Abstract

The pancreatic β-cell type of ATP-sensitive potassium (KATP) channel (Kir6.2/SUR1) is inhibited by intracellular ATP and ADP, which bind to the Kir6.2 subunit, and is activated by Mg-nucleotide interaction with the regulatory sulphonylurea receptor subunits (SUR1). The nicotinamide adenine dinucleotides NAD and NADP consist of an ADP molecule with a ribose group and a nicotinamide moiety attached to the terminal phosphate. Both these molecules block native KATP channels in pancreatic β-cells at concentrations above 500 μM, and activate them at lower concentrations. We therefore investigated whether NAD and NADP interact with both Kir6.2 and SUR1 subunits of the KATP channel by comparing the potency of these agents on recombinant Kir6.2ΔC and Kir6.2/SUR1 channels expressed in Xenopus oocytes. Our results show that, at physiological concentrations, NAD and NADP interact with the nucleotide inhibitory site of Kir6.2 to inhibit Kir6.2/SUR1 currents. They may therefore contribute to the resting level of channel inhibition in the intact cell. Importantly, our data also reveal that this interaction is dependent on the presence of SUR1, which may act by increasing the width of the nucleotide-binding pocket of Kir6.2.

ATP sensitive potassium (KATP) channels play a major role in regulating the membrane potential of pancreatic β-cells, and thereby insulin release (Ashcroft & Rorsman, 1989). In the absence of nutrients KATP channels are open, maintaining the resting potential at around −70 mV. Channel closure in response to increased glucose metabolism closes KATP channels (Ashcroft et al. 1984), producing a membrane depolarization that activates voltage-gated Ca2+ channels, Ca2+ influx and insulin release. It is generally accepted that changes in adenine nucleotides constitute the main physiological mechanism by which β-cell metabolism regulates KATP channel activity. Many other KATP channel modulators have also been identified, which contribute to the background level of activity in the cell. Among these are lipids, such as PIP2 (Fan & Makielski, 1997; Shyng & Nichols, 1998; Baukrowitz et al. 1998), and the nicotine adenine dinucleotides NAD(P) and NAD(P)H (Harding et al. 1997; Dunne et al. 1988). It has also been postulated that changes in the level of these compounds may be involved in the physiological regulation of channel activity. In this respect, the nicotine adenine dinucleotides are of particular interest since their concentrations change with glucose metabolism (Patterson et al. 2000; Rocheleau et al. 2002).

KATP channels comprise four pore-forming Kir6.2 subunits and four regulatory sulphonylurea receptor (SUR1) subunits. Adenine nucleotides inhibit the KATP channel via a specific interaction with Kir6.2 (Tucker et al. 1997; Tanabe et al. 1999). In addition, Mg-nucleotides such as MgATP, MgADP, MgGTP and MgGDP, stimulate channel activity by binding to the nucleotide binding domains (NBDs) of the SUR (Gribble et al. 1997b, 1998; Shyng et al. 1997; Trapp et al. 1997). In the presence of Mg2+ and nucleotides, therefore, the balance between these stimulatory and inhibitory effects will determine channel activity. At a concentration of 100 μM, MgATP blocks the KATP channel whereas MgADP activates it, because inhibition dominates in the former case and activation in the latter.

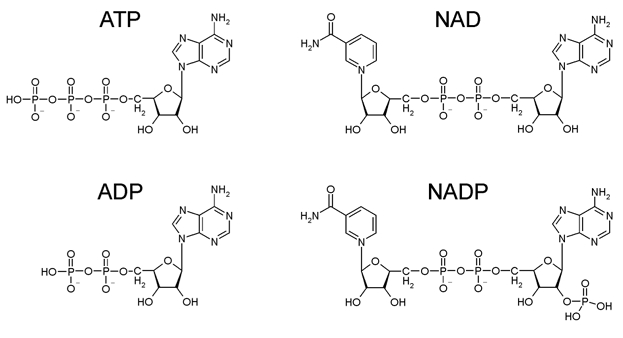

Earlier studies have shown that in the presence of 1 mM Mg2+, NAD(P) and NAD(P)H block native KATP channels in pancreatic β-cells at concentrations above 500 μM, but stimulate channel activity at lower concentrations (Harding et al. 1997; Dunne et al. 1988). Structurally, NAD consists of an ADP molecule with a ribose group and a nicotinamide moiety attached to the terminal phosphate (Fig. 1). We therefore investigated whether, like the parent ADP molecule, NAD(P) and NAD(P)H interact with both Kir6.2 and SUR subunits of the KATP channel.

