Abstract

The electrophysiological effects of d-myo-inositol 1,3,4,5,6-pentakisphosphate (InsP5) and d-myo-inositol hexakisphosphate (InsP6), which represent the main cellular inositol polyphosphates, were studied on L-type Ca2+ channels in single myocytes of rat portal vein. Intracellular infusion of InsP5 (up to 50 μm) or 10 μm InsP6 had no action on Ba2+ current, whereas 50 μm InsP6 or 10 μm InsP5 plus 10 μm InsP6 (InsP5,6) stimulated the inward current. The stimulatory effect of InsP5,6 was also obtained in external Ca2+-containing solution. The stimulated Ba2+ current retained the properties of L-type Ba2+ current and was oxodipine sensitive. PKC inhibitors Ro 32-0432 (up to 500 nm), GF109203X (5 μm) or calphostin C (100 nm) abolished the InsP5,6-induced stimulation. Neither the PKA inhibitor H89 (1 μm) nor the protein phosphatase inhibitors okadaic acid (500 nm) or cypermethrin (1 μm) prevented or mimicked the InsP5,6-induced stimulation of Ba2+ current. However, InsP5 or InsP6 could mimic some effects of protein phosphatase inhibitor so as to extend after washing-out forskolin the stimulatory effects of the adenylyl cyclase activator on Ba2+ current. These results indicate that InsP5 and InsP6 may act as intracellular messengers in modulating L-type Ca2+ channel activity and so could be implicated in mediator-induced contractions of vascular smooth muscle cells.

Voltage-gated Ca2+ channels are key proteins in the regulation of Ca2+ homeostasis and contraction in rat portal vein myocytes. The activity of these channels is regulated by membrane depolarization but modulation by protein kinases is essential (Keef et al. 2001).

In rat portal vein, one of the most potent vasoconstrictor agents, angiotensin II (AII), increases the intracellular Ca2+ concentration by stimulating L-type Ca2+ channels. The signalling pathway leading to this cellular response involves the Gα13β1γ3 protein-coupled AT1A receptor, a phosphoinositide 3-kinase γ (PI3Kγ) and a protein kinase C (PKC) (Macrez et al. 1997; Viard et al. 1999; Quignard et al. 2001). However, different pathways also regulate vascular L-type Ca2+ channels. Stimulation of β-adrenergic receptors or adenylyl cyclase induces an increase in the amplitude of the L-type Ba2+ current via a protein kinase A (PKA)-dependent pathway (Viard et al. 2001).

Intracellular messengers generated by phospholipase C (PLC) may modulate L-type Ca2+ channels, such as, for example, diacylglycerol, which can activate PKC and then Ca2+ channels (Touyz & Schiffrin, 2000). Inositol-1,4,5-trisphosphate (InsP3) produced by PLC leads to the generation of other inositol polyphosphates (InsPs), such as inositol tetrakis- (InsP4), pentakis- (InsP5) and hexakisphosphates (InsP6) through the action of several phosphatases and kinases (York et al. 2001; Verbsky et al. 2002). The possibility that InsPs other than InsP3 act as intracellular signalling molecules has been suggested in several cell types. For instance, InsP5 and InsP6 concentrations may be modulated by various stimuli such as glucose in β-pancreatic cells (Larsson et al. 1997), depolarization in neurons (Sasakawa et al. 1993), abscisic acid in vegetable cells (Lemtiri-Chlieh et al. 2000) or AII in chromaffin cells (Sasakawa et al. 1990). Several specific inositol polyphosphate binding sites have been revealed in cell organelles such as c2b domain-containing protein and AP-2 protein; these binding sites are different from the InsP3 binding site (Theibert et al. 1992; Llinas et al. 1994; Rowley et al. 1996). InsP6 has been reported to be involved in the intracellular export of messenger RNA (York et al. 1999), proliferation of cells, stimulation of insulin secretion (Efanov et al. 1997) and regulation of ionic channels by various signalling pathways. In neurons, InsP6 stimulates L-type Ca2+ channels via the adenylyl cyclase pathway (Yang et al. 2001). On the other hand, in β-pancreatic cells, InsP6 stimulates L-type Ca2+ channels only via the ability of InsP6 to inhibit serine/threonine phosphatases (Larsson et al. 1997). InsP5 may mimic the effect of InsP6 (with a lower potency) or it may have a specific effect on neuronal ionic currents (Sawada et al. 1989). High levels of InsP5 and InsP6 have been reported in a smooth muscle cell line (Safrany & Shears, 1998). However, in portal vein smooth muscle cells, in which a PLC activity has been detected (Macrez et al. 1999), no information is available on a possible role of highly phosphorylated InsPs, alone or in combination, on voltage-gated Ca2+ channels.

In this study, we show that, InsP5 plus InsP6 stimulate L-type Ca2+ channels of vascular smooth muscle cells. As the production of InsP5 and InsP6 could be physiologically modulated, these InsPs may play a role in the stimulating effect of mediators on Ca2+ channels.

METHODS

The investigation conforms with the European Community and French guiding principles in the care and use of animals. Authorization to perform animal experiments was obtained from the French Ministère de l'Agriculture et de la Pêche

Cell preparation

Isolated myocytes from rat portal vein were obtained by enzymatic dispersion, as described previously (Morel et al. 1996). Wistar rats (150–160 g) were killed by cervical dislocation. The portal vein was cut into several pieces and incubated for 10 min in low Ca2+ (40 μm) physiological solution (mm: 130 NaCl, 5.6 KCl, 1 MgCl2, 10 Hepes, 11 glucose, pH 7.4) and then 0.8 mg ml−1 collagenase, 0.25 mg ml−1 pronase E and 1 mg ml−1 bovine serum albumin were added at 37 °C for 20 min. The solution was then removed, and the pieces of vein were incubated again in a fresh enzyme solution at 37 °C for 20 min. The tissues were then placed in an enzyme-free solution and triturated using a fire-polished Pasteur pipette to release cells. Cells were seeded at a density of about 103 cells mm−2 on glass slides in physiological solution and used within the next 24 h. A7R5 smooth muscle cells were cultivated as described by Seki et al. (1999). A7R5 cells were maintained under 5 % CO2 at 37 °C in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) with 10 % fetal bovine serum, 100 U ml−1 penicillin, 100 μg ml−1 streptomycin and 2 mm glutamine. After the cells were grown to confluence, they were trypsinized by treatment for 1 min with 0.05 % trypsin. After centrifugation to wash out the trypsin, cells were seeded on a Petri dish in culture medium. For electrophysiological recordings, cells were seeded at a density of about 103 cells mm−2 on glass slides in culture medium containing 1 % fetal bovine serum and then recorded within the next 24 h.

