Abstract

The effect of unilateral hearing loss on 2-deoxyglucose (2-DG) uptake in the central auditory system was studied in post-natal day 21 gerbils. Three weeks following a unilateral conductive hearing loss (CHL) or cochlear ablation (CA), animals were injected with 2-DG and exposed to an alternating auditory stimulus (1 and 2 kHz tones). Uptake of 2-DG was measured in the inferior colliculus (IC), medial geniculate (MG), and auditory cortex (fields AI and AAF) of both sides of the brain in experimental animals and in anesthesia-only sham animals (SH). Significant differences in uptake, compared to SH, were found in the IC contralateral to the manipulated ear (CHL or CA) and in AAF contralateral to the CHL ear. We hypothesize that these findings may result from loss of functional inhibition in the IC contralateral to CA, but not CHL. Altered states of inhibition at the IC may affect activity in pathways ascending to auditory cortex, and ultimately activity in auditory cortex itself. Altered levels of activity in auditory cortex may explain some auditory processing deficits experienced by individuals with CHL.

Keywords: auditory cortex, medial geniculate, inferior colliculus, 2-deoxyglucose, conductive hearing loss, cochlear ablation, gerbil

Introduction

Electrophysiological investigations of conductive hearing loss (CHL) in animals have shown that CHL changes the way sound is processed in the peripheral and central auditory system (e.g., Clopton and Silverman, 1978; Webster and Bobbin, 1986; Sumner et al., 2005; Xu and Jen, 2001; Jen and Xu, 2002; Xu et al., 2007). Centrally, unilateral CHL results in a decrease in glucose uptake as measured by the 2-deoxyglucose (2-DG) method, affecting cellular activity and metabolism in the major afferent projection from the manipulated ear (e.g., Tucci et al., 1999, 2001). In these animals, unilateral CHL produced by malleus removal changes the pattern of 2-DG uptake across auditory brainstem structures in a manner similar to animals that have severe cochlear damage, i.e., damage that results in a profound hearing loss.

Using a different paradigm to produce unilateral CHL (surgical atresia), Stuermer and Scheich (2000) demonstrated enhanced 2-DG uptake in primary auditory cortex (AI) but not the anterior auditory field (AAF) contralateral to the manipulated ear. In that study, gerbils’ ears were closed from postnatal day 9 (P9) until testing and sacrifice at P27. Since the onset of hearing in gerbils is approximately P12 (Finck, 1972; Wolf and Ryan, 1984, Ryan and Woolf, 1993), the manipulated ear never received normal stimulation after hearing onset. Pienkowski and Harrison (2005) demonstrated that in chinchilla, a precocious species with onset of hearing in utero, many basic features of auditory cortex are functional at P3 (e.g., sensitivity, firing rates, tonotopic map), yet the spectral-temporal response properties of cortical neurons continue to develop beyond P30 and into adulthood. These authors suggest that it is the postnatal acoustic environment, with its more complex sound content, that is ultimately responsible for proper cortical development.

Enhanced cortical activity has also been show to occur, at least transiently, in adult animals subsequent to chemical ablations of the cochlea (e.g., Popelar et al., 1994; Qiu et al., 2000), and partial mechanical destruction of the cochlea induces reorganization of frequency representations in the contralateral auditory cortex of adult animals (e.g., Robertson and Irvine, 1989; Rajan et al., 1993). Furthermore, neurons in auditory cortex alter their response properties subsequent to changes in stimulus pairings involved in learning and attention paradigms (e.g., Recanzone et al., 1993; Kilgard et al., 2007; Weinberger, 2007; Zatorre, 2007).

Until recently, AI and AAF were considered to be, in essence, mirror images of one another, each possessing a strict and orderly tonotopic map (e.g., Merzenich et al., 1975; Knight 1977; Reale and Imig, 1980, Phillips and Irvine, 1982; Morel et al., 1993; Thomas et al., 1993; Stiebler et al., 1997; Rutkowski et al., 2003) and having similar anatomical connections (e.g., Anderson et al., 1980b; Imig and Reale, 1980; Imig and Morel, 1983), though AAF occupies a smaller area of cortex. This concept has been challenged in several species, based on anatomical, behavioral, and physiological evidence. For example, in cat, there are differences in the proportion of thalamic and cortical inputs to AI and AAF (e.g., Morel and Imig, 1987; Lee et al., 2004a,b), deactivation of AI (but not AAF) disrupts performance on sound localization tasks (Jenkins and Merzenich, 1984; Lomber et al., 2007), and neurons of AI and AAF differ in their response to temporally modulated stimuli (amplitude or frequency modulated tones; Schreiner and Urbas, 1988; Tian and Rauschecker, 1994). Although responses to frequency-modulated tones can be used to differentiate AI from other regions of auditory cortex in gerbil, it does not serve to distinguish AI from AAF (Schulze et al., 1997). Other studies indicate that AI and AAF serve different roles in processing complex sounds (e.g., Linden et al., 2003; Imaizumi et al. 2004; Takahashi et al., 2005), suggesting that AAF may be specialized for rapid temporal processing (Linden et al., 2003). Presumably this specialization requires natural acoustic experience, and that normal development of auditory cortex is dependent upon the postnatal acoustic environment (Takahashi et al., 2006).

The studies mentioned above, and others, point to the differing nature of changes that can occur in the central auditory system though developmental versus adult forms of “plasticity” as a function of either peripheral or central processing mechanisms (see Calford, 2002; Syka, 2002; Irvine, 2007). In our previous reports we investigated the effects of unilateral hearing loss, typically induced in gerbils at P21 after the ear has gained some measure of acoustic “experience”, within nuclei of the auditory brainstem. Here we extend our studies to include the effect of CHL and cochlear ablation (CA) on the medial geniculate (MG) and auditory cortex (AI and AAF). For the present study, we measured glucose metabolism by the 2-DG method in animals three weeks after a unilateral CHL was produced by malleus removal, or after a unilateral CA in P21 gerbils. These results were compared to an anesthesia only sham group (SH) at P42. For comparison with our previous studies, we also measured glucose uptake by the inferior colliculus (IC), and in the medial geniculate (MG) in the same animals. Our primary goal was to address the question of how unilateral CHL effects metabolic activity in the contralateral auditory cortex of immature animals that have experienced approximately 10 days of normal binaural development.

Methods

Subjects

Eighteen mongolian gerbils (Meriones unguiculatus), obtained from a commercial supplier (Charles Rivers), were used in this study. All anesthetic, operative, and postoperative procedures and care followed NIH guidelines, and were approved by the Institutional Animal Care Committee. All experimental procedures and tissue preparation was conducted at the University of Kansas Medical Center. Densitometry and tissue analysis was done at the Duke University Medical Center.

Each animal entered this study on postnatal day 21 (P21), n = 6 for each condition (CA, CHL, SH). Hearing onset occurs at approximately P12 in the gerbil (Finck, 1972; Wolf and Ryan, 1984, Ryan and Woolf, 1993), and at P16 gerbils can accurately approach the source of a sound in space (Kelly and Potash, 1986). By P18 gerbils have mature middle and inner ears, and both the auditory nerve and ventral cochlear nucleus show adult-like physiological response characteristics (Woolf and Ryan, 1985). Thus gerbils at P21 are beyond the age of hearing onset and have acoustic experience, yet their central auditory structures continue to develop through at least P30 (Woolf and Ryan, 1985), and probably into adulthood (Pienkowski and Harrison, 2005).

Surgical Procedures

Animals were anesthetized with an IP injection of a mixture of ketamine (75 mg/kg) and xylazine (5 mg/kg). All surgical procedures were performed unilaterally on the left ear. Animals in the sham (SH) condition served as our anesthesia only control group. For CHL animals, the fur was shaved behind the left ear, a postauricular incision made and tissue retracted away from the external ear canal. Care was taken to preserve the exiting facial nerve. A small opening was then made in the ear canal and the tympanic membrane visualized. Using fine forceps, the tympanic membrane was punctured and the malleus gently removed. The stapes and oval window were then observed, and in no case was there evidence that this procedure compromised the oval window. The surgical wound was then closed with cyanoacrylate glue. Animals in the CA condition underwent the same procedures as above, except that the promontory of the cochlea was visualized after malleus removal, fractured, and fluid suctioned from the cochlea until dry. Previous measures of hearing impairment associated with these manipulations have demonstrated that malleus removal produces a loss of 33 to 57 dB with preserved cochlear integrity, whereas the CA produces a profound sensorineural hearing loss (Tucci et al., 1999). All animals were observed throughout their recovery from anesthesia, and were returned to their home cage where they had free access to food and water.

