Abstract

4-Aminopyridine (4-AP) has been used extensively to study transient outward K+ current (ITO,1) in cardiac cells and tissues. We report here inhibition by 4-AP of HERG (the human ether-à-go-go-related gene) K+ channels expressed in a mammalian cell line, at concentrations relevant to those used to study ITO,1. Under voltage clamp, whole cell HERG current (IHERG) tails following commands to +30 mV were blocked with an IC50 of 4.4 ± 0.5 mm. Development of block was contingent upon HERG channel gating, with a preference for activated over inactivated channels. Treatment with 5 mm 4-AP inhibited peak IHERG during an applied action potential clamp waveform by ∼59 %. It also significantly prolonged action potentials and inhibited resurgent IK tails from guinea-pig isolated ventricular myocytes, which lack an ITO,1. We conclude that by blocking the α-subunit of the IKr channel, millimolar concentrations of 4-AP can modulate ventricular repolarisation independently of any action on ITO,1.

4-Aminopyridine (4-AP) has been used extensively in cardiac electrophysiology to study the physiological roles of transient outward potassium current (ITO,1; Wang et al. 1991; Gillis et al. 1998; Elizalde et al. 1999; Lei et al. 2000; Kocic et al. 2002) and, in recent years, of the ‘ultra-rapid’ delayed rectifier current (IKur; Li et al. 1996; Yue et al. 1996). 4-AP is generally considered selective for these currents in the heart, with micromolar concentrations being used to block IKur (Li et al. 1996) and millimolar concentrations to block ITO,1 (typically 0.5 to 10 mm; e.g. Wang et al. 1991; Gillis et al. 1998; Elizalde et al. 1999; Lei et al. 2000; Kocic et al. 2002). However, limited published data raise the possibility that 4-AP may not be entirely selective for ITO,1 over the rapid delayed rectifier K+ current (IKr) at concentrations used to study ITO,1 (Mitcheson & Hancox, 1999; Liu et al. 1999; Zhang et al. 2000). Given the importance of IKr in regulating action potential repolarization and duration (Mitcheson & Sanguinetti, 1999), a non-selective effect of 4-AP on IKr would significantly influence the interpretation of data from experiments in which 4-AP is applied to cardiac muscle cells or tissues. The aim of this study was to determine whether or not 4-AP inhibits ionic current (IHERG) carried by K+ channels encoded by HERG (the human ether-à-go-go-related gene, which encodes the α-subunit of the IKr channel; Warmke & Ganetzky, 1994). 4-AP was found both to inhibit IHERG recorded from human embryonic kidney cells and to prolong action potentials from guinea-pig ventricular myocytes, which lack ITO,1. These findings have widespread implications for the use of 4-AP as an investigative tool in cardiac muscle electrophysiology.

METHODS

Maintenance of a mammalian cell line stably expressing HERG

Measurements of IHERG were made from human embryonic kidney (HEK 293) cells stably expressing HERG (cell line generously donated by Professor Craig January, University of Wisconsin; Zhou et al. 1998). Cells were passaged using a non-enzymatic agent (Splittix, AutogenBioclear) and plated out onto fragments of sterilized glass coverslips in 30 mm petri dishes containing a modification of Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium with Glutamax-1 (DMEM; Gibco), supplemented with 10 % fetal bovine serum, 400 μg ml−1 gentamicin (Gibco) and 400 μg ml−1 geneticin (G418; Gibco). Cells were incubated at 37 °C (5 % CO2) for a minimum of 2 days prior to any electrophysiological study.

Isolation of guinea-pig ventricular myocytes

Male adult guinea-pigs were killed by cervical dislocation (a Schedule 1 procedure according to the Home Office UK Animals (Scientific Procedures) Act 1986) and ventricular myocytes were enzymatically dispersed from both ventricles using a method described previously (Levi & Issberner, 1996). Prior to use, the isolated cells were kept at 4 °C in Kraft-Brühe medium (Isenberg & Klockner, 1982).

