Abstract

Objectives/Hypothesis

Closure of the true and false vocal folds is a normal part of airway protection during swallowing. Individuals with reduced or delayed true vocal fold closure can be at risk for aspiration and benefit from intervention to ameliorate the problem. Surface electrical stimulation is currently used during therapy for dysphagia, despite limited knowledge of its physiological effects.

Design

Prospective single effects study.

Methods

The immediate physiological effect of surface stimulation on true vocal fold angle was examined at rest in 27 healthy adults using ten different electrode placements on the submental and neck regions. Fiberoptic nasolaryngoscopic recordings during passive inspiration were used to measure change in true vocal fold angle with stimulation.

Results

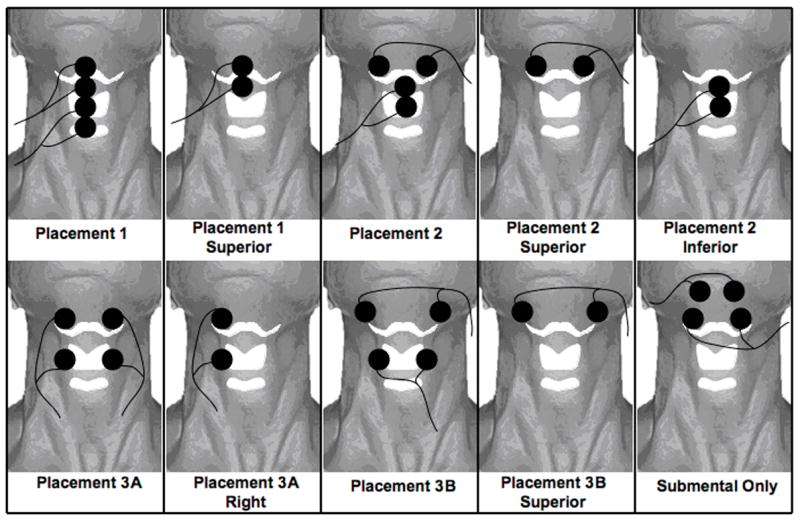

Vocal fold angles changed only to a small extent during two electrode placements (p ≤ 0.05). When two sets of electrodes were placed vertically on the neck the mean true vocal fold abduction was 2.4 degrees; while horizontal placements of electrodes in the submental region produced a mean adduction of 2.8 degrees (p=0.03).

Conclusions

Surface electrical stimulation to the submental and neck regions does not produce immediate true vocal fold adduction adequate for airway protection during swallowing and one position may produce a slight increase in true vocal fold opening.

Keywords: dysphagia, true vocal fold paralysis, swallowing, aspiration, therapy

INTRODUCTION

Swallowing is a complex function that requires rapid hyo-laryngeal elevation and closure of the true and false (ventricular) vocal folds to prevent penetration, the entry of food or liquid into the laryngeal vestibule to the level of the vocal folds, and aspiration, the entry of food or liquid into the trachea. When central nervous system disorders or surgical procedures causing neurological or anatomical changes interfere with upper airway control producing swallowing problems, individuals may be at increased risk for penetration and aspiration. Many patients with dysphagia who aspirate exhibit some type of true vocal fold movement dysfunction1–3. Laryngeal closure during swallowing normally occurs at multiple levels to protect the airway including true and false vocal fold closure, arytenoid approximation and epiglottic inversion 4–6. True vocal fold closure depends upon activation of the laryngeal adductor muscles: the lateral cricoarytenoid, thyroarytenoid and interarytenoid muscles7–9. Reduced or delayed true vocal fold closure has been treated with vocal fold augmentation using silastic, Gortex, or injectable implants, medialization thyroplasty and/or arytenoid adduction. Recurrent nerve anastomosis has been used to maintain intrinsic laryngeal muscle tone10–13. Others have introduced an implantable device to stimulate the laryngeal nerves that may reduce the occurrence of aspiration in post-stroke patients14.

