Abstract

Muscle satellite cells are mononuclear cells that remain in a quiescent state until activated when they proliferate and fuse with muscle fibres to donate nuclei, a process necessary for post-embryonic growth, hypertrophy and tissue repair in this post-mitotic tissue. These processes have been associated with expression of the insulin-like growth factor (IGF-I) gene that can undergo alternative splicing to generate different gene products with varying functions. To gain insight into the cellular mechanisms involved in local tissue repair, the time courses of expression of two IGF-I splice variants produced in muscle were determined together with marker genes for satellite cell activation following local muscle damage. Using real-time RT-PCR with specific primers, the mRNA transcripts in rat tibialis anterior muscles were measured at different time intervals following either mechanical damage imposed by electrical stimulation of the stretched muscle or damage caused by injection with bupivacaine. It was found that the autocrine splice variant mechano growth factor (MGF) was rapidly expressed and then declined within a few days following both types of damage. Systemic IGF-IEa was more slowly upregulated and its increase was commensurate with the rate of decline in MGF expression. Satellite cell activation as measured by M-cadherin and one of the muscle regulatory factors MyoD and the sequence of expression suggests that the initial pulse of MGF is responsible for satellite cell activation, as the systemic IGF-IEa mRNA expression peaks after the expression of these markers, including M-cadherin protein. Later splicing of the IGF-I gene away from MGF but towards IGF-IEa seems physiologically appropriate as IGF-IEa is the main source of mature IGF-I for upregulation of protein synthesis required to complete the repair.

It has been realised for some time that there must be local factors as well as systemic factors that regulate tissue growth and initiate local tissue repair. In post-mitotic tissues such as neuronal tissue, and cardiac and skeletal muscle in which there is no significant cell replacement throughout life, the cells do sustain local damage from time to time. This is particularly true for a mechanical tissue such as muscle. Therefore, there has to be an efficient method of initiating local repair to avoid subsequent cell death resulting in a permanent deficit.

Insulin-like growth factor (IGF-I) produced by the liver and induced by growth hormone, is a main systemic regulator of tissue mass during postnatal growth. Published work indicates that insulin-like growth factors are also involved in tissue maintenance and the prevention of cell death as general regulators of protein synthesis and the activation of muscle satellite (stem) cells that are required for local muscle repair (for review see Adams, 1998). However, it is now appreciated that the IGF-I gene gives rise to several different splice variants that have different actions (reviewed by Stewart & Rotwein, 1996) and that these may involve different receptors (Yang & Goldspink, 2002).

The cDNAs of IGF-I splice variants that are expressed in muscle have been cloned in rat and human (Yang et al. 1996). These include one that is the same as the main systemic IGF-IEa produced by the liver and another that has been called mechano growth factor (MGF), as its mRNA was only detected in normal muscle after mechanical stimulation (Yang et al. 1996; McKoy et al. 1999). The classification of the IGF-I peptides is not satisfactory when applied to different species and to non-hepatic tissues in which their expression is regulated by hormones. For example, MGF would be classified as IGF-IEb in the rat, but as IGF-IEc in the human. From its sequence, MGF is derived from the IGF-I gene by alternative splicing and has different 3′ exons to the liver or systemic type (IGF-IEa). It has a 49 base pair insert in the human, and a 52 base pair insert in rodents, within the E domain of exon 5. This insert results in a reading frame shift, with a different carboxy (C) terminal sequence to that of systemic IGF-IEa. MGF and the other IGF isoforms have the same 5′ exons that encode the IGF-I ligand-binding domain. Processing of pro-peptide yields a mature peptide that is involved in upregulating protein synthesis. However, there is evidence that the carboxy-terminal of the MGF peptide also acts as a separate growth factor. This stimulates division of mononucleated myoblasts or satellite (stem) cells, thereby increasing the number available for local repair (Yang & Goldspink, 2002).

During the early stage of skeletal muscle development, myoblasts fuse to form syncytial myotubes, which become innervated and develop into muscle fibres. Thereafter, mitotic proliferation of nuclei within the muscle fibres ceases. However, during postnatal growth additional nuclei are provided by satellite cells fusing with muscle fibres. Muscle damage-recovery seems to have a similar cellular mechanism, in that satellite cells become activated and fuse with the damaged muscle fibres (reviewed by Goldring et al. 2002). This is also pertinent to certain diseases such as muscular dystrophy in which muscle tissue is not maintained and which have been associated with a deficiency in active satellite (stem) cells (Megeney et al. 1996; Seale & Rudnicki, 2000) and in myogenic factors (Heslop et al. 2000). Skeletal muscle mass and regenerative capacity have also been shown to decline with age (Sadeh, 1988; Carlson et al. 2001). The reduced capacity to regenerate in older muscle seems to be due to the decreased ability to activate satellite cell proliferation (Chakravarthy et al. 2000). The markedly lower expression of MGF in older rat muscles (Owino et al. 2001) and human muscle (Hameed et al. 2003) in response to mechanical overload has been associated with the failure to activate satellite cells, leading to age-related muscle loss (Owino et al. 2001).

