Abstract

The obstructive sleep apnoea syndrome (OSA) is a disorder characterised by repetitive closure and re-opening of the upper airway during sleep. Upper airway luminal patency is influenced by a number of factors including: intraluminal air pressure, upper airway dilator muscle activity, surrounding extraluminal tissue pressure, and also surface forces which can potentially act within the liquid layer lining the upper airway. The aim of the present study was to examine the role of upper airway mucosal lining liquid (UAL) surface tension (γ) in the control of upper airway patency. Upper airway opening (PO) and closing pressures (PC) were measured in 25 adult male, supine, tracheostomised, mechanically ventilated, anaesthetised (sodium pentabarbitone), New Zealand White rabbits before (control) and after instillation of 0.5 ml of either 0.9 % saline (n= 9) or an exogenous surfactant (n= 16; Exosurf Neonatal) into the pharyngeal airway. The γ of UAL (0.2 μl) was quantified using the ‘pull-off’ force technique in which γ is measured as the force required to separate two curved silica discs bridged by the liquid sample. The γ of UAL decreased after instillation of surfactant from 54.1 ± 1.7 mN m−1 (control; mean ±s.e.m.) to 49.2 ± 2.1 mN m−1 (surfactant; P < 0.04). Compared with control, PO increased significantly (P < 0.04; paired t test, n= 9) from 6.2 ± 0.9 to 9.6 ± 1.2 cmH2O with saline, and decreased significantly (P < 0.05, n= 16) from 6.6 ± 0.4 to 5.5 ± 0.6 cmH2O with surfactant instillation. Findings tended to be similar for PC. Change in both PO and PC showed a strong positive correlation with the change in γ of UAL (both r > 0.70, P < 0.001). In conclusion, the patency of the upper airway in rabbits is partially influenced by the γ of UAL. These findings suggest a role for UAL surface properties in the pathophysiology of OSA.

The obstructive sleep apnoea syndrome (OSA) is characterised by repetitive closure and re-opening of the upper airway during sleep. A widely accepted analysis of the control of upper airway patency is based on the concept that upper airway lumenal size will be dependent on the balance of forces acting across the upper airway walls (Remmers et al. 1978). While the role played by intraluminal pressure and the action of upper airway dilator muscles in determining this balance of forces has been extensively studied, little attention has been paid to other forces that may be in operation.

In 1980 Wilson and colleagues (Wilson et al. 1980) reported postmortem studies in infants demonstrating that the intraluminal pressure required to re-open a closed upper airway (PO) was greater than the intraluminal pressure present during closure of the same airway (PC). This difference between PO and PC was ascribed to the force required to overcome ‘adherence’ between the walls of the closed airway. These findings suggested that surface effects due to the liquid lining the upper airway (UAL) exert an influence on upper airway patency. Since these first observations there have been few studies that have addressed this concept. Olson & Strohl (1988a) demonstrated that stimulation of upper airway secretions in rabbits made the collapsed upper airway more difficult to re-open (i.e. increased PO). This effect was ascribed to ‘stickiness’ of the induced upper airway secretions. In dogs, instillation into the upper airway of substances thought to have surface tension-lowering properties was associated with a reduction in airflow resistance (Widdicombe & Davies, 1988), decreased the degree of genioglossus muscle recruitment required to re-open the closed upper airway (Miki et al. 1992), and also decreased both PO and PC (Crawford et al. 1996).

In humans, studies are even more limited. Hoffstein et al. (1987) demonstrated reduced snoring in sleeping subjects after instillation of a ‘long acting tissue lubricant’ into the upper airway. More recently, Jokic et al. (1998) found that application of a topical lubricant consistently reduced the severity of OSA. These findings imply a pathogenetic role for UAL surface-related forces in OSA, and a potential role for therapeutic modulation of these forces in the treatment of OSA. An important contribution was made by van der Touw et al. (1997) who used fluoroscopy to study the patency of the upper airway in normal human subjects before and after instillation of a known exogenous surfactant (Exosurf Neonatal) into the upper airway. These studies demonstrated an ∼7 cmH2O reduction in PC and ∼19 cmH2O reduction in PO with surfactant but not with a saline control. Moreover, post-surfactant pharyngeal diameters were increased, relative to control, over most intraluminal pressures studied.

All the above studies suggest that forces due to the UAL play a measurable role in the determination of upper airway patency. However, this area of study is characterised by confusion regarding the nature of these forces and the lack of any direct measurements of the forces themselves. In addition, potential for the confounding effects of upper airway dilator muscle recruitment (Hoffstein et al. 1987; Van der Touw et al. 1997) and poor characterisation of the substances added to the upper airway (Widdicombe & Davies, 1988) limit the interpretation of some studies.

Recently, we described a method for measuring the surface tension (γ) of small volume (∼0.2 μl) liquid samples and applied this method to the measurement of γ of saliva (Kirkness et al. 2000). This method assesses the force required to separate two curved surfaces bridged by a droplet of the liquid under examination. In the present study, we apply this approach to the assessment of the γ of UAL and its relationship to upper airway patency. We performed our studies in an anaesthetised animal model where upper airway muscle recruitment could be controlled and the direct effects of alteration of γ of UAL studied.

METHODS

Animals

Studies were performed in 25 adult male New Zealand White rabbits (3–4 kg). The protocol was approved by the Western Sydney Area Health Service Animal Ethics Committee.

