Abstract

The firing behaviour of vestibular nucleus neurons putatively involved in producing the vestibulo-ocular reflex (VOR) was studied during active and passive head movements in squirrel monkeys. Single unit recordings were obtained from 14 position-vestibular (PV) neurons, 30 position-vestibular-pause (PVP) neurons and 9 eye-head-vestibular (EHV) neurons. Neurons were sub-classified as type I or II based on whether they were excited or inhibited during ipsilateral head rotation. Different classes of cell exhibited distinctive responses during active head movements produced during and after gaze saccades. Type I PV cells were nearly as sensitive to active head movements as they were to passive head movements during saccades. Type II PV neurons were insensitive to active head movements both during and after gaze saccades. PVP and EHV neurons were insensitive to active head movements during saccadic gaze shifts, and exhibited asymmetric sensitivity to active head movements following the gaze shift. PVP neurons were less sensitive to ondirection head movements during the VOR after gaze saccades, while EHV neurons exhibited an enhanced sensitivity to head movements in their on direction. Vestibular signals related to the passive head movement were faithfully encoded by vestibular nucleus neurons. We conclude that central VOR pathway neurons are differentially sensitive to active and passive head movements both during and after gaze saccades due primarily to an input related to head movement motor commands. The convergence of motor and sensory reafferent inputs on VOR pathways provides a mechanism for separate control of eye and head movements during and after saccadic gaze shifts.

The vestibulo-ocular reflex (VOR) functions to stabilize visual images on the retina by producing eye movements that minimize or cancel gaze velocity when the head is passively perturbed. The reflex is largely mediated by central pathways arising from neurons located in the vestibular nuclei that receive inputs from vestibular nerve afferents and project directly to extraocular motoneurons (Highstein & McCrea, 1988). This tri-synaptic pathway allows the VOR to produce compensatory eye movements that stabilize gaze in response to high frequency head movements with minimal delay. In spite of its relatively simple organization and powerful effect on eye movements, there are circumstances when the vestibular sensory inputs to this reflex are either inadequate to maintain image stability or need to be cancelled or suppressed. One situation when both circumstances may occur is during rapid head movements that are produced to change the direction of gaze.

Most active gaze shifts involve a rapid, coordinated saccadic movement of the head and the eyes that brings an image of interest onto the retina. During small gaze shifts to targets that are within the oculomotor range the coordination of eye and head movements could be accomplished by sending a common gaze command to both the eye and head movement motor systems and allowing the VOR to coordinate the two types of movement (Bizzi et al. 1972; Laurutis & Robinson, 1986; Guitton et al. 1990; Tomlinson 1990; Roy & Cullen, 2002). The appropriate eye velocity command is constructed by summing gaze velocity commands with vestibular signals related to active head movement. The elegance of this idea is that the VOR would not be cancelled, but would instead be an essential part of the neural process of coordinating eye and head movements. The idea is supported by observations that many reticular neurons located in regions of the brain that contain premotor saccade-related burst neurons generate signals related to gaze velocity rather than eye velocity (Whittington et al. 1984; Cullen et al. 1993b; Cullen & Guitton, 1996, 1997).

The computation of eye velocity commands by subtraction of vestibular signals from gaze commands may not be sufficient for coordinating eye and head movements during many gaze saccades; particularly those in which the amplitude, peak acceleration, or peak velocity of the compensatory eye movement that is required of the VOR is large (Sparks, 1999; Freedman & Sparks, 2000; Sparks et al. 2001). Many vestibular afferents are driven into inhibitory saturation during large rapid saccadic head movements in the off-direction, thus depriving VOR pathways of a significant fraction of their input related to head movement (Cullen & Minor, 2002). Vestibular nerve afferents may not even provide a linear estimate of active head movements in their preferred direction, since many cells exhibit non-linear responses to high frequency stimuli (Lasker et al. 1999; Minor et al. 1999) or to high velocity stimuli (Plotnik & Goldberg, 2000). The problem is exacerbated when the visual object of interest (e.g. a hand-held object) is close to the head. In this circumstance the amplitude and speed of the compensatory eye movements produced by the VOR often have to be much larger than the amplitude and speed of the head movement (Viirre et al. 1986; Chen-Huang & McCrea, 1998, 1999).

Several mechanisms could assist the VOR in coordinating eye and head movements during active gaze shifts. An internal estimate of the expected active head or gaze velocity could be added to central VOR pathways to reduce their sensitivity to vestibular nerve inputs so that the VOR can be cancelled to prevent it from contributing to the gaze shift (Barr et al. 1976; Freedman & Sparks, 2000). Asymmetric processing of vestibular signals could be dealt with by adding other sensory estimates of head motion to vestibular sensory signals. Finally the brain could parametrically modify vestibular reafferent signals as a function of behavioural context (Barr et al. 1976; McCrea et al. 1996, 1999; Roy & Cullen 2001; Cullen et al. 2001).

In this study, we examined the firing behaviour of several classes of vestibular neurons that are involved in generating the vestibulo-ocular reflex during active gaze saccades in squirrel monkeys. This primate species has a relatively small oculomotor range, and utilizes a combination of eye and head movements to reorient gaze. We report that signals related to active head movements are largely cancelled on secondary VOR pathways during active gaze shifts and significantly modified during the postsaccadic period immediately following gaze shifts when eye movements were generated that stabilized gaze.

Methods

Experimental apparatus and protocols

Most experimental methods have been previously described (Chen-Huang & McCrea, 1998; Gdowski & McCrea, 1999, 2000; Belton & McCrea, 2000). Protocols were approved by the University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee and adhered to the National Institutes of Health principles of laboratory animal care (NIH publication No. 86-23). Surgical procedures were carried out under sterile conditions. Four adult squirrel monkeys were surgically prepared in two or three stages for chronic recordings of head and eye movements, single-unit activity, and for electrical stimulation of both labyrinths. Each surgical procedure was carried out in a central surgical suite with the assistance of local veterinarians and animal care technicians. The animals were initially anaesthetized with ketamine (10 mg (kg body weight)−1, i.p.), intubated with an endotracheal cannula, and an i.v. cannula was inserted into the saphenous vein. The endotracheal cannula was then used to deliver isoflurane anaesthesia. Analgesics (acetaminophen, 15 mg kg−1 twice per day for 4 days; Bupenorphine, 0.03 mg kg−1) and an antibiotic (sulfa-trimethoprim, 30 mg kg−1) were administered post-operatively. The animals recovered from these minor surgical procedures within a few days.

The monkeys were trained to pursue or fixate visual targets projected onto a tangent screen. The training was carried out for several months prior to experiments. The animal's voluntary cooperation was required in order for us to carry out a successful experiment. Therefore we made every effort to maintain the health and psychological well-being of our animals, both during and between experimental sessions. We assessed the condition of each monkey on a daily basis, and continuously monitored the animal's behavioural responses during experimental recording sessions.

During training sessions and experiments the animals were seated on a vestibular turntable in a Plexiglas chair with a shoulder harness. Head movements were permitted only in the plane of the horizontal semicircular canal about the C1-C2 axis. Movements in other directions were restricted by linking a rod that rotated in the yaw plane within a ball bearing assembly attached to the table to the surgically fitted attachment on the skull. Small postural adjustments were permitted with a universal joint located above the animal's head in line with the rod. The monkeys were introduced to this setup slowly over a period of several days to allow them to become accustomed to the chair and restraint. During experiments and training sessions the animals were continuously observed with a video system to ensure that they were comfortable. Horizontal and vertical gaze position and horizontal head position were measured with respect to the turntable (i.e. trunk) using the magnetic search coil technique. Torsional eye movements were not measured. During experiments single neurons were recorded with epoxy-insulated Tungsten microelectrodes.

Each signal, including gaze and head position and turntable velocity, was low-pass filtered (5-10 kHz) and recorded with a personal computer system (sampling rate: 200 or 500 Hz). Single unit spikes were recorded with conventional techniques and were discriminated with a dual window discriminator (Bak). Unitary events were stored as clock events on a data acquisition system (CED 1401) with a 0.1 ms time resolution. Eye position was computed as the difference between gaze and head position. Velocity signals were computed by digitally differentiating and filtering (low pass smoothing, 20-50 Hz) the position waveforms.

Single unit recordings

The vestibular nucleus neurons included in this study were position-vestibular-pause (PVP) neurons, eye-head-velocity (EHV) neurons and position-vestibular (PV) neurons. Each cell class receives direct vestibular nerve inputs, and each has been demonstrated to project either to the abducens nucleus or to the medial rectus subdivision of the oculomotor nucleus (McCrea et al. 1987; Chen-Huang & McCrea, 1998; Scudder & Fuchs, 1992). Microelectrode location within the vestibular nuclei was verified by characteristics of the monosynaptically evoked field potentials following electrical stimulation of the ipsilateral vestibular nerve. All cells were sensitive to passive whole body rotation (WBR) in the plane of the horizontal semicircular canal and were sensitive to horizontal eye movements. Most were activated at monosynaptic latencies following single shock stimulation electrical stimulation of the vestibular nerve (0.1 ms monophasic perilymphatic cathodal pulses, 50-300 μA).