It is known that muscles sustain mechanical damage, particularly when they are activated whilst being stretched (eccentric contractions). This causes damage to the myofibrillar system (Brooks & Faulkner, 2001) and to the plasma membrane (Petrof et al. 1993). Therefore, a system that involves electrically stimulating an individual muscle whilst it is held in the stretched position is a reasonable simulation of what happens in life. Muscles also sustain damage in other ways such as from free radicals, ischaemia, thermal injury, viruses, venoms and other myotoxic agents. To determine whether the expressions of the systemic type IGF-IEa and the autocrine/paracrine splice variant MGF respond to local damage per se, experiments were carried out using the myotoxic agent bupivacaine. As shown some years ago, bupivacaine, when injected into an individual muscle, induces extensive damage to the myofibrillar system, which virtually disappears but recovers within two weeks or so following the injection (Hall-Craggs, 1974; Bradley, 1979). These methods of inducing reproducible local tissue damage, combined with real-time PCR using specific primers for the different IGF-I splice variants and marker genes for satellite cells and satellite cell activation, were employed to measure the time course and levels of expression of these genes in relation to local repair of muscle tissue. The satellite cells, which are regarded as multipotent stem cells (Goldring et al. 2002), are usually located at the periphery of the muscle fibres, between the basement membrane and the plasma membrane, and after activation they multiply and fuse with the muscle fibres. These events involve a change in expression of adhesion molecules, as exemplified by M-cadherin (M-cad), followed by transcription of myogenic factors such as MyoD, which are involved in muscle tissue specific expression (Cornelison & Wold, 1997). Therefore, changes in expression of these markers of satellite cell activation were also measured in addition to IGF-IEa and MGF using real-time RT-PCR to establish the time frame for their expression in relation to satellite cell activation following local injury.

METHODS

All animal procedures were in accord with current UK legislation and covered by Home Office project and personal licences under the Animals (Scientific Procedures) Act 1986.

Mechanically induced local damage

Sprague-Dawley rats (250–300 g, 10–12 weeks of age at the start of the experiment) were divided equally into experimental groups for different time points, and one sham-operated group plus one normal control group (n = 6 per group). Anaesthesia was induced at a rate of 3 % halothane in oxygen at a flow rate of 2 l min−1 and maintained at approximately 1–2 % halothane. The left hindlimb was immobilised in plantar flexion using a fibreglass cast. Care was taken to ensure that the blood flow to the foot was not compromised, by omission of plaster cast around the ankle and by placing a cotton bud on the hindlimb to ensure casting was not too tight. Whilst the animals were still anaesthetised, the tibialis anterior (TA) muscle was electrically stimulated after making a small incision and inserting stainless steel electrodes on either side of the peroneal nerve. These were then attached to a micro-stimulation circuit. When activated, the stimulators delivered bi-directional pulses of 1 ms duration, supra-maximal intensity (3 V) at a frequency of 10 Hz for 1 h (protocol according to McKoy et al. 1999). At the end of the stimulation, absorbable sutures (VICRYL 4/0) were used to close the incision and 0.3 ml of an analgesic (Tamgesic) was given subcutaneously. Animals regained consciousness 10–15 min later. Animals were regularly monitored to ensure that there was no swelling of the limb due to tight casting and that the sutures were still in place. If oedematous conditions were observed these animals were immediately killed. After 1, 5 and 7 days, groups of rats subjected to stretch combined with stimulation together with sham-operated controls were killed using CO2 and cervical dislocation. In all groups the contralateral limb was also examined and served as a sub-control group. The sham-operated controls were rats in which the electrode wires were placed on either side of the peroneal nerve but the electrical stimulation circuit was not switched on. A group of rats of the same age which had been subjected to no stretch or stimulation were used as normal controls.

Myotoxin-induced local damage

Sprague-Dawley rats (250–300 g, 10–12 weeks of age at the start of the experiment) were also used for these experiments. They were divided into seven groups, five experimental groups for different time intervals, a saline-injected group and a normal muscle control group (n = 6 per group). Anaesthesia was induced as described above. The left hindquarter of the rat was shaved to assist location of the TA and 0.3 ml of either 0.5 % bupivacaine hydrochloride (l-butyl-2′,6′-pipecoloxylidide hydrochloride; Sigma) in 0.9 % sodium chloride or 0.9 % sodium chloride alone was injected into the middle of the TA muscle. A 26 gauge, 13 mm long needle was introduced at the midpoint of the muscle, inserted at an angle and advanced proximally along the longitudinal axis of the muscle. Animals regained consciousness 10–15 min later. Animals were regularly monitored to ensure that they were not in pain during the recovery period. Sham control groups were animals that received an injection of 0.9 % physiological saline and in all cases the contralateral as well as the experimental muscles were analysed.

Morphological assessment of muscle fibre damage, repair and satellite cell activation

Details of the histological/histochemical methods for this part of the study will be published elsewhere (Hill et al. 2003). Briefly, this involved taking cryostat sections of the muscles from the experimental animals, some of which were stained using the conventional haematoxylin and eosin (H and E) method, to determine the area of damage. A monoclonal antibody to embryonic myosin heavy chain (MyHc330) was used to assess regeneration and a rabbit polyclonal primary antibody to M-cad (from Professor A. Wernig, University of Bonn, Germany) was used to visualise the activated satellite cells using the protocol according to Irintchev et al. (1994). For measurements of M-cad staining density, a minimum of five random fields per section were acquired from three sections per slide, from a minimum of four animals per time point by using fluorescence illumination with standardised imaging conditions for all specimens. Images were acquired using a Nikon TE300 inverted microscope with fluorescence attachment (Nikon, UK) and low light level, peltier-cooled, CCD camera (Photonic Science, UK), controlled by Kontron KS400 image analysis software (Zeiss Microscience, UK).