Anaesthesia

Induction of anaesthesia was achieved via an intramuscular injection of ketamine (35 mg kg−1) and xylazine (5 mg kg−1). Surgical preparation was performed whilst rabbits were anaesthetised with either ketamine (40 mg h−1)/xylazine (12 mg h−1) delivered intravenously, or halothane (1–2 %) via inhalation. Following instrumentation, anaesthesia during the data-gathering phase of the protocol was maintained with intravenous sodium pentobarbitone (24 mg h−1). Animals were killed at completion of the study, using an overdose of intravenous sodium pentobarbitone.

Surgery

Rabbits were studied in the supine posture. A tracheostomy was performed between the third and the fourth tracheal cartilage rings. Both the proximal and distal tracheal segments were cannulated. The caudal tracheal stump was connected to a pressure cycled ventilator (BT200, Bourns Life Systems, Riverside, CA, USA; 4–5 cmH2O maximum pressure; inspiratory:expiratory ratio 1:1.5; 50 cycles min−1; plus supplemental oxygen). The oesophagus was isolated and tied off at the level of the larynx.

Experimental set up

The mouth was taped shut and a mask was placed over the snout (sealed with petroleum jelly). The system was leak free to a positive air pressure of ∼15 cmH2O over 30 s. A 5 ml syringe was connected to the caudal end of the cranial tracheal stump and then used to systematically inflate and deflate the isolated upper airway. The volume of gas injected into the upper airway (ΔV) was measured using a linear slide potentiometer attached to the plunger of the syringe. Separate pressure transducers (Celesco ±200 cmH2O, IDM Instruments, Dandenong, Australia) were used to monitor the pressure inside the mask (PM) and in the cranial tracheal stump (PUA). Data were digitised (MacLab 16 s, ADInstruments, Sydney, Australia) and stored on a Macintosh computer for later analysis.

Electromyograms

Fine wire bipolar electrodes were positioned under direct vision in both the left and right sternohyoid (SH) muscle. The raw electromyographic (EMG) signals were filtered (80 Hz to 1 kHz), amplified, rectified and passed through a leaky integrator with a time constant of 100 ms to produce moving time average electromyograms (Neotrace NT 1900, Neomedix Systems, Sydney, Australia). The raw EMG signals were also connected to a speaker box. Correct placement of the wires was confirmed by: (1) the appropriate neck muscle contraction produced in response to direct electrical stimulation of the muscle; and (2) auditory confirmation of increased inspiratory motor unit activity during hypercarbic stimulation of ventilation. The integrated SH EMG was then monitored continuously throughout the protocol.

Surface tension measurements

The UAL was sampled by advancing polyethylene tubing (i.d. 0.5 mm; o.d. 0.8 mm) into the pharynx via the cranial tracheal stump and aspirating with a 1 ml syringe (7000.5N, Terumo Medical Corporation, Elkerton, USA), thus drawing a small quantity (∼0.2 μl) of UAL into the tubing. Samples were transferred to the surface force measurement device and the γ of UAL was then measured via the ‘pull-off’ force technique (Kirkness et al. 2000). In addition, the γ of a saliva sample obtained from the oral cavity immediately after anaesthesia induction was obtained as a pre-surgery control value.

Exogenous surfactant

The γ of UAL was altered by instilling an exogenous surfactant into the upper airway. Exosurf Neonatal (Exosurf Neonatal; GSK, Greenville, NC, USA) is stored under vacuum as a sterile white lyophilised powder in vials. Each vial contains 108 mg colfosceril palmitate formulated with 12 mg cetyl alcohol, 8 mg tyloxapol and 47 mg NaCl. When reconstituted with 8 ml of sterile water, Exosurf Neonatal suspension contains 13.5 mg ml−1 colfosceril palmitate, 1.5 mg ml−1 cetyl alcohol and 1 mg ml−1 tyloxapol in 0.1 M NaCl, and has an osmolarity of 185 mosmol l−1. The γ of Exosurf Neonatal has been reported to be between 38 and 44 mN m−1 (Schurch, 1993; Amirkhanian & Merritt, 1995).

Protocol

Following initial sampling of UAL and measurement of γ, 3–5 ml of air were injected into the upper airway at a rate of 0.2–1.0 ml s−1 until both PM and PUA reached 10–15 cmH2O. Air was than slowly withdrawn from the upper airway until PM no longer changed while PUA continued to fall. This quasi-static cycle was repeated 5–7 times per run with 2–6 runs being performed for each condition in each rabbit. Measurement of the γ of UAL was then repeated.

Following collection of control data, 0.5 ml of either 0.9 % saline (saline; n= 9) or an exogenous surfactant (surfactant; n= 16; Exosurf Neonatal) was instilled into the pharyngeal airway, via a multi-holed catheter advanced through the tracheostomy and the protocol was repeated.

