Abstract

Diverse forms of GABAergic inhibition are found in the mature brain. To understand how this diversity develops, we studied the changes in morphology of inhibitory interneurons and changes in interneuron-mediated synaptic transmission in the rat dorsal lateral geniculate nucleus (dLGN). We found a steady expansion of the dendritic tree of interneurons over the first three postnatal weeks. During this period, the area around a thalamocortical cell from which GABAA inhibition could be elicited also expanded. Dendritic branching and burst firing in interneurons evolved more slowly. The distal dendrites of interneurons began to branch extensively after the third week, and at the same time burst firing appeared. The appearance of burst firing and an elaborated dendritic tree were accompanied by a pronounced GABAB inhibition of thalamocortical cells. Thus, GABA inhibition of thalamocortical cells developed from one type of GABAA inhibition (spatially restricted) in the young animal into two distinct types of GABAA inhibition (short- and long-range) and GABAB inhibition in the adult animal. The close temporal relationships between the development of the diverse forms of inhibition and the postnatal changes in morphology of local GABAergic interneurons in the dLGN suggest that postnatal dendritic maturation is an important presynaptic factor for the developmental time course of the various types of feedforward inhibition in thalamus.

GABAergic signalling has a variety of essential roles in the development of the central nervous system. There are reasons to believe that the diversity of GABAergic signalling increases through the postnatal development to provide the variety and precision of inhibitory processes required by the growing demands of the maturing brain. GABAA and GABAB receptor-mediated inhibition seem to mature with different time courses (Fukuda et al. 1993; Gaiarsa et al. 1995; Nurse & Lacaille, 1999), and the relative contribution of GABAA and GABAB inhibition of postsynaptic neurons seems to depend on the firing pattern (i.e. tonic discharge or burst firing) of presynaptic inhibitory neurons (Huguenard & Prince, 1994; Destexhe & Sejnowski, 1995; Kim et al. 1997; Zhu & Heggelund, 2001).

We examined the developmental relationships between GABAergic signalling and morphology and firing patterns of presynaptic inhibitory interneurons in the rat dorsal lateral geniculate nucleus (dLGN). The dLGN, which is the primary thalamic nucleus that relays visual information to the cortex in mammals, has relatively simple inhibitory circuits (Steriade et al. 1997; Zhu & Lo, 1999). Feedforward inhibition is mediated through intrinsic interneurons, and feedback inhibition through the thalamic reticular nucleus (Steriade et al. 1997). The feedforward inhibition is particularly interesting because the anatomical (Ralston, 1971; Rapisardi & Miles, 1984; Hamos et al. 1985) and physiological (Curró Dossi et al. 1992; Cox et al. 1998) evidence indicates that interneurons can provide inhibition via both dendro-dendritic and axo-dendritic synapses. These synapses allow the adult interneurons to generate multiple types of inhibition in thalamocortical cells (Ahlsén et al. 1984; Paré et al. 1991; Curró Dossi et al. 1992; Zhu & Heggelund, 2001). The interneurons can provide GABAA inhibition over a wide area of the visual field (long-range inhibition; Eysel et al. 1986; Zhu & Heggelund, 2001) presumably due to spatial summation across their dendrites that span a large area of the retinotopically organized dLGN. The interneurons can also provide slow GABAB inhibition that depends on burst firing of the interneurons (Zhu & Heggelund, 2001). Furthermore, GABAA and GABAB inhibition can both be dynamically changed by neuromodulators (Cox et al. 1998; Cox & Sherman, 2000; Zhu & Heggelund, 2001). For example, acetylcholine, which is normally released during arousal, seems to restrict the spatial summation range of interneurons through reduction of input resistance, and thereby changes long-range inhibition into a local, short-range inhibition (Zhu & Heggelund, 2001). In addition, acetylcholine reduces GABAB inhibition by suppressing burst firing in interneurons (Zhu & Heggelund, 2001). Thus, during arousal acetylcholine can change the feedforward inhibition from a pattern suitable for coarse and salient visual signals to one serving fine-grained visual signals. Here we studied how the various types of feedforward inhibition mature. We hypothesized that if the long-range GABAA inhibition depends on the extension of the dendrites of the interneurons, both characteristics should change in parallel with a similar developmental time course. Furthermore, if interneuron-mediated GABAB inhibition of thalamocortical cells requires burst firing of interneurons, the GABAB inhibition should develop in synchrony with the burst firing property of interneurons.

Methods

Experiments were performed in brain slices prepared from postnatal (P) 6- to 36-day-old rats, as previously described (Zhu & Lo, 1999; Zhu, 2000). All procedures used conformed with the guidelines, and the approval, of the Norwegian Animal Research Authority and the University of Virginia Animal Care and Use Committee. In brief, the rats were deeply anaesthetized by halothane and decapitated. The brain was then quickly removed and placed into cold (1-4 °C) physiological solution containing (mm): NaCl 125, KCl 2.5, NaH2PO4 1.25, NaHCO3 25, MgCl2 1, dextrose 25, CaCl2 2, at pH 7.4. Coronal slices containing dLGN, each 300-500 μm thick, were then cut from the tissue blocks in cold (0-4 °C), oxygenated physiological solution, using a microslicer. These slices were then transferred to warm (37.0 ± 0.5 °C), oxygenated physiological solution and kept for 20-60 min before recording.

Whole-cell recordings from thalamic interneurons and thalamocortical cells were made as described in previous studies (Zhu & Lo, 1999; Zhu & Heggelund, 2001). Patch electrodes were made from borosilicate tubing and their resistances were 3-7 MΩ with an intracellular solution containing (mm): potassium gluconate 115, Hepes 10, MgATP 2, MgCl2 2, Na2ATP 2, GTP 0.3, and KCl 20, at pH 7.3. Liquid junction potential was not subtracted. The input resistance of interneurons and thalamocortical cells was measured from the linear portion of the current versus steady-state voltage curve whereas the membrane time constant was obtained from trace fitting with a Simplex optimization algorithm (PulseFit software from Heka Elektronik, Germany). These two values were used to calculate the cell membrane capacitance. Synaptic responses were examined using only slices without the thalamic reticular nucleus. Synaptic activation of interneurons was elicited by stimulating the optic tract using a bipolar electrode (FHC Inc., ME, USA) with a single voltage pulse or a train of pulses (200 μs, up to 12 V, 100 Hz) at an intensity of about twice the response threshold, unless otherwise stated. In some experiments, thalamic interneurons were activated directly by placing the stimulating electrode in their dendritic field while excitatory synaptic transmission was blocked by 2,3-dioxo-6-nitro-1,2,3,4-tetrahydrobenzo(f)quinoxaline-7-sulphonamide (NBQX, 5 μm) and d,l-2-amino-5-phosphonopentanoic acid (d,l-AP5, 100 μm). Activating interneurons directly could evoke an inhibitory postsynaptic potential (IPSP) in proximally (≈200 μm) and distally (≈400 μm) located thalamocortical cells. Comparing the IPSPs recorded simultaneously in thalamocortical cell pairs allowed us to study the relative contribution of interneuron-mediated short- and long-range inhibition in thalamocortical cells (Zhu & Heggelund, 2001). Synaptic responses were averaged over 10-50 trials, and the peak responses were used to calculate the ratios of IPSPs. To examine the effect of exogenous GABA on thalamocortical cells, we added GABA (200 μm) to the bath using drop application (20-60 μl). GABA was typically delivered twice (5-10 min between applications) both before and after the various antagonists (10 or 20 μm picrotoxin (PTX), 1 or 2 mm saclofen or 1 mm CGP 35348) were added to the bath through the perfusion system. The half-time for the bath solution exchange was 6-10 s. A period of 7-10 min was usually allowed for wash-in and washout of the antagonists. The tests were performed at a holding membrane potential of −58 ± 3 mV. All results are reported as means ± s.e.m. Statistical difference between groups was determined using ANOVA unless stated otherwise. The level of significance was set at P < 0.05.

