Abstract

Rapid activation of phospholipase D (PLD), which hydrolyzes membrane lipids to generate phosphatidic acid (PA), occurs under various hyperosmotic conditions, including salinity and water deficiency. The Arabidopsis thaliana PLD family has 12 members, and the function of PLD activation in hyperosmotic stress responses has remained elusive. Here, we show that knockout (KO) and overexpression (OE) of previously uncharacterized PLDα3 alter plant response to salinity and water deficit. PLDα3 uses multiple phospholipids as substrates with distinguishable preferences, and alterations of PLDα3 result in changes in PA level and membrane lipid composition. PLDα3-KO plants display increased sensitivities to salinity and water deficiency and also tend to induce abscisic acid–responsive genes more readily than wild-type plants, whereas PLDα3-OE plants have decreased sensitivities. In addition, PLDα3-KO plants flower later than wild-type plants in slightly dry conditions, whereas PLDα3-OE plants flower earlier. These data suggest that PLDα3 positively mediates plant responses to hyperosmotic stresses and that increased PLDα3 expression and associated lipid changes promote root growth, flowering, and stress avoidance.

INTRODUCTION

Hyperosmotic stress is characterized by decreased turgor pressure and water availability. Terrestrial plants frequently experience hyperosmotic stress under growth conditions that include high salinity and water deficit. In many regions, drought is the determinant for crop harvest, and nearly one-fifth of irrigated land worldwide is affected by high-salinity stress (Szaboles, 1997). Complex changes in gene expression, cellular metabolism, and growth patterns occur in plants in response to hyperosmotic stresses (Zhu, 2002; Bray, 2004). Several classes of regulatory components, including plant hormones, transcription factors, protein kinases, and Ca2+, have been identified as mediating plant responses to salinity and water deficit (Jonak et al., 2002; Zhu, 2002; Fujita et al., 2006). Despite great progress being made toward understanding the abiotic stress signaling pathways, little is known about the process by which hyperosmotic stress is sensed at cell membranes and transduced into physiological responses (Chinnusamy et al., 2004; Fujita et al., 2006).

Cell membranes play key roles in stress perception and signal transduction. Increasing results indicate that membrane lipids are rich sources for signaling messengers in plant responses to hyperosmotic stresses (Wang, 2004; Testerink and Munnik, 2005; Wang et al., 2006). In particular, phospholipase D (PLD), which hydrolyzes membrane lipids to generate phosphatidic acid (PA) and a free head group, is activated in Arabidopsis thaliana in response to various hyperosmotic stresses, such as high salinity (Testerink and Munnik 2005), dehydration (Katagiri et al., 2001), and freezing (Welti et al., 2002; Li et al., 2004), as well as abscisic acid (ABA), a phytohormone regulating plant water homeostasis (Zhang et al., 2004). In addition, PLD-produced PA increases rapidly in cell suspension cultures of tomato (Solanum lycopersicum) and alfalfa (Medicago sativa) subjected to salt stress and in dehydrated leaves of the resurrection plant (Craterostigma plantagineum) (Frank et al., 2000; Munnik et al., 2000). The changes in PLD activity, expression, and PA formation under these conditions imply a role for PLD in response to salinity and other hyperosmotic stresses. However, the physiological effects of PLD-mediated signaling and the identity of specific PLD(s) involved in plant responses to salinity and water deficiency remain to be determined.

Arabidopsis has 12 identified PLDs that are classified into six types, PLDα (3), -β (2), -γ (3), -δ, -ɛ, and -ζ (2) (Qin and Wang, 2002; Wang, 2005). Several PLDs have been implicated in specific physiological processes. PLDα1 is the most abundant PLD in Arabidopsis tissues and is also more extensively characterized than other PLDs. PLDα1 deficiency renders plants insensitive to ABA in the induction of stomatal closure (Zhang et al., 2004; Mishra et al., 2006). PLDα1-derived PA binds to ABI1, a negative regulator of ABA signaling, to regulate water loss through stomata. PLDα1 also interacts with the plant Gα protein through its DRY motif (Zhao and Wang, 2004). PLDδ is involved in freezing tolerance (Li et al., 2004) and dehydration-induced PA formation (Katagiri et al., 2001). PLDζ1 and -ζ2 are involved in plant responses to phosphate deficiency (Cruz-Ramirez et al., 2006; Li et al., 2006), and PLDζ2 is also part of the auxin response (Li and Xue, 2007). The above distinct physiological effects resulting from the loss of one PLD indicate that individual PLDs have specific functions (Wang et al., 2006). However, except for PLDα1, which has a role in the ABA regulation of stomatal movement and water loss, none of the characterized PLD mutants exhibit an overt phenotype under conditions of high salinity or drought.

The PLDα group has three members; PLDα1 and -α2 are very similar, sharing ∼93% similarity in deduced amino acid sequences, whereas PLDα3 is more distantly related to the other PLDαs, sharing 70% amino acid sequence similarity to each of the other two PLDαs. The coding region of PLDα3 contains three introns, whereas the coding regions of PLDα1 and PLDα2 are interrupted by two introns (Qin and Wang, 2002). This study was undertaken to characterize the biochemical properties and metabolic and physiological functions of PLDα3. The results show that manipulations of PLDα3 alter plant responses to hyperosmotic stress and indicate that PLDα3 positively mediates plant responses to hyperosmotic stress.

RESULTS

Expression, Reaction Conditions, and Substrate Usage of PLDα3

Arabidopsis EST database searches revealed a number of EST clones corresponding to PLDα1, but none for PLDα3, indicating that the level of PLDα3 expression is much lower than that of PLDα1. This is supported by quantitative real-time PCR data showing that the average level of PLDα3 expression in buds, flowers, siliques, stems, old leaves, and roots is ∼1000-fold lower than that of PLDα1. Otherwise, the expression patterns in the different organs were similar between the two PLD genes (Figure 1A). These results are consistent with the expression levels and patterns of PLDα1 and PLDα3 expression in different organs as determined by querying GENEVESTIGATOR (https://www.genevestigator.ethz.ch).

Figure 1.

PLDα3 Expression, Reaction Conditions, and Substrate Specificity.

(A) Expression of PLDα3 and -α1 in Arabidopsis tissues, as quantified by real-time PCR normalized to Ubiquitin10 (UBQ10). Values are means ± sd (n = 3 separate samples).

(B) Production of HA-tagged PLDα3 in Arabidopsis wild-type plants. Leaf proteins extracted from PLDα3-HA transgenic plants were separated by 8% SDS-PAGE and transferred to a polyvinylidene difluoride membrane. PLDα3-HA was visualized by alkaline phosphatase conjugated to secondary anti-mouse antibody after blotting with HA antibody. Lanes 1 through 5 represent different transgenic lines carrying the PLDα3-HA overexpression construct.

(C) PLDα3 activity under PLDα1, -β, -δ, and -ζ1 assay conditions. PLDα3-HA protein was expressed and purified from Arabidopsis leaves using HA antibody affinity immunoprecipitation and was subjected to PLDα3 activity assays under PLDα1, -β, -δ, and -ζ1 reaction conditions using dipalmitoylglycero-3-phospho-(methyl-3H) choline as a substrate. Values are means ± sd (n = 3) of three independent experiments.

(D) Quantification of the hydrolytic activity of PLDα3 toward 12-(7-nitro-2-1,3-benzoxadiazol-4-yl)amino PC, PE, PG, and PS. The lipid spots on thin layer chromatography plates corresponding to substrates (PC, PE, PG, and PS) and product (PA) were scraped, and the lipids were extracted for fluorescence measurement (excitation at 460 nm, emission at 534 nm). Vector is a negative control that refers to reactions using HA antibody immunoprecipitates from proteins of empty vector–transformed Arabidopsis plants. Values are means ± sd (n = 3) of three experiments.