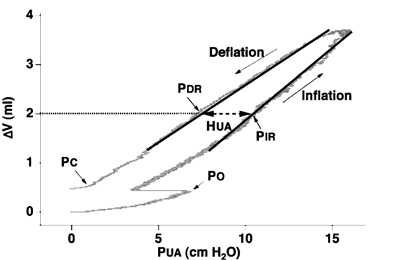

Data analysis

The PO and PC were measured using a technique similar to that described by Olson & Strohl, (1988b). As air was injected into the upper airway increasing PUA, PM did not immediately change (i.e. the upper airway was spontaneously closed in all rabbits). The value of PUA when PM began to increase was defined as PO (Fig. 1). During withdrawal of gas from the upper airway, the value of PUA at the point where PM ceased to change was defined as PC. For each inflation-deflation cycle, change in upper airway volume (ΔV) was plotted against PUA generating partial upper airway pressure-volume relationships (from PUA=PC to PUA= 10–15 cmH2O). Over most of the range of ΔV studied, these relationships were approximately linear, but hysteresis of the upper airway pressure-volume relationship was evident for all such measurements. Upper airway wall compliance was calculated from the slope of separate linear regression lines fitted to the linear portion of both the inflation (CUAI) and deflation (CUAD) limbs of the quasi-static pressure-volume curves (Fig. 2). The PUA at a ΔV of 2 ml (Fig. 2) was measured for both the inflation (PIR) and deflation (PDR) regression lines. Hysteresis (HUA) was measured as PIR−PDR.

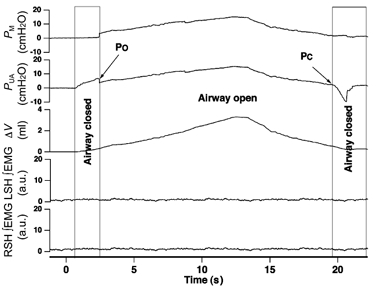

Figure 1. Raw data recording opening and closing pressures.

Raw data recording showing pressure in the face mask (PM), pressure recorded at the caudal end of the upper airway (PUA), and change in upper airway volume (ΔV). As air is added to the upper airway PUA increases immediately, whereas PM does not change (airway closed) until a critical PUA is reached i.e. the upper airway opening pressure (PO). During the withdrawal of air from the upper airway a PUA is reached where PM no longer changes in parallel with PUA, i.e. the upper airway closing pressure (PC). Phasic ∞EMG activity was absent for both left (LSH) and right sternohyoid (RSH) muscles throughout the measurement.

Figure 2. Upper airway wall compliance and recoil pressures.

Representative upper airway pressure (PUA) volume (ΔV) recording during control conditions in one rabbit. Upper airway wall compliance was calculated as the slope of the linear regression lines (continuous lines) fitted to the inflation and deflation limbs of the pressure-volume relationship over the same volume range. PC closing pressure, PO opening pressure, PDR deflation recoil pressure, PIR corresponding inflation recoil pressure. Hysteresis (HUA; dashed line) was calculated as PIR−PDR.

Individual upper airway mechanics measurements were averaged to obtain mean values for each run. Run values were then averaged to obtain individual rabbit data for each condition. Individual rabbit values were then pooled to obtain group mean data. The γ of UAL for each condition was determined as the average of the values obtained before and after each set of upper airway mechanics measurements. Data were expressed as means ±s.e.m. Values for γ of UAL obtained before and after upper airway mechanics measurements were compared using Student's paired t test. Repeated measures analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to assess the effect of saline or surfactant administration on γ of UAL, PO, PC, PO−PC, PIR, PDR and HUA. For the measured variables where there was a statistically significant difference between the change observed within rabbits instilled with surfactant and that observed in those instilled with saline, the groups were analysed separately. Individual relationships between the change in γ of UAL associated with saline and surfactant instillation and the corresponding change in PO, PC, CUAI, CUAD, HUA and PO−PC were all tested using linear regression analysis. P < 0.05 was considered significant.

RESULTS

EMG data

No phasic EMG activity of the SH muscles was detected throughout the study (see Fig. 1).

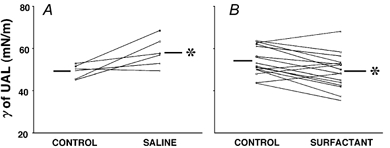

Surface tension of upper airway lining liquid

Under control conditions, measurements of γ of UAL were obtained in 22 rabbits, six prior to saline and 16 prior to surfactant. There was no significant difference (P > 0.2) between the γ of UAL before and after the measurement of upper airway mechanics. During control, the γ of UAL ranged from 43.6 to 63.6 mN m−1 with a mean value of 54.2 ± 1.3 mN m−1 (n= 22). Following saline, γ of UAL increased by >3.7 mN m−1 in four rabbits but was unchanged in the remaining two rabbits. For the group, γ of UAL increased from 52.1 ± 1.9 to 58.1 ± 2.1 mN m−1 (n= 6; P < 0.04; Fig. 3). Following surfactant, γ of UAL decreased by > 3.6 mN m−1 in 12 rabbits but increased by > 3.0 mN m−1 in the remaining four rabbits. For the group, γ of UAL decreased from 54.1 ± 1.7 to 49.2 ± 2.1 mN m−1 (n= 16; P < 0.005; Fig. 3).

Figure 3. Effect of exogenous surfactant and saline on γ of UAL.

Individual data for γ of UAL under control vs. saline (A) and control vs. surfactant (B) conditions. Note that increases in γ of UAL occurred in the majority of rabbits with saline, while decreases occurred in most rabbits with surfactant. Different lines represent individual rabbits. *P < 0.05vs. control. Bars represent group mean values.