2-Deoxylucose and Sound Stimulation Methods

Three weeks after surgery (at P42), animals received an IP injection of 2-DG (300 μCi/kg) diluted in sterile saline (typically 0.15 cc for a 50 g gerbil). The animals were placed in a sound attenuating chamber and exposed to tones of 1 and 2 kHz for 45 minutes prior to sacrifice. In gerbils, this combination of tones produces an intense band of 2-DG labeling in AI and a spatially separated band in AAF (Scheich et al., 1993; Stuermer and Scheich, 2000). Sound stimuli were generated using a Matlab system (Kaiser Industries, Irvine, CA), amplified and transduced with a Braun Output C loudspeaker. The loudspeaker was mounted 12 inches above a cage holding the gerbil. Sounds were 250 ms tone bursts with 10 ms rise/fall times presented at a rate of 4 per second. Tone bursts alternated between 1 and 2 kHz, and varied between 70 and 80 dB SPL in 2 dB steps (measured with a microphone located in the holding cage).

Following their exposure to sound, animals were anesthetized with halothane, decapitated and brains quickly dissected from the skull. The fresh brain tissue was then rapidly frozen in heptane cooled to -65°C on dry ice, then stored at -80°C until sectioned. Brains were cut in the horizontal plane at 20 μm on a cryostat at -21°C. A one-in-four series of sections was rapidly thaw-mounted onto Superfrost Plus slides (Fischer Scientific, St. Louis, MO) and dried on a 60°C hotplate. The slides were then put into an x-ray cassette, along with a 14C methylmethacrylate calibration standard, and apposed to high-resolution EM1 x-ray film (Kodak, Rochester, NY). After 12-24 days of exposure, the films were developed in a film processor. Alternate sections were stained for cytochrome oxidase (CO) activity following the protocol of Tucci et al., (1999).

Tissue Analysis

From the 2-DG exposed film, optical density (OD) measurements were taken from the ipsilateral (relative to the manipulated ear) and contralateral IC, and from AI and AAF of both the ipsilateral and contralateral hemispheres. CO stained sections were used to help identify structural boundaries. Density measurements were compiled by an investigator who was blind to the experimental conditions, and the measures replicated to assure reliability. The OD of the 2-DG films were obtained using NIH Image software. Images were captured using a Zeiss Axioskop microscope equipped with a Dage-MTI digital camera (Model CCD-72SX) coupled to frame grabber (Scion LG3) and a Macintosh G3 computer. Prior to measuring OD of auditory structures, the image analysis software was calibrated using the radioactive standards exposed with each sheet of film. Following calibration, auditory regions were identified in the film and the standardized OD measured.

Inferior Colliculus

A series of three sections was chosen for analysis from the 50% level of the dorsal-ventral dimension of the IC (see Fig. 1), sampling a region of the central nucleus of the IC approximately 180 μm thick. Boundaries of the central nucleus of the IC in the films were estimated using neighboring CO stained sections. A 50 × 50 μm “window” was used to sample the OD in the lateral (low-frequency region; e.g., arrow in Fig. 1) of the IC, and the standardized OD from the three sections were then averaged to yield an OD measure of that IC.

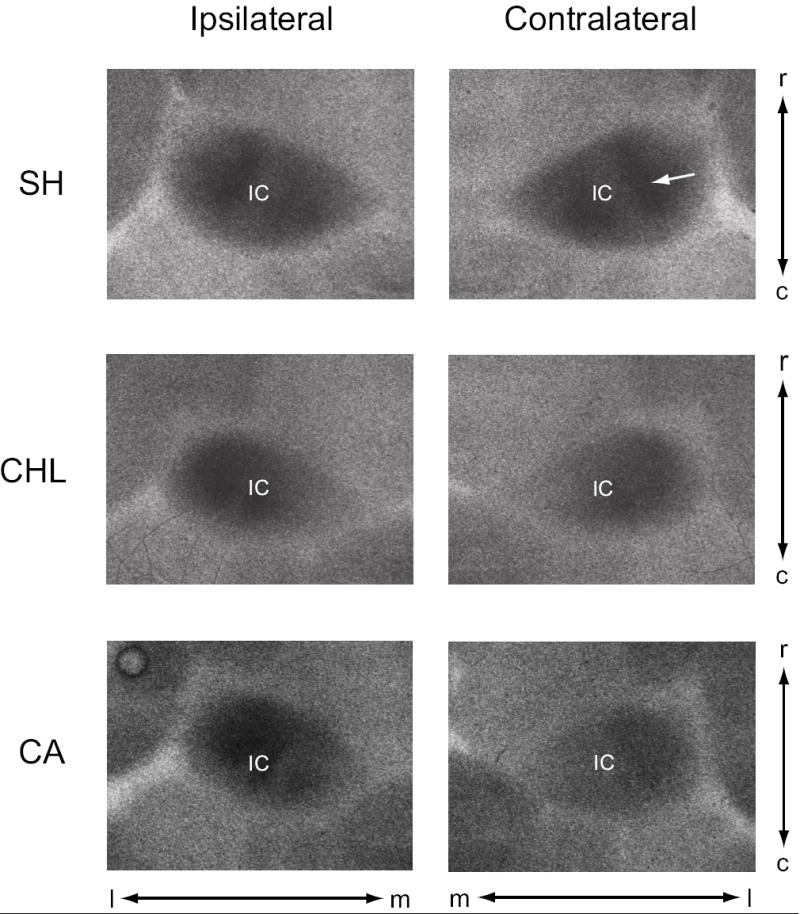

Figure 1.

Examples of 2-DG radiographs from horizontal sections through mid-level IC, corresponding roughly to horizontal levels H1000 and H1160 of Cant and Benson’s (2005) the atlas of the gerbil IC. These images are actual screen shots (un-manipulated) of the exposed x-ray film from IC ipsilateral and contralateral to the manipulated ear. In SH conditions, the levels of 2-DG uptake are identical in the ipsilateral and contralateral IC, and there is little difference in uptake in the ipsilateral IC between the SH, CHL or CA conditions. However, uptake in contralateral IC is below SH levels for both CHL and CA animals. OD measures were taken from the lateral (low-frequency region of IC) band of activity (e.g., arrow in SH of contralateral IC). IC, inferior colliculus; c, caudal; l, lateral; m, medial; r, rostral.

Medial Geniculate

The MG was sampled in a manner similar to the IC (see Fig 2). Three sections were chosen and sampled from the 50% dorsal-ventral dimension of the ventral nucleus of the MG, and a 50 × 50 μm window used to sample the OD in the lateral (low-frequency region; e.g., arrow in Fig. 2) of the MG. Standardized OD from the three sections were then averaged to yield an OD measure of that MG.

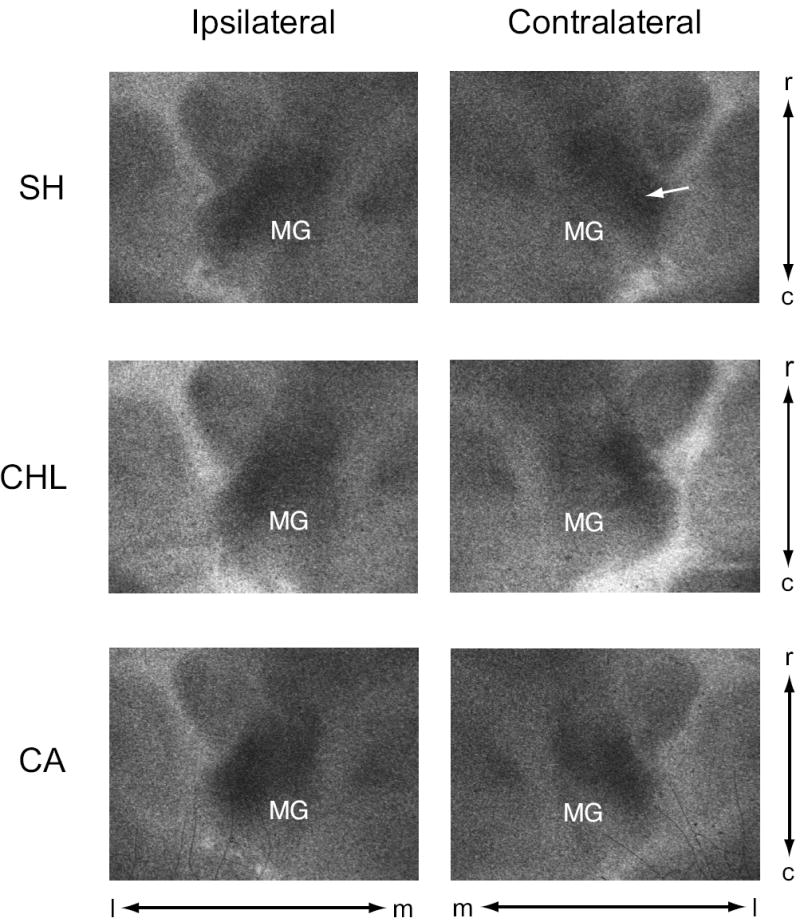

Figure 2.

