Abstract

We have established an in vitro model of airway hyperresponsiveness, using a bovine tracheal smooth muscle cell (BTSMC)-embedded collagen gel lattice. When the gel was pretreated with lysophosphatidic acid (LPA), which activates the small G protein RhoA, ATP- and high K+ solution-induced gel contraction was significantly augmented. This was not due to the modulation of Ca2+ mobilizing properties, since ATP- and high K+-induced Ca2+ transients were not significantly different between control and LPA-treated BTSMC. Y-27632, an inhibitor of Rho-kinase, suppressed the LPA-induced augmentation of gel contraction, whereas it did not inhibit the contraction of control gels. Theophylline (> 1 μm) reversed the LPA-induced augmentation of gel contraction, whereas it inhibited control gel contraction only with a very high concentration (100 μm). We confirmed that theophylline increased the intracellular concentration of cAMP ([cAMP]i) in BTSMC. Elevation of [cAMP]i with dibutyryl cAMP or forskolin also reversed the LPA-induced augmentation of gel contraction. Furthermore, theophylline, as well as dibutyryl cAMP and forskolin, suppressed the LPA-induced membrane translocation of RhoA, indicating that they prevented airway hyperresponsiveness by inhibiting RhoA. We conclude from these results that theophylline inhibits LPA-induced, RhoA/Rho-kinase-mediated hyperresponsiveness of tracheal smooth muscle cells due to the accumulation of cAMP.

Various specific and non-specific stimulations induce contraction in asthmatic tracheal muscle much more intensively than in non-asthmatic muscle, thereby leading to a stronger contraction of trachea. Dysfunction of airway smooth muscle cells (Solway & Fredberg, 1997), as well as the impairment of neural or epithelial control of smooth muscle contraction (Ito, 1991; Ten Broeke et al. 2001) and airway wall thickness (Thomson et al., 1996), has been considered to lead to this phenomenon, i.e. airway hyperresponsiveness. Accumulated evidence suggests an important role for RhoA, a small G protein, and its downstream Rho-kinase, in the functional alterations of hyperresponsive tracheal smooth muscle cells. For instance, methacholine- and serotonin-induced increase in murine lung resistance was augmented by ovalbumin sensitization and respiratory syncytial virus infection, and these were inhibited by Y-27632, a Rho-kinase inhibitor (Hashimoto et al. 2002a). Furthermore, leukotriene C4 enhanced the contraction in porcine tracheal smooth muscle by increasing Ca2+ responsiveness through the activation of the RhoA/Rho-kinase pathway (Setoguchi et al. 2001).

Lysophosphatidic acid (LPA) is a bioactive lipid that is generated in body fluid by secretory lysophospholipase D (Tokumura, 2002), and also secreted from platelets (Moolenaar, 1995) and injured epithelium (Shen et al. 1998). Since LPA could contribute to structural remodelling (Cerutis et al. 1997) and acute hyperresponsiveness (Toews et al. 1997; Hashimoto et al. 2001) of tracheal smooth muscles in vitro, potential roles for LPA in the development of respiratory diseases, especially asthma, have been suggested (Toews et al. 2002). LPA binds to its specific G protein-coupled receptors and activates the RhoA/Rho-kinase pathway (Moolenaar, 1995). Therefore, it can be speculated that LPA would induce airway hyperresponsiveness through the activation of the RhoA/Rho-kinase pathway.

Theophylline, a methylxanthine, is one of the commonly used bronchodilators. It induces the relaxation of tracheal smooth muscle due to various but not completely understood mechanisms, including (1) relatively non-selective inhibition of phosphodiesterases, thereby increasing the intracellular cAMP concentration (Beavo & Reifsnyder, 1990), (2) antagonism of adenosine receptors (Fredholm & Persson, 1982), and (3) inhibition of the rise in intracellular Ca2+ concentration ([Ca2+]i) (Ali et al. 1996). It is now believed that theophylline also ameliorates airway hyperresponsiveness (Barnes & Pauwels, 1994). However, possible alterations of the RhoA/Rho-kinase pathway by theophylline have not so far been considered.

Kimura et al. (2002) reported a novel method for investigating contractile properties of cultured aortic smooth muscle cells by using cell-embedded collagen gel. Since collagen gel lattice is highly porous, and therefore drugs can easily gain access to the embedded cells, we supposed that this method could be applied to examine whether LPA induces hyperresponsiveness in tracheal smooth muscle cells. The present study aims firstly to establish an in vitro model of hyperresponsive trachea using LPA and tracheal smooth muscle-embedded collagen gel lattice, and secondly, to examine the effects of theophylline on airway hyperresponsiveness. The results obtained suggest that LPA induces RhoA/Rho-kinase-mediated hyperresponsiveness in bovine tracheal smooth muscle cells (BTSMC), and theophylline inhibits airway hyperresponsiveness due to the accumulated cAMP-induced inhibition of the translocation of RhoA.

Methods

Cell culture

Tracheas of 1-year-old calves were obtained from a local slaughterhouse. Smooth muscle cells were then cultured in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10 % fetal bovine serum (FBS) by the explant method (Chamley et al. 1977). Confluent cells were harvested by trypsin digestion and stored at −80 °C after one step subculture. The present study was performed using BTSMC obtained from five tracheas.

