Abstract

The availability of multiple teleost (bony fish) genomes is providing unprecedented opportunities to understand the diversity and function of gene duplication events using comparative genomics. Here we describe the cloning and functional characterization of two novel vitamin D receptor (VDR) paralogs from the freshwater teleost medaka (Oryzias latipes). VDR sequences were identified through mining of the medaka genome database in which gene organization and structure was determined. Two distinct VDR genes were identified in the medaka genome and mapped to defined loci. Each VDR sequence exhibits unique intronic organization and dissimilar 5′ untranslated regions, suggesting they are not isoforms of the same gene locus. Phylogenetic comparison with additional teleosts and mammalian VDR sequences illustrate that two distinct clusters are formed separating aquatic and terrestrial species. Nested within the teleost cluster are two separate clades for VDRα and VDRβ. The topology of teleost VDR sequences is consistent with the notion of paralogous genes arising from a whole genome duplication event prior to teleost radiation. Functional characterization was conducted through the development of VDR expression vectors including Gal4 chimeras containing the yeast Gal4 DNA binding domain fused to the medaka VDR ligand binding domain and full-length protein. The common VDR ligand 1α,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 [1α,25(OH)2D3] resulted in significant transactivation activity with both the Gal4 and full-length constructs of medaka (m) VDRβ. Comparatively, transactivation of mVDRα with 1α,25(OH)2D3 was highly attenuated, suggesting a functional divergence between these two nuclear receptor paralogs. We additionally demonstrate through coactivator studies that mVDRα is still functional; however, it exhibits a different sensitivity to 1α,25(OH)2D3, compared with VDRβ. These results suggest that in mVDRα and VDRβ have undergone a functional divergence through a process of sub- and/or neofunctionalization of VDR nuclear receptor gene pairs.

NUCLEAR RECEPTORS (NRS) are ligand-dependent transcription factors that bind to lipophilic signaling molecules, resulting in the control and expression of target genes (1). Such control facilitates cellular responses to endogenous and exogenous ligands through coordination of complex transcriptional responses (2). Genomics efforts in several fish species have revealed orthologs for most mammalian NRs including those for steroid hormones, orphan receptors, and members of all seven NR families (3,4). In fact, most NRs from teleosts, some cartilaginous fishes, and other lower vertebrates exhibit strong homologies to mammalian sequences. However, comparative genomic, phylogenetic and functional studies demonstrate that in some instances, teleost NRs contain structural modifications, which may alter receptor activities (2).

Teleosts (bony fish) have a larger compliment of NRs (68 in Takifugu rubripes, 71 in Tetraodon nigroviridis) than mammals (∼50) (3,4). In theory, this is due to whole genome duplication events that have occurred during vertebrate evolution (5,6). One proposed mechanism is the serial 2R genome duplication hypothesis, which states that the vertebrate genome is a result of two rapid and successive rounds of genome duplication around the time of the divergence of jawless and jawed vertebrates, approximately 500 million yr ago (Mya) (6). Additionally, in a stem linage of ray-finned fish, Actinopterygii, but not terrestrial vertebrates, a third fish-specific whole genome duplication occurred before the radiation of the teleostean fishes and after the divergence of tetrapods (7). The fate of most duplicated genes is nonfunctionalization and gene loss. However, it is estimated that up to 20–50% of paralogous genes are retained through a process of neofunctionalization or subfunctionalization and subsequent independent evolutionary events (8).

It should be noted, however, that orthology (orthologs divergence due to speciation events) and parology (paralogs divergence due to gene duplication events) do not always imply conservation in gene function (9). As such, genome duplications are thought to be an important mechanism driving species diversification. In the case of nuclear receptors, whole genome and lineage-specific duplication events in teleosts have resulted in the partitioning of receptor function in certain taxa (10,11,12). This may be highly relevant when examining paralogous functions of transcription factors in vertebrates, which have undergone considerable diversification (13,14). As such, multiplicity, gene loss, acquisition of novel gene function, and/or subfunctional partitioning of nuclear receptors and other transcription factors may be an important factor contributing to signal diversification, specification and evolutionary diversification of teleosts (15,16).

The vitamin D receptor (VDR) was among the first NRs identified and its role as a high-affinity receptor for mediating physiological actions of a biologically active metabolite of vitamin D, 1α,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 [1α,25(OH)2D3], was quickly determined (17,18). The genomic mechanism of action of VDR is prototypical of steroid hormone receptors as a ligand-activated transcription factor. The classical role of VDR includes essential interactions between the kidney, bone, parathyroid gland, and intestine to maintain extracellular calcium levels and ensure normal cellular physiology and skeletal integrity (19). Several novel functions for VDR have additionally been discovered including a role of VDR in immune function, cell proliferation, and xenobiotic and endobiotic metabolism (20,21).

VDRs have been identified from a number of aquatic vertebrates with calcified endoskeletons. Recently VDR was additionally cloned from the jawless agnathan lamprey, representing the most ancient lineage among extant vertebrates (22). VDR is also present in Urochordate genomes, including Ciona intestinalis and C. savigny (sea squirts), suggesting an early ancestral role of VDR in Deuterostome physiology (23). However, it has been recently demonstrated that VDR from C. intestinalis is nonresponsive to the prototypic ligand 1α,25(OH)2D3 (24). This suggests that VDR in Ciona may have an ancestral function distinct from interaction with 1α,25(OH)2D3. Before the recent cloning of VDR in aquatic organisms, general convention speculated that the 1α,25(OH)2D3-VDR system originated in terrestrial animals. It is well known however that vitamin D is one of the oldest hormones and is present in life forms including phytoplankton and zooplankton (25). It is unclear why phytoplankton and zooplankton have the capacity to produce vitamin D. One hypothesis is that vitamin D photoproducts serve as a photon sink protecting DNA, RNA, and proteins from the damaging effects of high-energy UV radiation (26). This has led to the speculation that the function of vitamin D and VDR in aquatic organisms may be different from those classical functions in terrestrial animals (27,28). Moreover, the role of vitamin D in calcium regulation in teleosts remains equivocal. Teleost endocrine physiology is well adapted to an external aquatic environment that provides a constant source of Ca2+ ions. This suggests that the mechanism(s) regulating Ca2+ mobilization may differ between aquatic and terrestrial organisms and possibly between marine and fresh water fish species (29). Studies in different fish species are contradictory, with a majority of evidence suggesting that VDR does not mediate calcium mobilization from fish enterocytes (28,30,31). The presence of a VDR in the sea lamprey as well as sea squirts suggests that regulation of calcium may not be a critical function of ancestral VDR (22,24). Supporting this claim is the observation that VDR expression precedes bone formation during Xenopus development (32).

These findings highlight how little is known about the physiology of ancestral receptor function and the role of VDR in aquatic animals. The notion of far more complex signaling by NR ligands and in some instances a duplicated repertoire of receptors will greatly improve our understanding of the origins of NRs in mediating endocrine and physiological functions. For this purpose we have identified and characterized two VDR paralogs form the Japanese medaka (m), mVDRα and mVDRβ.

Materials and Methods

Test animals

Medaka (Oryzias latipes) are small (3–5 cm adult length) oviparous fresh water fish native to rice paddies of Japan, Korea, and eastern China. Male and female fish used for this study were collected from an orange-red line and maintained under standard recirculating aquaculture conditions. Water was maintained at a constant temperature of 25 C and photoperiod was kept at a constant 16-h light, 8-h dark cycle. Care and culture of fish followed protocols approved by the North Carolina State University and Duke University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committees.

VDR cloning

mVDRα and VDRβ sequences were identified within the medaka genome database (Medaka Genome Project, http://dolphin.lab.nig.ac.jp/medaka/) by conducting a generalized BLAST search using a query sequence representing the P box domain of human VDR located within the highly conserved DNA binding region for the nuclear receptor superfamily. Full-length transcripts were subsequently determined by identifying transcriptional start and stop codons for each gene within the medaka genome. cDNAs containing a complete open reading frames (ORFs) for each gene were produced by PCR using primer sets that spanned the entire nucleic acid sequence for each gene paralog. PCR primers were flanked by restriction sites for incorporation and transfer between appropriate cloning and expression vectors. mVDRα and VDRβ cDNAs were compared with in silico genomic sequence to determine intron-exon boundaries using the Spidey software program (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/ieb/research/ostell/spidey/) and through the gene prediction analysis tool in the Ensembl medaka database (http://www.ensembl.org/index.html). These findings were confirmed by bidirectional sequencing of genomic DNA and cDNA sequence.

