The kinase domain (residues 1–331) of human tau-tubulin kinase 2 was expressed in insect cells, purified and crystallized. Diffraction data have been collected to 2.9 Å resolution.

Keywords: tau-tubulin kinase, tau protein

Abstract

Tau-tubulin kinase 2 (TTBK2) is a Ser/Thr kinase that putatively phosphorylates residues Ser208 and Ser210 (numbered according to a 441-residue human tau isoform) in tau protein. Functional analyses revealed that a recombinant kinase domain (residues 1–331) of human TTBK2 expressed in insect cells with a baculovirus overexpression system retains kinase activity for tau protein. The kinase domain of TTBK2 was crystallized using the hanging-drop vapour-diffusion method. The crystals belong to space group P212121, with unit-cell parameters a = 55.6, b = 113.7, c = 117.3 Å, α = β = γ = 90.0°. Diffraction data were collected to 2.9 Å resolution using synchrotron radiation at BL24XU of SPring-8.

1. Introduction

Tau-tubulin kinases (TTBK) have been found in various species such as human, mouse, zebrafish, Caenorhabditis elegans and Drosophila melanogaster (Manning et al., 2002 ▶; Tomizawa et al., 2001 ▶; Sato et al., 2006 ▶). They belong to the casein kinase 1 (CK1) group, which consists of the CK1, TTBK and vaccinia-related kinase families. Two isoforms, referred to as TTBK1 and TTBK2, have been identified in the TTBK family. In the CK1 group, the crystal structures of CK1-family enzymes such as CK1 from Schizosaccharomyces probe and CK1δ from rat testis have been solved (Xu et al., 1995 ▶; Longenecker et al., 1996 ▶). Human TTBK2 is the most probable candidate to phosphorylate the tau-protein residues Ser208 and Ser210 (numbering according to a 441-residue human tau isoform; Goedert et al., 1989 ▶), which are found in the paired helical filament-tau (PHF-tau) in the brain tissues of Alzheimer’s disease patients (Morishima-Kawashima et al., 1995 ▶; Hanger et al., 1998 ▶). Based on an automated computational analysis in the ‘kinome’ project (Manning et al., 2002 ▶), human TTBK2 (KinBase ID 16057) consists of 1244 amino acids and contains a kinase domain flanked by a putative noncatalytic long peptide region at the C-terminus. The alignment of the kinase domain of human TTBK2 and rat CK1δ (Graves et al., 1993 ▶) shows 38% identity (51% homology). We previously demonstrated that the bovine and mouse brain TTBK2s, which were observed as 36 kDa species in brain extracts, display kinase activities for tau protein and tubulin and that a recombinant kinase domain of mouse TTBK2 corresponding to residues 1–316 of human TTBK2 (98% identity) uniquely phosphorylates Ser208 and Ser210 in tau protein (Takahashi et al., 1995 ▶; Tomizawa et al., 2001 ▶). Rat TTBK2 has not only been identified in brain, but also various other tissues including heart, muscle, liver, thymus, spleen, lung, kidney, testis and ovary (Takahashi et al., 1995 ▶; Tomizawa et al., 2001 ▶). In contrast, a recent study of a neuron-specific human TTBK1 (KinBase ID; 16054) proposed that the enzyme phosphorylates Ser198, Ser199, Ser202 and Ser422 in tau protein, solely depending on its kinase domain (residues 38–319), which shares 84% identity with the corresponding region in human TTBK2 (Sato et al., 2006 ▶). These findings suggest that human TTBK2 is an orthologue of the bovine and mouse TTBK2s and that the 36 kDa N-terminal kinase domain of TTBK2 is essential for tau phosphorylation in the brain, although the detailed molecular mechanisms of the enzyme remain unclear, including a post-translational modification by limited lysosomal processing. Therefore, we attempted to express several kinds of TTBK2 kinase-domain constructs with various lengths and obtained a good-quality crystal from the TTBK2 (1–331) construct.

