Abstract

The polymeric immunoglobulin receptor (pIgR) transports dimeric immunoglobulin A (dIgA) across the epithelial cell layers into the secretions of various mucosal and glandular surfaces of mammals. At these mucosal sites, such as the gastrointestinal tract, respiratory tract, urogenital tract and the mammary glands, dIgA protects the body against pathogens. The pIgR binds dIgA at the basolateral side and transports it via the complex mechanism of transcytosis to the apical side of the epithelial cells lining the mucosa. Here, the extracellular part of the receptor is cleaved to form the secretory component (SC), which remains associated to dIgA, thereby protecting it from degradation in the secretions. One pIgR molecule transports only one dIgA molecule (1 : 1 ratio) and the pIgR is not recycled after each round of transport. This implies that the amount of available receptor could be a rate-limiting factor determining both the rate and amount of IgA transported per cell and therefore determining the total IgA output into the lumen or, in case of the mammary gland, into the milk. In order to test this hypothesis, we set up an in vivo model system. We generated transgenic mice over-expressing the murine pIgR gene under lactogenic control, by using a milk gene promoter, rather than under immunological control. Mice over-expressing the pIgR protein, in mammary gland epithelial cells, from 60- up to 270-fold above normal pIgR protein levels showed total IgA levels in the milk to be 1·5–2-fold higher, respectively, compared with the IgA levels in the milk of non-transgenic mice. This indicates that the amount of pIgR produced is indeed a limiting factor in the transport of dIgA into the milk under normal non-inflammatory circumstances.

INTRODUCTION

In mammals, antibodies of the immunoglobulin A (IgA) class protect the mucosal and glandular surfaces of the body. These dimeric IgA (dIgA) antibodies are transcytosed across the epithelial cells lining the mucosa into the external secretions, such as milk and saliva, by the polymeric immunoglobulin receptor (pIgR).1,2 The pIgR is a transmembrane glycoprotein with five extracellular immunoglobulin-like domains, an intramembranous domain3,4 and a cytoplasmic C-terminal domain.5–7 After synthesis of the receptor protein on the endoplasmic reticulum, it is routed via the Golgi to the basolateral side of the epithelial cell. Here, the receptor can bind its ligand, dIgA. Next, the receptor, with or without dIgA, is endocytosed and transcytosed to the apical side of the epithelial cell. These processes are controlled by several sorting signals encoded within the C-terminal part of the pIgR protein.1,2 The pIgR is not recycled after transport of a dIgA molecule across the epithelial cell layer. Instead, the receptor is cleaved at the apical side of the epithelial cells by proteases, resulting in the release of the secretory component (SC) into the secretions, as a free protein or bound to dIgA. Thus, the receptor molecule has two functions: it performs the transcytosis of dIgA across the mucosal epithelial cell layer and it protects dIgA from degradation in the secretions, owing to the fact that SC remains associated with dIgA.

In this paper we examine the question of whether or not the pIgR is rate-limiting in the transport of dIgA across the epithelial cells into the external secretions, by using an in vivo system. By expressing the pIgR gene under the control of a strong, mammary-gland-specific milk gene promoter (αs1-casein), we created a model in which the pIgR is over-expressed controlled by lactogenic signals, rather than immunological signals, e.g. cytokines.8–11

Previously, we reported on the generation of the transgenic mice over-expressing the murine pIgR gene in the mammary glands during lactation.12 Here, we report on the localization of the pIgR protein in the mammary gland epithelial cells of normal and transgenic mice, the glycosylation of the over-expressed SC protein, and the effect of over-expression of the pIgR protein on dIgA transport in the mammary gland of the transgenic mice.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Milk collection from pIgR transgenic mice

Transgenic lines (mouse strain BCBA, C57BL/6 × CBA/J) were generated containing the complete murine pIgR gene under the control of the regulatory sequences of the bovine αs1-casein gene.12 Animal care and experimentation were in accordance with guidelines established at Leiden University. Milk samples were collected during early (days 3–5), mid- (days 6–14) and late (days 15–20) lactation. The females were separated from their pups for 2–3 hr before milking and injected subcutaneously with 1·0 unit of oxytocin-S (Intervet, Intervet International BV, Boxmeer, Holland), diluted 1 : 1 in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), 10 min before milking. The milk was collected with a vacuum pump device and stored at −20°.