PVP neurons were recognized by their characteristic firing behaviour during spontaneous eye movements, smooth pursuit of visual targets and passive whole body rotation. They were sensitive to ipsilateral head velocity, contralateral eye position, contralateral eye velocity during ocular pursuit, and were inhibited or silenced during saccades (Cullen et al. 1993a; Chen-Huang & McCrea, 1999). PV neurons were sensitive to horizontal eye position but not to eye velocity. They did not pause during ocular saccades. EHV neurons also usually did not pause during ocular saccades, and they were sensitive to eye and head movements in the same direction; e.g. the firing behaviour of type I EHV cells was related to ipsilateral eye velocity during ocular pursuit and to ipsilateral head velocity during VOR cancellation.

Neuronal responses during gaze saccades were studied primarily when the animal was in the dark or in dim light facing a tangent screen. These responses were compared with responses observed during gaze saccades produced during eye-head tracking of a moving laser projected target. In some cases, neuronal responses during active head-on-trunk movements were compared with passive head-on-trunk rotation. Forced head-on-trunk rotation was produced with a ceiling-mounted stepping motor that was attached to the head with a rod. Neck afferent inputs were assessed by passive rotation of the trunk (passive neck rotation, PNR) while the animal's head was held stationary in space (Gdowski & McCrea, 2000; Gdowski et al. 2001).

Data analysis

Neuronal sensitivity to eye position and ocular saccades

Neuronal sensitivity to eye position (ks) was assessed using multiple regression analysis of firing rate, horizontal eye position, vertical eye position and head position during periods of steady gaze in the absence of a visual target. The instantaneous firing rate of the neuron was binned at the data acquisition-sampling interval (200-500 samples s−1). Most of the cells were sensitive to ocular saccades in the absence of a target. These responses were analysed by selecting groups of 8-10 spontaneous saccades with similar direction and amplitude. Responses during these selected saccades were averaged with respect to the onset, peak velocity and termination of the saccade. Unit response latency to saccadic eye movements (δ) was estimated from records that were aligned with respect to saccade onset. Neuronal sensitivity to saccadic eye velocity and acceleration was estimated from records that were aligned with respect to saccade peak eye velocity. An estimate of the unit sensitivities (rv, ra) to eye velocity (E′) and eye acceleration (E″) during saccades was obtained by fitting a linear function to average firing rate (FR)where:

| (1) |

Analysis of unit responses to periodic stimuli

Neural responses and eye movements during smooth pursuit, WBR, PNR and forced head-on-trunk rotation were usually studied with periodic, sinusoidal stimuli. The analysis was carried out by first screening records, stimulus cycle-by-cycle, to eliminate periods when the animal was not alert (long intervals between ocular saccades), or in cases during trained protocols when the angular position of the eye was off target by more than 2 deg. Responses and movements that occurred during saccades were excluded from the records before averaging. Typically, all data that occurred within 30 ms before the onset of the saccadic gaze shift and 40 ms after the end of the gaze shift were excluded from the analysis. The remaining records were averaged, sample-by-sample, with respect to the beginning of a stimulus period. The gain and phase of neural and behavioural responses were quantified using a linear regression of a sinusoidal function whose period was the same as that of the stimulus.

In order to assess responses during non-periodic gaze saccades the neuronal sensitivity to passive head rotation during sinusoidal WBR (usually 2.3 Hz, 20 deg s−1 peak velocity) was expressed as a combination of sensitivities (gv, ga) to head velocity (H‘) and head acceleration (H‘’) such that:

| (2) |

The rotational responses of most units were also recorded during fixation of earth-stationary and head-stationary targets. The records obtained during rotation while fixating head stationary targets (VOR cancellation) were not considered to be accurate estimates of vestibular sensitivity, since our previous studies showed that the head movement sensitivity of many eye-movement related vestibular neurons were modified during VOR cancellation (Cullen et al. 1993a; Chen-Huang & McCrea, 1999). However, responses during VOR cancellation were used routinely for distinguishing different classes of eye movement-related units.

Analysis of saccade related responses during combined eye and head saccadic gaze shifts

The eye and head movements related to gaze saccades varied considerably. A typical spontaneous saccade generated while the head was free to move is shown in Fig. 1A. For analytic purposes, the events related to gaze saccades were divided into two time periods: (1) when the eyes and head moved in the same direction during the active gaze shift and (2) when the eye and head moved in opposite directions (gaze stabilization, ocular rollback in Fig. 1A) immediately following the active gaze shift. These responses were analysed by selecting 8-10 spontaneous saccades with similar direction and amplitude. Quantitative analysis of neuronal responses during these intervals was done by averaging records aligned on the beginning of the active gaze shift or aligned at the beginning of the ocular rollback at the end of the gaze shift. In most cases, eye and head movements were initiated at nearly the same time, but many gaze shifts were observed in which the head movement preceded the initiation of the gaze shift. This type of gaze saccade was analysed separately by aligning records at the initiation of the head movement.

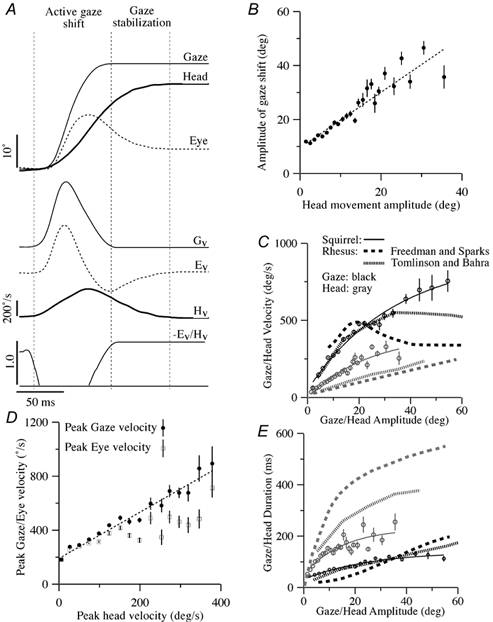

Figure 1. Characteristics of 2500 squirrel monkey saccadic gaze shifts recorded concomitantly with single unit recordings in this study.

A, a typical gaze saccade. Records of gaze, eye and head position are superimposed at the top, while records of gaze, eye and head velocity (Gv, Hv and Ev) and the gain of compensatory eye movement are shown at the bottom. In this study it was convenient to subdivide the description of vestibular neuron responses into those related to the active gaze shift and those related to the period of gaze stabilization immediately after the gaze shift. B, amplitude of saccadic gaze shifts plotted as a function of the amplitude of accompanying saccadic head movement. Each • represents the average of many saccades. The vertical bars indicate the standard error of the mean of each value. The slope intercept of the linear fit to this data was approximately 10 deg (dashed line; G = 9.9 + 1.0HT; correlation coefficient (r2) = 0.93), which corresponds to the usual threshold for head movement contributions to gaze shifts and the common oculomotor range of squirrel monkeys. C, peak gaze velocity (black symbols) plotted as a function of peak gaze amplitude, and mean peak head velocity (grey symbols) plotted as a function of peak head amplitude. Exponential fits between gaze velocity and amplitude (dashed line; G′ = 51 + 862(1 - exp(-0.03G); r2 = 0.99) and head velocity and amplitude (dashed line; H’T = 406(1 - exp(-0.04HT); r2 = 0.95) are superimposed. Comparable observations for Macaque monkeys reported by Tomlinson & Bahra (1986, dashed traces) and Freedman & Sparks (2000, dotted traces) are superimposed for comparison. D, peak gaze (•) and eye velocity (□) of gaze saccades plotted as a function of peak head velocity. Only saccades having changes in head position greater than 1 deg were included. Each dot represents the average of many saccades. A linear fit between gaze and head velocity is superimposed (dashed line; G′ = 198 + 1.7HT); r2 = 0.98). E, the mean duration of the gaze shift (•) plotted as a function of peak gaze amplitude, and the mean duration (○) head velocity plotted as a function of peak head amplitude. Exponential fits between gaze duration (tg) and amplitude (dashed line; tg = 32 + 108(1 - exp(-0.04G); r2 = 0.95) and head duration (th) and amplitude (dashed line; th = 49 + 182(1 - exp(-0.07HT; r2 = 0.88) are shown. Comparable observations for Macaque monkeys reported by Tomlinson & Bahra (1986, dashed traces) and Freedman & Sparks (2000, dotted traces) are superimposed for comparison.

In some units, responses during gaze saccades were compared with their responses during ocular saccades by subtracting an estimate of the eye movement-related component (eqn (1)) of the cell's gaze saccade response.

Methods for assaying vestibular sensitivity during quick phases of head nystagmus

The sensitivity of some cells to passive head movements during gaze saccades was quantified by selectively averaging responses recorded during WBR that were related to quick phases of nystagmus that were accompanied by active head movements. Responses that occurred during quick phases of head nystagmus were averaged with respect to the stimulus frequency and were subjected to a sinusoidal regressive fit to determine the response gain and phase. Only records that occurred 40 ms after the initiation of the quick phase and 40 ms before the end of the quick phase were selected for analysis (see Gdowski & McCrea, 1999).

