The crystal structure of the hypothetical protein PF0899 from P. furiosus has been determined to 1.85 Å resolution.

Keywords: structural genomics, SECSG, Pfu-871755, PF0899, high-throughput structure

Abstract

The hypothetical protein PF0899 is a 95-residue peptide from the hyperthermophilic archaeon Pyrococcus furiosus that represents a gene family with six members. P. furiosus ORF PF0899 has been cloned, expressed and crystallized and its structure has been determined by the Southeast Collaboratory for Structural Genomics (http://www.secsg.org). The structure was solved using the SCA2Structure pipeline from multiple data sets and has been refined to 1.85 Å against the highest resolution data set collected (a presumed gold derivative), with a crystallographic R factor of 21.0% and R free of 24.0%. The refined structure shows some structural similarity to a wedge-shaped domain observed in the structure of the major capsid protein from bacteriophage HK97, suggesting that PF0899 may be a structural protein.

1. Introduction

Open-reading frame ORF-0899 in the genome of the hyperthermophilic archaeon Pyrococcus furiosus encodes a 95-residue protein (PF0899) of unknown function with a molecular weight of 10 643 Da. Sequence analysis (Altschul et al., 1990 ▶) suggests that the protein encoded by ORF-0899 (PF0899) may represent a structure with a new protein fold. Orthologs of PF0899 are only found in Pyrococcus abyssi, P. horikoshii, P. woesei and Thermococcus kodakarensis and thus appear to be unique. Sequence analysis also showed that PF0899 contained three EXXE motifs, which could imply a role in iron transport since this motif has been observed in several iron-transport systems (Stearman et al., 1996 ▶; Wosten et al., 2000 ▶; Severance et al., 2004 ▶).

In order to shed light on the possible function of PF0899, the Southeast Collaboratory for Structural Genomics (SECSG; Adams et al., 2003 ▶) has chosen it for structural studies aimed at characterizing its fold and identifying its possible function. Here, we report the crystal structure of PF0899 at 1.85 Å resolution, the first structure reported for this gene family (Bateman et al., 2004 ▶).

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Expression and purification

The gene encoding PF0899 was amplified from P. furiosus chromosomal DNA by PCR, cloned into plasmid pET24dBam with an amino-terminal (MAHHHHHHGS-) affinity tag, expressed in the Escherichia coli host strain BL21(Star) DE3 containing the pRIL plasmid (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA, USA) and grown in ZYP-5052 auto-induction medium (Studier, 2005 ▶; Sugar et al., 2005 ▶). The recombinant protein was purified according to the high-throughput protocols established for P. furiosus protein production at SECSG (Adams et al., 2003 ▶; Sugar et al., 2005 ▶), which were modified to include an ion-exchange step (5 ml HiTrap Q-Sepharose column; GE Healthcare, Piscataway, NJ, USA) to give a three-step purification [immobilized metal-affinity/ion-exchange (HiTrap Q)/size-exclusion (G75) chromatography] protocol to further assure the purity of the protein. Protein identity and purity were assessed using electrospray ionization mass spectroscopy (University of Georgia Department of Chemistry) and SDS–PAGE. The expressed PF0899 protein including the His6 purification tag has a predicted molecular weight of 11 550 Da and a theoretical pI of 5.96. The purified PF0899 protein has a measured molecular weight of 11 552 Da and was concentrated to 25.8 mg ml−1 in 20 mM Tris buffer containing 300 mM NaCl, 2 mM dithiothreitol at pH 8.0 for crystallization trials.

2.2. Crystallization and data collection

Initial crystallization screening was carried out by sitting-drop vapor diffusion against the SECSG 384 condition crystallization screen (Liu, Tempel et al., 2005 ▶). All screens were set up using 200 nl drops containing equal volumes of protein and screening solution, which were dispensed using a Cartesian Honeybee (Genomic Solutions, Ann Arbor, MI, USA). Initial crystals were then optimized by the modified microbatch-under-oil method (Chayen et al., 1990 ▶) using an ORYX 1-6 crystallization robot (Douglas Instruments Ltd, East Garston, UK).