Gel contraction assay

A gel contraction assay (Kimura et al. 2002) was used to examine the contractility of cultured BTSMC. Stored BTSMC were re-suspended in collagen solution containing 0.2 % type IA collagen (Nitta Gelatin Inc., Osaka, Japan) in DMEM at a density of 4 × 105 cells ml−1 at 4 °C. The BTSMC-containing collagen solution (0.5 ml) was poured into a 24-well culture plate and allowed to form a gel for 10 min at 37 °C, and then 1 ml of DMEM with 10 % FBS was poured onto the gel. After culturing for 3 days at 37 °C, the gel was used for the contraction assay. Embedded BTSMC were randomly oriented, and showed a spindle-like shape as shown in Fig. 1A (upper panel), and the number of the embedded cells did not increase significantly in 3 days (not shown).

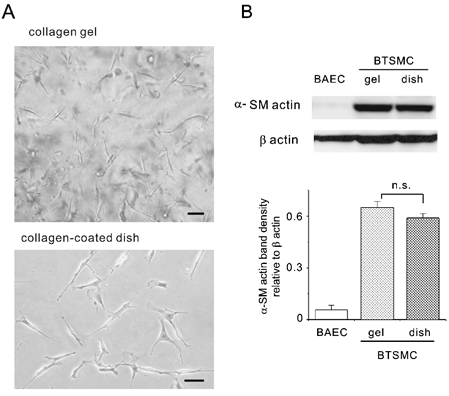

Figure 1. Bovine tracheal smooth muscle cells (BTSMC) used in the present study.

A, the microscope view of BTSMC embedded in three-dimensional collagen gel lattice shows that they were spindle-shaped and randomly oriented (upper panel). Cells grown on collagen-coated coverslips also showed the spindle shape (lower panel). Bars indicate 50 μm for both panels. B, Western blotting analysis of cell extracts. BTSMC showed similar levels of αSMA expression both in collage gels and on collagen-coated dishes. Trace expression of αSMA in endothelial cells from bovine aorta (BAEC) is shown as a negative control. The histogram shows the densitometric analysis of the αSMA band, which is expressed relative to the band density of β-actin, an internal control. Each bar shows the mean and s.e.m. value (n = 3); n.s., P > 0.05.

After each pretreatment of the gel, its lateral surface was carefully detached from the culture well with a fine needle. The culture plate was then placed on a hotplate (MP-10DM; Kitazato Supply, Shizuoka, Japan) and kept at 37 °C. The gel images were captured with a digital camera (QV-800SX, Casio, Tokyo, Japan) every 1 min throughout the experiment. The area of the gel was then evaluated by measuring the pixel numbers of the gel surface with an image analysis software (Adobe Photoshop, Adobe Systems, Inc., USA).

Measurement of intracellular Ca2+concentration

[Ca2+]i was measured at room temperature (20–25 °C) by using an Attofluor digital fluorescence microscopy system (Atto Instruments, Rockville, MD, USA). Cells were seeded on a collagen-coated coverslip and cultured for 3–5 days (Fig. 1A, lower panel). Cells were then loaded with fura-2/AM (Dojindo, Kumamoto, Japan) as previously described (Oike et al., 2000). Fura-2 was excited at two alternative wavelengths (340 and 380 nm) and the fura-2 fluorescence images emitted at 510 nm wavelength were recorded onto a rewritable optical disc recorder (LQ-4100A, Panasonic, Osaka, Japan) at a rate of approximately 1 Hz. Fluorescent intensities at two wavelengths (F340 and F380) were obtained from the recorded images to calculate the fluorescent ratio (R), F340/F380. R was then converted into the apparent [Ca2+]i using in vitro calibration as described previously (Oike et al. 2000). [Ca2+]i values from 20–25 cells in a measurement were averaged and regarded as one result.

Measurement of intracellular cAMP concentration

[cAMP]i was measured with enzyme immunoassay (EIA) using a commercial kit (Biotrak cAMP EIA system, Amersham Pharmacia Biotech, Buckinghamshire, UK). In brief, BTSMC were cultured overnight at a density of 5000 cells well−1 in 96-well culture plates. Cells were lysed with 2.5 % dodecyltrimethylammonium bromide solution after each pretreatment. The lysate was then transferred to a 96-well titre plate coated with anti-rabbit IgG, and binding to anti-cAMP antibody was determined by measuring the optical density at 450 nm. The optical density obtained was converted into [cAMP]i using a standard curve that was obtained at the same measurement.

Western blot analysis of α smooth muscle actin and RhoA activation

The nature of the smooth muscle of the BTSMC used in the present study was examined by Western blot analysis of α smooth muscle actin (αSMA) expression. BTSMC embedded in collagen gel for 3 days were harvested by digesting collagen with collagenase (Sigma, St Louis, MO, USA) for 30 min at 37 °C, and then lysing with 1 % Triton X-100. BTSMC grown on 60 mm collagen-coated dishes were also lysed with Triton X-100. Enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL) Western blotting was then performed with these cell lysates, using anti-αSMA antibody (Daco, Glostrup, Denmark). Expression of β-actin was examined simultaneously as an internal control, using monoclonal anti-β-actin antibody (Sigma).

