Abstract

Ly-49A is a member of the Ly-49 family of mouse natural killer cell receptors that inhibit cytotoxicity upon recognition of their ligands, the major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class I molecules, on the target cell surface. Although Ly-49A has an immunoreceptor tyrosine-based inhibition motif (ITIM) in its cytoplasmic tail, relatively little is known about the mechanisms underlying its inhibitory function. We report here that antibody-mediated co-ligation of the B-cell receptor (BCR) with the transfected Ly-49A molecule results in abrogation of BCR-induced interleukin-2 (IL-2) secretion and mild reduction in activation of Erk1/2 and p38 mitogen-activated protein (MAP) kinases in the B-cell line A20. Surprisingly, BCR-induced calcium mobilization was unaffected by cross-linking of BCR with Ly-49A. Furthermore, substitution of the single tyrosine residue in ITIM with phenylalanine, did not result in a complete loss of inhibitory function, as measured by BCR-induced IL-2 secretion. Deletion of the N-terminal 37 amino acid peptide, which includes the ITIM, did abrogate the inhibitory activity. Co-immunoprecipitation experiments revealed that, upon induction of tyrosine phosphorylation, Ly-49A recruits tyrosine phosphatase src-homology 2 (SH2) containing tyrosine phosphatases-1 (SHP-1), but not inositol phosphatase src-homology 2 (SH2) containing inositol phosphatase (SHIP), and that the tyrosine residue in the ITIM is critical for this interaction. These results suggest that transfected Ly-49A utilizes two different inhibitory mechanisms in B-cell signalling: ITIM-dependent and ITIM-independent.

Introduction

Activation signals delivered through the B-cell receptor (BCR) or T-cell receptor (TCR) on lymphocytes initiate a biochemical signalling cascade, which is characterized by tyrosine phosphorylation of multiple proteins and calcium mobilization. 1, 2 The initial phase of the cascade involves tyrosine phosphorylation of a consensus motif called immunoreceptor tyrosine-based activation motif (ITAM) which is contained in the receptor cytoplasmic domains. The phosphorylated ITAM binds Syk-family protein tyrosine kinases (PTKs), such as Syk and ZAP70, via their tandem Src-homology 2 (SH2) domains, which in turn activates these enzymes and trigger downstream signalling pathways. 1, 2

These activation signalling pathways are regulated by co-receptors, whose specific function is to downregulate cell activation, and their inhibitory function is mediated by phosphatases. 3 These inhibitory molecules contain in their cytoplasmic tail a well-conserved motif that resembles ITAM, thus called ITIM for immunoreceptor tyrosine-based inhibition motif. The best-characterized ITIM-containing inhibitory receptor is probably FcγRIIB. Upon co-clustering with BCR by intact anti-BCR antibody, FcγRIIB becomes phosphorylated on the tyrosine residue of its ITIM, and mediates inhibition of BCR-induced biochemical events such as calcium influx. 4–7 Once phosphorylated, the tyrosine residue in the FcγRIIB ITIM binds two SH2 domain-containing effector molecules: tyrosine phosphatase (SHP-1) 8 and inositol phosphatase (SHIP). 9 Using B cells rendered deficient in either phosphatase by homologous recombination, it was shown that SHIP, but not SHP-1, is the critical component of the inhibitory pathway mediated by FcγRIIB. 7 Another example of inhibitory co-receptor, cytotoxic T lymphocyte antigen-4 (CTLA-4), does not have a typical ITIM, however, it has an ITIM-like motif (YVKM) in the cytoplasmic domain, and if phosphorylated, this motif has the capacity to bind another SH2 domain-containing phosphatase, SHP-2. 10, 11

Cytotoxicity of natrual killer (NK) cells is also regulated by two types of surface receptors: the poorly characterized activating receptors which recognize target cells and trigger cytotoxicity, and the major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class I-specific receptors, which inhibit cytotoxicity against target cells expressing their ligands. 12, 13 Thus, NK cells kill tumours lacking MHC class I molecules, while MHC class I molecules on target cells tend to inhibit NK cell-mediated cytotoxicity.

Inhibitory NK cell receptors fall into two structurally distinct superfamilies. The first consists of immunoglobulin-like receptors, which are type I integral membrane pro- teins, 14–17 whereas the second superfamily includes C-type lectin receptors, which are disulphide-linked dimeric type II integral membrane proteins. 18, 19 Though structurally unrelated, both groups of inhibitory receptors contain ITIM. 12, 13 The prototype receptors of the first group, killer cell inhibitory receptors (KIRs), are capable of inhibiting the initial phase of activation signals, including intracellular calcium mobilization. 7, 20 However, in contrast to FcγRIIB, the inhibitory mechanism involves SHP-1 but not SHIP. 7, 21–26 As in the case of FcγRIIB, the tyrosine residue of killer cell inhibitory receptor (KIR) ITIM is phosphorylated upon ligation and is essential for inhibition. 7, 21–26 The best known example of the second, C-type lectin group of inhibitory receptors is Ly-49A. 18, 27 However, the signalling mechanisms through Ly-49A have been less thoroughly investigated, partly because of difficulties in establishing an appropriate model.