RNA isolation and cDNA preparation for internal controls

The single-step method of RNA isolation using acid guanidinium thiocyanate-phenol-chloroform (after Chomczynski & Sacchi, 1987) was used to isolate total RNA, the concentration of which was measured in a Genespec spectophotometer (Shimatzu). First strand cDNA synthesis for RT-PCR was performed using a Roche Diagnostics kit. Specific primers for IGF-IEa, MGF, MyoD and M-cad were then used for the determination of the levels of these transcripts by real-time RT-PCR. Levels were determined simultaneously and runs were carried out in triplicate to determine the mean values for gene expression in picograms per microgram of total RNA. A negative control was present in each run, in which the template DNA was replaced with PCR-grade water.

Analysis of real-time RT-PCR

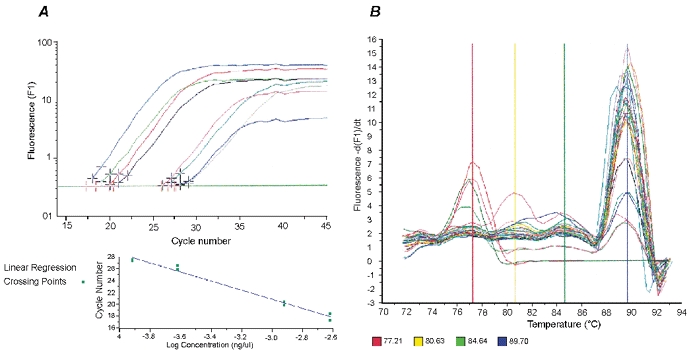

Real-time RT-PCR is highly sensitive and allows quantification of transcripts in low abundance. In this study a LightCycler machine (Roche Diagnostics) was used. Incorporation of the fluorescent dye SYBR Green I during real-time PCR permits the detection and quantification of newly synthesised DNA, as well as verification of product authenticity using the in-built melting curve analysis procedure.

SYBR Green I dye binds to the minor groove of double-stranded (ds) DNA and therefore fluorescent signals of different intensities can be detected during the various stages of PCR, depending on the amount of dsDNA present. During denaturation of dsDNA to single-stranded DNA, SYBR Green I is released. Upon annealing, specific PCR primers hybridise to the target sequence, resulting in small parts of dsDNA to which SYBR Green I dye binds and fluorescence intensity increases. Finally, in the elongation phase when the PCR primers are extended, the entire DNA target becomes double-stranded, and a maximum amount of dye is bound. Fluorescence is recorded at the end of the elongation phase and increasing amounts of PCR products are monitored from cycle to cycle and visualised in real-time as they occur.

One potential problem of this method occurs when a signal is generated by binding of SYBR Green I to double-stranded by-products such as primer-dimers, which result from non-specific annealing and primer elongation events. These events occur as soon as PCR reagents are combined. The formation of primer-dimers competes with formation of PCR product, leading to reduced amplification efficiency and a less successful PCR. Therefore, a ‘hot start’ method was used, in which an anti-Taq DNA polymerase antibody was added to the reaction mixture to inactivate the enzyme until the temperature reached about 70 °C. A typical experimental protocol using the appropriate primers (Table 1) contained four programs (initial denaturation, amplification, melting curve and cooling) and the levels of specific mRNA were determined per microgram of total RNA and confirmed by melting analysis (as seen in Fig. 1).

Table 1.

Primers used to quantify IGF-lEa and MGF by RT-PCR and real-time PCR, with their annealing temperatures in each amplification protocol

| Tα for | Tα for real-time | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Primer name | Sequence 5′-3′ | RT-PCR (°C) | PCR (°C) |

| IGF-IEaF | GCTTGCTCACCTTTACCAGC | 60 | 61 |

| IGF-lEa R | AATGTACTTCCTTCTGGGTCT | ||

| MGF-F | GCTTGCTCACCTTTACCAGC | 60 | 55 |

| MGF-R | AAATGTACTTCCTTTCCTTCTC | ||

| MyoD-F | GGAGACATCCTCAAGCGATGC | 60 | 60 |

| MyoD-R | AGCACCTGGTAAATCGGATTG | ||

| M-cadF | ATGTGCCACAGCCACATCG | 60 | 60 |

| M-cad R | TCCATACATGTCCGCCAGC | ||

| GAPDHF | CCACCAACTGCTTAGCACC | 60 | 60 |

| GAPDH R | GCCAAATTCGTTGTCATACC | ||

| MGF-rt | TTGCAGGTTGCT | — | — |

Tα, annealing temperature. F, forward primer;R, reverseprimer; rt, reverse transcription primer.

Figure 1. Real-time RT-PCR analysis.

A, analysis screen (top panel) using the Fit Point method in the Roche LightCycler protocol for quantification of specific gene expression. The software uses the selected number of points to calculate a ‘best fit’ long, linear fluorescence curve for each sample. The intersection (marked with a red cross) of this line with the Crossing Line (green horizontal line) is the so-called Crossing Point (expressed as a fractional cycle number, i.e. a cycle number that is calculated to two decimal places). All the Crossing Points of the standards are used to plot a graph of cycle number vs. log concentration (lower panel). This standard curve is used to estimate the concentration of each sample. B, example of a melting curve for MGF LightCycler PCR product: the melting temperature of MGF PCR product was 89.7 °C (blue vertical line) and those of the primer-dimers were lower than 82 °C (yellow and red vertical lines). An extra window with a temperature approximately 10 °C higher than that of the elongation temperature was set during the amplification program; this melted the unspecific LightCycler products at 89 °C and eliminated any non-specific fluorescence signals.