Activation of RhoA was also assessed using enhanced ECL Western blotting. BTSMC grown on collagen-coated culture dishes were pretreated with theophylline, dibutyryl cAMP, forskolin or vehicle for 1 h. Cells were then lysed immediately or after applying 1 μm LPA for 5 min. The cell lysate was centrifuged for 1 h at 100 000 g and the pellet was harvested as a membrane fraction. A constant amount of membrane fraction (50 μg protein lane−1) was separated with SDS-PAGE, and Western blotting was performed by using anti-RhoA antibody (Cytoskeleton, Inc., Denver, CO, USA).

For both assays, emitted chemiluminescence was detected and analysed with a lumino image analyzer (FAS-1000, Toyobo, Osaka, Japan).

Drugs and solution

The modified Krebs solution used in the present experiment was (mm): NaCl 132.4, KCl 5.9, CaCl2 1.5, MgCl2 1.2, glucose 11.5, Hepes 11.5, and pH was adjusted to 7.4 with NaOH. High K+ solution was made by changing the NaCl and KCl concentrations in Krebs solution to 79.3 and 59 mm, respectively. LPA (Sigma) was dissolved at 3 mm in chloroform-methanol (1: 1 mixture). The solvent was evaporated by puffing nitrogen gas, Krebs solution was added to make 20 μm LPA solution and this was then sonicated. The solution was further diluted to 1 μm shortly before use. ATP, theophylline, forskolin, dibutyryl cAMP, and protein kinase inhibitor were purchased from Sigma. Y-27632 was kindly provided by Mitsubishi Pharma Co. (Osaka, Japan).

Statistics

Pooled data were expressed as means ± s.e.m. The statistical significance in the gel contraction assay was assessed with a repeated measures ANOVA with the Bonferroni post hoc test using data points from 10 to 70 min. The statistical significance in the [Ca2+]i assay was assessed with Student's unpaired t test. StatView (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA) was used for both analyses. Probability below 0.05 (P < 0.05) was considered to be a significant difference.

Results

Expression of α smooth muscle actin in cultured BTSMC

We confirmed with Western blotting that cultured BTSMC used in the present study retained their smooth muscle nature. As shown in Fig. 1B, BTSMC expressed αSMA to the same extent both in collagen gel and on collagen-coated plates.

Effects of LPA on muscle contractility

Firstly we examined the effects of various chemical mediators such as acetylcholine, histamine, 5-HT and ATP on the contractility of the BTSMC-embedded collagen gel. Among these agonists, ATP reduced the gel surface area consistently as reported in aortic smooth muscle-embedded collagen gel (Kimura et al. 2002). ATP (1 μm) reduced the gel surface area by 4.5 ± 0.3 % (n = 65) at 60 min after ATP application (hereafter referred to as gel contraction), which developed gradually and was reversible (Fig. 2A). ATP-induced gel contraction was concentration dependent with a threshold of 0.01 μm (not shown), and it was not observed in the absence of ATP or without embedded BTSMC (Fig. 2A), thereby indicating that gel contraction was due to the contraction of BTSMC. Gel contraction was also observed in response to membrane depolarization induced by 59 mm K+ solution (Fig. 2B, 3.0 ± 0.2 % reduction of gel surface at 60 min, n = 10).

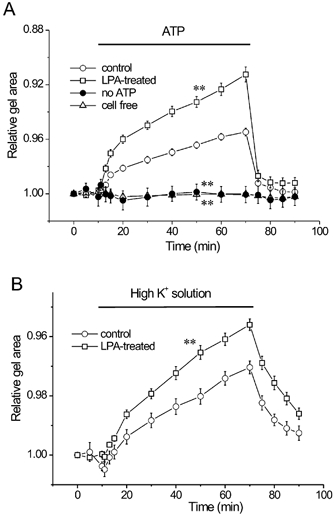

Figure 2. Augmentation of gel contraction by lysophosphatidic acid (LPA).

BTSMC-embedded collagen gel was pretreated with either vehicle or 1 μmLPA for 1 h at 37 °C. A, ATP (1 μm) induced gel contraction in control gels (○, n = 66). LPA augmented ATP-induced contraction significantly (□, n = 53). Contraction was not evoked by solution exchange alone without ATP application (•, n = 6), and gels without embedded BTSMC did not show contraction in response to ATP (▵, n = 6). B, high K+ concentration solution (59 mm) showed contraction (○, n = 10), which was also augmented in LPA-treated gels (□, n = 10). Gel surface area was measured and expressed relative to the initial gel area. **P < 0.01vs. control.

Next we examined the effects of LPA on gel contractility. When the gel was pretreated with 1 μm LPA for 1 h, ATP-induced gel contraction was augmented (Fig. 2A, 8.8 ± 0.5 % reduction of gel surface area at 60 min, n = 53). During the application of ATP, gel area was significantly smaller than in the untreated control (P < 0.01vs. control). LPA also significantly augmented the high K+-induced gel contraction (Fig. 2B, n = 10, P < 0.05vs. control). Pretreatment with 10 μm Y-27632, an inhibitor of Rho-kinase, did not affect the ATP-induced contraction of control gels (Fig. 3A, n = 9, P > 0.05vs. control). In contrast, it significantly inhibited the LPA-induced augmentation of gel contraction (Fig. 3B, n = 17, P < 0.01vs. LPA alone). Similar results were also observed in high K+-induced gel contraction (not shown). These indicate that Rho-kinase is involved in the LPA-induced augmentation of gel contraction.