In the present study, we transfected Ly-49A cDNA to the B-cell line A20 to study the inhibitory function of Ly-49A 18, 27 on BCR-mediated signalling. A20 cells express BCR IgG and BCR-stimulated A20 cells initiate a series of signalling events, such as tyrosine phosphorylation and calcium mobilization, leading to production and secretion of interleukin-2 (IL-2). 5, 6 Because similarities between BCR-induced signalling and target cell-induced NK cell activation have been suggested by the similar sets of biochemical activation events such as calcium mobilization, we postulated that, although artificial, this system may shed some light on the mechanisms of inhibitory signalling through Ly-49A. In keeping with this hypothesis, it has been recently observed that both B-cell and NK cell activation appear to be triggered through Syk kinase activation. 28, 29

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cells and antibodies

Murine B lymphoma line A20 (American Type Culture Collection, Rockville, MD) and its transfectants were maintained in RPMI-1640, supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (FBS) and 50 µm 2-mercaptoethanol (2-ME) at 37°. F(ab′)2 fragments of anti-Ly-49A monoclonal antibody (mAb) A1 was generated from ascites of the hybridoma clone (a gift from Dr J. Allison, University of California, Berkeley, CA) using HiTrap protein-A columns (Pharmacia Biotech Inc., Piscataway, NY) and Immunopure F(ab′)2 Preparation Kit (Pierce, Rockford, IL). The following antibodies were purchased for this study: fluoroscein isothiocyanate (FITC)-conjugated anti-Ly-49A mAb A1 (PharMingen, San Diego, CA); intact and F(ab′)2 fragment of goat anti-mouse immunoglobulin (IgG) antibodies (GAM) (BioSource International, Camarillo, CA); anti-phosphotyrosine mAb 4G10 (mouse, IgG2b) and anti-SHP-1 antibody (rabbit polyclonal) (Upstate Biotechnology Inc., Lake Placid, NY); anti-SHIP antibody (rabbit polyclonal) (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc., Santa Cruz, CA); horseradish peroxidase (HRP) conjugated anti-mouse and anti-rabbit antibodies (Amersham International, Amersham, UK); anti-Erk1/2, anti-phospho Erk1/2, anti-p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK), and anti-phospho p38 MAPK antibodies (New England Biolabs, Inc., Beverly, MA).

cDNA constructs and transfection

Full-length mouse Ly-49A cDNA was isolated by reverse transcription–polymerase chain reaction (RT–PCR). Mutant Ly-49A in which either tyrosine at position 8 in ITIM was substituted with phenylalanine (Y/F) or N-terminal 37 amino acids containing ITIM were deleted (ΔN37), were created by PCR. These cDNAs were confirmed by sequencing and subsequently transferred to an expression vector pApuro. 28 A20 cells were transfected with 20 µg of linearized plasmids by electroporation (975 µF, 250 V). After about 2 weeks of puromycin selection, cell surface expression of Ly-49A was analysed by FACSCalibur (Becton-Dickinson, Mountain View, CA) using FITC-conjugated anti-Ly-49A mAb.

Cell stimulation and measurement of IL-2

Cells (5 × 105/ml) were preincubated with anti-Ly-49A F(ab′)2 mAb (0·4 µg/ml) at 37° for 30 min, then stimulated by GAM F(ab′)2 (32 µg/ml) for 18 hr at 37° in a 96-well plate, unless otherwise stated. IL-2 concentration in supernatants were assayed by Quantikine-M Mouse IL-2 Immunoassay kit (R & D systems, Abingdon, UK). IL-2 content in the supernatant of a given clone following stimulation with both GAM F(ab′)2 and anti-Ly-49A F(ab′)2 mAb is expressed as a percentage of IL-2 content after stimulation only with GAM F(ab′)2.

Calcium analysis

Cells were loaded with Fluo-3/AM (2 mm) (Wako, Tokyo, Japan) and preincubated or not with anti-Ly-49A F(ab′)2 mAb (0·4–1·6 µg/ml, 1–30 min, 37°), Fluorescence of the stimulated cell suspension was continuously monitored by FACSCalibur using CellQuest software (Becton-Dickinson). Events were gated at 20-s intervals before and after stimulation, and mean fluorescence intensity was calculated in each gate.

