Abstract

Dietary protein restriction during gestation has been shown to produce vascular dysfunction in pregnant rats and hypertension in their offspring. However, no studies have to date examined the effects of such ‘programming’ on the vascular function of female offspring when they in turn become pregnant. We have therefore studied isolated conduit and resistance artery function from pregnant female offspring of control (C, 18 % casein) and protein-restricted (PR, 9 % casein) pregnant dams. There were no differences in birth weight, weight gain during pregnancy, litter size, fetal weight, placental weight, fetal : placental weight ratio or organ weights between the C and PR groups. In isolated mesenteric arteries, the vasodilatation in response to the endothelial-dependent vasodilator acetylcholine (ACh) and the β-adrenoceptor agonist isoprenaline was decreased in the PR group, while there were no differences in the constriction in response to potassium (125 mm) or the α1-adrenoceptor agonist phenylephrine (PE). No differences in any responses were seen in the isolated thoracic aorta. We conclude that dietary protein restriction in pregnancy programmes vasodilator dysfunction in isolated resistance arteries of female offspring when they become pregnant, but does not affect conduit arteries.

Epidemiological evidence has shown a link between low birth weight and an increased risk of cardiovascular disease in later life (Barker, 1992, 1995). The concept of fetal ‘programming’ of disease is supported by animal models, which have shown that the restriction of dietary protein, or a global restriction in nutrients, during pregnancy gives rise to offspring with glucose intolerance (Dahri et al. 1991; Langley et al. 1994), insulin resistance (Dahri et al. 1991), elevated blood pressure (Langley & Jackson, 1994; Ozaki et al. 2001) and vascular dysfunction (Holemans et al. 1999; Brawley et al. 2002a).

Pregnancy is associated with an increase in maternal plasma volume (Rosso & Streeter, 1979) and cardiac output (Ahokas et al. 1983). In conditions of malnourishment, these increases are blunted (Rosso & Kava, 198) and are associated with a reduced uteroplacental blood flow (Ahokas et al. 1983, 1984) and decreased heart rate (Ahokas et al. 1984). Pregnancy is also associated with a decrease in peripheral resistance, mediated by an increased release of nitric oxide (NO), prostacyclin (PGI2) and endothelium-derived hyperpolarizing factor (EDHF) in peripheral vessels (Nathan et al. 1995; Poston et al. 1995; Gerber et al. 1998). A reduction in these vasodilators may lead to pregnancy and/or fetal complications.

A functional vascular endothelium is important in the control of vascular tone (Vanhoutte, 1989), and endothelial dysfunction has been reported in hypertensive patients (Panza et al. 1993; Taddei et al. 1993) and patients with type 2 diabetes (McVeigh et al. 1992; Yu et al. 2001). Impaired vasodilatation in response to ACh and isoprenaline occurs in hypertensive rats (Sunano et al. 1999; Goto et al. 2001) as well as in humans (Gros et al. 1997; Paniagua et al. 2000). Moreover, an impairment of ACh- and isoprenaline-induced vasodilatation has also been shown to precede the onset of hypertension in rats (Fu-Xiang et al. 1992; Goto et al. 2001) and may therefore be important in the development of vascular disease.

We have previously shown that restriction of dietary protein to rat dams throughout pregnancy results in a reduced endothelial-dependent vasodilatation in small mesenteric arteries (Koumentaki et al. 2002) and an attenuated response to vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) in uterine arteries (Itoh et al. 2002). We have also reported that the male offspring of protein-restricted dams exhibit impaired vasodilator responses, which are both endothelium dependent and independent (Brawley et al. 2002a). We have now extended this study to the female offspring and, in particular, to the pregnancy of these offspring. Therefore, the aim of this study was to assess the effect of maternal protein restriction during pregnancy on the female offspring when they in turn become pregnant, but in the absence of any further nutritional challenge. Preliminary results from this study have been presented (Barker et al. 2002b; Torrens et al. 2002b).

METHODS

All animal procedures carried out in this study were in accordance with the regulations of the Animals (Scientific Procedures) Act 1986 and this study was approved by the University of Southampton local ethical review committee.

Dietary protocol

Virgin female Wistar rats (supplied by Harlan, UK) weighing approximately 190–220 g were mated with stud males. Conception was confirmed by the presence of a vaginal plug. Once pregnant, animals were fed either a control (C; 18 % casein) or a protein-restricted diet (PR; 9 % casein) through to delivery. The experimental diet constituents were as previously described by Itoh et al. (2002). Mother and pups were returned to standard laboratory chow postpartum.

