Abstract

Salivary gland fluid secretion is driven by transepithelial Cl− movement involving an apical Cl− channel whose molecular identity remains unknown. Extracellular ATP (ATPo) has been shown to activate a Cl− conductance (IATPCl) in secretory epithelia; to gain further insight into IATPCl in mouse parotid acinar cells, we investigated the effects of ATPo using the whole-cell patch-clamp technique. ATPo and 2′- and 3′-O-(4-benzoylbenzoyl)adenosine 5′-triphosphate triethylammonium salt (Bz-ATP) produced concentration-dependent, time-independent Cl− currents with an EC50 of 160 and 15 µm, respectively. IATPCl displayed a selectivity sequence of SCN− > I− = NO3− > Cl− > glutamate, similar to the Cl− channels activated by Ca2+, cAMP and cell swelling in acinar cells. In contrast, IATPCl was insensitive to pharmacological agents that are known to inhibit these latter Cl− channels, was independent of Ca2+ and was not regulated by cell volume. Moreover, the IATPCl magnitude from wild-type animals was comparable to that from mice with null mutations in the Cftr, Clcn3 and Clcn2Cl− channel genes. Taken together, our results demonstrate that IATPCl is distinct from the channels described previously in acinar cells. The activation of IATPCl by Bz-ATP suggests that P2 nucleotide receptors are involved. However, inhibition of G-protein activation with GDP-β-S failed to block IATPCl, and Cibacron Blue 3GA and 4,4′-diisothyocyanostilbene-2,2′-disulphonic disodium salt selectively inhibited the Na+ currents (presumably through P2X receptors) without altering IATPCl, suggesting that neither P2Y nor P2X receptors are likely to be involved in IATPCl activation. We conclude that IATPCl is not associated with Cl− channels previously characterized in mouse parotid acinar cells, nor is it dependent on P2 nucleotide receptor stimulation. IATPCl expressed in acinar cells reflects the activation of a novel ATP-gated Cl− channel that may play an important physiological role in salivary gland fluid secretion.

Salivary gland acinar cells express multiple types of Cl− channels including Ca2+-dependent and volume-sensitive channels (Arreola et al. 1996b; Begenisich & Melvin, 1998; Melvin, 1999), as well as the cAMP-dependent cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR) and the voltage-regulated ClC-2 and ClC-3 Cl− channels (Zeng et al. 1997b; Arreola et al. 2002a,b; Nehrke et al. 2002). Salivation requires extracellular Ca2+ (Douglas & Poisner, 1963), suggesting that Ca2+-dependent Cl− channels may be the major apical Cl− conductance driving fluid secretion (Arreola et al. 1996a). However, whole-cell patch-clamp studies indicate that the Ca2+-activated Cl− current decays rapidly (Nishiyama & Petersen, 1974; Iwatsuki et al. 1985; Sasaki & Gallacher, 1990), inconsistent with Ca2+-dependent Cl− channels being the only channels required for salivation. Given the transient activation of the Ca2+-dependent Cl− channels, it was surprising to find that targeted disruption of the Clcn2, Clcn3 and CftrCl− channel genes had no apparent effect on the salivary flow rate (Arreola et al. 2002b; Nehrke et al. 2002; H.-V. Nguyen, unpublished observations). This suggests that under physiological conditions, Ca2+-dependent Cl− channels do not decay, or that an additional Cl− channel is activated in response to stimulation, possibly mediated through an unknown, Ca2+-independent mechanism.

The modulation of Cl− efflux from airway epithelia by external ATP (Stutts et al. 1992; Schwiebert et al. 1995) suggests a potential application for treating cystic fibrosis, a disease characterized by the loss of cAMP-activated Cl− conductance and defective fluid secretion (Quinton, 1983). In normal airway epithelia and salivary glands, extracellular ATP increases the Cl− permeability (Stutts et al. 1992; Schwiebert et al. 1995, Zeng et al. 1997a). In airway epithelia, by acting on nearby nucleotide receptors ATP can increase the open probability of the outward rectifying Cl− channels (ORCC), possibly by an autocrine mechanism (Stutts et al. 1992; Schwiebert et al. 1995). However, there is no evidence for the presence of ORCC in salivary acinar cells to suggest that the increase in Cl− permeability is due to the same mechanism. In addition, P2 nucleotide receptors may play a significant role by enhancing the Ca2+-dependent secretion as a result of an increase in the membrane permeability to Ca2+ and Na+ (P2X4 and P2X7) and/or by modulating Ca2+ signalling through enhanced G-protein-coupled inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate production (P2Y1 and P2Y2). In salivary glands, the physiological role of the P2X4, P2X7, P2Y1 and P2Y2 nucleotide receptors remain to be determined (Park et al. 1997; Turner et al. 1997, 1999; Tenneti et al. 1998). P2 nucleotide receptors may play a significant role in Ca2+-dependent salivary gland secretion by similar mechanisms to those proposed in airway epithelia. Indeed, P2 nucleotide receptor stimulation could regulate the activity of Ca2+-dependent Cl− channels in submandibular acinar cells, where it has been shown that Ca2+ and G-protein signals converge to activate this channel (Martin, 1993). In addition, the results of Zeng et al. (1997a) suggest that P2 nucleotide receptor activation stimulates fluid secretion by activating the Ca2+-dependent Cl− channels and a Ca2+-insensitive, CFTR-like Cl− current in submandibular cells.

It is interesting to note that pancreatic acini release ATP during cholinergic receptor stimulation (Sorensen & Novak, 2001), the major stimulus for triggering salivary gland fluid secretion. Thus, if cholinergic stimulation induces release of ATP in salivary acinar cells, it may regulate fluid secretion in an autocrine fashion by activating P2 nucleotide receptors. However, we found that external ATP did not act through nucleotide receptors to activate Cl− channels. Instead, ATP stimulated a Cl− conductance (IATPCl) with unique pharmacological and kinetic properties distinct from the Cl− channels described previously in salivary gland acinar cells. We hypothesize that IATPCl represents a novel Cl− channel that is gated directly by external ATP.

METHODS

Single parotid acinar cell dissociation

Single acinar cells were dissociated from mouse parotid glands following a protocol approved by the Animal Resources Committee of the University of Rochester as previously described (Arreola et al. 2002a). Briefly, glands were dissected from exsanguinated mice after exposure to a rising concentration of CO2. Glands were minced in Ca2+-free minimum essential medium (MEM; Gibco BRL, Gaithersburg, MD, USA) supplemented with 1 % bovine serum albumin (BSA; Fraction V, Sigma, St Louis, MO, USA). The tissue was treated for 20 min (37 °C) in Ca2+-free MEM solution containing 0.02 % trypsin, 1 mm EDTA, 2 mm glutamine and 1 % BSA. Digestion was stopped with 2 mg ml−1 of soybean trypsin inhibitor (Sigma) and the tissue dispersed further by two sequential treatments of 60 min each with collagenase p (0.04 mg ml−1, Boehringer Mannheim, Germany) in Ca2+-free MEM with 2 mm glutamine and 1 % BSA. The dispersed cells were centrifuged (500 g) and washed with basal medium Eagle (BME; Gibco BRL). The final pellet was resuspended in BME with 2 mm glutamine and cells were plated onto poly-l-lysine-coated glass coverslips for electrophysiological recordings.