To reveal cell morphology, biocytin (0.25 %) was included in the intracellular solution. After recordings, slices were fixed by immersion in 0.1 m phosphate buffer containing 4 % paraformaldehyde, and histologically reacted for biocytin to recover the cell morphology. Cells were subsequently drawn under a ×100 objective with the aid of a computerized reconstruction system (Neurolucida, MicroBrightField, USA) or a camera lucida system. The extent of dendritic and axonal fields was quantified by measuring the major radius of the fields projected on a 2-D plane. The complexity of the branching pattern of fully recovered dendrites was quantified by counting the number of branches at each branch order. Branch order was evaluated according to the centrifugal method. With this method all dendritic segments attached to soma are given the 1st order. Then, after each new bifurcation, the branch order is incremented by one and the two daughter branches are given the same order. Chemicals were purchased from Sigma-RBI.

Results

Identification of geniculate interneurons at different developmental stages

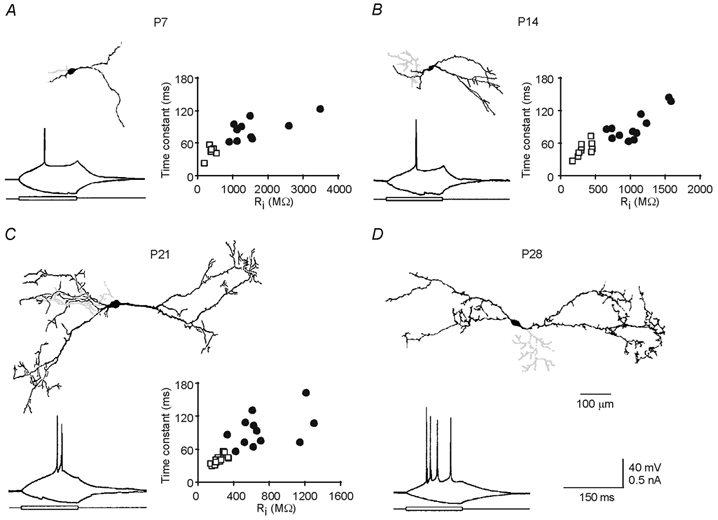

We recorded from interneurons in the dLGN of the rat thalamus at different developmental stages (Fig. 1). Once the whole-cell configuration was formed, geniculate interneurons were distinguished from thalamocortical cells by their physiological properties, such as high input resistance and long membrane time constant (Fig. 1A-C, plots; not shown for > P28 cells, but see Zhu et al. 1999; Zhu & Heggelund, 2001). The morphology was recovered for 11 interneurons (Fig. 1A) and 9 thalamocortical cells from P7 slices, 12 interneurons (Fig. 1B) and 13 thalamocortical cells from P14 slices, 12 interneurons (Fig. 1C) and 22 thalamocortical cells from P21 slices, and 24 interneurons from P28 (Fig. 1D) and P35 slices. The characteristic dendritic and axonal branching patterns that distinguish interneurons from thalamocortical cells in older animals (Zhu et al. 1999; Zhu & Heggelund, 2001) were also found in the young age groups.

Figure 1. Geniculate interneurons at different developmental stages.

A-D, morphology of reconstructed P7 (A), P14 (B), P21 (C) and P28 (D) geniculate interneurons. Note the axons in light grey. Recording traces show responses of four interneurons at different developmental stages to depolarizing and hyperpolarizing current pulses. Scale bars in D apply to A-D. Plots in A-C show membrane properties of interneurons (IN; •) and thalamocortical cells (TC; □). Note that the time constant was higher for interneurons than for thalamocortical cells (IN: 83 ± 6 ms, n = 11; TC: 43 ± 5 ms, n = 6; Student's t test, P < 0.001 for P7; IN: 91 ± 8 ms, n = 12; TC: 46 ± 4 ms, n = 11; t test, P < 0.0001 for P14; IN: 94 ± 9 ms, n = 12; TC: 40 ± 2 ms, n = 24; t test, P < 0.0001 for P21) as was the input resistance (Ri; IN: 1552 ± 240 MΩ, n = 11; TC: 389 ± 47 MΩ, n = 6; t test, P < 0.005 for P7; IN: 1055 ± 86 MΩ, n = 12; TC: 325 ± 32 MΩ, n = 11; t test, P < 0.0001 for P14; IN: 725 ± 92 MΩ, n = 12; TC: 257 ± 13 MΩ, n = 24; t test, P < 0.0001 for P21).

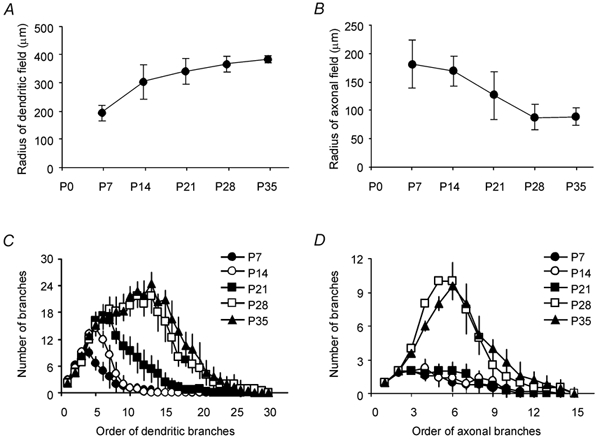

Extent of dendritic and axonal trees and passive membrane properties of interneurons

The dendrites of thalamic inhibitory interneurons expanded rapidly during early development, approaching their adult length by the end of the fourth postnatal week (Fig. 2A), reminiscent of the expansion of the dendrites of cortical excitatory neurons (Zhu, 2000). The magnitude of this expansion, as estimated from the radius of the 2-D dendritic field, was ≈100 %. This reflects a genuine expansion of the dendrites within the dLGN because the width of the nucleus increased by only ≈30 % during the same period. The dendritic tree also became increasingly complex with more branches (Fig. 2C). This elaboration of the dendritic tree was relatively slow in the first three postnatal weeks. After the third postnatal week, however, there was a remarkable increase in the number of high-order (> 10th order), short dendritic branches or appendages, presumed to be presynaptic dendritic terminals (Ralston, 1971; Rapisardi & Miles, 1984; Hamos et al. 1985). In contrast to the dendritic tree, the extent of the axon did not change significantly during development (Fig. 2B). The branching of the axon was slow in the first three postnatal weeks but fast in the fourth week (Fig. 2D). The dendritic and axonal properties were not significantly different between P28 and P35 interneurons.

