Abstract

Previous studies have shown that systemic hypoxia evokes vasodilatation in skeletal muscle that is mediated mainly by adenosine acting on A1 receptors, and that the vasoconstrictor effects of sympathetic nerve activity are depressed during hypoxia. The aim of the present study was to investigate the role of adenosine in this depression. In anaesthetised rats, increases in femoral vascular resistance (FVR) evoked by stimulation of the lumbar sympathetic chain with bursts of impulses at 40 or 20 Hz were greater than those evoked by continuous stimulation at 2 Hz with the same number of impulses (120) over 1 min. All of these responses were substantially reduced by infusion of adenosine or by graded systemic hypoxia (breathing 12, 10 or 8 % O2), increases in FVR evoked by continuous stimulation at 2 Hz being most vulnerable. Blockade of A1 receptors ameliorated the depression caused by adenosine infusion of the increase in FVR evoked by 2 Hz only and did not ameliorate the depression caused by 8 % O2 of increases in FVR evoked by any pattern of sympathetic stimulation. A2A receptor blockade accentuated hypoxia-induced depression of the increase in FVR evoked by burst stimulation at 40 Hz, but had no other effect. Neither A1 nor A2A receptor blockade affected the depression caused by hypoxia (8 % O2) of the FVR increase evoked by noradrenaline infusion. These results indicate that endogenously released adenosine is not responsible for the depression of sympathetically evoked muscle vasoconstriction caused by systemic hypoxia; adenosine may exert a presynaptic facilitatory influence on the vasoconstrictor responses evoked by bursts at high frequency.

Systemic hypoxia induces vasodilatation in skeletal muscle that is attributable to the action of locally released vasodilator factors, the vasodilatation being more pronounced the more severe the hypoxia (Marshall, 2000). However, there is evidence that systemic hypoxia increases muscle sympathetic nerve activity (MSNA; Saito et al. 1988; Rowell et al. 1989; Sun & Reis, 1995), as can be explained by peripheral chemoreceptor stimulation, the central neural effects of hypoxia and by baroreceptor unloading, when the peripheral vasodilatation and myocardial depression of hypoxia reduce systemic arterial pressure (Marshall, 1994,1999). Considered together, these findings suggest the local dilator effects of systemic hypoxia can overcome the normal vasoconstrictor influence of MSNA. An apparently similar phenomenon occurs in skeletal muscle during exercise, when functional hyperaemia occurs despite an increase in MSNA (Hansen et al. 2000). In this condition, activation of ATP-sensitive K+ (KATP) channels and nitric oxide (NO) generated by neuronal NO synthase (nNOS), rather than endothelial NO synthase (eNOS), have been implicated: the actions of locally generated cyclo-oxygenase products and adenosine have been discounted (Sander et al. 2000; Thomas et al. 1997; Thomas & Victor, 1998).

The muscle vasodilatation of systemic hypoxia is mediated largely by adenosine (Skinner & Marshall, 1996; Leuenberger et al. 1999; Marshall, 2000), and in the rat at least, it is attributable to adenosine A1 receptor stimulation (Bryan & Marshall, 1999). The available evidence suggests that the adenosine that contributes to the vasodilatation is largely released from the endothelium, rather than from the skeletal muscle fibres (Mian & Marshall, 1991; Bryan & Marshall, 1999; Marshall, 2000; Lo et al. 2001; Mo & Ballard, 2001). Thus, it was reasonable to hypothesise that adenosine might overcome the vasoconstrictor effects of increased MSNA during systemic hypoxia either by acting on A1 receptors on the endothelium and releasing prostacyclin and NO, or by acting directly on A1 receptors on the vascular smooth muscle (Edmunds & Marshall, 2001; Ray et al. 2002; Edmunds et al. 2003).

It is also widely accepted that the products of tissue hypoxia can act presynaptically on sympathetic varicosities to inhibit transmitter release (Vanhoutte et al. 1981). Specifically, adenosine can both inhibit and facilitate sympathetic transmission by acting on presynaptic A1 and A2A receptors (Vanhoutte et al. 1981; Maynard & Burnstock, 1994; Gonçalves & Quieroz, 1996). Such presynaptic effects might be produced by endothelium-derived adenosine or, more likely, by adenosine generated by the action of 5′ nucleotidase on ATP that is co-released with noradrenaline (NA; Burnstock, 1989; Gonçalves & Quieroz, 1996). The latter was of particular interest because we have shown that ATP exerts an important facilitatory role in the increases in hindlimb vascular resistance evoked by sympathetic stimulation, with natural, irregular patterns of sympathetic nerve activity containing both low- and high-frequency components and by a standard burst of 20 pulses at 20 Hz (Johnson et al. 2001). Furthermore, studies on isolated arteries indicated that ATP plays a small part in the constriction evoked by sympathetic stimulation at a constant low frequency, but becomes less important during continuous stimulation at > 5 Hz (Kennedy et al. 1986; Sjoblom-Widfeldt & Nilsson, 1990; Sjoblom-Widfeldt et al. 1990). It may be noted that previous studies on the effects of sympathetic stimulation on muscle vasculature have generally involved constant frequencies of > 5 Hz (e.g. Thomas & Victor, 1998).

Thus, we investigated the effects of graded levels of systemic hypoxia and of adenosine infusion on the vasoconstrictor responses evoked in rat hindlimb by three different patterns of MSNA applied to the sympathetic supply: a constant frequency of 2 Hz over 1 min and the same number of impulses delivered over 1 min in bursts of 20 impulses at 20 Hz or 40 Hz. At rest, the average frequency of MSNA is < 1 Hz (Macefield et al. 1994; Hudson, et al. 2002) and the instantaneous frequency within bursts can reach 20–50 Hz when sympathetic fibres are activated (Macefield et al. 1994; Johnson & Gilbey, 1996; Hudson et al. 2002). We investigated the effects of pharmacological antagonists of adenosine receptors upon the evoked responses, concentrating on A1 receptors. As a means of differentiating pre- and postsynaptic influences, we also tested the effects of systemic hypoxia on the responses evoked by NA infusion, before and after adenosine receptor blockade.

Some of these results have been presented in brief to The Physiological Society (Coney & Marshall, 1999a,b).

METHODS

Experiments were performed on five groups of male Wistar rats. All experiments were approved by UK legislation under the Home Office Animals (Scientific Procedures) Act 1986. Rats were initially anaesthetised with halothane (3.5 % in O2) to allow cannulation of a jugular vein for continuous infusion of the anaesthetic Saffan (Schering-Plough Animal Health, Welwyn Garden City, UK) at 7–12 mg kg−1 h−1, as we have described previously (Johnson et al. 2001). At the end of the experiments all of the animals were killed by anaesthetic overdose.

