Abstract

The spectrin cytoskeleton assembles within discrete regions of the plasma membrane in a wide range of animal cell types. Although recent studies carried out in vertebrate systems indicate that spectrin assembly occurs indirectly through the adapter protein ankyrin, recent studies in Drosophila have established that spectrin can also assemble through a direct ankyrin-independent mechanism. Here we tested specific regions of the spectrin molecule for a role in polarized assembly and function. First, we tested mutant β-spectrins lacking ankyrin binding activity and/or the COOH-terminal pleckstrin homology (PH) domain for their assembly competence in midgut, salivary gland, and larval brain. Remarkably, three different assembly mechanisms operate in these three cell types: 1) neither site was required for assembly in salivary gland; 2) only the PH domain was required in midgut copper cells; and 3) either one of the two sites was sufficient for spectrin assembly in larval brain. Further characterization of the PH domain revealed that it binds strongly to lipid mixtures containing phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate (PIP2) but not phosphatidylinositol 3,4,5-trisphosphate. A K8Q mutation in the lipid binding region of the PH domain eliminated the PIP2 interaction in vitro, yet the mutant protein retained full biological function in vivo. Reporter gene studies revealed that PIP2 and the spectrin PH domain codistribute with one another in cells but not with authentic wild type αβ-spectrin. Thus, it appears that the PH domain imparts membrane targeting activity through a second mechanism that takes precedence over its PIP2 binding activity.

Spectrin is the major protein component of a submembrane cytoskeletal scaffold found in animal cells. Spectrin and its adapter ankyrin are thought to have broad roles in the formation, organization, and stabilization of the plasma membrane in diverse cell types. For example, genetic studies have uncovered effects of spectrin mutations on the shape and/or stability of the plasma membrane in human erythrocytes and in epithelial cells and neurons (1-6). A second important function became apparent in studies of polarized cells where spectrin and ankyrin are restricted to specialized subdomains of the plasma membrane. Mutations in spectrin or ankyrin result in a failure of interacting membrane activities, such as ion pumps and channels, to accumulate at their normal sites of function (reviewed in Ref. 7). Recent studies of human bronchial epithelial cells suggest a more pivotal role in which spectrin and ankyrin are required for the lateral membrane domain to form at all (8, 9).

The polarized distributions of spectrin and ankyrin observed in diverse cell types suggest that there are active mechanisms that generate polarity. However, it has proven difficult to identify cues that direct spectrin and ankyrin to specific membrane domains. There has been recent progress in understanding how spectrin and ankyrin respond to their assembly cues. Genetic studies in mice suggest that targeting in cardiomyocytes and neurons occurs through ankyrin (10, 11). Mutations in ankyrin that interfere with its ability to bind to spectrin lead to a failure of spectrin recruitment to the plasma membrane, but they do not appear to affect targeting of ankyrin. These results suggest that there is a receptor(s) that acts through ankyrin to recruit spectrin cytoskeleton assembly. In the case of the node of Ranvier, that receptor appears to be neurofascin 186 (12).

In contrast, recent genetic studies in Drosophila revealed that there are ankyrin-independent sites that have an important role in targeting spectrin to the plasma membrane in epithelia, neurons, and muscle (13-15). Inactivation of the ankyrin binding activity of spectrin did not detectably alter the recruitment of spectrin to the plasma membrane in any of the cells that were examined. It is remarkable that in two experimental systems, using a similar approach to test the contributions of spectrin and ankyrin, exactly the opposite results were obtained. Ankyrin appears to function and be recruited independently of spectrin in mice, and spectrin appears to function and be recruited independently of ankyrin in fruit flies. Further studies are required to distinguish whether these are differences between systems or trivial differences between the cell types that have been amenable for study thus far.

In this study, we characterized mechanisms of spectrin assembly in Drosophila using a genetic approach. Transgene rescue is a straightforward strategy that relies on the lethality of α and β-spectrin mutations and the ability to rescue the lethal phenotype using cDNA-based transgenes encoding functional spectrin subunits. By using modified transgenes, it is possible to test the contributions of individual sites in spectrin to its assembly and function. Here we set out to characterize the activity of the PH2 domain that explains its role in targeting. Previous work established that in midgut copper cells (an epithelial cell type), spectrin assembly was abolished by removal of the PH domain from the COOH terminus of β-spectrin but not by removal of the ankyrin-binding domain (13). We also followed up the observation that neither the ankyrin-binding domain nor the PH domain was required for spectrin targeting in the salivary gland. Here we asked if these two activities could make a redundant contribution to assembly by characterizing a doubly mutated transgene. In the course of our studies, we observed a striking pattern of spectrin antibody labeling in the larval brain and found that spectrin behavior in the brain was different from either of the two epithelial cell types characterized here. We used a combined biochemical and genetic approach to examine how the PH domain contributes to spectrin targeting and function. The results reveal an unexpected complexity in the mechanisms that explain polarized assembly of the spectrin cytoskeleton in diverse cell types.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Antibodies

Rabbit anti-β-spectrin antibody (KCar) (16), mouse anti-α-spectrin antibody (3A9) (17), mouse anti Myc epitope monoclonal antibody (9E10) (18), and rabbit anti-Scribble (a gift from Chris Doe) (19) were used as indicated. Immunoprecipitation from transgenic embryo homogenates was carried out as previously described (16). Briefly, 150 μl of dechorionated 12-24 h embryos carrying a homozygous insertion of the ΔPH transgene were homogenized in TBS plus 1% Triton X-100 containing the protease inhibitors benzamidine and leupeptin. The clarified supernatant was incubated with anti-Myc epitope antibody, and antibody complexes were reacted with Pansorbin (Calbiochem) for 1 h at 4 °C. Pansorbin was pelleted and washed in buffer two times before dissolving in SDS sample buffer for Western blotting.

Fly Stocks and Transgenes

The midgut expression driver Mex-Gal4 (20) and β 21-3-1 encoding a Myc-tagged UAS β-spectrin PH domain transgene (21) were kindly provided by Dr. Graham Thomas. The neuronal driver elav-Gal4 was kindly provided by Dr. Christian Klambt (Uni Muenster, Germany). The PIP2-binding PLCγ PH domain-GFP reporter was kindly provided by Dr. Franck Pichaud (22). The heat shock Gal4 line (1799), which is constitutively expressed in larval salivary gland and midgut (13), and Repo-Gal4 a glial cell reporter (line 7415) were obtained from the Bloomington Stock Center. UAS DS-Red was kindly provided by Dr. Dave Featherstone (University of Illinois, Chicago, IL).

Production of the wild type βspecKW3A and modified βspecΔPH and βspeca13 transgenes was previously described (13). The previously described lethal spectrin allele βspecem6 (3) was recently shown to encode a truncated product that behaves as a functional null (23). New transgenes were produced by site-directed mutagenesis of the parent plasmid WUMB-β-spectrin (3) using primers synthesized by Operon. Sequences were verified at the DNA Services Facility at the University of Illinois at Chicago Research Resource Center. Transgenic lines were produced by standard embryo microinjection into w1118 by Genetic Services, Inc.

βspecα13+ΔPH

To produce the double mutant plasmid, a stop codon was introduced at codon 2144 of the βspecα13 plasmid by mutagenesis, as previously described (13).

βspecK8Q

A point mutation was introduced at codon 2157 using QuikChange with the primer sequence 5′-GAAGGATATGTGACACGACAGCACGAGTGGGACTCG.

βspecK17Q

A point mutation was introduced at codon 2166 using QuikChange with the primer sequence 5′-GACTCGACCACCAAGCAGGCCTCCAACCGATC.

