Abstract

We report the isolation of 15 Neurospora crassa mutants defective in “quelling” or transgene-induced gene silencing. These quelling-defective mutants (qde) belonging to three complementation groups have provided insights into the mechanism of posttranscriptional gene silencing in N. crassa. The recessive nature of the qde mutations indicates that the encoded gene products act in trans. We show that when qde genes are mutated in a transgenic-induced silenced strain containing many copies of the transgene, the expression of the endogenous gene is maintained despite the presence of transgene sense RNA, the molecule proposed to trigger quelling. Moreover, the qde mutants failed to show quelling when tested with another gene, suggesting that they may be universally defective in transgene-induced gene silencing. As such, qde genes may be involved in sensing aberrant sense RNA and/or targeting/degrading the native mRNA. The qde mutations may be used to isolate the genes encoding the first components of the quelling mechanism. Moreover, these quelling mutants may be important in applied and basic research for the creation of strains able to overexpress a transgene.

The introduction of transgenes in plants and fungi has been shown to lead to gene silencing. In plants, gene silencing has been found to occur at two levels, transcriptional and posttranscriptional (1, 2). Generally in plants, transcriptional inactivation requires homology between promoters (3, 4). In contrast, homology in transcribed regions has been shown to induce posttranscriptional gene silencing or cosuppression (5, 6). In the filamentous fungus Neurospora crassa, the introduction of transgenes has been shown to lead to two different types of gene inactivation phenomena. In the sexual phase, the duplicated genes can be irreversibly inactivated by a mechanism called RIP (repeat induced point mutation), whereby gene inactivation is caused by a high rate of point mutation (7). In contrast, during the vegetative phase, the transgene can induce reversible gene silencing by a phenomenon called quelling (8).

We have begun to use a molecular–genetic approach to dissect the mechanism of quelling in N. crassa, using a gene (al-1) essential for biosynthesis of carotenoids, which provides a simple visual reporter for quelling. In these studies several characteristic features of quelling have been defined: (i) the gene inactivation by quelling is reversible and the reversion is correlated with the release of exogenous DNA; (ii) the reduction of mRNA steady-state level of the duplicated gene is due to a posttranscriptional effect on its accumulation; (iii) the transgenes containing transcribed regions of at least 132 bp are able to induce gene silencing, whereas the promoter regions are ineffective; (iv) quelling is dominant in heterokaryotic strains containing a mixture of transgenic and nontransgenic nuclei, indicating the involvement of a diffusible trans-acting molecule; and (v) the expression of unexpected transgenic sense RNA is correlated with silencing, suggesting involvement of an RNA transcript in mediating quelling (8, 9).

Based on the above information on the mechanism of quelling in N. crassa, several parallel features can also be found in gene silencing in plants. The major similarity is the fact that gene quelling in N. crassa and cosuppression in plants both involve posttranscriptional gene silencing. As molecular and biochemical approaches have to date failed to uncover the exact posttranscriptional mechanism involved, a genetic approach to identify components of this machinery is attractive. In plants, Arabidopsis mutants have been isolated in which the timing of rolB transgene silencing is altered (10). However, while gene silencing is accelerated in these mutants, it is not disrupted. Thus, no plant mutants deficient in the silencing machinery have been isolated.

Here we describe the isolation of N. crassa qde (quelling defective) mutants in which quelling or gene silencing is completely abrogated. The mutations identified fall into three complementation groups, which have each been shown to abrogate simultaneously quelling of several different genes. This result suggests that the affected genes may encode three separate components involved in the general mechanism of gene silencing in N. crassa.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Strains and Growth Conditions.

The N. crassa methodology used was substantially the same as described (11). The N. crassa strains used, obtained from the Fungal Genetics Stock Center at the University of Kansas were as follows: FGSC no. 3958 a (qa-2; aro-9) and FGSC no. 3957 A (qa-2; aro-9). For the forced heterokaryon experiments we first constructed a suitable strain (TB1) with two selectable markers, qa-2/aro-9 (unable to grow on minimal medium) and Bml (benomyl-resistant). A (qa-2; aro-9) strain was transformed with plasmid pMXY2 (12) containing Bml (benomyl-resistant β-tubulin gene) that functions as a dominant selectable marker in N. crassa (14). Transformant TB1, resistant to benomyl, was isolated by plating spheroplasts on minimal media containing 1 mg/l of benomyl and 1× qa Mix (50× qa Mix = 4 mg/ml l-tyrosine/4 mg/ml l-tryptophan/4 mg/ml l-phenylalanine/12.5 μg/ml p-aminobenzoic acid). Conidia of strain TB1 (qa-2; aro-9; Bml) were mixed with conidia of each qde mutant and inoculated on minimal medium plus 1 mg/l benomyl, with permissive growth conditions for forced heterokaryotic strains only. Minimal medium plus 1× qa Mix was used as the permissive medium for growth of the (qa-2; aro-9) strain; in the qa selective medium sucrose was replaced by 10 mM quinic acid.

