Abstract

Cell transmission from mother to offspring was demonstrated using mice with green fluorescent protein (GFP) transgenic markers. GFP transgene heterozygous (+/−) females were mated with GFP (−/−) males, and GFP+ cells in the GFP (−/−) fetuses generated between them were analysed to assess maternal blood cell transmission to conceptuses in utero. The GFP+ maternal cells were observed throughout the body of the fetuses, as shown by fluorescence stereomicroscopy. Cell entrance into the fetal immune system was shown by histochemical and flow cytometric analyses of fetal organs such as thymus, spleen and liver. The GFP+ maternal cells persisted in the offspring until postpartum. Next, GFP (−/−) neonates fed by GFP+ foster mothers were examined to study the transfer of maternal milk leucocytes to offspring through breast-feeding. GFP+ leucocytes that had infiltrated through the wall of the digestive tract were mainly localized in the livers of neonates. Their accumulation in the livers reached a maximum on days 5 or 6, and these cells became undetectable, as assessed by either histochemistry or flow cytometry, after day 9 of starting foster nursing. Collectively, the present results demonstrate two independent pathways of maternal cell transmission to offspring: transplacental passage during pregnancy and breast-feeding after birth.

Introduction

In spite of the immunological importance of separation between the fetal and the maternal circulation during pregnancy, numerous studies have suggested the transplacental passage of circulating cells from mother to fetus1–11 and vice versa.12–15 The latter is especially of great importance with regard to the clinical requirements of screening fetuses for hereditary diseases. It has also been implicated that a few leucocytes in breast milk invade the tissues of suckling neonates.16–20 However, the frequency of such cell traffic determined in previous studies was not always consistent. One of the reasons for this discrepancy is presumably a result of the differences in analytical methods used. For example, some earlier results seemed to overestimate the cell traffic because of leakage of the cell markers, or as a result of the intrinsic expression of such markers by recipient cells. Recently, use of the polymerase chain reaction (PCR) has permitted a more sensitive and specific evaluation of maternal cells to be carried out.8,10,11,13–15 However, quantitative determination of fetomaternal cell traffic by PCR requires relatively complicated experiments. Before the biological significance of fetomaternal cell traffic can be assessed, a precise determination of cell traffic in normal animals is required.

Jellyfish green fluorescent protein (GFP) results in green biofluorescence,21 which has an emission spectrum maximized at 510 nm under excitation with blue light.22 Using GFP transgenic mice23 as a marker, maternal cell traffic to offspring was studied. GFP+ cells were found in the immune systems of GFP− fetuses grown in GFP (+/−) mothers during normal pregnancy, and they were also detected in GFP− neonates that had been fed by GFP+ foster mothers. The results of this work provide direct visible evidence for the presence of two independent pathways of maternal leucocyte transmission to offspring.

Materials and methods

Mice

C57BL/6 and Rag-2-deficient mice24 (C57BL/6 background) were purchased from Japan SLC Co. (Shizuoka, Japan) and the Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME). E-GFP-transgenic mice (chicken β-actin promoter) were established as previously described,23 except that the fertilized eggs used for microinjection were prepared from C57BL/6 mice. GFP transgene-negative [GFP (−/−)] fetuses (gestational day 12–18) were obtained by mating a GFP (+/−) female with a GFP (−/−) or a GFP (+/−) male and used for the examination of maternally derived GFP+ cells. In some experiments, GFP (−/−) fetuses were generated from a GFP (−/−) female bone marrow chimera that had been reconstituted with GFP (+/−) bone marrow cells and then mated with a GFP (−/−) male, or they were obtained from GFP (−/−) fertilized eggs that had been transferred into the uterus of GFP (+/+) pseudopregnant foster mothers, as described below.

Production of bone marrow chimeras

C57BL/6 females were irradiated (600 rads) and then injected with GFP (+/−) syngeneic bone marrow cells (107 mononuclear cells/mouse), as described by Onoé et al.25 Chimerism was tested by fluorescence-activated cell sorter (FACS) analysis of the thymocytes, and GFP fluorescence was expressed by 78% of the cells.

Mouse embryo transfer

GFP+ female mice were mated with a vasectomized male to produce pseudopregnant mothers. GFP− embryos of blastocyst stage were transferred into the uterine horns of 2·5-day postcoitus pseudopregnant recipients, as described by Hogan et al.26

Preparation of cell suspensions, and flow cytometric analysis

Cell suspensions were prepared from fetal or neonatal liver, spleen and thymus using 300-mesh stainless steel. Mononuclear cells were enriched from the cell suspension of neonatal liver, intestine and adult peripheral blood by density-gradient centrifugation using Lymphosepar II (d = 1·090; Immuno-Biology Laboratories, Gunma, Japan). Cells were washed in Hanks' balanced salt solution supplemented with 2·5% fetal calf serum (FCS) and 0·025% sodium azide, and were subjected to flow cytometric analysis. A ‘live-gate’ was set on the forward versus side scatter pattern for detection of viable leucocytes in the analysis, and up to 1 × 106 cells were counted. Anti-Gr-1 monoclonal antibody (mAb) (RB6-8C5, biotin conjugated), anti-Mac-1 mAb (M1/70, phycoerythrin [PE] conjugated), anti-Thy1.2 mAb (53-2.1, biotin conjugated) and anti-B220 mAb (RA3-6B2, PE conjugated) were purchased from Pharmingen (San Diego, CA) and were used for immunostaining of the milk leucocytes. Cells were treated with anti-Fc receptor antibody (2.4G2) before immunostaining to prevent non-specific binding of the antibodies. Flow cytometric analysis was conducted with a fluorescence-activated cell sorter (FACScan) using the cellquest program (Becton-Dickinson, Mansfield, MA).