Figure 3. Effects of Y-27632 on gel contraction.

BTSMC-embedded gels were pretreated for 1 h with 10 μm Y-27632 with or without 1 μm LPA. A, contraction of control gels was not affected by Y-27632 (•, n = 9). Superimposed control data are the same as those shown in Fig. 2A (○, n = 66). B, Y-27632 inhibited LPA-induced hyperresponsiveness (▪, n = 17). Values of LPA alone are same as in Fig. 2A (□, n = 53) **P < 0.01vs. LPA alone.

Inhibitory actions of theophylline on LPA-induced increase in muscle contractility

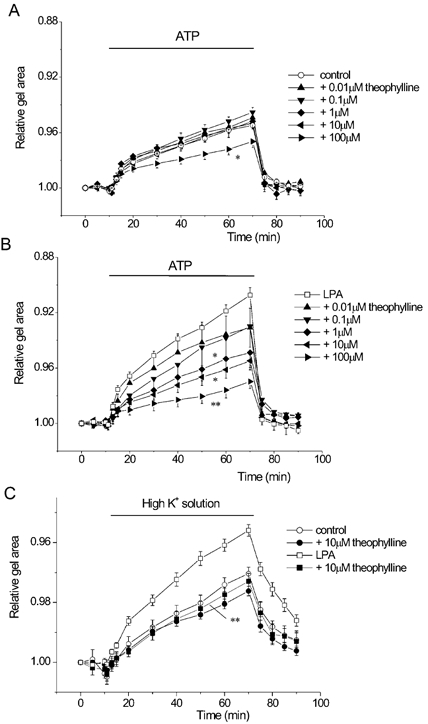

We then examined the effects of theophylline on the contractility of BTSMC-embedded collagen gel. Gels were pretreated with theophylline with or without LPA for 1 h. Pretreatment with theophylline alone inhibited the ATP-induced contraction of control gels, but this was obtained with a very high concentration (100 μm, Fig. 4A). In contrast, theophylline suppressed the LPA-induced augmentation of gel contraction in a concentration-dependent manner (Fig. 4B), and significant inhibition was observed at concentrations above 1 μm. Thus it seems that theophylline inhibits the contraction of LPA-treated gels more efficiently than control gel contraction in BTSMC.

Figure 4. Effects of theophylline on gel contraction.

BTSMC-embedded collagen gels were pretreated for 1 h with each concentration of theophylline with or without 1 μm LPA. A, effects of theophylline on control gel contraction (n = 6–8). Significant inhibition was obtained only with 100 μm theophylline (▸, P < 0.05 vs. control). B, theophylline inhibited LPA-induced augmentation of gel contraction in a concentration-dependent manner (n = 7–9). Significant inhibition was obtained with theophylline higher than 1 μm. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01vs. LPA alone (□, n = 53). C, theophylline (10 mm) reversed the effects of LPA on gel contraction but not control gel contraction induced by 59 mmK+ solution. Data are obtained from 10 experiments for each symbol. **P < 0.01vs. LPA alone.

Similar results were also obtained with high K+ contraction, i.e. LPA-induced augmentation of gel contraction was inhibited, whereas control gel contraction was not affected by 10 μm theophylline (Fig. 4C).

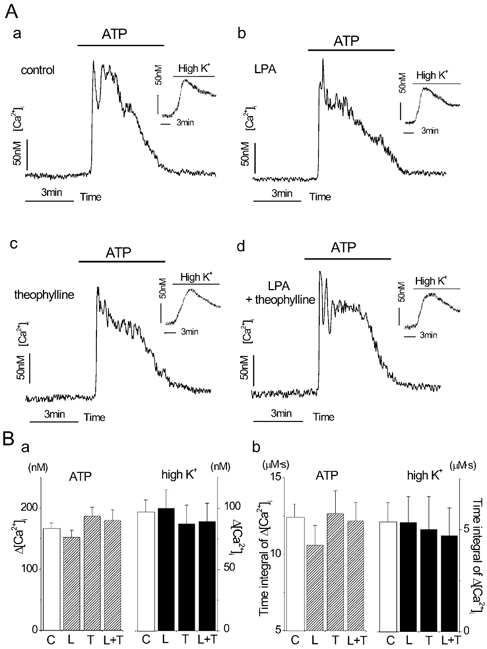

Theophylline does not affect the Ca2+ mobilization in BTSMC

Since Ca2+ mobilizing properties play an essential role in muscle contraction, we examined the effects of LPA and theophylline on ATP- and high K+-induced Ca2+ transients in BTSMC. [Ca2+]i was measured from cells seeded on collagen-coated coverslips so that cells were surrounded by collagen as in the gel contraction assay. Cells were pretreated with either vehicle or 1 μm LPA in the absence or presence of 10 μm theophylline for 1 h at 37 °C.