Figure 1. Chemical structures of ATP, ADP, NAD and NADP.

METHODS

Molecular biology

Mouse Kir6.2 (Genbank D50581; Inagaki et al. 1995; Sakura et al. 1995) and rat SUR1 (Genbank L40624; Aguilar-Bryan et al. 1995) cDNAs were cloned into the pBF vector. A truncated form of Kir6.2 (Kir6.2ΔC), which lacks the C-terminal 36 amino acids and forms functional channels in the absence of SUR, was prepared as described previously (Tucker et al. 1997). Mutagenesis of the individual amino acids was performed using the altered sites II System (Promega, Madison, WI, USA). Capped mRNA was prepared using the mMESSAGE mMACHINE large scale in vitro transcription kit (Ambion, Austin, TX, USA) or the mRNA capping kit (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA, USA), as previously described (Gribble et al. 1997a).

Oocyte collection

Female Xenopus laevis were anaesthetised with MS222 (2 g l−1 added to the water). One ovary was removed via a mini-laparotomy, the incision was sutured and the animal was allowed to recover. Once the wound had completely healed, the second ovary was removed in a similar operation and the animal was then killed by decapitation whilst under anaesthesia. Immature stage V-VI oocytes were incubated for 60 min with 1.0 mg ml−1 collagenase (Sigma, type V) and manually defolliculated. Oocytes were either injected with ≈1 ng Kir6.2ΔC36 mRNA or coinjected with ≈0.1 ng Kir6.2 mRNA and ≈2 ng of mRNA encoding wild-type or mutated SUR. The final injection volume was 50 nl oocyte−1. Isolated oocytes were maintained in Barth's solution and studied 1–7 days after injection (Gribble et al. 1997a). All procedures used conformed with the University of Oxford ethical committee guidelines and the UK Animals (Scientific Procedures) Act 1986.

Electrophysiology

Patch pipettes were pulled from thick-walled borosilicate glass and had resistances of 250–500 kΩ when filled with pipette solution. Macroscopic currents were recorded from giant excised inside-out patches at a holding potential of 0 mV and at 20–24 °C (Gribble et al. 1997a). Currents were evoked by repetitive 3 s voltage ramps from −110 to +100 mV and recorded using an EPC7 patch-clamp amplifier (List Electronik, Darmstadt, Germany). They were filtered at 0.2 kHz, digitised at 0.4 kHz using a Digidata 1200 Interface and analysed using pCLAMP software (Axon Instruments Inc., Foster City, CA, USA).

The pipette (external) solution contained (mM): 140 KCl, 1.2 MgCl2, 2.6 CaCl2, 10 Hepes (pH 7.4 with KOH). The intracellular (bath) solution contained (mM): 110 KCl, 2 MgCl2, 1 CaCl2, 10 EGTA, 10 Hepes (pH 7.2 with KOH; final [K+] ≈140 mM). The Mg2+-free solution contained (mM): 110 KCl, 2.6 CaCl2, 10 EDTA, 10 Hepes (pH 7.2 with KOH; final [K+] ≈140 mM). Solutions containing nucleotides were made up fresh each day and the pH subsequently readjusted if required. Rapid exchange of solutions was achieved by positioning the patch in the mouth of one of a series of adjacent inflow pipes placed in the bath.

Data analysis

The slope conductance was measured by fitting a straight line to the current–voltage relation between −20 and −100 mV. Conductance was measured from an average of five consecutive ramps in each solution. Responses to nucleotides were expressed relative to the conductance measured in control solution without added drugs or nucleotides. Concentration-response curves were constructed by expressing the conductance in the presence of drug (G) as a fraction of that in control solution (Gc). The data were fitted to a modified form of the Hill equation:

| (1) |

where [nucleotide] is the concentration of nucleotide, IC50 is the nucleotide concentration at which inhibition is half-maximal and nH is the Hill coefficient. All data are presented as means ± 1 s.e.m. Statistical significance was tested using Student's t test.