Electrophysiological recordings

Voltage-clamp and membrane current recordings were made with a standard patch-clamp technique using a List EPC-7 patch-clamp amplifier (Darmstadt-Eberstadt, Germany). Whole-cell recordings were performed with patch pipettes having resistances of 2–5 MΩ. Membrane potential and current records were stored and analysed using a PC (pCLAMP system, Axon Instruments, Union City, CA, USA). Capacitive transient and linear leakage currents were subtracted using a 4 subpulse protocol according to the pCLAMP setup. Cell capacitance was determined in each cell tested by imposing 10 mV hyperpolarizing and depolarizing steps from the holding potential (−50 mV) and analysing the amplitude and time course of capacitive current. The time constant of the current decay (τ, seconds) was estimated with a mono-exponential function according to the pCLAMP setup, and capacitance was calculated according to the function: capacitance (C, farads) = τ/R. The resistance (R, ohms) was estimated from the amplitude of the capacitive current. Current density was expressed as the maximum amplitude of the current (for a depolarizing step to 0 mV) per capacitance unit (pA pF−1). When cells were their own controls, results were expressed as a percentage of current stimulation. Kinetics of inactivation of the current (for a depolarizing step to 0 mV, holding potential of −50 mV) were calculated with a mono-exponential function (f(t) = Aexp(−t/τ) +C) according to pCLAMP setup. Steady-state inactivation experiments were performed with a double pulse protocol. A test pulse to +10 mV was preceded by a prepulse of 10 s duration and of variable amplitude (from −80 to 10 mV). Steady-state inactivation curves were fitted using a Boltzmann equation.

The extracellular solution contained (mm): 130 NaCl, 5.6 KCl, 1 MgCl2, 11 glucose, 10 Hepes, 5 BaCl2, pH 7.4 with NaOH. The basic pipette solution contained (mm): 130 CsCl, 10 EGTA, 5 ATPNa2, 2 MgCl2, BSA (0.1 %), 10 Hepes, pH 7.3 with CsOH. In some experiments, barium was replaced by 2 mm CaCl2 and the intracellular concentration of EGTA was reduced to 10 μm in the presence of 5 μm CaCl2 (free intracellular Ca2+ concentration around 50 nm). Ins(1,3,4,5,6)P5 (InsP5), InsP6 or a mixture of both (InsP5,6) were added to the pipette solution. The Ins(1,3,4,5,6)P5 isoform was chosen as this isoform was the precursor for InsP6. Phorbol 12,13-dibutyrate (PDBu) or forskolin was applied on the cells via pressure ejection from a glass pipette. Inhibitors of protein kinases A and C and of protein phosphatases were preincubated with the cells for at least 15 min before patch-clamp experiments. All experiments were performed at 30 ± 2 °C.

Chemicals

Phorbol 12,13-dibutyrate (PDBu) was from LC Laboratories (Woburn, MA, USA). H89 (N-(2-((bromocinnamyl)amino)ethyl)-5-isoquinolinesulfonamide), forskolin and Ro 32-0432 (2-(8-(dimethylamino)methyl)-6,7,8,9-tetrahydropyrido(1,2-a)indol-3-yl)-3-(1-methyl-1H-indol-3-yl)maleimide) were from Calbiochem (Meudon, France). GF109203X ((1-(3-dimethylaminopropyl)-indol-3-yl)-3-(indol-3-yl) maleimide) was a gift from Glaxo (Les Ulis, France). All other chemicals were purchased from Sigma (St Louis, MO, USA). H89, Ro 32-0432, GF109203X, calphostin, cypermethrin, okadaic acid, PDBu and forskolin were diluted from a stock solution in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO). The final concentration of DMSO was less than 1/10 000 (except for forskolin, 1/1000) and had no effect on Ca2+ channel current (Mironneau et al. 1991).

Statistics

All values are given as means ± s.e.m. Statistical analysis was performed using Student's t test and P values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

All experiments and measurements of membrane current were performed at least 5 min after the breakthrough into the whole-cell patch-clamp configuration to allow intracellular diffusion of the pipette solution and stabilization of the Ba2+ current. Ba2+ current densities and kinetics of inactivation were calculated for depolarizing steps to 0 mV from a holding potential of −50 mV. The mean capacitance of the cells was 19.10 ± 1.18 pF (n = 106).

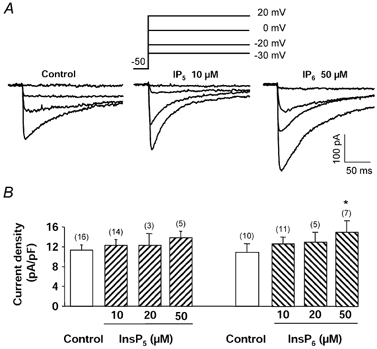

Intracellular application of 10, 20 or 50 μm InsP5 alone did not change the density of the basal Ba2+ current (Fig. 1A and B). Neither the kinetics of inactivation (time constant: 86.7 ± 4.9 ms, n = 12, in the presence of InsP5 compared with 91.5 ± 4.1 ms, n = 30, in control conditions) nor the time course of Ba2+ currents recorded for different depolarizing steps (Fig. 1A) were affected by intracellular application of 10 μm InsP5. In addition, the steady-state inactivation curves were superimposed (potential for half-inactivation: −31.3 ± 1.1 mV, n = 5, in the presence of InsP5 compared with −29.9 ± 0.7 mV, n = 6, in control conditions).

