Abstract

BALB/c mice resolve Leishmania donovani infection in the liver over an 8–12-week period. However, after an initial phase of 2–4 weeks where increases in parasite load are not readily detectable, parasite numbers in the spleen begin to increase reaching maximum levels at 16 weeks post-infection. Thereafter, parasite replication in the spleen is controlled and BALB/c mice maintain this residual parasite load in the spleen for many months, without further increase. We evaluated functions of CD11C+ splenic dendritic cells throughout the course of L. donovani infection in the spleen of BALB/c mice. Unlike the dendritic cell (DC)-specific antigen DEC-205, CD11C was not up-regulated on macrophages during visceral leishmaniasis. No appreciable impairment of splenic DC functions was observed when this antigen-presenting cell subset was purified from 30-day post-infected mice. Significant impairment in inducing allogeneic mixed lymphocyte reaction (MLR) and presenting L. donovani antigens or keyhole limpet haemocyanin (KLH) to specific T cells was observed with CD11C+ splenic DC purified from 60-day post-infected mice. Functional impairment of splenic DC at 60 days post-infection correlated with their reduced surface expression of major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class II molecules, impairment of interleukin-12 (IL-12) production and to their ability to suppress interferon-γ (IFN-γ) production by Leishmania antigen-primed T cells. Of interest, the impairment of splenic DC in presenting Leishmania antigens or KLH to specific T cells was corrected at 120 days post-infection, and correlated with their up-regulation of MHC class II expression, IL-12 production, induction of IFN-γ by Leishmania antigen-primed T cells and the onset of control over splenic parasite replication in vivo. These results indicate that functional integrity of DC may be important in controlling L. donovani infection.

Introduction

Visceral leishmaniasis is caused by the kinetoplastid protozoon Leishmania donovani, an intracellular parasite which survives and multiplies within macrophages (Mφ). Diseases resulting from infection with Leishmania may be resolved according to the type of T helper (Th) cell response mounted,1 and the protection requires Leishmania-specific CD4+ Th1 cells.2 Visceral leishmaniasis is associated with immunological dysfunctions of T cells,3,4 natural killer cells5,6 and Mφ.7–9 Dendiritic cells (DC), first described by Steinman and Cohn,10 represent a minor population of leucocytes, but play an important role in the initiation of immune responses. They are the most efficient antigen-presenting cells (APC) and have the ability to act as APC for induction of T-cell responses to a variety of antigens both in vitro and in vivo.11 Recently, DC were shown to drive Th1 development by production of interleukin-12 (IL-12).12 Epidermal Langerhans cells, which are members of the dendritic cell family, were able to phagocytose L. major, the causative agent of cutaneous leishmaniasis, and served as host cells for the organisms in the skin of experimentally infected mice.13L. major-infected DC in lymph nodes of immune mice presented endogenous parasite antigens to T cells and sustained stimulation of a population of parasite-specific T cells, protecting the mice from reinfection.14

Reports on the role of DC in visceral leishmaniasis are infrequent. A recent report demonstrated that L. donovani infection in the spleen of BALB/c mice was associated with loss of both follicular dendritic cells and germinal centre B cells.15 Dendritic cells, but not macrophages, were shown to produce IL-12 immediately following L. donovani infection in BALB/c mice.16 In the present work, our studies have focused on the evaluation of this important APC in murine visceral leishmaniasis throughout the course of infection.

Materials and methods

Media and antibodies

RPMI-1640 medium (Gibco Laboratories, Grand Island, NY) supplemented with glutamine, 125 IU/ml penicillin, 6·25 µg/ml gentamicin, 50 µ m 2-mercaptoethanol (2-ME; Sigma, St Louis, MO) and 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (FBS; Gibco) was used in in vitro experiments unless otherwise stated. Goat anti-mouse immunoglobulin M (IgM) (µ chain specific), phycoerythrin (PE)-conjugated goat anti-mouse immunoglobulin and brefeldin A were purchased from Sigma. Mabs, Jij10 (anti-Thy1.2),17 MKD6 (anti-mouse major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class II [anti I-Ad])18 were produced from cells purchased from American Type Culture Collection, Manassas, VA. Fluoroscein isothiocyanate (FITC)-conjugated anti-mouse CD11C, PE-conjugated anti-mouse CD11b and PE-conjugated anti-mouse IL-12p40 were obtained from Pharmingen, San Diego, CA. Permeabilizing solution for fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS™) was purchased from Becton Dickinson, San Jose, CA.