Western blotting and immunoprecipitation

Cells preincubated with or without anti-Ly-49A F(ab′)2 mAb (0·4 µg/ml, 30 min, 37°) were stimulated with GAM F(ab′)2 (32 µg/ml) and lysed at various time intervals using sodium dodecyl sulphate (SDS) buffer (62·5 mm Tris–HCl pH 6·8, 2% SDS, 10% glycerol, 5% 2-ME, 0·001% bromphenol blue). Lysates were separated by 4–20% SDS gradient polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE; Daiichi, Tokyo, Japan). Blots were detected with appropriate antibodies and enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL) system (Amersham). In MAPK (Erk1/2 and p38) activation experiments, densitometry measurements of bands detected with anti-MAPK or anti-phospho MAPK were carried out using ImageQuant (Molecular Dynamics, Inc., Sunnyvale, CA). To quantify the extent of MAPK phosphorylation at each post-activation time point, the ratio of band intensities detected by anti-phospho-MAPK and anti-MAPK was indexed to the value before stimulation. For anti-Ly-49A immunoprecipitation, cells were stimulated for 10 min with 0·03% H2O2 and 100 mm sodium orthovanadate (pervanadate). Cells were solubilized in lysis buffer (1% NP40, 150 mm NaCl, 20 mm Tris pH 7·5, and 1 mm ethylenediamine tetra-acetic acid (EDTA)) containing 50 mm NaF, 0·2 mm sodium orthovanadate, and protease inhibitors (1 mm phenylmethylsulphonyl fluoride (PMSF), 2 µg/ml aprotinin, 10 µg/ml leupeptin, 10 µg/ml chymostatin). Precleared lysates were sequentially incubated with anti-Ly-49A mAb and protein-A agarose beads (Pierce). Precipitated samples were dissolved in SDS buffer without 2-ME, and analysed as described above.

Results

Ly-49A mediates inhibition of BCR-induced B-cell activation

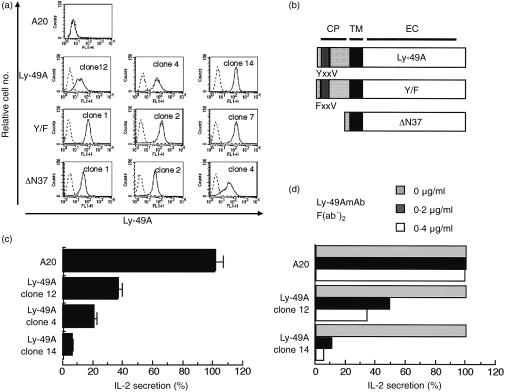

To express Ly-49A molecules on B cells, we transfected mouse B-cell line A20 with Ly-49A cDNA in an expression vector, and established several clones of stable transfectants (Fig. 1a).

Figure 1.

(a) Expression of wild-type and mutant Ly-49A in transfected A20 cells. Cells were incubated with (solid line) or without (broken line) FITC-conjugated anti-Ly-49A mAb, and analysed by FACSCalibur. (b) Schematic representation of wild-type and mutated Ly-49A molecules. CP, cytoplasmic domain. TM, transmembrane domain. EC, extracellular domain. In Y/F mutant, tyrosine in ITIM was substituted by phenylalanine, whereas N-terminal 37 amino acids were deleted in ΔN37 mutant. (c) A20 and transfectant clones expressing different levels of Ly-49A were preincubated with or without anti-Ly-49A mAb F(ab′)2 and then stimulated with GAM F(ab′)2. Bars represent IL-2 content in the supernatants with anti-Ly-49A mAb F(ab′)2 preincubation as a percentage of IL-2 content without anti-Ly-49A mAb F(ab′)2. The mean and standard deviation of three independent experiments are shown. (d) Inhibition of IL-2 secretion is dependent on the amount of anti-Ly-49A mAb F(ab′)2 used for pretreatment. Non-transfected A20, clone 12, and clone 14 were preincubated in indicated concentrations of anti-Ly-49A mAb F(ab′)2, and stimulated for 18 hr with GAM F(ab′)2. The results were representative of two independent experiments.

To ligate BCR and Ly-49A molecules on the surface of A20 cells simultaneously, cells were pretreated with or without F(ab′)2 fragment of mAb A1 (mouse IgG2a), then stimulated with F(ab′)2 fragments of GAM. This mode of simulation may potentially produce three kinds of cross-linking at the cell surface: (1) simple cross-linking of BCR (2) co-cross-linking of BCR with A1-bound Ly-49A, and (3) cross-linking of A1-bound Ly-49A alone. We used F(ab′)2 fragment of both antibodies, because intact antibodies could cross-link BCR with another inhibitory receptor expressed on A20 cells, FcγRIIB. 4–6 After an 18-hr incubation, culture supernatants were collected, and a sandwich enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) method was used to quantify the IL-2 concentration in the medium.

When stimulated only by F(ab′)2 of GAM, both parental A20 and Ly-49A transfectants secreted comparable amounts of IL-2 into culture medium (data not shown). In contrast, pretreatment of the transfectants with F(ab′)2 fragment of anti-Ly-49A, followed by GAM F(ab′)2, resulted in 60–90% inhibition of IL-2 secretion depending on the clone of transfectants (Fig. 1c). The degree of inhibition of IL-2 secretion correlated with the level of Ly-49A expression (compare Fig. 1a, c). Furthermore, concentration of mAb A1 F(ab′)2 used for the pretreatment also correlated with the extent of inhibition (Fig. 1d). IL-2 secretion by parental A20 was not affected by the treatment (Fig. 1c, d). Thus, cross-linking with transfected Ly-49A receptor interrupts BCR-induced IL-2 secretion in A20 cells. In the following studies of signalling events, we used transfectant clone 14, which expresses Ly-49A at a high level.