Pups were weighed 48 h after birth (to avoid rejection) and litters were culled to eight by cervical dislocation, with equal male and female offspring where possible. The offspring were weighed every 2 days until they were 63 days of age, and were weaned from their mothers at 25 days of age and then separated into male and female cages.

Mature female offspring, approximately 125 days of age, were mated and conception was confirmed by vaginal plug. The weights of the dams were recorded before mating. Pregnant dams were continued on the standard laboratory chow until day 19 of gestation, when they were reweighed and killed by CO2 inhalation and cervical dislocation. After killing, the myometrium, heart, lung, liver, kidneys, adrenal glands and pancreas were removed and weighed. The mesenteric arcade and thoracic aorta were removed for isolated vascular studies.

Fetal and placental observations

The myometrium of each dam was removed postmortem and placed in cold physiological salt solution (PSS, mm: NaCl 119, KCl 4.7, CaCl2 2, MgSO4 1.17, NaHCO3 25, KH2PO4 1.18, EDTA 0.026 and glucose 5). The litter size of each dam was noted and each fetus and its placenta were individually weighed.

Assessment of vascular function

Conduit arteries

The thoracic aorta was dissected clean of connective tissue and mounted as arterial ring segments in an organ bath (Linton Systems). The segments were bathed in PSS, heated to 37 °C, continuously gassed with 95 % O2-5 % CO2, stretched to an optimal resting tension equal to 3 g and allowed to equilibrate for 1 h. Functional integrity was tested by the addition of 125 mm KPSS solution (PSS with an equimolar substitution of KCl for NaCl). Concentration-response curves (CRCs) for KCl (5.88–125.88 mm) and the α1-adrenoceptor agonist phenylephrine (PE; 10 nm to 100 µm) were carried out. Vessels were preconstricted with PE to approximately 80 % of the maximal response (EC80) and cumulative CRCs in response to ACh (1 nm to 100 µm) and the β-adrenoceptor agonist isoprenaline (ISO; 1 nm to 100 µm) were performed.

Resistance arteries

Third order mesenteric arteries (mean internal diameter ≈300 µm) were dissected clean of connective tissue and 2 mm segments mounted on the Mulvany-Halpern wire myograph (Mulvany & Halpern, 1977). The vessels were bathed in PSS, heated to 37 °C and gassed continuously with 95 % O2–5 % CO2. The passive tension-internal circumference relationship (IC100) was determined by incremental increases in tension to achieve an internal circumference equivalent to a transmural pressure of 100 mmHg (using the Laplace relationship) and the arteries were set to a diameter equivalent to 0.9 × IC100. Functional integrity of the vessels was assessed as before with 125 mm KPSS. Arteries failing to produce an active tension of 13.3 kPa (100 mmHg) were rejected from the study. Cumulative CRC in response to PE (10 nm to 100 µm) was carried out. Following preconstriction with PE (EC80), cumulative CRCs in response to ACh (1 nm to 100 µm) and ISO (1 nm to 100 µm) were performed.

Responses to ISO were also performed in the presence of the nitric oxide synthase inhibitor Nω-nitro-l-arginine methyl ester (l-NAME; 100 µm). l-NAME was incubated in the bath 30 min before the start of the CRC.

Drugs and chemicals

All chemicals were obtained from Sigma (Poole, UK).

Statistical analysis

All values are given as means ± s.e.m. Contraction in response to KCl/KPSS is expressed as force (g) in aorta preparations or tension (mN mm−1) in mesenteric arteries and contraction in response to PE is expressed as a percentage of the maximal constriction in response to KPSS. Relaxations are expressed as the percentage relaxation of tone induced by PE (EC80). Differences between groups were compared by Student's t test. The -log EC50 was calculated using Prism (GraphPAD Software Inc., San Diego, CA, USA) and compared by Student's t test. Growth curves were compared by two-way analysis of variance. Significance was accepted if P < 0.05.

RESULTS

Growth parameters

Offspring growth

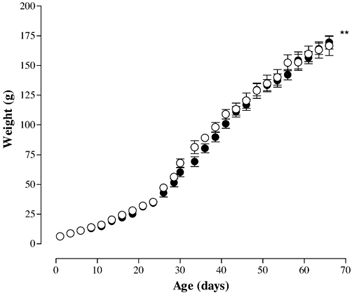

There was no difference in litter size between the two groups. The female offspring in the PR group tended to be smaller at 48 h, although this was not significant (C, 6.25 ± 0.28 g, n = 7; PR, 6.00 ± 0.25 g, n = 10; P > 0.05). In the PR offspring, there was a small difference in growth compared with the C group (Fig. 1; P < 0.01, two-way ANOVA).