Diffraction-quality crystals were obtained using a precipitant solution containing 8%(w/v) polyethylene glycol 4000 (PEG 4000) in 100 mM sodium acetate buffer pH 3.9. PF0899 crystallized in the trigonal space group P3121, with unit-cell parameters a = 47.1, c = 83.9 Å. Assuming the presence of one molecule in the crystallographic asymmetric unit, the Matthews coefficient (Matthews, 1968 ▶) is calculated to be 2.52 Å3 Da−1, which corresponds to a calculated solvent content of 51%.

Derivative crystals were prepared by soaking the crystals overnight in the crystallization drop with a minute quantity (1–2 grains) of a heavy-atom salt, such as KI, K2PtCl4 or KAu(CN)2, added to the drop containing the crystals.

For data collection, crystals were harvested (Teng, 1990 ▶), briefly soaked in reservoir solution containing 20%(v/v) glycerol and flash-frozen in liquid nitrogen. All data sets were collected at cryogenic temperatures (100 K). During the course of the analysis, multiple X-ray diffraction data sets were collected (see Table 1 ▶) at both a synchrotron source (data sets 1–3) and at an in-house source (data sets 4–5). Synchrotron data were collected on beamlines 17ID (IMCA-CAT) and 22ID (SER-CAT), Advanced Photon Source (APS), Argonne National Laboratory using 1 Å X-rays. In-house data were collected using Cr Kα X-rays (λ = 2.2909 Å) produced using a Rigaku RUH3R rotating-anode generator equipped with Osmic (CMF 15-50Cr8) chromium optics. All data were indexed, integrated and scaled using HKL-2000 (Otwinowski & Minor, 1997 ▶), keeping separate Bijvoet pairs.

Table 1. Data-collection and processing statistics for PF0899.

Values in parentheses are for the highest resolution shell.

| Data set | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Crystal | Crystal 1 | Crystal 2 (1) | Crystal 2 (2) | Crystal 2 (3) | Crystal 3 | Crystal 4† |

| Soaking conditions | KI | K2PtCl4 + KI | K2PtCl4 + KI | K2PtCl4 + KI | K2PtCl4 + KI | KAu(CN)2 |

| X-ray source | APS 17ID | APS 17ID | APS 22ID | UGA Cr-2 | UGA Cr-2 | APS 22ID |

| Detector | ADSC Q210 | ADSC Q210 | MAR 225 | R-AXIS IV | R-AXIS IV | MAR 225 |

| Wavelength () | 1.0000 | 1.0000 | 1.0000 | 2.2909 | 2.2909 | 1.0000 |

| Crystal-to-detector distance (mm) | 220.00 | 200.00 | 180.00 | 96.80 | 96.60 | 180.00 |

| Oscillation width () | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| No. of images | 360 | 180 | 360 | 360 | 360 | 360 |

| Resolution () | 20.02.25 (2.352.25) | 20.02.07 (2.142.07) | 50.02.00 (2.072.00) | 12.02.50 (2.592.50) | 15.02.50 (2.592.50) | 20.01.85 (1.921.85) |

| Unit-cell parameters | ||||||

| a = b () | 47.1 | 47.0 | 47.1 | 47.1 | 47.0 | 47.1 |

| c () | 84.1 | 83.9 | 83.9 | 83.9 | 83.9 | 83.9 |

| Space group | P3221 | P3221 | P3221 | P3221 | P3221 | P3221 |

| Redundancy | 10.0 (8.3) | 10.2 (9.6) | 8.3 (4.0) | 10.8 (5.0) | 16.6 (6.2) | 9.9 (6.7) |

| Unique reflections | 5459 (639) | 6938 (661) | 7620 (681) | 3984 (395) | 3909 (330) | 9476 (840) |

| Completeness (%) | 99.2 (94.5) | 99.3 (95.2) | 98.6 (91.5) | 99.8 (98.3) | 98.1 (82.1) | 98.5 (92.4) |

| I/(I) | 25.7 (12.0) | 60.0 (13.2) | 53.8 (9.6) | 30.4 (4.4) | 36.6 (3.5) | 54.3 (6.1) |

| R sym ‡ (%) | 6.9 (19.7) | 4.8 (16.8) | 5.3 (14.6) | 10.1 (33.8) | 8.9 (39.1) | 4.4 (25.1) |

| No. of heavy-atom sites found | 0 | 1 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 1 |

This data set was used for the final refinement.

