Abstract

In colitis, chronic and recurrent inflammation is associated with a breakdown in host defence mechanisms that leads to local and systemic infection. Whether this is due to a compromised neuroimmune response has not been studied. Our aim was to determine if colitis altered the host neuroimmune response as reflected in either body temperature rhythm or the febrile responses to lipopolysaccharide (LPS). Body temperature was monitored by telemetry from conscious, unrestrained male rats treated with trinitrobenzene sulphonic acid or saline. Twenty-six days after initial induction, colitis was reactivated. Animals were given LPS (50 μg kg−1Escherichia coli LPS) during colitis and after reactivation. At the peak of colitis, treated rats showed a disruption of circadian body temperature rhythm, manifested as day-time fever followed by night-time hypothermia. In response to LPS, controls displayed a characteristic fever, whereas treated animals had a significantly reduced fever and low plasma levels of interleukin-6 (IL-6) and tumour necrosis factor-α (TNF-α). During reactivation of colitis, treated animals did not mount a fever or exhibit increased plasma levels of IL-6 and TNF-α after LPS. We conclude that experimental colitis is associated with a compromised neuroimmune status.

Fever is an important component of the acute phase response to infection (Baumann & Gauldie, 1994). An increase in core temperature is thought to make the body an unwelcome locus for invading pathogens, through enhancement of specific and non-specific immunity (Kluger et al. 1990). Animals that do not mount a fever in response to pathogenic invasion have a higher mortality rate than do their febrile counterparts (Kluger et al. 1975, 1998).

Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) is a relapsing and remitting condition characterized by chronic intestinal inflammation associated with alterations in intestinal structure and function (Fiocchi, 1998). There is compelling evidence to support the involvement of bacterial flora in triggering, initiating and/or maintaining the state of inflammation (Garcia-Lafuente et al. 1997; Rath et al. 2001). Immune-mediated events, involving inappropriate activity of T cells, are important in IBD and play a role in the re-activation of the condition (Fiocchi, 1998; Qiu et al. 1999). Fever is not a major feature in patients presenting with IBD (Mekhjian et al. 1979), but this important component of host defence has not been extensively studied in animal models of intestinal inflammation. In a single report, Larson et al. (1996) described a dissociation of fever and anorexia in experimental colitis, reporting a mild hypothermia during the initial development of colitis, and no change in body temperature 2 days after induction.

The increased mucosal permeability associated with colitis (Hollander et al. 1986; Fiocchi, 1998) permits bacterial translocation leading to endotoxaemia (Neilly et al. 1995) and the presence of bacteria in normally undisturbed tissues (Asfaha et al. 2001). While intestinal flora have been implicated in the maintenance of normal body temperature (Kluger et al. 1990), abnormal infiltration of these pathogens over a period of time might result in chronic activation of host defence responses. One potential consequence of this chronic activation could be a suppressed ability to mount an additional response to secondary infection, characterized by a suppression of fever. In support of this are findings that demonstrate that there is a reduced febrile response upon repeated stimulation with tumour necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) (Goldbach et al. 1996; Zeisberger & Roth, 1998) or lipopolysaccharide (LPS) (West & Heagy, 2002). We hypothesize that repeated episodes of colitis predispose rats to a reduced fever in response to LPS challenge. The aim of this study was to examine whether or not colitis is associated with changes in body temperature regulation and if animals with colitis are able to mount a fever in response to LPS. We were able to test this hypothesis using a well-characterized experimental model of trinitrobenzene sulphonic acid (TNBS)-induced colitis (Morris et al. 1989; Appleyard & Wallace, 1995), which displays features of both an initial and a recurring, hapten-mediated, inflammation typical of human colitis.

METHODS

Animals

Male Sprague-Dawley rats (250–275 g) bred at the University of Calgary Biological Sciences facilities were housed in a temperature-controlled room under a normal 12 h:12 h light- dark cycle (lights on at 08:00 h). Animals were individually housed after surgery, and rat chow and water were available ad libitum. They were monitored daily to ensure overall health and recovery from the acute effects of the colitis. All experimental protocols were approved by the University of Calgary Animal Care Committee and were carried out in accordance with the guidelines of the Canadian Council on Animal Care.

Experimental protocols

Our initial studies were done to measure body temperature during colitis. These experiments were carried out twice in separate groups of control (n = 7) and TNBS-treated (n = 9) animals whose temperature and activity measurements were taken over 24 h for 3 days before the induction of colitis, and daily thereafter for 30 days. Sixteen days after colitis was induced, animals were administered LPS in order to elicit fevers. On days 26–28 after induction, an acute episode of colitis was reactivated as described below. Temperature and activity were measured during reactivation and a second injection of LPS was given on day 29. Rats were killed by an overdose of sodium pentobarbital given i.p. at the end of the study on day 30 after induction of colitis.

In a second series of studies, animals (n = 10 control, n = 10 TNBS) were treated as above, but did not receive an injection of LPS on day 16, to avoid any potential for LPS tolerance when given LPS injections on day 29 after induction of colitis.

In the third series of studies, three separate groups of control and TNBS-treated rats were assessed for the severity of colitis and plasma levels of the cytokines TNF-α and interleukin-6 (IL-6). Animals were killed as above on day 3 to determine basal cytokine levels during acute colitis (n = 6 control, n = 6 TNBS), on day 16 after LPS administration (n = 7 control, n = 5 TNBS) and on day 29 after LPS administration (n = 7 control, n = 5 TNBS). Macroscopic damage score was determined in each animal to assess the severity of colitis and samples of colon were collected for myeloperoxidase (MPO) assay to assess granulocyte infiltration, as described below.

