Abstract

The physiological changes that sperm undergo in the female reproductive tract rendering them fertilization-competent constitute the phenomenon of capacitation. Cholesterol efflux from the sperm surface and protein kinase A (PKA)-dependent phosphorylation play major regulatory roles in capacitation, but the link between these two phenomena is unknown. We report that apolipoprotein A-I binding protein (AI-BP) is phosphorylated downstream to PKA activation, localizes to both sperm head and tail domains, and is released from the sperm into the media during in vitro capacitation. AI-BP interacts with apolipoprotein A-I, the component of high-density lipoprotein involved in cholesterol transport. The crystal structure demonstrates that the subunit of the AI-BP homodimer has a Rossmann-like fold. The protein surface has a large two compartment cavity lined with conserved residues. This cavity is likely to constitute an active site, suggesting that AI-BP functions as an enzyme. The presence of AI-BP in sperm, its phosphorylation by PKA, and its release during capacitation suggest that AI-BP plays an important role in capacitation possibly providing a link between protein phosphorylation and cholesterol efflux.

FRESHLY EJACULATED SPERM are unable to fertilize an oocyte, and they require residence for a finite period in the female reproductive tract before they acquire the capacity to fertilize. The physiological and biochemical changes that sperm undergo in the female reproductive tract to render them fertilization competent are known as capacitation (1,2). Capacitation-associated biochemical changes include efflux of cholesterol from sperm (3), protein phosphorylation (4,5), acquisition of hyperactivated motility (6), increase in intracellular concentrations of bicarbonate and calcium (4,7,8), redistribution of sperm surface antigens (6,9), and hyperpolarization of the plasma membrane (10,11). Because sperm are terminally differentiated cells, posttranslational modifications such as phosphorylation/dephosphorylation are thought to be major regulatory mechanisms during capacitation. The identification and characterization of phosphoprotein substrates are keys to elucidating the signaling cascades that operate during the capacitation process. The role of protein kinase A (PKA) in sperm capacitation has been especially well established, and this has been further highlighted by two recent reports. First, sperm from mice that lack soluble adenylyl cyclase do not show an increase in capacitation-associated tyrosine phosphorylation (12,13). Second, sperm from mice that lack C2α, a testis-specific PKA catalytic subunit, do not show active motility or an increase in capacitation-associated tyrosine phosphorylation (14). Hence, identification and characterization of sperm proteins that are phosphorylated downstream to PKA will aid in understanding the molecular basis of capacitation.

Cholesterol efflux from the sperm plasma membrane is a major initiator of capacitation and is brought about by BSA during capacitation in vitro (3,4). The physiological sink(s) for cholesterol efflux during capacitation is/are yet to be determined, although there is evidence that high-density lipoprotein (HDL) is involved (15,16,17,18,19). HDL has been shown to substitute for BSA in in vitro capacitation media as assayed by protein tyrosine phosphorylation and in vitro fertilization (15,20). HDL is present in oviductal and uterine fluids (17,18) and oviductal fluid shows an elevated level of HDL during the follicular phase of the estrous cycle in bovine (17). Recently the HDL and apolipoprotein A-I receptors megalin and cubulin were shown to be expressed in the uterine epithelium of rat implicating receptor-mediated endocytosis as a potential mechanism for sperm membrane remodeling within the female reproductive tract (19). Even though cholesterol efflux is a required step before capacitation can proceed, little is understood about the molecular mechanism of cholesterol efflux during capacitation. Cholesterol efflux, however, has been studied intensively and is better understood in other cell types including macrophages and fibroblasts (21,22).

Protein phosphorylation and cholesterol efflux comprise two of the most important aspects of the physiology of capacitation; recently we have shown that cholesterol efflux increased proline-directed phosphorylation in mouse sperm (23). However, little is known about the intersection of the cholesterol efflux and signal transduction pathways. Apolipoprotein A-I binding protein (AI-BP) was recently discovered as a protein that interacts with apolipoprotein A-I, a major constituent of HDL, in a yeast two-hybrid screen (24,25). When cells derived from kidney proximal tubules were stimulated with apolipoprotein A-I or HDL, AI-BP showed a concentration-dependent release into the media implicating its role in the renal tubular degradation or resorption of apolipoprotein A-I.

In the present study, we characterized AI-BP as a mouse sperm phosphoprotein that is phosphorylated downstream to PKA activation during capacitation. Northern blot analysis showed that although AI-BP mRNA was expressed in all tissues tested, it was highly abundant in certain tissues such as testis, liver, heart, and kidney. AI-BP was immunolocalized to head and tail domains in mouse sperm and was released from the sperm during in vitro capacitation. Determination of the crystal structure of AI-BP revealed a Rossmann-like fold and indicated a putative active site of an enzyme. We hypothesize that AI-BP plays an important role in capacitation possibly at the level of cholesterol efflux.

Materials and Methods

Reagents

γ32P ATP and [32P] orthophosphate were purchased from MP Biomedical (Irvine, CA). The catalytic subunit of PKA was from Promega Corp. (Madison, WI). Dibutyryladenosine cAMP (dbcAMP), isobutylmethylxanthine (IBMX), H89, and the horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies were purchased from Sigma (St. Louis, MO). Alexafluor-conjugated anti-guinea pig secondary antibody was from Molecular Probes (Eugene, OR), and the enhanced chemiluminescence kit was from PerkinElmer Life Sciences (Boston, MA). All other reagents used in the experiments were of high analytical grades.

Preparation of mouse sperm

Mice were handled and killed in accord with the guidelines of Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the University of Virginia. Caudal epididymal sperm were collected from CD1 retired breeder males (Charles River Laboratories, Wilmington, MA), and in vitro capacitation was carried out as described previously (23,26). Briefly, sperm were collected and washed in modified Krebs-Ringer medium [Whitten’s-HEPES buffered medium (WH)] (26) containing 100 mm NaCl, 4.7 mm KCl, 1.2 mm KH2PO4, 1.2 mm MgSO4, 5.5 mm glucose, 1 mm pyruvic acid, 4.8 mm L(+) lactic acid hemicalcium salt in 20 mm HEPES (pH 7.3). Sperm pellets were resuspended in WH media, and then 1–2 × 106 sperm/ml of the medium were incubated at 37 C and 5% CO2 in air. Capacitating media consisted of 5 mg/ml BSA and 10 mm NaHCO3 in WH medium. In all the cases pH was maintained at 7.3. In the experiments in which release of AI-BP into the media was studied, 2-hydroxypropyl-β-cyclodextrin at a concentration of 5 mm was used instead of BSA in the medium. To recover AI-BP released into the incubating media, the tubes were centrifuged at 800 × g for 10 min. The supernatant was filtered through a syringe filter (22 μm) to remove cellular debris (if any), and subsequently the content was concentrated using a centrifugal filter device (Millipore, Bedford, MA) with 10 kDa cutoff. The concentrated supernatant was subjected to immunoblot analysis with antibody against AI-BP. Ponceau-S staining of the blot before the immunoblotting with anti-AI-BP showed an equivalent protein content in all the lanes.

In vitro phosphorylation of sperm lysate with γ32P ATP

Eight to 10 million mouse sperm resuspended in 40 μl of PBS were added to 40 μl of 2× phosphorylation cocktail [40 mm HEPES, 10 mm MgCl2, 200 μm sodium orthovanadate, 10 mm p-nitro-phenyl-phosphate, 80 mm β-glycerophosphate, 0.2% Triton X-100, and protease inhibitors mix (pH 7.6)]. In vitro phosphorylation was conducted with 10 μCi of γ32P ATP, either in the presence or in the absence of 500 μm dbcAMP and 100 μm IBMX, for 5 min at 37 C in a water bath. A parallel set of tubes was used wherein 1 μm of cold ATP was added instead of the γ32P ATP. The reaction was stopped by adding the components of Celis buffer [9.8 m urea, 2% (wt/vol) Nonidet P-40, 2% (vol/vol) ampholine (pH 3.5–10), 100 mm dithiothreitol, and protease inhibitors]. The cells were solubilized by constant shaking at 4 C for 60 min, and insoluble material was removed by centrifugation at 10,000 × g for 5 min. The supernatant was subjected to two-dimensional gel electrophoresis, silver stained, and the gels carrying γ32P ATP were dried and exposed to the x-ray film to develop autoradiograms.

Two-dimensional gel electrophoresis

Mouse sperm proteins were extracted in Celis extraction buffer containing protease inhibitors (Roche, Mannheim, Germany) and resolved by two-dimensional gel electrophoresis as described previously (23,27). Proteins were subjected to isoelectric focusing either in polyacrylamide tube gels or ReadyStrip IPG (immobilized pH gradient) strips (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA). The isoelectric focusing tube gels/IPG strips were then loaded on the second dimensional SDS-PAGE gels. For autoradiography the gels were silver stained as described previously (27) and dried before exposing them to either phosphor imager screen (Molecular Dynamics, Sunnyvale, CA) or the x-ray film. For developing immunoblots the proteins were transferred onto nitrocellulose or polyvinyl difluoride membranes.

Tandem mass spectrometric analysis of phosphoprotein spots

The silver-stained proteins corresponding to phosphorylated protein spots were cored from two-dimensional SDS-PAGE gels, fragmented into smaller pieces, destained in methanol, reduced in 10 mm dithiothreitol, and alkylated in 50 mm iodoacetamide in 0.1 m ammonium bicarbonate. The gel pieces were then incubated with 12.5 ng/ml trypsin in 50 mm ammonium bicarbonate overnight at 37 C. Peptides were extracted from the gel pieces in 50% acetonitrile and 5% formic acid and microsequenced by tandem mass spectrometry at the Biomolecular Research Facility of the University of Virginia.

Determining phosphorylation sites on AI-BP by mass spectrometric analysis

Purified recombinant AI-BP was phosphorylated with PKA catalytic subunit using cold ATP in the phosphorylation buffer [25 mm HEPES (pH 7.6), 10 mm MgCl2, protease inhibitors mix (without EDTA), 100 μm Na3VO4, 5 mm p-nitrophenyl phosphate, 40 mm β-glycerophosphate, 1% Triton X-100, and 1 mg/ml BSA]. The phosphorylation was followed by resolving AI-BP on SDS-PAGE gels and silver staining. The AI-BP band was cut out from the silver-stained gel and submitted for phospho-mapping by mass spectrometric analysis at the Biomolecular Research Facility of the University of Virginia.