Electrophysiological recordings

Cells were superfused with a normal Tyrode solution, which contained (mm): 140 NaCl, 4 KCl, 2.5 CaCl2, 1 MgCl2, 10 glucose, 5 Hepes, (titrated to pH 7.45 with NaOH). Experimental solutions were applied using a home-built, warmed solution delivery system capable of changing the bathing solution surrounding a cell in <1 s. Patch-pipettes were fire-polished to a resistance of 3.5–5 MΩ. The pipette solution for IHERG measurement contained (mm): 130 KCl, 1 MgCl2, 5 EGTA, 5 MgATP, 10 Hepes (titrated to pH of 7.2 with KOH). A K+-based, EGTA-free pipette solution containing 10 mm NaCl was used for action potential recordings. The ‘pipette-to-bath’ liquid junction potential was small (−3.2 mV) and was uncorrected. Series resistance (Rs) values lay typically between 4–7 MΩ and were compensated by ≥ 70 %. The expected voltage drop across residual uncompensated Rs during IHERG measurements was therefore only small (∼3.5 mV or less) and no correction was made for this. Measurements were made at 37 ± 1 °C.

Drugs

4-AP powder (Sigma) was dissolved directly in normal Tyrode solution to make test solutions of different concentrations referred to in the Results; pH was corrected to 7.45 with HCl.

Voltage protocols and analysis

Measurements were made using an Axopatch 200 or 200A amplifier (Axon Instruments) and a CV-201/2A headstage. Voltage-clamp commands were generated using ‘WinWCP’ (John Dempster, Strathclyde University, UK) or pCLAMP (v 6.0, Axon Instruments). Data were recorded via a Digidata interface (Axon Instruments) and stored on the hard disk of a personal computer.

Concentration–response relationships

IHERG tails were measured on repolarization to −40 mV after 1 s depolarizing voltage commands to +30 mV. 4-AP concentrations between 100 μm and 100 mm were each applied to a minimum of five different cells. The mean fractional blockade was obtained as:

| (1) |

where IHERG(4AP) and IHERG(CONTROL) represent tail current amplitudes in the presence and absence of 4-AP, respectively. The agent was rapidly acting (maximal effects of a given concentration typically being observed within ∼2–4 pulses), and its effects could be observed without any marked overlying current run-down. Concentration-response data were fitted by the equation:

|

(2) |

where IC50 is [4-AP] producing half-maximal inhibition of the IHERG tail and h is the Hill coefficient for the fit.

IHERG inhibition at different voltages

From −80 mV, 2 s depolarizations were applied to potentials between −40 and +40 mV. IHERG tails were measured on repolarization to −40 mV. Current-voltage (I–V) relations (not shown) were constructed for each of eight cells in the absence and presence of 5 mm 4-AP. Half-maximal activation voltages were obtained by fitting each I–V relation with a modified Boltzmann equation:

|

(3) |

where I =IHERG tail amplitude following test potential Vm, Imax is the maximal IHERG tail current observed, V1/2 is the potential at which IHERG was half-maximally activated and k is the slope factor describing IHERG activation.

Voltage-dependent activation curves for IHERG were obtained by calculating activation variables at 2 mV intervals between −80 and +40 mV. Values for V1/2 and k derived from fits to experimental I–V data with eqn (3) were inserted into the following equation:

|

(4) |

where the ‘activation parameter’ at any test potential, Vm, occurs within the range 0 to 1 and V1/2 and k have similar meanings to those in eqn (3).

Envelope of tails

From −80 mV, membrane potential was stepped to +40 mV for varying time periods between 12.5 and 600 ms and was repolarized to − 40 mV in order to monitor IHERG tail amplitude. After control measurements, each cell was equilibrated in 4-AP-containing solution while at the holding potential and the protocol was then reapplied. For each cell, the fractional block of IHERG tails at each test pulse duration was determined using eqn (1). The plot of mean fractional block versus test pulse duration was then fitted with an equation of the form:

| (5) |

where A represents maximal fractional block, x represents pulse duration and τ is the time constant of development of blockade (ms).

Action potential voltage clamp and measurements from guinea-pig ventricular myocytes

For action potential clamp measurements of IHERG from HEK cells, the command waveform used was the same as that employed in previous studies of IHERG from our laboratory (Hancox et al. 1998a, b).

Action potentials were elicited from guinea-pig ventricular myocytes by brief suprathreshold current pulses at 15 s intervals. For measurements of guinea-pig IK tails, membrane potential was held at −80 mV, depolarized to −40 mV for 20 ms, then depolarized to +20 mV for 500 ms. IK tails were measured during subsequent repolarization to −40 mV.

