Abstract

The extracellular signal–regulated kinases 1 and 2 (ERK1/2) are phosphorylated after inhalation of asbestos. The effect of blocking this signaling pathway in lung epithelium is unclear. Asbestos-exposed transgenic mice expressing a dominant-negative mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase-1 (dnMEK1) (i.e., the upstream kinase necessary for phosphorylation of ERK1/2) targeted to lung epithelium exhibited morphologic and molecular changes in lung. Transgene-positive (Tg+) (i.e., dnMEK1) and transgene-negative (Tg−) littermates were exposed to crocidolite asbestos for 2, 4, 9, and 32 days or maintained in clean air (sham controls). Distal bronchiolar epithelium was isolated using laser capture microdissection and mRNA analyzed for molecular markers of proliferation and Clara cell secretory protein (CCSP). Lungs and bronchoalveolar lavage fluids were analyzed for inflammatory and proliferative changes and molecular markers of fibrogenesis. Distal bronchiolar epithelium of asbestos-exposed wild-type mice showed increased expression of c-fos at 2 days. Elevated mRNA levels of histone H3 and numbers of Ki-67–labeled proliferating bronchiolar epithelial cells were decreased at 4 days in asbestos-exposed Tg+ mice. At 32 days, distal bronchioles normally composed of Clara cells in asbestos-exposed Tg+ mouse lungs exhibited nonreplicating ciliated and mucin-secreting cells as well as decreased mRNA levels of CCSP. Gene expression (procollagen 3-a-1, procollagen 1-a-1, and IL-6) linked to fibrogenesis was also increased in lung homogenates of asbestos-exposed Tg− mice, but reduced in asbestos-exposed Tg+ mice. These results suggest a critical role of MEK1 signaling in epithelial cell proliferation and lung remodeling after toxic injury.

Keywords: mitogen-activated protein kinases, asbestosis, fibrosis, Clara cell, cell signaling

CLINICAL RELEVANCE

The extracellular signal–regulated kinases (ERK1/2) have been implicated in acute lung injury by many toxic pollutants and in inflammatory lung diseases, including asthma and pulmonary fibrosis.

Exposure to asbestos fibers is a well-documented risk factor for the development of malignant mesothelioma, lung cancer, and pulmonary fibrosis (asbestosis), a fibroproliferative disease occurring after epithelial cell injury and remodeling (1). Inhaled asbestos fibers initially accumulate in distal bronchioles and alveolar duct regions, sites associated with phosphorylation of the major mammalian, extracellular signal–regulated kinases (ERK)1 and ERK2 (2, 3). ERK1 and 2 proteins compete for phosphorylation by the upstream mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase (MEK1) protein (4) to then phosphorylate a number of intracellular substrates and increase expression of genes encoding proteins such as c-Fos (5) that comprise the activator protein-1 (AP-1) transcription factor. Although ERKs have been intensely studied in vitro and in tumor cells in vivo, only a few studies have examined the functional roles of ERK1/2 in differentiation and damage to normal tissue (6, 7).

Signaling cascades generated in the distal bronchiolar epithelium may be important in early injury by or repair from asbestos. Here we first used laser capture microdissection (LCM) and the quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (QRT-PCR) to profile changes in gene expression in distal bronchioles of asbestos-exposed C57/BL6 wild-type mice. We examined mRNA levels of the early response AP-1 protooncogenes, c-jun and c-fos, proliferation-associated genes (histone H3, cyclin D1) and MnSOD (SOD2), an antioxidant enzyme increased after exposure to inflammatory and fibrogenic minerals (8). We then tested the hypothesis that the MEK1/ERK1/2 pathway mediates proliferation and differentiation of bronchiolar epithelium after inhalation of asbestos. To achieve this goal, mice containing a dominant-negative mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase-1 (dnMEK1) transgene (Tg+) targeted to bronchiolar epithelium were created using the CC10 promoter (9). Our results show that modifying MEK1 signaling in distal bronchiolar epithelial cells decreases histone 3 expression and mitogenesis in response to inhaled asbestos fibers. Moreover, differentiation from a predominantly Clara cell population to ciliated and mucin-producing cells is observed in Tg+ mice exposed to asbestos. We also report that molecular markers of fibrogenesis (i.e., procollagens and IL-6 gene expression) are increased in lungs of asbestos-exposed Tg− mice, but not in lungs of Tg+ mice. This study is the first to demonstrate a causal role of the MEK1 cascade in epithelial cell replication and remodeling after lung injury by a pathogenic fiber in vivo.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Creation of Transgenic dnMEK1 (Tg+) Mice

These mice, created using the CC10 promoter (9) and a dnMEK1 construct (10), have been characterized previously (7) (see online supplement).

Inhalation Exposures to Asbestos

In duplicate experiments, dnMEK1 transgene positive mice (Tg+) and transgene-negative (Tg−) littermates (n = 3-6/group/time/individual experiments performed in duplicate) were exposed to clean air (sham controls) or crocidolite asbestos (NIEHS reference standard at a concentration of approximately 7 mg asbestos/m3 air for 2, 4, 9, and 32 d) (11). These time points represent peak times of early response protooncogene induction (2 d), distal bronchiolar epithelial cell proliferation (4 d), inflammation and expression of mucin-positive cells (9 d), and fibrogenesis (32 d) in previous inhalation experiments (11, 12).

Isolation of Lungs, Histopathology, and Bronchoalveolar Lavage Procedures

These techniques have been characterized previously (11, 12) (see online supplement).

Ki-67 Immunoperoxidase Staining

Paraffin-embedded mouse lung tissue sections were stained using an antibody to Ki-67 and numbers of positively stained cells in distal bronchiolar epithelium evaluated and quantitated as described previously (12).