Each dsDNA product has its own specific melting temperature (Tm), which is defined as the temperature at which 50 % of the DNA becomes single-stranded and the rest remains double-stranded. This is determined by the length and G + C content of the fragment. Once the amplification cycles are completed, confirmation of the sequence of the amplified product is achieved by melting curve analysis. During this analysis, products are denatured at 95 °C, annealed at a specific temperature (usually 5–10 °C higher than that of the PCR annealing temperature) and then slowly heated to 95 °C, with fluorescence being measured after every 0.2 °C increase. A positive standard is used as a control for each PCR run. This is a pre-run sample adjusted for concentration and other running parameters in the LightCycler. During the PCR run, melting temperatures of the unknown samples were compared with that of the control to separate the target and confirm the PCR signal from those of non-specific products (signals generated by the by-products have a Tm lower than that of the specific product). Hence, small amounts of sequences of interest could be identified through the melting curve analyses.

Statistical analyses were performed using two-way ANOVA to take into account variation between normal muscles of the control animals and variation between experimental groups.

RESULTS

Extent of muscle damage and rate of recovery

Five days following stretch and stimulation, the experimental muscles were approximately 12 % less in mass than the sham or contralateral control muscles (P < 0.001) and there was no significant difference between the two types of control muscles. The damaged muscles then recovered and there was no significant difference in mass between these and the controls by 14 days after mechanical damage. The bupivacaine-injected muscles showed a reduction of about one-third of their weight by 4 days after treatment (P < 0.001). By 14 days they were not significantly different in weight and by 24 days they were about 10 % heavier than the controls (P < 0.01). The extent of damage and repair was also studied using morphological criteria but these data will be published elsewhere (Hill et al. 2003). Briefly, the damaged area, as measured by H and E staining and analysis, reached a maximum at 5 days. The muscle fibre damage was no longer evident in the case of mechanical damage by 10 days but recovery from the myotoxin damage took about twice as long. It was apparent that in both cases the local damage to the individual muscle was extensive but following this the repair processes were rapid.

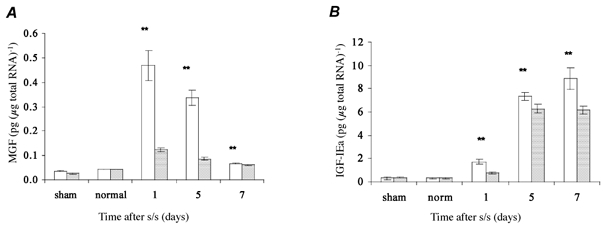

Expression of IGF-I isoforms following mechanical damage

MGF expression showed a maximal increase in the stretched and stimulated muscle after 1 day, but decreased thereafter (Fig. 2A). At all time points, MGF transcript levels in the damaged muscles were significantly different from those that were appreciably above zero in either the sham-operated or normal control groups. As both forms of IGF-I are derived from the same gene, it is noteworthy that the expression of MGF peaked several days before that of IGF-IEa (Fig. 2B) and then declined. Thus, following muscle damage, MGF is expressed quite rapidly and then splicing switches expression to lGF-lEa, which is sustained for a considerably longer time. Interestingly, both the contralateral muscles and the stretched and stimulated muscles showed increased IGF-IEa levels, which indicated a difference in the regulation of these two growth factors, as the contralateral muscles did not show the same increase in MGF expression.

Figure 2. Quantification of MGF and IGF-IEa transcript levels following mechanical damage.

Here and in subsequent figures: s/s, stretch and stimulation. A, there was a significant increase (**P < 0.001) in MGF level in the stretched and stimulated muscle compared to those in the sham and contralateral controls. MGF peaked at 1 day after treatment and decreased thereafter. B, a significant increase (**P < 0.001) in IGF-IEa level, showing maximum expression at day 7, was also demonstrated in the stretched and stimulated muscle compared to those in the sham-operated and normal control muscle groups. Interestingly, the contralateral control (right) muscles, which received increased use in these animals, expressed almost as much IGF-IEa as the damaged muscles. □, left TA, experimental;

, right TA, contralateral. For all groups n = 6. Values are expressed as means ±s.e.m.

, right TA, contralateral. For all groups n = 6. Values are expressed as means ±s.e.m.

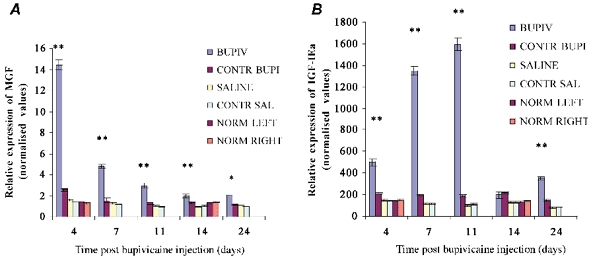

Expression of IGF-I isoforms in myotoxin-damaged, regenerating and normal muscle

MGF and IGF-IEa were also locally upregulated, for a period of 24 days, in muscle during regeneration following myotoxin damage (Fig. 3). Levels of both IGF-I transcripts in the bupivacaine-injected group were compared with those in the contralateral TA muscle, the saline-injected and the non-injected controls, normalised against an internal standard, glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH). Figure 3A and B shows that the expressions of both MGF and IGF-IEa were significantly higher (**P < 0.001) in the damaged muscle than in the control groups, including the saline-injected and non-injected groups, which showed no significant changes in expression of any of the transcripts.

Figure 3. Quantification of MGF and IGF-IEa transcript levels normalised against GAPDH, following bupivacaine injection.

