Abstract

To determine whether autaptic inhibition plays a functional role in the adult hippocampus, the action potential afterhyperpolarisations (spike AHPs) of CA1 interneurones were investigated in 25 basket, three bistratified and eight axo-axonic cells. The spike AHPs showed two minima in all regular-spiking (5), burst-firing (3) and in many fast-spiking cells (17:28). The fast component had a time-to-peak (TTP) of 1.2 ± 0.5 ms, the slower TTP was very variable (range of 3.3–103 ms). The AHP width at half-amplitude (HW) was 12.5 ± 5.7 ms in fast-spiking, 29.3 ± 18 ms in regular-spiking and 99.7 ± 42 ms in burst-firing cells. Axo-axonic cells never establish autapses, and the fast-spiking variety showed narrow (HW: 3.9 ± 0.7 ms) spike AHPs with only one AHP minimum (TTP: 0.9 ± 0.1 ms). When challenged with GABAA receptor modulators, spike AHPs in basket and bistratified cells were enhanced by zolpidem (HW by 18.4 ± 6.2 % in 10:15 cells tested), diazepam (45.2 ± 0.5 %, 6:7), etomidate (43.9 ± 36 %, 6:8) and pentobarbitone sodium (41 %, 1:1), and were depressed by bicuculline (-41 ± 5.7 %, 5:8) and picrotoxin (-54 %, 1:1), and the enhancement produced by zolpidem was reduced by flumazenil (-31 ± 13 %, relative to the AHP HW during exposure to zolpidem, 3:4). Neuronal excitability was modulated in parallel. The spike AHPs of three axo-axonic cells tested showed no sensitivity to etomidate, pentobarbitone or diazepam. Interneurone-to-interneurone inhibitory postsynaptic potentials (IPSPs), studied with dual intracellular recordings, had time courses resembling those of the spike AHPs. The IPSP HW was 13.4 ± 2.8 ms in fast-spiking (n = 16) and 28.7 ± 5.8 ms in regular-spiking/burst-firing cells (n = 6), and the benzodiazepine1-selective modulator zolpidem strongly enhanced these IPSPs (45 ± 28 %, n = 5). Interneurones with spike AHPs affected by the GABAA receptor ligands exhibited 3.8 ± 1.9 close autaptic appositions. In three basket cells studied at the ultrastructural level 6 of 6, 1 of 2 and 1 of 2 close appositions were confirmed as autapses. Therefore, in the hippocampus autaptic connections contribute to spike AHPs in many interneurones. These autapses influence neuronal firing and responses to GABAA receptor ligands.

Autapses are synapses that an axon establishes with its own somato-dendritic domain (van der Loos & Glaser, 1972). Autapses have been reported within the vertebrate central nervous system (CNS) at the light microscopic (van der Loos & Glaser, 1972; Karabelas & Purpura, 1980; Park et al. 1980; Peters & Proskauer, 1980; Takagi et al. 1984) and ultrastructural level (Franck et al. 1995; Lübke et al. 1996; Thomson et al. 1996; Cobb et al. 1997; Tamás et al. 1997). However, while there is anatomical proof for massive autaptic self-innervation of neocortical GABAergic interneurones (Thomson et al. 1996; Tamás et al. 1997), in the hippocampus autapses were only confirmed on one basket cell (Cobb et al. 1997). In low-density cell cultures, autapses are readily formed, presumably because suitable postsynaptic targets are scarce (Bekkers & Stevens, 1991). In the vertebrate CNS it has been suggested that autapses are present during early postnatal stages of brain development, but are absorbed during development (Lübke et al. 1996), and the physiological significance of autapses in situ has often been thought to be negligible. Autapses do not, however, appear simply to be misguided synapses since axo-axonic cells in the adult rat lack autaptic contacts (Somogyi et al. 1982; Freund et al. 1983), whereas other interneurones clearly establish them (Thomson et al. 1996; Cobb et al. 1997; Tamás et al. 1997).

Modulation of the action potential afterhyperpolarisation (spike AHP) is accompanied by an alteration of neuronal discharge (Erisir et al. 1999), and it has been suggested that autaptic innervation might modulate neuronal intrinsic excitability (e.g. Tamás et al. 1997). While autapses of single cell cultures are frequently used to study synaptic transmission (Bekkers & Stevens, 1991; Chen & van den Pol, 1996; Mennerick et al. 1998), in the intact neuronal networks in vertebrate CNS, physiological evidence for autaptic self-innervation of GABAergic neurones is currently restricted to two studies. Using anaesthetised rats, Park et al. (1980) concluded that autaptic feedback of medium spiny neurones in the neostriatum led to the reduction of EPSPs generated in the identical neurones by stimulation of the substantia nigra. Applying the patch clamp technique in rat cerebellar slices, Pouzat & Marty (1998) reported bicuculline-sensitive currents activated by brief depolarisations indicative of autaptic connections in 20 % of the of the inhibitory interneurones studied.

In previous studies we found that the spike AHPs of hippocampal fast-spiking interneurones show a considerable variability in their shape (Ali et al. 1999; Pawelzik et al. 1999; Thomson et al. 2000). Based on the anatomical evidence of interneurone autapses in the neocortex (Thomson et al. 1996; Tamás et al. 1997) and the hippocampus (Cobb et al. 1997), in this study we asked whether the variability of the spike AHPs might have been caused by autapses and whether autaptic inhibition might play a functional role in the adult hippocampus, and investigated the spike AHPs of hippocampal interneurones challenged with GABAA receptor modulators. Preliminary results of this study have been published in abstract form (Pawelzik et al. 2000).

Methods

Tissue preparation for electrophysiological recordings and pharmacology

Young adult male rats (Sprague-Dawley, body weight 120 g to 180 g) were deeply anaesthetised with fluothane (inhalation) and pentobarbitone sodium (Sagatal, 60 mg kg−1, intraperitoneal injection, Rhône Mérieux Ltd, Harlow, UK) and perfused transcardially with an ice-cold modified artificial cerebrospinal fluid (ACSF) in which NaCl was replaced with 248 mm sucrose (with 60 mg l−1 Sagatal), equilibriated with 95 % O2-5 % CO2; the animals were then decapitated (procedures were approved by the British Home Office with regard to the UK Animals (Scientific Procedures) Act, 1986). Coronal brain slices, 450 µm thick, were cut with a vibroslice (Campden Instruments Ltd, Loughborough, UK) in ice-cold modified ACSF, then transferred to the interface recording chamber. Slices in the chamber were maintained (at 34–36 °C) for 1 h in the modified ACSF solution, then for another hour in normal ACSF (mm: 124 NaCl, 25.5 NaHCO3, 3.3 KCl, 1.2 KH2PO4, 1 MgSO4, 2.5 CaCl2, and 15 d-glucose, equilibrated with 95 % O2-5 % CO2) prior to commencing recording. The tested drugs, i.e. bicuculline methochloride (10–20 µm, Tocris Cookson Ltd, Bristol, UK), diazepam (1–2 µm, first dissolved in absolute alcohol resulting in a final alcohol concentration of 5 mm, RBI, Poole, UK), etomidate (0.5–2 µm, Janssen Pharmaceutica, South Africa), flumazenil (4 µm, Roche, Welwyn Garden City, UK.), pentobarbitone sodium (250 µm, Rhône Mérieux Ltd), picrotoxin (1–20 µm, Sigma, St Louis, USA) and zolpidem (0.2–0.4 µm, first dissolved in absolute alcohol resulting in a final alcohol concentration of 10–20 mm, RBI), were applied via the bathing medium.

Paired intracellular recordings

Dual intracellular recordings from interneurones with their somata in stratum pyramidale (SP) of CA1 were made with conventional glass microelectrodes, filled with 2 % biocytin (Sigma) (w/v) in 2 m KMeSO4 (Pfaltz and Bauer, Birkenhead, UK, resistance of 80–200 MΩ) under current clamp (Axoprobe, Axon Instruments, Foster City, USA). During recordings, inhibitory interneurones were recognised by their discharge characteristics and/or by their ability to activate short and constant latency inhibitory postsynaptic potentials in simultaneously recorded postsynaptic neurones. Current-voltage characteristics of the interneurones, obtained from their responses to 400 ms current pulses, were recorded with pCLAMP software (Axon Instruments). Suprathreshold current injection (100–360 ms, 0.3 Hz) was used to control the discharge of the presynaptic interneurone and single-axon IPSPs were recorded in the postsynaptic neurones. Small hyperpolarising test pulses (0.05 to 0.3 nA, 10–20 ms duration) were injected into the postsynaptic cell 50 ms before the onset of the presynaptic depolarising current pulse to monitor electrode balance and stability of postsynaptic membrane properties. Continuous recordings from the pre- and postsynaptic neurone were stored on analog tape (Store 4DS, Racal, Southampton, UK) and digitised off-line for analysis using in-house software. Individual neurones were recorded for up to 3.5 h. In some cases cells were actively filled with biocytin by current injection for up to 15 min (pulse width 0.5 s; amplitude +0.5 nA; frequency 1 Hz). In others adequate filling occurred by diffusion of biocytin from the electrode.

Data analysis

Single sweeps were inspected and those containing large spontaneous postsynaptic potentials or artifacts were rejected. Trigger points for the subsequent averaging (10–50 sweeps for AHPs, 50–200 sweeps for IPSPs) were set to the middle of the rising phase of each (presynaptic) action potential. For the analysis of the spike AHPs, single sweeps, in which a just supra-threshold current pulse elicited an action potential at a given interval following the start of the pulse were selected. Even if several spikes were elicited during the injection of a current pulse, the effects of GABAA receptor modulators were analysed on spike AHPs of the first spike to minimise the effect of short-term plasticity of the autaptic IPSP.