The surgical preparation of the animal and the recording techniques were essentially as we have described previously (Bryan & Marshall, 1999; Johnson et al. 2001). Briefly, the trachea was cannulated and the side-arm of the cannula was connected to a system of rotameters in a gas proportioner frame (CP Instruments, Hanwell, London, UK), which allowed the rats to breathe 21 % O2 in N2 or a hypoxic gas mixture, as described below. Both brachial arteries were cannulated, one being used to monitor arterial blood pressure (ABP), the other allowing 150 μl samples to be taken anaerobically for analysis by a blood gas analyser (IL1640; Instrumentation Laboratories, Warrington, Cheshire, UK): samples were taken in normoxia and during hypoxia following sympathetic stimulation. The caudal ventral tail artery was cannulated when necessary to allow infusion of NA or adenosine to the hindlimbs (see below). The left femoral vein was cannulated to allow administration of pharmacological antagonists.

A bipolar, silver-wire stimulating electrode was attached to the right lumbar sympathetic chain between L3 and L4 via a laparotomy, the great vessels being temporarily retracted to expose the sympathetic chain. The electrode tips were embedded in dental impression material (President, Light Body, Colténe, Switzerland) to both mechanically fix and electrically isolate them. The electrodes were used to deliver three different patterns of nerve stimulation at constant current via an isolated stimulator (DS2A; Digitimer, UK). The patterns were chosen to comprise the same number of 1 ms pulses at a constant current of 1 mA in a 1 min period, as follows: (1) continuous stimulation at 2 Hz, (2) a 20 Hz burst for 1 s repeated every 10 s (bursts at 20 Hz) and (3) a 40 Hz burst for 0.5 s repeated every 10 s (bursts at 40 Hz). Each pattern resulted in 120 impulses being delivered over the 1 min stimulation period.

Blood flow was recorded from the right femoral artery (FBF) via a perivascular flowprobe (0.7V; Transonic Systems, Ithaca, NY, USA) connected to a flowmeter (T106; Transonic Systems). ABP and FBF were acquired into Chart software (AD Instruments) via a MacLab/8 s (AD Instruments) at a sampling frequency of 100 Hz. Mean arterial pressure (MAP) and heart rate (HR) were derived on-line from the ABP signal, and femoral vascular resistance (FVR) was calculated on-line by the division of ABP by FBF.

Protocols

Group 1: sympathetic stimulation during adenosine infusion

In these experiments, the animals (n = 8, mean ±s.e.m. body weight: 212 ± 2 g) breathed 21 % O2 in N2 throughout. Responses evoked by the three different patterns of sympathetic nerve stimulation were recorded, sufficient time being allowed between stimuli for baselines to stabilise. Adenosine was then infused at 0.5 mg kg−1 min−1 via the caudal ventral artery, and once a new steady baseline was achieved the protocol was repeated. This infusion rate was chosen to produce a decrease in FVR approximately equivalent to 50 % of the change produced by breathing 8 % O2 (see below): previous studies have shown that ∼50 % of the muscle vasodilatation induced by 8 % O2 is mediated by adenosine (Bryan & Marshall, 1999). The infusion was stopped, baselines were allowed to recover again and then the adenosine A1 antagonist 1,3-dipropyl-8-cyclopentylxanthine (DPCPX) was given via the femoral vein at a dose of 0.1 mg kg−1 (Bryan & Marshall, 1999). The whole protocol was repeated as described above, all three patterns of sympathetic stimulation being delivered in random order without and during adenosine infusion.

Group 2: sympathetic stimulation during mild and moderate hypoxia

The response evoked by bursts at 40 Hz was tested in eight rats (mean ±s.e.m. body mass 208 ± 7 g) during normoxia (breathing 21 % O2 in N2). The inspirate was then switched to 12 % O2 in N2 and at least 1 min after a new steady baseline had been achieved, the response evoked by bursts at 40 Hz was re-tested. The inspiratory gas was then switched to 10 % O2 in N2 and the response evoked by bursts at 40 Hz was evaluated again. The inspirate was then returned to 21 % O2 in N2 and the animal allowed to recover for at least 10–15 min. Responses evoked in normoxia, and 12 and 10 % O2 were tested again as described above, but using bursts at 20 Hz. Following recovery, the protocol was repeated a third time using the third pattern: continuous stimulation at 2 Hz.

Group 3: sympathetic stimulation during severe hypoxia

This protocol was performed on 15 rats (mean ±s.e.m. body mass 208 ± 5 g). The response to sympathetic stimulation was tested essentially as described for group 2 except that the responses evoked by the three different patterns of sympathetic stimulation were each tested in random order during air-breathing and when breathing 8 % O2 in N2.

Groups 4a and b: severe hypoxia plus A1 or A2A receptor blockade

The protocol described for group 3 was performed in two groups of animals. In group 4a (n = 7; mean ±s.e.m. body mass 208 ± 7 g), responses evoked by the three different patterns of sympathetic stimulation were tested in normoxia and 8 % O2 before and in the presence of A1 receptor blockade: DPCPX was administered at 0.1 mg kg−1i.v. (Bryan & Marshall, 1999). In group 4b (n = 10; mean ±s.e.m. body mass 212 ± 2 g), the same protocol was performed before and after administration of the A2A receptor antagonist ZM241385 at 0.05 mg kg−1 (Bryan & Marshall, 1999).

Groups 5a and b: NA infusion

In 15 rats, NA was infused via the tail artery at 10 μg kg−1 min−1 over a 3 min period during air breathing. Following recovery, the inspirate was switched to 8 % O2 in N2 and the infusion of NA was repeated. Following recovery of baseline, either the adenosine A1 receptor antagonist DPCPX (group 5a, n = 9; mean ±s.e.m. body mass 215 ± 3 g) or the A2A receptor antagonist ZM241385 (group 5b, n = 6; mean ±s.e.m. body mass 257 ± 16 g) was given intravenously at the doses described for groups 4a and b. When baselines had stabilised again, responses evoked by NA infusion in normoxia and during 8 % O2 were re-tested.

Drugs

Adenosine and NA were purchased from Sigma (Poole, Dorset, UK) and dissolved in 0.95 % saline. DPCPX was purchased from RBI Biochemicals (Poole, Dorset, UK) and dissolved in 10 % DMSO/0.1 m NaOH (50/50 v/v) in saline. ZM241385 was purchased from Tocris Cookson (Bristol, UK) and dissolved in 3 % polyethylene glycol 400/0.1 m NaOH (50/50 v/v) in saline (as described by Bryan & Marshall, 1999).

