Abstract

A convenient synthesis of a variety of substituted N-hydroxysulfamides from chlorosulfonyl isocyanate is reported. Alkyl groups can be introduced selectively on the N-Boc nitrogen of key intermediates 1a or 1b using the Mitsunobu reaction with alcohols. Subsequently the nitrogen carrying the silyloxy group can be alkylated under traditional conditions. Deprotection to the desired N-hydroxysulfamide can be achieved in high yields. Using this method, a number of structurally diverse N-hydroxysulfamides have been prepared. The usefulness of this methodology has further been demonstrated by the synthesis of more complex targets such as bis-hydroxysulfamide, 5, and cyclic hydroxysulfamides 7 and 8.

N-Hydroxysulfamides are a class of compounds that are structurally similar to N-hydroxyureasi, N-hydroxysulfonamidesii, and sulfamidesiii, which exhibit a wide range of biological activity. However, little research has focused on the synthesis of N-hydroxysulfamides or their biological activity. Recently, the synthesis of a few N-alkyl, N’-hydroxysulfamides was published.iv These compounds were shown to be potent inhibitors of several isozymes of carbonic anhydrase establishing the potential of N-hydroxysulfamides as pharmacophores.v Supuran et alvi have recently obtained the x-ray crystal structure of N-hydroxysulfamide (NH2SO2NHOH) with an isozyme of CA, which shows it is bound to the Zn through the ionized primary amino group. They propose that incorporation of R groups at the N-hydroxy position could lead to more effective enzyme inhibitors. Also, some phenylalanine-based N-hydroxysulfamides have been shown to be inhibitors of carboxypeptidase A.vii These results prompt us to report our own synthetic efforts to develop a convenient synthetic methodology for this class of molecules.

N-hydroxysulfamides have been prepared in low yields by the direct coupling of a sulfamoyl chlorideviii or fluorideix with hydroxylamine. This method is limited by poor availability of sulfamoyl chlorides and hydroxylamines. The first attempt to prepare some simple N- hydroxysulfamides from chlorosulfonylisocyanate (CSI) gave some surprising results. CSI was reacted with t-BuOH to give the N-Boc sulfamoylchloride, which was then reacted with O-benzylhydroxylamine. However, attempts to deprotect the N-benzyloxy group using hydrogenolysis resulted in cleavage of the N-O bond yielding the corresponding sulfamide and not the desired N-hydroxysulfamide.x In one example, direct coupling with unprotected hydroxylamine did lead to the unsubstituted N-hydroxysulfamide. More recently, a limited study was published that involved the coupling of O-(t-butyldimethylsilyl)-hydroxylamine with N-Boc sulfamoylchloride.4 Reaction of the resulting sulfamide with aliphatic alcohols under Mitsunobu conditions gave the corresponding N-alkyl-N’-hydroxysulfamides after deprotection with 5% water in TFA. However, this study was of limited synthetic scope and needed further expansion. We desired a method for the selective preparation of disubstituted N-hydroxysulfamides (including cyclic examples) and bis-N-hydroxysulfamides.

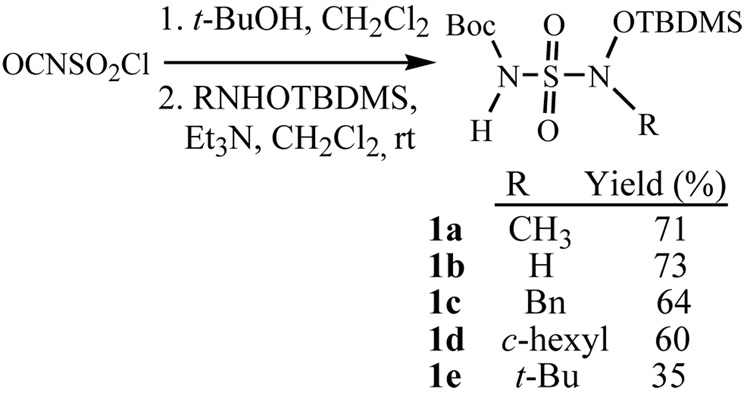

The known N-Boc-sulfamoyl chloride was prepared by the reaction of t-butanol with CSI and its reaction with several O-TBDMS protected hydroxylamines was investigated (Scheme 1). In general, a dichloromethane solution of the N-Boc sulfamoyl chloride (1 eq, prepared in situ) was added to a dichloromethane solution of O-TBDMS protected hydroxylamine (1–1.2 eq, prepared in situ) in the presence of triethylamine. After stirring the mixture overnight, the product was isolated and purified by flash chromatography. Using this procedure it was possible to prepare protected N-hydroxysulfamides, 1a–d, in good yields (Scheme 1).xi,xii However, the yield was lower in the coupling of the hindered t-butyl hydroxylamine to give 1e.

