Abstract

We recently characterized two distinct mechanisms by which the polyamine spermine blocks Kir2.1 channels: (1) by reduction of negative surface charges in the cytoplasmicpore, thereby reducing single-channel conductance, and (2) by direct open channel transmembrane pore block. The extent to which the surface charge reduction component is mediated by passive surface charge screening versus binding of polyamines to these charges, as well as the extent to which the surface charge reduction and pore block mechanisms are synergistic, versus simply additive, was not established. To address these issues, macroscopic currents were recorded from inside-out giant patches from Xenopus oocytes and from single-channel currents from COS7 cells expressing wild-type and mutant Kir2.1 channels, during exposure to polyamines of varying length and charge. The surface charge reduction component was decreased when polyamine charge (at constant length) was decreased from 4 (spermine) to 2 (diamine 10, DA10). Moreover, the surface charge reduction component of block involved more than passive surface charge screening and required binding of polyamines to the cytoplasmic pore, since it was eliminated when polyamine length was shortened below six alkyl groups. Loss of surface charge reduction also dramatically affected open channel pore block. The latter consisted of two subcomponents with fast and slow kinetics, respectively. The slow subcomponent decreased as blocker length decreased (DA10, DA8 and DA6), whereas the fast subcomponent was sensitive to blocker charge (spermine vs. DA10). Neutralization of E224 and E299, which eliminated the surface charge reduction component of block, also eliminated the fast subcomponent of pore block. Neutralization of D172 had no effect on the surface charge reduction component, but weakened both of the subcomponents of pore block. These findings can be accounted for by a model in which the negative charges at E224, E299 and D172 act in a concerted manner to coordinate the surface charge reduction and open channel components of polyamine block. In this model, the binding of polyamines to surface charges E224 and E299 pre-positions them in the cytoplasmic pore in a manner that directly facilitates their entry and exit from a transmembrane pore-occluding site involving D172. A molecular model using the recently reported 1.8 Å resolution structure of the inward-rectifier cytoplasmic pore, adapted to Kir2.1, is consistent with longer polyamines binding at their positively charged ends to the E224 and E299 positions in the same subunit, potentially accommodating four polyamine molecules per channel.

Inward-rectifier K+ (Kir) channels play an essential role in stabilizing the resting membrane potential and regulating excitability in many cell types (Doupnik et al. 1995; Hille, 2001). As their name indicates, Kir channels conduct inward current more readily than outward current, a property that is attributed to voltage-dependent block of outward currents by Mg2+ and polyamines (Matsuda et al. 1987; Vandenberg, 1987; Ficker et al. 1994; Lopatin et al. 1994; Fakler et al. 1995). Recent structural studies have characterized the Kir pore as consisting not only of the classic ‘transmembrane pore’, but also a ‘cytoplasmic pore’ formed by regions of the cytoplasmic N and C termini. Negatively charged residues in these two different pore regions of the Kir2.1 channel have been identified as critical for polyamine and Mg2+-induced strong inward rectification: D172 in the M2 or transmembrane pore region (Lu & Mackinnon, 1994; Stanfield et al. 1994; Wible et al. 1994; Yang et al. 1995), and E224 and E299 in the cytoplasmic C-terminus or cytoplasmic pore region (Taglialatela et al. 1995; Yang et al. 1995; Kubo & Murata 2001). Another residue, S165, also in the transmembrane pore, has been shown to be important for Mg2+, but not polyamine, block (Fujiwara & Kubo, 2002).

Block by polyamines has a complex dependence on both voltage and concentration. We have recently proposed that spermine blocks Kir2.1 channels by two distinct mechanisms (Xie et al. 2002). The first mechanism involves a component with shallow voltage and concentration dependence predominating at negative voltages. This block causes a reduction in the single-channel conductance due to the reduction of negative surface charges in the cytoplasmic pore by either classical surface charge screening and/or binding of polyamines to E224/E299 residues. The second mechanism involves a steep voltage-dependent component predominating at positive voltages, which has been attributed to the open-channel block in the transmembrane pore. Mutagenesis experiments indicated that E224 and E299 are the major negative surface charges in the cytoplasmic pore of the channel accounting for the surface charge reduction component (Xie et al. 2002). Since these same residues also strongly regulate the affinity of polyamine block, the possibility arises that the two components of polyamine block are more than simply additive, and may act synergistically to facilitate polyamine block. Although this possibility has been suggested previously (Kubo & Murata, 2001; Xie et al. 2002), it has yet to be demonstrated conclusively. In our previous study we did not ascertain whether spermine merely passively screens E224 and E299, or actually binds to these residues to reduce the local negative surface potential. In the former case, the two components of block should be additive, whereas in the latter, they might act synergistically by pre-positioning the polyamine in the cytoplasmic pore and thereby facilitating its entry and exit from the transmembrane pore-occluding site involving D172.

In the present study we have examined this issue in more detail by comparing the effects of polyamine blockers of different lengths and charges, including spermine, spermidine and both diaminoalkane (diamine, DA) and monoaminoalkane (monoamine, MA) analogues of polyamines. Our findings support strongly the hypothesis that negative charges at E224, E299 and D172 act in a coordinated and synergistic manner to facilitate polyamine block in Kir2.1 channels. The cytoplasmic pore effectively concentrates and orders polyamine molecules, which then occlude the transmembrane pore. Using the recently described 1.8 Å resolution cytoplasmic pore structure of Kir3.1 (Nishida & MacKinnon, 2002) as a template for Kir2.1, we present a molecular model in which polyamines with a length of eight or more alkyl groups bind at their positively charged ends to the E224 and E299 positions in the same subunit, potentially accommodating four polyamine molecules per channel.

METHODS

The methods used for this study have been described in detail previously (Xie et al. 2002). Briefly, cRNAs (≈ 50 nl, 1–100 ng ml−1) of Kir2.1 (Kubo et al. 1993; cDNA generously provided by Dr Lily Y. Jan at UCSF) and mutants were synthesized using T7 polymerase (Ambion) and injected into isolated stage IV-V Xenopus oocytes (for detail of the isolation of oocytes see Shieh et al. 1996; Lee et al. 1999). Xenopus oocytes were collected from anaesthetized frogs (0.15–0.17 % tricaine), which were killed humanely after the final collection. The use and care of the animals in these experiments were approved by the Chancellor's Animal Research Committee at UCLA. Macroscopic currents were recorded from excised inside-out giant patches from injected oocytes with an Axopatch 200A amplifier (Axon Instruments) 24–72 h after injection. Patch electrodes were pulled from thin-wall borosilicate glass (Garner Glass, Claremont, CA, USA) and had a tip diameter of 20–30 μm after fire polishing. The patch electrode solution contained (mM): 85 KCl, 1.8 CaCl2, 5 K2HPO4, 5 KH2PO4 (pH 7.4 with KOH). The standard bath solution contained (mM): 75 KCl, 5 K2EDTA, 5 K2HPO4, 5 KH2PO4 (pH 7.2 with KOH). Current through Kir2.1 channels was measured by subtracting the current recorded in 30 mM TEA solution from the total measured current.

Single-channel currents were recorded from inside-out patches excised from COS7 cells transfected with Kir cDNA, using an Axopatch 200B amplifier (Axon Instruments). Patch electrodes were pulled from thick-walled borosilicate glass (Warner Instruments, Inc.) and had a resistance of 5–8 MΩ when filled with the pipette solution. Electrodes were coated near their tips with Sylgard (Dow Corning) or N,N-dimethyltrimethylsilylamine (Fluka) to reduce electrical capacitance. The total [K+] in the pipette solution and bath solution was 140 mM. Non-transfected cells were studied using the same protocol to detect endogenous channels with similar properties to Kir2.1 (inward rectification in the cell-attached mode, reversal potential at 0 mV in symmetrical [K+], characteristic long open-time, short closed-time channel kinetics with high open probability, and block by intracellular TEA), but none were observed.