See Drenth (1999 ▶).

2.3. Structure solution and refinement

Numerous attempts to incorporate a high-occupancy heavy metal or anomalous scatterer into the crystal for phasing purposes were unsuccessful. When the initial KI-soaked crystal failed to produce an interpretable Patterson map, the remaining KI-soaked crystals from the well were soaked overnight in solutions containing K2PtCl4, harvested and flash-frozen as described above. The KAu(CN)2 derivative was prepared using a fresh batch of crystals with no KI added to the crystallization drop. A total of six data sets were collected from four crystals that were soaked in either KI, K2PtCl4 or KAu(CN)2, as detailed in Table 1 ▶. Although heavy-atom sites were located from the synchrotron data sets (data sets 2, 3 and 6; Table 1 ▶), the electron-density maps resulting from SAD (single-wavelength anomalous scattering) or MIRAS (multiple isomorphous replacement with anomalous scattering) phasing were not interpretable. The structure was finally solved when both in-house data sets (data sets 4–5; Table 1 ▶) were included in the MIRAS analysis. For the MIRAS analysis, the initial 2.25 Å data set (data set 1; Table 1 ▶) collected from the KI-soaked crystal served as the native data set. The MIRAS phases were then used for automated model building with ARP/wARP (Perrakis et al., 2001 ▶) using the 1.85 Å resolution KAu(CN)2 data set (data set 6; Table 1 ▶), since it was the data set with the highest resolution.

The structure was solved by the MIRAS technique using SOLVE/RESOLVE (Terwilliger, 2003 ▶) running within the automated SCA2Structure pipeline (Liu, Lin et al., 2005 ▶). Phases were generated from the data sets listed in Table 1 ▶, with data set 1 serving as the native data set. The model was adjusted manually, where needed, using XFIT (McRee, 1999 ▶), refined against the highest resolution data set (data set 6) using REFMAC v.5.1.24 (Murshudov, 1997 ▶) and validated using MOLPROBITY (Davis et al., 2004 ▶) and PROCHECK (Laskowski et al., 1993 ▶).

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Primary structure and dimerization of PF0899

The refined model consists of residues 2–95, 39 solvent molecules (identified by ARP/wARP) modeled as water and one unknown atom currently modeled as a low-occupancy dicyanoaurate ion. The N-terminal purification tag was not observed in the electron-density map and is assumed to be disordered. The refinement converged to give an R value of 21.0% (R free = 23.0%). The resulting 1.85 Å refined model, PDB entry 2pk8, has acceptable stereochemistry (see Table 2 ▶).

Table 2. Refinement statistics for PF0899.

Values in parentheses are for the outer shell (1.901.85).