RESULTS

To distinguish the relative contributions of Kir6.2 and SUR1 to the regulation of KATP channel activity by nicotine adenine dinucleotides, we compared the effect of these nucleotides on channels consisting of Kir6.2 alone, or of Kir6.2 in combination with SUR1. Although neither KATP channel subunit traffics to the surface membrane in the absence of its partner, removal of an endoplasmic reticulum retention signal from the C-terminus of Kir6.2 by truncation of the protein (Kir6.2ΔC) enables the surface expression of this subunit in the absence of SUR (Tucker et al. 1997; Zerangue et al. 1999). We first explored the inhibitory effect of NAD and NADP. For these experiments we used Mg2+-free solutions, in order to preclude nucleotide interaction with the NBDs of SUR1.

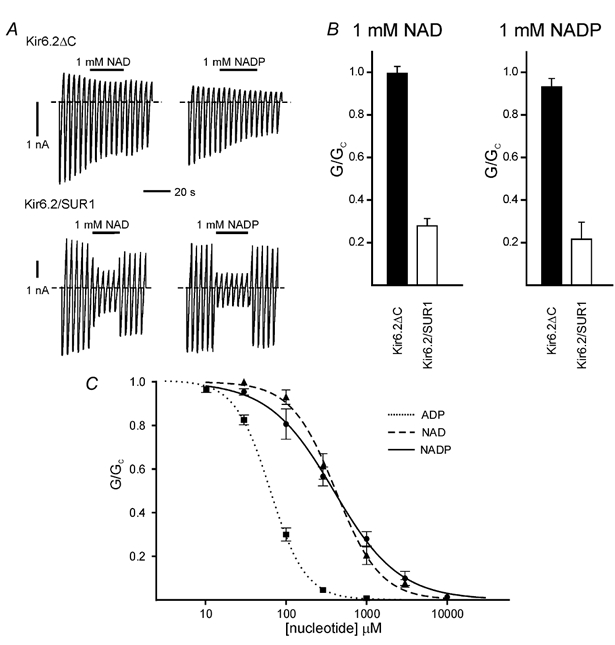

Figure 2 shows that (in Mg2+-free solution) neither 1 mM NAD nor 1 mM NADP produce measurable block of Kir6.2ΔC channels, but that both nucleotides substantially inhibit Kir6.2/SUR1 channels: by 75 ± 5.5 % (n = 13) and 68 ± 4.1 % (n = 11) for 1 mM NAD and NADP, respectively. The concentration-response relationships for Kir6.2/SUR1 channels are shown in Fig. 2C. For NAD, the block is well fitted by the Hill equation (eqn (1)) with an IC50 of 392 ± 13 μM and a Hill coefficient of 1.1 (n = 5). Similar results were found for NADP (IC50 418 ± 24 μM, Hill coefficient 1.6; n = 6). In contrast, ADP was a much more potent inhibitor, the IC50 being 64 ± 1 μM (n = 6). Neither NAD nor NADP produced measurable inhibition of Kir6.2ΔC currents, even at concentrations as high as 1 mM (see Fig. 2A and B). The IC50 for inhibition of Kir6.2ΔC by ADP is 260 μM, around 4-fold less than that for Kir6.2/SUR1 (Tucker et al. 1998). Assuming a Hill coefficient of 1, a 4-fold decrease in sensitivity to NAD would result in an IC50 of 1.6 mM, which we should be able to measure easily.

Figure 2. Effects of NAD and NADP on Kir6.2ΔC and Kir6.2/SUR1 currents.

A, macroscopic currents recorded from inside-out patches in response to a series of voltage ramps from −110 to +100 mV from oocytes expressing either Kir6.2ΔC alone (above) or Kir6.2 plus SUR1 (below). NAD (1 mM) or NADP (1 mM) was added as indicated by the horizontal bars. The dashed line indicates the zero current potential. The solution did not contain Mg2+. B, mean macroscopic slope conductance (G) in the presence of either 1 mM NAD or 1 mM NADP expressed as a fraction of the mean of that measured in nucleotide-free solution before and after nucleotide application (Gc), for Kir6.2ΔC or Kir6.2/SUR1 as indicated. Mg2+-free solution. C, concentration–response relationships for ADP (dotted line, ▪; n = 6), NAD (dashed line, ▴; n = 5) and NADP (continuous line, •; n = 6) for Kir6.2/SUR1 KATP currents in the absence of Mg2+. The macroscopic conductance in the presence of nucleotide (G) is expressed as a fraction of the mean of that measured in nucleotide-free solution before and after nucleotide application (Gc). The lines are the best fit to eqn (1); (Methods): ADP: IC50 = 64 ± 1 μM, nH = 1.95 ± 0.06; NAD: IC50 = 392 ± 13 μM, nH = 1.07 ± 0.03; and NADP: 418 ± 24 μM, nH = 1.57 ± 0.12.

