Abstract

A novel culture system for mammalian cells was used to investigate division orientations in populations of Chinese hamster ovary cells and the influence of gravity on the positioning of division axes. The cells were tethered to adhesive sites, smaller in diameter than a newborn cell, distributed over a nonadhesive substrate positioned vertically. The cells grew and divided while attached to the sites, and the angles and directions of elongation during anaphase, projected in the vertical plane, were found to be random with respect to gravity. However, consecutive divisions of individual cells were generally along the same axis or at 90° to the previous division, with equal probability. Thus, successive divisions were restricted to orthogonal planes, but the choice of plane appeared to be random, unlike the ordered sequence of cleavage orientations seen during early embryo development.

Consecutive division planes in animal cells are commonly observed to be oriented at 90° to each other (1). In the case of developing embryos, the earliest cleavages are oriented in a specific orthogonal sequence, e.g., two divisions in vertical planes at 90° to each other and a third in the horizontal plane (2–4). In some instances, the cleavage orientations are gravity sensitive (5, 6). There are, however, exceptions to the rule of consecutive orthogonal division planes in some developmental systems, in polarized tissues, and in budding yeast, where successive divisions may take place along the same axis (7–12). This study was designed to investigate the orientations of division planes in mammalian cells growing autonomously in vitro and the influence of gravity on these orientations.

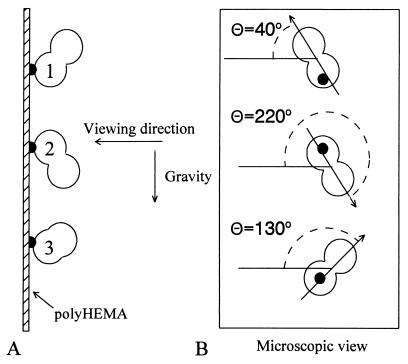

To undertake this study it was considered important to grow the cells in a manner that would mimic autonomous growth in suspension culture as nearly as possible, and at the same time maintain the cells fixed in place so that division angles could be measured. To achieve this, the “baby machine” culture technique was exploited, which has been used to study cell cycle properties of prokaryotic cells for many years and has recently been applied to eukaryotes (13–15). In this technique, the cells grow and divide while attached to tiny adhesive sites distributed over a nonadhesive surface (shown schematically in Fig. 1). The sites are smaller than the diameter of a newborn cell so that each time a cell divides there is usually room for only one new daughter cell to remain attached and the other is released. Thus, the cells remain spherically shaped, similar to those in suspension culture, but immobilized. To evaluate the effects of gravity on division orientations, the surface was held vertically, as shown in Fig. 1A. The orientation of division was determined by measuring the angle of the long axis of the dividing cell, termed the division axis, which would also correspond to the spindle axis, drawn as a vector in the direction of elongation of the cell in anaphase in the vertical plane (Fig. 1B). Cells 1 and 2 in Fig. 1A are shown dividing at right angles to each other in perpendicular division planes. When viewed (Fig. 1B), the division axes are parallel, but the division directions are at 180°. Cell 3 is shown dividing on an axis at 90° to the other two cells.

Figure 1.

Illustration of the culture technique. (A) Three cells are shown dividing while attached to small adhesive sites fixed to a nonadhesive substrate. The division axes of cells 1 and 2 are perpendicular to each other in parallel planes. The division axis of cell 3 is in a plane perpendicular to the axes of cells 1 and 2. (B) Appearance of the three cells when viewed in the vertical plane of the substrate. Because the axes of division of cells 1 and 2 were in parallel planes, they divide along parallel axes but in opposite directions with the angles indicated. Cell 3 divides at an angle perpendicular to cells 1 and 2.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Preparation of Culture Flasks.