Transformation of N. crassa.

Spheroplasts were prepared according to the protocol of Vollmer and Yanofsky (13). The 6xw and 5xw strains were obtained by transformation of spheroplasts of strain FGSC no. 3958 with pX16 (9) containing the qa-2 gene as a selectable marker.

The plasmid pN containing a portion of al-2 gene sequence (see below) was cotransformed with plasmid pMXY2, which contains Bml. The frequency of quelling of the al-2 gene was calculated by selecting benomyl-resistant transformants that were then scored for carotenogenesis by visual inspection of conidial color: wild-type colonies were orange, whereas white to yellow transformants were indicative of silencing.

Recombinant Plasmid.

The pN plasmid was constructed by cloning a 1,540-bp region of the al-2 coding sequence (15) into the EcoRI site of pBSSK II+ (Stratagene). The 1,540 bp fragment was amplified from genomic DNA by PCR using two primers complementary to bases 1,751–1,770 (5′-CCGAATTCAACAATCAACAAAACCCGCC-3′) and 3,271–3,290 (5′-CCGAATTCCATACAACGCCCTCAACAGC-3′) of the al-2 gene. The underlined nucleotides represent the EcoRI restriction sites used for cloning.

Southern and Northern Blot Hybridizations.

Chromosomal DNA from qde mutants was prepared as described by Morelli et al. (16). Genomic DNA was digested and blotted as described in Maniatis et al. (17). The probe specific for al-1 consisted a 1,550-bp XbaI/ClaI fragment of the pX16 (9). The RNA was electrophoresed on agarose gels, transferred onto Hybond-N (Amersham) membranes, and probed with a probe specific for al-1 gene (see above). Normalization was performed using as probe a PCR fragment amplified with two oligonucleotides (the same used in the construction of pN plasmid) specific for the al-2 gene.

Dot Blot Analysis.

Five micrograms of genomic DNA was spotted onto Hybond-N membranes and probed with a probe specific for al-1 and with a probe specific for the single copy gene sod-1 (18). The radioactive signals were quantified by using a Packard Instant Imager instrument. The al-1 transgene copy number in each mutant was estimated as follows: for each mutant the ratio between the cpm of the DNA spot derived from the al-1 probe and the cpm derived from the sod-1 probe was calculated. This ratio was then divided by the ratio of al-1/sod-1 cpm calculated from spots of DNA from an untransformed strain. Results reported are the average of three different experiments.

RNase Protection Analyses.

Total RNA was extracted from frozen mycelia either grown in the dark or after irradiation with blue light according to Baima et al. (19). The RNA probes used in the RNase protection experiments (see Figs. 2 and 6) were prepared by in vitro transcription of the plasmid pALC4 (9) using T3 polymerase. The in vitro transcription reactions and the RNase protection assays were performed using the Ambion (Austin, TX) transcription kit according the manufacturer’s instructions. For RNase protection assays, 1 μg of total RNA was used in each reaction.

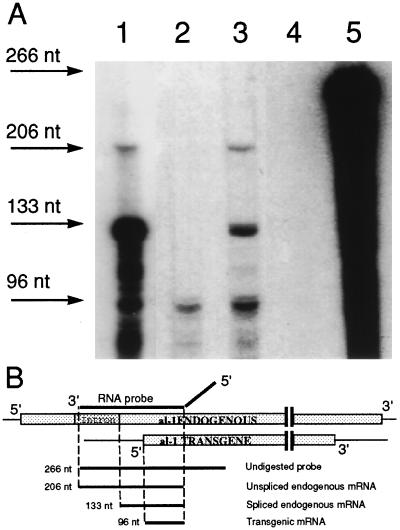

Figure 2.

RNase protection experiments for sense al-1 RNA transcripts in strain 6xw. (A) RPA was performed on total RNA extracted from wild-type untransformed strain illuminated for 20 min with light (lane 1), dark-grown transformant 6xw (lane 2), 6xw illuminated for 20 min (lane 3), dark-grown wild type (lane 4). Arrows indicate the sizes of the protected fragments obtained from the unspliced endogenous al-1 mRNA (206 nt), from the mature endogenous al-1 mRNA (133 nt), and from the transgenic al-1 sense RNA (96 nt). Undigested al-1 RNA probe (266 nt) is shown in lane 5. (B) Map of endogenous and potential transgenic sense transcripts. The pALC4 plasmid, which contains a single intron, was used to generate an RNA probe capable of hybridizing to sense al-1 mRNA. This RNA probe is indicated as a solid black line. The diagonal portion of the RNA probe represents plasmid sequences not present in the N. crassa al-1 mRNA. Shaded boxes represent sense RNA from the endogenous native al-1 RNA gene (Upper) and a putative sense RNA from the al-1 transgene (Lower).