All cDNAs were amplified from extracts of medaka liver total RNA. Livers were homogenized with 1 ml RNA Bee (TelTest, Friendswood, TX) using a stainless steel Polytron homogenizer (Kinematica, Bohemia, NY) followed by cleanup and on-column DNase treatment using an RNeasy minikit (QIAGEN, Valencia, CA). RNA was eluted with 30 μl RNase-free water. RNA quantity and quality were verified using an 2100 bioanalyzer (Agilent, Santa Clara, CA) and ND-1000 spectrophotometer (NanoDrop, Wilmington, DE). First-strand cDNA was made from total RNA (1–3 μg) and diluted with RNase-free water to a final volume of 10 μl, and 1 μl oligo(dT)15 (500 μg/ml; Promega, Madison, WI) and 1 μl 10 mm deoxynucleotide triphosphates were mixed with diluted RNA to yield a final volume of 20 μl. The mix was heated to 65 C for 5 min and chilled on ice for 2 min. After centrifugation, 4 μl 5× first-strand buffer (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA), 2 μl of 0.1 m dithiothreitol, and 1 μl RNase OUT inhibitor (40 U/μl; Invitrogen) were added to each reaction and heated to 37 C. After a 2-min incubation, 1 μl SuperScript reverse transcriptase (200 U/μl; Invitrogen) was added to each reaction and mRNA reverse transcribed at 37 C for 1 h. All reverse transcriptase reactions were then inactivated by incubating at 70 C for 15 min. cDNAs were stored at −20 C until PCR. PCR primers for mVDRα and mVDRβ were designed using PrimerQuest (Integrated DNA Technologies, Coralville, IA) with integrated restriction sites for cloning: mVDRα forward primer was 5′-ATGGAGTCCATTACCGTGAC-3′, reverse primer 5′-CTATGACACCTCGCTGCCGA-3′ and mVDRβ forward 5′-ATGGAGGCCACTGTTGTGAG-3′, reverse 5′-CTAGGAGACCTCGCTGCCAA-3′. For each 25-μl PCR, first-strand cDNAs were amplified using 2 μl (100–300 ng), first-strand cDNA, 9 μl RNase-free water, 0.75 μl 10 μm forward primer (0.3 μm), 0.75 μl 10 μm reverse primer (0.3 μm), and 12.5 μl 2× Advantage Taq PCR master mix (CLONTECH, Santa Clara, CA). PCR conditions were 95 C for 1.5 min followed by 35 cycles of 94 C for 15 sec, 55 C for 30 sec, and 72 C for 1 min. PCR products for mVDRα and mVDRβ were cloned into the TA cloning vector pCR2.1 (Invitrogen) as per the manufacturer’s suggestions.

5′ Rapid amplification of cDNA ends was conducted using a mixed marathon cDNA library from medaka liver, brain, and testis (CLONTECH) to identify 5′ untranslated regions (UTRs) for both mVDRα and mVDRβ. 5′ UTR sequences were then compared and BLASTed against the medaka genome to determine the presence of a 5′ noncoding exon upstream of each translational start site. VDR chromosome location was determined by BLASTing the entire mVDR cDNA sequence against the Ensembl medaka database.

Gal4-VDR chimera expression constructs were made in the XgalX plasmid vector, which contains the translation initiation sequence (amino acids 1–76) of the glucocorticoid receptor fused to the DNA binding domain (amino acids 1–147) of the yeast Gal4 transcription factor in the pSG5 expression vector (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA) (33). cDNAs consisting of the ligand-binding domain (from Gly-Met-Met to C terminus) of mVDRα, mVDRβ, Xenopus VDR, lamprey VDR, and human VDR and flanked by restriction sites were amplified by PCR and ligated into the KpnI and HindIII sites of the multiple cloning site (MCS) within the XgalX expression vector generating plasmids mVDRαXgalX, mVDRβXgalX, xVDRXgalX, lVDRXgalX, and hVDRXgalX, respectively. The reporter plasmid (UAS)-tk-Luc was generated by insertion of five copies of a Gal4 DNA binding element into the NotI site of pGEM-Luc vector.

Full-length cDNAs for mVDRα and mVDRβ were subcloned into the pSG5 expression vector. cDNA encoding complete ORFs for medaka VDRα and VDRβ were PCR amplified and directionally cloned into the multiple cloning site of pSG5. mVDRαpCR2.1 plasmid DNA was digested using an incorporated BglII site, gel purified and ligated into the pSG5 MCS. mVDRβpCR2.1 plasmid DNA was digested using incorporated EcoRI and BglII sites, gel purified, and ligated into the pSG5 MCS. Two constructs, mVDRαpSG5 and mVDRβpSG5, were isolated, restriction mapped, and sequenced to ensure integrity and orientation of each cDNA within the expression vector. Both constructs consisted of the complete mVDR ORF including internal start and stop codons.

Spatial expression of mVDR

Total RNA was extracted from medaka organs (brain, gill, gut, heart, kidney, liver, ovary, skeletal muscle, spleen, and testis) using the RNA Bee reagent (Tel-Test) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Total RNA (800 ng) was reverse transcribed into cDNA using the high-capacity cDNA master kit (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) using random hexamer as primer. PCR (25 μl total volume) was performed on first-strand cDNAs and consisted of 1 μm of each primer and 1× GoTaq Green master mix (Promega). The PCR profile consisted of predenaturation at 95 C for 1 min, followed by 28 cycles of amplification (denaturation at 95 C for 30 sec, annealing at 60 C for 30 sec, and extension at 72 C for 20 sec) in a Thermal Cycler PTC 200 (MJ Research, Waltham, MA). PCR products were analyzed by using agarose gel electrophoresis. PCR products were cloned into the pCR2.1 vector (Invitrogen) and sequenced to verify the identity. A fragment of medaka 18S rRNA was amplified from the cDNA samples and used as an internal control for normalization of gene expression. Sequence-specific primers for RT-PCR were as follows: mVDRα forward, 5-AGCGGGAAGAGACTTTCTCCA-3′, mVDRα reverse, 5-CTCAAACGCTGCATCGACAT-3′, mVDRβ forward, 5′-CGATGAGTTTGACAGGAACG-3′, mVDRβ reverse, 5-AAGCTCACCGATGAACAGAG-3′, medaka 18S forward, 5′-CCTGCGGCTTAATTTGACTC-3′, medaka 18S reverse, 5′-GACAAATCGCTCCACCAACT-3′.

Functional studies of mVDR

Cell culture media and other necessary reagents were obtained from GibcoLife Technologies, Inc. (Carlsbad, CA). CV1 and HepG2 cells were cultured in T75 flasks with vented caps (Corning, Corning, NY) using MEM containing heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (10%), 1× sodium pyruvate, 1× MEM nonessential amino acids, and 1% penicillin/streptomycin. The cells were maintained following standard protocols in a 37 C-5% CO2 incubator and split when necessary (∼70–80% confluency, approximately every 4–5 d). PLHC-1 cells were cultured in flasks with plug caps (Corning) using Leibovitz’s L-15 CO2 independent medium containing heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (10%) and 100 μg/ml gentamicin. The cells were maintained following standard cell culture procedures in a 29 C incubator, using 1× trypsin-EDTA for splitting when necessary (∼80% confluency).

Gal4 cotransfection assays were conducted in CV-1 cells plated into 96-well plates and transiently transfected with 2 ng of mVDRαXGalX, mVDRβXGalX, xVDRXGalX, lVDRXGalX, or hVDRXGalX expression vector, 8 ng of the (UAS)-tk-SPAP reporter plasmid, 25 ng of pCH110 (Amersham Biosciences, Piscataway, NJ), 38 ng pBluescript II KS+ (Stratagene), and 7 ng of a human steroid receptor coactivator (SRC-1) construct (representing amino acids 1–1005) using Lipofectamine (Life Technologies) essentially according to the manufacturer’s instructions (34). Reporter gene expression was measured 24 h after addition of ligand and was normalized to pCH110 expression.

For functional comparison using full-length mVDRα and mVDRβ, 600 ng of either mVDRαpSG5 or mVDRβpSG5 was transiently transfected into either HepG2 or PLHC-1 cells with 100 ng either human CYP3A4-Luc reporter construct (XMRE) consisting of both proximal DR3 and distal ER6 response elements (35) or the human CYP24 promoter consisting of two imperfect DR3 type vitamin D response elements (VDREs) located between −140 and −300 bp upstream of the transcriptional start site of the human CYP24 gene (36). Ten nanograms of the normalizing plasmid containing Renilla luciferase (pRL-CMV; Promega) were also cotransfected. Cells were seeded at 2 × 105 cells/well 24 h before transfection and were transfected at 90–95% confluency for 6 h using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen; 2 μl per well) in serum-free media (Opti-MEM I reduced serum medium; GibcoLife Technologies) as per the manufacture’s recommendations. The cells were allowed to recover overnight in complete MEM, and the following day the media were replaced with complete MEM containing 1α,25(OH)2D3 (EMD Biosciences, San Diego, CA; 1.2–1200 nm) in dimethylsulfoxide (DMSO), or DMSO alone (<0.1% total solution). Twenty-four hours after exposure, the cells were lysed passively and tested for luciferase activity using the Promega dual-luciferase reporter assay system following the manufacturer’s protocols. Luciferase activities were measured using a DLReady TD 20/20 luminometer (Turner Biosystems, Sunnyvale, CA). Experiments were repeated at least twice, and all experiments were conducted as groups of four to six replicate wells.