Data were filtered with an eight-pole Bessel filter (Frequency Devices) at 5 kHz and digitized at 10 kHz via a DigiData 1200 interface (Axon Instruments). Data acquisition and analysis were carried out using pCLAMP 6 or 7 software (Axon Instruments).

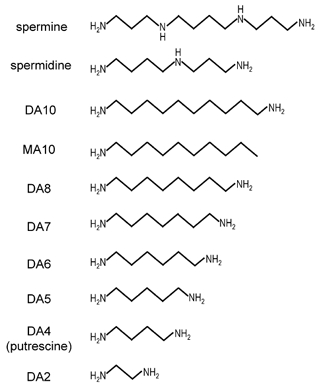

The structures of the polyamines and their alkylamine analogues used in this study (all purchased from Sigma) are shown in Fig. 1. DA10, DA8 and MA10 were first dissolved in EtOH; all others were dissolved in water to make 100 mM stock solutions, which were then added into the perfusing solutions at their final concentrations.

Figure 1. Chemical structures of the polyamines and their alkylamine analogues used in this study.

DA, diamine; MA, monoamine.

All experiments were conducted at room temperature (20–24 °C). Modelling and curve fitting were performed using a commercially available simulation package (Scop 3.5, Simulation Resource).

The currents in the presence of polyamines were fitted to double Boltzmann equations:

where I is the measured current, Ictl is the control current in the absence of polyamines, V0.5,1 and V0.5,2 are the half-maximum inhibition potentials, δz1 and δz2 are the effective valencies, A0 is the offset, A1 and A2 are scaling factors, and F, R and T have their usual meanings. For analysis purposes, the Boltzmann with shallow voltage dependence is taken to represent the surface charge reduction component, and the Boltzmann with steeper voltage dependence is taken to represent either the fast or the slow pore block component, for the quasi-instantaneous and steady-state current-voltage (I-V) curves, respectively. The kinetics of unblock were fitted to a single exponential function: I =B exp(−t/τ) +B0, where I is the current amplitude, B the scaling factor, B0 the offset, and τ a time constant.

The structural model of the Kir2.1 channel was created by SWISS-MODEL (Guex & Peitsch, 1997) using the Kir3.1 coordinates (PDB code 1N9P) reported by Nishida & MacKinnon (2002) as a template. The coordinates of the tetramer were kindly provided by Dr R. MacKinnon (Rockefeller University, NY, USA). After alignment to the template, the sequence of Kir2.1 was sent to the server (http://us.expasy.org/spdbv/) to generate the model. With sequence identity of 57.7 % between Kir2.1 and Kir3.1 (crystallized portions), the predicted Kir2.1 structure remained very similar overall to the Kir3.1 structure, with the root mean square (r.m.s.) of the backbone 0.01 Å when the model included only the crystallized portions. The predicted Kir2.1 cytoplasmic pore model and the structures of polyamines were viewed and edited using Swiss-PdbViewer software, which also permitted inter-residue distances to be measured.

RESULTS

Components of Kir2.1 channel block by polyamines

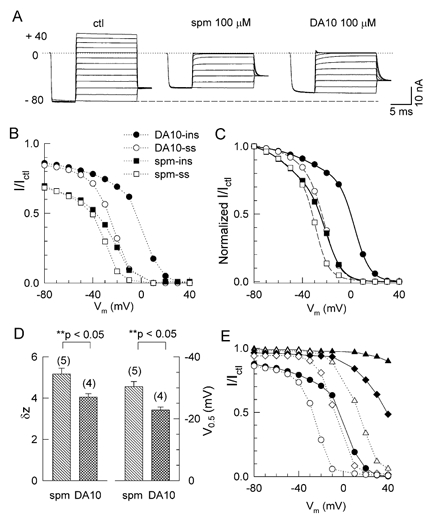

Figure 2A shows three sets of macroscopic currents recorded in excised inside-out patches from oocytes expressing wild-type Kir2.1 channels. After a prepulse to −80 mV, the patch was clamped to various test potentials between −80 and +40 mV in 10 mV increments, under control conditions (left panel) and after application of 100 μM spermine (middle panel) or DA10 (right panel). Control currents (Ictl) were recorded ≈5 min after the patch was excised into Mg2+ and polyamine-free solution, such that inward rectification had largely disappeared and the I-V relationship was almost linear in both the inward and outward directions. It has been demonstrated that the loss of the inward rectification in inside-out patches is a result of the washout of blocking particles such as polyamines (Lopatin et al. 1994) and Mg2+ (Matsuda et al. 1987; Vandenberg, 1987) from the cytoplasmic surface of the patch.

Figure 2. Comparison of spermine and DA10 block.

A, macroscopic Kir2.1 currents from a giant inside-out membrane patch during voltage clamps from −80 and +40 mV in 10 mV increments, after a brief prepulse (activating step) to −80 mV, in the absence (ctl) and presence of 100 μM spermine (spm) or diamine 10 (DA10). Vm, membrane potential. The dotted line indicates the zero current level and the dashed line is the extension of the current level at −80 mV under control conditions. B, the I-V curve for the quasi-instantaneous (ins, filled symbols) and steady state (ss, open symbols) currents (I) in the presence of spermine (squares) or DA10 (circles), relative to current in their absence (Ictl). C, I-V curves in B were normalized to the value of current at −80 mV and fitted to double-Boltzmann equations (see Methods). The continuous lines are the best fits to the instantaneous current data in the presence of spermine (▪) and DA10 (•); the dashed line is the best fit to the steady-state current values for spermine (□) and DA10 (○). D, mean (±s.e.m.) effective valency (δz, left) and the voltage causing half-maximal block (V0.5, right) obtained from the Boltzmann fits in the presence of 100 μM spermine or DA10, for the number of patches indicated. E, relative currents (I/Ictl) of the quasi-instantaneous (ins) and steady state (ss) currents in the presence of DA10 plotted against voltage, for the DA10 concentrations of 1 (▴, ins; ▵, ss), 10 (♦, ins; ⋄, ss) and 100 μM (•, ins; ○, ss).

Adding 100 μM spermine or DA10 to the bath (cytoplasmic) solution blocked the currents and restored the strong inward rectification. As demonstrated in our recent study (Xie et al. 2002), there are two main components of polyamine block: (1) a surface charge reduction effect with shallow voltage dependence predominating at more negative voltages, which reduces single-channel conductance, and (2) a pore-blocking effect with steep voltage dependence predominating at less negative voltage (> −40 mV).

To illustrate the components of block better, the currents measured in the presence of spermine or DA10 (I) were normalized to the corresponding current in the absence of spermine (Ictl). The normalized I-V curves for the quasi-instantaneous current (Iins, measured immediately after capacity transient) and quasi-steady-state current (Iss, measured at the end of the pulse) in the presence of spermine and DA10 are plotted in Fig. 2B. We used the reduction of the current at −80 mV as an index of the surface charge reduction component of block (Xie et al. 2002), since the double-Boltzmann fits typically indicated insignificant contamination (< 1 %) by the pore block component at potentials more negative than −50 mV over the range of polyamine concentrations tested. In addition to this component of block, the I-V curves show that at voltages >-40 mV, there are two subcomponents of the pore-blocking effect, with quasi-instantaneous and slow kinetics, respectively. Therefore block of Kir2.1 by polyamines has three separable components: surface charge reduction, fast block (indicated by the Iins/Ictl -V relationship), and slow block (indicated by the Iss/Ictl -V relationship).