SC and IgA detection in the milk by Western blotting

Milk samples were diluted in PBS and the samples were loaded under reducing conditions onto 7·5% sodium dodecyl sulphate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS–PAGE) gels. The milk of non-transgenic mice was used to measure the endogenous SC and IgA levels. Purified human secretory IgA (sIgA) from pooled human colostrum (Sigma–Aldrich Chemie BV, Zwyndrecht, the Netherlands) and mouse myeloma protein IgA (λ2) (ICN-Biomedicals BV, Veenendaal, the Netherlands) were used as controls. SDS–PAGE and Western blotting were performed according to standard protocols13,14 using the mini-PROTEAN II Cell system and polyvinyl difluoride (PVDF) membrane (Bio-Rad Laboratories BV, Veenendaal, the Netherlands). After blotting, the membranes were blocked for 1 hr in TBST [100 mm Tris–HCl pH 7·5, 150 mm NaCl, 0·2% (v/v) Tween-20 (Sigma)] containing 5% (w/v) non-fat milk powder (Protifar; Numico, Nutricia, the Netherlands). For detection of the SC protein a rabbit anti-human SC (Dako Ltd, ITK Diagnostics BV, Vithoorn, the Netherlands) was used and a rabbit anti-mouse IgA antibody (ICN) was used for detection of the IgA heavy chain. Both antibodies were diluted 1 : 1000 in TBST containing 1% Protifar. Peroxidase-conjugated, sheep anti-rabbit IgG (ICN) diluted 1 : 10000 in TBST containing 1% Protifar, was used as the second antibody in all cases. The first antibody was incubated overnight at room temperature and the second antibody for 1 hr at room temperature. Enhanced chemiluminescence detection15 was performed using sodium-luminol and p-Coumaric acid (Sigma).

Deglycosylation of SC protein

Milk samples (1 µl), containing approximately 100 µg of total protein as determined with the BCA Protein Assay Kit (Pierce, Omnilabo International BV, Breda, the Netherlands), were denatured by heating for 5 min at 100° after adding 25 µl 0·1 mβ-mercaptoethanol/0·5% SDS. Next, 50 µl of buffer containing 25 µl 0·5 m Tris–HCl (pH 8·0), 10 µl 10% non-ionic detergent (nonidet P-40, ICN) and 1 µl (1 U) N-glycosidase F (Boehringer Mannheim BV, Aememere, the Netherlands) was added to each denatured milk sample. The same reagents were added to the control, but without enzyme. The samples were incubated overnight at 35° for complete deglycosylation. Milk samples were heated for 5 min at 100° to inactivate N-glycosidase F. Milk proteins were separated on a 7·5% SDS–PAGE gel and SC was detected as described for Western blotting.

Immunohistochemical localization of pIgR protein

Mammary gland tissues from mice of all transgenic lines were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde and embedded in paraffin. Sections were cut (5 µm) and placed on 3′-aminopropyltriethoxysilane (APES)-treated glass slides. Tissues were deparaffinated and endogenous peroxidase activity was blocked by incubation for 20 min in methanol/0·3% (v/v) H2O2. Next, tissues were rehydrated in 100%, 70% and 50% ethanol, washed twice for 5 min with PBS. As a first antibody rabbit anti-human SC (1 : 200; Dako) in PBS/1% bovine serum albumin (BSA) was used and incubated overnight in a moist chamber. Slides were washed three times for 5 min with PBS and incubated for 30 min in a moist chamber with a biotinylated swine anti-rabbit antibody (1 : 400; Dako), as secondary antibody in PBS/1% BSA/10% normal mouse serum. Slides were washed three times for 5 min with PBS and incubated for 30 min in a moist chamber with a biotinylated horseradish peroxidase–streptavidin complex (Dako). 3,3′diamino-benzidene-4 HCL (DAB) (Sigma) was used as a peroxidase substrate. All sections were counterstained with haematoxylin.