There are two possible explanations for the dramatic difference in the sensitivity of Kir6.2/SUR1 and Kir6.2ΔC to nicotinamide adenine dinucleotides. Firstly, NAD may inhibit the KATP channel by interaction with SUR1. Secondly, the presence of SUR1 may facilitate the interaction of NAD with the nucleotide inhibitory site of Kir6.2. Although the stimulation of channel activity mediated by interaction of nucleotides such as ADP with SUR is known to require Mg2+, 8-azido-ATP-binding to NBD1 is not Mg2+ dependent (Ueda et al. 1999). It has also been proposed that nucleotides may inhibit the KATP channel via SUR in certain phases of the catalytic cycle of the ABC transporter (Zingman et al. 2001).

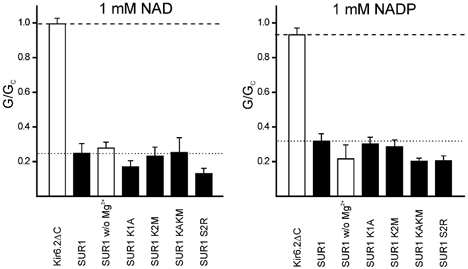

To determine whether NAD blocks KATP channels by interaction with Kir6.2 or with SUR1, we tested the effect of mutating the Walker A (WA) lysine in NBD1 (K1A) or NBD2 (K2M) of SUR1. These mutations have been shown to abolish MgADP activation of Kir6.2/SUR1 (Gribble et al. 1997b; Shyng et al. 1997). They also abolish Mg2+-independent binding of 8-azido-ATP to NBD1, and Mg2+-dependent ADP binding to NBD2, respectively (Ueda et al. 1999). As Fig. 3 shows, the K1A and K2M mutations did not alter NAD or NADP inhibition, whether tested individually or together. Mutation of S2R, which abolishes the link between nucleotide binding and channel activation (Matsuo et al. 2002), was also without effect (Fig. 3). These results suggest that neither NAD, nor NADP, mediate channel inhibition via interaction with the NBDs of SUR1.

Figure 3. Effects of NAD and NADP on wild-type and mutant KATP channels.

Mean macroscopic slope conductance (G) in the presence of either 1 mM NAD (left) or 1 mM NADP (right) expressed as a fraction of the mean of that measured in nucleotide-free solution before and after nucleotide application (Gc), for Kir6.2ΔC, and for Kir6.2 co-expressed with wild-type or mutant SUR1, as indicated. The dashed and dotted lines indicate the extent of inhibition of Kir6.2ΔC and Kir6.2/SUR1, respectively. Open bars, Mg2+-free solution; filled bars: Mg2+-containing solution.

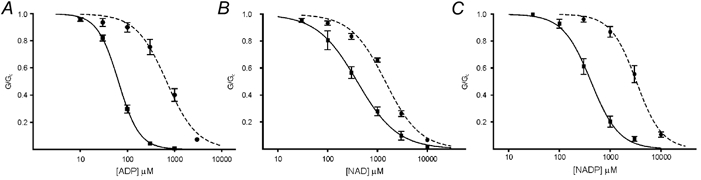

To determine if NAD- and NADP-induced inhibition of Kir6.2/SUR1 is mediated by interaction with Kir6.2, or with a site on SUR1 distinct from the NBDs, we co-expressed SUR1 with an ATP-insensitive mutant of Kir6.2, Kir6.2K185Q (Tucker et al. 1997, 1998). The concentration-response relations for inhibition of Kir6.2/SUR1 and Kir6.2K185Q/SUR1 channels by ADP, NAD and NADP are compared in Fig. 4. It is apparent that the IC50 of all three nucleotides is increased by the K185Q mutation. This indicates that inhibition of Kir6.2/SUR1 currents by NAD and NADP, like that of ADP, is mediated via the nucleotide-binding site on Kir6.2.