With the recent introduction of surface electrical stimulation for dysphagia therapy 15, transcutaneous stimulation of the submental and neck regions is used during swallowing therapy while the patient is encouraged to increase their per oral intake16 Developers of this treatment have claimed that such stimulation can assist with true vocal fold closure during swallowing16 (page 27). Although true vocal fold adduction can be induced with chronic electrode implantation in the thyroarytenoid muscle in the dog17 and with temporary insertion of hooked wires in humans18, surface stimulation may not be capable of inducing true vocal fold adduction because the intrinsic laryngeal muscles lie deep to the strap muscles in the neck. We have recently shown that surface stimulation in the submental and neck regions significantly lowers the hyoid bone in the neck both in patients with dysphagia19 and in normal volunteers20. These studies suggested that the sternohyoid muscles are activated with surface stimulation but it is unknown whether or not the intrinsic laryngeal muscles are activated with such stimulation. Because surface stimulation is less invasive and less costly than surgical implantation of intramuscular or nerve cuff stimulators, if surface stimulation can produce vocal fold adduction, it might be a valuable method for improving airway protection in patients with dysphagia. The purpose of this study was to determine if surface electrical stimulation produces true vocal fold closure when applied in healthy adults at therapeutic levels during passive breathing.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Participants

The NINDS Institutional Review Board approved the study and each participant gave written consent to participate. Male and female healthy volunteers between the ages of 20 and 60 without neurological, psychiatric, speech or voice, hearing or swallowing disorders were recruited for study. Prior to inclusion, all volunteers were examined by an otolaryngologist (K.G.S or P.R.K) using nasolaryngoscopy to exclude persons with structural and/or movement disorders affecting the upper airway or true or false vocal folds. Individuals who were pregnant, breast-feeding, had cardiac irregularities, or a history of rheumatic fever were excluded. Some participants were also in a previous study using videofluoroscopy to evaluate the effects of surface stimulation on the position of the hyoid and larynx in the neck 20.

Procedures

The thickness of participants’ adipose tissue was measured in the submental and laryngeal regions using a caliper (Lange Skinfold Caliper, Beta Technology Incorporated, Santa Cruz, CA). The electrical stimulation unit used (VitalStim®, Chattanooga Group, Chattanooga, TN) is limited to an 80 Hz pulse rate with a biphasic pulse duration of 700 microseconds. The current amplitude of two bipolar electrode stimulation channels can be independently adjusted between 0 and 25 microamperes (mA). The skin in the submental and laryngeal regions was cleaned with alcohol and wiped with a TENS Clean-Cote® Skin Wipe (Tyco Uni-Patch Model UP220) before placing two pairs of bipolar surface electrodes on the skin. All male participants were clean-shaven to improve electrode contact. Surface electrodes (VitalStim®, adult sized, REF 59000) with a 2.1 cm diameter and an active surface area of 3.46 cm2 were used with a Chin-Neck Bandage (Caromed model 1-8006) fitted over the electrodes to ensure continuous contact.

Ten electrode placements were used (Figure 1). After electrode placement the stimulation intensity for for each pair was raised gradually in 0.5 mA steps together until the participant could first feel a tingling sensation. Next, the stimulation intensity was further increased until the participant reported a tugging sensation. Finally, the intensity on each channel was increased until the participant indicated that any further increase would become uncomfortable, thus designating the maximum tolerance level. The maximum tolerance level, or “grabbing sensation”, was used for study of each placement for electrical stimulation as instructed in the “Training Manual for Patient Assessment and Treatment Using VitalStim™ Electrical Stimulation”16 (page 105).