Figure 1. Effects of InsP5 and InsP6 on basal Ba2+ current in vascular myocytes.

A, typical Ba2+ currents recorded in control conditions and in the intracellular presence of 10 μm InsP5 or 50 μm InsP6 (depolarizing steps to −30, −20, 0 and 20 mV from a holding potential of −50 mV). B, Ba2+ current density measured with a control pipette solution and with a pipette solution containing different concentrations of InsP5 or InsP6. Holding potential −50 mV, depolarizing steps to 0 mV. Currents were recorded 5 min after the breakthrough into the whole-cell patch-clamp configuration. Data are means and s.e.m., with the number of experiments indicated in parentheses. * Significantly different from the value obtained in control conditions (P < 0.05).

In contrast, intracellular applications of InsP6 dose-dependently increased the current density, with a significant effect at 50 μm (Fig. 1A and B). In the intracellular presence of 10 and 50 μm InsP6, the kinetics of inactivation were 91.9 ± 5.2 ms (n = 12) and 93.1 ± 7.5 ms (n = 5), respectively; they were not altered compared with control conditions (91.5 ± 4.1 ms, n = 30). The time course of Ba2+ currents recorded for different depolarizing steps (Fig. 1A), and the steady-state inactivation curve (potential for half-inactivation: −33.4 ± 1.8 mV, n = 3, for 10 μm InsP6 and −32.1 ± 2.1 mV, n = 3, for 50 μm InsP6) were not statistically affected as compared with control conditions (−29.9 ± 0.7 mV, n = 6).

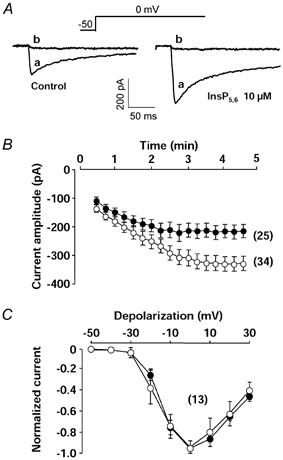

The efficiency of InsP5 and InsP6 on Ca2+ channel activity was then tested by adding both InsP5 and InsP6 (InsP5,6). Figure 2A illustrates the time course of Ba2+ currents evoked in the presence and absence of InsP5,6 after the breakthrough into the whole-cell recording mode. InsP5,6 (10 μm) induced a time-dependent increase of the Ba2+ current reaching a steady-state after 3 min of infusion (Fig. 2B). The stimulatory effect of intracellular InsP5,6 increased from 1 μm to 10 μm (Fig. 3C) whereas external application of 10 μm InsP5,6 was ineffective (n = 7). With 2 mm extracellular Ca2+ and a low intracellular Ca2+ buffering, the Ca2+ current density increased from 3.4 ± 0.4 pA pF−1 in control conditions to 4.4 ± 0.4 pA pF−1 in the intracellular presence of 10 μm InsP5,6. It is noteworthy that the variation of the Ba2+ current density was not linked to an increase of the leak current as the seal resistance (more than 1 GΩ) did not change during intracellular application of InsP5,6 (n = 12). Furthermore, both basal Ba2+ currents and InsP5,6-induced Ba2+ currents were totally inhibited by the Ca2+ channel antagonist oxodipine (1 μm) (Fig. 2A). In the presence of 10 μm InsP5,6, the kinetics of inactivation of the Ba2+ current (time constant: 95.9 ± 5.2 ms, n = 25, compared with 91.5 ± 4.1 ms, n = 30, in control conditions), the current-voltage relationships (Fig. 2C) and the normalized steady-state inactivation curves (half-inactivation potential: −28.5 ± 0.7 mV, n = 7, compared with −29.9 ± 0.7 mV, n = 6, in control conditions) were also not statistically altered.

Figure 2. Effects of InsP5,6 on basal Ba2+ current.

A, typical Ba2+ currents recorded in control conditions and in the intracellular presence of 10 μm InsP5 + 10 μm InsP6 (InsP5,6), before (a) or after (b) application of the calcium channel antagonist oxodipine (1 μm). B, time course of Ba2+ current amplitude in cells dialysed with a control pipette solution (•) or with a pipette solution containing 10 μm InsP5,6 (○). Zero time corresponds to the breakthrough into the whole-cell recording mode. Holding potential −50 mV, depolarizing steps to 0 mV. C, current–voltage relationships obtained from a holding potential of −50 mV in cells dialysed with a control pipette solution (•) or a pipette solution containing 10 μm InsP5,6 (○). Curves were normalized to −1 for step depolarizations to 0 mV. Currents were recorded 5 min after the breakthrough into the whole-cell patch-clamp configuration. Data are means ± s.e.m., with the number of experiments indicated in parentheses.

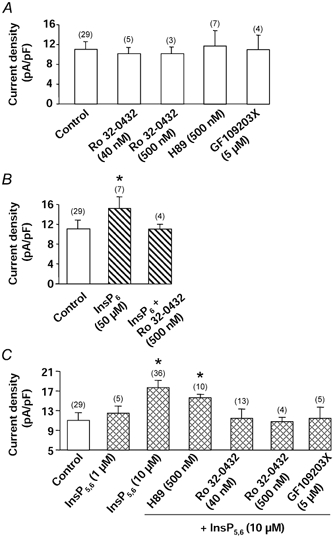

Figure 3. Effects of protein kinase inhibitors on InsP-modulated Ba2+ current.

A, effects of PKC inhibitors (Ro 32-0432 and GF109203X) and PKA inhibitor (H89) on basal Ba2+ current density. Cells were dialysed with a control pipette solution. B, effects of PKC inhibitor (Ro 32-0432) on InsP6-mediated stimulation of Ba2+ current density. Cells were dialysed with a pipette solution containing 50 μm InsP6. C, effects of PKC inhibitors (Ro 32-0432 and GF109203X) and PKA inhibitor (H89) on InsP5,6-mediated stimulation of Ba2+ current density. Cells were dialysed with a pipette solution containing 10 μm InsP5+ 10 μm InsP6. Holding potential −50 mV, depolarizing steps to 0 mV. Current density was measured 5 min after the breakthrough into the whole-cell patch-clamp configuration. Cells were incubated in the presence of inhibitors at least 15 min prior to the recording. Data are means and s.e.m., with the number of experiments indicated in parentheses. * Values significantly different from those obtained in control conditions (P < 0.05).