Microscopy for detection of GFP+ cells

A fluorescence stereomicroscope (SZX-ZB12, equipped with a BA510-550 filter; Olympus, Tokyo, Japan) was used for detecting maternal GFP+ cells present in intact GFP− fetuses. Serial cryostat sections were cut to a thickness of 15 µm and were mounted without fixation. A fluorescence microscope equipped with a confocal laser-scanning imaging system (MRC-1024; Bio-Rad, Hemel Hempstead, Herts, UK) and a fluorescence microscope (Axiovert 135M; Zeiss, Jena, Germany) equipped with a spectrometer (SD200; Applied Spectral Imaging Ltd, Migdal Haemek, Israel) were used to detect GFP+ cells in the sections.

Preparation of milk leucocytes

Immediately following delivery, females were injected intraperitoneally with oxytocin (a peptide hormone inducing milk secretion, 0·5 U/animal; Sigma, St. Louis, MO). Milk was collected by suction and leucocytes were purified from it by treatment with hypotonic solution (0·17 m Tris (pH 7·6) : 0·83% NH4Cl, at a ratio of 1 : 9) followed by density-gradient separation using Lymphosepar II. The number of leucocytes in milk was counted after treatment of the cell suspension with Turk solution to exclude the residual oil-drops from the count.

Results

Maternal leucocyte transmission to fetuses during normal pregnancy

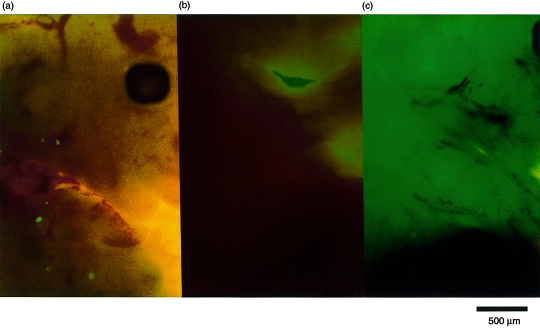

A GFP transgene heterozygous (+/−) female (C57BL/6 background) was mated with a normal male (C57BL/6) and the GFP+ cells derived from the maternal circulation were examined in the GFP (−/−) fetuses to determine cell transmission from mother to fetus. Figure 1 demonstrates the findings, as judged by fluorescence stereomicroscopy, of the GFP (−/−) fetus raised in a GFP (+/−) mother compared with the GFP (−/−) fetus raised in a GFP (−/−) mother (negative control). GFP+ maternal cells were distributed throughout the whole body of fetuses raised in the GFP (+/−) mother. On the contrary, no such cells were found in the fetuses raised in the normal mother. These results clearly indicate that maternal cell entrance into fetuses via the placenta occurs during normal pregnancy.

Figure 1.

Passage of cells from the maternal circulation into the fetus. Females either heterozygous for the green fluorescent protein (GFP) transgene [GFP (+/−)] or normal [GFP (−/−)] were mated with normal males. On day 14 of gestation, grossly negative pups were carefully examined for the presence of GFP+ cells using fluorescence stereomicroscopy. To ensure that the contour of the body was clearly visible, the fetuses were simultaneously illuminated with visible light. (a) Positive cells from the negative fetus of a GFP+ mother. (b) The normal fetus of a normal mother. The green colour in the background is caused by the visible light illumination; it is not fluorescence. (b) The dark area between the two green areas is the leg of the embryo. A GFP (+/−) fetus.