Figure 4. Effects of ADP, NAD and NADP on Kir6.2/SUR1 and Kir6.2K185Q/SUR1 currents.

Concentration–response relationships for ADP (A), NAD (B) and NADP (C) for Kir6.2/SUR1 (▪, n = 5–15) or Kir6.2K185Q/SUR1 (▪, n = 5–15) KATP currents, in the absence of Mg2+. The macroscopic conductance in the presence of nucleotide (G) is expressed as a fraction of the mean of that measured in nucleotide-free solution before and after nucleotide application (Gc). The lines are the best fit to eqn (1); (Methods): A, ADP; Kir6.2/SUR1: IC50 = 64 ± 1 μM, nH = 1.95 ± 0.06; and Kir6.2K185Q/SUR1: IC50 = 677 ± 73 μM, nH = 1.34 ± 0.17. B, NAD; Kir6.2/SUR1: IC50 = 392 ± 13 μM, nH = 1.07 ± 0.03; and Kir6.2K185Q/SUR1: IC50 = 1.44 ± 0.15 mM, nH = 1.25 ± 0.15. C, NADP; Kir6.2/SUR1: IC50 = 418 ± 24 μM, nH = 1.57 ± 0.12; and Kir6.2K185Q/SUR1: IC50 = 3.27 ± 0.18 mM, nH = 1.72 ± 0.15.

It is clear that both NAD and NADP are markedly less effective at blocking Kir6.2ΔC and Kir6.2/SUR1 channels than either ADP or ATP. This could indicate that NAD and NADP show a markedly reduced binding affinity, or that they bind with similar affinity but fail to transduce binding into channel closure. To distinguish between these possibilities, we tested whether the inhibitory potency of ATP was affected by the presence of NAD or NADP. As shown in Fig. 5, 0.1 mM ATP blocked Kir6.2ΔC currents to a similar extent in both the absence and presence of 1 mM NAD (or 1 mM NADP). This suggests that NAD and NADP bind less tightly than ATP to Kir6.2.

Figure 5. Effect of ATP in the presence of NAD and NADP on Kir6.2ΔC currents.

Mean macroscopic slope conductance (G) in the presence of 0.1 mM ATP alone (open bar) or 0.1 mM ATP plus either 1 mM NAD (grey bar) or 1 mM NADP (filled bar). Conductance is expressed as a fraction of the mean of that measured in nucleotide-free solution before and after nucleotide application (Gc). The dashed line indicates the slope conductance in nucleotide-free solution and the number of patches is given above the bars.

Finally, we tested the effect of nicotine adenine dinucleotides in the presence of Mg2+ to ascertain if they interact with the NBDs of SUR to stimulate channel activity. Although previous studies have reported that in the presence of Mg2+ low concentrations of NAD and NADP can activate native β-cell KATP channels (Dunne et al. 1988), we did not observe activation of either Kir6.2/SUR1 or Kir6.2ΔC channels by either 0.1 mM (n = 4) or 1 mM (n = 13) NAD, or by 0.1 mM (n = 4) or 1 mM (n = 11) NADP, in the presence of 2 mM Mg2+.

DISCUSSION

Our results demonstrate that nicotine adenine dinucleotides inhibit Kir6.2/SUR1 channels by interaction with Kir6.2. They also show that neither NAD nor NADP interact with the NBDs of SUR1 to produce channel activation (or inhibition). It is noteworthy that SUR1 markedly enhances the potency of the inhibitory site on Kir6.2 for both NAD and NADP. This suggests that SUR1 may modify the nucleotide-binding pocket of Kir6.2 so that it can accept larger groups attached to the phosphate tail. Structurally, NAD consists of an ADP molecule with a ribose group and a nicotinamide moiety attached to the terminal phosphate (Fig. 1). It is possible that these additions make the NAD molecule too bulky to fit in the nucleotide-binding pocket of Kir6.2ΔC, but that the presence of SUR modifies the binding pocket so that it is able to accommodate the nucleotide. SUR also increases the sensitivity of Kir6.2 to nucleotides such as ATP and ADP, by about 10-fold (Tucker et al. 1998). However, the ability of SUR to enhance NAD(P) sensitivity appears to be much greater as we were unable to measure inhibition of Kir6.2ΔC by these nucleotides and a 10-fold difference would have been easily detectable.