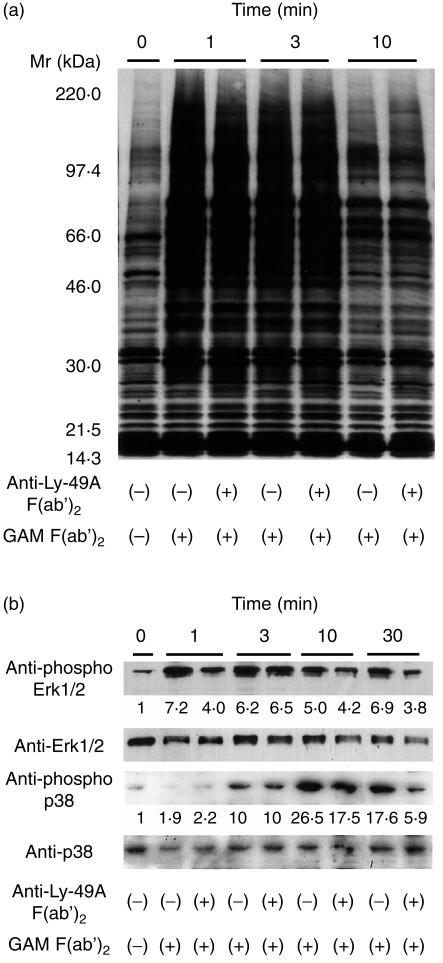

Induction of tyrosine phosphorylation in various cellular proteins is one of the crucial events detected immediately after BCR cross-linking. 1, 2, 28 As shown in Fig. 2(a), neither the kinetics nor the degree of tyrosine phosphorylation was altered in cells pretreated with Ly-49A mAb when compared to untreated cells. These data suggest that inhibitory signalling through Ly-49A does not affect activation of tyrosine kinases induced by BCR stimulation, although we cannot exclude subtle changes in tyrosine phosphorylation that may be undetectable by our method.

Figure 2.

(a) Ly-49A does not alter BCR-induced tyrosine phosphorylation. Ly-49A transfectant (clone 14) was preincubated with or without anti-Ly-49A mAb F(ab′)2, and stimulated with GAM F(ab′)2. Cells were lysed at indicated time intervals and separated by SDS–PAGE under reducing conditions, and analysed by Western blotting with anti-phosphotyrosine mAb 4G10. (b) MAP kinase activity was partially inhibited by Ly-49A. A20 cells expressing Ly-49A molecules (clone 14) were preincubated with or without anti-Ly-49A mAb F(ab′)2 and stimulated with GAM F(ab′)2. Cells were lysed at indicated time intervals, and analysed by western blotting with antibodies specific for phosphorylated forms of either Erk1/2 or p38 MAPK. The membranes were then stripped and reprobed by antibodies specific for Erk1/2 or p38 MAPK, respectively. The numbers represent stimulation indices calculated from densitometric data, as described in Materials and methods. Results shown are representative of at least five independent experiments.

Ly-49A-mediated effects on BCR-induced activation of MAPK were examined next. MAPK activation is probably a crucial step leading to IL-2 gene transcription. 30 Of the three known families of MAPK, we tested the activation of classic MAPK, Erk1/2, and p38 MAPK. Using a polyclonal antibody that specifically recognizes the phosphorylated form of Erk1/2, we detected rapid phosphorylation of Erk1/2 (Fig. 2b). Also, with a similar approach using anti-phosphorylated p38 polyclonal antibody, BCR-induced activation of p38 MAPK was detected with slower kinetics than that of Erk1/2. To ensure equal loading of proteins onto PAGE, blots were reprobed with antibody against total Erk1/2 or p38 MAPK. Densitometry measurements showed that co-ligation of BCR with Ly-49A downregulated the degree of phosphorylation of Erk1/2 and p38 MAPK (Fig. 2b). For example, at 30 min after stimulation, the activation was reduced to about half in Erk1/2, and to about 30% in p38 MAPK. BCR-induced activation of Erk1/2 and p38 MAPKs in parental A20 cells was not affected by preincubation with anti-Ly-49A mAb F(ab′)2 (data not shown). These results indicate that inhibitory signalling through Ly-49A somehow modulates Erk1/2 and p38 activation. However, the inhibition on Erk1/2 and p38 activation seems to be rather mild, suggesting that target of Ly-49A-mediated inhibitory signalling may be not limited to Erk1/2 and p38.

Negative signalling pathways through Ly-49A and FcγRIIB display distinct patterns of intracellular calcium mobilization

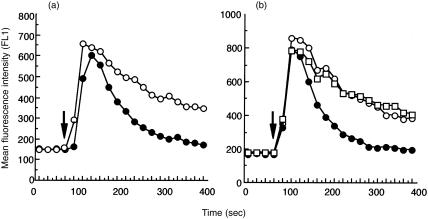

Next, we proceeded to examine how antibody-mediated Ly-49A cross-linking affects BCR-induced calcium mobilization in our transfectants. In both parental and Ly-49A-expressing A20 cells, stimulation by GAM F(ab′)2 alone induced similar patterns of calcium mobilization, as shown in Fig. 3. Intact GAM stimulation, which cross-links BCR and FcγRIIB, resulted in less prominent calcium mobilization (Fig. 3, compare open and filled circles). The depressed calcium response by intact GAM is probably due to closure of plasma membrane calcium channels, because depletion of extracellular calcium by 1 mm egtazic acid (EGTA) affected calcium mobilization less in case of intact GAM stimulation as compared to GAM F(ab′)2 stimulation (data not shown). These results are in agreement with previous reports. 4–7, 9

Figure 3.