Measuring IgA and IgG levels in the milk by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA)

Milk from five mice per transgenic line was collected during the mid-lactation period. Purified mouse IgA (λ2; ICN) and mouse IgG (Sigma) were used as standards for measuring IgA and IgG levels, respectively, in the milk samples. ELISA was performed according to standard protocols.16 Briefly, microtitre plates (Greiner Labortechnik BV, Alpen a/d Ryn, the Netherlands) were coated overnight at 4° with an affinity-purified goat anti-mouse IgA (α) antibody (0·5 µg/ml; ICN) or an affinity-purified goat anti-mouse IgG Fc antibody (2 µg/ml; ICN) in 0·1 m sodium carbonate buffer (pH 9·6) for the IgA or IgG ELISA, respectively. After four washes with PBS the wells were blocked with PBS/0·05% Tween-20/0·25% BSA (Sigma) (PBS–Tween–BSA) for 30 min at 37°. Milk samples diluted in PBS–Tween–BSA were added to the wells. Plates were incubated during each step for 1·5 hr at 37° and washed three times with PBS. The goat anti-mouse IgA (α) and the goat anti-mouse IgG Fc were also used conjugated with biotin–D-biotin-N-hydroxy-succinimidester (NHS) (Boehringer Mannheim), diluted 1 : 4000 in PBS–Tween–BSA. Horseradish peroxidase-labeled streptavidin (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech, Benelux, Rosendaal, the Netherlands), diluted 1 : 1000 in PBS–Tween–BSA, was added to the wells and incubated for 30 min at 37°. Detection of the peroxidase was performed with o-phenylenediamine dihydrochloride (OPD, 0·5 mg/ml; Sigma) as a substrate in phosphate–citrate buffer (pH 5·0). The colouring reaction was stopped after 15 min with 3 m HCl. Optical densities were measured at 490 nm using a Universal Microplate Reader ELx800 (Bio-Tek Instruments Inc., Beun de Ronde, Abcoude, the Netherlands). The analysis of variance (anova) test was used for statistical analysis.

RESULTS

SC and mRNA levels in pIgR transgenic mice

Four transgenic lines were generated containing the complete murine pIgR gene under the control of the bovine αs1–casein regulatory sequences.12 In all four lines, the transgene was exclusively expressed in the mammary gland. Transgene copy numbers ranged from 1 to > 10 copies/cell. The pIgR mRNA levels in the mammary gland tissue differed among the transgenic lines. Accordingly, varying amounts of SC protein were found in the milk of all lines analysed.12 Line 3644, containing the highest copy number (> 10) of the transgene, showed mRNA levels 30 times higher compared to the endogenous gene in non-transgenic mice. The SC levels in the milk of this line were elevated more than 250-fold resulting in levels of 2·7–2·8 mg/ml compared to 0·01 mg/ml in non-transgenic control mice. Line 3646 (2–5 copies/cell) expressed the pIgR gene at mRNA levels 30 times higher as compared to the endogenous gene in non-transgenic mice. The SC levels in the milk of these mice were 0·6–0·8 mg/ml. In line 3643 (2–5 copies/cell) mRNA levels were 10 times higher as compared to endogenous mRNA expression and SC levels reached 0·1–0·3 mg/ml. In line 3642 (1 copy/cell) the mRNA levels were low and the SC levels in the milk were equal to those found in the milk of non-transgenic control mice.12

Glycosylation of the extracellular part of murine pIgR protein

Previous studies have demonstrated that rat,17,18 human,4,19–22 rabbit23,24 and bovine25 pIgR molecules are N-glycosylated. Furthermore, an in vitro study with murine pIgR cDNA stably transfected into Chinese hamster ovary cells showed that the murine pIgR is also glycosylated.26 Potential sites for N-glycosylation with the consensus sequence Asn-X-Ser/Thr27 are present for mouse, rat, human, rabbit and bovine pIgR. For the murine pIgR eight such sites were found in the extracellular domains 1, 2, 4 and 5 of the receptor.28 In the cases of human4 and rabbit24 pIgR, all consensus sites are indeed glycosylated. The potential N-glycosylation sites vary among the species and some sites are more conserved than others.28

