Abstract

The present study investigated whether an explanation for the conflicting reports on the interleukin-2 (IL-2) status of amniotic fluid is due to the presence of IL-15 which shares biological activities with IL-2 and utilizes the IL-2 receptor β-chain. Amniotic fluids from 45 normally progressing pregnancies between 14 and 16 weeks after the last menstrual period were assayed for IL-2 and IL-15 by bioassay and enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). The ability of amniotic fluids to induce cytotoxic T lymphoblastoid line-2 (CTLL-2) cell proliferation was demonstrated to be dependent upon bioassay culture conditions. In serum-free medium each amniotic fluid stimulated CTLL-2 proliferation with a mean level of IL-2-like bioactivity of 14·7 ± 2·3 ng/ml but amniotic fluids failed to induce CTLL-2 proliferation in serum-supplemented medium. Treatment with neutralizing anti-IL-2 or anti-IL-15 antibodies failed to inhibit amniotic fluid-induced CTLL cell proliferation in serum-free medium, indicating a lack of IL-2 and IL-15 bioactivity. In contrast, treatment with anti-IL-2 receptor β-chain antibody significantly reduced amniotic fluid-induced proliferation. The lack of IL-2 and IL-15 activity in amniotic fluids was confirmed using ELISA. Although high levels of IL-15 immunoactivity were detected in all samples, specificity controls showed a lack of specific IL-15 immunoactivity in amniotic fluid. Pretreatment of amniotic fluids with 100–500 ng/ml mouse immunoglobulin G abrogated IL-15 immunoactivity, indicating that amniotic fluid contains molecules binding to Fc regions of immunoglobulins and responsible for false ELISA positivity. These studies unequivocally show that amniotic fluid lacks IL-2 and IL-15 but can stimulate CTLL-2 cell proliferation via the IL-2 receptor β-chain. The absence of IL-2 and IL-15 in normal mid-trimester amniotic fluid suggests that the cytokine profile of human pregnancy appears to be associated with a bias against type 1 cytokines within the feto–placental unit.

Introduction

Emerging evidence suggests that bi-directional cytokine interactions between the maternal immune system and the feto–placental unit are crucial for the maternal–fetal immune relationship and for successful pregnancy outcome.1–4 Several cytokines, including interleukin-1 (IL-1), IL-6, IL-8, IL-10, transforming growth factor-β1 (TGF-β1) and TGF-β2, tumour necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) and granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF) are regular features of human amniotic fluid from normally progressing early pregnancies, and their levels increase during gestation, labour and intrauterine infection.5–13 Normal amniotic fluid has been reported to contain low levels of IL-2,14 even though T helper 1 (Th1) -type cytokines are generally held to be harmful to the fetus and to pregnancy maintenance.2,3,15 The IL-2 status of amniotic fluid, however, is unclear as many laboratories have reported conflicting findings using enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (ELISAs) and bioassays.16–23 IL-15, however, shares many biological activities with IL-2, mediates its effects partly through the IL-2 receptor (IL-2R) β-chain, and IL-15 mRNA and peptide are abundant in human placenta and amniochorion.24–27 Recently, increased levels of IL-15 in the amniotic fluid of women with preterm labour compared with term and second-trimester samples have been reported.27 We therefore wondered whether an explanation for the conflicting reports of IL-2-like activity of amniotic fluid is due to the presence of IL-15. We report that amniotic fluid from normally progressing pregnancies in the second trimester lacks both IL-2 and IL-15 activity, interacts with the β-chain of the IL-2R, thereby inducing bioassay proliferation, and contains molecules binding to Fc of immunoglobulin and responsible for false ELISA positivity.

Materials and methods

Subjects and tissue samples

Amniotic fluid from normally progressing and uncomplicated pregnancies between 14 and 16 completed weeks from the last menstrual period were obtained from specimens submitted for cytogenetic analysis. The 45 samples, which contained normal levels of alpha-fetoprotein, were spun to remove cellular material, divided into two fractions which were then either filter sterilized (0·2 µm) or left unfiltered before storage in aliquots at − 80° to avoid repeated freeze–thawing cycles.

IL-2 ELISA

Amniotic fluids were assayed for IL-2 using either a commercialized quantified human IL-2 ELISA (R & D Systems Europe Ltd, Abingdon, UK) or an IL-2-matched antibody pair (Genzyme Diagnostics, West Malling, UK) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Samples were routinely tested in duplicates at 50% v/v in phosphate-buffered saline–bovine serum albumin (PBS-BSA) diluent to prevent non-specific binding. ELISA plates were read at 490 nm using a Dynatech ELISA reader. The IL-2 concentrations for each amniotic fluid were calculated from recombinant human IL-2 (rhIL-2) standard dose–response curves using the computer package biolinx. In other experiments, standard curves of rhIL-2 were generated in the presence of 50% v/v amniotic fluid in order to determine whether IL-2 activity had been denatured in the presence of amniotic fluid. The detection limit for the ELISA was 10 pg/ml (R & D Systems) and 3·9 pg/ml (Genzyme Diagnostics); the results were expressed in pg/ml.