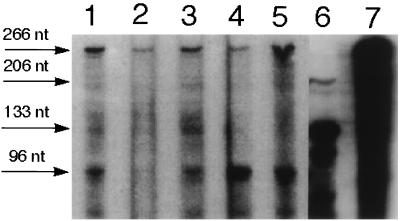

Figure 6.

RNase protection experiments for transgenic sense al-1 RNA transcripts in mutant strains. RPA was performed, using an RNA probe as described in Fig. 2B, on total RNA extracted from dark-grown mutants representative of each group (M10, M30, M20, M17) (lanes 1–4), from dark-grown transformant 6xw (lane 5), and from an untransformed strain illuminated for 20 min (lane 6). Undigested al-1 RNA probe is shown in lane 7. Arrows indicate the size of the protected fragments obtained from the unspliced endogenous al-1 sense RNA (206 nt), the mature endogenous al-1 mRNA (133 nt), and the transgenic al-1 sense RNAs (96 nt). Undigested probe (lane 7) of 266 nt is indicated by an arrow. Sizes of the protected fragments are as in Fig. 2B.

RESULTS

Isolation of a Stable Silenced Strain.

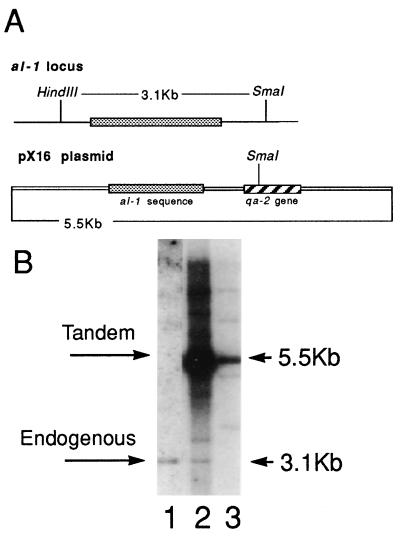

We have previously demonstrated that the phenomenon called quelling takes place at a high frequency, but is an unstable process (8, 9). The ability of most quelled strains to revert to a wild-type phenotype precludes using genetic selection to identify mutants in the process. To circumvent this problem, we carried out a large-scale screening to identify transformants with a stable silenced phenotype. To isolate a stable silenced strain, a N. crassa strain containing a wild-type al-1+ gene (orange phenotype) (al-1+; qa-2; aro-9) was transformed with plasmid pX16 containing qa-2 and a 1,500-bp fragment of the coding sequence of the al-1 gene (Fig. 1A). About 200 independent Qa+ transformants showing an albino phenotype were isolated and their frequency of reversion to orange color was analyzed. Two independent albino transformants (5xw and 6xw) showed no reversion: 0 revertants/10,000 descendant colonies. To test whether these were stably quelled strains or strains disrupted in the albino gene, we used Southern blot analysis on DNA digested with enzymes that distinguish the transgene (5.5 kb) from the endogenous al-1 gene (3.1 kb) (Fig. 1). In strain 5xw the transgene is present, whereas the native al-1 gene is disrupted, presumably by the transgene (Fig. 1, lane 3). In contrast, strain 6xw has tandem insertions of the transgene and an intact native al-1 gene (Fig. 1, lane 2).

Figure 1.

Southern hybridization analysis of the stable albino transformant strains. (A) Schematic representation of al-1 endogenous locus and of plasmid pX16 used in transformation experiments. (B) SmaI/HindIII-digested genomic DNA extracted from wild-type untransformed strain (lane 1), strain 6xw (lane 2), and strain 5xw (lane 3) was hybridized with an al-1 probe able to detect both endogenous and transgenic al-1 copies. The 3.1-kb band corresponding to the endogenous al-1 gene and the 5.5-KB band corresponding to the tandem repeated insertions are indicated by arrows.