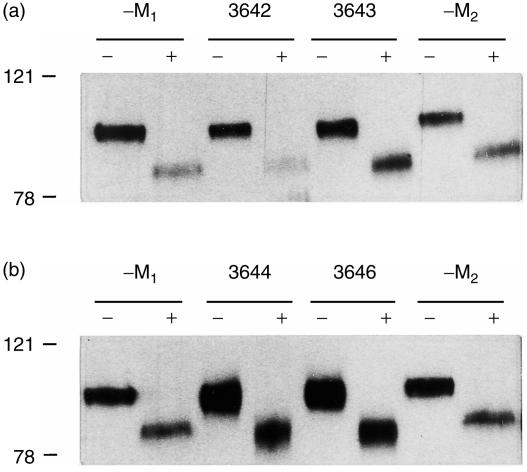

In order to rule out that overproduction of the receptor, especially in the lines with a 60–270-fold overproduction, might lead to incomplete glycosylation we examined the presence of N-linked oligosaccharide chains in the transgenic SC protein. Incomplete glycosylation could be due to insufficient glycosylation capacity of the epithelial cells in the cases of lines 3646 and 3644. This could have a negative impact on the function of the pIgR protein with respect to IgA transport. The presence of N-linked oligosaccharide chains in the transgenic SC protein (95 000–100 000 MW) was examined in these lines by deglycosylation followed by immunoblotting with a rabbit anti-human SC antibody. After deglycosylation, one protein band, approximately 15 000 less in molecular weight, around 80 000–85 000 MW was found in all transgenic lines as well as in the control mice (Fig. 1). In all cases only one SC band was found showing uniformity in the degree of N-glycosylation regardless of the pIgR expression level. This suggests that no aberrant glycosylation has taken place as a consequence of over-expressing the pIgR. When calculating the degree of N-linked glycosylation, using a MW of approximately 1500–3000 for an average N-linked carbohydrate chain, five to ten sugar chains must be present in the extracellular part of the endogenous and the transgenic pIgR. This estimation is in agreement with the eight potential glycosylation sites present in the murine SC protein.

Figure 1.

Glycosylation of the murine SC protein. Western blot analysis of milk samples from F2 females of four transgenic lines. Milk samples (1 µl) were treated with (+) or without (−) N-glycosidase F (1 U) and separated on a 7·5% SDS–PAGE gel. The SC protein has a MW of 95 000–100 000; the deglycosylated form has a MW of 80 000–85 000. Control milk samples: -M1, non-transgenic littermate (mouse 9726, 13 days lactation); -M2, non-transgenic littermate (mouse 9714, 11 days lactation). Milk samples: (a) line 3642 (mouse 8189, 12 days lactation); line 3643 (mouse 4779, 14 days lactation). (b) line 3644 (mouse 9507, 11 days lactation); line 3646 (mouse 4769, 13 days lactation). Molecular weight markers are indicated on the left (in kDa).

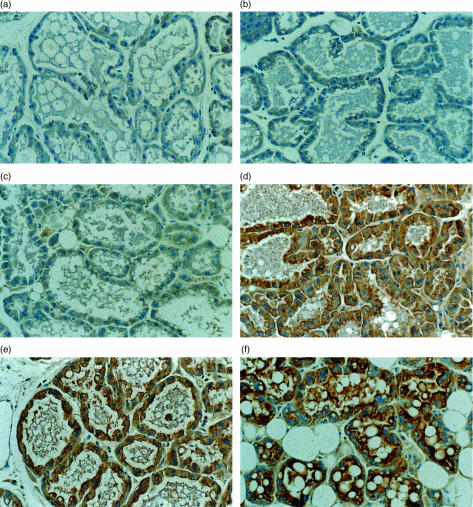

Immunohistochemical localization of the pIgR protein in mammary gland tissue sections

Localization of the pIgR protein in the epithelial cells was shown by immunohistochemical analysis of mammary tissue sections from all the transgenic lines (Fig. 2). The endogenous pIgR protein is visible in the alveolar and ductal epithelial cells of the mammary gland of non-transgenic mice as shown by the light brownish colour of these cells (Fig. 2b). The milk in the lumen of the alveoli is also stained, which shows that the SC protein is secreted into the milk. In all the transgenic lines the pIgR protein is found in the secretory epithelial cells of the alveoli and the ducts. The pIgR transgene is homogeneously expressed in the epithelial cells throughout the whole mammary gland tissue in all lines. Staining is strong at the basolateral and the apical sides of the epithelial cell (Fig. 2d–f). This indicates that transport of the receptor takes place to both the basolateral and the apical sides of the epithelial cell.

Figure 2.

Intracellular and extracellular localization of the pIgR protein in the mammary gland. Mammary gland tissue from mice of all transgenic lines was isolated at day 12 of lactation and tissue sections were incubated with a rabbit anti-human SC antibody. This antibody cross-reacts with the murine SC protein.12 (a) Mammary gland tissue of line 3646 incubated with PBS as a negative control. (b) A non-transgenic littermate to detect the endogenous pIgR expression in the epithelial cells of the mammary gland. The secretory epithelial cells of the alveoli show specific pIgR staining in the lines 3642 (c), 3643 (d), 3646 (e) and 3644 (f).