Mammalian two hybrid

HepG2 cells were transfected with 633 ng luciferase reporter plasmid (5XGal4-TATA-Luc) containing binding sites for the yeast Gal4 transcription factor; 167 ng pMSRC-1 expression vector containing the SRC-1 cofactor nuclear receptor interaction domain fused to the yeast Gal4 DNA-binding domain; 167 ng mVDRαpVP16 or mVDRβpVP16 fusion plasmids containing full-length mVDRα or mVDRβ fused to the herpes simplex virus VP16 activation domain; and 33 ng pRL-CMV Renilla luciferase for transfection normalization. Controls consisted of transfections containing empty pM, pVP16 or both empty pM and pVP16 vectors. Cells were dosed with vehicle or 120 nm 1α,25(OH)2D3, and normalized luciferase activity was assayed to determine receptor-cofactor interactions. Cell culture conditions for HepG2s is as described in the functional assays. Experiments were performed in duplicate, and all assays were conducted as groups of four to six replicate wells.

Data mining and phylogenetic analysis

Ensembl Genome Browser (www.ensembl.org/index.html) was used to mine genome databases of human, salt water pufferfish (Takifugu rubripes), green pufferfish (Tetraodon nigroviridis), stickleback (Gasterosteus aculeatus), medaka (Oryzias latipes), and zebrafish (Danio rerio) to investigate the identity and location of unknown VDR gene sequences in teleosts. Additional VDR sequences were obtained through BLAST analysis of National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI; Bethesda, MD; www.ncbi.nih.gov/). Both human VDR and mVDRα were used as a query in all BLAST searches. Predicted protein sequences were identified for each database extracted and aligned using ClustalW via the SDSC Biology Workbench (http://workbench.sdsc.edu). Phylogenetic analyses were conducted using MEGA3.0 (http://www.megasoftware.net/mega.html) and the neighbor-joining trees were bootstrapped (500 pseudosamples) to assess robustness. The percentage of replicate trees in which the associated taxa clustered together in the bootstrap test is shown next to the branches.

Results

Sequence identification

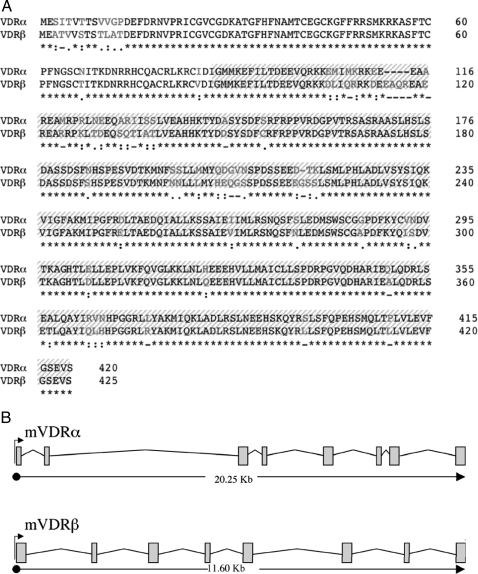

Through screening the medaka genome database, we identified two candidate VDR genes exhibiting a high degree of homology with human VDR used as our BLAST query. Analysis of gene organization and structure within the medaka genome demonstrated that VDR sequences represent two distinct gene paralogs each containing defined loci, intron-exon boundaries and 5′ UTRs within the medaka genome and are thus not isoforms of the same locus. VDRα was located on medaka chromosome 7 position 1,566,080–1,586,326 (+ direction) and VDRβ was found on chromosome 5 position 30,249,290–30,260885 (+ direction). Complete cDNA sequences and predicted translation products of each VDR are shown in Fig. 1A. Each gene contained a single ORF encoding a putative protein sequence of 420 (mVDRα) and 425 (mVDRβ) amino acids with a single ATG initiation codon, a single TAG termination signal, and a calculated molecular mass of 47.5 and 48.2 kDa, respectively. mVDRα/β paralogs shared 85.4% amino acid identity and exhibited 60 amino acid differences. Multiple nucleic acid substitutions were observed in the third base position, resulting in synonymous amino acid substitutions. Amino acid sequences for both mVDRα and mVDRβ displayed a high degree of homology in key regions representing conserved protein family domains including a 96% homology in the DNA binding domain (DBD) (PF00105), and 86% homology in the ligand-binding domain (LBD) (PF00104). Both genes contained a total of eight exons between translational start and stop sites consistent with intron-exon structure of mammalian VDR (Fig. 1B). 5′ noncoding exons were identified in both genes using 5′ rapid amplification of cDNA ends followed by BLAST analysis against the medaka genome. In both instances 5′ exons were located more than 5000 bp upstream of the transcriptional initiation site located on the proximal end of exon 2.

Figure 1.

mVDR sequences. A, Protein sequence for mVDRα (EU403115) and mVDRβ (EU403116). Amino acid differences between VDR paralogs are represented in light lettering. Consensus line denotes consensus (asterisk), similarity (: or.) or differences (-) between the mVDRα and mVDRβ. Shaded area represents sequence used in Gal4 functional studies. B, Intron/exon structure mVDRα and mVDRβ.

Homology

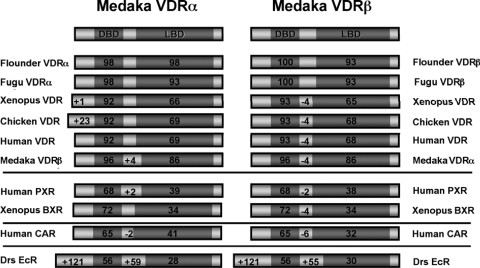

Mining of additional teleost genomes including Fugu, Tetraodon, stickleback, and zebrafish revealed the presence of duplicate (Fugu, tetraodon, stickleback) or multiple (zebrafish) VDR sequences. mVDRα and VDRβ proteins share between 95–86% total protein similarity with Fugu, Tetraodon, flounder, stickleback, and zebrafish α- and β-forms (Fig. 2). A higher degree of homology was present in the DBD, compared with the LBD. TBLASTX homology searches of the NCBI NR database indicated that mVDRα is most similar to flounder VDRα (95%) and mVDRβ is most similar to flounder VDRβ (95%), respectively. Teleost VDRα and VDRβ share on average 82% overall homology to their mammalian counterparts. Greatest homology, 94% is observed in the DBD and 81% in the LBD, whereas more variability was observed within the AF1, hinge, and AF2 regions. Outside the NR1I1 (VDR), medaka VDRα/β was most homologous to the NR1I2 [benzoate X receptor (BXR), pregnane X receptor (PXR)].

Figure 2.

Homology comparisons of mVDRα and mVDRβ to other VDRs. Comparison of mVDRα and mVDRβ amino acid sequence to Japanese flounder (Paralichthys olivaceus) VDRα (BAA95016), VDRβ (AB037673.1), Fugu VDRα (SINFRUPOOOOO153576), Fugu VDRβ (SINFRUPOOOOO154296), Xenopus VDR (NM_001085819), chicken Gallus gallus (NM_205098), human VDR (NP_000367), human PXR (AF061056), Xenopus BXR (NM_001098417.1), human CAR (NM_005122), and Drosophila ecdysone receptor EcR (NM_165461.1). Comparisons were made to functional protein domains including DBD and LBD. Homology between sequences is represented by indicated number/region for DBD and LBD. Differences in sequence length are represented by +/− for the A/B region or within the hinge region.