To determine whether PLDα3 encodes a functional PLD, the gene was tagged at the C terminus with hemagglutinin (HA) and expressed in Arabidopsis (Figure 1B). HA-tagged PLDα3 was purified, and PLD activity was assayed at Ca2+ concentrations and conditions previously defined for PLDα1, -β, -δ, and -ζ (Pappan et al., 1998; Wang and Wang, 2001; Qin and Wang, 2002). PLDα3 was active under PLDα1 reaction conditions that included 50 mM Ca2+, SDS, and single-lipid-class vesicle (Figure 1C). PLDα3 was inactive under PLDβ, -γ, or -ζ conditions, which included phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate (PIP2), phosphatidylethanolamine (PE), and micromolar levels or no Ca2+ in the reaction mixtures. PLDα3 displayed low activity under PLDδ conditions that included micromolar levels of Ca2+ and oleic acid (Figure 1C). PLDα3 hydrolyzed the common membrane phospholipids phosphatidylcholine (PC), PE, phosphatidylglycerol (PG), and phosphatidylserine (PS), having the highest activity toward PC and the lowest toward PS (Figure 1D). PLDα3 had no activity toward phosphatidylinositol (PI) or PIP2 when assayed with single-lipid-class vesicles.

Manipulations of PLDα3 Alter Plant Sensitivity to Salinity

To investigate the cellular functions of PLDα3, a T-DNA insertion mutant of PLDα3 was isolated. The PLDα3 knockout plant (PLDα3-KO), designated pldα3-1, has a T-DNA insertion in the second exon, located 739 bp from the start codon (Figure 2A). The homozygosity of the mutant was confirmed by PCR using PLDα3-specific primers and a T-DNA left border primer (Figure 2B). The mutation resulted in loss of the expression of PLDα3, as indicated by the absence of a detectable PLDα3 transcript by RT-PCR. Thus, pldα3-1 is a knockout mutant (Figure 2C). The mutant allele cosegregated with kanamycin resistance and susceptibility in a 3:1 ratio, suggesting a single T-DNA insertion in the genome. In addition, >30 independent transgenic Arabidopsis lines overexpressing HA-tagged PLDα3 (PLDα3-OE) under the control of the cauliflower mosaic virus 35S promoter were generated, and the expression of PLDα3-HA in the plants was confirmed by immunoblotting using HA antibodies (Figure 1B). A number of independent lines of OE plants were tested for their stress responses, and their physiological effects were correlated with the level of overexpression. For further characterization, two or three representative independent transgenic lines were used in each experiment.

Figure 2.

The T-DNA Insertion Mutant of PLDα3 and Effects of PLDα3 Alterations on Seed Germination under Salt Stress.

(A) T-DNA insertion in the second exon of PLDα3. White boxes indicate exons of PLDα3.

(B) Confirmation of the T-DNA insertion in pldα3-1. PCR of genomic DNA from wild-type and pldα3-1 plants using two pairs of primers: T-DNA refers to the fragment amplified using the left border primer and a PLDα3-specific primer; PLDα3 marks the fragment amplified using two PLDα3 primers, one on either side of the T-DNA insert. The presence of the T-DNA band and the lack of the PLDα3 band in pldα3-1 indicates that it is a homozygous T-DNA insertion mutant. The experiment was repeated three times under the same conditions.

(C) The loss of PLDα3 transcript in pldα3-1. RT-PCR of RNA from wild-type and pldα3-1 plants using two pairs of primers: PLDα3-specific primers detect the expression of the PLDα3 mRNA, and UBQ10 primers were used as a control to indicate the same amount of mRNA between pldα3-1 and wild-type plants. The experiment was repeated three times under the same conditions.

(D) to (G) Seeds were germinated in Murashige and Skoog (MS) medium containing 0 (control), 150, or 200 mM NaCl.

COM, PLDα3 complementation; OE, PLDα3 overexpression; pldα3-1, PLDα3 knockout mutant. Values are means ± sd (n = 3) from one representative of three independent experiments with similar results. One hundred seeds per genotype were measured in each experiment. The photographs were taken at 3 d after seeds were sown. Bar = 3 mm.

Wild-type, OE, and pldα3-1 plants displayed no significant morphological alterations under control growth conditions. No apparent differences in growth and development were observed when seeds of these plants were germinated under nitrogen or phosphorus deficiency, water lodging, or in response to the growth regulators 1-aminocyclopropane-1-carboxylic acid, indole acetic acid, or cytokinin. However, pldα3-1 was more sensitive to salt stress than was the wild type, whereas PLDα3-OE was less sensitive. In the absence of NaCl, nearly 100% of seeds of all genotypes germinated within 2 d (Figure 2D). In the presence of 150 mM NaCl, the germination of pldα3-1 seeds was delayed, whereas that of PLDα3-OE was enhanced compared with wild-type seeds in the early stage of germination (Figure 2E). The seedling size and root length of PLDα3-OE were greater than those of the wild type, whereas those of pldα3-1 were smaller (Figure 2G). When NaCl was increased to 200 mM, the germination of pldα3-1 was much slower, whereas that of PLDα3-OE was faster than that of the wild type (Figure 2F). Introducing native PLDα3 into the pldα3-1 mutant (PLDα3 complementation) restored the mutant phenotype to wild-type plants (Figures 2D to 2F), confirming that the changes observed in the insertion mutant were caused by the loss of PLDα3.

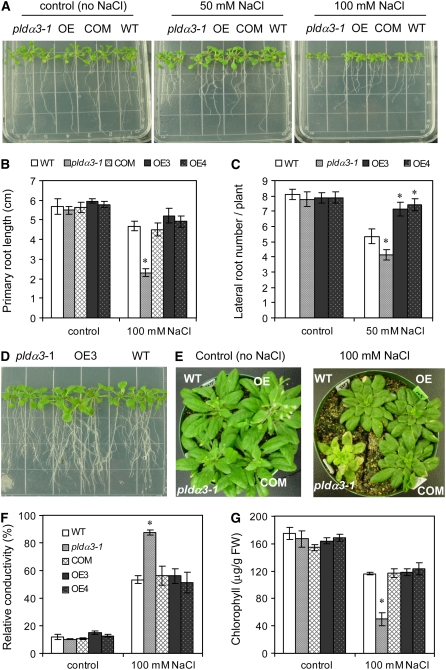

To further characterize the salt stress response, 4-d-old seedlings germinated under non-salt-stress conditions were transferred to MS agar plates containing 50 or 100 mM NaCl. Primary root growth was inhibited in pldα3-1 plants, and the length was ∼50% that of wild-type plants (Figures 3A and 3B). PLDα3-altered plants also differed from wild-type plants in the number of lateral roots (Figure 3C). One week after transfer to MS plates containing 50 mM NaCl, pldα3-1 seedlings had significantly fewer lateral roots per plant than PLDα3-OE or wild-type plants, and PLDα3-OE plants had significantly more lateral roots per plant than wild-type plants (Figure 3C). PLDα3-OE and wild-type plants had similar primary root lengths at the early stages of salt stress (Figure 3B), but PLDα3-OE rosettes grew better than wild-type rosettes under prolonged salt stress (Figure 3D). The pldα3-1 phenotype was restored to wild type after genetic complementation with PLDα3 (Figures 3A and 3B).

Figure 3.

Effects of Altering PLDα3 Expression on Salt Tolerance.

(A) to (C) Changes in seedling growth under salt stress as affected by PLDα3 KO and OE. Four-day-old seedlings were transferred to MS agar plates with 0 (control), 50, or 100 mM NaCl. Primary root length was measured at 2 weeks after transfer. Lateral roots were counted at 6 d after transfer. Values are means ± sd (n = 15) from one representative of three independent experiments. The height of each square on the plate is 1.4 cm. * Significant at P < 0.05 compared with the wild type based on Student's t test.

(D) Seedling growth in 50 mM NaCl on agar plates for 3 weeks.

