Abstract

Objective:

To examine the effects of creatine supplementation on the incidence of cramping and injury observed during 1 season of National Collegiate Athletic Association Division IA football training and competition.

Design and Setting:

In an open-label manner, subjects who volunteered to take creatine ingested 0.3 g·kg−1·d−1 of creatine for 5 days followed by an average of 0.03 g·kg·−1d−1 after workouts, practices, and games. Creatine intake was monitored and recorded by researchers throughout the course of the study.

Subjects:

Thirty-eight of 72 athletes (53.0%) participating in the 1999 Division IA collegiate football season from the same university volunteered to take creatine in this study. Subjects trained, practiced, or played in environmental conditions ranging from 15°C to 37°C (mean = 27.26° ± 10.93°C) and 46.0% to 91.0% relative humidity (mean = 54.17% ± 9.71%).

Measurements:

Injuries treated by the athletic training staff were recorded and categorized as cramping, heat illness or dehydration, muscle tightness, muscle strains, noncontact joint injuries, contact injuries, and illness. The number of missed practices due to injury and illness was also recorded. Data were analyzed using a 2 × 2 χ2 test to examine the first reported incidences of cramping and injury for creatine users and nonusers.

Results:

Creatine users had significantly less cramping (χ21 = 5.35 P = .021); heat illness or dehydration (χ21 = 4.09, P = .043); muscle tightness (χ21 = 5.39, P = .020); muscle strains (χ21 = 5.36, P = .021); and total injuries (χ21 = 17.80, P<.001) than nonusers. There were no significant differences between groups regarding noncontact joint injuries (χ21= 3.48, P = .062); contact injuries (χ21 = 0.00, P = .100); illness (χ21 = 6.82, P = .409); missed practices due to injury (χ21 = 1.43, P = .233); or players lost for the season (χ21 = 4.75, P = .491).

Conclusions:

The incidence of cramping or injury in Division IA football players was significantly lower or proportional for creatine users compared with nonusers.

Keywords: exercise, nutrition, ergogenic aids, safety, sport injuries

Creatine supplementation has been reported to increase strength,1 enhance work performed during repetitive sets of muscle contractions,2 improve repetitive sprint performance,1 and increase body mass/fat-free mass.1–3 Consequently, creatine has become a very popular nutritional supplement among athletes. The only documented side effect from creatine supplementation reported in the scientific and medical literature has been weight gain.1–4 However, concerns have been raised over the safety of creatine supplementation among select populations, although extensive research has yielded no negative effects in the areas of endogenous creatine synthesis,5 renal and liver function,6–9 muscle and liver enzyme efflux,6,9 blood volume10,11 and electrolyte status,11,12 blood pressure,13 or general markers.3,6,7,9,13–15 Additionally, only anecdotal reports have suggested that creatine supplementation during intense training in hot or humid environments may predispose athletes to increased incidence of muscle cramping, dehydration, or musculoskeletal injuries such as muscle strains, or a combination of these.16–18 Therefore, our purpose was to examine the effects of creatine supplementation on the incidence of dehydration and cramping and various musculoskeletal injuries observed in National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA) Division IA football players during training and competition. This study was only conducted through the course of 1 season due to the August 2000 NCAA restrictions regarding the provision of “muscle-building” supplements (ie, creatine) to athletes.

METHODS AND MATERIALS

Subjects

We monitored injury rates of 72 Division IA NCAA collegiate football players at a Southern university during the 1999 football season. Subjects who volunteered to participate in this study chose whether they wanted to take creatine- or non-creatine–containing supplements (placebo) during training and competition. No subject reported taking additional ergogenic supplements other than protein-carbohydrate shakes or protein bars. All subjects underwent preseason medical examinations and were cleared to participate in football according to NCAA guidelines. In addition, all athletes were provided medical supervision by the team athletic training staff and physicians throughout the observation period. Subjects were properly informed as to the experimental procedures, and informed consent statements were signed in adherence with the guidelines of the university's internal review board for use of human subjects, which also approved the study. Subjects were 19.7 ± 1.0 years of age (range, 18–24 years) and 183.0 ± 9.0 cm tall (range, 159–202 cm) with mass of 105.0 ± 18.0 kg (range, 72–140 kg) upon reporting to fall football camp for the 1999 season.