Effects of blocker charge

We compared the surface charge reduction component (the inhibitory effect at −80 mV) of 100 μM spermine with that of 100 μM DA10; spermine and DA10 have similar total lengths (10 methylene groups) but different positive charges (+4 and +2, respectively). As expected from its lesser positive charge, DA10 had a smaller surface charge reduction effect than spermine (Fig. 2B, also summarized in Fig. 5D).

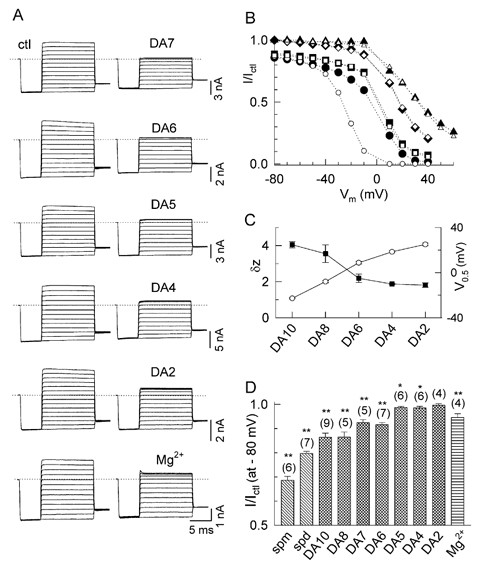

Figure 5. Comparison of block by diamines of different lengths and Mg2+.

A, original Kir2.1 current recordings in the absence (ctl, left panels) and presence of 100 μM DA7, DA6, DA5, DA4, DA2 and Mg2+ (right panels). Note the absence of the slowly developing component of block as diamine length is shortened from DA10 to DA6 (compare to the current traces for DA10 in Fig. 2A and DA8 in Fig. 4). The test voltage is from −80 to +60 mV for DA2 instead of to +40 for other diamines and Mg2+. B, the ratio of the current (I/Ictl) in the presence and absence of DA10 (circles), DA6 (squares), DA4 (diamonds) and DA2 (triangles) vs. voltage, for both quasi-instantaneous (ins, filled symbols) and steady-state current (ss, open symbols). C, effective valency (δz, ▪) and V0.5 (○) of block from the double-Boltzmann equation fits, as a function of alkyl chain length. D, bar graph summarizing the relative current values (I/Ictl) at −80 mV in the presence of 100 μM spermine, spermidine, diamines and Mg2+. Values are mean ±s.e.m. *P > 0.05 and **P < 0.05 compared to DA2 value.

For the pore-block components, there was a larger difference between the Iins-V and Iss-V curves for DA10 than spermine, suggesting that the fast subcomponent of block by DA10 was weaker than spermine at the same concentration. In Fig. 2C, the relative currents were normalized by scaling the values of I/Ictl at −80 mV to unity. The best fits for both spermine and DA10 block to double-Boltzmann equations (see Methods) are shown as the dashed (Iss) and continuous lines (Iins), respectively. For the Iss-V curve, the effective valency (δz) for the second (pore block) Boltzmann component for DA10 is 4.0 ± 0.2 (n = 4) and for spermine is 5.2 ± 0.3 (n = 5). The V0.5 was more positive for DA10 (−22.8 ± 0.5 mV, n = 4) than for spermine (−30.3 ± 0.8 mV, n = 5; Fig. 2D). For the Iins-V curve, spermine and DA10 had a larger shift of V0.5 by ≈25 mV.

These results suggest that decreasing blocker charges from 4 (spermine) to 2 (DA10) not only attenuated the charge reduction effect, but also decreased the potency of the pore-blocking effect, especially the fast component, which is consistent with an interaction between the two components of block.

Figure 2E shows the I-V curves in the presence of different DA10 concentrations (1, 10 and 100 μM). Both Iins (filled symbols) and Iss (open symbols) components are concentration dependent; with increasing DA10 concentration, the I-V curves shift in parallel toward more negative membrane potentials.

Figure 3A shows the unblocking kinetics of spermine (upper panel) and DA10 (lower panel) as a function of voltage. Currents were activated by prepulses to −80 mV and then to +40 mV, followed by a test pulse from +40 to −80 mV in 10 mV steps. At 100 μM, spermine and DA10 completely blocked the current at +40 mV. Block was partially relieved by clamping to negative voltages, but a residual block due to the surface charge reduction effect remained. The values and voltage dependence of τ were similar for both spermine and DA10 (Fig. 3B). Thus, the charge on the polyamine had no significant effect on the unblocking kinetics or voltage dependence.

Figure 3. Unblock kinetics of spermine and DA10 (100 μM).

A, original current recordings in the absence (ctl) and presence of spermine (upper) and DA10 (lower). The currents were activated by a prepulse to −80 mV and then clamped to +40 mV, followed by a test pulse from +40 to 80 mV in 10 mV steps. B, voltage dependence of time constants (τ) for spermine and DA10 unblock obtained from exponential fits to the current traces in A.

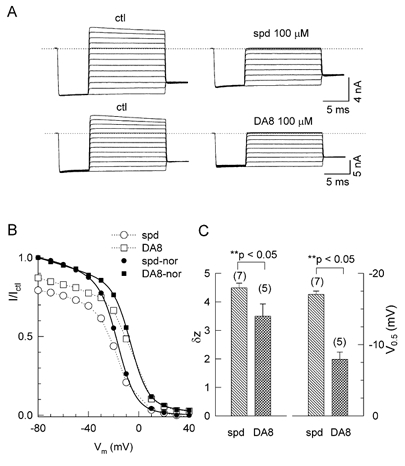

As the alkyl backbone of the polyamine is shortened, it has been shown that the kinetics of block and unblock accelerate (Pearson & Nichols, 1998). Whereas spermine and DA10 have 10 methylene groups, spermidine (with three positively charged amide groups) has seven methylene groups, and can be compared to DA8 (with two positively charged amide groups and eight methylene groups). Figure 4A shows original current traces in the absence (ctl) and presence of 100 μM spermidine (spd, upper) or DA8 (lower). The slow component of pore block was no longer resolvable for either spermidine or DA8, therefore we plotted the I-V relationship for the relative steady-state current only in Fig. 4B. The surface charge reduction effect at −80 mV was more potent with 100 μM spermidine than DA8 (Fig. 4B and Fig. 5D). Fitting double-Boltzmann equations to the normalized data (continuous lines and filled symbols in Fig. 4B) shows that, analogous to spermine vs. D10, spermidine blocked the channel more potently than DA8 (V0.5=−17.0 ± 0.5 mV for spermidine, n = 7, vs. −7.9 ± 1.0 mV for DA8, n = 5), for the pore-block Boltzmann component). The effective valency for spermidine pore block (4.5 ± 0.2, n = 7) was higher than DA8 (3.6 ± 0.5, n = 5). Thus, the effects of polyamine charge for spermidine vs. DA8 were similar to the effects for spermine vs. DA10.

Figure 4. Comparison of spermidine and DA8 (100 μM) block.

