Recombinant PRRSV 3CL protease was crystallized and the crystals diffracted to 2.1 Å resolution.

Keywords: porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome; PRRSV; nsp4 (3C-like serine protease, main proteinase); chemical cross-linking

Abstract

3CL protease, a viral chymotrypsin-like proteolytic enzyme, plays a pivotal role in the transcription and replication machinery of many RNA viruses, including porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus (PRRSV). In this study, the full-length 3CL protease from PRRSV was cloned and overexpressed in Escherichia coli. Crystallization experiments yielded crystals that diffracted to 2.1 Å resolution and belong to space group C2, with unit-cell parameters a = 112.31, b = 48.34, c = 42.88 Å, β = 109.83°. The Matthews coefficient and the solvent content were calculated to be 2.49 Å3 Da−1 and 50.61%, respectively, for one molecule in the asymmetric unit.

1. Introduction

Porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome (PRRS), also called ‘blue ear’ disease, is manifested clinically by severe reproductive failure in sows and respiratory distress in pigs of various ages (Paton et al., 1991 ▶). This disease has become endemic in many countries and has caused great economic losses in the swine industry worldwide (Tian et al., 2007 ▶; Dea et al., 2000 ▶). Viruses of the order Nidovirales regulate their genome expression by synthesizing two multidomain precursor polyproteins that are subsequently cleaved into functional viral proteins mainly by the 3CL protease (den Boon et al., 1991 ▶; Birtley et al., 2005 ▶; Snijder et al., 1996 ▶; van Aken et al., 2006 ▶). The functional importance of the 3CL protease in the viral life cycle makes it an attractive target for the development of small-molecule drugs. Several crystal structures of 3CL protease have been solved, e.g. those of human coronavirus 229E (hCoV-229E; Anand et al., 2003 ▶), severe acute respiratory syndrome-related coronavirus (SARS-CoV; Yang et al., 2003 ▶), equine arteritis virus (EAV; Barrette-Ng et al., 2002 ▶) and transmissible gastroenteritis virus (TGEV; Anand et al., 2002 ▶). Despite the common structure of the 3CL proteases determined to date, consisting of two β-barrels and a unique C-terminal domain, there are many significant differences between them, especially in the linker between the C-terminal domain and the C-terminal β-barrel (Barrette-Ng et al., 2002 ▶).

We have initiated a study aimed at determining the three-dimensional structure of 3CL proteases in order to understand their function from a structural perspective and to provide a platform for the screening of new drugs. Here, we report the crystallization of the 3CL protease from PRRSV and its preliminary crystallographic analysis.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Cloning and expression

Viral genomic RNA was extracted from marc-145 cell cultures which had been inoculated with the PRRSV isolate (gi|119068009) using the RNeasy Plus Mini Kit (Qiagen, Germany). The reverse transcription (RT) was undertaken using the primers 3CL-F1 (5′-CACATGCTTGCTGGTGTTTA-3′) and 3CL-R1 (5′-GCCACGGTATCGGCAAAAGC-3′). After the single-tube RT reaction, 1 µl of PCR product was used as a template to amplify the coding sequence (CDS) of PRRSV 3CL protease with specific primers 3CL-F2 (5′-CCCGGGCGCTTTCAGAACTCAAAA-3′) and 3CL-R2 (5′-CCGCTCGAGTTATTCCAGTTCGGGTTTGGC-3′). The amplified DNA fragment encoding the PRRSV 3CL protease was inserted into the GST-fusion expression vector pGEX-6p-1 (GE Healthcare) with SmaI/XhoI sites (introduced by PCR primers). The resultant positive clone, designated pGEX::3CL, was confirmed by double-enzyme digestion and verified by direct DNA sequencing.

For protein expression, the plasmid was transformed into Escherichia coli strain BL21 (DE3) competent cells and the single colony was inoculated into Luria–Bertani (LB) medium with 50 mg l−1 ampicillin (Sigma, USA) at 310 K for overnight growth. The overnight culture was then transferred into a flask containing 2 l fresh LB medium. When the culture density (OD600) reached 0.8, the culture was induced with 0.2 mM isopropyl β-d-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG; Sigma, USA) and kept for ∼3.5 h at 289 K until collection of the bacteria.