Results

Squirrel monkeys have a small oculomotor range (± 20-25 deg) and a comparatively small head (approximately 2.5 cm diameter, 100 g). When they are alert they spontaneously produce 2-3 saccades per second, separated by epochs of gaze stability that last 200-1000 ms. A large fraction of these saccades involve coordinated movements of both the eye and the head (approximately 44 % of all saccades; and 64 % of all saccades greater than 10 deg in amplitude). A saccade involving a coordinated eye and head movement is illustrated in Fig. 1A. The gaze saccade can be temporally subdivided into periods defined by the direction of the eye and head movement components. During the active gaze shift, the eyes and head move in the same direction to produce a change in the direction of gaze. Near the end of the active gaze shift, the eyes begin to counter-rotate in the opposite direction of the head movement in order to stabilize gaze while the head is moving. During the period of gaze stabilization at the end of the gaze shift the compensatory eye movements are nearly equal and opposite to the ongoing head movement. The graphs in Fig. 1B-E illustrate the average characteristics of 2 500 spontaneous horizontal saccadic gaze shifts recorded concomitantly with single unit recordings in the three animals included in this study.

Contribution of active head movements to gaze velocity during large saccadic gaze shifts

The relative contribution of head movements to the gaze shift produced during gaze saccades depended primarily on the amplitude of the gaze shift. Small saccades tended to be produced by eye movements alone. For saccades greater than 10 deg, the amplitude of head movements increased linearly with increases in the size and speed of the gaze shift. In Fig. 1B, the amplitude of gaze saccades is plotted as a function of the amplitude of the head movement component of the saccade. Each point represents an average of many saccades. The error bars represent the standard errors of the mean for each of the amplitudes. The slope of the linear regression was 1.03 and the y-axis intercept was 9.9 deg. Thus, on average, eye movements only contributed to the first 10 deg of a saccadic gaze shift and the remainder of the change in gaze direction was produced primarily by a change in head position.

The speed of the head movement contributed to the speed of the gaze shift. Thus gaze velocity and head velocity increased as a function of saccade amplitude. In Fig. 1C, peak gaze velocity is plotted as a function of gaze saccade amplitude (•). These data were fitted with an exponential function:

where G′ is peak gaze velocity and G is the amplitude of a gaze saccade in degrees. A similar relationship existed between peak head velocity (gray symbols) and the amplitude of the head movement component of gaze saccades:

where H′T is peak head-on-trunk velocity and HT is the amplitude of the head movement in degrees.

Squirrel monkey head movements are relatively fast, and contribute a large fraction of the gaze velocity produced during gaze saccades. The peak gaze velocity generated during small saccades was usually less than 200 deg s−1. Peak gaze velocity increased linearly as a function of peak head velocity, although faster head movements were also accompanied with faster eye movements. In Fig. 1D, peak gaze velocity and peak eye velocity are plotted as a function of peak head velocity for the same set of 2 500 gaze saccades. The slope of the linear regression of horizontal gaze velocity and peak head velocity (dotted line) was 1.7, which reflects an increase in the speed of both eye and head movements during large gaze saccades. The increase in peak gaze velocity provided by head movements was accompanied by an increase in saccade duration. For example, the mean peak eye velocity and duration of horizontal ocular saccades that were between 13-15 deg in magnitude was 274 ± 8.5 deg s−1 and 93.5 ± 2.3 ms. Gaze saccades of comparable amplitude whose head movement was greater than 1 deg (mean head velocity: 87 ± 4.9 deg s−1) had a higher average peak gaze velocity (378 ± 13.8 deg s−1) and a slightly longer duration (100.2 ± 5.6 ms).

In sum, behavioural analysis suggests that the gain of the VOR related to active head movements is reduced during gaze saccades. The reduction produces an increase in the peak velocity of the saccade at the cost of a small increase in the duration of the gaze shift. As will be shown below, the VOR gain reduction reflects suppression of head movement signals in most secondary VOR pathways during saccadic gaze shifts.

Head and eye movements during postsaccadic gaze stabilization

Active head movements typically extended beyond the duration of the saccadic gaze shift. During this period, the head movement was almost always accompanied by an equal, but oppositely, directed eye movement. The duration of the stabilization component of gaze saccades (i.e. rollback eye movement) was variable and depended on saccade amplitude. In Fig. 1E, the duration of the gaze shift and the duration of the accompanying head movement are plotted as a function of saccade amplitude. The duration of the phase of the gaze saccade during which gaze was stabilized by compensatory eye movement is the difference between the duration of the head movement and the duration of the gaze shift. The duration of this period of gaze stabilization was often less than 100 ms and rarely exceeded 200 ms.

Comparison of gaze saccades in squirrel and rhesus monkeys

The dynamic characteristics of squirrel monkey gaze saccades were similar to those previously described in rhesus monkeys. The observations in these larger primates made by Tomlinson & Bahra (1986) and Freedman & Sparks (2000) are superimposed on the observations in squirrel monkeys in Figs. 1C and E. The relationship between peak gaze velocity and saccade amplitude and the relationship between saccade duration and amplitude were similar (Fig. 1C) in the two species during saccades whose amplitude was less than 20-30 deg. The peak velocity of rhesus monkey gaze saccades tends to asymptote at 500-600 deg s−1, while no such asymptote was observed in squirrel monkeys. The head movements produced by squirrel monkeys during gaze saccades were, on average, nearly twice as fast, and had durations that were half as long as those produced by rhesus monkeys. As a result, the gaze stabilization component of their gaze saccades was much shorter in duration.

In summary, the active head movements that accompany gaze saccades in the squirrel monkey are relatively short in duration and high in speed. They contribute significantly to gaze velocity during the active gaze shift because the gain of the VOR is reduced. The period of gaze stability produced by counter-rotation of the eyes after a gaze saccade is relatively short, but it is nonetheless an important fraction of the monkey's behaviour because of the high frequency with which they produce combined eye and head movements. In the remaining Results section of this paper the firing behaviour of central vestibular neurons that are putatively involved in controlling the VOR during gaze saccades are described.

Classification of eye movement-related vestibular nucleus neurons

The firing behaviour of 137 horizontal canal-related vestibular nucleus neurons was recorded during combined eye and head gaze saccades in monkeys that were free to move their head in the horizontal plane. This paper reports on 57 vestibular neurons that were sensitive to eye movements. The firing behaviour of non-eye movement-related neurons has been described in a previous paper (McCrea et al. 1999).

Eye movement-related vestibular neurons were divided into different classes based on their responses during whole body rotation, steady fixation and smooth pursuit eye movements. The firing behaviour of each class of cell in the squirrel monkey during smooth pursuit, VOR cancellation and whole body rotation and during passive neck rotation have previously been described (Cullen et al. 1993a; Cullen & McCrea 1993; Chen-Huang & McCrea 1999; Gdowski & McCrea 1999, 2000; Gdowski et al. 2001). Most of the eye movement-related neurons tested (36/48) were monosynaptically activated following electrical stimulation of the ipsilateral vestibular nerve.

Position-vestibular neurons

The tonic firing rate of PV neurons was related to eye position during steady fixation and smooth pursuit eye movements. They were not sensitive to eye velocity during ocular saccades or pursuit, although their firing rate was correlated with changes in eye position. Fourteen PV neurons were recorded. These included cells that had responses in phase with ipsilateral (n = 8; PVI units) or contralateral (n = 6; PVII units) head velocity during whole body rotation. Most PVII neurons (5/6 tested) could be activated following electrical stimulation of the vestibular nerve, while most PVI neurons (6/7 tested) could not be activated even when stimulus currents were applied that were more than twenty times the threshold for evoking monosynaptic field potentials in the vestibular nuclei (1 mA). The two PV cell types exhibited different firing behaviour during gaze saccades.

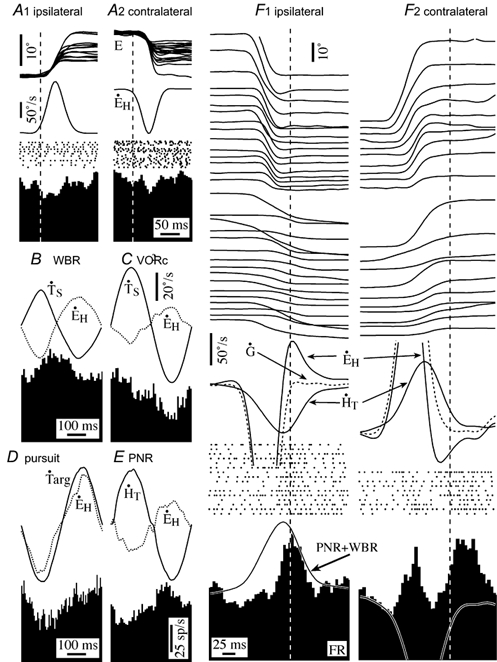

The firing rate of PVI neurons was related to ipsilateral head velocity, contralateral neck velocity and contralateral eye position. All of the signals summed linearly during gaze saccades. The PVI cell illustrated in Fig. 2 was more sensitive to active head movements during gaze saccades than any other eye movement-related vestibular neuron encountered. During ocular saccades its firing rate reflected the change in eye position produced by the saccade (Fig. 2A1 and A2). Its firing rate was strongly modulated in phase with ipsilateral head velocity during WBR (Fig. 2B). Passive neck rotation (produced by rotation of the body while holding the head stable in space) also modulated its firing rate (Fig. 2C). This neck proprioceptive input was opposite to and smaller than the vestibular signal evoked during WBR, and summed linearly with it during passive rotation of the head on the trunk (Fig. 2D).

