Abstract

Cry proteins produced by Bacillus thuringiensis are selective biodegradable insecticides used increasingly in bacterial insecticides and transgenic plants as alternatives to synthetic chemical insecticides. However, the potential for development of resistance and cross-resistance in target insect populations to Cry proteins used alone or in combination threatens the more widespread use of this novel pest control technology. Here we show that high levels of resistance to CryIV proteins in larvae of the mosquito, Culex quinquefasciatus, can be suppressed or reduced markedly by combining these proteins with sublethal quantities of CytA, a cytolytic endotoxin of B. thuringiensis. Resistance at the LC95 level of 127-fold for a combination of three CryIV toxins (CryIVA, B, and D), resulting from 60 generations of continuous selection, was completely suppressed by combining sporulated powders of CytA in a 1:3 ratio with sporulated powders of a CryIVA, CryIVB, and CryIVD strain. Combining the CytA strain with a CryIVA and CryIVB strain also completely suppressed mosquito resistance of 217-fold to the latter toxins at the LC95 level, whereas combination of CytA with CryIVD reduced resistance in a CryIVD-selected mosquito strain from greater than 1,000-fold to less than 8-fold. The CytA/CryIV model provides a potential molecular genetic strategy for engineering resistance management for Cry proteins directly into bacterial insecticides and transgenic plants.

Pressure to eliminate synthetic chemical insecticides from insect control programs continues to mount due to their detrimental effects on nontarget organisms, the propensity for pests to develop insecticide resistance, and concern that continued use of these insecticides will further pollute the environment, particularly food and water supplies, with harmful chemicals (1). Among the best alternatives for chemical insecticides are the insecticidal Cry and Cyt proteins produced by Bacillus thuringiensis (2). Shortly after ingestion, these proteins bind to and lyse insect midgut epithelial cells (3). They are highly specific in comparison to chemical insecticides and degrade in the environment days after use. Several subspecies of B. thuringiensis are available commercially as bacterial insecticides, and their use is increasing (4). These include B. t. subsp. kurstaki and B. t. subsp. aizawai used to control many caterpillar pests, B. t. subsp. morrisoni (strain tenebrionis) used to control coleopterous pests such as the Colorado potato beetle, and B. t. subsp. israelensis used to control larvae of nuisance and vector mosquitoes and blackflies (4–7). In addition, recombinant DNA technology has been used to transform plants with cry genes yielding insect-resistant transgenic crop plants, including cotton (8), corn (9), potatoes (10), and tomatoes (11). B. thuringiensis-transgenic cotton, corn, and potatoes already are produced commercially in the United States.

Despite this promise, resistance to B. thuringiensis, and specifically to Cry proteins, has been reported in insect pests. For example, under laboratory selection, populations of the Indianmeal moth, Plodia interpunctella (12, 13) in the United States developed high levels of resistance, ranging from 75- to 250-fold, to CryIA(a), CryIA(b), CryIA(c), CryIIA, CryIB, and CryIC. Moreover, similar and even higher levels of resistance to commercial B. thuringiensis products have been reported in field populations of the diamondback moth, Plutella xylostella, in Hawaii, Florida, Japan, the Philippines, and several other countries (14–20). In Hawaiian populations of P. xylostella, resistance extended to at least six toxins, CryIA(a), CryIA(b), CryIA(c), CryIF, CryIJ, and HO4, a CryIC-CryIA(b) chimera (14–17), whereas certain Floridian populations (19, 20) were shown to be resistant to CryIA(a), CryIA(b), and CryIA(c). The toxicity of B. thuringiensis against some of these resistant insect strains was restored by using another Cry protein to which cross-resistance was limited. Larvae of CryIA(b)-resistant P. xylostella, for instance, were less resistant to the more distantly related CryIB or CryIC proteins (21, 22). Although rotation of Cry proteins represents a potentially useful tactic for managing resistance to individual Cry proteins, cross-resistance remains a potential major problem, as most Cry proteins are related. In fact, high levels of cross-resistance among Cry proteins in the tobacco budworm, Heliothis virescens, already have been demonstrated in laboratory studies (23, 24).

