Abstract

During a limited period of early neuronal development, GABA is depolarizing and elevates [Ca2+]i, which mediates the trophic action of GABA in neuronal maturation. We tested the attractive hypothesis that GABA itself promotes the developmental change of its response from depolarizing to hyperpolarizing (Ganguly et al. 2001). In cultured midbrain neurons we found that the GABA response changed from depolarizing to hyperpolarizing, although GABAA receptors had been blocked throughout development. In immature neurons prolonged exposure of the cells to nanomolar concentrations of GABA or brief repetitive applications of GABA strongly diminished the elevation of [Ca2+]i by GABA. As revealed by gramicidin perforated-patch recording, reduced [Ca2+]i responses were due to a diminished driving force for Cl−. This suggests that immature neurons do not have an efficient inward transport that can compensate the loss of cytosolic Cl− resulting from sustained GABAA receptor activation by ambient GABA. Transient increases in external K+, which can induce voltage-dependent Cl− entry, restored GABA-induced [Ca2+]i elevations. In mature neurons, GABA reduced [Ca2+]i provided that background [Ca2+]i was elevated by the application of an L-type Ca2+ channel agonist. This was probably due to a hyperpolarization of the membrane by Cl− currents. K+-Cl− cotransport maintained the gradient for hyperpolarizing Cl− currents. We conclude that in immature midbrain neurons an inward Cl− transport is not effective although the GABA response is depolarizing. Further, GABA itself is not required for the developmental switch of GABAergic responses from depolarizing to hyperpolarizing in cultured midbrain neurons.

Activation of GABAA or glycine receptors, which are anion-selective channels (Bormann et al. 1987), results in a hyperpolarization of the membrane in most mature central neurons. The direction of the underlying Cl− current depends on an active regulation of cytosolic Cl− ([Cl−]i) (Misgeld et al. 1986), which is accomplished by KCC2 (Rivera et al. 1999), a neuron-specific K+-Cl− cotransporter (Payne et al. 1996; Hübner et al. 2001b). Therefore, GABA and glycine are best known as inhibitory neurotransmitters, but they may excite neurons during development (Ben-Ari et al. 1989; Garaschuk et al. 1998). In vitro studies revealed that GABA induces Ca2+ influx in immature neurons, which requires the existence of a driving force for a depolarizing Cl− current. Inward Cl− transport by Na+- K+-2Cl− cotransport (Plotkin et al. 1997; Kakazu et al. 1999; Sung et al. 2000; Vardi et al. 2000; Jang et al. 2001) and/or HCO3−-Cl− exchange (Kobayashi et al. 1994; Rohrbough & Spitzer, 1996) have been suggested as the mechanisms underlying the depolarizing GABA response of immature neurons. The Ca2+ influx in response to GABA disappears with maturation of most neurons (Yuste & Katz, 1991; Leinekugel et al. 1995; LoTurco et al. 1995; Chen et al. 1996; Eilers et al. 2001). The change is accompanied by a progressive [Cl−]i depletion (Obrietan & van den Pol, 1995; Li et al. 1998; Ganguly et al. 2001). Developmental upregulation of KCC2 results in hyperpolarizing inhibition of hippocampal neurons (Rivera et al. 1999). Some mature neurons may, however, also maintain depolarizing responses to GABA throughout their life. An example is provided by dorsal root ganglion cells in which the Cl− gradient for depolarizing currents is sustained by Na+-K+-2Cl− cotransport (Sung et al. 2000).

Ganguly et al. (2001) suggested that GABA itself limits the time period during which it elevates cytosolic Ca2+ ([Ca2+]i) because chronic blockade of GABAA receptors prevented the developmental change of the GABA response and reduced the level of mRNA expression of KCC2 in cultured hippocampal neurons. The relationship between mRNA expression and transporter function, however, is not linear. In cultured neurons we found KCC2 to become functional in conjunction with a protein tyrosine kinase-dependent mechanism (Kelsch et al. 2001). On the other hand, GABA and glycine dissipate Cl− gradients. Unless inward transport counteracts the [Cl−]i depletion, the development of synapses releasing GABA shortens the developmental period during which an outward Cl− gradient exists and GABA elevates [Ca2+]i. The purpose of the present study was to re-examine the role that GABA might play in the developmental change of its own response.

METHODS

Cell culture and chronic treatments

All experiments were approved by the Animal Care and Use Committees responsible for our institution and were in accordance with the European Communities Council directive regarding care and use of animals for experimental procedures.

Pregnant Wistar rats were anaesthetized with ether and killed by decapitation. The embryos were removed, placed in sterile, ice-cold Gey's buffered salt solution containing (mm): 137 NaCl, 5 KCl, 0.3 MgSO4, 1 NaH2PO4, 1.5 CaCl2, 2.7 NaHCO3, 0.2 KH2PO4, 1 MgCl2 and 5 glucose, pH 7.4, and immediately decapitated. Ventral midbrain tissue from 14-day-old embryos was mechanically dissociated and plated on a primary culture of glial cells from the same area. Cell culture conditions were as previously described (Jarolimek & Misgeld, 1992).

Bicuculline and picrotoxin (Sigma-Aldrich, Taufkirchen, Germany) were added from 5 mm stocks to a final concentration of 20 μm each, 6-imino-3-(4-methoxyphenyl)-1(6H)-pyridazinebutanoic acid (SR 95531, gabazine) and strychnine (Sigma-Aldrich) to 10 and 1 μm, respectively. Tetrodotoxin (TTX, Alomone Labs, Jerusalem, Israel, or Biotrend (Tocris), Köln, Germany) was added from a 300 μm stock to a final concentration of 0.3 μm. Concentrations were maintained throughout the whole culture period. Cultures were fed twice a week by replacing half of the medium with or without drugs. Chronic treatments were started 3 days after plating (DIV).

Calcium imaging

Neurons were loaded with the Ca2+-sensitive dye Fura-2-AM (3 μm, Molecular Probes Europe BV, Leiden, The Netherlands) in the presence of 20 μm DNQX (6,7-dinitroquinoxaline-2,3-dione, Alexis, Grünberg, Germany) and 20 μm bicuculline for 30–40 min, either at room temperature in Hepes-buffered saline solution (Hepes) containing (mm): 156 NaCl, 2 KCl, 2 CaCl2, 1 MgCl2, 10 Hepes, 0.001 glycine and 15 glucose, pH 7.3, or at 35 °C in HCO3−-buffered saline solution (HCO3−) containing (mm): 156 NaCl, 2 KCl, 2 CaCl2, 1 MgCl2, 26 NaHCO3, 1.25 NaH2PO4, 0.001 glycine and 2 glucose, gassed with 5 % CO2, pH 7.3. In cultures chronically treated with bicuculline, picrotoxin and TTX, 0.3 μm TTX was also present during Fura-2-AM loading. Background-corrected fluorescence was taken with a slow-scan CCD camera system with fast monochromator (TILL Photonics, Gräfelfing, Germany) coupled on an Axiovert 100 microscope equipped with a Neofluar objective (10 ×, Zeiss, Oberkochen, Germany). Fura-2-AM was excited at 357 and 380 nm wavelengths, and fluorescence was collected between 500 and 540 nm at a frequency of 0.5 Hz. The change in [Ca2+]i is presented as the change in the fluorescence ratio obtained at the two excitation wavelengths (F357/F380). This experimental set-up allowed for the two-dimensional representation of Ca2+ signals in all cells simultaneously. Averages of fluorescence intensity from somatic regions were chosen for quantification (≈50–80 pixels) and analysed off-line with routines written in Igor Pro software (Wavemetrics, Eugene, OR, USA). A neuron was included in the analysis if the peak of the response from a 15 s reference application of 20 mm KCl was larger than threshold, defined as six standard deviations (S.D.) of the baseline noise (Ganguly et al. 2001). The same baseline S.D. criterion was used to count cells responsive to GABA and to calculate the average peak amplitudes. Ratios between peaks of the responses from different applications were calculated for each cell separately.