The mechanisms responsible for the stimulatory effect of InsP6 and InsP5,6 were then investigated. As InsPs could modulate PKA or PKC activity, inhibitors of these kinases were tested. As described previously, Ba2+ currents of vascular myocytes were stimulated by at least two different pathways, i.e. a PKA pathway (Viard et al. 2001) and a PKC pathway (Macrez-Leprêtre et al. 1996). Neither the PKA inhibitor H89 (500 nm, Chijiwa et al. 1990) nor the PKC inhibitors Ro 32-0432 (40 nm or 500 nm, Wilkinson et al. 1993) and GF109203X (Toullec et al. 1991) at 5 μm significantly altered the basal current density (Fig. 3A). Stimulations of Ba2+ current by 5 μm forskolin or 100 nm PDBu were inhibited by H89 (500 nm) or Ro 32-0432 (500 nm), respectively (Fig. 4A and B). In the presence of H89 (Fig. 3C), the InsP5,6-induced stimulation of the Ba2+ current was not statistically altered. However, in the presence of 40 or 500 nm Ro 32-0432, or 5 μm GF109203X, the Ba2+ current density measured in the presence of 10 μm InsP5,6 was reduced to the control level (Fig. 3C). In the presence of a different type of PKC inhibitor, calphostin C (100 nm, activated by UV illumination, Kobayashi et al. 1989), the InsP5,6-induced stimulation of the Ba2+ currents was also abolished (n = 8). Similar results were obtained in the presence of 50 μm InsP6. As illustrated in Fig. 3B, the InsP6-induced stimulation of the Ba2+ current density was suppressed in the presence of 500 nm Ro 32-0432.

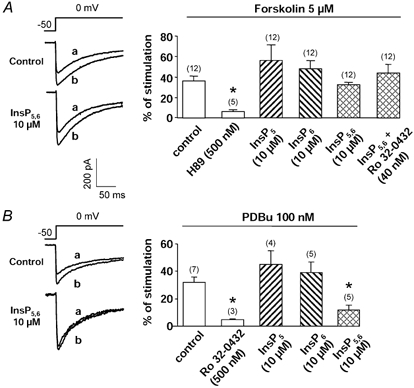

Figure 4. Effects of protein kinase stimulators and InsPs on Ba2+ current.

A, typical current traces before (a) and after (b) external application of forskolin (5 μm) in control conditions and in the internal presence of InsP5,6 (10 μm InsP5 + 10 μm InsP6). Right panel, percentage of stimulation of the Ba2+ current induced by the adenylyl cyclase activator forskolin in cells infused with a control pipette solution or solutions containing 10 μm InsP5, InsP6 or InsP5,6 (alone or in the presence of Ro 32-0432). B, typical current traces before (a) and after (b) external application of PDBu (100 nm) in control conditions and in the internal presence of InsP5,6. Right panel, percentage of stimulation of the Ba2+ current induced by the PKC stimulator PDBu in cells infused with a control pipette solution or solutions containing 10 μm InsP5, InsP6 or InsP5,6. Note that the amplitudes of the current before application of the stimulating substances were quite different (see Figs 1 and 2). Holding potential −50 mV, depolarizing steps to 0 mV. Current density was measured 5 min after the breakthrough into the whole-cell patch-clamp configuration. Data are means and s.e.m., with the number of experiments indicated in parentheses. * Significantly different from values obtained in control conditions (P < 0.05).

The cumulative effects of InsP5, InsP6 and InsP5,6 on the PKA/PKC signalling pathways were then tested by using forskolin and PDBu. Forskolin (5 μm) stimulated the peak Ba2+ current in control conditions (Fig. 4A). The drug was externally applied 5 min after the rupture of the patch and the maximum stimulatory effect was obtained 1–3 min after the beginning of the application. In the intracellular presence of InsP5, InsP6 or InsP5,6 (10 μm each), forskolin was still able to increase the Ba2+ current amplitude (Fig. 4A). It could be noted that Ro 32-0432 did not alter the forskolin-induced response in these conditions (Fig. 4A). Intracellular infusion of InsP5 or InsP6 (10 μm) did not affect or slightly increased the PDBu-mediated stimulation of the Ba2+ currents (Fig. 4B). In contrast, the stimulation of the Ba2+ current by PDBu was statistically reduced in the presence of InsP5,6 as compared with control conditions (Fig. 4B).