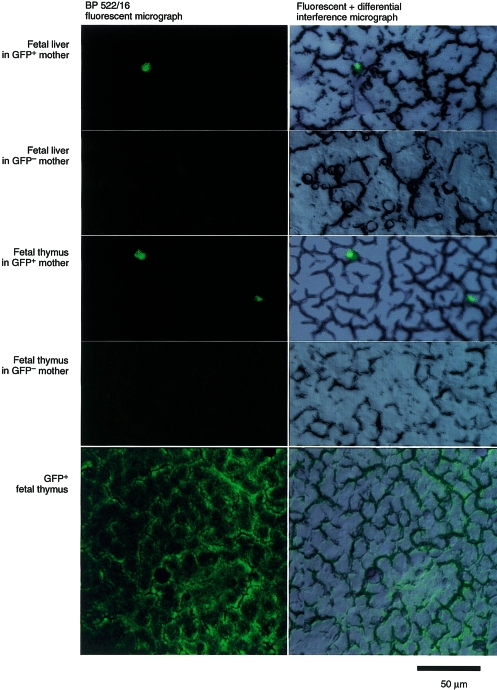

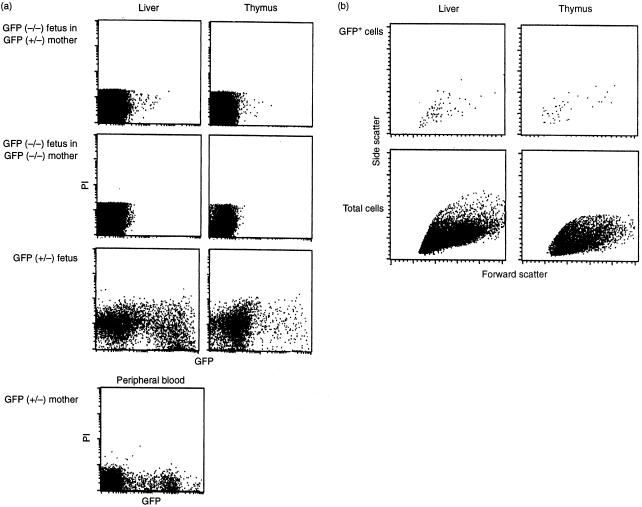

The maternal GFP+ cells were shown to enter the immune system of the fetus. GFP+ cells were observed by fluorescence microscopy in sections of the liver and the thymus from fetuses (gestational day 18) raised in GFP (+/−) mothers, as indicated in Fig. 2. The frequency of cell traffic from mother to fetus was determined by FACS analyses. Figure 3 shows an example of FACS analysis on a day-18 embryo. Of the immune organs examined, GFP+ cells were commonly found in the liver and thymus (0·015% of the liver and 0·059% of the thymus mononuclear cells in this case). The GFP+ cells were detected in nine livers of 35 fetuses examined, in the thymi of 11 of 30 fetuses and in the spleen of five of 30 fetuses (Table 1, experiments 1–9). The fetal thymus was suggested to be an organ to which maternal cells showed relatively frequent migration, taking into account its small capacity (the number of mononuclear cells recovered from thymus, liver and spleen on gestational day 18 was, on average, 1 × 106, 2 × 106 and 1 × 105, respectively) and the low flow rate of the circulation to it. The maternal GFP+ cells were detected in at least one of the immune organs in 16 of 35 fetuses (Table 1) examined by flow cytometry or stereomicroscopy. Here it should be noted that the expression of GFP fluorescence is dependent on the cell lineage and limited to a subpopulation of leucocytes in the GFP+ maternal circulation (Fig. 3). It is hard to imagine a mechanism by which a certain cell lineage other than leucocytes or erythrocytes is preferentially transmitted to the fetus at the fetomaternal border. Therefore, the total number of maternal cells, including erythrocytes, which were transmitted to the embryo, would be more than 100 times the numbers of GFP+ leucocytes observed in the present analyses.

Figure 2.

Maternal cell traffic to the immune system of fetuses, as examined using histochemistry. Frozen sections (15-µm thick) were prepared from the immune organs of the green fluorescent protein (GFP) (−/−) fetuses (gestational day 18) from either a GFP (+/−) or a GFP (−/−) mother, and GFP+ cells were analysed by using fluorescence microscopy. A GFP (+/+) thymus section is shown as a positive control.

Figure 3.

Determination of maternal cells in the immune system of fetuses by using flow cytometry. Single cell suspensions were prepared from the immune organs of green fluorescent protein (GFP)-negative fetuses (day 18 of gestation) from either a GFP (+/−) or a GFP (−/−) mother. They were analysed for GFP+ cells from the maternal circulation. Cells stained with propidium iodide (PI) were removed from analysis by the ‘live-gate’. (a) Detection of GFP+ cells on the FL-1 channel. GFP+ cells were found in the liver and thymus of a fetus raised by a GFP (+/−) mother (0·015% and 0·059% of the mononuclear cells), whereas no GFP+ cells were counted in the organs of fetuses from a GFP (−/−) mother. Analyses of the liver and thymus of a GFP (+/−) littermate, and peripheral blood of a GFP (+/−) female, are shown as positive controls for GFP+ cells. A substantial number of the non-fluorescent cells in GFP (+/−) fetal liver and maternal blood are contaminating erythrocytes. The presence of a large population of leucocytes with weak fluorescence is remarkable in fetal organs, especially in fetal thymus. The diminished fluorescence of the GFP+ maternal cells in GFP (−/−) fetuses may be caused by the circumstances specific to fetal organs. (b) Forward versus side scatter patterns of the cells prepared from the liver and thymus of the GFP (−/−) fetus of a GFP (+/−) mother shown in (a). The scatter pattern of the electronically gated GFP+ cells are compared with the pattern of the whole cells analysed.

Table 1.

Flow cytometric determination of green fluorescent protein (GFP)+ cells in GFP− fetuses raised by GFP+ mothers

| Number of GFP+ cells† | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Experiment* | Fetus | Thymus | Spleen | Liver |

| 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 6 |

| 2 | 16 | 0 | 0 | |

| 2 | 1 | 12 | 10 | 37 |

| 2 | 0 | 25 | 38 | |

| 3 | 6 | 0 | 0 | |

| 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| 6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| 7 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| 3 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 5 |

| 2 | 6 | 0 | 0 | |

| 3 | 2 | 0 | 0 | |

| 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| 6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| 4 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| 6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| 5 | 1 | 88 | 0 | 136 |

| 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | |

| 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| 6 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 8 |