Surgery and data acquisition

Rats were anaesthetized with sodium pentobarbital (65 mg kg−1, i.p.), and a sterile, wax-coated, pre-calibrated mini temperature transmitter (Model VMFH, Mini-Mitter, Sunriver, OR, USA) was implanted into the abdominal cavity. After a 5 day recovery period, animals were transferred to a temperature-controlled testing room and body temperatures and activity were recorded via telemetry plates under the rats' home cages. The transmitted radio frequency was received by the plate, and directed to an on-line data acquisition system (DataQuest II, Data Sciences, St Paul, MN, USA) and converted to body temperature. Data were recorded every 5 min, for 24 h a day for the duration of the study periods. These transmitters also record activity data, which was collected by telemetry in some animals and recorded as the number of gross motor movements made as the animal moves throughout the cage every 5 min. The activity levels of a number of these 5 min epochs were then averaged over 1–6 h periods (according to the need) to give an average activity level over that time period. In each series of experiments, there was some transmitter failure, leading to drop out of up to three animals per group. Actual numbers of data points are given in the figure legends for each group.

Induction and assessment of colitis

Colitis was induced by intracolonic administration of TNBS (0.5 ml of 50 mg ml−1 in 50 % (v/v) ethanol) under halothane anaesthesia (2–4 % in oxygen). TNBS was instilled into the lumen of the colon through a plastic cannula with a perforated tip, ∼8 cm from the anus (Morris et al. 1989; McCafferty et al. 1997). Control animals received an equal volume of sterile 0.9 % saline. Animals were weighed daily, as weight loss and anorexia are correlated with increases in severity of colitis (Morris et al. 1989). Beginning on day 26, all animals received subcutaneous injection of 10 mg kg−1 TNBS diluted in saline every 12 h for 3 days, as previously described (Appleyard & Wallace, 1995). With this treatment we were able to compare responses in animals with acute colitic damage (TNBS and ethanol) with animals having no damage (0.9 % saline). In addition, the subcutaneous administration of TNBS to both groups can be expected to activate an immune-mediated colitis in only those animals pretreated with the intra-colonic TNBS at the earlier date.

In the third series of studies, described above, on days 3, 16 and 29 after induction of colitis, rats were anaesthetized with halothane (2–4 % in oxygen) to enable blood collection (see below), then killed, while anaesthetized, by cervical dislocation. Colonic tissue from the site of inflammation or an equivalent position in the control was taken for MPO assay, and the macroscopic severity of colitis was assessed as described previously (McCafferty et al. 1997). Briefly, an individual, blind to the experimental condition, scored each distal colon on the basis of adhesions, diarrhoea and degree of ulceration to arrive at a summated number whereby the severity of the colitis is reflected by a larger number. MPO is a constituent of the granules of neutrophils and its presence is reflective of recruitment of granulocytes to the site of inflammation. MPO activity is expressed in units (mg wet weight of tissue)−1.

LPS challenge

Fever was induced on days 16 (in the first and third series) and 29 (in all animals) by administration of LPS (E. coli, serotype 026:B6, Sigma Chemicals, St Louis, MO, USA; 50 μg kg i.p.), at a dose found to reliably induce fever in previous experiments (McCullough et al. 2000; Martin et al. 2000).

Plasma levels of IL-6 and TNF-α

Blood was collected in heparin-coated syringes by cardiac puncture from anaesthetized rats (halothane, 2–4 % in oxygen), which were then killed, while anaesthetized, by cervical dislocation. Samples were collected from treated and control rats 3, 16 and 29 days after colitis was induced. On days 16 and 29, both treated and control rats were given an injection of LPS in order to determine differences in LPS-induced plasma cytokine levels between control and colitic rats. Blood collected 2 h after the injection of LPS was cooled (in ice), centrifuged, and plasma was collected and frozen at -70 °C for no longer than 2 months until assay. Plasma TNF-α and IL-6 were analysed by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay for rat cytokines (BioSource, Camarillo, CA, USA). As described by the supplier, these assays show no cross-reactivity with other cytokines. The TNF-α assay has a sensitivity of < 4 pg ml−1 and interassay variability is < 4.3 %; the IL-6 assay has a sensitivity of < 8 pg ml−1 and interassay variability is < 10 %.

Statistics

Data for body temperature are presented as means ±s.e.m. Kruskal-Wallis one-way ANOVAs for ranks were performed on temperature and cytokine data, and Dunnett's test was used for post hoc analysis. Data for activity, MPO assays and macroscopic damage scores are presented as an ANOVA, and the Tukey test was used for post hoc analysis. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

General observations

Colitic rats displayed behaviours characteristic of acute experimental colitis, such as piloerection, and had an unkempt appearance. They lost weight over the first 3 days after treatment and had diarrhoea (Fig. 1A). After this, they gained weight at a similar rate to controls and regained a healthy coat, although their body weights remained lower over the course of the study. We considered that the day of peak of acute inflammation occurs on the third day after induction of colitis, as this is around the nadir of body weight. At this time point we obtained initial macroscopic damage scores and measured MPO activity, and, in other rats, determined these indices of inflammation during the chronic phase of colitis (day 16) and after the reactivation of an acute episode on day 29 (Fig. 1B and C).

Figure 1. Pathophysiological changes in TNBC colitis.

A, body weight (means ±s.e.m.) of rats treated on day 0 with trinitrobenzene sulphonic acid (TNBS; continuous line) or 0.9 % saline (Control, dashed line) intracolonically. On days 26–28, both groups received subcutaneous injections of TNBS every 12 h for the reactivation of colitis. B, macroscopic damage scores (means ±s.e.m.) 3 or 16 days after male rats were treated with intracolonic TNBS at day 0 (black bars, n = 5) or with 0.9 % saline (open bars, n = 6–7). Other rats were similarly treated at day 0 with TNBS (grey bars) or saline (hatched bars), but then all received subcutaneous injections of TNBS as described in the Methods. At all time points the treated animals had significantly greater damage than the corresponding control group (*P < 0.05). C, myeloperoxidase (MPO) activity present in colon tissue of male rats treated with TNBS at day 0 (black bars, n = 5) or with 0.9 % saline (open bars, n = 6–7), or after reactivation with TNBS after prior intracolonic TNBS (grey bars) or saline (hatched bars). At all time points the treated animals had significantly greater MPO activity than the corresponding control group (*P < 0.05).