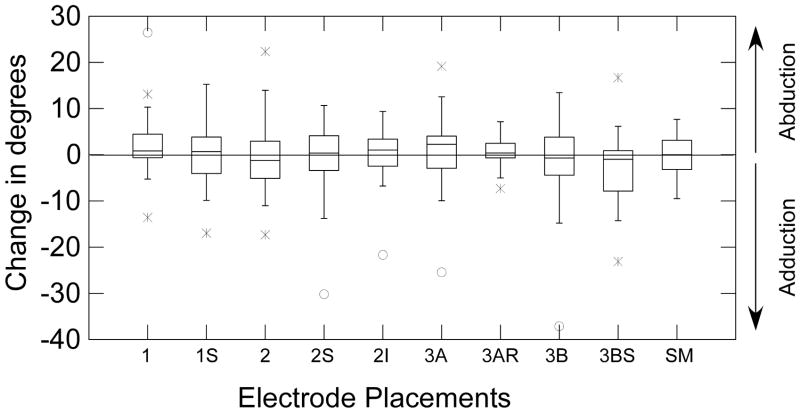

Figure 1.

The electrode positions relative to the hyoid bone, thyroid cartilage, and cricoid cartilage. The bipolar electrode pairs for each placement are connected by lead wires (solid lines) with current flowing between the two electrodes of each pair. Placement 1, 2, 3A, and 3B have electrodes in both the submental and laryngeal regions. Placements 1 superior, 2 superior, 2 inferior, 3A right, and 3B superior are individual electrode pairs. The submental-only placement has two electrode pairs above the hyoid bone in the submental region.

Four electrode placements involved two sets of bipolar electrodes in the submental and laryngeal regions (placements 1, 2, 3A, and 3B) (Figure 1). Each of these placements were in the VitalStim™ training manual16 (pages 106–109). The bipolar pairs were vertically arranged for placements 1 and 3A, horizontally arranged for placement 3B, and both vertically and horizontally arranged for placement 2. The next five placements (1 superior, 2 superior, 2 inferior, 3A right and 3B superior) used one pair of electrode placements from the four combined electrode placements (1,2, 3A and 3B). The submental-only placement included two horizontally arranged pairs of electrodes (one pair anterior and medial and the other more lateral and posterior) (Figure 1).

Groups (A, B, and C) included placements that shared the same electrode locations: Group A included placements 1, 1 superior, 2, 2 superior, and 2 inferior; Group B included 3B and 3B superior; and, Group C included 3A, 3A right and the submental-only placement. The placements were randomly ordered within their group (A, B or C). Two group orders were randomly ordered among participants (A, B, then C; or C, B, then A). Group B always occurred between Groups A and C because it shared electrode placement with both groups.

Participants were familiarized with the sensation of stimulation before the study to reduce extraneous movement in response to stimulation onset. They were instructed to remain still, with their jaw closed to prevent jaw opening due to stimulation of the anterior belly of the digastric in the submental region. After nasal administration of a decongestant without topical anesthesia, a Pentax FNL-10RP3 flexible naso-pharyngo-laryngoscope (Pentax Medical Company, Montvale, New Jersey) was passed by an otolaryngologist through the nasal cavity to below the epiglottis to visualize the larynx. Because the true vocal folds partially abduct and adduct during quiet respiration on inspiration and expiration respectively, volunteers were instructed to slowly and gently inhale prior to, during and after stimulation so that each trial occurred within the same respiratory phase. Volunteers were asked not to produce voice, throat clears, or coughing during a trial. Before stimulation they were asked to initiate a slow gentle inspiration to prevent a startle response, which could produce a protective true vocal fold adduction. The tip of the nasolaryngoscope was then repositioned to provide a similar image of the true vocal folds so that the entire angle between the two folds was visible on the videoscreen. Stimulation was applied for approximately 3 seconds at rest while nasoendoscopy was used to record true vocal fold movement. The endoscopic laryngeal image, along with a time stamp, was recorded on a Super VHS videocassette recorder (Panasonic) at the National Television Standards Committee (NTSC) standard frame rate of about 30 frames (60 fields) per second.