In contrast to the development of Cry resistance in field populations of the diamondback moth, no confirmed resistance to B. t. subsp. israelensis has been reported in field populations of mosquitoes, even in areas where they have been treated intensively (25, 26). Moreover, only low levels of resistance have been reported in laboratory selections of these insects (27, 28). This subspecies of B. thuringiensis differs from most others in that it produces a unique cytolytic protein, CytA, along with three Cry proteins, CryIVA, CryIVB, and CryIVD (5, 29). CytA is a highly hydrophobic endotoxin that shares no sequence homology with Cry proteins and appears to have a different mode of action. Whereas Cry proteins initially bind to glycoproteins on the microvillar membrane (30), CytA’s primary affinity is for the lipid component of the membrane, specifically for unsaturated fatty acids (31). In addition to being toxic, CytA synergizes the toxicity of CryIV proteins (32–35). Studies of CryIVD and CytA, for example, show that mixtures containing as little as 10% CytA are 3- to 5-fold more toxic than CryIVD alone (33, 34).

CytA’s unique mode of action and capacity to interact synergistically with CryIV proteins indicated that it might be the key protein accounting for the inability of mosquitoes to quickly develop resistance to B. t. subsp. israelensis. Moreover, indirect evidence from selection experiments (28) and cross-resistance studies (36) suggested that CytA in combination with CryIV toxins could suppress resistance to CryIV proteins in mosquitoes. We tested the latter hypothesis and show here that combination of sublethal quantities of CytA with CryIV proteins enables these proteins to suppress or markedly reduce high levels of CryIV resistance in the mosquito Culex quinquefasciatus. These results, and the evidence that CytA delays the development of resistance to CryIV proteins (28), suggest that Cyt proteins used in combination with Cry proteins could provide an alternative molecular strategy for managing resistance to some Cry proteins.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Experimental Design.

Our experiments were designed primarily to determine whether CytA in combination with CryIV proteins could suppress resistance in different CryIV-resistant strains of C. quinquefasciatus. For this purpose, we used recombinant sporogenic strains of B. thuringiensis, which produced CytA or CryIV proteins, the latter being CryIVD alone, CryIVA+CryIVB, or CryIVA+CryIVB+CryIVD, and tested these in bioassays alone or in combination, against fourth instars of resistant and control (nonselected) strains of C. quinquefasciatus. This design also allowed the data to be analyzed for synergism between CytA and the CryIV proteins against the different susceptible and resistant mosquito strains.

To establish whether any effects observed were due specifically to CytA, and not simply to adding an additional endotoxin to the mixture, toxicity was determined for mixtures of CytA or CryIVD with CryIVA+CryIVB against the mosquito strain resistant to the latter two CryIV toxins.

Mosquito Strains.

Four laboratory strains of C. quinquefasciatus were used in this study, one susceptible reference strain (CqSyn90) and three resistant strains derived from CqSyn90 through selection with various B. thuringiensis CryIV toxins (28). The strains and their resistance ratios (RR) at the LC95 level to the toxins used in their selection were as follows: (i) Cq4D, a strain >1,000-fold resistant to CryIVD; (ii) Cq4AB, a strain >217-fold resistant to CryIVA+CryIVB; and (iii) Cq4ABD, a strain 127-fold resistant to CryIVA+CryIVB+CryIVD.

CryIV and CytA B. thuringiensis Strains.

All toxin preparations consisted of sporulated, lyophilized powders of the B. thuringiensis strains. Four recombinant strains were used in the bioassays and/or selection of the mosquito strains. These were identified by the names of the toxin or toxin combination that each produced, respectively: (i) CryIVD, (ii) CryIVA+CryIVB, (iii) CryIVA+CryIVB+CryIVD, and (iv) CytA. The CryIVD powder was provided by S. S. Gill, University of California, Riverside. The strain used to produce this powder was constructed by transforming the acrystalliferous CryB strain of B. t. subsp. kurstaki with a plasmid that produced only CryIVD (37). The CryIVA+CryIVB and CryIVA+CryIVB+CryIVD powders were provided by A. Delécluse (Pasteur Institute, Paris, France) and used B. t. subsp. israelensis for toxin production (38, 39). The CytA powder was produced using the 4Q7 acrystalliferous strain of B. t. susbp. israelensis transformed with a plasmid that produced only the CytA endotoxin (40). Control host bacterial strains that lacked the toxins were not toxic to C. quinquefasciatus. The bacterial strain used to produce the CytA powders originated from same parental strain of B. t. subsp. israelensis as that used to produce the CryIVA+CryIVB and CryIVA+CryIVB+CryIVD toxins. Thus, it is unlikely that anything other than CytA accounted for the results obtained by combining the CytA powder with these CryIV powders. However, because the CryIVD strain used a B. t. subsp. kurstaki strain as a host cell, we cannot rule out this possibility.