IL-15 ELISA

A matched antibody pair for hIL-15 was used to quantify IL-15 in amniotic fluids, following the manufacturer’s (R & D Systems) protocol. The sensitivity of the ELISA was 18·5 pg/ml defined using the National Institute for Biological Standards and Control (NIBSC) standard IL-15 preparation (95/554).

CTLL-2 bioassay for IL-2 and IL-15

The ability of amniotic fluid to stimulate the proliferation of CTLL-2 cells was assessed. CTLL-2 cells were routinely maintained in culture medium RPMI-1640 supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum (FCS), 2 mm l-glutamine, 50 U/ml penicillin, 50 µg/ml streptomycin and rhIL-2 (0·4 ng/ml; First Link Ltd, Brierly Hill, West Midlands, UK). For the bioassay, CTLL-2 cells were cultured overnight in RPMI-1640 supplemented with 10% FCS (medium RF10) to increase their sensitivity to IL-2. Serial dilutions of amniotic fluid (50% v/v to 0·39% v/v) in triplicates were incubated with 1 × 104 CTLL-2 cells in 200 µl total volume of serum-free RPMI-1640 supplemented with human serum albumin (HSA; 2 mg/ml) in flat-bottomed 96-well microtitre plates for 20 hr at 37° in 5% CO2 as described previously.12 In other CTLL-2 bioassays, RF10 was substituted for HSA-supplemented RPMI-1640. Cultures were then pulsed with 0·4 µCi/well [3H]thymidine per well and harvested 16 hr later for direct matrix beta counting. The IL-2 activity in each amniotic fluid was calculated by relating the c.p.m. data obtained to rhIL-2 standard dose–response curves run in parallel using regression analysis. The IL-15 activity for each sample was similarly determined from standard curves of rhIL-15 (First Link Ltd) run in parallel.

In parallel cultures, CTLL-2 cells were treated with neutralizing anti-human IL-2 (10 µg/ml; Genzyme), neutralizing anti-human IL-15 (5–20 µg/ml; Genzyme) in the presence of either amniotic fluid, rhIL-2, or rhIL-15. Anti-IL-15 (5 µg/ml) specifically neutralized in excess of 80% of the CTLL-2 proliferation induced by 0·05–5 ng/ml rhIL-15 but had no effect on rhIL-2. Anti-IL-2 (10 µg/ml) neutralized approximately 90% of CTLL-2 proliferation specifically induced by 1–5 ng/ml rhIL-2 but had no effect on rhIL-15. Normal mouse, rat and rabbit immunoglobulin G (IgG) were used as isotype-matched controls. In experiments with anti-IL-2 or anti-IL-15, amniotic fluid, rhIL-2, or rhIL-15 were pretreated with neutralizing antibody for 1–2 hr before addition to the CTLL-2 cells. To eliminate the possibility of loss of neutralizing antibody activity due to denaturation by amniotic fluid, additional experiments were run in which anti-IL-15 antibody was first pretreated with amniotic fluid for 1–2 hr then added to 0·05 ng/ml rhIL-15 followed by co-culture for a further 1 hr before final addition to CTLL-2 cells. In bioassays where the effects of amniotic fluid on IL-2R β-chain activity were studied, CTLL-2 cells were pretreated with anti-CD122 (4–8 µg/ml) for 45 min before the addition of either amniotic fluid, rhIL-2, or rhIL-15 to the wells. This neutralized in excess of 80% rhIL-15 (0·125 ng/ml)-induced CTLL-2 proliferation.

Results

CTLL-2 bioassay

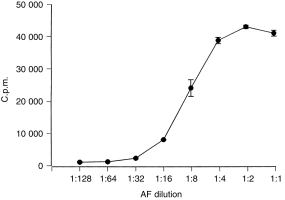

The ability of amniotic fluids to induce CTLL-2 proliferation was critically dependent on the bioassay conditions. When the bioassay was performed in RF10 all samples (n = 24) failed to induce CTLL-2 proliferation (data not shown). In contrast when the bioassay was carried out in FCS-free, HSA-supplemented RPMI-1640, amniotic fluids (n = 16) significantly stimulated CTLL-2 proliferation with a mean level of IL-2-like activity of 14·7 ± 2·3 ng/ml (Table 1). In each case, amniotic fluid stimulated CTLL-2 proliferation in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 1).