Purification of CD11C+splenic dendritic cells from BALB/c mice by cell sorting

DC were isolated from mouse spleen after modification of the methods described by Steinman et al.10 and Saikh et al.,19 followed by sorting of CD11C+ cells. Briefly, mouse spleens were injected with 0·5 ml collagenase (400 U/ml). The spleen cell suspension (10 × 106/ml) was then allowed to adhere in tissue culture dishes (100 × 15 cm, Nunclon, Delta, Denmark) at 37° for 90 min. Non-adherent cells were removed, the adherent cells were washed (× 2) with warm RPMI-1640 by gentle swirling, then incubated overnight at 37°. After overnight culture, transiently adherent cells were dislodged and appeared as non-adherent cells. These non-adherent cells were further enriched for DC by negative selection before sorting. Non-adherent cells were depleted of residual B cells and T cells by antibody plus complement-mediated lysis.20 Antibodies were added to 5 × 106 non-adherent cells in a total volume of 1 ml of RPMI-1640 containing 10% FBS. The following antibodies were used: anti-µ (3 µg/ml, goat anti-mouse), Thy1.2/culture supernatant. After 1 hr incubation at room temperature, cells were centrifuged (100 g for 10 min), resuspended in 1 ml of non-toxic baby rabbit complement (diluted 1:2), and incubated for 1 hr at room temperature. The cells were centrifuged, the supernatant was removed and treatment with complement was repeated. Partially enriched DC preparations contained 10–50% CD11C+ cells and were further purified by cell sorting. Cells were stained with FITC-conjugated anti-CD11C. CD11C+ cells were gated and sorted using FACS Calibur (Becton Dickinson). Sorted cells containing > 90% CD11C+ were used in all experiments unless otherwise stated.

Parasite and parasite antigens

Leishmania donovani virulent strain AG83 was originally obtained from an Indian Kala-azar patient21 and maintained in golden hamsters. Promastigotes were obtained by transforming amastigotes from the spleen of infected animals and maintained in vitro in Media-199 supplemented with 8% FBS. Amastigotes were purified from the spleen of infected hamsters by density gradient centrifugation. For the preparation of soluble parasite antigens, stationary phase promastigotes were washed and suspended in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) at a concentration of 2 × 108 organisms/ml. Parasite suspensions were then subjected to three cycles of freezing and thawing, centrifuged at 15 000 g for 30 min at 4°, supernatants were collected and stored at –70° until used.

Infection of BALB/c mice with L. donovani

Genetically susceptible mice BALB/c (5–6-weeks old) were injected i.v. with freshly purified 1 × 107 amastigotes of L. donovani. At various intervals, Giemsa-stained imprints of the cut surface of the spleens of three to five mice were examined for parasite burden which were quantitated using the formula:

|

Generation of antigen-primed T cells

Mice were immunized s.c. at the base of the tail and into hind foot pads with soluble promastigote antigens (equivalent to 70 × 106 parasites) or with keyhole limpet haemocyanin (KLH; 100 µg) emulsified in Freund’s complete adjuvant. After 8 days, inguinal and popliteal lymph nodes were collected and used as responder cells in antigen presentation assays.

Allogeneic mixed leucocyte reactions (MLR)

Primary allogeneic MLR were set up with non-adherent splenocytes (2 × 105) of normal C57BL/6 mice as responder cells and graded numbers of DC of BALB/c mice (purified at different stages of post-infection with L. donovani) as stimulator cells in 96 well flat-bottomed plates in a total volume of 200 µl. After 96 hr of incubation at 37°, individual wells were pulsed with 1 µCi/well [3H]thymidine for the last 16 hr of culture. Cells were harvested on fibreglass filters, and the [3H]thymidine incorporation was measured in a liquid scintillation counter.

Antigen-presenting assay

Inguinal and popliteal lymph node cells (2 × 105 per well) from promastigote antigen- or KLH-primed BALB/c mice were cultured with antigen-presenting cells (2·5 × 104) in the absence and presence of optimal concentrations of exogenous antigens (soluble promastigote antigens, 25 µg/ml; KLH, 10 µg/ml), as determined in preliminary studies. As the source of APC, CD11C+ splenic DC purified from spleens of BALB/c mice (uninfected and at different stages of post-infection) were used. Culture was performed in 96-well flat-blottomed microtitre plates in a final volume of 200 µl for 96 hr; [3H]thymidine, 1 µCi/well was added during the last 16 hr of incubation. In parallel experiments, cell-free supernatants were harvested after 24 hr and 72 hr of culture for quantitation of IL-12 and interferon-γ (IFN-γ), respectively.

Cytokine assays in supernatants

The IL-12p70 and IFN-γ levels were measured in the culture supernatants of antigen presentation assay by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). The ELISA kits used to measure mouse IL-12p70 and IFN-γ were obtained from Genzyme (Cambridge, MA). The lower limit of detection for IL-12p70 and IFN-γ was 5 pg/ml each.