At all time points during the study, control rats had a normal colon with no evidence of damage, while colitic rats had significant damage scores when measured on days 3, 16 and 29 (Fig. 1B, P < 0.05). Rats with colitis had the highest macroscopic damage score on day 3, and these were reduced at day 16. Furthermore, the features of the damage at this stage were altered such that the contribution of colonic thickening to the damage score was greater than at day 3 when acute features of the colitis dominated. Previous work has shown that the damage scores and MPO activity of rats are reduced after this point towards control levels unless colitis is reactivated (Appleyard & Wallace, 1995). In our study, the damage scores of the reactivated rats treated with TNBS were comparable to those seen previously (Appleyard & Wallace, 1995). In saline-treated controls, subcutaneous TNBS injection produced no discernable macroscopic damage, as also previously demonstrated.

At all time points in the study, control rats had consistently low tissue levels of MPO (Fig. 1C), whether or not they had been injected with TNBS subcutaneously. Rats treated intracolonically with TNBS had significantly higher levels of tissue MPO on days 3, 16 and 29 than did control rats (P < 0.05). While levels of MPO in colon tissue were not different on days 3 and 16 (P > 0.05), there were lower, although still elevated above control, tissue levels of MPO on day 29.

Effects of colitis on activity levels

Prior to induction of colitis, all animals were active during the dark phase, as would be expected of nocturnal animals (Fig. 2A). After induction of colitis, the night-time activity levels of treated rats began to decline, until the difference between treated and control rats reached statistical significance on day 3 (Fig. 2B, P < 0.05). These results coincide with the nadir in body weight, high clinical damage scores and elevated MPO levels. As a result of the relative inactivity during the dark phase, the treated rats maintained nearly the same level of activity during the entire 24 h cycle. This atypical pattern of activity slowly resolved, until it was no longer apparent on day 10 (Fig. 2C).

Figure 2. Activity levels over 24 h of rats treated with TNBS (n = 4) or 0.9 % saline (control, n = 4) intracolonically.

A, baseline activity levels measured before treatment. B, activity levels measured 3 days after treatment with TNBS (black bars) or saline (open bars). C, activity levels 10 days after initial TNBS treatment. Activity levels at night were reduced in animals with acute colitis as shown in B. Means ±s.e.m.*P < 0.05, with respect to corresponding control group. The n values for activity were different from those for body temperature, as activity was not recorded in all animals.

Effects of colitis on circadian body temperature

Baseline circadian body temperatures were similar for both groups of rats before treatment with TNBS or saline (Fig. 3A). Throughout the experiment, control rats demonstrated normal circadian body temperature rhythm. Rats have lower body temperatures during the day and an elevation at night coinciding with increased activity (Fig. 3A). Inflamed rats demonstrated a disruption in normal thermoregulation that became particularly pronounced on the third day after induction of colitis (Fig. 3B). During the day, they exhibited a mild fever of ∼0.3–0.5 °C (P < 0.05), while they displayed night-time hypothermia of similar magnitude (P < 0.05). Differences in circadian body temperature in inflamed rats slowly resolved until day 10, when temperature rhythms returned to pre-inflammation values (Fig. 3C).

Figure 3. Body temperature responses over 24 h in rats treated with TNBS (n = 15–19) or 0.9 % saline (control, n = 17) intracolonically.

A, body temperature measured before treatment. B, body temperature measured 3 days after treatment with TNBS (continuous lines) or saline (dashed lines). During the day, rats exhibited a low-grade fever of ∼0.3–0.5 °C (P < 0.05), while they displayed night-time hypothermia of ∼0.2 °C (P < 0.05). C, body temperature 10 days after treatment. Means ±s.e.m. Bar indicates lights out.

Effect of LPS during colitis

Sixteen days after the induction of colitis, when the acute effects of TNBS administration had subsided (such as diarrhoea, weight loss and circadian temperature rhythm disruption) we administered LPS to both treated and control animals from the first series of experiments. Baseline temperatures before injection of LPS were the same in both groups (P > 0.05), whereas fevers were different between the two groups (P < 0.05). While control animals displayed a classical biphasic fever (Fig. 4A), the TNBS-treated rats displayed a significantly reduced fever in response to LPS between 5.5 and 8 h after injection (P < 0.05).

Figure 4. Responses to i.p. injection of lipopolysaccharide (LPS, 50 μg kg-1) 16 days after intracolonic administration of TNBS (n = 6) or 0.9 % saline (control, n = 7).

A, body temperature changes (means ±s.e.m.) from baseline (which was identical in both groups). In control animals a biphasic fever was observed, which was significantly reduced in animals treated with TNBS (P < 0.05 between 5.5 and 8 h). The first phase occurred 4 h, and the second phase 6–7 h, after LPS injection. B, activity level responses (means ±s.e.m., n = 4 for each group). *P < 0.05, with respect to activity at other time points shown. There was no difference in the extent of the reduced activity in the two groups of rats.

After injection of LPS on day 16, the activity levels of both groups of animals were reduced to the same extent (P > 0.05) for about 3 h (Fig. 4B). After this, activity returned to control levels.