| 2 | 18 | 4 | 0 | |

| 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| 7‡ | 1 | 0 | ||

| 2 | 17 | |||

| 3 | 0 | |||

| 4 | 0 | |||

| 5 | 153 | |||

| 8 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 2 | 16 | 6 | 0 | |

| 9 | 1 | 1 | 8 | 3 |

| 10 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 25 |

| 11 | 1 | 20 | 0 | 48 |

| 2 | 0 | 8 | 0 | |

| 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| 4 | 0 | 0 | 47 | |

| 12 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| 4 | 0 | 47 | 0 | |

| 5 | 0 | 6 | 0 | |

| 6 | 0 | 0 | 12 | |

| 7 | 0 | 0 | 13 | |

| 8 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

GFP− fetuses (gestational day 12–18) were obtained by mating a GFP (+/−) female with a GFP (−/−) male in experiments 1–7, and by mating a GFP (+/−) female with a GFP (+/−) male in experiments 8 and 9. In experiment 10, GFP (−/−) fetuses were generated from a GFP (−/−) female bone marrow chimera that had been reconstituted with GFP (+/−) bone marrow cells and then mated with a GFP (−/−) male. In experiments 11 and 12, GFP (−/−) fetuses were obtained from GFP (−/−) fertilized eggs that had been transferred into the uterus of GFP (+/+) pseudopregnant foster mothers.

Calibrated as numbers in the whole organ.

The thymuses and the spleens were not analysed.

Attempts were made, by using immunostaining analysis, to determine the cell lineage of the maternal cells found in the fetal organs, but these were hampered by non-specific binding of the antibodies. The forward- and side scatter pattern of the GFP+ cells in FACS analyses did not differ significantly from the pattern of whole cells, suggesting that the GFP+ cells comprised both lymphoid and myeloid cells (Fig. 3b).

It is possible that some of the GFP+ cells observed in the GFP (−/−) fetuses came from the GFP (+/−) litters. To assess this possibility, the following two experiments were carried out. First, the number of maternal GFP+ cells was determined in a fetus derived from a GFP (−/−) female that had been irradiated, reconstituted with GFP (+/−) bone marrow cells and then mated with a GFP (−/−) male (Table 1, exp. 10). Second, the number of maternal GFP+ cells was determined in fetuses derived from GFP (−/−) fertilized eggs that had been transferred into the uterus of GFP+ foster mothers (Table 1, exp. 11 and exp. 12). Essentially no decrease in the number of GFP+ cells in the GFP (−/−) fetuses was found in these experiments. In addition, no increase in cell transfer was detected in the GFP (−/−) fetuses that had been generated from mating between a GFP (+/−) female and a GFP (+/−) male (Table 1, exp. 8 and exp. 9). These findings strongly suggest that the main pathway of GFP+ cell entry into the GFP (−/−) fetuses is from the mother rather than from horizontal transfer between fetuses, although the latter pathway was not formally ruled out.

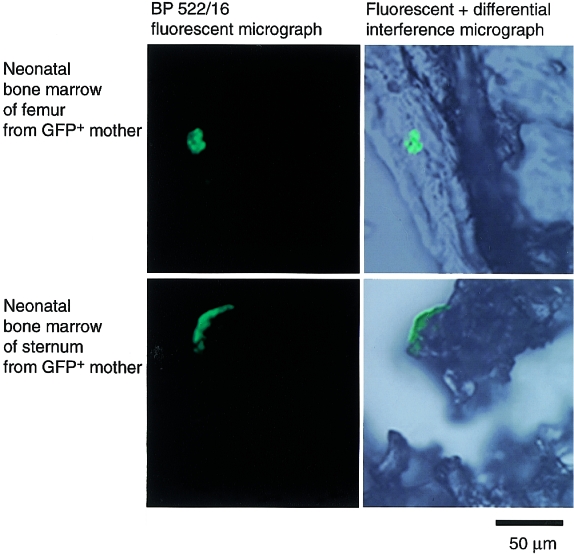

The maternal GFP+ in the bone marrow and spleen of offspring (two of five neonates tested), were detected by flow cytometry and/or histochemistry at least 2 days after birth. In some cases assemblies of GFP+ cells appeared to be present (Fig. 4). Thus, a substantial number of maternal cells passing through the placenta during pregnancy were suggested to survive in the neonates for several days postpartum.

Figure 4.

Persistence of maternal cells in pups after birth. Frozen sections (15-µm thick) are shown of a femur and a sternum prepared from a green fluorescent protein (GFP) (−/−) neonate (2 days old) of a GFP (+/−) mother. An assembly of GFP+ cells was detected in both sections, suggesting that maternally derived cells were proliferating in the bone marrow.

Migration of milk leucocytes into the circulation of lactating neonates

It has been reported that human colostrum contains more than 106 leucocytes/ml.27–30 In mouse colostrum, leucocytes with a cellular composition similar to that of humans were also found by FACS analysis, i.e. granulocytes (Gr-1+), 50–70%; monocytes (Mac-1+), 10–20%; T cells (Thy-1+), 3–10%; and B cells (B220+), < 2%. The concentration of leucocytes in mouse milk was variable and therefore presumably depends on the timing (the period since delivery) and the physical condition of the mother. However, usually 105 leucocytes/ml were found in the colostrum immediately following delivery.