Examples of 2-DG radiographs from horizontal sections through mid-level MG, images are screen shots (un-manipulated) of the exposed x-ray film from MG ipsilateral and contralateral to the manipulated ear. OD measures were taken from the lateral (low-frequency region of MG) band of activity (e.g., arrow in SH of contralateral MG). MG, medial geniculate; c, caudal; l, lateral; m, medial; r, rostral.

Auditory Cortex

A series of five sections per hemisphere was chosen to measure the OD of auditory cortex, again at the 50% level of its dorsal-ventral dimension. Using the dorsal aspect of the caudate nucleus as a rough marker for the dorsal boundary of auditory cortex (Budinger et al, 2000; Hutson et al, 2004), mid-level auditory cortex falls approximately 1.5 mm below the dorsal surface of the caudate nucleus. At this level, two bands of high 2-DG uptake are visible. A rostral band marking the AAF, and a more caudal band marking AI were visible in each section (see Fig. 3; and Thomas et al., 1993; Scheich et al., 1993). Once AI and AAF were identified, a 50 × 50 μm window was used to sample the OD in cortical layer IV of each region (e.g., arrow in Fig 3). Together, the five windows sampled 2-DG uptake over a region of approximately 340 μm through the middle of auditory cortex. The standardized OD from the five sections were averaged to yield an OD measure of AI and AAF in each hemisphere.

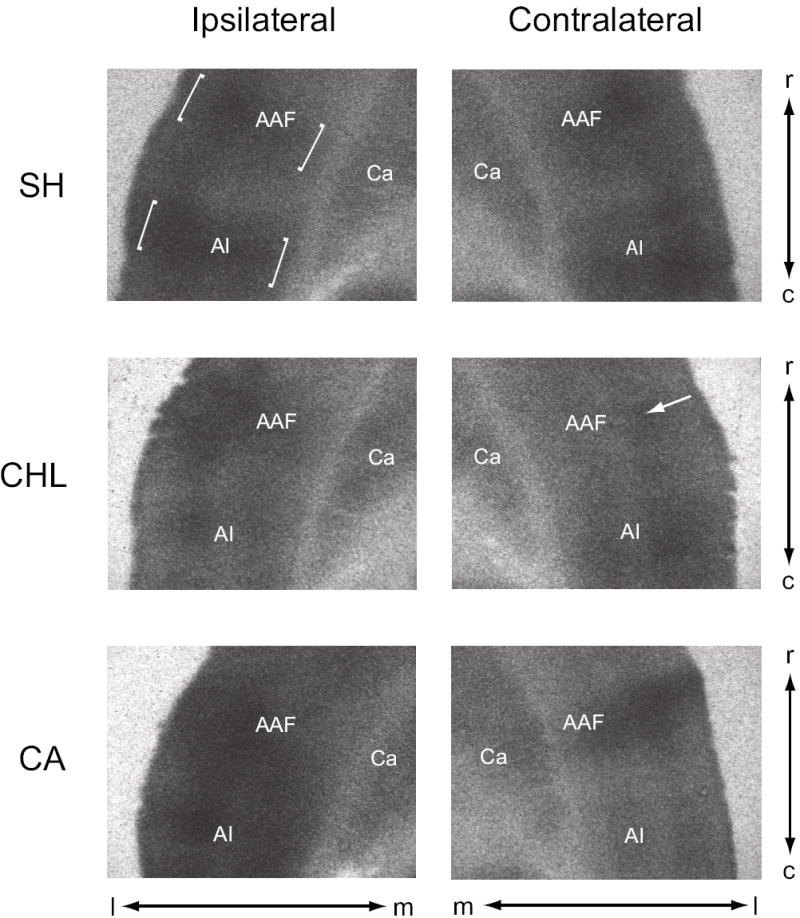

Figure 3.

Examples of 2-DG radiographs from horizontal sections through mid-level auditory cortex, images are screen shots (un-manipulated) of the exposed x-ray film from cortex ipsilateral and contralateral to the manipulated ear. In SH animals, note two distinct band of activity in auditory cortex (e.g., brackets in SH of ipsilateral cortex), a rostral band corresponding to AAF (anterior auditory field) and a caudal band corresponding to AI (primary auditory cortex). OD measures were taken from layer IV (e.g., arrow in AAF of contralateral CHL), which was identified as the area just dorsal to the stripe of low uptake present in layer V. Ca, caudate nucleus; c, caudal; l, lateral; m, medial; r, rostral.

Data Analysis

OD values for each structure were then corrected for background levels by dividing OD values from each structure by the OD of a well-defined, neutral structure unlikely to be affected by our manipulations. To facilitate comparison with other studies (e.g., Stuermer and Scheich, 2000), we used the corpus callosum as the neutral structure. The OD of the corpus callosum was sampled at the midline in one section at the level of auditory cortex using a 50 × 50 μm window. Dividing the absolute OD measures by the OD of the corpus callosum yields a relative OD (OD rel) value for each structure. The OD rel values were then analyzed across the experimental conditions, and subject to analysis of variance and Fishers Protected Levels t-test procedures using StatView software.

Sham Corrections

This correction was used to estimate the magnitude of the difference between the experimental and sham procedures. Each auditory structure from the experimental conditions was compared to the corresponding structure in the sham condition according to the formula:

Results

We used uptake of 2-DG as a tool to measure activity within the auditory midbrain and forebrain of young gerbils three weeks after a unilateral hearing loss produced by middle (conductive) or inner (sensorineural) ear manipulation. We found significant left-right (ipsilateral-contralateral) differences between the IC’s subsequent to either manipulation, and the activity in contralateral IC differed significantly from SH in both conditions. No significant change in glucose uptake was observed in the MG. At the level of auditory cortex, we found no ipsilateral-contralateral differences in 2-DG activity, although activity in AAF contralateral to CHL ears was significantly reduced compared to SH and significantly lower than uptake in AAF contralateral to CA ears. Figure 1 illustrates the effects of unilateral hearing loss on the uptake of 2-DG at the level of the IC in response to low-frequency sound stimulation (1 and 2 Hz), and Figures 2 and 3 illustrate the effects on glucose uptake in the auditory thalamus and cortex. Figures 4 and 5 show OD rel measurements for the IC, MG, and auditory cortex. Figure 6 summarizes our major results, showing the sham corrected OD rel values to estimate the magnitude and direction of change (% difference from sham) in 2-DG uptake.

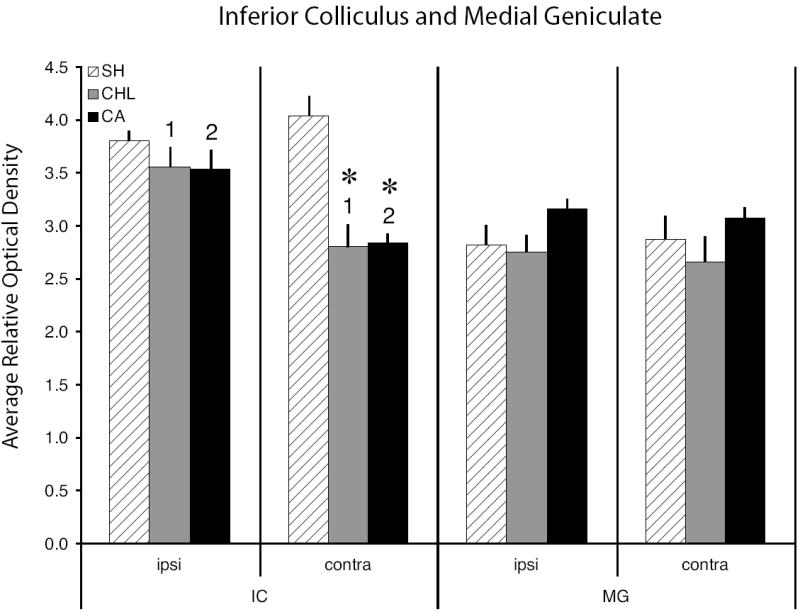

Figure 4.

Relative optical density measures from the IC and MG in sham and experimental animals. The left series of bars show 2-DG activity levels in the IC both ipsilateral and contralateral to the manipulated ear, the right series shows activity levels measured in the MG. Uptake in contralateral IC was significantly lower than in ipsilateral IC for both the CHL animals (numerals 1; P < 0.0003) and CA animals (numerals 2; P < 0.0007). Asterisks = relative optical density values in experimental animals that differed significantly from SH animals, P < 0.001). Error bars = one standard error of the mean.