A, original current recordings in the absence (ctl) and presence of 100 μM spermidine (spd, upper) or DA8 (lower), using the same voltage protocol as in Fig. 1. B, the ratio of the steady-state current (I) in the presence of spermidine (○) or DA8 (□) to that in their absence (Ictl) plotted against voltage. The ratios are also scaled to unity (filled symbols) and fitted to double-Boltzmann equations (continuous lines). C, mean (±s.e.m.) effective valency (left) and V0.5 (right) obtained from the double-Boltzmann fits in the presence of 100 μM spermidine or DA8, for the number of patches indicated.

Effect of blocker length

If the surface charge reduction component of block by polyamines involves passive charge screening only, then the length of the polyamines alkyl chain should have no effect on the potency of surface charge reduction. Figure 5 compares Kir 2.1 current inhibition by diaminoalkane blockers with the same charge but different alkyl chain lengths ranging from 2 to 10 methylene groups (DA2- DA10). Representative current traces for DA7, DA6, DA5, DA4, DA2 and Mg2+ are shown in Fig. 5A, and for DA10 and DA8 in Fig. 2A and Fig. 4A. As summarized in Fig. 5D, the diamines with lengths of 2–5 methylene groups (DA2-DA5) had negligible charge reduction effects, DA6 and DA7 had intermediate effects, and longer diamines such as DA8 and DA10 had strong surface charge reduction effects. These findings provide strong evidence that surface charge reduction by longer polyamines involves their binding to negatively charged residues in the cytoplasmic pore, rather than passive surface charge screening alone. Furthermore, a critical length of alkyl backbone ≥ six methylene groups appears to be important in stabilizing the charge-charge interaction for polyamines (see Discussion for details). These findings are consistent with predictions of surface potential theory (e.g. Hille, 2001), since the theoretically predicted additional screening of a negative surface potential of −75 mV achieved by adding 0.1 mM divalent cations to a solution already containing 100 mM monovalent cations is <1 %.

We also compared the surface charge reduction potency of diamines with equimolar Mg2+. Mg2+ had an intermediate surface charge reduction effect (0.95 ± 0.02, Fig. 5D), comparable to DA6 and DA7, suggesting that Mg2+ also reduces negative surface potential in the cytoplasmic pore by binding rather than by purely passive surface charge screening.

In contrast to DA10, pore block by short diamines (DA8-DA2) was too fast to resolve into separable components (i.e. the relative currents (I/Ictl) for both Iins and Iss were nearly superimposable; Fig. 5B). Similarly, unblock rates for short diamines were very rapid compared to DA10. Thus, the kinetics of block and unblock are very sensitive to polyamine length when the charge is constant. The V0.5 and δz values obtained from the best fitting to the Boltzmann equations for the diamines of various lengths are compared in Fig. 5C. Both the blocking potency (as indicated by V0.5 shifted towards more negative voltages) and effective valency increased with increasing in alkyl chain length.

Effects of neutralizing negative charges in the transmembrane and cytoplasmic pore

It has been demonstrated that the negatively charged residues within the cytoplasmic pore (E224 and E299) and in the transmembrane channel pore (D172) are crucial for polyamine block (Lu & Mackinnon, 1994; Stanfield et al. 1994; Wible et al. 1994; Taglialatela et al. 1995; Yang et al. 1995; Kubo & Murata, 2001). In addition, we have shown previously that E224 and E299 are the major contributors to the reduction of the surface charge component of block by spermine (Xie et al. 2002). If E224 and E299 are involved in binding DA10 and pre-positioning it for pore block, then neutralizing these residues should alter pore block characteristics in addition to eliminating the surface charge reduction component of block by DA10. We therefore investigated the effects of DA10 in channels with the above negative charges neutralized.

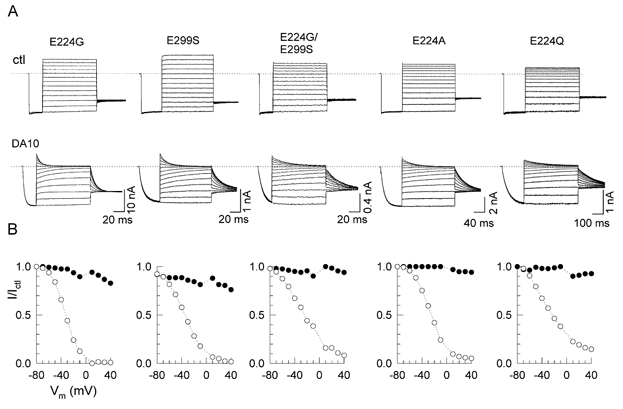

Figure 6 shows the effects of DA10 on E224G, E299S, E224G/E299S, E224A and E224Q channels. In the absence of polyamines and Mg2+, some of these mutants (most prominently E224Q) showed a blocker-independent inward rectification. More importantly, in the presence of DA10, the surface charge reduction component of block was eliminated whenever E224 was neutralized, and significantly attenuated when E299 alone was neutralized (Fig. 6A and B). In addition, the fast subcomponent of pore block by DA10 was markedly diminished in all of these mutants (Fig. 6B). Thus, the negative charges at E224 and E299, rather than steric factors, appear to be primarily responsible for binding DA10. This binding both reduces surface charge and regulates the fast component of pore block by DA10. These components of block were not sensitive to diamine length, since surface charge reduction effects and fast pore block by DA6 were also eliminated by the E224G/E299S mutation (Fig. 7).

Figure 6. Effects of DA10 in the E224G, E299S, E224G/E299S, E224A and E224Q channels.

A, currents in the absence (upper) and presence (lower) of 100 μM DA10. B, the ratio of the current (I/Ictl) in the presence and absence of DA10 versus voltage, for both the instantaneous (•) and steady-state (○) current.

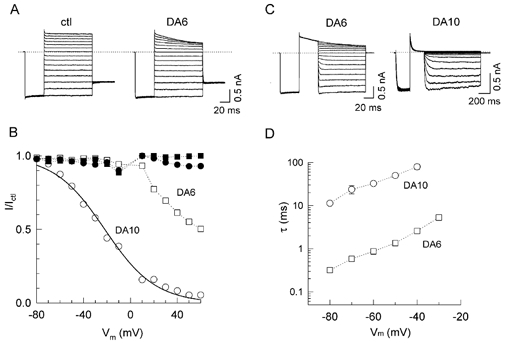

Figure 7. Effects of DA10 versus DA6 (100 μM) on E224G/E299S channels.

A, original current recordings in the absence (ctl) and presence of DA6. B, the ratio of the steady-state current (I/Ictl) in the presence and absence of DA6 (squares) and DA10 (circles) versus Vm. Filled symbols show the corresponding ratios for the instantaneous current, illustrating that fast pore block is absent with both DA6 and DA10. C, original current recordings in the presence of 100 μM DA6 and DA10 showing relief of block. D, voltage dependence of unblock time constants (τ) for DA6 (□) and DA10 (○).