All recordings were carried out at room temperature (22–25 °C) in the presence of 20 μm DNQX and 0.3 μm TTX unless otherwise stated. In cultures chronically treated with bicuculline, picrotoxin and TTX, 20 μm bicuculline was also present during recordings. In solutions with raised KCl (20 mm KCl), NaCl concentration was reduced by the same amount to maintain Cl− concentration. When HCO3− buffered the extracellular solution it was continuously gassed with 95 % O2 and 5 % CO2. Solutions were exchanged using a multibarrelled perfusion system (2.5–3 ml min−1). To block L-type Ca2+ channels we used the specific antagonist D-600 (10 μm, Gallopamil-HCl, Knoll, Ludwigshafen, Germany). Ca2+ signals were enhanced by using the L-type Ca2+ channel agonist FPL 64176 (1–3 μm, 2,5-dimethyl-4-[2-(phenylmethyl)benzoyl]-1H-pyrrole-3-carboxlic acid methyl ester, Sigma-Aldrich).

Electrophysiological recordings

Electrophysiological recordings were carried out at room temperature in the whole-cell voltage-clamp configuration with a patch-clamp amplifier Axopatch 200B (Axon Instruments, Union City, CA, USA) or List EPC7 (List-Medical, Darmstadt, Germany). The composition of the extracellular solution was (mm): 156 NaCl, 1 CsCl (Jarolimek et al. 1999), 2 KCl, 2 CaCl2, 1 MgCl2, 15 glucose, 10 Hepes, pH 7.3. In experiments in which electrophysiological recordings were combined with calcium imaging the extracellular solution was Hepes-buffered saline solution as described above. Composition of the patch pipette solution was (mm): 3.5 NaCl, 5 KCl, 130 potassium glucuronate, 0.25 CaCl2, 0.5 MgCl2, 10 glucose, 10 Hepes, 5 QX314-Br, 2 Mg-ATP, 5 EGTA, pH 7.3. For a more detailed description see Jarolimek et al. (1999). Recordings of spontaneous IPSCs (sIPSCs) were performed with 10 μm DNQX and 1 μm DL-2-amino-4-methyl-5-phosphono-3-pentenoic acid (Sigma-Aldrich) in the extracellular solution to block glutamatergic synaptic currents. The remaining currents could be completely blocked by application of 20 μm bicuculline (Jarolimek et al. 1999). GABA (50 μm, Sigma-Aldrich) was diluted in the extracellular solution and applied by the perfusion system. Patch pipettes were fabricated from borosilicate glass (Hilgenberg, Malsfeld, Germany) and their resistances to bath ranged from 2.5 to 4.5 MΩ. The access resistance was estimated from the amplitude of the capacitive current evoked by a 5 mV rectangular pulse. Only access resistances between 10 and 20 MΩ were accepted and routinely checked during the recording. For a determination of the liquid junction potential between the patch pipette and the extracellular solution see Jarolimek et al. (1999). All values were corrected by −14 mV. Recordings were started > 5 min after the whole-cell configuration was established to allow adequate time for QX314-Br (Sigma-Aldrich) to take effect and for anions to equilibrate. After 5 min, no further change in dendritic or somatic [Cl−]i was observed for the duration of recording. Data were filtered at 1.3 kHz with a 4-pole Bessel filter and acquired with pCLAMP6 or pCLAMP8 software (Axon Instruments). The amplitudes of sIPSCs were analysed with a program written in our laboratory (Jarolimek & Misgeld, 1997) and Igor Pro software.

Gramicidin perforated-patch recordings

The perforated-patch recording technique with the chloride-impermeable ionophore gramicidin (gramicidin D, Dubos, Sigma) was chosen to monitor changes in [Cl−]i (Abe et al. 1994; Reichling et al. 1994; Ebihara et al. 1995). The tip of the recording pipette was immersed for a few seconds into the recording solution (150 mm KCl; 10 mm Hepes) and subsequently back-filled with the recording solution containing 10–50 μg ml−1 of gramicidin (from a 50 mg ml−1 stock solution in DMSO). After the cell-attached configuration had been attained, 10 mV hyperpolarizing step pulses of 100 ms duration were periodically delivered to monitor the access resistance. Resistance of the electrodes was 4–7 MΩ. After the access resistance had reached a steady level between 20 and 80 MΩ the recording started. The resulting currents were sampled at 5 kHz and filtered at 1.3 kHz. Since neurons were loaded with the Ca2+-sensitive dye Fura-2-AM, the fluorescence signal at 357 nm was used to monitor the stability of the perforated-patch configuration. Additionally, in the conventional whole-cell configuration after rupturing the gramicidin perforated-patch membrane by applying greater negative pressure to the pipette interior, EGABA shifted to near 0 mV.

RESULTS

Developmental change of the GABA response in cultured midbrain neurons

Previous studies have shown that GABA depolarizes immature CNS neurons and, thereby, elevates [Ca2+]i, but hyperpolarizes most mature neurons (cf. Introduction). The Ca2+ influx elicited by GABA depends on the properties of the Ca2+ channels activated by membrane depolarization (Chen et al. 1996; Owens et al. 1996; Eilers et al. 2001; Ganguly et al. 2001). In line with a developmental change of the GABA response, the percentage of cultured midbrain neurons that responded to GABA with an elevation of [Ca2+]i decreased with age. In the nominal absence of HCO3− ions (Hepes-buffered bath solution), the number of neurons that responded to GABA (50 μm, 15 s pulse) declined within a few days after DIV 9 (at DIV 6–9: 92 %, n = 8, 1008 cells; at DIV 12–15: 50 %, n = 11, 534 cells; after 3 weeks ≤ 10 %, n = 12, 227 cells). In HCO3−-buffered bath solution the developmental change was somewhat slower, possibly reflecting a contribution of HCO3− to depolarizing GABA responses (Kaila et al. 1993). Before DIV 15 most neurons responded to GABA with an increase in [Ca2+]i (Fig. 1; at DIV 5–10: 99 %, n = 29, 1008 cells; at DIV 12–15: 89 %, n = 20, 353 cells). After 3 weeks, the majority displayed no [Ca2+]i increases in response to GABA (Fig. 2) and only 32 % of the neurons (n = 5, 113 cells) remained responsive after 4 weeks. In comparison, KCl-induced depolarizations (20 mm, 15 s) elicited [Ca2+]i elevations (Hepes- and HCO3−-buffered solution) in both immature and mature neurons (Fig. 1 and Fig. 2). In all these experiments, spontaneous synaptic activity was blocked by the Na+ channel blocker TTX and the AMPA receptor antagonist DNQX. Washout of TTX and DNQX resulted in small elevations of [Ca2+]i indicating spontaneous synaptic background activity. Blockade of the GABAA receptors by bicuculline evoked large synchronous [Ca2+]i oscillations in all neurons. These oscillations increased in size and frequency with maturation (Fig. 1 and Fig. 2). We observed such oscillations invariably after ≥ DIV 12 (HCO3− buffer: n = 3, 93 cells; Hepes buffer: n = 3, 84 cells). The sensitivity of the spontaneous [Ca2+]i oscillations to DNQX (10 μm) indicated that the underlying network activity was mediated through AMPA receptors. Thus maturation of neurons terminated [Ca2+]i elevations by GABA but not those by KCl or synaptic activity.