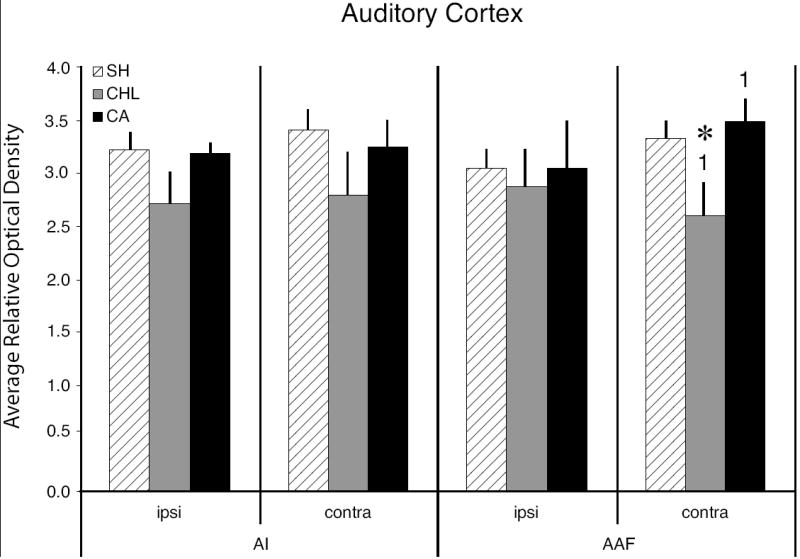

Figure 5.

Relative optical density measures from auditory cortex in sham and experimental animals. The left series of bars show 2-DG activity levels in AI, the right series shows activity levels measured in AAF. Note that the only significant differences found in cortex were in the contralateral AAF, where CHL animals differed from SH animals (asterisk; P < 0.03) and from CA animals (numerals 1; P < 0.01). Error bars = one standard error of the mean.

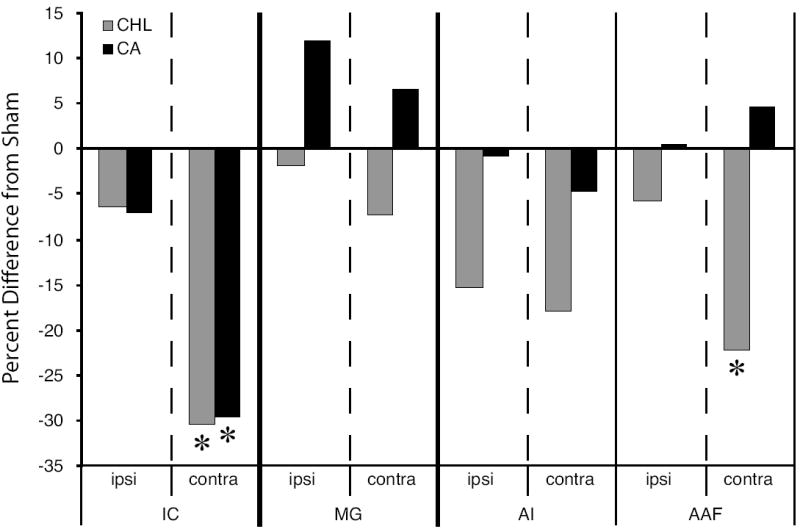

Figure 6.

Summary of the effect of ear manipulation on 2-DG uptake expressed as percent difference from sham levels. Asterisks denote the structures that were significant different from SH (see Figs. 4 and 5). At the level of the IC, both CHL and CA manipulations significantly reduced uptake in the IC contralateral to the manipulated ear. At the level of the auditory cortex, CA did not significantly affect 2-DG uptake in the AI or AAF either ipsilateral or contralateral to the manipulated ear. However, in CHL animals uptake in AI and AAF was reduced relative to SH, although only the decrease in contralateral AAF was significantly different from SH. Uptake levels differed significantly between CHL and CA animals only in the contralateral AAF. ipsi, ipsilateral to manipulated ear; contra; contralateral to manipulated ear.

Effect of Hearing Loss on 2-DG Uptake in Inferior Colliculus

Our SH animals demonstrate that under normal conditions, activity levels are identical between the ipsilateral (left) and contralateral (right) IC (see Figs. 1 and 4). Neither CHL nor CA altered the pattern of 2-DG uptake in the ipsilateral IC, though in both conditions glucose uptake levels were depressed compared to SH. However, CHL and CA altered the pattern of 2-DG activity of the contralateral IC. The OD rel of the contralateral IC for both CHL and CA was significantly lower than SH (P < 0.0001 in both conditions). Furthermore, comparing the IC’s from both sides of the brain in the CHL and CA manipulation groups show that in both conditions, the OD rel of the contralateral IC was significantly lower than the ipsilateral IC (CHL, P < 0.0003; CA, P < 0.0007).

Effect of Hearing Loss on 2-DG Uptake in Medial Geniculate

Within the auditory thalamus, 2-DG activity in the ventral nucleus of the MG of SH animals was identical on both sides of the brain, as was activity in the CHL and CA animals. Compared to SH animals, CHL depressed 2-DG uptake (bilaterally) and CA elevated uptake (bilaterally), but not by a significant amount in either hearing loss condition (see Fig 4). Variation in uptake between CHL and CA animals was also not significant (ipsilateral, P = 0.1; contralateral P = 0.09).

Effect of Hearing Loss on 2-DG Uptake in Auditory Cortex

At the cortical level, SH animals show two bands of activity in auditory cortex, one within AI and a second within AAF (see brackets in Fig. 3). The OD rel of the bands in AI and the bands in AAF are similar in both hemispheres. Hearing loss effects on neuronal activity in auditory cortex, as measured by glucose uptake in response to low-frequency sound stimulation, are significantly different from SH in the CHL condition but not the CA condition (see Fig. 5). Subsequent to CHL, glucose uptake in AI was lower (though not significantly) than SH animals, and the reduction greater on the side contralateral to the manipulated ear (ipsilateral AI vs. SH, P = 0.13; contralateral AI vs. SH, P = 0.09). In AAF ipsilateral to the CHL ear, uptake was reduced compared to SH (not significantly). However, in AAF contralateral to the CHL ear, uptake was significantly lower than in SH animals (P < 0.03). Furthermore, there was a significant difference in uptake between the CHL and CA groups in contralateral AAF (P < 0.01).

Summary of Results

The major results of this study on hearing loss and glucose uptake (summarized in Figure 6) are as follows: Ipsilateral IC: Compared to SH, CHL and CA animals show little change in their level of glucose uptake. Contralateral IC: Unilateral CHL and CA result in a significant reduction in glucose uptake. Ipsilateral and Contralateral MG: Compared to SH, CA increased glucose uptake and CHL decreased uptake, though not by significant amounts. Ipsilateral and Contralateral AI: CHL and CA decreased glucose activity in both hemispheres, although the magnitude of change in CHL animals was greater than CA animals, the differences did not reach significance levels. Ipsilateral AAF: no significant changes resulting from CHL or CA. Contralateral AAF: CHL results in a significant decrease in glucose activity. CA resulted in non-significant elevation in activity.

Discussion

Overall the results of this study conform to our earlier investigations, showing that unilateral CHL (and CA) significantly reduce glucose activity in the contralateral IC (e.g., Tucci et al., 1999). At the level of auditory cortex, CHL significantly reduces activity in the contralateral AAF. This suggests that conductive impairment does have a measurable effect on auditory cortex, and thus may contribute to potential cognitive dysfunctions related to processing sounds and speech. To explain our findings of 2-DG uptake in auditory cortex, we will first consider the contribution of activity in sub-cortical auditory centers, primarily the IC, then activity among the projections to auditory cortex, and finally possible developmental effects on cortical activity.

Ascending Auditory Pathways

The ascending projections to the gerbil IC are similar in origin and proportion as in other mammals (Cant and Benson, 2006). The IC receives multiple inputs from lower order auditory structures on both sides of the brain, such that acoustic information arriving at each ear reaches each IC directly (via projections from the cochlear nucleus) or indirectly (via cochlear nucleus projections to the superior olives and nuclei of the lateral lemniscus). Beyond the IC, the ascending projections are predominantly unilateral, that is, the IC of one side projects heavily to its ipsilateral MG, and the MG projects to its ipsilateral auditory cortex (e.g., Moore and Goldberg, 1963; Anderson et al., 1980a,b).