Cloning and expression of AI-BP from murine testis cDNA library

Two gene-specific primers (forward, 5′-AGTCCCCCGACTGTCTTGG-3′; and reverse, 5′-CTGTAAACGGTAGACACACTC-3′) designed on the basis of the nucleotide database (National Center for Biotechnology Information, Bethesda, MD) were used to PCR amplify the full-length AI-BP from a mouse testis cDNA library (BD Biosciences CLONTECH, Palo Alto, CA). PCR products were separated on agarose gels, and bands of expected molecular sizes were gel eluted and subcloned in pCR2.1 TOPO vector (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). Multiple cDNA clones were sequenced in both directions using vector-derived primers on a PerkinElmer Applied Biosystems DNA sequencer. The final cDNA sequence was submitted to GenBank (accession no. AY566271). For the expression of AI-BP, gene-specific forward (5′-GGAATTCCATATGCAGCAGAGTGTGTGTCGT-3′) and reverse primers (5′-CCGCTCGAGCTGTAAACGGTAGACACA-3′) with NdeI and XhoI restriction sites respectively were designed to amplify the mature form of AI-BP lacking the signal peptide from the mouse testis cDNA library. PCR products were separated on agarose gels, and a band of approximately 800 bp was isolated and subcloned in pCR2.1 TOPO vector. After confirming the sequence, the insert was restriction digested, gel purified, ligated into the predigested pET21a(+) vector, and used to transform competent BL21DE3 cells (Invitrogen). The final construct added one amino acid (methionine) at the N terminus and six histidine residues at the C terminus. The bacterial cultures from single colonies were grown to OD of 0.8 at 600 nm at 37 C in Luria broth in the presence of 50 μg/ml ampicillin. Isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) (Sigma) was then added to a final concentration of 1 mm to induce expression. After 3 h of induction, the bacteria were collected by centrifugation. The bacterial pellet was extracted in Bugbuster protein extraction reagent (Novagen, Darmstadt, Germany) containing benzonase nuclease (Novagen), chicken lysozyme (Sigma), and a protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche). The cell extract was centrifuged at 15, 000 × g, and the recombinant protein was purified from the supernatant on a His binding Ni2+ chelation affinity resin column following the instructions from the manufacturer (Novagen). This was followed by Prep Cell (Bio-Rad) isolation to homogeneity, and subsequently the eluates were dialyzed overnight against three changes of PBS. The dialyzed protein was stored at −80 C until used.

Generation of antibody against AI-BP

Two different polyclonal antibodies against AI-BP were used in the present studies. The first antibody was raised in guinea pigs against the purified recombinant AI-BP polypeptide. The purified AI-BP recombinant protein was homogenized in PBS and emulsified with an equal volume of complete Freund’s adjuvant. Approximately 30 μg of the affinity- and Prep Cell-purified recombinant protein were injected sc and im in each guinea pig. Control animals were injected with Freund’s adjuvant alone. Animals were boosted three times at intervals of 14 d with 30 μg of the recombinant protein in incomplete Freund’s adjuvant, and serum was collected 7 d after each boost. The guinea pigs were killed according to the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee guidelines of the University of Virginia to collect the antiserum. The second antibody used in the study was generated in rabbits with a peptide (VPPALEKKYQLNLPPYPDTE) corresponding to amino acids 263–282 of the AI-BP protein (24).

Northern blot analysis

A Northern blot containing 2 μg of poly (A)+ RNA from eight selected mouse tissues (BD Biosciences) was probed with 32P-labeled DNA containing nucleotides 306–908 of murine AI-BP. The probe was prepared by random oligonucleotide primer labeling (28) using a random primers DNA labeling kit (Invitrogen). Hybridization was performed in ExpressHyb solution (BD Biosciences CLONTECH) at 68 C for 2 h, followed by three washes each for 40 min in 2× saline sodium citrate and 0.05% sodium dodecyl sulfate at room temperature, and two washes in 0.1× saline sodium citrate and 0.1% sodium dodecyl sulfate for 40 min at 50 C. The blot was exposed to a phosphor imaging screen overnight or longer. Equal loading of RNA was checked by stripping and then reprobing the same blot with a β-actin probe.

SDS-PAGE and immunoblotting

Sperm proteins were extracted in Laemmli sample buffer (29) and subjected to SDS-PAGE as described earlier (23). Proteins were transferred to either nitrocellulose or polyvinyl difluoride membranes and incubated in blocking solution [5% nonfat milk in PBS and 0.05% Tween 20 (PBS-T)] for 1 h at room temperature. After the blocking step, the membrane was incubated with anti AI-BP antibody (1:1000 dilution in PBS-T containing 5% nonfat milk) for 1 h at the room temperature. After incubation in the primary antibody, the membrane was washed with PBS-T for 45 min with changes of wash buffer every 15 min. Protein detection was accomplished by incubating membranes with the appropriate horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies (1:10,000) diluted in PBS-T containing 5% nonfat milk followed by enhanced chemiluminescence (enhanced chemiluminescence kit; Amersham Biosciences, Piscataway, NJ) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Phosphotyrosine proteins were detected using anti-phosphotyrosine antibody (4G10 clone; Upstate, Lake Placid, NY) as described previously (23), and the histidine tagged recombinant AI-BP was detected using nickel-NTA (nitriloacetic acid) antibody.

Indirect immunofluorescence

Mouse sperm were air dried on slides, fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS for 20 min at room temperature, and washed with PBS (four washes for 5 min each). After fixation the sperm were permeabilized with ice-cold methanol for 7 min, washed with PBS (four washes each for 5 min) and blocked with 10% normal goat serum in PBS for 30 min at room temperature. Sperm were then incubated with guinea pig antiserum against AI-BP diluted (1:25) in PBS containing 1% normal goat serum for 1 h at room temperature. After the primary antibody incubation, the sperm were washed with PBS (four washes) and incubated with Alexafluor-conjugated anti-guinea pig secondary antibody diluted (1:200) in 1% normal goat serum in PBS for 1 h at room temperature. The secondary antibody treatment was followed by four washes in PBS, treatment with Slow-Fade Light (Molecular Probes), and observation by phase-contrast and epifluorescence microscopy using an Axiophot microscope (Carl Zeiss, Inc., Thornwood, NY). Controls included preimmune serum and secondary antibody alone.

Immunoprecipitation of AI-BP

Fifty to 60 million mouse sperm were solubilized in 1 ml of Nonidet P-40 lysis buffer [150 mm NaCl, 50 mm Tris, and 1% Triton X-100 (pH 8.0)] at 4 C for 30 min. The suspension was centrifuged at 15,000 × g, and the supernatant was incubated with antibody against AI-BP (1:100) for 2 h at 4 C. Protein A Sepharose (5 mg/ml) was added and the tubes were further incubated for 2 h. The immunoprecipitate was pelleted at 15,000 × g, and the beads were washed three times with PBS. The washed complex was resuspended in 100 μl of PBS. The presence of AI-BP in the immunoprecipitated complex was confirmed by Western blot.

In vitro phosphorylation of immunoprecipitated AI-BP with PKA catalytic subunit

The immunoprecipitated AI-BP and the purified PKA catalytic subunit were mixed in the phosphorylation buffer containing 25 mm HEPES (pH 7.6), 10 mm MgCl2, protease inhibitor mix (without EDTA), 100 μm Na3VO4, 5 mm p-nitrophenyl phosphate, 40 mm β-glycerophosphate, 2 μCi γ32P ATP, 1% Triton X-100, and 1 mg/ml BSA, and the mix was incubated at 37 C for 5 min. AI-BP alone and PKA alone controls were also included in the experiments. In addition, the phosphorylation was also carried out in the presence of 10 μm H89, a specific inhibitor of PKA. The phosphorylation assay was stopped by adding Laemmli sample buffer (29), and 32P incorporation was analyzed by SDS-PAGE followed by autoradiography.

In vivo phosphorylation

To obtain the highest possible specific activity of radioactive phosphate during the labeling period the concentration of the cold phosphate (KH2PO4) was reduced to 0.2 mm from the normal level of 1.2 mm in the WH media. The sperm motility was normal in the media with 0.2 mm KH2PO4. Caudal sperm were collected and washed in this media, and 10–15 × 106 sperm were incubated with 0.5 mCi/ml of [32P] orthophosphate in the medium. The intracellular ATP was equilibrated with the [32P] orthophosphate for 30 min at 37 C. At the end of this equilibration period, capacitation was induced by adding BSA (final concentration 5 mg/ml) and NaHCO3 (final concentration 15 mm) in the medium. For noncapacitated samples, neither BSA nor NaHCO3 was added. To inhibit PKA, H89 (90 μm) was added along with BSA and NaHCO3. The sperm were further incubated for 1 h at 37 C and 5% CO2 in air. After incubation the sperm were pelleted, washed with PBS containing 1 mm sodium orthovanadate, and total proteins were extracted in Celis buffer as described before. The proteins were subjected to two-dimensional gel electrophoresis. The gels were silver stained, dried, and then exposed to phosphor imager screen to develop autoradiograms. Resolved proteins on companion two-dimensional gels were electrotransferred to membranes and immunoblotted with antibody against AI-BP to locate the exact position of AI-BP in the silver-stained gels and in the autoradiograms.