Procedures

Injuries treated by the athletic training staff during the 1999 college football season were monitored during this study. We accomplished this by attending training sessions, practice sessions, and games and by recording all injuries treated by the athletic training staff. To ensure that the injury was accurately recorded, we confirmed the type, category, and degree of injury with the athletic training staff when the injury occurred. Additionally, missed practices were tabulated to monitor the length of time an athlete was unable to participate due to specific injury. We also recorded any “perceived” negative side effects associated with creatine supplementation reported daily by the athletes. Injuries were categorized as cramping; heat disorders (eg, dehydration, heat syncope); muscle tightness; muscle strains; noncontact joint injuries; contact injuries; illness; and the number of missed practices due to injury. These injuries were considered significant injuries because they required medical attention during or after training sessions, practices, or games, and they involved limitation from participation in the sport. Minor injuries that did not limit the athlete's ability to participate in practices and games or require significant medical treatment were not recorded.

Supplementation Protocols

Subjects who volunteered for the study chose whether they wanted to take creatine, and the remaining subjects had access to a non-creatine–containing commercial sport drink, which was designated as the placebo. Creatine was added to sports drinks or water that the players ingested under the supervision of research assistants after training sessions, practices, and competition during the 4-month period. Subjects also turned in weekly logs to verify their compliance to the prescribed creatine-dosage protocol. The 38 subjects who chose to take creatine ingested, in an open-label manner, creatine monohydrate (0.3 g/kg loading phase) for 5 days and 0.03 g/kg per day thereafter (115-day maintenance phase) based on a formula known to increase creatine concentrations in relation to the athlete's body mass.19 Further, these specific creatine-dosage protocols were selected based on previous research recommendations.19 If a subject fell behind in taking creatine, he ingested double the maintenance dose the following day in order to catch up (n = 4 subjects on 2 occasions).

Training

Training consisted of resistance training and conditioning drills (1–2 h/d, 4 d/wk); fall football camp (3–6 h/d, 6-d/wk); and practicing and competition during football season (2–4 h/d, 6 d/wk). Athletic coaches, certified athletic trainers, and research assistants supervised all training sessions. Training averaged 127 ± 65 minutes per session with an average intensity of 3.5 ± 1 on a 1 to 5 scale, where 1 was equivalent to a walk-through practice before games and 5 was equivalent to game competition. Environmental conditions during training and competition ranged from 15°C to 37°C (mean = 27.26°C ± 10.93°C) and 46.0% to 91.0% relative humidity (mean = 54.17% ± 9.71%).

Data Analyses

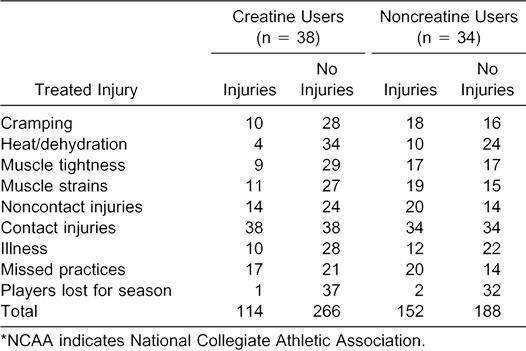

The incidence of reported first-time injuries observed in creatine users and noncreatine users for each category was monitored and recorded during the study (Table). Injuries treated by the athletic training staff were documented and categorized as cramping, heat illness or dehydration, muscle tightness, muscle strains, noncontact joint injuries, contact injuries, and illness. The number of missed practices due to injury or illness and the total injuries were also recorded. Data were analyzed using a 2 × 2 χ2 test to examine the incidence of reported first-time cramping and injury occurrences for creatine users and nonusers (P < .05).