Electrophysiological recordings

Cl− currents were recorded at room temperature (20–22 °C) using the conventional whole-cell patch-clamp configuration (Hamill et al. 1981) and an Axopatch 200B amplifier (Axon Instruments). Patch pipettes were pulled to have a resistance of 2–4 MΩ when filled with the standard pipette (internal) solution containing (mm): TEA-Cl 140, EGTA 20 and Hepes 20, pH 7.3, tonicity ≈335 mmol kg−1. Cells were bathed in a standard external solution containing (mm): TEA-Cl 140, CaCl2 0.5, d-mannitol 100 and Hepes 20, pH 7.3, tonicity ≈375 mmol kg−1. The internal solution was designed to have nearly zero free [Ca2+] and the external to be slightly hypertonic to avoid the activation of the Ca2+-dependent and volume-sensitive Cl− channels present in mouse parotid acinar cells (Nehrke et al. 2002). In addition, we observed that IATPCl was sustained at positive voltages, thus most of our analysis was done at +80 mV. This eliminated the current from hyperpolarization-activated ClC-2 Cl− channels (Arreola et al. 2002a) and avoided the decay of the IATPCl observed at negative voltages with pulses of > 1 s duration. To further eliminate current through ClC-2 channels and the current decay, current-voltage (I-V) relationships of the ATP-activated conductance were constructed from data collected using 40 or 400 ms pulses (Fig. 2). Characterization of the complex nature of the decay of IATPCl at negative voltages is beyond the scope of this paper and is currently under investigation. To activate volume-sensitive channels, the standard external solution was made hypotonic by omitting d-mannitol. Inwardly rectifying Cl− currents were recorded from cells after 10–15 min dialysis with the standard internal solution while bathed in the standard external solution (Arreola et al. 2002a). Ca2+-dependent Cl− currents were recorded from cells bathed in the standard external hypertonic solution and dialysed with a solution containing (mm): N-methyl-d-glutamine (NMDG)-glutamate 80, NMDG-EGTA 50, CaCl2 30 and Hepes 20, pH 7.3 with NMDG. The free [Ca2+] of this pipette solution was estimated to be 250 nm (WinMax 2, Stanford, CA, USA).

Figure 2. Voltage dependence of ATP-activated currents.

A, currents obtained in the absence (left) and presence of 5 mm Tris-ATP (right). The membrane potential (Vm) was changed from −80 to +100 mV in 20 mV increments from a holding potential of 0 mV. B, current-voltage relationship of the ATP-activated current. Current amplitudes were measured at the end of the 400 ms pulse. Control currents in the absence of ATP were subtracted to obtain the ATP-activated current amplitude (n = 9).

To assay the effects of anions on reversal potentials, Cl− was replaced with equimolar concentrations of SCN−, I−, NO3− or glutamate. An external solution with zero Ca2+ was made by adding 20 mm EGTA and no Ca2+ to the standard external solution. Na+ currents were recorded from cells bathed in an external solution containing (mm): Na-glutamate 139, CaCl2 0.5, d-mannitol 100 and Hepes 20, pH 7.3, and dialysed with a pipette solution containing (mm): Na-glutamate 140, EGTA 20 and Hepes 20, pH 7.3. Tris-ATP or Bz-ATP was added to the external solution at the desired concentration and then the pH readjusted to 7.3 with TEA-OH. Solutions were gravity-perfused at a flow rate of about 4 ml min−1 through the recording chamber (volume ≈0.2 ml), which was grounded using a 300 mm KCl agar bridge. Macroscopic currents as described in each figure were recorded by delivering square pulses to +80 mV from a holding potential of 0 mV. The reversal potentials under different anionic conditions were determined from I-V relationships constructed with data collected from −80 to +100 mV in 20 steps using 40 ms pulses. Currents were filtered at 1 or 5 kHz using an 8 db/decade low-pass Bessel filter and sampled using the pCLAMP 8 software (Axon Instruments). Data are presented as the mean ± s.e.m. without correction for leak current. Liquid junction potentials were less than 2 mV and, therefore, no correction was applied.

Analysis

The ATP-activated current was obtained by subtracting the current observed prior to the addition of ATP. Permeability ratios (PX/PCl) were estimated from the reversal potential shift (ΔEr) induced by replacing extracellular Cl− with anion X using the Goldman, Hodgkin and Katz equation:

| (1) |

where Er(X) and Er(Cl) are the reversal potentials determined experimentally in the presence of 140 mm of X = SCN−, I−, NO3− or glutamate, and 141 mmCl−, respectively. R, T, z and F have their usual thermodynamic meanings. Concentration-response curves to Bz-ATP and ATP were analysed using a Hill equation:

|

(2) |

where [A] is the agonist concentration, EC50 is the agonist concentration to achieve 50 % of the maximum response and nH is the Hill coefficient. Individual concentration-response data collected from individual cells were analysed separately using the Hill equation to obtain the maximum current. Current was normalized to the maximum current to obtain the relative response at each agonist concentration and the data are plotted as a function of agonist concentration and analysed with eqn (2).

Materials

5-Nitro-2-(3-phenylpropylamino) benzoic acid (NPPB), 4,4′-diisothyocyanostilbene-2,2′-disulphonic disodium salt (DIDS), 4-[[4-formyl-5-hydroxy-6-methyl-3-[(phosphonooxy)methyl]-2-pyridinyl]azo]-1,3-benzenedisulphonic tetrasodium salt (PPADS) and guanosine 5′-O-(2-thiodiphosphate) trilithium salt (GDP-β-S) were purchased from Calbiochem; N-phenylanthranilic acid (DPC), adenosine 5′-triphosphate (Tris)2 or Na2 salts (Tris-, Na2-ATP), 2′- and 3′-O-(4-benzoylbenzoyl)adenosine 5′-triphosphate triethylammonium salt (Bz-ATP), 8,8’‘[carbonylbis[imino-3,1-phenylene carbonylimino(4-methyl-3,1-phenylene)carbonylimino]] bis-1,3,5-naphthalene trisulphonic acid hexa sodium salt (Suramin), Cibacron Blue 3GA, Brilliant Blue G, 1,9-dideoxyforskolin (DD-FKL) and all other reagents were obtained from Sigma.