Single unit recordings from the low-frequency regions of the IC show strong excitatory responses to stimuli presented to the contralateral ear, and excitatory or inhibitory responses to stimulation of the ipsilateral ear (e.g., Stanford et al., 1992; Brukner and Rübsamen, 1995). Under binaural stimulation these units display a variety of interaction effects, e.g., binaurally excited units, units excited by stimulation of the contralateral ear and inhibited (reduced firing rate) upon binaural stimulation (EI cells), or excitation by contralateral stimulation that is unaffected under binaural conditions. Typically, inhibition is stronger for low-frequency EI units than for high-frequency units (Brukner and Rübsamen, 1995).

Subsequent to CHL, there is no reason to suspect a reduction in the number of inputs to the contralateral IC compared to SH, and the IC ipsilateral to the intact ear will continue to receive excitatory and inhibitory inputs from brainstem nuclei responsible for processing low-frequency sound (see Hutson, 1997 for a review). However, after CA, the ascending projections to the IC will be reduced in number driven by an acoustic stimulus and arise solely from one ear. Although the 2-DG method shows activity at synapses, i.e., inputs to the IC, it cannot distinguish between excitation and inhibition (Nudo and Masterton, 1986). However, in combination with the existing electrophysiological evidence, i.e., the output properties of IC units, we can examine the input/output transformations that may occur as a consequence of hearing loss.

Sub-Cortical Effects of Unilateral Hearing Loss

Reduced glucose uptake in the IC contralateral to either CHL or CA has been demonstrated previously in the gerbil (e.g., Woolf et al., 1983; Caird et al., 1991; Tucci et al., 1999), and other species (e.g., Wallace et al., 1997). Certain similarities and differences exist between our current data and those of Tucci et al (1999). For example, after CA the magnitude of the decreased uptake in contralateral IC is slightly greater in Tucci et al (1999) than in the present material. This difference may due to the different sound stimuli used in the two experiments, and differing methods of sampling the IC. Using a broad-band sound stimulus, Tucci et al (1999) found the percent difference from sham in contralateral IC is on the order of 40% for P21 animals 3 weeks after the onset of hearing loss. In the present study, using a low frequency stimulus, the percent difference from sham is on the order of 30%. This small difference may be a reflection of variation in sampling method and plane of section. Here, we sampled IC regions of interest with a 50 × 50 μm window in the horizontal plane, whereas Tucci et al (1999) sampled the entire IC in the transverse plane. In both studies, following unilateral CHL, uptake in the contralateral IC is reduced by approximately 30% compared to sham. Despite these potential differences, both studies show that CHL and CA reduce glucose consumption in the IC contralateral to the manipulated ear. However, the mechanisms responsible for the decrease in uptake must be different for CHL than for CA.

For CA, there is a reduction in the number of driven inputs to the IC, and therefore afferent activity, that is sufficient to explain the reduction in 2-DG uptake. Following CHL, there is no reduction in the number of projections to the IC, yet the 2-DG data indicates a significant reduction in activity compared to SH. For this to occur, there must be a functional reduction in ascending activity related to the CHL manipulation. Following CHL, 2-DG uptake by the ipsilateral cochlear nucleus and among brainstem nuclei receiving projections from it, are significantly reduced (Tucci et al., 1999). This implies that the attenuation produced by CHL, and the reduction in 2-DG uptake in the contralateral IC, is the result of decreased sound intensity at the affected ear, and a subsequent reduction of activity driven by that ear.

Furthermore, comparing our results to 2-DG reports by others suggests that over time there may be restoration of metabolic activity in the IC of young animals. In our current 2-DG material, and those of Tucci et al (1999), we demonstrate a decrease in neuronal activity in the IC contralateral to the manipulated ear to be on the order of 30-40% after a three week survival period. However, Tucci et al (1999) also measured 2-DG uptake in animals 2 days following ear manipulation, and found the percent difference from SH was on the order of 50 – 60%, suggesting that for CHL (and CA) there may be some recovery of activity between 2 days and three weeks. Following unilateral CA, electrophysiological evidence suggests the proportion of units in the opposite IC excited by stimulation of the ipsilateral (intact) ear increases dramatically over time (e.g., McAlpine et al., 1997; Irvine et al., 2003). The mechanism for this change in response characteristics appears to be a rapid reduction in functional inhibition from lemniscal inputs or within the IC itself (e.g., Mossop, et al., 2000; Vale et al., 2004). Thus, it is possible that while both CHL and CA animals demonstrate reduced 2-DG uptake in the IC contralateral to the manipulated ear (relative to SH animals; see Fig. 4), reflecting the total activity of ascending inputs to the IC (Nudo and Masterton, 1986; Brown et al., 1997), the nature of the outputs from that IC may be quite different in each condition. Given that unilateral CA eliminates information derived from one ear, while unilateral CHL only diminishes its central representation, CHL animals likely maintain some level of inhibition in the IC ipsilateral to the intact ear (Xu and Jen, 2001) while in CA animals the IC units have become more “excitable”. Therefore, it would follow that the level of excitation present in the projection from the IC contralateral to the manipulated ear to the MG would be higher in CA animals than in CHL animals, affecting the activity in thalamocotical projections to auditory cortex, and the level of 2-DG uptake in auditory cortex. If this is true, then the MG must be driven at near normal levels following CA. There is evidence that this may be the case in our own material (see Figs. 4 and 6) and in material of others. In adult guinea pigs, Sasaki et al (1980) showed that 2-DG activity was reduced in the contralateral IC and contralateral MG shortly after unilateral CA (1-2 hours), but after 10-48 days survival, the activity in IC and MG rebounds, with little noticeable difference from control animals after 27 days. Thus, in CA animals, a change in the relative proportion of IC units that are excited by stimulation of the ipsilateral ear may be sufficient to drive auditory cortex at near normal levels. For CHL animals, if inhibition in the IC remains higher than CA animals, the cumulative output of IC neurons might be less excitatory than normal, and ultimately reduce activity in auditory cortex.

The small differences we observed in 2-DG uptake by the MG contralateral to the manipulated ear did not differ significantly from SH (see Figs. 4 and 6). Thus, 21 days after hearing loss, the synaptic activity in the MG is at near normal levels. However, as in the IC, this does not imply similar functional processing, only the presence of active synapses. Neurons of the MG can be excited or inhibited by stimuli presented to either ear, and units typically respond with transient or sustained excitation (e.g., Aitkin and Dunlop, 1968; Aitkin and Webster, 1972; Aitkin and Prain, 1974; Calford, 1983; Stanford et al., 1992). Following CA, the available evidence indicates that the ascending projection from the IC contralateral to the manipulated ear would be totally or predominately excitatory. Without inhibitory interaction, it would follow that MG units likely maintain sustained excitatory responses to stimulation, as would their projections to auditory cortex. For CHL animals, the projection from IC to MG contains an inhibitory component. Given that the intensity imbalance at the ears favors increased inhibition in the IC contralateral to the manipulated ear, this projection is less likely to support sustained excitatory discharges in the MG. Rather, they are more likely to result in transient excitation, or perhaps even sustained inhibition (Aitkin and Dunlop, 1968; Stanford et al, 1992). In this manner, the functional properties of projections to auditory cortex in CHL animals would differ from both SH and CA animals, as would activity driven 2-DG uptake in auditory cortex. This interpretation is supported by results from single unit recordings in AI (e.g., Reale and Kettner, 1986; Kelly and Sally, 1988) and optical recording measures (Hosokawa et al., 1999), demonstrating that as the intensity of a stimulus increases in one ear (similar to the non-manipulated ear of our CHL animals), the activity in auditory cortex ipsilateral to that ear decreases.

Cortical Reaction to Unilateral Hearing Loss

Our results suggest that auditory cortex responds differently to a unilateral hearing loss induced by CA or CHL. For animals in our CA group, after a three week recovery period, there was little evidence of a difference in 2-DG uptake between CA and SH animals. Similar findings appear in the tinnitus literature (e.g., Wallhäusser-Franke et al., 1996), and it may be possible that 2-DG uptake in our CA animals was influenced by their having experienced some form of central tinnitus (Eggermont, 2003; Eggermont and Roberts, 2004). 2-DG results from salicylate-induced tinnitus in gerbils (Wallhäusser-Franke et al., 1996) demonstrate (compared to controls) reduced uptake in the IC together with continued uptake in MG and auditory cortex. However, in that experiment 2-DG activity was measured in animals kept in a quiet environment, while in the present study, the auditory system was actively driven by an external stimulus. Nonetheless, we cannot rule out the possibility that in our CA animals the 2-DG activity in auditory cortex (and subcortical structures as well) was influenced by processes related to central tinnitus.