The stimulator automatically cycles on for 59 seconds and off for 1 second. To allow the experimenter to control stimulation during nasolaryngoscopy, a custom-built switch box was used to interrupt the flow of current between the controller box and the pairs of electrodes, except when the experimenter pressed the button.

Data Analysis

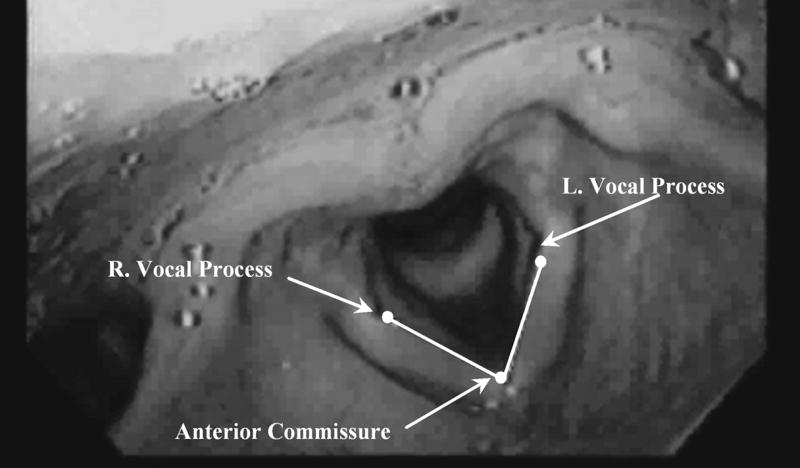

Because of possible movement of the tip of the nasolaryngoscope from the glottis during the study, it was not possible to accurately measure the distance in millimeters between the true vocal folds as a measure of vocal fold adduction and abduction. Therefore we measured change in vocal fold angle between the two folds with stimulation from the videonasolaryngoscopic recordings (Figure 2) because vocal fold angle does not vary with a change in distance between the tip of the nasolaryngoscope and the true vocal folds. The video recordings were digitized using a frame grabber board and Peak Performance Image Processing (ViconPeak, Centennial, CO 80112) version 8.2 for kinematic analysis. The stimulation onset and offset frame counter time stamps were noted for each trial. The right vocal process, anterior commissure, and left vocal process were marked and two lines were drawn, one between the anterior commissure and the right arytenoid and the other between the anterior commissure and the left arytenoid (Figure 2). The angle formed between the two lines at the anterior commissure was measured in degrees using Peak Performance Image Processing Software on each field recorded before and during stimulation from a trial. The mean angle between the true vocal folds prior to stimulation and during stimulation was calculated by averaging 400 ms (or 25 fields) immediately before stimulation onset and another 400 ms (25 fields) during stimulation. The 400 ms measured during stimulation began 250 ms after the first frame of stimulation to allow the true vocal folds to reach their maximum displacement angle. Angle change (in degrees) was computed by subtracting the non-stimulation period mean angle from the stimulation period mean angle. Negative scores indicated vocal fold adduction with stimulation while positive scores indicated vocal fold abduction.

Figure 2.

The true vocal folds visualized with a nasolaryngoscope from a superior view. Placement of measurement points on the anterior commissure, right and left vocal processes, along with interconnecting lines denoting the true vocal fold abduction angle are shown.

Statistical Analysis

To determine measurement reliability, 67 trials, evenly distributed across the 10 different electrode placements, were re-analyzed for intra-rater reliability. Intraclass Correlation Coefficients (ICC) were computed for angle change for each placement using only the repeated sets of 67 ratings for measuring intra-rater reliability. The ICC is a standard measure of inter-rater reliability with values near 1 indicating nearly perfect inter-rater agreement, while values near 0 indicating very poor agreement21. ICC values were computed for each placement.