Table 1.

Amniotic fluid induces CTLL-2 proliferation in HSA-supplemented FCS-free media

| Amniotic fluid | IL-2 activity* (ng/ml) |

|---|---|

| 1 | 16·7 ± 5·2 |

| 2 | 19·8 ± 7·7 |

| 3 | 6·6 ± 0·7 |

| 4 | 24·4 ± 9·6 |

| 5 | 14·8 ± 3·5 |

| 6 | 23·5 ± 8·6 |

| 7 | 8·6 ± 4·7 |

| 8 | 9·2 ± 4·4 |

| 9 | 4·8 ± 1·4 |

| 10 | 29·8 ± 8·5 |

| 11 | 3·3 ± 0·7 |

| 12 | 8·2 ± 4·6 |

| 13 | 8·7 ± 8·7 |

| 14 | 26·9 ± 7·6 |

| 15 | 26·5 ± 7·9 |

| 16 | 3·4 ± 0·9 |

Mean±SE, based on at least three CTLL-2 bioassays per amniotic fluid.

Figure 1.

Amniotic fluid stimulates CTLL-2 proliferation in a dose-dependent manner. CTLL-2 cells (1 × 104/well) were cultured for 36 hr in amniotic fluid. Results are expressed as the means±SEM of incorporated c.p.m. of triplicate cultures and are representative of 21 samples.

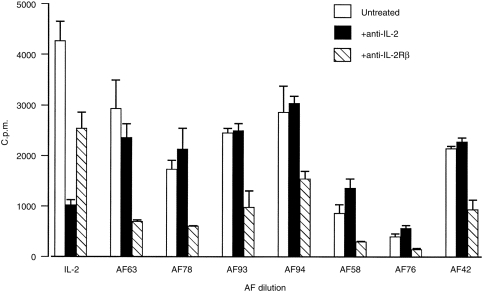

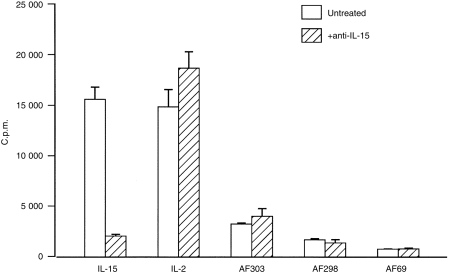

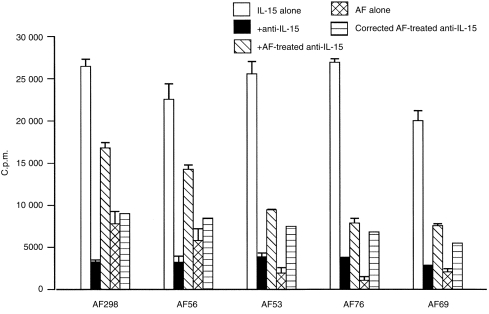

Amniotic fluid (6·25% v/v, approximately 1 ng/ml IL-2-like activity) -induced CTLL-2 proliferation was not inhibited with neutralizing anti-IL-2 antibody; in contrast CTLL-2 proliferation induced by rhIL-2 (1–5 ng/ml) was significantly inhibited by IL-2-neutralizing antibody (Fig. 2). To establish whether the ability of amniotic fluid to induce CTLL-2 proliferation was due to its IL-15 activity, samples were pretreated with neutralizing anti-IL-15 antibody (Fig. 3). Anti-IL-15-treated amniotic fluid did not inhibit amniotic fluid-induced CTLL-2 proliferation although this antibody inhibited rhIL-15 (0·0125 ng/ml) -induced CTLL-2 proliferation. The specificity of the antibody was shown by its inability to inhibit IL-2 (1–5 ng/ml) -induced CTLL-2 proliferation. In order to exclude the possibility that amniotic fluid had denatured the anti-IL-15 antibody the effectiveness of amniotic fluid-treated anti-IL-15 antibody to neutralize rhIL-15-induced CTLL-2 proliferation was then assessed (Fig. 4). These findings indicate that the failure of neutralizing anti-IL-15 antibody to inhibit amniotic fluid-induced CTLL-2 proliferation was not due to denaturation by amniotic fluid. In contrast neutralizing anti-CD122 pretreatment significantly inhibited amniotic fluid-induced CTLL-2 proliferation (Fig. 2). Overall, the bioassay data indicated that amniotic fluid can induce CTLL-2 cell proliferation via the IL-2R β-chain (CD122) and that this bioactivity is not due to the presence of IL-2 or IL-15.