Flow cytometry

As DC-specific antigen DEC-205 has previously been shown to be up-regulated on macrophages during chronic stimulation,23 expression of CD11C was evaluated on macrophages purified from the spleens of L. donovani-infected mice by flow cytometry. Macrophages were purified by plastic adherence and stained for the expression of CD11C and CD11b. Expression of MHC class II molecules on DC purified from uninfected and L. donovani-infected BALB/c mice (throughout the course of infection) was monitored by flow cytometry as described.20 Briefly, freshly sorted CD11C+ splenic DC were incubated with PBS containing 10% normal goat serum for 30 min and then with monoclonal antibodies (mAb) MKD6 or isotype-matched control mAb for 15 min. Following two washes with PBS containing 5% goat serum, PE-conjugated second antibody (goat anti-mouse immunoglobulin) was added. After 15 min incubation, the cells were washed, resuspended in PBS containing 2% goat serum and analysed by FACS Calibur (Becton Dickinson) using the program Cell Quest. Ten thousand cells were collected for each sample and the fluorescence intensity was measured on a logarithmic scale. Two-colour flow cytometry was performed for intracellular analysis of IL-12 by CD11C+ splenic DC at the single-cell level. Splenic DC were partially enriched from uninfected and L. donovani-infected (at different post-infection period) BALB/c mice and were incubated with media alone or with heat-killed Staphylococcus aureus (SAC) Cowan strain I (1:1000 final dilution, Pansorbin, Calbiochem Behring Corp., CA) for 18 hr at 37° in 5% CO2. To cause the intracellular accumulation of newly synthesized proteins, brefeldin A (1 µg/ml) was added to the cells in culture for last 4 hr. Cells were harvested and stained for surface expression of CD11C by FITC-conjugated anti-CD11C. After washing, cells were permeabilized by treatment with FACS™ permeabilizing solution. Permeabilized cells were treated with PE-conjugated anti-mouse IL-12p40 or control antibody. Analysis of washed cells was performed by FACS Calibur and data are displayed as two-colour dot plots [anti-CD11C (FL1) versus anti-mouse IL-12 p40 (FL2)]. To make sure that only intracellular IL-12p40 was being detected, cells were stained with PE-conjugated anti-mouse IL-12p40 before permeabilization and gave < 0·2% fluorescent cells. Irrelevant isotype-matched control antibody also produced only 1·4% fluorescent cells.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed by Student’s t-test with the program Tadpole III (written by T.H. Caradoc-Davies, Wakari Hospital, Dunedin, New Zealand; published and distributed by Biosoft, Cambridge, UK).

Results

Course of in vivo replication of an Indian strain of L. donovani (strain AG83) in the spleen of BALB/c mice

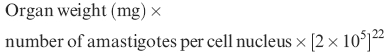

L. donovani infection is not lethal for mice. However, different mouse strains characteristically develop either a high or a minimal parasite load. BALB/c mice are susceptible to infection with the visceralizing species of L. donovani.24 Most studies of murine VL have been restricted to the liver of infected animals and show that BALB/c mice resolve hepatic infection with L. donovani over an 8–12-week period.15,25 We have confirmed this with an Indian strain of L. donovani (with respect to hepatic infection; results not shown). Following in vivo infection with this strain, increase in parasite load are not readily detectable in the spleen up to 1 month post-infection. Then, parasite numbers in the spleen begin to increase, reaching maximal levels at 4 month post-infection. Thereafter, parasite burden in the spleen declined (Fig. 1). The splenic parasite burden at 180 days post-infection was significantly less than that of 120 days (P < 0·02).

Figure 1.

The course of in vivo replication of an Indian strain of L. donovani (strain AG83) in the spleen of BALB/c mice. BALB/c mice were infected with 1 × 107 amastigotes of L. donovani. At the time indicated, the total parasite load per spleen was determined from stained tissue imprints as described in Materials and Methods. Data represent means± SD from three mice per time point.

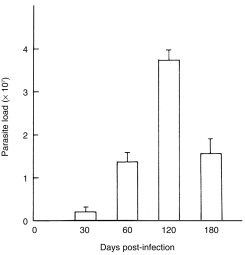

Evaluation of CD11C expression on the macrophages of L. donovani-infected BALB/c mice

Mouse DC-specific antigen DEC-205 has previously been shown to be up-regulated on macrophages during chronic stimulation.23 Expression of CD11C was evaluated on the splenic macrophages of L. donovani-infected mice. Splenic macrophages were purified from uninfected and L. donovani-infected (60 days post-infection) BALB/c mice and checked for the expression of CD11C (DC marker) and CD11b (macrophage marker). As shown in Fig. 2, 92·0% and 88·2% cells of macrophage enriched populations prepared from uninfected and L. donovani-infected mice, respectively, were positive for CD11b. Less than 7·0% cells were positive for CD11C in both cases. Minor contamination of DC in purified macrophages may be attributed to the observed marginal reactivity to anti-CD11C. As CD11C was not up-regulated in macrophages during visceral leishmaniasis, splenic DC were purified by sorting CD11C+ cells for further studies.

Figure 2.

One-parameter histograms of splenic macrophages purified from uninfected and L. donovani-infected (60 days post-infection) BALB/c mice after staining with anti-CD11C, anti-CD11b and respective control mAbs. The percentage of positive cells is given in each panel.