| PDB code | 2pk8 |

| Data set | Crystal 4 |

| Model | |

| Total protein atoms | 783 |

| Total ligand atoms | 5 [Au(CN)2] |

| Total solvent atoms | 39 |

| Refinement | |

| Resolution limit () | 20.01.85 |

| R free | 0.242 (0.306) |

| R.m.s.d. from ideality | |

| Bond lengths () | 0.012 |

| Bond angles () | 1.271 |

| Average B factor (2) | 13.1 |

| Ramachandran plot (%) | |

| Most favored | 95.00 |

| Additionally allowed | 5.00 |

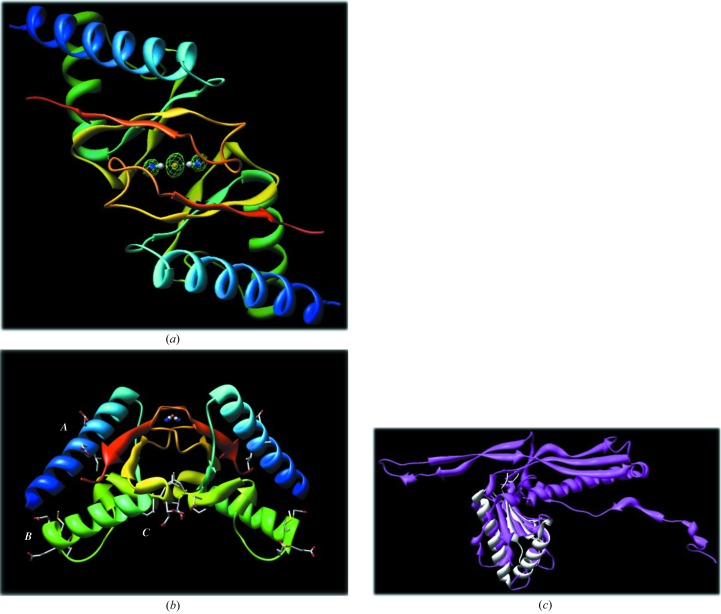

PF0899 is a wedge-shaped molecule with dimensions of 17 × 22 × 46 Å. The protein fold (Fig. 1 ▶ a) is typical of α+β proteins, consisting of a mixture of five β-strands (↑β1–↑β2–↓β3–↓β4–↑β5) and three α-helices (α1, α2 and α3′; ′ denotes a 310-helix). The perimeter of the wedge is defined by helices αA and αB and strands β1, β4 and β5. A long 9:11β hairpin (Sibanda et al., 1989 ▶; residues 78–87) extends from the wedge and interacts with a similar segment (residues 78–87) from a twofold symmetry-related molecule, forming a loose dimer (interface area 752 Å2) stabilized by eight hydrogen bonds and one presumed bridging dicyanoaurate ion (see Fig. 2 ▶ a). The dicyanoaurate ion spans the crystallographic twofold axis (the Au atom occupies the twofold axis) and is hydrogen bonded to Gly82 (N—N1 distance 2.87 Å) and Val84 (O—N1 distance 2.69 Å) of each molecule of the dimer. Interestingly, the bridging dicyanoaurate is not required for dimer formation since crystals from setups not containing dicyanoaurate gave isomorphous diffraction patterns indicative of a similar crystal packing arrangement. Thus, the PF0899 dimer may represent a biologically active form of the protein. However, further studies need to be performed to confirm this suggestion.

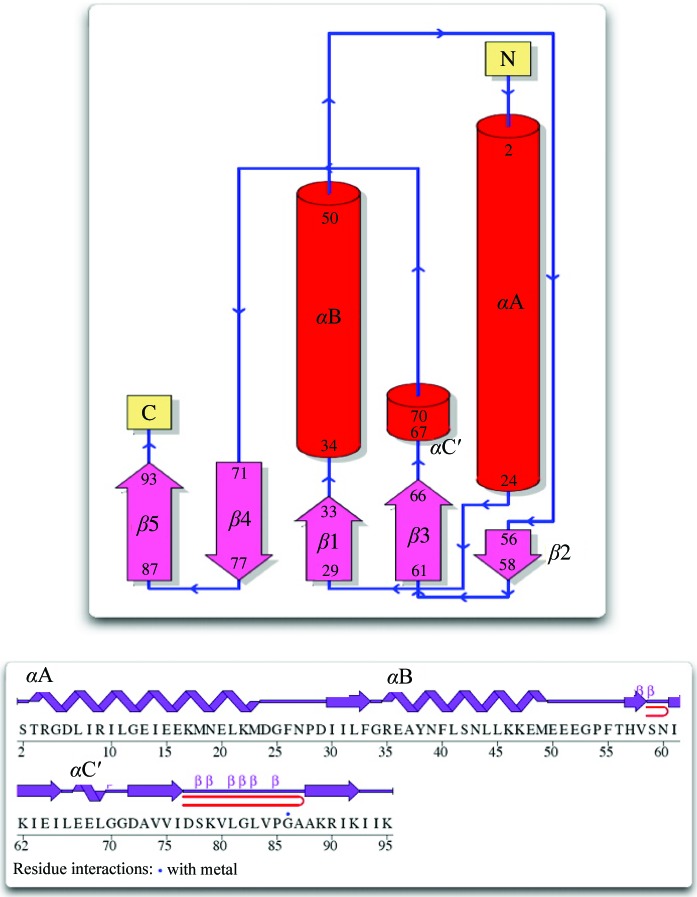

Figure 1.