LCM

LCM was performed to selectively capture distal bronchioles (restricted to ⩽ 800 μm in perimeter at ×400 magnification without a smooth muscle peribronchiolar lining) as described previously (11). The captured epithelial cells were extracted for 30 minutes at 42°C in an extraction buffer (Arcturus Engineering, Mountain View, CA) and stored at −80°C until further processing.

Quantitative Real-Time PCR

Total RNA was extracted from microdissected epithelium or lung tissue using a PicoPure RNA isolation kit (Arcturus) as described in the online supplement. Probes and primers for all genes (see Table E1 in the online supplement), including histone H3, a molecular marker of cell proliferation (13), c-fos, c-jun, MnSOD, and cyclin D1, were used at concentrations of 200 nM and 900 nM, respectively.

Reverse Transcription PCR

RNA was isolated and reverse transcription performed as described above and in the online supplement. Forward and reverse primers for IL-6, TNFα, procollagen 1-a-1, and procollagen 3-a-1 are described in Table E1.

Multifluorescence Studies Using Confocal Scanning Laser Microscopy

Lung sections were cut in a cryostat, placed onto glass slides, and stored at −80°C until use. Sections then were fixed in fresh 3% paraformaldehyde for immunohistochemistry using antibodies to Ki-67, CC10, and β-tubulin, a marker of ciliated cells (see online supplement). Antibodies and staining techniques for phosphorylated ERK1/2 have been detailed previously (2, 3).

Light Microscopy and Image Analysis

Quantitation of ciliated cells and Alcian blue/PAS-positive mucin cells, was performed on distal bronchioles (restricted to ⩽ 800 μm in perimeter at ×400 magnification and without a surrounding smooth muscle layer), at 4 and 32 days. Ciliated cells were manually counted per total number of bronchiolar epithelial cells on every distal bronchiole in each of two lung sections per mouse. Every distal bronchiole was also scored for the presence or absence of Alcian blue/PAS–positive mucin-containing cells. Image analysis was performed using MetaMorph v6.1 (Universal Imaging, Downingtown, PA).

Statistical Analyses

All data are graphed as Means ± SEM. Statistical significance was evaluated by ANOVA using the Student-Neuman-Keul's procedure for adjustment of multiple pairwise comparisons between treatment groups or using the nonparametric Kruskal-Wallis and Mann-Whitney tests. Values of P < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

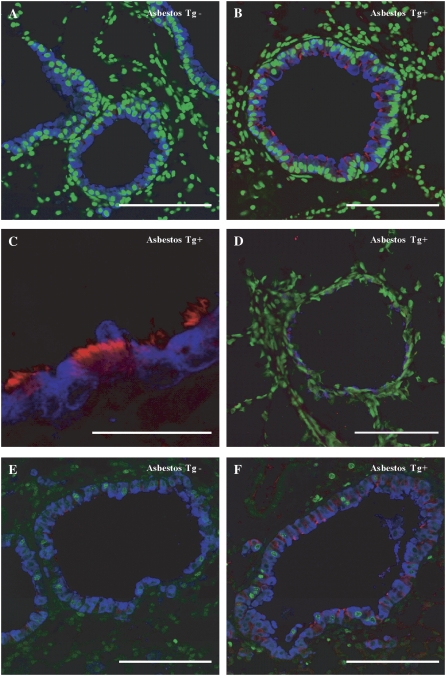

Increased Phosphorylation of p-ERK 1/2 Is Not Observed in Bronchiolar Epithelial Cells of dnMEK1 Tg+ Mice

To determine whether expression of the dnMEK1 transgene affected ERK1/2 phosphorylation in epithelial cells, we performed immunofluorescence studies on lung tissues. These studies showed that phosphorylated ERK1/2 (pERK1/2) was primarily cytoplasmic in bronchiolar epithelial cells, as reported previously (2, 3), and barely detectable in sham Tg− and Tg+ mice (Figure 1, top panels). Inhalation of asbestos caused increases in epithelial cell expression of p-ERK1/2 in Tg− (Figure 1, bottom left panel, arrows) but not Tg+ mouse lungs (Figure 1, bottom right panel).

Figure 1.

Phosphorylation of extracellular signal–regulated kinases 1 and 2 (ERK1/2) is observed in transgene-negative (Tg−), but not Tg+ distal bronchiolar epithelium, of asbestos-exposed mice. Immunofluorescence for phosphorylated ERK1/2 (pERK1/2) in sham mice (top two panels) show little cytoplasmic pERK1/2 (red), whereas increases (arrows) are noted in Tg− (lower left panel) but not Tg+ (lower right panel) epithelial cells exposed to asbestos for 32 days. Scale bar = 100 μM.

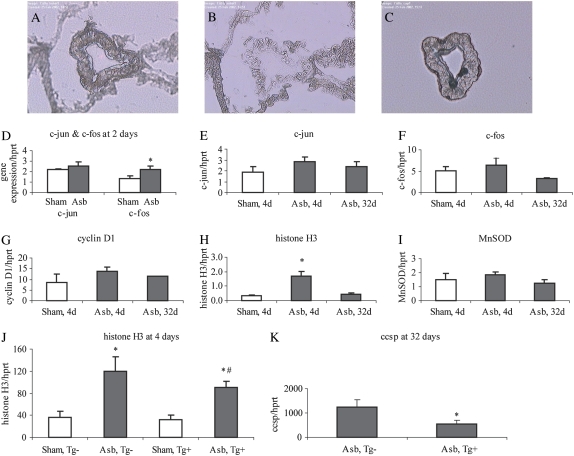

Increased mRNA Levels of c-fos and histone H3 Occur in Distal Bronchiolar Epithelium of C57/BL6 Mice Exposed to Asbestos