ATP (1 μm) evoked Ca2+ transients both in control (Fig. 5Aa) and in LPA-treated (Fig. 5Ab) BTSMC. ATP-induced Ca2+ transients were also observed in Ca2+-free solution, and were inhibited by U73122 and neomycin, which are phospholipase C inhibitors (not shown), thereby indicating that these were mediated by P2Y receptor(s) in BTSMC. The peak increment and time integral for 5 min of the ATP-induced Ca2+ transient were not significantly different between control and LPA-treated cells (Fig. 5B). Furthermore, theophylline did not affect the Ca2+ transient in either control (Fig. 5Ac and B) or LPA-treated cells (Fig. 5Ad and B). High K+ solution induced a gradual increase in [Ca2+]i, which was also not affected by LPA or theophylline (Fig. 5A and B). Therefore, it is obvious that the LPA-induced augmentation of gel contraction and the actions of theophylline were not due to the modulation of Ca2+ mobilizing properties in BTSMC.

Figure 5. Ca2+ mobilizing properties were not affected by LPA and theophylline in BTSMC.

A, representative traces of ATP (1 μm)-induced Ca2+ transient in control untreated cells (a) and cells treated with 1 μm LPA alone (b), 10 μm theophylline alone (c) or 1 μmLPA with 10 μm theophylline (d). High K+-induced increase in [Ca2+]i is also shown in the inset for each condition. Vertical and horizontal bars in each panel indicate calibration values of 50 nm and 3 min, respectively. B, statistical analysis of ATP- and high K+-induced Ca2+ transients. [Ca2+]i was evaluated with either net maximal increase in [Ca2+]i (a) or time integral of net [Ca2+]i increment for 5 min (b). Each value was obtained from 5 measurements with 20–35 cells for each measurement. C, control; L, pretreatment with 1 μm LPA alone; T, pretreatment with 10 μm theophylline alone; L + T, pretreatment with 1 μm LPA and 10 μm theophylline. No significant difference was observed between C and any other condition (P > 0.05).

Effects of LPA and theophylline on [cAMP]i

It is well documented that theophylline inhibits phosphodiesterase and leads to accumulation of cAMP. We then examined the effects of theophylline on the intracellular cAMP concentration ([cAMP]i) in control and LPA-treated BTSMC. [cAMP]i was increased from 86 ± 11 fmol well−1 to 124 ± 13, 440 ± 65 and 561 ± 76 fmol well−1 by 1, 10 and 100 μm theophylline, respectively, in untreated control cells (n = 6 for each condition). Furthermore, LPA did not affect [cAMP]i either in the presence or in the absence of theophylline (LPA alone, 94 ± 10 fmol well−1; 10 μm theophylline, 383 ± 26 fmol well−1; 100 μm theophylline, 527 ± 65 fmol well−1; n = 6 for each condition).

Inhibition of LPA-induced hyperresponsiveness of BTSMC by cAMP

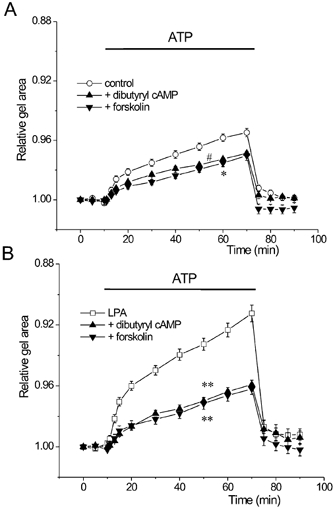

The results described above suggest the possibility that the accumulation of cAMP may be responsible for the inhibition of airway hyperresponsiveness by theophylline. To address this hypothesis, we then examined whether the elevation of [cAMP]i obtained by substances other than theophylline inhibited the LPA-induced augmentation of gel contraction. For this purpose, we treated the gels with forskolin, an activator of adenylate cyclase, or dibutyryl cAMP, a membrane-permeant cAMP.

As shown in Fig. 6A, both forskolin (30 μm) and dibutyryl cAMP (300 μm) slightly suppressed the contraction of control gels (P < 0.05, vs. control). The inhibitions of gel contraction by these agents were, however, much more prominent in LPA-treated gels (Fig. 6B, P < 0.01vs. LPA alone). Similar results were also obtained in high K+-induced gel contraction (not shown), thereby indicating that cAMP inhibits LPA-induced hyperresponsiveness in BTSMC.

Figure 6. Effects of cAMP on gel contraction.

Gels were pretreated either with 300 μm dibutyryl cAMP or 30 μm forskolin in the absence or presence of 1 μm LPA. A, control BTSMC-embedded gel contraction was slightly inhibited by dibutyryl cAMP (▴, n = 10) and forskolin (▾, n = 10). Significant inhibition of contraction (P < 0.05) was observed throughout the ATP application period for forskolin (*) and during the 50 to 70 min data points for dibutyryl cAMP (#). B, contraction of the gels pretreated with LPA was significantly inhibited by dibutyryl cAMP (▴, n = 8) and forskolin (▾, n = 8). **P < 0.01vs. LPA alone (□, n = 53).