Scheme 1.

The protected sulfamides 1 provide an excellent starting material for preparation of derivatives by alkylation. We first examined the alkylation of the Boc protected nitrogen of 1a using Mitsunobu conditions (R¹OH, PPh3, DEAD - Method Axiii). The desired products were obtained in good yields after isolation and purification by silica gel chromatography. The Mitsunobu reaction proceeded smoothly with selectivity in the case of the unsubstituted sulfamide 1b, clearly demonstrating the nitrogen of higher nucleophilicity. The generality of this method is clearly shown by the examples listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Alkylation of sulfamides using Method A or B

| ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Entry | Substrate | Product | R | R¹ | Method | Yield (%) |

| 1 | 1a | 2a | CH3 | CH3CH2 | Aa | 74 |

| Bb | 75 | |||||

| 2 | 1a | 2b | CH3 | Bn | A | 77 |

| B | 74 | |||||

| 3 | 1a | 2c | CH3 | allyl | A | 66 |

| B | 77 | |||||

| 4 | 1a | 2d | CH3 | A | 74 | |

| 5 | 1a | 2e | CH3 | i-Pr | A | 73 |

| B | 29 | |||||

| 6 | 1b | 2f | H | CH3CH2 | A | 78 |

| B | mixturec | |||||

| 7 | 1b | 2g | H | Bn | A | 75 |

| B | mixtured | |||||

| 8 | 1b | 2h | H | allyl | A | 68 |

| 9 | 1b | 2i | H | i-Pr | A | 77 |

| 10 | 1b | 2j | nBu | nBu | Be | 79 |

| 11 | 1b | 2k | allyl | allyl | Be | 76 |

| 12 | 2g | 2l | nBu | Bn | B | 77 |

| 13 | 2i | 2m | Bn | i-Pr | B | 73 |

Method A-1, DEAD, PPh3, R¹OH, THF, rt.

Method B-1, R¹X (1.2 eq), K2CO3, CH3CN, reflux: X = I, except in 2b, 2c, 2k and 2g where X = Br

50:50 mixture of mono and dialkylated product (based on ¹H NMR)

40:60 mixture of mono and dialkylated product (based on ¹H NMR)

3 eq of RX.

Because of the time consuming and more difficult isolation of the products from the Mitsunobu reaction, we also examined the reactions of N-hydroxysulfamides 1 with alkyl halides using standard alkylation conditions (R¹X, K2CO3, CH3CN, reflux-method Bxiv). In the case of sulfamide 1a, N-alkylation using method B gave good yields of the desired products, 2a–d, (Table 1, entries 1–4) after isolation and purification by silica gel chromatography. Alkylation using the more hindered 2-iodopropane (Table 1, entry 5) gave a lower yield of the desired product 2e.

Alkylation of 1b (R = H) with 1 equivalent of ethyl iodide or benzyl bromide using method B, was more complex and gave mixtures of mono (alkylation at the Boc protected nitrogen) and dialkylated products (Table 1, entries 6 & 7). It was not possible to selectively effect this alkylation by variation of the reaction conditions. Though N-alkylation of the more acidic Boc protected nitrogen was the faster process, it was somewhat surprising that alkylation on the hydroxylamine nitrogen also occurred readily. This led us to take advantage of this observation and exploit it for the one pot preparation of symmetrical dialkylated sulfamides. For example 2j & 2k were prepared in good yields using method B with 3 equivalents of butyl iodide or allyl bromide.

Introduction of different alkyl groups on the two nitrogens of 1b was accomplished by a two-step procedure (Table 1, entries 12 & 13).xv In one example, the sulfamide 1b was first reacted with benzyl alcohol under Mitsunobu conditions (method A) to give the monoalkylated product 2g. Subsequent alkylation of 2g using butyl iodide (method B) gave the unsymmetrical dialkylated sulfamide 2l. The two-step approach clearly demonstrates the potential to incorporate the desired alkyl group at the appropriate nitrogen of 1b.