Comparison with native channels

Although the concentration-response curve for native Kir6.2/SUR1 channels has not been measured, earlier studies have shown that 500 μM NAD, NADP or NADPH decrease the activity of native KATP β-cell channels by 38–44 % (Dunne et al. 1988). These values are in agreement with our data. Although lower concentrations of MgNAD (50–100 μM) have been reported to increase the activity of native KATP channels, this was not observed in our studies. One explanation for this difference is that KATP channel activity can be modulated by an NAD(P)-binding protein that is retained in patches excised from pancreatic β-cells but which is not present in oocytes

Physiological significance

Both NAD and NADP are found in the cytoplasm of pancreatic β-cells. In the resting cell, the cytosolic concentrations are 200–350 μM for NAD and 30–100 μM for NADP (NADH and NADPH are similar). Our data indicate that these concentrations will produce a small contribution to the inhibition of KATP channels in the intact cell. Glucose metabolism induces changes in the NAD/NADH ratio but is not thought to change the total concentration of nicotine adenine dinucleotides. Thus although the glucose-induced increase in NADH precedes KATP channel closure (Pralong et al. 1990; Duchen et al. 1993; Rocheleau et al. 2002) it is not likely to serve as a metabolic regulator of the KATP channel. The fact that the complex I inhibitor rotenone, which raises cytosolic NADH levels, activates rather than inhibits KATP channels, is also consistent with this view (Roper & Ashcroft, 1995).

Acknowledgments

We thank the Wellcome Trust for support. M.D. was the Robert Turner Visiting Scholar. F.M.A. is the Royal Society GlaxoSmithKline Research Professor. We thank Dr Timothy Ryder for preparing the Kir6.2 point mutations.