2.2. Protein purification

The harvested culture was centrifuged at 5000 rev min−1 for 12 min at 277 K and the pellet was resuspended in chilled PBS (140 mM NaCl, 2.7 mM KCl, 10 mM Na2HPO4, 1.8 mM KH2PO4 pH 7.3) and homogenized by sonication. The lysate was centrifuged at 16 000 rev min−1 for 20 min at 277 K and subsequently filtered through a 0.22 µm membrane for clarification. The supernatant was then loaded onto a glutathione-Sepharose 4B column (GE Healthcare). The protein-loaded column was washed with ten bed volumes of PBS and ten bed volumes of cleavage buffer (50 mM Tris–HCl, 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM DTT pH 7.5). To obtain GST-free protein, GST-3C rhinovirus protease (kindly provided by Drs J. Heath and K. Hudson) was added to the resin at a concentration of 160 units per millilitre of bed volume. After the mixture had been incubated with gentle agitation overnight at 277 K, the target protein was eluted with 10 ml cleavage buffer (Fig. 1 ▶).

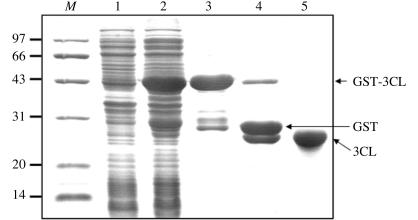

Figure 1.

Purification of PRRSV 3CL protease. Lane M, protein molecular-weight markers (kDa); lane 1, uninduced bacteria; lane 2, bacteria induced with 0.2 mM IPTG at 289 K; lane 3, GST-fused 3CL protease purified using GST beads; lane 4, after digestion with rhinovirus 3C protease; lane 5, GST-removed 3CL protease.

The harvested protein was then concentrated to a suitable concentration by ultrafiltration (10 kDa cutoff) and loaded onto a Superdex 75 column (GE Healthcare) with an Akta Purifier System (GE Healthcare) at a flow rate of 0.2 ml min−1. The fractions containing the protein peak were collected and analyzed using 15% SDS–PAGE. For crystallization, the purified protein was concentrated to approximately 20 mg ml−1 and the buffer was exchanged to 10 mM Tris–HCl, 10 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM DTT pH 7.5.

2.3. Chemical cross-linking analysis

The purified 3CL protease after gel filtration was dialyzed against cross-linking buffer (50 mM HEPES pH 8.3, 100 mM NaCl) and concentrated to approximately 5 mg ml−1 by ultrafiltration (10 kDa cutoff). Subsequently, various concentrations (0, 0.5, 1.0, 2.0 mM) of bis-succinimidylsuccinate (EGS; Pierce) were added to the protein sample; the GST protein was used as a positive control (Ma et al., 2005 ▶). The reactions were incubated for 1 h at room temperature and quenched with 50 mM glycine. Finally, the cross-linked samples were analyzed by 15% SDS–PAGE (Fig. 2 ▶).

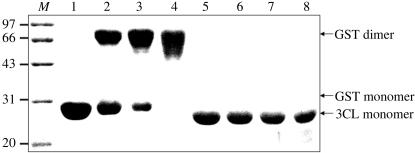

Figure 2.

Chemical cross-linking of PRRSV 3CL protease. Cross-linked products were separated in 15% SDS–PAGE followed by Coomassie Brilliant Blue staining. Protein molecular-weight markers (lane M) are shown in kDa. Lanes 1–4 (the GST positive control) and the lanes 5–8 (the 3CL protease) contain increasing concentrations of EGS (0, 0.5, 1.0 and 2.0 mM, respectively). Bands corresponding to monomers and dimers are indicated.

2.4. Crystallization and X-ray diffraction analysis

Crystallization trials were performed with Crystal Screens I and II (Hampton Research) at 291 K using the hanging-drop vapour-diffusion method. 1 µl protein solution (at a concentration of 5, 10 or 15 mg ml−1) was mixed with 1 µl reservoir solution and equilibrated against 200 µl reservoir solution.