To further verify that posttranscriptional gene silencing is operating in strain 6xw, we analyzed the levels of the al-1 RNA. We previously showed that in an al-1 quelled strain the level of unspliced al-1 mRNA is similar in quelled and wild-type strains, whereas native al-1 mRNA is heavily reduced, indicating that quelling affects the level of the mature mRNA and not the rate of transcription. We analyzed al-1 RNA in strain 6xw by an RNase protection assay (RPA) able to discriminate between mature and precursor al-1 mRNAs (Fig. 2B). Using this assay, RNA isolated from 6xw mycelia irradiated 20 min with light (Fig. 2A, lane 3) was shown to contain levels of unspliced mRNA similar to wild type (Fig. 2A, lane 1), whereas the level of mature al-1 mRNA was reduced. This RNA profile is consistent with 6xw being a quelled strain. Moreover, the quelled strain 6xw contains a transgenic sense RNA detected in all quelled strains. This transgenic sense RNA is also present in the dark-grown quelled strain (Fig. 2A, lane 2) (9) whereas it is not detected in the dark-grown wild-type strain (Fig. 2A, lane 4). The degradation product present in light-induced wild-type RNA (Fig. 2A, lane 1) that comigrate with the 96-nt band is probably derived from large protected fragments. The genetic experiments described below further confirm that this strain 6xw is indeed a quelled strain.

Isolation of Quelling Deficient (qde) Mutants.

Strain 6xw, in which the al-1+ gene is stably quelled (albino phenotype), was UV mutagenized to select for mutations that abolished quelling (orange phenotype). Nineteen putative mutants were recovered out of approximately 100,000 survivors screened. To discriminate true mutations from revertants that have simply lost copies of the transgene, we performed a DNA dot blot analysis (see Materials and Methods). Dot blots of genomic DNA extracted from each mutant were hybridized with an al-1 probe and with a probe of the single copy gene sod-1 (18) as a control to estimate the copy number of transgenic al-1. By this criterion, two classes of mutants were identified: group 1 consisting of 15 mutants which each retained high copy number of the transgene (25–35 copies), and group 2 consisting of four mutants in which the copy number was reduced (4–6 copies) (Table 1).

Table 1.

al-1 transgenic DNA copy number in mutant strains

| Group 1

|

Group 2

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Mutant strain | copy number | Mutant strain | copy number |

| M2 | 30 ± 7 | M30 | 4 ± 1 |

| M4 | 27 ± 8 | M34 | 5 ± 1 |

| M7 | 26 ± 5 | M35 | 4 ± 1 |

| M10 | 25 ± 8 | M43 | 4 ± 1 |

| M11 | 26 ± 7 | ||

| M12 | 30 ± 7 | ||

| M17 | 25 ± 7 | ||

| M18 | 24 ± 7 | ||

| M20 | 26 ± 5 | ||

| M24 | 25 ± 7 | ||

| M37 | 32 ± 5 | ||

| M40 | 25 ± 5 | ||

| M41 | 25 ± 7 | ||

| M46 | 25 ± 5 | ||

| M47 | 32 ± 6 | ||

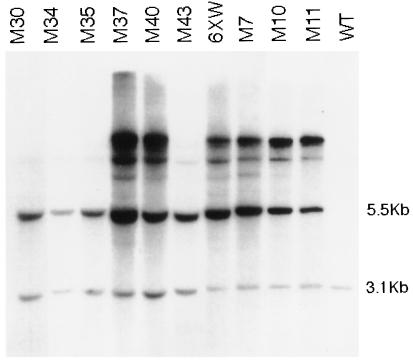

To determine whether any of the putative quelling-deficient mutants were the result of transgene rearrangement, Southern hybridization analysis was performed. The results for nine representative strains and for original strain 6xw are shown (Fig. 3). Genomic DNA extracted from each of the mutant strains was digested with enzymes (SmaI and HindIII) that distinguish the tandem of transgenes (5.5 kb) from the endogenous al-1 gene (3.1 kb) (see Fig. 1) and hybridized with an al-1 probe. Larger bands may represent different integration events or may be caused by methylation of restriction sites in the transgenes. The digestion patterns of all group 1 mutants were qualitatively identical, demonstrating that none were the result of gross transgene rearrangement, whereas the digestion patterns of group 2 mutants confirm that the copy number of the transgenes was reduced. The genetic experiments described below further confirm that the release of gene silencing in group 1 mutants does not depend on rearrangements of the transgenic DNA loci.

Figure 3.

Southern hybridization analysis of the mutants. SmaI/HindIII-digested genomic DNA extracted from five representative mutants of group 1 (M37, M40, M7, M10, M11), mutant strains of group 2 (M30, M34, M35, M43), the quelled strain (6xw), and a wild-type untransformed strain (WT). The DNA digestions were blotted and probed with a DNA fragment able to detect both endogenous and transgenic al-1 copies. The 3.1-kb band corresponding to the endogenous al-1 gene and the 5.5-kb band corresponding to the plasmid arranged in tandem repeats are indicated.

Taken together, these results suggest the existence of two classes of mutants. In group 2 mutants, the quelling deficiency appears to be due to loss of exogenous copies. In contrast, in group 1 mutants both the copy number and the arrangement of transgenic loci remain unchanged with respect to original strain 6xw. Thus group 1 mutations are candidates for extragenic loci involved in transgene silencing.