2. Construction and amplification of the recombinant baculovirus

The cDNA encoding TTBK2 (1–331) was amplified using a human cDNA library (Clontech) as the template, with a forward 5′-GCGCATATGAGTGGGGGAGGAGAGCAGCTGGA-3′ primer and a reverse 5′-GCGCGGCCGTCAGTGGTGGTGGTGGTGGTGAGCATTGGCAATTCCAATTGCAGCAGGGGT-3′ primer. The forward primer includes an NdeI restriction site, while the reverse primer includes an EagI restriction site and a hexahistidine-tag encoding region. The amplified DNA fragment was digested with EagI and blunted using a DNA Blunting Kit (Takara). The resultant cDNA fragment was digested with NdeI and subcloned into the NdeI/SmaI sites of a modified pBiEx-3 vector (Novagen) to attach the glutathione S-transferase (GST) moiety to the kinase domain at the N-terminus. The cDNA fragment was released by NcoI/NotI digestion from the vector and ligated into the NcoI/NotI sites of the baculovirus transfer vector pVL1392 (BD Biosciences). A PreScission Protease (GE Healthcare) cleavage site (LEVLFQGP) was introduced between GST and TTBK2 (1–331). After confirmation of the sequence, the resultant transfer vector was transfected into Sf9 cells grown in BaculoGold TNM FH medium (BD Biosciences) with BaculoGold Linearized Baculovirus DNA (BD Biosciences) and the virus was amplified according to the manufacturer’s protocol.

3. Expression and purification

Overexpression of TTBK2 (1–331) was carried out using High Five cells (at a cell density of 2.0 × 106) grown in IS-BAC medium (Irvine Scientific) at 300 K. The cells were inoculated with the recombinant baculovirus (at a multiplicity of infection of 5) and were incubated for 2 d. All of the following procedures were performed at 277 K. The cells were harvested by centrifugation at 5000g and resuspended in 20 mM Tris–HCl buffer pH 8.0 containing 5 mM MgCl2, 0.3 M NaCl, 5% glycerol, 0.05%(w/v) CHAPS and 1 mM DTT (buffer A). The cells were disrupted by sonication and were centrifuged at 12 000g for 30 min. The supernatant was loaded onto a Glutathione Sepharose 4B affinity-chromatography column (GE Healthcare) equilibrated with buffer A and the resin was washed with the buffer A. The GST tag was cleaved with PreScission Protease overnight on the resin and the target protein was eluted with the buffer A without DTT. The protein solution was subsequently loaded onto a Talon metal-affinity chromatography column (Clontech) equilibrated with buffer A. After washing the resin with buffer A, TTBK2 (1–331) was eluted with buffer A containing 300 mM imidazole. The resultant TTBK2 (1–331) protein contains three additional residues (Gly-Pro-His) at the N-terminal flanking region derived from the PreScission Protease recognition sequence and NdeI restriction site and a hexahistidine tag at the C-terminus. The protein solution containing the recombinant TTBK2 (1–331) was dialyzed against 50 mM Tris–HCl buffer pH 8.0 containing 5 mM MgCl2, 0.3 M NaCl, 5% glycerol, 0.05%(w/v) CHAPS and 5 mM DTT to remove the imidazole. The protein solution was applied onto a CIM-SO3-8 tube monolithic column (BIA Separations). The resin was washed with buffer A containing 0.3 M NaCl and the protein was subsequently eluted using a linear gradient of 0.3–0.6 M NaCl. The protein was further purified to homogeneity by gel-filtration chromatography on a Superdex 75HR column (10/300 GL; GE Healthcare) and concentrated to 3 mg ml−1 in 20 mM Tris–HCl pH 8.5 containing 5 mM MgCl2, 0.6 M NaCl, 5% glycerol, 0.05%(w/v) CHAPS, 5 mM DTT and 2 mM AMP-PNP (Sigma). The typical yield of protein was about 0.1 mg per litre of culture.

4. Crystallization and X-ray data collection

Initial crystallization attempts and optimization of the crystallization condition were performed at 293 K using the sitting-drop vapour-diffusion method by mixing 0.5 µl protein solution and 0.5 µl reservoir solution and equilibrating against 100 µl reservoir solution. The initial crystallization attempts were carried out manually using a 96-condition crystallization screen originally designed by Mitsubishi Chemical Corporation. Crystals were observed in 14 crystallization conditions and a crystallization condition containing 100 mM trisodium citrate pH 5.6 and 10% PEG 4000 was further optimized using Additive Screens (Hampton Research). Diffraction-quality crystals were finally obtained at 293 K in 100 mM trisodium citrate buffer pH 5.6 containing 14%(w/v) PEG 4000, 5 mM spermidine and 4%(v/v) acetonitrile. The crystallization drops were prepared by mixing 0.5 µl protein solution and an equal volume of reservoir solution and were equilibrated against 500 µl reservoir solution.

The crystals were transferred to reservoir solution containing 20%(w/v) PEG 400 as a cryoprotectant, picked up in a nylon loop and flash-cooled at 100 K in a nitrogen-gas stream. X-ray diffraction data sets were collected from a single crystal at SPring-8 beamline BL24XU using a Rigaku R-AXIS V imaging-plate area detector. The wavelength of the synchrotron radiation was 0.82656 Å and the the crystal-to-detector distance was 550 mm. A total of 135 frames were recorded with 1° oscillation and 90 s exposure time. The data were indexed, integrated and scaled using HKL-2000 (Otwinowski & Minor, 1997 ▶).