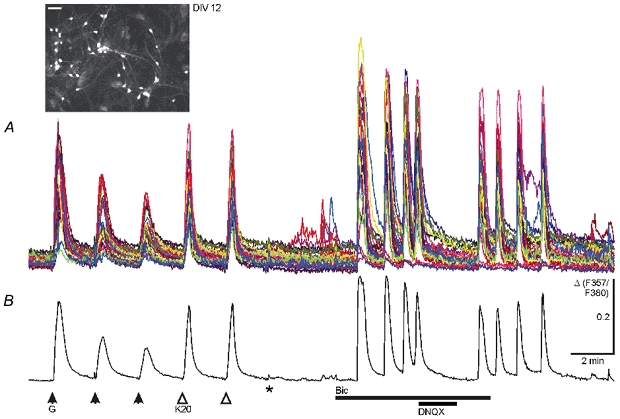

Figure 1. GABA-induced and spontaneous [Ca2+]i increases in immature cultured midbrain neurons at DIV 12.

A, somatic Ca2+ transients from 33 cells with decreasing and constant amplitudes were elicited by repetitive applications of GABA (G, 50 μm, 15 s pulse) and KCl (K20, 20 mm, 15 s pulse), respectively, in the presence of 0.3 μm TTX and 20 μm DNQX. Washout of TTX and DNQX (*) resulted in small spontaneous rises in [Ca2+]i in a few cells. After blockade of GABAA receptor-mediated inhibition (Bic, 20 μm), cells displayed spontaneous synchronized Ca2+ oscillations that were reversibly blocked by DNQX (20 μm). Synchronous activity ceased after washout of bicuculline. B, average of the 33 traces shown in A. Ca2+ transients were recorded in solutions buffered with HCO3−. Inset shows fluorescence image of Fura-2-AM-loaded neurons from this experiment excited at 357 nm; scale bar, 50 μm. The change in [Ca2+]i is presented as the change (Δ) in the fluorescence ratio obtained at the two excitation wavelengths (F357/F380). Δ is given in arbitrary units in this and all other figures.

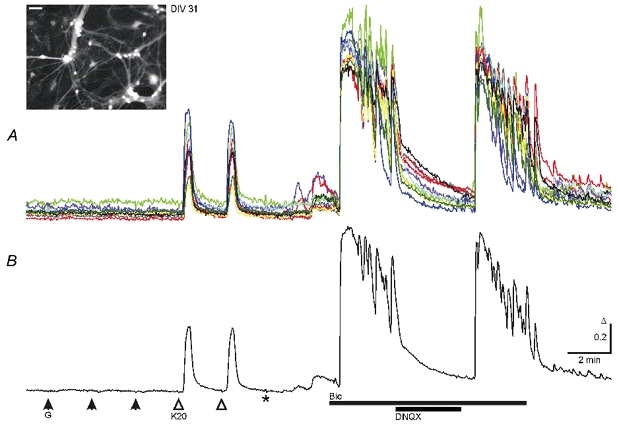

Figure 2. KCl- but not GABA-induced and spontaneous [Ca2+]i increases in mature cultured midbrain neurons at DIV 31.

A, GABA applications (G, 50 μm) failed to induce Ca2+ transients while KCl (K20, 20 mm) induced responses with similar properties to those shown in Fig. 1. Responses were recorded in the presence of 0.3 μm TTX and 20 μm DNQX. Washout of TTX and DNQX (*) resulted in small spontaneous rises in [Ca2+]i in all cells. Blockade of GABAA receptors by bicuculline (Bic, 20 μm) led to synchronized Ca2+ oscillations with higher frequency and amplitudes than those at DIV 12 (Fig. 1). Ca2+ oscillations were reversibly blocked by DNQX (20 μm). B, average of the 10 traces shown in the top panel. Ca2+ transients were recorded in solutions buffered with HCO3−. Inset shows fluorescence image of Fura-2-AM-loaded neurons from this experiment excited at 357 nm; scale bar, 50 μm.

Developmental change of the GABA response and of GABAergic synaptic activity

It has been suggested that the developmental transformation of the GABA response depends on GABAergic synaptic activity elevating [Ca2+]i in hippocampal neurons (Ganguly et al. 2001). We examined spontaneous GABAA receptor-mediated synaptic potentials for their development and their ability to elevate [Ca2+]i in HCO3−-buffered solution. At DIV 5–6 there were spontaneous [Ca2+]i elevations in a small fraction of neurons (18 %, n = 4, 196 cells) which disappeared upon wash-in of bicuculline or picrotoxin (20 μm, Fig. 3A). The majority of neurons displayed either no or very small spontaneous [Ca2+]i elevations (Fig. 3A) that were insensitive to bicuculline or DNQX. At DIV 7–10, spontaneous [Ca2+]i increases appeared in 40 % of all neurons (n = 11, 435 cells). The increases were blocked by DNQX (10 μm), whereas they increased or decreased in size and frequency in the presence of bicuculline. Similar results were obtained from recordings in Hepes-buffered solution. This suggested that, before DIV 12, spontaneous synaptic activity mediated by GABAA receptors depended on an excitatory glutamatergic drive. To test this assumption, we used whole-cell recording in Hepes-buffered solution to compare the spontaneous synaptic activity in neurons at DIV 7 (n = 22) and 16 (n = 16). At DIV 7, spontaneous activity was rare, but could be separated into outward and inward currents at appropriate holding potentials suggesting that the underlying conductance for outward currents was a Cl− conductance. In every instance, all synaptic activity was blocked by DNQX (Fig. 3B). At DIV 16, spontaneous GABAA receptor-mediated synaptic currents could be readily observed in DNQX. In parallel to changes in synaptic transmission we observed a hyperpolarizing shift of the membrane potential at zero holding current (mean −64 mV vs. −73 mV, min/max −54/−80 mV vs. −60/−92 mV at DIV 7 and 16, respectively; P < 0.02). The increase in synaptic activity and the shift to a more hyperpolarized membrane potential coincided with the time period of the main developmental change in the GABA response.

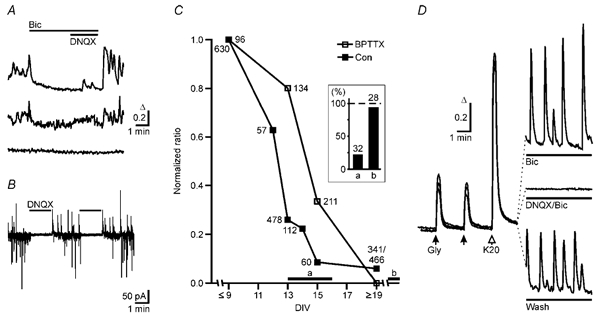

Figure 3. Chronic blockade of GABAA receptors does not prevent the developmental change of the GABA response.