To demonstrate that the orange phenotype of the putative qde mutants was due to a restoration of al-1+ gene expression, we analyzed the levels of al-1 mRNA in group 1 and group 2 mutants. Total RNA extracted from mycelia of mutant strains after 20 min of light induction were hybridized with an al-1 probe. As shown for eight representative mutant strains in Fig. 4, all mutants analyzed showed a wild-type level of accumulation of al-1 mRNA.

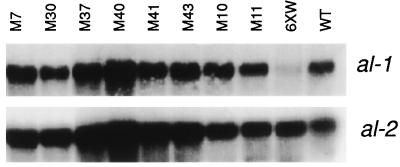

Figure 4.

Analysis of al-1 gene expression in mutant strains. Total RNA extracted from mycelia, illuminated for 20 min, of eight representative mutants (M7, M30, M37, M40, M41, M43, M10, M11), strain 6xw, and wild type. After blotting, RNAs were hybridized with an al-1 probe. Control hybridization was performed with the photoregulated al-2 gene.

The qde Mutants Relieve Silencing of a Second Gene, qa-2.

The above experiments establish that the al-1 gene is relieved from quelling in the qde mutants. We next tested whether the qde mutations also relieved silencing of other marker genes in strain 6xw. Because the plasmid used to transform strain 6xw contains the selectable marker qa-2, we monitored whether qa-2 transgene expression was enhanced in the qde mutants compared with original strain 6xw. Two methods were used: analysis of qa-2 mRNA and analysis of growth on selection medium.

The quelled strain 6xw containing the qa-2 transgene was selected for its ability to grow on minimal medium. However, growth rate experiments demonstrate that strain 6xw grows at 20% of the wild-type growth rate (Fig. 5A, compare lanes 1 and 5). A normal growth rate could be restored in strain 6xw by the addition of a mixture of aromatic amino acids, which by-pass the metabolic restrictions (Fig. 5A, compare lanes 6 and 10). This growth defect of the stably quelled strain 6xw suggests that expression of the qa-2 selectable marker transgene is suboptimal. In contrast, all the qde mutants isolated showed normal growth on minimal medium, as shown for strains representative of the three complementation groups described below (Fig. 5A, lanes 2–4). These growth studies suggest that the qa-2 transgene is expressed at higher levels in the qde mutants relieved of quelling of the al-1 gene. Moreover, the release of qa-2 silencing in the qde strains is most dramatically demonstrated by the growth rate measured on selection medium containing quinic acid as the sole carbon source. Under these selection conditions, only the product of the qa-2 gene will enable growth. The growth rate of the stably quelled strain 6xw is only 1% of the wild-type strain in these culturing conditions (Fig. 5A, lane 15). On the other hand, the qde mutants grew as well as wild type on this stringent selection medium (Fig. 5A, lanes 11–14). Northern blot analysis of qa-2 mRNA in the representative qde mutants demonstrated that the expression of the qa-2 transgene was enhanced in the mutants compared with the stably quelled strain 6xw (see Fig. 5B).

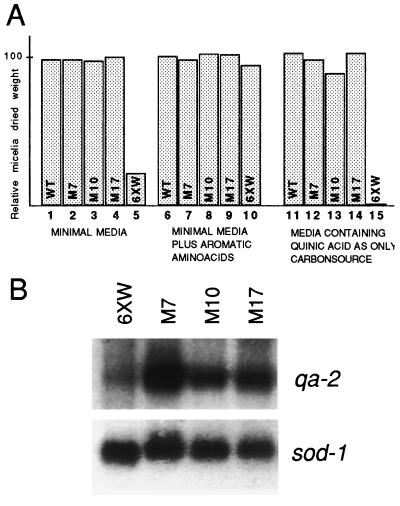

Figure 5.

Expression of qa-2 transgenes in qde mutants. (A) Histograms indicate the relative dry weight of mycelia from qde mutants grown in different media as indicated. Three representative mutants (M7, M10, M17) are compared with the 6xw and wild-type strains. (B) Northern blot analysis of qa-2 gene expression in qde mutants and strain 6xw. Total RNA extracted from mycelia grown in presence of 10 mM quinic acid as inducer of qa-2 expression was hybridized with a qa-2 probe. A sod-1 probe was used as normalization control.

Molecular Genetic Analysis of the qde Mutants Defines Three Complementation Groups.