Ly-49A does not alter calcium mobilization induced by BCR stimulation. A20 cells (a) and cells of Ly-49A transfectant (clone 14) (b) (107 each) were loaded with fluo-3/AM, then incubated with (rectangle) or without (open circle or filled circle) anti-Ly-49A mAb F(ab′)2. Intracellular calcium concentration was continuously monitored by FACSCalibur. Cells were stimulated by either GAM F(ab′)2 (open circle or rectangle) or intact GAM (filled circle). Results are representative of at least five separate experiments.

Unexpectedly, however, co-ligation of Ly-49A and BCR resulted in a pattern of calcium mobilization indistinguishable from that following stimulation by GAM F(ab′)2 alone (Fig. 3b, compare open circles and rectangles). Because it was possible that GAM F(ab′)2 induced clustering of BCR alone without cross-linking with sufficient numbers of Ly-49A molecules, we tested the concentration of anti-Ly-49A mAb F(ab′)2 ranging from 0·4 to 1·6 µg/ml, and the length of preincubation time between 1 and 30 min. In repeated experiments, we were unable to observe any suppression of calcium mobilization from control levels of mobilization which occurred in the absence of pretreatment with anti-Ly-49A mAb F(ab′)2, despite the fact that, under the same conditions, IL-2 secretion was markedly inhibited. Anti-Ly-49A mAb F(ab′)2 treatment alone did not induce any changes in intracellular calcium levels (data not shown). Thus, FcγRIIB and Ly-49A displayed drastically different effects on BCR-induced calcium mobilization.

Tyrosine phosphorylated Ly-49A recruits SHP-1, but not SHIP, to its ITIM

To further analyse the mechanisms of inhibition mediated by Ly-49A, we introduced mutations into the cytoplasmic domain of Ly-49A and expressed the mutagenized receptors in A20 cells (Fig. 1a, b). The Y/F mutant, in which the tyrosine residue at position 8 within the ITIM was substituted by phenylalanine, was expected to disrupt interactions with cytoplasmic effectors such as SHP-1. In mutant ΔN37, out of 44 N-terminal amino acid residues in the cytoplasmic domain, 37 were deleted, including ITIM and the second tyrosine residue at position 36. Expression levels of the mutagenized Ly-49A molecules were comparable to those of the wild-type Ly-49A (Fig. 1a).

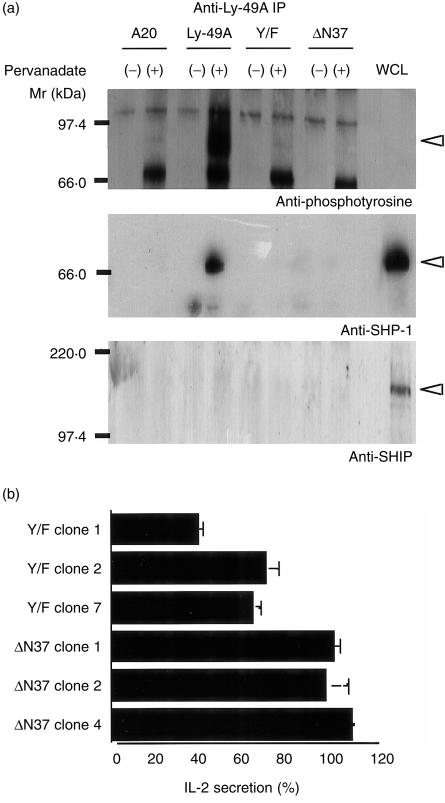

Ly-49A was immunoprecipitated from pervanadate-treated cells and tyrosine phosphorylation was examined by western blotting. We avoided using reducing conditions, because the molecular weight of reduced, monomeric form of Ly-49A (44 000 MW) may be too close to molecular weight of IgG heavy chain (51 000 MW) to resolve by PAGE. As expected, we observed a tyrosine phosphorylated broad band around 85 000 MW that corresponds to the molecular weight of dimerized and glycosylated wild-type Ly-49A protein after pervanadate treatment (Fig. 4a). This phosphorylation was dependent on the tyrosine residue within the ITIM (tyrosine at position 8), but not on the second tyrosine residue at position 36, because the mutant Y/F, which retains the second tyrosine, was not tyrosine phosphorylated (Fig. 4a).

Figure 4.