Preparation and crystallization of selenomethionine-substituted AI-BP

The selenomethionine (SeMet)-substituted mature AI-BP containing an additional N-terminal Met and C-terminal (His)6-tag was used for structure determination. A culture of the AI-BP-expressing Escherichia coli BL21DE3 was grown overnight in Luria broth media. The cells were resuspended in M9 media and incubated at 37 C. When OD600 reached 0.3, the temperature was decreased to 15 C, and amino acid supplements (100 mg/liter of Lys and Thr; 50 mg/liter of Ile, Leu, Val, and SeMet) were added. After 15 min, AI-BP overexpression was induced with 1 mm IPTG, and the cell culture was grown for additional 16 h. The cells were lysed by sonication in binding buffer [500 mm NaCl, 5% glycerol, 50 mm HEPES (pH 7.5)] with addition of 0.5% nonionic detergent Igepal CA-630 (Sigma) and 1 mm each of phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride and benzamidine. The lysate was clarified by centrifugation and passed through a DE52 (Whatman, Middlesex, UK) column preequilibrated in binding buffer. The flow-through fraction was applied to a Ni-NTA agarose (QIAGEN, Valencia, CA) column and washed extensively. AI-BP was eluted with 500 mm NaCl, 5% glycerol, 250 mm imidazole, and 50 mm HEPES (pH 7.5). The eluted protein was concentrated and applied to a Superdex-200 gel filtration column (Pharmacia, Uppsala, Sweden). Dimeric and tetrameric peaks of AI-BP were collected separately and used for crystallization trials.

Crystals of SeMet-substituted AI-BP were grown using the hanging drop vapor diffusion method at 21 C. The optimization of crystallization conditions performed with Xtaldb database (unpublished work) led to conditions that produced two crystal forms. In both cases the drop was composed of 2 μl of 10 mg/ml solution of protein and 1 μl of crystallization buffer that contained 1.5 m ammonium sulfate and 0.1 m sodium acetate (pH 4.6). Similar crystals were produced from dimeric and tetrameric gel filtration fractions of AI-BP. Before freezing in liquid nitrogen, the AI-BP crystals were cryoprotected in crystallization buffer containing 30% (vol/vol) PEG 400 (Fluka, Buchs, Switzerland).

Data collection, structure solution, and refinement

The structure of SeMet-substituted AI-BP was determined by the single-wavelength anomalous dispersion (SAD) technique using 0.9793 Å wavelength. The data were collected at the Structural Biology Center 19ID beamline (31) at Argonne National Laboratory (Argonne, IL). The crystal that belonged to the space group R32 with unit cell dimensions a = b = 124.3 Å, c = 120.7 Å diffracted to 2.0 Å resolution and had one subunit of AI-BP in the asymmetric unit and 60% of solvent. The crystal that belonged to the space group C2 with unit cell dimensions a = 104.9 Å, b = 125.7 Å, c = 163.6 Å, β = 106.6° diffracted to 2.5 Å resolution. It contained six AI-BP subunits per asymmetric unit and 58% solvent. The diffraction data were processed with HKL-2000 (32). The solvability of the structure was checked during data collection with HKL-3000 (33), a software package that interacts with SHELXD (34), SHELXE (35), MLPHARE (36), DM (37), O (38), CCP4 (39), SOLVE/RESOLVE (40), and ARP/wARP (41). HKL-3000 was also used to solve the AI-BP structure and build the initial model. The model was rebuilt with multicycle iterative procedure combining manual rebuilding with COOT (42) and refinement with REFMAC5 (43). The search for bound water molecules was done with ARP/wARP. Data collection and refinement statistics are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Data collection and refinement statistics for mouse AI-BP

| Data collection | ||

| Space group | R32 | C2 |

| Unit cell | a = b = 124.3 Å, c = 120.7 Å | a = 104.9 Å, b = 125.7 Å, c = 163.6 Å, ß = 106.6° |

| Resolution, Å | 80.0–1.9 | 80.0–2.45 |

| Unique reflections, n | 28188 | 74791 |

| Completeness, % | 99.9 (100.0)a | 98.8 (98.6)a |

| Multiplicity | 8.1 (8.1)a | 4.4 (4.5)a |

| I/σ (I) | 40.1 (4.0)a | 20.9 (2.2)a |

| Rmerge, % | 7.4 (47.8)a | 8.0 (49.1)a |

| Outermost shell | 1.97–1.90 | 2.54–2.45 |

| Phasing | ||

| Anomalous Rcullis | 0.69 | 0.76 |

| Figure of merit (MLPHARE/DM) | 0.31/0.88 | 0.24/0.67 |

| Refinement | ||

| Rwork/Rfree, % | 15.1/18.9 | 19.7/21.9 |

| rmsd for bond length, Å | 0.015 | 0.020 |

| rmsd for bond angles, degrees | 1.34 | 1.77 |

| Average B factor for protein atoms, Å2 | 19.7 | 43.8 |

| Test set, % | 5.0 | 5.0 |

Values in the outermost resolution shell.

The models of AI-BP in R32 and C2 crystal forms were refined to R/Rfree = 15.1%/18.9% at 1.9 Å resolution and R/Rfree = 19.7%/21.9% at 2.45 Å resolution, respectively. No electron density is observed for the N-terminal segment (residues 1–25 of the mature form of AI-BP) and C-terminal (His)6-tag in either crystal form. Both models represent similarly high structure quality. They have good stereochemistry as validated with SFCHECK (44), ADIT (45), MOLPROBITY, and KING (46). The coordinates and structure factors are deposited in the RSCB Protein Data Bank with accession codes 2O8N and 2DG2.

Results

Identification of AI-BP as a phosphoprotein in mouse sperm

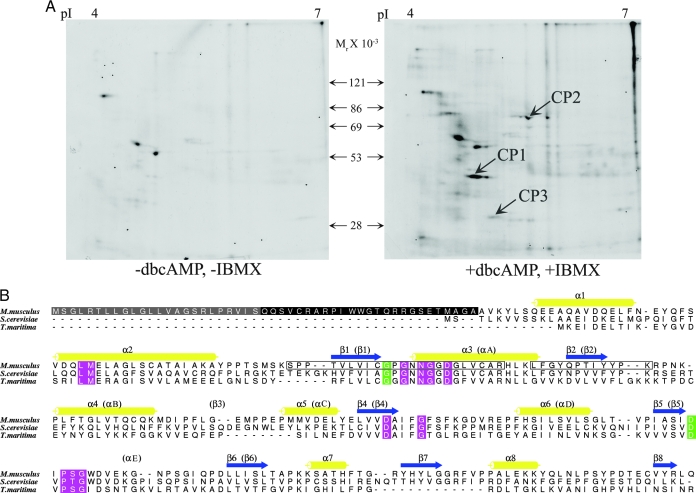

In almost all mammalian species, capacitation is associated with activation of PKA and increased protein tyrosine phosphorylation. At present only a few of the protein substrates phosphorylated during capacitation are known. To identify proteins that are phosphorylated downstream to PKA activation during capacitation, mouse sperm lysates were phosphorylated in vitro using γ32P ATP, in either the presence or absence of dbcAMP and IBMX, an inhibitor of the enzyme phosphodiesterase. Two-dimensional gel electrophoresis of the proteins followed by autoradiography indicated that multiple proteins underwent increased phosphorylation in the presence of dbcAMP and IBMX (Fig. 1A). Three such phosphoproteins, designated CP1, CP2, and CP3, were cored from a companion two-dimensional silver-stained gel and digested with trypsin, and the resulting peptides were submitted for tandem mass spectrometry analysis. The peptides obtained from the phosphoproteins CP1 and CP2 identified these spots as the RII subunit of PKA and glycerol-3-phosphate-dehydrogenase, respectively. Two peptides from the CP3 protein (SPPTVLVICGPGNNGGDGLVCAR and LFGYEPTIYYPK) belonged to a recently identified protein, AI-BP, thus identifying AI-BP as a novel phosphoprotein from sperm.

Figure 1.

A, Autoradiograms of two-dimensional gels after in vitro phosphorylation of mouse sperm lysates with γ32P ATP in either the absence (left panel) or presence (right panel) of exogenous dbcAMP and IBMX demonstrating increase in signals of several proteins that are phosphorylated downstream to PKA activation. B, Sequence alignment of mouse AI-BP and its homologs with known crystal structures, YNL200C from S. cerevisiae (PDB: 1JZT) and tm0922 protein from T. maritima (PDB: 2AX3). The invariant and conserved residues among 387 eukaryotic, bacterial, and archaeal homologs present in Pfam database are colored in green and magenta, respectively. The secondary structure of AI-BP is shown with the corresponding conventional segments of the Rossmann-fold labeled in parentheses. The signal peptide and disordered N-terminal segment present only in mammalian homologs are in gray and black, respectively. Two peptides that identified AI-BP in mass spectrometric analysis are shown in boxes. The figure was drawn with ALSCRIPT (69).

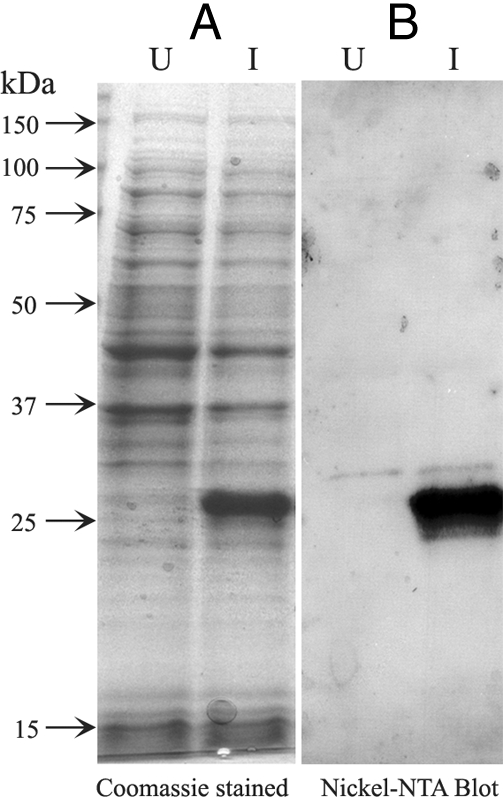

Cloning and expression of mouse testicular AI-BP cDNA in E. coli

AI-BP cDNA was amplified from an adaptor ligated murine testicular cDNA library. The AI-BP open reading frame encodes a 282-amino acid protein containing a signal peptide with the cleavage site located between amino acids 24 and 25 (VIS-QQ) (Fig. 1B). The recombinant mature mouse AI-BP corresponding to amino acids 25–282 carrying a C-terminal His6-tag was expressed in E. coli (Fig. 2). Upon induction with IPTG, the recombinant protein at the expected molecular mass stained both with Coomassie and for the presence of the histidine tag (Fig. 2). The recombinant AI-BP protein was purified with a nickel column followed by Prep Cell isolation to homogeneity and was subsequently used to immunize guinea pigs.