To produce the nonadherent surface, the bottom of a 25-ml polystyrene culture flask was coated with a 5% solution of poly-2-hydroxyethyl methacrylate (polyHEMA, Sigma) in absolute methanol (15). Prior to coating, the flasks were rinsed twice with approximately 10-ml volumes of methanol, and then 0.5 ml of the polyHEMA was pipetted into the flask to cover the bottom. The coated flasks were dried in a sterile hood overnight with the caps off. The adhesive sites consisted of 4.8 μm-diameter Dynabeads (Dynal, Great Neck, NY). The Dynabeads, generally the tosyl-activated version, were resuspended in 5–10 ml of PBS to a total of approximately 106 beads per sample. After vortexing the suspension, it was poured into a polyHEMA-coated flask, and the beads were allowed to settle onto the coating for 6 hr or longer at room temperature. After the beads had settled and adhered to the polyHEMA, the flask was rinsed once with PBS in preparation for addition of the cells. Chinese hamster ovary cells (CHO-K1, ATCC CCL 61) were added to the flask from a stock grown to confluence in RPMI medium 1640 (GIBCO) with 10% fetal bovine serum in a 25-ml culture flask. Before addition of the cells to the polyHEMA-coated flask, 3 ml of RPMI medium 1640 plus 4 ml fetal bovine serum were added to the flask followed by approximately one-half of the stock flask, in 5 ml RPMI medium 1640, which had been dissociated with trypsin–EDTA. The flask was gassed with 5% CO2/95% air and incubated approximately 18 hr at 37°C. The cells attached only to the beads, and by the end of the incubation most of the beads contained an attached cell. The flask was then rocked to resuspend unattached cells and cell clumps, the suspension was poured off, and 20 ml of fresh RPMI medium 1640 with 20% serum was added and the flasks gassed with 5% CO2/95% air.

Measurement of Division Axes.

The growth and division of the cells attached to the adhesive beads were monitored with an Olympus IMT-2 inverted microscope and a Hitachi VK-C150 color video camera connected to an Hitachi TLC1550 time-lapse VCR. The microscope contained a chamber maintained at 37°C, and was positioned so that the stage, and consequently the culture flask, was in a vertical plane. The video recordings were used to observe the growth properties of the cells, and division angles were measured for each cell as the direction of the spindle axis at late anaphase, directly on the screen of the monitor or from photographs of individual frames of the video tapes.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

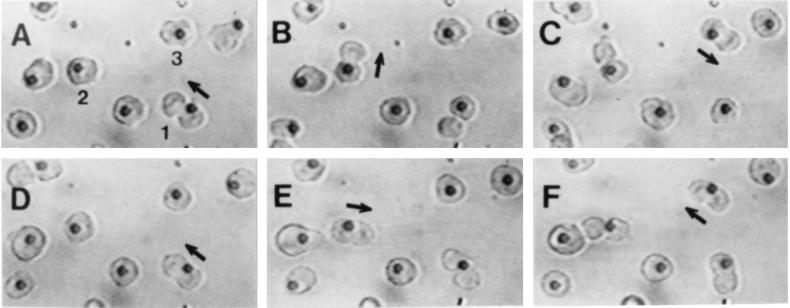

Fig. 2 shows a representative sequence of photographs from a time-lapse videotape of a field of CHO cells growing attached to 4.8-μm diameter beads distributed over a nonadhesive coating of polyHEMA in a culture flask. Three cells are shown dividing twice in the directions indicated. Cell 1 divided in the same direction in the vertical plane in two consecutive divisions (Fig. 2 A and D). Cell 2 divided on 90° axes in the two divisions (Fig. 2 B and E). Cell 3 divided along the same axis in the two divisions but in opposite directions (Fig. 2 C and F).

Figure 2.

CHO cells growing and dividing on adhesive beads. Photographs are taken from a video tape of the same field over a 14-hr period. The directions of division of three cells during two successive divisions are shown, each at late anaphase. Cell 1 divides in the same direction along the same axes in two successive divisions (A and D), cell 2 divides at right angles in successive divisions (B and E), and cell 3 divides in opposite directions on the same axis (C and F). Note that the daughter cell not attached to the adhesive bead falls off after a division is completed (see text). Measured angles between the two consecutive division axes of these three cells were 2°, 95°, and 189°, respectively.