Figure 2.

Amniotic fluid-induced CTLL-2 proliferation is not inhibited by anti-IL-2 antibody but is inhibited by anti-CD122 antibody. CTLL-2 cells (1 × 104/well) were cultured in either amniotic fluid (6·25% v/v) or rhIL-2 (1 ng/ml) in the presence of IL-2 antibody (10 µg/ml) or anti-CD122 (4–8 µg/ml). CTLL-2 cells were pretreated with anti-CD122 for 45 min before addition of amniotic fluid or rhIL-2 to the wells. Amniotic fluid and rhIL-2 were pretreated with anti-IL-2 antibody for 90 min before addition to CTLL-2 cells. Results are representative of six experiments in which 18 amniotic fluids were assayed.

Figure 3.

Amniotic fluid-induced CTLL-2 proliferation is not inhibited by anti-IL-15 antibody. CTLL-2 cells (1 × 104/well) were cultured for 36 hr in amniotic fluid (6·25% v/v), rhIL-15 (0·05 ng/ml), or rhIL-2 (1 ng/ml) in the presence of IL-15 antibody (5 µg/ml). Before addition to CTLL-2 cells amniotic fluids, rhIL-2 and rhIL-15 were incubated with anti-IL-15 antibody for 90 min. Results are representative of five experiments in which 14 amniotic fluids were tested.

Figure 4.

The inability of anti-IL-15 antibody to inhibit amniotic fluid-induced CTLL-2 proliferation is not due to denaturation of IL-15 antibody. CTLL-2 cells (1 × 104/well) were cultured for 36 hr with rhIL-15 (0·05 ng/ml) in the presence of either IL-15 antibody (5 µg/ml) or amniotic fluid-pretreated IL-15 antibody. CTLL-2 cells were also cultured with amniotic fluid (6·25% v/v) alone. For these experiments anti-IL-15 antibody was incubated with amniotic fluids for 90 min and then with rhIL-15 for a further 60 min before addition to CTLL-2 cells. The corrected amniotic fluid-treated anti-IL-15 takes into account the stimulatory effect of amniotic fluid on CTLL-2 cell proliferation when assessing the neutralizing effect of amniotic fluid-treated anti-IL-15 on IL-15-induced CTLL-2 proliferation. Results are representative of four experiments in which seven amniotic fluids were tested.

IL-2 ELISA

The lack of IL-2 in amniotic fluid was confirmed using two IL-2-specific ELISAs. No immunoactive IL-2 was detected in a panel of 30 amniotic fluids which had previously stimulated CTLL-2 proliferation. Amniotic fluid lacked detectable IL-2 activity when assayed at 100% v/v to 1% v/v (data not shown). When the rhIL-2 standard (223·75 pg/ml) was made up in 50% v/v amniotic fluid in order to exclude the possibility that amniotic fluid had denatured the matched pair of IL-2 antibodies, the sensitivity of the IL-2 ELISA to detect rhIL-2 was not impaired.

lL-15 ELISA

In contrast to the negative IL-2 ELISA findings IL-15-specific ELISAs appeared to detect high levels of IL-15 immunoactivity in amniotic fluid (n = 29). A marked difference in IL-15 activity, however, was detected between paired filter-sterilized and unfiltered samples. IL-15 levels in unfiltered amniotic fluid ranged between 60·4 and 308 pg/ml with a mean (± SEM) value of 119 ± 9·3 pg/ml. This activity was significantly reduced in the paired filtered sample to 41·6 ± 3·5 pg/ml, ranging from 20·9 to 73·7 pg/ml (P = 0·001).

Filtration, however, did not affect rhIL-15 immunoactivity; IL-15 levels of 251, 240 and 247 pg/ml were detected after filtration of rhIL-15 (250 pg/ml) made up in either PBS, HSA (2 mg/ml), or amniotic fluid (100% v/v), respectively. Subsequently the specificity of the matched IL-15 antibody pairs was assessed by varying either the capture antibody, the detection antibody, or the test unfiltered sample/cytokine (Table 2). In all ELISAs a rhIL-15 standard curve was included. The IL-15 ELISA did not cross-react with either rhIL-2, rhIL-4, or rhIL-6. When third-party capture antibody (anti-IL-6, 1 µg/ml, Genzyme) was substituted for anti-IL-15 antibody no detectable optical density (OD) absorbance was obtained with rhIL-15 but test amniotic fluids gave OD values equivalent to mean IL-15 values of 92·2 ± 21·1 pg/m (n = 3). When mouse IgG (1 µg/ml)was substituted for anti-IL-15 capture antibody, positive OD readings were obtained for amniotic fluid with an IL-15 equivalent value of 288·6 pg/ml. Pretreatment of amniotic fluid for 1 hr at 37° with either 100 ng/ml or 500 ng/ml mouse IgG followed by centrifugation at 10 000 g significantly reduced detectable IL-15 activity compared with controls (Table 3). Pretreatment of unfiltered amniotic fluids by centrifugation also reduced IL-15 levels from 223·5 ± 25·6 pg/ml to 148·9 ± 25·6 pg/ml. These data indicate that the apparent IL-15 levels of unfiltered amniotic fluid detected by the IL-15-specific ELISA reflect non-specific activity of amniotic fluid.