RESULTS

Acinar cell Cl− currents

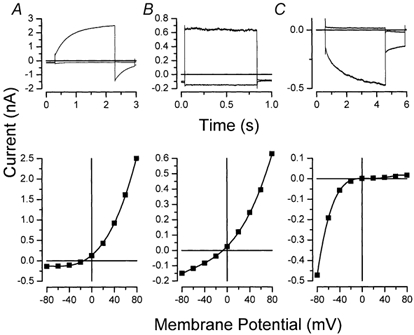

Mouse salivary gland acinar cells express multiple types of Cl− channels (Zeng et al. 1997b; Arreola et al. 2002a,b; Nehrke et al. 2002). Figure 1 summarizes the time course of these currents at +80 and −80 mV (upper row) and their corresponding I-V relationships (lower row). Currents are depicted from three different cells where distinct Cl− channels were activated selectively, as described below. Figure 1A shows the time course of the Cl− current flowing through Ca2+-dependent Cl− channels recorded from a cell dialysed with a pipette solution containing ≈250 nm free Ca2+. The characteristics of these channels include slow activation and a large inward tail current (Arreola et al. 2002b; and see Arreola et al. 1996a for a detailed characterization of this current). The corresponding I-V relationship for the Ca2+-dependent Cl− current is outwardly rectifying (bottom panel of Fig. 1A). Exposure of acinar cells to a hypotonic shock triggered the opening of a slightly outwardly rectifying Cl− channel (lower panel of Fig. 1B). In contrast to the Ca2+-dependent Cl− current, the upper panel of Fig. 1B reveals that the cell-swelling-activated current has little or no time dependence during 750 ms pulses. Figure 1C shows the current recorded from an acinar cell dialysed with 20 mm EGTA and zero Ca2+ and bathed in a hypertonic solution to minimize the Cl− current from the Ca2+-dependent and swelling-activated channels, respectively. Current at +80 mV was essentially absent, while the current at −80 mV displayed a slow time-dependent activation, indicative of the ClC-2 channel expressed in this cell type (Arreola et al. 2002a; Nehrke et al. 2002). The corresponding I-V relationship depicted in the bottom panel of Fig. 1C shows a channel with strong inward rectification (see Arreola et al. 2002a for a biophysical description of ClC-2 in mouse parotid acinar cells). The characteristics of these currents correspond well with the properties of the Ca2+-dependent, the volume-sensitive and the inwardly rectifying ClC-2 Cl− channels that have been described previously in both mouse and rat salivary acinar cells (Arreola et al. 1996b, 2002a, 2002b). In addition to these three Cl− channels, evidence for cAMP-dependent CFTR (Zeng et al. 1997b) and depolarization-activated ClC-3 (Arreola et al. 2002b) Cl− channels have also been documented; however, the functional characteristics of the putative intracellular ClC-3 channel have not been presented for salivary gland cells.

Figure 1. Cl− channels in mouse parotid acinar cells.

A, Ca2+-dependent Cl− channels. B, volume-sensitive Cl− channels. C, inward-rectifier Cl− channels. The data are representative of currents collected from three or more different cells for each condition. Upper row: currents obtained at +80 and −80 mV. Lower row: corresponding current-voltage relationships constructed with data obtained from +80 to −80 mV in 20 mV steps.

ATP-activated current

Some epithelial cells respond to external ATP by increasing their membrane conductance to different ions, including Cl− (Stutts et al. 1992; Schwiebert et al. 1995; Zeng et al. 1997a). In the following sections we demonstrate using the whole-cell patch-clamp technique that external ATP activated a novel Cl− channel in mouse parotid acinar cells. To analyse the voltage dependence of the ATP-activated conductance, the membrane potential was changed from −80 to +100 mV using 400 ms square pulses and ATP applied 5–6 min after achieving the whole-cell configuration. The ClC-2 current in mouse parotid acinar cells requires approximately 10 min of dialysis to develop. Thus, the combination of short pulses and ATP stimulation prior to the appearance of the hyperpolarization-activated current avoids nearly all of the time-dependent current due to ClC-2 channels (Fig. 1C). Figure 2A shows typical currents obtained from an individual acinar cell exposed to zero (left panel) and then 5 mm Tris-ATP (right panel). In the absence of ATP, whole-cell currents were quite small, 2.3 ± 0.3 pA pF−1 (n = 26) at +80 mV. However, the current activated by external ATP was large, typically about 10-fold larger than the current in unstimulated cells (Table 1), and displayed little or no time dependence at the voltages studied. The magnitudes and the activation kinetics of currents generated by Tris-ATP, Na2-ATP, and Mg-ATP were comparable (data not shown). Figure 2B shows the corresponding I-V relationship of the ATP-activated current normalized to cell capacitance (pA pF−1) and calculated as the current in the presence of ATP minus the current in the absence of ATP. The resulting I-V relationship exhibited slight outward rectification. The photosensitive analogue of ATP, Bz-ATP produced currents with similar kinetics (data not shown).

Table 1.

ATP-activated Cl− current (Iatpcl)

| Mice | Iatpcl (pApF−1) | n | [Ca2+]° (mM) |

|---|---|---|---|

| WT | 27.6 ± 3.4 | 11 | 0.5 |

| Clcn2−/- | 29.7 ± 4.0 | 10 | 0.5 |

| Cftr−/- | 24.9 ± 1.7 | 7 | 0.5 |

| Clcn3−/- | 21.1 ± 1.9 | 4 | 0.5 |

| WT or Cftr−/- (Ca2+ free) | 24.7 ± 3.5 | 5 | 0 |

| WT + GDP-β-S | 35.7 ±2.5 | 4 | 0.5 |

Whole-cell current activated by 5 mM Tris-ATP was recorded at +80 mV and normalized to cell capacitance. Current in the absence of ATP was subtracted. Experiments in zero Ca2+ were performed using a bath solution containing no Ca2+ plus 20 HIM EGTA. Cells dialysed with 2 mM GDP-β-S were allowed to stabilize for a period of 10 min before being exposed to 5 mM Tris-ATP. Data sets were not statistically different at P < 0.5. WT, wild-type.

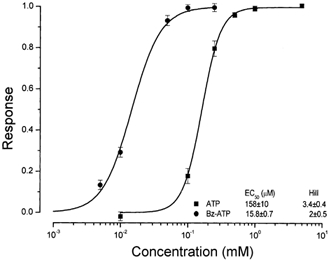

To define further the ATP dependence of the observed Cl− current, we determined the 50 % maximum response (EC50) and the Hill coefficient for Bz-ATP and Tris-ATP, as described in Methods. Figure 3 shows the resulting concentration-response curves obtained at +80 mV using 400 ms test pulses delivered every 5 s. Bz-ATP and Tris-ATP (n = 3 and n = 6, respectively) increased the Cl− current with a half-maximum concentration of 15.8 ± 0.7 and 158 ± 10 µm, respectively, and Hill coefficients of 2 ± 0.5 and 3.4 ± 0.4, respectively.

Figure 3. Concentration-response curves to Tris-ATP and Bz-ATP.

Currents were sampled at +80 mV at different agonist concentrations using 400 ms square pulses applied from 0 mV. Concentration-response curves obtained from single cells were normalized using the maximum current calculated by fitting the Hill equation. Normalized currents were then averaged, plotted as a function of agonist concentration and fitted with Hill eqn (2) (see Methods). EC50 and Hill coefficient values are given in the inset.

Anion dependence of the ATP-activated conductance

The results shown in Fig. 2 and Fig. 3 suggest that ATP activates a Cl− channel in mouse parotid acinar cells, as has been observed previously in submandibular salivary gland and airway epithelial cells (Stutts et al. 1992; Schwiebert et al. 1995; Zeng et al. 1997a). To test this possibility directly, we replaced Cl− in the external solution with equimolar glutamate. Figure 4A shows a representative recording at +80 mV in the presence of 5 mm Tris-ATP. The current rapidly reached steady state following exposure to ATP, and then the [Cl−]o was reduced from 140 to 1 mm. This manoeuvre resulted in a large, reversible reduction of the outward current from +0.51 to +0.16 nA. In similar experiments, the average reductions of the 5 mm Tris-ATP- and the 0.25 mm Bz-ATP-activated currents were 69.5 ± 2 % (n = 8) and 66.9 ± 5.5 % (n = 4), respectively, demonstrating that a significant fraction of the outward current was carried by Cl−. In addition to a current reduction, glutamate produced a positive shift in the reversal potential of 23.0 ± 5.0 mV (n = 4). Thus, external ATP activates an anion selective channel referred to hereafter as IATPCl.