Data analysis

All data are expressed as means ±s.e.m. FVR was computed on-line in mmHg ml−1 min. The size of the response to sympathetic stimulation was calculated as an integral by subtracting the integral of the baseline FVR calculated over the 1 min preceding the stimulus from the integral of the FVR recorded during the 1 min of the sympathetically evoked response. The response is expressed in arbitrary resistance units (RU). The same procedure was adopted for the responses evoked by NA infusion except that in this case integration was performed for the 3 min of the infusion and for a 3 min period preceding the infusion, and the values obtained were divided by three to allow direct comparison with the sympathetically evoked responses. Thus, comparisons could be made between responses evoked by different patterns of stimulation and NA infusion during normoxia, and between responses evoked from the new baseline values of FVR induced by adenosine infusion and various levels of systemic hypoxia.

Changes evoked in integrated FVR during normoxia and hypoxia, or adenosine infusion and before and after antagonist administrations were compared by repeated-measures ANOVA, followed by Tukey's post hoc test if P < 0.05. Responses evoked by different patterns of sympathetic stimulation in individual animals were compared by Student's paired t test.

It has been argued that the assessment of whether or not sympathetically evoked constriction is attenuated during muscle contraction is influenced by whether changes in vascular tone are calculated as vascular resistance or vascular conductance. In general, a more accurate estimate of change in vascular tone can be obtained when the variable that changes most is used as the numerator, rather than the denominator (see Hansen et al. 2000). In the present study, we routinely express our data in terms of changes in vascular resistance, firstly because our experimental interventions had much greater effects on ABP than on FBF (see Table 1), and secondly because we were interested in changes in the magnitude of the vasoconstrictor responses, which can vary over a wide range from baseline to infinity when expressed as vascular resistance. Nevertheless, to assess whether this choice affected our interpretation of the data, we also calculated vascular tone as vascular conductance. An example is shown as supplementary material (see end of paper for details) of the influence of adenosine infusion on responses evoked by sympathetic stimulation before and after DPCPX. If we had expressed vascular tone as vascular conductance, it would not have changed any of the deductions we have made below.

Table 1.

Baseline values of cardiovascular variables for all experimental groups

| MAP (mmHg) | FBF (ml min−1) | HR (beats min−1) | FVR (mmHg ml−1 min) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group 1 | ||||

| Control | 105 ± 5 | 1.59 ± 0.15 | 390 ± 17 | 71.6 ± 9.6 |

| Adenosine infusion | 79 ± 3*** | 1.51 ± 0.14 | 393 ± 17 | 59.0 ± 9.5* |

| Control + DPCPX | 112 ± 3 | 1.47 ± 0.13 | 417 ± 17† | 82.5 ± 9.4 |

| Adenosine infusion + DPCPX | 95 ± 2***††† | 1.37 ± 0.12 | 420 ± 18 | 76.6± 11.4† |

| Group 2 | ||||

| Control | 113 ± 3 | 1.67 ± 0.14 | 447 ± 12 | 64.0 ± 3.3 |

| Hypoxia(12% O2) | 81 ± 4*** | 1.44 ± 0.15** | 453 ± 13 | 54.9 ± 4.2 |

| Hypoxia(10% O2) | 71 ± 5*** | 1.32 ± 0.16** | 448 ± 15 | 56.6 ± 4.5 |

| Group 3 | ||||

| Control | 109 ± 3 | 1.76 ± 0.14 | 424 ± 12 | 67.7 ± 6.3 |

| Hypoxia(8% O2) | 64 ± 3*** | 1.53 ± 0.17 | 445 ± 10 | 46.5 ± 3.9 |

| Group 4a | ||||

| Control | 104 ± 5 | 1.87 ± 0.26 | 399 ± 16 | 60.6 ± 6.5 |

| Hypoxia(8% O2) | 68 ± 7*** | 1.92 ± 0.26 | 429 ± 15* | 37.2 ± 2.7 |

| Control + DPCPX | 113 ± 5† | 1.87 ± 0.26 | 421 ± 16 | 67.2 ± 8.1 |

| Hypoxia (8% O2) + DPCPX | 75 ± 7** | 1.74 ± 0.27 | 443 ± 27 | 49.1 ± 7.2 |

| Group 4b | ||||

| Control | 126 ± 7 | 1.96 ± 0.13 | 429 ± 7 | 62.7 ± 3.2 |

| Hypoxia (8% O2) | 75 ± 5*** | 2.03 ± 0.18 | 444 ± 8* | 38.2 ± 2.7 |

| Control + ZM241385 | 125 ± 3 | 1.91 ± 0.14 | 440 ± 10 | 68.4 ± 4.0 |

| Hypoxia (8% O2) + ZM241385 | 73 ± 5*** | 2.08 ± 0.15 | 442 ± 12 | 35.9 ± 2.4 |

| Group 5a | ||||

| Control | 118 ± 4 | 1.81 ± 0.14 | 429 ± 15 | 69.1 ± 6.2 |

| Hypoxia | 72 ± 7*** | 1.93 ± 0.14 | 414 ± 14 | 39 ± 4.3 |

| Control + DPCPX | 130 ± 4††† | 1.55 ± 0.09 | 430 ± 16 | 88.3 ± 8.3 |

| Hypoxia (8% O2) + DPCPX | 90 ± 6*** | 1.82 ± 0.17* | 448 ± 26 | 51.8 ± 5.1 |

| Group 5b | ||||

| Control | 118 ± 7 | 2.22 ± 0.14 | 408 ± 29 | 54.3 ± 3.83 |

| Hypoxia | 72 ± 8** | 2.36 ± 0.34 | 421 ± 35 | 35.8 ± 2.9 |

| Control + ZM241385 | 131 ± 6 | 2.34 ± 0.35 | 442 ± 15 | 61.0 ± 7.1 |

| Hypoxia (8% O2) + ZM241385 | 70 ± 4*** | 1.97 ± 0.08 | 432 ± 21 | 36.1 ± 2.3 |

Values are presented as means ±s.e.m.

Significant difference between baseline in hypoxia vs. normoxia. P < 0.05,

P < 0.01,

P < 0.001, respectively.

Significant difference between values recorded before and after antagonist. In each case 1, 2 and 3 symbols indicates

RESULTS

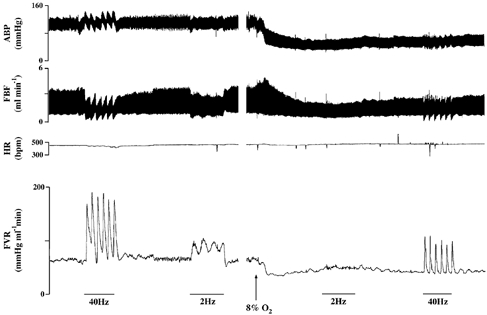

Figure 1 illustrates typical responses evoked by a bursting and by a continuous pattern of sympathetic stimulation during normoxia and severe hypoxia. The baseline values of the measured cardiovascular variables are shown in Table 1 for each of the protocols, during normoxia, hypoxia and after antagonist administration, while the corresponding values of arterial blood gases (arterial partial pressures of O2 (Pa,O2) and CO2 (Pa,CO2)) are shown in Table 2.