Phylogeny

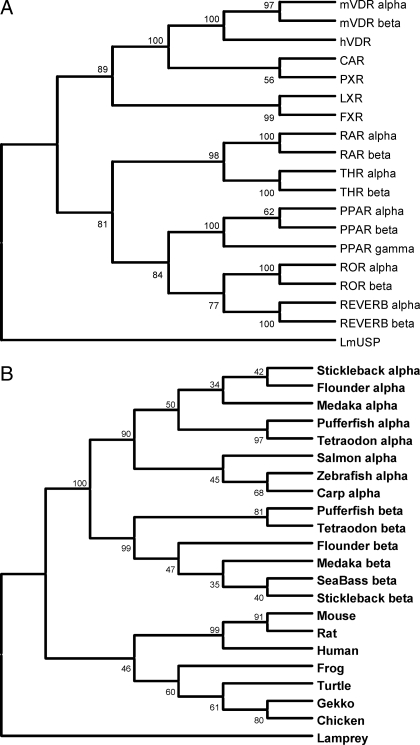

To test for orthology with mammalian NR sequences, we conducted phylogenetic comparisons of full-length mVDRα and mVDRβ with full-length human NR sequences of the NR1I subfamily consisting of VDR, PXR, and constitutive androstane receptor (CAR) (Fig. 3A). Both mVDRα and mVDRβ clustered within the NR1I subclade and exhibited closest phylogenetic similarity to human VDR. Additionally, we were able to identify duplicate VDR sequences in multiple teleosts by searching NCBI and individual genome databases. Comparisons of 22 VDR sequences (LBDs only) from several teleosts, rat, mouse, turtle, gecko, frog, and chicken illustrated distinct clusters of protein sequences consistent with speciation (Fig. 3B). Two distinct clusters were formed separating aquatic and terrestrial species. Nested within the teleost cluster were two separate clades for VDRα and VDRβ. Furthermore, separation occurred between mammalian and nonmammalian species within the tetrapod clade. Segregation and topology of teleost VDRα and VDRβ suggests that duplicate copies of VDR present in the fish genomes are more closely related than either to the tetrapod clade. It thus appears that that duplicate copies of VDR arose from a duplication event in the ray-finned fish lineage after the divergence of the tetrapods but before the teleost radiation. This is consistent with the fish-specific whole genome duplication event and further supports the notion that teleost VDRα and VDRβ are coorthologs of mammalian VDR.

Figure 3.

Phylogenetic analysis of mVDRs. A, Phylogenetic comparison of mVDRα and mVDRβ with members of human nuclear receptor subfamily 1 members NR1A (THRα, -β), NR1B (RARα, -β), NR1C [peroxisomal proliferator-activated receptor (PPAR)-α, -β, -γ], NR1D (REVERBα, -β) NR1F (RORα, -β), NR1H [farnesoid X receptor (FXR), liver X receptor (LXR)], and NR1I (VDR, PXR, CAR). The ultraspiracle receptor of Locusta migratoria (LmUSP) was used as an outgroup. B, Phylogenetic comparison of mVDRα and mVDRβ with identified VDR protein sequences for teleosts including stickleback, flounder, Fugu, Tetraodon, salmon, zebrafish, carp, and seabass; mouse; rat; human; frog; turtle; gecko; and chicken. Lamprey VDR was used an outgroup. Phylogenetic analyses were conducted in MEGA3. The phylogenetic analyses were inferred using the neighbor-joining trees and were bootstrapped (500 pseudosamples) to assess robustness. The percentage of replicate trees in which the associated taxa clustered together in the bootstrap test is illustrated next to the branches. The tree is drawn to scale, with branch lengths used to define evolutionary distances. THR, Thyroid receptor; RAR, retinoic acid receptor; REVERB, orphan; ROR, RAR-related orphan receptor.

VDR spatial distribution

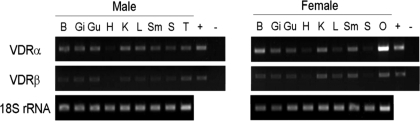

cDNA cloning revealed that both VDR sequences were expressed in medaka liver. Upon further examination, mVDRα and mVDRβ transcripts were identified in most adult tissues examined including brain, gill, gut, kidney, liver, skeletal muscle, spleen, testis, and ovary (Fig. 4). Expression for both mVDRα and mVDRβ was weak but present in heart. Qualitatively, mVDRα appears to exhibit stronger expression in most tissues than mVDRβ including testis and ovary. These findings suggest subfunctional partitioning for qualitative gene expression of these two receptor paralogs has occurred at the gross anatomical level. Interestingly, mVDRα and mVDRβ expression is extensive in the medaka liver, a finding distinctly different from than observed in tetrapods in which liver expression of VDR is relatively low. Additionally, little sexual dimorphic expression is observed between male and female medaka.

Figure 4.

Tissue distribution of mVDRα and mVDRβ mRNAs in adult Oryzias latipes. Representative agarose gel of RT-PCR products of medaka tissues including brain (B), gill (G), gut (G), heart (H), kidney (K), liver (L), skeletal muscle (Sm), spleen (S), testis (T), and ovary (O). mVDRα/B and medaka 18S rRNA-specific primers and amplification protocols are as described in Materials and Methods. Positive (+) control for mVDRα/β were conducted with 10 ng plasmid DNA for either mVDRαpCR2.1 or mVDRβpCR2.1. Negative controls (−) were conducted by amplifying VDRα with VDRβ-specific primers and VDRβ with VDRα-specific primers. The expression levels of VDRα and VDRβ are normalized against the 18S rRNA levels in each organ.

Functional activity

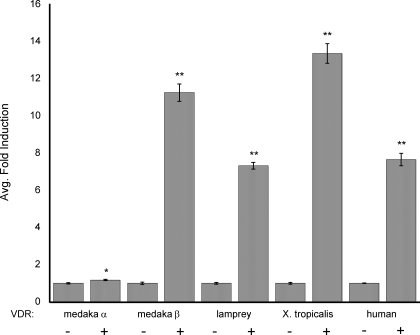

To ascertain functional information, we constructed chimeric proteins containing the yeast Gal4 DBD fused to the VDR LBD of either mVDRα or mVDRβ. A strong and specific response to 1α,25(OH)2D3 was observed with the medaka VDRβ chimera, exhibiting a 55-fold induction at 120 nm 1α,25(OH)2D3 (Fig. 5). This is similar in response to other species tested in our system that contain a single VDR ortholog including lamprey, Xenopus, and human (Fig. 5). Conversely, transactivation of medaka VDRα chimera was highly attenuated, displaying a maximum of 1.5-fold induction at 120 nm 1α,25(OH)2D3. These findings demonstrate a functional difference in ligand sensitivity between medaka VDR paralogs.

Figure 5.

Transactivation of Gal4 chimeric mVDRα and mVDRβ by 1α,25(OH)2D3. CV-1 cells were transiently transfected with 2 ng of medaka mVDRαXGalX, mVDRβXGalX, Xenopus xVDRXGalX, lamprey lVDRXGalX, or human hVDRXGalX expression vector, 8 ng of the (UAS)-tk-SPAP reporter plasmid, 25 ng of pCH110 (Amersham Biosciences), 38 ng pBluescript II KS+ (Stratagene), and 7 ng of a human SRC-1 construct (representing amino acids 1–1005) using Lipofectamine. Reporter gene expression was measured 24 h after addition of 120 nm 1α,25(OH)2D3 and normalized to pCH110 expression. Data are represented as the mean fold induction normalized to DMSO ± sem. Statistics performed using Statview 9.0 for Mac. Two-factor ANOVA indicated a significant effect of dose, VDR, and their interaction. ANOVA was followed with a Fisher’s protected least significant difference post hoc test. Only the significant differences between control and treated for each VDR are noted (significant differences between VDRs is not shown). *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.0001.