Figure 2. Morphological properties of geniculate interneurons at different developmental stages.

A, major radius of dendritic field (P7: 191 ± 31 μm, n = 10; P14: 300 ± 64 μm, n = 8; P21: 339 ± 50 μm, n = 10; P28: 365 ± 26 μm, n = 5; P35: 383 ± 10 μm, n = 5; P < 0.05 between these five groups, P = 0.53 between groups P28 and P35). B, major radius of axonal field (P7: 181 ± 43 μm, n = 8; P14: 169 ± 26 μm, n = 7; P21: 125 ± 43 μm, n = 7; P28: 88 ± 22 μm, n = 4; P35: 88 ± 15 μm, n = 5; P = 0.25 between these five groups). C, plot of number of dendritic branches versus order of dendritic branch. D, plot of number of axonal branches versus order of axonal branch.

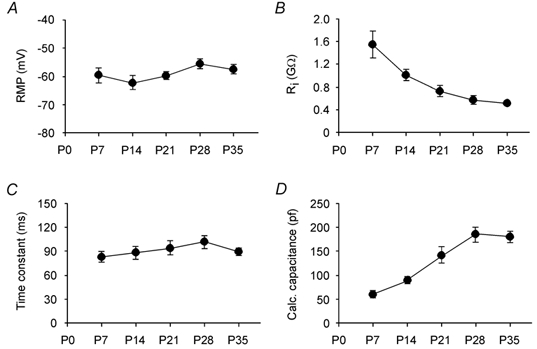

The resting membrane potential of the interneurons remained constant from P7 to P35 (Fig. 3A) while the input resistance decreased gradually to ≈550 MΩ, i.e. about one-third of that in P7 cells (Fig. 3B). There was no significant change in the time constant of interneurons during development (Fig. 3C). Consistent with the lack of parallel changes of input resistance and membrane time constant, we calculated an ≈300 % increase in membrane capacitance of interneurons during development (Fig. 3D). Together with our morphological data these results suggest that the decrease in input resistance is due mainly to the increase in membrane area.

Figure 3. Passive membrane properties of geniculate interneurons at different developmental stages.

A, resting membrane potential (RMP; P7: −59.6 ± 2.4 mV, n = 11; P14: −63.0 ± 2.5 mV, n = 12; P21: −59.7 ± 1.4 mV, n = 12; P28: −55.6 ± 1.6 mV, n = 9; P35: −57.6 ± 1.6 mV, n = 16; ANOVA, P = 0.13 between these five groups). B, input resistance (P7: 1552 ± 240 MΩ, n = 11; P14: 1055 ± 86 MΩ, n = 12; P21: 725 ± 92 MΩ, n = 12; P28: 568 ± 68 MΩ, n = 8; P35: 508 ± 29 MΩ, n = 16; P < 0.0001 between these five groups, P = 0.18 between groups P28 and P35). C, time constant (P7: 83 ± 6 ms, n = 11; P14: 91 ± 8 ms, n = 12; P21: 94 ± 9 ms, n = 12; P28: 102 ± 8 ms, n = 8; P35: 85 ± 4 ms, n = 16; P = 0.76 between these five groups). D, calculated capacitance (P7: 60 ± 5 pF, n = 11; P14: 88 ± 6 pF, n = 12; P21: 114 ± 17 pF, n = 12; P28: 187 ± 16 pF, n = 8; P35: 182 ± 9 pF, n = 16; P < 0.0001 between these five groups, P = 0.79 between groups P28 and P35).

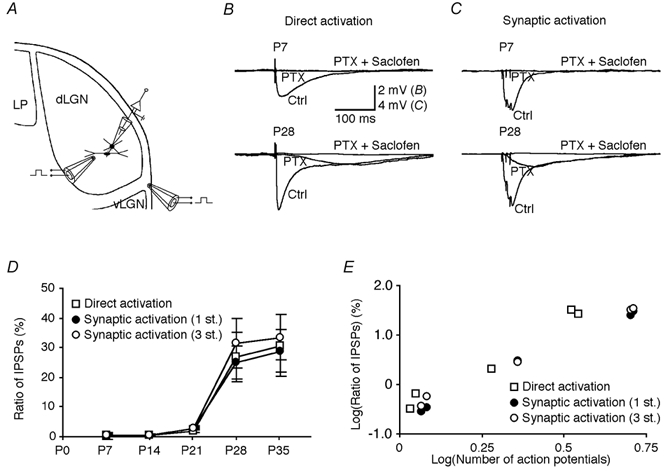

Interneuron-mediated GABAA and GABAB inhibition

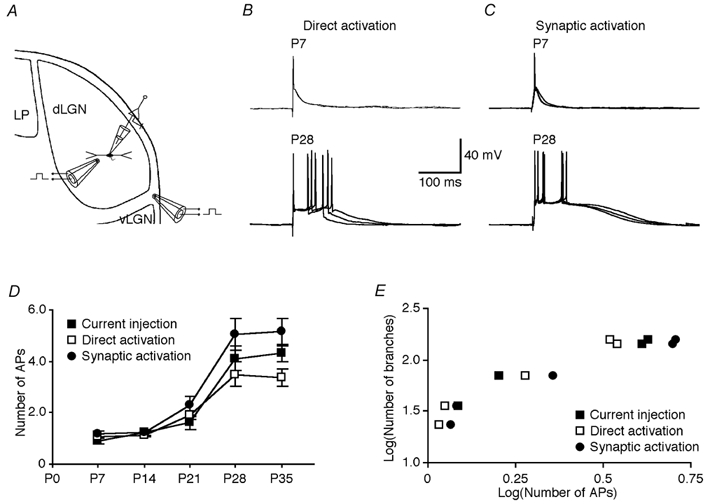

Development of GABA inhibition was studied by direct or synaptic activation of interneurons (Fig. 4A). Recordings from thalamocortical cells showed that direct activation of interneurons evoked an IPSP in both P7 and P28 thalamocortical cells (Fig. 4B). The IPSP had a single component in P7 thalamocortical cells and two components in P28 thalamocortical cells. The IPSP in P7 thalamocortical cells and the early part of the response in P28 thalamocortical cells were blocked by PTX, a GABAA receptor blocker (Fig. 4B). The residual, slow IPSP in P28 thalamocortical cells was blocked by saclofen (Fig. 4B). Unlike GABAA inhibition, GABAB inhibition developed slowly. The developmental time course, as estimated by the ratio GABAB/GABAA (Fig. 4D), indicates that by the end of the third week, the GABAB inhibition was still very weak compared to GABAA inhibition, but that in the following week, it increased rapidly.

Figure 4. Maturation of interneuron-mediated GABAA and GABAB inhibition in dLGN.