(E) Changes in salt tolerance in soil-grown, PLDα3-altered plants. Three-week-old plants were irrigated with water only (control) or 100 mM NaCl solution. Photographs were taken at 3 weeks after treatment.

(F) Membrane ion leakage of PLDα3-altered and wild-type plants in response to salt stress. The relative conductivity (an indicator of ion leakage) of leaves was measured in plants grown in soil treated with water only (control) or 100 mM NaCl solution for 2 weeks. Values are means ± sd (n = 3) from one of three independent experiments. * Significant at P < 0.05 compared with the wild type based on Student's t test.

(G) Chlorophyll content of PLDα3-altered and wild-type plants in response to salt stress. The chlorophyll content of leaves was measured in plants as described for (E). Values are means ± sd (n = 3) from one of three independent experiments with similar results. * Significant at P < 0.05 compared with the wild type based on Student's t test.

To determine whether the altered salt stress response also occurred in plants grown in soil, 3-week-old plants were subjected to salt stress by irrigation with 100 mM NaCl. To minimize other effects, such as plant size and soil water content, during the salt treatment, PLDα3-altered plants were grown in the same pots with wild-type plants. pldα3-1 plants were more susceptible to salt stress than PLDα3-OE or wild-type plants. After 2 or 3 weeks of salt stress, pldα3-1 plants became yellow and eventually died, whereas wild-type and OE plants survived and grew to maturation (Figure 3E). The rate of ion leakage, an indicator of membrane integrity, in pldα3-1 plants was much higher than in wild-type and PLDα3-OE plants (Figure 3F). Chlorophyll content was also significantly lower in pldα3-1 than in wild-type plants (Figure 3G). These results suggest that PLDα3 is required for normal growth in the presence of salt.

Alterations in PLDα3 Expression Change Plant Development under Water Deficit

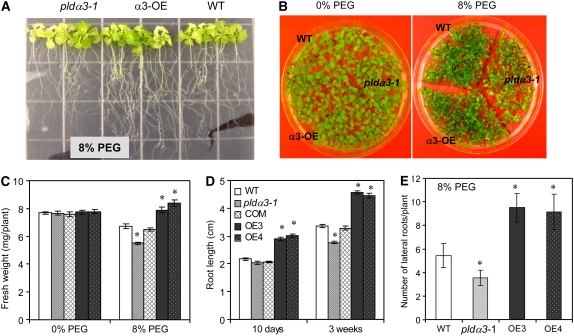

To determine whether the alteration was specific to salinity, pldα3-1, PLDα3-OE, and wild-type seedlings were tested for their responses to other hyperosmotic stresses. In the presence of 8% polyethylene glycol (PEG), the growth of pldα3-1 seedlings was inhibited, whereas PLDα3-OE seedlings grew better than wild-type seedlings (Figures 4A and 4B). Compared with wild-type seedlings, pldα3-1 seedlings had ∼80% of the biomass accumulation and 20% shorter primary roots, whereas PLDα3-OE seedlings accumulated 25% more biomass and had longer primary roots and more lateral roots (Figures 4C to 4E). These results indicate that ablation of PLDα3 decreases plant response to hyperosmotic stress, in addition to salt stress specifically.

Figure 4.

Growth of Wild-Type, PLDα3-KO, and PLDα3-OE Plants under Hyperosmotic Stress.

(A) and (B) Root and seedling phenotypes.

(C) Seedling fresh weight. Seeds were germinated and grown on MS (control) or MS agar plates containing 8% PEG. Fresh weights were measured at 15 d after seeds were sown. Values are means ± sd (n = 10) from one of three independent experiments. At least 30 seedlings of each genotype were measured.

(D) Primary root length. Five-day-old seedlings were transferred to 8% PEG in MS agar plates for 3 weeks, and primary root length was measured. Values are means ± sd (n = 10) from one of three independent experiments. At least 30 seedlings of each genotype were measured.

(E) Lateral root number. Root number was counted at 2 weeks after 5-d-old seedlings were transferred to 8% PEG on MS agar plates. Values are means ± sd (n = 10) from one of three independent experiments. * Significant at P < 0.05 compared with the wild type based on Student's t test.

The effect of PLDα3 KO and OE was investigated in plants grown in soil with limited water supply. Water deficits were imposed on wild-type, pldα3-1, and PLDα3-OE plants at ∼25 to 30% of soil water capacity (soil saturated with water). Under water deficit, the relative water content of the leaves was ∼60% that of well-watered plants. Plants continued growing, but growth was slower than for plants grown under well-watered conditions. When water deficiency was chronic, PLDα3-OE plants flowered earlier and pldα3-1 plants flowered later than wild-type plants (Figures 5A, 5C, and 5D). On average, OE plants bolted and flowered 9 d earlier than wild-type plants, but pldα3-1 plants flowered 6 days later than wild-type plants. At the time of flowering, OE plants had four and eight fewer rosette leaves than wild-type and pldα3-1 plants, respectively (Figure 5D). The flowering time was also affected by the level of PLDα3 protein; the OE line with a higher level of PLDα3 flowered earlier than did plants with a lower level of PLDα3 (Figures 1B and 5B). The OE plants set seeds earlier and had more siliques than wild-type plants and plants containing the empty vector at the flowering stage (Figure 5E). However, under well-watered growth conditions, wild-type, pldα3-1, and PLDα3-OE plants displayed no differences in flowering time or in the number of rosette leaves or siliques.

Figure 5.

Flowering Time Changes in PLDα3-KO and PLDα3-OE Plants under Water Deficit.

(A) Flowering times of PLDα3-altered and wild-type plants grown under the same water-deficient conditions.

(B) Immunoblot of PLDα3 levels in two PLDα3-OE lines (top panel) and the association of the PLDα3 protein level with flowering time (bottom panel) under water deficit conditions.

(C) and (D) Days to bolting and number of rosette leaves in bolting plants under water deficit. Values are means ± sd (n = 15) from one representative of three independent experiments.

(E) Number of siliques in two PLDα3-OE lines, wild-type plants, and plants transformed with the empty vector. Silique numbers were counted in 55-d-old plants grown under water deficit conditions. KO plants were not scored because they flowered later. Values are means ± sd (n = 20).

(F) to (H) Expression of FT, BFT, and TSF in wild-type, PLDα3-KO, and PLDα3-OE plants. mRNA was extracted from leaves of 3-week-old plants (before inflorescence formation under well-watered conditions; control) or from leaves of plants during inflorescence or flowering under water deficit (25 to 30% of soil water capacity). The expression levels were monitored by quantitative real-time PCR normalized by comparison with UBQ10. Values are means ± sd (n = 3).

* Significant at P < 0.05 compared with the wild type based on Student's t test.

The FLOWERING LOCUS T (FT) gene is a key integrator of signals that influence Arabidopsis flowering time (Corbesier et al., 2007; Mathieu et al., 2007). Increases in the expression of FT promote flowering. Thus, we measured the expression patterns of FT and its paralogues, BROTHER OF FT AND TFL1 (BFT) and TWIN SISTER OF FT (TSF), by real-time PCR. Under well-watered conditions, the expression levels of FT and BFT were not different among 3-week-old PLDα3-altered and wild-type plants, but levels of TSF were lower in pldα3-1 than in wild-type plants. Under water deficit conditions, the FT expression level was lower in pldα3-1 plants, whereas the expression levels of BFT and TSF were higher in OE plants than in wild-type and pldα3-1 plants at the inflorescence stage (Figures 5F to 5H). The trend of changes in the expression of flowering timing markers is consistent with the different flowering times resulting from PLDα3 alterations.