Table 2.

Amniotic fluid lacks specific IL-15 immunoactivity

| ELISA conditions* | Equivalent IL-15 levels (pg/ml) |

|---|---|

| Anti-IL-15: IL-15: anti-IL-15 | 250 |

| Anti-IL-15: AF†: anti-IL-15 | 145·9 |

| Anti-IL-15: IL-2: anti-IL-15 | not defined‡ |

| Anti-IL-15: IL-4: anti-IL-15 | not defined |

| Anti-IL-15: IL-6: anti-IL-15 | 2·7 |

| Anti-IL-6: IL-15: anti-IL-15 | not defined |

| Anti-IL-6: AF: anti-IL-15 | 92·2 |

| IgG: AF: anti-IL-15 | 288·6 |

| Anti-IL-6: IL-6: anti-IL-6 | 275 |

| Anti-IL-6: IL-15: anti-IL-6 | 1·9 |

| Anti-IL-6: IL-2: anti-IL-6 | not defined |

| Anti-IL-6: AF: anti-IL-6 | 7·3 |

ELISA conditions are given as capture antibody: sample: detection antibody

amniotic fluid

below the limit of detection.

Table 3.

Amniotic fluids pretreated with mouse IgG display reduced IL-15 immunoactivity (pg/ml)

| Amniotic fluid* | Control | IgG-treated |

|---|---|---|

| Exp. 1† | ||

| Unfiltered | 205·4 ± 34·4 | 125·7 ± 38·6 |

| Filtered | 100·4 ± 31·1 | 50·0 ± 2·6 |

| Exp. 2‡ | ||

| Unfiltered | 168·2 ± 60·3 | 15·1 ± 4·4 |

| Filtered | 68·1 ± 10 | 8·4 ± 1·1 |

Seven amniotic fluids were pretreated with mouse IgG

pretreated with 100 ng/ml mouse IgG

pretreated with 500 ng/ml mouse IgG.

Discussion

The present study has clarified the previous conflicting and confusing reports on the IL-2 status of amniotic fluid during normal pregnancy.14,16–23 Although mid-trimester amniotic fluid from normally progressing uncomplicated pregnancies possesses the capacity to induce CTLL-2 proliferation, this is not due to any IL-2 bioactivity. The ability of amniotic fluid to induce CTLL-2 proliferation proved to be critically dependent on serum-free culture conditions. It is highly probable that the reported ability of amniotic fluid at term to induce HT-2 cell proliferation17 is also unrelated to IL-2 bioactivity. Moreover, the present finding that amniotic fluid induced CTLL-2 proliferation in a dose-dependent manner provides no support for the presence of IL-2 inhibitory factors in amniotic fluid.17,18 For the first time, neutralizing anti-IL-2 antibodies were used to check the specificity of amniotic fluid-induced CTLL-2 proliferation. The failure of anti-IL-2 antibodies to inhibit amniotic fluid-induced CTLL proliferation together with the failure to detect immunoactive IL-2 using ELISAs provides unequivocal evidence that mid-trimester human amniotic fluid lacks IL-2. Moreover, it is highly unlikely that the present failure to detect IL-2 by ELISA is due to amniotic fluid-mediated denaturation of the IL-2 pair of matched antibodies since ELISA sensitivity to detect rhIL-2 diluted in amniotic fluid was unimpaired. A possible explanation for the detection of IL-2 in amniotic fluid using ELISA by others14,18 might be the specificity and/or cross-reactivity of their ELISA kits as well as the presence of non-specific binding factors in amniotic fluid.