For all rabbits the pooled data (n= 19) for γ of the presurgery saliva samples (54.4 ± 1.1 mN m−1) was not significantly different from that of all control UAL samples obtained from the posterior pharynx (54.3 ± 1.5 mN m−1; P= 0.95). These saliva data for seven animals have been reported previously (Kirkness et al. 2000).

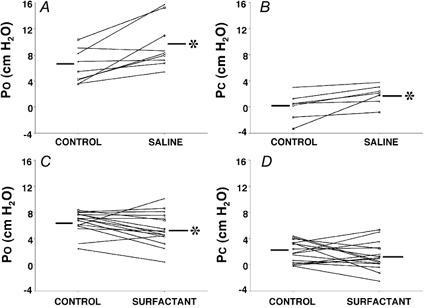

Upper airway opening pressure

Following saline, PO increased by >1.8 cmH2O in six of nine rabbits but was unchanged in the remaining three rabbits (Fig. 4A and C). Following surfactant, PO decreased by >1.5 cmH2O in nine of 16 rabbits, increased by > 0.5 cmH2O in three and remained unchanged in four rabbits. For the group, PO increased significantly from 6.2 ± 0.9 cmH2O (control) to 9.6 ± 1.2 cmH2O (P < 0.04) with saline, and decreased significantly from 6.6 ± 0.4 to 5.5 ± 0.6 cmH2O (P= 0.05) with surfactant (Fig. 4). There was no difference between the control values for the two groups (P= 0.6).

Figure 4. Effect of exogenous surfactant and saline on PO and PC.

Individual data for PO (A and C) and PC (B and D) under control, saline and surfactant conditions. Note that increases in both PO and PC occurred in the majority of rabbits with saline, while decreases occurred in most rabbits with surfactant. This was a significant change for all conditions except for PC with surfactant. Different lines represent individual rabbits. *P < 0.05vs. control. Bars represent group mean data.

Upper airway closing pressure

Technically acceptable measurements of PC were obtained in seven rabbits for saline and in all 16 rabbits for surfactant. Following saline, PC increased by > 0.8 cmH2O in five rabbits, but was unchanged in the remainder Fig. 4B and D). Following surfactant, PC decreased by > 0.7 cmH2O in eight rabbits, increased by > 0.8 cmH2O in six and was unchanged in the two remaining rabbits. For the group, while PC increased significantly from 0.1 ± 0.7 to 1.9 ± 0.6 cmH2O with saline (P < 0.03) there was no significant change with surfactant (1.9 ± 0.8 versus 1.3 ± 0.5 cmH2O, P= 0.3). Saline control values were significantly lower than surfactant control values (P < 0.03) primarily because of negative values obtained in two rabbits.

PO−PC and HUA

In all rabbits in which both PO and PC measurements were obtained (n= 23), PO was greater than PC under all conditions. There was a tendency for the PO−PC group mean values to increase with saline (5.2 ± 0.6 versus 6.0 ± 0.7 cmH2O, n= 7) and to decrease with surfactant 4.8 ± 0.3 versus 4.3 ± 0.3 cmH2O, n= 16); however, neither of these changes achieved significance (both P= 0.13).

For PIR, PDR and HUA there were no statistically significant differences between the within-rabbit changes for saline and surfactant (all P > 0.17), consequently, an overall test for change in the combined groups was performed. For PIR, saline and surfactant control values were 8.1 ± 0.7 and 9.9 ± 0.5 cmH2O, respectively. For PDR these values were 5.8 ± 0.8 and 7.2 ± 0.6 cmH2O, respectively. There was no significant effect of saline or surfactant on PIR or PDR (all P > 0.3). Similarly, for HUA, saline and surfactant control values were not significantly different (2.3 ± 0.2 versus 2.7 ± 0 cmH2O) and there was no change from control for either saline (2.5 ± 0.1 cmH2O) or surfactant 2.4 ± 0.2 cmH2O; all P= 0.8).

Upper airway wall compliance

Upper airway wall compliance data were obtained in three rabbits for saline and in 14 rabbits for surfactant. While CUAI was significantly greater than CUAD for control (P < 0.003; paired t test), and for both saline (P < 0.03) and surfactant (P < 0.001), neither saline nor surfactant was associated with a change in the group-mean values for CUAI or CUAD (P > 0.2; Table 1).

Table 1.

Upper airway wall compliance values

| Control (ml cmH2O−1) | Saline (ml cmH2O−1) | Control (ml cmH2O−1) | Surfactant (ml cmH2O−1) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CUAI | 0.38 ± 0.02 | 0.36 ± 0.02 | 0.29 ± 0.02 | 0.29 ± 0.03 |

| CUAD | 0.32 ± 0.02* | 0.28 ± 0.01† | 0.25 ± 0.02* | 0.24 ± 0.02‡ |

Upper airway inflation (CUAI) and deflation (CUAD) compliance values (means ±s.e.m.).

For CUAI vs. CUAD

P<0.003

P<0.03

P<0.001.

Relationship between γ of UAL and upper airway patency

When all data were pooled, changes in PO and PC (both r > 0.7, P < 0.001; Fig. 5) and change in PO−PC (r= 0.41, P= 0.05), but not change in HUA (P > 0.3), were positively correlated with change in γ of UAL. However, a negative correlation was found between change in CUAD (but not change in CUAI; P > 0.1) and change in γ of UAL (r= 0.6, P < 0.005). There was no significant relationship between change in PIR and PDR and change in γ of UAL (both r < 0.26, P > 0.1).