Functional properties of splenic DC throughout the course of L. donovani infection in BALB/c mice

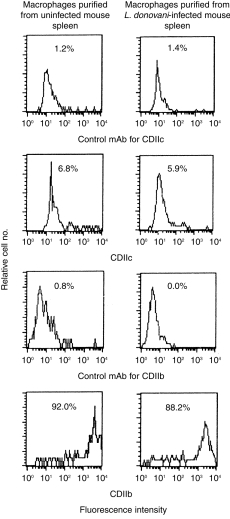

CD11C+ splenic DC were sorted from uninfected and L. donovani-infected (at different post-infection periods) BALB/c mice. Purity was always more than 90%. Dot plots of a representative experiment of partially enriched and sorted DC from uninfected BALB/c mice are shown in Fig. 3. DC with similar degree of purity (> 90%) were also obtained without any difficulty from BALB/c mice at different post-infection periods (not shown). All functional experiments were performed with sorted DC containing > 90% CD11C+ cells unless otherwise stated. Sorted DC from uninfected and L. donovani-infected BALB/c mice were tested for stimulation of allogeneic MLR. Graded numbers (1 × 104–2 × 104) of DC were used as stimulator cells and non-adherent splenocytes (2 × 105) of normal C57BL/6 mice were used as responders. Splenic DC of uninfected BALB/c mice induced a strong allospecific proliferative response in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 4). DC isolated from 30-day post-infected mice stimulated allogeneic MLR as efficiently as that obtained from uninfected mice. However, significant impairment in inducing allogeneic MLR was noticed with DC obtained from 60-day post-infected mice. Optimal suppression (60%) was detected with the lowest dose of DC (1 × 104 per well; P < 0·008). The degree of suppression of allogeneic MLR was reduced with higher doses of DC. With 1·5 × 104 and 2·0 × 104 DC per well, suppressin was reduced to 33% and 38%, respectively; these, however, were still significant (P < 0·03 for each comparison). This impairment continued up to 120 days post-infection.

Figure 3.

Purification of CD11C+ cells from BALB/c mice spleen by cell sorting. Splenic DC were partially enriched as described in Materials and Methods. Dot plots of partially enriched DC from uninfected BALB/c mice after staining with FITC-control antibody (a) and FITC-anti-CD11C antibody (b) are shown. CD11C+ cells were sorted from partially enriched DC after gating CD11C+ cells. (c) A rerun of sorted CD11C+ cells from normal BALB/c mice. The percentage of positive cells is given in the lower right quadrant of each panel.

Figure 4.

Induction of allogeneic MLR by CD11C+ splenic DC of BALB/c mice infected with L. donovani. Non-adherent splenocytes (2 × 105/well) of normal C57BL/6 mice were used as responders. Varying numbers of CD11C+ splenic DC (▵, 10 × 103 cells/well; •, 15 × 103 cells/well; ○, 20 × 103 cells/well), purified from uninfected and L. donovani infected (at different stages post-infection) BALB/c mice were used as stimulators. Allogeneic MLR was quantitated by [3H]thymidine uptake as described in Materials and Methods. [3H]thymidine uptake for stimulator cells alone or responder cells alone never exceeded 3000 ± 400 c.p.m. Data represent means± SD of triplicate wells at each time point. One representative experiment out of two with similar results is shown. *P < 0·03 versus DC from uninfected animals; **P < 0·008 versus DC from uninfected animals.

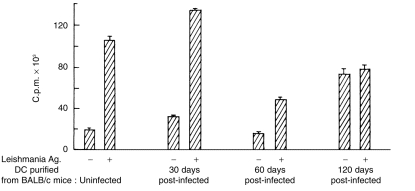

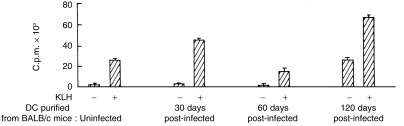

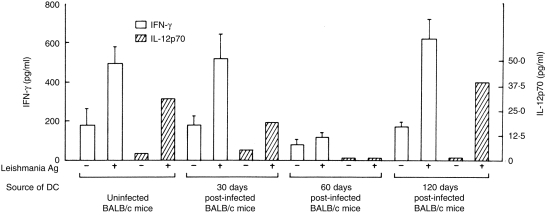

Antigen presentation by splenic DC was examined at different stages of post-infection. DC sorted from uninfected animals or from animals at different stages of infection were cultured with antigen-specific T cells in the absence and presence of L. donovani antigens or KLH. As observed with allogeneic MLR stimulation, no impairment in presenting L. donovani antigens or KLH was detected with DC from 30-day post-infected mice (Figs 5 and 6). DC from 60-day post-infected mice presented L. donovani antigens poorly (P < 0·005 compared to DC from uninfected or 1 month post-infected mice) or KLH (P < 0·006 compared to DC from uninfected mice; P < 0·05 compared to DC from 1 month post-infected mice) to T cells from sensitized animals (Figs 5 and 6). Poor presentation of leishmanial antigens by DC of 60-day post-infected mice was associated with undetectable levels of IL-12 and a barely detectable level of IFN-γ in the culture supernatants (Fig. 7). Partial recovery of the proliferative response of L. donovani antigen-primed T cells was noticed with DC purified from 120-day post-infected mice even in the absence of exogenously added L. donovani antigens. The magnitude of this response could not be further enhanced by the addition of L. donovani antigens (Fig. 5). Of interest, recovery of antigen presentation by DC of 120-day post-infected mice was associated with the detection of IL-12 and IFN-γ in the supernatants (Fig. 7). It is possible that DC of 120-day post-infected mice induced proliferation of L. donovani-specific T cells even in absence of exogenous parasite antigens by presenting endogenous parasite antigens. This was supported by the fact that only background response was detected when the same DC preparations were added to KLH-specific T cells (Fig. 6). Proliferative response of KLH-specific T cells was detected when DC purified from 120-day post-infected mice were added along with exogenous KLH (P < 0·004; Fig. 6).