A, schematic drawing of a thalamocortical neuron recorded in dLGN and the direct stimulating electrode within dLGN and the synaptic stimulating electrode in the optic tract (between dLGN and ventral LGN, vLGN). LP, lateral posterior nucleus. B, direct electric shock within the dLGN evoked an IPSP in a P7 and a P28 thalamocortical cell in the presence of 5 μm NBQX and 100 μmd,l-AP5. Bath application of 10 μm PTX completely blocked the IPSP in the P7 thalamocortical cell, but only the early component of the IPSP in the P28 thalamocortical cell. The later component of the IPSP in the P28 thalamocortical cell was blocked by adding 1 mm saclofen. C, a train of three electric shocks in the optic tract evoked an IPSP in a P7 and a P28 thalamocortical cell. Bath application of 10 μm PTX completely blocked the IPSP in the P7 thalamocortical cell, but only the early component of the IPSP in the P28 thalamocortical cell. The later component of the IPSP in the P28 thalamocortical cell was blocked by adding 1 mm saclofen. Note that thalamocortical cells were held at about 0 mV when IPSPs were examined. Scale bars in B apply to both B and C. D, the ratio of GABAB/GABAA IPSPs recorded from thalamocortical cells at different developmental stages (P7: 0.3 ± 1.1 %, n = 6; P14: 0.7 ± 0.5 %, n = 6; P21: 2.1 ± 0.6 %, n = 6; P28: 26.9 ± 8.3 %, n = 5; P35: 30.6 ± 10.5 %, n = 6; P < 0.001 between these five groups, P = 0.79 between groups P28 and P35, for direct activation; P7: 0.3 ± 0.2 %, n = 6; P14: 0.4 ± 0.1 %, n = 6; P21: 3.0 ± 0.7 %, n = 6; P28: 24.9 ± 5.5 %, n = 5; P35: 28.7 ± 7.0 %, n = 5; P < 0.0001 between these five groups, P = 0.67 between groups P28 and P35, for single synaptic shock (1 st.); P7: 0.4 ± 0.4 %, n = 6; P14: 0.6 ± 0.4 %, n = 6; P21: 2.8 ± 0.6 %, n = 6; P28: 31.4 ± 8.5 %, n = 5; P35: 33.4 ± 7.7 %, n = 5; P < 0.0001 between these five groups, P = 0.87 between groups P28 and P35, for a train of three synaptic shocks (3 st.)). E, plots of ratio of GABAB and GABAA responses in thalamocortical cells induced by direct (P < 0.01) or synaptic (P < 0.005) activation of interneurons versus the number of action potentials evoked by these stimuli at different developmental stages reveal their significant correlations.

It cannot be excluded that terminals from the thalamic reticular nucleus were activated by the intranuclear stimulation. Therefore we also induced IPSPs in thalamocortical cells by stimulation of the optic tract with a single electric shock or a train of three shocks (Fig. 4C). The absence of the reticular nucleus in our preparation (see Methods) ensured that this procedure would not lead to activation of reticular axons. The developmental time course of the GABA inhibitions observed with optic tract stimulation was similar to that obtained by direct activation (Fig. 4D), showing that the changes were predominantly related to inhibition through geniculate interneurons (cf. Zhu & Heggelund, 2001; see also Ahlsén et al. 1984; Paré et al. 1991; Curró Dossi et al. 1992).

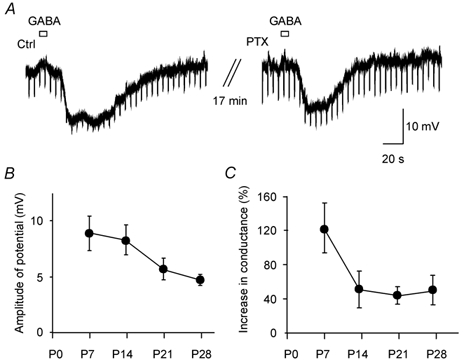

To test whether the slow maturation of the synaptic GABAB inhibition could be explained by low GABAB receptor expression, we examined the effect of exogenous GABA (200 μm) on thalamocortical cells at different developmental stages (Fig. 5). Brief GABA applications induced a prominent response in thalamocortical cells at all developmental stages. This is exemplified in Fig. 5A for a P14 thalamocortical cell. The GABA response was only partially blocked by PTX and the residual hyperpolarization was blocked by saclofen or CGP 35348 (n = 3, data not shown). The average peak amplitude of the GABAB receptor-mediated potentials was not significantly different between the age groups (Fig. 5B). Likewise, the relative increase in conductance produced by GABA applications in the presence of PTX (Fig. 5C) was similar throughout development. These results suggest that the slow maturation of the interneuron-mediated GABAB response is unlikely to be due to a lower expression level of GABAB receptors at early developmental ages.

Figure 5. Exogenous GABA elicits GABAB inhibition in dLGN at early developmental stages.

A, a brief bath application of GABA (200 μm, 40 μl) evoked an inhibitory response in a P14 thalamocortical cell held at −59 mV. This inhibitory response was only partially blocked by the bath application of PTX (20 μm). Note the increase in input resistance after blockade of the GABAA response by PTX. The resting membrane potential of this cell was −66 mV. B, average peak amplitude of GABAB responses of thalamocortical cells induced by the brief bath application of GABA in the presence of PTX at different developmental stages (P7: 9.0 ± 1.5 mV, n = 10; P14: 8.4 ± 1.3 mV, n = 6; P21: 5.7 ± 1.6 mV, n = 6; P28: 4.9 ± 0.4 mV, n = 3; P = 0.21 between these four groups). C, relative increase in conductance produced by the GABA applications in the presence of PTX (ratio of conductancepeak GABA response/conductancebefore GABA response) at different developmental stages (P7: 123 ± 29 %, n = 7; P14: 51 ± 21 %, n = 6; P21: 44 ± 10 %, n = 6; P28: 50 ± 17 %, n = 3; P > 0.05 between these age groups).

Burst firing in interneurons and GABAB inhibition

Previous studies have suggested that GABAB inhibition of postsynaptic cells may be dependent on burst firing in presynaptic cells (Huguenard & Prince 1994; Destexhe & Sejnowski, 1995; Kim et al. 1997; Zhu & Heggelund, 2001). To analyse the relationship between presynaptic burst firing and postsynaptic GABAB inhibition, we first determined the postnatal development of burst firing in the interneurons, and then compared this pattern with the appearance of GABAB inhibition of thalamocortical cells.

At the resting membrane potential, a short depolarizing pulse typically evoked a single action potential at threshold in P7 and P14 interneurons but occasionally a doublet was seen (Fig. 1 and Fig. 6D). The same depolarizing pulse usually evoked in an all-or-none fashion a doublet of action potentials in P21 interneurons or a burst of 3-7 action potentials in P28/35 interneurons (Fig. 1 and Fig. 6D). The average firing frequency for the first two action potentials in the doublet or burst was around 35 Hz for ‘young’ interneurons (P14: 33 Hz, n = 2; P21: 39 ± 9 Hz, n = 5), which is within the low range of the intraburst firing frequency found for ‘older’ interneurons (Zhu et al. 1999). The generation of doublets of action potentials in young interneurons relied at least in part on a low threshold calcium spike like the bursts of action potentials in adult interneurons (Zhu et al. 1999). This was shown by the fact that blocking the fast spikes in P7 and P14 interneurons with the Na+ channel blocker TTX (2 μm) revealed a slow depolarizing hump that grew in amplitude with increasing depolarizing current injection and disappeared when 200 μm Ni+ was included in the bath solution (n = 6, data not shown). A preceding hyperpolarization (membrane potential of −75 ± 5 mV) did not alter the probability of evoking a burst, but as in adult animals (Zhu et al. 1999), the hyperpolarization could increase the strength of the burst. This was first detected at P21 where there was a weak increase in the number of spikes in the burst (from 1.6 ± 0.4 to 2.5 ± 0.3 spikes, n = 10, P = 0.03) and in the intraburst frequency (from 39 ± 9 to 82 ± 17 Hz, n = 5, P = 0.07).