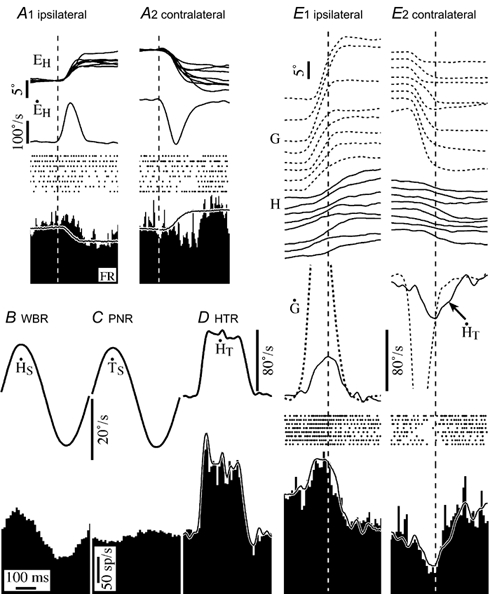

Figure 2. Firing behaviour of a type I position-vestibular cell during passive and active head movements.

A1 and 2, responses during ocular saccades in the ipsilateral and contralateral direction. Saccades are arranged in order of increasing amplitude and aligned on gaze onset. Shown are eye position for each saccade, average eye velocity, spike rasters for each saccade and the average firing rate. The model superimposed on the average firing rate histogram is based on the cell's static eye position sensitivity (ks = 6.1 sp s−1 deg−1). B, average response during passive whole body rotation (WBR, 2.3 Hz, 20 deg s−1). C, cycle averaged response of the cell to passive neck rotation. D, response to passive head-on-trunk rotation velocity trapezoid. The model superimposed on the firing rate histogram is based on its sensitivity to head velocity (gv = 2.6 sp deg−1 s−2) and head acceleration (ga = 0.07 sp deg−1 s−3) during WBR, neck velocity (nv = 0.6 sp deg−1 s−2) during PNR and eye position. E1 and 2, average response during eight gaze saccades in the contralateral and ipsilateral direction. Saccades are arranged in order of increasing amplitude and aligned on peak head velocity (dashed vertical lines). Shown are gaze and head position, and average gaze and head velocity for each saccade. The model superimposed on the average firing rate histograms is the same as the one in D. Abbreviations: EH, eye position; E’H, eye velocity; PNR, passive neck rotation; HT, head-on-trunk position; H’T, head-on-trunk velocity; H’S, head-in-space velocity; G, gaze position; G’, gaze velocity.

The PVI cell's response during gaze saccades is shown in Fig. 2E1 and E2. The saccades chosen for inclusion in E1 had peak head velocity and acceleration comparable with the passive head movement produced during head-on-trunk rotation (HTR) in Fig. 2D. The traces superimposed on the firing rate histograms in Fig. 2D and E represent the predicted response based on a linear summation of the eye position, vestibular and neck proprioceptive signals determined from the experiments shown in Fig. 2A-C. The similarity of the model to the firing behaviour of this vestibular neuron, like all PVI cells, was similar during both passive and active head movements.

In comparison to PVI cells, most PVII cells (5/6) were insensitive to active head movements during gaze saccades. Their firing rate was related primarily to eye position during gaze saccades. The firing behaviour of a PVII neuron during gaze saccades is illustrated in Fig. 3. Its firing rate was strongly related to contralateral head velocity (gain re contralateral head velocity = 1.9 sp deg−1 s−2) during WBR (Fig. 3A), and it was sensitive to ipsilateral eye position. The cell's response during ipsilateral and contralateral gaze saccades is shown in Fig. 3B1 and B2. It was insensitive to active head movements during gaze saccades. The expected response, based on the cell's sensitivity to passive rotation and to eye position is superimposed on the firing rate histograms. Firing rate increased during ipsilateral saccades and decreased during contralateral saccades due to the fact that the cell was sensitive to ipsilateral eye position. The insensitivity to head movements was similar for large and small saccades. The head movement insensitivity was present both during the saccadic gaze shift and the gaze stabilization period immediately after saccades. The vestibular signals of five of the six PVII cells were similarly cancelled during active head movements. One PVII cell remained sensitive to head movements during gaze saccades, although its response was attenuated by approximately 35 %. The three PVII units that were studied during passive head-on-trunk rotation and during passive trunk rotation with respect to the head were only weakly modulated during passive neck rotation, and they remained sensitive to passive head-on-trunk rotation. Consequently, neck proprioceptive inputs were probably not the source of input responsible for the insensitivity of PVII cells to active head movements.

Figure 3. Firing behaviour of a type II, position-vestibular cell during passive and active head movements.

A, cycle averaged response during passive whole body rotation (2.3 Hz, 20 deg s−1). B, responses during ocular saccades in the ipsilateral and contralateral direction. The model superimposed on the average firing rate histogram is based on the cell's static eye position sensitivity (ks = 3.0 sp s−1 deg−1). B and C, average response during eight gaze saccades in the ipsilateral (1) and contralateral (2) direction. Saccades are arranged in order of increasing amplitude and aligned on peak head velocity. The model superimposed on the firing rate histogram is based on the cell's sensitivity to eye position (3.0 sp s−1 deg−1) and head velocity (0.65 sp deg−1 s−2). Abbreviations are the same as in Fig. 2.

In sum, some position-vestibular neurons, particularly PVI neurons, were more sensitive to active head movements during gaze saccades than any other class of vestibular neuron encountered. On the other hand, most PVII neurons were not sensitive to active head movements during gaze saccades. Both types of PV cells exhibited relatively symmetrical responses to ipsilateral and contralateral active and passive head movements.

Position-vestibular-pause neurons

The majority of the eye movement-related cells encountered were position-vestibular-pause (PVP) neurons (n = 30). In the squirrel monkey, this class of vestibular neuron receives direct inputs from the ipsilateral vestibular nerve and projects to the abducens nucleus or to the medial rectus subdivision of the oculomotor nucleus (McCrea et al. 1987; Chen-Huang & McCrea 1999). Electrical stimulation of the ipsilateral vestibular nerve monosynaptically activated all but one of the PVP cells tested (21/22). All the cells were sensitive to ipsilateral head velocity during passive WBR (Fig. 4A). During ocular pursuit, PVPs fired in phase with contralateral eye velocity. The cells also had tonic firing rates that were related to contralateral eye position and were usually inhibited during ocular saccades in all directions (Fig. 4B1 and B2). The pause or inhibition typically lasted throughout the duration of the ocular saccade.

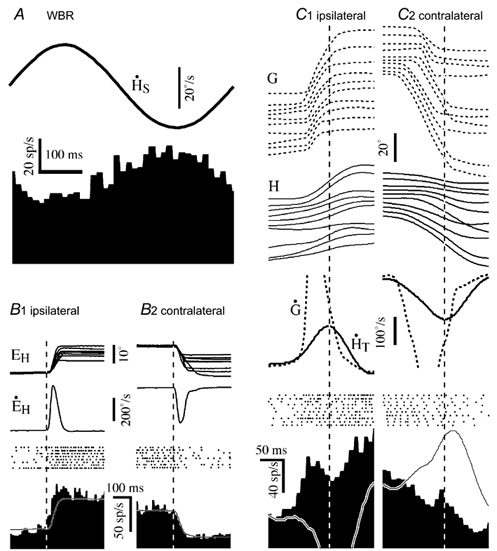

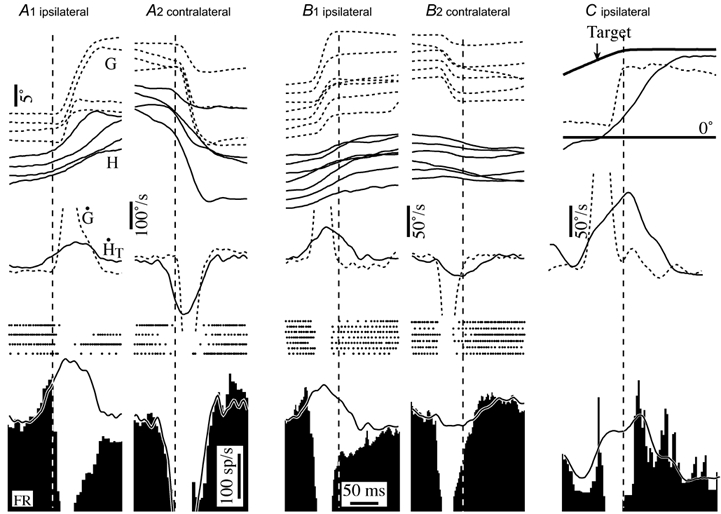

Figure 4. The firing behaviour of a position-vestibular-pause neuron during active saccadic gaze shifts.