The AHP amplitude was measured as the difference between the spike threshold and voltage minimum following the action potential. The AHP width was measured as the width at half of the AHP amplitude. The time-to-peak of the first and second AHP minima were measured with respect to the action potential peak.

The statistical analysis was performed using Microsoft Excel and GraphPad InStat. Values are given as mean ± s.d. (standard deviation).

Tissue processing for light- and electron microscopy

After recording, slices were fixed overnight in one of two fixative solutions made up in 0.1 m phosphate buffer (PB, pH 7.4): (1) 4 % paraformaldehyde, 0.2 % picric acid and 0.025 % glutaraldehyde or (2) 4 % paraformaldehyde and 0.2 % picric acid. Slices were re-sectioned on a vibratome (Vibratome 1000) to 60 µm thickness, cryoprotected in sucrose-glycerol solutions, then freeze-thawed above liquid nitrogen. Thereafter sections were processed to reveal the biocytin-labelled profiles with a permanent peroxidase reaction product. Sections were incubated overnight in ABC-peroxidase (Vector Laboratories, Peterborough, UK) and either processed to reveal peroxidase labelling with nickel-intensified DAB (diaminobenzidine)subsequently, or incubated for another 1 and 16 h in biotinylated goat anti-Avidin D (1:10000, Vector Laboratories), followed by 1 h in ABC peroxidase, to amplify the peroxidase labelling prior to DAB development. Peroxidase labelling was developed with nickel-intensified DAB as the chromagen and the tissue was processed for resin embedding (Hughes et al. 2000).

Drawing tube reconstruction of biocytin-filled interneurones and ultrastructural analysis

The morphology of the recorded neurones was reconstructed using a ×100 oil immersion objective lens and drawing tube. For ultrastructural analysis, ultrathin sections (silver inference colour) were cut in series on a Leica Ultracut S ultramicrotome (Leica Microsystems, Milton Keynes, UK) using a diamond knife (Diatome, Leica Microsystems), collected on Pioloform-coated copper slot grids, counterstained with Reynold's lead (ii) citrate and 4 % uranyl acetate, then examined on a Philips CM120 transmission electron microscope (Philips, Best, The Netherlands).

Results

Time courses of spike AHPs

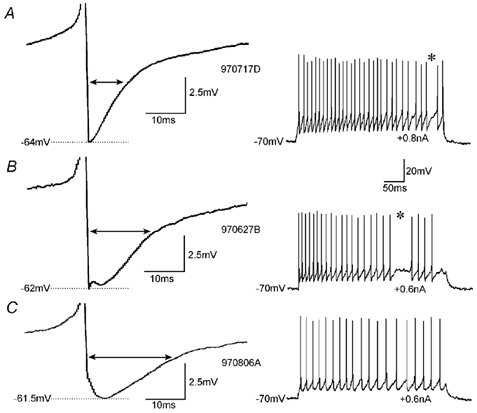

Hippocampal fast-spiking interneurones typically show rapid-onset, deep spike AHPs (Fig. 1). In some cells the AHP decayed rapidly and almost monophasically (Fig. 1A), while the decay in others was more complex and often triphasic in appearance (Fig. 1B and C). In fast-spiking hippocampal interneurones, voltage-gated delayed rectifier K+ channels (probably assembled from Kv3.1 and Kv3.2 subunits) are the main channels contributing to the action potential repolarisation and the early phase of the afterhyperpolarisation (Martina et al. 1998). They are probably largely responsible for the first minimum of the spike AHP with a time-to-peak (TTP1) of 1.1 ± 0.4 ms (n = 20, Table 1). The second minimum is probably, as shown for fast-spiking SO (stratum oriens) interneurones (Zhang & McBain, 1995), partially generated by small conductance Ca2+-dependent K+ currents (via SK channels). The TTP of the second minimum (TTP2, 4.2 ± 0.6 ms, n = 14), however, coincides with the TTP of interneurone-to-interneurone IPSPs generated in fast-spiking cells (Table 2, Fig. 2, see below). The timing of the minimum at TTP2 therefore indicates that it might originate, at least in part, from an inhibitory potential which an interneurone generates in its own somato-dendritic membrane. Interestingly, fast-spiking axo-axonic cells, which never establish autapses (Somogyi et al. 1982; Freund et al. 1983), had spike AHPs with fast TTPs (0.9 ± 0.1, n = 6) similar to those of fast-spiking basket cells, but never showed a second minimum (Fig. 5). Therefore the AHP width at half-amplitude (HW) was much briefer in fast-spiking axo-axonic cells (3.9 ± 0.7 ms, n = 6) than in fast-spiking basket and bistratified cells (12.4 ± 5.7 ms, n = 23).

Figure 1. Variability of spike AHPs in fast-spiking basket cells.

The shape of the AHPs (left panel) in individual cells varied from triangular (A) via tri-phasic (B) to rounded (C). In these examples spiking was elicited with current injections of 0.6, 0.2 and 0.3 nA, and AHPs following the first, second and second spike, respectively, were averaged. However, for the analysis of drug effects (e.g. Figs 2-5) only spike AHPs following the first spike were analysed. The double arrows indicate the AHP width at half-amplitude. The resting membrane potential in all three cells was −70 mV. The action potentials are truncated. The right panel shows examples of the discharge pattern of the individual neurones. *A prominent feature in many fast-spiking cells is the interrupted discharge in the gamma frequency range (A and B).

Table 1.

Spike AHP properties and their alteration by GABAA receptor modulators

| AHP properties | Changes in AHP half-width (%) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Axon | No. cl-ap | Firing pattern | TTP1 (ms) | TTP2 (ms) | HW (ms) | Ampl (mV) | Zolp | DZP | Flum | Etom | PB | Bicuc | Picro | |

| 980513b | bi | 2 | fs | 1.1 | 3.7 | 19.1 | 7.1 | — | — | — | — | 41 | — | — |

| 970625b | ba | 5 | fs | 1.5 | 5.2 | 22 | 7.6 | — | 10 | — | — | — | — | — |

| 970627b | ba | 2 | fs | 1.7 | 4.3 | 14.7 | 8.9 | — | 25 | — | — | — | −54 | — |

| 980219g | ba | 6 | fs | 1 | 3.5 | 12.5 | 11.6 | 11 | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| 980603a | ba | 2 | fs | 1.6 | n.d. | 6 | 11.5 | 13 | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| 981202b | ba | 4 | fs | n.d. | 4 | 13.2 | 6.7 | 18 | — | — | 40 | — | — | — |

| 980109a/b | ba | 3 | fs | 0.9 | 4.7 | 15.4 | 9.3 | 19 | 0 | — | — | — | — | — |

| 980318d1 | ba | 1 | fs | 1 | 4.6 | 10 | 25 | 10 | 20 | — | — | — | — | — |

| 980330f1 | ba | 4 | fs | 2 | n.d. | 11 | 15.25 | 23 | 28 | — | — | — | — | — |

| 990208a1 | ba | 3 | fs | 0.8 | 4.4 | 16 | 13.6 | 21 | — | −33 | — | — | — | — |

| 990222a | ba | 6 | fs | 1.1 | 3.3 | 14.7 | 10.5 | 20 | — | −17 | — | — | — | — |

| 990615c | ba | 6 | fs | 0.8 | 4.3 | 16.2 | 6.7 | 18 | — | −43 | — | — | — | — |

| 000724bb | ba | 4 | fs | 1.7 | 3.9 | 13.1 | 14.4 | — | — | — | — | — | −15 | — |

| 000727a | ba | 4 | fs | 1.6 | 3.5 | 18 | 18.5 | — | — | — | 63 | — | −56 | — |

| 980818b3 | ba | ? | rs | 0.8 | 8 | 15.6 | 12.8 | 0 | 146 | — | — | — | — | — |

| 980819c1 | ba | 1 | rs | 1.2 | 5 | 15.2 | 19.4 | 31 | 42 | — | 7 | — | — | −54 |

| 000317c | ba | 3 | rs | 1.5 | 7.9 | 19.1 | 6.4 | — | — | — | 19 | — | −12 | — |

| 000707d | ba | 5 | rs | 1.8 | 16.2 | 40.9 | 7.2 | — | — | — | 110 | — | −68 | — |

| 000717g | bi | 3 | bf | 2 | 56 | 75 | 4.1 | — | — | — | 12 | — | — | — |

| 000724c | ba | 8 | bf | 2.3 | 103 | 148 | 2.8 | — | — | — | 56* | — | — | — |

| Mean | All | 3.8** | — | — | — | — | 16.7 | 39 | −31 | 43.9 | — | −41 | — | |

| s.d. | 1.9 | — | — | — | — | 8 | 49 | 13 | 36 | — | 25.7 | — | ||

| Mean | fs | 1.3* | 4.1 | 14.4* | 11.9 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | ||

| s.d. | 0.4 | 0.6 | 4.0 | 5.2 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | |||

| Mean | rs | 1.3 | 9.3 | 22.7 | 11.5 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | ||

| s.d. | 0.4 | 4.8 | 12.3 | 6.0 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | |||

| 990625b | ba | 2 | fs | n.d. | 4.2 | 21 | 12.1 | x | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| 980617a | ba | ? | fs | 0.9 | n.d. | 8.4 | 11.1 | x | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| 971126b1 | ba | 1 | fs | 0.8 | n.d. | 3.9 | 9.4 | x | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| 990806b | bi | 2 | fs | n.d. | 4.7 | 19.1 | 11.8 | — | — | — | x | — | — | — |

| 990217b4 | ba | 3 | fs | 1.6 | n.d. | 10 | 12.2 | x | — | x | — | — | — | — |

| 970618b1 | ba | ? | fs | 0.6 | n.d. | 10 | 29 | — | — | — | — | — | x | — |

| 970618b1 | ba | ? | fs | 0.4 | n.d. | 4.2 | 14 | — | — | — | — | — | x | — |

| 970618c2 | ba | 3 | fs | 0.5 | n.d. | 2.9 | 20 | — | — | — | — | — | x | — |

| 000717b | a–a | 0 | fs | 0.9 | n.d. | 5.6 | 19.5 | — | — | — | x | — | — | — |

| 970911c | a–a | 0 | rs | 1.2 | 14.6 | 55.6 | 6.6 | — | — | — | — | x | — | — |

| 970806c | a–a | 0 | bf | 1.1 | 40.3 | 76 | 4 | — | x | — | — | — | — | — |

| Mean | All | 1.4** | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | |

| s.d. | 1.3 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | ||

| Mean | fs | 0.8* | 15.9 | 9.5* | 15.5 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | ||

| s.d. | 0.4 | 16.9 | 6.7 | 6.3 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | |||