We first determined if inhalation of asbestos caused increased expression of the early response protooncogenes c-fos and c-jun, histone H3, and cyclin D1, and the antioxidant enzyme gene, MnSOD or SOD2, in distal bronchiolar epithelial cells, sites of impaction by asbestos fibers (Figures 2A–2C). We used LCM to isolate intact bronchioles of wild-type C57BL/6 mice at 2, 4, and 32 days. As shown in Figures 2D to 2F, increased c-fos (P < 0.05), but not c-jun mRNA levels by asbestos were observed at 2 days, but not other time points, in line with the observations that this is an “early response” protooncogene. Increases in histone H3 expression, but not cyclin D1 or MnSOD expression (Figures 2G–2I) were significantly elevated after asbestos inhalation (P < 0.05). Since c-fos gene expression is activated via the MEK1/2 pathway, the time frame of appearance of increased expression of c-fos and histone H3 in bronchiolar epithelium is consistent with our hypothesis that early increases in MEK1/ERK1/2 signaling precede and may modulate subsequent cell proliferation as confirmed in results below.

Figure 2.

Laser capture microdissection (LCM) and QRT-PCR for determination of gene expression in distal bronchiolar epithelium. A distal bronchiole is shown (A) before, (B) after, and (C) on the polymer film after microdissection. (D–K) Expression of selected genes in captured distal bronchiolar epithelium by QRT-PCR. *P < 0.05 compared with unexposed (sham) group. #P < 0.05 compared with Tg− asbestos group. Mean ± SEM; n = 5–6 mice/group at 2, 4, and 32 days.

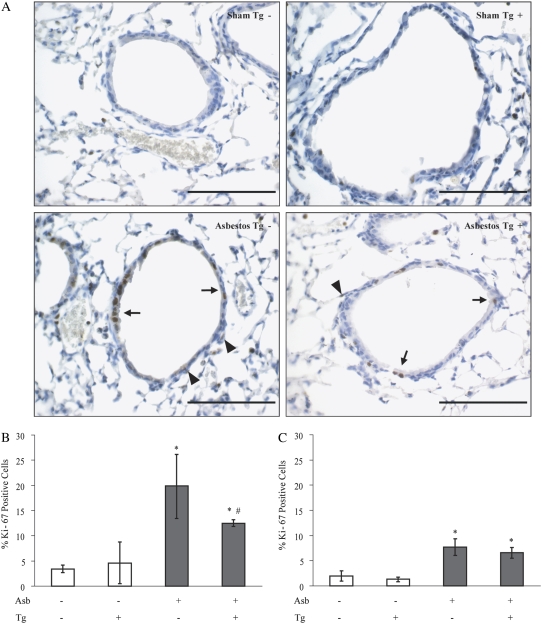

Cellular and Molecular Markers of Proliferation Reveal Decreased Epithelial Cell Proliferation in Response to Asbestos in dnMEK1 Tg+ Mice

We have shown previously that bronchiolar epithelial cell proliferation as measured by incorporation of proliferating cell nuclear antigen (PCNA) peaks at 4 days in C57BL/6 mice exposed to crocidolite asbestos (11). Thus, we examined proportions of cycling cells in the distal bronchiolar epithelium and peribronchiolar regions of these same bronchioles at 4 days using an antibody for Ki-67 (Figure 3A), a marker of cell cycle progression, in Tg− mice and dnMEK1 Tg+ mice. Compared with sham controls, asbestos-exposed mice (solid bars) exhibited increases (P < 0.05) in numbers of Ki-67–positive epithelial cells that were significantly diminished (P < 0.05) in dnMEK1 Tg+ mice compared with Tg− littermates (Figure 3B). In sham dnMEK1 Tg+ and Tg− littermates maintained in clean air, numbers of Ki-67–labeled bronchiolar epithelial cells were comparable, indicating no effect of the transgene on normal baseline proliferation of epithelial cells. Ki-67 positivity of peribronchiolar cells underlying the epithelium was also noted in asbestos-exposed mice at 4 days (Figure 3A, arrowheads). To determine whether targeting of the MEK1 pathway in epithelial cells also affected peribronchiolar (nonepithelial) cell labeling, Ki-67–positive cells were evaluated in this compartment in dnMEK1 Tg+ and Tg− mice (Figure 3C). Although significant increases (P < 0.05) in Ki-67 incorporation were observed in peribronchiolar cells after asbestos exposure (solid bars), numbers of labeled cells were comparable in both Tg+ and Tg− mice inhaling asbestos. These experiments illustrate the specificity of the dnMEK1 transgene in modulating epithelial cell proliferation, but the lack of complete inhibition of asbestos-induced epithelial cell proliferation in dnMEK1 mice suggests that other proliferation/survival pathways may be operative as have been described previously (14, 15).

Figure 3.

Asbestos-induced epithelial cell proliferation at 4 days is reduced in dnMEK1 Tg+ mice. (A) Ki-67 histochemistry in lung sections of mice. Scale bars = 100 μm. (B) Quantitation of numbers of proliferating distal bronchiolar epithelial cells (arrows in A) incorporating an antibody to Ki-67. (C) Quantitation of Ki-67–positive peribronchiolar cells (arrowheads in A) in respective bronchioles showing no transgene effects on proliferation of nonepithelial cells. *P < 0.05 compared with unexposed (sham) group. #P < 0.05 compared with Tg− asbestos group (n = 3–6 mice/group/time point in duplicate experiments).