Figure 6. Burst firing of geniculate interneurons at different developmental stages.

A, schematic drawing of interneurons recorded in the dLGN and activated by either direct stimulation within the dLGN or synaptic stimulation of the optic tract. B, direct electric shock within the dLGN evoked single action potentials in a P7 interneuron but bursts of action potentials in a P28 interneuron in the presence of 5 μm NBQX and 100 μmd,l-AP5. The membrane potential of both cells was −59 mV. C, electric shock of the optic tract evoked single action potentials in a P7 interneuron but bursts of action potentials in a P28 interneuron. Scale bars in B apply to both B and C. D, number of action potentials of interneurons at different developmental stages in response to a threshold depolarizing current injection (see Fig. 1; P7: 0.9 ± 0.1, n = 7; P14: 1.2 ± 0.1, n = 10; P21: 1.6 ± 0.4, n = 10; P28: 4.1 ± 0.5, n = 9; P35: 4.3 ± 0.3, n = 16; P < 0.0001 between these five groups, P = 0.72 between groups P28 and P35), or to direct (P7: 1.1 ± 0.1, n = 6; P14: 1.1 ± 0.1, n = 6; P21: 1.9 ± 0.2, n = 6; P28: 3.5 ± 0.5, n = 6; P35: 3.4 ± 0.3, n = 7; P < 0.0001 between these five groups, P = 0.82 between groups P28 and P35) or synaptic (P7: 1.2 ± 0.1, n = 6; P14: 1.2 ± 0.1, n = 6; P21: 2.3 ± 0.3, n = 6; P28: 5.1 ± 0.6, n = 5; P35: 5.2 ± 0.5, n = 5; P < 0.0001 between these five groups, P = 0.90 between groups P28 and P35) activation. E, plots of total number of dendritic branches of interneurons versus the number of action potentials evoked by current injection (P < 0.001), or direct (P < 0.01) or synaptic activation (P < 0.005) at different developmental stages reveal their significant correlations.

We also examined the developmental changes of the burst responses evoked synaptically. We found that the pattern of responses of interneurons activated either directly (Fig. 6B; see Methods) or synaptically (Fig. 6C) was similar to that with current injection at all developmental stages (Fig. 6D). Altogether, the results suggest that after the fourth postnatal week the intrinsic properties of interneurons have reached a mature stage, which allows them to support robust bursts of action potentials similar to those characterized in adult animals in a previous study (Zhu et al. 1999). Consistent with the hypothesis that burst firing is related to dendritic specializations (Zhu & Heggelund, 2001), there was a good correlation between the interneurons’ ability to provide burst firing during development and the total number of dendritic branches of interneurons (Fig. 6E; r > 0.80). Interestingly, GABAB inhibition of thalamocortical cells was correlated to both the total number of dendritic branches in interneurons (r > 0.97, P < 0.001; data not shown) and the burst firing capability of the interneurons (Fig. 4E; r > 0.96, P < 0.001).

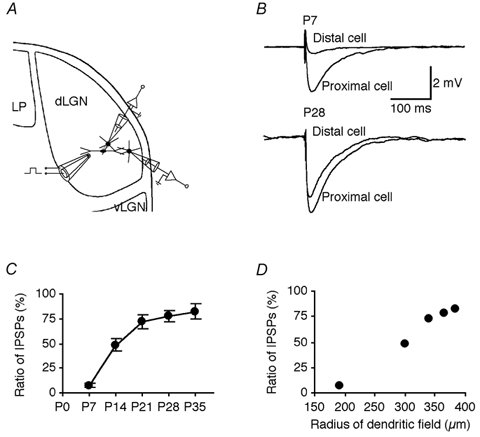

Dendritic field and long-range GABAA inhibition

Because GABA release from distal dendrites of interneurons may be involved in long-range GABAA inhibition of thalamocortical cells (Zhu & Heggelund, 2001), we reasoned that the postnatal expansion of the dendritic tree should have a profound effect on the range of GABAA inhibition. Using direct activation of interneurons, we thus examined how the range of GABAA inhibition of thalamocortical cells developed. To isolate the GABAA inhibition NBQX, d,l-AP5 and saclofen, a GABAB receptor blocker, were included in the bath solution (Fig. 7A; cf. Zhu & Heggelund, 2001). The isolated GABAA inhibition was recorded from pairs of thalamocortical cells with one cell located at ≈200 μm (average radius of the dendritic field of P7 interneurons) and the other at ≈400 μm (average radius of the dendritic field of P28/35 interneurons) away from the stimulating electrode. In P7 slices, the direct activation of interneurons induced a prominent IPSP in the proximally located thalamocortical cell, but a much smaller IPSP in the distally located thalamocortical cell recorded simultaneously. In contrast, in P28 slices, the IPSP recorded from the proximally located thalamocortical cell was only slightly larger than that recorded simultaneously from the distally located cell (Fig. 7B). The inhibition evoked in the distally located cell increased over the first four postnatal weeks, with a particularly rapid increase over the first three weeks (Fig. 7C). The development of long-range GABAA inhibition of thalamocortical cells correlated well (r = 0.84) with the expansion of the dendritic field (Fig. 7D). This is consistent with the view that GABA release from the dendrites of interneurons contributes to the long-range inhibition of thalamocortical cells (Zhu & Heggelund, 2001). A significant contribution to this development from axons of the interneurons is unlikely. The complexity of the axonal arbor changed during development, but the time course of this change was different from that of the long-range GABAA inhibition. While the complexity of the axonal arbor changed very little during the first three weeks (Fig. 2D), the range of the GABAA inhibition increased rapidly. After this period, the axonal arbor showed a sudden increase in complexity while the range of the GABAA inhibition showed only a minor increase. Furthermore, in contrast to the dendrites the axons did not seem to expand during development (Fig. 2B).

Figure 7. Range of GABAA inhibition at different developmental stages.

A, schematic drawing of recording and stimulating electrodes indicating the location of the stimulating electrode and the locations of a simultaneously recorded pair of thalamocortical cells. B, direct electric shock elicited a large IPSP in the proximal thalamocortical cell and a small IPSP in the distal cell recorded from P7 and P28 LGN slices in the presence of 5 μm NBQX, 100 μmd,l-AP5 and 1 mm saclofen. C, the ratio of GABAAdist/GABAAprox IPSPs recorded from distal and proximal thalamocortical cells at different developmental stages (P7: 7.4 ± 2.2 %, n = 7; P14: 48.4 ± 6.2 %, n = 7; P21: 72.1 ± 7.4 %, n = 7; P28: 77.4 ± 5.5 %, n = 6; P35: 82.2 ± 8.0 %, n = 5; P < 0.0001 between these five groups, P = 0.62 between groups P28 and P35). D, plot of ratio of GABAA responses recorded from distal and proximal thalamocortical cells versus the major radius of dendritic field of interneurons at different developmental stages reveals their significant correlation (P < 0.0005).