A topology diagram of the PF0899 model showing features of its secondary structure. Cylinders (and coils) indicate helices; arrows indicate β-strands. Helices identified by a prime are 310-helices. The two β-hairpins in the structure are indicated as red hairpins (diagram adapted from PDBSum; Laskowski et al., 2005 ▶; http://www.ebi.ac.uk/thornton-srv/databases/pdbsum).

Figure 2.

(a) A ribbon diagram of the PF0899 dimer viewed down its twofold axis. The molecules are colored blue to red according to their sequence. The bridging dicyanoaurate ion with the Au atom sitting on the twofold axis is highlighted in the center. The dicyanoaurate is indicated as distinct atoms (Au, orange; C, gray; N, blue). Electron density (F o − F c OMIT map) for the dicyanoaurate ion is also shown contoured at 3σ. Images were generated with CHIMERA (Pettersen et al., 2004 ▶; http://www.cgl.ucsf.edu/chimera). (b) A ribbon diagram of the PF0899 dimer viewed perpendicular to its twofold axis. The positions of the three EXXE motifs are highlighted and labeled A, B and C. Note the large site C binding pocket located at the dimer interface. The color scheme is the same as in Fig. 2 ▶(a). Images were generated with CHIMERA. (c) Diagram showing the alignment and overlap of 1ohg and 2pk8.

3.2. Overall structure

A DALI search (Holm & Sander, 1993 ▶) of the PDB found that PF0899 was most similar to PDB entry 1ohg, the major capsid protein (gp5, head protein) of dsDNA bacteriophage Hk97 (Helgstrand et al., 2003 ▶). The two structures can be superimposed (86 residues, 9% sequence identity) to give a root-mean-square deviation (Cα) of 2.2 Å, suggesting that PF0899 may be a structural protein (see Table 3 ▶ and Fig. 2 ▶ c). Again, further studies are needed to confirm a structural role for the protein.

Table 3. Summary of similar proteins from the DALI search.

Finally, although PF0899 contains three EXXE putative metal-binding motifs, no bound metal other than dicyanoaurate anion was observed in the crystal structure. The three EXXE motifs, or sites, can be described as follows (see Fig. 2 ▶ b). Site A (residues 13–16) is located in the center segment of helix αA in an environment somewhat similar to that observed for the iron-binding site of the class Ib ribonucleotide reductase R2 protein from Corynebacterium ammoniagenes (Hogbom et al., 2002 ▶). Site B (residues 48–51) is highly solvent-exposed and is located at the C-terminal end of αB, corresponding to one of the corners of the protein wedge. Site C (residues 64–67) is located at the dimer interface in the loop connecting strand β3 to αC′. The two site C motifs at the dimer interface form a 383 Å2 pocket with their twofold-related counterparts.

3.3. Structure comparison and functional prediction

In summary, although PF0899 is a protein unique to Pyrococcus/Thermococcus species, its structure, in part, is similar to a bacteriophage major capsid protein. The crystal structure also suggests that the protein may function as a homodimer. In addition, the structure does not rule out a metal-binding role for the protein since the EXXE putative metal-binding motifs are located in environments that could allow metal binding.

Supplementary Material

PDB reference: PF0899, 2pk8, r2pk8sf

Acknowledgments

The work described here was funded in part by the following organizations: the National Institutes of Health (GM62407, GM60329), the Department of Energy (FG05-95ER20175), IBM Life Sciences, the Georgia Research Alliance and the University of Georgia Research Foundation. Data were collected at 22ID, Southeast Regional Collaborative Access Team (SER-CAT; http://www.ser-cat.org/), Advanced Photon Source, Argonne National Laboratory. Use of the Advanced Photon Source was supported by the US Department of Energy, Office of Science, Office of Basic Energy Sciences under Contract No. W-31-109-Eng-38.