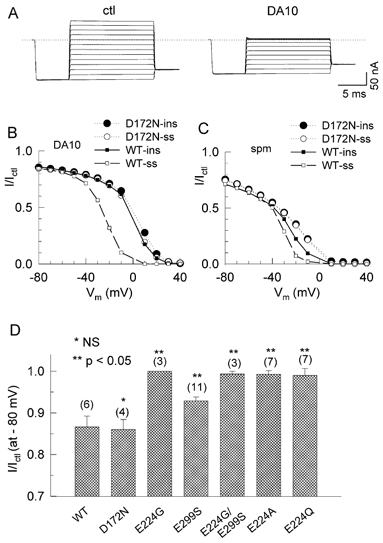

In contrast, the sole remaining component of block in E224G/E299S, slow pore block, was sensitive to diamine length. Figure 7 compares the effects of DA6 vs. DA10 (both 100 μM) in E224G/E299S channels. Figure 7A shows representative current traces for DA6, which can be compared to DA10 in Fig. 6A. DA6 had a much lower affinity (V0.5=≈+60 mV, vs. −22 mV for DA10, Fig. 7B). The lower affinity of DA6 could be attributed largely to its much faster unblocking rate compared to DA10 (Fig. 7C and D). These findings suggest that the alkyl backbone of the polyamine interacts hydrophobically with the lining of the pore to stabilize polyamine binding near D172. The slow component of pore block and unblock for DA10 required the negative charge at D172, since slow block and unblock disappeared when D172 was neutralized (D172N, Fig. 8A and B). Figure 8C shows the results of spermine block in D172N compared to the wild-type channel. The I/Ictl -V curves for D17N were shifted to the right for both the steady-state and instantaneous currents from the wild-type channel, suggesting that the D172N mutation attenuated both the slow and fast pore block. In contrast to the E224 and E299 mutations, neutralization of D172 had no effect on the surface charge reduction component of block, as shown in Fig. 8D, which summarizes the inhibitory effects of DA10 at −80 mV in the wild-type and mutant channels.

Figure 8. Effects of polyamines on D172N channels.

A, original current recordings from D172N channels in the absence (ctl) and presence of 100 μM DA10. B, the ratio of the current (I/Ictl) in the presence and absence of DA10 versus voltage, for both the quasi-instantaneous (ins, •) and steady-state (ss, ○) currents in D172N channels. The comparable data in wild-type (WT) channels for instantaneous current (▪ and continuous line) and steady-state current (□ and dashed line) are shown for comparison. C, the ratio of the current (I/Ictl) in the presence and absence of spermine versus voltage, for both the quasi-instantaneous (ins, •) and steady state (ss, ○) currents in D172N channels. The comparable data in WT channels for instantaneous current (▪ and continuous line) and steady-state current (□ and dashed line) are shown for comparison. D, charge reduction potency of 100 μM DA10 on WT, D172N, E224G, E299S, E224G/E299S, E224A and E224Q channels. Graph compares the ratio of current (I/Ictl) at −80 mV in the presence and absence of 100 μM DA10 for the number of patches indicated (mean ±s.e.m.). *P > 0.05 and **P < 0.05 compared to WT channels.

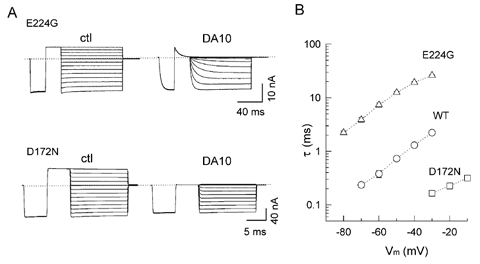

Figure 9 illustrates the unblocking kinetics of DA10 in E224G and D172N channels. The original current records in the absence and presence of 100 μM DA10 are shown in Fig. 9A, with the τ values plotted against voltage in Fig. 9B. Compared to wild-type channels (Fig. 2), relief from the DA10 block in E224G was much slower (> 10-fold) at various voltages. In contrast, unblock was extremely fast in the D172N mutant. Thus, the effects of these mutations on unblocking kinetics paralleled their effects on blocking kinetics by DA10.

Figure 9. Unblocking kinetics of DA10 in E224G and D172N mutant channels.

A, original current recordings in the absence (ctl) and presence of 100 μM DA10 in E224G (upper panels) and D172N (lower panels). B, voltage dependence of time constants (τ) for DA10 in E224G and D172N obtained from the exponential fits to currents in A, compared to WT (from Fig. 2B).

Overall, the findings suggest that the negatively charged residues in the cytoplasmic pore (E224 and E299) not only bind polyamines to account for the surface charge reduction component of block, but also contribute to the fast subcomponent of pore block. D172, the negatively charged residue deep in the channel's transmembrane pore, is necessary for the slow subcomponent of the pore block, but does not contribute to surface charge in the cytoplasmic pore.

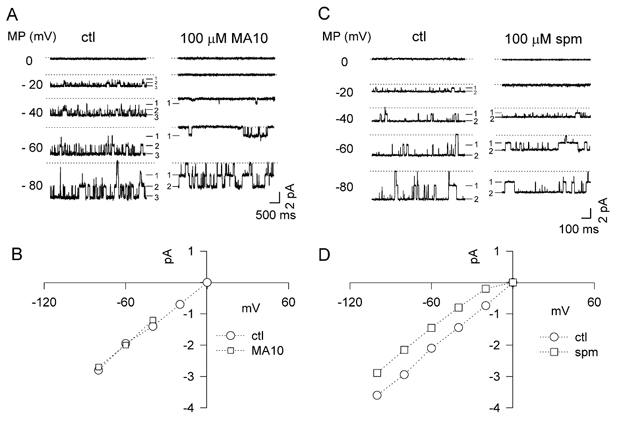

Unique blocking effect by MA10

MAs have a positive charge only at one end, unlike the DAs spermidine and spermine, both of which have positive charges at both ends of the molecule. To examine the importance of charge symmetry of the polyamine, we investigated block by MA10. Surprisingly, despite its lesser charge, MA10 at equimolar concentrations was a more potent blocker than DA10 and even spermine. However, the kinetics of both block and unblock were very slow (Fig. 10A and B). To investigate the mechanism underlying this effect, we compared the effects of MA10 with spermine on single-channel currents. As shown in Fig. 11A, MA10 blocked Kir2.1 channels by decreasing open probability in a voltage-dependent manner, inducing a long closed state. However, unlike spermine, MA10 did not significantly reduce single-channel current amplitude, indicating that MA10 (100 μM) did not induce any surface charge reduction effect. The strong decrease of the current at −80 mV (I/Ictl value of 0.5 shown in Fig. 10Ab) reflects pore block by MA10. These findings indicate that the symmetrical distribution of end charges in DA or spermine are very important with respect to their blocking mechanisms (see Discussion).

Figure 10. Effects of MA10.

A, block by 100 μM MA10: a, the original current recordings in the absence (ctl) and presence of MA10; b, the ratio of the steady-state current (I/Ictl) in the presence and absence of MA10 (○) versus Vm. The curve for 100 μM DA10 is shown for comparison (•). B, unblocking kinetics of 100 μM MA10: a, currents recorded in the absence (ctl) and presence of MA10; b, voltage dependence of the time constant for unblock of MA10 (⋄), compared to DA10 (□) and spermine (▪).

Figure 11. Comparison of MA10 and spermine on single-channel currents.

A, single-channel recordings at test potentials of 0, −20, −40, −60 and −80 mV in the absence and presence of 100 μM MA10. The dotted lines indicate the zero current level, and solid dashes show the current levels of three channels in this patch. B, the single-channel unitary amplitude I-V relationship in the absence (ctl, ○) and presence (□) of 100 μM MA10. C and D, analogous single-channel recordings and I-V plots in the absence (ctl, ○) and presence (□) of 100 μM spermine.

DISCUSSION

The strong rectification conferred by polyamines and Mg2+ is dependent upon several key negatively charged residues in the M2 segment (D172) lining the transmembrane pore and in the C-terminus (E224 and E299), which with regions of the N-terminus form the cytoplasmic pore (Nishida & MacKinnon, 2002). We recently proposed a new model for polyamine block in Kir2.1 (Xie et al. 2002), following upon the original linear reaction scheme proposed by Lopatin et al. (1994) and subsequently modified by Kubo & Murata (2001) to include more than one open state. Our model contains two open states that are partially conductive, and better accounts for the complex voltage and concentration dependence and kinetics of polyamine block at both the macroscopic and single-channel levels.