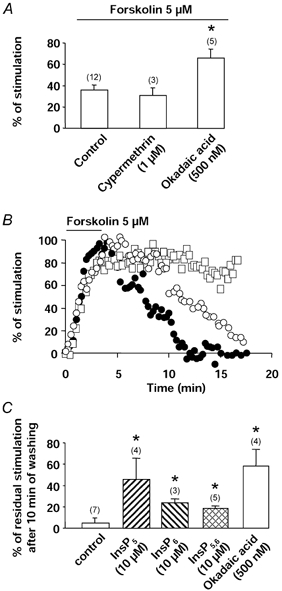

Phosphatase activity can also be modulated by InsPs. As shown in Fig. 5A, okadaic acid (inhibitor of phosphatase (PPase) 1, PPase 2A and PPase 3 at a concentration of 500 nm, Cohen, 1989) or cypermethrin (1 μm; inhibitor of PPase 2B, Enan & Matsumura, 1992) (alone or together) did not stimulate the basal Ba2+ current density and so did not mimic the effect of InsP6 or InsP5,6. Furthermore, okadaic acid or okadaic acid plus cypermethrin did not reduce the InsP5,6-stimulated current density (Fig. 5B). However, InsPs could mimic some effects of the phosphatase inhibitors on Ca2+ channels. Cypermethrin did not alter the forskolin-mediated stimulation of the current (Fig. 6A) whereas in the presence of okadaic acid, the stimulation of the current was larger than in control conditions (Fig. 6A), indicating that phosphatase activity was present when the channel was previously phosphorylated. Furthermore, okadaic acid modified the time course of the effect of forskolin. In control conditions, stimulation of the Ba2+ current by forskolin (5 μm) was maximal within 3–4 min. After withdrawal of forskolin, the current returned to its control value within 10–14 min (Fig. 6B). In the presence of okadaic acid, the forskolin-induced increase in Ba2+ current persisted after washout of forskolin, even after 15 min (Fig. 6B and C). In the presence of InsP5, InsP6 or InsP5,6, the time courses of recovery of the Ba2+ current were slowed down (Fig. 6B and C) and the effect of forskolin was still present after 10 min of washout. In comparison, effects of InsP5,6 were tested in the vascular smooth muscle cell line A7R5. Infusion of InsP5,6 (10 μm) did not change the current density (control: 3.3 ± 0.4 pA pF−1, n = 9; in the presence of InsP5,6: 3.5 ± 0.7 pA pF−1, n = 6), and furthermore PDBu was unable to stimulate the Ba2+ current (−4.9 ± 0.2 %, n = 5).

Figure 5. Effects of phosphatase inhibitors on Ba2+ current density.

A, effects of PPases 1, 2A and 3 inhibitor okadaic acid and PPase 2B inhibitor cypermethrin on basal Ba2+ current density. Cells were dialysed with a control pipette solution. B, effects of the same inhibitors on the InsP5,6-mediated stimulation of the Ba2+ current density. Cells were dialysed with a solution containing 10 μm InsP5,6. Holding potential −50 mV, depolarizing steps to 0 mV. Current density was measured 5 min after the breakthrough into the whole-cell patch-clamp configuration. Cells were incubated in the presence of inhibitors at least 15 min prior to the recording. Data are means and s.e.m., with the number of experiments indicated in parentheses.

Figure 6. Effects of okadaic acid and InsPs on the time course of forskolin-mediated stimulation of Ba2+ current.

A, percentage of stimulation of the Ba2+ current induced by the adenylyl cyclase activator forskolin in the presence of the protein phosphatase inhibitors okadaic acid and cypermethrin. Cells were dialysed with a control pipette solution. B, typical time course of normalized Ba2+ current amplitude in cells dialysed with a control pipette solution (•), in the external presence of okadaic acid (□) or with a pipette solution containing 10 μm InsP5,6 (○). Forskolin (5 μm) was applied as indicated by the horizontal bar. C, percentage of residual stimulation of the Ba2+ current after 10 min of forskolin washing out in control conditions or in the presence of extracellular okadaic acid (in these two conditions, cells were dialysed with a control pipette solution) or in the intracellular presence of InsP5, InsP6 or InsP5,6. Maximal current after application of forskolin was normalized to 100. Holding potential −50 mV, depolarizing steps to 0 mV. Current density was measured 5 min after the breakthrough into the whole-cell patch-clamp configuration. Data are means and s.e.m., with the number of experiments indicated in parentheses. * Values significantly different from those obtained in control conditions (P < 0.05).

DISCUSSION

Our results illustrate a novel pathway of modulation of vascular L-type voltage-gated Ca2+ channels, in which InsPs (mainly Ins(1,3,4,5,6)P5 and InsP6) play a crucial role in the activation of these channels. These molecules are not simple catabolites of phosphoinosides but appear as intracellular messengers. We show here for the first time that InsPs can stimulate vascular L-type Ca2+ channels via a PKC activation pathway.

The increase of inward current amplitude by InsP6 or InsP5,6 was specifically linked to a stimulation of L-type Ca2+ channels. The InsP-induced current had the characteristics of the L-type current (similar potentials for threshold, maximum amplitude and half-inactivation, similar kinetics of inactivation and sensitivity to oxodipine). Furthermore, no specific leak current induced by InsPs was observed. These results are in contrast with the observation that prolactin promotes Ca2+ entry through voltage-independent Ca2+ channels that may be activated by Ins(1,3,4,5)P4 and InsP6 (Ratovondrahona et al. 1998). Participation of T-type Ca2+ currents, which are present in these cells (Morel et al. 1997), could be also ruled out since T-type Ca2+ current was largely inactivated at a holding potential of −50 mV. Similarly, InsP6 has not been reported to stimulate T-type Ca2+ channels in neurons (Yang et al. 2001).

There are multiple targets for InsPs in cells. Firstly, non-specific interactions of InsPs with the membrane due to the charge of the molecule (Shears, 2001) could be ruled out since application of 10 or 20 μm of each InsP had no effect, whereas 10 μm InsP5,6 induced a stimulation of the Ca2+ channels. Secondly, InsPs could chelate Ca2+ ions (Luttrell, 1993), and it is well known that the free intracellular Ca2+ level may modulate Ca2+ current (Neveu et al. 1993). In vascular myocytes, this hypothesis could be discarded since most of the results were obtained with an intracellular solution containing 10 mm EGTA and a Ca2+-free, Ba2+-containing extracellular solution. However, in more physiological conditions (i.e. 2 mm extracellular Ca2+ and low intracellular Ca2+ buffering), the InsP-mediated stimulation of Ca2+ channels was still observed indicating that Ca2+ ions did not act as an inhibitor of this regulation. Thirdly, a direct action of InsP5,6 on Ca2+ channels is certainly unlikely as binding sites of InsP6 and InsP5 have not been observed in Ca2+ channels (Theibert et al. 1992; Norris et al. 1995).

Activation of PKA by β-adrenergic receptors is known to stimulate L-type Ca2+ channels in rat portal vein myocytes. However, the PKA inhibitor H89, which inhibited both PKA- and forskolin-mediated stimulation of the Ba2+ current (Viard et al. 2001 and the present study), was unable to inhibit the InsP5,6-mediated activation of the current. Furthermore, InsPs did not alter the adenylyl cyclase/PKA pathway since the effects of InsP5, InsP6 or InsP5,6 were cumulative with the forskolin-induced stimulation of L-type Ca2+ channels. The lack of effect of H89 contrasts with previous observations which have shown that 10 μm InsP6 may stimulate adenylyl cyclase and L-type Ca2+ channels in hippocampal neurons (Yang et al. 2001). However, even if there is an increase in cAMP production in vascular myocytes, this increase is probably not sufficient or not localized near the PKA isoform associated with Ca2+ channels (Johnson et al. 1994).