The opposite is true for our CHL animals, where 21 days after CHL the 2-DG activity in auditory cortex remains below levels observed in age-matched SH animals. Behavioral studies in rodents (e.g., Wetzel et al., 1998; Rybalko et al., 2006) suggest an asymmetry in cortical processing, where the right hemisphere has dominance for discrimination of frequency-modulated tones. It is possible that our observations of 2-DG uptake in contralateral cortex are confounded by our manipulation of the left ear, such that if the right ear were manipulated, the results in left cortex may not be identical to our current findings. Two lines of evidence argue against this. First, our stimulus consisted of an alternating 1 and 2 kHz tone, not a frequency-modulated sweep. Second, a right ear CHL in guinea pigs (Kauer et al., 1982) reduces 2-DG activity in contralateral IC and contralateral MG similar to the present study. Thus, it is unlikely that our results present a bias based on asymmetry in cerebral functions.

Effect of Unilateral CHL on Cortical Connections

AI and AAF receive inputs from the ipsilateral MG and from other regions of auditory cortex, and both receive a tonotopically arranged input from similar regions of the MG (ventral division and rostral pole). The ventral division of MG has a larger projection to AI than to AAF, while the rostral pole of MG has a larger projection to AAF than AI (e.g., Morel and Imig, 1987; Lee et al., 2004a,b). Thus it is possible that the reduced 2-DG activity in auditory cortex contralateral to CHL reflects a change in thalamocortical activity originating from different regions of the MG.

Recent evidence indicates that cortical inputs to AI and AAF are far greater in magnitude than are thalamic inputs. For example, in gerbil approximately 23% of the projections to AI arise from the MG, while approximately 57% originate from other regions of auditory cortex (Scheich et al., 2007). In cat, the proportion of inputs are similar for both AI and AAF: approximately 15% arise from thalamus, 15% are commissural, and approximately 70% originate from cortical regions of the same hemisphere (Lee et al., 2004b). Changes in activity within the commissural projections could have contributed to our 2-DG results, but a more likely explanation for the decreased activity seen AAF contralateral to CHL lies in the massive projections from homolateral cortical regions. In gerbil, AI projects to virtually all ipsilateral regions of auditory cortex, including a heavy projection to the ipsilateral AAF, but AAF has a much smaller reciprocal projection to ipsilateral AI (Budinger et al., 2000). Thus, any reduction of activity in AI would have an effect on activity in the ipsilateral AAF.

It would seem that our observations of a significant reduction in 2-DG uptake in AAF contralateral to CHL are best explained as a combination of (1) a reduced excitation (or increased inhibition) among the outputs from the IC contralateral to CHL, reducing the level of activity in MG projections to auditory cortex and (2) the sub-optimal activity in contralateral AI followed by sub-optimal activity in the AI projection to AAF. Together, the reduced thalamocortical activity and reduced AI activity may have resulted in a significant reduction of 2-DG uptake in contralateral AAF.

Developmental Effects of Unilateral CHL

Our results of CHL affects on contralateral auditory cortex differ from those reported by Stuermer and Scheich (2000). In our material, we found no evidence that CHL increased glucose activity in contralateral AI, while there was a significant decrease in activity in contralateral AAF. One possible explanation for these differences is the method of producing CHL; malleus removal versus surgical atresia. However, this difference alone would not likely have produced such disparate results. A more plausible explanation lies in the time of CHL induction. We induced CHL at age P21, after the onset of hearing had taken place. Our observations then apply to central auditory system changes that occur after unilateral CHL in a system that has experienced normal binaural development. Stuermer and Scheich (2000) induced unilateral CHL at P9, well before the onset of hearing, and thus it is not surprising that the effects on the auditory system are quite different than ours, as those animals never developed normal levels of binaural hearing.

Stuermer and Scheich (2000) also measured the distance between ‘stripes’ of 2-DG activity in AAF and AI, finding a slight change following hearing loss, but these authors were cautious in attributing this to a plastic change in the tonotopic map. Although our results do not directly address issues of cortical plasticity, these two studies together suggest that unilateral CHL has significant effects on auditory cortex, despite the method of producing CHL. Most importantly, they demonstrate that conductive impairment at a very early age may induce re-organization within auditory cortex, where CHL occurring later in development may promote a different mode or temporal sequence of cortical re-organization. These different modes may include potential plastic changes (e.g., Irvine, 2007) or perturbed expression of neurotransmitters or their receptors (e.g., Cherubini et al., 1991; Gao et al., 1999; Kilman et al, 2002; Yu et al., 2006). Regardless of the underlying mechanism, our main observation remains that in response to low frequency sound stimulation, CHL, but not CA, decreases activity in auditory cortex.

Perceptual Consequences of Unilateral CHL

The finding that activity in auditory cortex contralateral to CA remains at near normal levels does not imply that auditory cortical functions remain near normal. It implies simply that the auditory system contralateral to CA can still be driven, and that thalamocortical projections are intact and functional after CA (Stanton and Harrison, 2000). Nor do our findings of decreased activity in auditory cortex contralateral to CHL suggest an irretrievable loss of cortical function. For example, human performance on a number of auditory tasks improve after repair of congenital unilateral CHL, however, deficits in sound localization persist as do deficits in complex speech intelligibility (e.g., Wilmington et al., 1994). Given that amplitude and frequency modulation are substantial components of speech, the effect of CHL on cognitive and perceptual functions may be related to how the auditory system parcels the analysis of rapidly changing temporal stimuli, that is, a difference between AI and AAF (e.g., Linden et al., 2003). If AAF is truly preferential for the analysis of rapidly changing stimuli, such as speech, then our observed decrease in the level of activity in AAF contralateral to CHL in young animals suggests that without normal binaural acoustic experience, the ability to resume normal linguistic functioning after repair of CHL may be compromised. Thus our findings may explain, in part, the prolonged period of adjustment to repair of unilateral CHL reported by human subjects (e.g., Sperling and Patel, 1999).

Abbreviations

- AAF

anterior auditory field

- AI

primary auditory cortex

- CA

cochlear ablation

- Ca

caudate nucleus

- CHL

conductive hearing loss

- contra

contralateral

- IC

inferior colliculus

- ipsi

ipsilateral

- MG

medial geniculate

- SH

sham

- 2-DG

2-deoxyglucose

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Aitkin LM, Dunlop CW. The interplay of excitation and inhibition in the cat medial geniculate body. J Neurophysiol. 1968;31:44–61. doi: 10.1152/jn.1968.31.1.44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aitkin LM, Prain SM. Medial geniculate body: unit responses in awake cat. J Neurophysiol. 1974;37:512–521. doi: 10.1152/jn.1974.37.3.512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aitkin LM, Webster WR. Medial geniculate body of the cat: organization and responses to tonal stimuli of neurons in the ventral division. J Neurophysiol. 1972;35:365–380. doi: 10.1152/jn.1972.35.3.365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andersen RA, Roth GL, Aitkin LM, Merzenich MM. The efferent projections of the central nucleus and pericentral nucleus of the inferior colliculus in the cat. J Comp Neurol. 1980a;194:649–662. doi: 10.1002/cne.901940311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson RA, Knight PL, Merzenich MM. The thalamocortical and corticothalamic connections of AI, AII, and the anterior auditory field (AAF) in the cat: evidence for two largely segregated systems of connections. J Comp Neurol. 1980b;194:663–701. doi: 10.1002/cne.901940312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown M, Webster WR, Martin RL. Intensity and frequency functions of [14C]2-deoxyglucose labelling in the central nucleus of the inferior colliculus in the cat. Hear Res. 1997;104:73–89. doi: 10.1016/s0378-5955(96)00186-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruckner S, Rübsamen R. Binaural response characteristics in isofrequency sheets of the gerbil inferior colliculus. Hear Res. 1995;86:1–14. doi: 10.1016/0378-5955(95)00048-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Budinger E, Heil P, Scheich H. Functional organization of auditory cortex in the Mongolian gerbil (Meriones unguiculatus). III. Anatomical subdivisions and corticocortical connections. Eur J Neurosci. 2000;12:2425–2451. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.2000.00142.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caird D, Scheich H, Klinke R. Functional organization of auditory cortical fields in the mongolian gerbil (Meriones unguiculatus): binaural 2-deoxyglucose patterns. J Comp Physiol A. 1991;168:13–26. doi: 10.1007/BF00217100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calford MB. The parcellation of the medial geniculate body of the cat defined by auditory response properties of single units. J Neurosci. 1983;3:2350–2364. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.03-11-02350.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calford MB. Dynamic representational plasticity in sensory cortex. Neurosci. 2002;111:709–738. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(02)00022-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cant NB, Benson CG. An atlas of the inferior colliculus of the gerbil in three dimensions. Hearing Res. 2005;206:12–27. doi: 10.1016/j.heares.2005.02.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cant NB, Benson CG. Organization of the inferior colliculus of the gerbil (Meriones unguiculatus): differences in distribution of projections from the cochlear nuclei and the superior olivary complex. J Comp Neurol. 2006;495:511–528. doi: 10.1002/cne.20888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cherubini E, Gaiarsa JL, Ben-Ari Y. GABA: an excitatory transmitter in early postnatal life. TINS. 1991;14:515–519. doi: 10.1016/0166-2236(91)90003-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clopton BM, Silverman MS. Changes in latency and duration of neural responding following developmental auditory deprivations. Exp Brain Res. 1978;32:39–47. doi: 10.1007/BF00237388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eggermont JJ. Central tinnitus. Auris Nasus Larynx. 2003;30:7–12. doi: 10.1016/s0385-8146(02)00122-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eggermont JJ, Roberts LE. The neuroscience of tinnitus. TINS. 2004;27:676–682. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2004.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finck A, Schneck CD, Hartman AF. Development of cochlear function in the neonate Mongolian gerbil (Meriones unguiculatus) J Comp Physiol Psych. 1972;78:375–380. doi: 10.1037/h0032373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao W-J, Newman DE, Wormington AB, Pallas SL. Development of inhibitory circuitry in visual and auditory cortex of postnatal ferrets: immunocytochemical localization of GABAergic neurons. J Comp Neurol. 1999;409:261–273. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-9861(19990628)409:2<261::aid-cne7>3.0.co;2-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glendenning KK, Baker BN, Hutson KH, Masterton RB. Acoustic chiasm V: inhibitory and excitatory neurotransmitters in LSO’s ipsilateral and contralateral projections. J Comp Neurol. 1992;319:100–122. doi: 10.1002/cne.903190110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hosokawa Y, Horikawa J, Nasu M, Taniguchi I. Spatiotemporal representation of binaural difference in time and intensity of sound in the guinea pig auditory cortex. Hear Res. 1999;134:123–132. doi: 10.1016/s0378-5955(99)00073-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hutson K. The ipsilateral auditory pathway: a psychobiological perspective. In: Christman S, editor. Advances in Psychology, vol 123: Cerebral Asymmetries in Sensory and Perceptual Processing. Elsevier Science B.V.; 1997. pp. 383–466. [Google Scholar]