Stock solutions were prepared by suspending each toxin powder in deionized water in 125-ml flasks containing glass beads to assist particle dispersion. Ten-fold dilutions were made from stocks, and all stocks and dilutions were kept frozen at −20°C when not in use. Tests determining the toxicity of CytA in combination with the CryIV powders used a mixture of the appropriate powders at a ratio (by weight) of 1:3. The quantity of CytA used in all combinations was sublethal, with the exception of the three highest concentrations tested in the CytA plus CryIVD combination, where the expected mortality would be from 2% to 16%.

Toxin Ratios.

In wild-type B. t. subsp. israelensis, the endotoxin parasporal body makes up approximately 30% of the dry weight of sporulated cells (33). Though the precise ratio of toxins within the parasporal body has not been determined, we estimated the approximate proportion of each based on SDS/PAGE analyses and electron microscopy (33) to be as follows: 40% CytA and 20% each of CryIVA, CryIVB, and CryIVD. This does not reflect molar ratios, however, as CytA (27.3 kDa) is less than half the mass of CryIVD (67 kDa) and less than one-fourth the mass of CryIVA (128 kDa) or CryIVB (134 kDa), although the proteolytically cleaved, activated forms of the latter two toxins are approximately 60 kDa. In the recombinant strains, the estimated percentage of the powder that was toxin, again based on SDS/PAGE analyses and electron microscopy (33, 38), was CytA strain (20%), CryIVD strain (10%), CryIVA+CryIVB strain (20%, with about equal ratios of each), and CryIVA+CryIVB+CryIVD strain (25%, with about equal ratios of each). Preliminary bioassays of the CytA powder demonstrated low toxicity to the nonselected and selected strains of C. quinquefasciatus, toxicity much lower than that of any of the CryIV powders against the nonselected mosquito strains. Thus, owing to the comparatively low toxicity of the CytA powder, and the difficulty of reproducing the precise ratio of CytA to CryIV toxins as it occurs in B. t. subsp. israelensis, we mixed the CytA powder with the other toxin mixtures at a 1:3 ratio. This resulted in estimated ratios of toxins on a weight basis in each of the CytA/CryIV toxin powder combinations as follows: CytA:CryIVD (2:3), CytA:CryIVA+CryIVB (1:3), and CytA:CryIVA+CryIVB+CryIVD (2:7.5). Therefore, the ratios of toxins in the CytA/CryIVA+CryIVB mixture and CytA/CryIVA+CryIVB+CryIVD mixture were in the range of those that occur in wild-type B. t. subsp. israelensis, whereas the ratio of CytA to CryIVD in the CytA/CryIVD combination was higher than in the wild-type species.

Selection for Resistance and Bioassays.

Selections for resistance and bioassays were performed as reported by Georghiou and Wirth (28) and are summarized briefly here. Approximately 1,000 early fourth instar larvae were placed in 1,000 ml of deionized water to which the appropriate concentration of toxin suspension was added. Surviving larvae were placed in fresh water after 24 hr. For generations 1–28, selection pressure was at 82–85% mortality, with each generation maintained separately. After 28 cycles of selection, generations were permitted to overlap, although selection pressure was continued and adjusted as needed to maintain resistance in the strains. Most of the present experiments were done at approximately generation 60.

Bioassays used groups of 20 early fourth instars from control or resistant strains of C. quinquefasciatus in 8-oz plastic cups containing 100 ml of deionized water. An appropriate amount of toxin suspension was mixed into the water, with at least five concentrations tested per assay, to yield 24-hr mortality ranging between 2% and 98%. Data were subjected to probit analysis using a program by Raymond (41). RRs were calculated by dividing the LC50 or LC95 value for the selected strain by that for the sensitive parental strain (CqSyn90). Dose–response data exhibiting plateaus were excluded from probit aanalysis. The plateau was reported as the average mortality observed within the respective range of concentrations.

Synergism.