A, average response during passive whole body rotation (2.3 Hz, 20 deg s−1). B, response during ocular saccades in the ipsilateral (B1) and contralateral (B2) direction. Saccades are arranged in order of increasing amplitude and aligned on saccade onset. C, average response during gaze saccades in the ipsilateral (C1) and contralateral (C2) direction. The traces, show, from top to bottom the gaze trajectory (G) of individual gaze saccades, the corresponding head movements (HT), the spike rasters associated with each saccade, the average head velocity re trunk (H’T) and gaze velocity (G’) associated with the group of illustrated saccades and a histogram showing average response of the neuron. Superimposed model on the average firing rate histogram is based on the cell's vestibular sensitivity to head movement during passive WBR. Firing rate calibration in C also applies to A and B. Time calibration in C also applies to B. Abbreviations are the same as in Fig. 2.

PVP cells were also inhibited during the active gaze shift period of gaze saccades. The responses of a PVP cell during gaze saccades of different sizes that were spontaneously generated in the absence of a visual target are shown in Fig. 4C1 and C2. The records are aligned on peak head velocity and arranged in order of increasing saccade amplitude. The neuron was inhibited during saccades. The inhibition typically began slightly before the onset of the saccade and persisted throughout the duration of the active gaze shift. The duration of the inhibition tended to increase as the duration of the saccade increased. The inhibition often persisted longer than the gaze saccade, although the cell slowly resumed firing at a new tonic rate that varied, depending on the final eye position. Similar responses were observed in most of the 30 PVP cells that were studied. All the cells were inhibited during ipsiversive gaze saccades. A few cells (5/30) were not inhibited during contraversive ocular saccades. The response of these cells during contraversive gaze saccades was similar to PVI cells, and was related to the change in eye position and head velocity.

PVP responses during periods of stabilized gaze before and after gaze saccades

The active head movements produced during spontaneous gaze saccades were sometimes initiated before the gaze shift and usually lasted long after the gaze shift was completed. In each case, the gaze position in space tended to be stabilized by eye movements produced in the opposite direction to the active head movement. Although the functional consequence of the eye movements during each period was to stabilize gaze, the firing behaviour of PVP cells was different in the two circumstances.

PVP cells were sensitive to active head movements that preceded gaze saccades. Figure 5 shows the same cell as in Fig. 4, but the traces are aligned on periods in which gaze remained stable while the head was moving. When head movements preceded the onset of the saccadic gaze shift (Fig. 5A), the cell's firing rate decreased or increased proportionally with respect to its vestibular sensitivity (continuous trace superimposed on firing rate histograms) until the beginning of the gaze shift when it started to pause.

Figure 5. Firing behaviour of PVP neurons during active head movements related to periods of gaze stabilization preceding and following gaze saccades.

A1 and 2, responses of a PVP neuron during ipsilateral and contralateral gaze saccades that had head movements that preceded the saccadic shift. Saccades are arranged in order of increasing amplitude and aligned on gaze onset. B1 and 2, responses during ipsilateral and contralateral gaze saccades that had head movements that persisted after the saccadic gaze shift. Records were temporally aligned on the end of the gaze shift. C, firing behaviour of a PVP neuron during the gaze stabilization component of gaze saccades produced in the presence of a visual target. Superimposed traces on the average firing rate histograms are models based on the cell's sensitivity to eye position and to head movements during passive whole body rotation at 2.3 Hz. The cell illustrated is the same one shown in Fig. 4. Abbreviations are the same as in Fig. 2.

When the saccade-related pause in firing rate ended, the sensitivity of PVP cells to the ongoing active head movement was dependent on the saccade direction and the presence of a visual target. The records in Fig. 5B and C are aligned on periods of gaze stability immediately after gaze saccades when the head was still moving. In the absence of a visual target the PVP cell's firing rate was poorly related to ipsilateral head movements immediately after saccades (Fig. 5B1), although it remained sensitive to contralateral head movements. Similar asymmetry was observed in all 30 of the PVP cells studied. The insensitivity to ipsiversive active head movements immediately after saccades was not evident when the monkeys directed their gaze to an earth stationary or moving visual target (Fig. 5C).

Sensitivity of PVP cells to passive vestibular stimulation during gaze saccades

PVP cells were inhibited during gaze saccades and were insensitive to ipsiversive active head movements during the gaze stabilization period after gaze saccades when visual targets were not present, but they remained sensitive to both ipsiversive and contraversive passive head movements during gaze saccades. Figure 6 shows an analysis of the passive head movement sensitivity of the PVP cell during active head movements produced during whole body rotation (WBR) at 2.3 Hz. The cycle averaged response of the cell during WBR when the head was restrained from moving is shown in Fig. 6A. In Fig. 6B, the averaged response of the cell during active head movements when the head was free to move during WBR is illustrated. The analysis included only those records that were concurrent with active head movements immediately after gaze saccades. Portions of records in which the cell was silenced were excluded. Since the active head movements were generated during whole body rotation, the average head velocity in space was a combination of active and passive head movement in space.

Figure 6. Firing behaviour of a PVP neuron during combined passive and active head movements.

All the records are cycle-averaged responses recorded during 2.3 Hz whole body rotation. The responses shown in A were recorded during passive whole body rotation with the head restrained. Records related to saccades were excluded. The responses shown in B were recorded with the head free. Only records that were concurrent with the gaze stabilization period immediately following gaze saccades were included in the analysis. These records were cycle averaged with respect to the passive stimulus. Note that the mean firing rate was significantly reduced during active head movements. The continuous trace superimposed on the firing rate histogram is the response expected due to passive head movement produced by turntable rotation. The dotted trace superimposed on it is the response expected due to velocity of the head in space produced by active and passive head movements. The figure illustrates that the neuron was as sensitive to passive whole body rotation immediately after gaze saccades as it was when the head was restrained from moving. The neuron's insensitivity to ipsiversive saccadic head movements is reflected in the difference between the expected averaged response and the actual response. The cell illustrated is the same one as shown in Fig. 4. Ipsiversive turntable, head and eye velocity are upward deflections.

The continuous trace superimposed on the firing rate histogram in Fig. 6B represents the expected response to passive head movement in space produced by turntable rotation. The dotted trace represents the expected response to combined passive and active head movements. The PVP cell remained sensitive to passive head velocity in space and to head velocity related to contralateral head movements but was insensitive to the ipsilateral active head movement component of head velocity in space. Similar observations were made in 20 other PVP cells that were analysed in the same manner.

Eye-head-velocity vestibular neurons

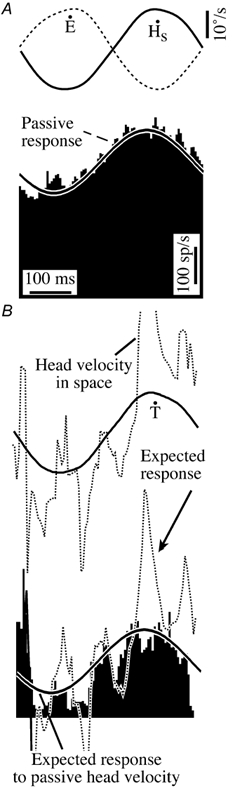

Squirrel monkey eye-head-velocity vestibular neurons are secondary vestibular neurons that are particularly sensitive to ocular pursuit eye movements and to VOR cancellation during passive WBR (Chen-Huang & McCrea, 1999). They are sensitive to head velocity during WBR, to eye velocity during smooth pursuit eye movements and to passive neck rotation velocity (Gdowski & McCrea, 2000; Gdowski et al. 2001). When the VOR is cancelled by fixation of a head stationary target, their response to head rotation often reverses in direction. The responses of nine EHV cells were recorded during horizontal gaze saccades. Six of the cells were activated at monosynaptic latencies following electrical stimulation of the ipsilateral vestibular nerve. Two of the remaining three cells were activated at a disynaptic latency (1.5-1.7 ms) when strong stimulus currents were used. Three cells generated bursts of spikes during ocular saccades in all directions. The other cells, like the one illustrated in Fig. 7, were not sensitive to ocular saccades in any direction.

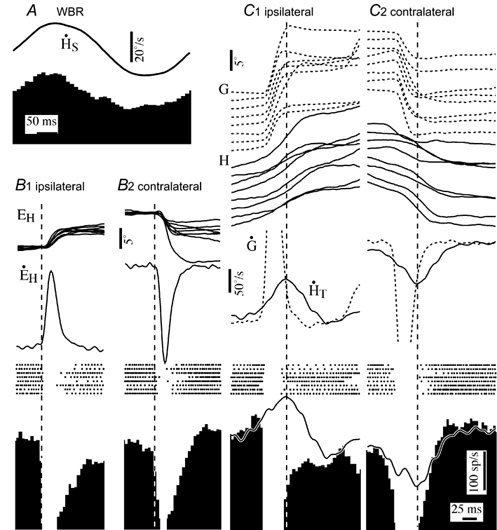

Figure 7. Firing behaviour of a type II EHV neuron during active and passive gaze shifts.

A, the neuron was not sensitive to saccadic eye movements either in the ipsilateral (A1) or contralateral (A2) direction. The cell's firing rate was weakly modulated during passive whole body rotation (WBR, B), but it was sensitive to ipsilateral head velocity during VOR cancellation (C) and ipsilateral eye velocity during ocular pursuit (D). It was also sensitive to passive neck rotation (PNR, E). The cell's discharge rate was excited during the gaze stabilization period during both ipsilateral (F1) and contralateral (F2) gaze saccades. Records in F are temporally aligned on the end of the gaze shift. The firing rate during ipsiversive slow phases of VOR eye movements evoked by head movements in the gaze stable period was predictable from the cells sensitivity to passive head rotation (trace superimposed on response in F1). The complex response of the cell during and after contralateral gaze saccades could not be explained by its sensitivity to passive stimuli. Abbreviations are the same as in Fig. 2.