References

- Adams, M. W., Dailey, H. A., DeLucas, L. J., Luo, M., Prestegard, J. H., Rose, J. P. & Wang, B.-C. (2003). Acc. Chem. Res. 36, 191–198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altschul, S. F., Gish, W., Miller, W., Myers, E. W. & Lipman, D. J. (1990). J. Mol. Biol. 215, 403–410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bateman, A., Coin, L., Durbin, R., Finn, R. D., Hollich, V., Griffiths-Jones, S., Khanna, A., Marshall, M., Moxon, S., Sonnhammer, E. L., Studholme, D. J., Yeats, C. & Eddy, S. R. (2004). Nucleic Acids Res. 32, D138–D141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chayen, N. E., Shaw Stewart, P. D., Maeder, D. L. & Blow, D. M. (1990). J. Appl. Cryst. 23, 297–302. [Google Scholar]

- Davis, I. W., Murray, L. W., Richardson, J. S. & Richardson, D. C. (2004). Nucleic Acids Res. 32, W615–W619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drenth, J. (1999). Principles of Protein X-ray Crystallography, 2nd ed. New York: Springer.

- Helgstrand, C., Wikoff, W. R., Duda, R. L., Hendrix, R. W., Johnson, J. E. & Liljas, L. (2003). J. Mol. Biol. 334, 885–899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hogbom, M., Huque, Y., Sjoberg, B. M. & Nordlund, P. (2002). Biochemistry, 41, 1381–1389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holm, L. & Sander, C. (1993). J. Mol. Biol. 233, 123–138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laskowski, R. A., Chistyakov, V. V. & Thornton, J. M. (2005). Nucleic Acids Res. 33, D266–D268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laskowski, R. A., MacArthur, M. W., Moss, D. S. & Thornton, J. M. (1993). J. Appl. Cryst. 26, 283–291. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Z.-J., Lin, D., Tempel, W., Praissman, J. L., Rose, J. P. & Wang, B.-C. (2005). Acta Cryst. D61, 520–527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Z.-J., Tempel, W. et al. (2005). Acta Cryst. D61, 679–684. [Google Scholar]

- McRee, D. E. (1999). J. Struct. Biol. 125, 156–165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matthews, B. W. (1968). J. Mol. Biol. 33, 491–497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murshudov, G. N. (1997). Acta Cryst. D53, 240–255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otwinowski, Z. & Minor, W. (1997). Methods Enzymol. 276, 307–326. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Perrakis, A., Harkiolaki, M., Wilson, K. S. & Lamzin, V. S. (2001). Acta Cryst. D57, 1445–1450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pettersen, E. F., Goddard, T. D., Huang, C. C., Couch, G. S., Greenblatt, D. M., Meng, E. C. & Ferrin, T. E. (2004). J. Comput. Chem. 25, 1605–1612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Severance, S., Chakraborty, S. & Kosman, D. J. (2004). Biochem. J. 380, 487–496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sibanda, B. L., Blundell, T. L. & Thornton, J. M. (1989). J. Mol. Biol. 206, 759–777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stearman, R., Yuan, D. S., Yamaguchi-Iwai, Y., Klausner, R. D. & Dancis, A. (1996). Science, 271, 1552–1557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Studier, F. W. (2005). Protein Expr. Purif. 41, 207–234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sugar, F. J., Jenney, F. E. Jr, Poole, F. L. II, Brereton, P. S., Izumi, M., Shah, C. & Adams, M. W. (2005). J. Struct. Funct. Genomics, 6, 149–158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teng, T.-Y. (1990). J. Appl. Cryst. 23, 387–391. [Google Scholar]

- Terwilliger, T. C. (2003). Methods Enzymol. 374, 22–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wosten, M. M., Kox, L. F., Chamnongpol, S., Soncini, F. C. & Groisman, E. A. (2000). Cell, 103, 113–125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

PDB reference: PF0899, 2pk8, r2pk8sf