In our model, the partially conductive open states are due to positively charged polyamines such as spermine interacting with negatively charged residues (specifically E224 and E299) in the cytoplasmic pore of the channel. By reducing these negative charges, spermine decreases single-channel conductance to create a concentration-dependent reduction in macroscopic current with quasi-instantaneous kinetics and shallow voltage dependence. The second steep voltage-dependent component of block remains attributed to the movement of spermine from these non-occlusive sites to an occlusive site in the pore involving D172. In the present study, we have further analysed polyamine block by varying their length and the charge number. We postulated that rather than passively screening the negative charges without binding, if polyamines actually bind to E224 and E299 in the cytoplasmic pore, this might pre-position them to block the transmembrane pore more efficiently, providing a synergy between the surface charge reduction and pore block components. Our findings strongly support this scenario.

The surface charge reduction component of block in the cytoplasmic pore

In the present study, additional evidence supporting the surface charge reduction mechanism can be summarized as follows:

(1) When the number of charges on the blocker was reduced from 4 (spermine) or 3 (spermidine) to 2 (DA10 or DA8), while keeping the length of the blocker approximately constant, the potency of the charge reduction effect decreased progressively, as expected from surface potential theory (Hille, 2001). In addition, 100 μM MA10, with a single positive charge, had no effect on single-channel current amplitude at −80 mV, as expected since it did not significantly increase the total monovalent ion concentration (≈100 mM).

(2) We have provided further evidence that E224 and E299 are the main negatively charged residues that contribute reducible negative surface charges in the cytoplasmic pore, since their neutralization eliminated the ability of a wide variety of polyamines to induce the surface charge reduction component of block.

(3) The results show that a length of alkyl backbone ≥ 6 methylene groups is critical for inducing the surface charge reduction effect. DA2-DA5 had no surface charge reduction effect, Mg2+ had an intermediate effect and DA6 or longer were the most potent. This finding indicates that the charge-reduction potency of Mg2+ and the longer polyamines is enhanced by their binding to E224 and E299. Thus, at the same bulk concentration they achieve a higher local concentration and therefore reduce more charge than short DA or than can be accounted for by purely passive surface charge screening. As noted earlier, this is consistent with Guoy-Chapman theory (Hille, 2001), which predicts that addition of 0.1 mM divalent cations to 100 mM monovalent cations would screen a negative surface potential of −75 mV by only ≈1 %, unless binding was also present to effectively increase the local divalent concentration. Thus, the length of the alkyl backbone of the polyamine appears to be important for binding to enhance surface charge reduction. Functional and structural studies indicate that both E224 and E299 are located in the inner vestibule of the Kir2.1 channel (Lu et al. 1999b; Kubo & Murata, 2001; Nishida & MacKinnon, 2002).

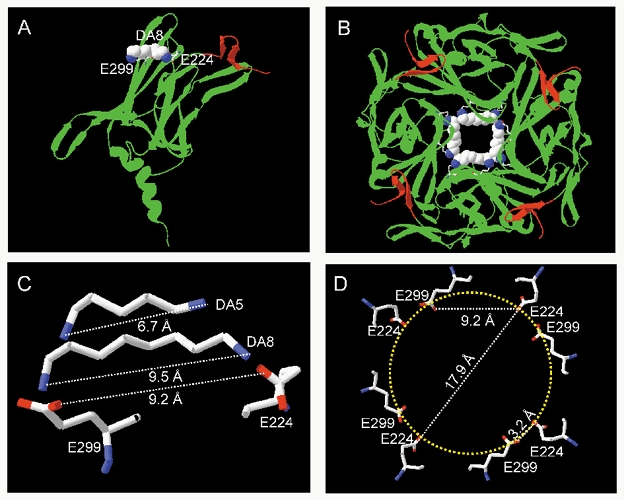

Factors such as hydrophobic interactions of the polyamine alkyl backbone with residues lining the cytoplasmic pore may also be important for stabilizing the binding of polyamines. However, we speculate that another factor for stable binding might be a requirement for ≥ 6 alkyl groups, so that the two distal positive charges on the polyamine can electrostatically interact simultaneously with E224 and E299. If E224 and E299 are separated by ≥ 6 alkyl groups, then the distance between the distal positive charges on DA2-DA5 might be too short to be effectively stabilized. Since diamines are flexible molecules, the longer alkyl chains of DA10 could bend to allow their distal positive charges to interact with E244 and E299. This idea is consistent with the recently solved structure of the cytoplasmic pore of the Kir3.1 (Nishida & MacKinnon, 2002). Using the Kir3.1 cytoplasmic pore structure as a template, Fig. 12 shows the predicted structure of the Kir2.1 cytoplasmic pore, which is formed by the N and C termini of the protein and includes the E224 and E299 positions. The original model had a resolution of 1.8 Å. Calculation of the Kir2.1 model suggest that the backbone deviates from the backbone of Kir3.1 by 0.01 Å r.m.s. The side view of a single subunit (Fig. 12A) indicates that E224 and E299 are nearly in the same horizontal plane. The top view of the tetramer looking down into the pore from the side nearest the membrane (Fig. 12B) indicates that E224 and E299 are separated by a distance of ≈ 9.2 Å, which is very close to the length of DA8 (9.5 Å, Fig. 12C). In contrast, DA5 is too short (6.7 Å) to span the distance between E224 and E299. This predicted geometry agrees remarkably well with the complete loss of surface charge reduction efficacy for diamines with five or less alkyl groups, but cannot be viewed as firm evidence, since Kir2.1 has been modelled on Kir3.1 with a resolution of 1.8 Å. Figure 12D illustrates the geometry of the pore at the level of E224 and E299, and shows that E224 on one subunit and E299 on the adjacent subunit lie within 3.2 Å, suggesting that they might cooperate functionally as a unit to stabilize the positively charged end of a polyamine molecule. Such cooperativity between negative charges on adjacent subunits may explain why DA10 retained modest surface charge reduction efficacy in E299S (Fig. 6B), as did spermine in E224G (Xie et al. 2002). In contrast, the surface charge reduction was completely abolished for all polyamines in the double mutant E224G/E299S. Mg2+ had intermediate charge reduction efficacy, yet the charges on Mg2+ are obviously too close together to span E224 and E299 on the same subunit. The close spacing of charges on Mg2+ may facilitate its stable binding to either E224 or E299 alone, accounting for its intermediate surface charge reduction efficacy compared to short diamines. Alternatively, the closer spacing of negative charges from E224 and E299 on adjacent subunits might also cooperate to stabilize Mg2+ binding.

Figure 12. Structural features of polyamine binding to Kir2.1, showing the cytoplasmic pore structure of Kir2.1 predicted from the 1.8 Å resolution Kir3.1 data.

A, ribbon diagram of a single subunit of the Kir2.1 cytoplasmic pore region, oriented with the centre of the cytoplasmic pore in front and the transmembrane pore above. N-terminus residues 44–57 are shown in red, and C-terminus residues 186–368 in green with β sheets A-H indicated by the wide ribbons. Labelled positions E224 (in βD) and E299 (in βH) line the pore, and a space-filling model of DA8 is also shown spanning E224 and E299, stabilized via the postulated charge-charge interactions. B, top view of the tetramer looking down the pore from above, with four DA8 molecules bound to the E224 and E299 residues. C, predicted intermolecular distances between the side chains of E224 and E299, compared to the lengths of DA8 and DA5. D, the geometry of the pore portion showing the predicted intramolecular distances at the level of the E224 and E299 residues. Note that E224 is very close to E299 on the adjacent subunit.