Changes in ABA Content and ABA Response under Osmotic Stress

The transition from vegetative to reproductive development is controlled by multiple environmental and endogenous factors. The hormone ABA regulates stress responses, flowering, seed germination, and development. ABA is induced by drought stress and inhibits plant flowering (Bezerra et al., 2004; Razem et al., 2006). To investigate whether alterations of PLDα3 changed ABA level and ABA response, ABA content was measured in pldα3-1, OE, and wild-type plants under control and drought conditions (Figure 6A). Under control growth conditions, the ABA content of OE plants was ∼5% higher than that of wild-type plants, whereas the ABA content of pldα3-1 plants tended to be lower than that of wild-type plants, although the difference was not significant. When water was withheld, increases in ABA occurred in all three genotypes. However, compared with day 0 of the same genotype, the significant increase occurred at 2 d earlier in OE plants than in pldα3-1 and wild-type plants (Figure 6A, top panel). At 8 d without watering, all genotypes had similar levels of ABA. These results indicate that altered expression of PLDα3 has a small, yet significant, effect on the basal level of ABA and that plants with ablation or elevation of PLDα3 are still capable of the drought-induced accumulation of ABA.

Figure 6.

ABA Content in and Effect on PLDα3-Altered and Wild-Type Plants.

(A) ABA content and the expression of ABA-responsive genes in PLDα3-altered and wild-type plants under water deficit. ABA content was measured by mass spectrometry, and ABA-responsive genes were examined by real-time PCR in 3-week-old plants during the transition from control water (90% of soil water capacity) to water-deficient (25 to 30% of soil water capacity) conditions. The number of days refers to days without watering under the water deficit conditions. Values are means ± sd (n = 3 independent samples) from one of two independent experiments with similar results. * Significant at P < 0.05 compared with the wild type based on Student's t test; a,b significant at P < 0.05 compared with day 0 within the same genotype.

(B) and (C) Effect of ABA on the growth of PLDα3-altered seedlings. Seeds were germinated in MS medium containing 5 μM ABA. Fresh weights were measured at 5 weeks after germination. Values are means ± sd (n = 20) from one of three experiments.

(D) Water loss from detached leaves of PLDα3-altered plants. The leaves were detached from 5-week-old plants and exposed to cool-white light (100 μmol·m−2·s−1) at 23°C. Loss of fresh weight was used as a measure of water loss. pldα1 represents the PLDα1 knockout mutant. Values are means ± sd (n = 5).

The expression of the ABA- and osmotic stress–responsive genes RAB18 and RD29B was monitored by quantitative real-time PCR. RAB18 or RD29B, the desiccation-responsive gene that contains at least one cis-acting ABA-responsive element, has been widely used as a reporter for hyperosomotic stress and ABA response. The trend of basal levels of RD29B expression was similar to that of ABA levels among wild-type, pldα3-1, and OE plants under control growth conditions. However, RD29B expression in pldα3-1 was increased greatly at day 6 without water, 2 d sooner than the expression increased in wild-type plants (Figure 6A, middle panel). In OE plants, increases in RD29B expression also occurred, but the magnitude was much smaller than in wild-type and pldα3-1 plants, even after 8 d without water. Likewise, the expression of RAB18, another ABA-inducible gene, also exhibited an earlier and larger increase in pldα3-1 than in wild-type plants, whereas that of OE plants was less induced by water deficit (Figure 6A, bottom panel).

When seedlings were grown on MS medium supplemented with ABA, the growth of pldα3-1 seedlings was more inhibited than that of wild-type seedlings, whereas that of OE seedlings was less inhibited (Figure 6B). The biomass accumulation of pldα3-1 was only 46% of wild-type levels, whereas that of OE was 145% of wild-type levels after 30 d of growth on MS medium containing 5 μM ABA (Figure 6C). Without ABA, all three genotypes accumulated similar amounts of biomass (Figure 4C). PLDα1 has been shown to be involved in the promotion of stomatal closure by ABA (Zhang et al., 2004; Mishra et al., 2006). KO of PLDα1 impeded stomatal closure and increased leaf water loss, but the water loss from detached leaves was not significantly different among PLDα3-KO, PLDα3-OE, and wild-type plants (Figure 6D). These results suggest that unlike PLDα1, PLDα3 is not involved in the ABA regulation of stomatal movement and transpirational water loss.

Effects of PLDα3 on PA Content and Lipid Composition

PLDα3 hydrolyzed various membrane phospholipids in vitro to produce PA (Figure 1D). To determine the effect of PLDα3 on lipid composition, we quantitatively profiled glycerophospholipids and galactolipids of wild-type, pldα3-1, and OE plants. Under control growth conditions, the levels of PC, PE, PG, PS, monogalactosyldiacylglycerol (MGDG), and digalactosyldiacylglycerol (DGDG) were similar in pldα3-1 and wild-type plants. PA content in pldα3-1 plants was ∼80% that of wild-type plants (Figure 7A), indicating that PLDα3 contributes to the production of basal PA.

Figure 7.

Lipid Changes in Plants in Response to Drought Stress.

(A) Total lipid levels in PLDα3-altered, PLDα1-KO, and wild-type plants under water deficit and well-watered conditions. Four-week-old plants grown in growth chambers were not watered until the relative water content of leaves was ∼40%. Well-watered plants were used as controls. Leaf lipids were extracted from four different samples and profiled by ESI–tandem mass spectrometry. Values are means ± se (n = 4)

(B) Lipid species in PLDα3-altered and wild-type plants under water deficit. Values are means ± se (n = 4) of four different samples.

* Significant at P < 0.05 compared with the wild type based on Student's t test.

Water deficit induced a substantial loss of phospholipids and galactolipids (Figure 7A). OE and wild-type plants underwent similar declines in all measured lipids, except PE, which was significantly lower in OE than in wild-type plants. Compared with wild-type plants, pldα3-1 plants had higher levels of nearly all lipids, except PA, which was ∼60% of the wild-type level (Figure 7A). By comparison, under the same water stress conditions, the effect of PLDα1 KO on lipid change was smaller than that of PLDα3 KO. The level of PG was higher and that of PA was lower in PLDα1-KO than in wild-type plants (Figure 7A).

The difference in PA among pldα3-1, OE, and wild-type plants was due primarily to differences in levels of 34-carbon PA species, which contain 18- and 16-carbon fatty acids (Devaiah et al., 2006) (Figure 7B). In terms of potential substrate lipids, pldα3-1 had higher levels of both 34- and 36-carbon PCs as well as higher levels of PG and PI, although PI was not a substrate in vitro (Figure 1D). 34:6 MGDG and 36:6 DGDG were also higher in pldα3-1, and 34:6 PA, which is likely to be formed by the hydrolysis of 34:6 MGDG, was lower in pldα3-1 plants. These results indicate that PLDα3 is involved in the drought-induced loss of glycerol polar lipids and changes in membrane lipid composition.

Changes in the Levels of TOR and AGC2.1 Expression

PLD-derived PA has been shown to activate mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) signaling, which regulates protein synthesis, cell growth, and stress responses (Fang et al., 2001). TOR plays important roles in cell growth and embryonic development in Arabidopsis, as well as in hyperosmotic stress (Menand et al., 2002; Mahfouz et al., 2006). Our results show that alterations of PLDα3 changed PA level, osmotic tolerance, growth, and development under salt and water deficit stresses. These observations led to testing of whether alterations of PLDα3 affected the TOR signaling pathway in the hyperosmotic response. The transcript level of TOR in PLDα3-altered plants was assessed under both salt stress and water deficiency conditions by real-time PCR. The level of TOR expression was lower in pldα3-1 plants and higher in OE plants than in wild-type plants under both conditions (Figure 8A). We also monitored the expression of AGC2.1 kinase, whose activity was shown to be regulated by PA to promote root hair growth in Arabidopsis (Anthony et al., 2004). The transcript level of AGC2.1 kinase was significantly lower in pldα3-1 than in wild-type and OE plants under salt stress, but there was no difference in AGC2.1 expression between PLDα3-altered and wild-type plants under water deficient conditions (Figure 8A). These results suggest that alterations of PLDα3 affect the expression of AGC2.1 and TOR differently.