Synergistic interactions between CytA and different CryIV proteins were evaluated and quantified as described by Tabashnik (42). The synergism factor (SF) is the ratio of the observed LC50 to the theoretical LC50 for the mixture of toxins, with the latter estimated from the equation below.

|

The LC50(m) is the theoretical LC50 of the mixture, ra and rb are the relative proportions by weight of the two toxin powders in the mixture, and LC50(a) and LC50(b) are the independent LC50 values for each respective toxin powder. In this equation, if a theoretical LC value was identical to the observed LC value, then the ratio of the observed value to the expected value would be 1, and the toxin interaction is simply additive. If the ratio was greater than 1, then the interaction was synergistic, whereas a ratio of less than 1 indicates an antagonistic interaction.

RESULTS

Toxicity of B. t. subsp. israelensis Strains.

The CytA powder was insecticidal but not highly toxic to the different strains of C. quinquefasciatus tested (Table 1). No significant difference was observed in the toxicity of CytA to the sensitive parental strain and the different strains resistant to CryIV toxins. All strains showed a linear response for mortality to increasing concentrations of toxin at lower concentrations and a plateau at 50–75% mortality at concentrations from 100 μg/ml to 1,000 μg/ml.

Table 1.

Toxicity and resistance ratios for CytA and CryIV proteins against control and selected strains of C. quinquefasciatus

| Strain | Toxin(s) tested | LC50, μg/ml | Fiducial limits | LC95, μg/ml | Fiducial limits | RR50 | RR95 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CqSyn90 | CytA | 25.6 | (7.5–90.3) | Plateau† | |||

| CqSyn90 | CryIVD | 0.741 | (0.647–0.844) | 3.56 | (2.84–4.78) | ||

| CqSyn90 | CryIVA+CryIVB | 0.272 | (0.149–0.493) | 3.15 | (1.04–9.65) | ||

| CqSyn90 | CryIVA+CryIVB+CryIVD | 0.0285 | (0.0247–0.0327) | 0.168 | (0.133–0.227) | ||

| Cq4D | CytA | 23.3 | (10.6–52.9) | Plateau† | |||

| Cq4D | CryIVD | >1,000 | Plateau* | >1,000 | >1,000 | ||

| Cq4AB | CytA | 21.8 | (18.2–27.1) | Plateau† | |||

| Cq4AB | CryIVA+CryIVB | 13.9 | (11.2–17.1) | 685.7 | (460–1,102) | 51.1 | 217.7 |

| Cq4ABD | CytA | 27.6 | (11.8–69.0) | Plateau† | |||

| Cq4ABD | CryIVA+CryIVB + CryIVD | 1.01 | (0.832–15.2) | 21.5 | (15.4–32.2) | 35.4 | 127.5 |

Plateau from 200–1,000 μg/ml with an average mortality of 31%.

Plateau from 100–1,000 μg/ml with average mortality of 63.5% for CqSyn90, 51.5% for Cq4D, 75.5% for Cq4AB, and 56.3% for Cq4ABD.

The LC50s and LC95s for the CryIV toxins, and relative RRs for the selected strains compared with concurrent bioassays on the sensitive parental strain are shown in Table 1. RRs at the LC95 ranged from >1,000 for the CryIVD selected strain to 217.7 and 127.5, respectively, for the strains selected for resistance to CryIVA+CryIVB or CryIVA+CryIVB+CryIVD.

Toxicity of CytA and CryIV Strains in Combination.

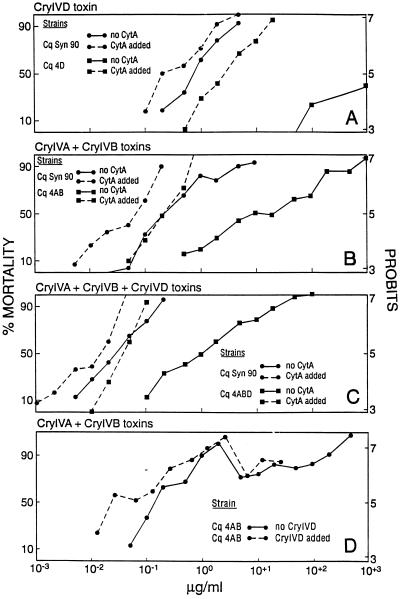

Combination of CytA with the different CryIV toxin preparations in a 1:3 ratio completely suppressed or markedly reduced CryIV resistance in the resistant mosquito strains (Tables 1 and 2, Fig. 1). Against Cq4AB, resistant to CryIVA+CryIVB, resistance was suppressed at the LC50 and higher levels (Tables 1 and 2, Fig. 1B), whereas against Cq4ABD, resistance was almost completely suppressed (Tables 1 and 2, Fig. 1C). Against Cq4D, combining CytA with CryIVD reduced resistance from greater than 1,000-fold to less than 8-fold at the LC50 level (Tables 1 and 2, Fig. 1A).