The transmembrane pore block component: voltage dependence and subcomponents with different kinetics

Pearson & Nichols (1998) hypothesized that a major determinant of the charge movement associated with block of Kir channels by long polyamines and their analogues is the sweeping out of K+ from the transmembrane pore. They suggested that polyamines block Kir channels by entering deeply into a long narrow pore, displacing K+ to the outside of the membrane, thereby moving more charge outwards and thus increasing the net charge movement associated with channel block. Our present findings support this hypothesis, since the effective valencies of pore block by spermine (δz = 5.2 ± 0.3) and DA10 (δz = 4.0 ± 0.2), as well as by spermidine (δz = 4.5 ± 0.2) and DA8 (δz = 3.6 ± 0.5), were higher than the charge number of the various polyamines. Moreover, as polyamine charge was decreased, the differences in effective valencies for block changed by less than the difference in their charge. These findings suggest that at least ≈ 2δz units are related to the K+-sweeping mechanism. Although we cannot exclude that multiple polyamines bind at the pore-blocking site simultaneously to account for the extra charges, such an explanation seems unlikely as the decrease in δz was related to the length of the alkyl chain rather than the charge number (e.g. DA6 vs. DA10). The latter observation may indicate that the shorter polyamines penetrate less deeply into the pore, sweeping out fewer K+. The higher potency of block (i.e. more negative V0.5) associated with spermine and spermidine compared to DA10 and DA8 might be due to greater local accumulation of spermine and spermidine than long DAs by the negative surface potential in the cytoplasmic pore. In contrast, the higher potency of long DAs compared to short DAs appears to involve hydrophobic interactions between the alkyl backbone and the pore lining, since unblocking rates increased dramatically as alkyl backbone length shortened (e.g. Fig. 7).

In the present experiments, we identified two subcomponents of pore block by long polyamines, with quasi-instantaneous and slow kinetics, respectively. These two subcomponents could be individually isolated by neutralizing key negatively charged residues in the channel. Specifically, in the E224G/E299S double mutant the fast, but not the slow, subcomponent of the block by 100 μM DA10 disappeared. Conversely, the slow subcomponent of both block and unblock were completely eliminated when D172 was neutralized. This observation suggests that D172 stabilizes polyamines like DA10 once they lodge in the pore. The affinity for fast pore block by spermine also decreased in D172N channels (Fig. 8C), consistent with a decrease in the on-rate of block. However, this effect was not observed with DA10, possibly because of its lesser charge. Conversely, the E224G and E224G/E299S mutations caused the fast unblock to disappear, with slow unblock becoming predominant. Thus, E224 appears to play a critical role in both accelerating polyamine access to D172 and facilitating its unblocking from the same site.

Other factors besides electrostatic interactions have also been shown to be important in modulating the kinetics of block and unblock. Previous results (Pearson et al. 1998) as well as our findings indicate that decreasing the alkyl chain length of DA or MA, without changing charge, speeds up both blocking and unblocking kinetics. This phenomenon also occurred in the E224G/E299S double mutant (Fig. 7), indicating that even in the absence of the key negative surface charges in the cytoplasmic pore, diamine length affects the kinetics of block and unblock. Although we cannot exclude other possibilities, the fast block by short DAs may reflect less (hydrophobic) interaction between the alkyl side chains of the DAs and the protein lining of the inner pore as the polyamine snakes its way towards D172, whereas this retarding effect is increased with longer polyamines.

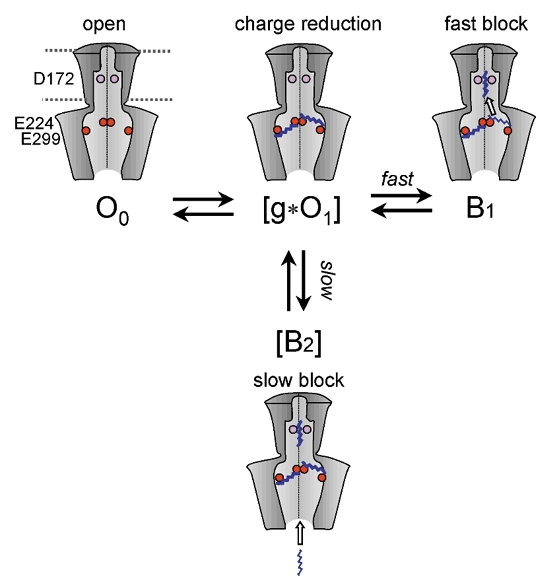

A model of polyamine block

Based on structural information from Kir channels (Doyle et al. 1998; Lu et al. 1999a,b; Cukras et al. 2002; Nishida & MacKinnon, 2002) and evidence from the present study, we propose the model shown in Fig. 13 to explain the strong synergy between surface charge reduction and pore-block components by polyamines. O0 is a full, open state of the channel and, for simplicity, [g*O1] represents all of the partially conducting open states (two were required in the previous model from Xie et al. 2002), where g is fractional conductance due to surface charge reduction. Up to four polyamine molecules might bind to the E224 and E299 residues, by spanning the circumference inside the cytoplasmic pore in a horizontal orientation. B1 represents fast pore block due to a polyamine molecule moving from a non-occlusive binding site in the cytoplasmic pore (E224/E299) to an occlusive site in the transmembrane pore involving D172. Binding of the polyamines to the E224/E299 residues serves to pre-position them so that their access to the transmembrane pore site is enhanced, thereby speeding up the kinetics of block dramatically and accounting for the fast component of pore block. [B2] represents the blocked state with slow kinetics, which we attribute to the diffusion of a free, untethered polyamine directly into the transmembrane pore-occluding site near D172. Thus, when E224 and E299 were neutralized, the slow block became the only route by which polyamines could enter the pore, and slow block dominated. Conversely, D172 appears to be essential for the polyamine to lodge stably in the transmembrane pore. When neutralized, the slow component of high-affinity block was eliminated completely and the fast component was also attenuated (Fig. 8C).

Figure 13. Schematic model of block by long diamines in Kir2.1 channels.

O0 is a fully open state of the channel and, for simplicity, [g*O1] represents partially conducting open states, where g is the fractional conductance due to surface charge reduction (see text). The movement of a pre-positioned diamine molecule tethered at E224 and/or E299 to the occlusive position in the channel pore involving D172 causes the fast component of pore block (O1→ B1). [B2] represent blocked states with slow kinetics, attributed to diffusion of free untethered diamines directly into the pore-occluding site near D172. In a complete model, a B2 state can also be accessed from the O0 state. The critical negatively charged positions are indicated by pink (D172) and red (E224 and E299) circles and polyamines as blue zigzag lines.

This model can also account for other aspects of the strong coupling between the surface charge reduction and pore block components. Just as the negative charge at D172 may attract the proximal positively charged head group of the polyamine into the pore, the distal positively charged head group may simultaneously be attracted by the negative surface charges at E224 and/or E229 sites. The latter effect facilitates exit of the polyamine from the pore-occluding site (D172) in addition to concentrating and binding polyamines locally. This can explain why unblock kinetics became slower when E224 and/or E299 were neutralized. Conversely, the unblocking kinetics of the D172N mutant were faster than that of the wild-type, because the polyamine could not be stabilized in the transmembrane pore without the charge-charge interaction with D172.