Figure 2.

Expression of recombinant AI-BP. A, Coomassie blue stain of lysed bacterial proteins from uninduced (U) and induced (I) cultures containing recombinant AI-BP expression constructs. B, Western blot of uninduced (U) and induced (I) bacterial protein lysates using anti-nickel NTA antibody, demonstrating recombinant AI-BP at the expected molecular mass of 29 kDa only in induced culture.

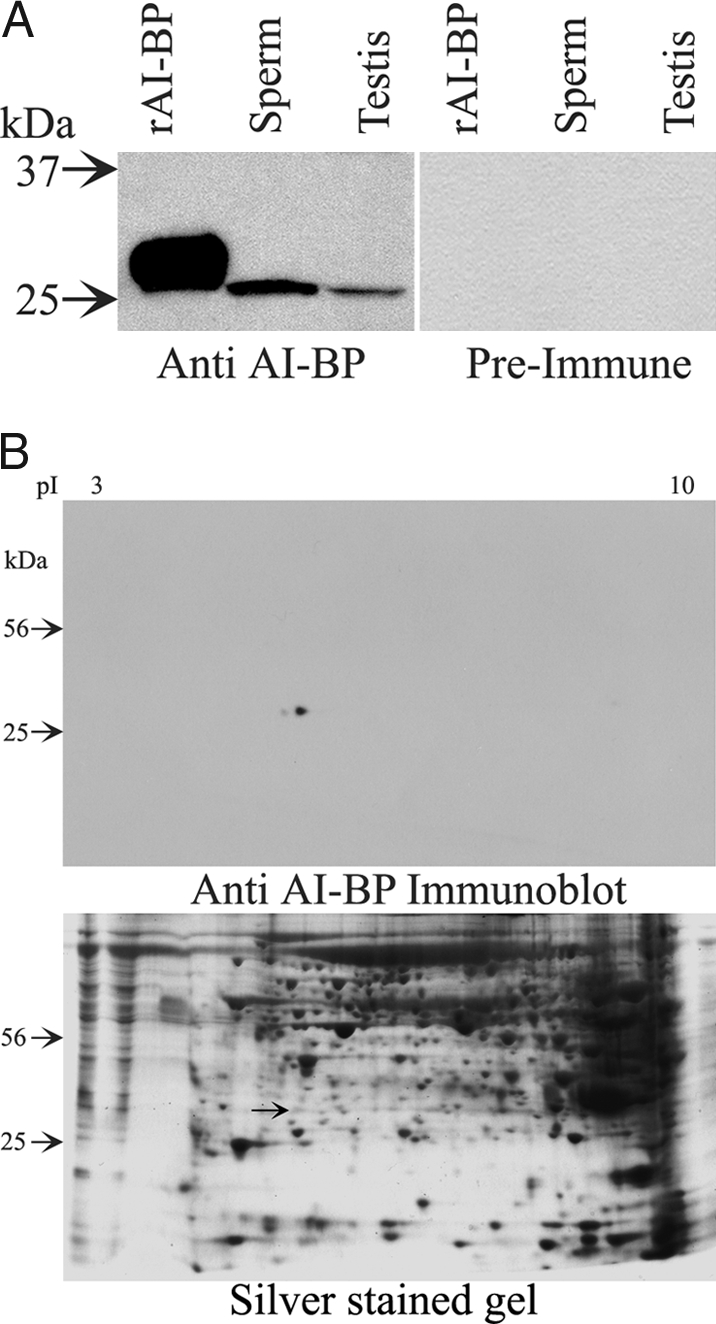

Immunoblot analysis of sperm and testis lysates using polyclonal antibody raised against AI-BP in guinea pigs

Guinea pig antiserum against mouse AI-BP recognized the recombinant immunogen as well as the native protein of 29 kDa in both mouse testis and mouse sperm lysates (Fig. 3A). Preimmune control blots showed no signal (Fig. 3A). The rabbit antibody raised against the AI-BP peptide (263–282) also recognized the recombinant immunogen and native AI-BP in the lysates of mouse sperm and testis (data not shown). In addition, the antipeptide antibody also recognized AI-BP from human and rat sperm at the same molecular size (data not shown). The antiserum also recognized AI-BP at its expected molecular mass (29 kDa) in a two-dimensional immunoblot of mouse sperm lysate (Fig. 3B). The protein spot recognized by the guinea pig antiserum against AI-BP was cored from a companion silver stained gel and submitted for mass spectrometric analysis yielding more than 20 peptides from AI-BP. Together these results confirm that AI-BP is present in mammalian sperm and that specific polyclonal antibodies against AI-BP suitable for further studies have been generated.

Figure 3.

A, Western blots showing reactivity of AI-BP antiserum from the guinea pig with the recombinant AI-BP (rAI-BP) and native AI-BP from mouse sperm and testis. Preimmune serum did not react with either recombinant AI-BP or native AI-BP from mouse sperm or testis. B, Two-dimensional Western blot of mouse sperm lysate showing reactivity of AI-BP from the sperm to AI-BP antiserum from the guinea pig. Total protein loading is shown by a companion silver-stained gel that also marks the corresponding spot of AI-BP (arrow), which was cored out for the mass spectrometric analysis.

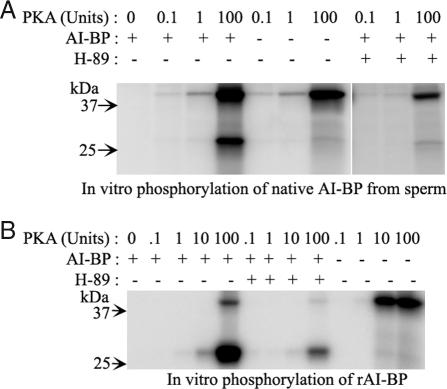

In vitro phosphorylation of AI-BP by PKA

As shown above, two-dimensional gel analysis of sperm protein phosphorylation using γ32P ATP in the presence of dbcAMP and IBMX showed that AI-BP phosphorylation is downstream to PKA activation in the sperm extracts; however, one or more kinases present in the sperm lysate may have been responsible for AI-BP phosphorylation. To examine whether AI-BP is a substrate for PKA, phosphorylation of AI-BP by purified PKA catalytic subunit was tested in vitro using radiolabeled γ32P ATP. Native AI-BP from mouse sperm was immunoprecipitated using antibody against AI-BP raised in rabbit and the presence of AI-BP in aliquots of the immunoprecipitates was confirmed by its appearance on an immunoblot probed with the antibody. AI-BP was phosphorylated in the presence of the catalytic subunit of PKA, evidenced by an intense phosphorylation signal at 29 kDa that was greatly diminished by addition of the PKA inhibitor H89 (Fig. 4A). Autophosphorylation of the catalytic subunit of PKA (band at 42 kDa) served as an internal positive control. These findings were recapitulated using recombinant AI-BP (Fig. 4B), which was also phosphorylated by PKA in vitro. Together these results demonstrate that AI-BP (both native and recombinant) is indeed a substrate for PKA.

Figure 4.

A, Autoradiogram of SDS-PAGE gel from in vitro phosphorylation of native AI-BP immunoprecipitated from mouse sperm by purified PKA catalytic subunits either in the presence or in the absence of a PKA inhibitor H89. The presence or absence of a component in the phosphorylation reaction is represented by + and − signs, respectively. B, Autoradiogram of SDS-PAGE gel from in vitro phosphorylation of recombinant AI-BP by purified PKA catalytic subunits in either the presence or absence of H89.

Determining phosphorylation sites on AI-BP

Mapping phosphorylation sites on proteins is an important part of their characterization as these sites help in understanding how phosphorylation modulates function of the protein. To experimentally map the phosphorylation sites on AI-BP, the purified recombinant AI-BP was phosphorylated in vitro with PKA catalytic subunit and the phosphorylation sites were determined by mass spectrometric analysis. Mass spectrometric analysis of tryptic peptides after in vitro phosphorylation of AI-BP by PKA identified Ser19 as the major phosphorylation site (residues are numbered according to positions in the mature mouse AI-BP). This is in agreement with predictions by the servers NetPhosK (47) and ELM (48), which identify Ser19 as the most likely PKA phosphorylation site in AI-BP. Ser19 is located at the N-terminal segment of AI-BP that is disordered in the crystal structure and is readily accessible for interaction with the kinase. This result further confirms that AI-BP is a PKA substrate.

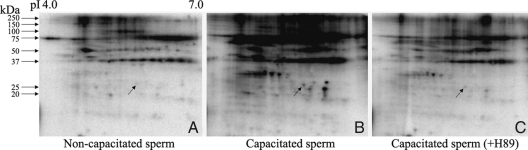

In vivo phosphorylation of AI-BP in intact sperm during capacitation

Our data show that AI-BP is a phosphoprotein that undergoes phosphorylation downstream to PKA activation in sperm, and purified PKA can phosphorylate AI-BP in vitro. However, to demonstrate the physiological relevance of AI-BP phosphorylation in capacitation, it is important to understand its phosphorylation status in intact sperm during capacitation. The intracellular ATP pools of intact sperm were labeled with [32P] orthophosphate for 30 min, and this was followed by incubation under capacitating condition. As expected, a large number of proteins especially in high molecular mass range showed increased in vivo phosphorylation in capacitated sperm when compared with the noncapacitated control (Fig. 5, A and B). Interestingly, AI-BP was unphosphorylated in noncapacitated sperm; however, after capacitation AI-BP showed a significantly increased level of phosphorylation (Fig. 5, A and B). Furthermore, the presence of H89 in the capacitation medium inhibited phosphorylation of AI-BP to a great extent (Fig. 5C). Together, these results demonstrate that AI-BP undergoes physiological phosphorylation during capacitation that is downstream to PKA activation.

Figure 5.

Autoradiograms of two-dimensional gels from in vivo phosphorylation in intact mouse sperm with [32P] orthophosphate in noncapacitation medium (A), capacitation medium (B), and capacitation medium containing H89 (C). AI-BP spot is marked by an arrow in the autoradiograms. On the top pI range and on the left, molecular masses are marked.