Representative sulfamides were deprotected to yield the corresponding N-hydroxysulfamides 3a–d (Table 2). The Boc group was first removed by treatment of the sulfamide with 10% trifluoroacetic acid in dichloromethane at room temperature. Subsequent removal of the TBDMS group was accomplished using 15% HCl in methanol.xvi

Table 2.

Preparation of N-hydroxysulfamides 3

| |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Entry | Substrate | Product | R | R¹ | Yielda (%) |

| 1 | 1c | 3a | Bn | H | 93 |

| 2 | 1d | 3b | c-hexyl | H | 90 |

| 3 | 2a | 3c | CH3 | CH3CH2 | 97 |

| 4 | 2d | 3d | CH3 | 85 | |

two-step yield

It is exciting to note that this methodology can be extended to prepare new classes of previously unreported N-hydroxysulfamide ligand systems. Treatment of α, α’-dibromo-m-xylene with two equivalents of sulfamide 1a in the presence of potassium carbonate in refluxing acetonitrile gave the protected sulfamide 4 in 79% yield after purification. Removal of the Boc protecting groups with 10% TFA in dichloromethane followed by treatment with 15% HCl in methanol gave the bis-N-hydroxysulfamide 5 in 78% yield (Scheme 2).

Scheme 2.

This methodology is also useful for the synthesis of cyclic N-hydroxysulfamides (Scheme 3). Alkylation of 1,3-dibromopropane with 1 equivalent of 1b in the presence of potassium carbonate in refluxing acetonitrile followed by removal of the Boc protecting group using 10% TFA in dichloromethane gave the cyclic sulfamide 6. Removal of the TBDMS protecting group using standard methods gave the cyclic N-hydroxysulfamide 7 in excellent yield. Alternatively, the sulfamide 6 could be alkylated with methyl iodide followed by removal of the TBDMS protecting group to give the cyclic N-methyl, N’-hydroxysulfamide 8. Cyclic sulfamides have been shown to inhibit a variety of enzymes.1b

Scheme 3.

In conclusion, we have developed a versatile synthetic method for the preparation of a wide array of N-hydroxysulfamides. Further, the methodology has been shown to be useful for the synthesis of bis-N-hydroxysulfamides as well as cyclic N-hydroxysulfamides. The present study increases the availability of diverse substrates for evaluation by researchers in the field of carbonic anhydrase inhibition, an area of much biomedical interest.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a grant from the National Institutes of Health under PHS Grant no. S06 GM08136.

Footnotes

Portions of this work were presented at the 229th American Chemical Society National Meeting, San Diego, CA, March 13–17, 2005. ORGN 525.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- i.a) Lori F, Kelly LM, Foli A, Lisziewicz J. Expert Opinion of Drug Safety. 2004;3(4):279. doi: 10.1517/14740338.3.4.279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Huang J, Zou Z, Kim-Shapiro DB, Ballas SK, King SB. J. Med. Chem. 2003;46:3748. doi: 10.1021/jm0301538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) King SB. Curr. Med. Chem. 2003;10:437. doi: 10.2174/0929867033368213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d) Granik VG, Grigor'ev NB. Russ. Chem. Bull. Int. Ed. 2002;51:1375. [Google Scholar]; e) Paz-Ares L, Donehower RC. In: Cancer Chemotherapy and Biotherapy-Principles and Practice, ch. 11. 3rd edn. Chabner BA, Longo DL, editors. Philadelphia: Lippincott, Williams, and Wilkins; 2001. pp. 315–328. [Google Scholar]; f) Frank I. J. Biol. Regulators and Homeostatic Agents. 1999;13(3):186. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; g) Charache S, Barton FB, Moore RD, Terrin ML, Steinberg MH, Dover GJ, Ballas SK, McMahon RP, Castro O, Orringer EP. Medicine. 1996;75:300. doi: 10.1097/00005792-199611000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ii.a) Nuti E, Orlandini E, Nencetti S, Rossello A, Innocenti A, Scozzafava A, Supuran CT. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2007;15:2298. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2007.01.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Wilkins PC, Jacobs HK, Johnson MD, Gopalan AS. Inorg. Chem. 2004;43(24):7877–7881. doi: 10.1021/ic049627z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Lee MJC, Shoeman DW, Goon DJW, Nagasawa HT. Nitric Oxide: Biology and Chemistry. 2001;5:278. doi: 10.1006/niox.2001.0349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d) Scozzafava A, Supuran CT. J. Med. Chem. 2000;43:3677. doi: 10.1021/jm000027t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e) Mincione F, Menabuoni L, Briganti F, Mincione G, Scozzafava A, Supuran CT. J. Enzyme Inhib. 1998;13:267. doi: 10.3109/14756369809021475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- iii.a) Winum J-Y, Scozzafava A, Montero J-L, Supuran CT. Med. Res. Rev. 2006;26:767. doi: 10.1002/med.20068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Winum J-Y, Scozzafava A, Montero J-L, Supuran CT. Expert Opinion on Therapeutic Patents. 2006;16(1):27. doi: 10.1517/13543776.16.1.27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Casini A, Winum J-Y, Montero J-L, Scozzafava A, Supuran CT. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2003;13:837. doi: 10.1016/s0960-894x(03)00028-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d) Park JD, Kim DH, Kim S-J, Woo J-R, Ryu SE. J. Med. Chem. 2002;45:5295. doi: 10.1021/jm020258v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e) Tozer MJ, Buck IM, Cooke T, Kalindjian SB, McDonald JM, Pether MJ, Steel KIM. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 1999;9:3103. doi: 10.1016/s0960-894x(99)00535-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- iv.Winum J-Y, Innocenti A, Nasr J, Montero J-L, Scozzafava A, Vullo D, Supuran CT. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2005;15:2353. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2005.02.091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- v.For some recent reviews on design of carbonic anhydrase inhibitors see: Winum J-Y, Scozzafava A, Montero J-L, Supuran CT. Curr. Topics Med. Chem. 2007;7:835. doi: 10.2174/156802607780636771.Supuran CT, Vullo D, Manole G, Casini A, Scozzafava A. Curr. Med. Chem. Cardiovascular and Hematological Agents. 2004;2:49.Supuran CT, Scozzafava A, Casini A. Med. Res. Rev. 2003;23:146. doi: 10.1002/med.10025.