Most EHV cells were only weakly affected by active head movements during the active gaze shift component of gaze saccades. The cells that were sensitive to ocular saccades tended to have smaller responses when head movements contributed to the gaze shift. The firing rate of the other cells was only weakly modulated during gaze saccades. On the other hand, the firing rate of EHV cells was modulated during the gaze stabilization component of gaze saccades; particularly when visual targets were absent.

Figure 7 illustrates the responses of an EHV neuron in a variety of behavioural circumstances. It was unresponsive during ocular saccades in both the ipsilateral and contralateral direction (A), and its firing rate was poorly correlated with eye position. The neuron's firing rate was strongly modulated during ipsilateral smooth pursuit eye movements (D), ipsilateral head movements during VOR cancellation (C), and neck velocity during passive neck rotation (E). During passive WBR in the head restrained condition, the cell’ s firing rate was modulated both in the presence (B) and absence of earth stationary targets.

EVH cells were not sensitive to the component of gaze saccades related to the active gaze shift, but their firing rate was strongly modulated during the gaze stabilization component of ipsilateral gaze shifts. This modulation was proportional to the amplitude of the head movement associated with the gaze saccade. Figure 7F illustrates the responses of an EHV cell during gaze saccades that had similar duration of gaze stabilization at the end of the active gaze shift (shaded area in diagram). Responses are aligned on the end of the gaze shift in order of increasing size of the head movement component of the gaze saccade. The trace superimposed on the average firing rate histogram shows the responses expected during the gaze stable period, based on the cell's sensitivity to passive head movements during whole body rotation and to passive neck rotation. The cell was unresponsive during ipsilateral saccadic gaze saccades and was weakly excited during contralateral gaze saccades. It generated a burst of spikes during the gaze stable period following ipsiversive gaze saccades that was related to the VOR eye velocity. The onset of the burst led the onset of the gaze stabilization period of the saccade and reached its peak at approximately the same time as peak contralateral head velocity and peak ipsilateral compensatory eye velocity. During the gaze stable period following contralateral gaze saccades the cell was also excited; although the discharge rate was not strongly related to VOR eye velocity.

All the EHV cells recorded were similarly responsive to compensatory rollback eye movements in their preferred eye movement direction during gaze saccades. Cells that were sensitive to contralateral eye velocity during smooth pursuit increased their firing rate in phase with contralateral eye velocity during the gaze stabilization period of ipsilateral saccades, while those that were sensitive to ipsilateral eye velocity were sensitive to compensatory eye movements during the gaze stabilization period of contralateral saccades. The response was roughly proportional to the cell's sensitivity to passive WBR and to passive neck rotation (continuous line superimposed on cell firing rate histogram in Fig. 7F1). EHV cells either failed to respond during VOR eye movements in the non-preferred direction or were excited like the cell illustrated in Figure 7. As noted above, some EHV cells had a burst of activity during ocular saccades in all directions. In those cells, the burst in the preferred direction was enhanced during the period of gaze stabilization, while the burst in the non-preferred direction usually did not outlast the active gaze shift.

In sum, EHV cells generated a signal late in the saccade that appeared to be related primarily to the postsaccadic rollback eye movement that stabilizes gaze when the saccade is in the neuron's preferred eye movement direction. The signal was not present during saccades in their non-preferred direction. The asymmetry in EHV neuron responses was opposite to the asymmetry observed in PVP neurons, which were insensitive to postsaccadic head movements in their preferred direction.

Discussion

Squirrel monkeys have a relatively small oculomotor range. Consequently, a large fraction of the spontaneous gaze shifts they produce involve combined eye and head movements. Saccades larger than 10 deg in amplitude are produced primarily by the addition of an angular head-on-trunk rotation, which increases not only the amplitude, but also the speed of the gaze shift. The contribution of head movements to gaze velocity is possible because the VOR evoked by active head movements is suppressed during gaze saccades. Near the end of gaze saccades a compensatory eye movement is produced that is mediated by central VOR pathways. The central signals that produce this rollback eye movement appear to be complex and context dependent. The complex nature of the compensatory eye movements that accompany gaze saccades probably reflects necessary differences in the neural processing required when a gaze shift carries the eye to a target that is outside the oculomotor range and when it is directed to a target within the common oculomotor range.

The vestibular signals related to active head movements during saccadic gaze shifts were reduced in amplitude or absent in most of the neurons that putatively contribute to central VOR pathways. Some cells (e.g. PVI cells) were only fractionally less sensitive to active head movements. But other cells, e.g. PVII cells, were practically insensitive to active head movements during gaze saccades. The reduction was most dramatic in PVP neurons, which in most cases ceased firing during the gaze shift. The removal of vestibular signals allowed concurrent active head movements to contribute to gaze velocity during the saccade. Near the end of the saccade central VOR pathways resumed generating signals that produce compensatory eye movements. However, those active head movement signals were often different from those produced during passive whole body rotation; particularly in the absence of visual targets.

The two major classes of cells that have been previously identified as participating in producing the VOR - EHV and PVP neurons - both had asymmetric responses to head rotation during the rollback period of gaze saccades. The asymmetric response properties of the two classes of VOR neurons were complementary. PVP neurons were significantly less sensitive to ipsiversive saccadic head movements that increased the firing rate of ipsilateral vestibular nerve fibres, while EHV neurons exhibited an enhanced sensitivity. An analysis of the responses of these two classes of cells during passive neck rotation suggests that an internal efference copy of active head movements reduced the vestibular signals on PVP neurons, while the enhanced sensitivity of EHV neurons was attributable to inputs from neck proprioceptors (Gdowski et al. 2001).

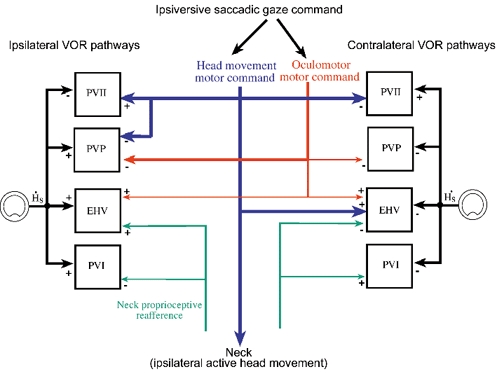

Figure 8 summarizes the signals that affect different classes of secondary VOR neurons in the vestibular nuclei during gaze saccades. Most of the cells receive inputs related to eye movements. PV, PVP and most EHV neurons receive inputs related to eye position. During gaze saccades PVP and some EHV neurons also receive inputs related to ocular saccade velocity. The ocular saccade input is typically not directionally tuned - most PVPs are inhibited during saccades in all directions and many EHVs are excited during ocular saccades in every direction. Many VOR neurons receive neck proprioceptive inputs. The inputs contribute significantly to responses during active head movements primarily in PVI and EHV neurons (Gdowski et al. 2001), but in no case are they comparable in strength to vestibular signals. Consequently, the insensitivity of PVP, EHV and type II PV neurons to active head movements during gaze saccades is likely to be primarily due to an input related to head movement motor commands or an efference copy of active head movement commands. Since the cancellation of vestibular reafferent signals was not initiated until the onset of saccades, one possibility is that the head movement efference copy signal is part of a saccadic gaze velocity motor command originating from collateral projections of saccade-related burst neurons to the vestibular nuclei (Cullen & Guitton, 1996; Roy & Cullen, 1998, 2002).

Figure 8. Convergence of head movement corollary discharge and sensory re-afferent inputs on different classes of secondary VOR neurons.

Four separate signals contribute to shaping the responses of secondary VOR neurons on both sides of the brain during saccadic gaze shifts and the VOR eye movements that are generated immediately after saccades. The relative strength of each signal is indicated by the thickness of the lines that connect the signals to each class of neurons. Each class of vestibular neuron receives inputs related to head movement in space from the vestibular nerve. Signals related to oculomotor saccadic commands inhibit most PVP neurons and excite many EHV neurons bilaterally during the ocular component of gaze saccades. The remaining EHV cells, and all PV neurons, are not sensitive to the ocular component of gaze saccades. Signals related to head movement motor commands affect the firing behaviour of most, but not all secondary VOR neurons, although the effects of the inputs are different in different cell classes. Head movement commands cancel active saccadic head movement-related vestibular signals in PVII and PVP neurons during gaze saccades. EHV neurons receive inputs related to active head movements that produce a burst of spikes during contraversive saccades. Many EHV and PVI cells receive neck proprioceptive inputs, which in most cases are relatively weak (Gdowski & McCrea, 2000, 2001). The neck inputs reduce the responses of PVI neurons and increase the responses of EHV neurons to active head movements. The results suggest that the signals that contribute to co-ordinating eye and head movements during gaze saccades arise from a variety of sources and affect signal processing of different neurons that contribute to the VOR in different ways.