UAS βspec95

The Myc epitope-tagged coding sequence from βspecKW3A was inserted into the pUAST vector to produce a Gal4-inducible tagged β-spectrin. The production and characteristics of this transgene will be described in greater detail elsewhere.

Rescue Crosses

The biological function of transgenes carrying point mutations in the PH domain was tested by first crossing the autosomal insertions into a C(1)Dx (compound X) background. C(1)Dx/Y;+/+ females were mated to +/Y;transgene/transgene males to produce an F1 C(1)Dx/Y;transgene/+ fly (supplemental Fig. S1). These F1 females were next crossed to βspecem6/Y;Dp(1:3)BarS3i D3/+ males. In these males, the endogenous β-spectrin gene on X is lethally mutated. Their survival depends on the presence of an X chromosome duplication on chromosome 3. The duplication includes a wild type copy of the β-spectrin gene as well as a mutation in the neighboring Bar gene, which has an easily scored dominant eye phenotype. The compound X chromosome causes an unusual pattern of inheritance in which daughters receive the compound X chromosome from their mothers and sons receive the X chromosome from their fathers (and a copy of the Y chromosome from their mother). Because all males inherit the βspecem6 X chromosome from their father, they can only survive if they inherit a functioning copy of the β-spectrin gene, either via the duplication chromosome or a transgene. Because the rescue cross parents are heterozygous for the duplication (father) and for the transgene insertion (mother), there are four expected male progeny classes. Female progeny all inherit the compound X chromosome carrying a wild type copy of the β-spectrin gene and therefore are not of interest here. Rescue crosses with wild type transgenes yield a net 2:1 ratio of Bar-eyed to non-Bar-eyed male progeny in this scheme (13). One class (shaded) does not inherit a functioning copy of the β-spectrin gene, and these males die as embryos. One-third of the remaining progeny carry a copy of the transgene but not the duplication chromosome marked by Bar. The other two thirds of the males inherit the duplication, either alone or together with the transgene (these all survive). If a test transgene lacks function, then only those males that inherit the duplication can survive, and consequently all of the males have the Bar eye phenotype.

Microscopy

Larval midguts, salivary gland, and brain were dissected and stained as previously described (3) and mounted using Vectashield mounting medium at room temperature. Images were captured using an Olympus FV500 confocal microscope with a ×60 Plan-Apo oil immersion objective (numerical aperture 1.4) and Fluoview 2.1 software. Brightness settings were adjusted for control specimens (either wild type siblings or expression level-matched transgenes) using the photomultiplier, and settings were kept constant for capturing data when samples were to be compared. Images were saved as “Experiments” in Fluoview and were converted to jpeg format by NIH ImageJ. Montages were assembled using Photoshop 6.0 (Adobe), and γ adjustments after conversion to grayscale were performed with all panels simultaneously.

Western Blots

Adult flies and immunoprecipitates were processed for antibody staining as previously described (13). Fly samples shown were processed in parallel to allow visual comparison of band intensities. Mobility standards were the SDS6H kit from Sigma.

Lipid Binding Assays

Materials—1-Palmitoyl-2-oleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine (POPC), 1-palmitoyl-2-oleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphoethanolamine (POPE), and 1-palmitoyl-2-oleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphoserine (POPS) were purchased from Avanti Polar Lipids, Inc. (Alabaster, AL). phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate (PtdIns(4,5)P2), and phosphatidylinositol-3,4,5-triphosphate (PtdIns(3,4,5)P3) were purchased from Cayman Chemical Co. (Ann Arbor, MI). The concentrations of the phospholipids were determined by a modified Bartlett analysis. CHAPS and octyl glucoside were purchased from Fisher. The Pioneer L1 sensor chip was purchased from Biacore AB (Piscataway, NJ).

Protein Expression and Purification—A PH domain fragment of Drosophila β-spectrin corresponding to codon 2144 through the stop codon was amplified by PCR and cloned in the Topo cloning vector (Invitrogen) for DNA sequencing. The BamHI-EcoRI insert fragment was cloned in the pGEX-3X vector, and the protein product was expressed and purified using standard conditions. Briefly, cells were induced with IPTG for 14 h at 25 °C, harvested by centrifugation, and then lysed by sonication in 20 mm Tris buffer, pH 8, containing 160 mm KCl, 50 μm phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, 2 mm dithiothreitol, and 0.1% Triton X-100. Protein was purified using glutathione S-transferase-Tag™ resin (Novagen, Madison, WI) and eluted with 20 mm glutathione. Purified protein was stored in 20 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, with 0.16 m KCl at 4 °C.

Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) Measurements—All SPR measurements were performed at 23 °C using a lipid-coated L1 chip in the BIACORE X system as described previously (24). Briefly, after washing the sensor chip surface with the running buffer (20 mm HEPES, pH 7.4, containing 0.16 m KCl), POPC/POPE/POPS/PtdIns(4,5)P2 (57:20:20:3) and POPC (100%) vesicles were injected at 5 ml/min into the active surface and the control surface, respectively, to give the same resonance unit values. The level of lipid coating for both surfaces was kept at the minimum that is necessary for preventing nonspecific adsorption to the sensor chips. This low surface coverage minimized the mass transport effect and kept the total protein concentration (P0) above the total concentration of protein binding sites on vesicles (M0) (25). Equilibrium SPR measurements were done at a flow rate of 15 ml/min to allow sufficient time for the R values of the association phase to reach near equilibrium values (Req) (26). After sensorgrams were obtained for five or more different concentrations of each protein within a 10-fold range of Kd, each of the sensorgrams was corrected for refractive index change by subtracting the control surface response from it. Assuming a Langmuir-type binding between the protein (P) and protein binding sites (M) on vesicles (i.e. P + M [dharrow] PM) (25), Req values were then plotted versus P0, and the Kd value was determined by a nonlinear least squares analysis of the binding isotherm using an equation, Req = Rmax/(1 + Kd/P0) (25). Each data set was repeated three or more times to calculate average and S.D. values. For kinetic SPR measurements, the flow rate was maintained at 30 ml/min for both association and dissociation phases.