Figure 5. Influence of changing γ on upper airway mechanics.

Change (control minus saline (triangles) or surfactant (circles) PC (in ΔPC; A, filled symbols) and PO (in ΔPO; B, open symbols) for each rabbit plotted against change in γ of UAL (Δγ;control minus saline or surfactant). Linear regression lines are shown. Note the strong positive correlations between Δγ and both ΔPC and ΔPO.

DISCUSSION

This study has established, for the first time, a quantitative relationship between the γ of UAL and mechanical factors influencing upper airway patency. In particular, we have demonstrated that in anaesthetised rabbits there are significant correlations between change in γ of UAL and changes in PO, PC, CUAD and PO−PC, but not PIR, PDR or HUA. When γ of UAL was increased (by instillation of normal saline into the upper airway) the airway both closed and re-opened at a more positive intraluminal pressure than under control conditions. Whereas, when the γ of UAL was reduced (by the instillation of an exogenous surfactant) the airway closed and re-opened at reduced positive intraluminal pressures. These findings support the hypothesis that γ of UAL contributes a force acting on the upper airway wall that hinders airway opening but is modifiable through the instillation of surface active agents into the upper airway lumen.

Critique of methods

The rabbit upper airway model has been employed extensively in previous studies of upper airway mechanics including those of the recruitment and mechanical effects of upper airway dilator muscles (Rothstein et al. 1983; Olson et al. 1989; Woodall et al. 1989). Recruitment of upper airway dilator muscles such as the genioglossus and sternohyoid muscles constitutes a potential confounding effect in studies examining the influence of γ of UAL on upper airway patency because these muscles are strongly recruited by negative upper airway pressure and have important effects on upper airway lumen size and collapsibility (Mathew et al. 1982a,b; Rothstein et al. 1983). In the present study we deliberately suppressed upper airway muscle activity by using a protocol featuring isolation of the upper airway, mechanical ventilation and deep barbiturate anaesthesia. Lack of upper airway dilator muscle recruitment during measurement of PO and PC was confirmed by monitoring SH muscle EMG activity.

UAL samples were obtained by advancing a catheter into the pharynx via the cranial tracheal segment. It is possible that this sampling method may have failed to obtain a representative sample of UAL. Similarly, exogenous surfactant and saline were introduced into the upper airway by a catheter advanced blindly into the pharynx. Non-uniform distribution of these agents may be responsible for the failure to lower the γ of UAL with exogenous surfactant in some rabbits. This failure to change γ of UAL uniformly in all rabbits impacted on our ability to detect an effect of surfactant instillation on PC. Compliance, PIR, PDR and HUA values were obtained from the linear portions of the pressure-volume relationships. This will have influenced the absolute values obtained since the entire pressure-volume relationship was not examined. However, these values represent the elastic properties of the airway wall when the airway is patent and were used to assess effects of changing γ of UAL when the distance between mucosal surfaces was relatively large.

A strength of the present study is the direct measurement of γ of UAL. All previous studies on this topic have assumed that the addition of exogenous surfactant to the upper airway changes upper airway surface properties but have made no measurements to confirm this assumption (Widdicombe & Davies, 1988; Miki et al. 1992; Crawford et al. 1996; Van der Touw et al. 1997; Jokic et al. 1998). In the present study, measurement of γ of UAL permitted the relationship between γ of UAL and upper airway mechanical properties to be examined directly.

Surface tension of UAL

The values for γ measured in the present study are the first measurements reported in the literature for UAL. At ∼52 mN m−1 the γ of rabbit UAL is substantially less than that for water (71.2 mN m−1; Lide, 2001) reflecting the presence of endogenous surfactants in rabbit UAL. While UAL has not been previously studied, there have been a number of previous studies examining the γ of saliva (Braddock et al. 1970; Glantz, 1970). Saliva is 95% water but contains small concentrations of phospholipids with surfactant properties (Demmers & Belting, 1967; Vassilakos et al. 1992). There are no studies that report γ for rabbit saliva, although reported values for the γ of human saliva range from 53.1 to 57.0 mN m−1 (Braddock et al. 1970; Glantz, 1970). In the current study, the γ of UAL was not different from that of the pre-surgery control saliva sample obtained from the oral cavity and was in the same range as that reported in the literature for human saliva. It appears that at least in regard to its surface force properties, the UAL of the pharynx is similar to saliva.

Instillation of saline into the pharynx was associated with an increase in the γ of UAL. This may be due to the following: (1) saline may lead to an increase in the secretion of glycopolysaccharides (Anderson et al. 1997); (2) saline may increase the re-absorption of surface active particles across the epithelial lining (Rahmoune & Shephard, 1994); or (3) isotonic saline in the upper airway may replace surface active substances, already in the UAL, with a high γ liquid (Hida & Hildebrandt, 1984). The lower γ of UAL after instillation of surfactant is attributed to exogenous surfactant adhering to the mucosal surface decreasing the free energy at the surface of the UAL (Scarpelli et al. 1992).