First-Time Injuries, Illnesses, Missed Practices, and Players Lost for the Season Among Creatine-Supplemented and Nonsupplemented NCAA Division IA College Football Players*

RESULTS

Only first-time injuries were included in the χ2 procedure in order to adhere to the nonparametric statistical assumption of mutual exclusiveness, although select athletes were treated for different, multiple, and recurring injuries throughout the study. If an athlete aggravated a previous injury (ie, sprained ankle) that occurred before the season, it was not recorded for the purposes of this study. Creatine users had significantly less cramping (χ21 = 5.35, P < .021); heat illness or dehydration (χ21 = 4.09, P = .043); muscle tightness (χ21 = 5.39, P = .020); muscle strains (χ21 = 5.36, P = .021); and total injuries (χ21 = 17.80, P < .001) than nonusers. No significant differences were noted between groups regarding noncontact joint injuries (χ21 = 3.48, P = .062); contact injuries (χ21 = 0.00, P = .100); illness (χ21 = 6.82, P = .409); missed practices due to injury (χ21 = 1.43, P = .233); and players lost for the season (χ21 = 4.75, P = .491).

DISCUSSION

Anecdotal reports have suggested that creatine supplementation may promote dehydration, cramping, and musculoskeletal injury.4,20 Because many of these reports have emanated from certified athletic trainers and coaches, these conditions are commonly described as side effects from creatine supplementation.4,20 As a result, some certified athletic trainers and coaches have restricted the availability of creatine to their athletes (particularly during intense training periods performed in the heat), and some have warned against the use of creatine until more long-term data demonstrate its safety. In addition, some athletic organizations (eg, NCAA) have banned the practice of allowing teams to “provide” creatine to their athletes, citing safety and fairness issues, although athletes are still allowed to take creatine. We found that creatine use among Division IA football players training and competing in hot and humid environments did not significantly promote dehydration, cramping, or muscle injury in comparison with athletes who did not take creatine. Moreover, the athletes did not report a consistent pattern of “perceived” negative side effects as a result of the creatine-supplementation protocol. Within the scope of this study, these findings add to the growing body of evidence that creatine supplementation does not cause the anecdotally reported side effects and, to date, does not appear to cause health problems.6–9,14,15

Among the most commonly reported anecdotal side effects associated with creatine supplementation have been an increased incidence of dehydration or muscle cramping and decreased heat tolerance. In this regard, some have suggested that since creatine supplementation may increase work capacity, athletes who take creatine during training in hot and humid environments may experience a greater rate of dehydration, muscle cramping, or heat illness (or all 3).21 It also has been suggested that creatine ingestion promotes fluid retention, which may alter electrolyte status and promote muscle cramping by interfering with the muscle's contraction-relaxation mechanisms.4,21 Over the last few years, a number of researchers11,21 have examined the effects of creatine supplementation on hydration status, electrolyte levels, and dehydration during exercise performed in the heat and found that creatine does not promote dehydration, alter electrolyte levels, or increase thermal stress. In addition, there has been no evidence that creatine supplementation promotes muscle cramping among athletes.11,16,22 In fact, recent findings indicated that creatine supplementation may actually promote hydration,11,23 reduce thermal stress during exercise in the heat,11,22 and possibly reduce the incidence of injury.15,16,22 Our results suggest that the incidence of cramping and dehydration observed among creatine users was significantly lower than among nonusers.