- vi.Temperini C, Winum J-Y, Montero J-L, Scozzafava A, Supuran CT. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2007;17:2795. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2007.02.068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- vii.Park JD, Kim DH. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2004;12:2349. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2004.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- viii.Oettle J, Brink K, Morawietz G, Backhaus M, Boldhaus M, Bliefert CZ. Naturforsch. 1978;33b:1193. [Google Scholar]

- ix.Boldhaus M, Brink K, Bliefert C. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 1980;19(11):943. [Google Scholar]

- x.Hajri A-H, Dewynter G, Criton M, Dilda P, Montero J-L. Heteroatom Chemistry. 2001;12(1):1. [Google Scholar]

- xi.Spectroscopic (¹H, 13C, and IR) and elemental analyses of all compounds are in agreement with the assigned structures.

- xii.Representative procedure for the preparation of sulfamides 1. Preparation of N-(tert-butoxycarbonyl)-N’-methyl-N’-[(tert-butyldimethyl)silyloxy]-sulfamide (1a): Triethylamine (2.5 mL, 17.9 mmol) was added dropwise to a suspension of N-methylhydroxylamine hydrochloride (0.50 g, 6.0 mmol) in anhydrous CH2Cl2 (10 mL) under N2 at 0°C and stirred at rt for 2 h. The reaction mixture was cooled to 0°C and a solution of TBDMSCl (0.90 g, 6.0 mmol) in anhydrous CH2Cl2 (5 mL) was slowly added at 0°C. The reaction mixture was then stirred at rt for 20 h. In a separate flask, t-butanol (0.57 mL, 6.0 mmol) was added dropwise to a solution of chlorosulfonylisocyanate (0.51 mL, 6.0 mmol) in anhydrous CH2Cl2 (15 mL) under N2 at 0°C and stirred at 0°C for 40 min to give the t-butoxycarbamoylsulfamoyl chloride. Triethylamine (2.5 mL, 17.9 mmol) was added to the solution of protected hydroxylamine at 0°C. The solution containing the sulfamoyl chloride was added to the protected hydroxylamine via syringe. The reaction mixture was warmed to rt and stirred for 18 h. The solvent was removed under reduced pressure. The residue was dissolved in EtOAc (100 mL) and washed with water (10 mL), 0.1 M HCl (3 × 10 mL), satd NaHCO3 (3 × 10 mL), brine (15 mL) and dried (Na2SO4). The crude product was purified by flash silica gel chromatography to give 1a (1.44 g, 71%) as a white solid. ¹H NMR (CDCl3, 200 MHz) δ 0.22(s, 6H), 0.94(s, 9H), 1.51(s, 9H), 3.09(s, 3H,) 6.99 (br s, 1H); 13C NMR (CDCl3, 50 MHz) δ −5.1, 17.7, 25.7, 27.8, 42.8, 84.0, 149.1; IR (KBr) 3192, 2990, 2932, 2859, 1713 cm−1; Anal calcd for C12H28O5N2SSi: C, 42.33; H, 8.29; N, 8.23. Found: C, 42.09; H, 7.98; N, 8.34.