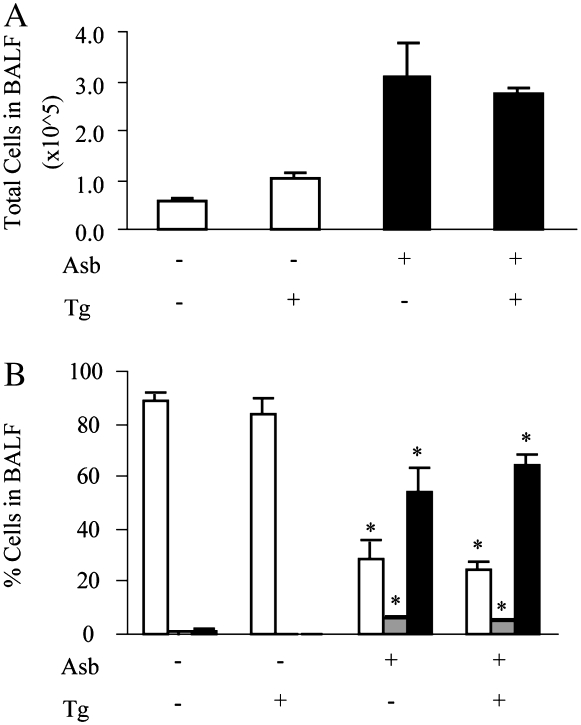

Lung Inflammatory Cell Profiles Are Not Altered in Asbestos-Exposed dnMEK1 Tg+ Mice

The histopathology of asbestos-exposed lungs in dnMEK1 Tg+ mice and Tg− littermates was similar, reflecting focal inflammation and focal interstitial fibrosis developing at the alveolar duct region (11) at 32 days (data not shown). To eliminate the possibility that epithelial expression of dnMEK1 might affect inflammatory cell influx and profiles in response to asbestos, we next examined inflammatory cell populations in bronchoalveolar lavage fluids (BALF) from mice at 9 days, the time point of peak inflammation in this model (11, 12). Compared with sham air controls, inhalation of asbestos resulted in an increase in total numbers of inflammatory cells in BALF in both dnMEK1 Tg+ and Tg– mice (P ⩽ 0.05) (Figure 4A). BALF cells consisted almost exclusively of alveolar macrophages in sham mice, whereas proportions of polymorphonuclear leukocytes (PMNs) and lymphocytes were significantly increased in both dnMEK1 Tg+ and Tg− mice exposed to asbestos (Figure 4B). Thus inflammatory profiles were not altered in asbestos-exposed dnMEK1 Tg+ mice.

Figure 4.

Inflammation in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BALF) is not altered in dnMEK1 Tg+ mice. (A) Recovery of total cells in BALF after 9 days of exposure to asbestos. (B) Percentage of inflammatory cell populations including alveolar macrophages (open bars), lymphocytes (shaded bars), and PMNs (solid bars), in BALF at 9 days. *P < 0.05 compared to air group of same transgene status (n = 3–6 mice/group/time point in duplicate experiments).

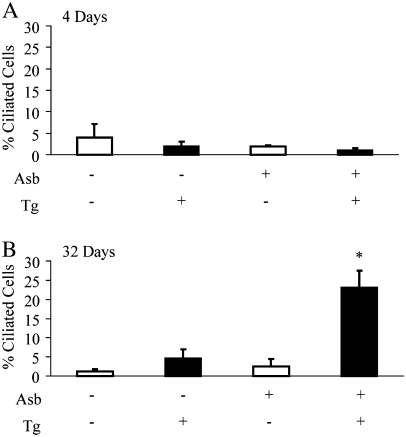

dnMEK1 Tg+ Mice Exhibit Altered Differentiation of Bronchiolar Epithelial Cells after Exposure to Asbestos

In the lung, the more distal airway epithelium is composed almost exclusively of Clara cells. Accordingly, fewer than 5% of ciliated cells were observed in the distal bronchiolar epithelium of all mice at 4 days (Figure 5A). However, the distal bronchioles of asbestos-exposed dnMEK1 Tg+ mice (but not asbestos-exposed Tg− mice) at 32 days were populated with a larger proportion (∼ 25%) (P < 0.05) of ciliated cells (Figure 5B).

Figure 5.

Quantitation of ciliated cells in distal bronchioles of dnMEK1 by light microscopy and image analysis. Tg+ and Tg− mouse lungs at (A) 4 and (B) 32 days after initial exposure to asbestos. *P < 0.05 compared with other groups (n = 3–6 mice/group/time point).

To confirm the presence of ciliated cells and their replicative status in distal bronchioles of asbestos-exposed dnMEK1 Tg+ mice, we performed triple fluorescence immunohistochemistry using antibodies to detect β-tubulin, a component of cilia, CCSP, a marker of Clara cells (which by definition are nonciliated) (16), and Ki-67. Multi-fluorescence approaches revealed that in contrast to sham (Tg− and Tg+) or asbestos-exposed Tg− mice (Figure 6A), ciliated (red) cells were more numerous in the distal bronchioles of asbestos-exposed dnMEK1 Tg+ mice at 32 days (Figures 6B and 6C). As shown in Figure 6D, ciliated cells (blue) in dnMEK1 Tg+ mouse lungs did not express p-ERK1/2 (red). These cells appeared terminally differentiated in that they did not incorporate nuclear Ki-67 (green), as did CCSP-expressing cells (blue) (Figures 6E and 6F). LCM/QRT-PCR was also used to measure CCSP mRNA in asbestos-exposed Tg+ and Tg− bronchioles at 32 days (Figure 2K). These data showed that CCSP was significantly reduced (P < 0.05) in asbestos-exposed dnMEK1 Tg+ bronchioles, confirming the results of immunohistochemical studies. Results in concert indicate that abrogation of the MEK1 cascade causes altered differentiation of asbestos-injured distal bronchiolar epithelial cells.

Figure 6.