A, MGF levels in the bupivacaine-injected group were significantly higher (**P < 0.001) compared with those of their contralateral muscle and of the saline-injected and non-injected groups from day 4 to day 14 and significantly higher (*P < 0.05) at day 24. MGF levels in the bupivacaine-injected group peaked at day 4 and decreased thereafter. B, IGF-IEa levels were also significantly higher (**P < 0.001) in the bupivacaine-injected group compared to those of their contralateral muscle and of the saline-injected and non-injected groups at 4, 7, 11 and 24 days. IGF-IEa expression was seen to peak 11 days after myotoxin injury, by which time MGF expression had declined considerably. For all groups n = 6. Values are expressed as normalised means ± normalised standard error of the mean (s.e.m.).

Again, the maximal levels and the time sequences of expression of MGF and IGF-IEa mRNA differed during the period following induced muscle damage. Four days after myotoxic damage in the bupivacaine-treated muscles, both MGF and IGF-IEa mRNA levels showed an increase, with the increased being particularly marked for MGF. However, expression of IGF-IEa mRNA increased until 11 days after injection, in contrast with MGF expression, which peaked much earlier. From day 0 to day 4, MGF expression showed a noticeable 10-fold increase in damaged muscle compared to that in normal muscle. In contrast, during the same period, IGF-IEa levels in damaged muscle increased just over three times compared with those in normal muscle.

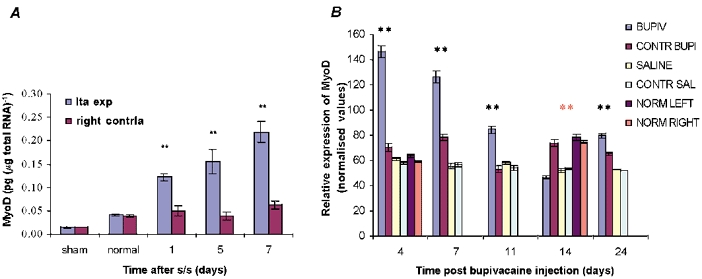

Expression of MyoD in response to mechanical activity and myotoxin-damaged muscle

Measurements of mRNA expression of the transcription factor MyoD in response to mechanical activity (Fig. 4A) showed that the satellite cell marker gene was significantly upregulated by day 1 and progressively that this increased to day 7. MyoD RNA levels were significantly higher (**, P < 0.001) in the stretched and stimulated TA muscles compared with those in their contralateral muscles and the normal control groups at all time points. In the stretched and stimulated group, MyoD mRNA levels in the contralateral muscles were similar at the three different time points to those of the sham controls, yet significantly higher than those of normal muscle.

Figure 4. Quantification of MyoD transcript levels following stretch and stimulation and bupivacaine injection.

A, there was a significant increase (**P < 0.001) in MyoD levels (pg (μg total RNA)−1)in the stretched and stimulated tibialis anterior (TA) muscle at all time points compared to the levels in sham and normal control groups. B, MyoD levels in the bupivacaine-damaged TA and control groups were normalised against GAPDH expression. There was a gradual decrease in MyoD mRNA levels in the bupivacaine-injected TA muscle from day 4 to day 14, with significant differences from control values (**P < 0.001). Orange asterisks indicate statistically significant increases in levels of MyoD in the contralateral and normal muscles compared to those in bupivacaine-injected muscle. For all groups n = 6. Values are expressed as normalised means ± normalised s.e.m.

In order to relate the expression of MGF and IGF-IEa to the de novo myogenesis associated with the muscle regeneration process, MyoD was also studied following bupivacaine-induced damage, normalised to GAPDH expression (Fig. 4B). The expression of MyoD mRNA was significantly higher (**P < 0.001) in the bupivacaine-injected TA muscle than in the control muscle groups until day 11 (Fig. 4B). Values for the same control groups throughout the 24 days of expression were essentially the same.

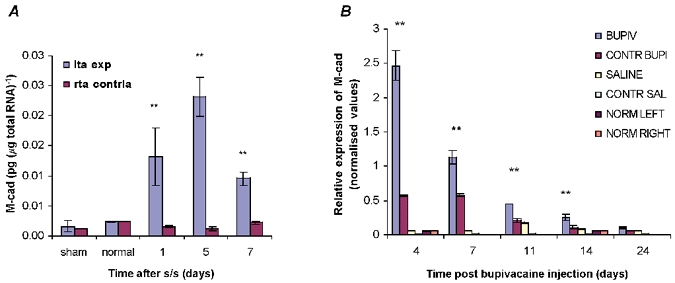

Expression of M-cad in stretched and stimulated, and myotoxin-damaged TA muscle

Measurements of M-cad transcript levels are shown in Fig. 5A for the stretch and stimulation study. M-cad expression was significantly higher in stretched and stimulated TA muscle at all three time points compared with the levels in the contralateral muscle, sham and normal control muscle groups. M-cad expression showed relatively similar values amongst the control groups at all time points.

Figure 5. Quantification of M-cad mRNA following stretch and stimulation and bupivacaine injection.

A, there was a significant increase (**P < 0.001) in levels of M-cadherin (M-cad) RNA (pg (μg total RNA)−1) in the stretched and stimulated TA muscle compared to those in the sham control and normal groups at all time points. M-cad showed maximal expression at day 5. B, changes in M-cad protein density levels with time following bupivacaine injection and after mechanical damage. Note that, at the protein level, M-cad gene expression also reaches a maximum after only 5 days. Thereafter it declines. This maximum is preceded by expression of MGF but not IGF-IEa. For all groups n = 6. Values are in arbitrary units as normalised means ± normalised s.e.m.