Figure 1. Growth of female offspring before mating of C (○) and PR (•) rat dams.

** P < 0.01 effect of diet vs. control (two-way ANOVA).

Weight gained during pregnancy

Before mating, the weights of the offspring were not different between the groups (C, 209.1 ± 4.9 g, n = 12; PR, 201.4 ± 7.3 g, n = 9; P > 0.05). Both groups of pregnant dams gained significant weight from conception to termination at day 19 of gestation, although this weight gain was not different between the two groups (C, 63.1 ± 6.8 g, n = 12; PR, 68.0 ± 5.3 g, n = 9; P > 0.05; Table 1).

Table 1.

Weight gain of dams throughout pregnancy, litter size, fetal and placental weights and the fetal: placental weight ratio

| Group | Initial weight | Weight gain (g) | Litter Size | Fetal weights (g) | Placental weight(g) | Fetal: placental weight ratio |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C (n = 12) | 209.1 ± 4.9 | 63.1 ± 6.8 | 10.4 ± 0.7 | 2.35 ± 0.11 | 0.56 ± 0.02 | 4.38 ± 0.22 |

| PR (n = 9) | 201.4 ± 7.3 | 68.0 ± 5.3 | 10.1 ± 0.5 | 2.13 ± 0.11 | 0.56 ± 0.04 | 4.04 ± 0.27 |

Litter size and fetal and placental weights

There were no differences in the size of litters between the two groups, nor were any differences in fetal weight, placental weight or the fetal : placental weight ratio noted between the two groups (Table 1).

Organ weights

No differences in the weight of the heart, lungs, liver, kidneys, adrenals or pancreas were noted. This was true whether weights were expressed as a gross weight in grams, or as a percentage of total body weight.

Vascular function

Thoracic aorta

Constrictor responses

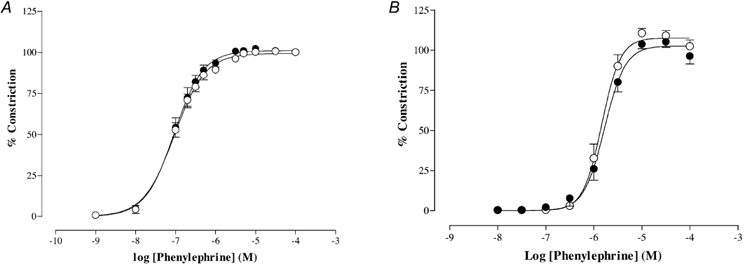

Both KCl and the α1-adrenoceptor agonist PE produced a concentration-dependent vasoconstriction in both the C and PR groups, with no differences between the groups (Table 2 and Fig. 2A).

Table 2.

Vascular function of control and protein-restricted pregnant offspring

| Aorta (n = 5) | Mesenteric (n = 7–9) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| C Group | PR Group | C Group | PR Group | |

| Lumen diameter (μm) | — | — | 314.56 ± 22.84 | 338.34 ± 14.28 |

| Maximal contraction | ||||

| 125 mM KPSS (mN mm−1) | — | — | 2.7 ± 0.3 | 2.9 ± 0.2 |

| KCI (g force) | 0.92 ± 0.01 | 0.96 ± 0.01 | — | — |

| Phenylephrine (% KPSS) | 100 ± 1 | 101 ± 1 | 108 ± 2 | 103.0 ± 2 |

| % maximal relaxation | ||||

| Acetylcholine | 88 ± 5 | 97 ± 8 | 91 ± 2 | 85 ± 2 |

| Isoprenaline | 92 ± 6 | 84 ± 6 | 100 ± 1 | 87 ± 1*** |

| Isoprenaline + l-NAME | — | — | 72 ± 3††† | 77 ± 3††† |

| pEC50 (–log M) | ||||

| KCl | 1.53 ± 0.01 | 1.53 ± 0.01 | — | — |

| Phenylephrine | 7.05 ± 0.03 | 7.05 ± 0.02 | 5.83 ± 0.02 | 5.78 ± 0.03 |

| Acetylcholine | 7.76 ± 0.08 | 7.77 ± 0.03 | 8.23 ± 0.06 | 7.95 ± 0.05** |

| Isoprenaline | 7.50 ± 0.15 | 7.57 ± 0.12 | 7.86 ± 0.02 | 8.09 ± 0.04 |

| Isoprenaline + L-NAME | — | — | 7.42 ± 0.09††† | 7.21 ± 0.10†† |

P < 0.01 PR vs. C in same vascular bed (Student's t test)

P < 0.01 L-NAME vs. C in same vascular bed (Student's t test)

P < 0.001 L-NAME vs. control(Student's t test)

P < 0.001 L-NAME vs. control(Student's t test)

Figure 2. Vasoconstriction induced by phenylephrine (PE) in arteries from pregnant offspring of C (○) and PR (•) pregnant rat dams.