InsP6 has been previously shown to stimulate PKC (Efanov et al. 1997; Hoy et al. 2002). We observed that PKC inhibitors significantly reduced the InsP5,6- and InsP6-induced stimulation of Ca2+ channels. Three different types of PKC inhibitors (Ro 32-0432, GF109203X and calphostin) revealed similar inhibitory effects. In the presence of InsP5,6, PDBu-induced stimulation of Ba2+ current was strongly reduced, as expected if PKC was previously stimulated by InsP5,6. Finally, in A7R5 smooth muscle cells, where PDBu is ineffective on L-type Ca2+ channels (Obejero-Paz et al. 1998), InsP5,6 had no effect. Ro 32-0432 may be considered to be a specific inhibitor of PKC, as this drug did not inhibit basal current density, but it inhibited PDBu-induced stimulation of the current and it did not alter forskolin-induced stimulation of the Ca2+ channel. The effect of Ro 32-0432 was observed for a low concentration (40 nm) suggesting that the PKC involved should be a classical PKC. At 40 nm, Ro 32-0432, which binds to PKC at the ATP binding site, totally inhibits the PKCα isoform (IC50: 9 nm) and partially the PKCβ1, β2 and γ isoforms (IC50 between 28 and 37 nm, Wilkinson et al. 1993). At 500 nm, Ro 32-0432 also inhibits the PKCε isoform but does not affect other serine/threonine kinases such as PKA (present study). The involvement of PKC in the InsP-mediated effect is confirmed by calphostin C, which at a concentration of 100 nm inhibits both classical and novel PKC isoforms by competing at the binding site of 1,2-diacylglycerol (DAG; Kobayashi et al. 1989; Rotenberg et al. 1995). A concentration of 5 μm GF109203X was required to inhibit the InsP-mediated effect. At this concentration, the PKC α, β, δ, ε, ζ isoforms but also other serine/threonine kinases such as PKA could be inhibited (Toullec et al. 1991; Martiny-Baron et al. 1993). At 0.1 μm, GF109203X, which has been reported to inhibit the PKCα and β1 isoforms (Martiny-Baron et al. 1993), had no effect on the InsP5,6-mediated stimulation of the Ca2+ channels (unpublished data) suggesting that these PKC isoforms were not involved in the InsP-mediated stimulation of the current. This result contrasts with the stimulation of L-type Ca2+ channels by AII which is GF109203X (100 nm) sensitive (Macrez-Leprêtre et al. 1996). Although stimulation of PKC by 10 μm InsP6 has been reported in other tissues (Efanov et al. 1997; Hoy et al. 2002), 50 μm InsP6 alone or simultaneous application of 10 μm InsP5 + 10 μm InsP6 was required to stimulate Ca2+ channels in vascular myocytes. It is unlikely that transformation of 10 μm InsP5 into InsP6 or 10 μm InsP6 into InsP5 could explain these effects since 20 μm InsP6 or InsP5 alone did not show any stimulatory effects on Ca2+ channel activity. It can be postulated that the increased efficiency of InsP6 in the presence of InsP5 should be linked to the modulation of another target by InsP5. Indeed, phosphorylation of Ca2+ channels by PKC could be enhanced by the inhibition of serine/threonine phosphatase (Herzig & Neumann, 2000) since InsPs have been reported to act as serine/threonine phosphatase inhibitors (Barker & Berggren, 1999). However, in vascular myocytes, inhibitors of protein phosphatases (i.e. okadaic acid, 500 nm, inhibitor of PPases 1, 2A and 3, and cypermethrin, 1 μm, inhibitor of PPase 2B (Cohen, 1989) had no effect on basal Ca2+ channel activity, as also reported by Viard et al. (2001). These results are in contrast with the modulating effects of PPase 1 or PPase 2B inhibitors on Ca2+ channels in other smooth muscle cells (Obara & Yabu, 1993; Schuhmann et al. 1997), or with the powerful effects of okadaic acid on Ca2+ channels in β-pancreatic cells (Efanov et al. 1997). Although phosphatase activity did not regulate basal Ca2+ channel activity in vascular myocytes, okadaic acid enhanced and extended the forskolin-induced stimulation of Ba2+ current, as described by Perez-Reyes et al. (1994). The InsP5,6-induced increase of the Ba2+ current was only slightly reduced in the presence of inhibitors of protein phosphatases, indicating that the current stimulation was mainly due to an activation of PKC. However, the inhibitory effects of InsPs on protein phosphatases were present. InsPs significantly extended the effect of forskolin after washing out and so mimicked the effects of okadaic acid. Then, InsPs could prolong the stimulating effects of physiological agonists on L-type Ca2+ channels. In rat portal vein, AII induces long-lasting contractions which are inhibited by Ca2+ channel antagonists (Pelet et al. 1995). Activation of contraction is linked to AII-induced stimulation of vascular L-type Ca2+ channels via a PI3K and PKC and release of Ca2+ from the intracellular store by opening of ryanodine-sensitive Ca2+ channels (rapid pathway; Macrez et al. 1997; Viard et al. 1999). By stimulating a delayed production of InsP5 and InsP6 (L. Rakotoarisoa, personal communication), AII may maintain Ca2+ channel activity, and this stimulatory effect may account for the prolongation of contraction (slow pathway). Another effect of InsPs could be to extend the effects of physiological agents which stimulate the PKA pathway via inhibition of phosphatases.

In conclusion, the present data indicate that, in vascular smooth muscle cells of rat portal vein, intracellular infusion of InsP6 or InsP5 plus InsP6 produces a stimulation of the L-type Ca2+ channel via a PKC-dependent pathway.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from the Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique, the Centre National des Etudes Spatiales and the Association Française contre les Myopathies, France. We thank N. Biendon for secretarial assistance.