The absence of IL-2, a Th1-type inflammatory cytokine, in mid-trimester amniotic fluid is in agreement with recent studies that IL-2 mRNA and peptide are not produced in the utero–placental region.28,29 This absence of IL-2 is likely to benefit fetal survival since IL-2 administered to mice causes abortion30 and IL-2-activated endometrial granulated lymphocytes can lyse human trophoblast in vitro.31 IL-2 has been reported in amniotic fluid during preterm labour with intrauterine infection.22 IL-15, however, shares biological activities and receptor components with IL-2 (including the ability to induce CTLL-2 proliferation) and IL-15 mRNA is present in the placenta and fetal membranes at high levels.24,27 The present failure of neutralizing anti-IL-15 antibodies to block amniotic fluid-induced CTLL-2 proliferation and the lack of specific IL-15 reactivity demonstrable by ELISA suggest that mid-trimester amniotic fluid is devoid of IL-15 activity.

Although other workers have recently reported the presence of IL-15 in normal and preterm labour amniotic fluid using ELISA, no specificity studies were undertaken.27 In the present study specificity studies confirmed that the IL-15 ELISA is specific for human IL-15 but substitution of the IL-15 capture antibody with either mouse IgG or third-party antibody resulted in ELISA positivity when amniotic fluid samples were assayed. This lack of specificity may reflect the presence of a non-specific factor in amniotic fluid binding to the Fc of immunoglobulins; this was further strengthened by the lack of ELISA immunoactivity of amniotic fluid pretreated with IgG. The presence of high molecular weight human decidua-associated rheumatoid factors in amniotic fluid binding the Fc of immunoglobulin has been described.32 Filter-sterilized amniotic fluid displayed significantly reduced ELISA positivity compared with the paired unfiltered sample but filtration had no effect on the immunoreactivity of rhIL-15, suggesting that filtration had not non-specifically absorbed the IL-15 activity of amniotic fluid. Filter-sterilization, however, may have affected other factors in amniotic fluid, such as rheumatoid factors which interacted with the paired antibodies used in the IL-15-specific ELISA. The possibility that amniotic fluid had merely denatured the anti-IL-15 antibodies was excluded by the unequivocal demonstration that in both the ELISA and CTLL-2 bioassay IL-15 antibodies diluted in amniotic fluid retained the ability to recognize rhIL-15. The lack of specific IL-15 activity in amniotic fluid despite apparent ELISA immunoactivity raises concerns for the validity of previous ELISA-based reports on amniotic fluid where the appropriate checks on specificity have not been performed.

Interestingly neutralizing anti-IL-2R β-chain antibodies inhibited amniotic fluid-induced CTLL-2 proliferation, indicating that amniotic fluid utilizes the β-chain of the IL-2R to stimulate CTLL-2 proliferation. The identity of this factor in amniotic fluid is unknown. There remains the possibility that amniotic fluid contains either a denatured form of IL-15 or isoforms of IL-15, the epitopes of which are not recognized by anti-IL-15 antibodies but are still able to mediate signal transduction via the IL-2R β-chain. The differential expression of two IL-15 mRNA isoforms in fetal membranes has been reported.27 To date, IL-15 is the only cytokine which shares the β-signalling subunit of the IL-2R with IL-2.33 Other workers, however, have reported that CTLL-2 cells are responsive to TGF-β1 and -β2 as well as to rhIL-2 and IL-15.34 We have previously reported that amniotic fluid contains TGF-β1 and-β2 bioactivity.12 It is not known whether TGF-β can utilize the β-chain of the IL-2R.

The present failure to demonstrate IL-15 as a normal constituent of amniotic fluid, however, is consistent with the consensus view that there is a bias against type 1 inflammatory cytokines within the fetal–placental unit during a successful pregnancy.3 Moreover, the absence of IL-15 is supported by the inability of amniotic fluid to promote the enhanced cytotoxic activity of lymphokine-activated NK cells (Bromage and Searle, unpublished) unlike IL-15.35 The lack of detectable IL-15 peptide in amniotic fluid despite the abundance of IL-15 mRNA in placental and fetal tissues24,27 confirms that IL-15 peptide production is restricted to human bone marrow stromal cells, monocytes and dendritic cells36–38 even though IL-15 mRNA has a widespread tissue distribution.24 IFN-γ, a type 1 inflammatory cytokine, is also not detectable in mid-trimester amniotic fluids (Bromage and Searle, unpublished) although other workers have reported that IFN-γ is present at term in the amniotic fluid of women in spontaneous labour and in non-labouring women undergoing elective caesarean11 and is elevated in women with preterm labour and premature rupture of membranes.19 The absence of IL-2, IL-15 and IFN-γ during gestation of normally progressing uncomplicated pregnancies strengthens the hypothesis that the cytokine profile in a successful pregnancy is primed for the production of T helper type 2 cytokines as well as co-stimulatory monokines, thereby activating the innate immune system to distinguish the pregnant state from the non-pregnant state and allowing maternal adaptation to pregnancy.39

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr J Wolstenholme (Department of Human Genetics, Newcastle University) for providing amniotic fluids.