Figure 4. Anion dependence of the ATP-activated current.

A, whole-cell current recorded at +80 mV. The current was activated by perfusing 5 mm Tris-ATP during the time indicated by the double-headed arrow. External Cl− was reduced from 140 to 1 mm by replacement with glutamate during the indicated time. ATP-activated current magnitude was reduced from +0.51 to +0.16 nA by decreasing the extracellular Cl− concentration. B, current-voltage relationships obtained from a single cell bathed in solutions containing 141 mmCl− (▪), 140 mm SCN− (•), 140 mm I− (▴), or 140 mm NO3− (▾). Current magnitudes were measured at the end of the 400 ms pulse using data like that depicted in Fig. 2B. Current-voltage curves were fitted with a third-order polynomial function (continuous lines) to calculate the reversal potentials (Er, inset).

To characterize the anion selectivity of IATPCl, I-V relationships were obtained in the presence of different anions in the external bath including SCN−, I−, NO3− and glutamate. Figure 4B shows examples of I-V relationships obtained from individual cells exposed to Cl−, SCN−, I− or NO3−. Current increased in the presence of external SCN−, I− and NO3− relative to those recorded at positive voltages in Cl−. Moreover, the reversal potential in the presence of external SCN−, I− and NO3− shifted in a negative direction relative to those in Cl−, consistent with a higher permeability to these anions. The selectivity sequence of the ATP-activated anion pathway based on permeability ratios (PX/PCl), estimated from the shift in the reversal potential (see eqn (1)), was SCN− (2.58 ± 0.17, n = 3) > I− (1.68 ± 0.1, n = 3) ≈ NO3− (1.55 ± 0.06, n = 3) > Cl− (1, n = 7) > glutamate (0.42 ± 0.07, n = 4). The same sequence is obtained from the absolute magnitude of the current recorded at positive voltages in the presence of each anion.

Identification of IATPCl

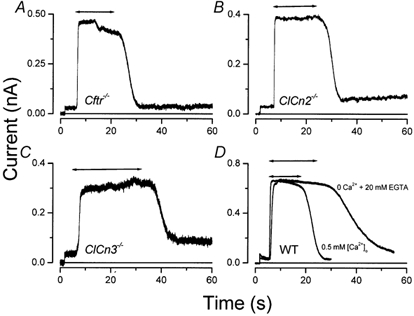

Mouse parotid acinar cells express at least five different Cl− channels, namely, Ca2+-activated, volume-sensitive, inward-rectifier ClC-2, cAMP-dependent CFTR and depolarising-activated ClC-3 Cl− channels. Experiments were designed to verify whether IATPCl is correlated with the gating of one of these channels. Accordingly, the IATPCl in parotid acinar cells isolated from mice with null mutations in either the Cftr, Clcn3 or Clcn2 genes (Snouwaert et al. 1992; Dickerson et al. 2002; Nehrke et al. 2002) were compared to cells from wild-type mice. Figure 5A and B shows that acinar cells lacking functional CFTR or ClC-2 respond to external ATP in a comparable fashion to cells isolated from wild-type animals (see Fig. 4). The magnitudes of the currents recorded at +80 mV were not statistically different from that obtained from wild-type cells (Table 1).

Figure 5. CFTR, ClC-2, ClC-3 and Ca2+-activated Cl− channels are not ATP-activated channels.

Currents were activated by applying 5 mm ATP during the times indicated by the double-headed arrows. The membrane potential was changed from 0 to +80 mV approximately 5 s prior to the addition of ATP. Currents were recorded from acinar cells isolated from Cftr-/- (A), Clcn2-/- (B), Clcn3-/- (C) and wild-type (WT, D) mice. Currents from the WT cell (D) were obtained from the same cell dialysed with 20 mm EGTA without Ca2+ and bathed in a solution containing 0.5 mm Ca2+ (0.5 mm [Ca2+]o) or 0 Ca2+ (0 Ca2++ 20 mm EGTA).

ClC-3b, a splice variant of ClC-3, is expressed highly in epithelial tissues, appears to facilitate the targeting of an outward-rectifier Cl− channel to the plasma membrane (Ogura et al. 2002) with functional characteristics similar to the outward-rectifier Cl− channel activated by external ATP in airway epithelial cells (Schwiebert et al. 1995). Since the electrophysiological properties of IATPCl are similar to these currents, we tested whether ClC-3 may be involved in the activation of IATPCl. Parotid acinar cells were isolated from Clcn3-/- mice, which have normal expression of Ca2+-dependent, volume-sensitive and inward-rectifier ClC-2 Cl− channels (Arreola et al. 2002b). Figure 5C demonstrates that the amplitude of the current activated by 5 mm Tris-ATP at +80 mV was very similar to that recorded from cells isolated from wild-type mice (Table 1).

To test for a role of Ca2+-dependent Cl− channels in the ATP response, we recorded IATPCl in the absence of intracellular and extracellular Ca2+ (20 mm EGTA, zero Ca2+). Figure 5D shows an example of the current obtained under these conditions. The magnitude of the response elicited by ATP in the absence of Ca2+ was nearly identical to that observed in the same cell in the presence of 0.5 mm extracellular Ca2+. However, the decay of the current measured following external ATP removal was considerably slower in the absence of Ca2+. The summary provided in Table 1 shows that the average currents induced by 5 mm ATP at +80 mV were not statistically different in cells isolated from wild-type, Cftr-/-, Clcn2-/- and Clcn3-/- mice, and in cells bathed in solutions containing 0 or 0.5 mm Ca2+.

These experiments were performed using hypertonic external solutions to produce cell shrinkage, and thus inhibit the cell-swelling-activated Cl− channel expressed in salivary acinar cells. Nevertheless, these results did not exclude the possibility that IATPCl may result from direct activation of the volume-sensitive channel by external ATP. This possibility was ruled out by using DD-FKL (100 µm), a known inhibitor of the volume-sensitive channel. Figure 6A shows that DD-FKL failed to block IATPCl under hypertonic experimental conditions. Moreover, Fig. 6B demonstrates that the current activated by ATP in a hypotonic solution persisted while the large outward current activated by cell swelling was blocked by DD-FKL. The magnitude of IATPCl in the presence of DD-FKL under hypotonic conditions (27.4 ± 5.9 pA pF−1 at +80 mV, n = 4) was similar to that observed under hypertonic control conditions (20.5 ± 3.9 pA pF−1 at +80 mV, n = 5). These results indicate that the volume-sensitive current is separate from IATPCl. Insets in Fig. 6 show examples of the current recorded at various times during the experiment.

Figure 6. Volume-activated Cl− channels are not involved in the ATP-activated current.

A, whole-cell currents at +80 mV were sampled every 5 s from a cell bathed in a hypertonic medium (370 mmol kg−1). 1,9-dideoxyforskolin (0.1 mm DD-FKL) was applied 45 s before perfusing with 5 mm Tris-ATP. B, whole-cell currents were measured every 5 s using a 40 ms test pulse to +80 mV from a holding potential of 0 mV. Volume-activated channels were activated by decreasing the bath tonicity from 370 to 240 mmol kg−1 during the indicated time. DD-FKL (0.1 mm) was applied to inhibit the volume-sensitive current and then 5 mm Tris-ATP was added at the indicated times. Insets: whole-cell currents obtained at the time indicated by the corresponding numbers in the main figure.