A, spontaneous GABAA receptor-mediated calcium transients in developing neurons at DIV 8. The majority of neurons exhibited no spontaneous Ca2+ transients (bottom trace), but some neurons showed bicuculline-sensitive (top trace) Ca2+ signals. In addition we observed signals that were neither bicuculline nor DNQX sensitive. B, spontaneous synaptic currents in developing neurons (DIV 7) recorded at a holding potential (VH) at which spontaneous IPSCs and EPSCs were outward and inward currents, respectively. Application of the AMPA receptor blocker DNQX reversibly abolished all synaptic activity indicating that at this developmental stage most GABAergic neurons were not spontaneously active in the absence of an excitatory drive. C, time course of the GABA/glycine responses in control cultures (Con) and in cultures chronically treated (BPTTX: 20 μm bicuculline, 20 μm picrotoxin, 0.3 μm TTX). GABA/glycine-evoked Ca2+ signals were divided by the mean 20 mm KCl-induced Ca2+ signal (control 590 ± 8, n = 40, 1678 cells; BPTTX 1322 ± 16, n = 11, 907 cells). Before DIV 9, responses remained largely unchanged in control. Therefore ratios were normalized to the value at DIV ≤ 9 and plotted against the age of culture (n = 1–12 cultures, 51 in total). Inset shows that the relative abundance of neurons (columns a and b) with K+–Cl− cotransport activity increases in parallel with time in culture as revealed by patch-clamp recording (Kelsch et al. 2001). Times during which neurons with and without transport activity were sampled are indicated by the horizontal bars a and b in the plot of the GABA/glycine responses. The number of cells is indicated for each point in the plot and the columns in the inset. D, average Ca2+ signals induced by glycine and KCl and by spontaneous activity in three BPTTX-treated cultures at DIV 10. Left panel, responses from three different cultures to glycine (0.5 mm) and KCl (20 mm) in the presence of bicuculline, DNQX and TTX. Under these conditions no spontaneous calcium transients could be observed (right, middle trace, average of 135 cells). Neurons displayed spontaneous synchronized Ca2+ oscillations upon removal of antagonists (right, bottom trace, average of 79 cells). These oscillations were enhanced in the presence of bicuculline (right, top trace, average of 79 cells).

To examine whether GABAA receptor-mediated synaptic activity accelerated the transformation of the GABA response, we raised cultures in the continuous presence of bicuculline and picrotoxin in a preliminary experiment (20 μm each, Ganguly et al. 2001). In these cultures only a few neurons survived up to DIV 20 and 73 % (n = 9, 116 cells) of these neurons were unresponsive to GABA applications. When we added the GABAA receptor antagonists together with TTX (0.3 μm), the cell number in these cultures was comparable to control cultures and, therefore, all other experiments with chronic blockade of GABAA receptors were carried out in the presence of TTX. In cultures treated chronically with GABAA receptor antagonists we applied glycine rather than GABA, because glycine or the GABAA receptor agonist muscimol (0.5 mm or 10 μm, respectively, data not shown) also elevated [Ca2+]i indicating that the responses were mediated by ionotropic receptor channels. The time course of the developmental change in the GABA response from chronically treated cultures is compared to control cultures in Fig. 3C. Depolarization-induced Ca2+ signals varied among cells, but as a general rule amplitudes of GABA responses declined before neurons became unresponsive. Since the responses to 20 mm KCl remained largely unchanged, we used the KCl-induced [Ca2+]i signal to normalize GABA-induced responses (GABA/K20 ratio). The mean GABA/ K20 ratio in Hepes-buffered solution continuously declined after DIV 9, and most neurons became unresponsive at DIV 15 (Fig. 3C). In the chronically treated cultures many cells at DIV 13 and 15 responded to glycine (0.5 mm, Fig. 3D) or GABA (after washout of the antagonists) with elevations of [Ca2+]i in Hepes-buffered solution, but most neurons did not display [Ca2+]i elevations in response to glycine after DIV 19 (Fig. 3C). [Ca2+]i rises in response to KCl were larger in these neurons (Fig. 3D) than in neurons of untreated cultures (cf. Ganguly et al. 2001), and synaptic activity was drastically altered. Already from DIV 8 onwards, washout of TTX revealed spontaneous synchronous [Ca2+]i oscillations. The [Ca2+]i oscillations occurred even in the absence of a GABAA receptor antagonist (Fig. 3D). To exclude a contribution of glycine to the developmental change of the GABA response we also incubated cultures chronically with strychnine (1 μm), gabazine (10 μm) and TTX (0.3 μm). The time course of the developmental change of the GABA response was similar to the time course found in cultures treated with bicuculline, picrotoxin and TTX. After DIV 19, 94 % of neurons were unresponsive to GABA (n = 9, 149 cells). The data indicate that activation of GABAA or glycine receptors is not required to terminate the time period during which GABA elevates [Ca2+]i.

We also examined the neurons for the expression of functional K+-Cl− cotransport during development. Using an assay which we described previously (Jarolimek et al. 1999; Kelsch et al. 2001), we could identify two groups of midbrain neurons, one with and one without K+-Cl− cotransport activity (cf. Kelsch et al. 2001). Neurons with transport activity predominated in midbrain cultures at DIV 22–28 (Fig. 3C, inset column b), whereas there were only a few neurons exhibiting transport activity in cultures at DIV 13–16 (Fig. 3C, inset column a). This indicated that neurons with K+-Cl− cotransport activity were abundant in cultures in which [Ca2+]i elevations in response to GABA had disappeared.

The change in the GABA response from Ca2+ influx to Ca2+ decrease

Data reported so far have shown that the developmental decline of the GABA response took place in parallel to three processes: membrane hyperpolarization, increase in GABAergic synaptic activity and the appearance of neurons with outward Cl− transport activity. Apparent unresponsiveness to GABA or glycine when measuring [Ca2+]i does not distinguish between a decrease in driving force for anionic currents or an increase in negativity of the membrane potential and can also result from changes in Ca2+ channel properties or cellular Ca2+ homeostatic mechanisms. Only decreases in [Ca2+]i in response to GABA would indicate that the gradient for chloride currents has reversed in sign. A substantial fraction of the Ca2+ influx was through L-type Ca2+ channels as the L-type-specific Ca2+ channel antagonist D-600 reversibly inhibited the increase in [Ca2+]i (10 μm, 49 ± 8 % reduction of the ratio 2nd over 1st response as compared to controls, n = 1, 41 cells). To allow activation of L-type Ca2+ channels at more negative membrane potentials, we applied the L-type Ca2+ channel agonist FPL 64176 (1–3 μm), which prolongs channel openings and shifts channel activation in hyperpolarizing direction (Kunze & Rampe, 1992). Application of FPL 64176 alone increased resting [Ca2+]i levels (Fig. 4A and B2). In the presence of FPL 64176, a larger fraction of immature neurons responded to GABA with transient increases in [Ca2+]i compared to control (DIV 8: n = 1, 49/51 cells; DIV 15: n = 1, 29/35 cells, data not shown). In mature neurons (DIV 28–30) which were unresponsive under control conditions, it was possible to detect GABA- or glycine-induced transient decreases of [Ca2+]i (Fig. 4; n = 7, 126/274 cells). We observed [Ca2+]i decreases in mature neurons regardless of whether they had been raised in the presence or absence of GABAA receptor antagonists. Although measurements of [Ca2+]i do not directly address [Cl−]i, the change of the GABA response from elevating to decreasing [Ca2+]i in Hepes buffer strongly suggests that a gradient for depolarizing Cl− currents reversed to a gradient for hyperpolarizing Cl− currents during development. Ca2+ channels which are open in the presence of FPL 64176 close upon membrane hyperpolarization resulting in a decrease in [Ca2+]i.

