Abstract

A catalyst has been synthesized comprising a manganese porphyrin carrying four beta-cyclodextrin groups. It catalyzes the hydroxylation of substrates of appropriate size carrying tert-butylphenyl groups that can hydrophobically bind into the cyclodextrin cavities. In one example as many as 650 catalytic turnovers are seen before the catalyst is oxidatively destroyed, and with a rate comparable to that of typical cytochrome P450 enzymes. In another example, a steroid derivative is regio- and stereoselectively hydroxylated at a single unactivated carbon atom, but more slowly and with fewer turnovers. The carbon attacked is not the most chemically reactive, and the selectivity is determined by the geometry of the catalyst-substrate complex. Nonbinding substrates are not reactive under the conditions used, and substrates with more flexible binding geometries give more than a single product.

Enzymes are remarkably selective catalysts. They bind a particular substrate out of a sea of available compounds in solution, then they perform a reaction at a particular position of the bound substrate (thus showing regioselectivity), often with stereoselectivity as well. The geometric control in the enzyme–substrate complex can completely dominate the normal reactivity of the substrate. For example, enzymes in the class cytochrome P450 can hydroxylate unactivated carbons in steroids while leaving much more reactive substrate positions, such as those in or next to double bonds, untouched (1–3). In these enzymes an oxygen atom becomes attached to the iron atom in the metalloporphyrin, and is then transferred to the substrate within the enzyme–substrate complex.

Although it is of interest to learn how to mimic the great rate accelerations achieved in enzymatic catalysis, imitating the selectivity is even more important. For this reason, we have carried out studies over many years to learn how to use the geometric control typical of enzyme reactions in selectively functionalizing steroids and other substrates. In the earliest work, a benzophenone attached to a steroid was shown to perform selective photochemical functionalization of the substrate (4–11). In later work, a template attached to the substrate was able to direct free radical reactions to specific carbons because of the geometry of the template-substrate species; see refs. 12–14 for reviews. However, there were limitations to these methods.

For one, the reagent or template was covalently attached to the substrate, so catalytic turnover was not possible. As a corollary of this, relatively simple reagents or templates were used—attached by a single flexible link—so the geometric control was not perfect.

Groves and Neumann (15–17) have shown that organization in a bilayer can be used to achieve hydroxylation of a steroid by a metalloporphyrin catalyst, but catalytic turnover was blocked by strong binding of the product. Grieco and colleagues (18–20) have also shown that a metalloporphyrin can hydroxylate a steroid in an intramolecular reaction if it is covalently attached, but again, this is not a catalytic process with turnover. We have now made a catalyst that indeed binds a substrate, performs a hydroxylation catalyzed by a metalloporphyrin, and then releases the product to perform true turnover catalysis. In our best example, the hydroxylation is highly selective for an otherwise unreactive and unremarkable steroid position. The geometry within the complex of substrate with artificial enzyme determines the product formed.

To achieve turnover catalysis—and thus to justify the use of a more complex catalyst, with more than one binding interaction to a substrate so as to improve selectivity—we have examined metalloporphyrin derivatives (as in the cytochrome P450 enzymes) and metallosalens carrying substrate binding groups. In our first study (21), metal binding groups were attached to the porphyrin or salen system, so that substrates carrying metal binding groups at both ends could coordinate to the catalysts through bridging metal ions. When two such coordinations occurred, to stretch the substrate across the central metal ion of the metalloporphyrin or metallosalen, a substrate double bond was catalytically epoxidized with turnover.

To extend this to substrates that do not coordinate to metal ions, we have recently synthesized metallosalens carrying two beta-cyclodextrin groups, and metalloporphyrins carrying two and four beta-cyclodextrin groups (22, 23). We found that in water the porphyrins were able to bind olefins having hydrophobic end groups, and catalyze selective double bond epoxidation (22). The salens bound the substrates but did not catalyze the epoxidations, apparently because the geometry of the catalysts changes greatly when they go to the metallo-oxo intermediate structures.

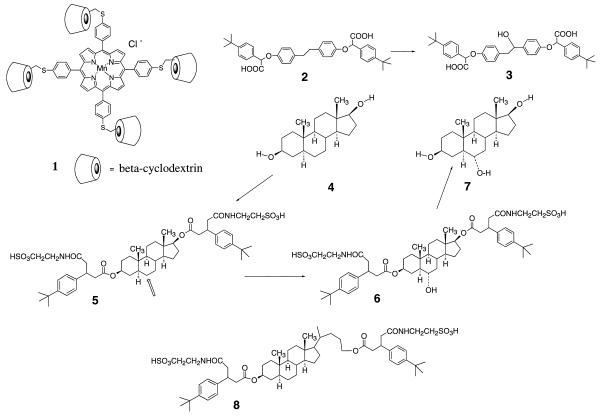

In subsequent work (23), we saw that the porphyrin catalyst 1 that carries four beta-cyclodextrin units and a bound Mn(III) was able to catalyze the hydroxylation of bound substrates in water. The diphenylethane derivative 2 was hydroxylated completely to form product 3 with 7 mol% of catalyst 1 using iodosobenzene as the oxidant, so there were at least 15 turnovers. The iodosobenzene transfers an oxygen atom to the Mn(III), and the resulting metallo-oxo species hydroxylates a nearby carbon of the bound substrate.