Pharmacology of IATPCl

The sensitivity of IATPCl to different classes of Cl− channel blockers was examined subsequently to further characterize the properties of what appeared to be a novel channel. In contrast to the inhibitory effects of these agents on the Cl− channels described previously in salivary acinar cells, all of the antagonists tested were ineffective in blocking IATPCl (Table 2). The compounds tested included the CFTR blocker glybenclamide (Sheppard & Welsh, 1993), the blocker of both volume-sensitive and Ca2+-dependent Cl− channels DD-FKL (Nilius et al. 1997; Melvin et al. 2002), and the Cl− channel blockers DIDS, DPC, and NPPB (Greger, 1983; Nilius et al. 1997), which non-selectively inhibit most types of Cl− channels. DIDS and NPPB blocked both the short-circuit current and the single Cl− channel activated by ATP in airway epithelial cells (Stutts et al. 1992; Schwiebert et al. 1995), whilst glybenclamide and DPC blocked the ATP-activated current and the Cl− loss induced by external ATP in submandibular duct and acinar cells (Zeng et al. 1997a). The lack of effect of these blocking agents on the current activated by external ATP provides further evidence that neither CFTR, Ca2+-dependent, volume-sensitive nor voltage-dependent ClC-2 and ClC-3 Cl− channels are involved, but instead, IATPCl represents a novel Cl− channel in mouse parotid acinar cells.

Table 2.

Pharmacology of Iatpcl

| Concentration | Iatpcl (pApF−1) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Drug | (mM) | Preinhibition | +Inhibitor | n |

| NPPB | 0.1 | 26.6 ± 1.4 | 27.4 ± 1.0 | 3 |

| DIDS | 5 | 13.9 ± 2.3 | 13.5 ± 12.1 | 5 |

| DPC | 1 | 28.9 ± 3.5 | 43.6 ± 8.9 | 3 |

| Glybenclamide | 0.1 | 38.8 ± 2.0 | 52.5 ± 7.7 | 4 |

| Cibacron Blue 3A | 0.5 | 19.3 ± 3.0 | 18.4 ± 2.6 | 6 |

Whole-cell currents activated by 5 HIM Tris-ATP at +80 mV were sampled before (Preinhibition) and after (+Inhibitor) adding the indicated blocker. Current in the absence of ATP was subtracted before normalizing the current magnitude to cell capacitance. NPPB, 5-nitro-2-(3-phenylpropylamino) benzoic acid; DIDS, 4,4′-diisothyocyanostilbene-2,2′-disulphonic disodium salt; DPC,N-phenylanthranilic acid.

P2 nucleotide receptors apparently mediate the activation of the outward-rectifier Cl− channel by external ATP in airway epithelial cells (Stutts et al. 1992; Schwiebert et al. 1995). Although the precise mechanism underlying this effect is unknown, one possibility is that ATP acts through a G-protein-coupled P2Y receptor. P2Y receptors are present in parotid acinar cells (Turner et al. 1999) and the signalling cascade triggered by its activation could serve to activate IATPCl. To test this possibility, acinar cells were dialysed for 10 min with 2 mm GDP-β-S to quench G-protein subunits, thus stopping downstream events. This approach has been used extensively in different cell types to block intracellular events triggered by activation of G-protein-coupled receptors (Burch & Axelrod, 1987; Eberhard & Holz, 1991; Nakagawa et al. 1991; Wadman et al. 1991; Berve et al. 1994). In rat parotid acinar cells, 5–6 min dialysis of 2 mm GDP-β-S was used to block the effects of external ATP (Zeng et al. 1997a). Table 1 shows that the dialysis of GDP-β-S failed to uncouple ATP-induced current activation. These results indicate that a G-protein-linked nucleotide receptor is not likely to be involved in generating IATPCl. The current magnitude recorded at +80 mV from cells dialysed with GDP-β-S was 35.7 ± 2.5 pA pF−1 (n = 4), which is comparable to that seen in control cells.

Bz-ATP, an agonist used typically to activate cation-selective P2X7 receptor channels (North, 2002), also activated a Cl− conductance in mouse parotid acinar cells with characteristics similar to that activated by Tris-ATP (Fig. 3). Thus, another mechanism through which external ATP may act is by stimulating a P2X7 receptor channel that subsequently activates IATPCl. To evaluate further the role of purinergic receptors in the generation of IATPCl, we determined the effects of different classes of P2 nucleotide receptor antagonists (North, 2002) on ATP-activated Na+ and Cl− currents. Brilliant Blue G (0.01 mm; n = 5), PPADS (0.5 mm, n = 4), and Suramin (5 mm, n = 5) were without effect on IATPCl or the Na+ current activated by ATP (data not shown). However, Cibacron Blue 3GA, a P2 nucleotide receptor antagonist shown previously to block the increase in the intracellular [Ca2+] induced by ATP in rat parotid acinar cells (McMillian et al. 1993), almost completely blocked the ATP-activated Na+ current. Figure 7A shows an example of the I-V relationships obtained from an individual cell in either the absence (squares) or in the presence (circles) of 0.5 mm Cibacron Blue. At +80 mV, Cibacron Blue inhibited 92.6 ± 3.8 % (n = 5) of the Na+ current. A comparable degree of block was observed at −80 mV. Figure 7B shows that the same concentration of Cibacron Blue 3GA was without significant effect on IATPCl (See also Table 2). Insets in Fig. 7A and B are examples of currents recorded at +80 mV to illustrate the effect of Cibacron Blue on the ATP-induced Na+ current (IATPNa) and IATPCl, respectively. Currents observed in the absence of ATP (smaller current), in the presence of ATP (larger currents) and in the presence of ATP + Cibacron Blue (indicated by the arrows) are shown. Of the other nucleotide receptor antagonists used, only 5 mm DIDS partially blocked the ATP-activated Na+ current (at +80 mV, 41.5 ± 6.3 %, n = 4). Moreover, like Cibacron Blue 3GA, DIDS had no significant effect on IATPCl (Table 2). Taken together, the differential sensitivity of the ATP-activated Na+ and Cl− currents to Cibacron Blue and DIDS, as well as the lack of sensitivity to known Cl− channel blockers, demonstrate that IATPCl is not associated with the P2 nucleotide receptor channels or Cl− channels described previously in salivary acinar cells, but represents a novel Cl− channel.

Figure 7. Effects of Cibacron Blue 3GA on the ATP-activated Na+ and Cl− currents.

A, current-voltage relationship of the ATP-activated Na+ current in the absence (▪) and presence (•) of 0.5 mm Cibacron Blue. B, current-voltage relationship of the ATP-activated Cl− current in the absence (▪) and presence (•) of 0.5 mm Cibacron Blue. Insets: whole-cell currents obtained at +80 mV in the absence of ATP (control, smallest currents), in the presence of ATP (largest currents), and in the presence of ATP + Cibacron Blue (indicated by the arrows). Na+ currents were recorded from cells dialysed and bathed with solutions containing Na-glutamate. Cl− currents were recorded from cells dialysed and bathed with solutions containing TEA-Cl.