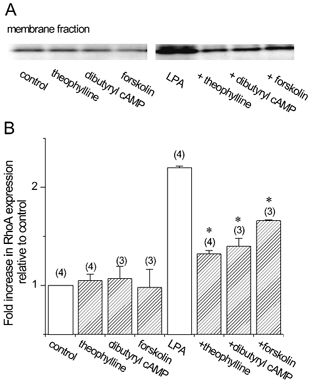

cAMP inhibits LPA-induced RhoA activation

To clarify the point of action of cAMP, we finally examined the effects of theophylline, forskolin and dibutyryl cAMP on the membrane translocation of RhoA. LPA increased the amount of RhoA in the membrane fraction, a hallmark of the activation of RhoA (Kranenburg et al. 1997) in BTSMC (Fig. 7). When the cells were pretreated with theophylline (10 μm), forskolin (30 μm) or dibutyryl cAMP (300 μm), LPA-induced membrane translocation of RhoA was markedly inhibited, whereas these agents did not affect the amount of RhoA in the membrane fraction of control cells (Fig. 7).

Figure 7. Effects of theophylline and cAMP on membrane translocation of RhoA in BTSMC.

Cells were pretreated with vehicle, 10 μm theophylline, 300 μm dibutyryl cAMP or 30 μm forskolin for 1 h, and lysed immediately (control) or after applying 1 μm LPA for 5 min. Representative data are shown in A. Note that LPA induced marked increase in the RhoA band in the membrane fraction, which was suppressed by theophylline, dibutyryl cAMP and forskolin. Densitometric analysis of the bands is shown in B. Values are means and s.e.m. from n measurements where n values are given in parentheses. *P < 0.05vs. LPA alone.

Discussion

ATP and high K+ depolarization induced reversible contraction of BTSMC-embedded collagen gel (Fig. 2). Since gel contraction was not observed without BTSMC or ATP application, changes in gel surface area properly corresponded to the contraction and relaxation of embedded BTSMC. Similar contractile response has been reported in aortic smooth muscle cells-embedded collagen gel (Kimura et al. 2002). The major advantage of these collagen gel systems is that they enable the analysis of cultured smooth muscle contraction after any pretreatments without interference from tissue enzymes and/or tight connective tissues.

We have shown in this study that LPA augments both ATP- and high K+-induced gel contractions (Fig. 2). LPA treatment itself did not induce spontaneous gel contraction for at least up to 90 min both in BTSMC-embedded and cell-free gels (not shown). Furthermore, though some groups using vascular smooth muscle cells reported that the bath application of LPA acutely induced Ca2+ transients (Seewald et al. 1997; Gennero et al. 1999), pretreatment with LPA for 1 h did not affect the Ca2+ mobilizing properties induced by ATP and high K+ in BTSMC (Fig. 5). Therefore, LPA-induced augmentation of gel contraction was not due to the direct contraction of collagen and/or BTSMC nor was it due to the alteration of Ca2+ mobilizing properties; it was due to the hyperresponsiveness of BTSMC. Inhaled LPA-induced airway hyperresponsiveness was previously reported in vivo in guinea-pig, but the authors failed to observe the augmentative actions of LPA on acetylcholine-induced contraction in excised tracheal tissues (Hashimoto et al. 2002b). Another group, using rabbit tracheal rings, reported that contractions induced by agonists (methacholine, serotonin and substance P) were augmented whereas high K+ depolarization-induced contraction was not affected by LPA (Toews et al. 1997). These authors speculated that the effects of LPA were not due to the induction of hypersensitivity to Ca2+ but to the release of histamine from lung tissues (Hashimoto et al. 2002b) or the modulation of receptor-mediated Ca2+ mobilization (Toews et al. 1997). However, the present study clearly excludes these possibilities in BTSMC, because (1) LPA induced hyperresponsiveness in the gel contraction system without surrounding lung tissues that could induce the release of neurotransmitters (Fig. 2), and (2) ATP- or high K+-induced Ca2+ mobilization was not affected by LPA (Fig. 5). We suppose that the discrepancy between these reports and the present study, besides the species-to-species variance, is because we used the gel contraction assay that allows efficient access of LPA to smooth muscle cells.

LPA binds to its specific receptor(s) and activates RhoA (Moolenaar, 1995), and we actually observed the membrane translocation of RhoA by LPA in BTSMC (Fig. 7). Of three known LPA receptor subtypes, LPA1 and LPA2 receptors are reported to be involved in the activation of RhoA (Ishii et al. 2000). So we suppose that one or both of these LPA receptor subtypes is (are) involved in the LPA-induced hyperresponsiveness in BTSMC. We also observed that Y-27632 reversed the LPA-induced tracheal hyperresponsiveness (Fig. 3B), without affecting the control gel contraction (Fig. 3A). Thus we have concluded that LPA-induced augmentation of gel contraction was due to the activation of the RhoA/Rho-kinase pathway in BTSMC. Involvement of RhoA/Rho-kinase in the pathogenesis of airway hyperresponsiveness has also been suggested in previous reports (Yoshii et al. 1999; Setoguchi et al. 2001; Hashimoto et al. 2002a). It is generally considered that smooth muscle tone is regulated by phosphorylation and dephosphorylation of myosin light chain, through the activation of Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent myosin light chain kinase and type 1 myosin phosphatase, respectively (Pfitzer, 2001). Since Rho-kinase phosphorylates and inactivates myosin phosphatase (Kimura et al. 1996), this property may be involved in the development of RhoA/Rho-kinase-mediated airway hyperresponsiveness.