Figure 8.

Levels of TOR Expression, AGC2.1 Expression, and Phosphorylated S6K Protein in PLDα3-Altered and Wild-Type Seedlings under Hyperosmotic Stress.

(A) Expression levels of TOR and AGC2.1 under salt and water deficit conditions. Four-day-old seedlings were transferred to MS agar plates containing 100 mM NaCl or 8% PEG. Seedlings grown in MS without NaCl or PEG were used as the control. RNA was extracted from seedlings at 3 weeks after transfer. Gene expression level was quantified by real-time PCR normalized by UBQ10. Values are means ± sd (n = 3) from one of two experiments with similar results. * Significant at P < 0.05 compared with the wild type based on Student's t test.

(B) Level of phosphorylated S6K. Proteins were extracted from seedlings grown in the same conditions described for (A). The same amounts of proteins (12 μg/lane) were separated by 10% SDS-PAGE and then transferred to nitrocellulose membranes. Phosphorylated S6K was detected by immunoblotting with anti-phospho-p70 S6K (Thr-389) antibody. The data shown are based on one of two experiments with similar results.

TOR regulates cellular activities by the phosphorylation of downstream targets, such as ribosomal S6 kinase (S6K), which phosphorylates ribosomal proteins to promote translation. Data from GENEVESTIGATOR (https://www.genevestigator.ethz.ch) show that S6K is induced by salt stress, and it has further been implicated in the hyperosmotic stress response in Arabidopsis (Mahfouz et al., 2006). To investigate whether the level of phosphorylated S6K was changed in PLDα3-altered plants, the proteins extracted from KO, OE, and wild-type plants were immunoblotted with an anti-phospho-p70 S6K antibody. Under control growth conditions, the level of phosphorylated S6K was not significantly different among KO, OE, and wild-type plants. However, under salt and water deficit conditions, the level of phosphorylated S6K was lower in pldα3-1 plants than in wild-type plants (Figure 8B). OE and wild-type plants had similar levels of phosphorylated S6K under the 100 mM NaCl condition, and OE plants had a higher level than wild-type plants under the water deficit condition (8% PEG) (Figure 8B). Thus, the level of phosphorylated S6K is correlated with hyperosmotic tolerance.

DISCUSSION

The results presented here show that manipulation of PLDα3 alters the plant response to hyperosmotic conditions. PLDα3 is most active under the conditions defined for PLDα1 and has the highest activity toward PC among the various lipids tested. By comparison, in vitro assays show that PLDα1 uses PC and PE almost equally well and has almost no activity toward PS (Pappan et al., 1998). In addition, the expression of PLDα3 was much lower than that of PLDα1; the difference in young leaves was ∼5000-fold. This observation is consistent with previous reports that PLDα1-KO leaves have almost undetectable PLD activity under the PLDα1 assay condition (Zhang et al., 2004). These results indicate that PLDα3 and PLDα1 have overlapping and yet distinguishable biochemical and regulatory properties and that activation of these PLDs may result in distinguishable hydrolysis of membrane lipids and changes in lipid composition under stress.

To gain insights into how PLDα3 affects the plant response to osmotic stress, this study investigated the effect of PLDα3 KO and OE on lipid composition, ABA responses, and cellular components involved in growth regulation and flowering time. Without applied stress, KO of PLDα3 or -α1 did not cause apparent changes in membrane glycerolipid composition, except that PA levels in the KO mutants were lower than those in wild-type plants. Under prolonged mild drought, PLDα3-KO plants underwent less alteration of lipid composition than wild-type or PLDα1-KO plants, meaning that under drought conditions, PLDα3-KO plants were considerably different in lipid composition than wild-type or PLDα1-KO plants. The greater effect on drought-altered lipid profiles of PLDα3 ablation compared with PLDα1 ablation was unexpected, given the finding that the expression and in vitro activity levels of PLDα3 in leaves were much lower than those of PLDα1. Indeed, ablation of PLDα3 reduced the drought-induced decreases of almost all polar lipids, including PC, PE, PG, PS, PI, and DGDG (Figure 7), despite the fact that DGDG and PI are not substrates of PLDα3. These results suggest that PLDα3 promotes decreases in glycerolipids under water deficit but that much of the lipid loss in PLDα3-KO plants does not result directly from PLDα3-catalyzed hydrolysis. The notion that PLDα3 acts in a regulatory role is consistent with the finding that, during drought, PLDα3-OE and wild-type plants had similar levels of phospholipids and galactolipids, except for a lower level of PE. The specific effect of PLDα3 on other lipolytic enzymes remains to be determined.

The results suggest that PLDα3 plays a negative role in the plant response to ABA. However, KO and OE of PLDα3 had no significant impact on leaf water loss (Figure 6D), suggesting that PLDα3 is not involved in the ABA regulation of stomatal closure. By comparison, PLDα1 has been shown to play a positive role in mediating the ABA promotion of stomatal closure and decreases in transpirational water loss (Zhang et al., 2004; Mishra et al., 2006). KO of PLDα1 increases leaf water loss, whereas OE decreases the loss (Sang et al., 2001; Zhang et al., 2004). On the other hand, KO of PLDα1 did not affect the ABA inhibition of seedling growth. The distinctively different effects of the two PLDαs suggest that PLDα1 and -α3 enhance the plant osmotic stress response through different mechanisms. It might be possible that PLDα1 mediates the ABA effect on stomatal movement to reduce water loss, whereas PLDα3 promotes root growth in response to osmotic stress. Under hyperosmotic stress, PLDα3-KO plants have shorter and fewer roots, whereas PLDα3-OE plants have longer and more roots. A robust root system enables plants to maintain water status, thus delaying ABA-responsive gene expression. Thus, PLDα3 may not be directly involved in the ABA signaling pathway and instead may be more involved in promoting growth under osmotic stress.

To test the effect of PLDα3 KO and OE on plant growth, changes in TOR and S6K were monitored in PLDα3-altered plants under hyperosmotic stresses. The TOR pathway is involved in the hyperosmotic stress response in animals (Fang et al., 2001) and also in plants (Mahfouz et al., 2006). Mammalian PLD1-derived PA was found to be a mediator in mTOR signaling. Our data show that pldα3-1 plants had less PA than wild-type and OE plants under osmotic stress. Alterations of PLDα3 led to a change in TOR transcription levels under both salt and water deficient conditions. In addition, the level of phosphorylated S6K was lower in pldα3-1 plants than in wild-type plants under salt and water deficit conditions. TOR regulated cellular activities by activating downstream kinases, and S6K was one of the well-characterized TOR targets. PA activated mTOR, that stimulated S6K through phosphorylation. S6K has been implicated in the hyperosmotic stress response in Arabidopsis (Mahfouz et al., 2006). These results raise the possibility that PLDα3 may be involved in the TOR signaling pathway in the stress response. One promising future direction is to determine whether PA interacts directly with TOR or S6K to regulate the hyperosmotic responses.