DISCUSSION

Salivary gland fluid secretion is linked primarily to muscarinic receptors, activation of which mobilizes intracellular Ca2+ by releasing intracellular stores and by activating Ca2+ influx (Cook et al. 1994). The resulting rise in the intracellular Ca2+ concentration stimulates transepithelial Cl− movement, the driving force for salivation. Cl− channels located in the apical membrane of acinar cells provide the Cl− efflux pathway necessary for fluid secretion, although the molecular identity of this (these) channel(s) remains unknown. The Ca2+ dependency of fluid secretion (Douglas & Poisner, 1963) argues that the Ca2+-activated Cl− channel expressed in acinar cells plays a central role in the process; however, the rundown of the Ca2+-activated Cl− current monitored in whole-cell patch-clamp experiments is incompatible with this secretion model (Nishiyama & Petersen, 1974; Iwatsuki et al. 1985; Sasaki & Gallagher, 1990). It is not clear whether the decay of the current is an intrinsic property of the Ca2+-activated Cl− channel or is an artefact of the whole-cell patch-clamp method. Under what is likely a more physiological condition, low concentrations of the agonist acetylcholine induce an oscillatory Cl− current, the magnitude of which remains relatively constant for up to 10–15 min (Smith & Gallacher, 1992). Regardless of the kinetic properties of the Ca2+-activated Cl− current, the expression of multiple classes of Cl− channels in salivary acinar cells (Arreola et al. 1996b; Zeng et al. 1997; Begenisich & Melvin, 1998; Melvin, 1999) has made it difficult to assign functions to an individual Cl− channel. Targeted gene disruptions of individual Cl− channel genes have provided little insight into the fluid secretion process (Arreola et al. 2002b; Nehrke et al. 2002; H.-V. Nguyen, unpublished observations), except to imply that acinar cells may express an additional, unknown Cl− channel. Here we show that external ATP gates a novel Cl− conductance whose properties are distinct from the Cl− channels described previously in salivary gland acinar cells. The characteristics of IATPCl are consistent with this channel playing a potentially important physiological role in salivary gland fluid secretion.

The IATPcl in parotid acinar cells did not require Ca2+ and was insensitive to changes in cell volume as well as all Cl− channel inhibitors tested. In addition, the IATPCl was of similar magnitude in mice lacking expression of the ClC-2 Cl− channel to the Cl− current expressed in wild-type cells. These results demonstrate clearly that IATPCl is distinct from the Ca2+-dependent, volume-sensitive and inward rectifier ClC-2 Cl− currents described previously in this cell type (Arreola et al. 1996b; Zeng et al. 1997; Nehrke et al. 2002). A summary of the unique properties of the different Cl− currents expressed in salivary gland acinar cells is provided for comparison in Table 3 (for detailed discussions see Begenisich & Melvin, 1998; Melvin et al. 2002. See also Jentsch et al. 2002, for a summary on pharmacological properties of different anion channels).

Table 3.

Properties of Cl− channel currents in salivary gland cells

| Iatpcl | ClC-2 | CFTR | Volume sensitive | Ca2+ activated | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Properties | |||||

| I-V relationship | Slightly outward | Strongly inward | Linear | Slightly outward | Outward, dependent on the [Ca2+]i |

| Kinetics | Instantaneous, slow decay at negative Vm | Slow, biexponential activation | Instantaneous | Instantaneous, slow decay at positive Vm | Slow, monoexponential activation |

| Anion selectivity | SCN− > I− = NO3− > Cr > glutamate | I− =Cl− = Br− | NO3− > I− = Br− > Cl− | SCN− > I− = NO3− > Br− > Cl− > glutamate | SCN− > I− = NO3− > Br− > Cl− > glutamate |

| Pharmacology | |||||

| DIDS | − | − | − | − | + |

| NPPB | − | − | + | + | − |

| DD−FKL | − | − | − | + | + |

| DPC | − | − | + | + | + |

| Glybenclamide | − | ? | + | ? | − |

Vm, membrane potential.

The I-V relationship and activation kinetics of IATPCl in parotid acinar cells resemble the ORCC found in airway epithelia (Schwiebert et al. 1995). However, unlike the IATPCl in parotid acinar cells, the channel regulated by ATP in airway cells is DIDS-sensitive. IATPCl was insensitive to DIDS at concentrations as high as 5 mm and was also insensitive to other Cl− channel blockers (NPPB and DPC) known to inhibit ORCC (Table 2). Therefore, the pharmacology of IATPCl is unique compared to the ORCC as well as the other anion channels described previously in salivary acinar cells (Arreola et al. 1996b; Begenisich & Melvin, 1998; Melvin, 1999; Melvin et al. 2002). Recent evidence shows that ClC-3b appears to facilitate expression of the CFTR-regulated ORCC (Ogura et al. 2002). ClC-3b is a splice variant of the ClC-3 Cl− channel expressed in endosomes and synaptic vesicles that does not mediate the swelling-activated Cl− current (Stobrawa et al. 2001; Arreola et al. 2002b; Dickerson et al. 2002). In airway epithelial cells expressing the cAMP-activated CFTR channel, external ATP increases the open probability of ORCC recorded from outside-out patches (Stutts et al. 1992). However, in the present study, the ATP-activated Cl− current obtained from Clcn3-/- mouse parotid acinar cells was comparable to that observed in wild-type animals, indicating that neither ClC-3 nor its 3b splice variant is required for the expression of IATPCl. IATPCl also had kinetic properties similar to the outwardly rectifying, cell-swelling-activated Cl− current in salivary acinar cells (Arreola et al. 1996b; Zeng et al. 1997), but inhibitors that block this latter current failed to antagonize IATPCl. Thus, based on pharmacological evidence and on data from the Clcn3-/- mice, we conclude that IATPCl is not ORCC or the swelling-activated Cl− channel.

The mechanism by which external ATP enhances channel activity in epithelial cells remains obscure. In one theory, a coordinated activation by ATP of a protein cluster that includes CFTR, a P2 nucleotide receptor and an outwardly rectifying Cl− channel, results in an increase in the Cl− conductance (Schwiebert et al. 1995). This model predicts that activation of CFTR increases the permeability of the cell to ATP; the resulting increase in extracellular ATP activates nearby P2 nucleotide receptors. Depending on the type of receptor involved, stimulation may activate G-proteins (through P2Y receptors) to directly modulate the activity of the outward-rectifier Cl− channel. This was not the case here because GDP-β-S failed to inhibit activation of the ATP-dependent Cl− current. Alternatively, P2 nucleotide receptor stimulation may increase the Ca2+ permeability of epithelial cells, mediated by either ionotropic (P2X) or G-protein-coupled (P2Y) receptors. Regardless of the mechanism involved, the ensuing rise in the intracellular [Ca2+] enhances the Cl− permeability in rat submandibular gland cells by activating Ca2+-dependent Cl− channels (Arreola et al. 1996a; Zeng et al. 1997a). Nevertheless, we found that ATP activated a Cl− current in the absence of intracellular and extracellular Ca2+ (Fig. 5D). Depletion of extracellular Ca2+ dramatically slowed the time course for decay of the current following the removal of ATP. The mechanism underlying this affect is unknown, but one could speculate that extracellular Ca2+ regulates the interaction of ATP with its binding site. It also appears in submandibular cells that extracellular ATP can activate a Ca2+-independent Cl− channel, the identity of which may be CFTR based on its sensitivity to glybenclamide (Zeng et al. 1997a). However, IATPCl in parotid acinar cells was insensitive to glybenclamide (Table 2) and did not display a linear I-V relationship like CFTR. Most significantly, the amplitude of the ATP-activated current in Cftr-/- mice was comparable to the current seen in wild-type mice, confirming that IATPCl does not represent CFTR expression in mouse parotid acinar cells.