Effect of reactivation of colitis on circadian body temperature

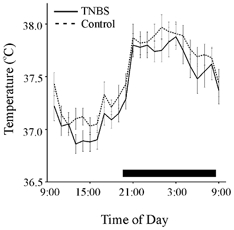

Colitis was reactivated with subcutaneous TNBS in animals previously treated with an intracolonic infusion of TNBS. These animals had elevated macroscopic damage scores (Fig. 1B) and MPO activity (Fig. 1C). In contrast to the initial induction of colitis, during the reactivation of colitis, there was no difference between the body temperatures of treated and control rats (Fig. 5, P > 0.05). There was also no difference in activity levels in the two groups (data not shown).

Figure 5. Body temperature responses over 24 h to subcutaneous injections of TNBS 28 days after intracolonic administration of TNBS or 0.9 % saline.

Means ±s.e.m. TNBS, continuous line (n = 16); saline (control), dashed line (n = 16). Bar indicates lights out. The value of n for these groups is lower than for the initial studies (Fig. 3) as a result of transmitter failure during the study. There were no significant differences between the two groups.

Effects of LPS during reactivated colitis

To determine whether or not reactivated colitis was associated with a reduced febrile response, all rats were given LPS on day 29 after 3 days of reactivation. While the control rats developed robust fevers, treated rats displayed a suppressed febrile response between 3.5 and 8.5 h after injection (Fig. 6, P < 0.05). Because the differences in febrile response as a result of colitis were so dramatic, we repeated the experiment to determine if the difference in febrile responses were a result of tolerance arising from the previous injection of LPS (Roth et al. 1994; Zeisberger & Roth, 1998), or were due to other factors, such as bacterial translocation due to altered intestinal permeability in the colitic rats. Thus, in the first series of experiments, all rats were given LPS on days 16 and 29. In contrast, in the second series of experiments, rats were only given LPS on day 29, and not on day 16. As the lack of fever occurred regardless of the number of times LPS was administered, and in separate groups of animals, we conclude that fever was attenuated as a result of colitis, and not as a result of tolerance to exogenous LPS injection or a unique circumstance in one group of animals. Activity levels declined in both groups during the fever and were identical in the two groups at this time as previously shown in Fig. 4B (data not shown).

Figure 6. Body temperature changes in response to i.p. injection of LPS (50 μg kg−1), after the reactivation of colitis in rats that received intracolonic TNBS or 0.9 % saline.

Means ±s.e.m. TNBS, continuous line (n = 14); saline (control), dashed line (n = 10). The value of n for these groups is lower than for the initial studies (Fig. 3) as a result of transmitter failure during the study. There was a significant elevation in temperature after LPS in control, but not in TNBS-treated rats, such that temperatures were significantly different (P < 0.05) from 3.5 to 8.5 h after injection.

Plasma IL-6 and TNF-α

In order to determine a possible mechanism to account for the fever suppression during colitis, we assayed serum IL-6 and TNF-α. Three days after the induction of colitis, plasma levels of IL-6 were undetectable and TNF-α levels were very low in both groups (Fig. 7A and B).

Figure 7. Plasma levels of TNF-α (A) and IL-6 (B) in TNBS-treated and control rats.

Cytokine levels were determined on day 3 during acute colitis (n = 6 control, n = 6 TNBS), on day 16 after LPS administration (n = 7 control, n = 5 TNBS) and on day 29 after LPS administration (n = 7 control, n = 5 TNBS). TNBS-treated rats showed no significant elevation in plasma cytokines after LPS injection. In control rats there was a significant (P < 0.05) increase in TNF-α and IL-6 levels in response to LPS injection on day 29 and a trend towards significance at day 16.

In control rats, there was a significant increase in plasma levels of both IL-6 and TNF-α from baseline (day 3) to the febrile state after LPS on day 29 (Fig. 7, P < 0.05), although this difference was not present between baseline and day 16 for either cytokine (P > 0.05), even though all animals had received LPS injection at this time. It is not clear why the control rats differed in their responses at days 16 and 29. In marked contrast, plasma levels of IL-6 and TNF-α did not increase in response to LPS in the colitic rats between baseline and day 16, or between baseline and reactivation on day 29 (Fig. 7).

DISCUSSION

In this study we have demonstrated that thermoregulation and activity are altered in experimental colitis and that fever in response LPS is reduced in colitic rats. We also propose that it is a decrease in levels of circulating endogenous pyrogens in response to LPS that is responsible for the reduced fever.

The cytokines IL-6 and TNF-α have been implicated in the aetiology of IBD (Fiocchi, 1998; Monteleone & MacDonald, 2000) and are endogenous pyrogens (Luheshi & Rothwell, 1996). Levels of TNF-α are higher in colonic tissue taken from colitic rats than from untreated rats, and are decreased in response to TNF-α synthesis inhibitors (Bobin-Dubigeon et al. 2001). In TNBS colitis, plasma TNF-α levels have not been reported to be elevated (Neilly et al. 1995), as we found in our study, although increases in plasma TNF-α have been reported in other models of colitis in the rat (Karmeli et al. 2000). Nevertheless, TNF-α plays an important role in the pathogenesis of IBD as shown in recent clinical studies examining the potential of TNF-α suppressors (Bauditz et al. 2002) and anti-TNF-α neutralizing antibodies (van Dullemen et al. 1998) in reducing the inflammation in patients.

IBD is associated with a T helper cell-1 (Th-1)-mediated response (Fuss et al. 1999; Monteleone et al. 1999), and the cytokine IL-6 is required in order for this response to develop (Yamamoto et al. 2000). In addition, IL-6 is also present in high levels both in serum and intestine of patients with IBD (Gross et al. 1992). In colitis induced by TNBS in SJL/J mice, plasma IL-6 levels have been reported to increase (Franchimont et al. 2000), as they have in the rat (Ballinger et al. 2000). The levels reported in the rat (about 400 pg ml−1) are similar to those observed in some animals in our study after LPS administration. It is not clear why our study did not reveal elevated IL-6 under basal conditions in inflamed animals.