References

- Barker CJ, Berggren PO. Inositol hexakisphosphate and beta-cell stimulus-secretion coupling. Anticancer Res. 1999;19:3737–3741. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chijiwa T, Mishima A, Hagiwara M, Sano M, Hayashi K, Inoue T, Naito K, Toshioka T, Hidaka H. Inhibition of forskolin-induced neurite outgrowth and protein phosphorylation by a newly synthesized selective inhibitor of cyclic AMP-dependent protein kinase, N-(2-(p-bromocinnamylamino)ethyl)-5-isoquinolinesulfonamide (H-89), of PC12D pheochromocytoma cells. J Biol Chem. 1990;265:5267–5272. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen P. The structure and regulation of protein phosphatases. Annu Rev Biochem. 1989;58:453–508. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.58.070189.002321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Efanov AM, Zaitsev SV, Berggren PO. Inositol hexakisphosphate stimulates non-Ca2+-mediated and primes Ca2+-mediated exocytosis of insulin by activation of protein kinase C. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94:4435–4439. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.9.4435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enan E, Matsumura F. Specific inhibition of calcineurin by type II synthetic pyrethroid insecticides. Biochem Pharmacol. 1992;43:1777–1784. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(92)90710-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herzig S, Neumann J. Effects of serine/threonine protein phosphatases on ion channels in excitable membranes. Physiol Rev. 2000;80:173–210. doi: 10.1152/physrev.2000.80.1.173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoy M, Efanov AM, Bertorello AM, Zaitsev SV, Olsen HL, Bokvist K, Leibiger B, Leibiger IB, Zwiller J, Berggren PO, Gromada J. Inositol hexakisphosphate promotes dynamin I-mediated endocytosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:6773–6777. doi: 10.1073/pnas.102157499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson BD, Scheuer T, Catterall WA. Voltage-dependent potentiation of L-type Ca2+ channels in skeletal muscle cells requires anchored cAMP-dependent protein kinase. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1994;91:11492–11496. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.24.11492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keef KD, Hume JR, Zhong J. Regulation of cardiac and smooth muscle Ca2+ channels (Ca(V)1. 2a, b) by protein kinases. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2001;281:C1743–1756. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.2001.281.6.C1743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kobayashi E, Nakano H, Morimoto M, Tamaoki T. Calphostin C (UCN-1028C), a novel microbial compound, is a highly potent and specific inhibitor of protein kinase C. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1989;159:548–553. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(89)90028-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larsson O, Barker CJ, Sjöholm A, Carlqvist H, Michell RH, Bertorello A, Nilsson T, Honkanen RE, Mayr GW, Zwiller J, Berggren PO. Inhibition of phosphatases and increased Ca2+ channel activity by inositol hexakisphosphate. Science. 1997;278:471–474. doi: 10.1126/science.278.5337.471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lemtiri-Chlieh F, MacRobbie EA, Brearley CA. Inositol hexakisphosphate is a physiological signal regulating the K+-inward rectifying conductance in guard cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:8687–8692. doi: 10.1073/pnas.140217497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Llinas R, Sugimori M, Lang EJ, Morita M, Fukuda M, Niinobe M, Mikoshiba K. The inositol high-polyphosphate series blocks synaptic transmission by preventing vesicular fusion: a squid giant synapse study. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1994;91:12990–12993. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.26.12990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luttrell BM. The biological relevance of the binding of calcium ions by inositol phosphates. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:1521–1524. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macrez N, Morel JL, Kalkbrenner F, Viard P, Schultz G, Mironneau J. A βγ dimer derived from G13 transduces the angiotensin AT1 receptor signal to stimulation of Ca2+ channels in rat portal vein myocytes. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:23180–23185. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.37.23180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macrez N, Morel JL, Mironneau J. Specific G α11β3γ5 protein involvement in endothelin receptor-induced phosphatidylinositol hydrolysis and Ca2+ release in rat portal vein myocytes. Mol Pharmacol. 1999;55:684–692. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macrez-Leprêtre N, Morel JL, Mironneau J. Angiotensin II-mediated activation of L-type Ca2+ channels involves phosphatidylinositol hydrolysis-independent activation of protein kinase C in rat portal vein myocytes. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1996;278:468–475. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martiny-Baron G, Kazanietz MG, Mischak H, Blumberg PM, Kochs G, Hug H, Marme D, Schachtele C. Selective inhibition of protein kinase C isozymes by the indolocarbazole Go 6976. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:9194–9197. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mironneau J, Arnaudeau S, Mironneau C. Fenoverine inhibition of calcium channel currents in single smooth muscle cells from rat portal vein and myometrium. Br J Pharmacol. 1991;104:65–70. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1991.tb12386.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morel JL, Drobecq H, Sautiere P, Tartar A, Mironneau J, Qar J, Lavie JL, Hugues M. Purification of a new dimeric protein from Cliona vastifica sponge, which specifically blocks a non-L-type Ca2+ channel in mouse duodenal myocytes. Mol Pharmacol. 1997;51:1042–1052. doi: 10.1124/mol.51.6.1042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morel JL, Macrez-Leprêtre N, Mironneau J. Angiotensin II-activated Ca2+ entry-induced release of Ca2+ from intracellular stores in rat portal vein myocytes. Br J Pharmacol. 1996;118:73–78. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1996.tb15368.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neveu D, Nargeot J, Richard S. Two high-voltage-activated, dihydropyridine-sensitive Ca2+ channel currents with distinct electrophysiological and pharmacological properties in cultured rat aortic myocytes. Pflugers Arch. 1993;424:45–53. doi: 10.1007/BF00375101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norris FA, Ungewickell E, Majerus PW. Inositol hexakisphosphate binds to clathrin assembly protein 3 (AP-3/AP180) and inhibits clathrin cage assembly in vitro. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:214–217. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.1.214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Obara K, Yabu H. Dual effect of phosphatase inhibitors on calcium channels in intestinal smooth muscle cells. Am J Physiol. 