Figure 1. An example of raw data recorded during a bursting pattern (40 Hz) and a continuous pattern (2 Hz) of sympathetic nerve stimulation during normoxia and severe hypoxia.

Stimulation is indicated by the bars. Following 2 Hz stimulation in normoxia and prior to the start of 8 % O2, there was a period of 3 min of stable normoxic baseline, which has been omitted for illustration purposes.

Table 2.

Arterial blood gas values in all experimental groups during air breathing (control) or hypoxia (breathing 12, 10 or 8% O2)

| Pa,o2 (mmHg) | Pa,co2 (mmHg) | |

|---|---|---|

| Group 1 | ||

| Control | 87 ± 3 | 43 ± 1 |

| Control + DPCPX | 90 ± 2 | 39 ± 1** |

| Group 2 | ||

| Control | 100 ± 7 | 34 ± 1 |

| Hypoxia (12% O2) | 46 ± 2 | 29 ± 1 |

| Hypoxia (10% O2) | 39 ± 1 | 26 ± 1 |

| Group 3 | ||

| Control | 96 ± 3 | 38 ± 2 |

| Hypoxia (8% O2) | 33 ± 1 | 25 ± 1 |

| Group 4a | ||

| Control | 92 ± 2 | 41 ± 2 |

| Hypoxia (8% O2) | 34 ± 2 | 26 ± 1 |

| Control + DPCPX | 96 ± 6 | 40 ± 2 |

| Hypoxia (8% O2) + DPCPX | 37 ± 3 | 27 ± 2 |

| Group 4b | ||

| Control | 85 ± 2 | 42 ± 1 |

| Hypoxia (8% O2) | 29 ± 0.4 | 27 ± 1 |

| Control+ ZM241385 | 82 ± 2 | 44 ± 2 |

| Hypoxia (8% O2) + ZM241385 | 29 ± 1 | 27 ± 1 |

| Group 5a | ||

| Control | 90 ± 2 | 42 ± 1 |

| Hypoxia (8% O2) | 33 ± 1 | 32 ± 3 |

| Control + DPCPX | 101 ± 2** | 43 ± 2 |

| Hypoxia (8% O2) + DPCPX | 33 ± 1 | 28 ± 2 |

| Group 5b | ||

| Control | 87 ± 1 | 38 ± 2 |

| Hypoxia (8% O2) | 30 ± 2 | 27 ± 2 |

| Control + ZM241385 | 80 ± 2 | 40 ± 2 |

| Hypoxia (8% O2) + ZM241385 | 32 ± 1 | 26 ± 1 |

All values shown are means ±s.e.m.

P < 0.01 before vs. after the drug.

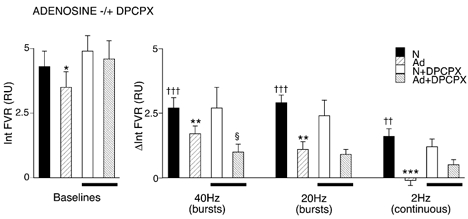

Group 1: sympathetic stimulation during adenosine infusion

Sympathetic stimulation with bursts at 40 or 20 Hz evoked increases in integrated FVR of 2.7 ± 0.4 and 2.9 ± 0.3 RU, respectively, whereas continuous stimulation at 2 Hz evoked a response of only 1.6 ± 0.3 RU (see Fig. 1 and Fig. 2). Thus, the bursting patterns of stimulations produced a larger response than continuous stimulation over the 1 min stimulation period (P < 0.05).

Figure 2. Effect of exogenous adenosine on vasoconstrictor responses evoked in hindlimb muscle by different patterns of sympathetic stimulation.

The graph on the left shows baseline values from which responses to sympathetic stimulation were evoked, as shown in the graph on the right. Conditions under which baselines and responses were evoked are shown by different shading (see key): breathing 21 % O2, normoxia (N), adenosine infusion (Ad), baselines and responses recorded during normoxia and during adenosine infusion after A1 blockade are shown as N + DPCPX and Ad + DPCPX, respectively, as indicated by bars below the columns. Baselines and responses are shown as the integral of FVR (Int FVR) and change in the integral of FVR from baseline (ΔInt FVR) over 1 min (mean ±s.e.m.). †Significant difference between the values recorded during sympathetic stimulation and baseline during normoxia. *Significant difference between values recorded during N and Ad. §Significant difference between the value recorded before and after DPCPX. In each case, 1, 2 and 3 symbols indicate P < 0.05, P < 0.01 and P < 0.001, respectively. Sympathetic fibres were stimulated with bursts at 40 or 20 Hz, or continuously at 2 Hz, as indicated below the columns. Each period of stimulation comprised 120 pulses over 1 min; for further details see text.

Adenosine infusion produced a fall in baseline MAP, FVR (Table 1) and integrated FVR of 0.6 ± 0.3 RU (see Fig. 2), ∼50 % of the fall induced by breathing 8 % O2 (see below). From this new baseline, the effect of adenosine infusion was to reduce the response to bursts at 40 Hz (1.7 ± 0.3 RU) and at 20 Hz (1.1 ± 0.3 RU) and to abolish the response to continuous stimulation at 2 Hz (−0.1 ± 0.2 RU; see Fig. 2).

Administration of the A1 receptor antagonist DPCPX had no effect on baseline values of any of the variables measured except HR, which showed a significant increase (see Table 1 and Bryan & Marshall, 1999). Furthermore, there was no effect on the responses evoked by the three different patterns of sympathetic stimulation under control conditions (Fig. 2). However, following DPCPX, adenosine infusion no longer caused a significant reduction in baseline FVR (i.e. the adenosine-induced vasodilatation was reduced; Fig. 2). When responses evoked by sympathetic stimulation were tested during adenosine infusion, the response evoked by bursts at 20 Hz was not significantly different from that evoked during adenosine infusion before DPCPX (Fig. 2). However, the response evoked by bursts at 40 Hz was further attenuated beyond that achieved during adenosine infusion before DPCPX (see Fig. 2). On the other hand, the response to continuous stimulation at 2 Hz was partially restored (see Fig. 2B), although the size of this response just failed to reach statistical significance as a change from baseline (P = 0.07).