Data analysis and presentation

Data are presented as means ± s.e.m. Statistical comparisons were made using Student's paired t test or one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with a Bonferroni post hoc test. P values of less than 0.05 were taken as significant.

RESULTS

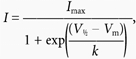

Figure 1A shows that 4-AP produced a concentration-dependent inhibition of IHERG and Fig. 1B shows the mean concentration–response relationship for this effect. The IC50 derived from the data was 4.4 ± 0.5 mm (Hill coefficient 0.7 ± 0.1). The voltage dependence of the effect was assessed by applying commands to a range of test potentials (Fig. 1Ci and Cii). No IHERG tail inhibition was evident after pre-pulses to −30 mV and −20 mV, whilst at more positive potentials marked inhibition of IHERG was observed (Fig. 1Ci and Cii). Mean data are shown in Fig. 1D, which also contains mean activation curves in control (continuous line) and 4-AP (dashed line). In the presence of 4-AP a leftward shift in the half-maximal activation voltage (V1/2; by −7.4 ± 0.9 mV, n = 8; P < 0.0001, t test) was observed. The activation shift may account for the apparent augmentation/ lack of blockade of by 4-AP observed at −30 and −20 mV. The voltage range over which inhibition was voltage dependent corresponded with that over which voltage-dependent activation of IHERG developed (Mergenthaler et al. 2001; Paul et al. 2001). Treatment with 5 mm 4-AP did not significantly alter the mean deactivation time course of tails measured at − 40 mV, following a voltage command to +30 mV.

Figure 1. Concentration and voltage-dependent inhibition of IHERG by 4-AP.

A, upper traces show representative current traces illustrating the effect of different concentrations of 4-AP. Lower trace represents voltage protocol used. B, concentration response relation for IHERG tail blockade by 4-AP (n = 5–8 cells at each concentration). C, representative records in the absence (Ci) and presence (Cii) of 5 mm 4-AP. D, the mean (± s.e.m.) fractional block of IHERG by 5 mm 4-AP over a range of potentials (n = 8 cells). IHERG activation curves are shown in the absence (continuous line) and presence (dashed line) of 5 mm 4-AP.

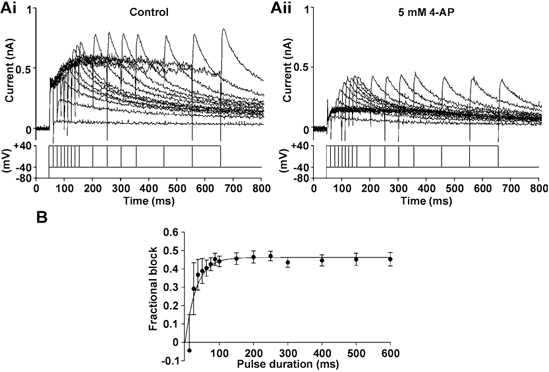

The dependence of IHERG inhibition by 4-AP upon duration of depolarization was studied using an ‘envelope of tails’ protocol (Trudeau et al. 1995) (see Fig. 2A and B). Figure 2A shows representative current traces obtained in control (Fig. 2Ai) and in 4-AP (Fig. 2Aii); Fig. 2B shows a plot of the resulting mean levels of fractional block against pulse duration. The time course of development of blockade was described by a mono-exponential curve that intersected the origin, with a time constant of 32.3 ± 6.4 ms (n = 5). Considered collectively with Fig. 1D these data demonstrate that inhibition of IHERG by 4-AP requires channel gating to occur.

Figure 2. Time dependence of IHERG block by 4-AP.

A, traces from an ‘envelope of tails’ protocol, in the absence (Ai) and presence (Aii) of 5 mm 4-AP. Lower traces represent the voltage protocol used. B, the mean (± s.e.m.) fractional block of IHERG with varying pulse duration (n = 5 cells). The τ for development of inhibition was 32.3 ± 6.4 ms (n = 5).