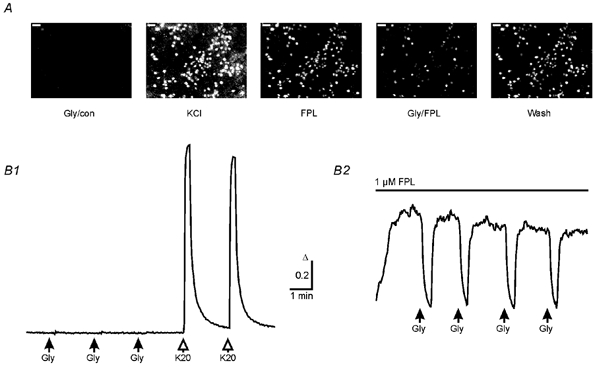

Figure 4. [Ca2+]i decreases in response to glycine in the presence of the L-type Ca2+ channel agonist FPL 64176.

A, fluorescence ratio images (F357/F380) of typical [Ca2+]i in neurons at DIV 29 from a BPTTX-treated culture during the first glycine application (Gly/con), during application of 20 mm KCl (KCl), after adding FPL 64176 (FPL, 1 μm), during the first glycine application in the presence of FPL (Gly/FPL) and after the pulse of glycine (Wash). Calibration bars: 50 μm; higher intensity represents higher [Ca2+]i. B, averages of [Ca2+]i responses to glycine or KCl applications (Gly, 0.5 mm; K20, 20 mm; 15 s pulses, 63 cells) obtained from the culture shown in A under control condition (B1) and in the presence of 1 μm FPL (B2). Note that elevation in basal [Ca2+]i by FPL allows monitoring of the glycine-induced [Ca2+]i decrease, although these cells had been treated chronically with GABAA receptor antagonists and TTX. Same calibration for B1 and B2. All cells were monitored in Hepes buffer.

The change of the [Ca2+]i response induced by GABA itself

Upon repetitive GABA applications the amplitude of [Ca2+]i elevations declined in immature neurons whereas it remained constant for repetitive KCl applications. The [Ca2+]i signal also declined if GABA was substituted by glycine (0.5 mm) or GABA and glycine were applied alternately (Fig. 5C; n = 13, 255 cells). This indicated that the observed decline in [Ca2+]i transients was not due to receptor desensitization (identical results in Hepes- and HCO3−-buffered solution). In gramicidin perforated-patch recordings (n = 13), Cl− currents induced by GABA applications declined in parallel to [Ca2+]i elevations (Fig. 5A), but a driving force for GABA-induced Cl− currents could be immediately recovered by changing the holding potential. In contrast, in whole-cell recording in which [Cl−]i was defined by the pipette solution, repetitive applications of GABA elicited inward currents without decline (Fig. 5B; n = 5, all in Hepes-buffered solution). Therefore, the decrementing Ca2+ response reflected a reduction of the underlying Cl− current which resulted from a fading of the driving force for Cl− currents. Taken together these findings indicated that GABA or glycine receptor activation dissipated the Cl− gradient underlying the membrane depolarization and that there was no inward transport efficient enough to compensate [Cl−]i losses during these GABA responses. We examined whether GABA present in physiological concentrations activates Cl− conductance sufficiently to reduce the [Ca2+]i response. We applied low GABA concentrations for 20 min (in Hepes-buffered solution) to cells that had been raised and maintained permanently in the presence of bicuculline, picrotoxin and TTX up to the time point at which the test was performed. The [Ca2+]i elevation by the second response to glycine was drastically reduced if concentrations of GABA higher than 0.1 μm were applied after the first pulse (Fig. 5D). The Cl− conductance induced by 0.3 μm GABA sufficed to reduce [Ca2+]i elevations within 20 min. This requires that leak Cl− conductance of these neurons was very low in the absence of GABA. Membrane depolarization may open voltage-dependent Cl− channels thereby allowing elevation of [Cl−]i (Smith et al. 1995). We therefore tried to reverse the decline of the Ca2+ response by membrane depolarization through prolonged application of KCl (20 mm, 5–8 min). After returning to normal [K+]o, [Ca2+]i elevations in response to GABA were indeed larger (Fig. 6A and B). Activation of GABAA receptors was not required as similar results were obtained with glycine in the presence of bicuculline (20 μm). If cells were not exposed to high [K+]o, the GABA response did not recover (15 min, Fig. 6B) in immature neurons. In contrast, in mature neurons (DIV 29), repetitive GABA or glycine applications resulted in transient decreases in [Ca2+]i with constant amplitudes (Fig. 6C). Following depolarization by KCl (20 mm, 3–5 min), the amplitude of the agonist-induced decreases in [Ca2+]i was reduced and recovered during subsequent agonist applications (Fig. 6C). Thus, in contrast to immature neurons, mature neurons were capable of maintaining a gradient for the Cl− currents that reduced [Ca2+]i.

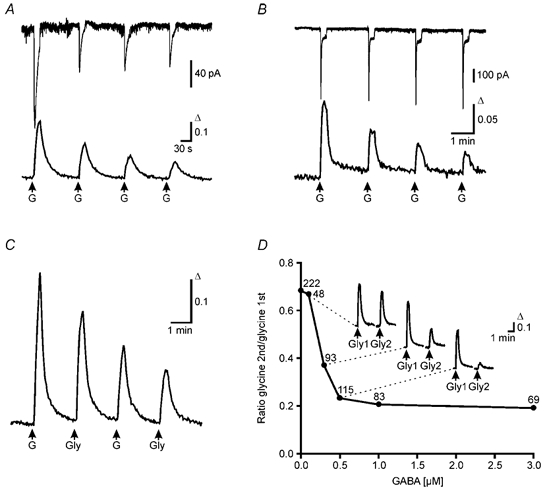

Figure 5. [Ca2+]i elevations and Cl− currents in response to GABA and glycine.

A, combined gramicidin perforated-patch recording and calcium imaging at DIV 8. Amplitude of the Cl− current of a single cell obtained by perforated-patch recording (top trace, VH = −60 mV) and the simultaneously recorded Ca2+ transients of the whole cell population (bottom trace, average of 32 cells) declined exponentially with repetitive application of GABA (50 μm, 15 s pulse). B, combined whole-cell patch recording and calcium imaging at DIV 13. Amplitude of current responses from a whole-cell patch recording (top trace, VH = −75 mV) remained constant during repetitive application of GABA (50 μm, 15 s pulse). In contrast the Ca2+ transients recorded in parallel (bottom trace, average of 15 cells) declined. C, average of Ca2+ transients elicited by alternating GABA and glycine applications (50 μm and 500 μm, respectively, 15 s pulse, 12 cells) from a culture at DIV 7. D, nanomolar concentrations of GABA suffice to reduce glycine-evoked Ca2+ transients. Between two glycine applications, BPTTX-incubated cultures (DIV 9–13) were superfused for 20 min with low GABA concentrations (0.1–3 μm). The ratios between the amplitudes of the second (Gly2) and the first (Gly1) glycine responses were plotted against the GABA concentration. Insets show averaged responses for control (n = 17), 0.3 μm GABA (n = 35) and 0.5 μm GABA (n = 23). Number of cells indicated for each point.