A, thoracic aorta (C, n = 5; PR, n = 5). B, small mesenteric arteries (C, n = 8; PR, n = 9).

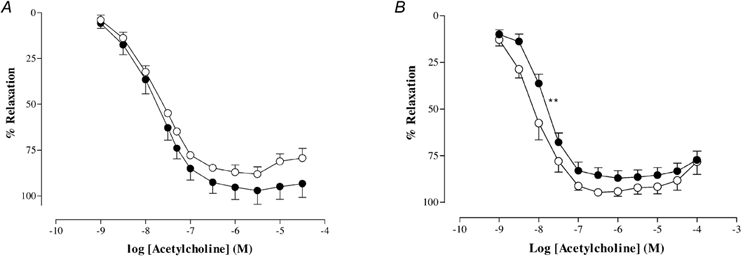

Endothelium-dependent vasodilatation

The endothelium-dependent vasodilator ACh produced a concentration-dependent vasodilatation of PE-induced tone that was similar in both the C and PR groups (Table 2 and Fig. 3A).

Figure 3. Vasodilatation induced by acetylcholine (ACh) in PE preconstricted arteries from pregnant offspring of C (○) and PR (•) pregnant rat dams.

A, thoracic aorta (C, n = 5; PR, n = 5). B, small mesenteric arteries (C, n = 7; PR, n = 8). ** P < 0.01vs. -log EC50 of control relaxation. Results are expressed as percentage relaxation of tone induced by PE (EC80).

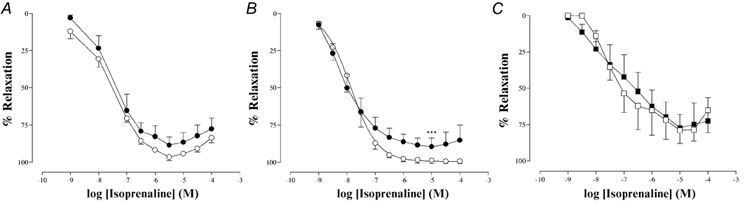

β-Adrenoceptor-mediated vasodilatation

The β-adrenoceptor agonist isoprenaline produced a concentration-dependent vasodilatation of PE-induced tone that was similar in both groups (Table 2 and Fig. 4A).

Figure 4. Vasodilatation induced by isoprenaline in PE preconstricted arteries from pregnant offspring of C and PR pregnant rat dams.

A, thoracic aorta (○, C, n = 5; •, PR, n = 5). B, small mesenteric arteries (○, C, n = 7; •, PR, n = 8). *** P < 0.0001vs. control maximum relaxation. C, small mesenteric arteries in the presence of l-NAME (□, C, n = 5; ▪, PR, n = 8). Results are expressed as percentage relaxation of tone induced by PE (EC80).

Mesenteric artery

Constrictor response

There were no differences in the diameter of the vessels used from each group (Table 2). Maximal contraction in response to 125 mm KPSS was not different between the C and PR groups (Table 2). PE produced concentration-dependent vasoconstriction that was also similar in both the C and the PR group (Table 2 and Fig. 2B). Preconstriction with PE for dilator responses did not differ between C and PR (% maximum response: C, 90 ± 3, n = 14; PR, 90 ± 2, n = 16; P > 0.05).

Endothelium-dependent vasodilatation

In both the C and PR groups, ACh produced a concentration-dependent vasodilatation of PE-induced tone, but the curve was shifted to the right in the PR group compared to the C group (-log EC50: C, 8.23 ± 0.06, n = 7; PR, 7.95 ± 0.05, n = 8; P < 0.01; Table 2 and Fig. 3B). There was no difference in the maximal response to ACh (Table 2 and Fig. 3B).

β-Adrenoceptor-mediated vasodilatation

In both the C and PR groups, isoprenaline produced a concentration-dependent vasodilatation of PE-induced tone, but the maximal response was significantly attenuated in the PR group compared to the C group (% maximum response: C, 100 ± 1, n = 7; PR, 87 ± 1, n = 8; P < 0.0001; Table 2 and Fig. 4B). Following l-NAME (100 µm) pretreatment, the isoprenaline response was significantly attenuated and was similar in both C and PR groups (Table 2 and Fig. 4C).