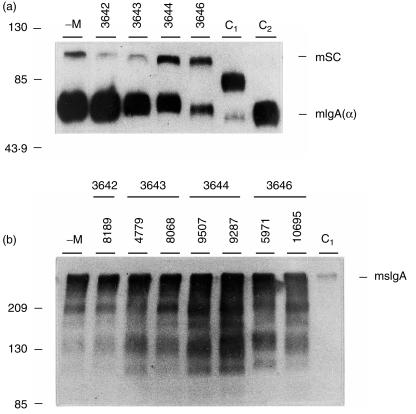

In the lines 3643, 3646 and 3644 (Fig. 2d–f, respectively) the epithelial cells are stained much more strongly at the apical side of the cells than at the basolateral side. This might indicate that the receptor release at the apical side is relatively slow, suggesting that proteolytic cleavage is limiting. The milk in the lumen of the alveoli is also strongly stained, which must be due to free SC or to SC bound to dIgA (Fig. 2f). Line 3644 also shows the highest SC protein levels in the milk as measured by Western blotting (Fig. 3). Lines 3643 and 3646 also have high pIgR levels (Fig. 2d,e, respectively), but much less than in line 3644. In the single copy line (3642) we found a low pIgR level in the epithelial cells given the light brown colouring of the cells (Fig. 2c). In all cases the milk in the lumen of the alveoli was also stained. The intensity of the pIgR protein staining was in proportion to the SC levels in the milk (see Fig. 3).

Figure 3.

IgA and SC in the milk of transgenic mice. Western blot analysis of milk samples, collected from F2 female mice of all transgenic lines. Samples were diluted in PBS as indicated below and 3 µl was fractionated on a 7·5% SDS–PAGE gel under reducing conditions (a) or non-reducing conditions (b). (a) The blot was incubated with a rabbit anti-human SC antibody and a rabbit anti-mouse IgA (α) antibody. Milk samples used: -M, non-transgenic littermate (13 days lactation); line 3642 (mouse 5967, 12 days lactation); line 3643 (mouse 8068, 13 days lactation); line 3644 (mouse 9507, 13 days lactation); line 3646 (mouse 5971, 14 days lactation). Dilutions used: line 3642, 1 : 10; line 3643, 1 : 50; line 3644, 1 : 500; line 3646, 1 : 200; non-transgenic littermate, 1 : 10. C1, purified human sIgA from colostrum (hsIgA, 20 ng SC). The 80 000 MW SC protein of the human sIgA molecule is visible and used as a reference. C2, mouse myeloma protein IgA (MOPC 315, 30 ng). The IgA murine heavy chain is shown as a band of 60 000 MW. The numbers on the left indicate the molecular weight of the protein standards (in kDa). mSC, murine secretory component (MW 95 000–100 000); mIgA (α), murine IgA heavy chain (MW 60 000). (b) The blot was incubated with a rabbit anti-mouse IgA (α) antibody. Milk samples used were diluted 1 : 10 in PBS. -M, non-transgenic littermate (14 days lactation); line 3642 (mouse 8189, 12 days lactation); line 3643 (mouse 4779, 14 days lactation; mouse 8068, 13 days lactation); line 3644 (mouse 9507, 13 days lactation; mouse 9287, 12 days lactation); line 3646 (mouse 5971, 14 days lactation; mouse 10695, 12 days lactation). C1, purified human sIgA from colostrum (415 000); msIgA, murine secretory IgA (MW 435 000).

Determination of IgA levels in pIgR transgenic mice

We obtained transgenic mice with a strongly increased level of pIgR in the mammary gland and demonstrated that transgene expression takes place exclusively within the epithelial cells, that the receptor is localized at the proper locations within the cells and that the receptor has a complete N-glycosylation profile. Now that the epithelial cells are equipped with an excess of functional receptor protein, we are in the position to ask the question whether or not such an increased amount of pIgR leads to elevated IgA levels in the milk.