Effects from residual axon terminals of reticular cells may also be of little relevance for the increase in range of the GABAA inhibition since GABAA IPSPs of similar amplitudes in proximal and distal thalamocortical cells have also been reported in 36- to 72-h-old organotypic culture slices, i.e. sufficiently old to ensure complete degeneration of reticular axons (Zhu & Heggelund, 2001). Finally, one last factor to consider as a possible contributor to the increase in the range of GABAA inhibition is a growth of the dendrites of thalamocortical cells into the dendrites of the interneurons. To check this possibility we measured the length of the major radius of the dendritic field of thalamocortical cells at the different age groups in the same way as we measured the dendrites of the interneurons. The results showed a significant expansion of the dendritic field over the first three postnatal weeks (P7: 121 ± 10 μm, n = 9; P14: 141 ± 10 μm, n = 13; P21: 180 ± 8 μm, n = 22; P28: 156 ± 10 μm, n = 7; P35: 157 ± 11 μm, n = 9; P < 0.05 between P7 and P35), consistent with previous findings for thalamocortical cells in the ventral posterior nucleus of the developing mouse (Warren & Jones, 1997). This expansion, however, was comparable to the developmental enlargement of the dLGN, and most probably too small to account for the increased distance in the nucleus over which the GABAA inhibition could be elicited. In agreement with this, we found that the correlation between the development of the dendrites of thalamocortical cells and long-range GABAA inhibition was not significant (P > 0.05). A minor role for the extension of the dendrites of thalamocortical cells in the development of the long-range GABAA inhibition is also consistent with an earlier electron microscopy study that showed that the synapses with the interneurons are primarily located on the proximal rather than the distal dendrites of the thalamocortical cells (Wilson et al. 1992).

Discussion

During the first postnatal month, there were prominent changes in the pattern of inhibition of thalamocortical cells that were correlated to morphological and physiological changes of the interneurons. The marked increase in the range of GABAA-mediated inhibition of thalamocortical cells occurred in parallel with the expansion of the dendritic field of the interneurons over the first three postnatal weeks. In the fourth postnatal week, pronounced GABAB inhibition was observed. At the same time burst firing in the interneurons appeared, and a dramatic increase in the complexity of the dendritic branching pattern of the interneurons was seen. Thus, the development of the long-range GABAA inhibition and the GABAB inhibition of postsynaptic thalamocortical cells were associated with dendritic maturation of presynaptic interneurons. It is not known whether the spatially restricted GABAA inhibition in the young animals corresponds to the long-range inhibition in adult animals, or whether it is an immature form of inhibition that later differentiates into the mature short- and long-range GABAA inhibition.

Postsynaptic vs. presynaptic mechanisms for maturation of feedforward inhibition in dLGN

The postnatal increase of GABAB response in inhibitory transmission in the hippocampus (Gaiarsa et al. 1995; Nurse & Lacaille, 1999), cortex (Fukuda et al. 1993) and dLGN (this study) parallels the postnatal increase of AMPA response in excitatory transmission in the hippocampus (Liao et al. 1995; Durand et al. 1996; Zhu & Malinow, 2002), cortex (Kim et al. 1995; Isaac et al. 1997), and LGN (Chen & Regehr, 2000). However, there are notable differences in the development of these two synaptic transmission systems. For example, while glutamatergic synapses mature rather quickly, most of them acquire AMPA receptors during the first postnatal week (Durand et al. 1996; Isaac et al. 1997; Zhu & Malinow, 2002), GABAergic synapses develop rather slowly and little GABAB inhibition can be detected in the first two postnatal weeks (this study; see also Fukuda et al. 1993; Gaiarsa et al. 1995; Nurse & Lacaille, 1999).

The mechanisms that regulate maturation of glutamatergic and GABAergic synapses may also differ considerably. While the maturation of glutamatergic synapses seems to be controlled by regulated postsynaptic delivery of AMPA receptors (Isaac et al. 1997; Liao et al. 1999; Zhu et al. 2000), the mechanisms underlying the maturation of GABAergic synaptic transmission remain ambiguous. One possibility is that regulated delivery of GABAB receptors postsynaptically could play a key role in determining the time course of the maturation of the inhibitory transmission. The GABAB receptor expression in the thalamus is, however, already maximal by the end of the second postnatal week (Turgeon & Albin, 1994), when only a small GABAB response could be elicited synaptically (Fig. 4). It could be that the GABAB receptors that are expressed early in the development are located mainly at presynaptic rather than postsynaptic sites (Fritschy et al. 1999). This is unlikely because a prominent GABAB response could be elicited by bath application of GABA already in P7 thalamocortical cells (Fig. 5). The fact that a GABAB response could be elicited by the exogenous GABA but not synaptically might suggest that the postsynaptic GABAB receptors are initially inserted into the plasma membrane at non-synaptic sites, and later translocated to synaptic sites to become functional (cf. Chen et al. 2000; Passafaro et al. 2001). While experimental support for a contribution from any mechanisms (pre- or postsynaptic) was still lacking, we decided to examine the maturation of inhibitory interneurons and GABAergic transmission in the dLGN. Although available techniques do not allow us to directly manipulate neuronal growth to determine the exact contribution of all presynaptic and/or postsynaptic factors, our study shows that postnatal dendritic maturation of interneurons should be included as an important contributor to the development of GABAergic transmission in the dLGN. Specifically, we found that the increase in long-range GABAA inhibition correlated well with the expansion of the dendritic tree of the interneurons. Moreover, we found that GABAB inhibition correlated well with the interneuron's ability to generate burst firing which, in turn, correlated well with the total number of branches in their dendritic trees (Fig. 6). Burst firing in interneurons may depend critically on active conductances in their distal dendrites (Zhu & Heggelund, 2001). Thus we speculate that the slow development of burst firing results from the slow addition of distal dendritic branches in interneurons (where more active conductances may be inserted) and that this contributes to the slow maturation of GABAB inhibition in thalamocortical cells.

Thalamic reticular cells can provide thalamocortical cells with GABAA and GABAB inhibition (Soltesz & Crunelli, 1992; Huguenard & Prince, 1994; Kim et al. 1997). Previous evidence suggests that the characteristics of the reticular cell-mediated GABAA and GABAB inhibition evolve along independent paths (Warren et al. 1997) and the dendritic tree of these cells changes substantially during postnatal development (Warren & Jones, 1997). In order to assess the direct (Soltesz & Crunelli, 1992; Huguenard & Prince, 1994; Kim et al. 1997) and indirect (Steriade et al. 1985; Liu et al. 1995; Zhu & Lo, 1999) contributions of the reticular cells to the development of GABAergic signalling in thalamocortical cells, it would be necessary to examine how maturation of the reticular cells relates to the developmental time course of feedback inhibition.