Body temperature during colitis

During the peak of inflammation, the normal circadian rhythm of the rats was abolished, such that differences in body temperature and activity during the light-dark cycle were not seen at the peak of inflammation. We do not have an explanation for this, but several possibilities can be considered. As there was no difference between measured levels of plasma cytokines between colitic and control rats 3 days after colitis was induced, we can assume that cytokines do not play a significant role in the day-time hyperthermia seen at this time point. As we did not sample plasma levels during the dark phase of the cycle, at which time colitic rats were hypothermic relative to controls, we cannot rule out possible elevated levels at this time. There is evidence that TNF-α at high levels can cause hypothermia (Tollner et al. 2000). However, given the chronic activation of the colitis at this time, one might think it is unlikely that there would be a transient elevation of a cytokine only during the dark phase of the cycle. Similarly, possible suppressors of cytokines such as corticosterone appear to be secreted continuously in chronically stressed animals (Owens & Nemeroff, 1993), including colitic rats (Kojima et al. 2002) and mice (Franchimont et al. 2000) making it unlikely that this would reduce body temperature only at night-time.

It is also possible that the inactivity brought about by the colitis could account for the relative hypothermia during the dark phase; however, although changes in activity can affect body temperature, there is general agreement that the circadian rhythm of body temperature is not a result of the circadian rhythm in activity (Refinetti & Menaker, 1992). Furthermore, even forced activity has little effect on circadian temperature rhythms (Strijkstra et al. 1999). Thus we believe that the night-time hypothermia displayed by the rats undergoing acute colitis cannot be explained by the reduced activity levels.

A possible mechanism for both the altered thermoregulation and the reduced activity in the absence of increases in circulating cytokines could be through activation by local cytokines or other mediators of vagal or spinal afferents (Bret-Dibat et al. 1994; Layéet al. 1995; Maier et al. 1998; Ross et al. 2000). It is also known that colitic rats display a marked weight loss that is associated with anorexia (Larson et al. 1996). Perhaps the hypothermia seen on day 3 is as a result of this anorexia, as reduced nutrient intake is associated with a regulated reduction in body temperature (Leon et al. 1998; Szekely, 2000). Indeed, significantly reduced food intake has been reported throughout days 1 to 4 in this model of colitis (Kojima et al. 2002).

In the TNBS model of colitis, there is a chronic inflammation of the colon and it might be argued that this would create an anomalous elevation of local temperature (heat being one of the cardinal signs of inflammation) as recorded by the intraperitoneal thermistors that we employed. The fact that hypothermia was observed throughout the dark phase of the circadian rhythm suggests that this is not the case.

Another possibility is that the neuronal oscillators responsible for the circadian activity patterns may have been targeted by the colitic inflammation. For example, some types of parasitic infections are associated with disruptions of circadian rhythmicity (Grassi-Zucconi et al. 1995) and this is reflected in altered c-Fos expression in the suprachiasmatic nucleus (Peng et al. 1994). In this respect, it would be interesting to determine if the normal activity patterns of the suprachiasmatic nucleus were altered during TNBS-induced colitis. This may be of importance either from a diagnostic or a symptomatic point of view as people with IBD may have co-presenting depression, a disease associated with disruption of circadian rhythms.

LPS fever

Following the resolution of acute colitis, we administered LPS to treated and control rats in order to elicit a fever. As expected, the control rats developed a typical fever, whereas the treated rats responded with a reduced fever. This reduced response became even more dramatic upon reactivation of the colitis when there was almost a totally absent febrile response. On day 16, though fever was reduced in the TNBS-treated rats, activity was reduced to comparable levels in both groups. These results suggest dissociation between sickness behaviour and fever induced by LPS during colitis. Even though treated rats displayed the same decrease in activity in response to LPS injection as did untreated, control rats, they did not mount the same fever.

An interesting feature of the reduced fever in the colitic rats on day 16 is the fact that these animals display an initial, or first phase of fever, but then fail to mount a subsequent increase in temperature such as exhibited by the control animals. It is well known that LPS fever consists of several phases in the rat (Romanovsky et al. 1997). While the first phase is probably prostaglandin dependent, the mediators of the later phase(s) of the febrile response are yet unidentified (Romanovsky & Blatteis, 1995). Thus it appears that there is a differential effect of the pre-existing colitis upon the later phase(s) of the fever. It is interesting that the febrile response during the reactivation of the colitis is even more suppressed, with a less obvious first phase of fever. This indicates that there are different, or more severe consequences, of the reactivation of colitis upon fever than are seen after colitis is first induced.

We considered the possibility that the reduced response to LPS in these colitic animals was associated with less cytokine induction. To test this, we measured circulating IL-6 and TNF-α after LPS. These pro-inflammatory cytokines are important both in the development of fever (Dinarello et al. 1986; LeMay et al. 1990; Cartmell et al. 2000), and in the pathogenesis of IBD (Yamamoto et al. 2000; Bobin-Dubigeon et al. 2001; Ten Hove et al. 2001; Mizoguchi et al. 2002). Both plasma IL-6 and TNF-α increased in control animals. In contrast, there was an almost complete lack of any induction of either cytokine in the TNBS-treated animals on either day 16 (chronic colitis) or day 29 (after acute reactivation of colitis). The mechanisms responsible for the reduced cytokine response have not yet been elucidated, but could be due to alterations in the cellular population of macrophages that normally respond to LPS, alterations in the Toll-like receptor 4 and/or CD-14 receptors which bind the LPS (Zhang & Ghosh, 2000) or elaboration of immunosuppressive factors such as PGJ2 (Jiang et al. 1998; Ricote et al. 1998) which alter the macrophage response.