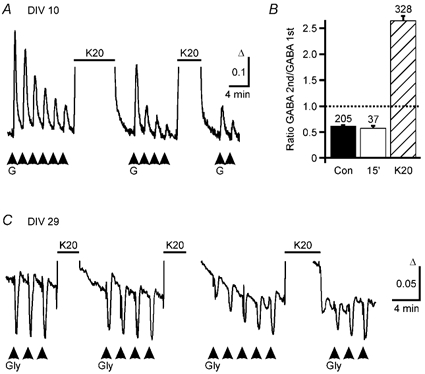

Figure 6. Prolonged depolarizations restore GABA responses in immature neurons, but reduce GABA responses in mature neurons only transiently.

A, averaged (7 cells) GABA-induced Ca2+ responses are shown for cells at DIV 10. During repetitive applications of GABA (G, 50 μm, 15 s pulses) [Ca2+]i responses decreased. After an elevation of [K+]o (horizontal bar, K20, 20 mm, 8 min) the GABA-induced [Ca2+]i responses re-increased and declined again with further GABA applications. The decrement was reversed for a second time by a second elevation of [K+]o (5 min). B, reduction of [Ca2+]i signals induced by repetitive GABA applications can be reversed by intermediate elevation of [K+]o (K20, 8 min, hatched bar) but not by a 15 min wash period (15′, open bar). The amplitude of the second response elicited by two subsequent GABA applications was on average reduced to 60 % of the first response under control conditions (Con, filled bar, n = 6). A washout period of 15 min between the two applications did not restore the response (15′, open bar, n = 4). However, elevation of [K+]o to 20 mm (K20, 8 min, n = 9) between GABA applications led to an increase of the following responses. C, averaged (13 cells) glycine-induced [Ca2+]i responses are displayed for cells at DIV 29. Repetitive applications of glycine (Gly) induced transient decreases in [Ca2+]i. Transient elevation of [K+]o (K20, 3–5 min) led to a reduction of the glycine-induced Ca2+ signals that recovered despite repetitive glycine applications. In this experiment, GABAA receptors were blocked by bicuculline (20 μm).

DISCUSSION

The main result of our study is that, despite its [Ca2+]i elevating action in early development, GABAA receptor activation is not required for the developmental switch of the GABA response from depolarizing to hyperpolarizing. In addition, inward Cl− transport is not effective in immature cultured midbrain neurons although the response to GABA is depolarizing.

During an early developmental period, GABAA receptor-mediated synaptic potentials induced elevations of [Ca2+]i in immature midbrain neurons. [Ca2+]i elevations by GABAergic synaptic activity have been reported previously, e.g. for hypothalamic (Obrietan & van den Pol, 1995) and cortical (Owens et al. 1996) neurons. A pharmacological identification of Ca2+ signals driven by GABAergic synapses was possible only in immature neurons before DIV 12. The Ca2+ signals were reduced by a GABAA receptor antagonist. They did not, however, persist in the presence of antagonists for glutamatergic excitation suggesting that most immature GABAergic neurons were only spontaneously active if driven by glutamatergic excitation. With maturation, blockade of GABAA receptors promoted the appearance of spontaneous AMPA receptor-mediated Ca2+ signals and produced, from DIV 12 onwards, large [Ca2+]i oscillations which are due to synchronous burst discharges (Rohrbacher et al. 1998). Thus, even if GABA depolarizes neurons, GABAergic synapses can have an inhibitory action (Lamsa et al. 2000). Synaptic activity in midbrain cultures which we raised under blockade of GABAA receptors and in the presence of TTX differed from synaptic activity in control networks. The differences may result from influences on network maturation by GABA-mediated [Ca2+]i rises (Lipton & Kater, 1989; LoTurco et al. 1995; Marty et al. 1996; Obrietan & van den Pol, 1996; Barker et al. 1998; Kneussel & Betz, 2000; Maric et al. 2001).

As in other brain regions (cf. Introduction), there was a developmental change in the GABA response in midbrain culture which terminated the period of [Ca2+]i-elevating responses. An attractive hypothesis put forward by Ganguly et al. (2001) describes the developmental change of the GABA response as a self-limiting process which is set in motion by GABA. The proposed mechanism is an increase in [Ca2+]i through the GABAA receptor-mediated membrane depolarization which up-regulates KCC2 gene expression. KCC2 in turn will reduce or reverse the gradient which underlies Cl− efflux and, thereby, membrane depolarization and elevation of [Ca2+]i. The proposal was based on the observation that hippocampal neurons treated chronically with GABAA receptor blockers permanently displayed [Ca2+]i elevations in response to GABA. Surprisingly, the GABA response of midbrain neurons changed from elevating to reducing [Ca2+]i regardless of whether we raised cultures in the presence or absence of GABAA receptor antagonists. A possible explanation for this discrepancy between the two studies may reside in the fact that different brain regions were studied. However, in our hands hippocampal neurons raised in the presence of GABAA receptor antagonists also developed hyperpolarizing responses with maturation (unpublished observations). Another possibility is that chronic GABAA receptor blockade induces cell damage (Choi, 1992). Cell damage, in turn, may reduce the expression of the KCC2 gene (van den Pol et al. 1996).

In the adult brain in vivo, ambient GABA concentrations of up to 3 μm and even higher concentrations for glycine have been measured (Lerma et al. 1986; Tossman et al. 1986; Kennedy et al. 2002). The developmental change in the response to exogenous GABA has been shown to reflect a developmental decrease of [Cl−]i (Chen et al. 1996; Owens et al. 1996). We found that nanomolar concentrations of GABA reduced the [Ca2+]i response within 20 min in cultures in which GABAA receptors had been blocked until the cells were exposed to the low GABA concentrations. Our study also shows that repetitive GABA or glycine applications in the presence of Hepes as well as HCO3− buffer reduce the response. The decline of the response suggested that the gradient driving depolarizing Cl− currents decreased because, in the nominal absence of HCO3− ions, the current induced by GABA or glycine is carried by Cl− ions. We excluded the possibility that changes in receptor properties were responsible as GABA and glycine could replace each other in this effect. In gramicidin perforated-patch recordings which do not control [Cl−]i (Ebihara et al. 1995; Kyrozis & Reichling, 1995), the Cl− currents declined in parallel to the decline of [Ca2+]i rises in response to GABA. In contrast, in parallel whole-cell recordings, currents induced by repetitive GABA applications were unchanged because [Cl−]i was fixed by the solution in the recording pipette.

Inward transport has been suggested as a mechanism establishing the gradient for depolarizing Cl− currents in immature neurons (for a review see Delpire, 2000). Supporting this assumption, mRNA for NKCC1 is expressed in neurons as it is in our cultures (W. Kelsch, S. Hormuzdi, E. Straube, A. Lewen, H. Monyer & U. Misgeld, unpublished observation). However, reports on NKCC1 in neurons are not unanimous with respect to its presence, developmental regulation and location of the protein (Plotkin et al. 1997; Clayton et al. 1998; Sun & Murali, 1999; Hübner et al. 2001a; Yan et al. 2001; Marty et al. 2002). Our data indicate that cultured midbrain neurons have no efficient inward transport which compensates losses of [Cl−]i resulting from activation of GABAA receptors by nanomolar concentrations of GABA as long as they are immature. Therefore, when Cl− channels are opened by a ligand, [Cl−]i will assume a passive distribution with a time course given by the amount of charge flowing through the channels. The developmental change of the GABA response in cultures treated chronically with GABAA receptor blockers did not reveal a strong contribution of a GABA-activated Cl− conductance under culturing conditions. In contrast, once neurons are mature, they can keep [Cl−]i below a concentration given by the passive equilibrium, even if repetitive GABA applications induce an increase in [Cl−]i. Moreover, an elevation of [Cl−]i by a prolonged [K+]o elevation was compensated by mature neurons.