Asbestos-exposed dnMEK1 Tg+ mice show increased terminally differentiated ciliated cells in distal bronchioles at 32 days. (A) Asbestos-exposed wild-type (Tg−) and (B) dnMEK1 (Tg+) mouse lungs labeled with anti-CCSP (blue), anti–β-tubulin IV (red) and SYTOX Green (green) to detect nuclei. (C) Higher magnification of anti-CCSP (blue) and anti–β-tubulin (red) labeled bronchiolar epithelium from a dnMEK1 mouse. (D) p-ERK1/2 (red) was not observed in anti–β-tubulin (blue) stained epithelial cells of asbestos-exposed Tg+ mice. (E) Triple labeling of bronchiolar epithelium from asbestos-exposed wild-type (Tg−) and (F) dnMEK1 (Tg+) mice with anti-CCSP (blue), anti–β-tubulin IV (red), and anti–Ki-67 (green) antibodies. Scale bars =100 μm.

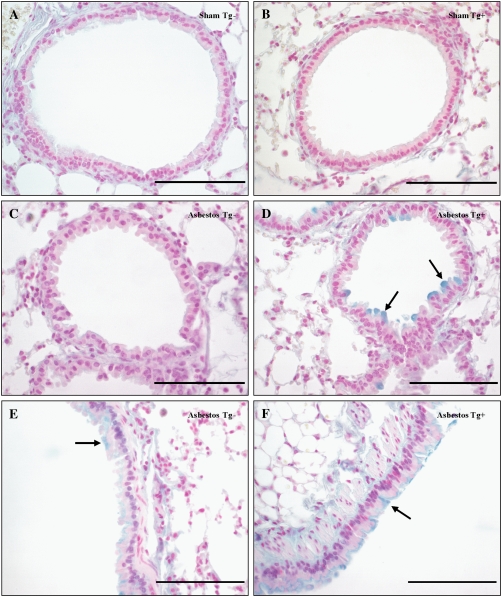

In comparison to sham controls and asbestos-exposed Tg− mouse lungs, we also noted a larger proportion of Alcian blue–positive mucin-secreting cells in the distal airways of asbestos-exposed dnMEK1 Tg+ mouse lungs at 32 days (Figure 7). These cells also stained positively for CCSP (see Figure 6) in accordance with a report that demonstrated mucin production by Clara cells in the airways of ovalbumin-challenged mice (17). Larger airways of asbestos-exposed Tg− and Tg+ mice demonstrated comparable distribution of ciliated and mucin-producing cells as expected (Figures 7E and 7F). However, scoring of distal bronchioles for the proportion of Alcian blue/PAS–positive epithelial cells showed a significant fraction (P < 0.05) of asbestos-exposed dnMEK1 Tg+, but not Tg− mice, exhibiting mucin-positive cells in distal bronchiolar epithelium at 32 days (Table 1).

Figure 7.

Increased numbers of mucin (Alcian blue–positive) cells are seen in asbestos-exposed dnMEK1 Tg+ distal bronchioles at 32 days. (A) Sham Tg− mouse lung. (B) Sham dnMEK1 Tg+ mouse lung. (C) Asbestos-exposed Tg− mouse lung. (D) Asbestos-exposed Tg+ mouse lungs. Larger airways of (E) asbestos-exposed Tg- mouse lung and (F) asbestos-exposed Tg+ mouse lung. Arrows indicate Alcian blue–positive cells. Scale bars = 100 μm.

TABLE 1.

MORPHOMETRIC ANALYSIS OF MUCIN-POSITIVE EPITHELIAL CELLS IN DISTAL BRONCHIOLAR EPITHELIUM

| 4 d

|

32 d

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Time Point: | Mice/Total* | Bronchioles/Total | Mice/Total | Bronchioles/Total |

| Sham Tg− | 0/5 | 0/35 | 0/4 | 0/15 |

| Sham Tg+ (dn MEK1) | 0/5 | 0/45 | 0/6 | 0/34 |

| Asb Tg− | 0/3 | 0/13 | 1/6 | 2/18 |

| Asb Tg+ (dnMEK 1) | 0/5 | 0/23 | 4/5 | 13/32† |

n = 3–6 per group per time point.

P < 0.05 compared with other groups at same time point.

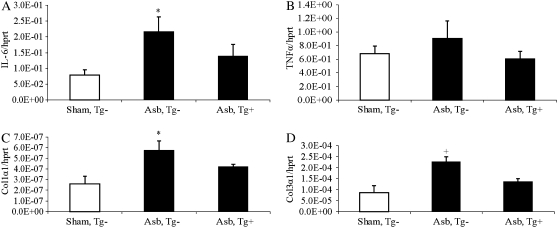

Asbestos-Exposed dnMEK1 Tg+ Mice Exhibit Changes in Molecular Indicators of Lung Remodeling at 32 Days

Although focal fibrosis is observed in lungs of C57BL/6 mice at 30 days after inhalation of crocidolite asbestos (11), these changes are modest and cannot be measured using quantitative biochemical assays for measurement of hydroxyproline. Therefore, to determine if the fibrotic mediators, IL-6 and TNF-α, and expression of procollagen genes were altered at 32 days in asbestos-exposed Tg+ and Tg− mice, QRT-PCR was performed on whole lung homogenates (Tg− sham mice were used for comparisons here due to the paucity of Tg+ mice). These studies revealed that IL-6 mRNA levels were increased in Tg−, but not dnMEK1 Tg+ mice exposed to asbestos (Figure 8A). Although trends were observed in both asbestos-exposed groups, TNFα levels were not increased significantly (Figure 8B). However, both procollagen 1-a-1 and procollagen 3-a-1 mRNA levels were increased in asbestos-exposed Tg− mice compared with sham Tg− mice, whereas dnMEK1 Tg+ mice did not show elevated procollagen levels in response to asbestos (Figures 8C and 8D).