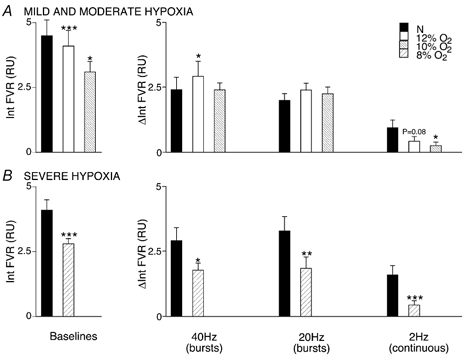

Group 2: sympathetic stimulation during mild and moderate hypoxia

As expected (see Bryan & Marshall, 1999), breathing 12 or 10 % O2 induced a reduction in MAP, FBF and FVR, indicating vasodilatation (Table 1; Fig. 3). While inspiring 12 % O2, the increase in FVR evoked by stimulation with bursts at 40 Hz was facilitated, whereas breathing 10 % O2 had no effect on this response (Fig. 3). The response evoked by burst stimulation at 20 Hz was not significantly affected by either mild or moderate hypoxia (Fig. 3). By contrast, the response evoked by continuous stimulation at 2 Hz was consistently reduced by breathing 12 % O2, although this effect just failed to reach statistical significance (P = 0.0514); it was significantly reduced by 10 % O2 (Fig. 3).

Figure 3. Effects of graded levels of systemic hypoxia on vasoconstrictor responses evoked in hindlimb muscle by different patterns of sympathetic stimulation.

The graphs on the left in A and B show baseline values of FVR recorded under different experimental conditions and those on the right show changes in FVR from baseline evoked by sympathetic stimulation as Int FVR and ΔInt FVR over 1 min, as described for Fig. 2. A, baseline and responses evoked in normoxia (breathing 21 % O2) and during mild and moderate hypoxia (breathing 12 and 10 % O2, respectively). B, baseline and responses evoked during normoxia and severe hypoxia (breathing 8 % O2). *Significant difference between the response evoked in normoxia and hypoxia. In each case, 1, 2 and 3 symbols indicate P < 0.05, P < 0.01 and P < 0.001, respectively. For simplicity, symbols have not been included for changes evoked by sympathetic stimulation (see Fig. 1); all changes were significant at the P < 0.001 or P < 0.01 levels.

Group 3: sympathetic stimulation during severe hypoxia

Breathing 8 % O2 produced a substantial fall in MAP and FVR (Table 1; Fig. 3). From this new baseline, the increases in FVR evoked by burst stimulation at 40 and at 20 Hz and by continuous stimulation at 2 Hz were greatly reduced (Fig. 3C). The increase in FVR evoked by burst stimulation at 40 or 20 Hz during 8 % O2 was significantly reduced by 26 and 34 %, respectively, of that evoked in normoxia, whereas that evoked by continuous stimulation at 2 Hz was reduced to a greater extent (68 % of that evoked in normoxia).

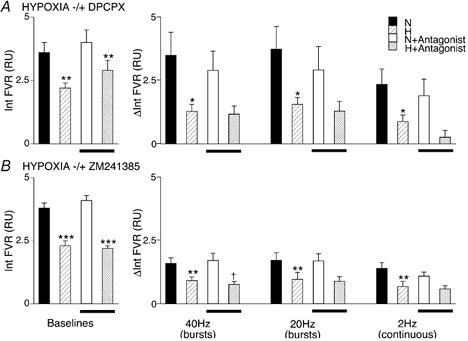

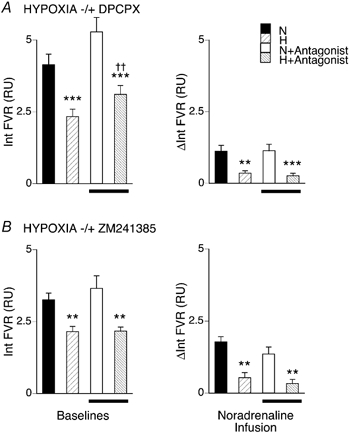

Group 4: severe hypoxia plus A1 or A2A receptor blockade

The effects of breathing 8 % O2 on FVR and on the increases in FVR evoked by the three different patterns of sympathetic stimulation were comparable with those described for group 3 (see Table 1 and Fig. 3 and Fig. 4): FVR was decreased during 8 % O2 and the sympathetically evoked responses were reduced. In group 4a, DPCPX reduced the decrease in FVR evoked by 8 % O2 (i.e. the hypoxia-induced vasodilatation was reduced; see above and Fig. 4A). However, from this new baseline, the response to burst stimulation at 40 Hz was comparable with that evoked by this pattern before DPCPX: the antagonist had no effect on the attenuation of the sympathetically evoked response caused by 8 % O2 (see Fig. 4). Similarly, DPCPX had no effect on the attenuation caused by 8 % O2 of the increases in FVR evoked by burst stimulation at 20 Hz, nor by continuous stimulation at 2 Hz (Fig. 4).

Figure 4. Effects of A1 or A2a receptor blockade on the attenuation produced by systemic hypoxia of vasoconstrictor responses evoked by different patterns of sympathetic stimulation in hindlimb muscle.

The graphs on the left in A and B show baseline values, and those on the right show changes in Int FVR, as described for Figs 2 and 3: N and H indicate baselines and changes recorded during normoxia (breathing 21 % O2) and hypoxia (breathing 8 % O2) respectively, bars below columns indicating values recorded after DPCPX (A) or ZM241385 (B). *Significant difference between values recorded during normoxia and hypoxia before or after antagonist. †Significant difference between values recorded before and after antagonist. For each case, 1, 2 and 3 symbols indicate P < 0.05, P < 0.01 and P < 0.001, respectively.

In group 4b, ZM241385 had no effect on baseline FVR in normoxia or on the decrease in FVR induced by 8 % O2 (Table 1, Fig. 4B): A2A receptor blockade did not affect the hypoxia-induced dilatation (see Bryan & Marshall, 1999). ZM241385 had no effect on the response evoked by burst stimulation at 40 Hz in normoxia, but further attenuated the response evoked by 8 % O2 (Fig. 4D). However, ZM241385 had no effect on the increases in FVR evoked by burst stimulation at 20 Hz, or by continuous stimulation at 2 Hz in either normoxia or hypoxia (Fig. 4D).

Group 5: NA infusion during normoxia and severe hypoxia

In group 5a, NA infused at 10 μg kg−1 min−1 for 3 min during normoxia evoked an increase in integrated FVR approximately equal to that evoked by continuous stimulation at 2 Hz. Hypoxia (breathing 8 % O2) produced the expected decrease in FVR (see above and Fig. 5), and the increase in FVR evoked by NA infusion was greatly reduced (see Fig. 5B). Administration of DPCPX had no significant effect on baseline variables in normoxia, except HR (see above and Table 1) and the response to NA infusion in normoxia was not affected (Fig. 5B). As expected, DPCPX reduced the decrease in FVR induced by 8 % O2 (Bryan & Marshall, 1999), but from this new baseline the increase in FVR evoked by NA infusion during hypoxia was fully comparable to that evoked in hypoxia before DPCPX (Fig. 5); it was greatly depressed compared to that achieved in normoxia.

Figure 5. Effects of hypoxia on the vasoconstriction evoked in hindlimb muscle by NA infusion before and after A1 or A2a blockade.