Control reactions excluded alternative mechanisms, such as free radical chain processes. The hydroxylation was dependent on the presence of the two hydrophobic tert-butylphenyl groups at each end of 2, that bound into two beta-cyclodextrin units trans to each other in catalyst 1. The binding constant for substrate 2 into the porphyrin precursor of 1, lacking the bound Mn(III), was (1.3 ± 0.2) × 105 M−1, determined by titration calorimetry. Two molecules of 2 were bound, presumably one on each face of the porphyrin. In the hydroxylation reactions, pyridine was added to coordinate to one face of the metalloporphyrin so as to direct the substrate and the oxygen atom to the other face.

Androstane-3,17-diol 4 was converted to the diester 5, with tert-butylphenyl hydrophobic binding groups and solubilizing sulfonate groups. Molecular models indicated that the two tert-butylphenyl groups can bind into cyclodextrins on the opposite side of 1 so as to put ring B of the steroid directly over the metalloporphyrin unit. With 10 mol% of catalyst 1, and an excess of iodosobenzene, substrate 5 was converted to the 6-hydroxy derivative 6. After ester hydrolysis the only products were 7 (40%) and recovered starting material 4 (60%), so four turnovers had been achieved. No other product could be detected. The structure of triol 7 was established by NMR spectroscopy and comparison with an authentic sample. Thus the regiochemistry and stereochemistry of this reaction appears to be complete, within experimental limits.

By contrast, a derivative of cholestanol with only one attached hydrophobic binding group, whose binding geometry is therefore less well defined, gave several hydroxylated products with the same catalyst 1 (23). An analog of 5 lacking the tert-butylphenyl groups was not hydroxylated under our reaction conditions. We have now explored these reactions further.

METHODS AND MATERIALS

The preparation of catalyst 1 has been described elsewhere (22). Substrate 2 was prepared by alkylation of 1,2-bis(4-hydroxyphenyl)ethane with 4-tert-butylphenylbromoacetate methyl ester, then hydrolysis to the diacid with lithium hydroxide. Substrate 5 was prepared from commercial androstanediol 4 by acylation with 3-(4-tert-butylphenyl)glutaric anhydride, then conversion of the free carboxyl groups to N-hydroxysuccinimide esters with 1-ethyl-3–3(3-dimethylaminopropyl)carbodiimide, and reaction of these esters with taurine. Substrate 8 was prepared from commercial 5α-cholan-3β-24 diol by a procedure analogous to that for 4. New compounds were characterized by H-NMR and mass spectra.

A Typical Hydroxylation Reaction.

To a clear solution of substrate 5 (60 mg, 0.06 mmol), catalyst 1 (35 mg, 0.006 mmol) and pyridine (50 μl, 0.62 mmol) in 60 ml distilled water was added iodosylbenzene (66 mg, 0.30 mmol) in 5 ml methanol. After 2 hr stirring at room temperature, the reaction mixture was stirred overnight with 14 ml 25% aqueous KOH. It was then acidified to pH 6 with 2.0 M HCl, and extracted with EtOAc. The organic layer was washed with brine and dried over Na2SO4, and the products were isolated by preparative thin layer chromatography. They were identified as 8 mg of 5α-3β,17β-androstanediol 4 and 6 mg of 5α-3β,6α,17β-androstanetriol (7). The latter was identified by NMR spectroscopy and comparison with an authentic sample, as described (23).

For quantitative assay, the crude product mixture before chromatography was benzoylated, and the benzoates assayed by HPLC, calibrated by authentic standards. Only the benzoates of the starting androstanediol 4 and of 7 were detected.

Compound 2 was hydroxylated in a similar fashion, and the reaction product 3 and unconverted 2 were directly assayed by H-NMR spectroscopy.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

We confirm the previous report (23) that the diphenylethane substrate 2 is catalytically hydroxylated by 1 with iodosobenzene. No product was formed with H2O2 or NaClO2 as oxidants; magnesium monoperoxyphthalate gave product, but in only ≈20% of the yield seen with iodosobenzene. We find that there can be many more turnovers with iodosobenzene than previously reported (23), and with a good rate.

Previously we knew only that the hydroxylation of 2 to 3 was complete with 7 mol% of catalyst, so it occurred with at least 15 turnovers. Now we find that 0.1 mol% of catalyst achieves a 50% conversion (500 turnovers), while 0.02 mol% catalyst achieves a 13% conversion (650 turnovers). Furthermore, 260 turnovers are achieved in 10 minutes, so the rate is similar to or better than the rates reported for some typical P450 enzymes (24).

No other products can be detected in the oxidation of 5 except 6 and recovered 5 (analyzed as 7 and 4), even with our new analytical procedure in which the esters are hydrolyzed, the reaction mixture is benzoylated, and the mixture is analyzed by HPLC. The hydroxylation of 5 to 6 occurs with three to five turnovers with a catalyst concentration from 0.4 to 10 mol%. Thus this hydroxylation competes more poorly with the rate of oxidative destruction of the catalyst than does the hydroxylation of 2.

