Abstract

Murine 3T3 cells arrest in a quiescent, nondividing state when transferred into medium containing little or no serum. Within the first day after transfer, fibroblasts can be activated to proliferate by platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF) alone; cells starved longer than 1 day, however, are activated only by serum. We demonstrate that endogenous vitamin A (retinol) or retinol supplied by serum prevents cell death and that retinol, in combination with PDGF, can fully replace serum in activating cells starved longer than 1 day. The physiological retinol derivative 14-hydroxy-4,14-retro-retinol, but not retinoic acid, can replace retinol in rescuing or activating 3T3 cells. Anhydroretinol, another physiological retinol metabolite that acts as a competitive antagonist of retinol, blocks cell activation by serum, indicating that retinol is a necessary component of serum. It previously has been proposed that activation of 3T3 cells requires two factors in serum, an activation factor shown to be PDGF and an unidentified survival factor. We report that retinol is the survival factor in serum.

Mammalian sera contain 1–2 μM vitamin A (retinol) (1). Retinol is metabolized by cells to physiological derivatives (2), including 11-cis-retinal involved in vision (3), retinoic acids that induce differentiation in a variety of systems (4), and three signaling molecules, 14-hydroxy-4,14-retro-retinol (14-HRR) (5, 6), anhydroretinol (AR) (7–9), and 13,14-dihydroxyretinol (DHR) (10). Of the retinoids, 14-HRR, DHR, and retinol, at least one is required in T lymphocyte activation (6, 10, 11) and for the growth of B lymphoblastoid (5, 6, 10, 12, 13) and HL-60 (8) cells when these cells are cultured in serum-free medium. AR competitively inhibits the growth-supportive effects of 14-HRR, DHR, or retinol (7–10). The enzyme, retinol dehydratase, which converts retinol to AR in the moth Spodoptera frugiperda recently has been purified, cloned, and expressed (14).

When deprived of serum, NIH 3T3 cells arrest in a nondividing, quiescent state (15, 16). Proliferation of cells starved for 1 day is reportedly stimulated by platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF) (17), fibroblast growth factor (18), epidermal growth factor (EGF) (19), and phorbol ester (20); however, cells starved longer can be activated only by serum (21). We show in this study that retinol in serum and its intracellular derivative, 14-HRR, play an essential role in 3T3 cell activation. Whereas PDGF and EGF are activation factors and initiate the cell cycle, retinol and 14-HRR ensure cell cycle progression by preventing cell death.

METHODS

Cell Activation Assays.

NIH 3T3 cells (American Type Culture Collection) plated in 96-well microtiter plates in 100 μl/well of DMEM containing 10% calf serum (Colorado Serum, Denver) were grown to almost confluency, then were arrested by starvation in 150 μl/well of DMEM containing 0.5% calf serum. Cells were starved for 2 days before the assay unless mentioned otherwise. Resting cells were treated with assay reagents in 200 μl/well of RPMI medium 1640 containing 0.1% BSA (Sigma) and labeled with 1 μCi [3H]thymidine (6.7 Ci/mmol, DuPont/NEN) for given durations. In Fig. 1, cells were labeled with [3H]thymidine for 24 hr starting from the activation event. In Fig. 2, cells were pulsed with thymidine for 2 hr at different time points after activation. In Fig. 3, cells were labeled with [3H]thymidine for 14 hr starting 10 hr postactivation. All culture media were supplemented with 2 mM glutamine and 100 units/ml of penicillin/streptomycin. The data represent the mean of triplicates. 14-HRR (6) and AR (22) were synthesized following published procedures; PDGF and EGF were purchased from Boehringer Mannheim; retinol, retinoic acid, and dexamethasone from Sigma; and ceramides and sphingosines from Calbiochem.

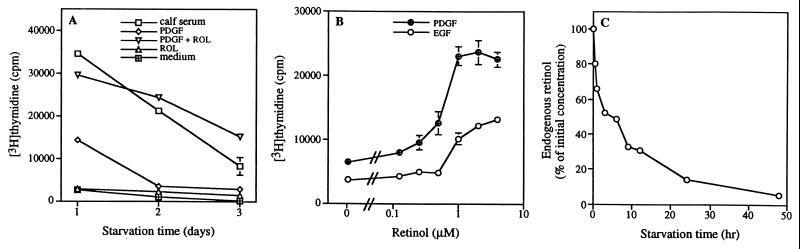

Figure 1.