The graphs on the left show baseline values and changes in Int FVR over 1 min evoked by NA infusions, as described for Figs 2 and 3. N and H indicate values recorded during normoxia and hypoxia (breathing 21 % or 8 % O2, respectively). Bars below columns indicate values recorded after DPCPX (A) or ZM241385 (B). *Significant difference between values recorded during normoxia and hypoxia before or after antagonist. †Significant difference between values recorded before and after antagonist. In each case, 1, 2 and 3 symbols indicate P < 0.05, P < 0.01 and P < 0.001, respectively.

In group 5B, NA infusion in normoxia again evoked an increase in integrated FVR that was attenuated in hypoxia (see Fig. 5B). As expected, administration of the A2A receptor antagonist ZM241385 did not affect the decrease in FVR evoked by hypoxia (see Table 1, Fig 5B and Bryan & Marshall, 1999). Nor did it affect the increases in FVR evoked by NA in normoxia (see Fig. 5B).

Discussion

In the present study, we show for the first time that vasoconstrictor responses evoked in rat hindlimb muscle by three different patterns of sympathetic nerve stimulation are reduced in a graded manner by graded levels of systemic hypoxia. We also show that adenosine, which plays a major role in the muscle vasodilatation of systemic hypoxia, when infused into muscle during normoxia can attenuate the vasoconstrictor responses evoked by sympathetic stimulation. However, the results we obtained with A1 and A2A receptor antagonists indicate that the hypoxia-induced attenuation of sympathetically evoked vasoconstrictor responses is not attributable to the actions of adenosine.

In normoxia, the increases in FVR evoked by bursts at 20 or 40 Hz were consistently larger than those evoked by the same number of impulses delivered at a constant 2 Hz. This is consistent with the results of previous in vivo and in vitro studies and with the view that irregular patterns of MSNA as occur naturally are more effective than regular discharge (Pernow et al. 1989; Sjoblom-Widfeldt et al. 1990). NA is mainly responsible for the underlying constriction during all patterns of sympathetic stimulation, and neuropeptide Y may contribute at higher frequencies (see Pernow et al. 1989; Morris & Gibbins, 1992). However, as indicated in the Introduction, in vivo and in vitro studies indicate that nerve-released ATP plays an important facilitatory role in the muscle vasoconstriction evoked by low- and high-frequency components of natural sympathetic discharge, a burst of 20 pulses at 20 Hz, and to a lesser extent by constant stimulation at 2 Hz (Kennedy et al. 1986; Sjoblom-Widfeldt & Nilsson, 1990; Johnson et al. 2001). Thus, the vasoconstrictor responses evoked by all of the patterns of sympathetic stimulation used in the present study might have been expected to be attenuated by adenosine generated from nerve-released ATP, as well as by adenosine originating from the endothelium (see Introduction).

Certainly, infusion of adenosine into the hindlimb not only produced vasodilatation, but also considerably reduced the vasoconstrictor responses evoked by the three different patterns of sympathetic stimulation, the most vulnerable being that evoked by continuous stimulation at 2 Hz. Thus, exogenous adenosine has the potential to attenuate sympathetically evoked vasoconstriction in muscle. A similar finding was made by Smits et al. (1991) who showed that adenosine infused into the human forearm attenuated the reflex vasoconstriction evoked by lower-body negative pressure. However, the A1 receptor antagonist DPCPX did not ameliorate the adenosine-induced attenuation of vasoconstrictor responses evoked by bursts of 40 or 20 Hz, and only partially reversed the attenuation of the response evoked by stimulation at a constant 2 Hz. Thus, in normoxia the attenuating effect of adenosine on sympathetically evoked muscle vasoconstriction is largely independent of the A1 receptors that are responsible for the muscle vasodilatation observed in systemic hypoxia (Bryan & Marshall, 1999). The fact that DPCPX augmented the adenosine-induced attenuation of the increase in FVR evoked by bursts at 40 Hz raises the possibility that exogenous adenosine can act on presynaptic A1 receptors to facilitate NA release in skeletal muscle vasculature, as described for rabbit ear artery in vitro (Maynard & Burnstock, 1994).

During graded systemic hypoxia, increases in FVR evoked by stimulation at 2 Hz were progressively reduced, while those evoked by burst stimulation were attenuated by severe hypoxia only. A1 receptor blockade with DPCPX reduced the muscle vasodilatation of severe systemic hypoxia (see Bryan & Marshall, 1999), but had no effect on the hypoxia-induced impairment of the muscle vasoconstriction evoked by any of the patterns of sympathetic stimulation. Thus, these results suggest strongly that stimulation of A1 receptors by locally released adenosine does not interfere with the ability of sympathetically released co-transmitters to cause vasoconstriction in hypoxia during constant low-frequency, or burst stimulation, either directly by acting on the endothelium or vascular smooth muscle to cause vasodilatation (Ray et al. 2002; Edmunds et al. 2003), or indirectly by inhibiting NA release (Vanhoutte et al. 1981; Gonçalves & Quieroz, 1996).

As there are A2A receptors in hindlimb muscle that can be stimulated by exogenous adenosine to induce vasodilatation (Bryan & Marshall, 1999), it remained a possibility that endogenously generated adenosine might impair sympathetically evoked vasoconstriction via A2A receptors, even though it does not contribute to hypoxia-induced vasodilatation via these receptors (Bryan & Marshall, 1999). However, the A2A receptor antagonist ZM241385 also failed to reduce the hypoxia-induced attenuation of the vasoconstriction evoked by any of the three patterns of sympathetic stimulation. In fact, ZM241385 augmented the attenuation produced by severe hypoxia of the response to stimulation with bursts at 40 Hz. This may be attributed to endogenous adenosine acting presynaptically on A2A receptors to facilitate NA release, as demonstrated for rat tail artery in vitro (Gonçalves & Quieroz, 1996). It is improbable that adenosine originating from the endothelium in systemic hypoxia diffuses through the vascular smooth muscle to act presynaptically on sympathetic varicosities located at the adventitial medial border, for such adenosine would also be expected to act on A2A receptors on the vascular smooth muscle to cause vasodilatation (Poucher, 1996; Bryan & Marshall, 1999). Rather, it is more likely that adenosine generated locally from nerve-released ATP acts on presynaptic A2A receptors. Such a presynaptic facilitatory action of adenosine may also explain why mild and moderate hypoxia did not attenuate, or even facilitate, responses evoked by bursts at 20 or 40 Hz (Fig. 3). A facilitatory action of adenosine would help protect against the hypotension, vasovagal syncope and eventual circulatory collapse that can occur in severe hypoxia (Rowell & Seals, 1990; Marshall, 1999).