Figure 5.

Presentation of soluble L. donovani antigens by CD11C+ splenic DC of uninfected and L. donovani-infected BALB/c mice to Leishmania antigen-primed T cells. CD11C+ splenic DC (2·5 × 104/well) purified from BALB/c mice throughout the course of L. donovani infection were cultured with lymph node cells (2 × 105/well) of soluble L. donovani promastigote antigens primed BALB/c mice in the absence and presence of soluble L. donovani promastigote antigens (25 µg/ml). Proliferation of T cells was monitored by [3H]thymidine uptake as described in Materials and Methods. Data represent means± SD of triplicate cultures. One representative experiment out of two with similar results is shown.

Figure 6.

Presentation of KLH by CD11C+ splenic DC of uninfected and L. donovani-infected BALB/c mice to KLH-primed T cells. CD11C+ splenic DC (2·5 × 104/well) purified from BALB/c mice at indicated post-infection period were cultured with lymph node cells (2 × 105/well) of KLH-primed BALB/c mice in the absence and presence of KLH (10 µg/ml). Data represent means± SD of triplicate cultures. One representative experiment out of two with similar results is shown.

Figure 7.

Effect of CD11C+ splenic DC of uninfected and L. donovani-infected BALB/c mice on IL-12 and IFN-γ production by Leishmania antigen-primed T cells. Cultures were set up as described in the legend of Fig. 5. Supernatants were harvested after 24 hr and 72 hr and assayed by ELISA for IL-12p70 and IFN-γ, repectively. Data represent means± SD of triplicate cultures. One representative experiment out of two is shown.

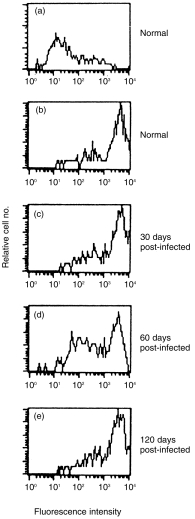

Suppressed surface expression of MHC class II on splenic DC at 2 months post-infection and enhancement at 4 months post-infection

No significant changes were observed in surface staining of MHC class II molecules with freshly sorted DC from 1 month post-infected mice compared to uninfected controls. However, the intensity of MHC class II molecules on the surface of CD11C+ DC purified from 2-month post-infected mice was of interest. Only a fraction of CD11C+ cells had reduced surface expression of MHC class II and the remaining were class IIhi (Fig. 8). The possibility that a subset of DC were infected with L. donovani in vivo resulting in reduced class II expression remains to be determined. The surface MHC class II expression on DC was enhanced on 4 month post-infection and reached almost normal levels (Fig. 8).

Figure 8.

One-parameter histograms of CD11C+ splenic DC of uninfected and L. donovani-infected BALB/c mice after staining with anti-MHC class II antibody MKD6. Freshly sorted CD11C+ cells were immediately surface stained for MHC class II. (a) Staining of splenic DC purified from uninfected BALB/c mice with isotype matched control mAb. Splenic DC purified from L. donovani-infected mice (throughout the course of infection) produced similar histograms after staining with control mAb. (b–e) Staining with MKD6; (b) splenic DC purified from uninfected mice; (c) splenic DC purified from 1-month post-infected mice; (d) splenic DC purified from 2-month post-infected mice; (e) splenic DC purified from 4-month post-infected mice. One representative experiment out of two is shown.

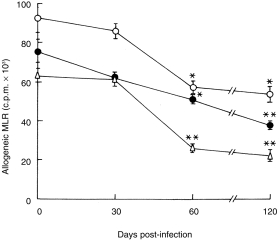

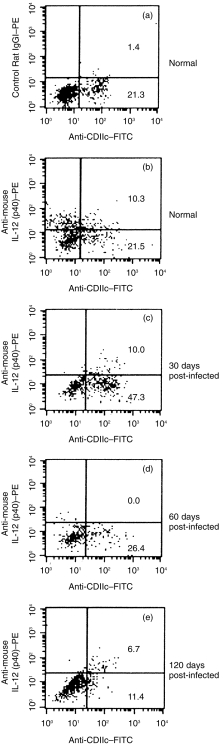

Status of intracellular IL-12p40 in splenic DC of uninfected and L. donovani-infected BALB/c mice after in vitro stimulation with heat-killed Staphylococcus aureus (SAC)