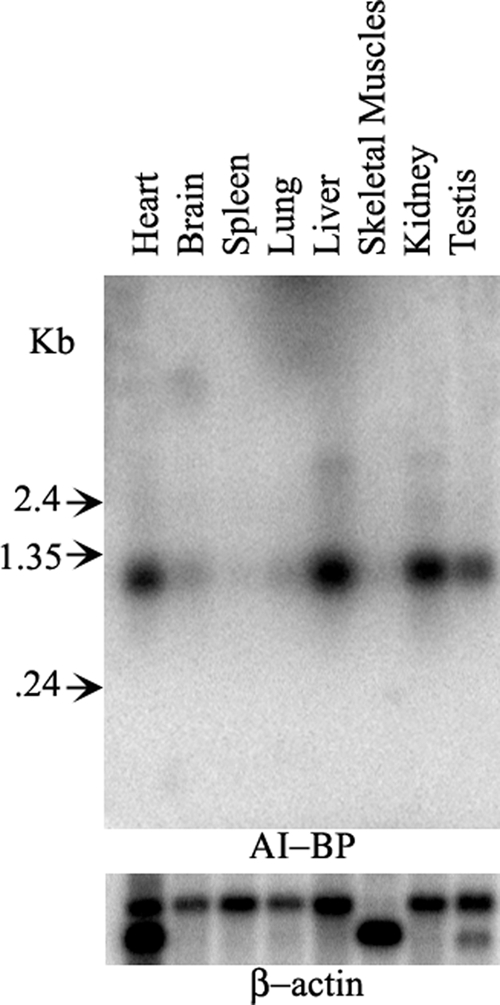

Tissue distribution of AI-BP

A multiple tissue Northern blot of eight different mouse tissues hybridized with mouse AI-BP cDNA probe showed that the AI-BP mRNA was expressed at high levels in heart, liver, kidney, and testis and at low levels in other tissues such as brain, spleen, and lung (Fig. 6). All the tissues showed the same size transcript at the expected position (∼1.0 kb). The expression of AI-BP in a wide range of tissues suggests an important role for AI-BP in some common cellular events.

Figure 6.

Mouse multiple tissue Northern blot probed with 32P-labeled cDNA of mouse AI-BP demonstrating an approximately 1.0 kb band in several tissues with highest levels of expression in heart, liver, kidney, and testis. After probing with AI-BP, the same blot was stripped and reprobed with 32P-labeled β-actin cDNA probe as a loading control (lower panel).

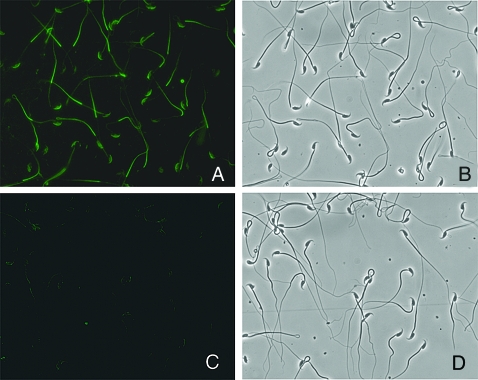

Localization of AI-BP in mouse sperm

Immunofluorescent localization on fixed and permeabilized mouse sperm using the guinea pig antiserum revealed that AI-BP was present in the entire flagellum and in the acrosomal region in the sperm head (Fig. 7). The intensity of the signal was stronger in the principal piece of the flagellum when compared with that in the midpiece. The preimmune control did not stain the sperm (Fig. 7).

Figure 7.

Immunofluorescent localization of AI-BP in mouse sperm using antiserum raised in guinea pig (A) and the preimmune serum (C). The corresponding phase-contrast micrographs of the identical fields are shown next to the respective images (B and D).

Release of AI-BP from sperm during capacitation

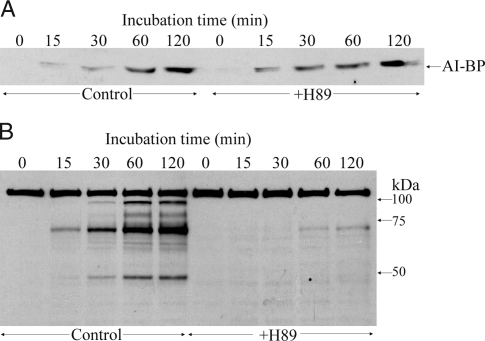

Mouse sperm were incubated in the medium supporting capacitation for different time periods, and the release of AI-BP during capacitation was studied by immunoblot analysis of the media. AI-BP accumulated in the media during capacitation in a time-dependent manner, and thus, a gradual increase in AI-BP released from the sperm into the media was observed (Fig. 8A). The maximum level of AI-BP release was seen at 2 h of incubation, a time period in which capacitation of mouse sperm is considered to be complete, and the amount of AI-BP released into the medium did not increase further, even upon treatment with calcium ionophore (A23187) to induce the acrosome reaction (data not shown). Ponceau-S staining of the blot before the immunoblotting with AI-BP showed an equal total protein content in all the lanes (data not shown). To know whether the PKA pathway is linked to the observed release of AI-BP into the media during capacitation, the effect of H89, a PKA inhibitor, on the capacitation-associated release of AI-BP was studied. After incubation of mouse sperm in capacitation media containing H89 (90 μm), it was observed that H89 stimulated the release of AI-BP from the sperm into the media. Hence, at earlier time points (15 and 30 min), the amount of AI-BP released in the presence of H89 was significantly higher than at the same time points in control untreated sperm (Fig. 8A). As expected, Western blot of the sperm with antiphosphotyrosine antibody showed a time-dependent increase in tyrosine phosphorylation during capacitation and H89 had an inhibitory effect on this phosphorylation (Fig. 8B).

Figure 8.

A, Western blot of AI-BP released into the capacitation medium over different time periods during capacitation in the absence (control) and presence of H89. B, Western blot of the sperm lysates probed with antiphosphotyrosine antibody in the absence (control) and presence of H89.

Crystal structure of AI-BP

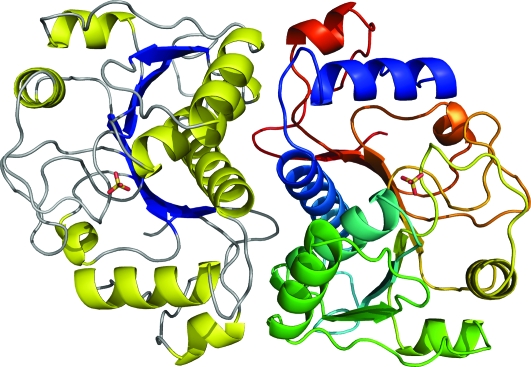

Structure determination of AI-BP was undertaken to gain insight into its function. The AI-BP subunit has a Rossmann-like fold (Fig. 9). The subunit is comprised of a three-layer α-β-α-sandwich with a central β-sheet surrounded by eight helices. The strand topology in the β-sheet can be described as (3)2145678 with the eighth strand antiparallel to all others. The segment corresponding to the third strand commonly present in Rossmann folds is classified as an extended coil due to the relaxed geometry. Two helices, α1 and α2, precede the N-terminal β1-strand. The β-sheet is curved around helices α2 and α3, forming a half-barrel structure. Both the N-terminal segment that includes 25 residues of mature AI-BP and the C-terminal His6-tag are disordered.

Figure 9.

The AI-BP homodimer is comprised of subunits with a Rossmann-like fold. One subunit is colored according to the secondary structure (strands in blue, helices in yellow, loops in gray) and the second subunit is colored in rainbow pattern from blue N terminus to red C terminus of the polypeptide chain. The first 24 residues of mature AI-BP are disordered in the crystal structure. The sulfate anions present in crystallization media are bound above the C-terminal end of the β-sheets. All pictures representing the structure were drawn with PyMOL (30).

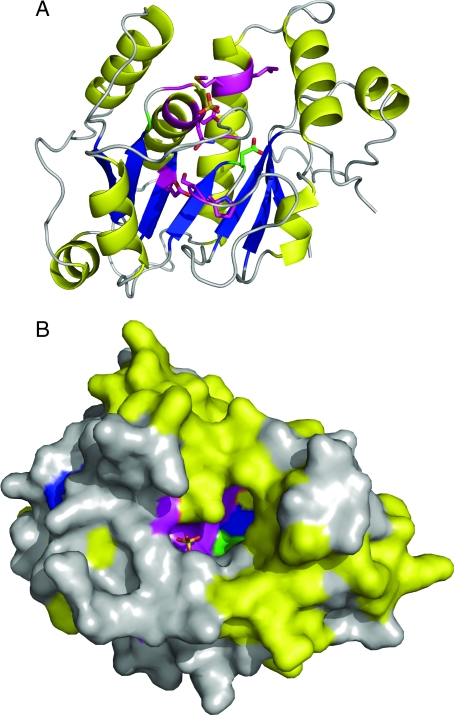

An island of electron density identified as a sulfate anion is observed above the C-terminal end of the AI-BP β-sheet. The sulfate is a component of the crystallization media. It is coordinated by the residues located on the loops following the strands β1 and β4. The sulfate is bound at the top of a large cavity in the protein surface (Fig. 10). The cavity is formed by the residues of a single AI-BP subunit that belong to the helices α1, α2, and α3; strands β5 and β6; and loops following the strands β4, β5, β6, and β7.

Figure 10.

The putative active site of AI-BP marked by conserved residues. The AI-BP subunit is colored according to the secondary structure. The two invariant (green) and 11 highly conserved (magenta) residues (Fig. 1B) are clustered around the two compartment cavity that contains bound sulfate (stick representation). A, Ribbon view of AI-BP subunit with side chains of the invariant and highly conserved residues. B, Surface view of the subunit rotated approximately 90° around the x-axis. The trench compartment of the cavity runs along the surface from left to right and extends into the perpendicular pocket on the upper right side.