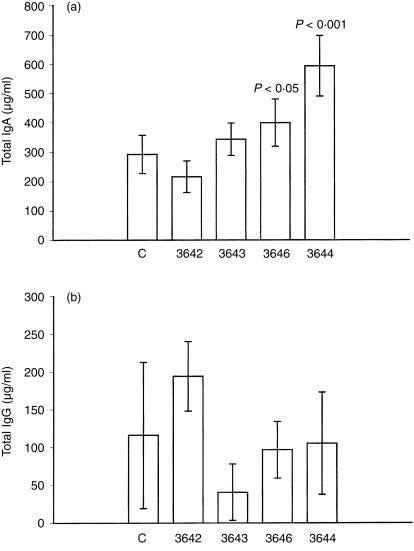

The IgA levels were determined on SDS–PAGE gels under reducing (Fig. 3a) and non-reducing (Fig. 3b) conditions with a rabbit anti-mouse IgA antibody. Under reducing conditions, IgA heavy chain was found as a 60 000 MW band in all the transgenic lines and in the control group (Fig. 3a). Under non-reducing conditions, IgA polymers corresponding to the MW of sIgA molecules (murine sIgA, 435 000 MW; human sIgA, 415 000 MW) were found. The bands with lower MW, are most likely caused by dissociation of a portion of sIgA during SDS–PAGE.29 In line 3644 clearly more sIgA is present (Fig. 3b). Total IgA levels were determined by ELISA in the milk of all four transgenic lines during mid-lactation (Fig. 4a). In the milk of the non-transgenic control group, the mean value of total IgA was 292 µg/ml. Transgenic line 3642 showed total IgA levels similar to the control group. In the milk from mice of line 3643, which have a 10-fold higher SC level in their milk than control mice, the total IgA level was increased slightly (Fig. 4a). Line 3646, having a 60-fold elevated SC protein level in the milk, showed 1·5 times elevated IgA levels. In line 3644, which has a 270-fold increased SC level, the concentration of total IgA was doubled (593 µg/ml) compared to the IgA concentration found in the milk of control mice. This shows that in the line with the highest pIgR expression, more IgA is transported across the epithelial cells into the milk.

Figure 4.

Total IgA and IgG levels in the milk of pIgR transgenic mice. IgA (a) and IgG (b) levels were determined in milk samples of five mice per line during mid-lactation (12–15 days) by sandwich ELISA. Mean values are shown and the standard deviation is indicated. The P-value obtained via statistical analysis of the data (anova) is indicated. C, control mice; transgenic line numbers: 3642, 3643, 3646 and 3644.

The pIgR transports IgA but not IgG. In order to demonstrate that the effect is specific for the pIgR and not a general immunological phenomenon, we also measured the IgG levels in the milk of these mice. The levels were not significantly different from the IgG levels found in the milk of non-transgenic mice (Fig. 4b). This proves that the over-expressed IgA receptor does not influence the IgG transport system into the milk. We conclude that elevated pIgR levels are enhancing IgA uptake and transport selectively.

DISCUSSION

The pIgR is a receptor molecule that is not recycled during execution of its main function, i.e. the transport of dIgA across the epithelial cells of the mammary gland and other mucosal tissues. Instead, the extracellular part of the receptor is cleaved and remains associated with dIgA, protecting it from degradation by proteases in the external secretions. This dual function makes the IgA receptor a unique molecule and it suggests that the amount of receptor made by these cells might be a rate-limiting factor controlling total IgA output by the mammary gland. If this were the case and more pIg receptor could be synthesized and directed to the basolateral site, more dIgA could be transcytosed through the epithelial layer. To shed light on this hypothesis, we generated transgenic mice over-expressing the murine pIgR gene in the mammary gland.12 In this paper we demonstrate a clear effect of over-expressing the pIgR gene on the IgA levels in the milk.

The immunohistochemical data obtained suggest that the cellular distribution and the trafficking of the receptor within the mammary gland epithelial cells of the transgenic mice are normal. In the lines 3643, 3646 and 3644 (Fig. 2d–f, respectively) we observed staining of the receptor throughout the whole secretory epithelial cell, with strong colouring at the basolateral side of the cell and very dense colouring at the apical side of the cell. This means that the transgenic receptor protein is routed to the basolateral side and to the apical side of the epithelial cell, either simultaneously or sequentially. According to the generally accepted transport mechanism of the endogenous receptor in epithelial tissue, we assume a normal transport, i.e. sequentially, of the pIgR from the basolateral side to the apical side within the epithelial cells. Abnormalities in pIgR routing or intracellular deposition would lead to a discrepancy between pIgR protein (Fig. 2) and pIgR mRNA12 levels in the tissue and SC levels in the milk (Fig. 3). So, the transcytotic route of the receptor seems not to be affected by its abundant supply in lines 3646 and 3644. This, combined with the glycosylation data of the over-expressed pIgR, suggests that the chosen method leads to overproduction of a functional IgA receptor.