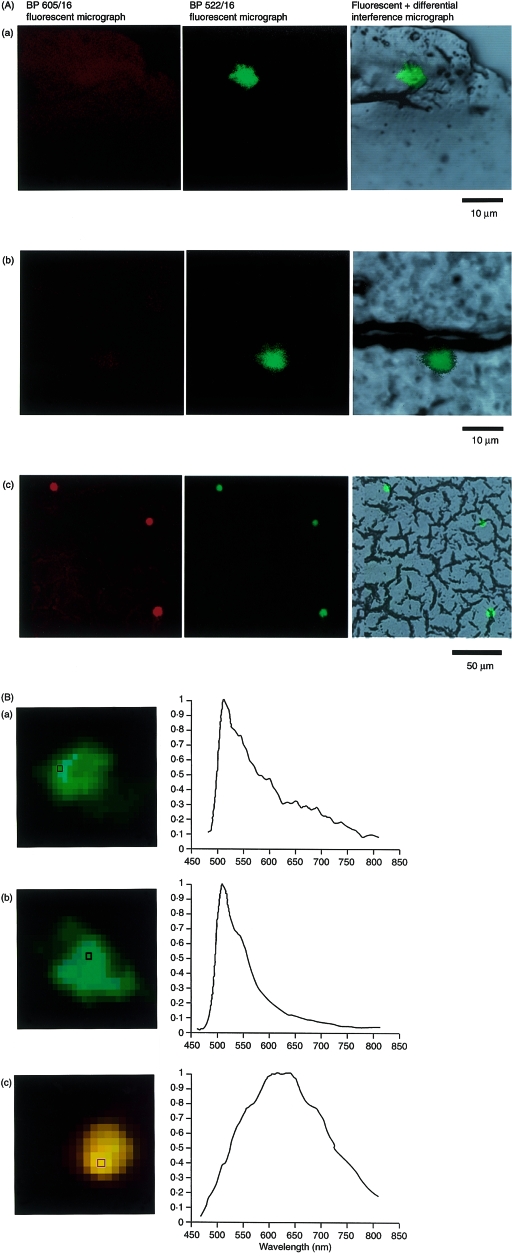

GFP− neonates immediately postpartum were foster nursed on a GFP transgenic mother that began nursing within a few days of delivery. The GFP+ cells transferred from maternal milk were analysed in neonates on different days following commencement of foster nursing. Figure 5 shows a histochemical analysis of the liver of a neonate fed by a GFP+ mother for 5 days. A GFP+ cell was found at a perisinusoidal capillary region of the neonatal liver; similarly, a GFP+ cell was observed in the same region of a neonate that had been injected with GFP+ mouse spleen cells. As these GFP+ cells had an emission spectrum with a sharp peak that maximized at 510 nm (Fig. 5b), they could be detected using a fluorescence microscope via an optical absorption filter for detecting fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC) fluorescence (BP 522/16), but not through a filter for detecting PE or rhodamine B fluorescence (BP 605/16). A reasonable number of autofluorescent cells were present in the neonatal liver. However, they were distinguishable from GFP+ cells because the autofluorescence had an emission spectrum with a broad peak that maximized at 617 nm (Fig. 5b), which could be detected by using a fluorescence microscope equipped with both of these absorption filters.

Figure 5.

Detection of green fluorescent protein (GFP)+ leucocytes (from milk) in the liver of GFP (−/−) neonates fed by a GFP+ foster mother. (A) Frozen sections (15-µm thick) prepared from the livers of the GFP− neonates fed for 5 days by a GFP+ (a) or a GFP− (c) foster mother were examined by fluorescence microscopy. As a positive control (b), a frozen section of the liver from a GFP− neonate that was subjected to intracardiac injection of splenocytes from an adult GFP+ mouse is shown. (B) Differentiation of the milk GFP+ cells found in the GFP (−/−) neonatal liver from endogenous autofluorescent cells by their emission spectrum. The emission from the squares in (a), (b) and (c) was measured. The emission spectrum of the GFP fluorescence maximized at 510 nm, whereas that of the autofluorescence peaked at 617 nm.

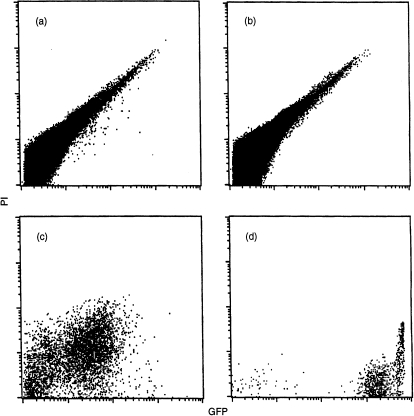

The milk leucocytes accepted by the neonates were localized in the livers. The GFP+ cells were found in frozen liver sections, but rarely in those of the spleen and thymus of the same neonates. This observation corresponded with the results of flow cytometric analysis. GFP+ cells were detected in a cell suspension from the liver of a neonate that was foster nursed by a GFP+ mother (0·002% of the neonatal liver mononuclear cells, in this case) (Fig. 6). They were detected in six of 13 neonates examined at 5 days of age when the accumulation of the maternal cells reached a maximum (see below). In contrast, only a few GFP+ cells were detected in the spleen and thymus of one of 11 5-day-old neonates examined (data not shown).

Figure 6.