The modulation of spike AHPs was analysed in fast-spiking (fs), regular-spiking (rs) and burst-firing (bf) interneurones, which comprised basket cells (ba), bistratified cells (bi) and axo-axonic cells (a–a). In the cells where only one clear spike AHP minimum was detectable, depending on its time-to-peak it was classified as TTP1 or TTP2, while the other component was declared ‘not detectable’= n.d. The upper part of the table lists cells whose AHPs were modulated by the GABAA receptor modulators zolpidem (Zolp), diazepam (DZP,), flumazenil (Flum), etomidate (Etom), pentobarbitone (PB), bicuculline (Bicuc) and picrotoxin (Picro). The numbers of cells tested, with spike AHPs indicative of autaptic feedback, was sufficiently large for zolpidem (P < 0.01), diazepam (P < 0.05), etomidate (P < 0.01) and bicuculline (P < 0.05) to result in statistically significant changes of the IPSP HWs (Wilcoxon signed-rank test). In the cells listed in the lower part, the drug applications (x) did not change the spike AHPs. Where several drugs were tested in one cell, those listed on the left were applied first and those to the right were added later. Each drug was applied for at least 30 min. For the assessment of the effect of the first drug any change in the width at half-amplitude (HW) of the spike AHP is expressed as a percentage of the HW under control conditions. The first drug applied was not washed off before another was added. Changes in the spike AHP associated with a second drug are therefore expressed as a percentage change relative to the spike AHP HW measured at the end of the first drug application. In the cell where the AHP is marked with an asterisk, the spike AHP amplitude was used to assess the drug effect. Where a question mark (?) is given for the number of close autaptic appositions (No. cl-ap), their number could not be determined. This was either due to very weak labelling, or because a dense tangle of axons, originating from several interneurones, precluded the unequivocal identification of autaptic close appositions. Abbreviations: Ampl = amplitude, TTP = time-to-peak. Asterisks indicate which properties of the cells with and without pharmacological evidence of autapses showed statistically significant differences:

P < 0.05

P < 0.01, Mann-Whitney U test.

Table 2.

Properties of interneurone-to-interneurone IPSPs

| IPSP | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre- and post-synaptic cell | No.cl-ap | TTP (ms) | RT (ms) | HW (ms) | Ampl (mV) | MP (mV) | Erev (mV) | |

| 971126a1/a3 | ba → ba | ? | 2.7 | 1.1 | 8.5 | –1.9 | –55 | –68 |

| 971210c | ba → ba | ? | 5.8 | 3.4 | 12.4 | –0.34 | –59 | — |

| 980219g† | ba → ba | 6 | 3.5 | 1.4 | 13.8 | –0.68 | –54 | — |

| 980428d | ba → ba | 10 | 2.9 | 2.8 | 14.8 | –1.71 | –57 | — |

| 981211b† | ba → ba | 6 | 3.5 | 2.4 | 11.4 | –1.49 | –60 | — |

| 970709d | ba → bi | 4 | 4.4 | 2.6 | 18.8 | –0.60 | –65 | — |

| 971210a | ba → bi | 8 | 4.1 | 1.2 | 18.0 | –0.88 | –56 | — |

| 980213a | ba → bi | ? | 2.4 | 1.4 | 8.8 | –2.54 | –56 | –70 |

| 980219b | ba → bi | ? | 3.8 | 1.4 | 11.8 | –1.73 | –67 | –76 |

| 980219c | bi → ba | ? | 4.1 | 2.4 | 11.6 | –0.98 | –57 | — |

| 990806d | bi → ba | 1 | 2.9 | 3.6 | 16.4 | –0.37 | –60 | — |

| Mean ±s.d. | fs → fs | 3.6 ± 1.0 | 2.2 ± 0.9 | 13.3 ± 3.4 | –1.2 ± 0.7 | –58.7 ± 4.1 | –71.3 ± 4.2 | |

| 980624d† | (rs) ba → ba | ? | 4.6 | 2.4 | 14.8 | –4.18 | –61 | — |

| 981202c | (bf) ba → ba | ? | 2.8 | 1.3 | 13.6 | –1.05 | –57 | — |

| 980227a1 | (rs) ba → ba | 6 | 4.6 | 3.9 | 12.9 | –1.56 | –55 | — |

| 980408d† | (bf) ba → bi | 3 | 2.9 | 1.4 | 14.0 | –0.75 | –64 | — |

| 980219 | (rs) bi → ba | ? | 4.0 | 2.6 | 13.2 | –1.19 | –58 | — |

| Mean ±s.d. | rs + bf → fs | 3.8 ± 0.9 | 2.3 ± 1.1 | 13.7 ± 0.7 | –1.7 ± 1.4 | –59.0 ± 3.5 | ||

| Mean ±s.d. | fs + rs + bf → fs | 3.7 ± 0.9* | 2.2 ± 0.9 | 13.4 ± 2.8** | –1.4 ± 1.0 | 58.8 ± 3.8 | ||

| 980205d | ba → ba (bf) | ? | 6.9 | 3.2 | 25.2 | –0.78 | –59 | –72 |

| 980624c | ba → ba (bf) | 4 | 6.7 | 2.8 | 29.6 | –1.06 | –61 | — |

| 981202d | ba → ba (bf) | 3 | 6.5 | 3.4 | 34.4 | –0.48 | –58 | — |

| 990217b1† | ba → ba (rs) | ? | 8.0 | 2.6 | 28.0 | –1.40 | –70 | — |

| 980330f1 | ba → ba (rs) | ? | 5.2 | 1.6 | 19.6 | –1.00 | –63 | — |

| 980408c | bi → ba (bf) | 3 | 2.8 | 1.4 | 35.2 | –0.26 | –64 | — |

| Mean ±s.d. | fs → rs + bf | 5.8 ± 2.9* | 2.5 ± 0.8 | 28.7 ± 5.8** | –0.8 ± 0.4 | –62.5 ± 4.3 | ||

| Mean ±s.d. | All | 4.9 ± 2.6 | — | — | — | — | — | –71.5 ± 3.4 |

The IPSP time-to-peak (TTP) and width at half-amplitude (HW) were significantly longer in postsynaptic regular-spiking (rs) and burst-firing (bf) cells than in fast-spiking interneurones (which are the cells where the firing pattern is not explicitly stated in parenthesis). The statistical differences of these IPSP properties in the two cell populations are indicated by asterisks:

P < 0.05

P < 0.0001, Mann-Whitney U test.

Abbreviations: Ampl = amplitude, ba = basket cell, bi = bistratified cell, Erev = reversal potential, MP = membrane potential, No. cl-ap = number of close synaptic appositions, RT = 10–90 % rise time.

Cells in which the IPSPs were tested with zolpidem.

Figure 2. Modulation of spike AHPs and IPSPs by zolpidem.

A, the spike AHP of a fast-spiking presynaptic basket cell was increased by 0.2 µm zolpidem (average from 15–30 min of drug application). The traces indicated by Δ show the difference between control and drug application traces. The IPSPs generated by this basket cell in another postsynaptic fast-spiking basket cell were increased in parallel (B). As autaptic IPSPs superimpose on spike AHPs, they will be distorted by the rapid membrane potential changes associated with the AHP. These difference traces do not therefore indicate the shape or time course of the event that would have been recorded in isolation. For the anatomy of the pre- and postsynaptic cell see Fig. 6.

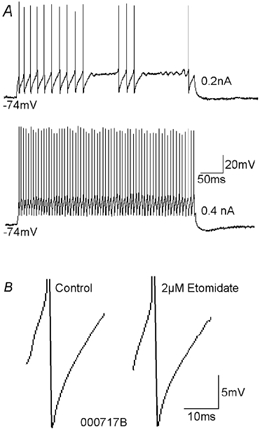

Figure 5. The spike AHP of a fast-spiking axo-axonic cell was not enhanced by etomidate.

A, current injection of intermediate intensities (e.g. 0.2 nA) into the axo-axonic cell elicited interrupted fast-spiking discharge. Injection of higher current intensities (e.g. 0.4 nA) elicited uninterrupted spiking. B, spike AHPs of fast-spiking axo-axonic cells were monophasic and very brief. This spike AHP was not affected by etomidate.

In regular-spiking cells, the TTP1 (1.3 ± 0.4 ms, n = 5) was similar to that of fast-spiking cells. The TTP2 was, however, much longer (range 5.0–16.2 ms). Spike AHPs in burst-firing cells could only be assessed in three interneurones due to the dominating depolarising wave underlying the burst (Table 1), and because it was difficult to elicit single spike responses to current injection in burst-firing cells.

The TTP1 (1.8 ± 0.6 ms) and TTP2 (range 40.3–103 ms) of the spike AHP were longer in these cells than in fast-spiking and regular-spiking cells (Table 1).