REFERENCES

- Aguilar-Bryan L, Nichols CG, Wechsler SW, Clement JP, IV, Boyd AE, III, Gonzalez G, Herrera-Sosa H, Nguy K, Bryan J, Nelson DA. Cloning of the beta cell high-affinity sulfonylurea receptor: a regulator of insulin secretion. Science. 1995;268:423–426. doi: 10.1126/science.7716547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashcroft FM, Harrison DE, Ashcroft SJ. Glucose induces closure of single potassium channels in isolated rat pancreatic beta-cells. Nature. 1984;312:446–448. doi: 10.1038/312446a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashcroft FM, Rorsman P. Electrophysiology of the pancreatic beta-cell. Prog Biophys Mol Biol. 1989;54:87–143. doi: 10.1016/0079-6107(89)90013-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baukrowitz T, Schulte U, Oliver D, Herlitze S, Krauter T, Tucker SJ, Ruppersberg JP, Fakler B. PIP2 and PIP as determinants for ATP inhibition of KATP channels. Science. 1998;282:1141–1144. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5391.1141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duchen MR, Smith PA, Ashcroft FM. Substrate-dependent changes in mitochondrial function, intracellular free calcium concentration and membrane channels in pancreatic beta-cells. Biochem J. 1993;294:35–42. doi: 10.1042/bj2940035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunne MJ, Findlay I, Petersen OH. Effects of pyridine nucleotides on the gating of ATP-sensitive potassium channels in insulin-secreting cells. J Membr Biol. 1988;102:205–216. doi: 10.1007/BF01925714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan Z, Makielski JC. Anionic phospholipids activate ATP-sensitive potassium channels. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:5388–5395. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.9.5388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gribble FM, Ashfield R, Ammala C, Ashcroft FM. Properties of cloned ATP-sensitive K+ currents expressed in Xenopus oocytes. J Physiol. 1997a;498:87–98. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1997.sp021843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gribble FM, Tucker SJ, Ashcroft FM. The essential role of the Walker A motifs of SUR1 in K-ATP channel activation by Mg-ADP and diazoxide. EMBO J. 1997b;16:1145–1152. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.6.1145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gribble FM, Tucker SJ, Haug T, Ashcroft FM. MgATP activates the beta cell KATP channel by interaction with its SUR1 subunit. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:7185–7190. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.12.7185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harding EA, Kane C, James RF, London NJ, Dunne MJ. Modulation of three types of potassium selective channels by NAD and other pyridine nucleotides in human pancreatic beta-cells. NAD and K+ channels in human beta-cells. Adv Exp Med Biol. 1997;426:43–50. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4899-1819-2_6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inagaki N, Gonoi T, Clement JP, IV, Namba N, Inazawa J, Gonzalez G, Aguilar-Bryan L, Seino S, Bryan J. Reconstitution of IKATP: an inward rectifier subunit plus the sulfonylurea receptor. Science. 1995;270:1166–1170. doi: 10.1126/science.270.5239.1166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuo M, Dabrowski M, Ueda K, Ashcroft FM. Mutations in the linker domain of NBD2 of SUR inhibit transduction but not nucleotide binding. EMBO J. 2002;21:4250–4258. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdf419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patterson GH, Knobel SM, Arkhammar P, Thastrup O, Piston DW. Separation of the glucose-stimulated cytoplasmic and mitochondrial NAD(P)H responses in pancreatic islet beta cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:5203–5207. doi: 10.1073/pnas.090098797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pralong WF, Bartley C, Wollheim CB. Single islet beta-cell stimulation by nutrients: relationship between pyridine nucleotides, cytosolic Ca2+ and secretion. EMBO J. 1990;9:53–60. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1990.tb08079.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rocheleau JV, Head WS, Nicholson WE, Powers AC, Piston DW. Pancreatic islet beta-cells transiently metabolize pyruvate. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:30914–30920. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M202314200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roper J, Ashcroft FM. Metabolic inhibition and low internal ATP activate K-ATP channels in rat dopaminergic substantia nigra neurones. Pflugers Arch. 1995;430:44–54. doi: 10.1007/BF00373838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakura H, Ammala C, Smith PA, Gribble FM, Ashcroft FM. Cloning and functional expression of the cDNA encoding a novel ATP-sensitive potassium channel subunit expressed in pancreatic beta-cells, brain, heart and skeletal muscle. FEBS Lett. 1995;377:338–344. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(95)01369-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shyng S, Ferrigni T, Nichols CG. Regulation of KATP channel activity by diazoxide and MgADP. Distinct functions of the two nucleotide binding folds of the sulfonylurea receptor. J Gen Physiol. 1997;110:643–654. doi: 10.1085/jgp.110.6.643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shyng SL, Nichols CG. Membrane phospholipid control of nucleotide sensitivity of KATP channels. Science. 1998;282:1138–1141. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5391.1138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trapp S, Tucker SJ, Ashcroft FM. Activation and inhibition of K-ATP currents by guanine nucleotides is mediated by different channel subunits. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94:8872–8877. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.16.8872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanabe K, Tucker SJ, Matsuo M, Proks P, Ashcroft FM, Seino S, Amachi T, Ueda K. Direct photoaffinity labeling of the Kir6. 2 subunit of the ATP-sensitive K+ channel by 8-azido-ATP. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:3931–3933. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.7.3931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tucker SJ, Gribble FM, Proks P, Trapp S, Ryder TJ, Haug T, Reimann F, Ashcroft FM. Molecular determinants of KATP channel inhibition by ATP. EMBO J. 1998;17:3290–3296. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.12.3290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tucker SJ, Gribble FM, Zhao C, Trapp S, Ashcroft FM. Truncation of Kir6. 2 produces ATP-sensitive K+ channels in the absence of the sulphonylurea receptor. Nature. 1997;387:179–183. doi: 10.1038/387179a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ueda K, Komine J, Matsuo M, Seino S, Amachi T. Cooperative binding of ATP and MgADP in the sulfonylurea receptor is modulated by glibenclamide. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96:1268–1272. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.4.1268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zerangue N, Schwappach B, Jan YN, Jan LY. A new ER trafficking signal regulates the subunit stoichiometry of plasma membrane K(ATP) channels. Neuron. 1999;22:537–548. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80708-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zingman LV, Alekseev AE, Bienengraeber M, Hodgson D, Karger AB, Dzeja PP, Terzic A. Signaling in channel/enzyme multimers: ATPase transitions in SUR module gate ATP-sensitive K+ conductance. Neuron. 2001;31:233–245. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(01)00356-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]