- xiii.Method A-Representative procedure: Preparation of N-[tert-butoxycarbonyl]-N-(ethyl)-N’-(methyl)-N’-[(tert-butyldimethyl)silyloxy]-sulfamide (2a): To a solution of 1a (0.350 g, 1.03 mmol) and DEAD (40% in toluene, 0.448 mL, 1.03 mmol) in anhydrous THF (5 mL) under N2, was added a solution of PPh3 (0.269 g, 1.03 mmol) and EtOH (0.060 g, 1.24 mmol) in anhydrous THF (3 mL) and the reaction mixture was stirred at rt for 16 h. The solvent was removed under reduced pressure and the crude product was purified by flash silica gel chromatography to give 2a (0.281 g, 74%). ¹H NMR (CDCl3, 200 MHz) δ 0.22(s, 6H), 0.93(s, 9H), 1.30(t, 3H), 1.52(s, 9H), 3.08(s, 3H), 3.75(q, 2H); 13C NMR (CDCl3, 50 MHz) δ −5.2, 15.0, 17.7, 25.7, 27.9, 43.0, 46.07, 83.8, 151.0; IR (Neat) 2935, 2860, 1724 cm−1; Anal calcd for C14H32O5N2SSi: C, 45.62; H, 8.75; N, 7.60. Found: C, 45.91; H, 8.40; N, 7.41.

- xiv.Method B: Representative procedure for 2a: To a solution of 1a (0.150 g, 0.44 mmol) in anhydrous CH3CN (5 mL) was added anhydrous K2CO3 (0.073 g, 0.53 mmol) and CH3CH2I (0.082 g, 0.53 mmol) and the reaction mixture was heated at reflux for 4 h. The solvent was removed under reduced pressure. The residue was dissolved in EtOAc (25 mL) and washed with water (3 × 10 mL), brine (10 mL) and dried (Na2SO4). The crude product was purified by flash silica gel chromatography to give 2a (0.122g, 75%).

- xv.For sequential alkylation on N-Boc protected sulfamides see: Montero J-L, Dewynter G-F, Agoh B, Delaunay B, Imbach J-L. Tetrahedron Lett. 1983;24:3091.Regainia Z, Abdaoui M, Aouf N, Dewynter G, Montero J-L. Tetrahedron. 2000;56:381.

- xvi.General procedure for deprotection of sulfamides: Preparation of N-(ethyl)-N’-(methyl)-N’-(hydroxy)sulfamide (3c): To a solution of 2a (0.29 g, 0.79 mmol) in anhydrous CH2Cl2 (10 mL) was added trifluoroacetic acid (0.9 mL, 3.60 mmol) at rt and the reaction mixture was stirred for 1.5 h. The solvent was removed under reduced pressure to give the Boc deprotected compound (0.21 g, 99%) which was used without purification. ¹H NMR (CDCl3, 200 MHz) δ 0.22(s, 6H), 0.93(s, 9H), 1.24(t, 3H), 2.93(s, 3H), 3.30–3.40(m, 2H), 4.26(br s, 1H). The Boc deprotected compound (0.177 g) was stirred with 15% HCl in methanol (3 mL) at rt. After 3 h, the solvent was removed under reduced pressure. The residue was washed with hexane and dried under vacuum to give N-hydroxysulfamide 3c as a pale yellow oil (0.099 g, 97% two steps). ¹H NMR (CDCl3, 200 MHz) δ 1.25(t, 3H), 3.02(s, 3H), 3.25–3.40(m, 2H), 4.66(br s, 1H), 6.26(br s, 1H); 13C NMR (CDCl3, 50 MHz) δ 15.7, 39.8, 40.4; IR (neat) 3313, 2984, 1435 cm−1; Anal calcd for C3H10O3N2S: C, 23.37; H, 6.54; N, 18.17. Found: C, 23.70; H, 6.93; N, 17.78.