Modulation of spike AHPs by GABAA receptor modulators

To determine whether autapses might contribute to the variability of the spike AHPs in hippocampal interneurones, spike AHPs were challenged with GABAA receptor modulators. The modulators were applied during recordings from 25 basket cells, three bistratified cells and three axo-axonic cells (Table 1). The tested drugs were: (1) the positive modulators diazepam (1–2 µm, n = 8), etomidate (2 µm, n = 9; experiment 981202B, 0.5 µm), pentobarbitone sodium (250 µm, n = 2) and zolpidem (0.2–0.4 µm, n = 15), (2) the benzodiazepine site antagonist flumazenil (4 µm, n = 4) and (3) the GABAA receptor antagonists bicuculline (10–20 µm, n = 8) and picrotoxin (20 µm, n = 1).

Although these modulators had effects on the amplitudes of spike AHPs in many cases, the point in time at which the maximum effect occurred was variable. Changes in the AHP width at half-amplitude were therefore used as the more reliable estimate of an effect of each of these modulators.

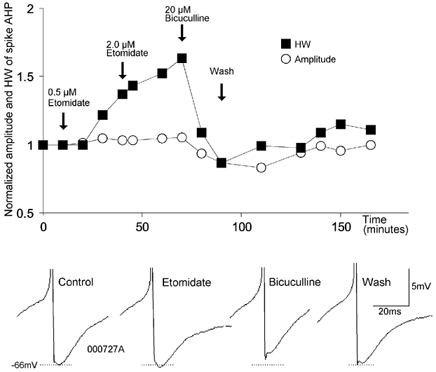

Within the population of fast-spiking cells, spike AHPs of 13 of 20 basket cells (Fig. 2–4) and Fig. 1 of 2 bistratified cells were modulated by the drugs, positive GABAA receptor modulators increasing and the negative modulator and receptor antagonists decreasing the HW (Table 1). GABAA receptor blockers converted the triphasic (Fig. 1B) or rounded (Fig. 1C) spike AHPs into a more monophasic event (Fig. 4). Bicuculline did not, as might have been expected, completely block the event that gave rise to TTP2. However, it might have revealed an AHP component previously masked by the autaptic IPSPs. In hippocampal fast-spiking SO interneurones, for example, a temporal overlap of several K+ conductances generates spike AHPs with a fast and a slow component (Zhang & McBain, 1995). Depending on the relative contribution of these two components, with a Ca2+-dependent K+ current participating in the later component, two clearly distinct phases of the AHP are visible in only a proportion of the individual neurones. In the present study a similar fusion of two AHP components occurred in a number of cells to such an extent, that one of them was no longer detectable (marked ‘n.d.’ (not detectable) in Table 1; in Fig. 1C the TTP1 is not detectable). Such a fusion of the AHP components into one rounded event was frequently observed when enhancing GABAA receptor modulators were applied (e.g. etomidate in Fig. 4), while the two components could become more distinct when GABAA receptor antagonists were applied (e.g. bicuculline in Fig. 4).

Figure 4. Modulation of the spike AHP by etomidate and bicuculline.

On a normalised scale, the AHP amplitude (○) and the AHP width at half-amplitude (HW, ▪) are plotted against time. The arrows indicate the onset of drug applications. The lower part shows spike AHPs from different phases of the experiment.

GABAA receptor modulators also modified the spike AHPs of all five regular-spiking (Fig. 3D and E) and burst-firing basket cells investigated and the one regular-spiking bistratified cell so tested.

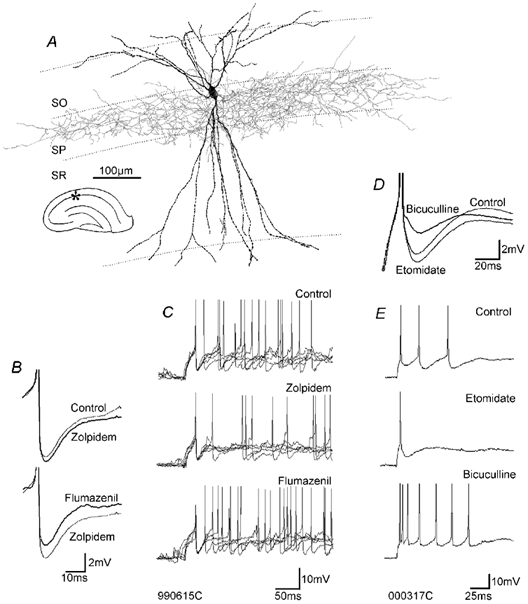

Figure 3. GABAA receptor ligands modulate the spike AHPs and discharge of fast-spiking and regular-spiking interneurones.

A, light microscopic reconstruction of a fast-spiking basket cell (the ultrastructure of its autapses is shown in Fig. 7). B, spike AHPs of the fast-spiking cell were enhanced by zolpidem and reversed by flumazenil, even beyond control levels. C, the modulation of spike AHPs by zolpidem and flumazenil was accompanied by reduced and increased neuronal excitability, respectively. In each panel, five individual traces are superimposed, with the first spikes superimposed. D, the spike AHPs of this regular-spiking basket cell were increased by etomidate and decreased by bicuculline. E, the increase in the spike AHP was accompanied by a reduction in neuronal excitability and vice versa. The discharge in C and E was elicited by injection of current pulses of 0.4 nA and 0.15 nA, respectively. Abbreviations: SO = stratum oriens, SP = stratum pyramidale, SR = stratum radiatum.

In Table 1, a spike AHP that was insensitive to zolpidem, but later enhanced by addition of diazepam is included (cell 980818b3). This probably resulted from the utilisation of GABAA receptors lacking the α1 subunit at these autapses. In contrast, the AHP of cell 980109a/b, also included in Table 1, was enhanced by zolpidem but not enhanced further by addition of diazepam, indicating that this autaptic connection involved only zolpidem-sensitive, i.e. α1-containing receptors (Sieghart, 1995; Pawelzik et al. 1999; Thomson et al. 2000).

The spike AHPs of three axo-axonic cells (one fast-spiking, one burst-firing, one regular-spiking) were not modified by the GABAA receptor modulators etomidate, diazepam or pentobarbitone, although in basket and bistratified cells etomidate had had powerful effects on seven of eight, diazepam on six of seven and pentobarbitone on one of one of the spike AHPs tested (Table 1, Fig. 5), emphasising the absence of autapses in axo-axonic cells (Somogyi et al. 1982; Freund et al. 1983). Similarly, the spike AHPs of the minor proportion of basket cells and bistratified cells that were not affected by the GABAA receptor modulators (see Table 1) showed only minute stochastic changes of the half-width of around 1 %, i.e. small variations that were not statistically significant.

Neuronal excitability

It has been shown before that neuronal excitability changes when the spike AHP is modified (Erisir et al. 1999). Where tested (n = 6), the cell excitability was modulated in parallel with the AHP (Fig. 3), i.e. an increase in the spike AHP was accompanied by a decrease in cell excitability and vice versa. In an additional six interneurones with regular-spiking or burst-firing patterns, application of GABAA antagonists resulted in a more profound burst-firing behaviour.

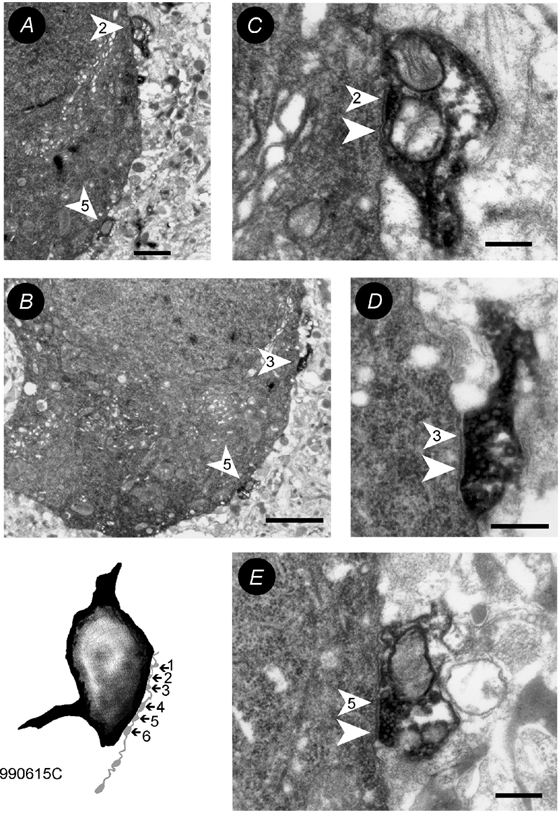

Ultrastructural identification of autapses

To test our hypothesis that autaptic inhibition modulates CA1 interneuronal spike AHPs, the autaptic connections were anatomically verified. Close appositions between axonal boutons and presynaptic and postsynaptic interneuronal targets were found in similar locations, i.e. where basket cell axons were studied, both putative synapses and autapses were on very proximal portions of the somato-dendritic domain (Fig. 6 and Fig. 7). Cells with pharmacological evidence for inhibitory self-innervation displayed one to eight close autaptic appositions (3.8 ± 0.9, n = 20, Table 1) at the light microscopic level. The anatomy of the close autaptic appositions of three of these cells was investigated by electron microscopy. All of six (Fig. 7), one of two and one of two close appositions were confirmed as autapses. Interneurones, whose spike AHPs were unaltered by the drugs tested, had significantly fewer close membrane appositions between the presynaptic axon and its parent soma-dendrites (1.3 ± 1.2, n = 6, Table 1).