- Hutson K, Benson C, Cant N. Anatomical definition of auditory cortex in the gerbil. Assoc Res Otolaryngol Abst. 2004:194. [Google Scholar]

- Imaizumi K, Priebe NJ, Crum PAC, Bedenbaugh PH, Cheung SW, Schreiner CE. Modular functional organization of cat anterior auditory field. J Neurophysiol. 2004;92:444–457. doi: 10.1152/jn.01173.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imig TJ, Morel A. Organization of the thalamocortical auditory system in the cat. Ann Rev Neurosci. 1983;6:95–120. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ne.06.030183.000523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imig TJ, Reale RA. Patterns of cortico-cortical connections related to tonotopic maps in cat auditory cortex. J Comp Neural. 1980;192:293–332. doi: 10.1002/cne.901920208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Irvine DRF. Auditory cortical plasticity: does it provide evidence for cognitive processing in the auditory cortex? Hear Res. 2007;229:158–170. doi: 10.1016/j.heares.2007.01.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Irvine DRF, Rajan R, Smith S. Effects of restricted cochlear lesions in adult cats on the frequency organization of the inferior colliculus. J Comp Neurol. 2003;467:354–374. doi: 10.1002/cne.10921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jen PH-S, Xu L. Monaural middle ear destruction in juvenile and adult mice: effects on responses to sound direction in the inferior colliculus ipsilateral to the intact ear. Hear Res. 2002;174:249–259. doi: 10.1016/s0378-5955(02)00699-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jenkins WM, Merzenich MM. Role of cat primary auditory cortex for sound-localization behavior. J Neurophysiol. 1984;52:819–847. doi: 10.1152/jn.1984.52.5.819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kauer JS, Nemitz JW, Sasaki CT. Tinnitus aurium: fact … or fancy. Laryngoscope. 1982;92:1401–1407. doi: 10.1288/00005537-198212000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly JB, Potash M. Directional responses to sounds in young gerbils (Meriones unguiculatus) J Comp Psychol. 1986;100:37–45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly JB, Sally SL. Organization of auditory cortex in the albino rat: binaural response properties. J Neurophysiol. 1988;59:1756–1769. doi: 10.1152/jn.1988.59.6.1756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kilgard MP, Vazquez JL, Engineer ND, Pandya PK. Experience dependent plasticity alters cortical synchronization. Hear Res. 2007;229:171–179. doi: 10.1016/j.heares.2007.01.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kilman V, van Rossum MCW, Turrigiano GG. Activity deprivation reduces miniature IPSC amplitude by decreasing the number of postsynaptic GABAA receptors clustered at neocortical synapses. J Neurosci. 2002;22:1328–1337. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-04-01328.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knight PA. Representation of the cochlea in the anterior auditory field (AAF) of the cat. Brain Res. 1977;130:447–467. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(77)90108-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee CC, Schreiner CE, Imaizumi K, Winer JA. Tonotopic and heterotopic projection systems in physiologically defined auditory cortex. Neurosci. 2004a;128:871–877. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2004.06.062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee CC, Imaizumi K, Schreiner CE, Winer JA. Concurrent tonotopic processing streams in auditory cortex. Cereb Cortex. 2004b;14:441–451. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhh006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linden JF, Liu RC, Sahani M, Schreiner CE, Merzenich MM. Spectrotemporal structure of receptive fields in areas AI and AAF of mouse auditory cortex. J Neurophysiol. 2003;90:2660–2675. doi: 10.1152/jn.00751.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lomber SG, Malhotra S, Hall AJ. Functional specialization in non-primary auditory cortex of the cat: Areal and laminar contributions to sound localization. Hear Res. 2007;229:31–45. doi: 10.1016/j.heares.2007.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McAlpine D, Martin RL, Mossop JE, Moore DR. Response properties of neurons in the inferior colliculus of the monaurally deafened ferret to acoustic stimulation of the intact ear. J Neurophysiol. 1997;78:767–779. doi: 10.1152/jn.1997.78.2.767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merzenich MM, Knight PL, Roth GL. Representation of the cochlea in the primary auditory cortex of the cat. J Neurophysiol. 1975;38:231–249. doi: 10.1152/jn.1975.38.2.231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore RY, Goldberg JM. Ascending projections of the inferior colliculus in the cat. J Comp Neurol. 1963;121:109–136. [Google Scholar]

- Morel A, Imig TJ. Thalamic projections to fields A, AI, P, and VP in the cat auditory cortex. J Comp Neural. 1987;265:119–144. doi: 10.1002/cne.902650109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morel A, Garraghty PE, Kaas JH. Tonotopic organization, architectonic fields and connections of auditory cortex in macaque monkeys. J Comp Neurol. 1993;335:437–459. doi: 10.1002/cne.903350312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mossop JE, Wilson MJ, Caspary DM, Moore DR. Down-regulation of inhibition following unilateral deafening. Hear Res. 2000;147:183–187. doi: 10.1016/s0378-5955(00)00054-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nudo RJ, Masterton RB. Stimulation-induced [14C]2-deoxyglucose labeling of synaptic activity in the central auditory system. J Comp Neurol. 1986;245:553–565. doi: 10.1002/cne.902450410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips DP, Irvine DRF. Properties of single neurons in the anterior auditory field (AAF) of cat cerebral cortex. Brain Res. 1982;248:237–244. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(82)90581-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pienkowski M, Harrison RV. Tone frequency maps and receptive fields in the developing chinchilla auditory cortex. J Neurophysiol. 2005;93:454–466. doi: 10.1152/jn.00569.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Popelar J, Erre J-P, Aran J-M, Cazals Y. Plastic changes in ipsi-contralateral differences and inferior colliculus evoked potentials after in the adult guinea pig of auditory cortex injury to one ear. Hear Res. 1994;72:125–134. doi: 10.1016/0378-5955(94)90212-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qiu CX, Salvi R, Ding D, Burkard R. Inner hair cell loss leads to enhanced response amplitudes in auditory cortex of unanaesthetized chinchillas: evidence for increased system gain. Hear Res. 2000;139:153–171. doi: 10.1016/s0378-5955(99)00171-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rajan R, Irvine DRF, Wise LZ, Heil P. Effect of unilateral partial cochlear lesions in adult cats on the representation of lesioned and unlesioned cochleas in primary auditory cortex. J Comp Neurol. 1993;338:17–49. doi: 10.1002/cne.903380104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Recanzone GH, Schreiner CE, Merzenich MM. Plasticity in the frequency representation of primary auditory cortex following discrimination training in adult owl monkeys. J Neurosci. 1993;13:87–103. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.13-01-00087.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reale RA, Imig TJ. Tonotopic organization in auditory cortex of the cat. J Camp Neurol. 1980;192:265–291. doi: 10.1002/cne.901920207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reale RA, Kettner RE. Topography of binaural organization in primary auditory cortex of the cat: effects of changing interaural intensity. J Neurophysiol. 1986;56:663–682. doi: 10.1152/jn.1986.56.3.663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robertson D, Irvine DRF. Plasticity of frequency organization in auditory cortex of guinea pigs with partial unilateral deafness. J Comp Neurol. 1989;282:456–471. doi: 10.1002/cne.902820311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rutkowski R, Miasnikov AA, Weinberger NM. Characterization of multiple physiological fields within the anatomical core of rat auditory cortex. Hear Res. 2003;181:116–130. doi: 10.1016/s0378-5955(03)00182-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryan AF, Woolf NK. Development of the lower auditory system in the gerbil. In: Romand R, editor. Development of the auditory and vestibular systems 2. Amsterdam: Elsevier; 1993. pp. 243–271. [Google Scholar]