Flow cytometric detection of green fluorescent protein (GFP)+ leucocytes (from milk) in the livers of GFP− neonates foster nursed by a GFP+ mother. GFP (−/−) neonates were foster nursed by either a GFP+ (a) or a GFP− (b) mother, as described in the legend to Fig. 5. The GFP+ cells in the livers of neonates were determined by fluorescence-activated cell sorter (FACS) analysis. Cells isolated from the intestine of a GFP− neonate fed by a GFP+ mother (c), and cells in GFP+ mouse milk (d) are shown for comparison. The GFP+ cells derived from milk were found off the diagonal, whereas the endogenous autofluorescent cells appeared on the diagonal on the FL-1 (GFP) versus FL-2 (propidium iodide [PI]) diagram. GFP+ cells were absent in the livers of neonates fed by a GFP− mother (b) but were detected in the livers of neonates fed by a GFP+ mother (a) (20 cells from > 106 mononuclear cells analysed [0·002%]). The intensity of GFP fluorescence in (a) is at the same level as in (c) but lower than in (d). This may be caused by the quenching of fluorescence during migration through the digestive tract.

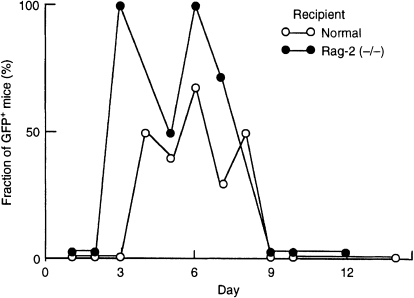

The number of milk leucocytes found in the livers of neonates varied among individuals (0–25 cells/106 cells). This variation may have been caused by changes in the concentration of leucocytes in milk or in the amount of milk consumed by each neonate. The accumulation of milk leucocytes in the livers of neonates was time-course dependent (Fig. 7, Table 2). The GFP+ cells were found in the livers of neonates after 3 days, and they increased in number until 6 days after starting foster-nursing by GFP+ mothers in both C57BL/6 and Rag-2 (−/−) recipients. They subsequently decreased and had disappeared by day 9, presumably because of the reduced number of leucocytes in milk, acidification of the stomach and secretion of digestive juices in the digestive tract.

Figure 7.

Age-dependent presence of milk leucocytes in the livers of neonates. The number of green fluorescent protein-positive (GFP+) milk leucocytes was determined by flow cytometry in the livers of GFP (−/−) neonates that had been fed by a GFP+ foster mother. The fraction of neonates with at least three GFP+ milk leucocytes in their liver are plotted against the number of days of breast-feeding. In total, 36 normal (C57BL/6) and 29 Rag-2 (−/−) neonates were analysed (one to nine neonates/day; see Table 2 for details).

Table 2.

Summary of the flow cytometric analysis for detecting milk green fluorescent protein (GFP)+ cells in the livers of neonates foster nursed by GFP+ mothers

| Days of breast-feeding | Strain of neonate* | No. of neonates analysed | No. of neonates accepting GFP+ cells† |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | C | 1 | 0 |

| R | 3 | 0 | |

| 2 | C | 3 | 0 |

| R | 2 | 0 | |

| R | 1 | 0 | |

| 3 | C | 2 | 0 |

| R | 2 | 2 | |

| 4 | C | 4 | 2 |

| 5 | C | 5 | 2 |

| R | 8 | 4 | |

| 6 | C | 3 | 2 |

| R | 1 | 1 | |

| 7 | C | 9 | 3 |

| R | 7 | 5 | |

| 8 | C | 2 | 1 |

| 9 | C | 1 | 0 |

| R | 1 | 0 | |

| 10 | C | 5 | 0 |

| R | 1 | 0 | |

| 12 | R | 2 | 0 |

| 14 | C | 1 | 0 |

| R | 1 | 0 |

C, C57BL/6; R, Rag-2 (−/−).

Neonates in which more than three GFP+ cells were detected were judged to be positive. The average number of GFP+ cells found in the liver of 3–8-day-old recipients was five, four, 13, 10, nine and four, respectively.

Collectively, our present results provide definitive evidence for the presence of two independent pathways of maternal leucocyte transmission to offspring: through the placenta during pregnancy and by breast milk feeding after birth.

Discussion

Two independent routes of maternal cell traffic to offspring during normal reproduction were indicated in this study using GFP transgenic mice.

Transmission of maternal leucocytes to fetuses during pregnancy was not universal, being observed in ≈ 50% of the fetuses. These findings bring into question the notion that maternal cells gain access to the fetal circulation in an active manner at the fetomaternal border of the placenta. Nevertheless, this does not necessarily mean that the maternal cells transmitted to fetuses have no function from an immunological point of view. Unlike milk leucocytes, the maternal cells that pass through the placenta and become incorporated into the fetal circulation may easily reach the immune system of the fetus. They were found relatively frequently in the fetal thymus and therefore it is possible that some hematopoietic progenitors (for example progenitor T cells) from the maternal circulation entered the fetal thymus by specific affinity and remained there. The same possibility has been suggested by Piotrowski & Croy for the immune-incompetent fetal recipients.9 These authors reported that the passage of maternal cells was found only in the thymus of scid/scid fetal recipients on gestational days 9–12. It is not clear whether the fetal thymus of normal recipients is also the site where the maternal cells initially target; the GFP+ cells from the maternal circulation were distributed throughout the whole body of fetuses of gestational age 12–14 days (Fig. 1; L. Zhou & H. Shimamura, unpublished). However it is true that the fetal thymus of immune-competent as well as immune-incompetent recipients is one of the sites where maternal cells were frequently found, as shown in this study. The maternal cells found in the fetal thymus might remain only until birth, after which they might leave, as demonstrated by the fact that maternal cells were rarely found in the thymus postpartum. Instead, they were detectable in the spleen, as previously reported,8 as well as in the bone marrow (Fig. 4).