Functional considerations

Early studies in the LGN have shown that the inhibition induced by visual or optic tract stimuli is weak and short-lasting in neonatal thalamocortical cells (Berardi & Morrone, 1984; Shatz & Kirkwood, 1984), and the inhibitory surround in the receptive field of cells in young animals is significantly weaker than that of adult cells (Tootle & Friedlander, 1986). These observations can be explained by our finding that during early development interneurons provide thalamocortical cells with only spatially restricted GABAA inhibition. This weak, short-lasting inhibition may be functionally well adapted to the immature, weak excitatory inputs from the retina (Berardi & Morrone, 1984; Chen & Regehr, 2000). In addition, the absence of GABAB inhibition, which is powerful in suppressing excitation (Connors et al. 1988), may contribute to the overall excitability in young thalamocortical cells. This may be crucial for synaptic plasticity and functional circuitry reorganization during early development (Liao et al. 1995; Wu et al. 1996; Chen & Regehr, 2000).

Interneurons in many regions of the adult brain can produce various forms of inhibition, which appear to be important for the brain to properly perform different tasks (e.g. Moore & Nelson, 1998; Reyes et al. 1998; Xiang et al. 1998; Finnerty et al. 1999; Zhu & Connors, 1999; Porter et al. 2001; Larkum & Zhu, 2002). Likewise, adult geniculate interneurons can also provide thalamocortical cells with multiple forms of inhibition, including short-range GABAA inhibition, long-range GABAA inhibition and long-duration GABAB inhibition (Ahlsén et al. 1984; Curró Dossi et al. 1992; Zhu & Heggelund, 2001), and these different forms of inhibition can be dynamically regulated by neuromodulators (Cox et al. 1998; Cox & Sherman, 2000; Zhu & Heggelund, 2001). The slow emergence of the various forms of inhibition in the dLGN suggests that only adult interneurons may provide the variety of inhibitory patterns needed for adequate, dynamic adaptation to the requirements of signal processing in different behavioural states (Ahlsén et al. 1984; Curró Dossi et al. 1992; Hartveit et al. 1993; Hartveit & Heggelund, 1995; Uhlrich et al. 1995; Fjeld et al. 2002). For example, the slow-wave sleep that is associated with burst firing in thalamocortical cells (Steriade et al. 1997) has a developmental time course in the rat (Jouvet-Mournier et al. 1970) similar to that found in this study for burst firing in the interneurons, emerging at P14 and reaching an adult proportion after the fourth postnatal week.

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs Bert Sakmann and Roberto Malinow for their support and Drs Josh Huang, Fu-Sun Lo, Morten Raastad and Ken Seidenman for their helpful discussions and comments. This work was supported in part by the NIH (R. Malinow), the Alexander von Humboldt Foundation, the Alzheimer's Association, the Fraxa Research Foundation, the Max-Planck Society and the Norwegian Research Council. J.J.Z. is a Naples Investigator of the NARSAD Foundation.