We observed a significant inhibition of control gel contraction with a high concentration of theophylline (100 μm, Fig. 4A). This result agrees with previous reports showing that theophylline inhibits untreated trachea due to various mechanisms (Fredholm & Persson, 1982; Beavo & Reifsnyder, 1990; Ali et al. 1996) with relatively high IC50 values: e.g. 28 μm (Ogawa et al. 1989) or 84 μm (Iizuka et al. 2000) in guinea-pig trachea. Furthermore, we have clarified that theophylline reverses LPA-induced hyperresponsiveness of BTSMC in a concentration-dependent manner from as low as 1 μm (Fig. 4B), without affecting Ca2+ mobilizing properties (Fig. 5). We have also shown that theophylline inhibited the LPA-induced membrane translocation of RhoA (Fig. 7). Thus we propose a novel mechanism that theophylline inhibits the LPA-induced airway hyperresponsiveness by suppressing the activation of RhoA. It should be noted, however, that these results do not exclude the possibility that theophylline also inhibits Rho-kinase directly.

In this study we confirmed that theophylline increased [cAMP]i and this was not affected by LPA in BTSMC. It has been reported that cAMP inhibits the activation of RhoA in the B16 melanoma tumour cell line (Busca et al. 1998) and Swiss 3T3 cells (Faucheux & Nagel, 2002). We have also shown in BTSMC that dibutyryl cAMP and forskolin inhibit the LPA-induced membrane translocation of RhoA (Fig. 7). Therefore it is very likely that theophylline inhibited LPA-induced airway hyperresponsiveness by the accumulation of cAMP. This notion is supported by the observation that dibutyryl cAMP and forskolin inhibited the LPA-induced augmentation of gel contraction (Fig. 6). Although these agents did inhibit the control gel contraction (Fig. 6A), they showed more prominent inhibition of the LPA-induced augmentation of gel contraction (Fig. 6B). Therefore we suppose that the inhibition of RhoA with accumulated cAMP is one of the central mechanisms of theophylline-induced inhibition of airway hyperresponsiveness.

Amelioration of airway hyperresponsiveness is useful for the treatment of asthma. The present results suggest that the inhibition of RhoA with cAMP-elevating agents would be highly beneficial for this purpose, instead of altering Ca2+, which is often believed to be useful. The next objective will be to determine whether or not airway hyperresponsiveness induced by stimuli other than LPA is also controllable with the elevation of [cAMP]i. In conclusion, firstly, we have introduced an in vitro model of hyperresponsive tracheal smooth muscle by using LPA and, secondly, we have shown that the elevation of [cAMP]i reverses airway hyperresponsiveness due to the inhibition of RhoA.