- Rybalko N, Suta D, Nwabueze-Obgo F, Syka J. Effect of auditory cortex lesions on the discrimination of frequency-modulated tones in rats. Eur J Neurosci. 2006;23:1614–1622. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2006.04688.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sasaki CT, Kauer JS, Babitz L. Differential [’4C]2-deoxyglucose uptake after deafferentation of the mammalian auditory pathway -- a model for examining tinnitus. Brain Res. 1980;194:511–516. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(80)91233-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheich H, Heil P, Langner G. Functional organization of auditory cortex in the Mongolian gerbil (Meriones unguiculatus) II. Tonotopic 2-deoxyglucose. Eur J Neurosci. 1993;5:898–914. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.1993.tb00941.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheich H, Brechmann A, Brosch M, Budinger E, Ohl FW. The cognitive auditory cortex: task-specificity of stimulus representations. Hear Res. 2007;229:213–224. doi: 10.1016/j.heares.2007.01.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schreiner CE, Urbas JV. Representation of amplitude modulation in the auditory cortex of the cat. II. Comparison between cortical fields. Hear Res. 1988;32:49–64. doi: 10.1016/0378-5955(88)90146-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulze H, Ohl FW, Heil P, Scheich H. Field-specific responses in the auditory cortex of the unanaesthetized mongolian gerbil to tones and slow frequency modulations. J Comp Physiol A. 1997;181:573–589. doi: 10.1007/s003590050141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sperling NM, Patel N. A patient-benefit evaluation of unilateral congenital conductive hearing loss presented in adulthood: should it be repaired? Laryngoscope. 1999;109:1386–1391. doi: 10.1097/00005537-199909000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stanford TR, Kuwada S, Batra R. A comparison of the interaural time sensitivity of neurons in the inferior colliculus and thalamus of the unanaesthetized rabbit. J Neurosci. 1992;12:3200–3216. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.12-08-03200.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stanton SG, Harrison RV. Projections from the medial geniculate body to primary auditory cortex in neonatally deafened cats. J Comp Neurol. 2000;426:117–129. doi: 10.1002/1096-9861(20001009)426:1<117::aid-cne8>3.0.co;2-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stiebler I, Neulist R, Fichtel I, Ehret G. The auditory cortex of the house mouse: left-right differences, tonotopic organization and quantitative analysis of frequency representation. J Comp Physiol A. 1997;181:559–571. doi: 10.1007/s003590050140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stuermer IW, Scheich H. Early unilateral auditory deprivation increases 2-deoxyglucose uptake in contralateral auditory cortex of juvenile mongolian gerbils. Hear Res. 2000;146:185–199. doi: 10.1016/s0378-5955(00)00113-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sumner CJ, Tucci DL, Shore SE. Response of ventral cochlear nucleus neurons to contralateral sound after conductive hearing loss. J Neurophysiol. 2005;94:4234–4243. doi: 10.1152/jn.00401.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Syka J. Plastic changes in the central auditory system after hearing loss, restoration of function, and during learning. Physiol Rev. 2002;82:601–636. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00002.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi H, Nakao M, Kaga K. Interfield differences in intensity and frequency representation of evoked potentials in rat auditory cortex. Hear Res. 2005;210:9–23. doi: 10.1016/j.heares.2005.05.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi K, Hishida R, Kubota Y, Kudoh M, Takahashi S, Shibuki K. Transcranial fluorescence imaging of auditory cortical plasticity regulated by acoustic environments in mice. Eur J Neurosci. 2006;23:1365–1376. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2006.04662.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas H, Tillein J, Heil P, Scheich H. Functional organization of auditory cortex in the mongolian gerbil (Meriones unguiculatus). I. Electrophysiological mapping of frequency representation and distinction of fields. Eur J Neurosci. 1993;5:882–897. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.1993.tb00940.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tian B, Rauschecker JP. Processing of frequency-modulated sounds in the cat’s anterior auditory field. J Neurophysiol. 1994;71:1959–1975. doi: 10.1152/jn.1994.71.5.1959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tucci DL, Cant NB, Durham D. Conductive hearing loss results in a decrease in central auditory system activity in the young gerbil. Laryngoscope. 1999;109:1359–1371. doi: 10.1097/00005537-199909000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tucci DL, Cant NB, Durham D. Conductive hearing loss results in changes in cytochrome oxidase activity in gerbil central auditory system. JARO. 2001;3:89–106. doi: 10.1007/s101620010091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vale C, Juiz J, Moore DR, Sanes DH. Unilateral cochlear ablation produces greater loss of inhibition in the contralateral inferior colliculus. Eur J Neurosci. 2004;20:2133–2140. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2004.03679.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallace MN, Roeda D, Harper MS. Deoxyglucose uptake in the ferret auditory cortex. Exp Brain Res. 1997;117:488–500. doi: 10.1007/s002210050245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallhäusser-Franke E, Braun S, Langner G. Salicylate alters 2-DG uptake in the auditory system: a model for tinnitus? Neuroreport. 1996;7:1585–1588. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199607080-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilmington D, Gray L, Jahrsdoerfer R. Binaural processing after corrected congenital unilateral conductive hearing loss. Hear Res. 1994;74:99–114. doi: 10.1016/0378-5955(94)90179-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Webster DB, Bobbin RP. Bilateral, asymmetrical effects of a unilateral conductive loss on cochlear functioning. Assoc Res Otolaryngol Abst. 1986:178. [Google Scholar]

- Weinberger NM. Auditory associative memory and representational plasticity in the primary auditory cortex. Hear Res. 2007;229:54–68. doi: 10.1016/j.heares.2007.01.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wetzel W, Ohl FW, Wagner H, Scheich H. Right auditory cortex lesion in Mongolian gerbils impairs discrimination of rising and falling frequency-modulated tones. Neurosci Lett. 1998;252:115–118. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(98)00561-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woolf NK, Sharp FR, Davidson TM, Ryan AF. Cochlear and middle ear effects on metabolism in the central auditory pathway during silence: a 2-deoxyglucose study. Brain Res. 1983;271:119–127. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(83)90526-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woolf NK, Ryan AF. The development of auditory function in the cochlea of the Mongolian gerbil. Hear Res. 1984;13:277–283. doi: 10.1016/0378-5955(84)90081-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woolf NK, Ryan AF. Ontogeny of neuronal discharge patterns in the ventral cochlear nucleus of the Mongolian gerbil. Brain Res. 1985;17:131–147. doi: 10.1016/0165-3806(85)90138-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu L, Jen PH-S. The effect of monaural middle ear destruction on postnatal development of auditory response properties of mouse inferior collicular neurons. Hear Res. 2001;159:1–3. doi: 10.1016/s0378-5955(01)00304-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu H, Kotak VC, Sanes DH. Conductive hearing loss disrupts synaptic and spike adaptation in developing auditory cortex. J Neurosci. 2007;27:9417–9426. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1992-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu Z-Y, Wang W, Fritschy J-M, Witte OW, Redecker C. Changes in neocortical and hippocampal GABAA receptor subunit distribution during brain maturation and aging. Brain Res. 2006;1099:73–81. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2006.04.118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zatorre RJ. There’s more to auditory cortex than meets the ear. Hear Res. 2007;229:24–30. doi: 10.1016/j.heares.2007.01.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]