Our purpose was to determine if surface stimulation could reduce the true vocal fold abduction angle from rest to provide airway protection as is claimed by the developers. This hypothesis was tested for each placement using single group t-tests to determine if the change scores were less than zero, indicating true vocal fold adduction with stimulation and if they were greater than zero, indicating true vocal fold abduction. We also examined whether age, submental and laryngeal region fat caliper measures, and stimulation amplitudes were related to change in vocal fold angle with stimulation for each placement by computing the Pearson Correlation Coefficients. Finally, in a previous study20 we had reported that many electrode placements for surface electrical stimulation lowered the hyoid and larynx in the neck. Thus, for each placement, we tested whether the amount of hyoid descent, laryngeal descent or anterior movement of the hyoid during stimulation measured in the previous study was related to change in true vocal fold angle in this study in those persons who participated in both studies (N=25), by computing Pearson Correlation Coefficients. To correct for five tests of correlation for each stimulation placement measure of angle change, we used a Bonferroni corrected p=0.05/7=0.007.

RESULTS

Thirty-eight volunteers were consented to participate and 27 volunteers completed the study (mean age 39.2, range 23–57) (Table I). Eleven volunteers were excluded because of an inability to tolerate laryngoscopy and/or electrical stimulation, abnormal true vocal fold function on nasolaryngoscopy or an abnormal echocardiogram during screening for inclusion. The mean maximum tolerated stimulation level across placements and participants was 8.0 mA (SD 3.8) (Table II).

Table I.

Mean age, stimulation amplitude (in milliAmperes) and caliper measures in the submental and laryngeal regions for the entire group and for subdivisions of the group based on age and sex.

| Group | N | Age | Stimulation Amplitude (mA) | Stimulation Amplitude (SD*) | Caliper Measures (SM/L†) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All | 27.0 | 39.2 | 8.0 | 3.8 | 10.1/6.1 |

| Males | 13.0 | 40.9 | 8.6 | 4.4 | 10.6/6.0 |

| Females | 14.0 | 37.6 | 7.4 | 3.0 | 9.6/6.1 |

| Younger Males (20–39 years) | 6.0 | 29.8 | 8.8 | 4.8 | 10.5/5.8 |

| Older Males (40–60 years) | 7.0 | 47.3 | 8.4 | 4.0 | 10.8/6.2 |

| Younger Females (20–39 years) | 7.0 | 29.1 | 6.2 | 2.0 | 7.6/4.3 |

| Older Females (40–60 years) | 7.0 | 46.1 | 8.5 | 3.3 | 11.6/7.9 |

Standard Deviation

Submental/Laryngeal

Table II.

Mean Stimulation Amplitudes (mA) for all Subjects for each Electrode Placement

| Placement | Range | Mean | SD* |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2.5–12.5 | 7.6 | 2.8 |

| 1 Superior | 2.5–19 | 7.9 | 4.0 |

| 2 | 3–16.5 | 7.5 | 3.2 |

| 2 Superior | 4.5–25 | 9.1 | 5.2 |

| 2 Inferior | 4–16.5 | 8.6 | 3.6 |

| 3A | 3.0–15 | 7.0 | 3.0 |

| 3A Right | 4.0–18 | 8.2 | 3.5 |

| 3B | 3.0–14 | 6.6 | 2.7 |

| 3B Superior | 4.5–23 | 9.4 | 4.5 |

| Submental-Only | 2.5–18.5 | 7.7 | 4.1 |

| All | 2.5–25 | 8.0 | 3.8 |

Standard Deviation

The ICC measures of intra-rater reliability were greater than 0.98 for each of the electrode placements except placement 2S, (ICC=0.76), and placement 3A right (ICC= 0.27). An examination of the individual angle change scores for position 2S indicated that the mean angle change was small (~1.1 degrees) making measurement variation large relative to the angle change. For placement 3A right the mean angle change was small (0.8 degrees) on this variable, which also made the ICC values low.