DISCUSSION

In the rat, maternal protein restriction in pregnancy is associated with vascular dysfunction (Itoh et al. 2002; Koumentaki et al. 2002) and raised blood pressure in the offspring (Langley & Jackson, 1994). To our knowledge, only one study has investigated isolated vascular function in the offspring of rat dams exposed to dietary protein restriction during pregnancy (Brawley et al. 2002a), and none has investigated isolated vascular function in pregnant female offspring. The present study shows that dietary protein restriction in pregnancy induces vascular alterations in isolated resistance arteries, but not in conduit arteries of pregnant female offspring.

Epidemiological evidence suggests an association between low birth weight and an increased risk of cardiovascular diseases such as hypertension and coronary heart disease (Barker, 1992, 1995). However, in animal models, intra-uterine growth restriction is not a prerequisite for cardiovascular dysfunction (see Hoet & Hanson, 1999 for review). In the present study, no differences were seen in the birth weight of the female offspring, although the protein-restricted offspring did tend to be smaller than the controls (ca 5.5 % reduction). Previous reports into protein restriction during pregnancy have shown inconsistent effects on birth weight, with some recording decreased birth weight (Kwong et al. 2000) and others no change (Langley & Jackson, 1994; Langley-Evans et al. 1996). In the present study, the growth curves of the two groups were significantly different, although they could not be described as parallel as others have reported (Langley & Jackson, 1994; Holemans et al. 1999). Catch-up growth has been reported in some restriction models (Kwong et al. 2000; Ozaki et al. 2001) and this has been shown to increase the risk of cardiovascular disease in human populations (Eriksson et al. 1999). It is possible that in our study, the PR group were significantly smaller at birth, but had undergone catch-up growth in the 48 h before they were weighed. However, taking these observations in the rat model together, it is difficult to ascribe any clear link between cardiovascular effects and the birth weight or growth trajectory of the offspring.

No significant differences in organ weights between the pregnant offspring of C and PR dams were observed at late gestation. While no studies have looked at organs weights in pregnant offspring, these results are similar to studies of non-pregnant female offspring from protein-restricted pregnant dams (Desai et al. 1997; Kwong et al. 2000). A number of studies have shown altered organ development as a result of maternal protein restriction, yet these are either specific to male offspring (Ozanne et al. 1998; Kwong et al. 2000) or are no longer apparent when the rats reach the age of those used in the present study (Vehaskari et al. 2001; Woods et al. 2001).

There was no difference between the groups in vasoconstriction of the thoracic aorta and mesentery, suggesting that there is no alteration in the α1-adrenoceptor-mediated constriction pathway. This is supported by evidence from the uterine artery of pregnant dams fed on a protein-restricted diet (Itoh et al. 2002), as well as from mesenteric and femoral arteries of female offspring from dams fed a globally restricted diet (Holemans et al. 1999; Ozaki et al. 2001).

In both the thoracic aorta and the small mesenteric arteries of both groups, the endothelium-dependent vasodilator ACh produced a concentration-dependent relaxation of PE-induced tone. In the thoracic aorta, this response was not different between the C and PR groups, confirming previous observations from aortae of pregnant dams on a protein-restricted diet (Barker et al. 2002a). In the mesenteric arteries, however, the sensitivity of ACh was significantly decreased, as was seen in protein-restricted pregnant dams (Koumentaki et al. 2002) and their male offspring (Brawley et al. 2002a).

The vascular endothelium is important in the control of vascular tone and the regulation of peripheral blood pressure (Vanhoutte, 1989). Endothelial dysfunction has been reported in hypertensive subjects (Panza et al. 1993; Taddei et al. 1993) and is thought to be a risk factor in the development of atherosclerosis, hypertension and other cardiovascular diseases (Ross & Glomset, 1973; Perticone et al. 2001). Such endothelial dysfunction may account for the impaired vasodilatation in response to ACh observed in the isolated mesenteric arteries. This in turn may also be causative of the hypertension previously observed in this model, since mesenteric vessels are known to contribute substantially to peripheral vascular resistance in the rat (Christensen & Mulvany, 1993). Impaired endothelial function has also been shown in mesenteric arteries of female offspring of pregnant dams fed a globally restricted diet (Holemans et al. 1999). It is possible that this attenuation in ACh response may be due to a decrease in NO release from the endothelium. A decrease in basal and ACh-stimulated NO release has been shown in pregnant dams fed a protein-restricted diet (Brawley et al. 2002b) and also in the offspring of patients with essential hypertension (McAllister et al. 1999).