In the milk of the lines 3646 and 3644, sIgA is present as high MW molecules (Fig. 3b) as is the case for the low expressing lines. This high MW band has a molecular weight of 435 000, which is the sum of two IgA dimers, J-chain and SC. This composition was confirmed by the observation that the 435 000 complex reacts with a rabbit anti-mouse IgA antibody (Fig. 3b), a rabbit anti-human SC antibody12 and a rabbit anti-human J-chain antibody (data not shown). However, in all cases there were several bands of lower MW, reacting with the rabbit anti-mouse IgA antibody. We are not certain about their identity, but it was shown by Parr et al. that during SDS–PAGE, dissociation may occur of a portion of the sIgA to produce several proteins containing α-chain determinants.29

The results obtained for the various lines as shown on the Western blot (Fig. 3b) and those obtained by ELISA are in agreement. Only the lines 3646 and 3644, with the highest expression of the transgene showed a significant difference in total IgA levels, which were up to twice as high as in control milk.

The difference in expression level of the receptor gene does not seem to correlate with the different levels of total IgA measured between line 3644 and 3646. The increase in IgA output is not in proportion to the magnitude of the increased pIgR synthesis. The level of total IgA in milk from line 3644 was only 1·5 times higher than the level in line 3646, while the SC levels in the milk were 4·5 times higher in the milk of line 3644 compared to line 3646. It seems that in line 3644 not all the pIgR produced is used for transport of dIgA. This could be explained either by an, in part, dysfunctional over-produced receptor molecule or by the fact that that part of the receptor molecules produced cannot reach the basolateral side of the epithelial cell. Examination of the molecular weight, overall N-glycosylation profile and intracellular localization of the over-expressed pIgR do not show obvious differences between endogenous and transgenic pIgR protein. The immunohistochemical data show that the location of the over-produced pIgR in line 3644 does not contradict the normal receptor routing pathway, i.e. first transport to the basolateral side of the epithelial cell to bind its ligand and thereafter to the apical side, releasing its ligand into the secretion. If we assume normal function of the receptor and as a consequence normal routing of the pIgR throughout the epithelial cell, shortage of IgA at the basolateral side of the epithelial cell must be the cause for the disproportional IgA output into the milk. To investigate this question, means must be found to increase the IgA levels in the tissue underlying the epithelial cell layer.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Dr M. Breuer and his staff (Leiden University Medical Center, the Netherlands) for generating and maintaining the transgenic lines.