Our data suggest that depolarizing responses to GABA arise even in the absence of an effective Cl− inward transport. Based on our experiments with transient elevations of [K+]o, we suggest a contribution of an alternative mechanism. Elevation of [K+]o leads to an increase in [Cl−]i, if a pathway exists for Cl− to enter the cells. Such a pathway can be provided by GABA- or glycine-gated Cl− channels, but we observed this effect also in the presence of the GABAA receptor antagonist bicuculline. Another possible pathway is KCC2, which reverses its direction if [K+]o is elevated (Jarolimek et al. 1999). KCC2 is probably the main pathway in mature neurons, but is not functional in immature neurons. In immature neurons a pathway could be provided by voltage-dependent Cl− channels, i.e. ClC3 channels (Smith et al. 1995). Indeed, a Cl− conductance can be activated in these neurons at −30 mV (W. Jarolimek, H. Brunner, A. Lewen & U. Misgeld, unpublished observation). We suggest that the high [Cl−]i leading to depolarizing GABAA responses is caused by electrogenic, channel-mediated Cl− uptake that takes place during membrane depolarizations created by other mechanisms such as glutamatergic transmission or increases in [K+]o.

In conclusion, blockade of GABAA receptors does not prevent the developmental change of the GABA response in cultured neurons. An acceleration of the developmental change by GABA could be secondary to dissipation of the Cl− gradient. Nanomolar concentrations of GABA diminish the Ca2+-elevating response indicating that there is no inward Cl− transport in immature cultured neurons, which is as effective as is outward transport in mature cultured neurons. However, membrane depolarizations and/or [K+]o increases can elevate [Cl−]i and, thereby, support gradients for depolarizing GABA responses.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Drs A. Draguhn, L. Godinho and T. Misgeld for helpful discussions and C. Heuser for excellent technical assistance. This study was supported by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (MI 255/4–3, SFB 488/D9, SW 13/6–1).