Balance of forces model

Upper airway patency is determined by the net balance of forces operating across the upper airway walls (Remmers et al. 1978). Upper airway collapsing forces have previously been attributed to intra-luminal negative pressures (Mathew et al. 1982a, 1984; Harms et al. 1996; Eastwood et al. 1998), upper airway constrictor muscle activity (Kuna & Smickley, 1997; Kuna & Vanoye, 1997), and compressive pressures exerted by the surrounding tissues (Winter et al. 1996, 1997). These collapsing forces are opposed by the intrinsic elastic properties of the airway wall and, most importantly, by upper airway dilator muscle activity (Strohl et al. 1987; Wiegand & Latz, 1991; van Lunteren & Manubay, 1992; Bishara et al. 1995).

The present study has now demonstrated that the γ of UAL is an additional property that influences the force necessary to open the upper airway. This may be particularly important when surfaces are apposed (i.e. airway closed) or in regions where the mucosa may fold forming tightly curved surfaces. A characteristic of the normal human upper airway is the presence of mucosal folds and this is accentuated in the case of OSA patients (Kuna et al. 1988). Surface forces may be operative in these folds keeping the mucosal surfaces in contact and contributing to both the thickening of the lateral pharyngeal walls and the elliptical cross-sectional shape of the pharyngeal airway characteristic of patients with OSA (Schwab et al. 1995).

Surface forces

The important surface-related forces in a system such as the upper airway mucosal surface are, under normal physiological conditions, related to the presence of fluid lining the mucosa. Both the γ and the viscosity of the upper airway fluid may play a role in these forces, and often a combination of the two will be important in considering the influence of surface forces on upper airway patency.

Liquid-coated surfaces will adhere to each other, and in the case of two ideally flat surfaces the force holding them together, or the contact adhesion, depends only on the γ of the liquid and the separation between the surfaces (d). If one postulates a continuous film that wets both surfaces, the pressure ΔP holding the surfaces together is ΔP= 2γ/d. The smaller the surface separation and the larger the γ, the greater the force holding the surfaces together. As d may be a micron or less for smooth surfaces, the pressure can easily reach several atmospheres! Adhesion between liquid-coated surfaces is, thus, due to the γ of the liquid, which in turn is ultimately due to the cohesive forces between the molecules of the liquid. Reducing the γ by, for example, the addition of exogenous surfactant will reduce the adhesion.

However, the force required to separate the surfaces depends very much on the exact manner in which the surfaces are separated. A simple analogy may be made with two microscope glass slides between which a drop of water is placed. The water will form a very thin film between the two slides, and quite some force will be required to separate the two slides by pulling in a direction normal to the surfaces. In contrast, it is easy to slide the surfaces against one another and separate them by letting one surface slide completely away from the other. If instead of glass slides one has two flexible sheets of plastic, the sheets may be easily separated by peeling them away from one another. Furthermore, because the act of opening is a dynamic process, non-equilibrium processes related to the viscosity and possible visco-elasticity (stickiness) of the fluid may also come into play. These will act to retard the opening process (imagine a film of sticky honey between the surfaces) and the force will need to be applied for longer even to slide or peel the surfaces apart.

In the upper airway, the opposing tissues of the collapsed passage are obviously far from ideally smooth and flat, but because the tissues are deformable very intimate contact may well be achieved. Separation in the presence of a fluid film hence presents us with essentially the same overall problem to consider as in the case of two flexible sheets of plastic - the force required to effect separation of the tissue walls will very much depend on details of the opening process. In the upper airway, of course, the magnitude of the required force is subject to further complications such as folds of the airway being kept locally closed by pockets of mucosal fluid, regions of entrapped air in the closed airway, etc.

Nevertheless, it is clear that reducing the γ of the liquid lining the upper airway can only reduce the force required to separate the opposing surfaces, provided that factors such as viscosity are not greatly affected. It should here be noted that surfactants will significantly lower the γ of water at concentrations far below those that influence the viscosity.

Upper airway opening and closing pressures

In anaesthetised, tracheostomised, mechanically ventilated, supine rabbits, PC was approximately equal to atmospheric pressure. When saline was added to the upper airway, PC increased to ∼2 cmH2O (i.e. the airway was closed at a more positive intraluminal pressure). This finding suggests that application of saline to the upper airway is associated with an additional collapsing force of ∼2 cmH2O. When exogenous surfactant was added to the upper airway there was no group-mean change in PC. This finding, however, appears to be related to the fact that instillation of surfactant failed to lower the γ of UAL in some rabbits. Indeed, a strong positive correlation between the change in PC and the change in γ of UAL was identified when the saline and surfactant data were pooled.

Under control conditions a positive intraluminal pressure of ∼6 cmH2O was required to open the airway. Instillation of saline into the upper airway was associated with an ∼3 cmH2O increase in PO, while exogenous surfactant led to an ∼1 cmH2O decrease in PO. In addition, in the present study there was a strong positive correlation between the change in PO and the change in γ of UAL. These findings suggest that the γ of UAL exerts a measurable collapsing force on the upper airway that can be modified by the instillation of surface active agents into the upper airway.

Upper airway wall compliance

Upper airway wall compliance values of ∼0.2–0.3 ml cmH2O−1 were obtained in the present study, a value about double that reported for rabbits by Olson and co-workers (Olson et al. 1989). The more compliant upper airway demonstrated in the present study is likely to be related to the deliberate suppression of upper airway dilator muscle activity. While the airway was less compliant during deflation than during inflation, CUAI was unaffected by change in γ of UAL. However, change in CUAD was negatively correlated with change in γ of UAL. Thus, during deflation of the upper airway a decrease in γ of UAL was associated with an increase in wall compliance, reflecting a reduction in the collapsing force exerted by γ of UAL on the upper airway walls.