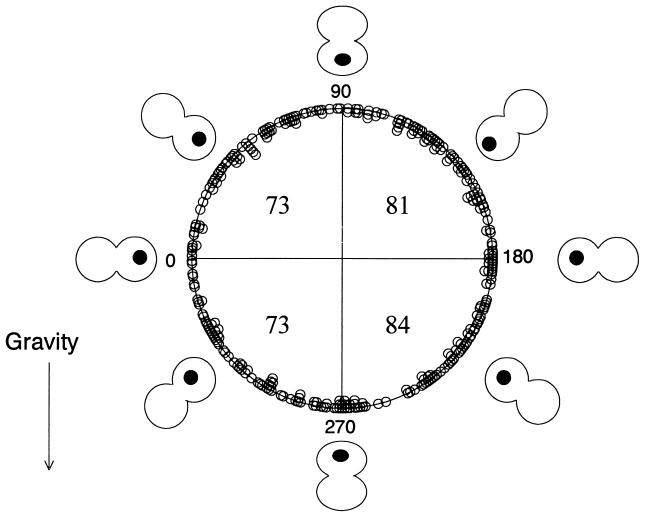

Division angles were measured for 311 cells observed in 6 separate experiments (Fig. 3). The angles of division in the vertical plane could be measured except in the instances when the cell elongated directly out from the vertical plane. The cultures were observed for about 5 days each, or until they were overgrown. It is evident that the direction of division was random with respect to the vertical plane.

Figure 3.

Angles of division axes for cells held in a vertical plane. Angles of the division vectors for 311 cells are shown in the polar diagram, with an angle of zero to the left. Total number of cells in each quadrant is indicated within the circle.

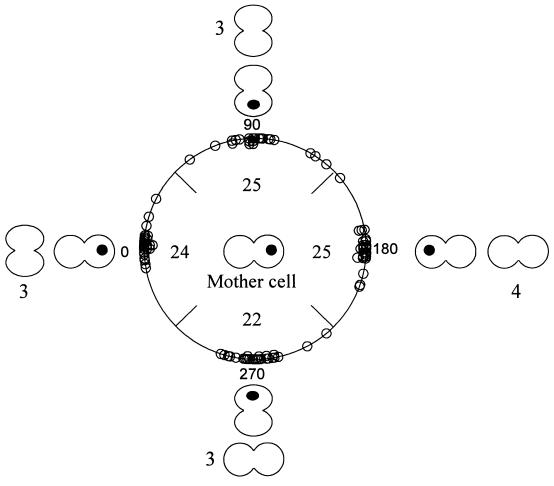

Many of the cells divided two or more times during observation, so that angles of successive divisions for an individual cell attached to a bead could also be determined. The results of this analysis for 96 of the cells in Fig. 3 are shown in Fig. 4, in which the angle of the first division was arbitrarily set to zero and the angles of second divisions are given. It is evident that consecutive division axes formed a regular pattern, with equal probability that an attached cell would divide in the same axis in the vertical plane as in a perpendicular axis. Of these 96 cells, 13 could be followed for 3 undisturbed successive divisions. All four possible sequences of division angles were evident with approximately equal probability, as indicated in the outer ring of cells.

Figure 4.

Angles between division axes in two and three successive divisions. The angle of the first division vector for each cell was arbitrarily assigned to zero as shown in the “mother cell” in the center. The angle of the division vector for the second division is shown in the polar diagram, with the total number of cells in each quadrant indicated within the circle. Schematic examples of second divisions at 0°, 90°, 180°, and 270° are shown outside the circle. The numbers adjacent to the cells on the outer circle correspond to the number of cells that divided in the specified three-division sequence.

Two major conclusions can be reached from these studies. First, when the CHO cells were held fixed in a vertical plane, the direction of gravity had no effect on the orientation of division. A similar conclusion was reached in an earlier study with Chinese hamster and human kidney cells grown in monolayer (16). However, this study avoided the potential influence of cell spreading on division orientation. Because the division plane is perpendicular to the spindle axis (2, 3, 17), it appears that the establishment of spindle orientation by the movement and position of centrosomes overwhelms any possible gravitational effects, and that the randomness of the division axes reflects the randomness of the attachment of the cells to the adhesive sites. This is the case for observations of up to three cell cycles. Longer-term analyses of relationships between gravity and division in undisturbed cultures were not feasible with the current system because the culture flasks became overgrown within a few days with free daughter cells and had to be disturbed to remove the unbound cells and add fresh culture medium. However, when individual flasks were treated in this manner and observed for longer periods, all subsequent divisions were still random with respect to gravity.