Retinol is required for activation of NIH 3T3 cells arrested by serum starvation. (A) NIH 3T3 cells starved in DMEM containing 0.5% calf serum for 1–3 days were treated with 10% calf serum, 50 ng/ml PDGF, 2 μM retinol (ROL), a combination of 50 ng/ml PDGF and 2 μM retinol, or assay medium alone. (B) Dose-dependent activation of 2-day starved cells by retinol in the presence of PDGF (50 ng/ml) and EGF (50 ng/ml). (C) Relative intracellular retinol concentration in NIH 3T3 cells starved for the indicated time. Data of activation assays represent the mean and SDs of triplicate measurements.

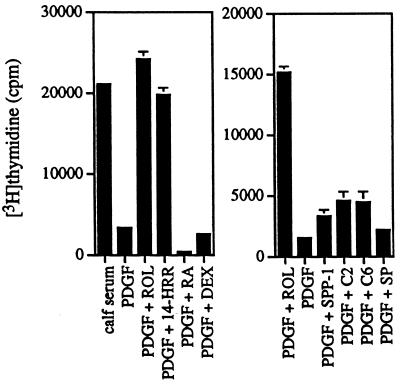

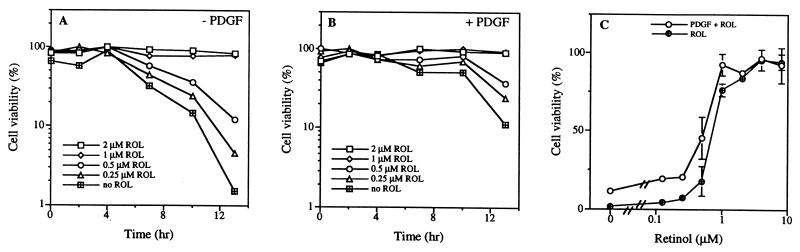

Figure 2.

Effect of different lipophilic molecules on PDGF activation of 2-day serum-starved cells: 50 ng/ml PDGF, 2 μM retinol (ROL), 4 μM 14-HRR, 4 μM retinoic acid (RA), 4 μM dexamethasone (DEX), 5[mu]M sphingosine-1-phosphate (SPP-1) 10 μM ceramide C-2 (C2), 10 μM ceramide C-6 (C6), and 5 μM sphingosine (SP). Data of activation assays represent the mean and SDs of triplicate measurements.

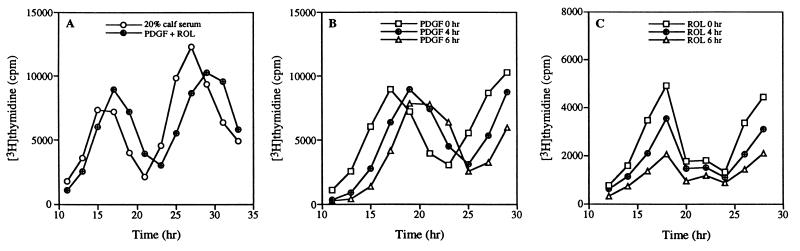

Figure 3.

PDGF determines entry time into S phase of cell cycle, and retinol determines number of activated cells. (A) Cell cycles of 2-day starved NIH 3T3 cells stimulated by 20% calf serum or by a combination of 50 ng/ml PDGF and 2 μM retinol (ROL). (B) Retinol (2 μM) was added at time 0 hr, PDGF (50 ng/ml) at time 0, 4, and 6 hr. (C) PDGF (50 ng/ml) was added at time 0 hr, retinol (2 μM) at time 0, 4, and 6 hr. Data represent the mean of triplicate measurements, and SDs were ≤15%.

Cell Survival Assays.

NIH 3T3 cells were plated and starved for 2 days as described above. Cells were treated with PDGF alone or PDGF plus retinol. After given time points cells were pulsed with WST-1 (5% vol/vol, Boehringer Mannheim) for 2 hr, and color development (A450nm-A650nm) was quantified using a 96-well reader (Molecular Dynamics).

Measurement of Intracellular Retinol Concentration.