The asymmetric unit of the R32 crystal form contains a single AI-BP subunit, but the dimer is generated by the crystallographic symmetry operation. The asymmetric unit of the C2 crystal contains six nearly identical subunits of AI-BP organized in three dimers. The monomers constituting the dimer are oriented toward one another by the inward sides of the curved β-sheets (Fig. 9). The helices α2 and α3 positioned inside of the β-sheet half-barrels are the major contributors to the dimer stabilization along with the helices α1, α4, and α8 and nearby loops. The intersubunit contact area in the dimer is 1360 Å2 per subunit or 13% of its solvent accessible area.

Gel filtration chromatography demonstrates a reversible equilibrium between dimeric and tetrameric forms of recombinant AI-BP. AI-BP from both dimeric and tetrameric fractions produces similar crystals on similar crystallization conditions. The positioning of the AI-BP dimers in the asymmetric unit does not provide clues about the tetramer organization.

Discussion

To gain fertilization-competence, mammalian sperm undergo a series of changes in the female reproductive tract collectively called capacitation. The signaling cascades involved in sperm capacitation in several mammalian species involve cholesterol efflux from the sperm membrane (3,4) and activation of the cAMP/PKA pathway that occurs upstream to tyrosine phosphorylation of several substrates (4,5). Because PKA activation is crucial for capacitation, sperm proteins that undergo phosphorylation downstream to PKA activation are keys to understand the molecular mechanism of capacitation. Previous studies have identified CABYR (49), AKAP3 (50), AKAP4 (51), and other proteins (52) as substrates phosphorylated during capacitation.

In the present study, several sperm proteins underwent increased phosphorylation with γ32P ATP in the presence of cAMP and IBMX as shown by two-dimensional autoradiography. Mass spectrometric microsequencing identified phosphoprotein CP3 as AI-BP, previously shown to interact with apolipoprotein A-I, a major component of the HDL complex (21,22) and a molecule considered a physiological sink for cholesterol efflux from sperm (3,17,53). The phosphorylated spots CP1 and CP2 were identified as the RII subunit of PKA and glycerol-3-phosphate-dehydrogenase, both of which have previously been shown to undergo phosphorylation (54,55).

To investigate the physiological relevance of AI-BP phosphorylation in sperm, in vivo phosphorylation in intact sperm was studied using [32P] orthophosphate. AI-BP showed capacitation-dependent phosphorylation in the intact sperm. H89, a PKA inhibitor, reduced the phosphorylation level of AI-BP, suggesting that phosphorylation of AI-BP in intact sperm is downstream to PKA activation. Together, the results suggest an important role for AI-BP during capacitation that may be regulated by phosphorylation.

A number of proteins (especially those with high molecular mass) showed a marked increase in phosphorylation upon capacitation. This was anticipated because it is known that proteins such as AKAP, CABYR, etc. undergo a very high level of phosphorylation during capacitation. H89 reduced the level of phosphorylation of the majority of the proteins and this result reinforces our understanding that PKA is a key regulator of capacitation.

AI-BP undergoes phosphorylation downstream to the activation of PKA, suggesting that AI-BP is either a direct substrate for PKA or it is phosphorylated by another kinase that is regulated by PKA. In vitro phosphorylation showed that both recombinant and native AI-BP immunoprecipitated from sperm can be phosphorylated directly by PKA. Mass spectral analysis of tryptic peptides after in vitro phosphorylation of AI-BP by PKA identified Ser19 as the major phosphorylation site (residues are numbered according to positions in the mature mouse AI-BP). This is in agreement with predictions by the servers NetPhosK (47) and ELM (48) that suggested Ser19 as the most likely putative PKA phosphorylation site in AI-BP. Ser19 lies in the N-terminal segment of AI-BP that is disordered in the crystal structure and is readily accessible for interaction with its kinase. However, the possibility remains that AI-BP is phosphorylated by a downstream substrate of PKA in vivo. The putative phosphorylation site analysis of eight mammalian AI-BP homologs (sequence identity with mouse AI-BP is above 85%) consistently predicts possible phosphorylation of Ser31 by DNA-activated protein kinase; Ser77 by cyclin-dependent kinase; and Thr126, Ser161, Thr212, and Ser217 by protein kinase C. The AI-BP crystal structure demonstrates that all these residues with exceptions of Thr212 and Ser217 are located at the protein’s surface. Together, these considerations suggest AI-BP is a target in the PKA pathway in sperm. The function of AI-BP needs to be defined to answer the question whether phosphorylation activates or deactivates AI-BP.

AI-BP has been shown to interact with apolipoprotein A-I, a major component of HDL (24). Two different antibodies, one produced in guinea pigs, the other in rabbits, recognized native AI-BP at the expected size in both testis lysates and in sperm by one- and two-dimensional immunoblotting. These antibodies localized AI-BP in the flagellum and the acrosomal region in the sperm head. This localization pattern is similar to that of cholesterol as reported by Travis and Kopf (3). Furthermore, we observed that AI-BP was released into the media during capacitation. This again correlates with capacitation-associated loss of cholesterol into the media (15). To investigate whether release of AI-BP during capacitation is linked to the PKA pathway, effects of H89 on the release of AI-BP were studied. It was consistently observed that in the presence of H89, a higher amount of AI-BP from the sperm was released into the media at 15- and 30-min time points when compared with the untreated control. If the release of AI-BP is a positive modulator of cholesterol efflux and capacitation, then one would expect that PKA inhibitor should inhibit the release of AI-BP from the sperm. Therefore, it is difficult at present to explain the observed increased release of AI-BP at early time points after incubation with H89; however, as more is understood of the exact role of AI-BP in capacitation, this apparent conundrum may resolve. Nonetheless, the data provide a link between the capacitation-dependent release of AI-BP from sperm and the PKA pathway.

It is of interest that AI-BP interaction with apolipoprotein A-I, its localization pattern in sperm, and release into the media during capacitation are common properties shared by AI-BP and cholesterol, and together they suggest a role for AI-BP in cholesterol efflux during capacitation. Binding studies using radioactively labeled cholesterol showed no binding of AI-BP with the cholesterol (data not shown). A strong binding of apolipoprotein A-I to tritiated cholesterol validated the experiments. Thus, our data suggest that AI-BP does not bind to cholesterol directly but rather may be involved in the cholesterol efflux process by interacting with its other known/unknown partners such as apolipoprotein A-I.

Neither general biochemical nor cellular functions of AI-BP or its homologs are known. Indeed, this protein family holds the fourth position in the top 10 list of the highly attractive protein targets for functional characterization (56). The list is based on the wide phyletic distribution of the proteins, their presence in model organisms, a suggested involvement in a fundamental biological function, and a small number of paralogs.

The homologs of AI-BP are present in eukaryotes, bacteria, and archaea. They are closely related, the E values for the homologs from different kingdoms of life reaching 3 × e−14. According to the Pfam database, AI-BP is an N-terminal domain of Yje-related proteins (Yje_N). The Yje_N domains occur either as single proteins or fusions with other domains and are commonly associated with enzymes. In bacteria and archaea, Yje_N are often fused to a C-terminal putative carbohydrate kinase and/or belong to operons that encode enzymes of diverse functions: pyridoxal phosphate biosynthetic protein PdxJ; phosphopantetheine-protein transferase; ATP/GTP hydrolase; and pyruvate-formate lyase 1-activating enzyme. In plants, Yje_N is fused to a C-terminal putative pyridoxamine 5′-phosphate oxidase. In eukaryotes, proteins that consist of (Sm)-FDF-Yje_N domains may be involved in RNA processing. Sm and FDF domains are likely to be responsible for the binding to RNA complexes, whereas the Yje_N domains are suggested to provide an unknown enzymatic activity including dephosphorylation, demethylation, and phosphoester or glycosyl bond hydrolysis (57). The fusion and coexpression of Yje_N proteins with diverse set of enzymes suggests that they are involved in undetermined common metabolic pathways and that the AI-BP homologs possess an enzymatic activity.

Another hint at the enzymatic function of AI-BP is provided by structural analysis. The AI-BP subunit has a Rossmann-like fold, one of the most common protein folds in nature observed in numerous enzyme families (58) (Fig. 8). The Rossmann fold, or mononucleotide-binding β-α-β-α-β unit, was first described in dinucleotide-binding enzymes that combine two units to achieve β3-αB-β2-αA-β1/β4-αd-β5-αE-β6 topology and enable binding of cofactor nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (phosphate) (59).

The AI-BP subunit contains a modified Rossmann-fold in which strand-β3 is transformed to an extended coil due to relaxation of geometry and helix αE is replaced by a loop. In addition, two helices precede the strand-β1 and two α-β-segments extend the β-sheet. The loops β1-αA and β4-αD contain characteristic patterns of glycines and small side chain residues, GPGNNG and GFSFKG, respectively (Fig. 1B).

In mammalian AI-BPs but not in homologs from the other species, the Yje_N domain is preceded by a signal peptide and an additional 25- to 30-residue N-terminal segment (Fig. 1B). In mouse AI-BP, the N-terminal segment is separated from the Rossmann-like domain by a flexible linker AGAA and is disordered in the crystal structure. This segment contains Ser19 that is phosphorylated by PKA. Phosphorylation of Ser19 may promote ordering and/or interactions of the N-terminal segment modulating activity of AI-BP.

The structure of AI-BP reveals a large two compartment cavity on the protein surface located above the C-terminal end of the strands β4, β5, and β6 (Fig. 10). The cavity is comprised of the 10Å × 4Å × 4Å trench running along the protein surface, one end of which extends into a perpendicular 10Å deep pocket with a 3Å × 7Å opening. The location of the cavity in AI-BP corresponds to a typical location of the active site in the Rossmann-fold enzymes. The importance of the cavity for AI-BP function is supported by the fact that it contains both invariant residues among 387 eukaryotic, bacterial, and archaeal homologs of AI-BP present in Pfam database, Gly86 and Asp188 (Fig. 10). In addition, all 11 highly conservative residues among AI-BP homologs are clustered within or near the cavity. The sulfate anion present in the crystallization media is bound in the trench compartment of the cavity. The sulfate that is known to occupy phosphate binding sites is coordinated by the residues of the Gly-rich loops β1-αA and β4-αD that serve as nucleotide phosphate binding loops in traditional Rossmann folds. Attempts to identify the active site of AI-BP with Catalytic Site Atlas (60) and Profunc (61) did not yield any assessments that include the conserved residues in the AI-BP homologs or residues located in the cavity.