Table 2.

Synergism between CytA and CryIV toxins of Bti tested against larvae of control and selected strains of C. quinquefasciatus

| Toxins | Strain | LC50, μg/ml

|

SF | RR* | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Observed | FL | Theoretical | ||||

| [CryIVD]+CytA | CqSyn90 | 0.321 | (0.116–0.892) | 0.978 | 3.0 | |

| [CryIVD]+CytA | Cq4D | 5.25 | (4.42–6.18) | 87.3 | 16.6 | 7.1 |

| [CryIVA+CryIVB]+CytA | CqSyn90 | 0.0501 | (0.0262–0.0960) | 0.361 | 7.2 | |

| [CryIVA+CryIVB]+CytA | Cq4AB | 0.217 | (0.191–0.251) | 15.3 | 70.5 | 0.8 |

| [CryIVA+CryIVB+CryIVD] + CytA | CqSyn90 | 0.0141 | (0.0114–0.0184) | 0.0380 | 2.7 | |

| [CryIVA+CryIVB+CryIVD] + CytA | Cq4ABD | 0.0377 | (0.0339–0.0418) | 1.330 | 35.3 | 1.3 |

FL, fiducial limits.

LC50 of CryIV toxins + CytA on resistant strain/LC50 of unsynergized toxins on susceptible strain (data in Table 1).

Figure 1.

Dose–response regression lines for CryIV toxins in the presence or absence of CytA or CryIVD against nonselected and CryIV-resistant strains of the mosquito, C. quinquefasciatus. (A–C) Toxicity of the CryIV toxins indicated in the presence or absence of CytA against nonselected and different CryIV-resistant mosquito strains. CqSyn90 is the nonselected sensitive parental mosquito strain. Cq4D, Cq4AB, and Cq4ABD, are, respectively, the mosquito strains resistant to CryIVD, CryIVA+CryIVB, or CryIVA+CryIVB+CryIVD. (D) Dose–response regression lines illustrating the effect of combining CryIVD rather than CytA with CryIVA+CryIVB and assaying the mixture against the resistant strain Cq4AB. The slightly variation between the regression lines in B and D for the CryIVA+CryIVB combination against Cq4AB resulted from conducting the assays at slightly different generation times.

To determine whether the capacity to overcome resistance was due to CytA as opposed to simply addition of another endotoxin, we compared the effect of adding CytA versus CryIVD to CryIVA+CryIVB and tested these mixtures against Cq4AB. The results, illustrated in Fig. 1 B and D, show that the CytA+CryIVA+CryIVB mixture suppressed resistance completely, whereas resistance remained essentially unchanged when CryIVD was substituted for CytA.

CytA/CryIV Synergism and Resistance.

It is well established that synergism occurs to varying degrees between the CytA and CryIV toxins (32–35, 42). Thus, the high toxicity of the CytA/CryIV combinations to resistant mosquitoes suggested that synergism between CytA and CryIV proteins accounted at least in part for these high toxicity levels. To test this possibility, we analyzed the toxicity data for synergistic interactions between CytA and CryIV toxins against both the sensitive CqSyn90 strain and the resistant mosquito strains. This analysis showed that there was significant synergism between CytA and the CryIV toxins on both the sensitive strain and the CryIV-resistant strains (Table 2). Moreover, the SF values obtained in all the combinations tested against the resistant strains were higher than for the nonselected strains, thereby demonstrating the significance of synergism between CytA and CryIV proteins in suppressing resistance. The highest SF value was observed in the Cq4AB resistant strain, where the SF for the CytA plus CryIVA+CryIVB combination against the reference CqSyn90 strain was 7.2-fold at the LC50 level, but 70.5 for the resistant strain. Smaller, but significant, increases in the SF value also were obtained for Cq4D, where the SF values for the CytA+CryIVD combination at the LC50 level were 3.0 for the CqSyn90 strain and 16.6 for Cq4D. When CytA was combined with CryIVA+CryIVB+CryIVD, the SF values at the LC50 levels were 2.7 for the reference strain but 35.3-fold for the Cq4ABD selected strain. (Table 2).