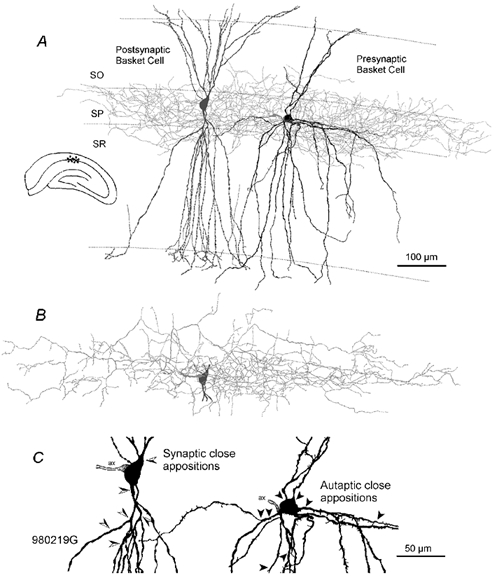

Figure 6. Light microscopic reconstruction of the pair of synaptically connected basket cells shown in Fig. 2.

A, the presynaptic basket cell (black soma-dendrites and light grey axonal arbour) generated IPSPs in the postsynaptic basket cell (dark grey, soma-dendrites only). B, axonal arbour of the postsynaptic basket cell. C, soma and proximal dendrites of the pre- and postsynaptic cell. The arrowheads indicate the sites of close apposition of the presynaptic cell's axon with the postsynaptic cell (left, semi-filled arrowheads) and with its own somato-dendritic domain (right, filled arrowheads). This magnification reveals the sparsely spiny dendrites of the presynaptic and the smooth dendrites of the postsynaptic cell. Abbreviations: ax = axon-initial segment, SO = stratum oriens, SP = stratum pyramidale, SR = stratum radiatum.

Figure 7. Electron microscopic verification of autapses.

The inset shows the drawing tube reconstruction of the soma (black) and a part of the axon (light grey) of the fast-spiking basket cell shown in Fig. 3A. The six close appositions were all confirmed to be synaptic contacts. The electron microscopic images of contacts 1 (A,C), 3 (B,D) and 5 (B,E) are shown at low (A,B) and high (C-E) magnification. The arrowheads point towards the postsynaptic densities, the numbers correspond to the number of close appositions observed at the light microscopic level. Scale bars: A = 1µm, B = 2µm, C-E = 250 nm.

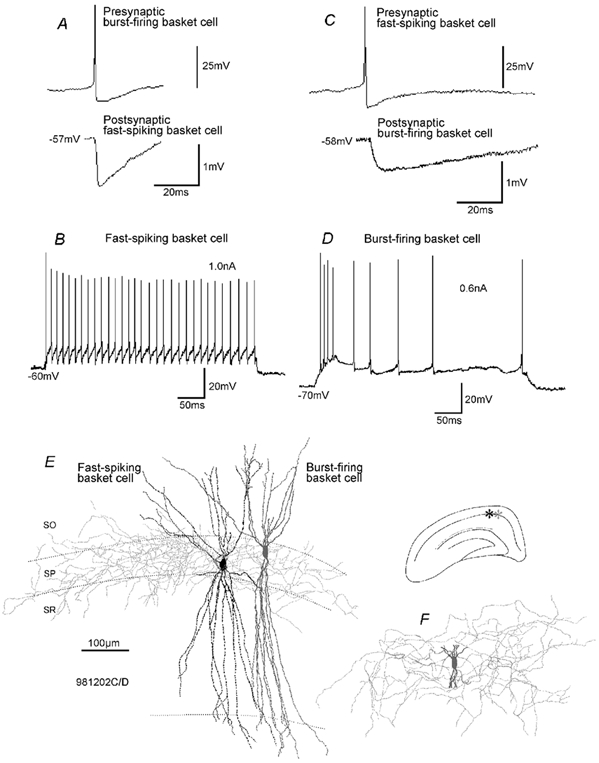

Time courses of interneurone-to-interneurone IPSPs

Our experimental approach, although strongly suggesting the involvement of autaptic IPSPs in modulation of spike AHPs, did not show autaptic IPSPs in isolation. However, since experiments in cell cultures demonstrated that the electrophysiological properties of GABAA receptor channels at synapses are similar to those at autapses (Bekkers & Stevens, 1991), we analysed interneurone-to-interneurone synaptic IPSPs. Four bistratified-to-basket cell IPSPs, five basket cell-to-bistratified cell IPSPs and 13 basket cell-to-basket cell IPSPs were recorded (Table 2). In four of these 18 pairs the two interneurones were reciprocally connected. The IPSP time course was found to be correlated not with the morphology of the pre- or the postsynaptic interneurone, but with the discharge characteristics of the postsynaptic interneurone (Table 2, Fig. 8). The IPSPs were shorter in postsynaptic fast-spiking cells (n = 16) than in regular-spiking or burst-firing cells (n = 6), with TTPs of 3.7 ± 0.9 and 5.8 ± 2.0 ms, respectively, and HWs of 13.4 ± 2.8 and 28.7 ± 5.8 ms, respectively. As the spike AHPs are also narrower in fast-spiking cells than in regular-spiking cells, the time courses of interneurone-to-interneurone IPSPs seem to match their spike AHPs. A similar picture emerges from the comparison of the smaller number of examples where IPSPs and AHPs were recorded in the same cell: for the 10 fast-spiking cells (8 basket cells and 2 bistratified cells) the HWs for the IPSP (14.5 ± 2.5 ms) and for the spike AHP (11.3 ± 1.7 ms) were shorter than in regular-spiking (n = 1) and burst-firing (n = 2) basket cells (IPSPs: 33.7 ± 3.1 ms, AHPs: 50.2 ± 53.5 ms).

Figure 8. Properties of IPSPs in a pair of reciprocally connected basket cells (one fast-spiking cell and one burst-firing cell).

A, spikes in the burst-firing basket cell generated IPSPs with a fast time course in the postsynaptic fast-spiking cell. B, discharge characteristics of the fast-spiking cell. Current injection as indicated. C, spikes in the fast-spiking basket cell generated IPSPs in the burst-firing basket cell with a relatively slow time course. D, discharge characteristics of the burst-firing basket cell. E and F, light microscopic reconstruction of the fast-spiking and the burst-firing basket cell. E, soma/dendrites (black) and axonal arbour (light grey) of the fast-spiking cell and the soma/dendrites (dark grey) of the burst-firing cell are shown. F, cropped soma/dendrites (dark grey) and axonal arbour (light grey) of the burst-firing cell.

IPSPs activated by eight of these presynaptic interneurones were also recorded in adjacent pyramidal cells (n = 8). These IPSPs had a slower time course than those recorded in postsynaptic interneurones (10–90 % rise time (RT): 6.4 ± 1.4 ms, HW: 40.7 ± 10 ms, amplitude: −0.9 ± 0.4 mV, membrane potential (MP): −57.1 ± 3.3 mV).

The membrane time constant τ, measured from the voltage responses to a −0.2 nA square wave current pulse, was 14.4 ± 3.1 ms (n = 7) in pyramidal cells, 13.4 ± 5 ms (n = 11) in regular-spiking/burst-firing interneurones and 7.4 ± 1.9 ms (n = 14) in fast-spiking interneurones. As expected, the IPSP time course depends on τ, i.e. IPSPs in pyramidal cells and regular-spiking interneurones were slower than in fast-spiking interneurones. However, additional parameters, e.g. the receptor subunit composition, should also be involved in shaping of the IPSP, as the IPSP time courses of pyramidal cells and regular-spiking/burst-firing interneurones, despite a similar τ in both cell types, exhibited different time courses with 10–90 % rise times of 6.4 ± 1.4 and 2.5 ± 0.9 ms and widths at half-amplitude of 40.7 ± 10 and 28.7 ± 5.8 ms, respectively.

Modulation of interneurone-to-interneurone IPSPs by zolpidem

Although zolpidem was found to be a relatively weak modulator of interneurone-to-pyramid IPSPs in CA1 (Thomson et al. 2000), there was a clearly detectable effect of zolpidem on the spike AHPs in interneurones. To determine therefore the effectiveness of zolpidem as a modulator of IPSPs in interneurones, five interneurone-to-interneurone connections were challenged with the drug (0.2–0.4 µm). Within 15 min all tested IPSPs were enhanced (Fig. 2, the tested connections of the pairs shown in Table 2 are marked with †). Their amplitudes were increased by 45 ± 28 % (from 1.7 ± 1.4 mV; P < 0.05, Wilcoxon-signed rank test) and their HWs by 30 ± 20 % (from 16.4 ± 6.6 ms) at MPs of 61.2 ± 6.2 mV, and continued to increase for up to 35 min. In the one pair so tested the effect of zolpidem was blocked by 4 µm flumazenil. This effect of zolpidem was stronger than the effect on interneurone-to-pyramidal cell IPSPs reported previously (Thomson et al. 2000).

This powerful effect of zolpidem on interneurone-to-interneurone IPSPs probably explains why its effects on spike AHPs were detectable. The amplitude of the spike AHP is about 10 times larger than the IPSP amplitude even when both are activated from membrane potentials close to firing threshold. A significant change in the spike AHP therefore suggests that both the underlying IPSP and its augmentation by zolpidem represented large events. However, the autaptic IPSP rides on the hyperpolarisation produced by the AHP which brings the membrane potential closer to the IPSP reversal potential.

Discussion

This study presents pharmacological and anatomical evidence for the participation of autaptic inhibition in the modulation of the discharge of hippocampal CA1 interneurones. GABAA receptor modulators modified the spike AHPs of fast-spiking and regular-spiking/burst-firing basket cells and bistratified cells, but not those of axo-axonic cells devoid of autaptic self innervation. The spike AHPs in each class of interneurone had time courses similar to interneurone-to-interneurone IPSPs in that class, and the neuronal discharge was modulated in parallel with the spike AHPs.