RESULTS

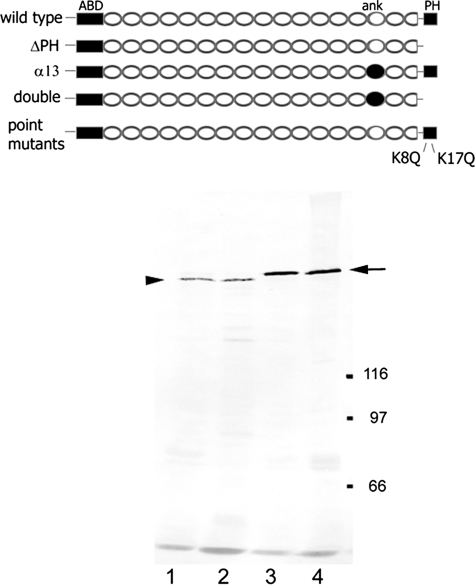

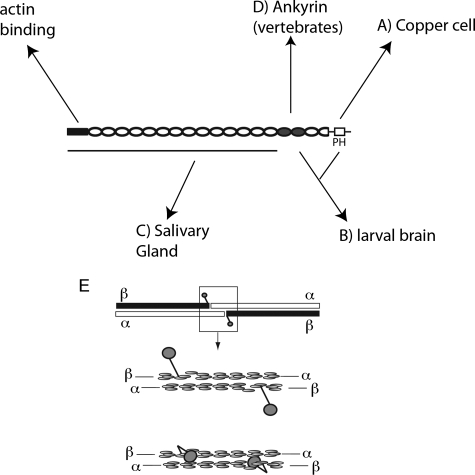

Characterization of a Double Mutant β-Spectrin Transgene Lacking the PH and Ankyrin-binding Domains—We previously described a panel of recombinant Drosophila β-spectrin transgenes carrying an NH2-terminal Myc epitope tag and expressed under control of the Drosophila ubiquitin promoter (13). One of the transgenes (ΔPH) had a stop codon introduced into the first codon of the COOH-terminal PH domain (ΔPH; Fig. 1, top). On Western blots of transgenic flies, the ΔPH product (Fig. 1, bottom, lane 1) had a slightly faster mobility than full-length control transgenes (e.g. lanes 3 and 4) when probed with the anti-Myc epitope antibody. In another transgene, α13, the 15th spectrin repeat in the β-spectrin sequence was removed and replaced with the 13th repeat from Drosophila α-spectrin (filled ellipse). The α13 product comigrated with full-length (266-kDa) wild type β-spectrin on Western blots (13). Here we produced a double mutant transgene by introducing the ΔPH stop codon into the PH domain sequence of α13. Transgenic flies expressing this transgene exhibited a truncated product on Western blots that was identical in size to ΔPH (lane 2). Both of these truncated transgene products appeared relatively stable and accumulated at significant levels in transgenic flies, although they were less abundant than full-length transgene products (lanes 3 and 4; described below).

FIGURE 1.

Production of modified β-spectrin transgenes. Top, β-spectrin is divided into discrete structural domains, including an NH2-terminal actin-binding domain (ABD), a COOH-terminal PH domain, 16 copies of degenerate ∼106-amino acid-long spectrin repeats (ellipses), and one partial (2 of 3) repeat near the COOH terminus. Two of the degenerate repeats (14 and 15) have been implicated in ankyrin (ank) binding activity. All recombinant transgenes include a 10-amino acid Myc epitope tag at the NH2 terminus in place of the first 10 natural codons of β-spectrin. Modified transgenes include ΔPH (truncated PH domain), α13 (ankyrin binding repeat of β-spectrin replaced with inactive repeat 13 of α-spectrin), double mutant (both of the above modifications), and point mutations at codons 2157 (K8Q) and 2166 (K17Q). Bottom, Western blot of total proteins from transgenic flies expressing modified transgenes in a wild type background (0.8 fly/lane). Lane 1, ΔPH; lane 2, double mutant; lane 3, K8Q; lane 4, K17Q. Blot strips were stained with anti-Myc antibody 9E10 and alkaline phosphatase conjugated secondary antibody. Molecular mass markers are indicated to the right in kDa. The arrow marks the mobility of full-length β-spectrin, and the arrowhead marks the position of the truncated ΔPH products.

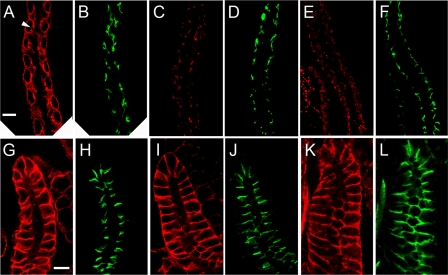

We compared the behavior of the double mutant transgene product with that of the single mutants by immunofluorescent staining of tissues from larvae lacking endogenous wild type β-spectrin. In midgut copper cells, the wild type β-spectrin transgene product exhibited a characteristic pattern corresponding to the basolateral domain of these cells (Fig. 2A, arrowhead). That pattern was completely lost in ΔPH mutant larvae (Fig. 2C) and also in larvae expressing the double mutant transgene (Fig. 2E), but despite the loss of basolateral spectrin, the overall morphology of the midgut epithelium was largely intact, as revealed by staining with the septate junction marker Scribble (Fig. 2, B, D, and F).

FIGURE 2.

Targeting of mutant β-spectrin transgene products to the plasma membrane of copper cells (A-F) and salivary gland (G-L). Transgene products were detected with the anti-Myc antibody and TRITC-labeled secondary antibody (red) and compared with the pattern of Scribble staining as a control for the septate junction labeled with FITC secondary antibody (green). All specimens are βspecem6 males that lack endogenous wild type β-spectrin. The wild type transgene product βspecKW3A exhibited the typical basolateral staining pattern with a small gap corresponding to the vestibule to the apical invagination (visible in favorable sections; arrowhead). Scribble staining (B) marks septate junctions, which appear as comma shapes on either side of the opening to the apical invagination. Plasma membrane labeling was lost in the ΔPH (C) and double mutants (E), although Scribble staining of septate junctions revealed that the epithelium remained intact. The wild type β-spectrin exhibited basolateral staining in the salivary gland, primarily at lateral contacts (G), including the septate junction (marked by Scribble; H). Both the ΔPH (I) and the double mutant transgene (K) exhibited the same pattern of lateral membrane staining. Bars, 10 μm.

In the larval salivary gland epithelium, the ΔPH transgene product (Fig. 2I) had a distribution identical to that of the wild type transgene product (Fig. 2G). Spectrin was highly enriched throughout the lateral zone of cell-cell contact, including the apicolateral septate junction region marked with Scribble (Fig. 2, H and J). The same pattern was also observed with the double mutant (Fig. 2K), indicating that neither the PH domain nor the ankyrin-binding domain was required for spectrin to assemble at the lateral membrane. Thus, there were different requirements for polarized spectrin assembly in the salivary gland and midgut epithelium.

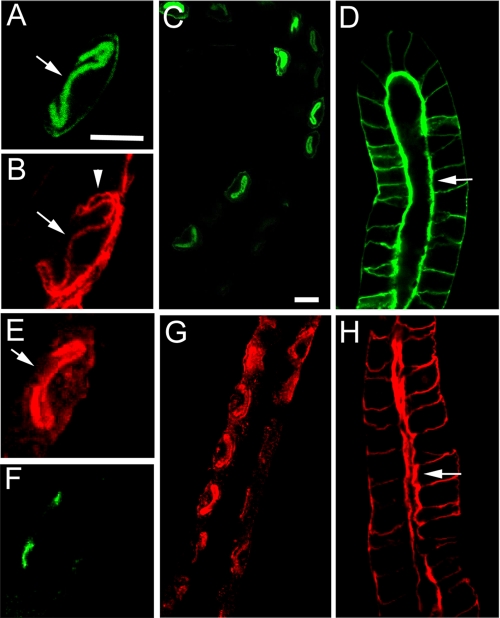

Spectrin Targeting in the Larval Brain—While analyzing the fate of β-spectrin transgenes in dissected larval preparations, we observed a striking pattern of Myc epitope staining in the first instar larval brain. Staining with a monoclonal anti-α-spectrin antibody also detected a cortical pattern of labeled cell outlines a few cells thick, shown en face here (Fig. 3A). The same pattern was observed with polyclonal rabbit anti-β-spectrin antibody (Fig. 3, C and D, green). Most of these cells correspond to neurons, since they could also be labeled by expressing cytoplasmic UAS DS-Red under control of the neuronal driver elav-Gal4 (Fig. 3, C and D, red). This pattern verified that each “cell” outlined by spectrin staining was simply the plasma membrane of a single cell that was closely apposed to neighboring cells. The pattern of elav-Gal4 expression was not uniform, since it did not drive DS-Red expression in all of the cells that could be stained with spectrin antibody. However, when elav-Gal4 was used to drive expression of a UAS-Myc-tagged β-spectrin transgene, we routinely observed large zones in which nearly every cell was labeled (Fig. 3B), albeit at widely varying levels. Thus, we conclude that most of the spectrin labeling pattern described here represents sites of plasma membrane contact between neighboring neurons.

FIGURE 3.