Finally, it is possible that the presynaptic actions of adenosine in systemic hypoxia obscured our ability to discern a postsynaptic inhibitory effect of adenosine on muscle vasoconstriction evoked by nerve-released NA. When tested directly, infused-NA-evoked increases in FVR that were approximately similar in magnitude to those evoked by sympathetic stimulation at 2 Hz were similarly attenuated by severe hypoxia. Thus, the attenuating effect of systemic hypoxia upon the sympathetically evoked vasoconstrictor responses may be largely attributed to effects on the postsynaptic actions of NA. However, neither A1 nor A2A receptor blockade altered this attenuating effect. This reinforces our conclusion that endogenous adenosine does not contribute to the attenuating effect of systemic hypoxia upon sympathetically evoked vasoconstriction.

Considering alternative explanations, it is unlikely that prostanoids are involved, for although prostacyclin contributes to the muscle vasodilatation of systemic hypoxia, our recent study indicates that it is generated as a consequence of A1 receptor stimulation (Ray et al. 2002). It might be that the NO generated by eNOS or nNOS contributes, as suggested for the apparently similar attenuation of sympathetically evoked vasoconstriction that occurs during muscle contraction (see Introduction and Hansen et al. 2000). Consistent with this possibility, the muscle vasodilatation of systemic hypoxia is NO-dependent (Skinner & Marshall, 1996; Edmunds & Marshall, 2001). However, providing a tonic level of NO is restored after NO synthase inhibition by infusion of an NO donor, then not only is the hypoxia-induced dilatation restored and mediated by adenosine acting on A1 receptors (Edmunds et al. 2003), but the hypoxia-induced attenuation of sympathetic vasoconstriction also persists (see Bishay et al. 2000; Coney & Marshall, unpublished observations). This will be considered in a separate paper.

A further possibility is that hypoxia per se inhibits the ability of NA to cause vasoconstriction. This issue has received much attention. Of particular relevance, in rat iliac arteries, reduction in bath PO2 from ∼100 to 70, 55 or 40 mmHg, over the range of Pa,O2 values achieved in the present study, produced a graded depression of NA-evoked contraction that reflected inhibition of contraction evoked by one of the α1 adrenoceptor subtypes (Bartlett & Marshall, 2002) and was attributable to hypoxia-induced inhibition of NA-evoked Ca2+ influx (see Ebeigbe, 1982; Pearce et al. 1992; Franco-Obregon & Lopez-Barneo, 1996). Further, vasoconstriction mediated by α2 adrenoceptors, which are found mainly on the distal arterioles of skeletal muscle, is particularly vulnerable to hypoxia because α2-mediated closure of KATP channels is inhibited (Tateishi & Faber, 1995). It remains to be established whether such effects of hypoxia on α1- and/or α2-mediated responses contribute to the effects of hypoxia on sympathetically evoked changes in FVR.

In summary, the present study has shown that graded levels of systemic hypoxia reduce the vasoconstrictor responses evoked in skeletal muscle by sympathetic nerve stimulation at constant low frequency and by burst stimulation at 20 or 40 Hz, the latter being less vulnerable. Although adenosine plays a major role in the vasodilatation induced in skeletal muscle by systemic hypoxia by acting on A1 receptors, the attenuating effect of systemic hypoxia upon sympathetically evoked constriction cannot be attributed to adenosine. At most, adenosine released in hypoxia may exert a presynaptic facilitatory influence via A2A receptors, on vasoconstriction evoked by burst stimulation.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the British Heart Foundation.

Supplementary material

The online version of this paper contains a page of supplementary material: http://www.jphysiol.org/cgi/content/full/549/2/613 DOI: 10.1113/jphysiol.2003.042267 and contains material entitled: Effects of exogenous adenosine on vasoconstrictor responses evoked in hindlimb muscle by different patterns of sympathetic stimulation expressed as femoral vascular resistance (FVR) and femoral vascular conductance (FVC)

References

- Bartlett IS, Marshall JM. Analysis of the effects of graded levels of hypoxia on noradrenaline-evoked contraction in the rat iliac artery in vitro. Exp Physiol. 2002;87:171–184. doi: 10.1113/eph8702341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bishay M, Coney AM, Johnson CD, Marshall JM. Role of nitric oxide in vasoconstriction evoked in skeletal muscle of the rat by different patterns of sympathetic stimulation. J Physiol. 2000;523:249P. [Google Scholar]

- Bryan PT, Marshall JM. Adenosine receptor subtypes and vasodilatation in rat skeletal muscle during systemic hypoxia: a role for A1 receptors. J Physiol. 1999;514:151–162. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1999.151af.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burnstock G. Vascular control by purines with emphasis on the coronary system. Eur Heart J. 1989;10:15–21. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/10.suppl_f.15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coney AM, Marshall JM. Modulation by adenosine of vasoconstriction evoked in rat skeletal muscle by different patterns of sympathetic nerve stimulation. J Physiol. 1999a;515:142P. [Google Scholar]

- Coney AM, Marshall JM. Systemic hypoxia differentially modulates vasoconstriction of rat skeletal muscle evoked by different patterns of sympathetic nerve stimulation. J Physiol. 1999b;518:177P. [Google Scholar]

- Ebeigbe AB. Influence of hypoxia on contraction and calcium uptake in rabbit aorta. Experientia. 1982;38:935–937. doi: 10.1007/BF01953662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edmunds NJ, Marshall JM. Vasodilatation, oxygen delivery and oxygen consumption in rat hindlimb during systemic hypoxia: roles of nitric oxide. J Physiol. 2001;532:251–259. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2001.0251g.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edmunds NJ, Moncada S, Marshall JM. Does nitric oxide allow endothelial cells to sense hypoxia and mediate hypoxic vasodilatation?In vivo and in vitro studies. J Physiol. 2003;546:521–527. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2002.023663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franco-Obregon A, Lopez-Barneo J. Low P O2 inhibits calcium channel activity in arterial smooth muscle cells. Am J Physiol. 1996;271:H2290–2299. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1996.271.6.H2290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonçalves J, Quieroz G. Purinoceptor modulation of noradrenaline release in rat tail artery: tonic modulation mediated by inhibitory P2Y- and facilitatory A2A-purinoceptors. Br J Pharmacol. 1996;117:156–160. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1996.tb15168.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansen J, Sander M, Thomas GD. Metabolic modulation of sympathetic vasoconstriction in exercising skeletal muscle. Acta Physiol Scand. 2000;168:489–503. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-201x.2000.00701.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hudson S, Johnson CD, Coney AM, Marshall JM. Changes in sympathetic nerve activity recorded from skeletal muscle arteries of the anaesthetised rat during graded levels of systemic hypoxia. J Physiol. 2002;544:28P. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson CD, Coney AM, Marshall JM. Roles of norepinephrine and ATP in sympathetically evoked vasoconstriction in rat tail and hindlimb in vivo. Am J Physiol. 2001;281:H2432–2440. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.2001.281.6.H2432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson CD, Gilbey MP. On the dominant rhythm in the discharges of single postganglionic sympathetic neurones innervating the rat tail artery. J Physiol. 1996;497:241–259. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1996.sp021764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy C, Saville VL, Burnstock G. The contributions of noradrenaline and ATP to the responses of the rabbit central ear artery to sympathetic nerve stimulation depend on the parameters of stimulation. Eur J Pharmacol. 1986;122:291–300. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(86)90409-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leuenberger UA, Gray K, Herr MD. Adenosine contributes to hypoxia induced forearm vasodilation in humans. J Appl Physiol. 1999;87:2218–2224. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1999.87.6.2218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lo SM, Mo FM, Ballard HJ. Interstitial adenosine concentration in rat red or white skeletal muscle during systemic hypoxia or contractions. Exp Physiol. 2001;86:593–598. doi: 10.1113/eph8602226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macefield VG, Wallin BG, Valbo AB. The discharge behaviour of single vasoconstrictor motoneurones in human muscle nerve. J Physiol. 1994;481:799–809. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1994.sp020482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marshall JM. Peripheral chemoreceptors and cardiovascular regulation. Physiol Rev. 1994;74:543–594. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1994.74.3.543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marshall JM. Circulatory hypoxia. In: Sibbald WJ, Messmer K, Fink MP, editors. Tissue Oxygenation in Acute Medicine, Update in Intensive Care and Emergency Medicine. Vol. 3. Berlin: Springer Verlag; 1999. pp. 98–115. [Google Scholar]