The experiments with the monoamine MA10 provide further support for this hypothetical scenario. MA10 was a more potent blocker of Kir2.1 channels than either DA10 or spermine, but had very distinctive slow kinetics (Fig. 10). We speculate that once the positive charge at the end of the MA10 molecule became bound to the transmembrane pore-blocking site near D172, the channel tended to remain blocked for a long time, since there were no other positive charges at the other end to pull it out by the electrostatic attraction to E224/E299 in the cytoplasmic pore.

Finally, this model predicts that slow block ([B2]) is dependent on bulk polyamine concentration, while fast block (B1) is dependent on local polyamine concentration. This is consistent with the original analysis by Lopatin et al. (1994), in which their data were well fitted by assuming that the shallow and steep components of block by spermine were both concentration dependent. However, they introduced an additional concentration-independent transition in their final model in order to reduce the effective valency of spermine block to less than 4. It is important to note that this concentration-independent transition was not necessary if the sweeping out of K+ from the channel pore also contributed to the effective valency, as they subsequently realized (Pearson & Nichols, 1998).

In conclusion, we have used polyamines of different lengths and charge, as well as mutagenesis, to separate various components of polyamine block in Kir2.1. Our findings indicate that in the wild-type Kir2.1, the negative charges at E224, E299 and D172 act in a concerted manner to synergistically couple the surface charge reduction and open-channel components of polyamine block. We suggest that the binding of polyamines to E224 and E299 pre-positions them in the cytoplasmic pore in a manner that directly facilitates their entry to and exit from a pore-occluding site involving D172 in the transmembrane pore.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr L. Y. Jan for providing the Kir2.1 clone, Dr R. MacKinnon for providing the protein coordinates of the tetramer of the Kir3.1 cytoplasmic pore and Dr Y. Lu for technical support. This work was supported by NIH R37 HL60025 (to J.N.W.), by American Heart Association, Western States Affiliate Postdoctoral Research Fellowship and Beginning Grant-in-Aid (to L.H.X.), and the Kawata and Laubisch Endowments.

REFERENCES

- Cukras CA, Jeliazkova I, Nichols CG. Structural and functional determinants of conserved lipid interaction domains of inward rectifying kir6. 2 channels. J Gen Physiol. 2002;119:581–591. doi: 10.1085/jgp.20028562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doupnik CA, Davidson N, Lester HA. The inward rectifier potassium channel family. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 1995;5:268–277. doi: 10.1016/0959-4388(95)80038-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doyle DA, Morais Cabral J, Pfuetzner RA, Kuo A, Gulbis JM, Cohen SL, Chait BT, MacKinnon R. The structure of the potassium channel: molecular basis of K+ conduction and selectivity. Science. 1998;280:69–77. doi: 10.1126/science.280.5360.69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fakler B, Brandle U, Glowatzki E, Weidemann S, Zenner HP, Ruppersberg JP. Strong voltage-dependent inward rectification of inward rectifier K+ channels is caused by intracellular spermine. Cell. 1995;80:149–154. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90459-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ficker E, Taglialatela M, Wible BA, Henley CM, Brown AM. Spermine and spermidine as gating molecules for inward rectifier K+ channels. Science. 1994;266:1068–1072. doi: 10.1126/science.7973666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujiwara Y, Kubo Y. Ser165 in the second transmembrane region of the Kir2. 1 channel determines its susceptibility to blockade by intracellular Mg2+ J Gen Physiol. 2002;120:677–693. doi: 10.1085/jgp.20028663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guex N, Peitsch MC. SWISS-MODEL and the Swiss-PdbViewer: an environment for comparative protein modeling. Electrophoresis. 1997;18:2714–2723. doi: 10.1002/elps.1150181505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hille B. Ionic Channels of Excitable Membranes. 3. Sunderland: Sinauer Associates; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Kubo Y, Baldwin TJ, Jan YN, Jan LY. Primary structure and functional expression of a mouse inward rectifier potassium channel. Nature. 1993;362:127–133. doi: 10.1038/362127a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kubo Y, Murata Y. Control of rectification and permeation by two distinct sites after the second transmembrane region in Kir2. 1 K+ channel. J Physiol. 2001;531:645–660. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2001.0645h.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee J-K, John SA, Weiss JN. Novel gating mechanism of polyamine block in the strong inward rectifier K channel Kir2. 1. J Gen Physiol. 1999;113:555–564. doi: 10.1085/jgp.113.4.555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopatin AN, Makhina EN, Nichols CG. Potassium channel block by cytoplasmic polyamines as the mechanism of intrinsic rectification. Nature. 1994;372:366–369. doi: 10.1038/372366a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu Z, MacKinnon R. Electrostatic tuning of Mg2+ affinity in an inward-rectifier K+ channel. Nature. 1994;371:243–246. doi: 10.1038/371243a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu T, Nguyen B, Zhang X, Yang J. Architecture of a K+ channel inner pore revealed by stoichiometric covalent modification. Neuron. 1999a;22:571–580. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80711-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu T, Zhu YG, Yang J. Cytoplasmic amino and carboxyl domains form a wide intracellular vestibule in an inwardly rectifying potassium channel. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999b;96:9926–9931. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.17.9926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuda H, Saigusa A, Irisawa H. Ohmic conductance through the inwardly rectifying K channel and blocking by internal Mg2+ Nature. 1987;325:156–159. doi: 10.1038/325156a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishida M, MacKinnon R. Structure basis of inward rectification: Cytoplasmic pore of the G protein-gated inward rectifier GIRK1 at 1. 8 Å resolution. Cell. 2002;111:957–965. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)01227-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearson WL, Nichols CG. Block of the Kir2. 1 channel pore by alkylamine analogues of endogenous polyamines. J Gen Physiol. 1998;112:351–363. doi: 10.1085/jgp.112.3.351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shieh RC, John SA, Lee JK, Weiss JN. Inward rectification of the IRK1 channel expressed in Xenopus oocytes: effects of intracellular pH reveal an intrinsic gating mechanism. J Physiol. 1996;494:363–376. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1996.sp021498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stanfield PR, Davies NW, Shelton PA, Sutcliffe MJ, Khan IA, Brammar WJ, Conley EC. A single aspartate residue is involved in both intrinsic gating and blockage by Mg2+ of the inward rectifier, IRK1. J Physiol. 1994;478:1–6. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1994.sp020225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taglialatela M, Ficker E, Wible BA, Brown AM. C-terminus determinants for Mg2+ and polyamine block of the inward rectifier K+ channel IRK1. EMBO J. 1995;14:5532–5541. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1995.tb00240.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vandenberg CA. Inward rectification of a potassium channel in cardiac ventricular cells depends on internal magnesium ions. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1987;84:2560–2564. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.8.2560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wible BA, Taglialatela M, Ficker E, Brown AM. Gating of inwardly rectifying K+ channels localized to a single negatively charged residue. Nature. 1994;371:246–249. doi: 10.1038/371246a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie LH, John SA, Weiss JN. Spermine block of the strong inward rectifier potassium channel Kir2. 1: dual roles of surface charge screening and pore block. J Gen Physiol. 2002;120:53–66. doi: 10.1085/jgp.20028576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang J, Jan YN, Jan LY. Control of rectification and permeation by residues in two distinct domains in an inward rectifier K+ channel. Neuron. 1995;14:1047–1054. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(95)90343-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]