The AI-BP structure is similar to the structures of its two homologs with unknown functions determined in the structural genomics projects. YNL200C from Saccharomyces cerevisiae (PDB: 1JZT (62) contains a single Yje_N domain, whereas the tm0922 protein from Thermotoga maritima (PDB: 2AX3) combines the Yje_N domain with a C-terminal putative carbohydrate kinase domain. The root mean square deviation (rmsd) for 216 superimposed Cα atoms of AI-BP and YNL200C is 1.0 Å. The rmsd for 180 Cα atoms of AI-BP and tm0922 is 1.6 Å. Both YNL200C and tm0922 contain a large cavity observed in AI-BP. A chloride anion was observed in the YNL200C structure at the site corresponding to the sulfate-binding site of AI-BP. In tm0922, sulfate-binding site is not occupied but the pocket compartment of the cavity contains a bound glycerol molecule.

Thus, the structural analysis suggests that AI-BP and its homologs perform an enzymatic function that is likely to include a nucleotide-containing substrate or cofactor. The list of Rossmann-fold enzymes acting on the nucleotide-containing substrates includes nucleotide-dependent dehydrogenases, epimerases, glycosyltransferases, nucleotide transferases, and S-adenosyl methionine. The location and organization of the active site deducted from the crystal structure of AI-BP and its two homologs is likely to be conserved in other Yje_N due to the high degree of sequence similarity among the cavity-forming residues.

Our specific studies with sperm lead us to a more general postulate that AI-BP may participate in lipid transport in a variety of organs in higher eukaryotes. Several lines of evidence noted above support this concept: (1) AI-BP interacts with apolipoprotein A-I (24); (2) AI-BP localizes in the domains in sperm in which cholesterol is known to be localized (3); and (3) AI-BP is lost into the medium during capacitation, a phenomenon that accompanies the cholesterol release. The Northern blot analysis indicated that AI-BP is present in a number of tissues, and its expression was found to be at high level in heart, liver, kidney, and testis. This wide tissue distribution coupled to conservation of AI-BP in different species points to a role in basic metabolism that is unknown today.

As an interacting partner with apolipoprotein A-I, AI-BP has a potential role in HDL mediated lipid transport in general and cholesterol efflux in particular. Plasma lipid levels are quantitative traits that are controlled by multiple genes, and in one study six quantitative trait loci for plasma cholesterol levels spanning chromosomes 1, 3, and 9 were identified in mouse (63,64). The AI-BP gene (Apoa1bp) in mouse is located at 3 F1 within the region of one of these quantitative trait loci (Cq3), which is thought to control plasma cholesterol and phospholipid levels (63,64). This is further strengthened by the evidence that the human AI-BP gene (APOA1BP) is located at 1q22-q21.2 on chromosome 1, which is syntenic to the mouse Cq3 locus and to which a familial combined hyperlipidemia locus (1q21-q23; HYPLIP1) has been mapped (65,66,67,68). This trait has been mapped in Finnish, German, Chinese, and Mexican families with a prevalence of 1–2% in general population. Thus, the genetic loci associated with hyperlipidemia in both mice and men include the site of the AI-BP gene, further supporting the hypothesis that AI-BP is involved in the process of cholesterol efflux.

Acknowledgments

We thank Kristina T. Nelson and Nicholas E. Sherman (Biomolecular Research Facility, University of Virginia) for the mass spectrometric analysis.

Footnotes

This work was supported by Grants U54 29099 and D43 TW/HD 00654 (to J.C.H.), GM-53163 (to W.M.), HD38082 and HD44044 (to P.E.V.) from the National Institutes of Health (NIH); a grant (to J.C.H.) from Schering AG; and a postdoctoral fellowship (to K.N.J.) from the Fogarty International Center, NIH.

Disclosure Statement: The authors of this manuscript have nothing to declare.

First Published Online January 17, 2008

Abbreviations: AI-BP, Apolipoprotein A-I binding protein; dbcAMP, dibutyryladenosine cAMP; HDL, high-density lipoprotein; IBMX, isobutylmethylxanthine; IPTG, isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside; PBS-T, PBS and Tween 20; PKA, protein kinase A; rmsd, root mean square deviation; WH, Whitten’s-HEPES buffered medium.

References

- Austin CR 1952 The capacitation of the mammalian sperm. Nature 170:326 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yanagimachi R 1994 Mammalian fertilization. 2nd ed. New York: Raven Press [Google Scholar]

- Travis AJ, Kopf GS 2002 The role of cholesterol efflux in regulating the fertilization potential of mammalian spermatozoa. J Clin Invest 110:731–736 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Visconti PE, Westbrook VA, Chertihin O, Demarco I, Sleight S, Diekman AB 2002 Novel signaling pathways involved in sperm acquisition of fertilizing capacity. J Reprod Immunol 53:133–150 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jha KN, Kameshwari DB, Shivaji S 2003 Role of signaling pathways in regulating the capacitation of mammalian spermatozoa. Cell Mol Biol 49:329–340 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ho HC, Suarez SS 2001 Hyperactivation of mammalian spermatozoa: function and regulation. Reproduction 122:519–526 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boatman DE, Robbins RS 1991 Bicarbonate: carbon-dioxide regulation of sperm capacitation, hyperactivated motility, and acrosome reactions. Biol Reprod 44:806–813 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baldi E, Casano R, Falsetti C, Krausz C, Maggi M, Forti G 1991 Intracellular calcium accumulation and responsiveness to progesterone in capacitating human spermatozoa. J Androl 12:323–330 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gadella BM, Harrison RA 2000 The capacitating agent bicarbonate induces protein kinase A-dependent changes in phospholipid transbilayer behavior in the sperm plasma membrane. Development 127:2407–2420 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeng Y, Clark EN, Florman HM 1995 Sperm membrane potential: hyperpolarization during capacitation regulates zona pellucida-dependent acrosomal secretion. Dev Biol 171:554–563 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demarco IA, Espinosa F, Edwards J, Sosnik J, De La Vega-Beltran JL, Hockensmith JW, Kopf GS, Darszon A, Visconti PE 2003 Involvement of a Na+/HCO-3 cotransporter in mouse sperm capacitation. J Biol Chem 278:7001–7009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esposito G, Jaiswal BS, Xie F, Krajnc-Franken MA, Robben TJ, Strik AM, Kuil C, Philipsen RL, van Duin M, Conti M, Gossen JA 2004 Mice deficient for soluble adenylyl cyclase are infertile because of a severe sperm-motility defect. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA [Erratum (2004) 101:5180 Note: Jaiswal Byjay S (corrected to Jaiswal Bijay S)] 101:2993–2998 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hess KC, Jones BH, Marquez B, Chen Y, Ord TS, Kamenetsky M, Miyamoto C, Zippin JH, Kopf GS, Suarez SS, Levin LR, Williams CJ, Buck J, Moss SB 2005 The “soluble” adenylyl cyclase in sperm mediates multiple signaling events required for fertilization. Dev Cell 9:249–259 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nolan MA, Babcock DF, Wennemuth G, Brown W, Burton KA, McKnight GS 2004 Sperm-specific protein kinase A catalytic subunit Cα2 orchestrates cAMP signaling for male fertility. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 101:13483–13488 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Visconti PE, Ning X, Fornes MW, Alvarez JG, Stein P, Connors SA, Kopf GS 1999 Cholesterol efflux-mediated signal transduction in mammalian sperm: cholesterol release signals an increase in protein tyrosine phosphorylation during mouse sperm capacitation. Dev Biol 214:429–443 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi YH, Toyoda Y 1998 Cyclodextrin removes cholesterol from mouse sperm and induces capacitation in a protein-free medium. Biol Reprod 59:1328–1333 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehrenwald E, Foote RH, Parks JE 1990 Bovine oviductal fluid components and their potential role in sperm cholesterol efflux. Mol Reprod Dev 25:195–204 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halling A 1993 Altered patterns of proteins released in vitro from oviductal and uterine tissue from adult female mice treated neonatally with diethylstilbestrol. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol 44:227–237 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Argraves WS, Morales CR 2004 Immunolocalization of cubilin, megalin, apolipoprotein J, and apolipoprotein A-I in the uterus and oviduct. Mol Reprod Dev 69:419–427 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Therien I, Soubeyrand S, Manjunath P 1997 Major proteins of bovine seminal plasma modulate sperm capacitation by high-density lipoprotein. Biol Reprod 57:1080–1088 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mendez AJ 1997 Cholesterol efflux mediated by apolipoproteins is an active cellular process distinct from efflux mediated by passive diffusion. J Lipid Res 38:1807–1821 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaus K, Kritharides L, Schmitz G, Boettcher A, Drobnik W, Langmann T, Quinn CM, Death A, Dean RT, Jessup W 2004 Apolipoprotein A-1 interaction with plasma membrane lipid rafts controls cholesterol export from macrophages. FASEB J 18:574–576 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jha KN, Salicioni AM, Arcelay E, Chertihin O, Kumari S, Herr JC, Visconti PE 2006 Evidence for the involvement of proline-directed serine/threonine phosphorylation in sperm capacitation. Mol Hum Reprod 12:781–789 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ritter M, Buechler C, Boettcher A, Barlage S, Schmitz-Madry A, Orso E, Bared SM, Schmiedeknecht G, Baehr CH, Fricker G, Schmitz G 2002 Cloning and characterization of a novel apolipoprotein A-I binding protein, AI-BP, secreted by cells of the kidney proximal tubules in response to HDL or ApoA-I. Genomics 79:693–702 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rudolph C, Sigruener A, Hartmann A, Orso E, Bals-Pratsch M, Gronwald W, Seifert B, Kalbitzer HR, Verdorfer I, Luetjens CM, Ortmann O, Bornstein SR, Schmitz G 2007 ApoA-I-binding protein (AI-BP) and its homologues hYjeF_N2 and hYjeF_N3 comprise the YjeF_N domain protein family in humans with a role in spermiogenesis and oogenesis. Horm Metab Res 39:322–335 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore GD, Ayabe T, Visconti PE, Schultz RM, Kopf GS 1994 Roles of heterotrimeric and monomeric G proteins in sperm-induced activation of mouse eggs. Development 120:3313–3323 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naaby-Hansen S, Flickinger CJ, Herr JC 1997 Two-dimensional gel electrophoretic analysis of vectorially labeled surface proteins of human spermatozoa. Biol Reprod 56:771–787 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feinberg AP, Vogelstein B 1983 A technique for radiolabeling DNA restriction endonuclease fragments to high specific activity. Anal Biochem 132:6–13 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laemmli UK 1970 Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature 227:680–685 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delano WL 2002 The PyMOL molecular graphics system on http://www.pymol.org [Google Scholar]