All P2X receptors are permeable to small monovalent cations, but some have considerable permeability to larger cations under some conditions. For example, rat P2X7 receptors expressed in human embryonic kidney 293 cells displayed less selectivity when stimulation with ATP was prolonged resulting in increased permeability to large ions like TEA (Virginio et al. 1999), which was present in our internal and external recording solutions. Because much of the current disappeared when we replaced Cl− with glutamate, TEA did not contribute significantly to the recorded ATP-activated current. Thus, the simplest interpretation of our results is that the ATP-activated Cl− conductance in parotid acinar cells is not due to the expression of any of the previously described channels in this cell type, but represents a novel Cl− channel. This is further supported by the shifts of reversal potentials induced by replacing external Cl− with other anions. The permeability sequence of IATPCl (SCN− > I−≈ NO3− > Cl− > glutamate) is quite similar to that determined for volume-sensitive and Ca2+-dependent Cl− channels in parotid acinar cells (See Table 3 for comparison). This sequence corresponds to sequence 1 of Wright & Diamond (1977), suggesting the presence of a weak binding site for anions, a prediction based on anion hydration energies and the charge and radii of the binding site. Alternatively, IATPCl may directly reflect the activation of a Cl−-permeable nucleotide receptor. However, the purinergic receptor antagonist Cibacron Blue 3GA abolished the ATP-activated Na+ conductance in acinar cells with little or no effect on IATPCl. Similarly, DIDS partially inhibited the ATP-activated Na+ conductance without significantly altering the Cl− conductance. Like Cibacron Blue 3GA, the mechanism by which DIDS likely inhibits the ATP-activated Na+ current is by blocking ATP binding to the P2 nucleotide receptor (McMillan et al. 1993). The differential effects of Cibacron Blue 3GA and DIDS demonstrates the presence of two different ATP-activated conductances in parotid acinar cells. The Na+ conductance requires the activation of nucleotide receptors by external ATP, whereas ATP activates a Cl− conductance independent of nucleotide receptors.

In summary, we have shown that external ATP increases the conductance to both Na+ and Cl− in parotid acinar cells through independent mechanisms. Importantly, pharmacological profiles can be used to differentiate the Na+ and Cl− conductances, indicating that ATP does not act through a purinergic receptor to activate the Cl− conductance. The unique activation kinetics and pharmacology of IATPCl demonstrate that this current represents a novel Cl− channel (see Table 3). Our results and those of others (Stutts et al. 1992; Schwiebert et al. 1995; Lee et al. 1997; Zeng et al. 1997a) indicate that ATP may regulate multiple steps of the fluid secretion mechanism. Although the source of ATP and the mechanism for its release have not been identified in salivary glands, it is likely that muscarinic stimulation releases ATP, as has been shown to occur in pancreatic acinar cells (Sorensen & Novak, 2001). In the pancreas, ATP is released from acinar cells into the lumen to act distally on the apical membranes of duct cells. Our results indicate that in parotid glands, extracellular ATP would act on both acinar and duct cells. Acinar cells produce isotonic, NaCl-rich primary saliva, which is generated by transepithelial Cl− movement. Activation of a Cl− current in the apical membranes of acinar cells by ATP would enhance this process and increase the volume of saliva produced. Duct cells subsequently modify these secretions through NaCl reabsorption and K+ secretion mechanisms. Modulation of these processes by external ATP is expected to alter the ionic composition of the ductal fluid by increasing the Na+ and Cl− reabsorption resulting from the activation of the P2 nucleotide receptors known to be present on duct cells (Lee et al. 1997; Zeng et al. 1997). Further examination of the properties of this unique ATP-gated Cl− channel will likely provide valuable insight into the mechanism underlying salivation.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr Ted Begenisich for a critical reading of the manuscript and Jodi Pilato and Idalia Alanis for excellent technical assistance. This work was supported in part by NIH grants DE09692 and DE13539 (JEM).

REFERENCES

- Arreola J, Begenisich T, Melvin JE. Conformation-dependent regulation of inward rectifier Cl− channel gating by extracellular protons. J Physiol. 2002a;541:103–112. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2002.016485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arreola J, Begenisich T, Nehrke K, Nguyen H-V, Park K, Richardson L, Yang B, Lamb F, Schutte BC, Melvin JE. Normal secretion and cell volume regulation by salivary gland acinar cells from mice lacking expression of the Clc3 Cl− channel gene. J Physiol. 2002b;545:207–216. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2002.021980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arreola J, Melvin JE, Begenisich T. Activation of calcium-dependent chloride channels in rat parotid acinar cells. J Gen Physiol. 1996a;108:35–47. doi: 10.1085/jgp.108.1.35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arreola J, Park K, Melvin JE, Begenisich T. Three distinct chloride channels control anion movements in rat parotid acinar cells. J Physiol. 1996b;490:351–362. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1996.sp021149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Begenisich T, Melvin JE. Regulation of chloride channels in secretory epithelia. J Memb Biol. 1998;163:77–85. doi: 10.1007/s002329900372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berve LA, Hughes BP, Barritt GJ. A slowly ADP-ribosylated pertussis-toxin-sensitive GTP-binding regulatory protein is required for vasopressin-stimulated Ca2+ inflow in hepatocytes. Biochem J. 1994;299:399–407. doi: 10.1042/bj2990399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burch RM, Axelrod J. Dissociation of bradykinin-induced prostaglandin formation from phosphatidylinositol turnover in Swiss 3T3 fibroblasts: Evidence for G protein regulation of phospholipase A2. Proc Nat Acad Sci USA. 1987;84:6374–6378. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.18.6374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook DI, Van Lennep EW, Roberts ML, Young JA. Secretion by the major salivary glands. In: Johnson LR, editor. Physiology of the Gastrointestinal Tract. 3. NY: Raven Press; 1994. pp. 1061–1117. [Google Scholar]