DISCUSSION

In this study, we have shown that a CytA powder of moderate toxicity was equally toxic to a nonselected strain of C. quinquefasciatus and three highly resistant strains of this species selected for resistance to CryIV toxins alone or in combination. Of greater relevance to Cry resistance, we have shown that when the CytA powder was mixed at sublethal concentrations with CryIV proteins, CryIV resistance was completely suppressed at the LC95 level in mosquito strains resistant to the combinations of CryIVA and CryIVB, or CryIVA, CryIVB, and CryIVD. When concentrations of CytA with low levels of toxicity were combined with CryIVD, a high level of resistance to CryIVD was reduced substantially. Because CytA shares no homology with CryIV proteins, has a different mode of action, and was not used in the resistance selections, its equivalent toxicity to the nonselected and CryIV-resistant mosquitoes was not unexpected. When used alone, CytA exerts its inherent toxicity, binding to the lipid portion of the membrane in sensitive as well as resistant mosquitoes. The expectation, supported by our results, is that the toxicity of CytA would be similar against nonselected and CryIV-resistant mosquito strains.

Our finding that combinations of CytA and CryIV proteins suppressed or substantially reduced CryIV resistance was less expected and implies that these different endotoxin types interact to cause lysis of midgut cells. Studies of CryI proteins in lepidopterous insects have shown that resistance is due to either a reduction in the concentration of microvillar membrane receptors, reduced toxin affinity for the receptors, or an implied failure of the toxin to insert into the microvillar membrane after binding (21–23). If CryIV and CryI toxins have a similar mechanism of action, then possible explanations for our results are that CytA restores the ability of CryIV proteins to bind to and/or insert into the mosquito microvillar membrane. CytA is highly hydrophobic with an affinity for CryIV toxins (33) as well as for unsaturated fatty acids in the lipid portion of the microvillar membrane (31, 43), with detergent-like properties (44) that could facilitate permeation of the cell membrane by CryIV molecules. Thus, CytA’s properties suggest that it assists CryIV binding and insertion, providing a possible mechanism for both CytA’s capacity to reduce CryIV resistance and for the synergism reported between CytA and CryIV proteins against nonresistant mosquitoes (32–35).

Though our data show that combinations of CytA and CryIV proteins suppress CryIV-resistance in C. quinquefasciatus, caution must be exercised in attempting to quantify these effects precisely because the exact ratios of CytA and CryIV toxins in our mixtures were not known. For example, the ratio of CytA to CryIV in the CytA plus CryIVD combination is higher than in the CytA plus CryIVA+CryIVB+CryIVD combination. Variations also occurred in CytA to CryIV toxin ratios between CryIVA+CryIVB and CryIVA+CryIVB+CryIVD combinations. Furthermore, spores were present in all preparations. Although no evidence exists that spores contribute to the toxicity of B. thuringiensis subsp. israelensis to mosquitoes, it is known that against some species, such as Spodoptera exigua (45) and P. xylostella (46), the spore can synergize Cry toxicity. Despite these obstacles to precise characterization of CytA/CryIV interaction, the data from the experiments where the CytA powder was combined with the powders of CryIVA and CryIVB, or CryIVA, CryIVB, and CryIVD, show clearly CytA was the critical component enabling these proteins to suppress or reduce substantially CryIV resistance (Fig. 1). In these mixtures, all B. t. subsp. israelensis strains were derived from the same isolate. Spores and cells therefore would be similar, with CytA being the only unique endotoxin added to the mixtures.

Combining CytA with CryIV proteins restored the toxicity of the CryIV proteins against the resistant mosquito strains to levels that were similar to those obtained with latter proteins against the nonselected strain. However, the toxicity of the CytA/CryIV combinations was not nearly as high against the resistant mosquito strains as it was against the nonselected strains (Fig. 1 A–C). Thus, the CryIV resistance in the resistant mosquitoes, though suppressed, is still present.

Studies of insect resistance to B. thuringiensis have shown that resistance to one Cry protein often confers resistance to several others (13–17, 20, 36). However, it also was shown that this resistance could be circumvented by substituting Cry proteins with limited cross-resistance (15, 22). Although promising, more recent studies have shown that under intensive selection pressure, high levels of resistance can lead to significant cross-resistance to closely and distantly related Cry proteins (23, 24). In this context, our study suggests it may be more effective to circumvent resistance by using a protein with a different mode of action than the selecting protein type, particularly if the second protein interacts synergistically with the protein responsible for resistance.