Molecular analysis separated the 19 putative qde mutants into two groups based on transgene copy number (see Table 1). We next used a genetic approach to classify the mutants into complementation groups. Quelling has been shown to be a dominant trait, operative in heterokaryotic strains containing a mixture of silenced and nonsilenced nuclei (9). The dominant nature of quelling predicts that a heterokaryotic strain produced from a wild-type (orange) and a qde recessive mutant (orange) strain should show an albino phenotype. In contrast, in the case of mutants caused by loss of transgenic copies (e.g., group 2 mutants; Table 1) complementation in the heterokaryon is not expected. To analyze the genetic nature of the mutation in qde strains, forced heterokaryons were created to contain wild-type and mutant alleles of the qde genes. For the forced heterokaryon tests conidia of each qde mutant (qde; qa-2+; bml) were mixed with conidia of strain TB1 (qde+; qa-2; aro-9; Bml) (see Materials and Methods) and plated on medium containing benomyl. The group 1 mutants shown to contain high copy number of the transgene displayed an albino phenotype in forced heterokaryons with strain TB1 containing a wild-type allele of qde. This result suggests that the mutations of the group 1 mutant strains in Table 1 act as recessive mutations (Table 2). In contrast, the group 2 mutants containing low copy number of the transgene failed to complement. These genetic results reinforce the notion that the release of silencing in group 2 mutants is due to the loss of transgene copies.

Table 2.

Mutant complementation groups

| Recessive

| |||

|---|---|---|---|

| qde-1 | qde-2 | qde-3 | Nonrecessive |

| M2 | M10 | M4 | M30 |

| M7 | M11 | M17 | M34 |

| M12 | M18 | M35 | |

| M20 | M40 | M43 | |

| M24 | M41 | ||

| M37 | |||

| M46 | |||

| M47 | |||

The above studies determined that the group 1 mutations were recessive and could therefore be further analyzed by testing each mutant pairwise in heterokaryons with each of the other group 1 mutants to distinguish complementation groups. A heterokaryon between two qde strains (orange) containing recessive mutations is expected to show an albino phenotype if the mutations are in different loci. If instead two qde mutants are alleles, an orange phenotype is expected. The results summarized in Table 2 indicate that the group 1 recessive mutants fall without exceptions into three complementation groups, suggesting that three distinct genetic loci, qde-1, qde-2, and qde-3, are involved in release of gene silencing.

Recessive qde Mutants Are Impaired in All Gene Silencing Events.

The above tests classify the group 1 qde recessive mutants into three complementation groups, separate from the group 2 mutations. Representatives of these four classes of mutants were tested for their ability to quell an additional gene, al-2+. We compared the quelling frequency of the al-2 gene (albino) in the qde mutants and in a Qde+ strain (Table 3). Spheroplasts of a wild-type strain and of recessive mutant strains M7, M11, M18, representative of each complementation group and of the mutant M34 representative of the nonrecessive group, were cotransformed with the plasmid pN containing the 3′ portion of al-2 (see Materials and Methods) and the plasmid pMXY2 carrying Bml. For the recessive group 1 qde mutants (M7, M11, M18) no quelled transformants were isolated. This result indicates that the three qde complementation groups identified control silencing of at least three distinct transgenes, suggesting that these loci control a general pathway for gene silencing in N. crassa. In contrast, the quelling frequency of a group 2 mutant strain (M34) was the same as wild type, indicating no defect in the quelling machinery. This result confirms that the release of silencing of the al-1+ gene in the strains belonging to group 2 was exclusively due to the loss of transgenic copies.

Table 3.

Quelling frequency for the al-2+ gene in representative mutant strains

| Strain used | Complementation group | Transformant phenotypes

|

Total | Quelling frequency, % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Orange | Nonorange | ||||

| M7 | I | 200 | 0 | 200 | 0 |

| M11 | II | 200 | 0 | 200 | 0 |

| M18 | III | 300 | 0 | 300 | 0 |

| M34 | Group 2 | 182 | 28 | 210 | 13 |

| WT | 89 | 11 | 100 | 11 | |

The qde Mutants Accumulate RNA Transcripts of the Transgene.

Previously we demonstrated a strong correlation between unintended transcription of al-1 transgene and al-1 gene silencing. These results suggested a possible role for transgenic sense RNAs in mediating gene silencing. As expected, the transgenic sense RNAs were present in the stably quelled strain 6xw (see Fig. 2A). With the qde mutants in hand, we could test whether the mutations affected the accumulation of transgenic sense RNAs or acted downstream in the quelling machinery. Levels of transgene sense RNAs were monitored in the 19 strains belonging to the four classes of mutants released from quelling (Fig. 6). An RPA was performed on total RNA extracted from mycelia using an RNA probe able to discriminate between the transcripts of the al-1 transgene (protected 96-nt fragment) and those of the endogenous al-1+ gene (protected 206-nt fragment). Furthermore, we enhanced detection of transgenic sense RNA by using RNA isolated from dark-grown mycelia that do not express the endogenous al-1+ mRNA. Fig. 6 reports the RPA results obtained from one representative mutant for each of the four mutant classes. The al-1 transgenic sense RNA was detected in all group 1 recessive mutants examined (Fig. 6, lanes 1, 3, and 4). In contrast, the transgenic sense RNA was absent in the group 2 nonrecessive mutants (Fig. 6, lane 2). These results indicate that only mutations that act recessively (e.g., where quelling can be restored in heterokaryosis with a qde+ strain) contain the sense transgenic RNA. This result is a further demonstration that transgenic sense RNA is required for quelling. Moreover, these results imply that the qde products act downstream of this sense RNA molecule to release quelling.