PO−PC and HUA

Previous studies have consistently demonstrated a difference between upper airway PO and PC in both animal (Crawford et al. 1996) and human studies (Wilson et al. 1980; Van der Touw et al. 1997). In the present study change in PO−PC was positively correlated with change in γ of UAL. Thus, as γ of UAL fell the difference between PO and PC was reduced. However, this relationship appeared to only explain 17 % of the variance indicating that while γ of UAL does contribute to PO−PC, other factors may have a much greater influence. Thus, over the range of γ studied, the contribution of γ of UAL to the adherence of upper airway walls only explains a portion of the effect. Other factors, such as non-equilibrium surface forces (e.g. viscosity) and inertial factors associated with the airway walls and surrounding tissues may be more important.

While we were able to demonstrate a relationship between upper airway wall recoil pressure at opening and closing and γ of UAL this was not the case when the airway was already open. Thus, PIR, PDR and HUA were not influenced by the range of γ of UAL studied. This might be expected since the distances separating upper airway mucosal surfaces would be much larger than at the point of airway closure. Since HUA was unaffected by γ of UAL it would seem that hysteresis of the upper airway wall pressure volume relationship (above PC) is more related to the elastic properties of the surrounding tissues than the γ of UAL.

Conclusion

In the present study, following saline or surfactant instillation into the upper airway, the change in γ of UAL correlated strongly with the change in both PO and PC. The association of a change in PO with a change in γ of UAL means that as the γ forces of the liquid in the upper airway are lowered the airway becomes easier to re-open. Similarly, the ability of the upper airway to remain open under the influence of a collapsing force is enhanced when the liquid lining the upper airway has lower γ forces. Thus, γ is potentially an important factor determining airway patency especially when airway walls are apposed or nearly apposed (i.e. the distances separating the mucosal surfaces are small). This is the first study to measure and examine γ of UAL in relation to upper airway wall mechanical properties. We conclude that patency of the upper airway is influenced by γ of UAL and that this relationship can be manipulated by instillation of surface active agents into the upper airway.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by The Garnett Passe and Rodney Williams Memorial Foundation, Westmead Millennium Foundation and NH & MRC of Australia. The authors would like to thank Salman Ali and Laila Wahidi for technical assistance and Karen Byth for statistical advice.

References

- Amirkhanian JD, Merritt TA. The influence of pH on surface properties of lung surfactants. Lung. 1995;173:243–254. doi: 10.1007/BF00181876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson KE, Rogers JA, Li D. An interfacial tension model of the interaction of water-soluble polymers with phospholipid composite monolayers. J Pharm Pharmacol. 1997;49:587–591. doi: 10.1111/j.2042-7158.1997.tb06849.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bishara H, Odeh M, Schnall RP, Gavriely N, Oliven A. Electrically-activated dilator muscles reduce pharyngeal resistance in anaesthetized dogs with upper airway obstruction. Eur Respir J. 1995;8:1537–1542. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braddock LI, Margallo E, Barbero GJ. Salivary surface tension and turbidity in cystic fibrosis. J Dent Res. 1970;49:464. doi: 10.1177/00220345700490025201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crawford ABH, Van der Touw T, O'Neill N, Amis T. Synthetic exogenous surfactant enhances patency of the passive upper airway in dogs. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1996;153:A692. [Google Scholar]