5. Results and discussion

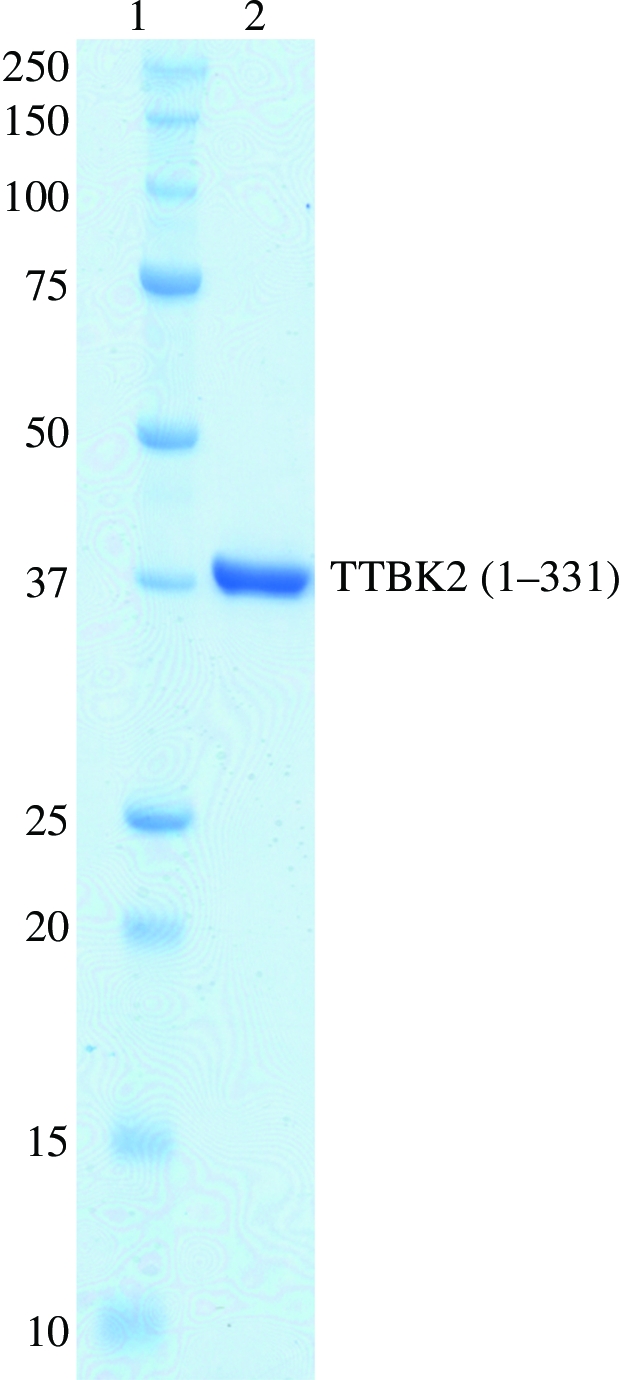

Human TTBK2 (1–331), which is identical to human TTBK2 (KinBase ID 16057), was heterologously expressed using a baculovirus overexpression system as a fusion protein with GST at the N-terminus and a hexahistidine tag at the C-terminus. After cleavage of the GST tag, the purified enzyme migrated as a single band with a molecular weight of 39 kDa on SDS–PAGE (Fig. 1 ▶), which is in good agreement with the calculated value of 38 621 Da. A gel-filtration experiment gave a molecular weight of 35 kDa, suggesting that TTBK2 (1–331) is a monomeric enzyme.

Figure 1.

Coomassie Brilliant Blue-stained SDS–PAGE gel (10–20% gradient) of the purified recombinant human TTBK2 (1–331). Lane 1, molecular-weight markers; lane 2, human TTBK2 (1–331).

As mentioned above, the bovine and mouse TTBK2 proteins phosphorylate Ser208 and Ser210 in tau protein (Takahashi et al., 1995 ▶; Tomizawa et al., 2001 ▶). To confirm the kinase activities of the expressed and purified recombinant TTBK2 (1–331) for tau protein, a functional analysis was carried out using the same procedure as described previously (Takahashi et al., 1995 ▶). The recombinant human TTBK2 (1–331) was functionally identical to the bovine and mouse TTBK2s (data not shown), suggesting that TTBK2 (1–331) contains the entire functional kinase domain that directly phosphorylates Ser208 and Ser210 in tau protein. The phosphorylation at Ser208 and Ser210 found in PHF-tau in the brains of Alzheimer’s patients is indeed caused by human TTBK2.