DISCUSSION

The introduction of the al-1 gene into N. crassa by transformation has established a model genetic system in which a visual assay (color) can be used to identify quelled strains as well as mutants defective in quelling. As quelling is a posttranscriptional transgene-induced gene silencing mechanism analogous to cosuppression in plants, N. crassa mutants defective in quelling should provide the first tools to isolate components involved in the transgene-induced gene silencing machinery.

To screen genetically for mutants defective in quelling we first isolated a transgenic N. crassa strain (6xw) that is stably quelled. Molecular analysis suggested that the albino phenotype of strain 6xw was due to quelling of the resident al-1+ gene. These parameters include a reduction of mature native al-1 mRNA, normal levels of precursor native al-1 RNA, and the presence of sense transgenic al-1 transcripts shown previously to correlate with quelling (9). The quelling-defective (qde) mutants (orange) were isolated by mutagenesis of the stably quelled transformant 6xw (albino). Fifteen recessive qde mutants belonging to three complementation groups were isolated. These qde mutants were shown to be truly relieved of quelling as they contain increased levels of native al-1 mRNA. Furthermore, the transgene-selectable marker qa-2 was expressed at a higher level in all the qde mutants, suggesting that qa-2 transgene was partially silenced in strain 6xw. This finding suggests that the qde genes control silencing not only of the al-1 endogenous gene but also of the qa-2 transgene. Thus, two distinct genes were released from silencing in the qde strains, suggesting defects in a general silencing mechanism. However, whether or not only one mechanism for transgene induced silencing in N. crassa exists, as suggested by these experiments, has still to be demonstrated.

To gain further insights into the quelling mechanism, molecular analysis on the qde mutants was performed. We showed that the qde mutations do not reverse quelling by lowering the copy number of the transgene, as qde mutants blocked in quelling retain a high copy number of the transgene. Furthermore, we showed that these qde mutants with a high copy of the transgene still contain the transgenic sense RNA proposed to be required for quelling (9). The significance of this transgene sense RNA is highlighted by the contrast between the genetic analysis of the qde mutants and a second group of mutants as follows.

In addition to the 15 recessive qde mutants, we also identified a second class of isolates in which quelling was released (group 2). Members of group 2 (orange) were shown to be relieved of quelling because they have a reduced copy number of the transgene and produce no transgene sense RNA. Furthermore, genetic experiments demonstrate that silencing can be restored when qde strains (producing the transgene sense RNA) are placed in a heterokaryon with a wild-type strain. In contrast, silencing cannot be restored when group 2 mutants are in a similar heterokaryon. This important genetic distinction between group 1 recessive qde mutants and group 2 (nonrecessive mutants) supports the notion that the transgenic sense RNA present in the qde mutants is essential for silencing in the heterokaryon. The involvement of sense RNA in posttranscriptional gene silencing has been proposed based on the correlation between the accumulation of a transgenic transcript from a promoterless construct and quelling. In plants it has been proposed (20) that when transgenic mRNA accumulation reaches a threshold, specific degradation of both endogenous and transgenic mRNA could be induced. However, this threshold hypothesis seems to be inconsistent, for example, with the observation that promoterless constructs of the chs gene in petunia are able to induce silencing just as well as does the construct carrying a strong promoter (21). Also in N. crassa we have found that the level of expression of a promoter-driven transgene is not sufficient to trigger gene silencing (8). English et al. (22) proposed that a qualitatively aberrant feature of transgenic RNA, rather than a high level of transgenic RNA accumulation, can trigger gene silencing. In this model the aberrant sense RNA could be recognized by an RNA-dependent RNA polymerase, leading to the production of antisense RNA, formation of double stranded RNA and RNA degradation (23, 24).