Anecdotal reports have also suggested that creatine may promote a higher incidence of muscle injuries, such as muscle strains.4,17 Proponents of this theory postulated that because creatine supplementation may promote rapid increases in strength and body mass, the athlete may be more predisposed to additional stress placed on muscles, bones, joints, ligaments, and connective tissues. In our investigation, the incidence of muscle tightness, muscle strains, and total injuries was significantly lower among creatine users than among nonusers. There was also no evidence of a significant difference between creatine users and nonusers regarding the incidence of illness, missed practices, and players lost with a season-ending injury. If creatine supplementation increased the incidence of these problems, the incidence of injury among creatine users should have been markedly higher than among nonusers. However, the incidence of injury among athletes who took creatine during training was similar to or lower than that of athletes not taking creatine. It might be argued that creatine supplementation appeared to allow the athletes to tolerate training to a greater degree and, thereby, lessened the incidence of injury. These findings are similar to recent reports that creatine supplementation during training may lessen injury rates among athletes15,16,22 or hasten recovery after immobilization injury.24 Specifically, in a closely related study,22 investigators examined the effects of creatine supplementation on cramping and injury occurrence in 100 Division IA football players over a 3-year period. The incidence of cramping, dehydration, muscle tightness, muscle strains, noncontact injuries, and contact injuries among creatine users was similar to or lower than among nonusers. There was also no evidence of a greater proportion of individual injuries (eg, hamstring strains, groin strains, etc). Moreover, the incidences of illness, missed practices, and total injuries and the 1 player lost with a season-ending injury among the creatine users were similar to or lower than among the nonusers. The results of this 3-year investigation are closely related to the findings in our study.

In summary, our preliminary analysis suggests that collegiate football players who took creatine during training and competition did not experience a greater incidence of dehydration, cramping, or injury in comparison with collegiate football players not taking creatine. Although athletes who take creatine during intense training may experience some of these problems, the incidence of these problems was similar to or lower than among athletes not taking creatine in this study. Therefore, our findings may help to dispel anecdotal myths suggesting that creatine supplementation may increase the incidence of dehydration, cramping, or injury among athletes. In addition, we hope that these findings may help professionals involved in the training and medical supervision of athletes (ie, athletic coaches, certified athletic trainers, researchers, certified strength and conditioning coaches, nutritional consultants, administrators, athletic governing bodies) to better examine the methods employed to train and manage athletes (ie, 3-a-day training in extreme climates, exhaustive conditioning drills, hydration practices, etc). In this regard, it appears that the type of activities and conditions in which athletes are asked to train and compete may place them at a greater risk of dehydration, cramping, or injury than creatine supplementation.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank the athletes who participated in this study and the coaches who allowed us to conduct this research. A special thank you goes to the athletic training staff for their involvement in this investigation. The investigators independently collected, analyzed, and interpreted data from this study and have no commercial, proprietary, or financial interest in the outcome of results reported. Presentation of the results in this study does not constitute endorsement by the authors or their institutions of the supplement investigated.