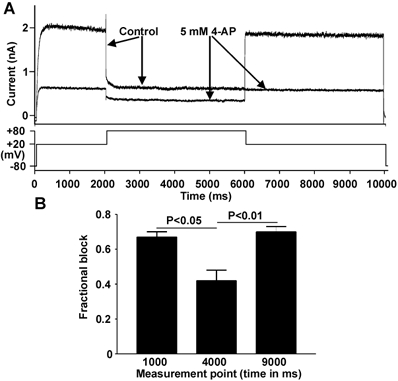

An additional protocol (see Fig. 3A, lower trace) was employed to ascertain whether or not 4-AP showed a preference for activated or inactivated HERG channels. In control solution, IHERG amplitude decreased markedly during a depolarisation from +20 to +80 mV (Fig. 3A, upper traces, Control) as a consequence of increased IHERG inactivation. In the presence of 5 mm 4-AP, blockade of IHERG at +20 mV was greater than that at +80 mV (Fig. 3A, upper traces, 4-AP). Mean data shown in Fig. 3B indicate that blockade during the +80 mV step (‘4000 ms’) was significantly lower than that at +20 mV (‘1000 ms’ and 9000 ms’). Thus, when IHERG was reduced by extensive IHERG inactivation the blocking effect of 4-AP was diminished. This observation suggests that 4-AP binds preferentially to activated over inactivated HERG channels. In further experiments we observed an acceleration of the rate of development of IHERG inactivation by 4-AP (data not shown). This effect is in marked contrast with that reported for externally applied tetraethylammonium ions (TEA), which slow the distinctive, rapidly developing C-type inactivation of IHERG (Smith et al. 1996). This action of 4-AP could have resulted either from a genuine modification of inactivation gating, or from the rapid development of open-channel block during the protocol used to study inactivation.

Figure 3. Effect of strong depolarisation on the action of 4-AP.

A, current records (upper traces) elicited by the voltage protocol shown (lower trace), applied from a holding potential of −80 mV. Arrows indicate traces obtained in control and 4-AP. B, bar charts (n = 5 cells) compare the mean level of blockade at 1000 ms into protocol (at +20 mV), at 4000 ms (at +80 mV) and at 9000 ms (after membrane potential was returned to +20 mV).

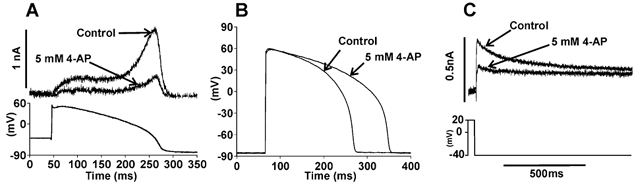

The effect of 4-AP on IHERG elicited by an applied ventricular action potential waveform was also determined (Fig. 4A). In control solution, IHERG amplitude increased progressively through the action potential plateau and was maximal near −30 mV (−30.2 ± 3.4 mV; n = 5; cf. Hancox et al. 1998a). Treatment with 5 mm 4-AP attenuated current throughout the action potential command, inhibiting maximal IHERG by 58.5 ± 4.1 % (n = 5). Also, the voltage at which IHERG peaked was shifted by −10.6 ± 4.1 mV, consistent with the voltage shift in current activation described in Fig. 1. These data suggest that 4-AP might increase the action potential duration in native cardiac tissue through blockade of native IKr, independent of any inhibitory action on ITO,1. Therefore, we measured action potentials from guinea-pig ventricular myocytes, which lack ITO,1 (Coraboeuf et al. 1998). 4-AP exerted little effect immediately after the action potential peak, but the times to reach both 50 % and 90 % repolarization (APD50 and APD90, respectively) were significantly prolonged by 4-AP (Fig. 4B; in control: mean APD50 = 162.2 ± 12.2 ms and APD90 = 184.3 ± 12.2 ms; in 4-AP: APD50 = 210.9 ± 14.6 ms and APD90 = 243.1 ± 14.8 ms, n = 8; P < 0.01 and P < 0.001, respectively). In complementary voltage-clamp experiments, resurgent IK tails (sensitive to the IKr blocker E-4031) from guinea-pig myocytes were also inhibited by 4-AP (Fig. 4C).

Figure 4. Effect of 4-AP under action potential conditions.

A, representative records of IHERG, after P/4 leak subtraction, (upper traces) activated by ventricular action potential command (lower trace), in control and in the presence of 5 mm 4-AP. B, effect of 5 mm 4-AP on action potentials from guinea-pig ventricular myocytes. C, effect of 4-AP on resurgent IK tails from a guinea-pig ventricular myocyte (upper traces; lower trace shows a section of the voltage protocol. A mean inhibition of 71.1 ± 4.3 % was observed (n = 6).