Only stimulation using the 3BS electrode placement produced a significant reduction in vocal fold angle during the study (t=−1.953, p= 0.031) (Figure 3); no significant vocal fold adductions with stimulation were observed for any of the other placements. The mean reduction in the vocal fold angle with placement 3BS was only 2.8 degrees from a mean resting vocal fold angle of 59.20 degrees, a 4.7 % decrease in opening angle. With placement 1, an unexpected increase in true vocal fold angle yielded a t value of 1.801 and a p= 0.042 when the change scores were tested for being greater than zero (Figure 3). However, the mean angle change was 2.3 degrees producing an increase in opening of 3.9 % from the resting mean angle of 60.9 degrees. Therefore, neither the true vocal fold closing during placement 3BS, nor the opening during placement 1 was clinically meaningful.

Figure 3.

The box plot distributions of change in vocal fold angle during stimulation at rest by electrode placement. The first and second quartiles are shown in boxes with the median (line) separating them. The third and fourth quartiles are shown as lines extending from each end of the boxes. Data above zero indicate abduction and data below indicate adduction.

Other factors (stimulation amplitude, subject age, submental and laryngeal caliper measures) were examined for relationships with the change in vocal fold angle for each placement using Pearson Correlation Coefficients. In addition, we examined whether changes in true vocal fold angle with stimulation in each of the placements were related to the amount of hyoid descent/elevation and anterior motion and the amount of larynx descent/elevation when measured from videofluoroscopy20 in participants in both studies (N = 25). None of these correlations coefficients were significant (Bonferroni corrected p=0.05/7=0.007). Therefore neither hyoid nor laryngeal movements was related to changes in vocal fold position during surface stimulation.

DISCUSSION

We examined the immediate physiological effects of surface electrical stimulation on vocal fold angle in healthy adults at rest. Only minimal changes were found; a slight closing with placement 3BS and a slight opening with placement 1. We found that electrical current from surface electrodes does not activate the intrinsic laryngeal muscles to produce true vocal fold movement. To stimulate the laryngeal muscles involved in true vocal fold closure (the thyroarytenoid, lateral cricoarytenoid and interarytenoid), current must pass through the skin, adipose tissue, platysma, strap muscles (omohyoid, sternohyoid, sternothyroid and thyrohyoid) and the thyroid cartilage, to depolarize axons leading to in the laryngeal muscles. These results demonstrate that surface stimulation on the neck and in the submnetal region cannot produce immediate vocal fold closure to assist patients who are at risk of aspiration because of lack of true vocal fold closure. Therefore, surface electrical stimulation is unlikely to be beneficial for patients with laryngeal dysfunction during swallowing

In two previous studies employing videofluoroscopy we evaluated the effects of surface stimulation on hyoid and laryngeal position at rest and during swallowing in healthy adults and patients using the same device 19,20. We found significant hyoid bone descent in both dysphagic and healthy individuals as well as laryngeal descent in healthy adults during surface stimulation. Thus surface stimulation likely activated the omohyoid, sternohyoid and sternothyroid muscles, which depress the hyoid/larynx. There was no evidence that the thyrohyoid muscle, which raises the larynx to the hyoid, was stimulated. Likely, the thyrohyoid is too deep to be stimulated or if it was stimulated, simultaneous stimulation of the omohyoid and sternohyoid muscles would act to depress the hyoid and overcome any laryngeal elevation by thyrohyoid contraction. Other studies using surface stimulation overlying the laryngeal region in the neck 15,22, did not measure the physiological effects of stimulation.

On the other hand, when hooked wire electrodes were directly inserted into the thyrohyoid muscles, bypassing the strap muscles, and used for stimulation, the thyroid cartilage was elevated 8.90mm (±5.50 mm), in healthy males 23 In addition hooked wire electrodes inserted into the thyroarytenoid muscles were effective in closing the folds when used in patients with spasmodic dysphonia18. Therefore, surface stimulation cannot achieve the same results as intramuscular stimulation for either true vocal fold closure or hyo-laryngeal elevation, which are both important for airway protection during swallowing.