The β-adrenoceptor agonist isoprenaline is known to produce endothelial-dependent vasodilatation in both the thoracic aorta (Gray & Marshall, 1992) and small mesenteric arteries (Graves & Poston, 1993). In the present study, isoprenaline produced vasodilatation in both the isolated thoracic aorta and small mesenteric arteries, and this was seen in both groups of pregnant offspring. In the thoracic aorta, the response to isoprenaline was not different between the two groups, while in the mesenteric arteries the maximal response was attenuated in the PR group. This supports our earlier findings from protein-restricted pregnant dams that isoprenaline-induced vasodilatation is attenuated in the mesenteric arteries (Torrens et al. 2002c) but not in the thoracic aorta (Barker et al. 2002a). The attenuation in isoprenaline-induced vasodilatation in mesenteric arteries may also be explained by endothelial dysfunction or a lack of NO production. In the presence of l-NAME, the isoprenaline response in the mesenteric arteries of each group was significantly attenuated, confirming that in mesenteric arteries isoprenaline-induced vasodilatation is, in part, modulated via a functional endothelium and an NO pathway (Graves & Poston, 1993). In the absence of an NO component, the vasodilatation in response to isoprenaline was similar between the two groups, suggesting a possible NO dysfunction in the PR group. Delpy et al. (1996) proposed that the tonic NO release from the endothelium modulated the isoprenaline response by inhibiting the phosphodiesterases and thus sustaining the cellular cAMP levels. This, together with the decrease in basal NO in mesenteric arteries of protein-restricted pregnant dams (Brawley et al. 2002b), may explain this phenomenon.

The similarity in the results from the present study and our previous findings in protein-restricted pregnant dams (Itoh et al. 2002; Koumentaki et al. 2002) and their offspring (Brawley et al. 2002a) raises the possibility that the offspring of these dams may also develop hypertension and exhibit vascular dysfunction. Hence, the vascular dysfunction seen in this study may have consequences on maternal cardiovascular function, leading to pregnancy complications and thus may mediate transgenerational programming. We now have preliminary evidence that this indeed occurs (Torrens et al. 2002a).

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the British Heart Foundation. C. Torrens is supported by a FOAD Centre studentship.

REFERENCES

- Ahokas RA, Anderson GD, Lipshitz J. Cardiac output and uteroplacental blood flow in diet-restricted and diet-repleted pregnant rats. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 1983;146:6–13. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(83)90918-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahokas RA, Reynolds SL, Anderson GD, Lipshitz J. Maternal organ distribution of cardiac output in the diet-restricted pregnant rat. Journal of Nutrition. 1984;114:2262–2268. doi: 10.1093/jn/114.12.2262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barker AC, Brawley L, Itoh S, Torrens C, Poston L, Hanson MA. Protein restriction in pregnancy does not alter the reactivity of the isolated thoracic aorta in the rat. Journal of Physiology. 2002a;539.P:129P–130P. [Google Scholar]

- Barker AC, Brawley L, Torrens C, Itoh S, Poston L, Hanson MA. Protein restriction in pregnancy does not alter vasodilatation in thoracic aorta from pregnant female rat offspring. FASEB Journal. 2002b;16:A103. [Google Scholar]

- Barker DJ. The fetal origins of adult hypertension. Journal of Hypertension. 1992;10:S39–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barker DJ. Fetal origins of coronary heart disease. British Medical Journal. 1995;311:171–174. doi: 10.1136/bmj.311.6998.171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brawley L, Itoh S, Torrens C, Barker AC, Poston L, Hanson MA. Protein restriction in pregnancy impairs endothelium-dependent and -independent relaxation in small arteries of rat male offspring. Journal of Physiology. 2002a;539.P:123P. [Google Scholar]

- Brawley L, Torrens C, Itoh S, Barker AC, Poston L, Clough GF, Hanson MA. Dietary protein restriction attenuates acetylcholine-induced nitric oxide levels in small mesenteric arteries from pregnant rat dams. FASEB Journal. 2002b;16:A104. [Google Scholar]