- Dickerson LW, Schutte BC, Yang B, Bonthius DJ, Barna TJ, Bailey MC, Nehrke K, Williamson RA, Lamb FS. Altered GABAergic function accompanies hippocampal degeneration in mice lacking ClC-3 voltage-gated chloride channels. Brain Res. 2002;958:227–250. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(02)03519-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Douglas WW, Poisner AM. The influence of calcium on the secretory response of the submaxillary gland to acetylcholine or to noradrenaline. J Physiol. 1963;165:528–541. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1963.sp007076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eberhard DA, Holz RW. Regulation of the formation of inositol phosphates by calcium, guanine nucleotides and ATP in digitonin-permeabilized bovine adrenal chromaffin cells. Biochem J. 1991;279:447–453. doi: 10.1042/bj2790447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greger R. Chloride channel blockers. Meth Enzymol. 1983;191:793–810. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(90)91048-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamill OP, Marty A, Neher E, Sakman B, Sigworth F. Improved patch-clamp techniques for high-resolution current recording from cells and cell-free membrane patches. Pflugers Archiv. 1981;391:85–100. doi: 10.1007/BF00656997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwatsuki N, Maruyama Y, Matsumoto O, Nishiyama A. Activation of Ca2+-dependent Cl− and K+ conductances in rat and mouse parotid acinar cells. Jap J Physiol. 1985;35:933–944. doi: 10.2170/jjphysiol.35.933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jentsch TJ, Stein V, Weinreich F, Zdebik AA. Molecular structure and physiological function of chloride channels. Physiol Rev. 2002;82:503–568. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00029.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee MG, Zeng W, Muallem S. Characterization and localization of P2 receptors in rat submandibular gland acinar and duct cells. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:32951–32955. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.52.32951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McMillian MK, Soltoff SP, Cantley LC, Rudel RA, Talamo BR. Two distinct cytosolic calcium responses to extracellular ATP in rat parotid acinar cells. British J Pharmacol. 1993;108:453–461. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1993.tb12825.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin DK. Small conductance chloride channels in acinar cells from the rat mandibular salivary gland are directly controlled by a G{nbh}protein. Biochem Biophys Res Comm. 1993;192:1266–1273. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1993.1553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melvin JE. Chloride channels in salivary gland function. Crit Rev Oral Biol Med. 1999;10:199–209. doi: 10.1177/10454411990100020601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melvin JE, Arreola J, Nehrke K, Begenisich B. Ca2+-activated Cl− currents in salivary and lacrimal glands. Cur Top Memb. 2002;53:209–230. [Google Scholar]

- Nakagawa Y, Gammichia J, Purushotham KR, Schneyer CA, Humphreys-beher MG. Epidermal growth factor activation of rat parotid gland adenylate cyclase and mediation by a GTP-binding regulatory protein. Biochem Pharmacol. 1991;42:2333–2340. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(91)90238-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nehrke K, Arreola J, Nguyen H-V, Pilato J, Richardson L, Okunade G, Baggs R, Shull GE, Melvin JE. Loss of hyperpolarization-activated Cl− current in salivary acinar cells from Clcn2 knockout mice. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:23604–23611. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M202900200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nilius B, Eggermont J, Voets T, Buyse G, Manolopoulos V, Droogmans G. Properties of volume-regulated anion channels in mammalian cells. Prog Biophys Mol Biol. 1997;68:69–119. doi: 10.1016/s0079-6107(97)00021-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishiyama A, Petersen OH. Membrane potential and resistance measurement in acinar cells from salivary glands in vitro: effect of acetylcholine. J Physiol. 1974;242:173–188. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1974.sp010700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- North RA. Molecular physiology of P2X receptors. Phys Rev. 2002;82:1013–1067. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00015.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogura T, Furukawa T, Toyozaki T, Yamada K, Zheng Y-J, Katayama Y, Nakaya H, Inagaki N. ClC-3B, a novel ClC-3 splicing variant that interacts with EBP50 and facilitates expression of CFTR-regulated ORCC. FASEB J. 2002;16:863–865. doi: 10.1096/fj.01-0845fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park M, Garrad RC, Weisman GA, Turner JT. Changes in P2Y1 nucleotide receptor activity during the development of rat salivary glands. Am J Physiol. 1997;272:C1388–C1393. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1997.272.4.C1388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quinton PM. Chloride impermeability in cystic fibrosis. Nature. 1983;301:421–422. doi: 10.1038/301421a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sasaki T, Gallacher DV. Extracellular ATP activates receptor-operated cation channels in mouse lacrimal acinar cells to promote calcium influx in the absence of phosphoinositide metabolism. FEBS Let. 1990;264:130–134. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(90)80782-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwiebert EM, Egan ME, Hwang TH, Fulmer SB, Allen SS, Cutting GR, Guggino WB. CFTR regulates outwardly rectifying chloride channels through an autocrine mechanism involving ATP. Cell. 1995;81:1063–1073. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(05)80011-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheppard D, Welsh M. Inhibition of the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator by ATP-sensitive potassium channel regulators. Ann New York Acad Sci. 1993;707:275–284. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1993.tb38058.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith PM, Gallacher DV. Acetylcholine- and caffeine-evoked repetitive transient Ca2+-activated K+ and C1− currents in mouse submandibular cells. J Physiol. 1992;449:109–120. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1992.sp019077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snouwaert JN, Brigman KK, Latour AM, Malouf NN, Boucher RC, Smithies O, Koller BH. An animal model for cystic fibrosis made by gene targeting. Science. 1992;257:1083–1088. doi: 10.1126/science.257.5073.1083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sorensen CE, Novak I. Visualization of ATP release in pancreatic acini in response to cholinergic stimulus: Use of fluorescent probes and confocal microscopy. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:32925–32932. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M103313200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stobrawa SM, Breiderhoff T, Takamori S, Engel D, Schweizer M, Zdebik AA, Bosl MR, Ruether K, Jahn H, Draguhn A, Jahn R, Jentsch TJ. Disruption of ClC-3, a chloride channel expressed on synaptic vesicles, leads to a loss of the hippocampus. Neuron. 2001;29:185–196. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(01)00189-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stutts MJ, Chinet TC, Mason SJ, Fullton JM, Clarke LL, Boucher RC. Regulation of Cl− channels in normal and cystic fibrosis airway epithelial cells by extracellular ATP. Proc Nat Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:1621–1625. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.5.1621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tenneti L, Gibbons SJ, Talamo B. Expression and trans-synaptic regulation of P2X4 and P2z receptors for extracellular ATP in parotid acinar cells. Effects of parasympathetic denervation. J Biol Chem. 1998;272:26799–26808. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.41.26799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner JT, London LA, Gibbons SJ, Talamo BR. Salivary gland P2 nucleotide receptors. Crit Rev Oral Biol Med. 1999;10:210–224. doi: 10.1177/10454411990100020701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner JT, Weisman GA, Camden JM. Up-regulation of P2Y2 nucleotide receptors in rat salivary gland cells during short-term culture. Am J Physiol. 1997;273:C1100–C1107. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1997.273.3.C1100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Virginio C, Mackenzie A, North RA, Surprenant A. Kinetics of cell lysis, dye uptake and permeability changes in cells expressing the rat P2X7 receptor. J Physiol. 1999;519:335–346. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1999.0335m.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wadman IA, Farndale RW, Martin BR. Evidence for regulation of human platelet adenylate cyclase by phosphorylation. Inhibition by ATP and guanosine 5′-[beta-thio]diphosphate occur by distinct mechanisms. Biochem J. 1991;276:621–630. doi: 10.1042/bj2760621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wright EM, Diamond JM. Anion selectivity in biological systems. Physiol Rev. 1977;57:109–156. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1977.57.1.109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeng W, Lee MG, Muallem S. Membrane-specific regulation of Cl− channels by purinergic receptors in rat submandibular gland acinar and duct cells. J Biol Chem. 1997a;272:32956–32965. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.52.32956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeng W, Lee MG, Yan M, Diaz J, Benjamin I, Marino CR, Kopito R, Freedman S, Cotton K, Muallem S, Thomas P. Immuno and functional characterization of CFTR in submandibular and pancreatic acinar and duct cells. Am J Physiol. 1997b;273:C442–C455. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1997.273.2.C442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]