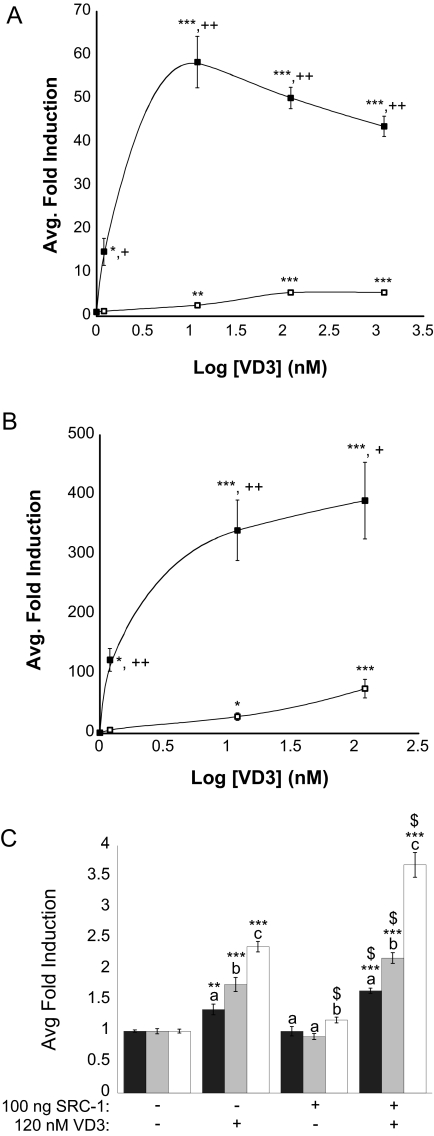

We also tested full-length mVDRs in transient transactivation assays to rule out that differences in VDR activity were due to fusion of Gal4 DBD and VDR LBD. These studies also aided in determining whether teleost VDR would interact with known mammalian VDREs. Experiments were conducted using expression vectors encoding full-length mVDRα and mVDRβ in the presence of a luciferase reporter construct for human CYP3A4 (XREM-Luc) (Fig. 6A) or human CYP24-Luc (Fig. 6B). The XREM-Luc construct contains two imperfect DR3/ER6 VDRE coupled to a luciferase reporter gene (35). The CYP24-Luc reporter contains a cluster of two imperfect DR3 type VDREs located between −140 and −300 bp upstream of the transcriptional start site of the human CYP24 gene (36). With XREM-Luc reporter and mVDRβ, the EC50 for 1α,25(OH)2D3 was 0.134 nm with a maximal induction of 56-fold at 12 nm. These findings are consistent with observed concentrations for well-characterized high-affinity-type mammalian VDRs. By comparison mVDRα exhibited an attenuated transactivation with an EC50 of 1.19 nm and a maximum induction of 5.6-fold at 120 nm 1α,25(OH)2D3 (Fig. 6A). For both mVDRα and mVDRβ, activity was substantially higher with the CYP24-Luc reporter construct. In these assays mVDRβ exhibited an EC50 of 0.354 nm with a maximum induction of 400-fold at 120 nm 1α,25(OH)2D3. Medaka VDRα, although still attenuated, reached a maximal induction at 120 nm 1α,25(OH)2D3 (68-fold) with an EC50 of 1.66 nm. Furthermore, it was observed that increasing 1α,25(OH)2D3 concentrations greater than 12 nm resulted in inhibition of activity (most dramatically with mVDRβ) in the XREM-Luc reporter system. This effect was not observed with the CYP24 reporter between 1.2 and 120 nm 1α,25(OH)2D3.

Figure 6.

Transactivation of full-length mVDRα and mVDRβ by 1α,25(OH)2D3. HepG2 cells were transiently transfected with pRL-CMV, XREM-Luc (A) or CYP24-Luc (B) and either mVDRαpSG5 (open squares) or mVDRβpSG5 (closed squares) as described previously in Materials and Methods. Cells were exposed to 1α,25(OH)2D3 between 0.12 and 1200 nm in media for 24 h. Medaka VDR response was measured via dual-luciferase assays. Data are represented as the mean fold induction normalized to control (DMSO) ± sem. Statistics performed using Statview 9.0 for Mac (SAS Institute, Cary, NC). A two-factor global ANOVA for each graph found a significant effect of dose (P < 0.0001), receptor (P < 0.0001), and their interaction (P < 0.0001). The ANOVAs were followed with Fisher’s protected least significant difference (PLSD) post hoc test. Asterisks represent a significant difference in response, compared with receptor-matched control. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.0001. Plus signs represent a significant difference in response between receptors at a single dose (+, P < 0.01; ++, P < 0.0001). C, Activation of human and mVDRs is attenuated in a fish hepatocarcinoma cell line. PLHC-1 cells were transiently transfected with pRL-CMV; XREM-Luc; VDRαpSG5 (dark gray), VDRβpSG5 (light gray), or hVDRpSG5 (white); and differing amounts of SRC-1 (0 or 100 ng) as described previously for HepG2 cells in 24-well plates. Cells were exposed to DMSO or 120 nm 1α,25(OH)2D3 in media for 24 h. VDR response was measured via dual-luciferase assays as previously mentioned. Data were normalized to activity at 0 ng SRC-1 in the absence of agonist for each VDR tested. Statistics performed using Statview 9.0 for Mac (SAS Institute). A three-factor global ANOVA was performed and a significant effect of dose, receptor, SRC-1 addition, and their interaction noted. The ANOVA was followed with Fisher’s PLSD post hoc test. A significant effect of dose was noted for all three VDRs. **, P < 0.01; ***, P ≤ 0.0001. A significant difference in VDR activity was also found for each data set (denoted by letters, P < 0.05). Dollar signs ($) represent a significant difference in response, compared with 0 ng SRC-1 for each VDR (P < 0.05).

Transactivation of mVDRα and mVDRβ in fish hepatocarcinoma (PLHC-1 Poeciliopsis lucida) cells resulted in a similar trend in sensitivities to 1α,25(OH)2D3 as observed in HepG2 cells (Fig. 6C). These results demonstrate that the observed functional difference between mVDRα and mVDRβ is not restricted to cell type or reporter plasmid. Differences in sensitivity between these two paralogs are likely due to amino acid substitutions similar to that observed with trout GR paralogs (10) and not an artifact of expression of teleost proteins in a mammalian cellular environment. Transactivation of mVDRα and mVDRβ in addition to human VDR in PLHC-1 cells was dramatically less responsive that that observed in HepG2 cells. The attenuated response is most likely due to limited expression of NR coregulators in this cell line as addition of SRC-1 significantly increased activity.

All assays were optimized by titrating medaka VDRα/β constructs, XREM-Luc or CYP24-Luc reporter, pRL-CMV (Renilla luciferase), and transfection reagent (Lipofectamine 2000; Invitrogen).

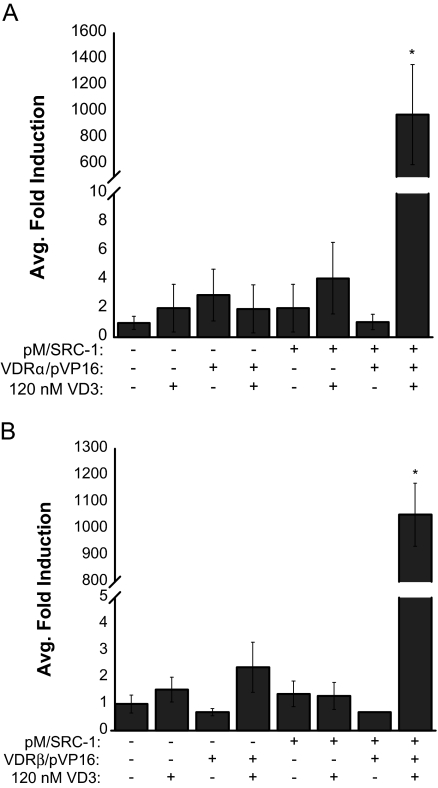

Coactivator interaction

Next, we investigated the ability of mVDRα and mVDRβ to recruit the NR coactivator SRC-1 in the presence of ligand using the mammalian two-hybrid assay. Cultures of HepG2 cells were transiently transfected with expression vector encoding VP16-mVDR (either mVDRαpVP16 or mVDRβpVP16) chimeras and an expression vector encoding the receptor interaction domain of SRC-1 fused to the Gal4 DBD (pMSRC-1) together with the Gal4 luciferase reporter construct (5XGal4-TATA-Luc). The transfections were normalized by cotransfection of pRLCMV (Renilla luciferase) as previously described in functional assays. As demonstrated in Fig. 7, the presence of 120 nm 1α,25(OH)2D3 was highly effective and necessary for recruiting both medaka VDRα/VDRβ-SRC-1 interaction. Activity was ligand specific with little activity observed in the vehicle control or with empty vector controls. These data demonstrate that mVDRα/β can be driven to interact with SRC-1 in coactivator overexpressed conditions.

Figure 7.

Mammalian two-hybrid assay with mVDRα/β and SRC-1. HepG2 cells were transiently transfected with pRL-CMV and 5XGal4-TATA-Luc, pMSRC-1, and either mVDRα or mVDRβ pVP16 fusion constructs. Cells were exposed to DMSO (−) or 120 nm 1α,25(OH)2D3 (+) in media for 24 h. VDR response was measured via dual-luciferase assays as described earlier. Data are represented as the mean fold induction of VDRα/β normalized to control (DMSO, empty pM, empty pVP16, first bar of A and B) ± sem. Statistics performed using Statview 9.0 for Mac (SAS Institute). A two-factor global ANOVA for each graph found a significant effect of dose, plasmids present, and their interaction on average fold induction for both mVDRα (dose, P < 0.01; plasmids, P = 0.0001; interaction, P = 0.0001) and mVDRβ (dose, P < 0.001; plasmids, P < 0.0001; interaction, P < 0.0001). The ANOVAs were then followed by Fisher’s protected least significant difference post hoc test. Asterisks represent a significant difference in response, compared with control (P < 0.001).