Summation of autaptic IPSPs and spike AHPs

In this study, the spike AHPs of two-thirds of the interneurones recorded in CA1 showed pharmacological evidence of modulation by autaptic inhibition. The magnitude and shape of any voltage change associated with the autaptic feedback in interneurones will depend strongly on the rapidly changing membrane potential during the spike AHP.

Although a detailed analysis of spike AHPs in the SP interneurones investigated in the present study is not available, it has been shown that spike repolarisations and AHPs in interneurones of other hippocampal layers are generated by a variety of unique voltage- and Ca2+-gated K+ channels (stratum oriens, Zhang & McBain, 1995; Martina et al. 1998; stratum lacunosum-moleculare, Aoki & Baraban, 2000; stratum radiatum, Savić et al. 2001). During the early phase of the spike AHP in these cells, fast potassium currents with 20–80 % rise times of < 1 ms consisting mainly of voltage-gated delayed rectifier (Martina et al. 1998; Lien et al. 2002) and smaller contributions of transient A-type (Martina et al. 1998) and fast Ca2+-activated currents (IC via large conductance BK potassium channels, Zhang & McBain, 1995), hyperpolarise the membrane by up to 30 mV negative of the spike threshold. The driving force for GABAA receptor-mediated chloride currents would approach zero, or even reverse if the membrane hyperpolarises beyond the chloride equilibrium potential. At this stage the AHP amplitude will not be significantly increased and may even be decreased by a coincident autaptic IPSP. During later, less negative phases of the AHP, as the potassium channels close (τdecay of the delayed rectifier: ≈6 ms, Martina et al. 1998; of the IA: ≈1 ms, Pelz et al. 1999; and of the IC: > 1 ms, Xia et al. 2000) the driving force for Cl− again increases, and autaptic feedback can influence the membrane potential. During this phase, small conductance Ca2+-activated SK potassium channels with slower activation time (≈5 ms) and slower decay (τdecay ≈150 ms, Vergara et al. 1998) may be activated (Zhang & McBain, 1995) together with the autaptic chloride currents. The inhibitory postsynaptic potentials (IPSCs) in fast-spiking hippocampal interneurones have 10–90 % rise times of ≈1 ms and a τdecay of ≈15–20 ms (Maccaferri et al. 2000). As the very negative membrane potentials at the early peak of the AHP will have reduced the dissipation of the Cl− gradient that occurs during large IPSPs, the later phase of the IPSPs may be able to generate a more significant effect on the membrane potential. As a result, in this study the GABAA receptor modulators more strongly and more consistently affected the spike AHP width at half-amplitude than at full amplitude. This is not to say that autapses play no role in the earlier phase of the AHP. The increased conductance they generate will shunt inward currents that would otherwise bring the cell to firing threshold more rapidly and therefore act in concert with the shunt introduced by the opening of K+ channels.

Modulation of autapses or potassium currents?

Analysing the results of the present study, it might be argued that the modulation of the spike AHPs was not caused by the drug action on autaptic GABAA receptors but on spike AHP currents (i.e. voltage- and/or Ca2+-dependent K+ currents). However, several lines of evidence suggest that the predominant effect of these drugs was on GABAA receptors in the present study. Firstly, axo-axonic cells are devoid of autaptic feed-back (Somogyi et al. 1982; Freund et al. 1983), and in the present study their spike AHPs were not affected by the tested GABAA receptor modulators diazepam, etomidate and pentobarbitone. Secondly, spike AHPs in 17 tested pyramidal cells were not affected by bicuculline (n = 4), diazepam (n = 9), etomidate (n = 1), zolpidem (n = 4), picrotoxin (n = 1) or pentobarbitone (n = 4). Thirdly, with the exception of bicuculline, the drugs used here at the concentrations that affected IPSPs and AHPs do not modulate neuronal potassium conductances (e.g. pentobarbitone: Friedrich & Urban, 1999; benzodiazepine site ligands: Ishizawa et al. 1997; etomidate: Friedrich et al. 2001; picrotoxin: Debarbieux et al. 1998) or calcium conductances (e.g. etomidate, pentobarbitone: Todorovic & Lingle, 1998; benzodiazepine site ligands: Ishizawa et al. 1997; picrotoxin: Debarbieux et al. 1998). Even high concentrations of picrotoxin (Debarbieux et al. 1998) and flumazenil do not affect K+ channels (Ishizawa et al. 1997), while high concentrations of pentobarbitone (Friedrich & Urban, 1999), diazepam (Ishizawa et al. 1997) and etomidate (Friedrich et al. 2001) attenuate K+ currents. Therefore, if these drugs had modulated K+ currents in the present study, the spike AHPs would have been attenuated rather that enhanced.

Bicuculline, in addition to blocking autaptic IPSPs, might also have modulated SK potassium channels (Debarbieux et al. 1998), which can be involved in the generation of spike AHPs in hippocampal interneurones (Zhang & McBain, 1995; Aoki & Baraban, 2000; Savić et al. 2001). However, the spike AHPs of interneurones with little or no morphological evidence of autapses were not decreased by bicuculline. This would suggest that these interneuronal AHP currents are relatively insensitive to bicuculline.

Possible functional roles of autapses

Analysing the width at half-amplitude, the present study shows that autaptic potentials are indeed involved in shaping the spike AHPs of many fast-spiking and regular-spiking/burst-firing interneurones, and hence are involved in the modulation of the neuronal discharge characteristics. In previous studies, at least two broad classes of fast-spiking interneurones were reported in the hippocampus: those with triangular and those with rounded spike AHPs (Ali et al. 1999; Pawelzik et al. 1999; Thomson et al. 2000). It appears that a substantial part of the slower component, which underlies the rounded appearance of the AHP in the second group, is contributed by autaptic inhibition. In favour of this hypothesis is the fact that bicuculline and picrotoxin converted the rounded AHP into a more triangular AHP. Moreover, the time courses for the AHPs (HW: 12.5 ± 5.7 ms) and the IPSPs generated in fast-spiking postsynaptic interneurones (HW: 13.4 ± 2.8 ms) are very similar (as were the IPSPs and AHPs in regular-spiking interneurones). Finally, spike AHPs of fast-spiking axo-axonic cells, which do not form autapses (Somogyi et al. 1982; Freund et al. 1983), are never rounded and are much briefer (HW: 3.9 ± 0.7 ms) than those of basket cells and bistratified cells, and in this study the spike AHPs of the three axo-axonic cells tested were not modulated by etomidate, diazepam or pentobarbitone.

This study shows that autaptic inhibitory inputs can modulate the discharge of individual interneurones. Hippocampal interneurones are critically involved during phases of rhythmic network activity at theta frequencies (Cobb et al. 1995; Freund & Buzsáki, 1996) and at gamma frequencies (Freund & Buzsáki, 1996; Whittington et al. 1997). Autaptic self-innervation may help to stabilise the firing pattern during episodes of network oscillation. In Aplysia interneurones it has been shown that autapses can make cell firing more regular (White & Gardner, 1981). In CA1, fast-spiking basket cells with little or no autaptic feedback, like bistratified cells with more distal dendritic autapses or axo-axonic cells devoid of autapses (Somogyi et al. 1982; Freund et al. 1983), show signs of irregular spiking. The firing of spike doublets by regular-spiking axo-axonic cells (Buhl et al. 1994) could be a consequence of the lack of autaptic feedback. When discharging at gamma frequencies, fast-spiking axo-axonic cells always (8 of 8 cells) and fast-spiking bistratified cells often (9 of 14 cells) fired groups of action potentials interrupted by periods of silence in the present series. Fast-spiking basket cells with relatively strong and proximal autaptic feedback, however, only rarely (9 of 39 cells) interrupted their firing spontaneously. If basket cells are indeed the motor in the perpetuation of hippocampal gamma network oscillations (Whittington et al. 1997), the summation of spike AHP and autaptic shunting would help to stabilise a continuous uninterrupted discharge at gamma frequencies (Penttonen et al. 1998; Pike et al. 2000). Finally, autaptic inhibitory feedback might also play a role in adapting neuronal network properties to humoral changes. Steroids, for example, which can powerfully modulate GABAA receptors (Lambert et al. 2001), exhibit a large physiological range in plasma and brain concentration (Steiger & Holsboer, 1997). The results presented here would suggest that both autaptic and synaptic inhibition will be modulated in parallel, with the firing of presynaptic interneurones changing to match the interspike intervals imposed on their postsynaptic interneuronal targets by the IPSPs they generate in them.