It has previously been reported that bacterial translocation is a feature of TNBS colitis (Asfaha et al. 2001). The diminished or altered response of the macrophages to LPS could be brought about subsequent to the chronic exposure to bacterial endotoxin associated with the colitis. Alternatively, the chronic inflammation in the gut may activate the central nervous system and cause a centrally directed inhibition of the inflammatory response (MacNeil et al. 1996).

While these dramatic reductions in cytokine levels probably account for the suppressed fever, there may also be changes in the central nervous system pathway involved in the febrile response. One key mediator in this pathway is the hormone, corticotrophin releasing hormone (CRH), which also acts centrally to elevate sympathetic tone and body temperature (Luheshi & Rothwell, 1996). CRH mRNA levels have been previously measured during experimental colitis in rats and, in the paraventricular nucleus, have been reported at various times after the induction of colitis to be suppressed in the parvocellular division of this nucleus 3 and 7 days after the induction of colitis (Kojima et al. 2002) and elevated in the magnocellular division at 7 days (Kresse et al. 2001). However, these changes could be secondary to the alteration in peripheral cytokines that we report in this study. We also are aware that, during peripheral inflammation, there may be synthesis of cytokines in the CNS and these have been implicated in both fever and sickness behaviour (Kent et al. 1992). In addition to the peripheral changes we have measured, there may also be changes in the levels of these central cytokines that could contribute to the changes we have observed.

In conclusion, we have found that colitis alters body temperature regulation, and decreases fever in response to LPS. Because fever is an important part of the host defence response (Kluger et al. 1975), an individual suffering from IBD could be compromised in their ability to combat secondary infection. Indeed, extra-intestinal manifestations of IBD include upper respiratory tract infections (Gionchetti et al. 1990; Kangro et al. 1990; Ruther et al. 1998), and a number of systemic immune diseases (Bernstein et al. 2001) suggesting that individuals suffering from IBD are at a significant immunological disadvantage. Similar findings of reduced febrile responses in a rat model of cholestasis (McCullough et al. 2000) raise the possibility that many chronic gastrointestinal illnesses may be associated with an impaired host defence response.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (to Q.J.P.) and the Crohn's and Colitis Foundation of Canada (to K.A.S.). K.A.S. and Q.J.P. are Alberta Heritage Foundation for Medical Research (AHFMR) Medical Scientists, and L.B. and M.D.V.S. are funded by AHFMR Studentships. Very special thanks to Cathy MacNaughton for her assistance with colonic scoring, MPO and ELISA assays.