REFERENCES

- 1.Noonan D, Berg K, Latin RW, Wagner JC, Reimers K. Effects of varying dosages of oral creatine relative to fat free body mass on strength and body composition. J Strength Cond Res. 1998;12:104–108. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Earnest CP, Snell PG, Rodriguez R, Almada AL, Mitchell TL. The effect of creatine monohydrate ingestion on anaerobic power indices, muscular strength and body composition. Acta Physiol Scand. 1995;153:207–209. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-1716.1995.tb09854.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Peeters BM, Lantz CD, Mayhew JL. Effect of oral creatine monohydrate and creatine phosphate supplementation on maximal strength indices, body composition, and blood pressure. J Strength Cond Res. 1999;13:3–9. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Terjung RL, Clarkson P, Eichner ER, et al. American College of Sports Medicine roundtable: the physiological and health effects of oral creatine supplementation. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2000;32:706–717. doi: 10.1097/00005768-200003000-00024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vandenberghe K, Goris M, Van Hecke P, Van Leemputte M, Vangerven L, Hespel P. Long-term creatine intake is beneficial to muscle performance during resistance training. J Appl Physiol. 1997;83:2055–2063. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1997.83.6.2055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Robinson TM, Sewell DA, Casey A, Steenge G, Greenhaff PL. Dietary creatine supplementation does not affect some haematological indices, or indices of muscle damage and hepatic and renal function. Br J Sports Med. 2000;34:284–288. doi: 10.1136/bjsm.34.4.284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Poortmans JR, Francaux M. Long-term oral creatine supplementation does not impair renal function in healthy athletes. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1999;31:1108–1110. doi: 10.1097/00005768-199908000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Poortmans JR, Auquier H, Renaut V, Durussel A, Saugy M, Brisson GR. Effect of short-term creatine supplementation on renal responses in men. Eur J Appl Physiol Occup Physiol. 1997;76:566–567. doi: 10.1007/s004210050291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schilling BK, Stone MH, Utter A, et al. Creatine supplementation and health variables: a retrospective study. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2001;33:183–188. doi: 10.1097/00005768-200102000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Oopik V, Paasuke M, Timpmann S, Medijainen L, Ereline J, Smirnova T. Effect of creatine supplementation during rapid body mass reduction on metabolism and isokinetic muscle performance capacity. Eur J Appl Physiol Occup Physiol. 1998;78:83–92. doi: 10.1007/s004210050391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Volek JS, Mazzetti SA, Farquhar WB, Barnes BR, Gomez AL, Kraemer WJ. Physiological responses to short-term exercise in the heat after creatine loading. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2001;33:1101–1108. doi: 10.1097/00005768-200107000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kreider RB, Ferreira M, Wilson M, et al. Effects of creatine supplementation on body composition, strength, and sprint performance. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1998;30:73–82. doi: 10.1097/00005768-199801000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mihic S, MacDonald JR, McKenzie S, Tarnopolsky MA. Acute creatine loading increases fat-free mass, but does not affect blood pressure, plasma creatinine, or CK activity in men and women. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2000;32:291–296. doi: 10.1097/00005768-200002000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stone MH, Schilling BK, Fry AC, et al. A retrospective study of long-term creatine supplementation on blood markers of health. J Strength Cond Res. 1999;13:434–436. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kreider RB, Melton C, Rasmussen CJ, et al. Long-term creatine supplementation does not significantly affect clinical markers of health in athletes. Mol Cell Biochem. 2003;244:95–104. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Greenwood M, Farris J, Kreider R, Greenwood L, Byars A. Creatine supplementation patterns and perceived effects in select Division I collegiate athletes. Clin J Sport Med. 2000;10:191–194. doi: 10.1097/00042752-200007000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Juhn MS, O'Kane JW, Vinci DM. Oral creatine supplementation in male collegiate athletes: a survey of dosing habits and side effects. J Am Diet Assoc. 1999;99:593–595. doi: 10.1016/s0002-8223(99)00145-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.LaBotz M, Smith BW. Creatine supplement use in an NCAA Division I athletic program. Clin J Sport Med. 1999;9:167–169. doi: 10.1097/00042752-199907000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hultman E, Soderland K, Timmons JA, Cederblad G, Greenhaff PL. Muscle creatine loading in men. J Appl Physiol. 1996;81:232–237. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1996.81.1.232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Juhn MS, Tarnopolsky M. Potential side effects of oral creatine supplementation: a critical review. Clin J Sport Med. 1998;8:298–304. doi: 10.1097/00042752-199810000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kern M, Podewils LJ, Vukovich M, Buono MJ. Physiological response to exercise in the heat following creatine supplementation. J Exerc Physiol. 2001;4:18–27. Available at: http://www.css.edu/users/tboone2/asep/Kern.pdf. Accessed November 27, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Greenwood M, Kreider RB, Melton C, et al. Creatine supplementation during college football training does not increase the incidence of cramping or injury. Mol Cell Biochem. 2003;244:83–88. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ziegenfuss TN, Lowery LM, Lemon PWR. Acute fluid volume changes in men during three days of creatine supplementation. J Exerc Physiol. 1998;1:1–9. Available at: http://www.css.edu/users/tboone2/asep/jan3.htm. Accessed November 27, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hespel P, Op't Eijnde B, Van Leemputte M, et al. Oral creatine supplementation facilitates the rehabilitation of disuse atrophy and alters the expression of muscle myogenic factors in humans. J Physiol. 2001;536:625–633. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2001.0625c.xd. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]