REFERENCES

- Abe Y, Furukawa K, Itoyama Y, Akaike N. Glycine response in acutely dissociated ventromedial hypothalamic neuron of the rat: new approach with gramicidin perforated patch-clamp technique. J Neurophysiol. 1994;72:1530–1537. doi: 10.1152/jn.1994.72.4.1530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barker JL, Behar T, Li YX, Liu QY, Ma W, Maric D, Maric I, Schaffner AE, Serafini R, Smith SV, Somogyi R, Vautrin JY, Wen XL, Xian H. GABAergic cells and signals in CNS development. Perspect Dev Neurobiol. 1998;5:305–322. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ben-Ari Y, Cherubini E, Corradetti R, Gaiarsa J-L. Giant synaptic potentials in immature rat CA3 hippocampal neurones. J Physiol. 1989;416:303–325. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1989.sp017762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bormann J, Hamill OP, Sakmann B. Mechanism of anion permeation through channels gated by glycine and γ-amino-butyric acid in mouse cultured spinal neurones. J Physiol. 1987;385:243–286. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1987.sp016493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen G, Trombley PQ, van den Pol AN. Excitatory actions of GABA in developing rat hypothalamic neurones. J Physiol. 1996;494:451–464. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1996.sp021505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi DW. Excitotoxic cell death. J Neurobiol. 1992;23:1261–1276. doi: 10.1002/neu.480230915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clayton GH, Owens GC, Wolff JS, Smith RL. Ontogeny of cation-Cl− cotransporter expression in rat neocortex. Develop Brain Res. 1998;109:281–292. doi: 10.1016/s0165-3806(98)00078-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delpire E. Cation-chloride cotransporters in neuronal communication. News Physiol Sci. 2000;15:309–312. doi: 10.1152/physiologyonline.2000.15.6.309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ebihara S, Shirato K, Harata N, Akaike N. Gramicidin-perforated patch recording: GABA response in mammalian neurones with intact intracellular chloride. J Physiol. 1995;484:77–86. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1995.sp020649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eilers J, Plant TD, Marandi N, Konnerth A. GABA-mediated Ca2+ signalling in developing rat cerebellar Purkinje neurones. J Physiol. 2001;536:429–437. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2001.0429c.xd. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ganguly K, Schinder AF, Wong ST, Poo M. GABA itself promotes the developmental switch of neuronal GABAergic responses from excitation to inhibition. Cell. 2001;105:521–532. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00341-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garaschuk O, Hanse E, Konnerth A. Developmental profile and synaptic origin of early network oscillations in the CA1 region of rat neonatal hippocampus. J Physiol. 1998;507:219–236. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1998.219bu.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hübner CA, Lorke DE, Hermans-Borgmeyer I. Expression of the Na-K-2Cl-cotransporter NKCC1 during mouse development. Mech Dev. 2001a;102:267–269. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4773(01)00309-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hübner CA, Stein V, Hermans-Borgmeyer I, Meyer T, Ballanyi K, Jentsch TJ. Disruption of KCC2 reveals an essential role of K–Cl cotransport already in early synaptic inhibition. Neuron. 2001b;30:515–524. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(01)00297-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jang I-S, Jeong H-J, Akaike N. Contribution of the Na–K–Cl cotransporter on GABAA receptor-mediated presynaptic depolarization in excitatory nerve terminals. J Neurosci. 2001;21:5962–5972. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-16-05962.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jarolimek W, Lewen A, Misgeld U. A furosemide-sensitive K+–Cl− cotransporter counteracts intracellular Cl− accumulation and depletion in cultured rat midbrain neurons. J Neurosci. 1999;19:4695–4704. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-12-04695.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jarolimek W, Misgeld U. On the inhibitory actions of baclofen and γ-aminobutyric acid in rat ventral midbrain culture. J Physiol. 1992;451:419–443. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1992.sp019171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jarolimek W, Misgeld U. GABAB receptor-mediated inhibition of tetrodotoxin-resistant GABA release in rodent hippocampal CA1 pyramidal cells. J Neurosci. 1997;17:1025–1032. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-03-01025.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaila K, Voipio J, Paalasmaa P, Pasternack M, Deisz RA. The role of bicarbonate in GABAA receptor-mediated IPSPs of rat neocortical neurones. J Physiol. 1993;464:273–289. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1993.sp019634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kakazu Y, Akaike N, Komiyama S, Nabekura J. Regulation of intracellular chloride by cotransporters in developing lateral superior olive neurons. J Neurosci. 1999;19:2843–2851. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-08-02843.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelsch W, Hormuzdi S, Straube E, Lewen A, Monyer H, Misgeld U. Insulin-like growth factor 1 and a cytosolic tyrosine kinase activate chloride outward transport during maturation of hippocampal neurons. J Neurosci. 2001;21:8339–8347. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-21-08339.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy RT, Thompson JE, Vickroy TW. In vivo monitoring of amino acids by direct sampling of brain extracellular fluid at ultralow flow rates and capillary electrophoresis. J Neurosci Meth. 2002;114:39–49. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0270(01)00506-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kneussel M, Betz H. Clustering of inhibitory neurotransmitter receptors at developing postsynaptic sites: the membrane activation model. Trends Neurosci. 2000;23:429–435. doi: 10.1016/s0166-2236(00)01627-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kobayashi S, Morgans CW, Casey JR, Kopito RR. AE3 anion exchanger isoforms in the vertebrate retina: developmental regulation and differential expression in neurons and glia. J Neurosci. 1994;14:6266–6279. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.14-10-06266.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kunze DL, Rampe D. Characterization of the effects of a new Ca2+ channel activator, FPL 64176, in GH3 cells. Mol Pharmacol. 1992;42:666–670. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kyrozis A, Reichling DB. Perforated-patch recording with gramicidin avoids artifactual changes in intracellular chloride concentration. J Neurosci Meth. 1995;57:27–35. doi: 10.1016/0165-0270(94)00116-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamsa K, Palva JM, Ruusuvuori E, Kaila K, Taira T. Synaptic GABAA activation inhibits AMPA-kainate receptor-mediated bursting in the newborn (P0-P2) rat hippocampus. J Neurophysiol. 2000;83:359–366. doi: 10.1152/jn.2000.83.1.359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leinekugel X, Tseeb V, Ben-Ari Y, Bregestovski P. Synaptic GABAA activation induces Ca2+ rise in pyramidal cells and interneurons from rat neonatal hippocampal slices. J Physiol. 1995;487:319–329. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1995.sp020882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lerma J, Herranz AS, Herreras O, Abraira V, Martín Del Río R. In vivo determination of extracellular concentration of amino acids in the rat hippocampus. A method based on brain dialysis and computerized analysis. Brain Res. 1986;384:145–155. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(86)91230-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y-X, Schaffner AE, Walton MK, Barker JL. Astrocytes regulate developmental changes in the chloride ion gradient of embryonic rat ventral spinal cord neurons in culture. J Physiol. 1998;509:847–858. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1998.847bm.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lipton SA, Kater SB. Neurotransmitter regulation of neuronal outgrowth, plasticity and survival. Trends Neurosci. 1989;12:265–270. doi: 10.1016/0166-2236(89)90026-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LoTurco JJ, Owens DF, Heath MjS, Davies MBE, Kriegstein AR. GABA and glutamate depolarize cortical progenitor cells and inhibit DNA synthesis. Neuron. 1995;15:1287–1298. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(95)90008-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maric D, Liu Q-Y, Maric I, Chaudry S, Chang Y-H, Smith SV, Sieghart W, Fritschy J-M, Barker JL. GABA expression dominates neuronal lineage progression in the embryonic rat neocortex and facilitates neurite outgrowth via GABAA autoreceptor/Cl− channels. J Neurosci. 2001;21:2343–2360. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-07-02343.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marty S, Berninger B, Carroll P, Thoenen H. GABAergic stimulation regulates the phenotype of hippocampal interneurons through the regulation of brain-derived neurotrophic factor. Neuron. 1996;16:565–570. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80075-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marty S, Wehrlé R, Alvarez-Leefmans FJ, Gasnier B, Sotelo C. Postnatal maturation of Na+,K+,2Cl− cotransporter expression and inhibitory synaptogenesis in the rat hippocampus: an immunocytochemical analysis. Eur J Neurosci. 2002;15:233–245. doi: 10.1046/j.0953-816x.2001.01854.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Misgeld U, Deisz RA, Dodt HU, Lux HD. The role of chloride transport in postsynaptic inhibition of hippocampal neurons. Science. 1986;232:1413–1415. doi: 10.1126/science.2424084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Obrietan K, van den Pol AN. GABA neurotransmission in the hypothalamus: developmental reversal from Ca2+ elevating to depressing. J Neurosci. 1995;15:5065–5077. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.15-07-05065.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Obrietan K, van den Pol AN. Growth cone calcium elevation by GABA. J Comp Neurol. 1996;372:167–175. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9861(19960819)372:2<167::AID-CNE1>3.0.CO;2-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Owens DF, Boyce LH, Davis MBE, Kriegstein AR. Excitatory GABA responses in embryonic and neonatal cortical slices demonstrated by gramicidin perforated-patch recordings and calcium imaging. J Neurosci. 1996;16:6414–6423. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-20-06414.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Payne JA, Stevenson TJ, Donaldson LF. Molecular characterization of a putative K–Cl cotransporter in rat brain. A neuronal-specific isoform. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:16245–16252. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.27.16245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plotkin MD, Snyder EY, Hebert SC, Delpire E. Expression of the Na–K–2Cl cotransporter is developmentally regulated in postnatal rat brains: a possible mechanism underlying GABA's excitatory role in immature brain. J Neurobiol. 1997;33:781–795. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-4695(19971120)33:6<781::aid-neu6>3.0.co;2-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reichling DB, Kyrozis A, Wang J, MacDermott AB. Mechanisms of GABA and glycine depolarization-induced calcium transients in rat dorsal horn neurons. J Physiol. 1994;476:411–421. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1994.sp020142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rivera C, Voipio J, Payne JA, Ruusuvuori E, Lahtinen H, Lamsa K, Pirvola U, Saarma M, Kaila K. The K+/Cl− co-transporter KCC2 renders GABA hyperpolarizing during neuronal maturation. Nature. 1999;397:251–255. doi: 10.1038/16697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rohrbacher J, Sauer K, Lewen A, Misgeld U. Enhancement of synaptic excitation by GABAA receptor antagonists in rat embryonic midbrain culture. J Neurophysiol. 1998;79:1113–1116. doi: 10.1152/jn.1998.79.2.1113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rohrbough J, Spitzer NC. Regulation of intracellular Cl− levels by Na+–dependent Cl− cotransport distinguishes depolarizing from hyperpolarizing GABAA receptor-mediated responses in spinal neurons. J Neurosci. 1996;16:82–91. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-01-00082.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith RL, Clayton GH, Wilcox CL, Escudero KW, Staley KJ. Differential expression of an inwardly rectifying chloride conductance in rat brain neurons: a potential mechanism for cell-specific modulation of postsynaptic inhibition. J Neurosci. 1995;15:4057–4067. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.15-05-04057.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun D, Murali SG. Na+–K+–2Cl− cotransporter in immature cortical neurons: a role in intracellular Cl− regulation. J Neurophysiol. 1999;81:1939–1948. doi: 10.1152/jn.1999.81.4.1939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sung K-W, Kirby M, McDonald MP, Lovinger DM, Delpire E. Abnormal GABAA receptor-mediated currents in dorsal root ganglion neurons isolated from Na–K–2Cl cotransporter null mice. J Neurosci. 2000;20:7531–7538. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-20-07531.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tossman U, Jonsson G, Ungerstedt U. Regional distribution and extracellular levels of amino acids in rat central nervous system. Acta Physiol Scand. 1986;127:533–545. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-1716.1986.tb07938.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van den Pol AN, Obrietan K, Chen G. Excitatory actions of GABA after neuronal trauma. J Neurosci. 1996;16:4283–4292. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-13-04283.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vardi N, Zhang L-L, Payne JA, Sterling P. Evidence that different cation chloride cotransporters in retinal neurons allow opposite responses to GABA. J Neurosci. 2000;20:7657–7663. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-20-07657.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan Y, Dempsey RJ, Sun D. Expression of Na+–K+–Cl− cotransporter in rat brain during development and its localization in mature astrocytes. Brain Res. 2001;911:43–55. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(01)02649-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuste R, Katz LC. Control of postsynaptic Ca2+ influx in developing neocortex by excitatory and inhibitory neurotransmitters. Neuron. 1991;6:333–344. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(91)90243-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]