Our observations suggest that an efference copy of gaze velocity commands is probably not the signal used to cancel vestibular signals on central VOR pathways during gaze saccades. The signals generated by most putative secondary VOR neurons during combined eye and head movements were not the simple sum of vestibular and gaze velocity commands. PVI neurons were sensitive to active head velocity but not to gaze velocity. PVII neurons were insensitive to both active head velocity and to gaze velocity. Most PVP neurons were inhibited during gaze saccades in all directions. An efference copy of a gaze velocity command would not be expected to inhibit those neurons when the gaze shift was in the neuron's eye movement on direction, but this is precisely what was observed. Most EHV neurons tended to be excited during gaze saccades in both directions, and thus were not well correlated with gaze velocity. In sum, few of the central neurons that are involved in producing the VOR show evidence of being sensitive to gaze velocity during gaze saccades or during the period of gaze stabilization immediately after the gaze shift.

The fact that secondary VOR neurons were not sensitive to gaze velocity suggests that separate oculomotor and head movement efference copy signals are sent to the vestibular nuclei (Fig. 8). This latter possibility is supported by the observation that the head saccade-related signals generated by many non-eye movement-related neurons in the vestibular nuclei are also suppressed by a head movement efference copy signal (McCrea et al. 1999; Roy & Cullen, 2001). Another possibility is that the efference copy signal is not related to a specific motor command, but is a descending signal that is proportional to the total expected sensory input produced by an active head movement.

One thing that is clear is that signal processing in different central VOR pathways during, and immediately after gaze saccades is affected in different ways.

Comparison of squirrel monkey gaze saccades to gaze saccades of other primates

The firing behaviour of EHV and PV neurons in rhesus monkeys during gaze saccades has not been described. In those primates, PVP neurons pause or are inhibited during gaze saccades (Roy & Cullen, 1998, 2002). They remain sensitive to active head movements during the postsaccadic rollback period, although the vestibular signals related to active head movements tend to be attenuated (Roy & Cullen, 1998, 2002). Most squirrel monkey PVP neurons paused during saccades in all directions, and were sensitive to postsaccadic rollback head movements when a visual target was present. However, the attenuation of active head movement signals in the postsaccadic rollback period was nearly complete in the absence of a visual target. It is not clear whether the rollback eye movements in rhesus monkeys are similarly linked to visual task.

Unfortunately there are several differences between the experimental protocols that make comparison of our data to that described in rhesus monkeys (Roy & Cullen, 1998, 2002) difficult. (1) The rhesus monkey saccade-related head movements published to date were relatively small in amplitude and slow in speed compared to those in this study. (2) Head movements were not confined to the horizontal canal plane, and presumably involved activation of vestibular afferents arising from otoliths, as well as all three semicircular canals. (3) The location of the neurons and their relationship. The rhesus PVP recordings were apparently obtained from a restricted subpopulation of unidentified PVP neurons that were not inhibited during contralateral saccades. The location those unrepresentative neurons and their relationship to the vestibular nerve were not reported. Most primate PVP neurons pause during saccades in all directions (King et al. 1977; Tomlinson & Robinson, 1984). (4) Finally, the firing behaviour of PVP neurons was apparently only recorded in the presence of visual targets. This last difference may be significant, since the signals generated by most cerebellar flocculus Purkinje cells, which have powerful effects on central VOR pathways, are strongly affected by the presence of visual targets (Belton & McCrea, 2000).

In squirrel monkeys the firing rate of many PVP and PV neurons is weakly modulated by passive neck rotation (Gdowski et al. 2001). These neck afferent-driven signals are linked to cervico-ocular reflex eye movements, which are abolished when a visual target is fixated. A similar lack of modulation in PVP neurons during target fixation has recently been reported in rhesus monkeys (Roy & Cullen, 2002). The neck afferent inputs to squirrel monkey EHV neurons are somewhat stronger than in PVP neurons, and may be responsible for their increased sensitivity to active head-on-trunk movements. Similar tests have not been carried out in rhesus monkey EHV neurons.

In any case, it seems likely that squirrel monkeys have a larger propensity to use mechanisms of gaze control that are normally active only during very large gaze saccades in larger primates. The increased propensity to use head movements to produce changes in the direction in gaze is possibly due to several factors.

(1) Squirrel monkeys have smaller and lighter heads than rhesus monkeys or humans. The relatively low inertia of the squirrel monkey head/neck plant reduces the muscular force needed to produce rapid head movements. The increased head movement propensity is reflected as a relatively larger contribution of head movements to gaze shifts that occur over a short duration. If inertial forces can be regarded as ‘passive’, rather than active head movements, then it is possible that some of the differences in behaviour and central neural responses are due to the larger passive component of head movement that accompanies active head movements in larger primates.

(2) Squirrel monkeys have a smaller interocular distance than rhesus monkeys and humans, and the distance of their eyes from the axis of head rotation is smaller. Consequently, active head rotation produces a smaller linear vestibulo-ocular reflex.

(3) Squirrel monkeys have a smaller oculomotor range than rhesus monkeys and humans. Since their oculomotor range is smaller, a relatively large propensity to produce head movements is necessary in order to produce gaze shifts over the same dynamic range. In humans and rhesus monkeys, the range of horizontal eye movements extends more than 50 deg in each direction (Freedman & Sparks, 2000). The relationship between squirrel monkey saccade amplitude and gaze velocity was similar to that observed in rhesus monkeys for smaller saccades. However, during large gaze shifts the peak gaze velocity of saccades tends to asymptote at about 600 deg s−1 in rhesus monkeys, while the peak gaze velocity generated during large saccades in squirrel monkeys continued to rise. The limit on peak gaze velocity may not be entirely due to mechanical factors.

(4) Finally, the requirements for accurate gaze control are probably larger in squirrel monkeys than in rhesus monkeys and humans. Squirrel monkeys are arboreal animals whose survival depends on accurate gaze control in a complex three-dimensional environment. Failure to stabilize the image of a tree branch that is to be grasped in moving from place to place in a tree could be fatal. Part of the strategy for accurately judging the position of images with respect to the body may be to independently control eye and head movements and to minimize the duration of saccadic head movements. The peak velocity and acceleration of the head movement component of their saccades tends to be higher, which allows the duration of their saccadic head movements to be relatively short (usually less than 250 ms). In larger, terrestrial primates it might not be necessary to generate the larger forces required to produce comparable head movements.

Asymmetrical and nonlinear signal processing in central VOR pathways during gaze saccades

There is circumstantial evidence that signal processing in central VOR pathways is asymmetrical during head movements that have high accelerations and velocities. Patients with unilateral labyrinthine disease exhibit persistent asymmetries in their response to high acceleration head thrusts, although the VOR response to slower head movements recovers rapidly (Halmagyi et al. 1990; Lasker et al. 1999). The persistent asymmetry is due, in part, to non-linear processing of vestibular nerve activity in central VOR pathways (Lasker et al. 1999; Minor et al. 1999).

The neural pathways that mediate the VOR have been described as being divided into linear and non-linear components (Minor et al. 1999). The linear pathways are driven primarily by regular vestibular nerve afferents and are sufficient to produce the VOR during low frequency, low velocity head movements. The non-linear pathways make significant contributions to the VOR during high frequency and high velocity head movements, although their effects on contraversive head movements are small compared with their effects on ipsiversive head movements (Lasker et al. 1999). The relatively ineffective transmission of irregular afferent signals through vestibular commissural pathways may also contribute to the asymmetry at high frequencies (Chen-Huang et al. 1997).

Our observations support the idea that the pathways that mediate the angular VOR rely on a mixture of linear and non-linear elements. The signals produced by PVI neurons during gaze saccades were symmetric and predictable from their responses to low frequency passive head rotation. This class of vestibular neuron receives primarily regular vestibular nerve afferent inputs (Chen-Huang et al. 1997). In contrast, the head movement-related signals produced by PVP and EHV neurons were asymmetric immediately after gaze saccades; particularly when no visual target was present.

The asymmetry in PVP neuronal responses during gaze saccades could reflect non-linear processing of irregular afferent inputs. PVP neurons receive direct, monosynaptic inputs from irregular afferents as well as inputs that arise from indirect pathways (Chen-Huang et al. 1997). These inputs arise almost exclusively from the ipsilateral nerve, and have nearly equal excitatory and inhibitory effects. Galvanic ablation of irregular afferent inputs has little effect on the total output of PVP neurons during passive head rotation at low rotational velocities. However, during high acceleration saccadic head movements the contribution of the cancellation of inhibitory and excitatory irregular afferent inputs may be less perfect.

The reduction in the output of PVP neurons during the postsaccadic gaze stabilization period is compensated in part by an increase in the responses of EHV neurons. These secondary vestibular neurons project to ipsilateral medial and lateral rectus motoneurons. They receive inputs from the cerebellar flocculus, which in turn receives mossy fibre inputs from vestibular neurons that have considerable irregular vestibular inputs (McCrea et al. 1987). They also receive substantial neck proprioceptive inputs that code head-on-trunk velocity during passive trunk rotation (Gdowski & McCrea, 2000; Gdowski et al. 2001). Many exhibit an increased sensitivity to active head movements during ipsiversive saccades (T. Belton & R. A. McCrea, unpublished observation). The increased sensitivity could have been due to addition of vestibular inputs from flocculus Purkinje cells or neck proprioceptive inputs. One mechanism for compensating for non-linear processing in PVP neurons during active head movements may be to increase neck re-afferent or vestibular inputs to EHV neurons.