An analog of catalyst 1 in which Fe(III) is substituted for Mn(III) also catalyzes the conversion of 5 to 6, but in only 5–10% under conditions in which 1 catalyzes a 40% conversion. Groves and Neuman (17) have reported that Mn(III) porphyrins are more effective oxidation catalysts than are the Fe(III) analogs.

We have also examined a steroid carrying the two binding groups of 4 in a different geometry. Compound 8 was submitted to our normal catalytic conditions, and formed at least five hydroxylated products, none major. Thus the selectivity we saw with 5 is lost with a substrate that is significantly longer.

CONCLUSIONS

An enzyme mimic using a metalloporphyrin to catalyze oxidations by iodosobenzene—and four cyclodextrin rings for substrate binding and solubilization—is able to perform substrate hydroxylations. With a simple dihydrostilbene substrate the hydroxylations occur at the speed of corresponding cytochrome P450 enzymes, and with hundreds of turnovers. With a steroid substrate the reactions are slower, with fewer turnovers, but the reaction is completely selective for hydroxylation of a single steroid position with regio- and stereoselectivity.

The position hydroxylated is not the most reactive, but is the one selected by the geometry of the catalyst-substrate complex. With other substrates that fit the catalyst less well, more than one hydroxylation product is formed; no hydroxylation occurs under the conditions used with substrates that do not bind to the catalyst. Thus this catalyst has many of the properties of an enzyme, and opens the way to the development of other such catalysts whose selectivity is directed by geometry, not substrate reactivity. For example, we are currently studying a catalyst related to 1 with perfluorinated phenyl rings, which is much more stable to oxidative degradation. The present artificial enzyme, and related compounds, promise to be useful tools for selective biomimetic syntheses.

Scheme I.

Acknowledgments

This work has been supported by the National Institutes of Health, the National Science Foundation, and the Kanagawa Academy of Science and Technology.

ABBREVIATIONS

- betaCD

beta-cyclodextrin

- hplc

high pressure liquid chromatography

- EDAC

1-ethyl-3-(3-dimethylaminopropyl)carbodiimide

References

- 1.Woggon W D. In: Cytochrome P 450: Significance, Reaction Mechanisms and Active Site Analogues. Smidtchen F P, editor; Smidtchen F P, editor. Berlin: Springer; 1996. pp. 39–96. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Groves J T, Han Y-Z. In: Models and Mechanism of Cytochrome P-450 Action. Ortiz de Montellano P R, editor; Ortiz de Montellano P R, editor. New York: Plenum; 1995. pp. 3–48. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Meunier B. Chem Rev. 1992;92:1411–1456. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Breslow R, Winnik M A. J Am Chem Soc. 1969;91:3083–3084. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Breslow R, Baldwin S W. J Am Chem Soc. 1970;92:732–734. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Breslow R, Scholl P C. J Am Chem Soc. 1971;93:2331–2333. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Breslow R, Kalicky P. J Am Chem Soc. 1971;93:3540–3541. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Breslow R, Baldwin S, Flechtner T, Kalicky P, Liu S, Washburn W. J Am Chem Soc. 1973;95:3251–3262. doi: 10.1021/ja00791a031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Breslow R, Rothbard J, Herman F, Rodriguez M L. J Am Chem Soc. 1978;100:1213–1218. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Czarniecki M F, Breslow R. J Am Chem Soc. 1979;101:3675–3676. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Breslow R, Rajagopalan R, Schwarz J. J Am Chem Soc. 1981;103:2905–2907. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Breslow R. In: Oxidation by Remote Functionalization Methods. Trost B M, editor; Trost B M, editor. Vol. 7. Oxford: Pergamon; 1991. pp. 39–52. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Breslow R. Chemtracts Org Chem. 1988;1:333–348. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Breslow R. Acc Chem Res. 1980;13:170–177. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Groves J T, Neumann R. J Am Chem Soc. 1989;111:2900–2909. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Groves J T, Neumann R. J Am Chem Soc. 1987;109:5045–5047. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Groves J T, Neumann R. J Org Chem. 1988;53:3891–3893. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Grieco P A, Stuk T L. J Am Chem Soc. 1990;112:7799–7801. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kaufman M D, Grieco P A, Bougie D W. J Am Chem Soc. 1993;115:11648–11649. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Stuk T L, Grieco P A, Marsh M M. J Org Chem. 1991;56:2957–2959. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Breslow R, Brown A B, McCullough R D, White P W. J Am Chem Soc. 1989;111:4517–4518. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Breslow R, Zhang X, Xu R, Maletic M, Merger R. J Am Chem Soc. 1996;118:11678–11679. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Breslow R, Zhang X, Huang Y. J Am Chem Soc. 1997;119:4535–4536. [Google Scholar]

- 24.McCarthy M-B, White R E. J Biol Chem. 1983;258:9153–9158. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]