Second, consecutive division axes in the vertical plane were arranged along one of two orthogonal axes in the CHO cells grown under conditions that mimicked suspension culture, similar to that seen in early embryo cleavages. However, unlike embryos, the choice of division plane appeared to be random because consecutive divisions of the cells were equally likely along the same or a perpendicular axis, e.g., three successive divisions along the same axis projected in the vertical plane were detected. Thus, if the position of the division axis is a consequence of the movement of centrosomes to opposite sides of the nucleus to establish the locations of the spindle ends, this movement can take place in the same plane, rather than an orthogonal plane, in two consecutive cell cycles.

It is evident from the video tapes that the cells undulated during growth while attached to the beads. Nevertheless, the precise pattern of successive divisions indicates that once the cells attached they either remained fixed and did not twist in the vertical plane, perhaps due to linkage between the adhesion sites and the cytoskeleton (18), or twisted at 90° or 180° only, which seems unlikely. It did appear, however, that when the cells entered mitosis there was little further movement, and they seemed to reach a fixed position with respect to the bead, and remained there through metaphase and anaphase. In light of the rarity of detection of acute or obtuse successive division angles, the possibility cannot be ruled out that the cells actively oriented themselves into a fixed position relative to the attachment site prior to entry into mitosis.

The culture technique described here has several potential applications in addition to the studies described. The cells could theoretically be held in any orientation, including inverted, for studying additional properties of attached cells. The newborn daughter cells shed from the surface could be used for studies on the cell cycle as performed in the past with bacteria and yeast (13, 14). In addition, the technique can be used to investigate segregation of components between cells at division because the results suggested that the site of attachment to the bead remained fixed.

Acknowledgments

I thank Maureen Thornton for expert technical assistance. This work was supported by National Aeronautics and Space Administration Grant NAGW-4503 and National Institutes of Health Grant GM26429.

Footnotes

This paper was submitted directly (Track II) to the Proceedings Office.

Abbreviations: CHO, Chinese hamster ovary; polyHEMA, poly-2-hydroxyethyl methacrylate.

References

- 1.Strome S. Cell. 1993;72:3–6. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90041-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wilson E B. The Cell in Development and Heredity. New York: Macmillan; 1925. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Costello D P. Biol Bull. 1961;120:285–312. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gilbert S F. Developmental Biology. Sunderland, MA: Sinauer; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Miquel J, Souza K A. Adv Space Biol Med. 1991;1:71–97. doi: 10.1016/s1569-2574(08)60121-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Claassen D E, Spooner B S. Int Rev Cytol. 1994;156:301–373. doi: 10.1016/s0074-7696(08)62257-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dan K. Dev Growth Diff. 1979;21:527–535. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-169X.1979.00527.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hyman A A, White J G. J Cell Biol. 1987;105:2123–2135. doi: 10.1083/jcb.105.5.2123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ferguson D J P. Cell Tissue Res. 1988;252:581–587. doi: 10.1007/BF00216645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Reinsch S, Karsenti E. J Cell Biol. 1994;126:1509–1526. doi: 10.1083/jcb.126.6.1509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chenn A, McConnell S K. Cell. 1995;82:631–641. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90035-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kraut R, Chia W, Jan L Y, Knoblich J A. Nature (London) 1995;383:50–53. doi: 10.1038/383050a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Helmstetter C E. New Biol. 1991;3:1089–1096. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Helmstetter C E, Eenhuis C, Theisen P, Grimwade J, Leonard A C. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:3445–3449. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.11.3445-3449.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Helmstetter C E. Biotechnol Bioeng. 1995;45:374–378. doi: 10.1002/bit.260450412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Todd P. In: Proceedings of the 1976 NASA Colloquium on Bioprocessing in Space. Morrison D R, editor. Washington, DC: NASA; 1976. pp. 103–115. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rappaport R. Int Rev Cytol. 1986;105:245–281. doi: 10.1016/s0074-7696(08)61065-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chen W-T, Hasegawa E, Hasegawa T, Weinstock C, Yamada K M. J Cell Biol. 1985;100:1103–1114. doi: 10.1083/jcb.100.4.1103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]