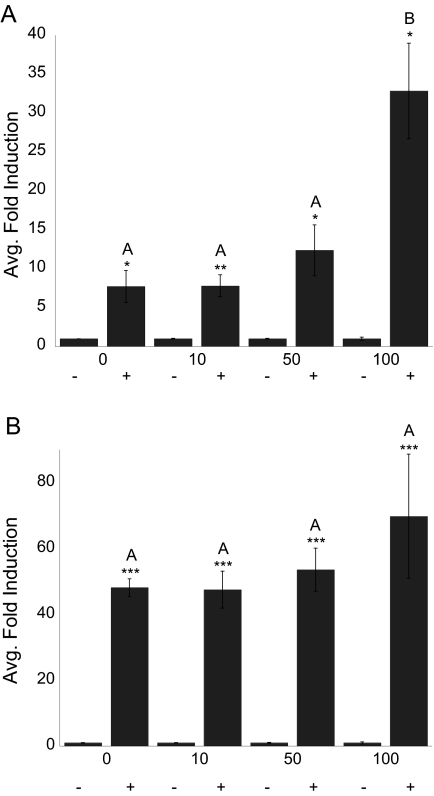

To confirm results, SRC-1 was titrated into transfections containing medaka VDR, XMRE-Luc, and Renilla luciferase (Fig. 8). With mVDRα, addition of SRC-1 between 1 and 100 ng resulted in greater than 4-fold increase in reporter activity in the presence of 120 nm 1α,25(OH)2D3. Conversely, mVDRβ activity was increased 1.3-fold at a maximal titration of 100 ng. A significant effect of SRC-1 concentration (to corresponding DMSO control) was found for both mVDRα and mVDRβ between 0 and 100 ng SRC-1 (P < 0.0001). However, change in activity was significant only with mVDRα after addition of 100 ng SRC-1 (P < 0.0001). No significant effect was found for mVDRβ. Similar results were observed in PLHC-1 cells after titration of SRC-1 (Fig. 6C). For both mVDR paralogs, change in activity was observed only in the presence of ligand, suggesting that the holo-protein is in an active configuration capable of attracting coactivators and mediating gene transcription. A small but significant increase in hVDR activity but not mVDR was observed upon SRC-1 addition in the absence of agonist in PLHC-1 cells.

Figure 8.

Titration of SRC-1. HepG2 cells were transiently transfected with pRL-CMV; XREM-Luc; either mVDRαpSG5 (A) or mVDRβpSG5 (B); and SRC-1 (0–100 ng). Cells were exposed to DMSO (−) or 120 nm 1α,25(OH)2D3 (+) in media for 24 h. VDR response was measured via dual-luciferase assays. Data are represented as the mean fold induction of mVDR normalized to control (DMSO) ± sem. Statistics performed using Statview 9.0 for Mac. A two-factor global ANOVA was performed for each graph. A significant effect of dose, SRC-1 addition, and their interaction was observed for mVDRα. For mVDRβ, only a significant effect of dose was observed. ANOVAs were followed with Fisher’s protected least significant difference post hoc test. Asterisks represent a significant difference in response, compared with control for each concentration of SRC-1. *, P < 0.01; **, P < 0.001; ***, P < 0.0001. The letters in Fig. 7A represent differences between amounts of SRC-1 transfected at 120 nm 1α,25(OH)2D3. Bars connected by the same letter are not statistically different from each other (P > 0.05).

Discussion

Using both comparative genomics and conventional molecular approaches, our laboratory has developed methodologies to screen, clone, and assess molecular function of several NR classes in teleost fish. Our comparative approach encompasses the use of several established genomic databases for teleosts such as medaka, pufferfish (Tetraodon and Takifugu), stickleback, and zebrafish. These databases greatly facilitate the isolation of orthologous genes via the assumption that phylogenetically distant organisms retain gene sequence and structural similarities. We mined these genomic databases for putative NRs using the highly conserved P box domain (containing two zinc fingers) of the NR DBD as a probe. Through this process we identified NRs from several receptor classes including but not limited to NR1I (VDR/PXR), NR1C (peroxisomal proliferator-activated receptor-α, -β/∂, -γ), NR2B (retinoid X receptor), NR1H (farnesoid X receptor/liver X receptor), and others. The diversity and structural similarity of NRs found in these species suggest that these regulatory proteins are well conserved throughout vertebrate evolution and share a common protein organization (9). Interestingly, several paralogs of specific receptor types are present in teleosts, consistent with the notion of genome duplications. In the case of VDR, identification of a second VDR gene paralogous to and separate from VDRα suggests that this receptor represents a novel subfamily of ligand-binding proteins within the vertebrate NR1I family.

In the fish species examined (previously mentioned), all have been shown to contain VDRα and -β forms. Medaka VDRα and VDRβ have been mapped to distinct genomic locations and exhibit unique intronic organization, demonstrating defined allelic positions within the genome. These results indicate that the two copies are not isoforms of the same gene locus and thus unlikely to have originated by tandem gene duplication. Furthermore, identification and phylogeny of paralogous VDRs from several teleosts examined to date supports the notion that these gene pairs are a result of a genome duplication event before teleost radiation.

In numerous instances, teleosts have two or more copies of single-copy mammalian genes (see recent review in Ref. 37). However, there is still significant debate whether increased copy number is due to whole genome duplications or reflects multiple independent local duplication events. Gene duplicates have several possible fates. The classical model of gene duplication assumes redundancy in gene function(s) after duplication, with relaxed selection often resulting in deleterious mutations, pseudogene formation, and eventual nonfunctionalization of one member of the pair (38). When nonfunctionalization does not occur, the classical model has gene duplicates maintained by mutation, fixation, and positive selection resulting in neofunctionalization. In this scenario, one copy acquires a new protein activity, whereas the second copy maintains the original function (38,39). In a third model, Force et al. (382) proposed that gene duplicates are maintained by subfunctionalization as a consequence of duplication-degeneration-complementation. In subfunctionalization, deleterious mutations result in the simultaneous decay of specific regulatory regions or coding sequence of each gene copy. This decay means that the ancestral gene function(s) cannot be retained unless both gene copies are retained. Subfunctionalization occurs rapidly and often gene pairs undergo subsequent independent evolutionary events resulting in eventual neofunctionalization, a process termed subneofunctionalization (40,41). Subfunctionalization is thought to be the dominant mechanism for maintenance of most gene duplicates in teleosts (38,39,42). The phylogenetic timing of the fish-specific genome duplication (FSGD) and the radiation of teleosts subsequent to this event provide suggestive evidence that each of these processes may have contributed to the physiological plasticity, specification, and evolutionary diversification of these organisms (15,16).

To date, neither the molecular function nor physiological significance of multiple teleost VDRs has been elucidated. Studies based solely on structural similarities may speculate on molecular behavior and physiological function of orthologous and paralogous genes. However, assumption of function based solely on protein sequence without further characterization may be hasty. As an example, our work with medaka VDR in transcriptional activation assays demonstrated unique ligand activation activities. To ascertain functional information, we constructed chimeric proteins containing the yeast Gal4 DBD fused to the VDR LBD of either mVDRα or mVDRβ. Unexpected results were obtained using these constructs. Activity of the mVDRα chimera exhibited little activation with 1α,25(OH)2D3, the primary ligand for VDR in mammals. At a concentrations as high as 1200 nm 1α,25(OH)2D3 activity remained low with a maximal induction of less than 1.5-fold. By comparison, a strong and specific response to 1α,25(OH)2D3 was observed with the mVDRβ chimera, suggesting that considerable functional divergence has occurred between these two NR paralogs. Interestingly, induction of mVDRβ was similar to other species tested in our system, which have a single VDR ortholog including lamprey, Xenopus, and human. Comparison of amino acid composition between mVDRα and mVDRβ show that these two proteins retain a high degree of similarity within both the DBD and LBD, demonstrating that slight changes in amino acid composition may be associated with the differences in transactivation. To confirm these results, similar studies were conducted using full-length (entire protein) mVDRα and mVDRβ constructs with luciferase reporters for human CYP3A4 (XREM) or CYP24. Both reporter constructs contain multiple imperfect VDREs (35,36). Under these conditions dose response for mVDRβ demonstrated a maximal fold induction of 56 and 400 at 12 and 120 nm 1α,25(OH)2D3, respectively. By comparison mVDRα exhibited a maximum of 5.6- and 68-fold activation at 120 nm 1α,25(OH)2D3.