Abbreviations

- IgA

immunoglobulin A

- dIgA

dimeric IgA

- sIgA

secretory IgA

- pIgR

polymeric immunoglobulin receptor

- SC

secretory component

- MW

molecular weight

REFERENCES

- 1.Kraehenbuhl J-P, Neutra MR. Molecular and cellular basis of immune protection of mucosal surfaces. Phys Rev. 1992;72:853–79. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1992.72.4.853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mostov KE. Transepithelial transport of immunoglobulins. Annu Rev Immunol. 1994;12:63–84. doi: 10.1146/annurev.iy.12.040194.000431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mostov KE, Friedlander M, Blobel G. The receptor for transepithelial transport of IgA and IgM contains multiple immunoglobulin-like domains. Nature. 1984;308:37–43. doi: 10.1038/308037a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Eiffert H, Quentin E, Wiederhold M, Hillemeir S, Decker J, Weber M, Hilschmann N. Determination of the molecular structure of the human free secretory component. Biol Chem Hoppe-Seyler. 1991;372:119–28. doi: 10.1515/bchm3.1991.372.1.119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Okamoto CT, Shia S-P, Bird C, Mostov KE, Roth MG. The cytoplasmic domain of the polymeric immunoglobulin receptor contains two internalization signals that are distinct from its basolateral sorting signal. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:9925–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hirt RP, Hughes GJ, Frutiger S, et al. Transcytosis of the polymeric Ig receptor requires phosphorylation of serine 664 in the absence but not the presence of dimeric IgA. Cell. 1993;74:245–55. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90416-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Reich V, Mostov K, Aroeti B. The basolateral sorting signal of the polymeric immunoglobulin receptor contains two functional domains. J Cell Sci. 1996;109:2133–9. doi: 10.1242/jcs.109.8.2133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kvale D, Lovhaug D, Sollid LM, Brandtzaeg P. Tumor necrosis factor-α up-regulates expression of secretory component, the epithelial receptor for polymeric immunoglobulins. J Immunol. 1988;140:3086–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Phillips JO, Everson MP, Moldoveanu Z, Lue C, Mestecky J. Synergistic effect of IL-4 and IFN-γ on the expression of polymeric Ig receptor (secretory component) and IgA binding by human epithelial cells. J Immunol. 1990;145:1740–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Piskurich JF, France JA, Tamer CM, Willmer CA, Kaetzel CS, Kaetzel DM. Interferon-γ induces polymeric immunoglobulin receptor mRNA in human intestinal epithelial cells by a protein synthesis dependent mechanism. Mol Immunol. 1993;30:413–21. doi: 10.1016/0161-5890(93)90071-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hayashi M, Takenouchi N, Asano M, Kato M, Tsurumachi T, Saito T, Moro I. The polymeric immunoglobulin receptor (secretory component) in a human intestinal epithelial cell line is up-regulated by interleukin-1. Immunol. 1997;92:220–5. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2567.1997.00341.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.de Groot N, van Kuik-Romeijn P, Verbeet MPh, Vollebregt E, Lee SH, de Boer HA. Over-expression of the murine polymeric immunoglobulin receptor gene in the mammary gland of transgenic mice. Transgenic Res. 1999;8:125–35. doi: 10.1023/a:1008981312682. Erratum Transgenic Res 1999; 8: 319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Laemmli UK. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature. 1970;227:680–5. doi: 10.1038/227680a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sambrook J, Fritsch EF, Maniatis T. Molecular Cloning A Laboratory Manual. Cold Spring Harbor, New York: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Thorpe GHG, Kricka LJ. Enhanced chemiluminescent reactions catalyzed by horseradish peroxidase. Meth Enzymol. 1986;133:331–53. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(86)33078-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Crowther JR. ELISA. Theory and Practice. In: Walker JM, editor. Methods in Molecular Biology. Vol. 42. Totowa, NJ: Humana Press Inc; 1995. pp. 1–223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sztul ES, Howell KE, Palade GE. Biogenesis of the polymeric IgA receptor in rat hepatocytes. I. Kinetic studies of its intracellular forms. J Cell Biol. 1985;100:1248–54. doi: 10.1083/jcb.100.4.1248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Musil LS, Baenziger JU. Intracellular transport and processing of secretory component in cultured rat hepatocytes. Gasteroenterology. 1987;93:1194–204. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(87)90244-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Purkayastha S, Rao CVN, Lamm ME. Structure of the carbohydrate chain of free secretory component from human milk. J Biol Chem. 1979;254:6583–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mizoguchi A, Mizuochi T, Kobata A. Structures of the carbohydrate moieties of secretory component purified from human milk. J Biol Chem. 1982;257:9612–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mostov KE, Blobel G. A transmembrane precursor of secretory component. The receptor for transcellular transport of polymeric immunoglobulins. J Biol Chem. 1982;257:11816–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Elkon KB. Charge heterogeneity of human secretory component: immunoglobulin and lectin binding studies. Immunology. 1984;53:131–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Solari R, Kraehenbuhl J-P. Biosynthesis of the IgA antibody receptor: a model for the transepithelial sorting of a membrane glycoprotein. Cell. 1984;36:61–71. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(84)90074-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Frutiger S, Hughes GJ, Hanly WC, Jaton J-C. Rabbit secretory components of different allotypes vary in their carbohydrate content and their sites of N-linked glycosylation. J Biol Chem. 1988;263:8120–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Labib RS, Calvanico NJ, Tomasi TB. Bovine secretory component. Isolation, molecular size and shape, composition, and NH2-terminal amino acid sequence. J Biol Chem. 1976;251:1969–74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Asano M, Saito M, Fujita H, Wada M, Kobayashi K, Vaerman J-P, Moro I. Molecular maturation and functional expression of mouse polymeric immunoglobulin receptor. J Immunol Methods. 1998;214:131–9. doi: 10.1016/s0022-1759(98)00052-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kornfeld R, Kornfeld S. Assembly of asparagine-linked oligo-saccharides. Annu Rev Biochem. 1985;54:631–64. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.54.070185.003215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Piskurich JF, Blanchard MH, Youngman KR, France JA, Kaetzel CS. Molecular cloning of the mouse polymeric Ig receptor. Functional regions of the molecule are conserved among five mammalian species. J Immunol. 1995;154:1735–47. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Parr EL, Bozzola JJ, Parr MB. Purification and measurement of secretory IgA in mouse milk. J Immunol Methods. 1995;180:147–57. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(94)00310-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]