Figure 8.

QRT-PCR reveals that asbestos induces increases in expression of IL-6 and procollagen genes in lungs of Tg− mice at 32 days which are not observed in lungs of dnMEK1 Tg+ mice. (A) mRNA levels of IL-6. (B) mRNA levels of TNF-α. (C) mRNA levels of procollagen 1-α-1. (D) mRNA levels of procollagen 3-α-1. *P < 0.05 compared with sham group; +P < 0.05 in comparison to other groups (n = 5–6 mice/group).

DISCUSSION

Although MAPKs have been intensely investigated in many cell types in vitro, our studies are the first to examine the functional roles of MEK1/ERK1/2 signaling pathways in lung after inhalation of asbestos. We demonstrate that early epithelial cell proliferation after inhalation of asbestos, a pathogenic agent injuring lung epithelium and causing compensatory hyperplasia (18), is modulated by the MEK1 cascade. Asbestos-exposed dnMEK1 Tg+ mice also exhibit abnormal population of distal bronchioles with differentiated ciliated cells and mucin-producing cells, revealing a previously unrecognized role for the MEK1 pathway in epithelial cell differentiation. Our studies showing that altered differentiation occurs after Day 4 in asbestos-exposed dnMEK1 Tg+ distal bronchioles exhibiting less proliferation suggest that increased mitogenesis is not related directly to increases in ciliated and mucin-producing cells. As suggested in a previous report (17), Clara cells may undergo phenotypic changes, giving rise to mucin-secreting cells and not requiring increased cell proliferation. Our studies suggest that lack of MEK1 after asbestos injury causes increased mucin expression, consistent with observations that MAPKs and changes in AP-1 expression control transcription of mucin genes in differentiated epithelial cells in vitro (reviewed in Reference 19). Moreover, the MEK1 pathway has been linked to inhibition of differentiation of human small airway epithelial cells to cells expressing CCSP after exposure to an active metabolite of benzo(a)pyrene (20). The fact that attenuation of MEK1 modulates both asbestos-induced epithelial cell proliferation and differentiation suggests that signaling through MEK1 is crucial for determining the fate of epithelial cells in vivo after injury. However, results do not preclude the possibility that chronic MEK1 epithelial inhibition may also impact responsiveness to inhaled asbestos fibers.

Activation of ERK1/2 signaling has been shown to be important in normal and tumor cell proliferation induced by growth factors and oxidative stress (21, 22). In bronchiolar epithelial cells in vivo and in vitro, asbestos stimulates proliferation, which may be coupled to repair after initial injury by asbestos (2, 3, 22). Moreover, phosphorylated or activated ERK1/2 is observed in bronchiolar epithelium after inhalation of asbestos (2, 3). Using the small molecule MEK1 inhibitor, PD98059, we have shown that crocidolite asbestos stimulates cell cycle progression and proliferation in C10 cells in an ERK1/2-dependent manner (22). Our study here confirms a functional role of ERK1/2 signaling in mitogenesis of bronchiolar epithelium in vivo. The lack of complete inhibition of asbestos-induced epithelial cell proliferation in dnMEK1 Tg+ mice is consistent with published work showing that other transcription factors and cell survival pathways, such as NF-κB and P13K/Akt, are induced by asbestos and are operative in these mice (14, 15).

One possible mechanism by which ERK1/2 activation promotes cell proliferation is by induction of c-fos, a protooncogene encoding c-Fos, a component of the AP-1 transcription factor (23, 24). We show here that inhalation of asbestos causes early up-regulation of c-fos in distal bronchiolar epithelium before the advent of asbestos-associated increases in cell proliferation. Active ERK1/2 phosphorylates the Elk-1 transcription factor, a member of the ternary complex factor (TCF) group of transcription factors (23, 24). In turn, the TCF binds to the serum response element (SRE) of the c-fos promoter, resulting in increased expression of c-Fos protein. Because Fos-Jun heterodimers are more stable than Jun-Jun homodimers, increased expression of c-Fos results in higher AP-1 activity (24). In addition, we have shown that expression of c-Fos–related antigen or Fra-1 is ERK1/2 dependent and critical to transformation of pleural mesothelial cells, presumably by modulating expression of genes such as c-met and cd44 (25).

The present work is the first to implicate the MEK1/ERK1/2 pathway in control of epithelial cell differentiation and remodeling after lung injury in vivo. In a number of in vitro studies, ERK1/2 activity can promote either a differentiated or dedifferentiated phenotype depending upon the cell type involved. For example, in canine kidney epithelial cells (MDCK-C7), constitutive activation of ERK1/2 signaling results in an invasive, less-differentiated, myofibroblast-like state (26). Upon reversal of constitutive activation of ERK1/2 signaling, the cells re-differentiate to epithelial cells. Inhibition of ERK1/2 signaling using the MEK1/2 small molecule inhibitor, U0126, also results in a decrease in branching morphogenesis in fetal lung explants (27). MEK1 is essential for normal thymocyte development, but MEK2 appears to be dispensable for normal embryonic development and thymocyte maturation, suggesting that MEK1 can compensate for a loss in MEK2 function (6).