Maximum tolerated stimulation levels were used in this and previous studies. Persons with dysphagia tolerated mean current levels of 13 mA during surface stimulation19 while healthy individuals tolerated 8.2 mA20 and 8.0 mA in the current study. Certainly using higher stimulation levels might change the true vocal fold angle, however, those levels of stimulation were already shown to produce significant hyoid and laryngeal descent which interfered with swallowing safety in healthy volunteers20. Any increase in current levels in an attempt to produce true vocal fold closure would be beyond participant tolerance, detrimental to hyo-laryngeal elevation, and interfere with swallowing.

In normal swallowing, the larynx moves anteriorly and superiorly while simultaneously closing6,7. As a result, true vocal fold closure cannot be considered separate from hyo-laryngeal antero-superior movement during swallowing as both can provide airway protection. Persons with dysphagia can have both inadequate laryngeal elevation and/or incompetent laryngeal closure3. Patients with reduced laryngeal closure who undergo surface stimulation may be put at increased risk of aspiration due to stimulation induced hyo-laryngeal depression during swallowing. With the larynx pulled to a lower position because of stimulation, patients with reduced laryngeal closure will have even less defense from aspiration.

We excluded adults above 60 years of age because of possible laryngeal denervation in this population24, therefore results from this study cannot be generalized to these older populations, however, such persons would have less vocal fold movement in response to surface stimulation because of muscle denervation. In addition, only participants who could tolerate the combination of nasolaryngoscopy and electrical stimulation could be included in the study, therefore results do not adequately represent healthy individuals who are more sensitive to these procedures. Possibly, persons who were not disturbed by these techniques may also have reduced protective true vocal fold movement induced by the laryngoscope and/or stimulation. There was a wide range of tolerated stimulation levels that likely increased the variability of the results. However, we did not find any trends in vocal fold movement related to stimulation level in our statistical analyses.

CONCLUSION

To our knowledge, this is the first study that has examined the effects of surface stimulation on vocal fold movement in healthy adults at rest. Surface stimulation is an attractive method for treating dysphagia because it is much less invasive and less costly than other approaches. However, we conclude that surface electrical stimulation to the skin overlying the submental and laryngeal regions does not cause significant movement of the true vocal folds and is unlikely to be beneficial in patients with dysphagia due to reduced vocal fold closure. Further, because the hyoid and larynx descend with surface stimulation 19,20 such patients could be put at increased risk for aspiration with this procedure. These findings contrast with the results of intramuscular laryngeal muscle stimulation18, which is effective for producing vocal fold closure.

Acknowledgments

Source of Financial Support: This work was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke.

Footnotes

All work for this research was performed at Laryngeal and Speech Section, 10 Center Drive MSC 1416, National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, Bethesda, Maryland 20892