Distribution of spectrin in the first instar larval brain. Staining of dissected brain tissue with mouse anti-α-spectrin antibody (A) or rabbit anti-β-spectrin antibody (C and D; green) revealed a cortical layer of staining, 2-3 cells deep. Expression of the soluble reporter DSRed under control of elav-Gal4 revealed that the space within spectrin-stained outlines corresponds to single cells (C and D; red). Expression of Myc-tagged UAS β-spectrin under control of elav-Gal4 (B) produced much of the same pattern detected with antibodies against endogenous spectrin, indicating that much of the staining corresponds to cortical neurons. Bar, 10 μm.

We analyzed the effects of the three modified β-spectrin transgenes described above on the behavior of spectrin in the larval brain cortex. As in the salivary gland, removal of the ankyrin binding site (α13) left the membrane staining pattern in the brain intact (Fig. 4A). The ΔPH staining pattern also resembled the wild type pattern (Fig. 4B), although it was possible to find breaks in the pattern in some fields (e.g. Fig. 4C). In either case, most of the labeling pattern was still restricted to the plasma membrane. In contrast, the regular pattern of cell outlines was no longer visible in larvae expressing the double mutant (Fig. 4D). The speckled pattern superficially resembles the speckled pattern ΔPH staining observed in midgut copper cells (Fig. 2, C and E). Analysis of Z-stacks suggests that some of the pattern represents intracellular aggregates, but we cannot rule out the possibility that there is some residual plasma membrane staining. However, the behavior of the double mutant is distinctly different in the larval brain (and copper cells) compared with the salivary gland.

FIGURE 4.

Effects of spectrin mutations on transgene product targeting in larval brain. The α13 mutant lacking ankyrin binding activity (A) and the ΔPH mutant (B) both exhibited the wild type pattern of β-spectrin staining in βspecem6 neurons, although gaps in the plasma membrane labeling pattern were often observed in the latter (C). In contrast, the double mutant transgene lacking both ankyrin binding and the PH domain no longer exhibited the characteristic plasma membrane staining pattern (D). Bar, 10 μm.

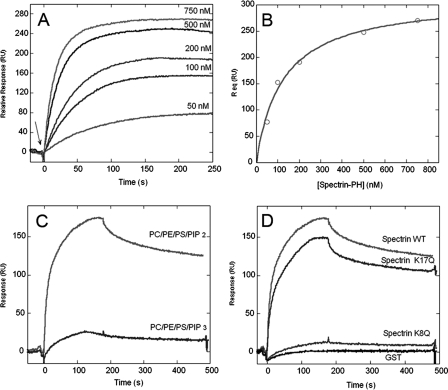

Functional Analysis of the PH Domain—PH domains are found in hundreds of different proteins, and in many cases they exhibit phosphoinositide binding activity (27). Previous studies showed that inositol phosphate binding activity is a conserved feature of PH domains in mammalian and Drosophila spectrin (28, 29). Here we analyzed the lipid binding activity of the PH domain from Drosophila β-spectrin using recombinant pGEX fusion proteins. The PH domain coding sequence from codon 2088 to the stop codon was amplified by PCR and cloned into pGEX-3X for inducible expression and purification of a GST fusion protein. We quantitatively characterized the binding of purified GST-βspec-PH by equilibrium SPR analysis. Binding sensorgrams for GST-βspec-PH reacted with mixed lipid vesicles containing PtdIns(4,5)P2 (Fig. 5A) were used to generate a binding isotherm (Fig. 5B) that yielded a Kd of 125 ± 18 nm. Previous binding assays using soluble GPIns(4,5)P2 as ligand obtained an estimated Kd of ∼40 μm (29).

FIGURE 5.

Membrane binding activity of the spectrin PH domain measured by equilibrium SPR analysis. A, purified β-spectrin PH domain GST fusion was injected at 15 μl/min at varying concentrations (as indicated) over the POPC/POPE/POPS/PtdIns(4,5)P2 (57:20:20:3)-coated surface, and Req was measured (the arrow marks sample injection). B, binding isotherm generated from Req (average of triplicate measurements) versus the concentration of β-spectrin. A solid line represents a theoretical curve constructed from Rmax (313 ± 14) and Kd (125 ± 18 nm). 20 mm HEPES buffer, pH 7.4, with 0.16 m KCl was used for all measurements. C, kinetics of binding of wild type β-spectrin PH to lipid mixtures containing either PtdIns(4,5)P2 or PtdIns(3,4,5)P3. D, kinetics of binding of β-spectrin PH wild type (WT), β-spectrin PH K17Q, β-spectrin PH K8Q, and GST control to surfaces coated with the above lipid mixture, including PtdIns(4,5)P2. Flow rate is 30 μl/min and protein concentration is 1 μm in C and D.

It has been reported that GST-tagged proteins have a tendency to dimerize. When we checked the possibility of the dimerization of the GST-tagged spectrin PH domain by gel filtration chromatography, more than 90% of the protein was eluted as monomer even at 100 μm initial concentration (data not shown). This indicates that under our experimental conditions ([protein] < 1 μm), the GST-tagged spectrin PH domain exists predominantly as monomer. No significant interaction with lipid was detected using purified GST alone in this assay (Fig. 5D).

PH domains from different proteins exhibit signature preferences for specific phosphoinositides (27). We previously speculated that spectrin might interact with growth signaling pathways that rely on PI-3 kinase activity to recruit PH domain-containing proteins to the plasma membrane (13). Here we compared the ability of GST-βspec-PH to bind to PtdIns(4,5)P2 and PtdIns(3,4,5)P3 using the SPR assay. The results indicate a marked preference of the spectrin PH domain for PtdIns(4,5)P2 (Fig. 5C). Thus, spectrin is unlikely to have a direct role in growth factor signal transduction downstream of phosphatidylinositol 3,4,5-trisphosphate formation.

Structural analysis of the spectrin PH domain led to the identification of specific amino acid positions that contact the lipid head group. Mutagenesis studies identified a K8Q mutation at one contact site that interfered with GPIns(4,5)P2 binding activity in vitro (29). A similar point mutation at a conserved noncontact position in the PH domain (K17Q) had no effect on ligand binding in that assay. We engineered the same two mutations into the GST-βspec-PH construct and then measured their effects on lipid binding in the SPR assay. The lipid binding activity of the K17Q mutant fusion protein was only slightly reduced relative to the wild type control (Fig. 5D). However, lipid binding activity was nearly abolished by the K8Q mutation, consistent with the observed effect of the corresponding mutation on mammalian spectrin binding to GPIns(4,5)P2.

To evaluate the effects of the K8Q and K17Q mutations in vivo, we introduced the same two point mutations into a full-length recombinant β-spectrin transgene (codons 2157 and 2166, respectively) and produced transgenic flies, as previously described (13). Western blots of total proteins from the transgenic flies expressing each protein revealed robust expression of the Myc epitope-tagged products (Fig. 1, bottom, lanes 3 and 4). Both transgenes were tested for their ability to rescue the lethality of the βspecem6 mutation. Representative results are shown in Table 1. The rescue cross scheme (13) (described under “Experimental Procedures”) made use of a compound X chromosome in the female parent to force transmission of the X chromosome from fathers to sons. The male parent carried a lethal mutation in the β-spectrin locus on X (βspecem6), but these males survive due to the presence of a duplication of part of the X chromosome to chromosome 3 (including the wild type β-spectrin locus and the neighboring marker Bar, which has an easily scored dominant eye phenotype). The rescue cross strategy tests the ability of a mutant transgene to functionally replace the duplication chromosome, thus allowing males that carry a lethal mutation in the endogenous β-spectrin gene to survive. These flies are recognized by the absence of the Bar eye marker. A control wild type transgene (KW3A) yields a net male progeny ratio of 2:1 Bar/non-Bar eye adults (Table 1). Crosses with transgenes that lack function yield only Bar-eyed progeny (13). Both the K8Q and the K17Q mutant transgenes also yielded male progeny ratios approaching 2:1, indicating that they were capable of efficiently rescuing the lethal β-spectrin mutation. Thus, loss of lipid binding activity had no significant effect on the essential function of β-spectrin in vivo.