- Marshall JM. Adenosine and muscle vasodilatation in acute systemic hypoxia. Acta Physiol Scand. 2000;168:561–573. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-201x.2000.00709.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maynard KI, Burnstock G. Evoked noradrenaline release in the rabbit ear artery: enhancement by purines, attenuation by neuropeptide Y and lack of effect of calcitonin gene-related peptide. Br J Pharmacol. 1994;112:123–126. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1994.tb13040.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mian R, Marshall JM. The role of adenosine in dilator responses induced in arterioles and venules of rat skeletal muscle by systemic hypoxia. J Physiol. 1991;443:499–511. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1991.sp018847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mo FM, Ballard HJ. The effect of systemic hypoxia on interstitial and blood adenosine AMP, ADP and ATP in dog skeletal muscle. J Physiol. 2001;536:593–603. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2001.0593c.xd. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris JL, Gibbins IL. Co-transmission and neuromodulation. In: Burnstock G, Hoyle CHV, editors. Autonomic Neuroefffector Mechanisms. Switzerland: Harwood; 1992. pp. 33–119. [Google Scholar]

- Pearce WJ, Ashwal S, Long DM, Cuevas J. Hypoxia inhibits calcium influx in rabbit basilar and carotid arteries. Am J Physiol. 1992;262:H106–113. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1992.262.1.H106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pernow J, Schwieler J, Kahan T, Hjemdahl P, Oberle J, Wallin BG, Lundberg JM. Influence of sympathetic discharge pattern on norepinephrine and neuropeptide-Y release. Am J Physiol. 1989;257:H866–872. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1989.257.3.H866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poucher SM. The role of A2a adenosine receptor subtype in functional hyperaemia in the hindlimb of anaesthetized cats. J Physiol. 1996;492:495–503. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1996.sp021324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ray CJ, Abbas MR, Coney AM, Marshall JM. Interactions of adenosine, prostaglandins and nitric oxide in hypoxia-induced vasodilatation: in vivo and in vitro studies. J Physiol. 2002;544:195–209. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2002.023440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rowell LB, Johnson DG, Chase PB, Comess KA, Seals DR. Hypoxemia raises muscle sympathetic activity but not norepinephrine in resting humans. J Appl Physiol. 1989;66:1736–1743. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1989.66.4.1736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rowell LB, Seals DR. Sympathetic activity during graded central hypovolemia in hypoxemic humans. Am J Physiol. 1990;259:H1197–1206. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1990.259.4.H1197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saito M, Mano T, Iwase S, Koga K, Abe H, Yamazaki Y. Responses in muscle sympathetic activity to acute-hypoxia in humans. J Appl Physiol. 1988;65:1548–1552. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1988.65.4.1548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sander M, Chavoshan B, Harris SA, Iannaccone ST, Stull JT, Thomas GD, Victor RG. Functional muscle ischaemia in neuronal nitric oxide synthase deficient skeletal muscle of children with Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:13464–13466. doi: 10.1073/pnas.250379497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sjöblom-Widfeldt N, Gustafsson H, Nilsson H. Transmitter characteristics of small mesenteric arteries from the rat. Acta Physiol Scand. 1990;138:203–212. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-1716.1990.tb08834.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sjöblom-Widfeldt N, Nilsson H. Sympathetic transmission in small mesenteric arteries from the rat: influence of impulse pattern. Acta Physiol Scand. 1990;183:523–528. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-1716.1990.tb08880.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skinner MR, Marshall JM. Studies on the roles of ATP, adenosine and nitric oxide in mediating muscle vasodilatation induced in the rat by acute systemic hypoxia. J Physiol. 1996;495:553–560. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1996.sp021615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smits P, Lenders JWM, Willemsen JJ, Thien T. Adenosine attenuates the response to sympathetic stimuli in humans. Hypertension. 1991;18:216–223. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.18.2.216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun M-K, Reis DJ. Decerebration does not alter hypoxic sympathoexcitatory responses in rats. J Auton Nerv Syst. 1995;53:77–81. doi: 10.1016/0165-1838(94)00175-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tateishi J, Faber JE. ATP-sensitive K+ channels mediate α2D-adrenergic receptor contraction of arteriolar smooth muscle and reversal of contraction by hypoxia. Circ Res. 1995;76:53–63. doi: 10.1161/01.res.76.1.53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas GD, Hansen J, Victor RG. ATP-sensitive potassium channels mediate contraction-induced attenuation of sympathetic vasoconstriction in rat skeletal muscle. J Clin Invest. 1997;99:2602–2609. doi: 10.1172/JCI119448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas GD, Victor RG. Nitric oxide mediates contraction-induced attenuation of sympathetic vasoconstriction in rat skeletal muscle. J Physiol. 1998;506:817–826. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1998.817bv.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vanhoutte PM, Verbeuren TJ, Webb RC. Local modulation of adrenergic neuroeffector modulation in the blood vessel wall. Physiol Rev. 1981;61:151–247. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1981.61.1.151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

The online version of this paper contains a page of supplementary material: http://www.jphysiol.org/cgi/content/full/549/2/613 DOI: 10.1113/jphysiol.2003.042267 and contains material entitled: Effects of exogenous adenosine on vasoconstrictor responses evoked in hindlimb muscle by different patterns of sympathetic stimulation expressed as femoral vascular resistance (FVR) and femoral vascular conductance (FVC)