X-ray diffraction data were collected in-house on a Rigaku MicroMax007 rotating-anode X-ray generator operated at 40 kV and 20 mA (Cu Kα; λ = 1.5418 Å) equipped with an R-AXIS VII** image-plate detector. The crystal was mounted in a nylon loop and flash-cooled in a cold nitrogen-gas stream at 100 K using an Oxford Cryosystem. The cryoprotectant solution contained 15% glycerol and 50% reservoir solution. Data were indexed, integrated and scaled using DENZO and SCALEPACK as implemented in HKL-2000 (Otwinowski & Minor, 1997 ▶).

3. Results and discussion

PRRSV 3CL protease was partially generated in soluble form when expressed in E. coli. Induction at 289 K proved to increase the yield of soluble GST-3CL protease (data not shown). After removing the N-terminal GST tag of the fusion protein, purified 3CL protease was obtained with nine additional residues (GPLGSPEFP) at the N-terminus. With these nine extra residues, the protein product is 213 amino acids in length, corresponding to a molecular weight of about 22.0 kDa. 15% SDS–PAGE showed that the peak for the expressed protein occurs at the position expected for its size (Fig. 1 ▶). The recombinant PRRSV 3CL protease was also confirmed by peptide mass fingerprinting (data not shown). A subsequent chemical cross-linking experiment clearly indicated that the PRRSV 3CL protease was in a monomeric form (Fig. 2 ▶), in comparison to the dimeric form of GST.

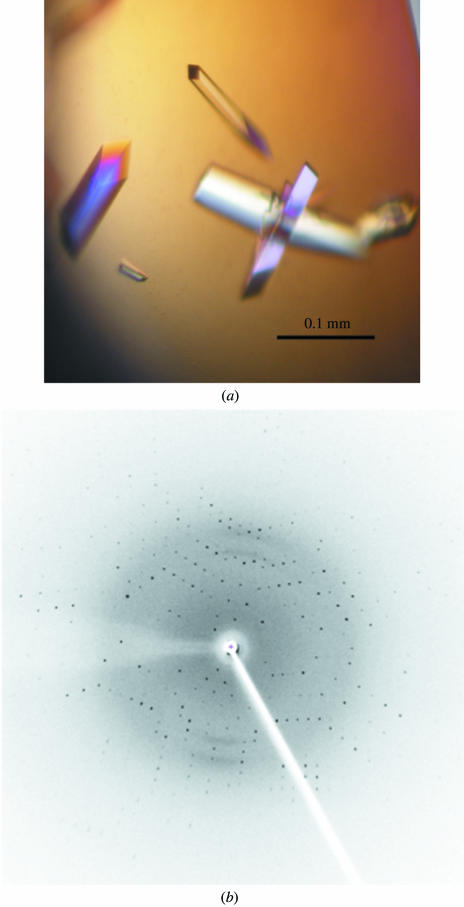

Crystallization of 3CL protease proved to be easy under several conditions, indicating its stable tightly packed structure. A crystal grown (within 8 d; Fig. 3 ▶ a) from a condition consisting of 0.1 M sodium cacodylate trihydrate pH 6.5, 1.4 M sodium acetate trihydrate diffracted X-rays to 2.1 Å (Fig. 3 ▶ b) and belongs to the monoclinic space group C2, with unit-cell parameters a = 112.31, b = 48.34, c = 42.88 Å, β = 109.83°. Data-collection statistics are given in Table 1 ▶. There is only one molecule per asymmetric unit. The Matthews coefficient and the solvent content were calculated to be 2.49 Å3 Da−1 and 50.61% (Matthews, 1968 ▶), respectively.

Figure 3.

Crystallographic characterization of PRRSV 3CL protease. (a) Representative crystals of PRRSV 3CL protease. (b) X-ray diffraction pattern of PRRSV 3CL protease. The size of the crystals is typically about 25 × 25 × 100 µm.