DISCUSSION

The dependence of HERG blockade by 4-AP upon channel gating observed in this study differs from the mechanism underlying its blockade of cardiac ITO,1, which depends considerably upon the agent binding to the closed channel (Castle & Slawsky, 1993; Wang et al. 1995). ITO,1 from rat, rabbit and human have been reported to be blocked by 4-AP with IC50 values of 0.14, 0.33 and 0.67 mm, respectively, whilst Kv 4.3 current exhibits an IC50 of 1.54 mm (Xu et al. 1998; Faivre et al. 1999; Lei et al. 2000). Therefore, whilst 4-AP is clearly a low affinity HERG blocker, its IC50 for IHERG inhibition falls within a 4-AP concentration range used to block ITO,1 selectively in previous studies (typically 0.5–10 mm; Wang et al. 1991; Gillis et al. 1998; Elizalde et al. 1999; Lei et al. 2000; Kocic et al. 2002). The fact that some level of IKr blockade may also have occurred in such experiments is supported by the present data from guinea-pig myocytes, which lack ITO,1, and by previous data regarding reduction of IK tails from rabbit nodal cells (Mitcheson & Hancox, 1999). On the basis of our findings, we conclude that millimolar concentrations of 4-AP can block IHERG/IKr and, thereby, prolong cardiac action potential repolarization independently of any action on ITO,1. In light of these observations, it may be necessary to consider carefully the interpretation of experiments in which millimolar 4-AP has been used as a pharmacological tool to study cardiac ITO,1 in species that also exhibit IKr. Of course, in vitro data must only be extrapolated to the in vivo situation with caution and there is evidence that 4-AP infusion regimens used to study the role of ITO,1 in the dog (del Balzo & Rosen, 1992) may actually attain submillimolar plasma levels (Nattel et al. 2000). Our data are concordant with the notion that micromolar 4-AP may justifiably be used to study IKur in cells that exhibit IKr, as comparatively little IKr blockade would be expected at the low concentration levels (e.g. Yue et al. 1996) required to inhibit IKur.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from the British Heart Foundation, Wellcome Trust and a University of Bristol PhD studentship to J.M.R. The authors thank Lesley Arberry for technical assistance and Dr Andrew James for comments on the manuscript.