References

- 1.Tabibzadeh S. Cytokines and the hypothalamic-pituitary-ovarian axis. Hum Reprod. 1994;9:947. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.humrep.a138621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wegmann TF, Lin H, Guilbert L, Mosmann TR. Bidirectional cytokine interactions in the maternal–fetal relationship: is successful pregnancy a Th2 phenomenon? Immunol Today. 1993;14:353. doi: 10.1016/0167-5699(93)90235-D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Raghupathy R. Th1-type immunity is incompatible with successful pregnancy. Immunol Today. 1997;18:478. doi: 10.1016/s0167-5699(97)01127-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Guilbert LJ. There is a bias against type 1 (inflammatory) cytokine expression and function in pregnancy. J Reprod Immunol. 1996;32:105. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0378(96)00996-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tsunoda H, Tamatani T, Oomoto Y, et al. Changes in interleukin 1 levels in human amniotic fluid with gestational ages and delivery. Microbiol Immunol. 1990;34:377. doi: 10.1111/j.1348-0421.1990.tb01018.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Santhanam U, Avila C, Romero R, et al. Cytokines in normal and abnormal parturition: elevated amniotic fluid interleukin-6 levels in women with premature rupture of membranes associated with intrauterine infection. Cytokine. 1991;3:155. doi: 10.1016/1043-4666(91)90037-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Opsjln S-L, Wathen NC, Tingulstad S, et al. Tumour necrosis factor, interleukin-1, and interleukin-6 in normal human pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1993;169:397. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(93)90096-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Saito S, Kasahara T, Kato Y, Ishihara Y, Ichijo M. Elevation of amniotic fluid interleukin 6 (IL-6), IL-8 and granulocyte colony stimulating factor (G-CSF) in term and preterm parturition. Cytokine. 1993;5:81. doi: 10.1016/1043-4666(93)90027-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Greig PC, Herbert WN, Robinette BL, Teot LA. Low amniotic fluid glucose levels are a specific but not a sensitive marker for subclinical intrauterine infections in patients in preterm labour with intact membranes. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1995;173:1223. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(94)70036-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yoon BH, Romero R, Kim CJ, et al. Amniotic fluid interleukin-6: a sensitive test for antenatal diagnosis of acute inflammatory lesions of preterm placenta and prediction of perinatal morbidity. Am J Obst Gynecol. 1995;172:960. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(95)90028-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Oláh KS, Vince GS, Neilson JP, Deniz G, Johnson PM. Interleukin-6, interferon-gamma, interleukin-8, and granulocyte-macrophage colony stimulating factor levels in human amniotic fluid at term. J Reprod Immunol. 1996;32:89. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0378(96)00990-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lang AK, Searle RF. The immunomodulatory activity of human amniotic fluid can be correlated with transforming growth factor-beta 1 and beta 2 activity. Clin Exp Immunol. 1994;97:158. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.1994.tb06595.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Weimann E, Reisbach G, Reinsberg T, Lentze MJ. IL-6 and G-CSF levels in amniotic fluid during the second trimester in normal and abnormal pregnancies. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 1995;256:125. doi: 10.1007/BF01314640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shohat B, Faktor JM, Barkay G, et al. Soluble interleukin-2 receptor and interleukin-2 in human amniotic fluid of normal and abnormal pregnancies. Biol Neonat. 1993;6:281. doi: 10.1159/000243942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chaouat G, Menu E, Clark DA, Dy M, Minkowski M, Wegmann TG. Control of fetal survival in CBA × DBA/2 mice by lymphokine therapy. J Reprod Fertil. 1990;89:447. doi: 10.1530/jrf.0.0890447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Romero R, Brody DT, Oyarzun E, et al. Infection and labour: IL-1: a signal for the onset of parturition. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1989;160:1117. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(89)90172-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Halgunset J, Johnsen H, Kjollesdal AM, Qvigstad E, Espevik T, Austgulen R. Cytokine levels in amniotic fluid and inflammatory changes in the placenta from normal deliveries at term. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 1996;56:153. doi: 10.1016/0028-2243(94)90162-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zicari A, Ticconi C, Pasetto N, et al. Interleukin-2 in human amniotic fluid during pregnancy and parturition: implications for prostaglandin E2 release by fetal membranes. J Reprod Immunol. 1995;29:197. doi: 10.1016/0165-0378(95)00945-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hampl M, Friese K, Pracht I, Zieger W, Weigel M, Gallati H. Determination of cytokines and cytokine receptors in premature labour. Geburtsh Frauenheilk. 