In N. crassa, we have been able to use a simple method of genetic screening to identify components of the silencing machinery that may be used to dissect the analogous system in plants. The recessive nature of the qde mutants indicates that the gene products of the qde+ strains normally act in trans to silence genes posttranscriptionally in quelled strains. As such, we propose that qde products may “sense” the aberrant sense RNA by direct or indirect interaction. In addition, one or more of the qde products may be involved in targeting and/or degradation of the endogenous mRNA. Furthermore, it may be that the qde mutants are universally defective in transgene-induced gene silencing, as we have shown that in addition to the two genes released from silencing (al-1 and qa-2) in the qde strains, the introduction of an additional transgene (al-2) did not trigger quelling of the native al-2 gene in the qde mutant background. Thus, in separated independent transgenic events, different genes were unable to be quelled in the qde mutants. Therefore, while multiple mechanisms for transgene-induced gene silencing in N. crassa may occur (8, 25), the qde mutants appear to be blocked in all of them.

The identification of the qde mutants constitutes the first necessary step in the identification of factors required for quelling in N. crassa. Because strong similarities exist between quelling and cosuppression in plants, we believe that the cloning the qde genes will be of extreme importance to resolving the puzzle of posttranscriptional gene silencing. Moreover, availability of qde mutants in N. crassa may be of help in both applied and basic research for the creation of transgenic strains able to overexpress a transgene.

Acknowledgments

We are deeply indebted with Dr. Gloria Coruzzi and Dr. Annette Pickford for the revision of the manuscript. We thank Monia Fiorini and Gianluca Azzalin for skillful technical assistance. This work was supported by grants from the European Economic Community, Biotech Programme, as part of the project of Technological Priority 1996–1999, and by the Institute Pasteur Fondazione Cenci Bolognetti.

ABBREVIATION

- RPA

RNase protection analysis

References

- 1.Flavell R B. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:3490–3496. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.9.3490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Finnegan J, McElroy D. Bio/Technology. 1994;12:883–888. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vaucheret H. C R Acad Sci Paris. 1993;316:1471–1483. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Park Y D, Papp I, Moscone E A, Iglesias V A, Vaucheret H, Matzke A J M, Matzke M A. Plant J. 1996;9:183–194. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.1996.09020183.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Napoli C, Lemieux C, Jorgensen R. Plant Cell. 1990;2:279–289. doi: 10.1105/tpc.2.4.279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.de Carvalho Niebel F, Frendo P, Montagu M V, Cornelissen M. Plant Cell. 1995;7:347–358. doi: 10.1105/tpc.7.3.347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Selker E U. Annu Rev Genet. 1990;24:579–613. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ge.24.120190.003051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Romano N, Macino G. Mol Microbiol. 1992;6:3343–3353. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1992.tb02202.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cogoni C, Ireland J T, Schumacher M, Schmidhauser T J, Selker E U, Macino G. EMBO J. 1996;15:3153–3163. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dehio C, Schell J. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:5538–5542. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.12.5538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Davis R H, DeSerres F J. Methods Enzymol. 1970;17:79–143. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Campbell J W, Enderlin C S, Selitrennikoff C P. Fungal Genet Newsl. 1994;41:20–21. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vollmer L J, Yanofsky C. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1986;83:4869–4873. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.13.4869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Orbach M J, Porro E B, Yanofsky C. Mol Cell Biol. 1986;6:2452–2461. doi: 10.1128/mcb.6.7.2452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schmidhauser T J, Lauter F, Schumacher M, Zhou W, Russo V E A, Yanofsky C. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:12060–12066. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Morelli G, Nelson M A, Ballario P, Macino G. Methods Enzymol. 1993;214:412–424. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(93)14085-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Maniatis S T, Fritsch E F, Sambrook J. Molecular Cloning: A Laboratory Manual. Plainview, New York: Cold Spring Harbor Lab. Press; 1982. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chary P, Hallewell R A, Natvig D O. J Biol Chem. 1990;265:18961–18967. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Baima S, Macino G, Morelli G. J Photochem Photobiol. 1991;11:107–115. doi: 10.1016/1011-1344(91)80253-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Meins F, Jr, Kunz C. In: Gene Inactivation and Homologous Recombination in Plants. Paszkowski J, editor. Dordrecht, The Netherlands: Kluwer; 1994. pp. 335–348. [Google Scholar]

- 21.van Blokland R, Van der Geest N, Mol J N M, Kooter J M. Plant J. 1994;6:861–877. [Google Scholar]

- 22.English J J, Mueller E, Baulcombe D C. Plant Cell. 1996;8:179–188. doi: 10.1105/tpc.8.2.179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Baulcombe D C. Plant Mol Biol. 1996;32:79–88. doi: 10.1007/BF00039378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lindbo J A, Silva-Rosales L, Proebsting W M, Dougherty W G. Plant Cell. 1993;5:1749–1759. doi: 10.1105/tpc.5.12.1749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pandit N N, Russo V E A. Mol Gen Genet. 1992;234:412–422. doi: 10.1007/BF00538700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]