References

- Castle NA, Slawsky MT. Characterization of 4-aminopyridine block of the transient outward K+ current in adult rat ventricular myocytes. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1993;265:1450–1459. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coraboeuf E, Coulombe A, Deroubaix E, Hatem S, Mercadier JJ. Transient outward potassium current and repolarization of cardiac cells. Bull Acad Natl Med. 1998;182:325–333. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- del Balzo U, Rosen MR. T wave changes persisting after ventricular pacing in canine heart are altered by 4-aminopyridine but not by lidocaine. Implications with respect to phenomenon of cardiac ‘memory’. Circulation. 1992;85:1464–1472. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.85.4.1464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elizalde A, Barajas H, Navarro-Polanco R, Sanchez-Chapula J. Frequency-dependent effects of 4-aminopyridine and almokalant on action-potential duration of adult and neonatal rabbit ventricular muscle. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 1999;33:352–359. doi: 10.1097/00005344-199903000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faivre JF, Calmels TP, Rouanet S, Javre JL, Cheval B, Bril A. Characterisation of Kv4. 3 in HEK293 cells: comparison with the rat ventricular transient outward potassium current. Cardiovasc Res. 1999;41:188–199. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(98)00215-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gillis AM, Geonzon RA, Mathison HJ, Kulisz E, Lester WM, Duff HJ. The effects of barium, dofetilide and 4-aminopyridine (4-AP) on ventricular repolarization in normal and hypertrophied rabbit heart. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1998;285:262–270. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hancox JC, Levi AJ, Witchel HJ. Time course and voltage dependence of expressed HERG current compared with native ‘rapid’ delayed rectifier K current during the cardiac ventricular action potential. Pflugers Arch. 1998a;436:843–853. doi: 10.1007/s004240050713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hancox JC, Witchel HJ, Varghese A. Alteration of HERG current profile during the cardiac ventricular action potential, following a pore mutation. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1998b;253:719–724. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1998.9837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Isenberg G, Klockner U. Calcium tolerant ventricular myocytes prepared by preincubation in a ‘KB medium’. Pflugers Arch. 1982;395:6–18. doi: 10.1007/BF00584963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kocic I, Hirano Y, Hiraoka M. Rate-dependent changes in action potential duration and membrane currents in hamster ventricular myocytes. Pflugers Arch. 2002;443:353–361. doi: 10.1007/s004240100683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lei M, Honjo H, Kodama I, Boyett MR. Characterisation of the transient outward K+ current in rabbit sinoatrial node cells. Cardiovasc Res. 2000;46:433–441. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(00)00036-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levi AJ, Issberner J. Effect on the fura-2 transient of rapidly blocking the Ca2+ channel in electrically stimulated rabbit heart cells. J Physiol. 1996;493:19–37. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1996.sp021362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li GR, Feng J, Yue L, Carrier M, Nattel S. Evidence for two components of delayed rectifier K+ current in human ventricular myocytes. Circ Res. 1996;78:689–696. doi: 10.1161/01.res.78.4.689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu XK, Wang W, Ebert SN, Franz MR, Katchman A, Woosley RL. Female gender is a risk factor for torsades de pointes in an in vitro animal model. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 1999;34:287–294. doi: 10.1097/00005344-199908000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mergenthaler J, Haverkamp W, Huttenhofer A, Skryabin BV, Musshoff U, Borggrefe M, Speckmann EJ, Breithardt G, Madeja M. Blocking effects of the antiarrhythmic drug propafenone on the HERG potassium channel. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol. 2001;363:472–480. doi: 10.1007/s002100000392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitcheson JS, Hancox JC. Characteristics of a transient outward current (sensitive to 4-aminopyridine) in Ca2+-tolerant myocytes isolated from the rabbit atrioventricular node. Pflugers Arch. 1999;438:68–78. doi: 10.1007/s004240050881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitcheson JS, Sanguinetti MC. Biophysical properties and molecular basis of cardiac rapid and slow delayed rectifier potassium channels. Cell Physiol Biochem. 1999;9:201–216. doi: 10.1159/000016317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nattel S, Matthews C, De Blasio E, Han W, Li D, Yue L. Dose-dependence of 4-aminopyridine plasma concentrations and electrophysiological effects in dogs : potential relevance to ionic mechanisms in vivo. Circulation. 2000;101:1179–1184. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.101.10.1179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paul AA, Witchel HJ, Hancox JC. Inhibition of HERG potassium channel current by the class 1a antiarrhythmic agent disopyramide. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2001;280:1243–1250. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2001.4269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith PL, Baukrowitz T, Yellen G. The inward rectification mechanism of the HERG cardiac potassium channel. Nature. 1996;379:833–836. doi: 10.1038/379833a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trudeau MC, Warmke JW, Ganetzky B, Robertson GA. HERG, a human inward rectifier in the voltage-gated potassium channel family. Science. 1995;269:92–95. doi: 10.1126/science.7604285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang ZG, Fermini B, Nattel S. Repolarization differences between guinea pig atrial endocardium and epicardium: evidence for a role of Ito. Am J Physiol. 1991;260:H1501–1506. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1991.260.5.H1501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Z, Fermini B, Nattel S. Effects of flecainide, quinidine, and 4-aminopyridine on transient outward and ultrarapid delayed rectifier currents in human atrial myocytes. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1995;272:184–196. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warmke JW, Ganetzky B. A family of potassium channel genes related to eag in Drosophila and mammals. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1994;91:3438–3442. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.8.3438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu WH, Li W, Yue HW, Wang XL. Characteristics of transient outward K+ current in human atrial cardiomyocytes. Zhongguo Yao Li Xue Bao. 1998;19:481–485. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yue L, Feng J, Li GR, Nattel S. Characterization of an ultrarapid delayed rectifier potassium channel involved in canine atrial repolarization. J Physiol. 1996;496:647–662. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1996.sp021716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang H, Holden AV, Kodama I, Honjo H, Lei M, Varghese T, Boyett MR. Mathematical models of action potentials in the periphery and center of the rabbit sinoatrial node. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2000;279:H397–421. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.2000.279.1.H397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou Z, Gong Q, Ye B, Fan Z, Makielski JC, Robertson GA, January CT. Properties of HERG channels stably expressed in HEK 293 cells studied at physiological temperature. Biophys J. 1998;74:230–241. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(98)77782-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]