(a) Ly-49A recruits SHP-1 but not SHIP upon induction of tyrosine phosphorylation. Non-transfected A20 and transfected A20 cells expressing wild-type or mutagenized Ly-49A molecules were incubated with or without pervanadate for 10 min, and then lysed. Anti-Ly-49A immunoprecipitates were resolved by 4–20% SDS–PAGE under non-reducing conditions. The membrane was sequentially immunoblotted first with anti-phosphotyrosine mAb, then with anti-SHP-1 antibody, and finally with anti-SHIP antibody. Whole cell lysates (WCL) of A20 cells were included as positive control. Results are representative of three independent experiments. (b) The tyrosine residue in Ly-49A ITIM is not essential for inhibitory function of Ly-49A in B-cell signalling. Six clones expressing either Y/F mutant or ΔN37 mutant of Ly-49A were tested for inhibition of IL-2 secretion as described in Materials and methods. The results were mean and SD of at least three independent experiments.

Next, the ability of Ly-49A molecules to interact with known cytoplasmic inhibitory effectors, such as SHP-1 and SHIP, was examined following tyrosine phosphorylation by pervanadate treatment. Co-immunoprecipitation of Ly-49A and SHP-1, but not SHIP, was detected only after induction of tyrosine phosphorylation (Fig. 4a). Mutant Ly-49A molecules failed to coprecipitate either SHP-1 or SHIP, with or without pervanadate treatment. This is expected because of lack of tyrosine phosphorylation in either mutant. Thus, tyrosine phosphorylated Ly-49A interacts with SHP-1, but not with SHIP, and this interaction is dependent solely on the tyrosine residue in ITIM. These results are in agreement with earlier studies that demonstrated physical interactions between phosphorylated Ly-49A and SHP-1. 31–33

Ly-49A is able to transmit inhibitory signals independent of ITIM/SHP-1 interaction

Functional consequences of the disrupted interaction between Ly-49A and SHP-1 were examined in transfectants expressing mutant Ly-49A molecules. Previous reports suggested that tyrosine residues in the ITIM are crucial for inhibitory functions of receptors such as KIRs and FcγRIIB. 6, 24 Surprisingly, however, Ly-49A molecules bearing the Y/F substitution were able to inhibit IL-2 secretion by as much as 40–60% in three independent clones tested, whereas the ΔN37 mutant retained no inhibitory capacity (Fig. 4b). These results indicate that, despite the well-established role of ITIM in inhibitory signalling, Ly-49A ITIM is not solely responsible for the inhibition of BCR-induced IL-2 secretion. In addition, the structural information required for the ITIM-independent inhibition appears to be localized within the N-terminal 37 amino acid residues, as indicated by the fact that the mutant ΔN37 is incapable of inhibition.

Discussion

We have found that transfected Ly-49A is capable of inhibiting BCR-induced IL-2 secretion when it is cross-linked with BCR. Furthermore, our data revealed two unexpected features of inhibitory signalling by Ly-49A. First, contrary to the situation in other inhibitory receptors such as FcγRIIB, mutant Ly-49A molecule which lacks the tyrosine residue within ITIM was able to deliver inhibitory signals, at least in part. Second, calcium mobilization was not altered even under conditions that definitely abrogate IL-2 secretion.

Recent studies showed that there are two inhibitory signalling pathways in ITIM-containing receptors; the SHIP-dependent and the SHP-1-dependent pathways. 3 We have found that Ly-49A molecule recruits SHP-1, not SHIP, upon induction of tyrosine phosphorylation by pervanadate. Although only about half of inhibitory capacity of Ly-49A was shown to be dependent on tyrosine residue of ITIM, there is a clear correlation between tyrosine phosphorylation of Ly-49A ITIM and association with SHP-1. Thus, it seems reasonable to conclude that inhibitory signalling through Ly-49A is in part mediated by ITIM and SHP-1. Another half of inhibitory function is mediated by unknown mechanisms.

A previous study examined inhibitory signalling, using target cell killing by Ly-49A-transfected rat NK cell line as the main functional assay. 31 There are a number of important differences between the aforementioned study and our present results. First, in contrast to the earlier results, we failed to detect any inhibition of tyrosine phosphorylation mediated by Ly-49A. Second, it has been reported that Ly-49A inhibits phosphoinositide turnover, 31 but no alteration in BCR-induced calcium mobilization was observed in our model. Phosphoinositide turnover, such as InsP3 generation, is likely to be necessary for a calcium response, implying that co-ligation with Ly-49A may not inhibit BCR-induced InsP3 generation in our model. Third, the Y/F substitution in ITIM abrogated inhibition of cytotoxicity in rat NK cell line model, 31 but the Y/F mutant was partially inhibitory for IL-2 secretion in our model.

These differences between the two studies could be attributed to the marked differences in the cell type used, or in the methods of receptor co-ligation employed. Thus, we could not exclude the possibility that our findings only apply to inhibitory signalling mediated by Ly-49A expressed in B cells. For example, compared to activating signals delivered through undefined NK receptors upon contact with target cells, polyclonal antibody-mediated BCR cross-linking might elicit much stronger signals to the cell. If intrinsic capacity of Ly-49A molecule to inhibit cell activation is relatively weak, yet sufficient for inhibiting IL-2 secretion, this might explain why we found no suppression of early signalling events such as tyrosine phosphorylation. It has been shown earlier that phosphorylated peptide corresponding to Ly-49A ITIM could bind SHP-1, but in low stoichiometry compared to ITIM of other inhibitory receptors. 32 Alternatively, it is also possible that requirements are different for inhibition of cytotoxicity and inhibition of cytokine secretion. The Ly-49A ITIM may be necessary and sufficient for inhibition of cytotoxicity, 31 but not be sufficient for full inhibition of cytokine response, which may be fully blocked only when a second inhibitory pathway is also engaged. In any event, our results clearly show the capacity of Ly-49A molecule to transmit inhibitory signals that are independent of the ITIM phosphorylation.