- Christensen KL, Mulvany MJ. Mesenteric arcade arteries contribute substantially to vascular resistance in conscious rats. Journal of Vascular Research. 1993;30:73–79. doi: 10.1159/000158978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dahri S, Snoeck A, Reusens-Billen B, Remacle C, Hoet JJ. Islet function in offspring of mothers on low-protein diet during gestation. Diabetes. 1991;40:115–120. doi: 10.2337/diab.40.2.s115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delpy E, Coste H, Gouville AC. Effects of cyclic GMP elevation on isoprenaline-induced increase in cyclic AMP and relaxation in rat aortic smooth muscle: role of phosphodiesterase 3. British Journal of Pharmacology. 1996;119:471–478. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1996.tb15696.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desai M, Byrne CD, Zhang J, Petry CJ, Lucas A, Hales CN. Programming of hepatic insulin-sensitive enzymes in offspring of rat dams fed a protein-restricted diet. American Journal of Physiology. 1997;272:G1083–1090. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1997.272.5.G1083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eriksson JG, Forsen T, Tuomilehto J, Winter PD, Osmond C, Barker DJ. Catch-up growth in childhood and death from coronary heart disease: longitudinal study. British Medical Journal. 1999;318:427–431. doi: 10.1136/bmj.318.7181.427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu-Xiang D, Jameson M, Skopec J, Diederich A, Diederich D. Endothelial dysfunction of resistance arteries of spontaneously hypertensive rats. Journal of Cardiovascular Pharmacology. 1992;20(suppl. 12):S190–192. doi: 10.1097/00005344-199204002-00053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerber RT, Anwar MA, Poston L. Enhanced acetylcholine induced relaxation in small mesenteric arteries from pregnant rats: an important role for endothelium-derived hyperpolarizing factor (EDHF) British Journal of Pharmacology. 1998;125:455–460. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0702099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goto K, Fujii K, Abe I. Impaired β-adrenergic hyperpolarization in arteries from prehypertensive spontaneously hypertensive rats. Hypertension. 2001;37:609–613. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.37.2.609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graves J, Poston L. β-Adrenoceptor agonist mediated relaxation of rat isolated resistance arteries: a role for the endothelium and nitric oxide. British Journal of Pharmacology. 1993;108:631–637. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1993.tb12853.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gray DW, Marshall I. Novel signal transduction pathway mediating endothelium-dependent β-adrenoceptor vasorelaxation in rat thoracic aorta. British Journal of Pharmacology. 1992;107:684–690. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1992.tb14507.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gros R, Benovic JL, Tan CM, Feldman RD. G-protein-coupled receptor kinase activity is increased in hypertension. Journal of Clinical Investigation. 1997;99:2087–2093. doi: 10.1172/JCI119381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoet JJ, Hanson MA. Intrauterine nutrition: its importance during critical periods for cardiovascular and endocrine development. Journal of Physiology. 1999;514:617–627. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1999.617ad.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holemans K, Gerber R, Meurrens K, De Clerck F, Poston L, Van Assche FA. Maternal food restriction in the second half of pregnancy affects vascular function but not blood pressure of rat female offspring. British Journal of Nutrition. 1999;81:73–79. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Itoh S, Brawley L, Wheeler T, Anthony FW, Poston L, Hanson MA. Vasodilation to vascular endothelial growth factor in the uterine artery of the pregnant rat is blunted by low dietary protein intake. Pediatric Research. 2002;51:485–491. doi: 10.1203/00006450-200204000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koumentaki A, Anthony F, Poston L, Wheeler T. Low-protein diet impairs vascular relaxation in virgin and pregnant rats. Clinical Science. 2002;102:553–560. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwong WY, Wild AE, Roberts P, Willis AC, Fleming TP. Maternal undernutrition during the preimplantation period of rat development causes blastocyst abnormalities and programming of postnatal hypertension. Development. 2000;127:4195–4202. doi: 10.1242/dev.127.19.4195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langley SC, Browne RF, Jackson AA. Altered glucose tolerance in rats exposed to maternal low protein diets in utero. Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology. 1994;109:223–229. doi: 10.1016/0300-9629(94)90124-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langley SC, Jackson AA. Increased systolic blood pressure in adult rats induced by fetal exposure to maternal low protein diets. Clinical Science. 1994;86:217–222. doi: 10.1042/cs0860217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langley-Evans SC, Gardner DS, Jackson AA. Association of disproportionate growth of fetal rats in late gestation with raised systolic blood pressure in later life. Journal of Reproduction and Fertility. 1996;106:307–312. doi: 10.1530/jrf.0.1060307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McAllister AS, Atkinson AB, Johnston GD, Hadden DR, Bell PM, McCance DR. Basal nitric oxide production is impaired in offspring of patients with essential hypertension. Clinical Science. 1999;97:141–147. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McVeigh GE, Brennan GM, Johnston GD, McDermott BJ, McGrath LT, Henry WR, Andrews JW, Hayes JR. Impaired endothelium-dependent and independent vasodilation in patients with type 2 (non-insulin-dependent) diabetes mellitus. Diabetologia. 1992;35:771–776. doi: 10.1007/BF00429099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mulvany MJ, Halpern W. Contractile properties of small arterial resistance vessels in spontaneously hypertensive and normotensive rats. Circulation Research. 1977;41:19–26. doi: 10.1161/01.res.41.1.19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nathan L, Cuevas J, Chaudhuri G. The role of nitric oxide in the altered vascular reactivity of pregnancy in the rat. British Journal of Pharmacology. 1995;114:955–960. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1995.tb13297.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ozaki T, Nishina H, Hanson MA, Poston L. Dietary restriction in pregnant rats causes gender-related hypertension and vascular dysfunction in offspring. Journal of Physiology. 2001;530:141–152. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2001.0141m.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ozanne SE, Wang CL, Petry CJ, Smith JM, Hales CN. Ketosis resistance in the male offspring of protein-malnourished rat dams. Metabolism. 1998;47:1450–1454. doi: 10.1016/s0026-0495(98)90068-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paniagua OA, Bryant MB, Panza JA. Transient hypertension directly impairs endothelium-dependent vasodilation of the human microvasculature. Hypertension. 2000;36:941–944. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.36.6.941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panza JA, Casino PR, Badar DM, Quyyumi AA. Effect of increased availability of endothelium-derived nitric oxide precursor on endothelium-dependent vascular relaxation in normal subjects and in patients with essential hypertension. Circulation. 1993;87:1475–1481. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.87.5.1475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perticone F, Ceravolo R, Pujia A, Ventura G, Iacopino S, Scozzafava A, Ferraro A, Chello M, Mastroroberto P, Verdecchia P, Schillaci G. Prognostic significance of endothelial dysfunction in hypertensive patients. Circulation. 2001;104:191–196. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.104.2.191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poston L, McCarthy AL, Ritter JM. Control of vascular resistance in the maternal and feto-placental arterial beds. Pharmacology and Therapeutics. 1995;65:215–239. doi: 10.1016/0163-7258(94)00064-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross R, Glomset JA. Atherosclerosis and the arterial smooth muscle cell: proliferation of smooth muscle is a key event in the genesis of the lesions of atherosclerosis. Science. 1973;180:1332–1339. doi: 10.1126/science.180.4093.1332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosso P, Kava R. Effects of food restriction on cardiac output and blood flow to the uterus and placenta in the pregnant rat. Journal of Nutrition. 1981;110:2350–2354. doi: 10.1093/jn/110.12.2350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosso P, Streeter MR. Effects of food or protein restriction on plasma volume expansion in pregnant rats. Journal of Nutrition. 1979;109:1887–1892. doi: 10.1093/jn/109.11.1887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sunano S, Watanabe H, Tanaka S, Sekiguchi F, Shimamura K. Endothelium-derived relaxing, contracting and hyperpolarizing factors of mesenteric arteries of hypertensive and normotensive rats. British Journal of Pharmacology. 1999;126:709–716. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0702355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taddei S, Virdis A, Mattei P, Salvetti A. Vasodilation to acetylcholine in primary and secondary forms of human hypertension. Hypertension. 1993;21:929–933. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.21.6.929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torrens C, Brawley L, Dance CS, Itoh S, Poston L, Hanson MA. First evidence for transgenerational vascular programming in the rat protein restriction model. Journal of Physiology. 2002a;543.P:41P. [Google Scholar]

