619. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2567.1996.d01-773.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Porcelli SA. The CD1 family: a third lineage of antigen presenting molecules. Adv Immunol. 1995;59:91. doi: 10.1016/s0065-2776(08)60629-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Russell DH, Kibler R, Matrisian L, Larson DF, Poulos B, Magun B. Prolactin receptors on human T and B lymphocytes. J Immunol. 1985;34:3027. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Matera L, Muccioli G, Cesano A, Bellussi G, Gennazzani E. Prolactin receptors on large granular lymphocytes: dual regulation by cyclosporin A. Brain Behav Immun. 1988;2:1. doi: 10.1016/0889-1591(88)90001-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Buckley AR, Buckley DJ, Leff MA, Hoover DS, Magnosus NS. Rapid induction of Pim-1 expression by prolactin and interleukin-2 in rat Nb2 lymphoma cells. Endocrinology. 1995;136:5252. doi: 10.1210/endo.136.12.7588268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Leff MA, Buckley DJ, Krumenacker JS, Reed JC, Miyashita T, Buckley AR. Rapid modulation of the apoptosis regulatory genes bcl-2 and bax by prolactin in rat Nb2 lymphoma cells. Endocrinology. 1996;137:5456. doi: 10.1210/endo.137.12.8940371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Riedl E, Strobl H, Majdic O, Knapp W. TGF-beta 1 promotes in vitro generation of dendritic cells by protecting progenitor cells from apoptosis. J Immunol. 1997;158:1591. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Caux C, Nanderbliet B, Massacrier C, Durand I, Banchereau J. Interleukin-3 cooperates with tumor necrosis factor alpha for the development of human dendritic/Langerhans cells from cord blood CD34+ hemopoietic progenitor cells. Blood. 1996;87:2376. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Piemonti L, Bernasconi S, Luini W, et al. IL-13 supports differentiation of dendritic cells from circulating precursors in concert with GM-CSF. Eur Cytokine Netw. 1995;6:245. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Clevenger CV, Russel DH, Appasamy PM, Prystowsky MB. Regulation of interleukin 2-driven T-lymphocyte proliferation by prolactin. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1990;87:6460. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.16.6460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nakajima A, Kodama T, Morimoto S, et al. Antitumor effect of CD40 ligand: elicitation of local and systemic antitumor response by IL-12 and B7. J Immunol. 1997;161:1901. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.De Becker G, Moulin V, Tielemans T, Urbain J, Leo O, Moser M. Regulation of T helper cell differentiation in vivo by soluble and membrane proteins provided by antigen-presenting cells. Eur J Immunol. 1998;28:3161. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-4141(199810)28:10<3161::AID-IMMU3161>3.0.CO;2-Q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]