Table 1. Data-collection statistics.

| Wavelength (Å) | 1.5418 |

| Space group | C2 |

| Unit-cell parameters (Å, °) | a = 112.31, b = 48.34, c = 42.88, β = 109.83 |

| Resolution (Å) | 39.09–2.10 (2.18–2.10) |

| No. of observed reflections | 45577 |

| No. of unique reflections | 12350 |

| Average redundancy | 3.69 (3.68) |

| Completeness (%) | 96.6 (94.8) |

| Rmerge† | 0.054 (0.185) |

| Average I/σ(I) | 15.2 (5.9) |

| Reduced χ2 | 1.01 (1.06) |

| Wilson B factor (Å2) | 26.1 |

R

merge =

, where Ii is the intensity of an individual measurement of a reflection and 〈I〉 is the mean value for all equivalent measurements of this reflection.

, where Ii is the intensity of an individual measurement of a reflection and 〈I〉 is the mean value for all equivalent measurements of this reflection.

Initial molecular-replacement calculations were performed using the program AMoRe (Navaza, 1994 ▶) using the crystal structure of equine arteritis virus (EAV) 3CL protease as a search model (PDB code 1mbm), but no distinct peaks were obtained. This suggests that there are many differences in the three-dimensional structures of the 3CL proteases from PRRSV and EAV, despite their significant sequence homology (36% identity at the amino-acid level).

Acknowledgments

This work was completed in the laboratory of Professor George F. Gao at the Institute of Microbiology, Chinese Academy of Sciences (IMCAS) and was supported by the National Basic Research Program (Project 973) of China (2005CB523001) and the National Key Technologies R&D Program (2006BAD06A04 and 2006BAD06A12).

References

- Aken, D. van, Benckhuijsen, W. E., Drijfhout, J. W., Wassenaar, A. L., Gorbalenya, A. E. & Snijder, E. J. (2006). Virus Res.120, 97–106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anand, K., Palm, G. J., Mesters, J. R., Siddell, S. G., Ziebuhr, J. & Hilgenfeld, R. (2002). EMBO J.21, 3213–3224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anand, K., Ziebuhr, J., Wadhwani, P., Mesters, J. R. & Hilgenfeld, R. (2003). Science, 300, 1763–1767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrette-Ng, I. H., Ng, K. K., Mark, B. L., Van Aken, D., Cherney, M. M., Garen, C., Kolodenko, Y., Gorbalenya, A. E., Snijder, E. J. & James, M. N. (2002). J. Biol. Chem.277, 39960–39966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birtley, J. R., Knox, S. R., Jaulent, A. M., Brick, P., Leatherbarrow, R. J. & Curry, S. (2005). J. Biol. Chem.280, 11520–11527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boon, J. A. den, Snijder, E. J., Chirnside, E. D., de Vries, A. A., Horzinek, M. C. & Spaan, W. J. (1991). J. Virol.65, 2910–2920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dea, S., Gagnon, C. A., Mardassi, H., Pirzadeh, B. & Rogan, D. (2000). Arch. Virol.145, 659–688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma, G., Feng, Y., Gao, F., Wang, J., Liu, C. & Li, Y. (2005). Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun.337, 1301–1307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matthews, B. W. (1968). J. Mol. Biol.33, 491–497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Navaza, J. (1994). Acta Cryst. A50, 157–163. [Google Scholar]

- Otwinowski, Z. & Minor, W. (1997). Methods Enzymol.276, 307–326. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Paton, D. J., Brown, I. H., Edwards, S. & Wensvoort, G. (1991). Vet. Rec.128, 617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snijder, E. J., Wassenaar, A. L., van Dinten, L. C., Spaan, W. J. & Gorbalenya, A. E. (1996). J. Biol. Chem.271, 4864–4871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tian, K. et al. (2007). PLoS ONE, 2, e526. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, H., Yang, M., Ding, Y., Liu, Y., Lou, Z., Zhou, Z., Sun, L., Mo, L., Ye, S., Pang, H., Gao, G. F., Anand, K., Bartlam, M., Hilgenfeld, R. & Rao, Z. (2003). Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 100, 13190–13195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]