TABLE 1.

β-Spectrin mutant rescue with transgenes carrying PH domain point mutations

| Total females | Male siblings | Rescue males | Total progeny | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control KW3A | 86 | 57 | 27 | 170 |

| K8Q PH | 91 | 84 | 47 | 222 |

| K17Q PH | 60 | 46 | 17 | 123 |

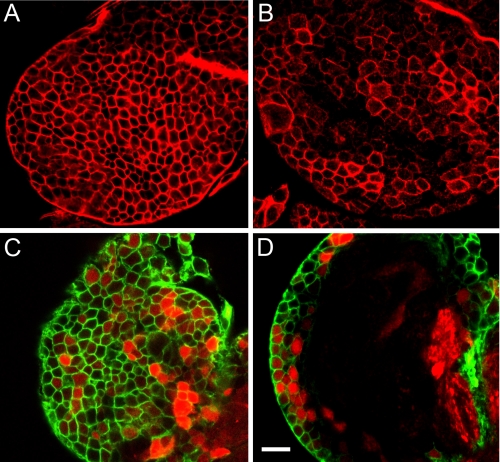

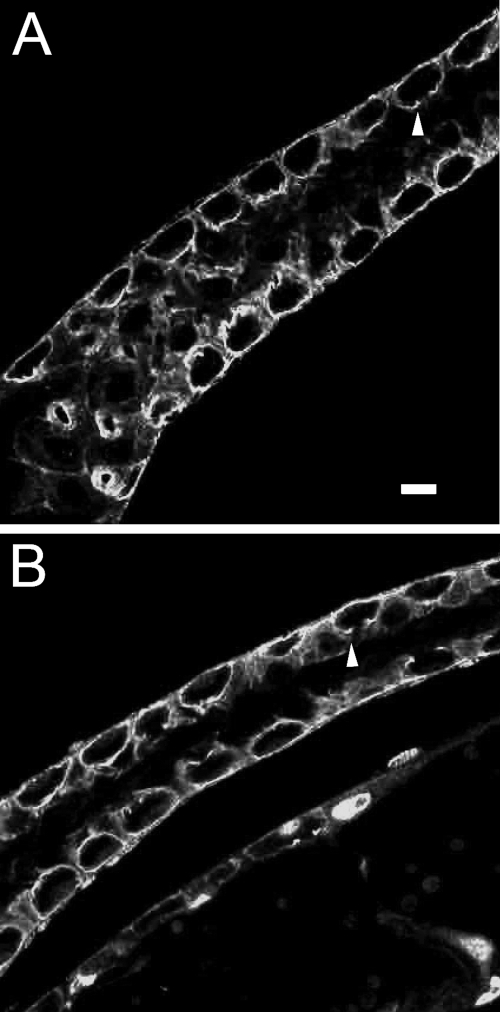

Since it was also formally possible that the mutant transgenes could rescue the lethality of the β-spectrin mutation but not restore the ability of the protein to target correctly in copper cells, we also examined the distribution of the transgene products in copper cells from rescued larvae (Fig. 6). Both proteins exhibited complete rescue of basolateral spectrin targeting (arrowheads) in copper cells. These results indicate that phosphoinositide binding activity is dispensable for spectrin function and that an activity other than lipid binding is likely to be responsible for PH domain-dependent targeting of spectrin to the plasma membrane in copper cells.

FIGURE 6.

Transgenes carrying point mutations in the PH domain are correctly targeted in copper cells. Dissected midguts from rescue larvae expressing PH domain point mutant transgenes (A, K8Q; B, K17Q) were stained with antibody against the Myc epitope tag in a background lacking endogenous wild type β-spectrin. Both transgene products were efficiently recruited to the basolateral domain of copper cells (arrowheads). Bar, 10 μm.

In parallel studies, we compared the distribution of PtdIns(4,5)P2 to αβ-spectrin in copper cells and salivary gland cells. A previously described GFP reporter fused to the PH domain of PLCγ was expressed as a UAS transgene (22). This reporter efficiently labels plasma membrane domains that are enriched with PtdIns(4,5)P2 (22). In midgut copper cells, the reporter was highly enriched in the apical membrane domain (Fig. 7, A and C, arrow), where it codistributed with αβH-spectrin (Fig. 7B, arrow). In contrast, a relatively weak signal was detected in the basolateral domain, where all of the αβ isoform of spectrin is found (arrowhead; compare with Fig. 6A). Similarly, the PLC-PH-GFP reporter most strongly stained the apical membrane domain of salivary gland epithelium (Fig. 7D, arrow), with a much weaker signal in the basolateral αβ-spectrin-containing region of the plasma membrane. Thus, the PtdIns(4,5)P2 distribution observed in vivo does not match the expectation of a cue that could direct basolateral assembly of αβ-spectrin in copper cells or the salivary gland.

FIGURE 7.

Comparison of the distribution of PtdIns(4,5)P2 to spectrin in vivo. A transgene encoding the PLCγ-PH domain fused to GFP was used to characterize the distribution of PtdIns(4,5)P2 in copper cells (A-C and E-G) and salivary gland (D and H). PLCγ-PH-GFP (A, C, and D) was most concentrated in the apical membrane domains of both cell types (arrows) with significantly less staining in the basolateral region (arrowhead). In copper cells, the majority of PLCγ-PH-GFP staining codistributed with αβH spectrin in the apical domain (arrow) rather than with αβ-spectrin in the basolateral domain (arrowhead in B; stained with anti-α-spectrin antibody). A reporter consisting of the Myc epitope-tagged PH domain of β-spectrin was also expressed in copper cells (E and G) and salivary gland (H). The spectrin PH domain reporter was primarily targeted to the apical membrane domain (arrows), suggesting that the lipid binding activity of the PH domain was capable of targeting assembly but that normally other signals in authentic spectrin mediate basolateral assembly. Scribble staining marks the apicolateral septate junction of copper cells in F. Bars, 10 μm.

We also examined the distribution of a Myc-tagged reporter corresponding to the PH domain of β-spectrin as a UAS transgene product in vivo (21). The β-spectrin PH domain accumulated at the apical membrane of copper cells (Fig. 7, E and G, arrow) and salivary gland cells (Fig. 7H, arrow) in a pattern that matched the distribution of PtdIns(4,5)P2. Thus, the β-spectrin PH domain reporter closely paralleled the distribution of the PLC-γ PH domain reporter but not the distribution of endogenous αβ-spectrin. It appears that in the absence of a competing cue, the lipid binding activity of the spectrin PH domain was sufficient to guide its polarized assembly, albeit in the wrong place.