Conclusions

Most central vestibular neurons that contribute to VOR pathways are differentially sensitive to active and passive head movements both during and after gaze saccades. The differential sensitivity is produced by the addition of head movement efference copy and neck proprioceptive re-afferent signals which reduce or enhance responses to head rotation related to the saccades. The relative insensitivity of central VOR pathways to active saccadic head movements produces a reduction in the gain of the VOR and an increase in the speed of saccadic gaze shifts, and allows for the possibility of separately controlling eye and head movements during saccadic gaze shifts.

Secondary VOR neurons resume coding active head movements during the period immediately after saccadic gaze shifts when gaze is stabilized, although in most the return of head movement sensitivity is asymmetric. The asymmetry may reflect differential processing of regular and irregular vestibular nerve afferent inputs to VOR pathways during gaze saccades, and could contribute to the persistent asymmetry in the short latency VOR that has been observed in unilateral labyrinthine deficient patients.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Tim Belton and Hongge Luan for their help in obtaining data used in this manuscript. This work was supported by NIH R01-EY08041.

References

- Barr CC, Schultheis LW, Robinson DA. Voluntary, non-visual control of the human vestibulo-ocular reflex. Acta Otolaryngol (Stockh) 1976;81:365–375. doi: 10.3109/00016487609107490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belton T, McCrea RA. Role of the cerebellar flocculus region in the coordination of eye and head movements during gaze pursuit. J Neurophysiol. 2000;84:1599–1613. doi: 10.1152/jn.2000.84.3.1614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bizzi E, Kalil RE, Morasso P. Two modes of active eye-head coordination in monkeys. Brain Res. 1972;40:45–48. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(72)90104-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen-Huang C, McCrea RA. Viewing distance related sensory processing in the ascending tract of deiters vestibulo-ocular reflex pathway. J Vestibular Res. 1998;8:175–184. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen-Huang C, McCrea RA. Effects of viewing distance on the responses of horizontal canal-related secondary vestibular neurons during angular rotation. J Neurophysiol. 1999;81:2517–2537. doi: 10.1152/jn.1999.81.5.2517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen-Huang C, McCrea RA, Goldberg JM. Contributions of regularly and irregularly discharging vestibular-nerve inputs to the discharge of central vestibular neurons in the alert squirrel monkey. Exp Brain Res. 1997;114:405–422. doi: 10.1007/pl00005650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cullen KE, Chen-Huang C, McCrea RA. Firing behavior of brain stem neurons during voluntary cancellation of the horizontal vestibuloocular reflex. II. Eye movement related neurons. J Neurophysiol. 1993a;70:844–856. doi: 10.1152/jn.1993.70.2.844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cullen KE, Guitton D. Inhibitory burst neuron activity encodes gaze, not eye, metrics and dynamics during passive head on body rotation. Evidence that vestibular signals supplement visual information in the control of gaze shifts. Ann NY Acad Sci. 1996;781:601–606. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1996.tb15735.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cullen KE, Guitton D. Analysis of primate IBN spike trains using system identification techniques. II. Relationship to gaze, eye, and head movement dynamics during head-free gaze shifts. J Neurophysiol. 1997;78:3283–3306. doi: 10.1152/jn.1997.78.6.3283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cullen KE, Guitton D, Rey CG, Jiang W. Gaze-related activity of putative inhibitory burst neurons in the head-free cat. J Neurophysiol. 1993b;70:2678–2683. doi: 10.1152/jn.1993.70.6.2678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cullen KE, McCrea RA. Firing behavior of brain stem neurons during voluntary cancellation of the horizontal vestibuloocular reflex. I. Secondary vestibular neurons. J Neurophysiol. 1993;70:828–843. doi: 10.1152/jn.1993.70.2.828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cullen KE, Roy JE, Sylvestre PA. Signal processing by vestibular nuclei neurons is dependent on the current behavioral goal. Ann NY Acad Sciences. 2001;942:345–363. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2001.tb03759.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freedman EG, Sparks DL. Coordination of the eyes and head, movement kinematics. Exp Brain Res. 2000;131:22–32. doi: 10.1007/s002219900296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gdowski GT, Belton T, McCrea RA. The neurophysiological substrate for the cervico-ocular reflex in the squirrel monkey. Exp Brain Res. 2001;140:253–264. doi: 10.1007/s002210100776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gdowski GT, McCrea RA. Integration of vestibular and head movement signals in the vestibular nuclei during whole-body rotation. J Neurophysiol. 1999;82:436–449. doi: 10.1152/jn.1999.82.1.436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gdowski GT, McCrea RA. Neck proprioceptive inputs to primate vestibular nucleus neurons. Exp Brain Res. 2000;135:511–526. doi: 10.1007/s002210000542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guitton D, Munoz DP, Galiana HL. Gaze control in the cat: studies and modeling of the coupling between orienting eye and head movements in different behavioral tasks. J Neurophysiol. 1990;64:509–531. doi: 10.1152/jn.1990.64.2.509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halmagyi GM, Curthoys IS, Cremer PD, Henderson CJ, Staples M. Head impulses after unilateral vestibular deafferentation validate Ewald's second law. J Vestibular Res. 1990;1:187–197. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Highstein SM, McCrea RA. The anatomy of the vestibular nuclei. In: Büttner-Ennever JA, editor. Reviews of Oculomotor Research. Amsterdam: Elsevier; 1988. pp. 177–202. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King WM, Lisberger SG, Fuchs AF. Responses of fibers in medial longitudinal fasciculus (MLF) of alert monkeys during horizontal and vertical conjugate eye movements evoked by vestibular or visual stimuli. J Neurophysiol. 1976;39:1135–1149. doi: 10.1152/jn.1976.39.6.1135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lasker DM, Backous DD, Lysakowski A, Davis GL, Minor LB. Horizontal vestibuloocular reflex evoked by high-acceleration rotations in the squirrel monkey. II. Responses after canal plugging. J Neurophysiol. 1999;82:1271–1285. doi: 10.1152/jn.1999.82.3.1271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laurutis VP, Robinson DA. The vestibulo-ocular reflex during human saccadic eye movements. J Physiol. 1986;373:209–233. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1986.sp016043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCrea RA, Chen-Huang C, Belton T, Gdowski GT. Behavior contingent processing of vestibular sensory signals in the vestibular nuclei. Ann NY Acad Sci. 1996;781:292–303. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1996.tb15707.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCrea RA, Gdowski GT, Boyle R, Belton T. Firing behavior of vestibular neurons during active and passive head movements: vestibulo-spinal and other non-eye-movement related neurons. J Neurophysiol. 1999;82:416–428. doi: 10.1152/jn.1999.82.1.416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCrea RA, Strassman A, May E, Highstein SM. Anatomical and physiological characteristics of vestibular neurons mediating the horizontal vestibulo-ocular reflex of the squirrel monkey. J Comp Neurol. 1987;264:547–570. doi: 10.1002/cne.902640408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minor LB, Lasker DM, Backous DD, Hullar TE. Horizontal vestibuloocular reflex evoked by high-acceleration rotations in the squirrel monkey. I. Normal responses. J Neurophysiol. 1999;82:1254–1270. doi: 10.1152/jn.1999.82.3.1254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plotnik M, Goldberg JM. Excitatory response-intensity relations in afferents from the chinchilla's superior and horizontal cristae. Assoc Res Otolaryngol Abs. 2000:5223. [Google Scholar]

- Roy JE, Cullen KE. A neural correlate for vestibulo-ocular reflex suppression during voluntary eye-head gaze shifts. Nature Neurosci. 1998;1:404–410. doi: 10.1038/1619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roy JE, Cullen KE. Selective processing of vestibular reafference during self-generated head motion. J Neurosci. 2001;21:2131–2142. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-06-02131.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roy JE, Cullen KE. Vestibuloocular reflex signal modulation during voluntary and passive head movements. J Neurophysiol. 2002;87:2337–2357. doi: 10.1152/jn.2002.87.5.2337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scudder CA, Fuchs AF. Physiological and behavioral identification of vestibular nucleus neurons mediating the horizontal vestibuloocular reflex in trained rhesus monkeys. J Neurophysiol. 1992;68:244–264. doi: 10.1152/jn.1992.68.1.244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sparks DL. Conceptual issues related to the role of the superior colliculus in the control of gaze. Current Opinion Neurobiol. 1999;9:698–707. doi: 10.1016/s0959-4388(99)00039-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sparks DL, Freedman EG, Chen LL, Gandhi NJ. Cortical and subcortical contributions to coordinated eye and head movements. Vision Res. 2001;41:3295–3305. doi: 10.1016/s0042-6989(01)00063-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomlinson RD. Combined eye-head gaze shifts in the primate. III. Contributions to the accuracy of gaze saccades. J Neurophysiol. 1990;64:1873–1891. doi: 10.1152/jn.1990.64.6.1873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomlinson RD, Bahra PS. Combined eye-head gaze shifts in the primate. II Interactions between saccades and the vestibuloocular reflex. J Neurophysiol. 1986;56:1558–1570. doi: 10.1152/jn.1986.56.6.1558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]