To determine whether the attenuated response of mVDRα was due to the altered protein-protein interactions, we tested the hypothesis that VDRα activity could be increased upon interaction with SRC-1, a primary coregulator associated with VDR activation. Mammalian two-hybrid assays were conducted to investigate whether 1α,25(OH)2D3 could facilitate interaction between mVDRα/β and SRC-1. Interestingly, both mVDRα and mVDRβ displayed significant interaction with SRC-1, and no discernible difference was observed between the two NR paralogs in this assay. Titration of 100 ng SRC-1 in the presence of 120 nm 1α,25(OH)2D3, resulted in greater than 4-fold increase in reporter activity for mVDRα, whereas mVDRβ activity was increased only 1.3-fold. This response was consistent across cell lines occurring in both mammalian (HepG2) and teleost (PLHC-1) cells.

Based on these data, we hypothesize that both mVDR paralogs are functional NRs capable of DNA binding, ligand binding, heterodimerization with retinoid X receptor, and coactivator recruitment. Given the structural and phylogenetic similarities of mVDRs to their mammalian counterparts, we began our investigations with the assumption that ligand-transactivated behaviors would recapitulate those observed in mammals. Whereas we have demonstrated that mVDRβ exhibits a high sensitivity for 1α,25(OH)2D3, it appears that this ligand is relatively ineffective for activation of mVDRα. Given that the mVDRα paralog is active and VDRα duplicates are present in all teleost species examined to date, we assume that this receptor is functional and its retention serves a distinct physiological purpose. With 1α,25(OH)2D3 as a ligand, it appears that mVDRα retains partial functionality, suggesting a divergence from its original activity (i.e. sub- or neofunctionalization). This applies, however, only if we assume that ancestral VDR served to mediate the actions of 1α,25(OH)2D3. This appears to be a fair assumption given the identification of VDR and its ligand 1α,25(OH)2D3 in lamprey (22), a species that is more distantly related to teleosts than are tetrapods. However, in a recent study, it has been demonstrated that VDR from a more distant Urochordate Ciona intestinalis (sea squirt) is nonfunctional with 1α,25(OH)2D3 as a ligand. This suggests an ancient VDR function distinct from interaction with 1α,25(OH)2D3 (24).

The precedent for sub- and neofunctionalization of NRs after gene duplication has been established for several subclasses including NR3C (10,43), NR1B (44), NR5A (12), and AhR (11). Whereas the origins and evolution of Deuterstome NRs is still highly debated (9,45,46), complex phylogenetic analysis of vertebrate NRs indicates that many teleost NR paralogs arose through serial gene duplication events followed by modification in gene expression and in some instances gene function (47). An example of this phenomenon is the theory that teleost corticosteroid receptors can be traced back to an ancestral steroid receptor present in primitive agnathan vertebrates. A series of multiple (at least two) genome duplication events produced two glucocorticoid receptor (GRs) and a single mineralocorticoid receptor with divergent function(s) in extant teleosts (48). This is likely due to mutations in the ancestral corticosteroid receptor ligand binding and regulatory domains, which altered the substrate specificities and transcriptional activation resulting in neofunctionalization, novel gene function, and divergence in endocrine signaling. Retention of a single mineralocorticoid receptor and duplicate copies of GR are consistent across teleost taxa implying a conserved mechanism(s) for physiological diversification. This may be particularly true in trout in which GR paralogs exhibit defined transactivation and transrepression activities (10,48). However, this difference in activity is not ubiquitously observed in all teleost GR paralogs (43). Similarly, gene duplication events have affected both expression and ligand-binding specificity of retinoic acid receptors (RARs), which play a major role in chordate embryonic development (44). Whereas it appears that RARβ has retained an ancestral RAR function, neofunctionalization of both RARα and RARγ have resulted in novel receptor activities.

Thus, we believe that medaka (and possibly teleost) VDRs represent nuclear receptors in transition. Possible scenarios for VDR gene paralogs in medaka include: mVDRα has acquired deleterious mutations, resulting in a gradual and eventual loss of functionality; mVDRα acquired beneficial mutations, resulting in novel receptor function(s) that are yet to be characterized; the partial inactivity of mVDRα is due to quantitative subfunctional partitioning of mVDRα and mVDRβ with complementary activities that fulfill the ancestral gene function(s); and/or, mVDRα maintains the ancestral function (not yet known) whereas lamprey, teleost VDRβ, and tetrapod VDRs have diverged, resulting in a high-affinity nuclear receptor for 1α,25(OH)2D3 through neofunctionalization. Our plans for investigating rates of VDR evolution, gene synteny, and phylogenetics will help elucidate both the ancestral function and evolutionary fate of these gene paralogs.

Whereas the molecular mechanisms of mammalian NRs are now actively being investigated, far less is known regarding those of aquatic vertebrates. The divergent activity of medaka VDRα and VDRβ with 1α,25(OH)2D3 is of great interest given the consistency of VDR and NR duplication through several teleost genomes. Given the theory of sub- and neofunctionalization, we are intrigued by the possibility of a functional and physiological divergence between VDR and other NR paralogs in lower vertebrates.

Acknowledgments

We thank Pei-Jen Chen, Michael Carney, and Dhyanesh Doshi for assistance with fish culture and maintenance; Dr. Donald McDonnell (Duke University) for mammalian two-hybrid reagents; Dr. Kerr Whitfield (University of Arizona-Tucson) for the lamprey VDR; and Dr. Frank Conlon (University of North Carolina-Chapel Hill) for Xenopus liver RNA. We also thank the laboratory of Dr. Patrick Casey (Duke University) for use of their luminometer.

Footnotes

This work was supported in part by Grant R21CA106084-01A1 from the National Cancer Institute, the Duke University Integrated Toxicology and Environmental Health Program (T32 ES07031), North Carolina Biotechnology Center Grant ARG0030, Mount Desert Island Biological Laboratory Center for Membrane Toxicity Studies (National Institutes of Health/National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences Grant P30 ES03828), and U.S. Environmental Protection Agency Science to Achieve Results (STAR) Graduate Fellowship Grant FP91642701 (to D.L.H.).

Disclosure Statement: D.L.H., S.H.W.L., B.B., D.E.H., and S.W.K. have nothing to declare. J.M.H. is currently employed by The Hamner Institutes for Health Sciences. L.M., J.M.M., and J.T.M. are currently employed by GlaxoSmithKline Discovery Research.

First Published Online February 7, 2008

Abbreviations: BXR, Benzoate X receptor; CAR, constitutive androstane receptor; DBD, DNA binding domain; DMSO, dimethylsulfoxide; GR, glucocorticoid receptor; LBD, ligand binding domain; m, medaka; MCS, multiple cloning site; NR, nuclear receptor; 1α,25(OH)2D3, 1α,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3; ORF, open reading frame; PXR/SXR, pregnane X receptor; RAR, retinoic acid receptor; SRC, steroid receptor coactivator; UTR, untranslated region; VDR, vitamin D receptor; VDRE, vitamin D response element.