1993;264:C296–301. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1993.264.2.C296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Obejero-Paz CA, Auslender M, Scarpa A. PKC activity modulates availability and long openings of L-type Ca2+ channels in A7r5 cells. Am J Physiol. 1998;275:C535–543. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1998.275.2.C535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pelet C, Mironneau C, Rakotoarisoa L, Neuilly G. Angiotensin II receptor subtypes and contractile responses in portal vein smooth muscle. Eur J Pharmacol. 1995;279:15–24. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(95)00125-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perez-Reyes E, Yuan W, Wei X, Bers DM. Regulation of the cloned L-type cardiac Ca2+ channel by cyclic-AMP-dependent protein kinase. FEBS Lett. 1994;342:119–123. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(94)80484-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quignard JF, Mironneau J, Carricaburu V, Fournier B, Babich A, Nurnberg B, Mironneau C, Macrez N. Phosphoinositide 3-kinase γ mediates angiotensin II-induced stimulation of L-type Ca2+ channels in vascular myocytes. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:32545–32551. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M102582200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ratovondrahona D, Fahmi M, Fournier B, Odessa MF, Skryma R, Prevarskaya N, Djiane J, Dufy B. Prolactin induces an inward current through voltage-independent Ca2+ channels in Chinese hamster ovary cells stably expressing prolactin receptor. J Mol Endocrinol. 1998;21:85–95. doi: 10.1677/jme.0.0210085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rotenberg SA, Huang MH, Zhu J, Su L, Riedel H. Deletion analysis of protein kinase C inactivation by calphostin C. Mol Carcinog. 1995;12:42–49. doi: 10.1002/mc.2940120107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rowley KG, Gundlach AL, Cincotta M, Louis WJ. Inositol hexakisphosphate binding sites in rat heart and brain. Br J Pharmacol. 1996;118:1615–1620. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1996.tb15582.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Safrany ST, Shears SB. Turnover of bis-diphosphoinositol tetrakisphosphate in a smooth muscle cell line is regulated by β2-adrenergic receptors through a cAMP-mediated, A-kinase-independent mechanism. EMBO J. 1998;17:1710–1716. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.6.1710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sasakawa N, Nakaki T, Kakinuma E, Kato R. Increase in inositol tris-, pentakis- and hexakisphosphates by high K+ stimulation in cultured rat cerebellar granule cells. Brain Res. 1993;623:155–160. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(93)90023-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sasakawa N, Nakaki T, Kato R. Stimulus-responsive and rapid formation of inositol pentakisphosphate in cultured adrenal chromaffin cells. J Biol Chem. 1990;265:17700–17705. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sawada M, Ichinose M, Maeno T. Intracellularly injected inositol 1,3,4,5,6-pentakisphosphate induces a slow inward current in identified neurons of Aplysia kurodai. Brain Res. 1989;503:167–169. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(89)91721-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuhmann K, Romanin C, Baumgartner W, Groschner K. Intracellular Ca2+ inhibits smooth muscle L-type Ca2+ channels by activation of protein phosphatase type 2B and by direct interaction with the channel. J Gen Physiol. 1997;110:503–513. doi: 10.1085/jgp.110.5.503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seki T, Yokoshiki H, Sunagawa M, Nakamura M, Sperelakis N. Angiotensin II stimulation of Ca2+-channel current in vascular smooth muscle cells is inhibited by lavendustin-A and LY-294002. Pflugers Arch. 1999;437:317–323. doi: 10.1007/s004240050785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shears SB. Assessing the omnipotence of inositol hexakisphosphate. Cell Signal. 2001;13:151–158. doi: 10.1016/s0898-6568(01)00129-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Theibert AB, Estevez VA, Mourey RJ, Marecek JF, Barrow RK, Prestwich GD, Snyder SH. Photoaffinity labeling and characterization of isolated inositol 1,3,4,5-tetrakisphosphate- and inositol hexakisphosphate-binding proteins. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:9071–9079. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toullec D, Pianetti P, Coste H, Bellevergue P, Grand-Perret T, Ajakane M, Baudet V, Boissin P, Boursier E, Loriolle F, Duhamel L, Charon D, Krilovsky J. The bisindolylmaleimide GF 109203X is a potent and selective inhibitor of protein kinase C. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:15771–15781. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Touyz RM, Schiffrin EL. Signal transduction mechanisms mediating the physiological and pathophysiological actions of angiotensin II in vascular smooth muscle cells. Pharmacol Rev. 2000;52:639–672. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verbsky JW, Wilson MP, Kisseleva MV, Majerus PW, Wente SR. The synthesis of inositol hexakisphosphate. Characterization of human inositol 1, 3,4,5,6-pentakisphosphate 2-kinase. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:31857–31862. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M205682200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Viard P, Exner T, Maier U, Mironneau J, Nurnberg B, Macrez N. Gβγ dimers stimulate vascular L-type Ca2+ channels via phosphoinositide 3-kinase. FASEB J. 1999;13:685–694. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.13.6.685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Viard P, Macrez N, Mironneau C, Mironneau J. Involvement of both G protein αs and βγ subunits in β-adrenergic stimulation of vascular L-type Ca2+ channels. Br J Pharmacol. 2001;132:669–676. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0703864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilkinson SE, Parker PJ, Nixon JS. Isoenzyme specificity of bisindolylmaleimides, selective inhibitors of protein kinase C. Biochem J. 1993;294:335–337. doi: 10.1042/bj2940335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang SN, Yu J, Mayr GW, Hofmann F, Larsson O, Berggren PO. Inositol hexakisphosphate increases L-type Ca2+ channel activity by stimulation of adenylyl cyclase. FASEB J. 2001;15:1753–1763. doi: 10.1096/fj.00-0799com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- York JD, Guo S, Odom AR, Spiegelberg BD, Stolz LE. An expanded view of inositol signaling. Adv Enzyme Regul. 2001;41:57–71. doi: 10.1016/s0065-2571(00)00025-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- York JD, Odom AR, Murphy R, Ives EB, Wente SR. A phospholipase C-dependent inositol polyphosphate kinase pathway required for efficient messenger RNA export. Science. 1999;285:96–100. doi: 10.1126/science.285.5424.96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]