Although unexpected, our finding of calcium-or ITIM-independent inhibitory pathway is not without precedence. For example, the CD81 molecule, which does not have a typical ITIM motif, inhibits FcεRI-mediated degranulation in mast cells without affecting tyrosine phosphorylation or calcium mobilization. 34 Furthermore, a mutant CTLA-4 which lacks tyrosine in the cytoplasmic tail, still delivers a negative signal for cytokine production in a T-cell clone. 11 Collectively, therefore, these results strongly suggest the existence of an additional inhibitory signalling pathway(s) beyond the SHP-1/SHIP paradigm.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research (No.08670519) from the Ministry of Education, Science, and Culture of Japan (K.K.), and National Institute of Health (USA) Grant DK13969 (I.N.). We would like to thank Vita Milisauskas for critical reading of the manuscript, and our colleagues for their continuous support and encouragement.

Abbreviations

- BCR

B-cell receptor

- ITIM

immunoreceptor tyrosine-based inhibition motif

- ITAM

immunoreceptor tyrosine-based activation motif

- KIR

killer cell inhibitory receptor

- FcγRIIB

Fcγ receptor type IIB

- FcεRI

IgE Fc receptor

- PTK

protein tyrosine kinase

- SH2

Src-homology 2

- IL-2

interleukin-2

- GAM

goat anti-mouse IgG antibody

- MAPK

mitogen-activated protein kinase

- PIR-B

paired immunoglobulin-like receptor-B

- InsP3

inositol 1,4,5-triphosphate

References

- 1.Weiss A, Littman DR. Signal transduction by lymphocyte antigen receptors. Cell. 1994;76:263. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90334-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cambier JC. Antigen and Fc receptor signaling. The awesome power of the immunoreceptor tyrosine-based activation motif (ITAM) J Immunol. 1995;155:3281. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Scharenberg AM, Kinet J-P. The emerging field of receptor-mediated inhibitory signaling: SHP or SHIP? Cell. 1996;87:961. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81790-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Choquet D, Partiseri M, Amigorena S, Bonnerot C, Fridman WH, Korn H. Cross-linking of IgG receptors inhibits membrane immunoglobulin-stimulated calcium influx in B lymphocytes. J Cell Biol. 1993;121:355. doi: 10.1083/jcb.121.2.355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Diegel ML, Rankin BM, Bolen JB, Dubois PM, Kiener PA. Cross-linking of Fc gamma receptor to surface immunoglobulin on B cells provides an inhibitory signal that closes the plasma membrane calcium channel. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:11409. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Muta T, Kurosaki T, Misulovin Z, Sanchez M, Nussenzweig MC, Ravetch JV. A 13-amino-acid motif in the cytoplasmic domain of Fc gamma RIIB modulates B-cell receptor signalling. Nature. 1994;368:70. doi: 10.1038/368070a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ono M, Okada H, Bolland S, Yanagi S, Kurosaki T, Ravetch JV. Deletion of SHIP or SHP-1 reveals two distinct pathways for inhibitory signaling. Cell. 1997;90:293. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80337-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.D'ambrosio D, Hippen KL, Minskoff SA, et al. Recruitment and activation of PTP1C in negative regulation of antigen receptor signaling by Fc gamma RIIB1. Science. 1995;268:293. doi: 10.1126/science.7716523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ono M, Bolland S, Tempst P, Ravetch JV. Role of the inositol phosphatase SHIP in negative regulation of the immune system by the receptor FcγRIIB. Nature. 1996;383:263. doi: 10.1038/383263a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Maréngere LEM, Waterhouse P, Duncan GS, Mittrücker H-W, Feng G-S, Mak TW. Regulation of T cell receptor signaling by tyrosine phosphatase SYP association with CTLA-4. Science. 1996;272:1170. doi: 10.1126/science.272.5265.1170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Saito T. Negative regulation of T cell activation. Curr Opin Immunol. 1998;10:313. doi: 10.1016/s0952-7915(98)80170-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lanier LL. NK cell receptors. Annu Rev Immunol. 1998;16:359. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.16.1.359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yokoyama WM. Natural killer cell receptors. Curr Opin Immunol. 1998;10:298. doi: 10.1016/s0952-7915(98)80168-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Colonna M, Samaridis J. Cloning of immunoglobulin-superfamily members associated with HLA-C and HLA-B recognition by human natural killer cells. Science. 1995;268:405. doi: 10.1126/science.7716543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wagtmann N, Biassoni R, Cantoni C, et al. Molecular clones of the p58 NK cell receptor reveal immunoglobulin-related molecules with diversity in both the extra- and intracellular domains. Immunity. 1995;2:439. doi: 10.1016/1074-7613(95)90025-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.D'andrea A, Chang C, Franz-Bacon K, McClanahan T, Phillips JH, Lanier LL. Molecular cloning of NKB1. A natural killer cell receptor for HLA-B allotypes. J Immunol. 1995;155:2306. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wang LL, Mehta IK, Leblanc PA, Yokoyama WM. Mouse natural killer cells express gp49B1, a structural homologue of human killer inhibitory receptors. J Immunol. 