To determine whether murine visceral leishmaniasis affects IL-12p40 production by splenic DC, intracellular IL-12p40 was analysed on a single-cell basis in CD11C+ cells isolated from BALB/c mice spleen throughout the course of L. donovani infection. Partially enriched splenic DC preparations were stimulated in vitro with SAC, permeabilized, and two-colour flow cytometry for CD11C and IL-12p40 was performed. Brefeldin A was added to the cultures to cause intracellular accumulation of newly synthesized proteins by arresting their transport in the Golgi complex. CD11C+ cells of normal or L. donovani-infected mice cultured with media alone did not express detectable IL-12p40 (not shown). However, intracellular IL-12p40 status upon in vitro stimulation with SAC in CD11C+ or CD11C– cells of BALB/c mice throughout the course of L. donovani infection was very different. About 32% of the CD11C+ cells of uninfected mice were positive for IL-12p40 (Fig. 9b). Of note, a significant proportion of CD11C– cells of uninfected mice were also positive for IL-12p40 (Fig. 9b). This might be attributed to macrophages and/or B cells. IL-12p40 production was reduced in CD11C+ cells of 30-day post-infected mice (only 17·4% CD11C+ cells were positive for IL-12; Fig. 9c). CD11C– cells of the same mice lacked intracellular IL-12p40 (Fig. 9c). Intracellular IL-12p40 was virtually undetectable in CD11C+ or CD11C– cells of 60-day post-infected mice (Fig. 9d). Interestingly, only CD11C+ cells but not CD11C– cells of 120-day post-infected mice restored IL-12p40 production (37·0% of the CD11C+ cells were positive for IL-12p40) upon stimulation with SAC (Fig. 9e).

Figure 9.

Intracellular IL-12p40 expression by CD11C+ splenic DC of uninfected and L. donovani-infected BALB/c mice after in vitro stimulation with SAC. Partially enriched DC were cultured with heat-killed SAC for 18 hr as described in Materials and Methods. After surface staining for CD11C (FL1), cells were permeabilized and stained with isotype matched control rat antibody (a) or with mAb against IL-12p40 (FL2) (b–e). The percentage of CD11C+ cells in partially enriched splenic DC preparations from uninfected and L. donovani-infected BALB/c mice varied considerably. However, CD11C+ cells from uninfected and L. donovani-infected mice gave only background staining (< 1·4% cells were positive) after intracellular staining with control rat antibody. Percentage of positive cells is given in the upper and lower right quadrants.

Discussion

Dendritic cells contribute significantly to the development of cellular immune response. Reports on the role of DC in visceral leishmaniasis are limited although interaction of cells of DC lineage by other species of Leishmania (L. major, L. mexicana) has been suggested.26 Langerhans cells (LC), the dendritic cells of the skin, contribute to the development of cellular immune response during the initial phase of L. major infection and maintenance of T-cell memory by uptake of Leishmania organism through phagocytosis and presentation of Leishmania antigens to antigen-specific primed T cells.13,14 In murine visceral leishmaniasis DC were shown to be the critical source of early IL-12 production following infection.16 Destruction of follicular dendritic cells during chronic experimental visceral leishmaniasis was also suggested.15

In this communication, functions of splenic DC throughout the course of L. donovani infection in BALB/c mice were studied. Mouse DC-specific antigen DEC-205 was reportedly up-regulated on macrophages during visceral leishmaniasis.23 As CD11C antigen was not up-regulated during L. donovani infection, sorted CD11C+ cells were used as a source of splenic DC. L. donovani infection in BALB/c mice is not fatal as the infection is self limiting. L. donovani-infected BALB/c mice resolve infection in the liver early (over an 8–12-week period). On the other hand, parasite burden in the spleen decline slowly after reaching a maximum level at four month post-infection. The results of this study demonstrate that functions of CD11C+ splenic DC isolated from L. donovani-infected mice throughout the course of infection correlate with the parasite replication in the spleen. After a lag of 1 month, antigen presentation and induction of allogeneic MLR by CD11C+ splenic DC were impaired in experimental visceral leishmaniasis. Although the capacity of DC to induce allogeneic MLR continued to be suppressed up to 4 months post-infection, the antigen-presenting ability of this cell subset re-emerged at this stage. Our data indicate that in murine visceral leishmaniasis, endogenous L. donovani antigens are carried over by splenic DC from 120-day post-infected BALB/c mice. In an earlier report, Moll et al.14 indicated that in genetically resistant C57BL/6 mice, endogenous L. major antigens were carried over by lymph node DC after recovery from L. major infection. Our results are not in agreement with the previous report. Differences in the strains of mice and Leishmania and also the origin of DC used may account for the differences.