The altered stress responses exhibited in PLDα3-OE and PLDα3-KO plants may be caused by alterations in lipid metabolism and/or signal transduction. Changes in membrane lipid composition can result in changes of the localization and activities of signaling messengers associated with membranes. Specifically, the effect of PLDα3 OE and KO on flowering time raises an interesting question: Do PLDα3-mediated changes under water deficit affect key cellular components that control flowering time and the life cycle? Early flowering allows plants to accelerate their life cycle, an important mechanism by which plants escape stress. Arabidopsis flowering is controlled by environmental and endogenous signals (Corbesier et al., 2007). A key integrator of the signal input is FT, which encodes a small protein. In the current model, FT functions as a mobile signal moving from leaves to the shoot apex, where it interacts with the basic domain/Leu zipper transcription factor FLOWERING LOCUS D to activate the transcription of the floral meristem identity gene APETALA1. Interestingly, FT and its paralogues TSF and BFT contain a lipid binding domain with similarity to RAF kinase inhibitors that bind the membrane lipid PE (Mathieu et al., 2007). Under drought conditions, the level of PE in pldα3-1 was higher, whereas that in OE was lower, than the wild-type level. Although increases in PC and PG and a decrease in PA occurred in pldα3-1, PE was the only altered lipid class in OE plants. By contrast, KO of PLDα1 did not change the PE level compared with the wild type (Figure 7). This raises the possibility that the altered PE levels may be responsible for the alteration of flowering time in PLDα3-altered plants under water-deficient conditions. One scenario could be that the PE–FT interaction might tether the protein to membranes and attenuate its flowering-promoting functions. However, it is unknown whether FT or its paralogues actually interact with PE or other membrane lipids, such as PA.

Collectively, these results indicate that PLDα3 plays a role in modulating plant growth and development under hyperosmotic stresses. The data suggest possible connections between membrane lipid–based signaling and some of the key regulators in flowering promotion and the hyperosmotic response. Further studies on the potential interactions of PLD and lipids with regulators such as ABA, FT, and TOR will help us better understand the mechanisms by which plants respond to salinity and water deficiency.

METHODS

Knockout Mutant Isolation and Complementation

A T-DNA insert mutant in PLDα3, designated pldα3-1, was identified from the Salk Arabidopsis thaliana T-DNA knockout collection (SALK_130690), and seeds were obtained from the ABRC at Ohio State University. A PLDα3 homozygous T-DNA insert mutant was isolated by PCR screening using the PLDα3-pecific primers 5′-CTCGAGATGACGGACCAATTGCTGCTTCATCG-3′ (forward primer) and 5′-ACGCCTAGAAGTAAGGATGATTGGAGGAAGA -3′ (reverse primer) and the left border primer 5′-GCGTGGACCGCTTGCTGCAACT-3′. A pair of PLDα3-specific primers were used in RT-PCR to confirm the PLDα3 null mutant: 5′-ATGGTTAATGCAACGGCAGACGAG-3′ (forward) and 5′-CCCGGTAAATCGTCATTTCGAGGA-3′ (reverse). The PCR conditions were 95°C for 1 min for DNA melting, 40 cycles of 95°C for 30 s, annealing for 30 s (annealing temperature was based on the melting points of the specific primers), and 72°C for 30 s for DNA extension. Finally, the reaction was set at 72°C for 10 min. For complementation of the PLDα3 knockout mutant, the native PLDα3 gene, including its own promoter region, was amplified from 1.5 kb upstream of the start codon and 600 bp after the stop codon and then was cloned into the pEC291 vector. The primers for PLDα3 complementation were 5′-CTGCAGGTAAGATTCACAAAATTGGTGTAATAC-3′ (forward) and 5′-AAGCTTGAGTGAATATGGTCTATGGATATT-3′ (reverse). The plasmid was transformed into pldα3-1 plants with the flower-dipping method (Martinez-Trujillo et al., 2004). The transformants were selected from hygromycin plates and confirmed by PCR using the primers TeasyAsc5 (5′-ATGGCGCGCCATATGGTCGACCTGCAG-3′) and TeasyAsc3 (5′-ATGGCGCGCCCGACGTCGCATGCTC-3′). PCR or RT-PCR products were visualized by staining with ethidium bromide on a 1% agarose gel after electrophoresis.

Plant Growth and Treatments

pldα3-1, OE, wild-type, and pldα3-1 complemented with PLDα3 (PLDα3 complementation) plants were grown in soil in growth chambers under 12-h-light/12-h-dark photoperiods (120 μmol·m−2·s−1) at 23/21°C and 50% humidity. For salt stress experiments, 3-week-old plants were treated with various concentrations of NaCl. Meanwhile, 4-d-old seedlings of pldα3-1, OE, wild-type, and PLDα3 complementation plants were transferred to MS (1×) agar plates containing 50 and 100 mM NaCl to test salt tolerance. For water stress experiments, 3-week-old plants (before inflorescence formation) were not watered for several days until soil water content was 25 to 30% of soil water capacity (soil saturated with water). The water-deficient condition was maintained by adding 50 mL of water to each pot (12 × 12 × 14 cm) every 4 d. Under this condition, the relative water content of leaves was 50%, whereas the relative water content for well-watered plants was ∼80%. For seed germination in response to osmotic stress or hormone treatment, seeds were germinated on MS (1×) agar plates supplemented with NaCl, PEG, or ABA. To minimize experimental variation, plants of similar size of different genotypes were grown in the same pots or on the same plates for stress treatments.

Expression, Purification, and PLDα3 Activity Assay

The PLDα3 gene was amplified from Arabidopsis genomic DNA using the PLDα3 gene-specific primers 5′-CTCGAGATGACGGACCAATTGCTGCTTCATCG-3′ (forward) and 5′-ACGCCTAGAAGTAAGGATGATTGGAGGAAGA 3′ (reverse), introducing cloning sites of XhoI/StuI. The PLDα3 sequence was fused with DNA encoding an HA tag and cloned into a binary pKYLX71 vector. HA-tagged PLDα3 was expressed in Arabidopsis plants under the control of the 35S promoter. The C-terminally tagged PLDα3-HA protein was purified from plant proteins by immunoaffinity column chromatography using HA antibodies conjugated to agarose beads. The purified protein was used for activity assays with dipalmitoylglycero-3-phospho-(methyl-3H) choline as a substrate under different conditions defined previously for other PLDs (Pappan et al., 1997; Wang and Wang, 2001; Qin and Wang, 2002). Briefly, PLDα1 activity was assayed in the presence of 25 mM Ca2+, 100 mM MES, pH 6, 0.5 mM SDS, and 2 mM PC. PLDβ and -γ were assayed using 5 μM Ca2+, 80 mM KCl, 2 mM MgCl2, 100 mM MES, pH 7, and 0.4 mM lipid vesicle composed of PC:PE:PIP2 (0.2:3.5:0.3). The PLDδ reaction condition was 100 mM MES, pH 7, 2 mM MgCl2, 80 mM KCl, 100 μM CaCl2, 0.15 mM PC, and 0.6 mM oleate. PLDζ1 activity was measured in the presence of 100 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7, 80 mM KCl, and 0.4 mM lipid vesicle composed of PC:PE:PIP2 (0.2:3.5:0.3) (Qin and Wang, 2002). Hydrolysis of PC was quantified by measuring the release of [3H]choline by scintillation counting.