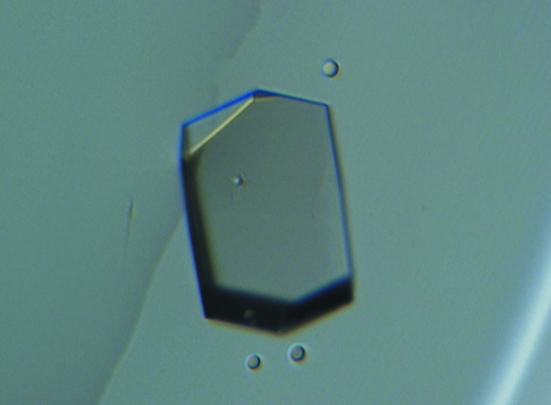

The crystals appeared reproducibly within 2 d and grew to average dimensions of 0.15 × 0.08 × 0.08 mm (Fig. 2 ▶). A complete data set was collected to 2.9 Å resolution. Data-processing statistics are shown in Table 1 ▶. The crystallographic asymmetric unit contains two molecules of TTBK2 (1–331), with a Matthews volume (V M; Matthews, 1968 ▶) of 2.5 Å3 Da−1 and a solvent content of 48%, which is in the range normally observed for protein crystals. A self-rotation function analysis calculated on data in the resolution range 15.0–4.0 Å using CNS (Brünger et al., 1998 ▶) indicated the presence of a twofold noncrystallographic symmetry axis. Further structural analysis is in progress.

Figure 2.

Crystal of TTBK2 (1–331). The dimensions of the crystals were approximately 0.15 × 0.08 × 0.08 mm.

Table 1. Data-collection statistics.

Values in parentheses are for the highest resolution shell.

| Space group | P212121 |

| Unit-cell parameters | |

| a (Å) | 55.6 |

| b (Å) | 113.7 |

| c (Å) | 117.3 |

| α = β = γ (°) | 90.0 |

| Resolution (Å) | 30.0–2.9 (3.00–2.90) |

| Unique reflections | 17074 |

| Redundancy | 5.3 (5.3) |

| Completeness (%) | 100.0 (100) |

| 〈I/σ(I)〉 | 27.6 (6.5) |

| Rsym† (%) | 10.2 (39.3) |

R

sym =

, where I(h) is the intensity of reflection h,

, where I(h) is the intensity of reflection h,  is the sum over all reflections and

is the sum over all reflections and  is the sum over i measurements of reflection h.

is the sum over i measurements of reflection h.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by a grant from the National Project on Protein Structural and Functional Analyses.

References

- Brünger, A. T., Adams, P. D., Clore, G. M., DeLano, W. L., Gros, P., Grosse-Kunstleve, R. W., Jiang, J.-S., Kuszewski, J., Nilges, M., Pannu, N. S., Read, R. J., Rice, L. M., Simonson, T. & Warren, G. L. (1998). Acta Cryst. D54, 905–921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goedert, M., Spillantini, M. G., Jakes, R., Rutherford, D. & Crowther, R. A. (1989). Neuron, 3, 519–526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graves, P. R., Haas, D. W., Hagedorn, C. H., DePaoli-Roach, A. A. & Roach, P. J. (1993). J. Biol. Chem.268, 6394–6401. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanger, D. P., Betts, J. C., Loviny, T. L., Blackstock, W. P. & Anderton, B. H. (1998). J. Neurochem.71, 2465–2476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Longenecker, K. L., Roach, P. J. & Hurley, T. D. (1996). J. Mol. Biol.257, 618–631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manning, G., Whyte, D. B., Martinez, R., Hunter, T. & Sudarsanam, S. (2002). Science, 298, 1912–1934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matthews, B. W. (1968). J. Mol. Biol.33, 491–497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morishima-Kawashima, M., Hasegawa, M., Takio, K., Suzuki, M., Yoshida, H., Titani, K. & Ihara, Y. (1995). J. Biol. Chem.270, 823–829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otwinowski, Z. & Minor, W. (1997). Methods Enzymol.276, 307–326. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Sato, S., Cerny, R. L., Buescher, J. L. & Ikezu, T. (2006). J. Neurochem.98, 1573–1584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi, M., Tomizawa, K., Sato, K., Ohtake, A. & Omori, A. (1995). FEBS Lett.372, 59–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomizawa, K., Omori, A., Ohtake, A., Sato, K. & Takahashi, M. (2001). FEBS Lett.492, 221–227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu, R. M., Carmel, G., Sweet, R. M., Kuret, J. & Cheng, X. (1995). EMBO J.14, 1015–1023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]