This study gives the first known quantitative results showing milk leucocyte entrance into the circulation of neonates. Although the number of milk leucocytes incorporated by the neonates was fewer than the maximum number of maternal leucocytes found in the fetus during pregnancy, milk leucocyte infiltration through the wall of the digestive tract was invariably observed on day 5 to 6 postpartum (Fig. 7). Milk leucocytes were mainly found in the livers of neonates. Their site-specific distribution may be caused by the following:

The milk leucocytes that have overcome the barrier of the digestive tract enter the portal veins that lead to the liver.

Leucocytes of a particular lineage with affinity to the liver are present in milk.

Following development of the immune system, there remains less room for the milk leucocytes to stay in the immune system of neonates compared with the immature immune system of fetuses.

In fact, the immunoincompetent recipients, Rag-2 (−/−) neonates, seemed to accept slightly more milk leucocytes than the immunocompetent recipients (C57BL/6 neonates) [GFP+ cells were found in 67% of the Rag-2 (−/−) neonates 3–8 days postpartum, whereas milk leucocytes were detected in 40% of the C57BL/6 neonates of the same age; Fig. 7 and Table 2].

Weiler et al. reported that milk leucocytes infiltrate neonates at a high frequency (0·1% of the total cells fed to neonates) just 1 hr after oral administration of pooled milk lymphoid cells.19 On the contrary, in this study milk leucocytes were initially detected in the livers of foster-nursed neonates 3 days postpartum (Fig. 7). These findings suggest that most of the milk leucocytes that have transiently entered neonates are immediately catabolized and only a small number of the milk leucocytes remain in the liver for a substantial period of time.

In this study, the detection (by flow cytometry and histochemistry) of maternal cell traffic in the immune system of offspring through these two pathways became difficult after 9 days postpartum. The long-term persistence of maternal cells in neonates should be examined by more sensitive methods, for example by PCR, to assess the biological functions of these cells. Maternal cells transmitted to offspring, however, will eventually become targets of natural killer (NK) cells following their development by the mechanism of hybrid resistance31 in the natural progression of pregnancy and nursing.

The significance of maternal cell transmission to offspring by these two routes (transplacental passage during pregnancy and breast-feeding after birth) is not yet clearly understood, although this phenomenon could illustrate one of the mechanisms responsible for various illnesses in newborns, for example, graft versus host disease [reviewed in ref. 32] and the subsequent induction of autoimmunity,10,11 or vertical transmission of pathogens such as human immunodeficiency virus (HIV).33 One possible physiological role is to influence the repertoire formation of lymphocytes in the developing thymus. Antigen-presenting cells such as dendritic cells or macrophages derived from the maternal circulation, or those from fetal hematopoietic organs that have been exposed to maternal cells, have the opportunity to present antigens specific to mature animals, and such antigen-presenting cells could have a role in the negative selection of developing fetal T cells. These processes could enable the fetuses to develop a tolerance to self-antigens that will be expressed after maturation. Another possibility is their role in the protection of neonates from attack by foreign antigens. It is well established that immunoglobulins and some other components included in the pregnant mother's circulation or in the colostrum are incorporated into the developing offspring and function as protective factors.29,30,34,35 Similarly, some effector cells that are functional without cognate help may serve to protect newborns from pathogens until their immune systems become fully functional.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge Drs S.-Y. Song, S. C. Fujita, H. Takayama, I. Nihonmatsu and T. Saitoh (Mitsubishi Kasei Institute of Life Sciences) for their advice on histochemistry and microscopy. We thank Olympus Co. for giving us the opportunity to use a fluorescence stereomicroscope. We thank Ms Y. Murakami for her secretarial assistance. The authors express their sincere thanks to Prof. N. Shinohara (Kitasato University) for his valuable advice.