Real-Time PCR

Real-time PCR was performed as described by Li et al. (2006). Briefly, total RNA was extracted from leaves using the cetyl-trimethyl-ammonium bromide method. DNA was removed from RNA by digestion with RNase-free DNaseI. RNA was used as a template for reverse transcription to synthesize cDNA using the iScript kit (Bio-Rad). Quantitative real-time PCR was performed with the MyiQ sequence detection system (Bio-Rad) by monitoring the SYBR Green fluorescent labeling of double-stranded DNA synthesis. The efficiency of the cDNA synthesis was assessed by real-time PCR amplification of a control gene encoding UBQ10 (At4g05320), and the UBQ10 gene Ct value was 20 ± 0.5. Only cDNA preparations that yielded similar Ct values for the control genes were used for the determination of PLD gene expression. The level of PLD expression was normalized to that of UBQ10 by subtracting the Ct value of UBQ10 from the Ct value of PLD genes (Li et al., 2006). The primers for different genes were as follows: PLDα3, 5′-ATGGTTAATGCAACGGCAGACGAG-3′ (forward) and 5′-CCCGGTAAATCGTCATTTCGAGGA-3′ (reverse); RD29B, 5′-ACAATCACTTGGCACCACCGTT-3′ (forward) and 5′-AACTCACTTCCACCGGAATCCGAA-3′ (reverse); RAB18, 5′-GCAGTCGCATTCGGTCGTTGTATT-3′ (forward) and 5′-ACAACACACATCGCAGGACGTACA-3′ (reverse); TOR, 5′-AGTTCGAAGGGCAAAGTACGACGA-3′ (forward) and 5′-TACGCACGCTCATAGCTCTCCAAA-3′ (reverse); AGC2.1, 5′-AGAAACGTCTCTTCCGCTTCACCA-3′ (forward) and 5′-ACCTGAAGAATCTGACACGGCCAA-3′ (reverse); FT, 5′-TCCCTGCTACAACTGGAACAACCT-3′ (forward) and 5′-ACGATGAATTCCTGCAGTGGGACT-3′ (reverse); BFT, 5′-ATTCAAACAGAGAGGGAGGCAAGC-3′ (forward) and 5′-GCAGCAACAGGTTGAGAAAGACCA-3′ (reverse); TSF, 5′-AAGACAAACGGTTTATGCACCGGG-3′ (forward) and 5′-TTGAAGTAAGAGGCAGCCACAGGA-3′ (reverse); and UBQ10, 5′-CACACTCCACTTGGTCTTGCGT-3′ (forward) and 5′-TGGTCTTTCCGGTGAGAGTCTTCA-3′ (reverse). The PCR conditions were as follows: 1 cycle of 95°C for 1 min; 40 cycles of 95°C for 30 s for DNA melting, 55°C for 30 s for DNA annealing, and 72°C for 30 s for DNA extension; and 72°C for 10 min for final extension of DNA.

Immunoblotting and Detection of Phosphorylated S6K

Total proteins were extracted from plants or seedlings grown in different conditions using buffer A (50 mM Tri-HCl, pH 7.5, 10 mM KCl, 1 mM EDTA, 2 mM DTT, and 0.5 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride). After centrifugation at 6000g for 10 min, the supernatant proteins were separated by 10% SDS-PAGE. After electrophoresis, proteins were transferred to a polyvinylidene difluoride membrane. The membrane was blotted with anti-HA antibody (1:1000) overnight, followed by incubation with a second antibody (1:5000) conjugated with alkaline phosphatase. The protein bands were visualized by alkaline phosphatase reaction. To detect phosphorylated S6K, proteins were transferred to nitrocellulose membranes and blotted with an anti-phospho-p70 S6K (Thr-389) antibody (Cell Signaling Technology), followed by a secondary antibody conjugated with horseradish peroxidase. The rabbit polyclonal antibodies were raised against human p70 S6K and have been shown to react with plant S6K proteins (Reyes de la Cruz et al., 2004). The membranes were preblotted with TBS/T containing 5% BSA and then were incubated with the first antibody (1:1000) in TBS/T buffer. After gentle agitation at room temperature for 1 h, the membranes were washed with TBS/T four times. A polyclonal anti-rabbit IgG antibody conjugated with horseradish peroxidase (1:10,000) was added and incubated for 1 h, followed by three washes with TBS/T and three washes with PBS. After incubation of LumiGLO substrate for 1 min, membranes were exposed to x-ray film.

Lipid Profiling and ABA Measurement

Lipid profiling was performed as described previously (Devaiah et al., 2006). Briefly, leaves were detached and immediately immersed in 3 mL of 75°C isopropanol with 0.01% butylated hydroxytoluene for 15 min, followed by the addition of 1.5 mL of chloroform and 0.6 mL of water. After shaking for 1 h, the extracting solvent was transferred to a clean tube. The leaves were reextracted with chloroform:methanol (2:1) five times with agitation for 30 min each, and the extracts were combined and then washed with 1 M KCl, followed by another wash with water. The solvent was evaporated with a stream of nitrogen. For each treatment, four leaf samples were extracted and analyzed separately. For ABA analysis, fresh leaves (100 mg) were ground in liquid nitrogen. Then, 0.5 mL of 1-propanol:H2O:HCl (2:1:0.002) was immediately added to the homogenate and mixed well. The homogenate was agitated at 4°C for 10 min, followed by the addition of 1 mL of dichloromethane and ABA internal standards. After vortexing and agitation at 4°C for 10 min, the mixtures were centrifuged at 11,300g for 1 min to separate the two phases. The lower phase was transferred to a 1.5-mL vial with a Teflon-lined screw cap. ABA was quantified by mass spectrometry as described by Pan et al. (2008).

Relative Water Content, Ion Leakage, and Chlorophyll

Leaves were detached and fresh weight (FW) was measured followed by incubation in clean water overnight to obtain turgor weight (TW). Leaves were then dried at 80°C for 48 h to measure dry weight (DW). The relative water content (RWC) was obtained based on the following equation: RWC (%) = (FW − DW)/(TW − DW) × 100. To measure ion leakage, leaves were detached and rinsed with distilled water and then were immersed in 15 mL of distilled water in glass tubes. After degassing under vacuum for 30 min to remove air bubbles on the leaf surface, samples were incubated with gentle agitation for 3 h (Fan et al., 1997). Initial conductivity was measured with a conductivity meter, and then the samples were boiled in a water bath for 20 min. Total conductivity was measured again after cooling to room temperature. Ion leakage was expressed as a percentage of the initial conductivity over total conductivity. For chlorophyll content measurement, chlorophyll was extracted from leaf discs placed in sealed vials with an appropriate volume of 100% methanol by shaking in the dark until the leaves became white. The chlorophyll content was obtained based on the absorbance of extracts at 650 and 665 nm (Crafts-Brandner et al., 1984).

Accession Numbers

Sequence data from this article can be found in the Arabidopsis Genome Initiative database under the following accession numbers: PLDα3, At5g25370; RD29B, At5g52300; RAB18, At5g66400; TOR, At1g50030; AGC2.1, At3g25250; FT, At1g65480; BFT, At5g62040; TSF, At4g20370; UBQ10, At4g05320.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Maoyin Li for help on the real-time PCR analysis of PLD expression and to Mary Roth for her help with lipid profiling. This work was supported by grants from the National Science Foundation (Grant IOS-0454866) and the USDA (Grant 2007-35318-18397). The Kansas Lipidomics Research Center's research was supported by grants from the National Science Foundation (Grants MCB-0455318, DBI-0521587, and Kansas Experimental Program to Stimulate Competitive Research Award EPS-0236913), with support from the State of Kansas through the Kansas Technology Enterprise Corporation and Kansas State University, as well from U.S. Public Health Service Grant P20 RR-016475 from the IDeA Network of Biomedical Research Excellence program of the National Center for Research Resources.

The author responsible for distribution of materials integral to the findings presented in this article in accordance with the policy described in the Instructions for Authors (www.plantcell.org) is: Xuemin Wang (wangxue@umsl.edu).