- Rosenbaum G, Alkire RW, Evans G, Rotella FJ, Lazarski K, Zhang RG, Ginell SL, Duke N, Naday I, Lazarz J, Molitsky MJ, Keefe L, Gonczy J, Rock L, Sanishvili R, Walsh MA, Westbrook E, Joachimiak A 2006 The Structural Biology Center 19ID undulator beamline: facility specifications and protein crystallographic results. J Synchrotron Radiat 13:30–45 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otwinowski Z, Minor W 1997 Processing of x-ray diffraction data collected in oscillation mode. Methods Enzymol 276:307–326 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minor W, Cymborowski M, Otwinowski Z, Chruszcz M 2006 HKL-3000: the integration of data reduction and structure solution—from diffraction images to an initial model in minutes. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr 62:859–866 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider TR, Sheldrick GM 2002 Substructure solution with SHELXD. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr 58:1772–1779 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheldrick GM 2002 Macromolecular phasing with SHELXE. Z Krist 217:644–650 [Google Scholar]

- Otwinowski Z 1991 Oscillation data reduction program. Daresbury Study Weekend Proceedings, Science and Engineering Research Council, Daresbury Laboratory, UK; 80–86 [Google Scholar]

- Cowtan K 1994 DM: an automated procedure for phase improvement by density modification. CCP4/ESF-EACBM Newsletter on Protein Crystallography 31:34–38 [Google Scholar]

- Jones TA, Zou JY, Cowan SW, Kjeldgaard M 1991 Improved methods for building protein models in electron density maps and the location of errors in these models. Acta Crystallogr A 47(Pt 2):110–119 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 1994 The CCP4 suite: programs for protein crystallography. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr 50:760–763 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terwilliger T 2004 SOLVE and RESOLVE: automated structure solution, density modification and model building. J Synchrotron Radiat 11:49–52 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamzin VS, Wilson KS 1997 Automated refinement for protein crystallography. Methods Enzymol 277:269–305 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emsley P, Cowtan K 2004 Coot: model-building tools for molecular graphics. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr 60:2126–2132 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murshudov GN, Vagin AA, Dodson EJ 1997 Refinement of macromolecular structures by the maximum-likelihood method. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr 53:240–255 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaguine AA, Richelle J, Wodak SJ 1999 SFCHECK: a unified set of procedures for evaluating the quality of macromolecular structure-factor data and their agreement with the atomic model. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr 55:191–205 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang H, Guranovic V, Dutta S, Feng Z, Berman HM, Westbrook JD 2004 Automated and accurate deposition of structures solved by X-ray diffraction to the Protein Data Bank. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr 60:1833–1839 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lovell SC, Davis IW, Arendall 3rd WB, de Bakker PI, Word JM, Prisant MG, Richardson JS, Richardson DC 2003 Structure validation by Cα geometry: φ, ψ and Cβ deviation. Proteins 50:437–450 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blom N, Sicheritz-Ponten T, Gupta R, Gammeltoft S, Brunak S 2004 Prediction of post-translational glycosylation and phosphorylation of proteins from the amino acid sequence. Proteomics 4:1633–1649 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puntervoll P, Linding R, Gemund C, Chabanis-Davidson S, Mattingsdal M, Cameron S, Martin DM, Ausiello G, Brannetti B, Costantini A, Ferre F, Maselli V, Via A, Cesareni G, Diella F, Superti-Furga G, Wyrwicz L, Ramu C, McGuigan C, Gudavalli R, Letunic I, Bork P, Rychlewski L, Kuster B, Helmer-Citterich M, Hunter WN, Aasland R, Gibson TJ 2003 ELM server: a new resource for investigating short functional sites in modular eukaryotic proteins. Nucleic Acids Res 31:3625–3630 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naaby-Hansen S, Mandal A, Wolkowicz MJ, Sen B, Westbrook VA, Shetty J, Coonrod SA, Klotz KL, Kim YH, Bush LA, Flickinger CJ, Herr JC 2002 CABYR, a novel calcium-binding tyrosine phosphorylation-regulated fibrous sheath protein involved in capacitation. Dev Biol 242:236–254 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mandal A, Naaby-Hansen S, Wolkowicz MJ, Klotz K, Shetty J, Retief JD, Coonrod SA, Kinter M, Sherman N, Cesar F, Flickinger CJ, Herr JC 1999 FSP95, a testis-specific 95-kilodalton fibrous sheath antigen that undergoes tyrosine phosphorylation in capacitated human spermatozoa. Biol Reprod 61:1184–1197 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carrera A, Moos J, Ning XP, Gerton GL, Tesarik J, Kopf GS, Moss SB 1996 Regulation of protein tyrosine phosphorylation in human sperm by a calcium/calmodulin-dependent mechanism: identification of A kinase anchor proteins as major substrates for tyrosine phosphorylation. Dev Biol 180:284–296 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ficarro S, Chertihin O, Westbrook VA, White F, Jayes F, Kalab P, Marto JA, Shabanowitz J, Herr JC, Hunt DF, Visconti PE 2003 Phosphoproteome analysis of capacitated human sperm. Evidence of tyrosine phosphorylation of a kinase-anchoring protein 3 and valosin-containing protein/p97 during capacitation. J Biol Chem 278:11579–11589 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langlais J, Kan FW, Granger L, Raymond L, Bleau G, Roberts KD 1988 Identification of sterol acceptors that stimulate cholesterol efflux from human spermatozoa during in vitro capacitation. Gamete Res 20:185–201 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keryer G, Luo Z, Cavadore JC, Erlichman J, Bornens M 1993 Phosphorylation of the regulatory subunit of type IIβ cAMP-dependent protein kinase by cyclin B/p34cdc2 kinase impairs its binding to microtubule-associated protein 2. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 90:5418–5422 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tisdale EJ 2002 Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase is phosphorylated by protein kinase Cι/λ and plays a role in microtubule dynamics in the early secretory pathway. J Biol Chem 277:3334–3341 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galperin MY, Koonin EV 2004 ‘Conserved hypothetical’ proteins: prioritization of targets for experimental study. Nucleic Acids Res 32:5452–5463 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anantharaman V, Aravind L 2004 Novel conserved domains in proteins with predicted roles in eukaryotic cell-cycle regulation, decapping and RNA stability. BMC Genomics 5:45 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolf YI, Brenner SE, Bash PA, Koonin EV 1999 Distribution of protein folds in the three superkingdoms of life. Genome Res 9:17–26 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rossmann MG, Moras D, Olsen KW 1974 Chemical and biological evolution of nucleotide-binding protein. Nature 250:194–199 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porter CT, Bartlett GJ, Thornton JM 2004 The Catalytic Site Atlas: a resource of catalytic sites and residues identified in enzymes using structural data. Nucleic Acids Res 32:D129–D133 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laskowski RA, Watson JD, Thornton JM 2005 ProFunc: a server for predicting protein function from 3D structure. Nucleic Acids Res 33:W89–W93 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chance MR, Bresnick AR, Burley SK, Jiang JS, Lima CD, Sali A, Almo SC, Bonanno JB, Buglino JA, Boulton S, Chen H, Eswar N, He G, Huang R, Ilyin V, McMahan L, Pieper U, Ray S, Vidal M, Wang LK 2002 Structural genomics: a pipeline for providing structures for the biologist. Protein Sci 11:723–738 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korstanje R, Albers JJ, Wolfbauer G, Li R, Tu AY, Churchill GA, Paigen BJ 2004 Quantitative trait locus mapping of genes that regulate phospholipid transfer activity in SM/J and NZB/BlNJ inbred mice. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 24:155–160 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suto J 2006 Characterization of Cq3, a quantitative trait locus that controls plasma cholesterol and phospholipid levels in mice. J Vet Med Sci 68:303–309 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huertas-Vazquez A, del Rincon JP, Canizales-Quinteros S, Riba L, Vega-Hernandez G, Ramirez-Jimenez S, Auron-Gomez M, Gomez-Perez FJ, Aguilar-Salinas CA, Tusie-Luna MT 2004 Contribution of chromosome 1q21–q23 to familial combined hyperlipidemia in Mexican families. Ann Hum Genet 68:419–427 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pajukanta P, Bodnar JS, Sallinen R, Chu M, Airaksinen T, Xiao Q, Castellani LW, Sheth SS, Wessman M, Palotie A, Sinsheimer JS, Demant P, Lusis AJ, Peltonen L 2001 Fine mapping of Hyplip1 and the human homolog, a potential locus for FCHL. Mamm Genome 12:238–245 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pajukanta P, Lilja HE, Sinsheimer JS, Cantor RM, Lusis AJ, Gentile M, Duan XJ, Soro-Paavonen A, Naukkarinen J, Saarela J, Laakso M, Ehnholm C, Taskinen MR, Peltonen L 2004 Familial combined hyperlipidemia is associated with upstream transcription factor 1 (USF1). Nat Genet 36:371–376 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pajukanta P, Nuotio I, Terwilliger JD, Porkka KV, Ylitalo K, Pihlajamaki J, Suomalainen AJ, Syvanen AC, Lehtimaki T, Viikari JS, Laakso M, Taskinen MR, Ehnholm C, Peltonen L 1998 Linkage of familial combined hyperlipidaemia to chromosome 1q21–q23. Nat Genet 18:369–373 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barton GJ 1993 ALSCRIPT: a tool to format multiple sequence alignments. Prot Eng 6:37–40 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]