Functional impairment of splenic DC at 2 months post-infection was associated with their impaired production of IL-12, reduced surface expression of MHC class II antigen, ability to suppress IFN-γ production by Leishmania antigen-primed T cells and correlated with the progression of L. donovani infection in the spleen. Macrophages, particularly those infected with Leishmania donovani make copious quantities of prostaglandins.27 Furthermore, high level of IL-10 is produced during L. donovani infection.25 Elevated levels of prostaglandin E2 was shown to promote type 2 responses by stably impairing the ability of maturing DC to produce IL-12.28 IL-10 was capable of converting immature DC into tolerogenic APC and down-regulate surface expression of human leucocyte antigen (HLA)-DR.29 It is thus possible that prostaglandins and IL-10, produced during L. donovani infection, might be responsible for the loss of DC function at this time of post-infection. The impairment in antigen presentation by splenic DC at this stage of post-infection was not parasite specific as the same DC also failed to drive KLH-specific T cells. Of note, cells that do not belong to the DC lineage but capable of producing IL-12 (macrophages, B cells) also failed to produce intracellular IL-12 in response to exogenous stimulus at this stage of infection. In contrast, presentation of endogenous parasite antigen or other unrelated antigen by splenic DC at four month post-infection was associated with their normal surface expression of MHC class II molecules, IL-12 production and ability to induce IFN-γ by Leishmania antigen-primed T cells. However, CD11C–cells were unable to produce IL-12 at this stage of post-infection. Functional recovery of CD11C+ splenic DC at 4 months post-infection coincided with the onset of control over splenic parasite replication.

Of note, splenic DC of 4-month post-infected mice had virtually normal levels of IL-12 production, antigen presentation and surface expression of MHC class II antigens but continued to have impaired ability to induce allogeneic MLR. A similar phenomenon was reported earlier in human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-infected patients. Langerhans cells of acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS) patients, in spite of having normal levels of HLA-DR expression, stimulated allogeneic T cells less well compared to Langerhans cells of HIV– individuals.30 Also, APC from HIV+ patients presented recall antigen to syngeneic T cells in spite of impaired ability to induce allogeneic MLR.30

In human visceral leishmaniasis31 and in the murine Leishmania major model,32,33 IL-12 was shown to enhance a Th1-type response. IL-12 was also shown to act as an effective adjuvant for the initiation of protective cell-mediated immunity in murine L. major infection.34 DC, but not macrophages, induced IL-12 immediately following L. donovani infection in murine visceral leishmaniasis.16 Our study demonstrates that murine visceral leishmaniasis modulates splenic DC functions. Functional impairment of splenic DC was associated with the parasite replication in the spleen and reversal of functional impairment of splenic DC, detected only at the late stage of infection, was associated with the control of splenic parasite replication.