M-cad protein expression was analysed by the densitometry staining procedure, as explained in the Methods section, during the 24 day muscle regeneration in response to myotoxin damage (Fig. 5B). M-cad levels in the damaged group were significantly higher (**, P < 0.001) than those in the control groups until day 14. The M-cad protein showed maximal expression at the first time point, day 4 post bupivacaine injection, with a gradual decrease reaching control levels by day 24 (Fig. 5B). The expression pattern of M-cad in the bupivacaine-injected group seemed to follow a trend similar to that seen for MGF expression during recovery following damage, as seen in Fig. 3A.

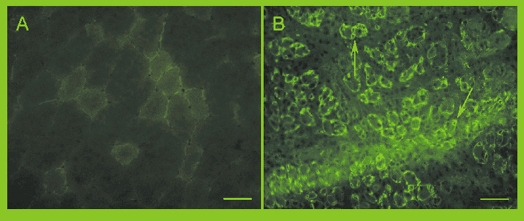

When frozen sections stained with anti-M-cad antibody were examined, some M-cad-labelled nuclei were detected in the sham and normal control muscles. There was also some background staining and, when the base line of the image analysers was adjusted to remove this, the detection of small amounts of staining in the quiescent satellite cells was lost (Rosenblatt et al. 1999). However, the increase in M-cad expression at 5 days after stretch and stimulation indicated that there were apparently many more activated satellite nuclei (Fig. 6).

Figure 6.

M-cad staining in cross-sections of a non-injected control TA muscle (A) and a bupivacaine-injected TA muscle 4 days after recovery (B) where M-cad-positive rings can be seen staining the satellite cells underneath the basal lamina in the small regenerating fibres (arrows). Scale bar = 50 μm.

DISCUSSION

The data presented here strongly support previous evidence (Yang & Goldspink, 2002) that the IGF-I splice variant MGF acts as a separate autocrine growth and repair factor to systemic IGF-IEa or liver type IGF-I, which is also expressed in muscle following damage. In accordance with the recent findings by Gregory Adams's group in California, which has studied insulin signalling in relation to exercise (Haddad & Adams, 2002), it was found that the kinetics of expression is different for these two IGF-I splice variants. The present data show that MGF expression peaked after just 1 day whilst the IGF-IEa transcript peaked at 7 days following mechanical damage. It is probable that MGF is expressed even earlier, but 1 day was the earliest time point used as it was felt that the rats should be allowed 1 day to recover from anaesthesia (Fig. 2A). It is interesting to note that after 1 day the decrease in MGF expression was accompanied by a reciprocal increase in IGF-IEa. This indicates that, following mechanical stimulation or muscle damage, the IGF-I gene is first spliced to produce MGF and then later to produce the more common IGF-IEa transcript. There was a similar time sequence of expression during repair following bupivacaine damage, with MGF and IGF-IEa expression peaking a little later at 4 and 11 days, respectively.

The data in Fig. 2A and B suggest that the two forms of IGF-I are expressed in response to slightly different mechanical signals. For instance, the contralateral controls of the stretched and stimulated muscles expressed markedly increased levels of IGF-IEa that were almost as high as in the damaged muscle. This is presumably because there was greater continuous but not intensive use of the contralateral muscles during the time the animal was recovering from surgery. In contrast, MGF expression in the same contralateral muscles was much lower than in the damaged muscles and only just significantly higher than in the normal and sham-operated controls. The response of these different splice variants to mechanical signals is in accord with experiments in which myocytes were stretched in vitro and it was seen that MGF was expressed in response to simple ramp stretch but not to repeated simusoidal studies, which only stimulated IGF-IEa production (U. Cheema, R. A. Brown, M. Eastwood, V. Mudera, D. A. McGrouther & G. Goldspink, unpublished observations).

Evidence that these two splice variants of IGF-I have different functions is demonstrated by recent in vitro experiments by Yang & Goldspink (2002) in which C2C12 myoblasts were transfected with plasmid vectors containing MGF or IGF-IEa cDNAs. The actions of these two growth factors differed, as MGF caused rapid proliferation of mononucleated myoblasts but inhibited terminal differentiation into myotubes. In contrast, IGF-IEa increased the mitotic index and also enhanced terminal differentiation as measured by creatine kinase expression and myotube formation. Similar results to those of the transfection experiments were obtained using the peptides obtained from these splice variants. It was found that only the E domain in the carboxy terminal sequence of MGF was required to activate myoblast proliferation and for them to remain in the mononucleated state. Unlike the action of IGF-IEa, this could not be blocked using an antibody to the IGF-I receptor.

The work described in the present paper provides further evidence that MGF and IGF-IEa act as different growth factors, which not only have different expression kinetics but also apparently have different functions. MGF expression preceded the activation of quiescent residual mononuclear myoblasts, or satellite cells, which are regarded as muscle stem cells. This also occurred in the bupivacaine-treated muscles and thus it may appear that MGF (mechano growth factor) has been misnamed. However the local damage induced by this myotoxin would undoubtedly result in greater mechanical strain in the surrounding cells. In early development, myoblasts proliferate and then fuse to form myotubes that become innervated to form functional muscle fibres. Following fusion, no further mitosis occurs within the muscle fibres and the extra nuclei required for post-embryonic growth are derived from the satellite cells, which then become programmed to express muscle genes. Thus, although muscle is regarded as a post-mitotic tissue, extra nuclei are required for tissue repair and the continued maintenance of muscle mass (Grounds & Yablonka-Reuveni, 1993; Owino et al. 2001). IGF-I has been implicated in the activation of satellite cells (for a review see Adams, 1993). However, it is now appreciated that there are different types of IGF-I and it was not known which splice variant was likely to be involved in the initial activation of satellite cells. In dystrophic muscles it seems that there is an inability to produce MGF in response to mechanical overload (Goldspink et al. 1996). The systemic type of IGF-IEa is also produced by muscle, including dystrophic muscle, but this alone does not ensure muscle fibre survival. Therefore a study of the role of IGF-I, particularly the splice variant MGF in relation to muscle wasting diseases seems to be very relevant to understanding their aetiology.