Interneurone-to-interneurone IPSPs

The present study confirms that IPSP time courses in postsynaptic interneurones are faster than those in pyramidal cells (hippocampus: Ali et al. 1999; neocortex: Thomson & Destexhe, 1999), i.e. the postsynaptic cell determines the time course of the IPSP. In hippocampal interneurone-to-interneurone connections, at least within the population of basket cells and bistratified cells, the IPSP time course is also correlated with the firing characteristics of the postsynaptic cell. Interneurone-to-interneurone IPSPs generated in regular-spiking and burst-firing cells are significantly longer-lasting than those generated in fast-spiking cells with HWs of 28.7 ± 5.8 and 13.4 ± 2.8 ms (P < 0.0001), respectively. Immunohistochemical studies have demonstrated a high proportion of α1 subunits in interneurones, while α2 subunits predominate in principal cells (Stimbürger et al. 2001). It was demonstrated with recombinant receptors expressed in HEK 293 cells that the GABAA receptor current deactivation time course in receptors containing α1 subunits is 6–7 times faster than in receptors containing only α2 subunits (Lavoie et al. 1997). Two of our experimental results confirm this predominance of α1 over α2 subunits at interneurone-to-interneurone synapses: IPSPs generated in interneurones are not only faster than those generated in pyramidal cells, but they are also more sensitive to the α1-selective GABAA receptor modulator zolpidem. In the present study zolpidem increased the amplitude of the IPSPs generated in postsynaptic interneurones by 44.6 ± 27.7 % within 15 min, while the same concentration of zolpidem enhanced IPSPs generated by regular-spiking and by fast-spiking basket cells in postsynaptic pyramidal cells only by 9 and 22 %, respectively (Thomson et al. 2000). The differential modulation of these two types of IPSPs in pyramidal cells by zolpidem parallels the different proportions of α1/α2 subunits in the GABAA receptors postsynaptic to the parvalbumin-immunopositive and parvalbumin-immunonegative interneurones that were reported to correspond to fast-spiking and regular spiking basket cells, respectively (Kawaguchi & Kubota, 1997; 1998; Nyíri et al. 2001). These different combinations of GABAA receptor subunits may also contribute to the different time courses of IPSPs in fast-spiking and regular-spiking interneurones (Miralles et al. 1999). Finally, the IPSP properties could change with the functional state of a receptor due to the action of cell-specific proteins, e.g. metabotropic calcium-binding proteins (McDonald et al. 1998; Poisbeau et al. 1999; Hájos et al. 2000).

Electrical coupling

The pharmacological results presented here could theoretically have been generated by the activation of other interneurones that were both synaptically connected and electrically coupled to the recorded cells. However, the removal of electrical coupling per se by conventional uncouplers would have added an additional complication to data interpretation. Gap junction uncouplers not only interact with connexins but also with other membrane proteins, including several channel proteins (Verrecchia & Herve, 1997) and those involved in GABAergic transmission (Venance et al. 1995; discussion in Shinohara et al. 2000) and therefore they were not used in the present study. Under these circumstances the depolarisation and action potentials in the recorded cell could then have triggered action potentials in other electrically coupled interneurones that in turn elicited IPSPs in the recorded cell. In favour of this theory is the fact that in the hippocampus there are interneurone classes in which gap junctions could be demonstrated (Gulyás et al. 1996; Fukuda & Kosaka, 2000). However, the calretinin immunoreactive interneurones demonstrated by Gulyás et al. (1996), with dendritic appositions reminiscent of gap junctions, show an anatomy different from the cell anatomy in the present study, while the anatomy of the parvalbumin-immunoreactive interneurones demonstrated by Fukuda & Kosaka (2000) remains unclear. However, as the gap junctions of the latter cell class were established between horizontal dendrites running along the stratum oriens-alveus border they were probably mostly a feature of horizontally oriented interneurones of the stratum oriens and alveus (Maccafferi et al. 2000), a cell class not recorded in the present study.

Several additional lines of evidence indicate that the majority of interneurones recorded in our study probably did not belong to the population of gap junction-coupled cells. Firstly, in comparison to the neocortex or the dentate gyrus, there is generally a low incidence of electrical coupling in the CA1 region of the adult hippocampus (Fukuda & Kosaka, 2000; Maccaferri et al. 2000; McBain & Fisahn, 2001), while in parallel we found morphological and ultrastructural proof of a high incidence of autaptic feedback connections. Moreover, in 19 pairs of synaptically connected interneurones recorded, in only one case was there any indication of electrical coupling, i.e. depolarisation of one cell was accompanied by the depolarisation of the other cell, and this coupling was far too weak to bring the follower cell to action potential threshold. The labelled cells of this pair showed close appositions between their distal dendrites, while in none of the remaining 18 pairs were close appositions of dendritic or somatic portions evident. Finally, interneurones, in which ‘spikelets’ indicative of electrical coupling to other cells (McBain & Fisahn, 2001) were observed, were excluded from this study.

Even if silent interneurones, i.e. those not revealing their presence in form of ‘spikelets’, were electrically coupled to the recorded interneurones, it is difficult to imagine how in our recording situation they could have produced consistent effects on the spike AHPs. We used just-suprathreshold current injections to discharge the recorded interneurones, and voltage responses in pairs of electrically coupled cells are transmitted in a strongly attenuated manner from one cell to another (Meyer et al. 2000). Even if the relatively small current injections into the recorded cells were sufficient to discharge prospective electrically coupled adjacent interneurones, this discharge would neither have been reliable nor consistent and time-locked, i.e. it would not have been able to generate a consistent modulation of the spike AHPs. Nevertheless, it cannot be excluded that electrical coupling in our study contributed some distortion of the averaged spike AHPs. However, the modulation by autaptic feedback was probably the predominant effect reported here. Thus, although electrical coupling amongst interneurones that are also synaptically connected could play a predominant role under certain conditions, the present evidence points to autaptic connections as the prime mediators of the effects of the GABAA receptor ligands on interneurone spike AHPs and discharge reported here.

Acknowledgments

We thank Mr A. P. Bannister for technical assistance and help with the histological processing and Dr M. Ilia for drawing of the cell pair shown in Fig. 8. This work was supported by the Medical Research Council and Novartis Pharma (Basel).

References

- Ali AB, Bannister AP, Thomson AM. IPSPs elicited in CA1 pyramidal cells by putative basket cells in slices of adult rat hippocampus. Eur J Neurosci. 1999;11:1741–1753. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.1999.00592.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aoki T, Baraban SC. Properties of a calcium-activated K+ current on interneurons in the developing rat hippocampus. J Neurophysiol. 2000;83:3453–3461. doi: 10.1152/jn.2000.83.6.3453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bekkers JM, Stevens CF. Excitatory and inhibitory autaptic currents in isolated hippocampal neurons maintained in cell culture. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1991;88:7834–7838. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.17.7834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buhl EH, Han Z-S, Lörinczi Z, Stezhka VV, Karnup SV, Somogyi P. Physiological properties of anatomically identified axo-axonic cells in the rat hippocampus. J Neurophysiol. 1994;71:1289–1307. doi: 10.1152/jn.1994.71.4.1289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen G, Van Den Pol AN. Multiple NPY receptors coexist in pre- and postsynaptic sites: inhibition of GABA release in isolated self-innervating SCN neurons. J Neurosci. 1996;16:7711–7724. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-23-07711.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cobb SR, Buhl EH, Halasy K, Paulsen O, Somogyi P. Synchronization of neuronal activity in hippocampus by individual GABAergic interneurons. Nature. 1995;378:75–78. doi: 10.1038/378075a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cobb SR, Halasy K, Vida I, Nyiri G, Tamás G, Buhl EH, Somogyi P. Synaptic effects of identified interneurons innervating both interneurons and pyramidal cells in the rat hippocampus. Neurosci. 1997;79:629–648. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(97)00055-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Debarbieux F, Brunton J, Charpak S. Effect of bicuculline on thalamic activity: a direct blockade of IAHP in reticularis neurons. J Neurophysiol. 1998;79:2911–2918. doi: 10.1152/jn.1998.79.6.2911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erisir A, Lau D, Rudy B, Leonard CS. Function of specific K+ channels in sustained high-frequency firing of fast-spiking neocortical interneurons. J Neurophysiol. 1999;82:2476–2489. doi: 10.1152/jn.1999.82.5.2476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franck JE, Pokorny J, Kunkel DD, Schwartzkroin PA. Physiologic and morphologic characteristics of granule cell circuitary in human epileptic hippocampus. Epilepsia. 1995;36:543–558. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1157.1995.tb02566.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freund TF, Buzsáki G. Interneurons of the hippocampus. Hippocampus. 1996;6:347–470. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-1063(1996)6:4<347::AID-HIPO1>3.0.CO;2-I. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freund TF, Martin KAC, Smith AD, Somogyi P. Glutamate decarboxylase-immunoreactive terminals of Golgi-impregnated axo-axonic cells and of presumed basket cells in synaptic contact with pyramidal neurons of the cat's visual cortex. J Comp Neurol. 1983;221:263–278. doi: 10.1002/cne.902210303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedrich P, Prellakis S, Urban BW. Epileptic seizures from etomidate? The human Kv1. 1 potassium channel in humans. Anasthesiologie, Intensivmedizin, Notfallmedizin, Schmerztherapie: AINS. 2001;36:100–104. doi: 10.1055/s-2001-11054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedrich P, Urban BW. Interaction of intravenous anesthetics with human neuronal potassium currents in relation to clinical concentrations. Anesthesiology. 1999;91:1853–1860. doi: 10.1097/00000542-199912000-00040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukuda T, Kosaka T. Gap junctions linking the dendritic network of GABAergic interneurons in the hippocampus. J Neurosci. 2000;20:1519–1528. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-04-01519.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gulyás AI, Hájos N, Freund TF. Interneurons containing calretinin are specialized to control other interneurons in the rat hippocampus. J Neurosci. 1996;16:3397–3411. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-10-03397.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hájos N, Katona I, Naiem SS, Mackie K, Ledent C, Mody I, Freund T. Cannabinoids inhibit hippocampal GABAergic transmission and network oscillations. Eur J Physiol. 2000;12:3239–3249. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.2000.00217.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes DI, Bannister AP, Pawelzik H, Thomson AM. Double immunofluorescence, peroxidase labelling and ultrastructural analysis of interneurones following prolonged electrophysiological recordings in vitro. J Neurosci Meth. 2000;101:107–116. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0270(00)00254-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishizawa Z, Furyua K, Yamagishi S, Dohi S. Non-GABAergic effects of midazolam, diazepam and flumazenil on voltage-dependent ion currents in NG108–15 cells. Neuroreport. 1997;8:2635–2638. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199707280-00042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karabelas AB, Purpura DP. Evidence for autapses in the substantia nigra. Brain Res. 1980;200:467–473. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(80)90935-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawaguchi Y, Kubota Y. GABAergic cell subtypes and their synaptic connections in rat frontal cortex. Cerebral Cortex. 1997;7:476–486. doi: 10.1093/cercor/7.6.476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawaguchi Y, Kubota Y. Neurochemical features and synaptic connections of large physiologically-identified GABAergic cells in the rat frontal cortex. Neurosci. 1998;85:677–701. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(97)00685-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lambert JJ, Belelli D, Herney SC, Peters JA, Frenguelli BG. Modulation of native and recombinant GABA(A) receptors by endogenous and synthetic neuroactive steroids. Brain Res Rev. 2001;37:68–80. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0173(01)00124-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lavoie AM, Tingey JJ, Harrison NL, Pritchett DB, Twyman RE. Activation and deactivation rates of recombinant GABA(A) receptor channels are dependent on alpha-subunit isoform. Biophys J. 1997;73:2518–2526. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(97)78280-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lien C-C, Martina M, Schultz JH, Ehmke H, Jonas P. Gating, modulation and subunit composition of voltage-gated K+ channels in dendritic inhibitory interneurones of rat hippocampus. J Physiol. 2002;538:405–419. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2001.013066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lübke J, Markram H, Frotscher M, Sakmann B. Frequency and dendritic distribution of autapses established by layer 5 pyramidal neurons in the developing rat neocortex: comparison with synaptic innervation of adjacent neurons of the same class. J Neurosci. 1996;16:3209–3218. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-10-03209.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McBain CJ, Fisahn A. Interneurons unbound. Nature Rev Neurosci. 2001;2:11–23. doi: 10.1038/35049047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maccaferri G, Roberts JdB, Szucs P, Cottingham CA, Somogyi P. Cell surface domain specific postsynaptic currents evoked by identified GABAergic neurones in rat hippocampus in vitro. J Physiol. 2000;524:91–116. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2000.t01-3-00091.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDonald BJ, Amato A, Connolly CN, Benke D, Moss SJ, Smart TG. Adjacent phosphorylation sites on GABAA receptor beta subunits determine regulation by cAMP-dependent protein kinase. Nature Neurosci. 1998;1:23–28. doi: 10.1038/223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martina M, Schultz JH, Ehmke H, Monyer H, Jonas P. Functional and molecular differences between voltage-gated K+ channels of fast-spiking interneurons and pyramidal neurons of rat hippocampus. J Neurosci. 1998;18:8111–8125. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-20-08111.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mennerick S, Jevtovic-Todorovic V, Todorovic SM, Shen W, Olney JW, Zorumski CF. Effect of nitrous oxide on excitatory and inhibitory synaptic transmission in hippocampal cultures. J Neurosci. 1998;18:9716–9726. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-23-09716.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer AH, Katona I, Blatow M, Rozov A, Monyer H. In vivo labeling of parvalbumin-positive interneurons and analysis of electrical coupling in identified neurons. J Neurosci. 2002;22:7055–7064. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-16-07055.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miralles CP, Li M, Metha AK, Khan ZU, Deblas AL. Immunocytochemical localization of the beta(3) subunit of the gamma-aminobutyric acid(A) receptor in the rat brain. J Comp Neurol. 1999;413:535–548. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nyíri G, Freund TF, Somogyi P. Input-dependent synaptic targeting of α2-subunit containing GABAA receptors in synapses of hippocampal pyramidal cells of the rat. Eur J Neurosci. 2001;13:428–442. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.2001.01407.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park MR, Lighthall JW, Kitai ST. Recurrent inhibition in the rat neostriatum. Brain Res. 1980;194:359–369. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(80)91217-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pawelzik H, Bannister AP, Deuchars J, Ilia M, Thomson AM. Modulation of bistratified cell IPSPs and basket cell IPSPs by pentobarbitone sodium, diazepam and Zn2+: dual recordings in slices of adult rat hippocampus. Eur J Neurosci. 1999;11:3552–3564. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.1999.00772.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pawelzik H, Hughes DI, Bannister AP, Thomson AM. Autapses modulate discharge characteristics in hippocampal interneurones. J Physiol. 2000;526.P:60P. [Google Scholar]