- Torrens C, Itoh S, Brawley L, Barker AC, Poston L, Hanson MA. Maternal protein restriction of pregnant rats impairs vasodilatation in their female offspring when pregnant. FASEB Journal. 2002b;16:A104. [Google Scholar]

- Torrens C, Itoh S, Brawley L, Barker AC, Wheeler T, Poston L, Hanson MA. Maternal protein restriction during pregnancy impairs mesenteric vasodilatation in the pregnant rat. Journal of Physiology. 2002c;539.P:122P. [Google Scholar]

- Vanhoutte PM. Endothelium and control of vascular function. State of the Art lecture. Hypertension. 1989;13:658–667. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.13.6.658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vehaskari VM, Aviles DH, Manning J. Prenatal programming of adult hypertension in the rat. Kidney International. 2001;59:238–245. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2001.00484.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woods LL, Ingelfinger JR, Nyengaard JR, Rasch R. Maternal protein restriction suppresses the newborn renin-angiotensin system and programs adult hypertension in rats. Pediatric Research. 2001;49:460–467. doi: 10.1203/00006450-200104000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu HI, Sheu WH, Lai CJ, Lee WJ, Chen YT. Endothelial dysfunction in type 2 diabetes mellitus subjects with peripheral artery disease. International Journal of Cardiology. 2001;78:19–25. doi: 10.1016/s0167-5273(00)00423-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]