References

- 1.Bhattacharyya N, Kotz T, Shapiro J. Dysphagia and aspiration with unilateral vocal cord immobility: incidence, characterization, and response to surgical treatment. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 2002;111:672–679. doi: 10.1177/000348940211100803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Leder SB, Ross DA. Incidence of vocal fold immobility in patients with dysphagia. Dysphagia. 2005;20:163–167. doi: 10.1007/s10350-005-0002-4. discussion 168–169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lundy DS, Smith C, Colangelo L, et al. Aspiration: cause and implications. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1999;120:474–478. doi: 10.1053/hn.1999.v120.a91765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ardran GM, Kemp FH. Closure and opening of the larynx during swallowing. Br J Radiol. 1956;29:205–208. doi: 10.1259/0007-1285-29-340-205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ardran GM, Kemp FH. The protection of the laryngeal airway during swallowing. Br J Radiol. 1952;25:406–416. doi: 10.1259/0007-1285-25-296-406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Logemann JA, Kahrilas PJ, Cheng J, et al. Closure mechanisms of laryngeal vestibule during swallow. Am J Physiol. 1992;262:G338–G344. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1992.262.2.G338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kawasaki A, Fukuda H, Shiotani A, Kanzaki J. Study of movements of individual structures of the larynx during swallowing. Auris Nasus Larynx. 2001;28:75–84. doi: 10.1016/s0385-8146(00)00087-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Perlman AL, Palmer PM, McCulloch TM, Vandaele DJ. Electromyographic activity from human laryngeal, pharyngeal, and submental muscles during swallowing. J Appl Physiol. 1999;86:1663–1669. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1999.86.5.1663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shaker R, Dodds WJ, Dantas RO, Hogan WJ, Arndorfer RC. Coordination of deglutitive glottic closure with oropharyngeal swallowing. Gastroenterology. 1990;98:1478–1484. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(90)91078-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mahieu HF, Schutte HK. New surgical techniques for voice improvement. Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 1989;246:397–402. doi: 10.1007/BF00463605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hoffman H, McCabe D, McCulloch T, Jin SM, Karnell M. Laryngeal collagen injection as an adjunct to medialization laryngoplasty. Laryngoscope. 2002;112:1407–1413. doi: 10.1097/00005537-200208000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brondbo K, Jacobsen E, Gjellan M, Refsum H. Recurrent nerve/ansa cervicalis nerve anastomosis: a treatment alternative in unilateral recurrent nerve paralysis. Acta Otolaryngol (Stockh) 1992;112:353–357. doi: 10.1080/00016489.1992.11665432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Flint PW, Purcell LL, Cummings CW. Pathophysiology and indications for medialization thyroplasty in patients with dysphagia and aspiration. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1997;116:349–354. doi: 10.1016/S0194-59989770272-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Broniatowski M, Grundfest-Broniatowski S, Tyler DJ, et al. Dynamic laryngotracheal closure for aspiration: a preliminary report. Laryngoscope. 2001;111:2032–2040. doi: 10.1097/00005537-200111000-00031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Freed ML, Freed L, Chatburn RL, Christian M. Electrical stimulation for swallowing disorders caused by stroke. Respir Care. 2001;46:466–474. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wijting Y, Freed ML. VitalStim Therapy Training Manual. Hixson, TN: Chattanooga Group; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ludlow CL, Bielamowicz S, Daniels Rosenberg M, et al. Chronic intermittent stimulation of the thyroarytenoid muscle maintains dynamic control of glottal adduction. Muscle Nerve. 2000;23:44–57. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-4598(200001)23:1<44::aid-mus6>3.0.co;2-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bidus KA, Thomas GR, Ludlow CL. Effects of adductor muscle stimulation on speech in abductor spasmodic dysphonia. Laryngoscope. 2000;110:1943–1949. doi: 10.1097/00005537-200011000-00033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ludlow CL, Humbert I, Saxon K, Poletto C, Sonies B, Crujido L. Effects of surface electrical stimulation both at rest and during swallowing in chronic pharyngeal dysphagia. Dysphagia. 2007;22:1–10. doi: 10.1007/s00455-006-9029-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Humbert IA, Poletto CJ, Saxon KG, et al. The effect of surface electrical stimulation on hyo-laryngeal movement in normal individuals at rest and during swallowing. J Appl Physiol. 2006;101:1657–1663. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00348.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fleiss JL. The design and analysis of clinical experiments. New York, NY: John Wiley & Sons, Inc; 1999. pp. 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Leelamanit V, Limsakul C, Geater A. Synchronized electrical stimulation in treating pharyngeal dysphagia. Laryngoscope. 2002;112:2204–2210. doi: 10.1097/00005537-200212000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Burnett TA, Mann EA, Cornell SA, Ludlow CL. Laryngeal elevation achieved by neuromuscular stimulation at rest. J Appl Physiol. 2003;94:128–134. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00406.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Takeda N, Thomas GR, Ludlow CL. Aging effects on motor units in the human thyroarytenoid muscle. Laryngoscope. 2000;110:1018–1025. doi: 10.1097/00005537-200006000-00025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]