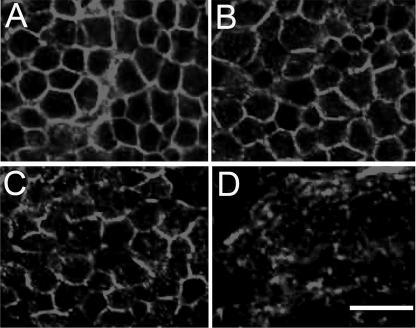

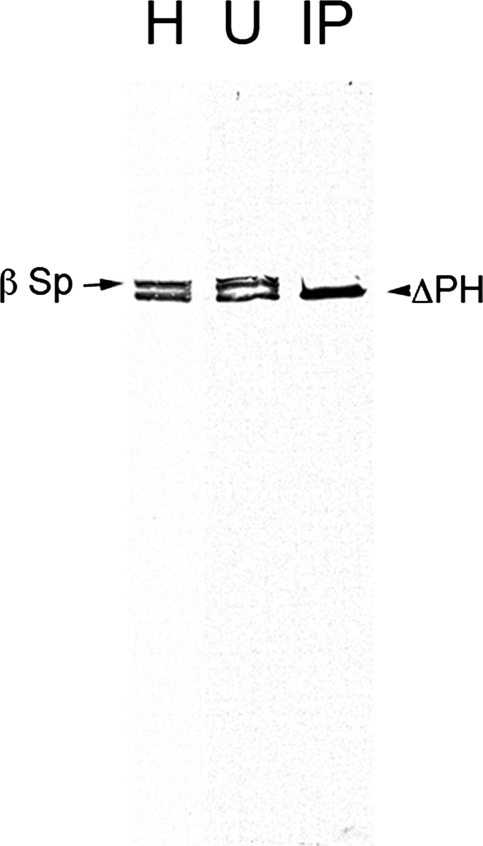

Previous studies of the β-spectrin PH domain focused primarily on its membrane binding activity. We originally observed that the truncated ΔPH product exhibited partial localization when it was expressed in the presence of wild type β-spectrin (13). Thus, we were interested to know if the partial localization could be due to formation of mixed tetramers containing both wild type and ΔPH β-spectrin. Western blots with anti-β-spectrin antibody indicate that the two spectrins are expressed at similar levels in the transgenic embryos used in these experiments (Fig. 8, lane 1). Immunoprecipitation of the Myc-tagged ΔPH transgene product under nondenaturing conditions (16) using anti-Myc antibody efficiently recovered the truncated ΔPH product (arrowhead) but not the endogenous full-length β-spectrin (lane 3, arrow), which was still present in the unbound fraction (lane 2). If the ΔPH protein were capable of forming tetramers, we would have expected to recover a significant amount of endogenous wild type β-spectrin (∼50% of ΔPH) in the immunoprecipitates. Given that the reactions were carried out under nondenaturing conditions, it appears that the ΔPH truncation has an unexpected effect on the ability of the modified protein to form stable tetramers.

FIGURE 8.

Immunoprecipitation of ΔPH spectrin from embryo homogenates reveals a defect in tetramer formation. Transgenic 12-24-h fly embryos that were homozygous for the ΔPH transgene 15-5 and endogenous wild type β-spectrin were homogenized and centrifuged to produce a clear supernatant. The Myc-tagged transgene product was immunoprecipitated using anti-Myc antibody and Pansorbin. Fractions were analyzed on Western blots probed with rabbit-anti-β-spectrin to detect both the recombinant transgene product and endogenous β-spectrin. The two proteins were present at comparable levels in the embryo homogenate (lane H), but only the truncated recombinant product was efficiently precipitated (lane IP), and the full-length β-spectrin remained in the unbound fraction (lane U).

DISCUSSION

Recent studies of spectrin and ankyrin in polarized cells from vertebrates and invertebrates have produced conflicting results concerning the order of events in their assembly. Studies from Drosophila suggest that spectrin is upstream of ankyrin in the assembly pathway (13-15), whereas studies in mice suggest that ankyrin is upstream of spectrin (10, 11). The results of the present study shed new light on this apparent discrepancy. There is a remarkable complexity in the mechanisms that control spectrin assembly in Drosophila in vivo. Given the conservation between vertebrate and invertebrate spectrins, it seems likely that a similar complexity will emerge as spectrin and ankyrin assembly mechanisms are characterized in a broader range of mammalian cell types.

The present results indicate that there are at least three distinct mechanisms of spectrin assembly in Drosophila that differ from the mechanism described so far in mice (Fig. 9). The carboxyl-terminal PH domain is required for assembly in midgut copper cells (Fig. 9, A), either the ankyrin-binding domain or the PH domain is required for assembly in larval brain (B), and an altogether different site is required for assembly in the salivary gland (C). In mouse neurons and cardiomyocytes, spectrin assembly appears to strictly depend on binding to ankyrin (D). There does not appear to be a redundant alternative pathway operating through the PH domain in mice, since no residual spectrin assembly was observed when the interaction between spectrin and ankyrin was blocked (11). With four distinct mechanisms operating in the cells that have been characterized so far, it seems likely that even more mechanisms remain to be discovered. In light of this unexpected complexity, it will be important to experimentally determine which pathway is operating in future studies of other cell types.

FIGURE 9.

The distribution of spectrin in vivo is controlled by multiple factors acting at different sites in the spectrin molecule. Basolateral assembly of spectrin in the copper cell depends on the PH domain (A). Targeting in larval neurons can be mediated by either the PH domain or the ankyrin-binding domain (B). Targeting in the salivary gland does not require either of those sites (C) but instead is likely to require a site in the NH2-terminal part of the molecule. Further complexity is indicated by results in mammalian neurons and heart showing that ankyrin can provide the primary cue for spectrin assembly (D), independently of the PH domain. E, the head to head interaction of spectrin dimers to form tetramers (top) is mediated by partial repeats near the COOH terminus of β-spectrin and the NH2 terminus of α-spectrin (middle) that form a complete triple barrel structural module. Recent models place the PH domain, which resides downstream of the partial repeat in β-spectrin, as a projection away from the partial repeat so as not to interfere with tetramer formation. However, current evidence that tetramers do not form in the absence of the PH domain raises the possibility that the PH domain has a stabilizing role at the tetramer formation site (bottom).

It is not yet clear whether multiple pathways might be operating within a single cell to mediate targeting of spectrin to different plasma membrane subdomains. So far, the results indicate an all-or-none effect where spectrin assembles within multiple discrete domains or not at all. For example, the PH domain is required in copper cells to recruit spectrin to the basal domain (where it contacts a basement membrane); to the septate junction, which forms an apicolateral adhesive complex between neighboring cells; and to the subseptate junction lateral domain found between the other two domains. The simplest explanation is that the PH domain mediates spectrin recruitment by a single class of receptor that is present in all three membrane domains.

In mammals, the tight junction has been proposed to form a “fence” that blocks diffusion of membrane proteins between the apical and basolateral domains of the plasma membrane (30). If there is a spectrin receptor in the basolateral domain, then one might imagine that the receptor could be restricted by the fence function of the tight junction, thus preventing αβ-spectrin from assembling at the apical domain. In invertebrates, the septate junction fulfills the role of the tight junction as a permeability barrier in the apicolateral region of the lateral plasma membrane (31). However, as seen in the experiments shown here, the septate junction is a relatively broad zone, occupying about one-third of the lateral domain. Given that spectrin is found throughout the septate junction, it seems unlikely that its putative receptor(s) is corralled by the junction. We speculate instead that the receptor is active throughout each of the domains in which spectrin is observed to assemble, including the septate junction.

We initially speculated that the PH domain and ankyrin-binding domain of β-spectrin could have a redundant role in targeting spectrin to the basolateral domain of salivary gland cells, since neither single mutation appeared to have an effect on assembly. The lack of effect of a doubly mutant spectrin lacking both sites suggests that the cue for assembly is received elsewhere in the β-spectrin molecule. The cue is not likely to reside in α-spectrin, since both spectrin isoforms share the same α-subunit in Drosophila but have nonoverlapping distributions in polarized cells (32). For the same reason, it seems unlikely that the actin binding of activity is involved in polarized assembly, since both spectrin isoforms share that activity and neither protein co-distributes with bulk filamentous actin in cells. Previous biochemical studies of mammalian spectrin identified an ankyrin-independent membrane binding site near the NH2 terminus of β-spectrin (33, 34), making this region a promising target for further transgene studies in Drosophila. However, the results at this point only exclude ankyrin-binding repeat 15 and the PH domain, making all other regions of the spectrin molecule viable candidates as recruitment sites in the salivary gland.