NIH 3T3 cells were grown in 9 ml of DMEM containing 10% calf serum in 10-cm tissue culture dishes. At 30–40% confluency, 30 μCi [3H]retinol (DuPont/NEN) was added, and cells were grown for an additional 48 hr to almost confluency. Then cells were starved in DMEM containing 0.5% calf serum. At given time points cells were delipidated (23), and the organic extracts were analyzed as described (5).

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Cell activation was quantified by measuring [3H]thymidine incorporation in serum-starved, growth-arrested NIH 3T3 cells, which then were treated with serum, PDGF, retinol, or PDGF and retinol (PDGF/retinol) in assay medium (RPMI medium 1640 containing 0.1% BSA) (Fig. 1A). After 1 day of serum starvation, activation by PDGF alone reached approximately 50% of the level of serum activation. However, after serum starvation for 2 and 3 days, cells failed to be activated by PDGF alone due to cell death and were activated only by serum. We tested whether retinol was a fibroblast survival factor for the following reasons: (i) retinol is a component of serum (1); (ii) the intracellular retinol level decreases during starvation (8); and (iii) retinol supports the growth of B lymphoblastoid cells cultured in serum-free medium (5, 6, 12, 13). We found that addition of retinol indeed prevented cell death due to serum deprivation. Retinol by itself was not mitogenic, but in combination with PDGF it fully replaced serum in activating starved 3T3 cells regardless of the duration of serum starvation (Fig. 1A). Similar to PDGF, EGF activation of NIH 3T3 cells was also dependent on retinol, and retinol was effective at submicromolar concentrations (Fig. 1B).

We measured the endogenous retinol level in NIH 3T3 cells during serum starvation (Fig. 1C). After 24 hr of starvation, the intracellular retinol concentration decreased to about 10% of its initial level and to about 5% after 48 hr. The depletion of intracellular retinol mirrors the decreased viability after PDGF activation.

Other lipid molecules also were tested to determine whether they synergized with PDGF in activating starved 3T3 cells (Fig. 2). Only 14-HRR was able to replace retinol. In 3T3 cells, retinol is metabolized to 14-HRR (data not shown); therefore, 14-HRR may be the physiological mediator of retinol’s action. Retinoic acid showed a negative effect at the concentrations tested, and ceramides, sphingosine 1-phosphate, and sphingosine at their optimum concentrations gave 10–20% of the activity shown by retinol or 14-HRR. The glucocorticoid dexamethasone was inactive.

The time required for serum-starved cells to enter S phase of the cell cycle was identical whether the cells were activated by 20% calf serum or by PDGF/retinol (Fig. 3A). In both cases the cells required 12 hr from the start of activation to enter S phase and underwent more than one cell cycle. However, PDGF and retinol have distinct effects on cells entering the cell cycle. When added at different times, delayed addition of PDGF postponed S-phase entry but had no effect on the total number of activated cells (Fig. 3B); on the other hand, delayed addition of retinol decreased the total number of activated cells but had no effect on the time required for S-phase entry (Fig. 3C). These data imply PDGF acts as an activator that initiates the cell cycle, whereas retinol acts as a survival factor that ensures cell cycle progression by preventing cell death.

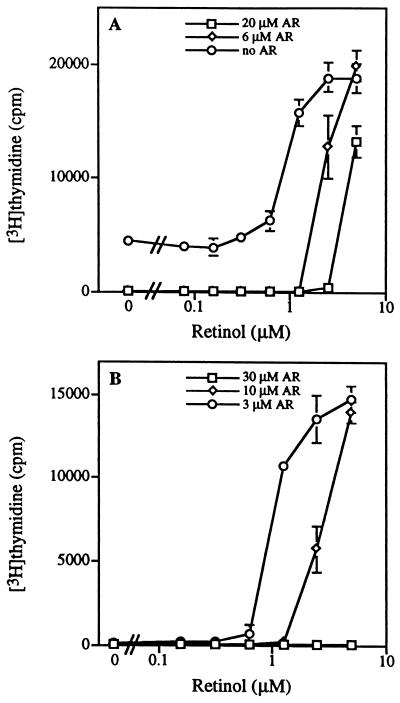

Being a competitive antagonist of retinol (7–9), AR provides a convenient means to determine whether retinol is required for 3T3 cell activation. AR competitively inhibited cell activation by PDGF/retinol in serum-starved 3T3 cells (Fig. 4A). AR also inhibited cell activation by serum in these cells (Fig. 4B). Furthermore, the inhibition by AR could be reversed by addition of retinol (Fig. 4 A and B) or 14-HRR (data not shown), strongly indicating that retinol supplied by serum is a requirement for 3T3 cell activation.