MGF appears to have a dual action in that, like the other IGF-I isoforms, it upregulates protein synthesis as well as activating satellite cells. However, the latter role of MGF is probably more important as most of the mature IGF-I will be derived from IGF-IEa during the second phase of repair. Nevertheless, it has been shown that MGF is a potent inducer of muscle hypertrophy in experiments in which the cDNA of MGF was inserted into a plasmid vector and introduced by intramuscular injection. This resulted in a 20 % increase in the weight of the injected muscle within 2 weeks, and the analyses showed that this was due to an increase in the size of the muscle fibres (Goldspink, 2001). Similar experiments by other groups have also been carried out using a viral construct containing the liver type of IGF-I, which resulted in a 25 % increase in muscle mass, but this took over 4 months to develop (Musaro et al. 2001). Hence, the dual role MGF plays in inducing satellite cell activation as well as protein synthesis suggests it is much more potent than the liver type or IGF-IEa for inducing rapid hypertrophy.

Transgenic mice have been generated that overexpress the systemic IGF-I (Mathews et al. 1988), and IGF-I has been locally overexpressed in the muscle of mice by viral-mediated gene transfer (Barton-Davis et al. 1998, 1999). These showed a marked increase in muscle weight and bone mass. Although these authors describe the IGF-I as muscle-specific IGF-I, it is important to realise that the IGF-I used in these cases was muscle specific because it was under the control of muscle regulatory elements that had been spliced into the vector (Musaro et al. 2001). Transgenic experiments have been performed in which the IGF-I gene has been ‘knocked out’ in liver cells using the Cre Lox method (Liu et al. 2000). Surprisingly, the mice grew normally, although serum levels of IGF-I were not elevated (Yakar et al. 1999). These latter experiments demonstrate the importance of the locally produced IGF-I splice variants, including MGF, in muscle tissue growth and maintenance.

In conclusion, the work described here demonstrates that the IGF-I gene is differentially spliced in response to local muscle overload and damage. Initially, it is spliced to produce mainly the MGF splice variant and this appears to initiate muscle satellite (stem) cell activation. This provides the extra undamaged nuclei required for muscle fibre repair with some upregulation of protein synthesis. Thereafter, the splicing switches towards producing systemic IGF-IEa, which upregulates protein synthesis over a somewhat longer time scale. Overexpression of IGF-I splice variants, whether they are induced by hormone or local muscle damage, will no doubt be extended beyond that required for local repair and result in the type of muscle hypertrophy shown by weightlifters and athletes involved in power events. The question still needs to be answered as to whether local muscle damage is a prerequisite for muscle hypertrophy and whether the adaptation to an increased load is really a manifestation of repeated injury and repair resulting in overexpression of these two growth factors.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by research grants from the Wellcome Trust, the EC (PENAM) project and the International Olympic Games (WADA) Committee to Professor Goldspink. Maria Hill received an Anatomical Society of Great Britain and Ireland research studentship. The antibody to M-cad was kindly supplied by Professor A. Wernig of the University of Bonn, Germany.

REFERENCES

- Adams GR. Exercise effects on muscle insulin signaling and action. Invited review: autocrine/paracrine IGF-I and skeletal muscle adaptation. J Physiol. 1993;96:1159–1162. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.01264.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adams GR. Role of insulin-like growth factor-I in the regulation of skeletal muscle adaptation to increased loading. Exerc Sport Sci Rev. 1998;26:31–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barton-Davis ER, Shoturma DI, Musaro A, Rosenthal N, Sweeney HL. Viral mediated expression of insulin-like growth factor I blocks the aging related loss of skeletal muscle function. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:15603–15607. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.26.15603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barton-Davis ER, Shoturma DI, Sweeney HL. Contribution of satellite cells to IGF-I induced hypertrophy of skeletal muscle. Acta Physiol Scand. 1999;167:301–305. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-201x.1999.00618.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradley WG. Muscle fibre splitting. In: Mauro A, editor. Muscle Regeneration. New York: Raven Press Ltd; 1979. pp. 215–232. [Google Scholar]

- Brooks SV, Faulkner JA. Severity of contraction-induced injury is affected by velocity only during stretches of large strain. J Appl Physiol. 2001;91:661–666. doi: 10.1152/jappl.2001.91.2.661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlson BM, Dedkov EI, Borisov AB, Faulkner JA. Skeletal muscle regeneration in very old rats. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2001;56:B224–233. doi: 10.1093/gerona/56.5.b224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chakravarthy MV, Abraha TW, Schwartz RJ, Fiorotto ML, Booth FW. Insulin-like growth factor BI extends in vitro replicative life span of skeletal muscle satellite cells by enhancing G l/S cell cycle progression via the activation of phosphatidylinositol 3′-kinase/Akt signalling pathway. J Biol Chem. 2000;46:35942–35952. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M005832200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chomczynski P, Sacchi N. Single-step method of RNA isolation by acidguanidinium thiocyanate-phenol-chloroform extraction. Anal Biochem. 1987;1162:156–159. doi: 10.1006/abio.1987.9999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cornelison DD, Wold BJ. Single-cell analysis of regulatory gene expression in quiescent and activated mouse skeletal muscle satellite cells. Dev Biol. 1997;191:270–283. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1997.8721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldring K, Partridge T, Watt D. Muscle stem cells. J Pathol. 2002;197:457–467. doi: 10.1002/path.1157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldspink G. Method of treating muscular disorders. United States Patent 6, 221, 842B1 April 24th.