The redundant mechanism that we originally hypothesized for the salivary gland did turn out to explain the behavior of spectrin in neurons in the developing larval brain. We had previously noticed a striking spectrin staining pattern in the cortex of the larval brain. Here we observed that the pattern was eliminated in mutants expressing the double mutant transgene that lacked ankyrin binding activity and the PH domain. Each single mutant exhibited most or all of the wild type pattern, suggesting that either site was capable of directing spectrin assembly. We were not able to detect any polarity of spectrin assembly in these cells. Instead, we simply observed that spectrin was either present on the plasma membrane or not. We originally considered the possibility that the spectrin staining pattern corresponds to contacts between neurons and glia. However, experiments with the glial reporter Repo-Gal4 only produced sparse patterns of stained cells that could not account for the closely packed staining patterns we observed with spectrin antibodies or elav-Gal4 reporters (data not shown). A recent study found that elav-Gal4 is transiently expressed in glial cells during embryonic development (35). However, protein products were no longer detected by the end of embryogenesis, making it unlikely that the expression pattern observed here in larval brain was due to the glial components of elav expression. Therefore, we conclude that the spectrin staining pattern observed at this stage in development corresponds primarily to contacts between neighboring neurons.

Biological Properties of the PH Domain—Our experimental approach provided the first opportunity to directly test the contribution of the PH domain to spectrin assembly and function in vivo. The in vitro lipid binding data described in previous studies (28, 29) along with the plasma membrane targeting activity of a spectrin PH domain-GFP reporter (36) led to the logical conclusion that the PH domain could mediate lipid-dependent targeting activity in vivo. The results here establish that the PtdIns(4,5)P2 binding activity of the PH domain is conserved in Drosophila, that the PH domain prefers this lipid over PtdIns(3,4,5)P3, and that a β-spectrin PH domain reporter codistributes with PtdIns(4,5)P2 in vivo. However, lipid binding activity was not responsible for spectrin targeting or for its essential function, suggesting that something besides loss of lipid binding activity explains the detrimental effects of the PH domain truncation.

As we were completing these studies, it became apparent that phosphoinositides are polarized in epithelial cells and that their polarity has important ramifications for the maintenance of polarity. For example, PtdIns(4,5)P2 is normally present in the apical domain of polarized Madin-Darby canine kidney cells, and when it is exogenously added to the basolateral domain, that domain acquires characteristics of the apical domain (37). Similarly, PtdIns(3,4,5)P3 is normally concentrated in the basolateral compartment of Madin-Darby canine kidney cells, and transplanting it to the apical domain confers basolateral character on the apical domain (38). Studies with a GFP reporter that specifically binds to PtdIns(4,5)P2 established that the asymmetric apical distribution of this lipid is conserved in Drosophila epithelia (22). Therefore, spectrin does not normally codistribute with the bulk of PtdIns(4,5)P2 in vivo. Our finding that loss of lipid binding activity had no detectable effect on spectrin targeting or function provides compelling proof that something other than phosphoinositide binding activity is responsible for spectrin targeting in vivo.

Why is the PH domain reporter targeted to the PIP2-rich apical domain of epithelia when the native spectrin molecule is exclusively targeted to the basolateral domain? One intriguing answer to this question emerged from the behavior of the ΔPH transgene product in immunoprecipitation experiments. The rationale for the experiment was to ask if the partial localization of the ΔPH protein in cells from heterozygotes that also expressed wild type β-spectrin (13) was due to mixed tetramer formation. The experiment was made possible, because 1) the mutant and wild type proteins differ sufficiently in size to be resolved on Western blots, and 2) the transgene product could be selectively immunoprecipitated using Myc tag antibody. The inability to detect endogenous full-length β-spectrin co-precipitating with the ΔPH product in this assay suggests that the truncation impairs stable tetramer formation.

Tetramer formation is thought to occur through interactions between partial structural repeats in the α and β subunits of spectrin (39) (Fig. 9E). Much of the spectrin molecule consists of triple barrel α-helical repeats (40). Tetramer formation proceeds through formation of a complete structural repeat from partial repeats at the ends of α- and β-spectrin. Two barrels come from β-spectrin, and a third barrel comes from the NH2 terminus of α-spectrin (Fig. 9E, middle). Most β-spectrin isoforms have the additional PH domain sequence downstream of the partial spectrin repeat (41). To accommodate models of the tetramer, the PH domain has typically been drawn as a projection away from the long axis of the tetramer (e.g. see Refs. 7, 21, and 42) (Fig. 9E, top). However, there is no direct evidence to support that structural model. Instead, based on the data shown here, we speculate that the PH domain is more intimately associated with the partial repeats at the tetramer formation site (Fig. 9E, bottom). That association may help stabilize the tetramer, preventing its dissociation into dimers.

Tetramer stability is one of the most conspicuous differences between erythrocyte and nonerythroid spectrins. Erythrocyte spectrin spontaneously dissociates into dimers at room temperature, whereas most other spectrins (including Drosophila spectrin) remain in a tetrameric state. A recent study of this difference in stability identified sequence divergence in the α subunit as one cause of tetramer lability (43). The authors speculate that sequence divergence at this site contributed to neofunctionalization of diverging genes after duplication of an ancestral gene early in vertebrate spectrin evolution. Loss of the PH domain by the β subunit in the course of erythroid spectrin evolution may represent another neofunctionalization that helps to explain differences in tetramer stability between isoforms. Interestingly, the domain structure of the ΔPH transgene (Fig. 1) is exactly the same as human erythrocyte β-spectrin, with only ∼50 amino acids between partial repeat 17 and the stop codon.

The proposed involvement of the PH domain in tetramer formation also fits well with two other results from the current study. First, although the PH domain from spectrin interacts with PIP2 in vitro, and the isolated PH domain is targeted to a PIP2-rich membrane domain in vivo, native spectrin tetramers do not appear to interact with PIP2. This observation may be explained if the lipid-binding site in the isolated PH domain becomes masked when it forms other protein interactions in the native spectrin tetramer (Fig. 9E, bottom). Second, the PH domain is clearly required for spectrin targeting in some cells, yet the isolated PH domain does not appear to respond to the cue for basolateral spectrin assembly (Fig. 7). That observation would be explained if a new binding site is formed by the interaction of the PH domain with another site in the spectrin tetramer. Consequently, the PH domain would only be active in basolateral targeting in the context of the native tetramer.

Drosophila has proven to be a valuable model system in which to dissect the protein interactions that explain spectrin targeting and function. The modified transgene approach has uncovered functional sites that have important roles in Drosophila, and by virtue of their conservation they are likely to be important in mammals as well. Continued application of the transgene rescue strategy should allow the identification of the membrane binding sites that explain polarized spectrin recruitment in the salivary gland. Ongoing genetic screens aimed at identifying new mutations affecting spectrin function will make it possible to test the hypothesis that the PH domain of β-spectrin contributes to spectrin tetramer formation as well as polarized assembly. For example, we predict that mutations in the PH domain will be found that perturb spectrin targeting without affecting its lipid binding activity. Characterization of such mutants with respect to their ability to form stable spectrin tetramers is expected to provide fundamental new insights into the structure and activity of spectrins. Another important issue to address using this approach is whether or not any of the activities ascribed to the PH domain here involve the ∼30 amino acid residues found between the PH domain and the carboxyl terminus of β-spectrin.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Srilakshmi Dhulipala for technical assistance, Franck Pichaud for providing the PLCγ-PH-GFP reporter, Graham Thomas for providing the β-spectrin PH domain reporter, Chris Doe for providing Scribble antibody, and Volker Hartenstein and Christian Klambt for valuable discussions regarding the larval brain staining patterns.