Figure 4.

AR blocks activation of NIH 3T3 cells by PDGF/retinol and by serum. (A) Addition of AR (20 μM, 6 μM, 0 μM) to 2-day serum-starved NIH 3T3 cells activated by PDGF (50 ng/ml) and retinol (0–5 μM). (B) Addition of AR (30 μM, 10 μM, 3 μM) to 2-day serum-starved NIH 3T3 cells activated by 5% calf serum supplemented with retinol (0–5 μM). Data represent the mean and SDs of triplicate measurements.

To determine whether retinol is required as a survival factor regardless of the activation status of NIH 3T3 cells, we used WST-1, a dye that monitors mitochondrial activity, to quantify the number of viable cells. In serum-starved resting cultures after treatment with assay medium alone or with PDGF the number of viable cells steadily decreased over time, and addition of retinol prevented cell death (Fig. 5 A and B). The presence of PDGF did not rescue cells from death; however, cell death was delayed for about 4 hr (Fig. 5B). In both cases the number of viable cells was dependent on the concentration of retinol, and the dose-response curve was not shifted by PDGF (Fig. 5C).

Figure 5.

Addition of retinol (ROL) prevents cell death. Time course of cell viability, as measured by WST-1, of 2-day serum-starved cultures after treatment with retinol (2 μM, 1 μM, 0.5 μM, 0.25 μM, 0 μM) (A) in assay medium alone and (B) in medium with PDGF (50 ng/ml). Data represent one of three independent measurements. (C) Dose-dependent prevention of cell death by retinol (0–10 μM) after 13-hr treatment in the absence or presence of PDGF (50 ng/ml). Data represent the mean and SDs of triplicate measurements.

We have demonstrated that retinol is necessary, and in combination with PDGF, is also sufficient to fully replace serum in activating serum-starved resting 3T3 cells. This result extends our knowledge of retinol dependency to fibroblasts and presents an example of full activation of 3T3 cells in defined medium. The 3T3 cell system distinguishes between activation and survival factors. PDGF is a major activation factor in serum. The existence of a survival factor in serum was first proposed 25 years ago (24, 25). The ability of retinol to sustain viability of 3T3 cells during serum starvation, regardless of the activation status, strongly suggests that retinol is the survival factor in serum. Earlier studies showed that retinol was essential for T lymphocyte activation (11) and for the growth of B lymphoblastoid (5, 6, 12, 13) and HL-60 (8) cells cultured in serum-free medium. We postulate that retinol’s survival effect also may contribute to the growth-supportive activity observed in T, B, and HL-60 cells.

Together with the published data on T and B lymphocytes (5, 6, 10–13) and promyelocytic cells (8), the present study suggests the existence of an intracellular signaling pathway dependent on vitamin A distinct from that of retinoic acid mediated by the nuclear receptors RAR and RXR (26, 27). In a retinol-dependent thymoma cell line AR-induced cell death can be prevented by the tyrosine kinase inhibitor, herbimycin A (28). The same herbimycin effect also was observed in 3T3 cells treated with AR (data not shown), implying that the retinol/14-HRR/AR signaling pathway in both lymphocytes and fibroblasts involves the regulation of tyrosine phosphorylation. Mammalian sera contain 1–2 μM retinol (1), tissues such as liver and lung contain micromolar concentrations of AR (data not shown); therefore, in these cells the balance between retinol and AR may determine the survival or death of cells.

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs. Ulrich Hämmerling and Lonny Levin and the members of the Buck laboratory for comments on the manuscript. This work was supported by grants from the American Cancer Society (J.B.) and National Institutes of Health (F.D. and J.B.). J.B. is a Pew Scholar in the Biomedical Sciences.

Footnotes

This paper was submitted directly (Track II) to the Proceedings Office.

Abbreviations: PDGF, platelet-derived growth factor; 14-HRR, 14-hydroxy-4,14-retro-retinol; AR, anhydroretinol; EGF, epidermal growth factor.