The fact that epithelial cell and lung remodeling are altered after inhibition of the MEK1 pathway in asbestos-exposed mice is consistent with our recent observation that dnMEK1 Tg+ mice crossed with IL-13–overexpressing mice show inhibition of IL-13–induced inflammation and alveolar remodeling as measured by decreases in IL-13–associated cytokines, cathepsin B, and matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs 2, 9, 12, and 14) (7). Whether epithelial cells play a crucial role in the development of asbestos-induced lung remodeling and pulmonary fibrosis is a question of intense debate and under scrutiny because of potential therapeutic ramifications of targeting epithelial cells. Moreover, diagnosis of pulmonary fibrosis is associated with a poor prognosis, and anti-inflammatory therapies have been generally ineffective and disappointing. Although only focal increases in fibrosis are observed histologically in mouse lungs after 32 days of exposure to crocidolite asbestos, message levels of IL-6 and procollagens increased in lungs at this time point but were decreased significantly in asbestos-exposed dnMEK1 Tg+ mice (Figure 8). These findings suggest that epithelial cell signaling is important to the development of asbestos-induced fibrogenesis. We show that inhibition of MEK1 signaling in lung epithelium results in decreased lung IL-6 expression, a profibrotic cytokine regulated by the ERK1/2 and AP-1 pathways in human lung epithelial cells in vitro (28). IL-6 is implicated in the pathogenesis of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis and asbestosis by enhancing recruitment of inflammatory cell types (reviewed in Reference 29) and stimulating extracellular matrix production by lung fibroblasts. We have reported that IL-6 protein is increased in BALF of mice inhaling asbestos (12), and immunohistochemistry for IL-6 in mouse lungs shows its localization in bronchiolar epithelial cells (T. Sabo-Attwood, unpublished data). Although it is also produced by other cell types, our results support a role for MEK1-regulated, epithelial-derived IL-6 in asbestos-induced lung remodeling. A recent report also shows that TNF-α, which is essential to both asbestos (30) and ozone-mediated lung inflammation in vivo (31), induces TGF-β1 expression in lung fibroblasts in vitro through the ERK1/2 pathway (32). The ERK pathway may also directly affect differentiation of epithelial cells to fibroblasts, and has been identified as a key component in mesenchyme formation and differentiation in the sea urchin embryo (33). In this model, ERK is activated in a spatial-temporal manner coinciding with epithelial–mesenchyme transition and transcription of terminal differentiation genes encoding mesenchymal cell types. This report and work here suggests that blocking the MEK1 cascade may be an effective strategy for inhibiting epithelial cell hyperplasia or altered differentiation, and the advent of fibroproliferative diseases.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge Mary Lou Shane and Tim Hunter from the Vermont Cancer Center DNA Analysis Facility for providing support for QRT-PCR studies. Dr. Mary Gulumian from the National Center of Occupational Health (Johannesburg, South Africa) kindly supplied the sample of crocidolite asbestos for inhalation studies. Laurie Sabens, Beth Langford-Corrigan, and Jennifer Díaz provided valuable assistance in the preparation of this manuscript. Technical assistance in these studies was provided by Stacie Beuschel, Linda Weiss, Nikol A. Manning, Arti Shukla, Maria Ramos-Nino, Justin Robbins, and Masha Stern. The authors acknowledge Dr. Barry Stripp (University of Pittsburgh) and Dr. Francesco DeMayo (Baylor College of Medicine) for providing antibodies to CCSP, and Dr. Jeffrey Whitsett (Children's Hospital of Cincinnati) for supplying the CC10 construct.

This research was funded by grants P01 HL67004 from National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute and T32 07122 from National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences (to B.T.M.).

This article has an online supplement, which is accessible from this issue's table of contents at www.atsjournals.org

Originally Published in Press as DOI: 10.1165/rcmb.2007-0382OC on January 10, 2008

Conflict of Interest Statement: None of the authors has a financial relationship with a commercial entity that has an interest in the subject of this manuscript.