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants GM49301 (to R. R. D.) and GM68849 (to W. C.). The costs of publication of this article were defrayed in part by the payment of page charges. This article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. Section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

The on-line version of this article (available at http://www.jbc.org) contains supplemental Fig. S1.

Footnotes

The abbreviations used are: PH, pleckstrin homology; PtdIns(4,5)P2 or PIP2, phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate; PtdIns(3,4,5)P3, phosphatidylinositol-3,4,5-trisphosphate; PLC, phospholipase C; POPC, 1-palmitoyl-2-oleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine; POPE, 1-palmitoyl-2-oleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphoethanolamine; POPS, 1-palmitoyl-2-oleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphoserine; CHAPS, 3-[3-cholamidopropyl)dimethylammonio]-1-propanesulfonic acid; SPR, surface plasmon resonance; GPIns(4,5)P2, l-α glycerophospho-d-myo- inositol 4,5-bisphosphate; UAS, upstream activation sequence; GST, glutathione S-transferase; GFP, green fluorescent protein; TRITC, tetramethylrhodamine isothiocyanate.

References

- 1.Lux, S. E., and Palek, J. (1995) in Blood: Principles and Practice of Hematology (Handin, R. I., Lux, S. E., and Stossel, T. P., eds) pp. 1701-1818, J.B. Lippincott Co., Philadelphia

- 2.Lee, J., Coyne, R., Dubreuil, R. R., Goldstein, L. S. B., and Branton, D. (1993) J. Cell Biol. 123 1797-1809 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dubreuil, R. R., Wang, P., Dahl, S. C., Lee, J. K., and Goldstein, L. S. B. (2000) J. Cell Biol. 149 647-656 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lacas-Gervais, S., Guo, J., Strenzke, N., Scarfone, E., Kolpe, M., Jahkel, M., DeCamilli, P., Moser, T., Rasband, M. N., and Solimena, M. (2004) J. Cell Biol. 166 983-990 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yang, Y., Lacas-Gervais, S., Morest, D. K., Solimena, M., and Rasband, M. N. (2004) J. Neurosci. 24 7230-7240 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hammarlund, M., Jorgensen, E. M., and Bastiani, M. J. (2007) J. Cell Biol. 176 269-275 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dubreuil, R. R. (2006) J. Membr. Biol. 211 151-161 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kizhatil, K., and Bennett, V. (2004) J. Biol. Chem. 279 16706-16714 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kizhatil, K., Yoon, W., Mohler, P. J., Davis, L. H., Hoffman, J. A., and Bennett, V. (2007) J. Biol. Chem. 282 2029-2037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mohler, P. J., Yoon, W., and Bennett, V. (2004) J. Biol. Chem. 279 40185-40193 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yang, Y., Ogawa, Y., Hedstrom, K. L., and Rasband, M. N. (2007) J. Cell Biol. 176 509-519 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sherman, D. L., Tait, S., Melrose, S., Johnson, R., Zonta, B., Court, F. A., Macklin, W. B., Meek, S., Smith, A. J. H., Cottrell, D. F., and Brophy, P. J. (2005) Neuron 48 737-742 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Das, A., Base, C., Dhulipala, S., and Dubreuil, R. R. (2006) J. Cell Biol. 175 325-335 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pielage, J., Fetter, R. D., and Davis, G. W. (2006) J. Cell Biol. 175 491-503 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Garbe, D. S., Das, A., Dubreuil, R. R., and Bashaw, G. J. (2007) Development 134 273-284 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dubreuil, R. R., and Yu, J. (1994) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 91 10285-10289 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dubreuil, R., Byers, T. J., Branton, D., Goldstein, L. S. B., and Kiehart, D. P. (1987) J. Cell Biol. 105 2095-2102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Evan, G. I., Lewis, G. K., Ramsay, G., and Bishop, J. M. (1985) Mol. Cell. Biol. 5 3610-3616 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Albertson, R., and Doe, C. Q. (2003) Nat. Cell Biol. 5 166-170 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Phillips, M. D., and Thomas, G. H. (2006) J. Cell Sci. 119 1361-1370 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Williams, J. A., MacIver, B., Klipfell, A. A., and Thomas, G. H. (2004) J. Cell Sci. 117 771-782 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pinal, N., Goberdhan, D. C. I., Collinson, L., Fujita, V., Cox, I. M., Wilson, C., and Pichaud, F. (2006) Curr. Biol. 16 140-149 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hulsmeier, J., Pielage, J., Rickert, C., Technau, G. M., Klambt, C., and Stork, T. (2007) Development 134 713-722 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Stahelin, R. V., and Cho, W. (2001) Biochemistry 40 4672-4678 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cho, W., Bittova, L., and Stahelin, R. V. (2001) Anal. Biochem. 296 153-161 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Stahelin, R. V., Karathanassis, D., Bruzik, K. S., Waterfield, M. D., Bravo, J., Williams, R. L., and Cho, W. (2006) J. Biol. Chem. 281 39396-39406 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lemmon, M. A., and Ferguson, K. M. (2000) Biochem. J. 350 1-18 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhang, P., Talluri, S., Deng, H., Branton, D., and Wagner, G. (1995) Structure 3 1185-1195 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hyvonen, M., Macias, M. J., Nilges, M., Oschkinat, H., Saraste, M., and Wilmanns, M. (1995) EMBO J. 14 4676-4685 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gumbiner, B., and Louvard, D. (1985) Trends Biochem. Sci. 10 435-438 [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tepass, U., and Hartenstein, V. (1994) Dev. Biol. 161 563-596 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dubreuil, R. R., Maddux, P. B., Grushko, T., and MacVicar, G. R. (1997) Mol. Biol. Cell 8 1933-1942 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lombardo, C. R., Weed, S. A., Kennedy, S. P., Forget, B. G., and Morrow, J. S. (1994) J. Biol. Chem. 269 29212-29219 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Davis, L. H., and Bennett, V. (1994) J. Biol. Chem. 269 4409-4416 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Berger, C., Renner, S., Luer, K., and Technau, G. M. (2007) Dev. Dyn. 236 3562-3568 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wang, D.-S., Miller, R., Shaw, R., and Shaw, G. (1996) Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 225 420-426 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Martin-Belmonte, F., Gassama, A., Datta, A., Yu, W., Rescher, U., Gerke, V., and Mostov, K. (2007) Cell 128 383-397 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gassama-Diagne, A., Yu, W., Beest, M. t., Martin-Belmonte, F., Kierbel, A., Engel, J., and Mostov, K. (2006) Nat. Cell Biol. 8 963-970 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tse, W. T., Lecomte, M.C., Costa, F.F., Garbarz, M., Feo, C., Boivin, P., Dhermy, D., and Forget, B. G. (1990) J. Clin. Invest. 86 909-916 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yan, Y., Winograd, E., Viel, A., Cronin, T., Harrison, S. C., and Branton, D. (1993) Science 262 2027-2030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tse, W. T., Tang, J., Jin, O., Korsgren, C., John, K. M., Kung, A. L., Gwynn, B., Peters, L. L., and Lux, S. E. (2001) J. Biol. Chem. 276 23974-23985 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bennett, V., and Baines, A. J. (2001) Physiol. Rev. 81 1353-1388 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Salomao, M., An, X., Guo, X., Gratzer, W. B., Mohandas, N., and Baines, A. J. (2006) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 103 643-648 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.