- Goldspink G, Yang SY, Skarli M, Vrbova G. Local growth regulation is associated with an isoform of IGF-I that is expressed in normal muscle but not in dystrophic muscle when subjected to stretch. J Physiol. 1996;496.P:162P–163P. [Google Scholar]

- Grounds MD, Yablonka-Reuveni Z. Molecular and cell biology of skeletal muscle regeneration. Mol Cell Biol Hum Dis Ser. 1993;3:210–256. doi: 10.1007/978-94-011-1528-5_9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haddad F, Adams GR. Exercise effects on muscle insulin signalling and action selected contributions: Acute cellular and molecular responses to resistance exercise. J Appl Physiol. 2002;93:394–403. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.01153.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall-Craggs ECB. Rapid degeneration and regeneration of a whole skeletal muscle following treatment with bupivacaine (Marcaine) Br J Exp Path. 1974;61:139–149. doi: 10.1016/0014-4886(74)90176-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hameed M, Orrell RW, Cobbold M, Goldspink G, Harridge SDR. Expression of IGF-I splice variants in young and old human skeletal muscle after high resistance exercise. J Physiol. 2003;547:247–254. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2002.032136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heslop L, Morgan JE, Partridge TA. Evidence for a myogenic stem cell that is exhausted in dystrophic muscle. J Cell Sci. 2000;113:2299–2308. doi: 10.1242/jcs.113.12.2299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill M, Wernig A, Goldspink G. Muscle satellite (stem) cell activation during local tissue injury and repair. J Anat. 2003 doi: 10.1046/j.1469-7580.2003.00195.x. in the Press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Irintchev A, Zeschnigk M, Starzinski-Powitz A, Wernig A. Expression pattern of M-cadherin in normal, denervated and regenerating mouse muscle. Dev Dyn. 1994;199:326–337. doi: 10.1002/aja.1001990407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu JL, Yakar S, Le Roith D. Conditional knockout of mouse insulin-like growth factor-1 gene using the Cre/loxP system. Proc Soc Exp Biol Med. 2000;223:344–351. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1373.2000.22349.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKoy G, Ashley W, Mander J, Yang SY, Williams N, Russell B, Goldspink G. Expression of insulin-like growth factor-I splice variant and structural genes in rabbit skeletal muscle induced by stretch and stimulation. J Physiol. 1999;516:583–592. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1999.0583v.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathews LS, Hammer RE, Brinster RL, Palmiter RD. Expression of insulin-like growth factor I in transgenic mice with elevated levels of growth hormone is correlated with growth. Endocrinology. 1988;123:433–437. doi: 10.1210/endo-123-1-433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Megeney LA, Kablar B, Garrett K, Anderson JE, Rudnicki MA. MyoD is required for myogenic stem cell function in adult skeletal muscle. Genes Dev. 1996;10:1173–1183. doi: 10.1101/gad.10.10.1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Musaro A, McCullagh K, Paul A, Houghton L, Dobrowolny G, Molinaro M, Barton ER, Sweeney HL, Rosenthal N. Localized IGF-I transgene expression sustains hypertrophy and regeneration in senescent skeletal muscle. Nat Genet. 2001;27:195–200. doi: 10.1038/84839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Owino V, Yang SY, Goldspink G. Age-related loss of skeletal muscle function and the inability to express the autocrine form of insulin-like growth factor-l (MGF) in response to mechanical overload. FEBS Lett. 2001;505:259–263. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(01)02825-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petrof BJ, Shragger JB, Stedman HH, Kelly AM, Sweeney HL. Dystrophin protects the sarcolemma from stresses developed during muscle contraction. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1993;90:3710–3714. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.8.3710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenblatt JD, Cullen MJ, Irintchev A, Wernig A. M-cadherin is a reliable molecular marker of satellite cells in mouse skeletal muscle. Eur J Physiol. 1999;437:R145. [Google Scholar]

- Sadeh M. Effects of aging on skeletal muscle regeneration. J Neurol Sci. 1988;87:67–74. doi: 10.1016/0022-510x(88)90055-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seale P, Rudnicki MA. A new look at the origin, function and ‘stem-cell’ status muscle satellite cells. Dev Biol. 2000;106:115–124. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1999.9565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart CE, Rotwein P. Growth, differentiation, and survival: multiple physiological functions for insulin-like growth factors. Physiol Rev. 1996;76:1005–1026. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1996.76.4.1005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yakar S, Lib JL, Stannard B, Butler A, Accili D, Saner B, Leroith D. Normal growth and development in the absence of hepatic insulin-like growth factor I. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96:7324–7329. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.13.7324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang SY, Alnaqeeb M, Simpson H, Goldspink G. Cloning and characterization of an IGF-I isoform expressed in skeletal muscle subjected to stretch. J Muscle Res Cell Motil. 1996;17:487–495. doi: 10.1007/BF00123364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang SY, Goldspink G. Different roles of the IGF-I Ec peptide (MGF) and mature IGF-I in myoblast proliferation and differentiation. FEBS Lett. 2002;522:156–160. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(02)02918-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]