Acknowledgments

The work was supported by the Council of Scientific and Industrial Research, Department of Science & Technology and Department of Biotechnology, Government of India. We thank S. K. Sahoo and D. Das for art work and A. Manna for help in preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1.Bogdan C, Rollinghoff M, Solbach W. Evasion strategies of Leishmania parasites. Parasitol Today. 1990;6:183. doi: 10.1016/0169-4758(90)90350-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Reiner SL, Locksley RM. The regulation of immunity to Leishmania major. Annu Rev Immunol. 1995;13:151. doi: 10.1146/annurev.iy.13.040195.001055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Carvalho EM, Teixeira RS, Johnson WD. Cell-mediated immunity in American visceral leishmaniasis: reversible immunosuppression during acute infection. Infect Immun. 1981;33:498. doi: 10.1128/iai.33.2.498-500.1981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Haldar JP, Ghose S, Saha KC, Ghose AC. Cell-mediated immune response in Indian Kala-azar and post Kala-azar dermal leishmaniasis. Infect Immun. 1983;42:702. doi: 10.1128/iai.42.2.702-707.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Harms G, Pedrosa C, Omena S, Feldmeier H, Zwingenberger K. Natural killer cell activity in visceral leishmaniasis. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1991;85:54. doi: 10.1016/0035-9203(91)90154-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Manna PP, Bharadwaj D, Bhattacharya S, et al. Impairment of natural killer cell activity in Indian Kala-azar: restoration of activity by interleukin 2 but not by alpha or gamma interferon. Infect Immun. 1993;61:3565. doi: 10.1128/iai.61.8.3565-3569.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rodrigues V, Silva JSD, Campos-neto A. Selective inability of spleen antigen presenting cells from Leishmania donovani infected hamsters to mediate specific T cell proliferation to parasite antigens. Parasite Immunol. 1992;14:49. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3024.1992.tb00005.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Reiner NE. Parasite–accessory cell interactions in murine leishmaniasis I. Evasion and stimulus-dependent suppression of the macrophage interleukin 1 response by Leishmania donovani. J Immunol. 1987;138:1919. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Reiner NE, NGW, McMaster WR. Parasite–accessory cell interactions in murine leishmaniasis II. Leishmania donovani suppresses macrophage expression of class I and class II major histocompatability complex gene products. J Immunol. 1987;138:1926. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Steinman RM, Cohn ZA. Identification of a novel cell type in peripheral lymphoid organs of mice. I. Morphology, quantitation, tissue distribution. J Exp Med. 1973;137:1142. doi: 10.1084/jem.137.5.1142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Steinman RM. The dendritic cell system and its role in immunogenicity. Annu Rev Immunol. 1991;9:271. doi: 10.1146/annurev.iy.09.040191.001415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Steven EM, Nancy AH, Mark L, et al. Dendritic cells produce IL-12 and direct the development of Th1 cells from naive CD4+ T cells. J Immunol. 1995;154:5071. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Christine B, Harald F, Klemens R, Martin Heidrun M. Parasitism of epidermal langerhans cells in experimental cutaneous leishmaniasis with Leishmania major. J Infect Dis. 1993;167:418. doi: 10.1093/infdis/167.2.418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Moll H, Flohe S, Rollinghoff M. Dendritic cells in Leishmania major-immune mice harbor persistent parasites and mediate an antigen specific T cell immune response. Eur J Immunol. 1995;25:693. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830250310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Smelt SC, Engwerda CR, Mccrossen M, Kaye PM. Destruction of follicular dendritic cells during chronic visceral leishmaniasis. J Immunol. 1997;158:3813. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gorak PMA, Engwerda CR, Kaye PM. Dendritic cells, but not macrophages, produce IL-12 immediately following Leishmania donovani infection. Eur J Immunol. 1998;28:687. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-4141(199802)28:02<687::AID-IMMU687>3.0.CO;2-N. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bruce J, Symington FW, Mckearn TJ, Sprent J. A monoclonal antibody discriminating between subsets of T and B cells. J Immunol. 1981;127:2496. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kappler JW, Skidmore B, White J, Marrack P. Antigen inducible H-2-restricted, interleukin-12 producing T cell hybridomas. Lack of independent antigen and H-2 recognition. J Exp Med. 1981;153:1198. doi: 10.1084/jem.153.5.1198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Saikh KU, Nishikawa AH, Dillon SB. Detection of enhanced cytotoxic T lymphocyte response with splenic dendritic cells enriched by a simple sequential adherence method. Viral Immunol. 1996;9:121. doi: 10.1089/vim.1996.9.121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bandyopadhyay S, Perussia B, Trinchieri G, Miller DS, Starr SE. Requirement for HLA-DR+ accessory cells in natural killing of cytomegalovirus-infected fibroblasts. J Exp Med. 1986;164:180. doi: 10.1084/jem.164.1.180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ghosh AK, Bhattacharya FK, Ghosh DK. Leishmania donovani: amastigote inhibition and mode of action of Berberine. Exp Parasitol. 1985;60:404. doi: 10.1016/0014-4894(85)90047-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Stauber LA, Franchino EM, Grun J. An eight day method for screening compounds against Leishmania donovani in the golden hamster. J Protozool. 1958;5:269. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kaye PM. Inflammatory cells in murine visceral leishmaniasis express a dendritic cell marker. Clin Exp Immunol. 1987;70:515. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Murray HW, Masur H, Keithly JS. Cell-mediated immune response in experimental visceral leishmaniasis. I. Correlation between resistance to L. donovani and lymphokine-generating capacity. J Immunol. 1982;129:344. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Miralles GD, Stoeckle MY, Mcdermott DF, Finkelman FD, Murray HW. Th1 and Th2 associated cytokines in experimental visceral leishmaniasis. Infect Immun. 1994;62:1058. doi: 10.1128/iai.62.3.1058-1063.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Williams RO. Invasion of murine dendritic cells by Leishmania major and L. mexicana mexicana. J Parasitol. 1988;74:186. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Reiner NE, Malemud CJ. Arachidonic acid metabolism in murine leishmaniasis (Donovani): ex-vivo evidence for increased cycloxygenase & 5-lipoxygenase activity in spleen cells. Cell Immunol. 1984;88:501. doi: 10.1016/0008-8749(84)90181-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kalinski P, Hilkens CMU, Snijders A, Snijdewint FGM, Kapsenberg ML. IL-12-deficient dendritic cells, generated in the presence of prostaglandin E2, promote type 2 cytokine productin in maturing human naive T helper cells. J Immunol. 1997;159:28. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Steinbrink K, Wolfl M, Jonuleit H, Knop J, Enk AH. Induction of tolerance by IL-10-treated dendritic cells. J Immunol. 1997;159:4772. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Blauuelt A, Clerici M, Lucey DR, et al. Functional studies of epidermal Langerhans cells and blood monocytes in HIV-infected persons. J Immunol. 1995;154:3506. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ghalib HW, Whittle JA, Kubin M, et al. IL-12 enhances Th1-type responses in human Leishmania donovani infection. J Immunol. 1995;154:4623. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Heinzel FP, Schoenhaut DS, Rerko RM, Rosser LE, Gately MK. Recombinant IL-12 cures mice infected with Leishmania major. J Exp Med. 1993;177:1505. doi: 10.1084/jem.177.5.1505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sypek JP, Chung CL, Mayor SEH, et al. Resolution of cutaneous leishmaniasis: interleukin 12 initiates a protective T helper type 1 immune response. J Exp Med. 1993;177:1797. doi: 10.1084/jem.177.6.1797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Afonso LC, Scharton TM, Vieira LQ, Wysocka M, Trinchieri G, Scott P. The adjuvant effect of interleukin-12 in a vaccine against Leishmania major. Science. 1994;263:235. doi: 10.1126/science.7904381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]