Because CytA is known to be active only against nematocerous dipterans, e.g., larvae of mosquitoes and blackflies, it might appear that our results are relevant only to this specific use of CryIV and Cyt proteins. However, aside from viewing the CytA/CryIV system as a model, we recently have found that CytA is toxic to at least one coleopteran insect, the cottonwood leaf beetle, Chrysomela scripta (B.A.F. and L.S. Bauer, unpublished work). If CytA proves to have a similar mechanism of action against these insects, then the results of our study could be relevant to the use of CytA to manage resistance to CryIII and possibly other Cry proteins against coleopteran pests. Furthermore, Cyt proteins that differ from CytA now have been identified (47) and also may have potential for use in a range of B. thuringiensis resistance management programs.

Lastly, our focus in this study was CytA’s potential to suppress CryIV resistance. Yet CytA and other Cyt proteins ultimately may play a more important role in resistance management. Evidence from studies of toxin mixtures on the rate of resistance development suggest that CytA plays a critical role in delaying the development of resistance to CryIV proteins in C. quinquefasciatus (28). We currently are evaluating this hypothesis further by selecting separate populations of mosquitoes with CytA and CryIV alone and in combination. If CytA can delay resistance to CryIVD, or each toxin to one another, this could provide a model for developing new strategies for managing resistance to Cry proteins in bacterial insecticides and transgenic plants.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported in part by grants to all authors from the University of California Mosquito Control Research Program, a grant to G.P.G. from the World Health Organization (WHO Grant 900577), and grants to B.A.F. from the United States Department of Agriculture (Competitive Grant 92-37302-7603) and the University of California Biotechnology Research and Education Program (Grant 96-21).

ABBREVIATIONS

- SF

synergism factor

- RR

resistance ratio

References

- 1.Georghiou, G. P. (1994) Phytoprotection 75, Suppl., 51–59.