REFERENCES

- Appleyard CB, Wallace JL. Reactivation of hapten-induced colitis and its prevention by anti-inflammatory drugs. Am J Physiol. 1995;269:G119–125. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1995.269.1.G119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asfaha S, MacNaughton WK, Appleyard CB, Chadee K, Wallace JL. Persistent epithelial dysfunction and bacterial translocation after resolution of intestinal inflammation. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2001;281:G635–644. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.2001.281.3.G635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ballinger AB, Azooz O, El Haj T, Poole S, Farthing MJ. Growth failure occurs through a decrease in insulin-like growth factor 1 which is independent of undernutrition in a rat model of colitis. Gut. 2000;46:694–700. doi: 10.1136/gut.46.5.695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauditz J, Wedel S, Lochs H. Thalidomide reduces tumour necrosis factor alpha and interleukin 12 production in patients with chronic active Crohn's disease. Gut. 2002;50:196–200. doi: 10.1136/gut.50.2.196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baumann H, Gauldie J. The acute phase response. Immunol Today. 1994;15:74–80. doi: 10.1016/0167-5699(94)90137-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernstein CN, Blanchard JF, Rawsthorne P, Yu N. The prevalence of extraintestinal diseases in inflammatory bowel disease: a population-based study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96:1116–1122. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2001.03756.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bobin-Dubigeon C, Collin X, Grimaud N, Robert JM, Le Baut G, Petit JY. Effects of tumour necrosis factor-alpha synthesis inhibitors on rat trinitrobenzene sulphonic acid-induced chronic colitis. Eur J Pharmacol. 2001;431:103–110. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(01)01410-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bret-Dibat JL, Kent S, Couraud JY, Creminon C, Dantzer R. A behaviorally active dose of lipopolysaccharide increases sensory neuropeptides levels in mouse spinal cord. Neurosci Lett. 1994;173:205–209. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(94)90184-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cartmell T, Poole S, Turnbull AV, Rothwell NJ, Luheshi GN. Circulating interleukin-6 mediates the febrile response to localised inflammation in rats. J Physiol. 2000;526:653–661. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2000.00653.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dinarello CA, Cannon JG, Wolff SM, Bernheim HA, Beutler B, Cerami A, Figari IS, Palladino MA, Jr, O'Connor JV. Tumor necrosis factor (cachectin) is an endogenous pyrogen and induces production of interleukin 1. J Exp Med. 1986;163:1433–1450. doi: 10.1084/jem.163.6.1433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiocchi C. Inflammatory bowel disease: etiology and pathogenesis. Gastroenterology. 1998;115:182–205. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(98)70381-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franchimont D, Bouma G, Galon J, Wolkersdorfer GW, Haidan A, Chrousos GP, Bornstein SR. Adrenal cortical activation in murine colitis. Gastroenterology. 2000;119:1560–1568. doi: 10.1053/gast.2000.20235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuss IJ, Marth T, Neurath MF, Pearlstein GR, Jain A, Strober W. Anti-interleukin 12 treatment regulates apoptosis of Th1 T cells in experimental colitis in mice. Gastroenterology. 1999;117:1078–1088. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(99)70392-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Lafuente A, Antolin M, Guarner F, Crespo E, Salas A, Forcada P, Laguarda M, Gavalda J, Baena JA, Vilaseca J, Malagelada JR. Incrimination of anaerobic bacteria in the induction of experimental colitis. Am J Physiol. 1997;272:G10–15. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1997.272.1.G10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gionchetti P, Schiavina M, Campieri M, Fabiani A, Cornia BM, Belluzzi A, Brignola C, Iannone P, Miglioli M, Barbara L. Bronchopulmonary involvement in ulcerative colitis. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1990;12:647–650. doi: 10.1097/00004836-199012000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldbach JM, Roth J, Storr B, Zeisberger E. Repeated infusions of TNF-alpha cause attenuation of the thermal response and influence LPS fever in guinea pigs. Am J Physiol. 1996;270:R749–754. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1996.270.4.R749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grassi-Zucconi G, Harris JA, Mohammed AH, Ambrosini MV, Kristensson K, Bentivoglio M. Sleep fragmentation, and changes in locomotor activity and body temperature in trypanosome-infected rats. Brain Res Bull. 1995;37:123–129. doi: 10.1016/0361-9230(94)00265-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gross V, Andus T, Caesar I, Roth M, Scholmerich J. Evidence for continuous stimulation of interleukin-6 production in Crohn's disease. Gastroenterology. 1992;102:514–519. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(92)90098-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hollander D, Vadheim CM, Brettholz E, Petersen GM, Delahunty T, Rotter JI. Increased intestinal permeability in patients with Crohn's disease and their relatives. A possible etiologic factor. Ann Intern Med. 1986;105:883–885. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-105-6-883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang C, Ting AT, Seed B. PPAR-gamma agonists inhibit production of monocyte inflammatory cytokines. Nature. 1998;391:82–86. doi: 10.1038/34184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kangro HO, Chong SK, Hardiman A, Heath RB, Walker-Smith JA. A prospective study of viral and mycoplasma infections in chronic inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterology. 1990;98:549–553. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(90)90272-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karmeli F, Cohen P, Rachmilewitz D. Cyclo-oxygenase-2 inhibitors ameliorate the severity of experimental colitis in rats. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2000;12:223–231. doi: 10.1097/00042737-200012020-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kent S, Bluthe RM, Dantzer R, Hardwick AJ, Kelley KW, Rothwell NJ, Vannice JL. Different receptor mechanisms mediate the pyrogenic and behavioral effects of interleukin 1. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1992;89:9117–9120. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.19.9117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kluger MJ, Conn CA, Franklin B, Freter R, Abrams GD. Effect of gastrointestinal flora on body temperature of rats and mice. Am J Physiol. 1990;258:R552–557. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1990.258.2.R552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kluger MJ, Kozak W, Conn CA, Leon LR, Soszynski D. Role of fever in disease. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1998;856:224–233. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1998.tb08329.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kluger MJ, Ringler DH, Anver MR. Fever and survival. Science. 1975;188:166–168. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kojima K, Naruse Y, Iijima N, Wakabayashi N, Mitsufuji S, Ibata Y, Tanaka M. HPA-axis responses during experimental colitis in the rat. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2002;282:R1348–1355. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00260.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kresse AE, Million M, Saperas E, Tache Y. Colitis induces CRF expression in hypothalamic magnocellular neurons and blunts CRF gene response to stress in rats. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2001;281:G1203–1213. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.2001.281.5.G1203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larson SJ, Collins SM, Weingarten HP. Dissociation of temperature changes and anorexia after experimental colitis and LPS administration in rats. Am J Physiol. 1996;271:R967–972. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1996.271.4.R967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Layé S, Bluthé R-M, Kent S, Combe C, Médina C, Parnet P, Kelley K, Dantzer R. Subdiaphragmatic vagotomy blocks induction of IL-1β mRNA in mice brain in response to peripheral LPS. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 1995;268:R1327–1331. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1995.268.5.R1327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lemay LG, Vander AJ, Kluger MJ. Role of interleukin 6 in fever in rats. Am J Physiol. 1990;258:R798–803. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1990.258.3.R798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leon LR, White AA, Kluger MJ. Role of IL-6 and TNF in thermoregulation and survival during sepsis in mice. Am J Physiol. 1998;275:R269–277. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1998.275.1.R269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luheshi G, Rothwell N. Cytokines and fever. Int Arch Allergy Immunol. 1996;109:301–307. doi: 10.1159/000237256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCafferty DM, Wallace JL, Sharkey KA. Effects of chemical sympathectomy and sensory nerve ablation on experimental colitis in the rat. Am J Physiol. 1997;272:G272–280. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1997.272.2.G272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCullough LK, Takahashi Y, Le T, Pittman QJ, Swain MG. Attenuated febrile response to lipopolysaccharide in rats with biliary obstruction. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2000;279:G172–177. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.2000.279.1.G172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacNeil BJ, Jansen AH, Greenberg AH, Nance DM. Activation and selectivity of splenic sympathetic nerve electrical activity response to bacterial endotoxin. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 1996;270:R264–270. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1996.270.1.R264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maier SF, Goehler LE, Fleshner M, Watkins LR. The role of the vagus nerve in cytokine-to-brain communication. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1998;840:289–300. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1998.tb09569.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin SM, Wilson BC, Chen X, Takahashi Y, Poulin P, Pittman QJ. Vagal CCK and 5-HT(3) receptors are unlikely to mediate LPS or IL-1beta-induced fever. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2000;279:R960–965. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.2000.279.3.R960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mekhjian HS, Switz DM, Melnyk CS, Rankin GB, Brooks RK. Clinical features and natural history of Crohn's disease. Gastroenterology. 1979;77:898–906. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mizoguchi E, Mizoguchi A, Takedatsu H, Cario E, de Jong YP, Ooi CJ, Xavier RJ, Terhorst C, Podolsky DK, Bhan AK. Role of tumor necrosis factor receptor 2 (TNFR2) in colonic epithelial hyperplasia and chronic intestinal inflammation in mice. Gastroenterology. 2002;122:134–144. doi: 10.1053/gast.2002.30347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monteleone G, MacDonald TT. Manipulation of cytokines in the management of patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Ann Med. 2000;32:552–560. doi: 10.3109/07853890008998835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monteleone G, MacDonald TT, Wathen NC, Pallone F, Pender SL. Enhancing Lamina propria Th1 cell responses with interleukin 12 produces severe tissue injury. Gastroenterology. 1999;117:1069–1077. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(99)70391-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris GP, Beck PL, Herridge MS, Depew WT, Szewczuk MR, Wallace JL. Hapten-induced model of chronic inflammation and ulceration in the rat colon. Gastroenterology. 1989;96:795–803. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neilly PJ, Gardiner KR, Kirk SJ, Jennings G, Anderson NH, Elia M, Rowlands BJ. Endotoxaemia and cytokine production in experimental colitis. Br J Surg. 1995;82:1479–1482. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800821110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Owens MJ, Nemeroff CB. The role of corticotropin-releasing factor in the pathophysiology of affective and anxiety disorders: laboratory and clinical studies. Ciba Found Symp. 1993;172:296–308. doi: 10.1002/9780470514368.ch15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng ZC, Kristensson K, Bentivoglio M. Dysregulation of photic induction of Fos-related protein in the biological clock during experimental trypanosomiasis. Neurosci Lett. 1994;182:104–106. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(94)90217-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qiu BS, Vallance BA, Blennerhassett PA, Collins SM. The role of CD4+ lymphocytes in the susceptibility of mice to stress-induced reactivation of experimental colitis. Nat Med. 1999;5:1178–1182. doi: 10.1038/13503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rath HC, Schultz M, Freitag R, Dieleman LA, Li F, Linde HJ, Scholmerich J, Sartor RB. Different subsets of enteric bacteria induce and perpetuate experimental colitis in rats and mice. Infect Immun. 2001;69:2277–2285. doi: 10.1128/IAI.69.4.2277-2285.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Refinetti R, Menaker M. The circadian rhythm of body temperature. Physiol Behav. 1992;51:613–637. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(92)90188-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ricote M, Li AC, Willson TM, Kelly CJ, Glass CK. The peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma is a negative regulator of macrophage activation. Nature. 1998;391:79–82. doi: 10.1038/34178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romanovsky AA, Blatteis CM. Biphasic fever: What triggers the second temperature rise. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 1995;269:R280–286. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1995.269.2.R280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romanovsky AA, Kulchitsky VA, Akulich NV, Koulchitsky SV, Simons CT, Sessler DI, Gourine VN. The two phases of biphasic fever-two different strategies for fighting infection? Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1997;813:485–490. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1997.tb51737.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roth J, McClellan JL, Kluger MJ, Zeisberger E. Attenuation of fever and release of cytokines after repeated injections of lipopolysaccharide in guinea-pigs. J Physiol. 1994;477:177–185. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1994.sp020182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruther U, Nunnensiek C, Muller HA, Bader H, May U, Jipp P. Interferon alpha (IFN alpha 2a) therapy for herpes virus-associated inflammatory bowel disease (ulcerative colitis and Crohn's disease) Hepatogastroenterology. 1998;45:691–699. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strijkstra AM, Meerlo P, Beersma DG. Forced desynchrony of circadian rhythms of body temperature and activity in rats. Chronobiol Int. 1999;16:431–440. doi: 10.3109/07420529908998718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szekely M. The vagus nerve in thermoregulation and energy metabolism. Auton Neurosci. 2000;85:26–38. doi: 10.1016/S1566-0702(00)00217-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ten Hove T, Corbaz A, Amitai H, Aloni S, Belzer I, Graber P, Drillenburg P, van Deventer SJ, Chvatchko Y, Te Velde AA. Blockade of endogenous IL-18 ameliorates TNBS-induced colitis by decreasing local TNF-alpha production in mice. Gastroenterology. 2001;121:1372–1379. doi: 10.1053/gast.2001.29579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tollner B, Roth J, Storr B, Martin D, Voigt K, Zeisberger E. The role of tumor necrosis factor (TNF) in the febrile and metabolic responses of rats to intraperitoneal injection of a high dose of lipopolysaccharide. Pflugers Arch. 2000;440:925–932. doi: 10.1007/s004240000386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Dullemen HM, Wolbink GJ, Wever PC, van der Poll T, Hack CE, Tytgat GN, van Deventer SJ. Reduction of circulating secretory phospholipase A2 levels by anti-tumor necrosis factor chimeric monoclonal antibody in patients with severe Crohn's disease. Relation between tumor necrosis factor and secretory phospholipase A2 in healthy humans and in active Crohn's disease. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1998;33:1094–1098. doi: 10.1080/003655298750026813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- West MA, Heagy W. Endotoxin tolerance: a review. Crit Care Med. 2002;30:S64–S73. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto M, Yoshizaki K, Kishimoto T, Ito H. IL-6 is required for the development of Th1 cell-mediated murine colitis. J Immunol. 2000;164:4878–4882. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.164.9.4878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeisberger E, Roth J. Tolerance to pyrogens. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1998;856:116–131. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1998.tb08320.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang G, Ghosh S. Molecular mechanisms of NF-kappaB activation induced by bacterial lipopolysaccharide through Toll-like receptors. J Endotoxin Res. 2000;6:453–457. doi: 10.1179/096805100101532414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]