Abbreviations

- GFP

green fluorescent protein, PI, propidium iodide

References

- 1.Benirschke K. Spontaneous chimerism in mammals: a critical review. Curr Top Pathol. 1970;51:570–581. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Desai RG, Creger WP. Maternofetal passage of leukocytes and platelets in man. Blood. 1963;21:665–73. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zarou D, Lichtman HC, Hellman LM. The transmission of chromium-51 tagged maternal erythrocytes from mother to fetus. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1964;88:565–71. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(64)90881-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hörmann G, Lemtis H. Zur frage der diaplazentaren Metastasierung maligner Blastome der Mutter. Z Geburtshilfe Gynäkol. 1965;164:1–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.El-Alfi OS, Hathout H. Maternofetal transfusion: immunologic and cytogenetic evidence. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1969;103:599–600. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(15)31866-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Collins GD, Chrest EJ, Alder WH. Maternal cell traffic in allogeneic embryos. J Reprod Immunol. 1980;2:163–72. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hunziker RD, Gambel P, Wegmann TG. Placenta as a selective barrier to cellular traffic. J Immunol. 1984;133:667–71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shimamura M, Ohta S, Suzuki R, Yamazaki K. Transmission of maternal blood cells to the fetus during pregnancy: Detection in mouse neonatal spleen by immunofluorescence flow cytometry and polymerase chain reaction. Blood. 1994;83:926–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Piotrowski P, Croy BA. Maternal cells are widely distributed in murine fetuses in utero. Biol Reprod. 1996;54:1103–10. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod54.5.1103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nelson JL. Autoimmune disease and the long-term persistence of fetal and maternal microchimerism. Lupus. 1999;8:493–6. doi: 10.1191/096120399678840783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Maloney S, Smith A, Furst DE, Myerson D, Rupert K, Evans PC, Nelson JL. Microchimerism of maternal origin persists into adult life. J Clin Invest. 1999;104:41–7. doi: 10.1172/JCI6611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Benirschke K, Driscoll SG. The Pathology of the Human Placenta. Berlin, Germany: Springer; 1967. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gaenshirt-Ahlert D, Pohlschmidt M, Gal A, Miny P, Horst J, Holzgreve W. Ratio of fetal to maternal DNA is less than 1 in 5000 at different gestational ages in maternal blood. Clin Genet. 1990;38:3843. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0004.1990.tb03545.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wachtel S, Elias S, Price J, et al. Fetal cells in the maternal circulation: isolation by multiparameter flow cytometry and confirmation by polymerase chain reaction. Hum Reprod. 1991;6:1466–9. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.humrep.a137290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bianchi DW. Fetomaternal cell trafficking: a new cause of disease? Am J Med Genet. 2000;91:22–8. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-8628(20000306)91:1<22::aid-ajmg4>3.0.co;2-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kmetz M, Dunne HW, Schultz RD. Leukocytes as carriers in the transmission of bovine leukemia: invasion of the digestive tract of the newborn by ingested cultured leukocytes. Am J Vet Res. 1970;31:637–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Silvers WK, Poole TW. The influence of foster nursing on the survival and immunologic competence of mice and rats. J Immunol. 1975;115:1117–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Head JR, Beer AE, Billingham RE. Significance of the cellular component of the maternal immunologic endowment in milk. Transplant Proc. 1977;9:1465–71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Weiler IJ, Hickler W, Sprenger R. Demonstration that milk cells invade the suckling neonatal mouse. Am J Reprod Immunol. 1983;4:95–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0897.1983.tb00261.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jain L, Vidyasagar D, Xanthou M, Ghai V, Shimada S, Blend M. In vivo distribution of human leukocytes after ingestion by newborn baboons. Arch Dis Child. 1989;64:930–3. doi: 10.1136/adc.64.7_spec_no.930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ward WW. Energy transfer processes in bioluminescence. Photochem Photobiol Rev. 1979;4:1–57. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chalfie M, Tu Y, Euskirchen G, Ward WW, Pracher DC. Green fluorescent protein as a marker for gene expression. Science. 1994;263:802–5. doi: 10.1126/science.8303295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Okabe M, Ikawa M, Kominami K, Nakanishi T, Nishikawa Y. ‘Green mice’ as a source of K ubiquitous green cells. FEBS Lett. 1997;407:313–9. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(97)00313-x. 10.1016/s0014-5793(97)00313-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shinkai Y, Rathbun G, Lam K-P, et al. Rag-2-deficient mice lack mature lymphocytes owing to their inability to initiate V–(D)–J rearrangement. Cell. 1992;68:855–67. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90029-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Onoé K, Fernandes G, Good RA. Humoral and cell-mediated immune responses in fully allogeneic bone marrow chimera in mice. J Exp Med. 1980;151:115–32. doi: 10.1084/jem.151.1.115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hogan B, Costantini F, Lacy E. Manipulating the Mouse Embryo: a Laboratory Manual. Cold Spring Harbor, NY: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bertotto A, Gerli R, Fabiett G, Crupi S, Arcangeli C, Scalise F, Vaccaro R. Human breast milk T lymphocytes display the phenotype and functional characteristics of memory T cells. Eur J Immunol. 1990;20:1877–80. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830200838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wirt DP, Adkins LT, Palkowetz KH, Schmalstieg FC, Goldman AS. Activated and memory T lymphocytes in human milk. Cytometry. 1992;14:282–90. doi: 10.1002/cyto.990130310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Goldman AS. The immune system of human milk: antimicrobial, antiinflamatory and immunomodulating properties. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1993;12:664–71. doi: 10.1097/00006454-199308000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Newman J. How breast milk protects newborns. Sci Am. 1995;273:76–9. doi: 10.1038/scientificamerican1295-76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yu YYL, Kumar V, Bennett M. Murine natural killer cells and marrow graft rejection. Annu Rev Immunol. 1992;10:189–213. doi: 10.1146/annurev.iy.10.040192.001201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Papadogiannakis N. Traffic of leukocytes through the maternofetal placental interface and its possible consequences. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 1997;222:141–57. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-60614-4_7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sprecher S, Soumenkoff G, Puissant F, Degueldre M. Vertical transmission of HIV in 15-week fetus. Lancet. 1986;2:288–9. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(86)92110-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hanson LA. Breastfeeding stimulates the infant immune system. Sci Med. 1997;4:12–21. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Brambell FWR. Transmission of immunity from mother to young and the catabolism of immunoglobulins. Lancet. 1966;2:1087–97. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(66)92190-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]