- Pelz C, Jander J, Rosenboom H, Hammer M, Menzel R. IA in kenyon cells of the mushoroom body of honeybees resembles shaker currents: kinetics, modulation by K+, and stimulation. J Neurophysiol. 1999;81:1749–1759. doi: 10.1152/jn.1999.81.4.1749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Penttonen M, Kamondi A, Acsady L, Buzsáki G. Gamma frequency oscillation in the hippocampus of the rat: intracellular analysis in vivo. Eur J Neurosci. 1998;10:718–728. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.1998.00096.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peters A, Proskauer CC. Synaptic relationships between a multipolar stellate cell and a pyramidal neuron in the rat visual cortex. A combined Golgi-electron microscope study. J Neurocytol. 1980;9:163–183. doi: 10.1007/BF01205156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pike FG, Goddard RS, Suckling JM, Ganter P, Kasthuri N, Paulsen O. Distinct frequency preferences of different types of rat hippocampal neurones in response to oscillatory input currents. J Physiol. 2000;529:205–213. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2000.00205.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poisbeau P, Cheney MC, Browning MD, Mody I. Modulation of synaptic GABAA receptor function by PKA and PKC in adult hippocampal neurons. J Neurosci. 1999;19:674–683. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-02-00674.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pouzat C, Marty A. Autaptic inhibitory currents recorded from interneurones in rat cerebellar slices. J Physiol. 1998;509:777–783. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1998.777bm.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Savić N, Pedarzani P, Sciancalepore M. Medium afterhyperpolarization and firing pattern modualtion in interneurons of stratum radiatum in the CA3 hippocampal region. J Neurophysiol. 2001;85:1986–1997. doi: 10.1152/jn.2001.85.5.1986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shinohara K, Hiruma H, Funabashi T, Kimura F. GABAergic modulation of gap junction communication in slice cultures of the rat suprachiasmatic nucleus. Neurosci. 2000;96:591–596. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(99)00556-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sieghart W. Structure and pharmacology of γ-aminobutyric acidA receptor subtypes. Pharmacol Rev. 1995;47:181–234. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steiger A, Holsboer F. Nocturnal secretion of prolactin and cortisol and the sleep EEG in patients with major endogenous depression during an acute episode and after full remission. Psychiatry Res. 1997;72:81–88. doi: 10.1016/s0165-1781(97)00097-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stimbürger E, Plaschke M, Fritschy J-M, Nitsch R. Localization of two major GABAA receptor subunits in the dentate gyrus of the rat and cell type-specific up-regulation following entorhinal cortex lesion. Neurosci. 2001;102:789–803. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(00)00505-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takagi H, Somogyi P, Smith AD. Aspiny neurons and their local axons in the neostriatum of the rat: a correlated light and electron microscopic study of Golgi-impregnated material. J Neurocytol. 1984;13:239–265. doi: 10.1007/BF01148118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamás G, Buhl EH, Somogyi P. Massive autaptic self-innervation of GABAergic neurons in cat visual cortex. J Neurosci. 1997;17:6352–6363. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-16-06352.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomson AM, Bannister AP, Hughes DI, Pawelzik H. Differential sensitivity to Zolpidem of IPSPs activated by morphologically identified CA1 interneurones in slices of rat hippocampus. Eur J Neurosci. 2000;12:425–436. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.2000.00915.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomson AM, Destexhe A. Dual intracellular recordings and computational models of slow inhibitory postsynaptic potentials in rat neocortical and hippocampal slices. Neurosci. 1999;92:1193–1215. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(99)00021-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomson AM, West DC, Hahn J, Deuchars J. Single axon IPSPs elicited in pyramidal cells by three classes of interneurones in slices of rat neocortex. J Physiol. 1996;496:81–102. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1996.sp021667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Todorovic SM, Lingle CJ. Pharmacological properties of T-type Ca2+ current in adult rat sensory neurons: effects of anticonvulsant and anesthetic agents. J Neurophysiol. 1998;79:240–252. doi: 10.1152/jn.1998.79.1.240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Der Loos H, Glaser EM. Autapses in neocortical cerebri: synapses between a pyramidal cell's axon and its own dendrites. Brain Res. 1972;48:355–360. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(72)90189-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Venance L, Piomelli D, Glowinski J, Giaume C. Inhibition by anandamide of gap junctions and intrercellular calcium signalling in striatal astrocytes. Nature. 1995;376:590–594. doi: 10.1038/376590a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vergara C, Latorre R, Marrion NV, Adelman JP. Calcium-activated potassium channels. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 1998;8:321–329. doi: 10.1016/s0959-4388(98)80056-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verrecchia F, Herve JC. Reversible inhibition of gap junctional communication elicited by several classes of lipophilic compounds in cultured rat cardiomyocytes. Can J Cardiol. 1997;13:1093–1100. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White RL, Gardner D. Self-inhibition alters firing patterns of neurons in Aplysia buccal ganglia. Brain Res. 1981;209:77–93. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(81)91173-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whittington MA, Stanford IM, Collings SB, Jeffreys JGR, Traub RD. Spatio-temporal pattern of gamma-frequency oscillations tetanically induced in the rat hippocampal slice. J Physiol. 1997;502:591–607. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1997.591bj.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xia X-M, Ding J-P, Zeng X-H, Duan K-L, Lingle CJ. Rectification and rapid activation at low Ca2+ of Ca2+-activated, voltage-dependent BK currents: consequences of rapid inactivation by a novel β subunit. J Neurosci. 2000;20:4890–4903. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-13-04890.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang L, McBain CJ. Potassium conductances underlying repolarization and afterhyperpolarization in rat CA1 hippocampal interneurones. J Physiol. 1995;488:661–672. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1995.sp020998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]