- Demmers DG, Belting CM. Effect of surfactants and proteolytic enzymes on artificial calculus formation. J Periodontol. 1967;38:294–301. doi: 10.1902/jop.1967.38.4.294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eastwood PR, Curran AK, Smith CA, Dempsey JA. Effect of upper airway negative pressure on inspiratory drive during sleep. J Appl Physiol. 1998;84:1063–1075. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1998.84.3.1063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glantz PO. The surface tension of saliva. Odontol Revy. 1970;21:119–127. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harms CA, Zeng YJ, Smith CA, Vidruk EH, Dempsey JA. Negative pressure-induced deformation of the upper airway causes central apnea in awake and sleeping dogs. J Appl Physiol. 1996;80:1528–1539. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1996.80.5.1528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hida W, Hildebrandt J. Alveolar surface tension, lung inflation, and hydration affect interstitial pressure (Px(f)) J Appl Physiol. 1984;57:262–270. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1984.57.1.262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffstein V, Mateiko S, Halko S, Taylor R. Reduction in snoring with phosphocholinamin, a long-acting tissue-lubricating agent. Am J Otolaryngol. 1987;8:236–240. doi: 10.1016/s0196-0709(87)80009-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jokic R, Klimaszewski A, Mink J, Fitzpatrick MF. Surface tension forces in sleep apnea: the role of a soft tissue lubricant: a randomized double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1998;157:1522–1525. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.157.5.9708070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirkness JP, Amis TC, Wheatley JR, Christenson HK. Determining the surface tension of microliter amounts of liquid. J Colloid Interface Sci. 2000;232:408–409. doi: 10.1006/jcis.2000.7146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuna ST, Bedi DG, Ryckman C. Effect of nasal airway positive pressure on upper airway size and configuration. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1988;138:969–975. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/138.4.969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuna ST, Smickley JS. Superior pharyngeal constrictor activation in obstructive sleep apnea. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1997;156:874–880. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.156.3.9702053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuna ST, Vanoye CR. Respiratory-related pharyngeal constrictor muscle activity in decerebrate cats. J Appl Physiol. 1997;83:1588–1594. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1997.83.5.1588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lide DR. CRC Handbook of Chemistry and Physics: A Ready Reference Book of Chemical and Physical Data. 2001. CRC Press, Boca Raton, FL, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Mathew OP. Upper airway negative-pressure effects on respiratory activity of upper airway muscles. J Appl Physiol. 1984;56:500–505. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1984.56.2.500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathew OP, Abu-Osba YK, Thach BT. Influence of upper airway pressure changes on genioglossus muscle respiratory activity. J Appl Physiol. 1982a;52:438–444. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1982.52.2.438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathew OP, Abu-Osba YK, Thach BT. Genioglossus muscle responses to upper airway pressure changes: afferent pathways. J Appl Physiol. 1982b;52:445–450. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1982.52.2.445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miki H, Hida W, Kikuchi Y, Chonan T, Satoh M, Iwase N, Takishima T. Effects of pharyngeal lubrication on the opening of obstructed upper airway. J Appl Physiol. 1992;72:2311–2316. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1992.72.6.2311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olson LG, Strohl KP. Airway secretions influence upper airway patency in the rabbit. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1988a;137:1379–1381. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/137.6.1379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olson LG, Strohl KP. Non-muscular factors in upper airway patency in the rabbit. Respir Physiol. 1988b;71:147–155. doi: 10.1016/0034-5687(88)90012-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olson LG, Ulmer LG, Saunders NA. Influence of muscle activity on the elastance of the upper airway of rabbits. J Appl Physiol. 1989;66:755–758. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1989.66.2.755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rahmoune H, Shephard KL. Regulation of airway surface liquid on the isolated guinea-pig trachea. Pulm Pharmacol. 1994;7:265–269. doi: 10.1006/pulp.1994.1030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Remmers JE, deGroot WJ, Sauerland EK, Anch AM. Pathogenesis of upper airway occlusion during sleep. J Appl Physiol. 1978;44:931–938. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1978.44.6.931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rothstein RJ, Narce SL, deBerry-Borowiecki B, Blanks RH. Respiratory-related activity of upper airway muscles in anesthetized rabbit. J Appl Physiol. 1983;55:1830–1836. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1983.55.6.1830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scarpelli EM, David E, Cordova M, Mautone AJ. Surface tension of therapeutic surfactants (exosurf neonatal, infasurf, and survanta) as evaluated by standard methods and criteria (see comments) Am J Perinatol. 1992;9:414–419. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-999278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schurch S. Surface tension properties of surfactant. Clin Perinatol. 1993;20:669–682. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwab RJ, Gupta KB, Gefter WB, Metzger LJ, Hoffman EA, Pack AI. Upper airway and soft tissue anatomy in normal subjects and patients with sleep-disordered breathing. Significance of the lateral pharyngeal walls. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1995;152:1673–1689. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.152.5.7582313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strohl KP, Wolin AD, van Lunteren E, Fouke JM. Assessment of muscle action on upper airway stability in anesthetized dogs. J Lab Clin Med. 1987;110:221–230. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van der Touw T, Crawford AB, Wheatley JR. Effects of a synthetic lung surfactant on pharyngeal patency in awake human subjects. J Appl Physiol. 1997;82:78–85. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1997.82.1.78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Lunteren E, Manubay P. Contractile properties of feline genioglossus, sternohyoid, and sternothyroid muscles. J Appl Physiol. 1992;72:1010–1015. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1992.72.3.1010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vassilakos N, Arnebrant T, Rundegren J, Glantz PO. In vitro interactions of anionic and cationic surfactants with salivary fractions on well-defined solid surfaces. Acta Odontol Scand. 1992;50:179–188. doi: 10.3109/00016359209012761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Widdicombe JG, Davies A. The effects of a mixture of surface-active agents (Sonarex) on upper airways resistance and snoring in anaesthetized dogs. Eur Respir J. 1988;1:785–791. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiegand DA, Latz B. Effect of geniohyoid and sternohyoid muscle contraction on upper airway resistance in the cat. J Appl Physiol. 1991;71:1346–1354. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1991.71.4.1346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson SL, Thach BT, Brouillette RT, Abu-Osba YK. Upper airway patency in the human infant: influence of airway pressure and posture. J Appl Physiol. 1980;48:500–504. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1980.48.3.500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winter WC, Gampper T, Gay SB, Suratt PM. Lateral pharyngeal fat pad pressure during breathing. Sleep. 1996;19:S178–S179. doi: 10.1093/sleep/19.suppl_10.178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winter WC, Gampper T, Gay SB, Suratt PM. Lateral pharyngeal fat pad pressure during breathing in anesthetized pigs. J Appl Physiol. 1997;83:688–694. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1997.83.3.688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woodall DL, Hokanson JA, Mathew OP. Time of application of negative pressure pulses and upper airway muscle activity. J Appl Physiol. 1989;67:366–370. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1989.67.1.366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]