References

- Willson TM, Moore JT 2002 Genomics versus orphan nuclear receptors—a half-time report. Mol Endocrinol 16:1135–1144 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gronemeyer H, Gustafsson JA, Laudet V 2004 Principles for modulation of the nuclear receptor superfamily. Nat Rev Drug Discov 3:950–964 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maglich JM, Caravella JA, Lambert MH, Willson TM, Moore JT, Ramamurthy L 2003 The first completed genome sequence from a teleost fish (Fugu rubripes) adds significant diversity to the nuclear receptor superfamily. Nucleic Acids Res 31:4051–4058 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Metpally RP, Vigneshwar R, Sowdhamini R 2007 Genome inventory and analysis of nuclear hormone receptors in Tetraodon nigroviridis. J Biosci 32:43–50 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Venkatesh B, Yap WH 2005 Comparative genomics using fugu: a tool for the identification of conserved vertebrate cis-regulatory elements. Bioessays 27:100–107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor JS, Van de Peer Y, Braasch I, Meyer A 2001 Comparative genomics provides evidence for an ancient genome duplication event in fish. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 356:1661–1679 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hedges SB, Kumar S 2002 Genomics vertebrate genomes compared. Science 297:1283–1285 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lynch M, Force A 2000 The probability of duplicate gene preservation by subfunctionalization. Genetics 154:459–473 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertrand S, Brunet F, Escriva H, Parmentier G, Laudet V, Robinson-Rechavi M 2004 Evolutionary genomics of nuclear receptors: from twenty-five ancestral genes to derived endocrine systems. Mol Biol Evol 21:1923–1937 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bury NR, Sturm A, Le Rouzic P, Lethimonier C, Ducouret B, Guiguen Y, Robinson-Rechavi M, Laudet V, Rafestin-Oblin ME, Prunet P 2003 Evidence for two distinct functional glucocorticoid receptors in teleost fish. J Mol Endocrinol 31:141–156 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hahn ME, Karchner SI, Evans BR, Franks DG, Merson RR, Lapseritis JM 2006 Unexpected diversity of aryl hydrocarbon receptors in non-mammalian vertebrates: insights from comparative genomics. J Exp Zoolog A Comp Exp Biol 305:693–706 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuo MW, Postlethwait J, Lee WC, Lou SW, Chan WK, Chung BC 2005 Gene duplication, gene loss and evolution of expression domains in the vertebrate nuclear receptor NR5A (Ftz-F1) family. Biochem J 389:19–26 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoegg S, Brinkmann H, Taylor JS, Meyer A 2004 Phylogenetic timing of the fish-specific genome duplication correlates with the diversification of teleost fish. J Mol Evol 59:190–203 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volff JN 2005 Genome evolution and biodiversity in teleost fish. Heredity 94:280–294 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohno S 1999 Gene duplication and the uniqueness of vertebrate genomes circa 1970–1999. Semin Cell Dev Biol 10:517–522 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor JS, Raes J 2004 Duplication and divergence: the evolution of new genes and old ideas. Annu Rev Genet 38:615–643 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burmester JK, Wiese RJ, Maeda N, DeLuca HF 1988 Structure and regulation of the rat 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 receptor. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 85:9499–9502 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDonnell DP, Mangelsdorf DJ, Pike JW, Haussler MR, O’Malley BW 1987 Molecular cloning of complementary DNA encoding the avian receptor for vitamin D. Science 235:1214–1217 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin R, White JH 2004 The pleiotropic actions of vitamin D. Bioessays 26:21–28 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sutton AL, MacDonald PN 2003 Vitamin D: more than a “bone-a-fide” hormone. Mol Endocrinol 17:777–791 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dusso AS, Brown AJ, Slatopolsky E 2005 Vitamin D. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 289:F8–F28 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitfield GK, Dang HTL, Schluter SF, Bernstein RM, Bunag T, Manzon LA, Hsieh G, Dominguez CE, Youson JH, Haussler MR, Marchalonis JJ 2003 Cloning of a functional vitamin D receptor from the lamprey (Petromyzon marinus), an ancient vertebrate lacking a calcified skeleton and teeth. Endocrinology 144:2704–2716 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dehal P, Satou Y, Campbell RK, Chapman J, Degnan B, De Tomaso A, Davidson B, Di Gregorio A, Gelpke M, Goodstein DM, Harafuji N, Hastings KEM, Ho I, Hotta K, Huang W, Kawashima T, Lemaire P, Martinez D, Meinertzhagen IA, Necula S, Nonaka M, Putnam N, Rash S, Saiga H, Satake M, Terry A, Yamada L, Wang HG, Awazu S, Azumi K, Boore J, Branno M, Chin-bow S, DeSantis R, Doyle S, Francina P, Keys DN, Haga S, Hayashi H, Hino K, Imai KS, Kano S, Kobayashi K, Kobayashi M, Lee BI, Makabe KW, Manohar C, Matassi G, Medina M, Mochizuki Y, Mount S, Morishita T, Miura S, Nakayama A, Nishizaka S, Nomoto H, Ohta F, Oishi K, Rigoutsos I, Sano M, Sasaki A, Sasakura Y, Shoguchi E, Shin-i T, Spagnuolo A, Stainier D, Suzuki MM, Tassy O, Takatori N, Tokuoka M, Yagi K, Yoshizaki F, Wada S, Zhang C, Hyatt PD, Larimer F, Detter C, Doggett N, Galvina T, Hawkins T, Richardson P, Lucas S, Kohara Y, Levine M, Satoh N, Rokhsar DS 2002 The draft genome of Ciona intestinalis: insights into vertebrate origins. Science 298:2157–2167 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reschly EJ, Bainy AC, Mattos JJ, Hagey LR, Bahary N, Mada SR, Ou J, Venkataramanan R, Krasowski MD 2007 Functional evolution of the vitamin D and pregnane X receptors. BMC Evol Biol 7:222 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holick MF 2003 Evolution and function of vitamin D. Recent Results Cancer Res 164:3–28 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holick MF 2003 Vitamin D: a millennium perspective. J Cell Biochem 88:296–307 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rao DS, Raghuramulu N 1999 Vitamin D3 and its metabolites have no role in calcium and phosphorus metabolism in Tilapia mossambica. J Nutr Sci Vitaminol (Tokyo) 45:9–19 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rao DS, Raghuramulu N 1999 Is vitamin D redundant in an aquatic habitat? J Nutr Sci Vitaminol (Tokyo) 45:1–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Power DM, Ingleton PM, Clark MS 2002 Application of comparative genomics in fish endocrinology. Int Rev Cytol 221:149–190 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nemere I, Larsson D, Sundell K 2000 A specific binding moiety for 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D(3) in basal lateral membranes of carp enterocytes. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 279:E614–E621 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larsson D, Nemere I, Aksnes L, Sundell K 2003 Environmental salinity regulates receptor expression, cellular effects, and circulating levels of two antagonizing hormones, 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 and 24,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3, in rainbow trout. Endocrinology 144:559–566 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li YC, Bergwitz C, Juppner H, Demay MB 1997 Cloning and characterization of the vitamin D receptor from Xenopus laevis. Endocrinology 138:2347–2353 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehmann JM, Moore LB, Smith-Oliver TA, Wilkison WO, Willson TM, Kliewer SA 1995 An antidiabetic thiazolidinedione is a high affinity ligand for peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ (PPARγ). J Biol Chem 270:12953–12956 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore LB, Maglich JM McKee DD, Wisely B, Willson TM, Kliewer SA, Lambert MH, Moore JT 2002 Pregnane X receptor (PXR), constitutive androstane receptor (CAR), and benzoate X receptor (BXR) define three pharmacologically distinct classes of nuclear receptors. Mol Endocrinol 16:977–986 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drocourt L, Pascussi JM, Assenat E, Fabre JM, Maurel P, Vilarem MJ 2001 Calcium channel modulators of the dihydropyridine family are human pregnane X receptor activators and inducers of CYP3A, CYP2B, and CYP2C in human hepatocytes. Drug Metab Dispos 29:1325–1331 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen, KS, DeLuca, HF 1995 Cloning of the human 1α,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 24-hydroxylase gene promoter and identification of two vitamin D-responsive elements. Biochim Biophys Acta 1263:1–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Postlethwait JH 2007 The zebrafish genome in context: ohnologs gone missing. J Exp Zoolog B Mol Dev Evol 308:563–577 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Force A, Lynch M, Pickett FB, Amores A, Yan YL, Postlethwait J 1999 Preservation of duplicate genes by complementary, degenerative mutations. Genetics 151:1531–1545 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Postlethwait J, Amores A, Cresko W, Singer A, Yan YL 2004 Subfunction partitioning, the teleost radiation and the annotation of the human genome. Trends Genet 20:481–490 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He X, Zhang J 2005 Rapid subfunctionalization accompanied by prolonged and substantial neofunctionalization in duplicate gene evolution. Genetics 169:1157–1164 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rastogi S, Liberles DA 2005 Subfunctionalization of duplicated genes as a transition state to neofunctionalization. BMC Evol Biol 5:28 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinke D, Salzburger W, Braasch I, Meyer A 2006 Many genes in fish have species-specific asymmetric rates of molecular evolution. BMC Genomics 7:20 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenwood AK, Butler PC, White RB, DeMarco U, Pearce D, Fernald RD 2003 Multiple corticosteroid receptors in a teleost fish: distinct sequences, expression patterns, and transcriptional activities. Endocrinology 144:4226–4236 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Escriva H, Bertrand S, Germain P, Robinson-Rechavi M, Umbhauer M, Cartry J, Duffraisse M, Holland L, Gronemeyer H, Laudet V 2006 Neofunctionalization in vertebrates: the example of retinoic acid receptors. PLoS Genet 2:e102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thornton JW 2001 Evolution of vertebrate steroid receptors from an ancestral estrogen receptor by ligand exploitation and serial genome expansions. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 98:5671–5676 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Escrivá García H, Laudet V, Robinson-Rechavi M 2003 Nuclear receptors are markers of animal genome evolution. J Struct Funct Genomics 3:177–184 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crow KD, Wagner GP 2006 What is the role of genome duplication in the evolution of complexity and diversity? Mol Biol Evol 23:887–892 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bury NR, Sturm A 2007 Evolution of the corticosteroid receptor signaling pathway in fish. Gen Comp Endocrinol 153:47–56 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]