1995;55:483. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-1022825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dudley DJ, Hunter C, Varner MW, Mitchell MD. Elevation of amniotic fluid interleukin-4 concentrations in women with preterm labour and chorioammionitis. Am J Perinatol. 1996;13:443. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-994385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Negishi H, Yamada H, Mikuni M, et al. Correlation between cytokine levels of amniotic fluid and histological chorioamnionitis in preterm delivery. J Perinat Med. 1996;24:633. doi: 10.1515/jpme.1996.24.6.633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ohno Y, Kasugai M, Kurauchi O, Mizutani S, Tomoda Y. Effect of interleukin 2 on the production of progesterone and prostaglandin E2 in human fetal membranes and its consequences for preterm uterine contractions. Eur J Endocrinol. 1994;130:478. doi: 10.1530/eje.0.1300478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Srivastava MD, Lippes J, Srivastava BI. Cytokines of the human reproductive tract. Am J Reprod Immunol. 1996;36:157. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0897.1996.tb00157.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Grabstein KH, Gisenman J, Shanebeck K, et al. Cloning of a T cell growth factor that interacts with the beta chain of the interleukin-2 receptor. Science. 1994;264:965. doi: 10.1126/science.8178155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Armitatage RJ, MacDuff BM, Eisenman J, Paxton R, Grabstein KH. IL-15 has stimulatory activity for the induction of B cell proliferation and differentiation. J Immunol. 1995;154:483. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.McInnes IB, al-mughales J, Field M, et al. The role of interleukin-15 in T-cell migration and activation in rheumatoid arthritis. Nat Med. 1996;2:175. doi: 10.1038/nm0296-175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fortunato SJ, Menon R, Lombardi SJ. IL-15, a novel cytokine produced by human fetal membranes, is elevated in preterm labour. Am J Reprod Immunol. 1998;39:16. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0897.1998.tb00328.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jokhi PP, King A, Sharkey AM, Smith SK, Loke YW. Screening for cytokine messenger ribonucleic acids in purified human decidual lymphocyte populations by the reverse-transcriptase polymerase chain reaction. J Immunol. 1994;153:4427. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.King A, Jokhi PP, Smith SK, Sharkey AM, Loke YW. Screening for cytokine mRNA in human villous and extravillous trophoblasts using the reverse-transcriptase polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) Cytokine. 1995;7:364. doi: 10.1006/cyto.1995.0046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tezabwala BU, Johnson PM, Rees RC. Inhibition of pregnancy viability in mice following IL-2 administration. Immunology. 1989;67:115. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.King A, Loke YW. Human trophoblast and JEG choriocarcinoma cells are sensitive to lysis by IL-2-stimulated decidual NK cells. Cell Immunol. 1990;129:435. doi: 10.1016/0008-8749(90)90219-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Halperin R, Schneider D, Kraicer PF, Hadas E. Rheumatoid factor-associated high-molecular-weight complexes in the menstrual and amniotic fluids. Gynecol Obstet Invest. 1996;41:220. doi: 10.1159/000292272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Giri JG, Ahdieh M, Eisenmen J, et al. Utilisation of the β and γ chains of the IL-2 receptor by the novel cytokine IL-15. EMBO J. 1994;13:2822. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1994.tb06576.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mire-sluis AR, Page L, Thorpe R. Quantitative cell line based bioassays for human cytokines. J Immunol Methods. 1995;187:191. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(95)00220-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Carson WE, Giri JG, Lindemann J, et al. Interleukin (IL) -15 is a novel cytokine that activates human natural killer cells via components of the IL-2 receptor. J Exp Med. 1994;180:1395. doi: 10.1084/jem.180.4.1395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jonuleit H, Wiedemann K, Muller G, et al. Induction of IL-15 messenger RNA and protein in human blood-derived dendritic cells: a role for IL-15 in attraction of T cells. J Immunol. 1997;158:2610. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Carson WE, Ross ME, Baiochhi RA, et al. Endogenous production of interleukin 15 by activated human monocytes is critical for optimal production of interferon-gamma by natural killer cells in vitro. J Clin Invest. 1995;96:2578. doi: 10.1172/JCI118321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mrozek E, Anderson P, Caligiura MA. Role of interleukin-15 in the development of human CD56+ natural killer cells from CD34+ haematopoietic progenitor cells. Blood. 1996;87:2632. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sacks G, Sargent I, Redman C. An innate view of human pregnancy. Immunol Today. 1999;20:114. doi: 10.1016/s0167-5699(98)01393-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]