References

- Ahlsén G, Lindström S, Lo F-S. Inhibition from the brain stem of inhibitory interneurones of the cat's dorsal lateral geniculate nucleus. J Physiol. 1984;347:593–609. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1984.sp015085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berardi N, Morrone MC. Development of γ-aminobutyric acid mediated inhibition of X cells of the cat lateral geniculate nucleus. J Physiol. 1984;357:525–537. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1984.sp015515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen C, Regehr WG. Developmental remodeling of the retinogeniculate synapse. Neuron. 2000;28:955–966. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)00166-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen L, Chetkovich DM, Petralia RS, Sweeney NT, Kawasaki Y, Wenthold RJ, Bredt DS, Nicoll RA. Stargazing regulates synaptic targeting of AMPA receptors by two distinct mechanisms. Nature. 2000;408:936–943. doi: 10.1038/35050030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Connors BW, Malenka RC, Silva LR. Two inhibitory postsynaptic potentials, and GABAA and GABAB receptor-mediated responses in neocortex of rat and cat. J Physiol. 1988;406:443–468. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1988.sp017390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox CL, Sherman SM. Control of dendritic outputs of inhibitory interneurons in the lateral geniculate nucleus. Neuron. 2000;27:597–610. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)00069-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox CL, Zhou Q, Sherman SM. Glutamine locally activates dendritic outputs of thalamic interneurons. Nature. 1998;394:478–482. doi: 10.1038/28855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curró Dossi R, Paré D, Steriade M. Various types of inhibitory postsynaptic potentials in anterior thalamic cells are differentially altered by stimulation of laterodorsal tegmental cholinergic nucleus. Neurosci. 1992;47:279–289. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(92)90244-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Destexhe A, Sejnowski TJ. G protein activation of kinetics and spillover of γ-aminobutyric acid may account for differences between inhibitory responses in the hippocampus and thalamus. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:9515–9519. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.21.9515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durand GM, Kovalchuk Y, Konnerth A. Long-term potentiation and functional synapse induction in developing hippocampus. Nature. 1996;381:71–75. doi: 10.1038/381071a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eysel UT, Pape H-C, Van Schayck R. Excitatory and differential disinhibitory actions of acetylcholine in the lateral geniculate nucleus of the cat. J Physiol. 1986;370:233–254. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1986.sp015932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finnerty GT, Roberts LS, Connors BW. Sensory experience modifies the short-term dynamics of neocortical synapses. Nature. 1999;400:367–371. doi: 10.1038/22553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fjeld IT, Ruksenas O, Heggelund P. Brainstem modulation of visual response properties of single cells in the dorsal lateral geniculate nucleus of cat. J Physiol. 2002;543:541–554. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2002.021204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fritschy JM, Meskenaite V, Weinmann O, Honer M, Benke D, Mohler H. GABAB-receptor splice variants GB1a and GB1b in rat brain: developmental regulation, cellular distribution and extrasynaptic localization. Eur J Neurosci. 1999;11:761–768. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.1999.00481.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukuda A, Mody I, Prince DA. Differential ontogenesis of presynaptic and postsynaptic GABAB inhibition in rat somatosensory cortex. J Neurophysiol. 1993;70:448–452. doi: 10.1152/jn.1993.70.1.448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaiarsa JL, Tseeb V, Ben-Ari Y. Postnatal development of pre- and postsynaptic GABAB -mediated inhibitions in the CA3 hippocampal region of the rat. J Neurophysiol. 1995;73:246–255. doi: 10.1152/jn.1995.73.1.246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamos JE, Van Horn SC, Raczkowski D, Uhlrich DJ, Sherman SM. Synaptic connectivity of a local circuit neurone in lateral geniculate nucleus of the cat. Nature. 1985;317:618–621. doi: 10.1038/317618a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartveit E, Heggelund P. Brainstem modulation of signal transmission through the cat dorsal lateral geniculate nucleus. Exp Brain Res. 1995;103:372–384. doi: 10.1007/BF00241496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartveit E, Ramberg SI, Heggelund P. Brain stem modulation of spatial receptive field properties of single cells in the dorsal lateral geniculate nucleus of the cat. J Neurophysiol. 1993;70:1644–1655. doi: 10.1152/jn.1993.70.4.1644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huguenard JR, Prince DA. Clonazepam suppresses GABAB-mediated inhibition in thalamic relay neurons through effects in nucleus reticularis. J Neurophysiol. 1994;71:2576–2581. doi: 10.1152/jn.1994.71.6.2576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Isaac JT, Crair MC, Nicoll RA, Malenka RC. Silent synapses during development of thalamocortical inputs. Neuron. 1997;18:269–280. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80267-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jouvet-Mournier D, Astic L, Lacote D. Ontogenesis of the states of sleep in rat, cat, and guinea pig during the first postnatal month. Dev Psychobiol. 1970;2:216–239. doi: 10.1002/dev.420020407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim HG, Fox K, Connors BW. Properties of excitatory synaptic events in neurons of primary somatosensory cortex of neonatal rats. Cereb Cortex. 1995;5:148–157. doi: 10.1093/cercor/5.2.148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim U, Sanchez-Vives MV, McCormick DA. Functional dynamics of GABAergic inhibition in the thalamus. Science. 1997;278:130–134. doi: 10.1126/science.278.5335.130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larkum ME, Zhu JJ. Signaling of layer 1 and whisker-evoked Ca2+ and Na+ action potentials in distal and terminal dendrites of rat neocortical pyramidal neurons in vitro and in vivo. J Neurosci. 2002;22:6991–7005. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-16-06991.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liao D, Hessler NA, Malinow R. Activation of postsynaptically silent synapses during pairing induced LTP in CA1 region of hippocampal slice. Nature. 1995;375:400–404. doi: 10.1038/375400a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liao D, Zhang X, O'Brien R, Ehlers MD, Huganir RL. Regulation of morphological postsynaptic silent synapses in developing hippocampal neurons. Nat Neurosci. 1999;2:37–43. doi: 10.1038/4540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu XB, Warren RA, Jones EG. Synaptic distribution of afferents from reticular nucleus in ventroposterior nucleus of cat thalamus. J Comp Neurol. 1995;352:187–202. doi: 10.1002/cne.903520203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore CI, Nelson SB. Spatio-temporal subthreshold receptive fields in the vibrissa representation of rat primary somatosensory cortex. J Neurophysiol. 1998;80:2882–2892. doi: 10.1152/jn.1998.80.6.2882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nurse S, Lacaille JC. Late maturation of GABAB synaptic transmission in area CA1 of the rat hippocampus. Neuropharmacol. 1999;38:1733–1742. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3908(99)00122-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paré D, Curró Dossi R, Steriade M. Three types of inhibitory postsynaptic potentials generated by interneurons in the anterior thalamic complex of cat. J Neurophysiol. 1991;66:1190–1204. doi: 10.1152/jn.1991.66.4.1190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Passafaro M, Piëch V, Sheng M. Subunit-specific temporal and spatial patterns of AMPA receptor exocytosis in hippocampal neurons. Nat Neurosci. 2001;4:917–926. doi: 10.1038/nn0901-917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porter JT, Johnson CK, Agmon A. Diverse types of interneurons generate thalamus-evoked feedforward inhibition in the mouse barrel cortex. J Neurosci. 2001;21:2699–2710. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-08-02699.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ralston HJ., III Evidence for presynaptic dendrites and a proposal for their mechanism of action. Nature. 1971;230:585–588. doi: 10.1038/230585a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rapisardi SC, Miles TP. Synaptology of retinal terminals in the dorsal lateral geniculate nucleus of the cat. J Comp Neurol. 1984;223:515–534. doi: 10.1002/cne.902230405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reyes A, Lujan R, Rozov A, Burnashev N, Somogyi P, Sakmann B. Target-cell-specific facilitation and depression in neocortical circuits. Nat Neurosci. 1998;1:279–285. doi: 10.1038/1092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shatz CJ, Kirkwood PA. Prenatal development of functional connections in the cat's retinogeniculate pathway. J Neurosci. 1984;4:1378–1397. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.04-05-01378.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soltesz I, Crunelli V. GABAA and pre- and post-synaptic GABAB receptor-mediated responses in the lateral geniculate nucleus. Prog Brain Res. 1992;90:151–169. doi: 10.1016/s0079-6123(08)63613-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steriade M, Deschenes M, Domich L, Mulle C. Abolition of spindle oscillations in thalamic neurons disconnected from nucleus reticularis thalami. J Neurophysiol. 1985;54:1473–1497. doi: 10.1152/jn.1985.54.6.1473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steriade M, Jones EG, McCormick DA. Thalamus. Amsterdam: Elsevier Science; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Tootle JS, Friedlander MJ. Postnatal development of receptive field surround inhibition in kitten dorsal lateral geniculate nucleus. J Neurophysiol. 1986;56:523–541. doi: 10.1152/jn.1986.56.2.523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turgeon SM, Albin RL. Postnatal ontogeny of GABAB binding in rat brain. Neurosci. 1994;62:601–613. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(94)90392-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uhlrich DJ, Tamamaki N, Murphy PC, Sherman SM. Effects of brain stem parabrachial activation on receptive field properties of cells in the cat's lateral geniculate nucleus. J Neurophysiol. 1995;73:2428–2447. doi: 10.1152/jn.1995.73.6.2428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warren RA, Golshani P, Jones EG. GABAB-receptor-mediated inhibition in developing mouse ventral posterior thalamic nucleus. J Neurophysiol. 1997;78:550–553. doi: 10.1152/jn.1997.78.1.550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warren RA, Jones EG. Maturation of neuronal form and function in a mouse thalamo-cortical circuit. J Neurosci. 1997;417:277–295. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-01-00277.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson JR, Friedlander MJ, Sherman SM. Fine structural morphology of identified X- and Y-cells in the cat's lateral geniculate nucleus. Proc Roy Soc Lond. 1992;221:411–436. doi: 10.1098/rspb.1984.0042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu G, Malinow R, Cline HT. Maturation of a central glutamatergic synapse. Science. 1996;274:972–976. doi: 10.1126/science.274.5289.972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiang Z, Huguenard JR, Prince DA. Cholinergic switching within neocortical inhibitory networks. Science. 1998;281:985–988. doi: 10.1126/science.281.5379.985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu JJ. Maturation of layer 5 neocortical pyramidal neurons: amplifying salient layer 1 and layer 4 inputs by Ca2+ action potentials in adult rat tuft dendrites. J Physiol. 2000;526:571–587. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2000.00571.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu JJ, Connors BW. Intrinsic firing patterns and whisker-evoked synaptic responses of neurons in the rat barrel cortex. J Neurophysiol. 1999;81:1171–1183. doi: 10.1152/jn.1999.81.3.1171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu JJ, Esteban JA, Hayashi Y, Malinow R. Postnatal synaptic potentiation: delivery of GluR4-containing AMPA receptors by spontaneous activity. Nat Neurosci. 2000;3:1098–1106. doi: 10.1038/80614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu JJ, Heggelund P. Muscarinic regulation of dendritic and axonal outputs of rat thalamic interneurons: A new cellular mechanism for uncoupling distal dendrites. J Neurosci. 2001;21:1148–1159. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-04-01148.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu JJ, Lo F-S. Three GABA receptor-mediated postsynaptic potentials in interneurons in the rat lateral geniculate nucleus. J Neurosci. 1999;19:5721–5730. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-14-05721.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu JJ, Lytton WW, Xue J-T, Uhlrich DJ. An intrinsic oscillation in interneurons of the rat lateral geniculate nucleus. J Neurophysiol. 1999;81:702–711. doi: 10.1152/jn.1999.81.2.702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu JJ, Malinow R. Acute versus chronic NMDA receptor blockade and synaptic AMPA receptor delivery. Nat Neurosci. 2002;3:513–514. doi: 10.1038/nn0602-850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]