References

- Ali S, Metzger WJ, Mustafa SJ. Simultaneous measurement of cyclopentyladenosine-induced contraction and intracellular calcium in bronchial rings from allergic rabbits and it's antagonism. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1996;278:639–644. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnes PJ, Pauwels RA. Theophylline in the management of asthma: time for reappraisal? Eur Respir J. 1994;7:579–591. doi: 10.1183/09031936.94.07030579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Busca R, Bertolotto C, Abbe P, Englaro W, Ishizaki T, Narumiya S, Boquet P, Ortonne JP, Ballotti R. Inhibition of Rho is required for cAMP-induced melanoma cell differentiation. Mol Biol Cell. 1998;9:1367–1378. doi: 10.1091/mbc.9.6.1367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cerutis DR, Nogami M, Anderson JL, Churchill JD, Romberger DJ, Rennard SI, Toews ML. Lysophosphatidic acid and EGF stimulate mitogenesis in human airway smooth muscle cells. Am J Physiol. 1997;273:L10–15. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.1997.273.1.L10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chamley JH, Campbell GR, McConnell JD, Groschel-Stewart U. Comparison of vascular smooth muscle cells from adult human, monkey and rabbit in primary culture and in subculture. Cell Tissue Res. 1977;177:503–522. doi: 10.1007/BF00220611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faucheux N, Nagel MD. Cyclic AMP-dependent aggregation of Swiss 3T3 cells on a cellulose substratum (Cuprophan) and decreased cell membrane Rho A. Biomaterials. 2002;23:2295–2301. doi: 10.1016/s0142-9612(01)00363-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fredholm BB, Persson CG. Xanthine derivatives as adenosine receptor antagonists. Eur J Pharmacol. 1982;81:673–676. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(82)90359-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gennero I, Xuereb JM, Simon MF, Girolami JP, Bascands JL, Chap H, Boneu B, Sie P. Effects of lysophosphatidic acid on proliferation and cytosolic Ca++ of human adult vascular smooth muscle cells in culture. Thromb Res. 1999;94:317–326. doi: 10.1016/s0049-3848(99)00004-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hashimoto K, Peebles RS, Jr, Sheller JR, Jarzecka K, Furlong J, Mitchell DB, Hartert TV, Graham BS. Suppression of airway hyperresponsiveness induced by ovalbumin sensitisation and RSV infection with Y-27632, a Rho kinase inhibitor. Thorax. 2002a;57:524–527. doi: 10.1136/thorax.57.6.524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hashimoto T, Nakano Y, Ohata H, Momose K. Lysophosphatidic acid enhances airway response to acetylcholine in guinea pigs. Life Sci. 2001;70:199–205. doi: 10.1016/s0024-3205(01)01382-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hashimoto T, Nakano Y, Yamashita M, Fang YI, Ohata H, Momose K. Role of Rho-associated protein kinase and histamine in lysophosphatidic acid-induced airway hyperresponsiveness in guinea pigs. Jpn J Pharmacol. 2002b;88:256–261. doi: 10.1254/jjp.88.256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iizuka K, Shimizu Y, Tsukagoshi H, Yoshii A, Harada T, Dobashi K, Murozono T, Nakazawa T, Mori M. Evaluation of Y-27632, a rho-kinase inhibitor, as a bronchodilator in guinea pigs. Eur J Pharmacol. 2000;406:273–279. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(00)00504-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishii I, Contos JJ, Fukushima N, Chun J. Functional comparisons of the lysophosphatidic acid receptors LPA1/VZG-1/ EDG-2, LPA2/EDG-4, and LPA3/EDG-7 in neuronal cell lines using a retrovirus expression system. Mol Pharmacol. 2000;58:895–902. doi: 10.1124/mol.58.5.895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ito Y. Prejunctional control of excitatory neuroeffector transmission by prostaglandins in the airway smooth muscle tissue. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1991;143:S6–10. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/143.3_Pt_2.S6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimura C, Cheng W, Hisadome K, Wang YP, Koyama T, Karashima Y, Oike M, Ito Y. Superoxide anion impairs contractility in cultured aortic smooth muscle cells. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2002;283:H382–390. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00574.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimura K, Ito M, Amano M, Chihara K, Fukata Y, Nakafuku M, Yamamori B, Feng J, Nakano T, Okawa K, Iwamatsu A, Kaibuchi K. Regulation of myosin phosphatase by Rho and Rho-associated kinase (Rho-kinase) Science. 1996;273:245–248. doi: 10.1126/science.273.5272.245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kranenburg O, Poland M, Gebbink M, Oomen L, Moolenaar WH. Dissociation of LPA-induced cytoskeletal contraction from stress fiber formation by differential localization of RhoA. J Cell Sci. 1997;110:2417–2427. doi: 10.1242/jcs.110.19.2417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moolenaar WH. Lysophosphatidic acid signalling. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 1995;7:203–210. doi: 10.1016/0955-0674(95)80029-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogawa K, Takagi K, Satake T. Mechanism of xanthine-induced relaxation of guinea-pig isolated trachealis muscle. Br J Pharmacol. 1989;97:542–546. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1989.tb11983.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oike M, Kimura C, Koyama T, Yoshikawa M, Ito Y. Hypotonic stress-induced dual Ca2+ responses in bovine aortic endothelial cells. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2000;279:H630–638. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.2000.279.2.H630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfitzer G. Invited review: regulation of myosin phosphorylation in smooth muscle. J Appl Physiol. 2001;91:497–503. doi: 10.1152/jappl.2001.91.1.497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seewald S, Sachinidis A, Dusing R, Ko Y, Seul C, Epping P, Vetter H. Lysophosphatidic acid and intracellular signalling in vascular smooth muscle cells. Atherosclerosis. 1997;130:121–131. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9150(96)06055-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Setoguchi H, Nishimura J, Hirano K, Takahashi S, Kanaide H. Leukotriene C4 enhances the contraction of porcine tracheal smooth muscle through the activation of Y-27632, a rho kinase inhibitor, sensitive pathway. Br J Pharmacol. 2001;132:111–118. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0703780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen Z, Belinson J, Morton RE, Xu Y. Phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate stimulates lysophosphatidic acid secretion from ovarian and cervical cancer cells but not from breast or leukemia cells. Gynecol Oncol. 1998;71:364–368. doi: 10.1006/gyno.1998.5193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solway J, Fredberg JJ. Perhaps airway smooth muscle dysfunction contributes to asthmatic bronchial hyperresponsiveness after all. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 1997;17:144–146. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb.17.2.f137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ten Broeke R, Folkerts G, Leusink-Muis T, Van der Linde HJ, Villain M, Manion MK, De Clerck F, Blalock JE, Nijkamp FP. Calcium sensors as new therapeutic targets for airway hyperresponsiveness and asthma. FASEB J. 2001;15:1831–1833. doi: 10.1096/fj.01-0018fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomson RJ, Bramley AM, Schellenberg RR. Airway muscle stereology: implications for increased shortening in asthma. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1996;154:749–757. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.154.3.8810615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toews ML, Ediger TL, Romberger DJ, Rennard SI. Lysophosphatidic acid in airway function and disease. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2002;1582:240–250. doi: 10.1016/s1388-1981(02)00177-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toews ML, Ustinova EE, Schultz HD. Lysophosphatidic acid enhances contractility of isolated airway smooth muscle. J Appl Physiol. 1997;83:1216–1222. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1997.83.4.1216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tokumura A. Physiological and pathophysiological roles of lysophosphatidic acids produced by secretory lysophospholipase D in body fluids. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2002;1582:18–25. doi: 10.1016/s1388-1981(02)00133-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshii A, Iizuka K, Dobashi K, Horie T, Harada T, Nakazawa T, Mori M. Relaxation of contracted rabbit tracheal and human bronchial smooth muscle by Y-27632 through inhibition of Ca2+ sensitization. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 1999;20:1190–1200. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb.20.6.3441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]