References

- 1.Goodman D S. In: The Retinoids. Sporn M B, Roberts A B, Goodman D S, editors. New York: Academic; 1984. pp. 41–48. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Blaner W S, Olson J A. In: The Retinoids: Biology, Chemistry, and Medicine. 2nd Ed. Sporn M B, Roberts A B, Goodman D S, editors. New York: Raven; 1994. pp. 229–256. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wald G. Science. 1968;162:230–239. doi: 10.1126/science.162.3850.230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gudas L J, Sporn M B, Roberts A B. In: The Retinoids: Biology, Chemistry, and Medicine. 2nd Ed. Sporn M B, Roberts A B, Goodman D S, editors. New York: Raven; 1994. pp. 443–520. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Buck J, Derguini F, Levi E, Nakanishi K, Hämmerling U. Science. 1991;254:1654–1656. doi: 10.1126/science.1749937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Derguini F, Nakanishi K, Hämmerling U, Buck J. Biochemistry. 1994;33:623–628. doi: 10.1021/bi00169a001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Buck J, Grün F, Derguini F, Chen Y, Kimura S, Noy N, Hämmerling U. J Exp Med. 1993;178:675–680. doi: 10.1084/jem.178.2.675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Eppinger T M, Buck J, Hämmerling U. J Exp Med. 1993;178:1995–2005. doi: 10.1084/jem.178.6.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Derguini F, Nakanishi K, Buck J, Hämmerling U, Grün F. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 1994;33:1839–1841. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Derguini F, Nakanishi K, Hämmerling U, Chua R, Eppinger T, Levi E, Buck J. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:18875–18880. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.32.18875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Garbe A, Buck J, Hämmerling U. J Exp Med. 1992;176:109–117. doi: 10.1084/jem.176.1.109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Buck J, Ritter G, Dannecker L, Katta Y, Cohen S L, Chait B T, Hämmerling U. J Exp Med. 1990;171:1613–1624. doi: 10.1084/jem.171.5.1613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Buck J, Myc A, Garbe A, Cathomas G. J Cell Biol. 1991;115:851–859. doi: 10.1083/jcb.115.3.851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Grün F, Noy N, Hämmerling U, Buck J. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:16135–16138. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.27.16135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Todaro G J, Lazar G K, Green H. J Cell Comp Physiol. 1965;66:325–334. doi: 10.1002/jcp.1030660310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Holley R W, Kiernan J A. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1968;60:300–304. doi: 10.1073/pnas.60.1.300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pledger W J, Hart A A, Locatell K L, Scher C D. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1981;78:4358–4362. doi: 10.1073/pnas.78.7.4358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gospodarowicz D. Nature (London) 1974;249:123–127. doi: 10.1038/249123a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Leof E B, Van Wyk J J, O’Keefe E J, Pledger W J. Exp Cell Res. 1983;147:202–208. doi: 10.1016/0014-4827(83)90285-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rozengurt E, Rodriguez-Pena A, Combs M, Sinnett-Smith J. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1984;181:5748–5752. doi: 10.1073/pnas.81.18.5748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Brooks R F, Howard M, Leake D S, Riddle P N. J Cell Sci. 1990;97:71–78. doi: 10.1242/jcs.97.1.71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Embree N D. J Biol Chem. 1939;128:187–198. [Google Scholar]

- 23.McLean S W, Ruddel M E, Gross E G, De Giovanna J J, Peck G L. Clin Chem. 1982;28:693–696. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Paul D, Lipton A, Klinger I. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1971;68:645–648. doi: 10.1073/pnas.68.3.645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lipton A, Paul D, Henahan M, Klinger I, Holly R W. Exp Cell Res. 1972;74:466–470. doi: 10.1016/0014-4827(72)90402-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mangelsdorf D J, Umesono K, Evans R. In: The Retinoids: Biology, Chemistry, and Medicine. 2nd Ed. Sporn M B, Roberts A B, Goodman D S, editors. New York: Raven; 1994. pp. 319–349. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mangelsdorf D J, Thummel C, Beato M, Herrlich P, Schütz G, Umesono K, Blumberg B, Kastner P, Mark M, Chambon P, Evans R M. Cell. 1995;83:835–841. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90199-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.O’Connell M J, Chua R, Hoyos B, Buck J, Chen Y, Derguini F, Hämmerling U. J Exp Med. 1996;184:549–555. doi: 10.1084/jem.184.2.549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]