References

- 1.Mossman B, Bignon J, Corn M, Seaton A, Gee J. Asbestos: scientific developments and implications for public policy. Science 1990;247:294–301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Robledo R, Buder-Hoffmann S, Cummins A, Walsh E, Taatjes D, Mossman B. Increased phosphorylated ERK immunoreactivity associated with proliferative and morphologic lung alterations following chrysotile asbestos inhalation in mice. Am J Pathol 2000;156:1307–1316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cummins AB, Palmer C, Mossman BT, Taatjes DJ. Persistent localization of activated extracellular signal-regulated kinases (ERK1/2) is epithelial cell-specific in an inhalation model of asbestosis. Am J Pathol 2003;162:713–720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vantaggiato C, Formentini I, Bondanza A, Bonini C, Naldini L, Brambilla R. ERK1 and ERK2 mitogen-activated protein kinases affect Ras-dependent cell signaling differentially. J Biol 2006;5:14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wang Y, Prywes R. Activation of the c-fos enhancer by the ERK MAP kinase pathway through two sequence elements: the c-fos AP-1 and p62TCF sites. Oncogene 2000;19:1379–1385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pages G, Guerin S, Grall D, Bonino F, Smith A, Anjuere F, Auberger P, Pouyssegur J. Defective thymocyte maturation in p44 MAP kinase (ERK 1) knockout mice. Science 1999;286:1374–1377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lee PJ, Zhang X, Shan P, Ma B, Lee CG, Homer RJ, Zhu Z, Rincon M, Mossman BT, Elias JA. ERK1/2 mitogen-activated protein kinase selectively mediates IL-13-induced lung inflammation and remodeling in vivo. J Clin Invest 2006;116:163–173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Janssen Y, Marsh J, Driscoll K, Borm P, Oberdorster G, Mossman B. Increased expression of manganese-containing superoxide dismutase in rat lungs after inhalation of inflammatory and fibrogenic minerals. Free Radic Biol Med 1994;16:315–322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stripp BR, Sawaya PL, Luse DS, Wikenheiser KA, Wert SE, Huffman JA, Lattier DL, Singh G, Katyal SL, Whitsett JA. Cis-acting elements that confer lung epithelial cell expression of the CC10 gene. J Biol Chem 1992;267:14703–14712. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Alessandrini A, Greulich H, Huang W, Erikson RL. MEK1 phosphorylation site mutants activate Raf-1 in NIH 3T3 cells. J Biol Chem 1996;271:31612–31618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Manning C, Cummins A, Jung M, Berlanger I, Timblin C, Palmer C, Taatjes D, Hemenway D, Vacek P, Mossman B. A mutant epidermal growth factor receptor targeted to lung epithelium inhibits asbestos-induced proliferation and proto-oncogene expression. Cancer Res 2002;62:4169–4175. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sabo-Attwood T, Ramos-Nino M, Bond J, Butnor KJ, Heintz N, Gruber AD, Steele C, Taatjes DJ, Vacek P, Mossman BT. Gene expression profiles reveal increased mClca3 (Gob5) expression and mucin production in a murine model of asbestos-induced fibrogenesis. Am J Pathol 2005;167:1243–1256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Alterman RB, Ganguly S, Schulze DH, Marzluff WF, Schildkraut CL, Skoultchi AI. Cell cycle regulation of mouse H3 histone mRNA metabolism. Mol Cell Biol 1984;4:123–132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Janssen Y, Barchowsky A, Treadwell M, Driscoll K, Mossman B. Asbestos induces nuclear factor kappa B (NF-kappa B) DNA-binding activity and NF-kappa B-dependent gene expression in tracheal epithelial cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1995;92:8458–8462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ramos-Nino ME, Vianale G, Sabo-Attwood T, Mutti L, Porta C, Heintz N, Mossman BT. Human mesothelioma cells exhibit tumor cell-specific differences in phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/AKT activity that predict the efficacy of Onconase. Mol Cancer Ther 2005;4:835–842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Broeckaert F, Bernard A. Clara cell secretory protein (CC16): characteristics and perspectives as lung peripheral biomarker. Clin Exp Allergy 2000;30:469–475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Evans CM, Williams OW, Tuvim MJ, Nigam R, Mixides GP, Blackburn MR, DeMayo FJ, Burns AR, Smith C, Reynolds SD, et al. Mucin is produced by clara cells in the proximal airways of antigen-challenged mice. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 2004;31:382–394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mossman BT, Craighead JE, MacPherson BV. Asbestos-induced epithelial changes in organ cultures of hamster trachea: inhibition by retinyl methyl ether. Science 1980;207:311–313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mossman BT, Lounsbury KM, Reddy SP. Oxidants and signaling by mitogen-activated protein kinases in lung epithelium. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 2006;34:666–669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jyonouchi H, Sun S, Iijima K, Wang M, Hecht SS. Effects of anti-7,8-dihydroxy-9,10-epoxy-7,8,9,10-tetrahydrobenzo[a]pyrene on human small airway epithelial cells and the protective effects of myo-inositol. Carcinogenesis 1999;20:139–145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Blanc A, Pandey NR, Srivastava AK. Synchronous activation of ERK 1/2, p38 MAPK and PKB/Akt signaling by H2O2 in vascular smooth muscle cells: potential involvement in vascular disease. Int J Mol Med 2003;11:229–234. (review). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Buder-Hoffmann S, Palmer C, Vacek P, Taatjes D, Mossman B. Different accumulation of activated extracellular signal-regulated kinases (ERK 1/2) and role in cell-cycle alterations by epidermal growth factor, hydrogen peroxide, or asbestos in pulmonary epithelial cells. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 2001;24:405–413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Babu GJ, Lalli MJ, Sussman MA, Sadoshima J, Periasamy M. Phosphorylation of elk-1 by MEK/ERK pathway is necessary for c-fos gene activation during cardiac myocyte hypertrophy. J Mol Cell Cardiol 2000;32:1447–1457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Reddy SP, Mossman BT. Role and regulation of activator protein-1 in toxicant-induced responses of the lung. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 2002;283:L1161–L1178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ramos-Nino ME, Scapoli L, Martinelli M, Land S, Mossman BT. Microarray analysis and RNA silencing link fra-1 to cd44 and c-met expression in mesothelioma. Cancer Res 2003;63:3539–3545. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schramek H, Feifel E, Marschitz I, Golochtchapova N, Gstraunthaler G, Montesano R. Loss of active MEK1-ERK1/2 restores epithelial phenotype and morphogenesis in transdifferentiated MDCK cells. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 2003;285:C652–C661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kling DE, Lorenzo HK, Trbovich AM, Kinane TB, Donahoe PK, Schnitzer JJ. MEK-1/2 inhibition reduces branching morphogenesis and causes mesenchymal cell apoptosis in fetal rat lungs. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 2002;282:L370–L378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Simeonova PP, Toriumi W, Kommineni C, Erkan M, Munson AE, Rom WN, Luster MI. Molecular regulation of IL-6 activation by asbestos in lung epithelial cells: role of reactive oxygen species. J Immunol 1997;159:3921–3928. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mossman B, Churg A. State-of-the-art: mechanisms in the pathogenesis of asbestosis and silicosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1998;157:1666–1680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Liu JY, Brody AR. Increased TGF-beta1 in the lungs of asbestos-exposed rats and mice: reduced expression in TNF-alpha receptor knockout mice. J Environ Pathol Toxicol Oncol 2001;20:97–108. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cho HY, Morgan DL, Bauer AK, Kleeberger SR. Signal transduction pathways of tumor necrosis factor–mediated lung injury induced by ozone in mice. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2007;175:829–839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sullivan DE, Ferris M, Pociask D, Brody AR. Tumor necrosis factor-alpha induces transforming growth factor-beta1 expression in lung fibroblasts through the extracellular signal-regulated kinase pathway. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 2005;32:342–349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fernandez-Serra M, Consales C, Livigni A, Arnone MI. Role of the ERK-mediated signaling pathway in mesenchyme formation and differentiation in the sea urchin embryo. Dev Biol 2004;268:384–402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]