1997;158:13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yokoyama WM, Jacobs LB, Kanagawa O, Shevach EM, Cohen DI. A murine T lymphocyte antigen belongs to a supergene family of type II integral membrane proteins. J Immunol. 1989;143:1379. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lazetic S, Chang C, Houchins JP, Lanier LL, Phillips JH. Human natural killer cell receptors involved in MHC class I recognition are disulfide-linked heterodimers of CD94 and NKG2 subunits. J Immunol. 1996;157:4741. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Blery M, Delon J, Trautmann A, et al. Reconstituted killer cell inhibitory receptors for major histocompatibility complex class I molecules control mast cell activation induced via immunoreceptor tyrosine-based activation motifs. J Biol Chem. 1997;27:8989. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.14.8989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Burshtyn DN, Scharenberg AM, Wagtmann N, et al. Recruitment of tyrosine phosphatase HCP by the killer cell inhibitory receptor. Immunity. 1996;4:77. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Campbell KS, Dessing M, Lopez-Botet M, Cella M, Colonna M. Tyrosine phosphorylation of a human killer inhibitory receptor recruits protein tyrosine phosphatase 1C. J Exp Med. 1996;184:93. doi: 10.1084/jem.184.1.93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gupta N, Scharenberg AM, Burshtyn DN, et al. Negative signaling pathways of the killer cell inhibitory receptor and FcγRIIb1 require distinct phosphatases. J Exp Med. 1997;186:473. doi: 10.1084/jem.186.3.473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fry AM, Lanier LL, Weiss A. Phosphotyrosines in the killer cell inhibitory receptor motif of NKB1 are required for negative signaling and for association with protein tyrosine phosphatase 1C. J Exp Med. 1996;184:295. doi: 10.1084/jem.184.1.295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Binstadt BA, Brumbaugh KM, Dick CJ, et al. Sequential involvement of Lck and SHP-1 with MHC-recognizing receptors on NK cells inhibits FcR-initiated tyrosine kinase activation. Immunity. 1996;5:629. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80276-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Vely F, Olivero S, Olcese L, et al. Differential association of phosphatases with hematopoietic co-receptors bearing immunoreceptor tyrosine-based inhibition motifs. Eur J Immunol. 1997;27:1994. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830270825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zheng WP, Kiura K, Milisauskas VK, Denardin E, Nakamura I. Murine NK cell allospecificity-1 is defined by inhibitory ligands. J Immunol. 1996;156:4651. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Takata M, Sabe H, Hata A, et al. Tyrosine kinases Lyn and Syk regulate B cell receptor-coupled Ca2+ mobilization through distinct pathways. EMBO J. 1994;13:1341. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1994.tb06387.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Brumbaugh KM, Binstadt BA, Billadeau DD, et al. Functional role for Syk tyrosine kinase in natural killer cell-mediated natural cytotoxicity. J Exp Med. 1997;186:1965. doi: 10.1084/jem.186.12.1965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Matsuda S, Moriguchi T, Koyasu S, Nishida E. T lymphocyte activation signals for interleukin-2 production involve activation of MKK6-p38 and MKK7-SAPK/JNK signaling pathways sensitive to cyclosporin A. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:12378. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.20.12378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Valiante NM, Phillips JH, Lanier LL, Parham P. Killer cell inhibitory receptor recognition of human leukocyte antigen (HLA) class I blocks formation of a pp. 36/PLC-γ signaling complex in human natural killer (NK) cells. J Exp Med. 1996;184:2243. doi: 10.1084/jem.184.6.2243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nakamura MC, Niemi EC, Fisher MJ, Shultz LD, Seaman WE, Ryan JC. Mouse Ly-49A interrupts early signaling events in natural killer cell cytotoxicity and functionally associates with the SHP-1 tyrosine phosphatase. J Exp Med. 1997;185:673. doi: 10.1084/jem.185.4.673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Burshtyn DN, Yang W, Yi T, Long EO. A novel phosphotyrosine motif with a critical amino acid at position -2 for the SH2 domain-mediated activation of the tyrosine phosphatase SHP-1. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:13066. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.20.13066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Le Drean E, Vély F, Olcese L, et al. Inhibition of antigen-induced T cell response and antibody-induced NK cell cytotoxicity by NKG2A. association of NKG2A with SHP-1 and SHP-2 protein-tyrosine phosphatases. Eur J Immunol. 1998;28:264. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-4141(199801)28:01<264::AID-IMMU264>3.0.CO;2-O. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fleming TJ, Donnadieu E, Song CH, et al. Negative regulation of FcεRI-mediated degranulation by CD81. J Exp Med. 1997;186:1307. doi: 10.1084/jem.186.8.1307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]