References

- Anthony, R.G., Henrigues, R., Helfer, A., Meszaros, T., Rios, G., Testerink, G., Munnik, T., Deak, M., Koncz, C., and Bogre, L. (2004). A protein kinase target of a PDK1 signalling pathway is involved in root hair growth in Arabidopsis. EMBO J. 23 572–581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bezerra, I.C., Michaels, S.D., Schomburg, F.M., and Amasino, R.M. (2004). Lesions in the mRNA cap-binding gene ABA HYPERSENSITIVE 1 suppress FRIGIDA-mediated delayed flowering in Arabidopsis. Plant J. 40 112–119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bray, E.A. (2004). Genes commonly regulated by water-deficit stress in Arabidopsis thaliana. J. Exp. Bot. 55 2331–2341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chinnusamy, V., Schumaker, K., and Zhu, J.K. (2004). Molecular genetic perspectives on cross-talk and specificity in abiotic stress signalling in plants. J. Exp. Bot. 55 225–236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corbesier, L., Vincent, C., Jang, S., Fornara, F., Fan, Q., Searle, I., Giakountis, A., Farrona, S., Gissot, L., Turnbull, C., and Coupland, G. (2007). FT protein movement contributes to long-distance signaling in floral induction of Arabidopsis. Science 316 1030–1033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crafts-Brandner, S.J., Below, F.E., Harper, J.E., and Hageman, R.H. (1984). Effects of pod removal on metabolism and senescence of nodulating and nonnodulating soybean isolines. II. Enzymes and chlorophyll. Plant Physiol. 75 318–322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cruz-Ramirez, A., Oropeza-Aburto, A., Razo-Hernandez, F., Ramirez-Chavez, E., and Herrera-Estrella, L. (2006). Phospholipase Dζ2 plays an important role in extraplastidic galactolipid biosynthesis and phosphate recycling in Arabidopsis roots. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 103 6765–6770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devaiah, S.P., Roth, M.R., Baughman, E., Li, M., Tamura, P., Jeannotte, R., Welti, R., and Wang, X. (2006). Quantitative profiling of polar glycerolipid species and the role of phospholipase Dα1 in defining the lipid species in Arabidopsis tissues. Phytochemistry 67 1907–1924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan, L., Zheng, S., and Wang, X. (1997). Antisense suppression of phospholipase Dα retards abscisic acid and ethylene-promoted senescence of postharvest Arabidopsis leaves. Plant Cell 9 2183–2196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fang, Y., Vilella-Bach, M., Barchmann, R., Flanigan, A., and Chen, J. (2001). Phosphatidic acid-mediated mitogenic activation of mTOR signaling. Science 294 1942–1945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frank, W., Munnik, T., Kerkmann, K., Salamini, F., and Bartel, D. (2000). Water deficit triggers phospholipase D activity in the resurrection plant Craterostigma plantagineum. Plant Cell 12 111–124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujita, M., Fujita, Y., Noutoshi, Y., Takahashi, F., Narusaka, Y., Yamaguchi-Shinozaki, K., and Shinozaki, K. (2006). Crosstalk between abiotic and biotic stress responses: A current view from the points of convergence in the stress signaling networks. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 9 436–442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jonak, C., Okresz, L., Bogre, L., and Hirt, H. (2002). Complexity, cross talk and integration of plant MAP kinase signalling. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 5 415–424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katagiri, T., Takahashi, S., and Shinozaki, K. (2001). Involvement of a novel Arabidopsis phospholipase D, At PLDδ, in dehydration-inducible accumulation of phosphatidic acid in stress signaling. Plant J. 26 595–605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li, G., and Xue, H.W. (2007). Arabidopsis PLDζ2 regulates vesicle trafficking and is required for auxin response. Plant Cell. 19 281–295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li, M., Qin, C., Welti, R., and Wang, X. (2006). Double knockouts of phospholipases Dζ1 and Dζ2 in Arabidopsis affect root elongation during phosphate-limited growth but do not affect root hair patterning. Plant Physiol. 140 761–770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li, W., Li, M., Zhang, W., and Wang, X. (2004). The plasma membrane-bound phospholipase Dδ enhances freezing tolerance in Arabidopsis thaliana. Nat. Biotechnol. 22 427–433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahfouz, M.M., Kim, S., Delauney, A.J., and Verma, D.P. (2006). Arabidopsis TARGET OF RAPAMYCIN interacts with RAPTOR, which regulates the activity of S6 kinase in response to osmotic stress signals. Plant Cell 18 477–490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez-Trujillo, M., Limones-Briones, V., Cabrera-Ponce, J.L., and Herrera-Estrella, L. (2004). Improving transformation efficiency of Arabidopsis thaliana by modifying the floral dip method. Plant Mol. Biol. Rep. 22 63–70. [Google Scholar]

- Mathieu, J., Warthmann, N., Kuttner, F., and Schmid, M. (2007). Export of FT protein from phloem companion cells is sufficient for floral induction in Arabidopsis. Curr. Biol. 17 1055–1060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Menand, B., Desnos, T., Nussaume, L., Berger, F., Bouchez, D., Meyer, C., and Robaglia, C. (2002). Expression and disruption of the Arabidopsis TOR (target of rapamycin) gene. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99 6422–6427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mishra, G., Zhang, W., Deng, F., Zhao, J., and Wang, X. (2006). A bifurcating pathway directs abscisic acid effects on stomatal closure and opening in Arabidopsis. Science 312 264–266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munnik, T., Meijer, H., Riet, B.T., Hirt, H., Frank, W., Bartels, D., and Musgrave, A. (2000). Hyperosmotic stress stimulates phospholipase D activity and elevates the level of phosphatidic acid and diacylglycerol pyrophosphate. Plant J. 22 147–154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pan, X., Welti, R., and Wang, X. (2008). Simultaneous quantification of major phytohormones and related compounds in crude plant extracts by liquid chromatography-electrospray tandem mass spectrometry. Phytochemistry, in press. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Pappan, K., Austin-Brown, S., Chapman, K., and Wang, X. (1998). Substrate selectivities and lipid modulation of plant phospholipase Dα, -β, and -γ. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 353 131–140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pappan, K., Zheng, S., and Wang, X. (1997). Identification and characterization of a novel plant phospholipase D that requires polyphosphoinositides and submicromolar calcium for activity in Arabidopsis. J. Biol. Chem. 272 7048–7054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qin, C., and Wang, X. (2002). The Arabidopsis phospholipase D family. Characterization of a calcium-independent and phosphatidylcholine-selective PLDζ1 with distinct regulatory domains. Plant Physiol. 128 1057–1068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Razem, F.A., El-Kereamy, A., Abrams, S.R., and Hill, R.D. (2006). The RNA-binding protein FCA is an abscisic acid receptor. Nature 439 290–294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reyes de la Cruz, H., Aguilar, R., and Sanchez de Jimenez, E. (2004). Functional characterization of a maize ribosomal S6 protein kinase (ZmS6K), a plant ortholog of metazoan p70(S6K). Biochemistry 43 533–539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sang, Y., Zheng, S., Li, W., Huang, B., and Wang, X. (2001). Regulation of plant water loss by manipulating the expression of phospholipase Dalpha. Plant J. 28 135–144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szaboles, I. (1997). The global problems of salt-affected soils. Acta Agron. Hung. 36 159–172. [Google Scholar]

- Testerink, C., and Munnik, T. (2005). Phosphatidic acid: A multifunctional stress signaling lipid in plants. Trends Plant Sci. 10 368–375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang, C., and Wang, X. (2001). A novel phospholipase D of Arabidopsis that is activated by oleic acid and associated with the plasma membrane. Plant Physiol. 127 1102–1112. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X. (2004). Lipid signaling. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 7 1–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X. (2005). Regulatory functions of phospholipase D and phosphatidic acid in plant growth, development, and stress responses. Plant Physiol. 139 566–573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X., Devaiah, S.P., Zhang, W., and Welti, R. (2006). Signaling functions of phosphatidic acid. Prog. Lipid Res. 45 250–278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Welti, R., Li, W., Li, M., Sang, Y., Biesiada, H., Zhou, H.E., Rajashekar, C.B., Williams, T.D., and Wang, X. (2002). Profiling membrane lipids in plant stress responses. Role of phospholipase D alpha in freezing-induced lipid changes in Arabidopsis. J. Biol. Chem. 277 31994–32002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, W., Qin, C., Zhao, J., and Wang, X. (2004). Phospholipase Dα1-derived phosphatidic acid interacts with ABI1 phosphatase 2C and regulates abscisic acid signaling. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 101 9508–9513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, J., and Wang, X. (2004). Arabidopsis phospholipase Dα1 interacts with the heterotrimeric G-protein α-subunit through a motif analogous to the DRY motif in G-protein-coupled receptors. J. Biol. Chem. 279 1794–1800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, J. (2002). Salt and drought stress signal transduction in plants. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 53 247–273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]