- 2.Höfte H, Whiteley H R. Microbiol Rev. 1989;53:242–255. doi: 10.1128/mr.53.2.242-255.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Knowles B, Dow J T J. BioEssays. 1993;15:469–476. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Van Frankenhuuyzen K. In: Bacillus thuringiensis: An Environmental Biopesticide: Theory and Practice. Entwistle P F, Cory J S, Bailey M J, Higgs S, editors. New York: Wiley; 1993. pp. 1–35. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Navon A. In: Bacillus thuringiensis: An Environmental Biopesticide: Theory and Practice. Entwistle P F, Cory J S, Bailey M J, Higgs S, editors. New York: Wiley; 1993. pp. 125–146. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Keller B, Langenbruch G-A. In: Bacillus thuringiensis: An Environmental Biopesticide: Theory and Practice. Entwistle P F, Cory J S, Bailey M J, Higgs S, editors. New York: Wiley; 1993. pp. 171–191. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mulla M S. In: Bacterial Control of Mosquitoes and Black Flies. de Barjac H, Sutherland D J, editors. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers Univ. Press; 1990. pp. 134–160. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Perlak F J, Deaton R W, Armstrong T A, Fuchs R L, Sims S R, Greenplate J T, Fischhoff D A. Bio/Technology. 1990;8:939–943. doi: 10.1038/nbt1090-939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Koziel M G, Beland G L, Bowman C, Carozzi N B, Crenshaw R, et al. Bio/Technology. 1993;11:194–200. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fischhoff D A, Bowdish K S, Perlak F J, Marrone P G, McCormick S, Rochester D E, Rogers S G, Fraley R T. Bio/Technology. 1987;5:807–813. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Perlak F J, Stone T B, Muskopf Y M, Petersen L J, Parker G B, McPherson S A, Wyman J, Love S, Reed G, Biever D, Fischhoff D A. Plant Mol Biol. 1993;22:313–321. doi: 10.1007/BF00014938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McGaughey W M. Science. 1985;229:193–195. doi: 10.1126/science.229.4709.193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McGaughey W M, Johnson D E. J Econ Entomol. 1994;87:535–540. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tabashnik B E, Cushing N L, Finson N, Johnson M W. J Econ Entomol. 1990;83:1671–1676. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tabashnik B E, Finson N, Johnson M W, Moar W J. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1993;59:1332–1335. doi: 10.1128/aem.59.5.1332-1335.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tabashnik B E, Finson N, Johnson M W, Heckel D G. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1994;60:4627–4629. doi: 10.1128/aem.60.12.4627-4629.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tabashnik B E, Malvar T, Liu Y-B, Finson N, Borthakur D, Shin B-S, Park S-H, Masson L, De Maagd R A, Bosch D. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1996;62:2839–2844. doi: 10.1128/aem.62.8.2839-2844.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hama H, Suzuki K, Tanaka H. Appl Entomol Zool. 1992;27:355–362. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shelton A M, Robertson J L, Tang J D, Perez C, Eignebrode S D. J Econ Entomol. 1993;86:697–705. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tang J D, Shelton A M, Van Rie J, De Roeck S, Moar W J, Roush R T, Peferoen M. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1996;62:564–569. doi: 10.1128/aem.62.2.564-569.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Van Rie J, McGaughey W H, Johnson D E, Barnett D, Van Mellaert H. Science. 1990;247:72–74. doi: 10.1126/science.2294593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ferre J, Real M D, van Rie J, Jansen S, Peferoen M. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88:5119–5123. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.12.5119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gould F, Martinez-Ramirez A, Anderson A, Ferre J, Silva F J, Moar W J. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:7986–7988. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.17.7986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gould F, Anderson A, Reynolds A, Bumgarner L, Moar W. J Econ Entomol. 1995;88:1545–1559. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Georghiou G P, Wirth M C, Ferrari J, Tran H. Annual Report of University of California Mosquito Control Research. Oakland, CA: California Mosquito Control Association; 1991. pp. 25–27. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Becker N, Ludwig M. J Am Mosq Control Assoc. 1993;9:221–224. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Goldman I F, Arnold J, Carlton B C. J Invertebr Pathol. 1986;47:317–324. doi: 10.1016/0022-2011(86)90102-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Georghiou G P, Wirth M C. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1997;63:1095–1101. doi: 10.1128/aem.63.3.1095-1101.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Porter A G, Davidson E W, Liu J-W. Microbiol Rev. 1993;57:838–861. doi: 10.1128/mr.57.4.838-861.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sangahala S, Walters F S, English L H, Adang M J. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:12334–12340. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Thomas W E, Ellar D J. FEBS Lett. 1983;154:362–368. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(83)80183-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wu D, Chang F N. FEBS Lett. 1985;190:232–236. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ibarra J E, Federici B A. J Bacteriol. 1986;165:527–533. doi: 10.1128/jb.165.2.527-533.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wu D, Johnson J J, Federici B A. Mol Microbiol. 1994;13:965–972. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1994.tb00488.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Crickmore N, Bone E J, Williams J A, Ellar D J. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1995;131:249–254. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wirth, M. C. & Georghiou, G. P. (1997) J. Econ. Entomol, in press. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 37.Chang C, Dai S-M, Frutos R, Federici B A, Gill S S. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1993;58:507–512. doi: 10.1128/aem.58.2.507-512.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Delécluse A, Charles J-F, Klier A, Rapoport G. J Bacteriol. 1991;173:3374–3381. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.11.3374-3381.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Delécluse A, Poncet S, Klier A, Rapoport G. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1993;59:3922–3927. doi: 10.1128/aem.59.11.3922-3927.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wu D, Federici B A. J Bacteriol. 1993;175:5276–5280. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.16.5276-5280.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Raymond M. Cah ORSTROM Ser Entomol Med Parasitol. 1985;23:117–121. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tabashnik B E. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1992;58:3343–3346. doi: 10.1128/aem.58.10.3343-3346.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ward E S, Ellar D J, Chilcott C N. J Mol Biol. 1988;202:527–535. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(88)90283-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Butko P, Huang F, Pusztai-Carey M, Surewicz W K. Biochemistry. 1996;35:11355–11360. doi: 10.1021/bi960970s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Moar W, Trumble J T, Federici B A. J Econ Entomol. 1989;82:1593–1603. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Miyasono M, Inagaki S, Yamamoto M, Ohba K, Ishiguro T, Takeda R, Hayashi Y. J Invertebr Pathol. 1994;63:111–112. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Koni P, Ellar D J. Microbiology. 1994;140:1869–1880. doi: 10.1099/13500872-140-8-1869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]